This cohort study analyzes 4 years of longitudinal data to assess worsening in Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Score in association with changes in retinal nonperfusion from baseline as captured by ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography.

Key Points

Question

Given that ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography (UWF-FA) allows the ability to capture posterior and peripheral retinal nonperfusion, how do peripheral UWF-FA abnormalities in nonperfusion relate to future Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS) worsening and DR treatment initiation?

Findings

In this cohort study, greater baseline retinal nonperfusion was associated with higher risk of DRSS worsening or receipt of DR treatment, even after adjusting for baseline DRSS score and known systemic risk factors.

Meaning

The results suggest that retinal nonperfusion and predominantly peripheral lesions on UWF-FA should be included in staging systems to better predict risk of DRSS worsening over time.

Abstract

Importance

Presence of predominantly peripheral diabetic retinopathy (DR) lesions on ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography (UWF-FA) was associated with greater risk of DR worsening or treatment over 4 years. Whether baseline retinal nonperfusion assessment is additionally predictive of DR disease worsening is unclear.

Objective

To assess whether the extent and location of retinal nonperfusion identified on UWF-FA are associated with worsening in Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS) score or DR treatment over time.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study was a prospective, multicenter, longitudinal observational study with data for 508 eyes with nonproliferative DR and gradable nonperfusion on UWF-FA at baseline. All images were graded at a centralized reading center; 200° ultra-widefield (UWF) color images were graded for DR at baseline and annually for 4 years. Baseline 200° UWF-FA images were graded for nonperfused area, nonperfusion index (NPI), and presence of predominantly peripheral lesions on UWF-FA (FA PPL).

Interventions

Treatment of DR or diabetic macular edema was at investigator discretion.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Association of baseline UWF-FA nonperfusion extent with disease worsening, defined as either 2 or more steps of DRSS worsening within Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study fields on UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment.

Results

After adjusting for baseline DRSS, the risk of disease worsening over 4 years was higher in eyes with greater overall NPI (hazard ratio [HR] for 0.1-unit increase, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.02-1.21; P = .02) and NPI within the posterior pole (HR for 0.1-unit increase, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.17-1.56; P < .001) and midperiphery (HR for 0.1-unit increase, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.00-1.16; P = .04). In a multivariable analysis adjusting for baseline DRSS score and baseline systemic risk factors, greater NPI (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.02-1.22; P = .02) and presence of FA PPL (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.35-2.65; P < .001) remained associated with disease worsening.

Conclusions and Relevance

This 4-year longitudinal study has demonstrated that both greater baseline retinal nonperfusion and FA PPL on UWF-FA are associated with higher risk of disease worsening, even after adjusting for baseline DRSS score and known systemic risk. These associations between disease worsening and retinal nonperfusion and FA PPL support the increased use of UWF-FA to complement color fundus photography in future efforts for DR prognosis, clinical care, and research.

Introduction

Fundus photographic evaluation of the 7 standard retinal fields established by the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) can classify Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS) score and predict risk for DRSS worsening.1,2 However, imaging advances in ultra-widefield (UWF) technology allow broader views of the retinal periphery on UWF-color images as well as the ability to capture posterior and peripheral retinal nonperfusion on UWF fluorescein angiography (FA). Applications of UWF-FA for evaluation and management of diabetic retinopathy (DR) beyond what can be achieved with color fundus photographs include identification and quantification of leakage from microaneurysms and retinal neovascularization,3 panretinal retinal vascular leakage, and measurement of extent of retinal nonperfusion.4,5,6,7,8,9,10

The DRCR Retina Network Protocol AA was designed to assess how peripheral UWF-FA abnormalities relate to posterior pole pathology and vision loss as well as worsening of DR. Previous studies exploring the use of UWF-FA in evaluation and management of DR have addressed topics such as UWF-FA guidance of panretinal (scatter) photocoagulation to target areas of retinal nonperfusion,3 correlations between peripheral retinal nonperfusion on UWF-FA and diabetic macular edema,11,12,13 and the general lack of substantial improvement in retinal perfusion after treatment with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents or steroids.14,15,16,17 Cross-sectional data from the CLARITY study have shown a strong association of retinal nonperfusion and the presence of proliferative DR (PDR), suggesting that UWF-FA may potentially improve the ability to identify eyes at high risk for worsening DR.18

Despite the mounting evidence in the literature regarding the utility of UWF-FA and increasing use of UWF-FA in clinical retinal practices, many questions remain as to how to standardize acquisition and analysis of UWF-FAs as well as how and whether to use findings from UWF-FA to guide the evaluation and management of patients with DR. The DRCR Retina Network Protocol AA (hereafter Protocol AA) evaluated whether UWF fundus photographic and FA imaging can improve the ability to predict rates of DR progression beyond what is provided by the current standard ETDRS DRSS. The primary results from this study, evaluating the association of predominantly peripheral lesions (PPLs) on UWF-color and UWF-FA (color PPL and FA PPL, respectively) with DRSS worsening or treatment for DR are reported in a companion article.19 Herein, we report the 4-year longitudinal Protocol AA UWF-FA findings in greater detail to determine whether the extent of UWF-FA retinal nonperfusion is associated with increased rates of disease worsening over time and, if so, whether this association is independent of known risk factors for DRSS worsening, as well as presence of FA PPL as reported in the companion article.19

Methods

This was a prespecified secondary analysis of a prospective observational longitudinal study (Protocol AA) conducted by the DRCR Retina Network at 37 clinical sites in the United States and Canada from February 2015 to March 2020. The protocol is available on the study website.20 The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by multiple ethics boards. Study participants provided written informed consent. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines. Study participants received a $25 or $50 gift or money card for each completed study visit. Maximum compensation for each participant was $250 over 4 years.

Study Overview

In brief, adult participants with type 1 or 2 diabetes and at least 1 eye with nonproliferative DR (NPDR) on modified 7-field standard ETDRS color photographic grading (ETDRS levels 35-53), were enrolled in the study. Eyes with center-involved diabetic macular edema or a history of intravitreal treatment in the previous 12 months and those anticipating panretinal photocoagulation or intravitreal treatment within 6 months were excluded. The protocol required annual visits through 4 years.

Evaluation of UWF-FA Predominantly Peripheral Lesions and Retinal Nonperfusion

Detailed grading procedures for UWF-FA images for presence of PPL have been previously reported.19,21 The definition of retinal nonperfusion was based on the ETDRS FA grading protocol and Standard Care vs Corticosteroid for Retinal Vein Occlusion (SCORE) study.22,23 The study methodology for measurement of retinal nonperfusion has been described previously.4,24 In brief, all UWF images were stereographically projected. A template of the combined ETDRS 7 fields (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1) and the retinal zones (posterior pole, midperiphery, and far periphery) was digitally overlaid based on foveal and optic nerve head locations to measure the extent and distribution of retinal nonperfusion in the modified extended fields of UWF retinal images. Using ImageJ (version 1.48), the extent of retinal nonperfusion and total gradable area were determined manually by graders masked to retinopathy severity and PPL. For each eye, the total nonperfused area (NPA) and total gradable area, overall and for each individual extended field, were calculated in millimeters squared, and the nonperfusion index (NPI) was calculated by dividing NPA by gradable area. In addition, NPA and NPI were determined within concentric zones corresponding to the posterior pole (<10 mm from the foveal center), anatomic midperiphery (10-15 mm), and far periphery (>15 mm) and within each extended peripheral field.13

Outcomes

The primary outcome of disease worsening was a time-to-event outcome, defined as worsening by 2 or more steps on the DRSS or receiving treatment for DR during the 4 years of follow-up. Score on the DRSS at baseline and follow-up visits was assessed within the ETDRS fields from the UWF-color (masked) images.19 Secondary outcomes assessed within the ETDRS fields from UWF-color images included development of PDR or receipt of DR treatment, development of vitreous hemorrhage (including at clinical examinations) or receipt of DR treatment, and improvement by 2 or more steps on the DRSS over 4 years. Eyes that received vitrectomy, anti-VEGF, or steroid treatment for conditions other than DR without meeting the primary outcome were censored after treatment was initiated. Data from participants who neither met the outcome nor initiated treatment were censored at the last completed visit.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses included observed data from all study eyes with NPDR on baseline UWF-color images and gradable for nonperfusion on baseline UWF-FA, without imputation of missing data. The primary baseline risk factor of interest was the overall NPI. Eyes with measured nonperfusion were divided into 3 equally sized subgroups based on tertiles of NPI (low nonperfusion, NPI ≤0.028; medium nonperfusion, NPI >0.028 to 0.182; or high nonperfusion, NPI >0.182 to 0.861) (Figure 1). Kaplan-Meier estimates for the 4-year cumulative proportions of the primary outcome were reported. The Cox proportional hazards model for the primary outcome was constructed similarly to the primary outcome analysis reported elsewhere,19 with overall NPI included as a continuous factor and the percentage of gradable area over the theoretical maximum on UWF-FA as an additional covariate. Adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for 0.1-unit increase in NPI was reported with 95% CI. Sensitivity analyses evaluated the effect of potential informative censoring.25,26

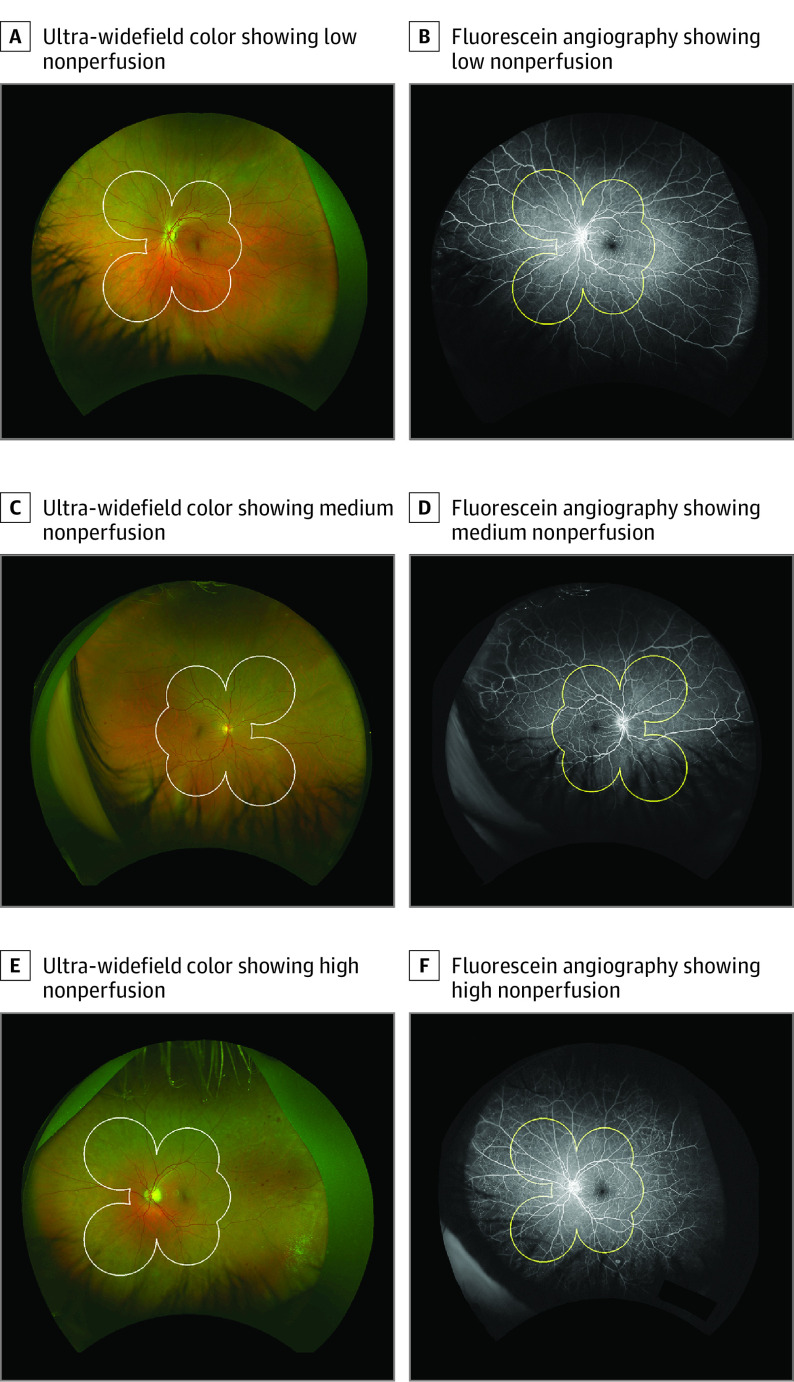

Figure 1. Examples of Eyes in the Low-, Medium-, and High-Nonperfusion Subgroups.

Representative paired ultra-widefield color and fluorescein angiography (FA) images of eyes in the low, medium, and high tertile groups of retinal nonperfusion. White border on the color and yellow border on the FA represent the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) areas border. A and B, Eye with low nonperfusion. The baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS) level within the ETDRS area was moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), and there was no progression at 4 years. Predominantly peripheral lesions on FA (FA PPL) were absent. C and D, Eye with medium nonperfusion. The baseline DRSS score was moderate NPDR with progression to very severe NPDR at year 2. Color PPL and FA PPL were present. E and F, Eye with high nonperfusion. The baseline DRSS score was moderate NPDR with progression to very severe NPDR at year 1. Color and FA PPL were present.

Additional nonperfusion factors and participant characteristics were each evaluated similarly to NPI. Multivariable models were fit with the primary risk factor, adjusting for potential risk factors that either were significant in the univariable analysis (P < .05) or had 10% or greater difference in the 4-year Kaplan-Meier estimators of the primary outcome. Analyses for secondary outcomes and secondary risk factors mimicked the primary analysis. Secondary NPI risk factors (by location) were only tested when the analysis with the overall NPI demonstrated a significant association. In all analyses, P < .05 was considered statistically significant, recognizing the type I error rate was not fully controlled at 5% and that some significant findings may occur by chance. All P values are 2-sided. Analyses were performed with SAS/STAT version 15.1 (SAS Institute).

Results

Study Participants

The analysis included 508 eyes graded as having NPDR and gradable UWF-FA nonperfusion at baseline, among which 47 eyes (9%) did not have any nonperfusion identified. The 4-year visit completion rate excluding deaths was 79%, 71%, 76%, and 82% in the no-, low-, medium-, and high-nonperfusion subgroups, respectively (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Most baseline characteristics appeared similar among the 4 subgroups, except eyes with greater nonperfusion had a larger proportion of participants with type 1 diabetes, longer duration of diabetes, more severe baseline DRSS score, and higher prevalence of FA PPL (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics by Baseline Nonperfusion on UWF-FA.

| Characteristic | Nonperfusion, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Low | Medium | High | |

| No. of eyes | 47 | 153 | 154 | 154 |

| Participant characteristics | ||||

| Female | 23 (49) | 62 (41) | 85 (55) | 82 (53) |

| Male | 24 (51) | 91 (59) | 69 (45) | 72 (47) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 63 (46-68) | 60 (51-67) | 60 (50-68) | 63 (53-69) |

| Race and ethnicitya | ||||

| White | 34 (72) | 91 (59) | 111 (72) | 111 (72) |

| Black or African American | 7 (15) | 32 (21) | 25 (16) | 24 (16) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (4) | 20 (13) | 13 (8) | 12 (8) |

| Asian | 3 (6) | 3 (2) | 1 (<1) | 6 (4) |

| More than 1 race | 0 | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) |

| Native Hawaiian, Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown or not reported | 1 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Diabetes type | ||||

| Type 1 | 8 (17) | 13 (8) | 30 (19) | 27 (18) |

| Type 2 | 39 (83) | 136 (89) | 124 (81) | 125 (81) |

| Uncertain | 0 | 4 (3) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Duration of diabetes, median (IQR) | 21 (14-28) | 17 (13-25) | 19 (12-28) | 23 (16-29) |

| Hemoglobin A1c, median (IQR), %b | 7.8 (6.8-8.7) | 8.4 (7.3-9.7) | 8.1 (7.0-9.5) | 7.6 (7.0-8.8) |

| Insulin use | 34 (72) | 110 (72) | 114 (74) | 119 (77) |

| Mean arterial pressure, median (IQR), mm Hg | 98 (93-108) | 99 (93-110) | 96 (90-105) | 96 (88-104) |

| History of hypertension | 38 (81) | 118 (77) | 118 (77) | 120 (78) |

| History of high cholesterol/dyslipidemia | 39 (83) | 104 (68) | 102 (66) | 99 (64) |

| Taking fenofibrate at baseline | 1 (2) | 4 (3) | 10 (6) | 4 (3) |

| Taking metformin at baselinec | 27 (60) | 70 (47) | 73 (50) | 61 (41) |

| eGFR, median (IQR), mL/min/1.73 m2d | 90 (67-90) | 87 (61-90) | 90 (67-90) | 84 (63-90) |

| Participants with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 6 (13) | 19 (12) | 14 (9) | 20 (13) |

| Participants with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 26 (55) | 70 (46) | 65 (42) | 69 (45) |

| Unknown eGFR | 15 (32) | 64 (42) | 75 (49) | 65 (42) |

| Albumin to creatinine ratiod | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 8 (4-94) | 53 (12-173) | 17 (5-63) | 20 (8-63) |

| No albuminuria (<30) | 20 (43) | 40 (26) | 50 (32) | 54 (35) |

| Microalbuminuria (30-300) | 8 (17) | 32 (21) | 21 (14) | 21 (14) |

| Macroalbuminuria (>300) | 4 (9) | 17 (11) | 7 (5) | 11 (7) |

| Unknown | 15 (32) | 64 (42) | 76 (49) | 68 (44) |

| Participants with 2 study eyes | 32 (68) | 111 (73) | 109 (71) | 86 (56) |

| Study eye ocular characteristics | ||||

| Visual acuity letter score, median (IQR) | 85 (90-80) | 86 (90-82) | 86 (90-82) | 85 (89-80) |

| Snellen equivalent, median (IQR) | 20/20 (20/16-20/25) | 20/20 (20/16-20/25) | 20/20 (20/16-20/25) | 20/20 (20/16-20/25) |

| DRSS score by reading center assessment (UWF masked color image) | ||||

| Mild NPDR (35) | 30 (64) | 51 (33) | 41 (27) | 34 (22) |

| Moderate NPDR (43) | 11 (23) | 40 (26) | 42 (27) | 47 (31) |

| Moderately severe NPDR (47) | 3 (6) | 30 (20) | 24 (16) | 19 (12) |

| Severe and very severe NPDR (53) | 3 (6) | 32 (21) | 47 (31) | 54 (35) |

| DRSS score by reading center assessment (UWF unmasked color image) | ||||

| Mild NPDR (35) | 26 (55) | 40 (26) | 33 (21) | 26 (17) |

| Moderate NPDR (43) | 14 (30) | 42 (27) | 36 (23) | 33 (21) |

| Moderately severe NPDR (47) | 3 (6) | 36 (24) | 29 (19) | 30 (19) |

| Severe and very severe NPDR (53) | 4 (9) | 33 (22) | 54 (35) | 57 (37) |

| Inactive PDR (60) or mild PDR (61) | 0 | 1 (<1) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Moderate PDR (65) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (3) |

| Ungradable | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 |

| Difference in DRSS score by reading center assessment (UWF unmasked vs masked color image)e | ||||

| UWF unmasked worse | 5 (11) | 16 (11) | 24 (16) | 36 (23) |

| Same grading | 42 (89) | 133 (88) | 128 (83) | 116 (75) |

| UWF masked worse | 0 | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Lens status | ||||

| Aphakic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| PC IOL | 4 (9) | 22 (14) | 41 (27) | 55 (36) |

| Phakic | 43 (91) | 131 (86) | 113 (73) | 98 (64) |

| OCT CST Spectralis equivalent, median (IQR), μmf | 282 (258-294) | 274 (260-290) | 278 (258-294) | 281 (263-298) |

| OCT volume, median (IQR), mm2g | 6.9 (6.6-7.2) | 7.0 (6.6-7.3) | 7.0 (6.7-7.3) | 6.9 (6.6-7.4) |

| History of DME treatment | 3 (6) | 28 (18) | 46 (30) | 32 (21) |

| Focal laser for DME | 3 (6) | 27 (18) | 44 (29) | 31 (20) |

| Anti-VEGF for DME | 1 (2) | 10 (7) | 10 (6) | 6 (4) |

| Corticosteroids (including implants) for DME | 0 | 1 (<1) | 3 (2) | 1 (<1) |

| Presence of predominantly peripheral lesions on UWF-FA | 17 (36) | 42 (27) | 85 (55) | 84 (55) |

Abbreviations: CST, central subfield thickness; DME, diabetic macular edema; DR, diabetic retinopathy; DRSS, Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FA, fluorescein angiography; NPDR, nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PC IOL, posterior chamber intraocular lens; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; UWF, ultra-widefield; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Participant-reported race and ethnicity were collected based on fixed categories.

Unavailable for 1 eye in the no-nonperfusion, 3 in low-nonperfusion, 2 in medium-nonperfusion, and 1 in high-nonperfusion subgroups.

Unavailable for 2 eyes in the no-nonperfusion, 4 in low-nonperfusion, 8 in medium-nonperfusion, and 4 in high-nonperfusion subgroups. Percentage is based on eyes with available information.

Blood and urine samples were implemented about 5 months after study recruitment began.

Excludes 1 eye with ungradable unmasked DR grades. Percentage is based on eye with gradable DR severity on both images.

Cirrus measurements were converted to Spectralis equivalents using the following formula: Spectralis = 40.78 + 0.95 × Cirrus.

Retinal volume measurements were converted to Stratus equivalents using the following formulae: Stratus = −1.21 + 1.02 × Cirrus; Stratus = −2.05 + 1.06 × Spectralis.

Treatment Initiation

Treatments initiated during follow-up by overall NPI are reported in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. A higher percentage of eyes (19%) in the high nonperfusion quartile received DR treatment compared with no- (2%), low- (6%), and medium-nonperfusion (10%) eyes. Within each NPI subgroup, 3% or fewer eyes were treated with anti-VEGF, steroid, or vitrectomy during follow-up for conditions other than DR or diabetic macular edema.

Primary Outcome: DRSS Worsening or Receipt of DR Treatment

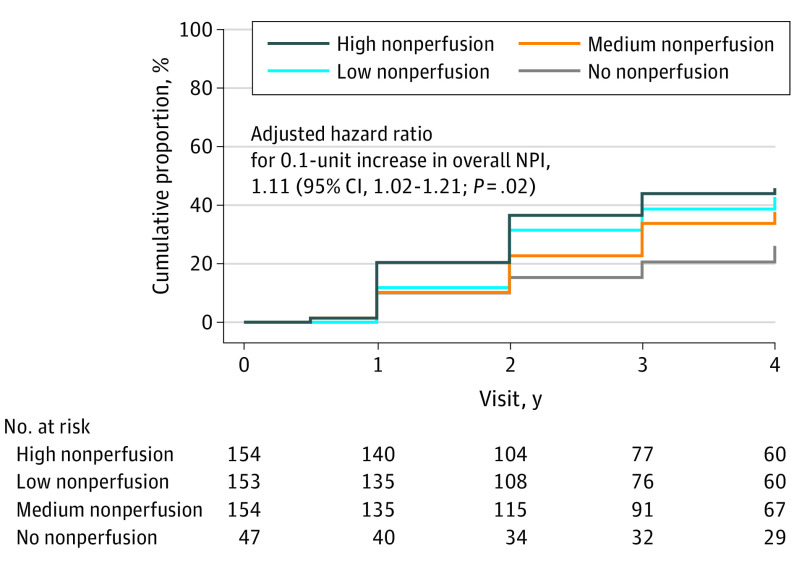

The 4-year cumulative proportion of eyes meeting the primary disease-worsening outcome, consisting of either worsening by 2 or more steps on the DRSS on masked UWF-color images or receiving treatment for DR, was 26% (95% CI, 15%-43%) in the no-nonperfusion group, and 43% (95% CI, 34%-52%), 38% (95% CI, 30%-47%), and 46% (95% CI, 38%-55%) in the low-, medium-, and high-nonperfusion subgroups, respectively (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.02-1.21; P = .02) (Figure 2). The primary reason for meeting the primary outcome in each subgroup was worsening by 2 or more steps on the DRSS (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Consistent results were seen in the sensitivity analyses accounting for potential informative censoring due to receipt of non-DR treatment (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). No interaction was observed between baseline DRSS score and overall NPI (P = .22). Greater NPI in the posterior pole and midperiphery; ETDRS fields 6-7; and the extended peripheral superior, inferior, and nasal regions was significantly associated with a higher risk of disease worsening over 4 years (eTable 5 in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Cumulative Proportion of Disease Worsening Through 4 Years by Baseline Overall Nonperfusion Index (NPI) on Ultra-Widefield Fluorescein Angiography (UWF-FA).

Worsening was defined by either a worsening of 2 or more steps on the Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS) within Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) fields on masked ultra-widefield (UWF) color images or receipt of diabetic retinopathy (DR) treatment. Eyes receiving treatment with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor, steroid, or vitrectomy for conditions other than DR were censored after treatment initiation. The cumulative proportion for primary outcome of disease worsening was 26% (95% CI, 15%-43%) in the no-nonperfusion group, and 43% (95% CI, 34%-52%), 38% (95% CI, 30%-47%), and 46% (95% CI, 38%-55%) in eyes with low nonperfusion, medium nonperfusion, and high nonperfusion, respectively. Eyes that did not meet the primary outcome or that received non-DR treatment were censored at the last visit. The Cox proportional hazards model was adjusted for baseline DRSS score within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images, percentage of total imaged area on UWF-FA, and the correlation between the 2 study eyes from the same participant.

Rates of the primary outcome of disease worsening by baseline participant-level risk factors are reported in eTable 6 in Supplement 1. In the univariable analysis, after adjustment for baseline DRSS score, significantly higher rates of disease worsening were seen among participants with shorter duration of diabetes (HR for a 10-year increase, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74-0.96; P = .008), higher hemoglobin (Hb) A1c value (HR for 1% increase, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.07-1.26; P < .001), and albuminuria (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.20-2.77; P = .005).

When accounting for baseline DRSS score and participant-level risk factors, including age, diabetes type, duration of diabetes, HbA1c value, and albuminuria, greater overall NPI was still associated with an increased risk for disease worsening in the multivariable model (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.04-1.24; P = .003) (Table 2). Nonperfusion index and FA PPL, the latter of which was also associated with an increased risk of disease worsening over time in a previous report,19 both remained statistically significant when FA PPL was added to the multivariable model (HR for NPI: 1.11; 95% CI, 1.02-1.22; P = .02; for FA PPL: 1.89; 95% CI, 1.35-2.63; P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariable Analysis of Primary Outcome: DR Worsening by 2 or More Steps Within the ETDRS Fields on UWF-Color Images or Receipt of DR Treatment Through 4 Years by Baseline NPI, FA PPL, and Participant Factors.

| Factor | Multivariable analysisa | |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| NPI with adjustment for participant risk factors | ||

| Overall NPI: per 0.1-unit increase | 1.14 (1.04-1.24) | .003 |

| DRSS level within ETDRS fields | NA | .15 |

| Age: per 10-y increase | 0.87 (0.73-1.04) | .13 |

| Diabetes type: type 2 vs type 1 | 1.36 (0.67-2.74) | .39 |

| Duration of diabetes: per 10-y increase | 0.90 (0.76-1.07) | .22 |

| Hemoglobin A1c: per 1% increase | 1.12 (1.02-1.23) | .01 |

| Albumin to creatinine ratio: albuminuria vs no albuminuriab | 1.88 (1.16-3.04) | .01 |

| NPI and FA PPL with adjustment for participant risk factors | ||

| Overall NPI: per 0.1-unit increase | 1.11 (1.02-1.22) | .02 |

| FA PPL present vs FA PPL absent | 1.89 (1.35-2.63) | <.001 |

| DRSS score within ETDRS fields | NA | .43 |

| Age: per 10-y increase | 0.86 (0.72-1.02) | .09 |

| Diabetes type: type 2 vs type 1 | 1.54 (0.75-3.15) | .24 |

| Duration of diabetes: per 10-y increase | 0.86 (0.72-1.03) | .09 |

| Hemoglobin A1c: per 1% increase | 1.13 (1.03-1.24) | .008 |

| Albumin to creatinine ratio: albuminuria vs no albuminuriab | 1.80 (1.11-2.92) | .02 |

Abbreviations: DR, diabetic retinopathy; DRSS, Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; FA, fluorescein angiography; NA, not applicable; NPI, nonperfusion index; PPL, predominantly peripheral lesion; UWF, ultra-widefield.

Eyes receiving treatment with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor, steroid, or vitrectomy for conditions other than DR were censored after treatment initiation. Participant-level risk factors that either were significant in the univariable analysis (in eTable 6 in Supplement 1) or had ≥10% difference in the Kaplan-Meier estimates of the outcome were included as additional risk factors in the multivariable analysis to account for potential confounding. Hazard ratios and P values were obtained from a Cox proportional hazards model with additional adjustment for percentage of total imaged area on UWF-FA and the correlation between the 2 study eyes from the same participant.

The unknown group was included in the analysis, but no comparison was performed of this subgroup to the subgroups with known values. Hazard ratio and P value were provided only for comparing the 2 groups with known values (ie, albuminuria vs no albuminuria).

Secondary DR Outcomes

Greater NPI was associated with an increased risk for development of PDR or receipt of DR treatment (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.04-1.29; P = .008), as well as for development of vitreous hemorrhage or receipt of DR treatment (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.14-1.48; P < .001) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1 and Table 3). No association was identified between NPI and improvement of 2 or more steps on the DRSS over time. Exploratory outcomes by overall NPI are reported in eTable 7 in Supplement 1. Rates of development of PDR or DR treatment, vitreous hemorrhage or DR treatment, and improvement of 2 or more steps on the DRSS by secondary nonperfusion and participant-level risk factors are provided in eTables 8-10 in Supplement 1. An increased risk of developing PDR or receiving DR treatment or developing vitreous hemorrhage or receiving DR treatment was found in eyes with greater NPI in most retinal zones, ETDRS fields, and retinal regions. No association was detected between DRSS improvement with nonperfusion or participant-level risk factors, except for longer duration of diabetes, lower HbA1c value, and lower eGFR. Nonperfusion index and FA PPL remained significantly associated with onset of PDR or DR treatment in a multivariable model, including participant-level risk factors of age, duration of diabetes, HbA1c value, and albuminuria (eTable 11 in Supplement 1). NPI also remained significantly associated with onset of vitreous hemorrhage or DR treatment in a multivariable model with age and HbA1c value (eTable 12 in Supplement 1).

Table 3. Secondary Outcomes on Masked UWF-Color Images by Baseline Overall NPI.

| Outcome | No. of eyes | Kaplan-Meier estimate (95% CI) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of PDR within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatmenta | ||||

| No nonperfusion | 47 | 7.8 (2.6-22) | 1.16 (1.04-1.29)b | .008 |

| Low nonperfusion | 153 | 22 (15-30) | ||

| Medium nonperfusion | 154 | 18 (12-26) | ||

| High nonperfusion | 154 | 32 (25-41) | ||

| Development of vitreous hemorrhage within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or at clinical examination or receipt of DR treatmenta | ||||

| No nonperfusion | 47 | 2.5 (0.4-16) | 1.30 (1.14-1.48)b | <.001 |

| Low nonperfusion | 153 | 7.2 (3.8-13) | ||

| Medium nonperfusion | 154 | 11 (6.2-18) | ||

| High nonperfusion | 154 | 21 (15-29) | ||

| DRSS improvement of ≥2 steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color imagesc | ||||

| No nonperfusion | 47 | 10 (4.0-25) | NA | NA |

| Low nonperfusion | 153 | 19 (13-28) | ||

| Medium nonperfusion | 154 | 18 (12-26) | ||

| High nonperfusion | 154 | 18 (12-26) |

Abbreviations: DME, diabetic macular edema; DR, diabetic retinopathy; DRSS, Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; FA, fluorescein angiography; NA, not applicable; NPI, nonperfusion index; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PPL, predominantly peripheral lesions; UWF, ultra-widefield; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Eyes receiving treatment with anti-VEGF, steroid, or vitrectomy for conditions other than DR were censored after treatment initiation. The Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for baseline DRSS score within the ETDRS fields on UWF-color images, percentage of total imaged area on FA, baseline overall NPI, and the correlation between the 2 study eyes from the same participant.

Per 0.1-unit increase.

Eyes receiving treatment with anti-VEGF, steroid, or vitrectomy for any conditions (ie, DR, DME, or others) were censored after treatment initiation. Because there was a significant interaction between DRSS score and NPI (P < .001), and the outcome rates in the mild and moderate NPDR subgroups were low, Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed including only the moderately severe, severe, and very severe subgroups (eTable 10 in Supplement 1). The Kaplan-Meier estimates for the cumulative proportion of DRSS improvement of ≥2 steps included eyes that improved at any time during the study (before initiating any treatment); therefore, some eyes may have subsequently worsened. At 4 years, only 8% of eyes (22/292) experienced ≥2-step DRSS improvement from baseline without initiating any treatment.

Discussion

In this multicenter, 4-year longitudinal study, increasing retinal NPI was associated with a significantly higher risk of DRSS worsening or treatment as well as secondary outcomes such as PDR development and vitreous hemorrhage over time. The associations with retinal nonperfusion are driven by nonperfusion located primarily in the posterior pole and midperiphery. Although greater extent and severity of retinal nonperfusion was associated with the presence of FA PPL, both nonperfusion and FA PPL are independently associated with DRSS worsening or treatment even after adjusting for baseline DRSS score, diabetes duration, and HbA1c value. These results suggest that retinal nonperfusion and FA PPL should be included in staging systems to predict risk of disease worsening over time.

Prior cross-sectional studies among eyes of patients with diabetes have shown that increasing DRSS score is associated with increasing retinal nonperfusion.4,21 In addition, the ETDRS found that capillary loss or retinal nonperfusion on FA was a risk factor for progression to PDR. Moreover, the predictive power of retinal nonperfusion was strengthened when excluding the area within 1500 μm of the center of the macula, suggesting that nonperfusion peripheral to the retinal center may play an important role in DR progression.27 In the past, using retinal imaging techniques focused on the posterior pole, these FA risk factors were not thought to provide additional significant clinical benefit compared with evaluating DR severity on color photography alone.27 This was because color photography provided a DR severity grading with substantial predictive power that was adequate to act as a reliable guideline for guiding patient management decisions with the treatment options available at the time. Thus, since the early 1990s, the staging of DR severity on color fundus photographs without reference to FA has remained the standard of clinical care of eyes with DR. However, substantial advances in eye and medical care have improved visual and anatomic outcomes for many patients with diabetes and shifted the focus from intervening only at advanced stages of disease to diagnosing and managing earlier stages of DR, emphasizing the need to more accurately assess underlying disease severity in order to predict future DR worsening.28,29

The Protocol AA results, which suggest that future use of FA PPL and nonperfusion on UWF may improve prediction of retinopathy outcomes beyond what can be predicted from standard color photographs, are consistent with the idea that FA PPL and nonperfusion may be retinal markers for more severe underlying retinal vascular disease than is evident on color photography or clinical examination alone. Prior work on eyes with NPDR has demonstrated that UWF-FA identifies substantially more retinal microaneurysms than color imaging alone.30 In this cohort, FA PPL are primarily composed of microaneurysms in more than 91% of eyes and, when present, increase the risk of progression by 72% overall.19 Previous observations by Kohner and Sleightholm31 and work from the Wisconsin Epidemiology Study of Diabetic Retinopathy32 have demonstrated the association of retinal microaneurysm counts with long-term progression of DR. Seminal histologic studies from Cogan and Kuwabara33 and other clinical research efforts further suggest that the presence of retinal nonperfusion likely underlies the development of microaneurysms and other diabetic retinal lesions. Thus, increases in nonperfusion may at least partially account for the association between FA PPL and increases in DRSS worsening or DR treatment.4,34,35 However, in this study, FA PPL and nonperfusion remained significantly associated with disease worsening when they were both included in multivariable models, suggesting that increasing nonperfusion may not be the sole factor underlying the association between FA PPL and the primary outcome.

It has long been hypothesized that hyperglycemia-induced retinal ischemia is the main initiating factor in the development and progression of DR.33 This 4-year, prospective, multicenter study provides UWF angiographic evidence to support this hypothesis.4,34,35 However, it should be noted that the measurement of retinal nonperfused area is only a surrogate marker for inadequate perfusion that results in retinal ischemia and tissue hypoxia. Studies that directly measure retinal ischemia and provide metabolic mapping of the retina might elucidate measures that are even more strongly associated with future DR outcomes.

Although the DRSS is the current gold standard for determining DR severity in clinical and research settings, the identification of reliably measured and accurate predictive markers for retinopathy progression and disease activity in earlier stages of DR are now more relevant compared with when the ETDRS scale was created, more than 30 years ago. Future clinical trials for novel and prophylactic DR therapies could benefit greatly from more accurate ways to assess risk of future DR disease worsening. The refinement of the DRSS to optimize its predictive potential in research and clinical use may involve aspects of neural retinal and molecular pathways and systemic disease that are not currently incorporated.36 The Protocol AA data set, containing longitudinal matched color and angiographic images, provides a rich opportunity to explore these kinds of novel risk factors for DR disease worsening that have not been previously addressed.

Strengths and Limitations

This study performed standardized and rigorous masked evaluation of UWF images and angiograms, used trained graders in a reading center environment optimized for evaluating UWF images, adhered to a standardized image-acquisition protocol, and employed clinical trial–certified retinal imagers. Nonetheless, as described in the accompanying article, limitations of this study can be found in aspects of participant retention (the 4-year completion rate was 77%), imaging (P200Tx instruments were used for 97.5% of image capture), and correlation to visual outcomes (the association of FA PPL and UWF-FA nonperfusion with vision outcomes has not been addressed).19 In addition, although optical coherence tomography angiography images were captured at a subset of Protocol AA clinical sites, results from these images have not been explored in the current analyses.

Conclusions

This 4-year longitudinal study has demonstrated that greater baseline retinal nonperfusion on UWF-FA, in addition to FA PPL, is associated with higher risk of DR worsening or treatment, even after adjusting for baseline DRSS score and participant-level risk factors, such as diabetes duration and glycemic control. These associations between disease worsening and retinal nonperfusion and FA PPL support the increased use of UWF-FA to complement color fundus photography in future efforts for DR prognosis, clinical care, and research.

eFigure 1. Ultrawide extended fields on fluorescein angiography

eFigure 2. Example of an eye in the high nonperfusion subgroup progressing from NPDR to PDR

eTable 1. Visit Completion Over 4 Years by Baseline Overall Nonperfusion Index

eTable 2. Treatment Initiation During Follow-up by Baseline Nonperfusion and DR severity

eTable 3. Initial event for eyes meeting the primary outcome

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analyses of Primary Outcome: DR worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by overall NPI on UWF-FA

eTable 5. Univariable Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by study eye nonperfusion characteristics on UWF-FA

eTable 6. Univariable Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline participant factors

eTable 7. Exploratory outcomes on UWF-color images by baseline overall NPI

eTable 8. Univariable Analyses of Secondary Outcome: Development of PDR within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by study eye nonperfusion and participant characteristics on UWF-FA

eTable 9. Univariable Analyses of Secondary Outcome: Development of vitreous hemorrhage within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or at clinical exam or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by study eye nonperfusion and participant characteristics on UWF-FA

eTable 10. Univariable Analyses of Secondary Outcome: Improvement of 2 or more steps in DRSS within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images by study eye nonperfusion and participant characteristics on UWF-FA

eTable 11. Multivariable Analysis of Secondary Outcome: Development of PDR within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline NPI, FA-PPL and participant factors

eTable 12. Multivariable Analysis of Secondary Outcome: Development of vitreous hemorrhage within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or at clinical exam or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline NPI, FA-PPL and participant factors

Nonauthor collaborators

References

- 1.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group . Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs—an extension of the modified Airlie House classification: ETDRS report number 10. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(5)(suppl):786-806. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(13)38012-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL III, Klein RE, et al. ; Global Diabetic Retinopathy Project Group . Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(9):1677-1682. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00475-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy S, Hu A, Schwartz SD. Ultra wide field fluorescein angiography guided targeted retinal photocoagulation (TRP). Semin Ophthalmol. 2009;24(1):9-14. doi: 10.1080/08820530802519899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva PS, Dela Cruz AJ, Ledesma MG, et al. Diabetic retinopathy severity and peripheral lesions are associated with nonperfusion on ultrawide field angiography. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(12):2465-2472. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sim DA, Keane PA, Rajendram R, et al. Patterns of peripheral retinal and central macula ischemia in diabetic retinopathy as evaluated by ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(1):144-153.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver SC, Schwartz SD. Peripheral vessel leakage (PVL): a new angiographic finding in diabetic retinopathy identified with ultra wide-field fluorescein angiography. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010;25(1-2):27-33. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2010.481239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wessel MM, Nair N, Aaker GD, Ehrlich JR, D’Amico DJ, Kiss S. Peripheral retinal ischaemia, as evaluated by ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography, is associated with diabetic macular oedema. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(5):694-698. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell JF, Al-Khersan H, Shi Y, et al. Retinal nonperfusion in proliferative diabetic retinopathy before and after panretinal photocoagulation assessed by widefield OCT angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;213:177-185. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couturier A, Rey PA, Erginay A, et al. Widefield OCT-angiography and fluorescein angiography assessments of nonperfusion in diabetic retinopathy and edema treated with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(12):1685-1694. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan W, Uji A, Nittala M, et al. Retinal vascular bed area on ultra-wide field fluorescein angiography indicates the severity of diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;bjophthalmol-2020-317488. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel RD, Messner LV, Teitelbaum B, Michel KA, Hariprasad SM. Characterization of ischemic index using ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography in patients with focal and diffuse recalcitrant diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155(6):1038-1044.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan W, Wang K, Ghasemi Falavarjani K, et al. Distribution of nonperfusion area on ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography in eyes with diabetic macular edema: DAVE Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;180:110-116. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva PS, Cavallerano JD, Sun JK, Soliman AZ, Aiello LM, Aiello LP. Peripheral lesions identified by mydriatic ultrawide field imaging: distribution and potential impact on diabetic retinopathy severity. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(12):2587-2595. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wykoff CC, Nittala MG, Zhou B, et al. ; Intravitreal Aflibercept for Retinal Nonperfusion in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy Study Group . Intravitreal aflibercept for retinal nonperfusion in proliferative diabetic retinopathy: outcomes from the randomized RECOVERY trial. Ophthalmol Retina. 2019;3(12):1076-1086. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2019.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Querques L, Parravano M, Sacconi R, Rabiolo A, Bandello F, Querques G. Ischemic index changes in diabetic retinopathy after intravitreal dexamethasone implant using ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography: a pilot study. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54(8):769-773. doi: 10.1007/s00592-017-1010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levin AM, Rusu I, Orlin A, et al. Retinal reperfusion in diabetic retinopathy following treatment with anti-VEGF intravitreal injections. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:193-200. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S118807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonnin S, Dupas B, Lavia C, et al. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy can improve diabetic retinopathy score without change in retinal perfusion. Retina. 2019;39(3):426-434. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholson L, Ramu J, Chan EW, et al. Retinal nonperfusion characteristics on ultra-widefield angiography in eyes with severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(6):626-631. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcus D, Silva PS, Liu D, et al. Association of predominantly peripheral lesions on ultra-widefield imaging and the risk of diabetic retinopathy worsening over time. JAMA Ophthalmol. Published online August 18, 2022. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.3131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaeb Center for Health Research . DRCR.net public website. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://www.drcr.net

- 21.Aiello LP, Odia I, Glassman AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Comparison of Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study standard 7-field imaging with ultrawide-field imaging for determining severity of diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(1):65-73. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.4982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group . Classification of diabetic retinopathy from fluorescein angiograms. ETDRS report number 11. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(5)(suppl):807-822. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(13)38013-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blodi BA, Domalpally A, Scott IU, et al. ; SCORE Study Research Group . Standard Care vs Corticosteroid for Retinal Vein Occlusion (SCORE) Study system for evaluation of stereoscopic color fundus photographs and fluorescein angiograms: SCORE Study Report 9. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(9):1140-1145. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva PS, Liu D, Glassman AR, et al. ; DRCR Retina Network . Assessment of fluorescein angiography nonperfusion in eyes with diabetic retinopathy using ultrawide field retinal imaging. Retina. 2022;42(7):1302-1310. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prentice RL, Kalbfleisch JD, Peterson AV Jr, Flournoy N, Farewell VT, Breslow NE. The analysis of failure times in the presence of competing risks. Biometrics. 1978;34(4):541-554. doi: 10.2307/2530374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group . Fluorescein angiographic risk factors for progression of diabetic retinopathy: ETDRS report number 13. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(5)(suppl):834-840. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(13)38015-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keech AC, Mitchell P, Summanen PA, et al. ; FIELD study investigators . Effect of fenofibrate on the need for laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy (FIELD study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9600):1687-1697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61607-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown DM, Wykoff CC, Boyer D, et al. Evaluation of intravitreal aflibercept for the treatment of severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy: results from the PANORAMA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(9):946-955. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.2809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashraf M, Sampani K, AbdelAl O, et al. Disparity of microaneurysm count between ultrawide field colour imaging and ultrawide field fluorescein angiography in eyes with diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(12):1762-1767. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-315807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohner EM, Sleightholm M. Does microaneurysm count reflect severity of early diabetic retinopathy? Ophthalmology. 1986;93(5):586-589. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(86)33692-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein R, Meuer SM, Moss SE, Klein BE. The relationship of retinal microaneurysm counts to the 4-year progression of diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(12):1780-1785. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020862028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cogan DG, Kuwabara T. Capillary shunts in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 1963;12:293-300. doi: 10.2337/diab.12.4.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niki T, Muraoka K, Shimizu K. Distribution of capillary nonperfusion in early-stage diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1984;91(12):1431-1439. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(84)34126-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimizu K, Kobayashi Y, Muraoka K. Midperipheral fundus involvement in diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1981;88(7):601-612. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(81)34983-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun JK, Aiello LP, Abràmoff MD, et al. Updating the staging system for diabetic retinal disease. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(4):490-493. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Ultrawide extended fields on fluorescein angiography

eFigure 2. Example of an eye in the high nonperfusion subgroup progressing from NPDR to PDR

eTable 1. Visit Completion Over 4 Years by Baseline Overall Nonperfusion Index

eTable 2. Treatment Initiation During Follow-up by Baseline Nonperfusion and DR severity

eTable 3. Initial event for eyes meeting the primary outcome

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analyses of Primary Outcome: DR worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by overall NPI on UWF-FA

eTable 5. Univariable Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by study eye nonperfusion characteristics on UWF-FA

eTable 6. Univariable Analyses of Primary Outcome: DRSS worsening by 2 or more steps within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline participant factors

eTable 7. Exploratory outcomes on UWF-color images by baseline overall NPI

eTable 8. Univariable Analyses of Secondary Outcome: Development of PDR within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by study eye nonperfusion and participant characteristics on UWF-FA

eTable 9. Univariable Analyses of Secondary Outcome: Development of vitreous hemorrhage within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or at clinical exam or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by study eye nonperfusion and participant characteristics on UWF-FA

eTable 10. Univariable Analyses of Secondary Outcome: Improvement of 2 or more steps in DRSS within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images by study eye nonperfusion and participant characteristics on UWF-FA

eTable 11. Multivariable Analysis of Secondary Outcome: Development of PDR within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline NPI, FA-PPL and participant factors

eTable 12. Multivariable Analysis of Secondary Outcome: Development of vitreous hemorrhage within the ETDRS fields on masked UWF-color images or at clinical exam or receipt of DR treatment through 4 years by baseline NPI, FA-PPL and participant factors

Nonauthor collaborators