Abstract

The exposure of Candida albicans to fluconazole resulted in the nondisjunction of two specific chromosomes in 17 drug-resistant mutants, each obtained by an independent mutational event. The chromosomal changes occurred at high frequencies and were related to the duration of the drug exposure. The loss of one homologue of chromosome 4 occurred after incubation on a fluconazole medium for 7 days. A second change, the gain of one copy of chromosome 3, was observed after exposure for 35 or 40 days. We found that the mRNA levels of ERG11, CDR1, CDR2, and MDR1, the candidate fluconazole resistance genes, remained either the same or were diminished. The lack of overexpression of putative drug pumps or the drug target indicated that some other mechanism(s) may be operating. The fluconazole resistance phenotype, electrophoretic karyotypes, and transcript levels of mutants were stable after growth for 112 generations in the absence of fluconazole. This is the first report to demonstrate that resistance to fluconazole can be dependent on chromosomal nondisjunction. Furthermore, we suggest that a low-level resistance to fluconazole arising during the early stages of clinical treatment may occur by this mechanism. These results support our earlier hypothesis that changes in C. albicans chromosome number is a common means to control a resource of potentially beneficial genes that are related to important cellular functions.

Because of the widespread use of fluconazole to treat immunosuppressed candidiasis patients, the frequency of treatment failures due to drug resistance has increased significantly (29, 48). Fluconazole resistance in clinical isolates of Candida albicans has been associated with a combination of several distinct mechanisms (11, 48). These include mutations at the active site of the drug target 14α-sterol demethylase, encoded by the ERG11 gene, the overexpression of ERG11 (39, 44, 47), alterations in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway (18, 39), and the overexpression of the genes involved in energy-dependent drug efflux (2, 11, 38, 48). To date, the overexpression of two C. albicans genes, CDR1 and CDR2, which encode proteins homologous to ATP-binding cassette drug pumps, as well as MDR1 (BENr), which encodes a protein similar to the pumps of the major facilitator superfamily (1, 5, 45), has been associated with fluconazole resistance in clinical isolates (2, 24, 40).

The possibility of changes in electrophoretic karyotypes being associated with fluconazole resistance in clinical C. albicans isolates was investigated in several previous studies (6, 23, 25, 28). No differences in chromosomal patterns were reported. These analyses were limited, however, by the resolution of the chromosomal separation and the lack of a genetic relationship between the resistant and sensitive strains studied. We have recently discovered a novel regulatory principle of gene expression in C. albicans, whereby an alteration in the chromosomal copy number is a mechanism for adaptation under selective pressure (15, 16). We therefore decided to investigate whether C. albicans responds to exposure to fluconazole in a similar fashion. Our approach was to obtain fluconazole-resistant mutants in vitro under defined conditions in a systematic manner with independent subclones and to analyze the chromosomal patterns of the mutants by precise separation with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

Here we report for the first time two specific chromosomal alterations in fluconazole-resistant mutants of C. albicans, apparently formed sequentially by nondisjunction after two times of exposure to the drug. This finding establishes a critical role for chromosomal changes as a possible general response of cells in the development of drug resistance. Together with the fact that a similar regulation was observed for the utilization of different nutrients (15, 32), our results support our earlier hypothesis that changing the chromosome copy number is a novel means of regulating physiologically important genes in C. albicans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nomenclature of C. albicans chromosomes.

In the nomenclature of Wicks et al. (49), which is used in this paper, the penultimate largest to smallest chromosomes are designated by Arabic numerals 1 to 7, whereas the largest chromosome, containing the ribosomal DNA cluster, is designated R. The nomenclature used in our previous publications consists of Roman numerals I to VIII to designate the smallest to the largest chromosomes and a and b to designate two homologues of different sizes. The two types of chromosome assignments can be matched as follows: chromosomes VIII, VII, VI, V, IV, III, II, and I are the same as chromosomes R, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, respectively.

Strains.

C. albicans SGY-243 (ade2/ade2 ura3-Δ::ADE2/ura3-Δ::ADE2) (17) was used to obtain ten independent clones, cn1 to cn10, from which we derived fluconazole-resistant mutants fzD5, fzD7 to fzD10, fzE1 to fzE10, fzF8, and fzF10, as well as corresponding control strains coC1 to coC10, coA5, coA7 to coA10, and coB1 to coB10. The relationship between strains is presented in Fig. 1. C. albicans FR2 is a well-characterized fluconazole-resistant derivative of strain SGY-243, isolated previously (2). C. albicans 3153A, its spontaneous morphological mutants m5, m9, m16, and m18, and l-sorbose- and d-arabinose-utilizing mutants Sor5, Ara4, Ara6, and Ara7 were described previously (32, 34, 35). The electrophoretic karyotypes of C. albicans 3153A and Saccharomyces cerevisiae 867 were used as references in chromosomal separations.

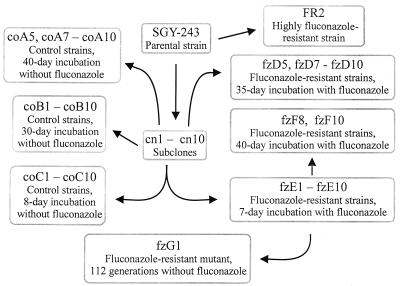

FIG. 1.

Origins and interrelationships of strains clonally derived from C. albicans SGY-243 and used in this study.

Maintenance and storage of strains.

All strains were preserved in a medium containing glycerol (15% [vol/vol]) at −70°C. In order to prevent spontaneous chromosomal instability (34), the strains were maintained as a population by avoiding traditional subcloning, unless required in the experiment. Also, only freshly grown colonies or cultures were used. C. albicans cells were incubated at 37°C, unless indicated otherwise.

Media.

Yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD) and synthetic dextrose (SD) media have been described previously (42). A total of 50 μg of uridine per ml was added as a supplement to SD medium, when necessary (2). Fluconazole was included in SD agar plates at a concentration of 1.0, 1.5, or 2.0 mg/ml to obtain resistant mutants. Antibiotic medium 3 (AM3) was purchased from Difco Laboratories and prepared as recommended by the manufacturer. A stock solution of 10 mg of fluconazole per ml was made in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) immediately prior to use. Fluconazole was a generous gift from Pfizer, Inc.

Isolation of ten independent clones.

In order to obtain a series of fluconazole-resistant mutants of independent origin, which would exclude a comparison of siblings, ten independent clones of C. albicans SGY-243 were prepared. Cells from −70°C stocks were streaked on YPD agar and incubated for 48 h. Ten colonies were arbitrarily selected, cells from each colony were inoculated in separate 15-ml portions of YPD medium, and the cultures were incubated for 16 h. Cells were recovered by centrifugation and deposited in 15% glycerol at −70°C. The subclones were designated cn1 to cn10 (Fig. 1).

Isolation of fluconazole-resistant mutants.

Cells from the cn1 to cn10 strains, representing the ten clones of strain SGY-243, were inoculated into separate cultures (15 ml of YPD medium) and incubated in a rotating shaker for 16 h until the cell density had reached approximately 107 cells/ml. The cells were dispersed by two treatments of 20 s of sonication with an MSE sonicator, operated at the lowest setting and amplitude. Subsequently, the cultures were diluted, and 102, 103, or 104 cells were spread on SD-uridine plates supplemented with 1.0, 1.5, or 2.0 mg of fluconazole per ml, respectively. All mutants chosen for further analysis were obtained on plates with 1.5 mg of fluconazole per ml. Preliminary experiments revealed that fluconazole-resistant mutants did not readily arise on media with lower concentrations of fluconazole. Plates were incubated for 7 days, one-half of an arbitrarily selected colony was used to inoculate 15-ml portions of YPD-fluconazole medium, and the cells were grown for 8 h to provide stocks for storage at −70°C (the fzE series; Fig. 1). The agar plates were left in plastic bags and incubated for a total of 30 to 45 days, and then the other halves of the colonies were used to prepare cell stocks as described above (the fzF series). Also a set of mutants, the fzD series, were prepared by incubating the plates for 35 days.

Isolation of the control strains.

Control strains (Fig. 1) were obtained from the parental subclones cn1 to cn10 in a way similar to that described for the fluconazole-resistant mutants, except that they were grown on a medium lacking fluconazole.

Determination of fluconazole resistance and MICs.

MICs were determined by a microdilution method based on the macrodilution reference method of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (12). Cells from −70°C stocks were inoculated in 10 ml of AM3 and grown for 16 h, and an inoculum of an appropriate cell density was prepared in AM3. Sterile polystyrene 96 microtiter plates were prepared with serial twofold dilutions of fluconazole. After the completion of the serial dilutions, 50 μl of the inoculum was added to each well, resulting in a final concentration 3 × 103 cells/ml and final concentrations of fluconazole from 2,048 to 0.5 μg/ml in a total volume of 100 μl per well. Inoculum-free, as well as fluconazole-free, control wells were included. The plates were sealed with Parafilm and incubated on a rotating shaker (150 rpm) at 35°C for 48 h. Each strain was tested in duplicate on the same plate. A pair of control strains, a parental SGY-243 strain and its highly fluconazole-resistant mutant FR2, was included on each plate. Growth was recorded by scanning the microtiter plates with a microplate reader (MR 7520; Cambridge Technology, Inc.) and a 600-nm filter; in addition, cell densities were noted visually with a mirror.

We also estimated the level of resistance by determining the density of cells at a given concentration of fluconazole, a method that is more revealing at trailing endpoints. The density of cells in the microtiter wells with a fluconazole concentration near the majority of endpoints (128 μg/ml) was determined with a cell-counting chamber.

The inhibitory effect of DMSO alone was determined by examining the growth of strains in liquid media containing various concentrations of this solvent. No inhibition was observed with media containing up to 5% DMSO. A slight inhibition was observed with higher concentrations, corresponding to media containing 512 μg or more per ml in the microtiter plates.

The inhibitory effect of fluconazole was exceedingly more pronounced with liquid media, used in the measurement of growth in microtiter plates, than with agar media, used in the isolation of mutants. While the mutants were isolated on an agar medium containing 1.5 mg of fluconazole per ml, a prominent inhibition of these mutants was observed with a microdilution method with liquid media containing a concentration as low as 4 or 8 μg/ml.

PFGE.

The isolation of intact C. albicans chromosomes was based on an S. cerevisiae protocol (7) and improved by using agarose plugs, which were cast in plug molds (Bio-Rad Laboratories). We used two versions of PFGE, orthogonal field alternating gel electrophoresis (OFAGE) and the contour-clamped homogeneous electric field system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). In order to optimize chromosomal separations, three different running conditions were applied singly or in combinations for the separation of three differently sized groups of chromosomes, as described previously (36). In addition, to optimize the separation of the four smallest chromosomes of strain SGY-243, we used 1.6% agarose gels with an extended electrophoresis of up to 5 days, combined with a 3-min pulse time. Care was taken to load similar amounts of DNA from different strains to achieve a reliable comparison between samples.

Densitometry.

The amount of DNA in bands representing chromosomes was estimated by scanning the negatives of the corresponding photographs with a model GS 700 imaging densitometer (Bio-Rad) and analyzing the data with Molecular Analyst software. A band representing a single copy of a chromosome was identified by comparing its intensity with the chromosomal pattern of reference strain 3153A, and the corresponding intensity value was used to estimate the chromosomal copy number of other bands.

Southern blots and hybridization with chromosomal markers.

Southern blots of separated chromosomes were prepared on nylon filters (Nytran; Schleicher & Schuell) as previously described (37). Chromosomes on Southern blots were identified by hybridization with gene probes that have been mapped to chromosomes (41). The following probes were hybridized with Southern blots by using standard methodologies, and washed under high-stringency conditions (37): MDR1 (BENr [chromosome 6]) (2), ERG11 (chromosome 5) (2), CDR3 (chromosome 4), a 2.7-kb EcoRI fragment (6a), NMT1 (chromosome 4) (with primers 5′AATATGTCGGGAGATAACACAGGG3′ and 5′GGAAACATCTTTCCCAGTCATTGG3′), LYS1 (chromosome 4) (with primers 5′ATGTCTAAATCACCAGTTATTCTTC3′ and 5′CTACTCTTTATCAAGTCTGGCAAC3′), CDR1 (chromosome 3) (2), and CDR2 (chromosome 3) (with primers 5′GTACTGCAAACACGTCTTTGTCG3′ and 5′GTCGTCTGGTTTCTTCAATTTATTG3′). Where primers are given, the probes were amplified from C. albicans ATCC 10261 DNA.

Gene expression measurements.

The expression of chromosomal marker genes was measured by RNA dot blot analysis as described previously (2). The amounts of specific mRNAs from each strain were measured relative to the amount of ACT1 mRNA.

RESULTS

Strains used in this study.

The choice of a parental strain for investigating fluconazole resistance was hampered by the natural resistance of many commonly used laboratory strains. In this study, we have chosen SGY-243 because it was used in previous studies of fluconazole-resistant mutants (18) and because it contains a ura3 marker, which permits the convenient cloning of genes and other molecular manipulations.

The resistant mutants analyzed in the study were obtained by incubating SGY-243 cells for up to 40 days on a medium containing 1.5 mg of fluconazole per ml. Mutant frequencies were exceedingly high, ranging from 10 to 50%. These high frequencies of fluconazole-resistant mutants could be due to the residual growth of the sensitive cells on fluconazole plates or possibly to adaptive mutagenesis (see reference 16).

The collection of mutants derived after a short (fzE1 to fzE10) or long (fzD5, fzD7 to fzD10, fzF8, and fzF10) exposure to fluconazole is presented in Fig. 1. The long-exposure mutants were obtained in two different series, fzE and fzF, as outlined in Fig. 1. The corresponding control strains (coA5, coA7 to coA10, coB1 to coB10, and coC1 to coC10) obtained from SGY-243 on SD-uridine medium without fluconazole are also presented in Fig. 1. A stable fluconazole-resistant mutant FR2, derived from strain SGY-243, was partially analyzed previously (2). A significant feature of FR2 is that the fluconazole MIC for it is 64-fold higher than that for SGY-243. FR2 and SGY-243 were used as a pair of reference strains in broth microdilution tests. In addition, the electrophoretic karyotype of FR2 was determined and compared to mutants obtained in this study. C. albicans 3153A and its spontaneous (m5, m9, m16, and m18) and selected (Sor5, Ara4, Ara6, and Ara7) mutants have been studied extensively for changes in chromosomal patterns (reviewed in reference 33) and were used as additional control strains in broth microdilution tests.

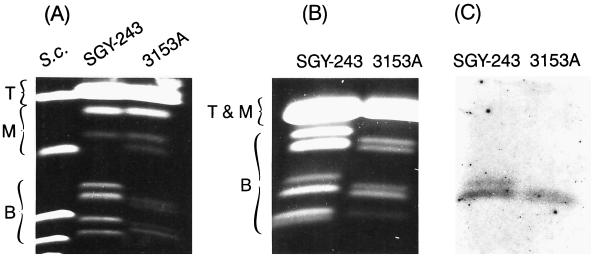

Electrophoretic karyotype of the parental strain C. albicans SGY-243.

The chromosomes of C. albicans SGY-243 were characterized by comparison of the band positions and quantitative intensities with the well-characterized electrophoretic karyotype of the reference strain 3153A (34, 35) (Fig. 2 and 3). In addition, approximately one-half of the chromosomes was identified by hybridization with chromosomal probes (41). Strain SGY-243, like all the other C. albicans laboratory strains and fresh isolates analyzed to date (3, 22, 34, 43), was found to have a unique electrophoretic karyotype. The banding pattern of SGY-243 was more complex than that of 3153A, in that it contained six additional chromosomes in the positions of chromosomes 4, 5, 6, and 7 (Fig. 3). This multiple aneuploidy either could be natural or could have been induced by exposure to UV light (17), formed under laboratory cultivation, or acquired by improper storage (see, for example, reference 35). In addition, chromosome R was represented by an inseparable cloud of weakly staining bands instead of two homologues as for 3153A. This has been described previously (36) and indicates a highly heterogeneous population of chromosome R molecules, probably due to the unequal lengths of rDNA unit clusters (31). This condition of chromosome R is indicative of genomic instability. It may also be that mutagenic genetic manipulations, such as transformations, have affected the chromosomal pattern by increasing chromosomal instability. Indeed, we found that chromosome R of C. albicans CAI4, which like SGY-243, has been transformed several times (10), also had a very diffuse chromosome R band (29).

FIG. 2.

Electrophoretic karyotype of the parental strain, C. albicans SGY-243. Chromosomes were separated by orthogonal field alternating gel electrophoresis (OFAGE) under conditions to accentuate the separations of either the bottom (B) and middle (M) groups of chromosomes (A) or the bottom but not the other groups (B). These conditions of separation do not resolve the top group (T) of large chromosomes. C. albicans 3153A was used as a reference electrophoretic karyotype, and S. cerevisiae 867 chromosomes (S.c.) were used as size markers. (C) Autoradiogram of chromosome blot hybridized with the MDR1 probe.

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of electrophoretic karyotypes of two laboratory strains, SGY-243 and 3153A, and fluconazole-resistant mutants of SGY-243. Three groups of C. albicans chromosomes, bottom (B), middle (M), and top (T), can be resolved singly or in combinations by three different electrophoresis conditions. The chromosomes’ numbers, 1 to 7 and R, and homologues, a or b, are presented. The assignment of chromosomes to individual bands for the reference electrophoretic karyotype of 3153A and their approximate sizes, as well as the rationale for identifying the eight pairs of chromosomes, have been previously published (31, 34, 35). Some of the markers used in this study for hybridizing to 3153A chromosomes are indicated. Chromosomes were identified by the similarity of positions and intensity of bands to those of the reference karyotype of 3153A and by hybridization with the following chromosome probes (numerals in circles): 1, MDR1 (Benr); 2, ERG11; 3, CDR3; 4, NMT1; 5, LYS1; 6, CDR1; and 7, CDR2. Each chromosome copy number, presented in square brackets, was determined by densitometry. Dotted, thin, and thick lines correspond, respectively, to one, two, and three or more chromosomes. The array of thin lines for chromosome R represents a cloud of inseparable weakly stained bands. The changes of chromosome R observed in some mutants obtained in this study are not shown. The chromosome patterns of the resistant mutants that differ from SGY-243 are indicated. The ERG11 gene probe did not hybridize with chromosome 5a in strain 3153A (*), possibly due to a deletion. The LYS1 gene probe also hybridized to a band in the top group for SGY-243 (†). A single mutant, fzE5, retained only one homologue of 4a instead of two (‡).

In spite of the limited assignment of SGY-243 chromosomes with chromosomal probes, presented in Fig. 3, the results were sufficient to make direct comparisons with fluconazole-resistant progeny and allowed chromosome assignments of genes most commonly associated with the development of fluconazole resistance by clinical isolates, ERG11 (38, 44), CDR1, CDR2, and MDR1 (2, 11, 24, 38, 40).

Electrophoretic karyotypes of fluconazole-resistant mutants, isolated from strain SGY-243 after short and long exposures to drug, and control strains.

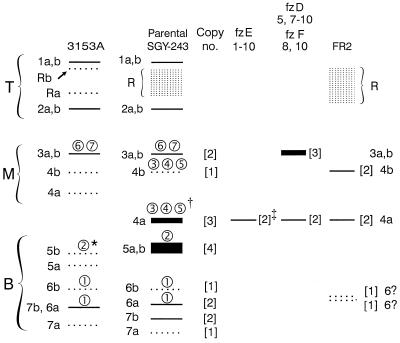

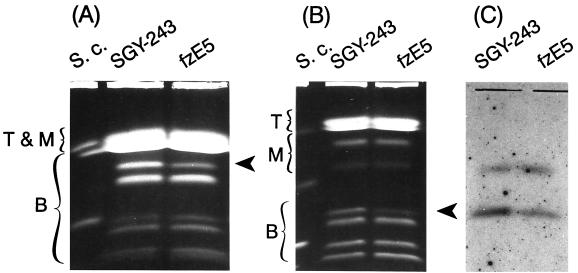

We analyzed the electrophoretic karyotypes of all 17 independently derived mutant strains, fzE1 to fzE10, fzD5, fzD7 to fzD10, fzF8, and fzF10, as well as the sixteen corresponding control strains coA5, coA7 to coA10, coB1, and coC1 to coC10 (Fig. 1). All mutants obtained after a 7-day exposure to fluconazole, fzE1 to fzE10, had lost one of the three homologues in the position of chromosome 4a (Fig. 4), as determined by densitometric analysis and hybridization signals with probes of the two genes, NMT1 and CDR3 (Fig. 3 and 4C). Two homologues of chromosome 4a were lost in one mutant, fzE5. No gene currently associated with fluconazole resistance maps to this chromosome. The gene CDR3, which is located on chromosome 4, although highly similar to genes CDR1 and CDR2, is not thought to be involved in fluconazole resistance (4). All seven strains, fzD5, fzD7 to fzD10, fzF8, and fzF10, obtained after a long exposure of 35 or 40 days to fluconazole became trisomic for chromosome 3 (Fig. 5), apparently as a result of duplication of one of the homologues (Fig. 3 and 5B), as well as having a reduction in the copy number of chromosome 4a. Because some, but not all, of the mutants had changes in chromosome R, these alterations were not considered to be specific and arose as a result of the generally higher instability of this particular chromosome, a subject earlier addressed by us and other laboratories (see this work and reference 31). The chromosomal patterns of all control strains were identical to that for the parental strain SGY-243.

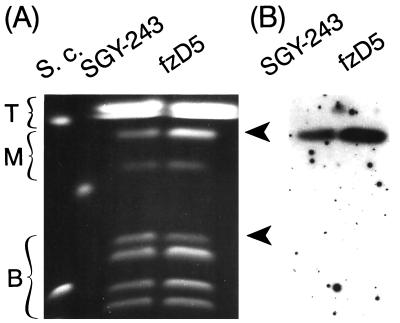

FIG. 4.

Electrophoretic karyotype of the representative fluconazole-resistant mutant fzE5, obtained after 7 days of exposure to fluconazole. Electrophoretic karyotypes obtained under two different OFAGE conditions, which accentuated the separations of different size chromosomes (Fig. 2) are shown (A and B). Arrows indicate chromosome 4a, in which two of three copies are lost. Note that no other detectable chromosomal changes are seen in these separations. Top (T), Middle (M), and bottom (B) chromosomes are indicated. S.c., S. cerevisiae 867 chromosomal size markers. (C) Autoradiogram of blot hybridized with the CDR3 probe, corroborating the loss of two copies of chromosome 4a.

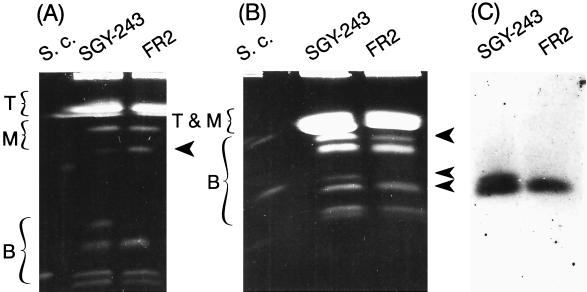

FIG. 5.

The electrophoretic karyotype of the representative fluconazole-resistant mutant fzD5, obtained after 35 days of exposure to fluconazole. (A) The electrophoretic karyotype obtained by the OFAGE condition that accentuated the separations of the bottom (B) and middle (M) groups of chromosomes. Arrows indicate two specific chromosomal changes, the loss of two of three copies of chromosome 4a and an increase of one copy of chromosome 3. T, top chromosomes; S.c., S. cerevisiae 867 chromosomal size markers. (B) Autoradiogram of blot hybridized with the CDR1 probe, corroborating an increase in the copy number of chromosome 3.

Electrophoretic karyotype of highly fluconazole-resistant mutant FR2.

The electrophoretic karyotype of the fluconazole-resistant mutant FR2, previously isolated from strain SGY-243 (2), was determined (Fig. 6). In addition to the loss of one homologue of chromosome 4a, shown by all fluconazole-resistant mutants isolated in this study, the FR2 karyotype had four more changes than the parental strain (Fig. 3). These included a duplication of chromosome 4b, an apparent loss of chromosome 6b, and an increase in the size of one homologue of chromosome 6a, presumably due to an insertion. An alternative interpretation of the banding pattern is that one copy of chromosome 6a was lost and chromosome 6b experienced a deletion. The last change constituted an altered pattern of the faint bands representing chromosome R. Although we previously showed that the majority of length alterations of this chromosome were due to differences in the number of ribosomal DNA units in the cluster (31) the instability of this chromosome is not completely understood. Chromosome R alterations may be under the control of the same mechanism that acts on other chromosomes (31).

FIG. 6.

Electrophoretic karyotype of the highly fluconazole-resistant mutant FR2. OFAGE separations of top (T), middle (M), and bottom (B) chromosomes (as described in the legend to Fig. 2). S.c., S. cerevisiae 867. The arrows indicate some visible changes in chromosomal patterns of FR2. (C) Autoradiogram of blot hybridized with the MDR1 probe, indicating a change in the position of chromosome 6b, as well as a reduction in copy number.

Fluconazole sensitivity of strain SGY-243, control strains, and mutants isolated after short or long exposure.

Typical broth microdilution tests with fluconazole media were used to compare the growth of the parental strain SGY-243, the seventeen fluconazole-resistant derivatives (fzE1 to fzE10, fzD5, fzD7 to fzD10, fzF8, and fzF10), the sixteen control strains (coC1 to coC10, coB1 to coB10, coA5, and coA7 to coA10) and a highly resistant mutant FR2, which was previously published (2) (Fig. 1). There was variation in the growth curves between independent measurements of the same strain, but the growth of all fluconazole-resistant mutants generally fell between the values for the parental strain SGY-243 and the highly resistant mutant FR2. Representative growth curves for each group, short-exposure mutants, fzE9 and fzE10, and long-exposure mutants, fzD9 and fzD10, are shown in Fig. 7. All of the mutants exhibited a distinct trailing endpoint due to growth at high drug concentrations. Although the determination of standard MICs at which 80 or 50% of the growth of isolates is inhibited may be an inappropriate way to assess resistance to fluconazole, the overall growth responses (Fig. 7) differentiated between the resistant mutants and the parental and control strains. Cell clumping and reduced growth rates, the common consequences of chromosomal alterations (35), were observed in all of the mutants. Thus, the final densities of cells in the various concentrations of fluconazole reflect not only resistance but also a general diminution of growth due to the chromosomal alterations. Although the high variations in the growth response curves did not permit a clear distinction between the different types of resistant mutants, mutants obtained after a short exposure to fluconazole generally seemed to show a lower growth yield than the mutants obtained after a long exposure.

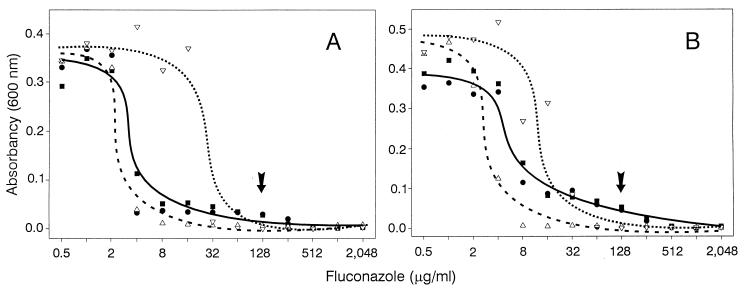

FIG. 7.

Growth of resistant mutants after 48 h in media containing different concentrations of fluconazole, compared with the growth of the parental strain SGY-243 (▵) and the reference resistant mutant FR2 (▿). (A) Representative mutants fzE9 (●) and fzE10 (■) obtained after a short 7-day exposure to fluconazole. (B) Representative mutants fzD9 (●) and fzD10 (■) obtained after a long 35-day exposure to fluconazole. Arrows indicate the fluconazole concentration at which cell counts were taken for each strain. Note that each pair of resistant mutants is represented by a single curve because of their similar growth responses.

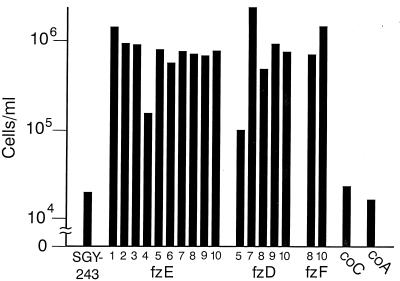

The determination of the numbers of cells after growth in a single concentration of fluconazole is another measure of resistance. The numbers of cells after 2 days of growth in a medium containing 128 μg of fluconazole/ml was determined with a cell-counting chamber (Fig. 8). There were up to 2 orders of magnitude more cells of the resistant mutants than the parental strain SGY-243 and the control strains, although at this high concentration, close to the trailing endpoints (Fig. 7), the mutants obtained after a short or long exposure could not be differentiated. The control strains had approximately the same cell density as the parental strain SGY-243.

FIG. 8.

Sensitivities of strains to fluconazole. Cell densities are presented for strain SGY-243, the control strains, and the resistant mutant after growth in the presence of 128 μg/ml of fluconazole. Cell densities were determined with a cell-counting chamber. Each value is a mean of two to four determinations for mutants and 17 determinations for SGY-243.

Stability of fluconazole-resistant mutants.

The stability of the fluconazole resistance phenotype was determined. An arbitrarily chosen fluconazole-resistant mutant, fzE6, was cultivated in YPD liquid medium without fluconazole with transfers every 12 h into fresh medium for approximately 112 generations. The electrophoretic karyotype of this potential revertant, fzG1 (Fig. 1), remained stable and similar to that for fzE6 (data not presented). The fluconazole sensitivity of fzG1, as well as corresponding levels of gene expression (see below), also remained constant after growth in the absence of fluconazole. The stability of the highly fluconazole-resistant mutant FR2 was reported earlier (2) and confirmed in this study (data not presented).

Fluconazole sensitivity of C. albicans morphological and l-sorbose- or d-arabinose-utilizing mutants.

In order to investigate the specificity of chromosomal alterations for fluconazole resistance, the broth microdilution test with fluconazole media was used to obtain growth curves of eight previously well-characterized C. albicans 3153A mutants that each have either a spontaneous or a selected alteration of their chromosomes. The morphological mutants m5, m9, m16, and m18 each have two or three changes in different chromosomes, and the l-sorbose- or d-arabinose-utilizing mutants Sor5, Ara4, Ara6, and Ara7 have changes in chromosomes 5 and 6 and chromosome 2, respectively (32, 35). The fluconazole sensitivities of all these mutants were similar to that of the parental strain 3153A (data not presented).

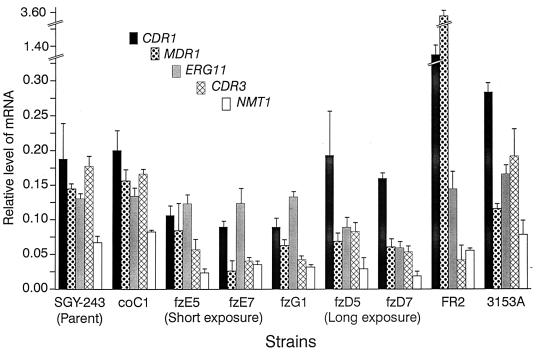

Transcript levels in fluconazole-resistant mutants and control strains.

In order to determine whether an altered chromosomal copy number affected transcript levels for genes on those chromosomes and whether genes already implicated in fluconazole resistance were overexpressed in our resistant mutants, the amounts of mRNAs for six genes were measured relative to ACT1 mRNA (Fig. 9). No CDR2 mRNA was detected in any of the fluconazole-resistant mutants or the parental strain SGY-243, as previously reported (24). The mRNA levels of the four control strains that were analyzed, coC1 to coC4, were similar to the levels in SGY-243 (coC1; Fig. 9). Mutants obtained after a short exposure to fluconazole showed slightly reduced amounts of CDR1 and substantially reduced amounts of MDR1, CDR3, and NMT1 mRNAs but the normal level of ERG11 mRNA, which encodes a fluconazole target. The reduction in CDR3 and NMT1 mRNAs reflects the reduction in the number of chromosome 4 homologues in these strains (Fig. 3). Strain fzG1, which was derived from resistant mutant fzE6 after growth in the absence of fluconazole, showed a transcript pattern similar to that of the fzE class of mutant, consistent with other characteristics that also did not change, such as the electrophoretic karyotype and the growth curves. Mutants isolated after a longer exposure to fluconazole showed a similar transcript pattern to the short-exposure mutants, except that the level of the CDR1 mRNA was restored to the level corresponding to that in the parental strain SGY-243, apparently because of the acquisition of the third copy of the gene due to the duplication of a chromosome 3 homologue. Also, the level of ERG11 mRNA was diminished, similar to the other genes. The FR2 mutant showed increased transcription of CDR1 and MDR1, as previously described (2). The substantial overexpression of MDR1 may be due to rearrangements on chromosome 6, which carries this gene, to the other chromosomal alterations, or to a combination of these changes (Fig. 3). C. albicans 3153A showed a slight overexpression of CDR1 mRNA, but this was within the range obtained for other fluconazole-sensitive C. albicans strains (24).

FIG. 9.

The levels of CDR1, MDR1, ERG11, CDR3, and NMT1 mRNAs in C. albicans strains relative to the levels of ACT1 mRNA. Dots blots of total RNA were hybridized with each of the five radiolabelled probes. Results are the means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three determinations. No CDR2 mRNA was detected in any strain. Four control strains were analyzed, each gave a similar result, and a representative strain, coC1, is shown. Two potential revertant strains were analyzed, both gave the same result, and one, fzG1, is shown.

DISCUSSION

The resistance to toxic agents can be due to the overexpression of certain pertinent genes because of their increased copy number. For example, gene duplication confers multidrug resistance of mammalian tumor cell lines that have been selected by growth in the presence of drugs (13). The resistance of S. cerevisiae, Candida glabrata, or Chinese hamster cells to heavy metals involves the tandem amplification of the metallothionein genes (8, 14, 21). On the other hand, the overexpression of the CDR1, CDR2, and MDR1 genes was associated with fluconazole resistance in C. albicans (2, 9, 11, 27, 40, 46, 48). The mechanisms resulting in the overexpression of these genes are not fully understood, and it is uncertain that the entire repertoire of fluconazole genes have been identified. In some clinical isolates having high levels of fluconazole resistance (2, 38), there was a concomitant overexpression of more than one putative efflux pump (24), overexpression of ERG11, which encodes the drug target 14α-sterol demethylase, mutations of ERG11, and other changes in the sterol biosynthetic pathway (39, 44, 46, 47).

We report here for the first time nondisjunctions of two specific chromosomes associated with tolerance to fluconazole as possibly a general response of C. albicans cells to exposure to the drug on a selective plate.

Chromosomal analysis was performed on a group of 17 fluconazole-resistant mutants, each of them obtained by an independent event from the parental strain SGY-243, in order to avoid the analysis of siblings. A common chromosomal change, the loss of one of the three shorter homologues of chromosome 4, apparently due to nondisjunction, occurred in all resistant mutants (Fig. 3 to 5). The exclusive loss of the shorter homologue is indicative of a sequence on the longer homologue that is indispensable for viability or fluconazole resistance.

None of the genes known to date to be associated with fluconazole resistance is situated on chromosome 4. The implication of the specific chromosomal nondisjunction under antifungal selective pressure, which was reproducibly observed in independent experiments, is consistent with our previous finding, where we proved a causal relationship between the copy number of chromosome 5 and the expression of the structural gene for l-sorbose utilization, SOU1, located on a different chromosome (15).

Similarly, a second specific change occurred in all seven mutants isolated after prolonged growth in the presence of fluconazole but not in the 10 mutants exposed for only 7 days. This was a trisomy of chromosome 3, which carries at least two genes associated with fluconazole resistance, CDR1 and CDR2 (Fig. 3 and 5). An expected consequence of this chromosomal amplification would be an increase in the copy number of all genes on this chromosome. In one case, the fluconazole resistance of a C. glabrata isolate has been related to the duplication of the chromosome carrying the ERG11 gene encoding the fluconazole target. We wish to emphasize that this duplication resulted in the altered expression of approximately 100 proteins, including the overexpression of ERG11 (20).

We found that the levels of gene expression associated with fluconazole resistance either remained the same (ERG11 mRNA, as well as CDR2 mRNA, which was not expressed in all strains) or were diminished (CDR1 and MDR1) (Fig. 9). The CDR1 mRNA level, however, was restored to the original amount in the long-exposure mutants, in accordance with the increased copy number of chromosome 3. In contrast, the level of ERG11 mRNA diminished, similar to other mRNAs in the long-exposure mutants. One explanation of the lower expression levels of CDR1, located on chromosome 3, and the lower expression levels of MDR1, located on chromosome 6, is that chromosome 4, which is diminished to one copy, carries a positive regulator(s) of these genes. Also, the lower expression levels of ERG11, located on chromosome 5, can be explained by the presence of a negative regulator located on chromosome 3, which is increased by one copy in the long-exposure mutants. Taken together with the pronounced decrease of expression of the control genes, MNT1 and CDR3, on chromosome 4, which loses a copy, the alterations in the expression of genes implicated with the resistance could be explained by changes in the copy number of chromosomes carrying structural genes, as well as their positive or negative regulators. The overexpression of CDR1 in the long-exposure mutants, in comparison to the short-exposure mutants, is the only example consistent with previous reports that the expression of a gene encoding an efflux pump affects fluconazole resistance (see above).

Although it was not absolutely evident that mutants with two changes in their electrophoretic karyotypes had higher levels of resistance than mutants with only one change, it seems as though the loss of one chromosome 4 homologue is a rapid general response, which provides cells with a certain low but sufficient level of resistance, and the additional trisomy of chromosome 3, which occurs under prolonged exposure, may have produced cells with the next level of resistance.

A possible explanation for the lack of a substantial overproduction of known drug pumps or targets would be that the loss of one chromosome 4 caused a change in the expression of some still unidentified pertinent gene(s) responsible for fluconazole resistance. Furthermore, this loss of chromosome 4 may also be responsible for the diminished level of expression of CDR1, producing a slight reduction in resistance but still causing more resistance overall than the parental strain. The second change, the gain of one copy of chromosome 3, may have produced an increase in resistance by returning the level of expression of CDR1 to normal.

One can also consider the possibility that the normally expressed known genes, such as CDR1, are more effective in producing resistance because of an interaction with any number of gene products, whose expression levels are altered because of changes in chromosome copy number.

Significantly, none of the eight mutants of strain 3153A possessing various chromosomal alterations (see Results) were altered in their sensitivities to fluconazole. In addition, clonally related control strains examined in this study (Fig. 1) were equivalent to the parental strain in regard to fluconazole sensitivity, karyotypes, and expression of the genes considered in this work.

In the same way, mutant FR2, which has a higher level of fluconazole resistance than the mutants isolated in this study, had more chromosomal alterations. Its resistance can be viewed as a result of complex multiple chromosomal changes which combined chromosomal nondisjunctions with deletions. The data presented in this study cannot preclude gene mutations affecting gene expression and drug resistance.

There is remarkable similarity between the results reported in this paper and the results obtained with patients undergoing treatment with fluconazole. A number of independent studies revealed that series of C. albicans strains isolated sequentially in time from patients showed a progressive increase of resistance and that the overexpression of efflux pumps or point mutations of the target gene, ERG11, was not initially manifested or, in fact, did not appear at all during the study (19, 38, 46). In one of these studies of five different patients (19), sequentially obtained fluconazole-resistant mutants from one patient did not exhibit overexpression of MDR1, CDR1, or CDR2, and the mutants did not have point mutations in the ERG11 gene, even though strains were isolated and tested for a period extending to nearly 10 months. Strains from the other patients showed an alternation in the overexpression of the MDR1 and CDR genes. Thus, our laboratory study and the clinical studies both reveal that at early stages of infection, fluconazole resistance arises by mechanisms other than the overexpression of known efflux pumps or the mutation of a target gene. Because the chromosomal nondisjunction produced high frequencies of low-level fluconazole-resistant mutants, it is reasonable to suggest that a similar alteration is causing resistance under clinical treatments.

Chromosomal nondisjunction, leading to either the loss or gain of the copy number of chromosomes, is a common and well-tolerated phenomenon in lower fungi. By investigating the utilization of nutrients, we established a new principle of regulation in C. albicans based on the change of chromosome copy number (15). The ability to utilize l-sorbose occurs through the reduction of one copy of chromosome 5, which in turn activates the expression of SOU1, which encodes l-sorbose reductase and which is located on a different chromosome. In another example, either the loss of chromosome 7 or the gain of chromosome 3 was required for the assimilation of d-arabinose in each of two groups of d-arabinose-positive mutants (30, 32). The results presented in this paper provide further confirmation for the regulatory role of chromosome copy number and strengthen the generalization of this phenomenon. Because the chromosome copy number controlled l-sorbose utilization in two different laboratory strains, we believe that a specific chromosomal nondisjunction may also be a general means to produce fluconazole resistance in C. albicans, although different strains may involve different chromosomes. In addition, our findings clearly show that under selective pressure on an agar plate, a single strain can gradually develop drug resistance. In the clinical situation, a similar process could establish an infection which does not respond to antifungal therapy.

The discovery of nondisjunction as a possible general response controlling drug resistance, together with the fact that the same type of regulation was observed for the utilization of different food supplies, supports our hypothesis that a change in the copy number of a chromosome is a common means to control a resource of potentially beneficial genes that are involved in important physiological functions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mark Dumont (University of Rochester) for valuable discussions.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Science research grant AI22963 from the National Institutes of Health and by American Cancer Society Institutional research grant IRG-18-38. R.D.C. acknowledges financial support from the New Zealand Lottery Board and the Health Research Council of New Zealand. The fluconazole used in this study was a generous gift from Pfizer, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alarco A M, Balan I, Talibi D, Mainville N, Raymond M. AP1-mediated multidrug resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires FLR1 encoding a transporter of the major facilitator superfamily. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19304–19313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albertson G D, Niimi M, Cannon R D, Jenkinson H. Multiple efflux mechanisms are involved in Candida albicans fluconazole resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2835–2841. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asakura K, Iwaguchi S-I, Homma M, Sukai T, Higashide K, Tanaka K. Electrophoretic karyotypes of clinically isolated yeasts of Candida albicans and C. glabrata. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2531–2538. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-11-2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balan I, Alarco A-M, Raymond M. The Candida albicans CDR3 gene codes for an opaque-phase ABC transporter. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7210–7218. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7210-7218.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balzi E, Goffeau A. Genetics and biochemistry of yeast multidrug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1187:152–162. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bart-Delabesse E, Boiron P, Carlotti A, Dupont B. Candida albicans genotyping in studies with patients with AIDS developing resistance to fluconazole. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2933–2937. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2933-2937.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Cannon, R. D. Unpublished data.

- 7.Carle G F, Olson M V. An electrophoretic karyotype of yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3756–3759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford B D, Enger M D, Griffith B B, Griffith J K, Hanners J L, Longmire J L, Munk A C, Stallings R L, Tesmer J G, Walters R A, Hildebrand C E. Coordinate amplification of metallothionein I and II genes in cadmium-resistant Chinese hamster cells: implications for mechanisms regulating metallothionein gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:320–329. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fling M E, Kopf J, Tamarkin A, Gorman J A, Smith H A, Koltin Y. Analyses of a Candida albicans gene that encodes a novel mechanism for resistance to benomyl and methotrexate. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;227:318–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00259685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonzi W A, Irwin M Y. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franz R, Kelly S L, Lamb D C, Kelly D E, Ruhnke M, Morschhäuser J. Multiple molecular mechanisms contribute to a stepwise development of fluconazole resistance in clinical Candida albicans strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3065–3072. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fromtling R A, Galgiani J N, Pfaller M A, Espinel-Ingroff A, Bartizal K F, Bartlett M S, Body B A, Frey C, Hall G, Roberts G D, Nolte F B, Odds F C, Rinaldi M G, Sugar A M, Villareal K. Multicenter evaluation of a broth macrodilution antifungal susceptibility test for yeasts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:39–45. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottesman M M, Hrycyna C A, Schoenlein P V, Germann U A, Pastan I. Genetic analysis of the multidrug transporter. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:607–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.003135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamer D H, Thiele D J, Lemontt J E. Function and autoregulation of yeast copperthionein. Science. 1985;228:685–690. doi: 10.1126/science.3887570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janbon G, Sherman F, Rustchenko E. Monosomy of a specific chromosome determines l-sorbose utilization: a novel regulatory mechanism in Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5150–5155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janbon, G., F. Sherman, and E. Rustchenko. Appearance and properties of l-sorbose utilizing mutants of Candida albicans obtained on a selective plate. Genetics, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Kelly R, Miller S M, Kurtz M B, Kirsch D R. Directed mutagenesis in Candida albicans: one-step gene disruption to isolate ura3 mutants. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:199–208. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly S L, Lamb D C, Kelly D E, Manning N J, Loeffler J, Hebart H, Schumacher U, Einsele H. Resistance to fluconazole and cross-resistance to amphotericin B in Candida albicans from AIDS patients caused by defective sterol Δ (5,6) desaturation. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:80–82. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez-Ribot J L, McAtee R K, Lee L N, Kirkpatrick W R, White T C, Sanglard D, Patterson T F. Distinct patterns of gene expression associated with development of fluconazole resistance in serial Candida albicans isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2932–2937. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marichal P, Vanden Bossche H, Odds F C, Nobels G, Warnock D W, Timmerman V, Van Broeckhoven C, Fay S, Mose-Larsen P. Molecular biological characterization of an azole-resistant Candida glabrata isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2229–2237. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehra R K, Garey J R, Winge D R. Selective and tandem amplification of a member of the metallothionein gene family in Candida glabrata. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6369–6375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mertz W G, Connelly C, Hieter P. Variation of electrophoretic karyotypes among clinical isolates of Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:842–845. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.5.842-845.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Millon L, Manteaux A, Reboux G, Drobacheff C, Monod M, Barale T, Michel-Briand Y. Fluconazole-resistant recurrent oral candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients: persistence of Candida albicans strains with the same genotype. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1115–1118. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1115-1118.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niimi M, Cannon R D, Arisawa M. Multidrug resistance genes in Candida albicans. Jpn J Med Mycol. 1997;38:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfaller M A, Rhine-Chalberg J, Redding S W, Smith J, Farinacci G, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. Variations in fluconazole susceptibility and electrophoretic karyotype among oral isolates of Candida albicans from patients with AIDS and oral candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:59–64. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.59-64.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pla J, Gil C, Monteoliva L, Navarro-Garcia F, Sanchez M, Nombela C. Understanding Candida albicans at the molecular level. Yeast. 1996;12:1667–1702. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199612)12:16%3C1677::AID-YEA79%3E3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasad R, De Wergifosse P, Goffeau A, Balzi E. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel gene of Candida albicans, CDR1, conferring multiple resistance to drugs and antifungals. Curr Genet. 1995;27:320–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00352101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redding S, Smith J, Farinacci G, Rinaldi M, Fothergill A, Rhinechalberg J, Pfaller M. Resistance of Candida albicans to fluconazole during treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in a patient with AIDS—documentation by in vitro susceptibility testing and DNA subtype analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:240–242. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruhnke M, Eigler A, Tennagen I, Geiseler B, Engelmann E, Trautmann M. Emergence of fluconazole-resistant strains of Candida albicans in patients with recurrent oropharyngeal candidosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2092–2098. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2092-2098.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rustchenko, E. Personal communication.

- 31.Rustchenko E P, Curran T M, Sherman F. Variations in the number of ribosomal DNA units in morphological mutants and normal strains of Candida albicans and in normal strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7189–7199. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7189-7199.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rustchenko E P, Howard D H, Sherman F. Chromosomal alterations of Candida albicans are associated with the gain and loss of assimilating functions. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3231–3241. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3231-3241.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rustchenko E P, Howard D H, Sherman F. Variation in assimilating functions occurs in spontaneous Candida albicans mutants having chromosomal alterations. Microbiology. 1997;143:1765–1778. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-5-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rustchenko-Bulgac E P. Variations of Candida albicans electrophoretic karyotypes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6586–6596. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6586-6596.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rustchenko-Bulgac E P, Sherman F, Hicks J B. Chromosomal rearrangements associated with morphological mutants provide a means for genetic variation of Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1276–1283. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1276-1283.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rustchenko-Bulgac E P, Howard D H. Multiple chromosomal and phenotypic changes in spontaneous mutants of Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1195–1207. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-6-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanglard D, Kuchler K, Ischer F, Pagani J L, Monod M, Bille J. Mechanisms of resistance to azole antifungal agents in Candida albicans isolates from AIDS patients involve specific multidrug transporters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2378–2386. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanglard D, Ischer F, Koymans L, Bille J. Amino acid substitutions in the cytochrome P-450 lanosterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51A1) from azole-resistant Candida albicans clinical isolates contribute to resistance to azole antifungal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:241–253. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanglard D, Ischer F, Monod M, Bille J. Cloning of Candida albicans genes conferring resistance to azole antifungal agents: characterization of CDR2, a new multidrug ABC transporter gene. Microbiology. 1997;143:405–416. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scherer, S. 15 March 1999, revision date. [Online.] http://alces.med.umn.edu/Candida/html. [24 January 1999, last date accessed.]

- 42.Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. In: Guthrie C, Fink G R, editors. Methods in enzymology. 194. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 3–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thrash-Bingham C, Gorman J A. DNA translocations contribute to chromosome length polymorphism in Candida albicans. Curr Genet. 1992;22:93–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00351467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vanden Bossche H, Marichal P, Gorrens J, Bellens D, Moereels H, Janssen P A J. Mutation in cytochrome P450-dependent 14α-demethylase results in decreased affinity for azole antifungals. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990;18:56–59. doi: 10.1042/bst0180056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Veen H W, Konings W N. Multidrug transporters from bacteria to man: similarities in structure and function. Semin Cancer Biol. 1997;8:183–191. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1997.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White T C. Increased mRNA levels of ERG16, CDR, and MDR1 correlate with the increases in azole resistance in Candida albicans isolates from a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1482–1487. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White T C. The presence of an R467K amino acid substitution and loss of allelic variation correlate with an azole-resistant lanosterol 14α-demethylase in Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1488–1494. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White T C, Marr K A, Bowden R A. Clinical, cellular, and molecular factors that contribute to antifungal drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:382–402. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wicks B, Staudinger J, Magee B B, Kwon-Chung K-J, Magee P T, Sherer S. Physical and genetic mapping of Candida albicans: several genes previously assigned to chromosome 1 map to chromosome R, the rDNA-containing linkage group. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2480–2484. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2480-2484.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]