Abstract

This study provides much-needed empirical study of workplace inclusion of underresourced employees of low socioeconomic status. Based upon a conservation of resources perspective, we have examined the centrality of resources as a key inclusion process for well-being outcomes for employees with insufficient resources. In the context of misuse of institutional power over operative workers within highly segmented and hierarchical work settings, this study validates the importance of economic inclusion for fostering workers’ well-being via fair employment practices. This study also offers new knowledge of the integrative resource model of workplace inclusion research by validating workers’ personal resources of learning orientation as an internal condition for strengthening the positive effect of economic inclusion on well-being.

Keywords: Workplace inclusion, Reduced inequality, Conservation of resource perspective

Introduction

Almost half of humanity lives on less than USD 5.50 a day. They are increasingly resource deprived to achieve their economic and social well-being (Oxfam International, 2021). To create a more equitable society, business leaders need to establish more inclusive workplaces for resource-deprived workers. While resource accessibility and integration are paramount to reduce inequality for those workers, we know little about what and how resources ought to be distributed in workplaces. Workplace inclusion for workers with a low socioeconomic status is significantly underresearched. By adopting the conservation of resources (COR) theory, which promotes economic, social, and personal resources relevant to workplace inclusion (Hobföll, 2002; Hobföll et al., 2018), this study explores how managers may grant workers equal access to their valuable resources. According to the sociological approach to workforce inclusion, we regard resources and inclusion as closely related concepts that are particularly important for underresourced workers. Notably, status construction theory suggests that individuals’ resource accessibility reinforces the differentiation of shared identity and social values attached to individuals in society (Ridgeway, 1991; Ridgeway & Correll, 2006). The low social value that resourced members project onto less-resourced members reinforces their limited access to resources as the vicious cycle of resource distribution (c.f., Bapuji et al., 2018). This becomes particularly salient in a highly segmented and hierarchical work system such as that of the Bangladeshi factories in the Global South, operating under the global production network (Alamgir et al., 2021; DiTomaso et al., 2007). Underpinned by this sociological perspective to workforce diversity, Mor Barak and Cherin (1998) define inclusion as the degree to which individuals feel they can access resources and information as part of organizational processes; and Nishii (2013) defines a climate of inclusion as employee-shared perceptions of a work environment that grants every worker (regardless of background) equal access to resources via fair employment practices and inclusive interactions.

Prior inclusion studies have mainly solicited data from HR professionals, skilled employees, and managers in relation to employees’ sociopsychological processes and outcomes in the context of workplace diversity, largely overlooking processes necessary for unskilled, underresourced employees as part of workplace diversity research (with the exceptions of Fujimoto et al., 2019; Janssens & Zanoni, 2008; van Eck et al., 2021). Similar to previous workplace inclusion research, COR research in employment contexts has been limited to a primary focus on the mainstream work context in the Global North settings—such as people experiencing psychological contract breaches, layoffs, job burnout, and depression in professional work—to discover employees’ recovery processes (see Hobföll et al., 2018). In the context of the Global South, low-wage workers experience “hunger, starvation and the survivability of their families” (Alamgir et al., 2021, p. 10) and are increasingly resource deprived within the global production network. Surprisingly, little is known about workplace inclusion in an underresourced context. We therefore theorize on and investigate workplace inclusion from a COR perspective in one of the most underresourced workplaces: Bangladeshi garment factories.

COR theory emphasizes the common response of a group of people to withstand their traumatic challenges as an inclusive transactional model of how they integrate various resources (i.e., economic, social, and personal resources) to build their self-resilience (Hobföll, 1998, 2001, 2011; Lyons et al., 1998). Previous resource-based research has examined traumatic circumstances that deprive people of their resource capacity, such as the Holocaust (Antonovsky, 1979); war trauma, terrorism, and military occupation (Hobföll et al., 2018); and refugee experience (Nashwan et al., 2019). Emerging from such contexts, COR theory explains the power of individual gains of centrally valued resources that build resilience for managing stress and overcoming traumatic conditions (Hobföll, 2001). In the context of our study, we argue that COR theory is particularly relevant to factory workers in the Global South for regaining their dignity and self-worth through the way they obtain and retain resources (cf. Bain, 2019). By adopting the COR perspective, we therefore explore in this study how managers may provide their workplace inclusion initiatives through the integration of resources to foster their greater workplace inclusion experience and well-being.

We conduct a quantitative study supplemented by a preliminary qualitative study showing the importance of fair employment practices (i.e., managerially initiated fair human resource management practices, such as fair pay, training, and grievance procedures) via integrative economic and personal resourcing mechanisms (cf. Alamgir & Banerjee, 2019).

By filling in substantial gaps in the COR and workplace inclusion literature relating to what and how resources are required to enhance the inclusion of significantly exploited workers at workplaces, we advance knowledge in three significant ways. First, we provide a much-needed empirical study of workplace inclusion among one of the most underresourced employee groups in the world who face traumatic conditions. COR perspectives enrich workplace diversity research by providing more nuances on how economic, social, and personal resources might act as the basis of an inclusion mechanism that reduces inequality by breaking the link between resource disadvantages and the categorical group—highly relevant for employees with significant resource deprivations (c.f., Tajfel & Turner, 1986). To the best of knowledge, our study is the first COR-based examination of inclusion that explores the centrality of resources as a key inclusion process and well-being outcome for those underresourced employees. In the context of misuse of economic power over operative workers within highly segmented and hierarchical work settings, we validate the significance of managerially initiated economic inclusion via fair employment practices (e.g., economic resources from fair pay, fair training investment, medical services) for fostering workers’ well-being. We did not find the positive effects of non-rank sensitive inclusion (as a social resource/psychological sense of community) on their well-being. This contradictory finding informs that social resources alone cannot foster their well-being, highlighting the different needs of underresourced employees compared to resourced employees. Second, we offer new knowledge on the integrative resource model of workplace inclusion by validating workers’ job-related LO as an internal condition for strengthening the positive effect of economic inclusion on life satisfaction, inferring the power of human agency to achieve “workable modus vivendi” in objective circumstances (Archer, 2003, p. 5). Additionally, our findings also showed that LO did not strengthen the relationship between managerial consideration and well-being via non-rank sensitive inclusion as a social resource. This finding informs scholars that personal resources such as LO can only act as a conditioning factor when workers in Global South such as Bangladesh are given adequate economic resources. Third, we extend research on the COR perspective of business ethics for the well-being of factory workers in the Global South by signifying a micro-level managerial intervention that provides economic resources via employment practices to address persistent exploitation (c.f. Bowie, 2017).

Next, we discuss the concepts of economic, social, and personal resources relevant to workplace inclusion before developing and presenting our conceptual model and associated hypotheses based on the extant literature and initial interviews.

Economic, Social, and Personal Resources for Workplace Inclusion

The COR theory of integrative resources for vulnerable populations has led us to develop an integrative resource model of inclusion and associated hypotheses. We have tied economic, social, and personal resources to workplace inclusion and well-being for factory workers in the Bangladeshi readymade garments sector.

Economic Resources for Inclusion

Factors such as economic stability, job security, and material accessibility are related to economic resources within the COR theory (Hobföll et al., 2018). Based on a socioeconomic approach to addressing economic deprivation, we define economic inclusion of vulnerable and underprivileged groups as access to the financial and material resources that can provide a greater sense of control and future prospects while cultivating a sense of belonging (Atkinson, 1998; Wagle, 2005). As such, economic inclusion promotes job security as a sign of inclusion, symbolizing the organizational acceptance of each employee as an insider in the work system (cf. Pelled et al., 1999). For instance, previous research highlights that in many cases, cost competitiveness and market volatility within the Bangladeshi readymade garments sector have transpired at the expense of inhumane economic work practices (Alamgir et al., 2021). Therefore, this necessitates greater economic inclusion among workers in such a context.

Social Resources for Inclusion

The social support and attachment practices that allow for healing through communal sharing are generally referred to as social resources (Hobföll, 2014). Relating social resources to social inclusion for workers of low socioeconomic status, we adopt Janssens and Zanoni’s (2008) concept of non-rank sensitive inclusion, as a manifestation of social resource, meaning relational inclusion for hierarchically segregated workers. This inclusion is distinctive from rank sensitive inclusion, which often means inviting employees to take part in joint organizational information and decision-making processes (Nishii, 2013; Shore et al., 2018). Furthermore, non-rank sensitive inclusion also helps engender psychological sense of community that emphasizes meeting the workers’ emotional and symbolic sense of belonging through mutually supportive relationships in a workplace (Sarason, 1974). In the midst of the life-threatening work context, non-rank sensitive inclusion supplements economic inclusion. For instance, as reported in Alamgir and colleagues’ recent study of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Bangladeshi factory work practices, workers were subject to managerial verbal and behavioral abuse, which points to the need for more attention to the managerial approach to address unfair work practices (Alamgir et al., 2021).

Personal Resources for Inclusion

Personal resources refer to the degree of personal orientation and key skills in life such as mastery, self-resilience, efficacy, optimism, and job skills (Hobföll et al., 2018). To exemplify the personal resource, during the COVID-19 crisis, while working in unhygienic workplaces, female workers individually negotiated the norms of protection from the virus by taking their initiatives to protect their lives (Alamgir et al., 2021), indicating their resilience for survival in light of their economic needs. COR theory (Hobföll, 1988, 1989, 1998) signifies those personal resources used by individuals to manage their stress (Hobföll, 2001). We envisage that workers will leverage the impact of economic and non-rank sensitive inclusion on employee well-being with resilience and mastery in important life tasks (Hobföll, 2012). Considering their ability to perform their job as an essential life skill for their survival, we regard the workers’ job-related learning orientation (LO) as a personal resource that leverages external resources to promote well-being (Elliot & Church, 1997).

Conceptual Model and Hypotheses Development

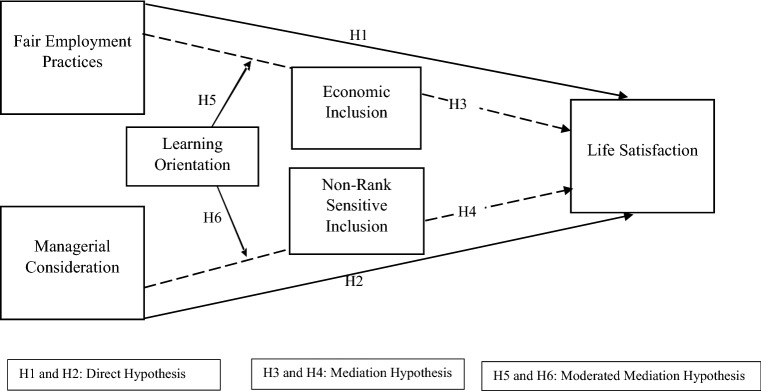

Being supplemented by our preliminary explorative interviews (method outlined later), this section provides our conceptual model and hypotheses development. Figure 1 shows our proposed conceptual model. We first develop our hypothesized direct relationships in relation to (1) fair employment practices and well-being and (2) managerial consideration and well-being. We then develop moderated mediation relationship hypotheses on how economic inclusion, non-rank sensitive (social) inclusion, and LO may offer more nuances to the direct relationships. Our conceptual model also corroborates a recent study conducted by Alamgir et al. (2021) in the same Global South work context, reporting the oppressive economic and social conditions that demand the resiliency of readymade garments factory workers in Bangladesh.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model

Fair Employment Practices and Well-Being

The previous research on employees of low socioeconomic status has stressed the unique ways to provide their sustainable employment (George et al., 2012; Silverthorne, 2007). In light of their deprived employment conditions, we hypothesize the centrality of fair employment practices that influence their well-being. From workplace inclusion literature, fair employment practices are referred to as managerially initiated fair human resource management practices, such as fair pay, fair promotion, and fair training investment, to ensure that resource distribution is unrelated to identity group membership and reduce the tendency of groups with more resources to command more power over groups with fewer resources (Nishii, 2013; Randel et al., 2018). Previous research on Bangladeshi factory workers has reported that employment practices such as immediate employment termination, the absence of medical insurance, and labor unions’ powerlessness have led workers with no sense of control to pursue respectable employment practices (Sharma, 2015). The Covid-19 crisis has exposed their potential death by hunger as a result of insecure employment practices such as delayed pay and unhygienic practices (Alamgir et al., 2021). Our initial interviews also corroborated those studies identifying employment practices mainly in fair pay, training investment, grievance procedures, and safety measures as vital sources of their life satisfaction. Therefore, we propose that job security of underresourced employees obtained through fair employment practices is central to protect their own and their families' livelihoods.

As part of diversity climate research, researchers have found that perceptions of fair employment practices are positively related to employees feeling senses of hope, optimism, and resilience (Newman et al., 2018), as well as to job satisfaction (Hicks‐Clarke & Iles, 2000; Madera et al., 2013), organizational commitment (Gonzalez & DeNisi, 2009; Hopkins et al., 2001), psychological empowerment, freedom of identity, and organizational identification (Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013). In this study, we examined the link between fair employment practices and life satisfaction. Life satisfaction is acknowledged as “a subjective global evaluation of whether one is content, satisfied and or happy about one’s life” referring to overall subjective well-being (Cheung & Lucas, 2015, p. 120; Schmitt et al., 2014). We regard life satisfaction as an appropriate well-being indicator for Bangladeshi garment workers, who often experience extreme adversities in their work and nonwork domains as a whole. Hence, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 1: Fair employment practices are positively and significantly related to Bangladeshi garment workers’ life satisfaction.

Managerial Consideration and Well-Being

The recent review of research on low-wage employees has reported the importance of managerial consideration to meet their specific needs to address their marginalized voices (van Eck et al. 2021). In the Covid-19 study, factory owners/managers showed indifference about their well-being while workers tolerated devasting work and employment practices to keep their job in order to survive (Alamgir et al., 2021). Based upon non-rank sensitive inclusion and previous studies, we adopted the managerial consideration from the concept of managerial individual consideration as a key component of transformational leadership (Avolio & Bass, 1995) and is defined as a leader’s ability to treat followers individually with care and concern, continually striving to meet their needs and to develop each individual’s full potential (Avolio et al., 1999; Bass, 1985). The inclusive leadership theories have defined inclusive leaders as inviting and appreciating others’ contributions (Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006), being open, accessible, and available (Carmeli et al., 2010, p. 250), fostering power sharing (Nishii & Mayer, 2009), and facilitating a sense of belonging and uniqueness in followers (Randel et al., 2018). We argue that leader’s consideration for each worker’s welfare may authenticate inclusiveness of a leader for the workers under significant exploitations in the work system. We suggest that managerial individual consideration provides nuance to the behavioral aspect of inclusive leadership and is particularly meaningful for significantly exploited employees to obtain their sense of self-worth within the hierarchically segregated work system. Our preliminary interview data also indicated a lack of managerial considerations for their overworked and stressful experience, such as managers not giving break; harsh words from supervisors for having small chats, rude supervisor behavior, threatening their job security. In light of inclusive leadership for the workers within the highly segmented and hierarchical work system, we proposed that managerial individual concerns such as giving personal attention and helpful behaviors might aid the workers to disavow their preconceived socioeconomic status and rank within the work system and view themselves as valued individuals, which, in turn, might increase their level of well-being. Hence, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 2: Managerial consideration is positively and significantly related to Bangladeshi garment workers’ life satisfaction.

We further contend that the degree of fairly implemented employment practices as a foundation for economic resources, managerial consideration as a foundation for social resources, and employees’ LO as a foundation for personal resources may contribute to their resource gain processes (Hobföll, 2012, p. 5; Parks-Yancy et al., 2007). We contend that employees need these resources to enhance their ability to manage and mitigate their trauma and stress levels (Gallo & Matthews, 2003; Gallo et al., 2005). Particularly in the context of significant resource loss, such as in the case of Bangladeshi factory workers, the COR theory and empirical results indicate that resource gain carries significant impact in the loss circumstances for individuals to manage their stress (Hobföll, 2002, 2012; Hobföll and Lilly, 1993). Past researchers have indicated that access to a broad range of resources is positively related to well-being (Diener et al., 1995; Diener & Fujita, 1995). Thus, we predicted that possession of economic, social, and personal resources would be an important determinant for workers’ well-being (c.f., Hobföll et al., 1990).

Fair employment Practices, Economic Inclusion, and Life Satisfaction

We envisage that fair employment practices in the areas of pay, grievance procedures, training investment, and career opportunities as avenues to foster a sense of economic inclusion among Bangladeshi garment workers. In light of the industry being notorious for its low wages and sudden layoffs of factory workers (Bain, 2019), employment practices may be used to enhance workers’ senses of economic security, independence, stability, and sufficiency (Grossman-Thompson, 2018; Kossek et al., 1997). Although low-income employees are often regarded as low-status and disposable labor with restricted employment opportunities (Collinson, 2003; Grossman-Thompson, 2018), a previous study reported that managerially initiated reforms of employment practices (e.g., offering above-minimum-wage jobs, adequate pay to cover basic necessities, child care support, housing subsidies, or job training) were identified as successful initiatives that fostered the economic security of the working poor (Kossek et al., 1997). The recent research has also verified the importance of material safety (e.g., payment security) as part of workplace inclusion initiatives for low-wage workers (van Eck et al. 2021). We contend that the perception of economic or material resource gain as a result of fair employment practices may produce a critical condition for workers to reverse their perceptions of status bias treatment and shape their perceptions of inclusion in the workplace. In our preliminary interviews, the workers (mostly female workers) have reported inadequate economic resources of lack of direct pay and indirect pay (e.g., lack of training investment, onsite medical support, maternity and child care facilities, and the inability of female workers to apply for promotion), demonstrating a potential overlap of perception of fair employment practices and economic inclusion.

Our qualitative insights also indicate the patriarchal society of Bangladesh that inherently places women in subordinate positions, warranting the female-related inclusive employment practices within the Bangladeshi context. Notably, economists and psychologists have found income and relative income to be key determinants of subjective well-being (Clark & Lelkes, 2005). Economic factors have also been significantly associated with life satisfaction, and those with higher incomes have reported more life satisfaction than those with lower incomes (Bellis et al., 2012; Cheung & Lucas, 2015; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Diener, 2000). Due to economic hardship, individuals of low socioeconomic status have consistently reported weaker psychological states (e.g., stress and depression) and poorer health than individuals of high socioeconomic status (Adler et al., 1994; Calixto & Anaya, 2014; Everson et al., 2002; Verhaeghe, 2014). Therefore, we tested the effect of fair employment practices on life satisfaction through economic inclusion. Accordingly, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 3: Bangladeshi garment workers’ sense of economic inclusion positively mediates the relationship between fair employment practices and their life satisfaction.

Managerial Consideration, Non-rank Sensitive Inlcusion, and Life Satisfaction

Managerial consideration reflects social support that affects individuals’ social interactions and provides actual assistance and a feeling of attachment to a person or group that is perceived as caring or loving (Hobföll & Stokes, 1988). Social support is the most recognized aspect of social resources for managing stress in the midst of extremely stressful circumstances (Palmieri et al., 2008; Schumm et al., 2006). It fosters a healthier social identity and lends a sense of being valued, which, in turn, promotes psychological well-being (Hobföll et al., 1990). Previous studies on the working poor reported that supervisors’ personally providing counseling and helping to meet those employees’ needs (e.g., addressing individual transportation and domestic violence problems) as key diversity initiatives that created strong social bonds within the workplace (Kossek et al., 1997). The past study also reported the managerial approach to addressing the individual needs of operative workers as being a key dimension of non-rank sensitive inclusion, breaking the norm of exploitation and simultaneously building symbolic and emotional connections among the workers (Holck, 2017; Janssens & Zanoni, 2008). The recent research has also verified the importance of non-task oriented involvement for building social relationships for greater inclusion of the low-wage workers in workplaces (van Eck et al. 2021). Thus, we predicted that managerial consideration as social resources for the workers would stir a non-rank sensitive inclusion, which would, in turn, enhance workers’ psychological well-being.

We elaborated on the concept of non-rank sensitive inclusion by adopting the concept of a psychological sense of community. It has been regarded as a feeling that members matter to one another and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together, and as a result, one does not experience sustained feelings of loneliness (Clark, 2002; McMillan & Chavis, 1986; Sarason, 1974). Therefore, a psychological sense of community (here non-rank sensitive inclusion) is a social resource that fills the members’ needs for belonging and personal relatedness in a group (Boyd & Nowell, 2014; Nowell & Boyd, 2010). This concept reflects widely shared definitions of inclusion that emphases on members’ insider status. The COR theory (Hobföll, 1989, 2001) suggests that social resources positively impact affective states in a group, such as creating reservoirs of empathy, efficacy, and respect among workers, which then foster collective well-being (Hobföll et al., 2018). Therefore, we predicted that a crossover of social resources from managers giving individual workers personal attention, help, and guidance would foster a psychological sense of community among the workers and foster well-being. For example, our initial interview and a more recent study in COVID-19 crisis reported on the significant need for managerial consideration on the workers’ overwhelmingly heavy burden conditions to foster the sense of close relationships at the workplace (Alamgir et al., 2021). As such, workers' non-rank sensitive inclusion (sense of community) has been found to enhance psychological well-being (Davidson & Cotter, 1991; Peterson et al., 2008; Pretty et al., 1996; Prezza & Pacilli, 2007). Hence, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 4: Bangladeshi garment workers’ non-rank sensitive inclusion positively mediates the relationship between managerial consideration and their life satisfaction.

Employee Learning Orientation

Workers of low socioeconomic status tend to lack certain characteristics, such as a can-do attitude and diligence (Shipler, 2005), and report lower perceived mastery and well-being as well as higher perceived constraints (Lachman & Weaver, 1998). We recognize that the lack of these personal characteristics is largely attributed to the significantly exploitative practices and mistreatment exhibited within the Bangladeshi garment factories. Yet we also acknowledge the employees’ capacity to establish a modus vivendi through their inner discourse between a given environment and their well-being (c.f. Archer, 2003). Along with psychological studies that challenge the Western-focused trauma treatment on post-stressful events (e.g., war), researchers have called for a more complex psychological model by considering the individuals’ varying mental conditions and the need for their stressful management capacities in amidst significant challenges (Attanayake et al., 2009; De Schryver et al., 2015). For example, our initial interviews have reported on the workers’ resilience to become financially independent and their desire to obtain more training and feedback to learn new skills and support themselves and their family members with extra earnings.

COR research conducted in other contexts (e.g., disaster) has reported that resource loss enhance individuals’ motivation to cope with the negative impact of a disruptive event (Freedy et al., 1992; Kaiser et al., 1996). Past COR related research also informs that personal orientation integrated with immediate negative (and positive) events can affect the extent of life satisfaction (Suh et al., 1996). Similarly, we argue that employees’ having higher job-related LO levels should strengthen (i.e., moderate) the resourcing effects of inclusion on well-being (Hobföll, 2012) by leveraging on those resources to enhance their life satisfaction. As such, we theorize that employees will gain varying perceptions of economic inclusion depending on their perceptions of fair employment practices for each employee, as well as on their degrees of LO, which influences their well-being. Notably, most of our interview participants also perceived regular income to be highly valuable for developing their lives. Thus, this further highlights that Bangladeshi workers with a higher degree of job-related LO would interact positively with perceived fair employment practices leading to increased well-being via their economic inclusion. As such, we propose:

Hypothesis 5: LO moderates the positive effects of fair employment practices on life satisfaction through economic inclusion in such a way that this mediated relationship is stronger for Bangladeshi garment workers with higher LO levels.

Furthermore, based on the COR theory, we contend that those with high LO levels would capitalize on managerial consideration to strengthen their learning and show a greater ability to cope with stressful situations than those with low LO levels (c.f., Hobföll et al., 1990). Furthermore, an employee’s LO has been reported to influence social interactions with a mentor in such a way that having an LO level similar to that of a mentor tends to obtain the highest levels of psychosocial support from the mentor (Godshalk & Sosik, 2003; Liu et al., 2013). Past research also indicates that due to their underresourced condition, workers with low socioeconomic status tend to show more relationship-dependent and other-oriented behaviors than those with high socioeconomic status, who tend to display more social disengagement and independence (Kraus & Kelner, 2009; Kraus et al., 2009). Our interview participants also echoed their desire to learn new skills from their supervisors and co-workers if this was supported by management.

Hence, we theorized that Bangladeshi garment workers with high LO levels would not only be more receptive to managerial consideration but also regard other workers as valuable social resources for them to manage their stress. Thus, we predict that by getting personal managerial care and concern, workers from Global South with high LO levels would reinforce their relationship-dependent and other-oriented behaviors within a factory, thus promoting their non-rank sensitive inclusion, per se, psychological senses of community and well-being. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 6: LO moderates the positive effects of managerial considerations on life satisfaction through a non-rank sensitive inclusion (psychological sense of community) in such a way that this mediated relationship is stronger for Bangladeshi garment workers with higher LO levels.

As outlined earlier, we assess our integrative resource model and its associated hypotheses in the context of Bangladeshi garment workers representing the Global South. Thus, before embarking on our preliminary qualitative and main quantitative study, we provide the context of Bangladeshi garment workers’ well-being.

The Context of Bangladeshi Garment Workers’ Well-Being

Bangladesh is the second largest RMG-exporting country after China (Asian Center for Development, 2020). Over the 2020–21 fiscal year, the RMG sector accounted for 81.16% of the country’s exports. The RMG industry is the second largest employer in Bangladesh, employing over 4 million people, with the highest number of women among industries in Bangladesh (Asian Center for Development, 2020; BGMEA, 2021; International Labour Organization [ILO], 2020). The gender composition of RMG workers is 60.5% women and 39.5% men (ILO, 2020). However, the ratio of women in leadership was reported to be below 10% for supervisors and only around 4% for managers in the RMG industry (ILO, 2019). At the institutional level, Bangladeshi apparel workers’ well-being ought to be governed by the country’s constitution1 and the Bangladesh Labour Act of 2006. The Act has been amended multiple times with the ILO toward meeting international labor standards (). The amendments to the Bangladesh Labour Act of 2006 took place in 2013 and 2018 and involved workers’ rights, freedom of association to form trade unions, and occupational health and safety conditions (ILO, 2016; Sattar, 2018). After the tragic collapse of the Rana Plaza building in 2013, the Bangladeshi government, the Employers Federation, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), the Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturing and Exporting Association (BKMEA), the National Coordinating Committee for Workers’ Education, and the Industrial Bangladesh Council (representing unions) signed the National Tripartite Plan of Action (NTPA) to make necessary reforms on fire safety and structural integrity in the garment sector. Although major buyers, retailers, and key fashion brands were not signatories of the agreement, some MNCs formed the Accord and Alliance—the two competing MNC governance initiatives—to improve workplace safety in Bangladesh, especially for the RMG industry (As-Saber, 2014).

Despite considerable institutional enforcements and the MNCs’ initiatives over the years (Berg et al., 2021), the European Union has reported MNCs’ significant shortcomings in respecting labor rights and asked the Bangladeshi government to further amend the Labour Act to address forced labor, minimum wage requirement, and violence against workers (Haque, 2020). Recent studies on the sector have also confirmed the misrepresentation of a compliance framework that assures MNCs and local authorities’ legitimacy and gives the impression that management has made changes to workers’ conditions (Alamgir & Alakavuklar, 2018; Alamgir & Banerjee, 2019; Alamgir et al., 2021). Bangladeshi RMG workers’ wages are still among the lowest in the world (Barrnett, 2019). In the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, their “live or be left to die” employment conditions disclosed inhumane employment practices (e.g., unpaid and unstable wage; unhygienic practices) that confirmed the superficial compliance arrangements (Alamgir et al., 2021). The harsh conditions have led to deaths and several injuries as a result of garment workers’ protests calling for pay and revised minimum pay (Connell, 2021; Uddin et al., 2020). Moreover, female factory workers, who make up the majority of the garment workforce, still work in repressive environments, where they are exploited by their managers and supervisors, have no freedom or opportunities for promotion at work (Islam et al., 2018), and experience economic, verbal, physical, and sexual violence (Naved et al., 2018) to survive within the gendered global production network (Alamgir et al., 2021). To the best of our knowledge, although the macro-level initiatives of multiple actors have been the central focus in order to improve their working conditions, little attention has been paid to micro-level workplace inclusion from resourcing perspectives that directly affect their well-being.

To date, several studies have highlighted macro-level interventions related to including factory workers in the Global South from various ethical viewpoints. Notably, Kantian ethics have been applied to MNCs to promote global practices that uphold workers’ rights (e.g., Arnold & Bowie, 2003) and the government’s responsibility to collaborate with employers to provide an acceptable minimum wage/living wage to workers (Brennan, 2019). Altruistic utilitarian ethics have been applied to relational corporate social responsibility to promote workers’ economic and social development (Renouard, 2011). New governance perspectives have been applied to laws (Rahim, 2017), sweatshop regulation (Flanigan, 2018), and various actors to promote bottom-up interdependent approaches, address inactive, ineffective, or inequitable governance mechanisms, and improve working conditions (Niforou, 2015; Schrage & Gilbert, 2019). Alamgir et al. (2021) called for more granular investigation of the causes of failure, from how workers perceive their work practices to improve their economic and social well-being. We extend this research route via micro-level exploration of workplace inclusion mechanisms for factory workers from the COR perspective.

Method

To build a rich understanding of our focal COR constructs in the context of Global South workplace inclusion and inform our main quantitative study, we conducted preliminary interviews with 23 Bangladeshi garment workers. The interview has given us the intuition to corroborate our model development and construct our measurement items in light of existing literature and the Global South context. The subsection that follows discusses the research approach undertaken for conducting these preliminary interviews and their integration into our conceptual model and hypotheses development.

Preliminary Interview Approach

Upon receiving ethical clearance, with the assistance of a local nonprofit organization specializing in garment workers in Bangladesh, the research team sought approval from a range of RMG factories to interview their workers. Nine factories provided us the permission to approach and interview those workers who voluntarily agreed to participate in our study.

This process resulted in one of the research team members to conduct interviews of 23 garment workers in the local Bengali language. The interviews were translated into English by another Bangladeshi researcher in Australia. As shown in Table 1, nineteen of our participants were female workers, and the remaining four were males. All participants had completed primary schooling, and some had received secondary school certificates. All participants had worked for at least 2 years and had similar salaries, and they worked across a range of small to large (well-established) RMG factories in Bangladesh.

Table 1.

Composition of participants

| No | Participant pseudonym (gender) | Education level (minimum) | Minimum experience (in years) | Factory code and size | Factory location and area cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Akhlima (F) | Primary | 3 | Factory 1 (medium) | Narayanganj |

| P2 | Rahima (F) | Primary | 6 | Factory 2 (large) | Ashulia |

| P3 | Alam (M) | Secondary | 5 | Factory 8 (medium) | Ashulia |

| P4 | Shomela (F) | Primary | 2 | Factory 3 (small) | Chittagong |

| P5 | Halima (F) | Primary | 4 | Factory 4 (large) | Ashulia |

| P6 | Fara (F) | Secondary | 7 | Factory 5 (large) | Ashulia |

| P7 | Nurjahan (F) | Primary | 4 | Factory 6 (large) | Narayangong |

| P8 | Tasnim (F) | Primary | 5 | Factory 2 (large) | Ashulia |

| P9 | Lipi (F) | Primary | 6 | Factory 6 (large) | Narayangong |

| P10 | Doli (F) | Primary | 3 | Factory 7 (small) | Ashulia |

| P11 | Monju (M) | Secondary | 4 | Factory 2 (large) | Ashulia |

| P12 | Khatun (F) | Primary | 4 | Factory 3 (small) | Chittagong |

| P13 | Rahim (M) | Secondary | 3 | Factory 8 (medium) | Ashulia |

| P14 | Shumi (F) | Primary | 4 | Factory 1 (medium) | Narayanganj |

| P15 | Sharmin (F) | Primary | 3 | Factory 7 (small) | Ashulia |

| P16 | Romela (F) | Secondary | 3 | Factory 1 (medium) | Narayanganj |

| P17 | Azmat (F) | Secondary | 7 | Factory 6 (large) | Narayangong |

| P18 | Fatima (F) | Primary | 5 | Factory 9 (medium) | Chittagong |

| P19 | Shorifa (F) | Primary | 2 | Factory 5 (large) | Ashulia |

| P20 | Happy (F) | Primary | 2 | Factory 3 (small) | Chittagong |

| P21 | Ripon (M) | Secondary | 5 | Factory 8 (medium) | Ashulia |

| P22 | Jahanara (F) | Primary | 6 | Factory 9 (medium) | Chittagong |

| P23 | Selim (S) | Primary | 3 | Factory 7 (small) | Ashulia |

F female, M male

We asked our interview participants broad questions, such as What have you received from this factory that made you feel valued? What makes an inclusive workplace? What causes you the most stress in your employment? What sort of practices influence your life satisfaction? Interviews lasted for 20–30 min and were audio-recorded (with permission) and transcribed.

We have analyzed our data in light of an inclusive workplace and what causes employees to feel stress in their employment. We agreed that workers reported their sense of resource deprivation by how managers treated them. The participants described an inclusive workplace regarding fair employment practices, such as managerial treatment with equal respect for work safety, better pay, job security, voices being heard, and transparent policies and the work relationships such as an “integral part of [the] workplace” and “a team member of the factory.” In our interviews, we did not initially adopt COR resource perspectives of economic, social, and personal dimensions. After discussing key patterns in data, we connected the informants’ inclusion references with the COR perspective to categorize how workplaces have fostered various resources and well-being. Since inclusion highly connotes resource accessibility, it also made sense for us to use the COR perspective to articulate how different resources promoted workplace inclusion.

We identified economic, social, and personal resources as common resources that created an inclusive factory. In relation to economic resources, some participants reported on the fairness of employment practices with economic inferences, saying, “If someone is working late, s/he is just a hard worker,” whereas other participants reported receiving “wages every month while working in different RMG factories. I could work overtime and earn extra money for each additional hour. I am happy, and, above all, I am respected in my neighborhood.” Some participants highlighted social resources in the form of managerial consideration for their job-related development by receiving clear job instructions and attaining permission to attend outside training or a lack of concern in the areas of training instruction, continuous pressure to meet shipment deadlines, and verbal insults. We identified job-related LO as their desire to learn more skills from supervisors and attend skills training in and outside their factories despite a lack of support. For example, one worker mentioned, “I have not attended any training yet. However, I certainly want to develop required skill[s] if I am given any opportunity in [the] near future.” Notably, these initial findings partly align with a recent study in a similar context that reported the exploitative economic and social practices that called for managerial urgency to address their poor work conditions (Alamgir et al., 2021).

Table 2 includes sample quotes related to economic, social, and personal resources with reference to employment practices and managerial consideration at the workplace. The emphasis on economic resources (via employment practices), social resources (via managerial consideration), and personal resources (via LO) formed our basis for a quantitative study on inclusion processes as to how those resources were interconnected with the workplace inclusion research domains. Our qualitative data also contributed to economic inclusion and managerial consideration’s measurement items for our main study; we specify this later in our measures subsection.

Table 2.

Sample quotes representing economic, social, and personal resources related to workplace inclusion and well-being

| Resource constructs and relationships | Sample quotes |

|---|---|

| Economic resources (economic inclusion) and well-being via employment practices | The work at the RMG factories is very tiring and creates fatigue. Compared to work pressure, the salary and other non-financial benefits are not enough. The tiring work and not so friendly workplace have been a matter of concern for me and my co-workers for a long time now. However, I must admit that I have managed to help myself and my family with the earnings from working in this industry |

| Jobs in factories are not truly permanent. There are times when the factory has limited orders from buyers or buyers are not paying the factory management on time, we face difficult times. During such times, I am always worried about losing my job. I have seen many colleagues losing their job during such times. So there is no job security here and I am always worried about losing my job. After all, my family depends on this income | |

| I think fairness and fair pay is a critical aspect. Fair employment practices and compensation, treatment of employees, ensuring employees are given flexibility at work and opportunities to learn are essential not only for job satisfaction but also for overall life satisfaction. There are even times when I had not received my salary for two months consecutively as buyers were not paying the factory timely | |

| I think organizations that have better HR and wellbeing rules and regulations have a positive impact on their employees. The factory must have a robust procedure for grievances and a work culture that treats workers fairly in terms of compensation and benefits | |

| Social resources (non-rank sensitive inclusion) and well-being via managerial consideration/supportive practices | Support from the factory is also important for me. Suppose any worker needs some money on an urgent basis or in distress. In such case, we will be able to talk to the supervisors and management team for some advance payment or other related support to overcome distress. However, when I find that my work pressure is getting too much, I try to talk to my supervisors for workload adjustment. They hardly adjust that so I make a sick leave (sick call) for one or two days |

| We are always under continuous pressure to meet buyers’ specifications and management’s guidelines. With that, when management’s anxiousness passes down us, we become more stressed. Forget about flexibility or spare time between work; sometimes, we cannot even go for the lunch break due to work pressure. Working continuously for long hours without any break is tiring. And, it causes a lot of physical and mental stress for me | |

| Giving the employees to raise their voice on the issues they are facing is very important. Also, the management needs to have an open mind to listen to and take action on the complaints made by the employees. Ensuring a work culture where employees are not afraid of sharing their views and concerns is also very important. Sometimes, I feel like not sharing my problems with anyone at work because I am afraid of how the supervisors will take this | |

| My supervisors or HR department do not take any step in supporting me to cope with the work stress | |

| Personal resources and well-being via learning orientation in light of economic and socially deprived context | Behavior of some of the supervisors was very rough. They neither supported me inside the factory to learn nor spared me for one or two days to learn those skills outside the factory. Even when there were some opportunities for training within and outside the organization, my supervisors did not allow me to attend the training sessions during my regular working hours |

| RMG is a big industry and there are many firms where policies are better and transparent. Hence, I believe if I can learn and develop my skills properly, there are ample opportunities. The work pressure is intense, and many times, I was mistreated by my superiors. There are even times when I had not received my salary for two months consecutively as buyers were not paying the factory timely. However, although the work has been stressful, I have managed to make myself financially independent and help my family from the earnings of this job | |

| Most importantly, I am not dependent on my husband. I take care of all the financial needs of my children. Moreover, over these years, I have managed to save some amount of money for the future as well. I have struggled a lot to reach where I am now financially but when I think about how I have managed to come so far especially being a woman, I feel good |

Quantitative Data and Sample

The Bangladeshi garment workforce comprises 4 million (estimated) workers across 4379 garment factories in Bangladesh (Bangladesh Garment Manufacturer & Exporters Association, 2020; International Labour Organization, 2020). As discussed previously, the majority of workers in the Bangladeshi garment sector are at the lower ends of their operational and organizational hierarchies, thus making this group particularly relevant to the aim of this study. Prior to administering our actual surveys, we reverted back to our initial interview participants and showed them our survey and sought for their feedback on the measures including its content validity. This led to minor changes in the wording of some survey items.

As part of this study's inclusion criteria that fitted to our research objectives, we sought for factories that have been in operation for more than 10 years in Bangladesh and have exported their entire production overseas. The same local nonprofit organization who assisted us with recruitment of interview participants provided us with a list of 50 similar types of large-scale, export-oriented garment manufactures in Bangladesh that fitted with our inclusion criteria. Using IBM SPSS complex sample function, we generated a refined list of 25 randomly selected garment manufactures to mitigate any potential bias that could arise due to sample selectivity (IBM Corp, 2017). Of the 25 factories approached 18 agreed to participate in this study. The participating factories also reported to the research team that they have had to comply with various human resource and production rules to meet local and international exporting standards.

The unit of analysis of this study was garment workers at the lower ends of their operational and organizational hierarchies (i.e., employees of low socioeconomic status) who are vulnerable and least likely to have access to or control of valuable resources and employment practices (Berger et al., 1972; DiTomaso et al., 2007; Earley, 1999). Mid-level line managers/supervisors of the participating factories assisted the research team to communicate (announce) about the voluntary two-wave survey participation to their lower-end factory workers. Next, the research team including the factory management informed the respondents that their responses would be kept anonymous with absolutely no implications on their employment and that non-participation would have no adverse consequences on their employment.

As a best practice, to minimize common method variance biases, we carried out the surveys in two waves (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The second survey distribution (T2) was therefore conducted a month after the first time point (T1). The first survey distribution (T1) comprised of our independent, control and moderating variables and the second survey (T2) comprised of our mediating and outcome variables. Given the sort space of time between the two waves of the survey only five participants dropped out between the survey periods. As such, our data collection resulted in valid responses from 220 lower-end garment factory workers across 18 participating factories. Trained researchers conducted the surveys using traditional pen and paper in the local Bengali language. Both sets of surveys (T1 and T2) were translated by a Bangladeshi researcher in Bangladesh and then translated back by another Bangladeshi researcher working in Australia.

The sample was comprised 75% of female and 25% of male garment workers, with 41% of respondents below the age of 25, 40% between 26 and 34, 13% between 35 and 44, and the remaining 6% over 45 years. Of the participants, 58% had completed Year 5 schooling, 28% Year 10 schooling, and 14% Year 12 schooling, and 1% had a diploma degree. In terms of work experience, 25% of the respondents had less than 1 year, 35% had between 1 and 2 years, 21% had between 3 and 4 years, and the remaining 19% had 5 years or more. A plurality of the respondents (i.e., 47%) had a monthly income between 5000 and 8000 BDT,2 and this figure ranged between 8001 and 11,000 BDT for 33%, between 11,001 and 14,000 BDT for 15%, and above 14,000 BDT for the remaining 5%.

Measures

Table 3 shows the items used in this study and their associated squared multiple correlations values. Average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability values for our study constructs are presented in Table 4. All items representing this study’s key constructs were measured by using a 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree” Likert-type scale. Scales used for measuring the variables in our study are highlighted below:

Table 3.

Construct measures

| SMC | |

|---|---|

| Fair employment practices | |

| Employees in this [unit] receive “equal pay for equal work.” | 0.63 |

| This [unit] provides safe ways for employees to voice their grievances | 0.64 |

| This [unit] invests in the development of all of its employees | 0.67 |

| This [unit] has a fair promotion process | 0.33 |

| The performance review process is fair in this [unit] | 0.41 |

| Managerial (Individual) consideration | |

| Gives personal attention to members who seem neglected | 0.69 |

| Find out what I want and tries to help me get it | 0.68 |

| Treats each subordinate individually | 0.56 |

| Make me feel we can reach our goals without him/her if we have to | 0.665 |

| I can share my personal thoughts/suggestions | 0.68 |

| Provides clear and timely guidance for my work | 0.69 |

| Learning orientation | |

| I want to learn as much as possible from this job | 0.66 |

| It is importance for me to understand the content of this job as thoroughly as possible | 0.73 |

| I hope to have gained broader and deeper knowledge of this job | 0.61 |

| I desire to completely master my job | 0.54 |

| I prefer tasks that arouses my curiosity even if it is difficult for me to learn | 0.52 |

| I prefer tasks that really challenges me so I can learn new things | 0.48 |

| Non-rank sensitive inclusion (psychological sense of community) | |

| When a co-worker is gone, [his or her] presence (not just the work [he or she] does) is dearly missed | 0.52 |

| The general feeling around work is that close relationships with others are the best part of work life | 0.55 |

| I confide my most personal matters with the people at work | 0.48 |

| My relationships at work are very close, perhaps even intimate | 0.64 |

| I am very fond of the people at work | 0.44 |

| Economic inclusion | |

| I have achieved economic independence | 0.92 |

| I have obtained sufficient income for my living from this job | 0.93 |

| I have obtained sufficient income to support my family | 0.89 |

| I have a stable income by commission or monthly earning | 0.88 |

| Life satisfaction | |

| In most ways my life is close to my ideal | 0.71 |

| The conditions of my life are excellent | 0.85 |

| I am satisfied with my life | 0.82 |

| So far I have gotten the important things I want in life | 0.77 |

| If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing | 0.65 |

| I am satisfied with my job | 0.50 |

SFL squared multiple correlations

Table 4.

Correlations and construct validity

| Constructs | CR | AVE | FEP | MC | LS | EI | NRSI | LO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEP | 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.72 | |||||

| MC | 0.91 | 0.64 | 0.47** | 0.80 | ||||

| LS | 0.93 | 0.69 | 0.39** | 0.46** | 0.83 | |||

| EI | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.44** | 0.45** | 0.53** | 0.93 | ||

| NRSI | 0.82 | 0.50 | 0.38** | 0.40** | 0.24** | 0.22** | 0.69 | |

| LO | 0.89 | 0.58 | 0.02 | -0.03 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.76 |

The number in the diagonal (in bold) = the square root of AVE. All correlations presented in the table are common method variance (CMV) bias adjusted

AVE average variance extracted, CR composite reliability, FEP fair employment practices, MC managerial consideration, LS life satisfaction, EI economic inclusion, NRSI non-rank sensitive inclusion, LO learning orientation

Independent variables (measured in T1): Five-item fair employment practices were adopted from Nishii’s (2013) climate-for-inclusion items. The managerial individual consideration measure comprised four items adopted from Bass’s (1985) study. Furthermore, as part of testing the face validity of the managerial consideration scale in the context of underresourced employees, we conducted exploratory interviews with 23 garment workers in Bangladesh in relation to what they valued as inclusive managerial behavior at work. Based on the feedback received from these interviews, we included two additional items—“I can share my personal thoughts/suggestions” and “Provides clear and timely guidance for my work”—that holistically captured our individual managerial consideration construct.

When we ran a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the six items of the managerial individual consideration scale showed acceptable composite reliability (0.91) and AVE values (0.51; see Table 2). Additionally, the content validity of these items was established by interviewing seven more garment factory workers (five female and two male) and several professional individuals in Bangladesh (e.g., two human resources employees, one industrial relations academic, one industry consultant, and one professional with industry experience in the Bangladesh garment sector). All participants regarded the six items representing the managerial consideration measure in our study as satisfactory. A CFA of the managerial consideration scale was also conducted, which indicated a good model (IFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, and RMSEA = 0.05; pclose = 0.31). This confirmed the unidimensionality of the six-item managerial consideration scale (Hair et al., 2010).

Moderator variable (measured in T1): Employee LO was measured through six items adopted from Elliot and Church’s (1997) study.

Mediating variables (measured in T2): Clark (2002) developed a scale for psychological sense of community based upon conventional definitions of community developed by Glynn (1981), McMillan and Chavis (1986), and Chavis and Wandersman (1990). We adopted Clark’s five-item scale as a measure of non-rank sensitive inclusion. Based upon the exploratory interviews with 23 garment factory workers in Bangladesh in relation to what they valued as inclusive at work, we developed a four-item economic inclusion scale relating to economic independency, sufficiency and regularity for their own and family’s livelihood. Additionally, we established the content validity of these items by interviewing seven more garment factory workers (five female and two male) and five professional individuals in the Bangladeshi garments industry (i.e., two human resources employees, one industrial relations academic, one industry consultant, and one professional with industry experience in the Bangladesh garment sector).

Outcome variable (measured in T2): We used Diener’s et al. (1985) five-item life satisfaction scale to measure life satisfaction in T2. Based on the feedback from interviews with sample garment factory workers, we also included one item of job satisfaction in the survey to measure the important work aspect of life satisfaction among Bangladeshi garment workers.

Control variables (measured in T1): We included age, gender, income, job experience, and education of respondents as control variables in our proposed conceptual model, as former study authors suggested that a range of sociodemographic factors can affect low-income workers’ perceptions of their organizations and employee inclusiveness (Habib, 2014).

Results

Reliability and Validity

As shown in Table 4, all constructs showed acceptable internal consistency (i.e., ≥ 0.7; Hair et al., 2010). We conducted a multifactor CFA using version 25 of the IBM AMOS software. The multifactor CFA helped us to generate values such as AVE and composite reliability (i.e., internal reliability). Using Fornell and Lfarcker’s (1981) technique, we tested discriminant validity by comparing the square roots of the values with the interconstruct correlations (as shown in Table 3). The square roots of the AVE values for each construct were greater than the interconstruct correlations, thereby demonstrating discriminant validity (see Table 3; Hair et al., 2010). Further, all values of AVE were greater than 0.5, showing convergent validity (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012).

Controlling for Common Method Bias

We followed best practices to reduce common method variance (CMV) bias by ensuring respondent anonymity, informing respondents that there were no right or wrong answers to prevent evaluation hesitation, and conducting our surveys at two different time points—T1 and T2 (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, given that we used single-source and cross-sectional data, CMV bias was still a possibility in our study. Thus, to test if CMV could affect our structural equation modeling (SEM) path estimates, we added a common latent factor to the multifactor CFA model and compared the standardized regression weights before and after the addition of the CLF (Gaskin, 2013). Some of these weights differed by greater than 0.2 (i.e., for all five items), which suggested that CMV might be an issue in our data set. To minimize and control for CMV bias, we included the common latent factor measure while estimating our hypothesized relationships. All hypotheses’ testing results were thus adjusted for CMV factors, providing more accurate path estimates (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Path Results

We ran SEM to estimate the direct and mediated path effects. The statistics of our SEM were good fits to our data set (IFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, CFI = 0.95, and RMSEA = 0.05; pclose = 0.22; Hair et al., 2010). In addition, the ratio of the chi-square value to its degree of freedom fit statistic (Hair et al., 2010; Holmes-Smith et al., 2006) was acceptable at 1.6, which was below the cutoff of 3.00 (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012). Additionally, we ran a power test of our model that showed a value of 1, which suggested that a sample size of 220 was adequate to test our hypothesized relationships (MacCallum et al., 1996).

Direct and Mediated Path Effects

We applied the bootstrapping (N = 2000) method using 95% bias-corrected confidence interval procedures in SEM with AMOS 25 to estimate the direct and mediated hypothesized paths within our proposed model. Given that this procedure involves resampling the data multiple times to estimate the entire sampling distribution of the path effect, it provides results with stronger accuracy of confidence intervals (Zhao et al., 2010). As a robustness check of our path results from SEM, we also used Hayes’s Process version 3 with IBM SPSS 25 to check if the direction and path estimates were similar (Hayes et al., 2017). The process analyses showed, as expected, a slight variation in the path estimates from the SEM path results. Nonetheless, all directions and the significance of the path effects remained the same.

In Hypothesis 1, we stated that fair employment practices significantly and positively relate to employee life satisfaction. As shown in Table 5, the direct path effect (b = 0.06, p > 0.05) of fair employment practices on employee life satisfaction was not significant, and we thereby reject our first hypothesis. In Hypothesis 2, we posited that managerial consideration significantly and positively relates to employee life satisfaction. As represented in Table 5, the direct path effect showed insignificant results (b = 0.07, p > 0.05), so we reject our second hypothesis.

Table 5.

Mediated and moderated mediation path estimates (bootstrap bias-corrected method 95% CI)

| Paths estimates | Estimates (b)a | SE | Lower | Upper | p value | Support for hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||||

| Fair employment practices—> life satisfaction | 0.06 | 0.10 | − 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.56 | H1: Not Supported |

| Managerial consideration- > life satisfaction | 0.07 | 0.12 | − 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.84 | H2: Not Supported |

| Mediated effects | ||||||

| Fair employment practices—> economic inclusion > life satisfaction | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.00 | H3: Supported |

| Managerial consideration- > non-rank sensitive inclusion—> life satisfaction | 0.01 | 0.04 | − 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.72 | H4: Not Supported |

| Moderated mediation effects via economic inclusion (mediator) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediated effectsa,b | SE | LLCI | ULCI | Support for hypothesis | |

| Fair employment practices (X) × learning orientation (LO) (W) | 0.48 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.83 | H5: Supported |

| Life Satisfaction (Y) | |||||

| Low LO (− 1 SD) | 0.03 | 0.03 | − 0.03 | 0.11 | |

| Moderate LO (M) | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.14 | |

| High LO (+ 1SD) | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.22 | |

| Index of Moderated Mediation | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.23 | |

| Moderated mediated effects via non-rank sensitive inclusion (med) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Managerial consideration (X) × learning orientation (LO) (W) | 0.05 (ns) | 0.06 | − 0.05 | 0.17 | H6: Not supported |

| Life satisfaction (Y) | |||||

| Low LO (− 1 SD) | 0.02 | 0.03 | − 0.03 | 0.10 | |

| Moderate LO (M) | 0.03 | 0.04 | − 0.04 | 0.11 | |

| High LO (+ 1 SD) | 0.04 | 0.04 | − 0.04 | 0.12 | |

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.01 | 0.02 | − 0.02 | 0.05 |

X predictor, W moderator, Med mediator, Y outcome variable, ns non-significant

* < 0.05

aCommon method variance (CMV) bias adjusted estimates

bUnstandardized estimates

In Hypothesis 3, we stated that economic inclusion would positively mediate the relationship between fair employment practices and life satisfaction (inclusive of job satisfaction). As shown in Table 5, the mediated path estimates (b = 0.11, p < 0.01) of fair employment practices on life satisfaction through economic inclusion were positively significant, therefore supporting our third hypothesis. Specifically, we identified fair employment practices as conduits to economic inclusion, which fostered their well-being. Contradicting previous research findings, we found no direct effects of fair employment practices on employee attitudes. Instead, employee perceptions of economic inclusion in the implementation of fair employment practices were necessary to foster their well-being. Our qualitative data have provided granular understanding of this finding as the workers mostly reported economic inferred unfair employment practices especially in the area of insufficient medical services, training investment, safety measures and child care facilities and overtime pay (see Table 1). For example, these are representative quotes from the workers:

One critical practice Sthat would be beneficial to workers is the provision of a healthy and safe workplace. This can be achieved by having an onsite doctor or medical facility or by providing medical insurance for the workers. Most of the workers are female and a good number of them are working mothers. Factories should implement practices that support working mothers such as providing maternity and childcare facilities (Female, 4 years in the factory, USD100–150 per month)

The factory’s expectation is that employees will be able to cope with changes in requirements and learn new design requirements by themselves. If there are any changes in machinery requirements, the organization arranges training for only a few people and for a short time. We have to learn to observe and learn from those few people (Male, 4 years in the factory, USD100–150 per month)

In Hypothesis 4, we posited that social resource (non-rank sensitive inclusion) allocation would positively mediate the relationship between managerial consideration and life satisfaction. Our mediated path effect proved to be insignificant (b = 0.01, p > 0.05), so we thereby reject our fourth hypothesis. Our findings that did not support the positive attitudinal effects of managerial consideration through non-rank sensitive inclusion contradicted the inclusion study in the past, which assumed that managerial initiatives that meet an individual’s social needs for belonging and uniqueness should result in positive attitudinal outcomes. We assumed that this sociopsychological process and outcome should apply to underresourced factory workers in non-rank sensitive ways. But, this was not the case. Notably, managerial consideration was also highlighted by several participants through perceived disrespect, inadequate job training and indifferent attitudes to employees’ grievances and stressful work conditions rather than their consideration for creating a sense of emotional bonds and meeting individual needs. In other words, rank sensitive inclusion of joint decision-making process with managers was more implied as what the workers’ needs from the qualitative data, inferring the importance of managers to include the workers in making decisions on employment practices, particularly in relation to provision of direct or indirect economic resources. Table 1 offers some qualitative data that give credence to the workers’ emphasis on managerial consideration in relation to employment practices such as how mangers consider their perspectives on advance payment, grievance procedures, working hours and support to deal with their work stress.

Moderated Mediation Effects

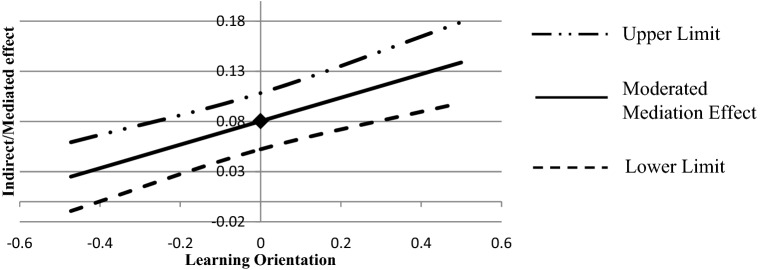

To test for moderated mediation (i.e., boundary condition effect), we used IBM SPSS Process version 3, as AMOS 25 has limitations in terms of calculating the index of moderated mediation values (Hayes, 2013). This statistical software package not only enables assessment of moderation but can also test for moderated mediation effect (Hayes, 2013). As shown in Table 5, the interaction between fair employment practices and LO on economic inclusion is positive and significant (b = 0.48, p < 0.05), therefore demonstrating the moderating effect of LO. As shown in Table 4, zero did not fall between the upper and lower confidence interval limits for the index of moderated mediation value (0.10), which provided support for our fifth hypothesis. Given this support, we probed this moderated mediated relationship further between low (− 1 SD) and high (+ 1 SD) values (see Table 5 and Fig. 2), which revealed that for employees with higher levels of LO, the positive mediated effect of fair employment practices on life satisfaction through economic inclusion was stronger. Some of our qualitative findings also provided support for this finding (see Table 3). The participants demonstrated their willingness to learn and develop their skills; and resilience to manage their lives particularly in economic areas, despite of enormous work pressures and lack of managerial support for their upskilling. For example, our qualitative data have reported on the workers’ resilience to become financially independent and their desire to learn new skills despite insufficient training and lack of living wages:

Although I received training initially, it proved to be insufficient. I only received verbal instructions without any practical demonstration. It was difficult for me to start working. Also, when I began to learn my work on my own, I thought of receiving some support from the factory. However, I sadly did not even get any proper feedback (Female, 4 years in the factory, USD100–150 per month)

Fig. 2.

Probing moderated mediated effect for learning orientation via economic inclusion

The following quotation demonstrates her resilience to cope with life circumstances via job-related LO by her own initiative to find employment to look after her family members:

However, I must admit that I have managed to help myself and my family with the earnings from working in this industry. I was a housewife before starting work in the RMG industry, and my husband was the only wage-earner. The amount of money my husband used to earn was not sufficient to take care of the needs of my children. Since I started working, I have managed to take care of my children. It has helped my husband to get rid of some financial burdens from his shoulders (Female, 4 years in the factory, USD100–150 per month)

Testing of the effect that interaction between managerial consideration and LO had on non-rank sensitive inclusion yielded insignificant results (b = 0.05, p > 0.05; see Table 5). Furthermore, the index of moderated mediation for this relationship was also insignificant (zero falling between the upper and lower confidence interval levels), so we thereby reject our sixth hypothesis.

Discussion

This research has provided an integrative resource perspective of workplace inclusion in light of the growing population of workers with low socioeconomic status worldwide. Based on the COR perspective, we identified the centrality of economic resources intersected with personal resources as a key workplace inclusion process for the well-being of employees with insufficient resources. Within hierarchically and geographically segregated societies where economic inequality is deeply entrenched (Bapuji et al., 2018), economic inclusion via fair employment practices requires multiple human agencies to adopt ethics and respectfully treat every worker as ends, not means, for economic growth (cf. Bowie, 2017). The recently proposed stakeholder governance perspective (Amis et al., 2020b), economic value creation by stakeholders (Bapuji et al., 2018), economic–social–economic cycle of inclusion (Fujimoto & Uddin, 2021), and inclusion concepts for low-wage workers (van Eck et al., 2021) encourage corporate leaders and other stakeholders to prioritize the interests of most exploited stakeholders in order to meet their economic needs. The key stakeholders prioritizing fair employment practices at low-wage workplaces may reverse the hierarchical discriminatory trends within the workforce, which are particularly imposed on female workers in the patriarchal society (cf. Markus, 2017; Ridgeway, 1991). Our study promotes the collective advancement of micro-level initiatives that might break the macro–micro–macro-status construction process, in which the macro-level inequitable context allows for micro-level inequitable resource distribution that in turn reinforces macro-status differences (Barney & Felin, 2013; Ridgeway et al., 1998). Our COR perspective for the least resourced workers also supports John Rawl’s perspective of guaranteeing basic liberties by improving the situation for the least well-off members of society as a central management approach (Amis et al., 2021). Notably, our study did not find the influence of managerial consideration and non-rank inclusion on life satisfaction. This finding contradicts previous studies that identified the importance of symbolic and emotional connections and non-task-oriented involvement in building social relationships for low-skilled workers in the western context (Holck, 2017; Janssens & Zanoni, 2008; van Eck et al. 2021). The context of this study of Bangladeshi workers in the RMG industry with significantly more severe employment conditions than previous studies in Western settings may provide insights into how those social resources alone cannot result in better life satisfaction for those workers (c.f., Alamgir et al., 2021). Since the workplace inclusion study took place for the first time in Global South, to our best knowledge, this study has signified the importance of contextual implicational differences in promoting the inclusive workplace and well-being of low-skilled workers between the Global South and the Global North.

Theoretical Contributions

Our study has made a number of theoretical contributions in COR and workplace inclusion research related to workers of low socioeconomic status in the Global South. First, we provided a COR concept of inclusion for those workers by departing from mainstream diversity and inclusion concepts of the sociopsychological tradition (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), addressing underrepresented resource/inclusion concepts that are more relevant to the Global South’s operant workers (cf. Amis et al., 2021; Bapuji, et al., 2018). Based on status construction theory, the economic resource differences between low- and high-skilled jobs are a major root of shared beliefs within high- and low-status groups, including the self-perception of those individuals with fewer economic resources as belonging to a low-status, less valued group (Ridgeway, 1991; Ridgeway & Balkwell, 1997; Ridgeway et al., 1998). To address the widespread economic inequality attached to the personal beliefs of workers who experience incomparable economic inequality in the global supply chain, this study highlighted organizational leaders’ central roles in demarcating employment practices that foster the equitable economic and social status of those workers via direct and indirect material creations (Amis et al., 2020a; Bapuji, 2015).