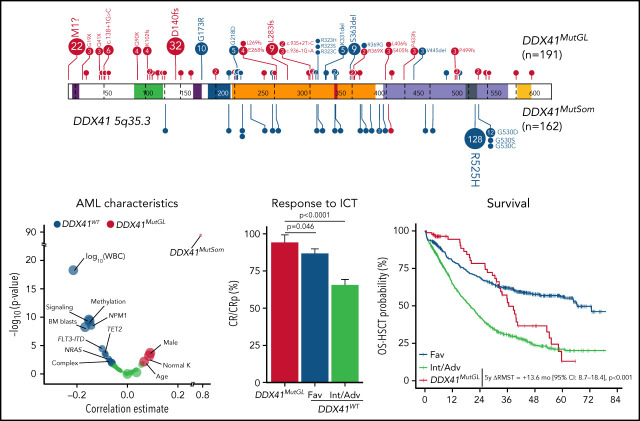

DDX41 germline mutations define the most common genetic syndrome predisposing to myeloid neoplasms (MN). Two papers highlight the genetic landscape and prognostic implications of germline DDX41-related MN. Li et al analyzed DDX41 variants and demonstrated that germline causal variants identify a population with a distinct AML subtype. The group, characterized by male predominance, late onset, and favorable prognosis, develop concurrent somatic DDX41 variants but rarely show the usual MN-associated somatic mutations. This contrasts to patients with variants of uncertain significance who develop MN with canonical MN-associated mutations, suggesting they define distinct entities. In the second article, Duployez et al confirmed the prognostic significance in 191 patients with DDX41 germline mutation, reporting higher remission rates and longer overall survival than patients without DDX41 germline mutation. Transplantation in first remission prolonged relapse-free survival but not overall survival.

Key Points

DDX41MutGL AML patients represent a unique entity with male sex skewing, older age, low leukocyte count, and few somatic genetic events.

DDX41MutGL AML patients have high response rates to intensive chemotherapy and a prolonged survival compared with Int/Adv DDX41WT patients.

Visual Abstract

Abstract

DDX41 germline mutations (DDX41MutGL) are the most common genetic predisposition to myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Recent reports suggest that DDX41MutGL myeloid malignancies could be considered as a distinct entity, even if their specific presentation and outcome remain to be defined. We describe here the clinical and biological features of 191 patients with DDX41MutGL AML. Baseline characteristics and outcome of 86 of these patients, treated with intensive chemotherapy in 5 prospective Acute Leukemia French Association/French Innovative Leukemia Organization trials, were compared with those of 1604 patients with DDX41 wild-type (DDX41WT) AML, representing a prevalence of 5%. Patients with DDX41MutGL AML were mostly male (75%), in their seventh decade, and with low leukocyte count (median, 2 × 109/L), low bone marrow blast infiltration (median, 33%), normal cytogenetics (75%), and few additional somatic mutations (median, 2). A second somatic DDX41 mutation (DDX41MutSom) was found in 82% of patients, and clonal architecture inference suggested that it could be the main driver for AML progression. DDX41MutGL patients displayed higher complete remission rates (94% vs 69%; P < .0001) and longer restricted mean overall survival censored at hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) than 2017 European LeukemiaNet intermediate/adverse (Int/Adv) DDX41WT patients (5-year difference in restricted mean survival times, 13.6 months; P < .001). Relapse rates censored at HSCT were lower at 1 year in DDX41MutGL patients (15% vs 44%) but later increased to be similar to Int/Adv DDX41WT patients at 3 years (82% vs 75%). HSCT in first complete remission was associated with prolonged relapse-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.43; 95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.88; P = .02) but not with longer overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.35-1.68; P = .5).

Introduction

Improvements in genetic screening technologies and their wide use in hematology have highlighted genetic germline predisposition in a significant proportion of myeloid malignancies.1,2 This has led the World Health Organization to consider these cases as distinct entities in the classification of myeloid neoplasms in 2016.3 Suggestive features of germline predisposition to myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) can include a personal or family history of cytopenia or cancer, physical or biological abnormalities, and early onset (although some individuals may be diagnosed at advanced age).4 In clinical practice, many patients do not exhibit any of these specificities, and they are diagnosed as having sporadic AML.5,6 The list of germline mutated genes predisposing to hematopoietic malignancies continues to expand.7 Myeloid neoplasms with germline predisposition are frequently identified according to routine gene panel sequencing at diagnosis, when a predisposition gene harbors a deleterious mutation with a variant allele frequency (VAF) suggesting a germline origin. Recognizing the hereditary condition of hematologic malignancies is crucial in adapting clinical management, especially allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), and for genetic counseling of patients and families.

The DDX41 gene encodes a DEAD-box RNA-helicase involved in RNA splicing, ribosomal biogenesis, and immune response.8-10 In a first report in 2015, Polprasert et al8 showed that DDX41 germline mutations (DDX41MutGL) promote MDS or AML development. Importantly, a causal DDX41 mutation with a VAF >40% identified in blood and/or bone marrow readily identifies germline variants, the germline origin being virtually always confirmed on skin fibroblast culture.11-13 We and others reported that DDX41 mutation was the most common genetic predisposition to MDS/AML, representing 2% of myeloid malignancies and up to 5% of AML, diagnosed at an age similar to sporadic cases.7,11,12,14,15 These retrospective cohorts provided some clinical description of DDX41-related AML,14,16,17 but comparative analysis with DDX41 wild-type (DDX41WT) AML is currently lacking. A relatively good outcome of DDX41MutGL AML has been suggested in small series with heterogeneous treatments, including intensive chemotherapy (ICT) and hypomethylating agents alone or in combination with venetoclax or lenalidomide.11-14,17-19 The prognostic impact of DDX41MutGL-driven AML still has to be confirmed in larger cohorts with more homogeneous treatments.

We report here a cohort of 191 patients newly diagnosed with DDX41MutGL AML. Among them, 86 were treated by ICT in 5 prospective clinical trials from the Acute Leukemia French Association (ALFA) and the French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO). We compared their characteristics and outcome with those of DDX41WT patients treated similarly (ie, with ICT with or without HSCT).

Methods

Patients

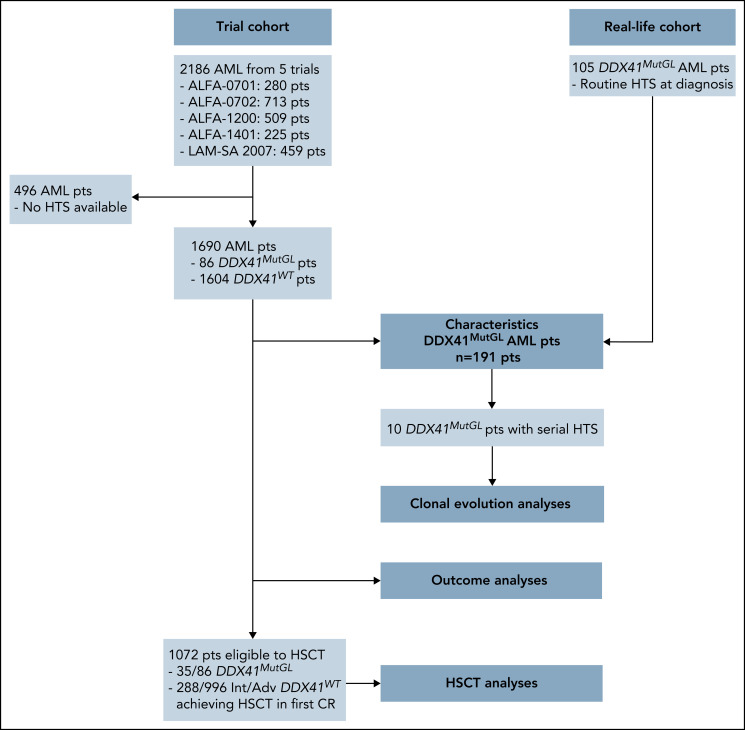

We report in this study 191 patients harboring a germline mutation in DDX41 at AML diagnosis (Figure 1). Eighty-six (45%) were enrolled in 5 prospective trials (clinical trial [CT] cohort) of the ALFA and the FILO cooperative study groups between January 2008 and March 2019: ALFA-0701 (clinicaltrials.gov identifier #NCT00927498),20,21 ALFA-0702 (#NCT00932412),22,23 ALFA-1200 (#NCT01966497),24,25 ALFA-1401 (#NCT02473146),26 and LAM-SA 2007 (#NCT00590837).15,27 All of them received ICT (details about clinical trials are provided in the supplemental Appendix, available on the Blood Web site). In the ALFA-0701 and ALFA-1401 trials, patients were randomized to receive gemtuzumab ozogamicin in combination with ICT. Patients were aged 18 to 59 years in the ALFA-0702 trial, 50 to 70 years in the ALFA-0701 trial, and ≥60 years in other trials. Eligibility criteria for enrollment in these trials included de novo AML except for patients in the ALFA-1200 trial, in which patients with AML secondary to prior MDS could be enrolled. Diagnostic material was available in 1690 patients and retrospectively sequenced by a targeted panel including the DDX41 gene. An additional 105 patients with DDX41MutGL AML (real-life [RL] cohort) were identified in 10 centers from routine next-generation sequencing (NGS) of AML diagnostic samples (Saint-Louis Hospital Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris [AP-HP], Cochin Hospital AP-HP, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire [CHU] Toulouse, Saint-Antoine Hospital AP-HP, CHU Bordeaux, CHU Nantes, CH Troyes, CH Orléans, CHU Angers, and CHU Lille). This study was approved by a National Review Board (as discussed by Sébert et al11) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and French ethics regulations.

Figure 1.

Flowchart summarizing patients included in each analysis. HTS, high throughput sequencing.

DNA sequencing

Mononuclear cells from bone marrow samples were isolated by Ficoll centrifugation, and peripheral blood was used only as an alternative when bone marrow DNA quality was insufficient for sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted by using standard procedures and studied by captured-based NGS. For patients enrolled in the ALFA-0701, ALFA-0702, ALFA-1200, and LAM-SA 2007 trials, libraries were prepared and analyzed as previously published.15,21,23,24 Because DDX41 was not covered in these older ALFA studies, all the samples with available material were screened for DDX41 mutation along with ALFA-1401 patients. For these patients, libraries were prepared according to the Twist NGS target enrichment solution (Twist Bioscience) following the manufacturer’s instructions with a 67-gene panel and run on NovaSeq (Illumina) (supplemental Appendix). Raw NGS data were analyzed with MuTect228 and Vardict29 for variant calling and the in-house NGSreport Software (CHU Lille) for data visualization, elimination of sequencing/mapping errors, and retention of variants with high-quality metrics. Additional cases in the RL cohort were analyzed in Saint-Louis Hospital AP-HP, CHU Toulouse, Saint-Antoine Hospital AP-HP, CHU Bordeaux, CHU Angers, and CHU Lille using standard pipelines as previously described.11,15

Variants were named according to the Human Genome Variation Society (GRCh37/hg19 build).30 Variant interpretation was performed considering minor allele frequencies in the public Genome Aggregation Database of polymorphisms (variants with minor allele frequency >0.02 in overall population/global ancestry or subcontinental ancestry were excluded), VAFs, prevalence, and clinical interpretation in our in-house database. Frameshift and nonsense variants were always considered as relevant mutations, and additional in silico predictions were performed whenever possible on missense and splicing variants. All diagnosis samples were also screened for the presence of FLT3-internal tandem duplications in an additional experiment by fragment analysis. Analyses were focused on the 35 genes shared by the 4 panels used in the CT cohort (ASXL1, BCOR, BCORL1, CBL, CEBPA, CSF3R, DDX41, DNMT3A, ETV6, EZH2, FLT3, GATA2, IDH1, IDH2, JAK2, KIT, KRAS, MPL, NPM1, NRAS, PHF6, PTPN11, RAD21, RUNX1, SETBP1, SF3B1, SMC1A, SMC3, SRSF2, STAG2, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, WT1, and ZRSR2). Inference of clonal architecture on diagnostic/relapse sample pairs was done by using the CALDER algorithm.31

DDX41 variants

DDX41 variants with a VAF higher than 40% suggesting possible germline origin and a frequency in a normal population <0.1% (Genome Aggregation Database) were consistently retained and collectively reviewed for classification according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology32 (supplemental Table 1). DDX41 variants were interpreted as causal if they were pathogenic or likely pathogenic by applying these guidelines. The concurrence of a somatic DDX41 mutation was also considered as strong evidence for causality. A systematic, integrated review in multidisciplinary sessions was performed for each DDX41 variant. Among 100 patients carrying DDX41 variants with a VAF higher than 40% in the CT cohort, 83 carried a variant interpreted as pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology guidelines. Three patients carried the p.G173R variant of undetermined significance, which was ultimately retained as causative because of the concomitance of a DDX41 somatic mutation in each case (supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Table 2). Fourteen non-null variants remained of undetermined significance (supplemental Table 3), and patients harboring them were therefore considered as DDX41WT. Pathogenicity of the DDX41 variants was used as an entry requirement in the additional 105 cases in the RL cohort (supplemental Table 4). The germline origin of DDX41 variants was confirmed by Sanger sequencing of cultured fibroblasts in 24 patients and on remission samples for 6 patients of the RL cohort.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical and ordinal variables are reported as number and proportion. Correlations and outcome analyses were performed only in patients from the CT cohort (Figure 1). Correlation between DDX41MutGL mutations and frequent covariates (>5% of patients) was realized by using point–biserial correlation for continuous variable, Fisher’s test for dichotomous variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test for ordinal variables. P values were corrected for multiple testing by using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (q values).33 Response and relapse were determined by using 2017 European LeukemiaNet (ELN-2017) criteria.34 Bivariate analyses stratified on the trial for response were performed by logistic regression, and collinearity was controlled by inspecting the variance inflation factors. Follow-up duration was calculated with the inverse method.

Overall survival (OS) analyses were considered from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Relapse-free survival (RFS) analyses were restricted to patients achieving complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete platelet recovery (CRp) after one or two courses and were considered from the date of response to the date of death, relapse, or last follow-up. OS and RFS were censored at transplantation in first CR when specified (OS-HSCT and RFS-HSCT) and were obtained according to the Kaplan-Meier method. Because proportional hazards assumptions were violated by the DDX41MutGL variable for Cox models for OS-HSCT and RFS-HSCT, we compared the difference in restricted mean survival times (RMST)35 according to DDX41MutGL status in bivariate analyses stratified on the clinical trial in all patients from the CT cohort. To understand the specific survival dynamics in DDX41MutGL patients, relapse- and nonrelapse-related deaths were considered as competing risks and were analyzed by using a Fine and Gray regression model.36 Finally, to study the impact of HSCT in first CR in DDX41MutGL and intermediate/adverse (Int/Adv) DDX41WT patients, HSCT was considered as a time-depending variable, and survival curves for OS and RFS were obtained by using the Simon-Makuch method and compared by using a time-dependent bivariate Cox model.

All tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was defined as a P value <.05 or a q value <0.05. All outcome analyses were stratified on the clinical trial. All analyses were performed with R version 3.5.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Clinical and biological characteristics of the 191 DDX41MutGL AML patients

A total of 191 AML patients with a causal DDX41MutGL variant were included in this study (Figure 1). Their characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2. Overall, 144 (75%) were male, and median age was 66 years (IQR, 59-70 years). They had leukopenia (median white blood cell count [WBC], 1.99 × 109/L; IQR, 1.46-2.60 × 109/L) and low bone marrow blast infiltration (median, 33%; IQR, 24%-47%). Most (75%) displayed a normal karyotype, and the most frequent cytogenetic alteration was trisomy 8 (5%). Only one patient had a complex karyotype, and 3 patients had core-binding factor AML.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients at AML diagnosis

| Characteristic | DDX41MutGL AML | DDX41WT AML, CT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | RL | CT | ||

| No. of patients | 191 | 105 | 86 | 1604 |

| Male | 144 (75%) | 80 (76%) | 64 (74%) | 866 (54%) |

| Age, y | 66 (59-70) | 66 (59-70) | 66 (61-69) | 64 (54-69) |

| Hb, g/dL | 10.4 (8.6-11.9) | 10.3 (8.3-11.9) | 10.7 (9.6-12.0) | 9.8 (8.6-10.8) |

| WBC, ×109/L | 1.99 (1.46-2.60) | 1.90 (1.42-2.45) | 2.00 (1.50-2.70) | 7.9 (2.5-31.1) |

| ANC, ×109/L | 0.62 (0.26-0.94) | 0.62 (0.27-0.96) | 0.60 (0.30-0.90) | ND |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 64 (39-110) | 63 (37-85) | 82 (42-171) | 85 (42-174) |

| BM blasts, % | 33 (24-47) | 30 (23-47) | 37 (28-47) | 58 (35-80) |

| Trial, n (% in trial) | ||||

| ALFA-0701 | NA | NA | 10 (5.4%) | 176 (94.6%) |

| ALFA-0702 | NA | NA | 15 (2.7%) | 531 (97.3%) |

| ALFA-1200 | NA | NA | 23 (5.3%) | 408 (94.7%) |

| ALFA-1401 | NA | NA | 15 (7.6%) | 182 (92.4%) |

| LAM-SA 2007 | NA | NA | 23 (6.9%) | 307 (93.1%) |

| FAB classification | ||||

| Available | 70 | 47 | 23 | ND |

| M0 | 7 (10%) | 5 (11%) | 2 (9%) | ND |

| M1 | 17 (25%) | 14 (30%) | 3 (13%) | ND |

| M2 | 42 (60%) | 24 (51%) | 18 (78%) | ND |

| M4 | 2 (3%) | 2 (4%) | 0 | ND |

| M5 | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | ND |

| M6 | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | ND |

| Cytogenetics | ||||

| Available | 156 | 80 | 76 | 1500 |

| Normal | 117 (75%) | 59 (74%) | 58 (77%) | 860 (57%) |

| Complex | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 139 (9%) |

| Trisomy 8 | 8 (5%) | 6 (8%) | 2 (3%) | 158 (11%) |

| Monosomy 5/del(5q) | 3 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 77 (5%) |

| Monosomy 7 | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 65 (4%) |

| Monosomy 17/del(17p) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 58 (4%) |

| ELN-2017 risk | ||||

| Available | 160 | 81 | 79 | 1545 |

| Favorable | 9 (5%) | 6 (7%) | 3 (4%) | 549 (36%) |

| Intermediate | 105 (66%) | 51 (63%) | 54 (68%) | 427 (28%) |

| Adverse | 46 (29%) | 24 (30%) | 22 (28%) | 569 (37%) |

Data are expressed as median (IQR) unless otherwise indicated.

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; BM, bone marrow; FAB, French-American-British; Hb, hemoglobin; NA, not applicable; ND, not defined.

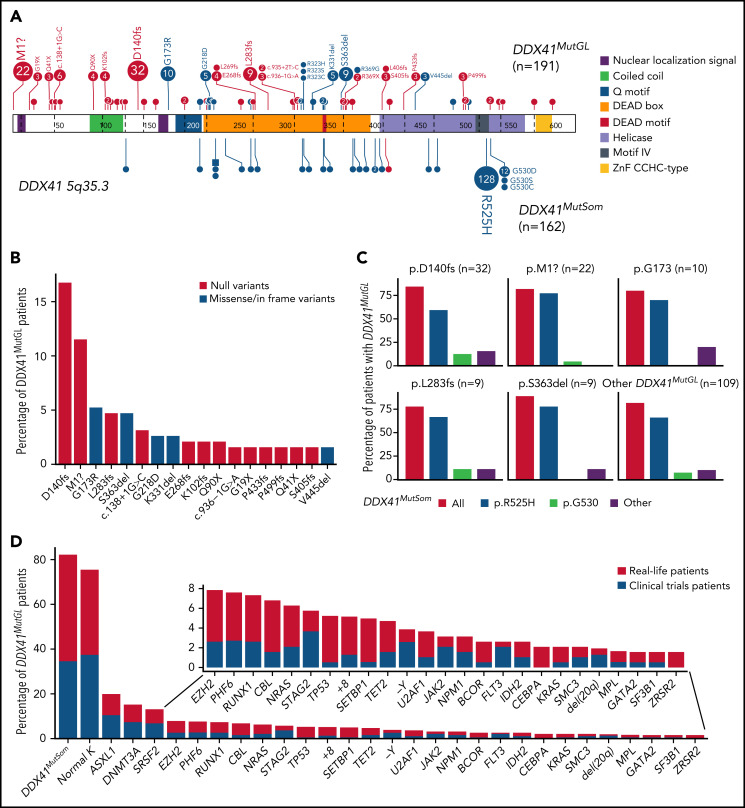

Figure 2.

Genetic characteristics of DDX41MutGL AML (n = 191). (A) Germline (top) and somatic (bottom) DDX41 variants identified in the present study. Functional domains are shown. Null variants (nonsense, frameshift, canonical ± 1 or 2 splice sites, and initiation codon) are in red; other variants (missense and inframe) are in blue. The figure was made with the PECAN online tool.48 (B) Proportions of the most common DDX41MutGL mutations identified in this study (only variants found in at least 3 patients are shown). (C) Proportions of DDX41MutSom mutations in patients with AML grouped according to the type of DDX41MutGL mutations. (D) Molecular and cytogenetic characteristics of the DDX41MutGL patients at AML diagnosis according to the cohort.

A total of 68 distinct DDX41MutGL variants were identified, including 34 never reported to date (Figure 2A; supplemental Tables 2-4). Most of these DDX41MutGL mutations were null variants (n = 46 of 68 [68%]); that is, either nonsense/frameshift or involving canonical splice sites or the initiation codon, thus representing 73% of all cases (n = 140 of 191). Eighteen DDX41MutGL variants were found in at least 3 patients, 10 were found in 2 patients, and the remaining 40 were identified in only 1 patient. The most frequent DDX41MutGL variants were p.D140fs (n = 32 [17%]), p.M1? (n = 22 [12%]), p.G173R (n = 10 [5%]), p.L283fs (n = 9 [5%]), and p.S363del (n = 9 [5%]) (Figure 2A-B). Of note, the frequency of the most frequent germline DDX41 variants was not statistically different between younger (<60 years) and older (≥60 years) patients (supplemental Figure 2A).

Most patients (82%) had also one (n = 152 [79%]) or two (n = 5 [3%]) somatic mutations in the DDX41 gene (DDX41MutSom), with a median VAF of 11% (IQR, 6%-18%). The vast majority of these DDX41MutSom variants were the hotspot p.R525H (n = 128 [79%]), with no significant difference between the most frequent DDX41MutGL mutations (Figure 2C). The mutational landscape was dominated by DDX41MutSom (82%), ASXL1 (20%), DNMT3A (15%), and SRSF2 (13%) mutations, whereas NPM1 (3%) and FLT3 (3%) alterations were rare (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 2B). The most frequent DDX41MutGL variants p.D140fs and p.M1? were not significantly associated with specific comutations. Patients with a DDX41MutSom variant had lower WBC count (median, 1.9 × 109/L vs 2.9 × 109/L; q value < 0.0001), lower bone marrow blast infiltration (32% vs 45%; q value = 0.001), and fewer NRAS mutations (3% vs 21%; q value = 0.01) compared with DDX41MutGL patients without DDX41MutSom. No significant difference was observed for other comutations (supplemental Figure 2C).

Baseline features of DDX41MutGL compared with DDX41WT AML

Presence of DDX41MutGL mutation was investigated in 1690 patients with AML enrolled in 5 prospective ICT trials (Figure 1). Characteristics at diagnosis of patients from this CT cohort are listed in Table 1. Overall, 930 (55%) were male, with a median age of 64 years (IQR, 54-69 years). Karyotype was normal in 58%, and ELN-2017 risk stratification was favorable in 34%, intermediate in 30%, and adverse in 36%.

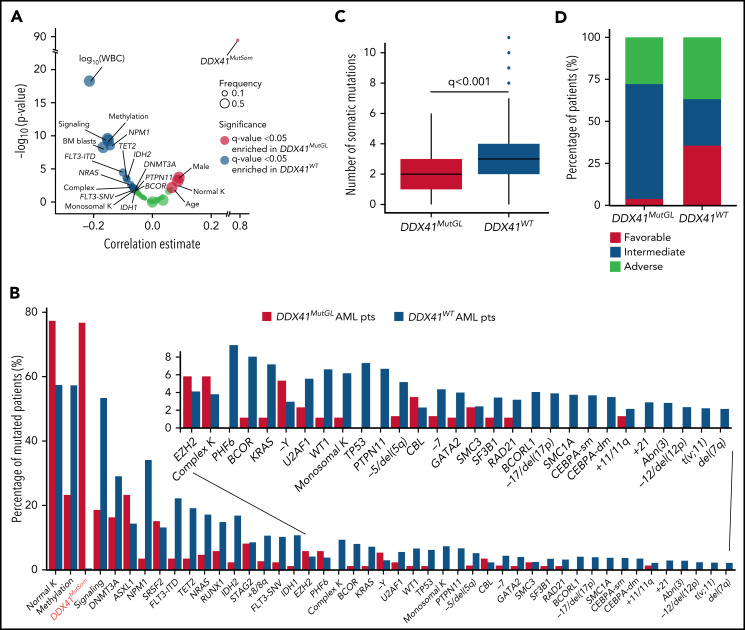

A causal DDX41MutGL variant was identified in 86 patients, resulting in a prevalence ranging from 3% in de novo AML patients aged 18 to 59 years (ALFA-0702) to 8% in de novo non-cytogenetically adverse AML patients aged >60 years (ALFA-1401 and LAM-SA 2007) (Table 1). DDX41MutGL AML patients were more often male (74% vs 54%; q value = 0.001). These patients were older (median, 66 vs 64 years; q value = 0.03), had lower WBC (median, 2.0 × 109/L vs 7.9 × 109/L; q value < 0.001) and bone marrow blast infiltration (median, 37% vs 58%; q value < 0.001), and had higher rates of normal karyotypes (77% vs 57%; q value < 0.001) and DDX41MutSom mutations (77% vs <1%; q value < 0.001) (Figure 3A-B; Table 1). Conversely, DDX41MutGL patients had fewer somatic mutations than DDX41WT patients (median, 2 [IQR, 1-3] vs 3 [IQR, 2-4]; q value < 0.001) (Figure 3C). Mutations frequent in sporadic de novo AML such as NPM1 and signaling (FLT3, NRAS, and PTPN11) and methylation (DNMT3A and TET2) genes were significantly less frequent in DDX41MutGL patients. Consequently, the majority (68%) of these DDX41MutGL patients were classified as intermediate risk by ELN-2017 (Figure 3D), whereas 28% were classified as adverse risk owing to the presence of ASXL1, RUNX1, or TP53 mutations. Of note, DDX41MutGL patients from the CT cohort had higher platelet counts (82 × 109/L vs 63 × 109/L; q value = 0.03) but were otherwise comparable to RL DDX41MutGL patients.

Figure 3.

Specific features of DDX41MutGL compared with DDX41WT AML patients. (A) Volcano plot representing the association between DDX41MutGL variants and clinical and biological covariates (estimate of the point–biserial correlation [continuous variables] or F [dichotomous variables] on the x-axis) and the significance of the difference, expressed on an inverted logarithmic scale on the y-axis. The P values were calculated by using the Mann-Whitney U test (continuous variables) or Fisher’s exact (dichotomous) test. The size of the circle corresponds to the frequency of the variable in the cohort. For statistical power consideration, we used only variables with frequency >1% in the whole cohort (ie, >15 patients). Tests were corrected for multitesting using false discovery rate (FDR). (B) Molecular and cytogenetic characteristics of patients with AML enrolled in the ICT trials according to DDX41MutGL status. (C) Box plots showing the number of co-occurring somatic mutations in DDX41MutGL and DDX41WT AML. The P value was calculated by using the Mann-Whitney U test and corrected for multitesting by using FDR. (D) ELN-2017 stratification according to DDX41MutGL status.

Prognostic significance of DDX41MutGL mutations in AML patients treated with ICT

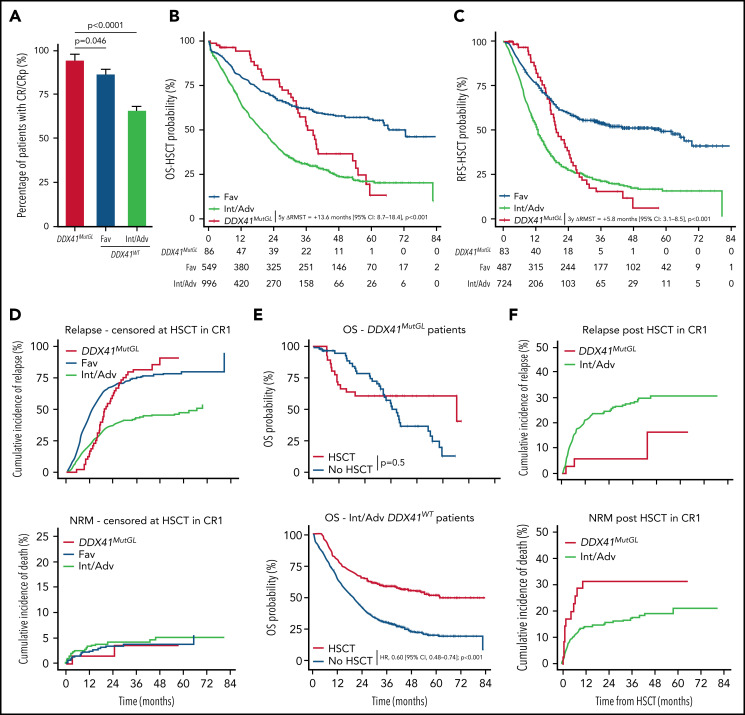

After one induction course, 81 (94%) DDX41MutGL, 474 (87%) favorable risk according to ELN-2017 (Fav) DDX41WT, and 648 (66%) Int/Adv DDX41WT AML patients achieved CR/CRp. Among the five DDX41MutGL AML patients not in CR/CRp, one died during induction, two died of the disease, and two patients who received salvage therapy achieved CR. In a bivariate analysis stratified on the clinical trial (supplemental Figure 3A), presence of a DDX41MutGL mutation was associated with significantly higher CR/CRp rates than Fav DDX41WT (odds ratio [OR], 2.60; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.11-7.62; P = .046) and Int/Adv DDX41WT (OR, 8.91; 95% CI, 3.93-25.63; P < .0001) (Figure 4A; supplemental Table 5) patients. Adjustment for age and sex did not affect the results (supplemental Table 6), and there was no significant interaction between DDX41MutGL status and the trial.

Figure 4.

Outcome of patients with DDX41MutGL compared with DDX41WT AML. (A) CR/CRp rates after one induction course in DDX41MutGL compared with DDX41WT AML patients stratified according to the ELN-2017 classification. P values from the bivariate regression for response are reported. Error bars represent the 95% CIs calculated according to the exact method. OS (B) and RFS (C) censored at HSCT in CR1 in patients with DDX41MutGL (red) vs DDX41WT ELN-2017 favorable (blue) and DDX41WT ELN-2017 Int/Adv (green). Results of the RMST analyses at 5 years (OS-HSCT) and at 3 years (RFS-HSCT) are reported. (D) Cumulative incidence of relapse (top) and death (bottom) censored at HSCT in CR1 in DDX41MutGL and DDX41WT AML. (E) Simon-Makuch plot of OS according to achievement of HSCT in first CR in DDX41MutGL patients (top) and ELN-2017 Int/Adv DDX41WT patients (bottom). Results of the bivariate time-dependent Cox models are reported. (F) Cumulative incidence of relapse (top) and nonrelapse death (bottom) after HSCT in first CR.

After a median follow-up of 47.8 months (IQR, 38.5-59.7 months), median OS censored at HSCT (OS-HSCT) was 28.1 months (IQR, 10.7-82.7 months) and median RFS censored at HSCT (RFS-HSCT) was 18.7 months (IQR, 8.3-80.9 months) in the 1690 patients. Of note, the ELN-2017 risk stratification poorly discriminated long-term outcome in DDX41MutGL AML patients (supplemental Figure 3B). Median OS-HSCT for DDX41MutGL patients was 36.6 months (IQR, 26.3-55.2 months) compared with 26.8 months (IQR, 10.2-82.7 months) for DDX41WT patients (Figure 4B; supplemental Figure 3C). Median RFS-HSCT was 19.6 months (IQR, 15.2-28.1 months) for DDX41MutGL patients compared with 18.4 months (IQR, 7.9-80.9 months) for DDX41WT patients (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 3D). Because proportional hazards assumption was violated for the DDX41MutGL variable (supplemental Figure 4), we compared the differences of RMST in bivariate analyses stratified on the trial. At 5 years, DDX41MutGL patients had a prolonged restricted mean OS-HSCT compared with Int/Adv patients (difference in RMST, 13.6 months; 95% CI, 8.7-18.4; P < .001) but not compared with Fav patients (P = .3) (Table 2). Similarly, at 3 years, DDX41MutGL patients had a prolonged restricted mean RFS-HSCT compared with Int/Adv patients (difference in RMST, 5.8 months; 95% CI, 3.1-8.5; P < .001) but not compared with Fav patients (P = .3). Adjustment for age and sex did not change the results (supplemental Table 7), and the impact of DDX41MutGL seemed consistent across trials, despite the limited number of patients in each subgroup analysis (supplemental Table 8; supplemental Figure 3C-D). Interestingly, DDX41MutGL AML patients showed distinct relapse kinetics compared with DDX41WT patients. When considering relapse and death as competing risks, DDX41MutGL patients indeed had lower relapse rates censored at HSCT at 1 year (15% compared with 22% for Fav patients and 44% for Int/Adv patients), but relapse incidence subsequently increased to that of Int/Adv DDX41WT patients at 3 years (82% compared with 43% for Fav patients and 75% for Int/Adv patients) (Figure 4D).

Table 2.

Results of the bivariate RMST analyses

| OS-HSCT | 5 y ΔRMST (mo) | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDX41MutGL vs Int/Adv DDX41WT | 13.6 | 8.7 to 18.4 | <.001 |

| DDX41MutGL vs Fav DDX41WT | 2.6 | –2.7 to 7.9 | .3 |

| RFS-HSCT | 3 y ΔRMST (mo) | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDX41MutGL vs Int/Adv DDX41WT | 5.8 | 3.1 to 8.5 | <.001 |

| DDX41MutGL vs Fav DDX41WT | –1.3 | –4.0 to 1.4 | .3 |

Analyses were stratified on the clinical trial.

Impact of HSCT in first CR in DDX41MutGL AML

In the prospective ALFA and FILO trials, patients in first CR/CRp with nonfavorable AML according to standard classifications were eligible for allogeneic HSCT if they had a compatible sibling or HLA-matched unrelated donor (details about the different trials are provided in the supplemental Appendix). Thirty-five DDX41MutGL and 288 nonfavorable DDX41WT patients received allogeneic HSCT in first CR/CRp (supplemental Table 9). Among the DDX41MutGL patients, 12 (34%) had a related donor, including the three DDX41MutGL patients (9%) who relapsed after transplant (one very early at 2 months, one at 6 months, and one at 4 years). Eleven (31%) died without relapse within a median of 2.2 months (IQR, 1.8-6.6 months) after transplant. Nonrelapse causes of death in DDX41MutGL patients after transplant were sepsis in 5, graft-versus-host disease in 3, and hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome in 1; causes were unknown in 2. HSCT was associated with prolonged OS in the Int/Adv DDX41WT cohort (hazard ratio, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.48-0.74; P < .001) (Figure 4E) but not in the DDX41MutGL patients (P = .5). However, HSCT was still associated with prolonged RFS in this group (hazard ratio, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21-0.88; P = .02). Considering death and relapse post-HSCT as competing risk, 1-year nonrelapse mortality was 31% and 14% in transplanted DDX41MutGL and Int/Adv DDX41WT patients, respectively (Figure 4F). This difference was not significant, however, after adjustment for age and clinical trial (P = .13). DDX41MutGL had significantly fewer relapses post-HSCT than Int/Adv DDX41WT patients after adjustment for age and clinical trial (P = .015), with a 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse of 16% compared with 30% for Int/Adv DDX41WT patients.

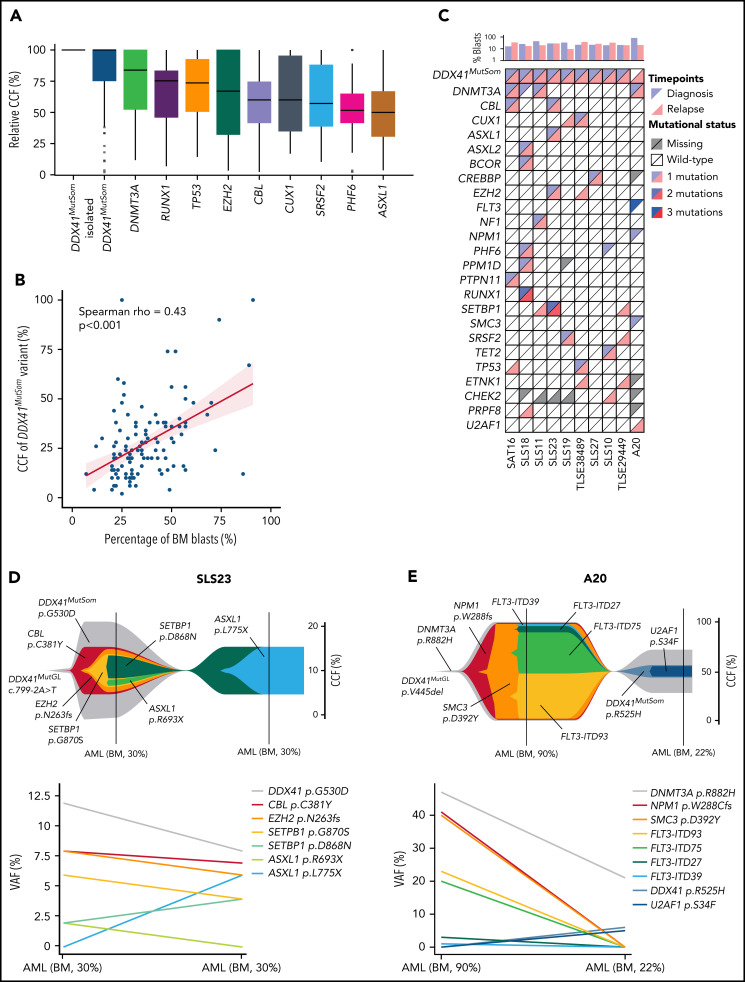

Clonal architecture of DDX41MutGLAML

We next investigated the co-occurrence and order of acquisition of somatic mutations to better understand the clonal architecture of DDX41MutGL AML. VAFs were converted to relative cancer cell fractions (CCFs) to limit the effects of bone marrow leukemic blast burden and copy-number changes. Overall, relative CCFs of the DDX41MutSom appeared to be higher than CCFs of other somatic mutations, suggesting that DDX41 biallelic alterations could be a driver of leukemic progression in DDX41MutGL patients (Figure 5A). Interestingly, when restricting the analysis to bone marrow samples at AML diagnosis, we observed a good correlation between bone marrow blast percentage and the VAF of DDX41MutSom mutation (Spearman rho = 0.43; P < .001) (Figure 5B). Material with sufficient blast infiltration was available at relapse after ICT treatment in 10 DDX41MutGL patients (Figure 5C). Of note, none of these 10 patients received HSCT in first CR. Clonal architecture of these 10 cases was reconstructed using the CALDER algorithm31 (Figure 5D-E; supplemental Figure 5). In most cases, DDX41MutSom was predicted to be in the founding and dominant clone, sometimes associated with an age-related clonal hematopoiesis-related mutation (ie, DNMT3A or TET2 mutations). In 9 of them, we found that most molecular alterations were shared between diagnosis and relapse, suggesting a true relapse from persistent leukemic cells, rather than a second AML. #SLS23 is a representative case of most DDX41MutGL AML clonal architectures. The dominant clone at diagnosis harbored DDX41MutSom as an initiating event and CBL, EZH2, SETBP1, and ASXL1 as secondary co-occurring mutations (Figure 5D). The initial clone was then selected at AML relapse with acquisition of a new ASXL1 mutation. Intriguingly, for patient #A20 (Figure 5E), the genetic distance between the first and the second AML was important, suggesting they might be 2 independent diseases. The first AML harbored DNMT3A, NPM1, SMC3, and FLT3 mutations, a clonal architecture frequently observed in sporadic (DDX41WT) patients. The clinical presentation was also reminiscent of sporadic AML, with a WBC count of 11 × 109/L and a high bone marrow blast infiltration of 90%. The patient then developed a second AML ten years after achieving first CR. This second leukemia harbored the same DNMT3A variant, with acquisition of new DDX41MutSom and U2AF1 mutations, and presented with leukopenia and low bone marrow blast infiltration (22%), as typically observed in DDX41MutGL patients. Together, our observations suggest that DDX41MutSom mutations could act as the main driver event of MDS/AML and trigger blast accumulation in the bone marrow and ineffective hematopoiesis with subsequent leukopenia.

Figure 5.

Clonal architecture of DDX41MutGL AML. (A) Relative CCFs of somatic mutations. CCFs are normalized on the highest CCF in each patient (assuming a linear accumulation of mutations). Isolated DDX41MutSom mutations are considered separately for unbiased representation. Only the most recurrent mutations are shown. (B) Correlation between the percentage of bone marrow blasts and the CCFs of DDX41MutSom variants. Results of the Spearman correlation test are reported. (C) Mutational landscape of 10 diagnostic/relapse DDX41MutGL AML sample pairs. Each column represents a single patient. (D-E) Fish plots derived from CALDER clonal architecture inference (upper panel) and corresponding raw VAF (lower panel) visualizing patterns of clonal evolution in 2 characteristic DDX41MutGL AML patients.

Discussion

In this large cohort of newly diagnosed, mainly de novo AML patients, the prevalence of DDX41MutGL mutations was 3% in young adults and 8% in elderly patients. This result is in line with the report from Li et al14 who found a prevalence of DDX41MutGL of 5.3% in adult AML. The spectrum of the DDX41 variants reported here reflects founder events restricted to the European population. All of them have been reported as highly recurrent in this population8,11,12,16,37 but are rare in Asian subjects.38,39 Notably, the p.G173R variant has been reported as a molecular hotspot, especially in French patients with myeloid malignancies.11 In our current cohort of 191 DDX41MutGL AML patients, we have highlighted the specific characteristics of DDX41MutGL-driven AML, suggesting it should be considered as a distinct entity. In line with previous descriptions,8,16,37,40 DDX41MutGL patients were significantly older than DDX41WT patients with a significant male sex skewing (sex ratio male:female, ∼3:1). DDX41MutGL AML was associated with low proliferative profile, low leukocyte count and bone marrow blast infiltration, and a marked differentiation blockade with a preferentially M2 morphologic aspect according to the French-American-British classification. Considering that germline DDX41 mutations also predispose to clonal cytopenia of unknown significance and MDS,41 this shows that DDX41MutGL patients can develop a continuum of hematologic malignancies, from clonal hematopoiesis, MDS with and without blasts excess, to low blast count AML. The karyotype was mainly normal, and a somatic DDX41 mutation was the sole recurrent genetic driver event in most cases. These DDX41MutSom mutations affected mainly the 2 hotspots, p.R525H and p.G530D/C/S.8,11,13 DDX41MutSom have been shown to be a common feature of disease progression in DDX41MutGL patients,9,39 although they are very rare (0.4%) in DDX41WT individuals.11 Clonal architecture inference analyses in our current cohort suggest that DDX41MutSom is the first driver event leading to bone marrow blast accumulation.

We acknowledge that the number of diagnostic/sample pairs was limited, and future studies using high-throughput single-cell multi-omics technology should investigate the genetic clonal architectures of these AML at the single-cell level. Chlon et al9 recently showed that DDX41MutSom-positive cells may exacerbate ineffective hematopoiesis (and subsequent leukopenia) in the context of DDX41MutGL. These observations suggest that biallelic (MutGL/MutSom) DDX41 mutations may trigger complete differentiation blockade, blast accumulation, and cytopenia, leading to AML. Stability of DDX41MutSom and comutations at relapse suggest a strong driver impact of the somatic hit, with persistence of leukemic cells after chemotherapy treatment and relapse from the same leukemic clone. A very small fraction of patients, <5% in our study, developed AML without DDX41MutSom but harbored common cytogenetic or molecular abnormalities according to the World Health Organization classification (supplemental Table 10). These patients might represent sporadic, DDX41MutGL-unrelated AML.

In this cohort of patients with AML homogeneously treated with ICT, DDX41MutGL was associated with a significantly higher CR/CRp achievement in multivariate analysis. However, the prognostic impact of DDX41MutGL on long-term outcome is more complex. Indeed, DDX41MutGL AML displayed specific relapse kinetics, with a lower relapse risk during the first year (15% vs 44% for Int/Adv DDX41WT patients), but the relapse incidence increased during the second and third years and reached similar relapse rates as Int/Adv DDX41WT patients at 3 years. This might explain why some studies with shorter follow-up report a very good outcome in DDX41MutGL AML patients.17 These delayed relapses also suggest a specific model of disease progression, as already described in other AMLs with germline predispositions. In contrast to familial AML with germline CEBPA mutations, in which late relapses seem to be a second independent AML,42 DDX41MutGL relapses appear to derive from persistent leukemic cells.

Because DDX41MutGL-AML are usually classified as intermediate (normal karyotype without category-defining lesion) or adverse (ASXL1, RUNX1, or TP53 comutations) risk according to the ELN-2017 classification, most patients are eligible for allogeneic HSCT in first CR. Interestingly, HSCT was associated with prolonged RFS in DDX41MutGL patients, but this finding did not translate into a prolonged OS. We indeed observed an unexpected high rate of early nonrelapse causes of death within the first year (31% vs 14% in the Int/Adv DDX41WT cohort), but this difference was not significant when we adjusted for age, as DDX41MutGL patients who underwent transplant were significantly older than transplanted DDX41WT patients (supplemental Table 9). Only three DDX41MutGL patients relapsed after HSCT, and all of them underwent transplant with a related donor. Chimerism and DNA sequencing information at relapse and donor DDX41MutGL status were unfortunately not available for these 3 patients, and we cannot exclude that these relapses are donor cell leukemias. We acknowledge that the number of transplanted DDX41MutGL patients is small (n = 35), and these results must be confirmed in greater patient numbers. If validated, the results might suggest that specific HSCT management programs can benefit DDX41MutGL patients, including conditioning regimens and intensity, HSC sources, and graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. This may reflect the influence of genetically “healthy” (unmutated) hematopoietic cells and a non-hematopoietic environment in which the leukemic clone expands, as suggested by a ddx41 loss-of-function mouse model.43 This may also imply other roles of the constitutionally mutated protein in cell pathway regulations or immune response.44,45

Recently, Li et al14 reported favorable outcomes in the first year of treatment of DDX41MutGL patients mostly treated with hypomethylating agents alone (n = 4) or in combination with venetoclax (n = 13). Although we observed a very high CR rate with ICT, alternative strategies or other consolidation approaches may therefore also be particularly interesting in this specific population,25 and prospective evaluations are warranted. Compared with other predisposing syndromes, incomplete penetrance, the frequent lack of personal or familial history, and the older age at onset of malignancy make the recognition of DDX41MutGL individuals challenging in clinical practice. Considering the specific clinical and prognosis features of DDX41MutGL patients reported in our study, the possible adaptation of HSCT modalities, and donor selection to exclude asymptomatic DDX41MutGL family donor,46,47 we recommend screening for DDX41 mutations at AML diagnosis in all patients.

In conclusion, we evaluated for the first time the prognostic impact of DDX41 mutations in a large cohort of AML patients prospectively treated with ICT. Our data show that DDX41MutGL-AML represents a distinct AML entity associated with better outcomes. HSCT in first CR effectively prevented relapse, but this did not translate into a prolonged OS. These results suggest that consolidation and maintenance strategies might be refined in these patients.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all ALFA and FILO investigators. They also thank Lamya Haddaoui and Krishshanti Sinnadurai (tumor bank for the FILO group, no. BB-033-00073, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris) and Christophe Roumier (tumor bank for the ALFA group, certification NF 96900-2014/65453-1) for handling, conditioning, and storing patients’ samples. The work of all clinical research assistants is also acknowledged.

This study was supported by the French Cancer National Institute (InCa–PHRC 2007/1911 and PRTK TRANSLA10-060).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: N.D., L. Largeaud, M.D., E.D., and M.S. designed the study; N.D., L. Largeaud, M.D., R.K., J.R., A. Bidet, E.C., L. Larcher, F.D., P.H., L.F., O.K., A. Bouvier, Y.L.B., J.S., C.P., E.D., and M.S. performed biological analysis and interpreted the data; M.D., R.I., and H.D. performed statistical analysis; J. Lambert, J. Lemoine, J.D., M.O., A.S., L.A., P.F., X.T., J.-B.M., C.G., C.R., A.P., R.I., H.D., and M.S. managed patients and provided clinical data; and N.D., L. Largeaud, M.D., and M.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marie Sébert, Service Hématologie Sénior, INSERM/CNRS UMR 944/7212, Hôpital Saint-Louis, 1 av Claude Vellefaux, 75010 Paris, France; e-mail: marie.sebert@aphp.fr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Godley LA. Germline mutations in MDS/AML predisposition disorders. Curr Opin Hematol. 2021;28(2):86-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klco JM, Mullighan CG. Advances in germline predisposition to acute leukaemias and myeloid neoplasms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(2):122-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391-2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenwarth L, Caulier A, Lachaier E, et al. Hereditary predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia in older adults. HemaSphere. 2021;5(4):e552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tawana K, Drazer MW, Churpek JE. Universal genetic testing for inherited susceptibility in children and adults with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia: are we there yet? Leukemia. 2018;32(7):1482-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drazer MW, Kadri S, Sukhanova M, et al. Prognostic tumor sequencing panels frequently identify germ line variants associated with hereditary hematopoietic malignancies. Blood Adv. 2018;2(2):146-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang F, Long N, Anekpuritanang T, et al. Identification and prioritization of myeloid malignancy germline variants in a large cohort of adult patients with AML. Blood. 2022;139(8):1208-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polprasert C, Schulze I, Sekeres MA, et al. Inherited and somatic defects in DDX41 in myeloid neoplasms. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(5):658-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chlon TM, Stepanchick E, Hershberger CE, et al. Germline DDX41 mutations cause ineffective hematopoiesis and myelodysplasia. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(11):1966-1981.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z, Yuan B, Bao M, Lu N, Kim T, Liu YJ. The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(10):959-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sébert M, Passet M, Raimbault A, et al. Germline DDX41 mutations define a significant entity within adult MDS/AML patients. Blood. 2019;134(17):1441-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bannon SA, Routbort MJ, Montalban-Bravo G, et al. Next-generation sequencing of DDX41 in myeloid neoplasms leads to increased detection of germline alterations. Front Oncol. 2021;10:582213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qu S, Li B, Qin T, et al. Molecular and clinical features of myeloid neoplasms with somatic DDX41 mutations. Br J Haematol. 2021;192(6):1006-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li P, White T, Xie W, et al. AML with germline DDX41 variants is a clinicopathologically distinct entity with an indolent clinical course and favorable outcome. Leukemia. 2022;36(3):664-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Largeaud L, Cornillet-Lefebvre P, Hamel J-F, et al. ; French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO) . Lomustine is beneficial to older AML with ELN2017 adverse risk profile and intermediate karyotype: a FILO study. Leukemia. 2021;35(5):1291-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewinsohn M, Brown AL, Weinel LM, et al. Novel germ line DDX41 mutations define families with a lower age of MDS/AML onset and lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 2016;127(8):1017-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alkhateeb HB, Nanaa A, Viswanatha DS, et al. Genetic features and clinical outcomes of patients with isolated and comutated DDX41-mutated myeloid neoplasms. Blood Adv. 2022;6(2):528-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abou Dalle I, Kantarjian H, Bannon SA, et al. Successful lenalidomide treatment in high risk myelodysplastic syndrome with germline DDX41 mutation. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(2):227-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Negoro E, Radivoyevitch T, Polprasert C, et al. Molecular predictors of response in patients with myeloid neoplasms treated with lenalidomide. Leukemia. 2016;30(12):2405-2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castaigne S, Pautas C, Terré C, et al. ; Acute Leukemia French Association . Effect of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on survival of adult patients with de-novo acute myeloid leukaemia (ALFA-0701): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2012;379(9825):1508-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fournier E, Duployez N, Ducourneau B, et al. Mutational profile and benefit of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2020;135(8):542-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas X, de Botton S, Chevret S, et al. Randomized phase II study of clofarabine-based consolidation for younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia in first remission. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(11):1223-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenwarth L, Thomas X, de Botton S, et al. A personalized approach to guide allogeneic stem cell transplantation in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2021;137(4):524-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardin C, Pautas C, Fournier E, et al. Added prognostic value of secondary AML-like gene mutations in ELN intermediate-risk older AML: ALFA-1200 study results. Blood Adv. 2020;4(9):1942-1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itzykson R, Fournier E, Berthon C, et al. Genetic identification of patients with AML older than 60 years achieving long-term survival with intensive chemotherapy. Blood. 2021;138(7):507-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambert J, Lambert J, Lemasle E, et al. Replacing the anthracycline by gemtuzumab ozogamicin in older patients with de novo standard-risk acute myeloid leukemia treated intensively—results of the randomized ALFA1401-Mylofrance 4 Study. Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1):31. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pigneux A, Béné MC, Salmi L-R, et al. ; French Innovative Leukemia Organization . Improved survival by adding lomustine to conventional chemotherapy for elderly patients with AML without unfavorable cytogenetics: results of the LAM-SA 2007 FILO Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(32):3203-3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benjamin D, Sato T, Cibulskis K, et al. Calling somatic SNVs and indels with Mutect2. bioRxiv. 2 December 2019;861054. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai Z, Markovets A, Ahdesmaki M, et al. VarDict: a novel and versatile variant caller for next-generation sequencing in cancer research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(11):e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogino S, Gulley ML, den Dunnen JT, Wilson RB; Association for Molecular Pathology Training and Education Committee . Standard mutation nomenclature in molecular diagnostics: practical and educational challenges. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9(1):1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers MA, Satas G, Raphael BJ. CALDER: inferring phylogenetic trees from longitudinal tumor samples. Cell Syst. 2019;8(6):514-522.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. ; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee . Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 1995;57(1):289-300. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uno H, Claggett B, Tian L, et al. Moving beyond the hazard ratio in quantifying the between-group difference in survival analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(22):2380-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quesada AE, Routbort MJ, DiNardo CD, et al. DDX41 mutations in myeloid neoplasms are associated with male gender, TP53 mutations and high-risk disease. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(7):757-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeda J, Yoshida K, Makishima H, et al. Genetic predispositions to myeloid neoplasms caused by germline DDX41 mutations. Blood. 2015;126(23):2843. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polprasert C, Takeda J, Niparuck P, et al. Novel DDX41 variants in Thai patients with myeloid neoplasms. Int J Hematol. 2020;111(2):241-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cardoso SR, Ryan G, Walne AJ, et al. Germline heterozygous DDX41 variants in a subset of familial myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30(10):2083-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi E-J, Cho Y-U, Hur E-H, et al. Unique ethnic features of DDX41 mutations in patients with idiopathic cytopenia of undetermined significance, myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2022;107(2):510-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tawana K, Rio-Machin A, Preudhomme C, Fitzgibbon J. Familial CEBPA-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2017;54(2):87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kon A, Nakagawa MM, Inagaki R, et al. Functional characterization of compound DDX41 germline and somatic R525H mutations in the development of myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2020;136(suppl 1):21-22. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang Y, Zhu Y, Liu Z-J, Ouyang S. The emerging roles of the DDX41 protein in immunity and diseases. Protein Cell. 2017;8(2):83-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinreb JT, Ghazale N, Pradhan K, et al. Excessive R-loops trigger an inflammatory cascade leading to increased HSPC production. Dev Cell. 2021;56(5):627-640.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger G, van den Berg E, Sikkema-Raddatz B, et al. Re-emergence of acute myeloid leukemia in donor cells following allogeneic transplantation in a family with a germline DDX41 mutation. Leukemia. 2017;31(2):520-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobayashi S, Kobayashi A, Osawa Y, et al. Donor cell leukemia arising from preleukemic clones with a novel germline DDX41 mutation after allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2017;31(4):1020-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLeod C, Gout AM, Zhou X, et al. St. Jude Cloud: a pediatric cancer genomic data-sharing ecosystem. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(5):1082-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.