Abstract

The development of fast and non-invasive techniques to detect SARS-CoV-2 virus at the early stage of the infection would be highly desirable to control the COVID-19 outbreak. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are porous materials with uniform porous structures and tunable pore surfaces, which would be essential for the selective sensing of the specific COVID-19 biomarkers. However, the use of MOFs materials to detect COVID-19 biomarkers has not been demonstrated so far. In this work, for the first time, we employed the density functional theory calculations to investigate the specific interactions of MOFs and the targeted biomarkers, in which the interactions were confirmed by experiment. The five dominant COVID-19 biomarkers and common exhaled gases are comparatively studied by exposing them to MOFs, namely MIL-100(Al) and MIL-100(Fe). The adsorption mechanism, binding site, adsorption energy, recovery time, charge transfer, sensing response, and electronic structures are systematically investigated. We found that MIL-100(Fe) has a higher sensing performance than MIL-100(Al) in terms of sensitivity and selectivity. MIL-100(Fe) shows sensitive to COVID-19 biomarkers, namely 2-methylpent-2-enal and 2,4-octadiene with high sensing responses as 7.44 x 105 and 9 x 107 which are exceptionally higher than those of the common gases which are less than 6. The calculated recovery times of 0.19 and 1.84 x 10−4 s are short enough to be a resuable sensor. An experimental study also showed that the MIL-100(Fe) provides a sensitivity toward 2-methylpent-2-enal. In conclusion, we suggest that MIL-100(Fe) could be used as a potential sensor for the exhaled breath analysis. We hope that our research can aid in the development of a biosensor for quick and easy COVID-19 biomarker detection in order to control the current pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, MIL-100, Sensor, VOCs biomarker, Density functional theory (DFT)

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak has dramatically altered society in the past two years. A fast and efficient method for detecting SARS-CoV-2 virus is necessary to control the spread of this disease. Although the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique provides high accuracy and specificity for COVID-19 diagnosis, its approach is hampered by its high cost and time-consuming nature. Sensor is another crucial tool that allows fast and easy detection of a given analyte. Various approaches and devices are being proposed and actively researched for SARS-CoV-2 virus detection. However, most of them rely on invasive diagnosis using materials taken from nasal or oral swabs, blood, sputum, and faces [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. On the other hand, diagnostics of exhaled breath are progressively becoming a primary non-invasive method for determining health status and disease types. Specific types of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) have been found in the exhaled breath of patients in addition to the common gases and VOCs [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. Therefore, “breath print” or “biomarker” could be considered to determine the current health status with the ability to predict future outcomes [12]. Due to the easy, rapid, and great potential in clinical diagnostics, this method has been successful in cases of cancer detection [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. Success in cancer biomarker detection drew our attention to study gas sensors for direct detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus from human breath.

To control the pandemic, the development of a simple and fast point-of-care sensing technology has piqued researchers' curiosity to achieve an ideal sensor for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Recently, studies have reported that the five most prominent VOCs in COVID-19 patients are ethyl butyrate (EB) [[17], [18], [19]], 2-methylpent-2-enal, nonanal, 1-chloroheptane, and 2,4-octadiene, with typical concentrations ranging from 10 to 250 parts per billion (ppb) [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. Recently, research has linked these specific breath VOCs with COVID-19 infection [[24], [25], [26], [27]]. However, adsorption and detection of VOCs related to COVID-19 are challenging due to their low concentration, fast adsorption equilibria, and the wide range of chemical functional groups in VOCs [28]. So far, only a few theoretical studies have been performed to predict sensing materials such as metal-doped carbon-based materials to detect EB biomarker [18,19,29]. Generally, metal-doped carbon-based materials are active materials for interacting with many gases. However, those studies did not consider other breath-borne gases, which can interfere with the selectivity and sensitivity of the sensing materials. Moreover, there is no experimental report on sensing the VOCs from exhaled breath in experiment.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are porous materials that contain metal nodes and organic linkers. MOFs are considered as an effective material in many disciplines such as gas capture and storage, catalysis, gas sensing, drug delivery, and gas separation [[30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]]. Porous structures of MOFs are tailorable by their building units and synthesis conditions, providing better sensitivity and selectivity than classic sensing materials. Zhang et al. explored the NUS-1 sensor, a 2D layered MOF with large channels, to detect VOCs such as benzene, cyclohexane, toluene, and p-xylene, which can be employed as cancer biomarkers [36]. In addition, graphene and MOF hybridization were synthesized to boost sensing performances. Graphene serves as an excellent conductive material, while MOFs have a high surface area and adsorption ability, which allows the monitoring of human health for non-invasive biomedical diagnostics [14]. MIL-100(M) or M3O(H2O)2OH(1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate)2 [37] is one of the most interesting MOFs. MIL-100 contains two coordinatively unsaturated metal sites (CUS) at the oxo-centered trimer unit, which could serve as the binding sites for gas adsorption. This carboxylate MOF is seen in many reactions [[38], [39], [40]]. Recently, MIL-100(Fe) was successfully evaluated as an ideal SERS substrate for toluene detection with a limit of detection (LOD) of 2.5 ppm. This proposed sensor can be utilized to detect VOCs biomarker for lung cancer with a low detection limit [15]. However, there is still no report on the application of MOFs for sensing COVID-19 biomarkers. Though there are some reports on MOFs for sensing cancer biomarkers, most cancer biomarkers (toluene, benzene, xylene) are non-polar VOCs. Biomarkers of COVID-19 are mainly esters or polar aprotic VOCs, which may require different sensing mechanisms.

Inspired by the great sensing performance of MOFs and the research gap mentioned above, we study MIL-100(Al, Fe) for sensing ethyl butyrate, 2-methylpent-2-enal, 1-chloroheptane, nonanal, and 2,4-octadiene, which are the five dominant biomarkers from COVID-19 patients [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22],41]. In addition, we also considered the interference gases from breath of healthy humans, such as isopropanol, acetone, methanol, ethanol, CO2, and H2O. To understand the sensing mechanism and gas sensing performance, we calculated geometrical structures, adsorption energy, the band gap, recovery time, and electronic properties of MIL-100(Al, Fe) before and after interaction with those biomarkers. We also performed experimental confirmation by synthesizing and characterizing these MOFs as sensing materials. We propose MIL-100(Fe) as a highly sensitive and selective material for the detection of 2-methylpent-2-enal which could be helpful in the fast screening of COVID-19 patients.

2. Methodology

2.1. Experimental study

The chemicals are analytical-grade reagents and were used without further purification. A Bruker D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer was used to collect the X-ray diffraction patterns of all samples using Cu Kα radiation (40 kV, 40 mA, λ = 1.5418 Å). Nitrogen adsorption−desorption was determined with a MicrotracBEL BELSORP-mini X at −196 °C. The samples were activated at 150 °C for 24 h under a vacuum before adsorption experiments. After sensing measurement, MOF pellets were ground into a fine powder with a mortar for FTIR and UV–Vis characterization. UV–Vis absorption spectra were collected on a PerkinElmer Lambda 1050 spectrophotometer. FTIR spectra were measured by a PerkinElmer frontier FT-IR in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode with a KBr window. High-resolution mass spectra of adsorbed VOCs were measured on Bruker Compact (APCI Q-TOF mode) and Bruker Autoflex speed (MALDI-TOF mode). The adsorbed VOCs were extracted from the MOFs by using dichloromethane. The impedance measurements were performed using an Autolab PGSTAT302 N equipped with FRA32 M module (Metrohm) over the frequency range of 1 Hz to 1 MHz with an input voltage amplitude of 300 mV and the current range of 1 mA. Impedance values were measured from Nyquist plots of MIL-100(Al, Fe) before and after VOC adsorption of preparation. Impedance data analysis was performed on NOVA software.

2.1.1. Synthesis of MIL-100 (Al)

MIL-100(Al) powder was prepared by dissolving 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid (1.01 g, 4.82 mmol) and Al(NO3)3·9H2O (1.80 g, 7.31 mmol) in distilled water (20 mL) with vigorous stirring. After that, acetic acid (4 mL) was added, see Fig. 1 . The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 min and then heated at 150 °C for 30 min in a microwave oven (MARS 6, CEM). The obtained product was washed three times with distilled water (20 mL) and dried at 80 °C for 12 h.

Fig. 1.

–(a) Schematic of the MIL-100(Al,Fe) synthesis procedure, selected cluster models representing the structural configuration, electrostatic potential maps, and Mulliken charge of (b) MIL-100(Al) and (c) MIL-100(Fe).

2.1.2. Synthesis of MIL-100 (Fe)

MIL-100(Fe) powder was prepared by dissolving 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid (0.84 g, 4.00 mmol) and FeCl3·6H2O (2.43 g, 6.01 mmol) in distilled water (30 mL). The reaction mixture was heated at 130 °C for 6 min in a microwave oven (MARS 6, CEM) and then maintained at 25 °C to cool down for 1 min. The orange solid was washed with distilled water (20 mL) and ethanol via centrifugation.

2.1.3. Sensing measurements

The properties determining gas sensitivity were tested by a homemade setup. First, the MIL-100(Al, Fe) (40 mg) was activated at 150 °C under vacuum for 24 h and further prepared as pellets with a diameter of 5 mm in the N2-filled glovebox. The MOF pellets were placed on top of the sealed container filled with the solvent (10 mL). The temperature of the system was controlled at the boiling temperature of each solvent to generate solvent vapor for 2 h. Subsequently, the MOF tablet was taken out from the sealed container and kept without air exposure for further characterization.

2.2. Models and calculation methods

2.2.1. GCMC simulations

To investigate the host-guest interaction and the preferable adsorption site of VOCs in MIL100 at room temperature (), the grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulation was conducted using a large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) software [42]. Since the low concentration of VOCs, we considered a low pressure at 1 mbar of 2-Methylpent-2-enal inside MIL100(Fe) as the case study. The tetragonal structure model of MIL100(Fe) used in the calculation is in a space group of I41/amd with , and . The primitive cell () was used as a simulation box consisting of 5440 atoms with periodic boundary conditions adopted in 3 dimensions, see Fig. S1. The Lennard-Jones (LJ) 12-6 potential was applied to describe the interatomic interaction with a global cutoff radius of . The parameterizations of interaction parameters were determined based on the universal force field (UFF) [43], while the cross-interaction parameters were calculated from the Lorentz-Berthelot mixing rule. The initial generation of bonds, angles, dihedrals, improper torsion, and pair interactions were done using lammps-interface code [44]. To simulate the grand canonical ensemble, the chemical potential (), the volume (V), and the temperature (T) were fixed along the simulation. During Monte Carlo (MC) steps, the molecule translations and the molecule rotations are induced with equal probability, while the attempts of GCMC exchange (insertion and deletion) are invoked at every 10 simulation steps. We first conducted steps to equilibrate the number of inserted molecules at particular conditions and then conducted another steps to sample thermodynamic behavior at equilibrium. The time average radial distribution function (RDF) was performed using the latter half part to evaluate the adsorption behavior from a statistical perspective.

2.2.2. DFT calculations

The results from GCMC suggested that the preferential adsorption site of 2-Methylpent-2-enal is at the Fe atom, see discussion in section 3. To accurately study the interaction of the VOCs at the active site of MIL-100, DFT calculation was adopted in this section. Due to a large unit cell of MIL-100, a finite-size M3O oxo-trimer cluster containing 126 atoms (Fig. 1) was cut from the crystallographic structures of MIL-100(Al, Fe) and saturated with carboxylate groups. The models of MIL-100(Al, Fe) contain two CUS metal centers and obtained by integrating one counter anion per oxo-centered trimers of metal(III) octahedra connecting 1,3,5-benzene tricarboxylate (BTC) linkers (M(III)3OOH(C6H5–C3O6)6) determined from X-diffraction [45]. It was reported that the type of counteranions (-Cl, –OH, –F, –SO4, …) does not significantly affect the all adsorption behavior of this MOF [46]. Here, we selected the MIL-100 configuration with –OH group in MIL-100(Al, Fe), assembled by a corner-sharing supertetrahedra consisting of M3O trimers (M = Al, Fe) and 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acids. This is also consistent with the synthesis condition of MOF samples without the use of strong acid (HF, HCl). A cluster with the inorganic M3O node saturated by formate is cleaved. This cluster model was also adopted by Fu et al. for studying the selectivity and sentitivity of MIL-100(Fe) to toluene, acetone and chloroform [15].

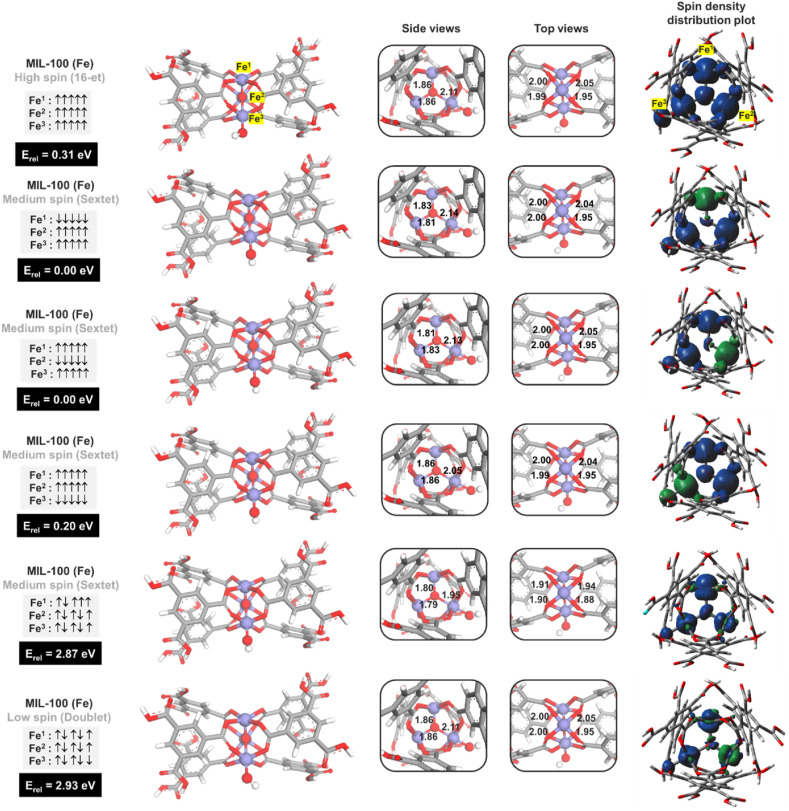

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed by Gaussian 16 code. We used Becke's three-parameter gradient-corrected exchange functional and the unrestricted Lee-Yang-Parr gradient-corrected correlation functional (UB3LYP) [[47], [48], [49]], and Grimme's D3-BJ dispersion correction (UB3LYP-D3BJ) [50] to perform geometry optimizations for all complexes. In these DFT calculations, the TZVP basis set [51] was used for C, O, H, Cl, and Al atoms, while for the Fe atom, we used the effective core potential (ECP) basis of Stuttgart and Bonn [52]. The B3LYP functional and TZVP basis set were chosen to study the NO adsorption and oxidation on MIL-100(M) where M = Al, Fe, Mn, Ru, Ti, Cr. This method of calculation could well explain the spin at the ground state structure and spin change during the reaction in all systems [38]. The MIL-100(Al) model shows stability at the singlet state since all electrons are fully filled. However, in the case of MIL-100(Fe), there are many possible spin states that need to be considered. We have checked the six spin states covering from low to high spin configurations, (1,1,-1), (1,1,1), (−5,5,5), (5,-5,5), (5,5,-5), and (5,5,5). Noted that, in the case of sextets, which represent an antiferromagnetic state, there are three possibilities that the five spin-down electrons are located at Fe1, Fe2, or F3, respectively. From the calculations, we found that the sextet state with a spin configuration of (+5, −5, +5) provided the most stable state, as demonstrated in Fig. 2 , which supports the experiment that MIL-100(Fe) shows high spin state [53,54]. The IR spectrum of all minimum structures was calculated to help us confirm the presence of gas molecules adsorbed inside the MOFs in our experiment. For the vibrational frequencies, we employed a universal scale factor of 0.972 to counterbalance the systematic errors caused by an insufficient basis set and vibrational anharmonicity [55].

Fig. 2.

Structural property and relative energy of cluster models with different spin states of MIL-100(Fe). Spin density distribution plot (isovalue 0.005 e/Å3).

All atomic charges in this work were simulated by the Mulliken charge method [56]. The adsorption energy of the adsorbed molecules and MIL-100 was calculated according to the equation:

| Eads= Egas/MIL-100−EMIL-100– Egas | (1) |

where, E gas/MIL-100, E MIL-100, and E gas refer to the total energies of the adsorbed VOC gas on MIL-100, the bare MIL-100, and the isolated VOCs gas, respectively. A negative value represents strong adsorption of the VOC on the MOF.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. GCMC calculation

Most dynamic simulation studies of metal-organic frameworks have focused on the adsorption and transportation of small molecules, such as H2, CO2, H2O, CH4, and hydrocarbons [57,58]. In this work, the host-guest interaction of 2-Methylpent-2-enal, one of the Biomarkers, inside the framework of MIL-100(Fe) has been studied using GMCM simulation at low pressure, where host-guest interactions is dominate. Fig. S1 shows a snapshot of 2-Methylpent-2-enal in MIL-100(Fe) at 300K. It is clearly seen that a 2-Methylpent-2-enal is located inside the pore of MIL-100(Fe) near the FeO3 area, which is known as the active site for gas interactions [[38], [39], [40]].

The radial distribution functions (RDFs) between framework atoms of MIL-100(Fe) and different atoms of 2-Methylpent-2-enal have been calculated to identify the preferential adsorption sites. RDFs between the oxygen atom of 2-Methylpent-2-enal (OVOC) and different atoms of MIL-100(Fe) and RDFs between the Fe atoms of MIL-100(Fe) and different atoms of 2-Methylpent-2-enal are shown in Fig. S2. The most preferential site can be identified by quantifying all the distances of host-guest interactions. RDFs show that the most left peaks belong to the interaction distances between the Fe atoms of MIL-100(Fe) and the O atom of 2-Methylpent-2-enal, which are around 2.5–3 Å, indicating that Fe atoms are the preferential adsorption sites for 2-Methylpent-2-enal.

3.2. Cluster models of MIL-100(Al, Fe)

To understand the adsorption performance of MIL-100(Al, Fe), we first investigated the electronic and structural properties of MIL-100(Al, Fe). The MIL-100(Al) model shows stability at the singlet state since all electrons are fully filled. However, in the case of MIL-100(Fe), there are many possible spin states that need to be considered. We have checked the six spin states covering from low to high spin configurations, (1,1,-1), (1,1,1), (−5,5,5), (5,-5,5), (5,5,-5), and (5,5,5). Noted that, in the case of sextets, which represent an antiferromagnetic state, there are three possibilities that the five spin-down electrons are located at Fe1, Fe2, or F3, respectively. From the calculations, we found that the sextet state with a spin configuration of (+5, −5, +5) provided the most stable state, as demonstrated in Fig. 2, which supports the experiment that MIL-100(Fe) shows high spin state [53,54]. Fig. 1b-c shows the most table structure of MIL-100(Al, Fe) clusters with crucial bond lengths. In MIL-100(Al), the optimized bond distances between Al and O from a ligand node are around 1.85–1.91 Å, while the Fe–O bond lengths for MIL-100(Fe) are 1.95–2.04 Å. The metal clusters of MOF materials, especially those with the CUS, are generally considered to be the active sites for adsorptions of small molecules, including VOCs. The Mulliken charge and electrostatic potential maps reveal that the open M1 site with a positive charge is the binding site for the incoming gases.

3.3. Adsorption of VOCs molecules on MIL-100 (Al, Fe)

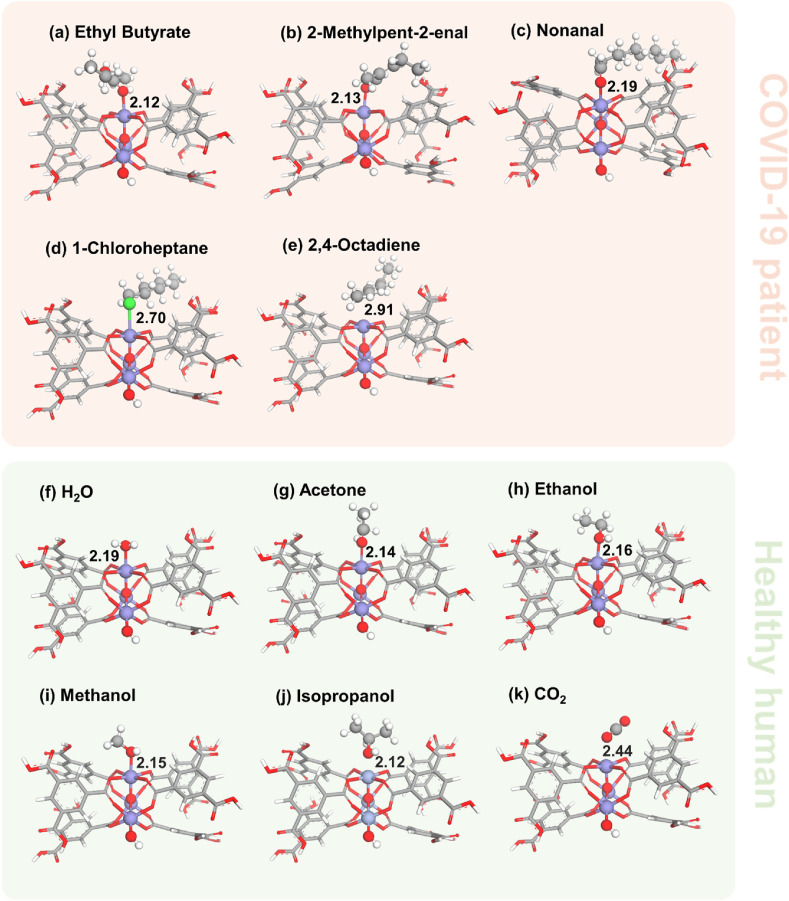

Here, we initially focus on the biomarker adsorption and sensor performance of MIL-100(Al, Fe). The first step in comprehending the sensor performance is the adsorption of biomarkers. All of the structures are fully relaxed during the optimization, and their adsorption energies are analyzed to quantify the most stable adsorption configuration. Fig. 4 illustrates the most stable optimized structure of all biomarkers on MIL-100(Fe), while those on MIL-100(Al) are depicted in Fig. S3. The adsorbed biomarker molecule exhibits varied positions and orientations. Moreover, adsorption properties, interaction distance, the net charge transfer, HOMO and LUMO energies, the band gap energy, and recovery time in different conditions of the stable configuration are tabulated in Table 1 and Table S1 for MIL-100(Fe) and MIL-100(Al), respectively.

Fig. 4.

Experimental and calculated FTIR of 2-Methylpent-2-enal on a) MIL-100 (Al) and b) MIL-100 (Fe).

Table 1.

The calculated VOCs adsorption energy (Eads), HOMO-LUMO energy level, energy band gap (Eg), sensing response of the system after adsorption (SR), interaction distance (D) between the molecule and MIL-100(Fe), Charge transfer (Δq), and recovery time (τ) at 398.15K.

| System | Eads(eV) | HOMO (eV) | LUMO (eV) | Eg(eV) | SR | D(Å) | Δq € | τ (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIL-100(Fe) | −7.88 | −4.24 | 3.63 | |||||

| EthylButyrate-MIL-100(Fe) | −1.17 | −7.59 | −3.85 | 3.74 | 6.76 | 2.106 | 0.247 | 2.56 |

| 2-Methylpent-2-enal-MIL-100(Fe) | −1.08 | −6.75 | −3.81 | 2.94 | 7.44 x 105 | 2.128 | 0.293 | 0.19 |

| Nonanal-MIL-100(Fe) | −1.16 | −7.60 | −3.89 | 3.71 | 3.92 | 2.186 | 0.254 | 1.85 |

| 1-Chloroheptane-MIL-100(Fe) | −0.76 | −7.72 | −4.02 | 3.70 | 2.80 | 2.702 | 0.220 | 1.49 x 10−5 |

| 2,4-Octadiene-MIL-100(Fe) | −0.84 | −6.65 | −3.96 | 2.69 | 9.02 x 107 | 2.913 | 0.291 | 1.84 x 10−4 |

| H2O-MIL-100(Fe) | −0.90 | −7.73 | −4.01 | 3.71 | 3.69 | 2.187 | 0.251 | 9.98 x 10−4 |

| Acetone-MIL-100(Fe) | −1.02 | −7.57 | −3.85 | 3.73 | 5.08 | 2.143 | 0.273 | 2.94 x 10−2 |

| Ethanol-MIL-100(Fe) | −1.09 | −7.67 | −3.95 | 3.72 | 4.65 | 2.156 | 0.253 | 0.22 |

| Methanol-MIL-100(Fe) | −1.07 | −7.67 | −3.95 | 3.72 | 4.96 | 2.148 | 0.247 | 0.14 |

| Isoporpanol-MIL-100(Fe) | −1.17 | −7.64 | −3.90 | 3.73 | 5.98 | 2.118 | 0.244 | 2.21 |

| CO2-MIL-100(Fe) | −0.41 | −7.91 | −4.32 | 3.58 | 1.66 | 2.445 | 0.117 | 6.53 x 10−10 |

From our calculations, we found a similar adsorption behavior for all gases on both MIL-100(Al) and MIL-100(Fe), as seen in Fig. S3 and Fig. 3 . Thereby, only the results from MIL-100(Fe) will be presented in the main text. We divide the gas adsorptions into two groups, 1. biomarker from a COVID-19 patient (ethyl butyrate, 2-methylpent-2-enal, 1-chloroheptane, nonanal, and 2,4-octadiene) and 2. those from a healthy human (isopropanol, acetone, methanol, ethanol, CO2, and H2O). For the ethyl butyrate adsorption on MIL-100(Fe), O carbonyl is coordinated to the CUS of MIL-100(Fe) with the adsorption energy of −1.17 eV. In the case of 2-methylpent-2-enal and nonanal, they adsorbed vertically. The O atom points toward the metal site with the intermolecular bond distances of 2.13 and 2.19 Å for 2-methylpent-2-enal and nonanal, respectively.

Fig. 3.

The most stable adsorption configurations for (a) Ethyl Butyrate, (b) 2-Methylpent-2-enal, (c) Nonanal, (d) 1-Chloroheptane, (e) 2,4-Octadiene, (f) Water, (g) Acetone, (h) Ethanol, (i) Methanol, (j) Isopropanol and (k) Carbon dioxide on MIL-100(Fe).

We need to confirm if these calculated geometries are consistent with the experimental situation. We compared the calculated IR spectra with the experimental IR spectra taken when the biomarkers were adsorbed on the MIL-100(Fe). The preference for C O binding mode is verified by the FTIR spectrum of 2-methylpent-2-enal on MIL-100(Fe) (Fig. 4b). The additional peak corresponding to the C O stretching of the carbonyl group in 2-methylpent-2-enal is observed at 1683 cm−1, which confirms the existence of the target gas on MIL-100(Fe). In addition, the C O stretching peak of 2-methylpent-2-enal on MIL-100(Fe) is shifted to a lower wavenumber, indicating the interaction between the carbonyl group of 2-methylpent-2-enal and MIL-100(Fe).

To confirm that the Fe is the primary binding site, we looked at the bands related to this metal. We can see that the band of O–Fe–O is redshifted after the adsorption (622 cm−1 shifted to 619 cm−1), suggesting the formation of the Fe–O C in the adsorption process. The Fe–O–Fe stretching band was calculated to be at 652 cm−1, while it was experimentally observed at 709 cm−1. Remarkably, a characteristic absorption peak appears in the experiment at 456 cm−1. Our calculation assigns this peak as corresponding to the Fe–O(=C) stretching vibration, which is at 474 cm−1. A similar trend in IR peak shift is also observed for 2-methylpent-2-enal on MIL-100(Al) (Fig. 4a). Upon adsorption of 1-chlorohaptane on MIL-100(Fe), the molecule takes a tilted geometry pointing its Cl atom to the Fe metal site. In addition, 2,4-octadiene favors a parallel orientation to the MIL-100(Fe) cluster with the diene aligned to the metal site. The presence of 2-methylpent-2-enal in the pores of MIL-100(Fe) is further confirmed by the decreasing of BET surface area from 1553.20 cm2g-1 to 90.20 cm2g-1 after the adsorption process. These results demonstrate that 2-methylpent-2-enal is indeed adsorbed on MIL-100(Fe) by chemical adsorption.

To clarify the selectivity of our proposed sensor, we have considered the adsorption properties of gas molecules found in healthy humans, such as water, acetone, ethanol, methanol, isopropanol, and CO2 on the MIL-100(Fe). The water molecule is adsorbed in the parallel direction. The experimental IR spectrum of water on MIL-100(Fe) exhibits an increase in the board O–H stretching peak signal at around 3086-3402 cm−1 compared with the pristine MOF (Fig. S5b), confirming the presence of H2O in the MOF. Moreover, we confirmed the H2O interaction on MIL-100(Fe) by DFT calculations. The O–H stretching peak of water on MIL-100(Fe) is red-shifted, showing the interaction between water and the MOF. In addition, we found a signature of (H2)O–Fe interaction at the fingerprint region (334 cm−1). Carbon dioxide is tilted with the O atom pointing toward MIL-100(Fe). Moreover, acetone, ethanol, methanol, and isopropanol gases prefer to adsorb in a vertical orientation, where the O atom binds to the Fe atom of MIL-100(Fe) with the FeO bond lengths of 2.14, 2.16, 2.15, and 2.12 Å, respectively. In addition, to mimic a situation where water and 2-methylpent-2-enal coexist, we calculated a mixed gas. Water was systematically added to the 2-methylpent-2-enal on MIL-100(Fe) system (Fig. S5). We observe minor changes in geometries, and the adsorption energies of gases are still greater than 1 eV. This suggests that the addition of H2O gas will only result in minor effects on COVID-19 biomarker detection. Hence, in the presence of interfering gases, our MOF can display remarkable selectivity to 2-methylpent-2-enal, indicating its potential utility as a sensor for detecting COVID-19 biomarkers in exhaled breath.

For effective sensing, the binding between the adsorbent and adsorbate should be strong enough to cause a detectable change in the sensor's material. On the other hand, the binding should be weak enough to recover the sensor function for multiple uses. The calculated E ads of COVID-19 biomarkers are −1.17, −1.08, −1.16, −0.76, and −0.84 eV for ethyl butyrate, 2-methylpent-2-enal, nonanal, 1-chloroheptane, and 2,4-octadiene molecules, respectively, which are strongly adsorbed on MIL-100(Fe). Interestingly, the O-functionalized structures suggest larger adsorption energies in comparison with 1-chrolohaptane (Cl-functionalized molecule) and 2,4-octadiene (an aliphatic hydrocarbon). Moreover, the adsorption properties of the biomarkers in breath exhaled by healthy humans are also investigated to see the selectivity of sensing materials. The E ads of water, acetone, ethanol, methanol, isopropanol, and carbon dioxide are −0.90, −1.02, −1.09, −1.07, −1.17, and −0.41 eV, respectively. These values show a strong interaction between the gas molecule and the sensor. Especially, the O-functionalized gases (acetone, ethanol, and methanol) show high E ads, while CO2 gives a low E ads. The adsorption properties are related to charge transfer and the interaction distances between adsorbed molecules and sensors. Key distances and the change in Mulliken charge are given in Fig. 3 and Table 1. The adsorption distance of ethylbutyrate, 2-methylpent-2-enal, nonanal, 1-chloroheptane, 2,4-octadiene, H2O, acetone, ethanol, methanol, isopropanol, and CO2 on MIL-100(Fe) cluster are 2.12, 2.13, 2.19, 2.70, 2.91, 2.19, 2.14, 2.16, 2.15, 2.12, and 2.44 Å, respectively. In addition, we collect the amount of atomic charge that is transferred between the adsorbed molecules and the MIL-100(Fe) cluster. The charges indicate that the adsorbed molecule donates electrons to MIL-100(Fe). The structural and electronic properties of all biomarkers adsorption on MIL-100(Al) are similar to those on MIL-100(Fe). Moreover, the E ads of biomarkers on MIL-100(Al, Fe) is greater than those reported for the adsorption on pristine BC6N [57] and graphene sheets [[58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63]]. Therefore, MIL-100(Al) or MIL-100(Fe) may provide better performance toward gas sensing than the 2D materials reported previously.

Reusability of the sensor is evaluated by the recovery time (τ) of a sensing material after gas exposure, which can be calculated based on the transition state theory as follows [64]:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Where is the rate of desorption. The desorption energy , and are the electronic and vibrational partition function of the molecule A, ( is the vibrational partition function of the bare surface, is the sticking probability per active site which we assume as 1, is the mass of the desorbing molecule, are the rotational temperature for the nonlinear molecule, and is the concentration of reactive site per unit area [64,65]. Here, we will use two reactive sites per unit cell; thus, we have = . T is the temperature (K), kB is the Boltzmann constant and ν 0 is pre-exponential factor. Our calculated recovery time on the MIL-100(Fe) systems is listed in Table 1 while those at different conditions are given in Table S4. Taking equation (3), the calculated pre-exponential factor (ν 0 = 2.61x1014 s−1) at T = 398.15 K results in a short recovery time for MIL-100(Fe) sensor which are 2.56, 0.19, 1.85, 1.49 x 10−5 and 1.84 x 10−4 s for ethylbutyrate, 2-methylpent-2-enal, nonanal, 1-chloroheptane, and 2,4-octadiene, respectively. The short τ values propose the reusability of this gas sensor.

Apart from the proper E ads of gas on the sensor, the sensor's electrical properties must be changed when interacting with the analyte. The band gap energies are given in Table 1. To elucidate the sensor performance as well as selectivity of the materials, we calculated the sensing response (SR) of the MIL-100(Al, Fe) to the biomarkers and the common exhaled gases. From equation (4), the resistivity and the electrical conductance (EC) of the MIL-100 (Al,Fe) can be tuned by their electronic properties [66]:

| (4) |

here A, T and kB are a constant, temperature (K), and the Boltzmann constant, respectively. The SR was calculated as follows:

| (5) |

where R2 and R1 signify the resistivity of the gas/MIL-100 and the pristine MIL-100, respectively, There is an inverse relationship between EC and resistivity. Therefore, we can write:

| (6) |

Here, EC1 and EC2 refer the EC of the MIL-100 after and before gas adsorption, respectively. ΔEg signifies the difference between Eg of the gas/MIL-100 and the pristine MIL-100. For MIL-100(Fe), the sensing response for ethylbutyrate, 2-methylpent-2-enal, nonanal, 1-chloroheptane, 2,4-octadiene, H2O, acetone, ethanol, methanol, isopropanol, and CO2 are calculated at 298.15 K, as can be seen in Fig. 5 . Previous DFT calculations reported that ethyl butyrate could give a good response to metal-doped carbon materials [18,19,29], while 2-methylpent-2-enal and 2,4-octadiene biomarkers have not been investigated before. In our work, we found that MIL-100(Al,Fe) are highly sensitive to 2-methylpent-2-enal and 2,4-octadiene much more than ethylbutyrate.

Fig. 5.

The calculated sensing response of the system after biomarker VOCs adsorption with reference to the bare MIL-100 (Al, Fe).

Compared to the common exhaled gases that interfere with our detection, our proposed sensor shows excellent sensitivity toward COVID-19 biomarkers with the SR values are 7.44 x 105 and 9 x 107 for 2-methylpent-2-enal, and 2,4-octadiene, respectively. The SR values are negligible for H2O, CO2, acetone, ethanol, methanol, and isopropanol which are less than 6. For the gases reversibly, it is demonstrated that 2-methylpent-2-enal and 2,4-octadiene on MIL-100(Fe) show the high sensitivity and the short recovery time. We also discovered that MIL-100(Fe) has a better sensor property than MIL-100(Al). From these calculations, we suggest that MIL-100(Fe) is a promising candidate porous material sensor for the identification of the COVID-19 biomarker (2-methylpent-2-enal and 2,4-octadiene).

3.4. Experimental results

MIL-100(Al) was synthesized from aluminium nitrate nonahydrate and 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid in the water, while the metal precursor was changed to iron chloride hexahydrate for the synthesis of MIL-100(Fe), see Fig. 1. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of both MIL-100(Al) and MIL-100(Fe) match well with the simulated pattern of MIL-100 topology [45], suggesting the same topology in both samples. The particle size of MIL-100(Al) and MIL-100(Fe) are found to be 0.37 μm owing to the fast crystal growth process in microwave syntheses, as demonstrated in Fig. S8. The Brunauer, Emmett and Teller (BET) surface area of MIL-100(Al) and MIL-100(Fe), which were estimated from the N2 adsorption isotherms, are 1164 m2g-1 and 1553 m2g-1, respectively (see Table S4 for details). The BET surface area values of both samples are in good agreement with the reported values, suggesting the successful syntheses of MIL-100(Al) and MIL-100(Fe) [67]. It is found that the crystal structures of MIL-100 remain intact after 3-cycle tests, as indicated by the XRD patterns shown in Fig. S10. N2 adsorption experiments were conducted at 77K to evaluate the porosity, which is an essential property of MOF materials for sensing COVID-19 biomarkers, Fig. S11. Both MIL-100(Al) and MIL-100(Fe) provide type I adsorption isotherms corresponding to microporous solids. It should be noted that hysteresis is not observed in MIL-100(Al) and MIL-100(Fe) due to the aggregation of small particles [67].

Powders of MIL-100(Al) and MIL-100(Fe) were further prepared as 5 mm pellets for VOC adsorption studies. VOC of the targeted biomarker was generated in the closed container and allowed to diffuse to MOF pellets in gas phases. Unfortunately, the most predominant biomarker, 2,4-octadiene, were not commercially available. Thus, only 2-methylpent-2-enal, ethyl butyrate, 1-chloroheptane and nonanal were studied in the experimental part. The common exhaled breath VOCs (ethanol, methanol, isopropanol, acetone, and water) are comparatively studied. The VOCs trapped in the pore of MOF after adsorption processes are investigated by mass spectroscopy (Table 2 ). It is found that all eight VOCs could adsorb in the pore of MIL-100, which is consistent with the theoretical studies discussed above. However, the amounts of each VOC adsorbed in MIL-100 are different, suggesting the different binding ability of VOC in the pore of MIL-100. Following the calculation results, the sensing performance of MIL-100(Al, Fe) sensors was studied by UV–Vis spectroscopy to confirm the calculated band gap changes upon the adsorption of VOCs (Fig. 6 , Figs. S14–15 and Table S7). Although all VOCs could adsorb on MIL-100(Al, Fe), a significant band gap change is only observed in a few VOCs. In most cases, the band gap of MIL-100 does not vary upon the adsorption of VOCs. According to Eq. (6), we have calculated SR to preliminary confirm the sensitivitiy of the proposed sensor. Note that the SR is minor for VOCs exhaled from healthy humans, such as alcohol, acetone, and water. But, the adsorption of 2-methylpent-2-enal, a COVID-19 biomarker, shows the outstanding SR at 32.63 for MIL-100(Fe). On the other hand, other VOCs result in 6 folds less than that of 2-methylpent-2-enal. This indicates the selective sensing of 2-methylpent-2-enal biomarker in MIL-100(Fe). We expected to see a better performance sensing for 2,4-octadiene biomarker if it is commercially available. In addition, the sensing signal can be increased by applying techniques such as surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) [15].

Table 2.

Mass spectrometric (MS) measurements after biomarker VOCs adsorption on MIL-100 (Al, Fe).

| VOCs | Molecular mass | [M+H]+ |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MIL-100 (Al) | MIL-100(Fe) | ||

| Acetone | 58.04 | 59.04 | 59.04 |

| Isopropanol | 60.06 | 61.05 | 61.06 |

| Ethyl Butyrate | 116.08 | 117.11 | 117.11 |

| 2-Methylpent-2-enal | 98.07 | 99.08 | 99.08 |

| 1-Choroheptane | 134.65 | 135.08 | 135.07 |

| Nonanal | 142.14 | 143.16 | 143.15 |

Fig. 6.

Experimental study of sensing response of the system after biomarker VOCs adsorption with reference to the solitary MIL-100 (Al, Fe) by using the Tauc plot method.

To evaluate the potential of MIL-100 for electrochemical sensing, we have studied the change in resistivity of MIL-100(Al, Fe) upon exposure to 2-methylpent-2-enal. The resistivity of all samples was analyzed from impedance data at room temperature (298 K). Changes in impedance after 2-methylpent-2-enal adsorption were evaluated from the Nyquist plot (Table S6), which demonstrated preliminary evidence that MIL-100(Al, Fe) can be used as a highly sensitive sensor for 2-methylpent-2-enal. Furthermore, we also studied the reusability of MIL-100 for biomarker sensing. A sample after VOC adsorption was reactivated by placing it in the vacuum oven to evacuate the VOCs from the MOF structure. The VOC adsorption process is repeated three times to ensure the reusability of MOF materials. Moreover, we also observed the same trend of sensing response in all types of VOCs in the 2nd and 3rd cycle tests.

4. Conclusions

We investigated the possible use of MIL-100(Al, Fe) as sensing materials for COVID-19 biomarkers detection. The GCMC simulations revealed that the Fe atoms of MIL-100(Fe) are the preferential adsorption sites for 2-methylpent-2-enal. The adsorption mechanism of the five dominant VOCs components from exhaled breath of COVID-19 patients, ethyl butyrate, 2-methylpent-2-enal, 1-chloroheptane, nonanal, and 2,4-octadiene, on MIL-100(Al,Fe) were investigated by mean of first-principles DFT calculations. The adsorption properties of interfering gases such as H2O, acetone, ethanol, methanol, isopropanol, and CO2 were also considered to evaluate the sensitivity of MIL-100(Al,Fe) sensors. The adsorption configuration, adsorption energy, band gap, sensing response, recovery time, and electronic properties of MIL-100(Al,Fe) before and after adsorption with VOCs are also determined. In addition, we confirmed the calculated geometries by comparing the theoretical and experimental IR spectra of VOCs adsorbed in the MOF. It is found that MIL-100(Fe) has higher performance than MIL-100(Al) and it demonstrates high sensitivity to 2-methylpent-2-enal and 2,4-octadiene in the presence of interference gases. The calculated sensing response of MIL-100(Fe) to 2-methylpent-2-enal is exceptionally high as 7.44 x 105 while those for interference gases are less than 6. Moreover, the recovery time of MIL-100(Fe) for 2-methylpent-2-enal is 1.84 x 10−4 s which is beneficial as a reusable sensor. Therefore, we predict that it has potential use as a sensor for detecting COVID-19 biomarkers in exhaled breath. The discovery in this work is useful for further developing rapid and efficient sensors for the detection of COVID-19 to control the disease outbreak.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nuttapon Yodsin: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Kunlanat Sriphumrat: Writing – original draft, Investigation. Kanokwan Kongpatpanich: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. Supawadee Namuangruk: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Software, Resources, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Supawadee Namuangruk reports financial support was provided by National Nanotechnology Center and National Research Council of Thailand. Kanokwan Kongpatpanich reports financial support was provided by the Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by National Nanotechnology Center (N41A640101), National Research Council of Thailand (N41A640101) and the Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation (RGNS 63-251). N. Y. thanks to the Human Resource Development in Science Project Science Achievement Scholarship of Thailand (SAST). We thank the NSTDA Supercomputer center (ThaiSC) for its computational resources.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2022.112187.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Crozier A., Rajan S., Buchan I., McKee M. Put to the test: use of rapid testing technologies for covid-19. BMJ. 2021:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pokhrel P., Hu C., Mao H. Detecting the coronavirus (COVID-19) ACS Sens. 2020;5:2283–2296. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.0c01153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samson R., Navale G.R., Dharne M.S. Biosensors: Frontiers in rapid detection of COVID-19. 3 Biotech. 2020;10:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02369-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribeiro B.V., Cordeiro T.A.R., e Freitas G.R.O., Ferreira L.F., Franco D.L. Talanta Open; 2020. Biosensors for the Detection of Respiratory Viruses: A Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenske J.D., Paulson S.E. Human breath emissions of VOCs. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 1999;49:594–598. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1999.10463831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips M., Herrera J., Krishnan S., Zain M., Greenberg J., Cataneo R.N. Variation in volatile organic compounds in the breath of normal humans. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1999;729:75–88. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(99)00127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miekisch W., Schubert J.K., Noeldge-Schomburg G.F. Diagnostic potential of breath analysis—focus on volatile organic compounds. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2004;347:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukhopadhyay R. ACS Publications; 2004. Don't Waste Your Breath. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babusikova E., Jesenak M., Durdik P., Dobrota D., Banovcin P. Exhaled carbon monoxide as a new marker of respiratory diseases in children. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2008;59:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pleil J.D. Role of exhaled breath biomarkers in environmental health science. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part A B. 2008;11:613–629. doi: 10.1080/10937400701724329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popov T.A. Human exhaled breath analysis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim K.-H., Jahan S.A., Kabir E. A review of breath analysis for diagnosis of human health. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2012;33:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amann A., Poupart G., Telser S., Ledochowski M., Schmid A., Mechtcheriakov S. Applications of breath gas analysis in medicine. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004;239:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tung T.T., Tran M.T., Feller J.-F., Castro M., Van Ngo T., Hassan K., Nine M.J., Losic D. Graphene and metal organic frameworks (MOFs) hybridization for tunable chemoresistive sensors for detection of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) biomarkers. Carbon. 2020;159:333–344. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu J.-H., Zhong Z., Xie D., Guo Y.-J., Kong D.-X., Zhao Z.-X., Zhao Z.-X., Li M. SERS-active MIL-100(Fe) sensory array for ultrasensitive and multiplex detection of VOCs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:20489–20498. doi: 10.1002/anie.202002720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salimi M., Hosseini S.M.R.M. Smartphone-based detection of lung cancer-related volatile organic compounds (VOCs) using rapid synthesized ZnO nanosheet. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2021;344 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen H., Qi X., Ma J., Zhang C., Feng H., Yao M. Breath-borne VOC biomarkers for COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.21.20136523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh P., Sohi P.A., Kahrizi M. In silico design and analysis of Pt functionalized graphene-based FET sensor for COVID-19 biomarkers: a DFT coupled FEM study. Phys. E Low-dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2022;135 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahimi R., Solimannejad M. B3O3 monolayer with dual application in sensing of COVID-19 biomarkers and drug delivery for treatment purposes: a periodic DFT study. J. Mol. Liq. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giovannini G., Haick H., Garoli D. Detecting COVID-19 from breath: a game changer for a big challenge. ACS Sens. 2021;6:1408–1417. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.1c00312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grassin-Delyle S., Roquencourt C., Moine P., Saffroy G., Carn S., Heming N., Fleuriet J., Salvator H., Naline E., Couderc L.-J., Devillier P., Thévenot E.A., Annane D. Metabolomics of exhaled breath in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a pilot study. EBioMedicine. 2021;63 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subali A.D., Wiyono L., Yusuf M., Zaky M.F.A. The potential of volatile organic compounds-based breath analysis for COVID-19 screening: a systematic review & meta-analysis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022;102 doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2021.115589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berna A.Z., Akaho E.H., Harris R.M., Congdon M., Korn E., Neher S., M'Farrej M., Burns J., Odom John A.R. Reproducible breath metabolite changes in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021;7:2596–2603. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grassin-Delyle S., Roquencourt C., Moine P., Saffroy G., Carn S., Heming N., Fleuriet J., Salvator H., Naline E., Couderc L.-J., Devillier P., Thévenot E.A., Annane D. Metabolomics of exhaled breath in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a pilot study. EBioMedicine. 2021;63 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruszkiewicz D.M., Sanders D., O'Brien R., Hempel F., Reed M.J., Riepe A.C., Bailie K., Brodrick E., Darnley K., Ellerkmann R., Mueller O., Skarysz A., Truss M., Wortelmann T., Yordanov S., Thomas C.L.P., Schaaf B., Eddleston M. Diagnosis of COVID-19 by analysis of breath with gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry - a feasibility study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shan B., Broza Y.Y., Li W., Wang Y., Wu S., Liu Z., Wang J., Gui S., Wang L., Zhang Z., Liu W., Zhou S., Jin W., Zhang Q., Hu D., Lin L., Zhang Q., Li W., Wang J., Liu H., Pan Y., Haick H. Multiplexed nanomaterial-based sensor array for detection of COVID-19 in exhaled breath. ACS Nano. 2020;14:12125–12132. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c05657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giovannini G., Haick H., Garoli D. Detecting COVID-19 from breath: a game changer for a big challenge. ACS Sens. 2021;6:1408–1417. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.1c00312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hakim M., Broza Y.Y., Barash O., Peled N., Phillips M., Amann A., Haick H. Volatile organic compounds of lung cancer and possible biochemical pathways. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:5949–5966. doi: 10.1021/cr300174a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia S., Luo X. Analysis of 2D nanomaterial BC 3 for COVID-19 biomarker ethyl butyrate sensor. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2021;9:9221–9229. doi: 10.1039/d1tb00897h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suh M.P., Park H.J., Prasad T.K., Lim D.-W. Hydrogen storage in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:782–835. doi: 10.1021/cr200274s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadakiyo M., Yamada T., Kitagawa H. Rational designs for highly proton-conductive metal− organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9906–9907. doi: 10.1021/ja9040016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrusseng D., Aguado S., Pinel C. Metal–organic frameworks: opportunities for catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:7502–7513. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horcajada P., Serre C., Vallet‐Regí M., Sebban M., Taulelle F., Férey G. Metal–organic frameworks as efficient materials for drug delivery. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:6120–6124. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu Q.-Y., Tan Z., Liao X.-W., Wang C. Recent advances in nanoscale metal-organic frameworks biosensors for detection of biomarkers. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021;33:22–32. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma N., Horike S. Metal–organic network-forming glasses. Chem. Rev. 2022;122:4163–4203. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang M., Feng G., Song Z., Zhou Y.-P., Chao H.-Y., Yuan D., Tan T.T.Y., Guo Z., Hu Z., Tang B.Z., Liu B., Zhao D. Two-Dimensional metal–organic framework with wide channels and responsive turn-on fluorescence for the chemical sensing of volatile organic compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:7241–7244. doi: 10.1021/ja502643p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Férey G., Serre C., Mellot-Draznieks C., Millange F., Surblé S., Dutour J., Margiolaki I. A hybrid solid with giant pores prepared by a combination of targeted chemistry, simulation, and powder diffraction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:6296–6301. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyu P., Maurin G. Mechanistic insight into the catalytic NO oxidation by the MIL-100 MOF platform: toward the prediction of more efficient catalysts. ACS Catal. 2020;10:9445–9450. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang D., Wang M., Li Z. Fe-based metal–organic frameworks for highly selective photocatalytic benzene hydroxylation to phenol. ACS Catal. 2015;5:6852–6857. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dhakshinamoorthy A., Alvaro M., Garcia H. Metal organic frameworks as efficient heterogeneous catalysts for the oxidation of benzylic compounds with t-butylhydroperoxide. J. Catal. 2009;267:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berna A.Z., Akaho E.H., Harris R.M., Congdon M., Korn E., Neher S., M'Farrej M., Burns J., John A.R.O. Reproducible breath metabolite changes in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection. medRxiv. 2021:2020. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00248. 2012.2004.20230755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plimpton S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995;117:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rappe A.K., Casewit C.J., Colwell K.S., Goddard W.A., Skiff W.M. UFF, a full periodic table force field for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10024–10035. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyd P.G., Moosavi S.M., Witman M., Smit B. Force-field prediction of materials properties in metal-organic frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017;8:357–363. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b02532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horcajada P., Surblé S., Serre C., Hong D.-Y., Seo Y.-K., Chang J.-S., Grenèche J.-M., Margiolaki I., Férey G. Synthesis and catalytic properties of MIL-100 (Fe), an iron (III) carboxylate with large pores. Chem. Commun. 2007:2820–2822. doi: 10.1039/b704325b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akiyama G., Matsuda R., Kitagawa S. Highly porous and stable coordination polymers as water sorption materials. Chem. Lett. 2010;39:360–361. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vosko S.H., Wilk L., Nusair M. Accurate spin-dependent electron liquid correlation energies for local spin density calculations: a critical analysis. Can. J. Phys. 1980;58:1200–1211. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becke A. Phys. Rev. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Perdew J.P. Phys. Rev. B. 1986;33:8822–8824. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Odelius M., Bernasconi M., Parrinello M. Two dimensional ice adsorbed on mica surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;78:2855. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grimme S., Antony J., Ehrlich S., Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;132 doi: 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schäfer A., Huber C., Ahlrichs R. Fully optimized contracted Gaussian basis sets of triple zeta valence quality for atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 1994;100:5829–5835. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dolg M., Wedig U., Stoll H., Preuss H. Energy‐adjusted abinitio pseudopotentials for the first row transition elements. J. Chem. Phys. 1987;86:866–872. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mali G., Mazaj M., Arčon I., Hanžel D., Arčon D., Jagličić Z. Unraveling the arrangement of Al and Fe within the framework explains the magnetism of mixed-metal MIL-100(Al,Fe) J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019;10:1464–1470. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horcajada P., Surblé S., Serre C., Hong D.-Y., Seo Y.-K., Chang J.-S., Grenèche J.-M., Margiolaki I., Férey G. Synthesis and catalytic properties of MIL-100(Fe), an iron(iii) carboxylate with large pores. Chem. Commun. 2007:2820–2822. doi: 10.1039/b704325b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halls M.D., Tripp C.P., Schlegel H.B. Structure and infrared (IR) assignments for the OLED material: N, N′-diphenyl-N, N′-bis (1-naphthyl)-1, 1′-biphenyl-4, 4 ″-diamine (NPB) Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001;3:2131–2136. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mulliken R. Electronic population analysis on LCAO–MO molecular wave functions. II. Overlap populations, bond orders, and covalent bond energies. J. Chem. Phys. 1955;23:1841–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aghaei S.M., Aasi A., Farhangdoust S., Panchapakesan B. Graphene-like BC6N nanosheets are potential candidates for detection of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in human breath: a DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021;536 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schröder E. Methanol adsorption on graphene. J. Nanomater. 2013:2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lazar P., Karlický F., Jurečka P., Kocman M., Otyepková E., Šafářová K., Otyepka M. Adsorption of small organic molecules on graphene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:6372–6377. doi: 10.1021/ja403162r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shokuhi Rad A., Pouralijan Foukolaei V. Density functional study of Al-doped graphene nanostructure towards adsorption of CO, CO2 and H2O. Synth. Met. 2015;210:171–178. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ou P., Song P., Liu X., Song J. Superior sensing properties of black phosphorus as gas sensors: a case study on the volatile organic compounds. Adv. Thoer. Simulat. 2019;2 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun S., Hussain T., Zhang W., Karton A. Blue phosphorene monolayers as potential nano sensors for volatile organic compounds under point defects. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019;486:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tian X.-Q., Liu L., Wang X.-R., Wei Y.-D., Gu J., Du Y., Yakobson B.I. Engineering of the interactions of volatile organic compounds with MoS2. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2017;5:1463–1470. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pitt I.G., Gilbert R.G., Ryan K.R. Application of transition-state theory to gas-surface reactions: barrierless adsorption on clean surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:13001–13010. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang C.-C., Wu J.-Y., Jiang J.-C. Microkinetic simulation of temperature-programmed desorption. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013;117:6136–6142. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamazoe N., Shimanoe K. New perspectives of gas sensor technology. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2009;138:100–107. [Google Scholar]

- 67.García Márquez A., Demessence A., Platero‐Prats A.E., Heurtaux D., Horcajada P., Serre C., Chang J.S., Férey G., de la Peña‐O'Shea V.A., Boissière C. Green microwave synthesis of MIL‐100 (Al, Cr, Fe) nanoparticles for thin‐film elaboration. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012:5165–5174. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.