Abstract

The membrane-bound H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase system of the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina mazei Gö1 catalyzed the H2-dependent reduction of 2-hydroxyphenazine and the dihydro-2-hydroxyphenazine-dependent reduction of the heterodisulfide of HS-CoM and HS-CoB (CoM-S-S-CoB). Washed inverted vesicles of this organism were found to couple both processes with the transfer of protons across the cytoplasmic membrane. The maximal H+/2e− ratio was 0.9 for each reaction. The electrochemical proton gradient (ΔμH+) thereby generated was shown to drive ATP synthesis from ADP plus Pi, exhibiting stoichiometries of 0.25 ATP synthesized per two electrons transported for both partial reactions. ATP synthesis and the generation of ΔμH+ were abolished by the uncoupler 3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzylidenemalononitrile (SF 6847). The ATP synthase inhibitor N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide did not affect H+ translocation but led to an almost complete inhibition of ATP synthesis and decreased the electron transport rates. The latter effect was relieved by the addition of SF 6847. Thus, the energy-conserving systems showed a stringent coupling which resembles the phenomenon of respiratory control. The results indicate that two different proton-translocating segments are present in the H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase system; the first involves the 2-hydroxyphenazine-dependent hydrogenase, and the second involves the heterodisulfide reductase.

Methanosarcina mazei Gö1 belongs to the methylotrophic methanogens of the order Methanosarcinales and can grow on H2 plus CO2, methanol, methylamines, and acetate. The pathways of methanogenesis from these substrates have been analyzed in detail in recent years (8, 11, 29). All substrates are converted to methyl-S-CoM (2-methylthioethanesulfonate), either by reduction of CO2 or by demethylation of methanol and acetate. Methane is formed from methyl-S-CoM by the catalytic activity of the methyl-S-CoM reductase, which uses HS-CoB (7-mercaptoheptanoylthreonine phosphate) as electron donor. The reaction leads to the production of a heterodisulfide (CoM-S-S-CoB) from HS-CoM and HS-CoB, which is the terminal electron acceptor of the membrane-bound electron transport systems of M. mazei Gö1. The source of reducing equivalents necessary for the reduction of CoM-S-S-CoB depends on the growth substrate. If molecular hydrogen is present, a membrane-bound F420 [(N-l-lactyl-γ-l-glutamyl)-l-glutamic acid phosphodiester of 7,8 didemethyl-8-hydroxy-5-deazariboflavin-5′-phosphate]-nonreducing hydrogenase channels electrons via b-type cytochromes to the heterodisulfide reductase which reduces the terminal electron acceptor (6, 13). This electron transport system, referred to as H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase, is coupled to proton translocation across the cytoplasmic membrane (8). When cells are grown on methanol, part of the methyl groups are oxidized to CO2 and reducing equivalents are transferred to coenzyme F420. In Methanosarcina strains, reduced F420 (F420H2) is reoxidized by the membrane-bound F420H2 dehydrogenase which is part of the F420H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase (7). Parallel to the H2-dependent system, electrons are channeled to the heterodisulfide reductase, resulting in the reduction of CoM-S-S-CoB and in the formation of an electrochemical proton gradient. It was shown that the resulting ΔμH+ (transmembrane electrochemical gradient of H+) is the driving force for ATP synthesis from ADP plus Pi as catalyzed by an A1A0-type ATP synthase (25). Since other components of the systems were unknown at that time, only the overall electron transport reaction could be analyzed. Recently, a new redox-active component was isolated from the cytoplasmic membrane of strain Gö1 and named methanophenazine (1). Furthermore, it was shown that key enzymes of the membrane-bound electron transfer systems were able to interact with 2-hydroxyphenazine (2-OH-phenazine), which is a water-soluble analogue of methanophenazine (2). By using 2-OH-phenazine, the process of electron transfer from molecular hydrogen to the heterodisulfide can be divided into two partial reactions (6):

|

1 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

In this report, we show that both reactions are coupled to proton translocation and that the resulting electrochemical proton gradient is used for ATP synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of cells and preparation of washed vesicles.

M. mazei Gö1 (DSM 3647) was grown in 1-liter glass bottles or, for mass culturing, in 20-liter carboys on 150 mM methanol in a medium described previously (7). Washed vesicles of strain Gö1 (21) were prepared as described by Deppenmeier et al. (7) except that the final protein concentration was 10 to 15 mg/ml.

Assay conditions.

Proton translocation was monitored by a pH electrode (model 8103 Ross; Orion Research, Küsnacht, Switzerland) which was inserted into a glass vessel (11 ml) from the top through a rubber stopper. The electrode was connected with an Orion model EA 920 pH meter and a chart recorder. After gassing with H2 or N2, the vessel was filled with 3 ml of 40 mM potassium thiocyanate solution containing 0.5 M sucrose, 1 mg of resazurine per liter, and 10 mM dithioerythritol, followed by the addition of 50 to 80 μl of washed vesicles (1 to 1.4 mg of protein/assay). The medium was continuously stirred, and the pH was adjusted to 6.8 to 6.9. Additions were made with a microliter syringe from the side arm. Proton uptake coupled to reaction 1 was followed by the addition of 4.5 to 20 nmol of 2-OH-phenazine (4.5 or 20 mM stock solution in ethanol) under an atmosphere of molecular hydrogen. To determine the H+ transfer in the course of reaction 2, the vessel was gassed with N2 and 240 nmol of CoM-S-S-CoB was added. The reaction was started by the addition of 4.5 to 20 nmol of dihydro-2-OH-phenazine. After completion of the experiments, the pH changes were calibrated with standard solutions of HCl or NaOH. CoB-S-S-CoM was synthesized by the method of Noll et al. (23) and Kamlage and Blaut (15). 2-OH-phenazine was prepared as described by Abken et al. (1) and was reduced as described by Bäumer et al. (2).

Electron transfer reactions and ATP synthesis were investigated in 1.5-ml glass cuvettes filled with 0.6 ml of 40 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7) containing 20 mM MgSO4, 0.5 M sucrose, 10 mM dithioerythritol, and 1 mg of resazurin per liter (buffer A) under anaerobic conditions; 10 μl of ADP (10 mM stock solution) and 10 μl of AMP (100 mM stock solution) were added. AMP inhibits the membrane-bound adenylate kinase of M. mazei Gö1 (8). This enzyme activity leads to an ADP disproportionation which would otherwise interfere with the electron transfer-driven ATP synthesis. Additions were made as indicated. 2-OH-phenazine, dihydro-2-OH-phenazine, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD), and 3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzylidenemalononitrile (SF 6847) were added as ethanolic solutions. The controls received ethanol only. To determine the ATP concentration, 1- to 2-μl aliquots were withdrawn with a syringe and analyzed by the luciferin-luciferase assay (16) in combination with a biocounter M1500 (Lumac, Landgraaf, The Netherlands). Redox reactions with 2-OH-phenazine and dihydro-2-OH-phenazine were monitored photometrically at 475 nm (ɛ = 2.5 mM−1 cm−1) under atmospheres of H2 and N2, respectively.

RESULTS

Proton translocation due to H2-dependent heterodisulfide reduction.

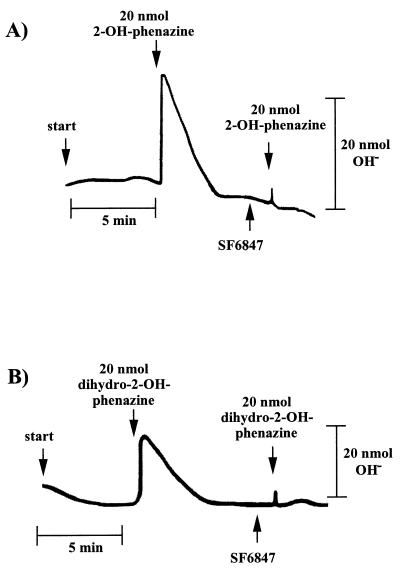

Washed inverted vesicles from M. mazei Gö1 were tested for the ability to couple electron transfer with the translocation of protons across the cytoplasmic membrane. Therefore, concentrated vesicles were diluted with a sucrose-thiocyanide solution under an atmosphere of molecular hydrogen and were pulsed with 2-OH-phenazine as shown in Fig. 1A. When the electron acceptor was added, a short period of alkalinization of the medium which is due to a rapid proton movement into the lumen of the inverted vesicles was monitored. In the second phase, a reacidification was observed until a stable pH value was reached again. It is thought that the consumption of 2-OH-phenazine is responsible for this effect. The energy-conserving electron transport comes to an end, leading to a decay of the generated ΔμH+ by passive diffusion of protons from the lumen of the inverted vesicles to the medium. After calibration of the system, the extent of reversible alkalinization was calculated, resulting in an average ratio of 0.9 protons translocated per 2-OH-phenazine reduced (Table 1). No alkalinization was observed when 2-OH-phenazine was replaced by ethanol (Table 1) or when the reaction was performed under an atmosphere of molecular nitrogen (not shown), indicating that proton transfer was specifically coupled to the H2-dependent 2-OH-phenazine reduction. The addition of the protonophore SF 6847 led to a complete inhibition of measurable proton movement (Fig. 1A). In the presence of this proton-conducting agent, the membrane becomes specifically permeable to protons and can no longer sustain a proton potential. H+ translocation was not affected by DCCD up to a concentration of 250 nmol/mg of protein (Table 1), which was sufficient to inhibit ATP synthesis (Fig. 2). Since DCCD inhibits the catalytic activity of the A1A0-type ATP synthase of M. mazei Gö1 (3), this enzyme was not responsible for proton translocation via ATP hydrolysis.

FIG. 1.

Proton uptake by washed inverted vesicles from M. mazei Gö1. The experiments were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The amount of translocated protons was calculated from the difference between maximal alkalinization and the final baseline after reacidification. The reaction was started by pulses of 2-OH-phenazine or dihydro-2-OH-phenazine as indicated. SF 6847 was added as an ethanolic solution to a final concentration of 15 nmol/mg of protein. (A) H2-dependent reduction of 2-OH-phenazine under an atmosphere of molecular hydrogen; (B) dihydro-2-OH-phenazine-dependent reduction of CoM-S-S-CoB under an atmosphere of molecular nitrogen.

TABLE 1.

Proton translocation by washed inverted vesicles of M. mazei Gö1

| Substrate(s) | Addition | H+/2e− ratioa |

|---|---|---|

| H2 + CoB-S-S-CoM | None | 2.0 |

| H2 + 2-OH-phenazine | None | 0.9 |

| H2 + 2-OH-phenazine | DCCD | 0.9 |

| H2 | Ethanol | <0.1 |

| Dihydro-2-OH-phenazine + CoM-S-S-CoB | None | 0.9 |

| Dihydro-2-OH-phenazine + CoM-S-S-CoB | DCCD | 0.9 |

| CoM-S-S-CoB | 2-OH-phenazine | <0.1 |

| CoM-S-S-CoB | Ethanol | <0.1 |

Each value represents an average of at least 10 determinations.

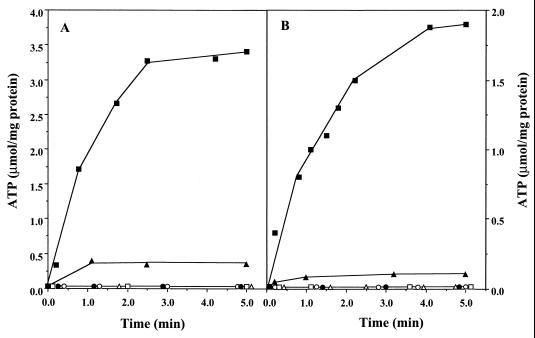

FIG. 2.

Redox-driven ATP synthesis as catalyzed by washed inverted vesicles from M. mazei Gö1. The experiments were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The concentrations of ADP, SF 6847, and DCCD were 0.16 mM, 25 μM, and 250 nmol/mg of protein, respectively. (A) ATP synthesis in the course of H2-dependent-2-OH-phenazine reduction. The glass cuvette was gassed with H2 and contained 600 μl of buffer A, 1.6 mM AMP, and 125 μM 2-OH-phenazine. The reaction was started by the addition of washed vesicles (14 μg of protein). The following additions were made: ADP (■), ADP and SF 6847 (▵), ADP and DCCD (▴), ADP, SF 6847, and DCCD (●), ADP under N2 (○). □, ADP omitted. (B) ATP synthesis coupled to dihydro-2-OH-phenazine-dependent heterodisulfide reduction. Details of the experiment and symbols are as described for panel A except that (i) the reaction mixture contained dihydro-2-OH-phenazine (instead of 2-OH-phenazine) and 240 nmol of CoM-S-S-CoB and (ii) open circles represent assays with ADP added and CoM-S-S-CoB omitted. The atmosphere was N2.

Interestingly, reaction 2 of the H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase system was also able to generate a proton gradient. As evident from Fig. 1B, the addition of dihydro-2-OH-phenazine resulted in the transfer of protons into the lumen of the inverted vesicles when incubated in the presence of CoM-S-S-CoB under an atmosphere of nitrogen. A maximal stoichiometry of 0.9 H+/2e− was determined (Table 1). The addition of oxidized 2-OH-phenazine or ethanol instead of dihydro-2-OH-phenazine prevented proton translocation (Table 1), indicating that the latter process is strictly coupled with the electron transport from reduced phenazine to CoM-S-S-CoB in washed inverted vesicles of M. mazei Gö1. Again, the electron transfer-dependent formation of a proton gradient was abolished when the uncoupler SF 6847 was present in the reaction mixture (Fig. 1B). As is evident, the H+/2e− stoichiometries of the partial reactions summed to 1.8, which is in the same range as the coupling efficiency of the electron transport from H2 to heterodisulfide (Table 1) (8). These results indicate that strain Gö1 possesses two different proton-translocating segments in the H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase system.

Coupling of electron transport and ATP synthesis.

It was previously shown that the H2-dependent heterodisulfide reduction was coupled to ATP synthesis (8). The question arose as to whether ATP formation could also be observed in the course of the phenazine-dependent reactions, both of which were coupled to the generation of an electrochemical proton gradient (Fig. 1). Under an atmosphere of molecular hydrogen, washed vesicles catalyzed the 2-OH-phenazine reduction with an initial rate of 6.0 μmol min−1 mg of protein−1 (Table 2). After 1 min, the rate slowly decreased due to the depletion of 2-OH-phenazine. The reaction was coupled to the phosphorylation of ADP, as indicated by a rapid increase of the ATP concentration upon start of the reaction (Fig. 2A). The estimated value for the first minute was 1.5 μmol of ATP min−1 mg of protein−1, resulting in a ratio of 0.25 mol of ATP formed per mol of OH-phenazine reduced. In the presence of the ATP synthase inhibitor DCCD, the phosphorylation of ADP was strongly inhibited (Fig. 2A) and 2-OH-phenazine reduction slowed to 4.8 U/mg of protein (Table 2). The latter effect was also observed when ADP was omitted. Addition of the uncoupler SF 6847 to H2-metabolizing vesicles in the presence of DCCD or in the absence of ADP led to an increase of the phenazine reduction rate of up to 95 or 97%, respectively, of the control rate (Table 2). Furthermore, SF 6847 abolished ATP synthesis (Fig. 2A) due to the decay of ΔμH+. No ATP was formed when ADP was omitted (Fig. 2A), indicating that the latter nucleotide was not present in washed inverted vesicles.

TABLE 2.

Effects of ADP, DCCD, and SF 6847 on electron transport rates

| Addition(s) | Electron transfer (μmol min−1 mg of protein−1) from:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| H2 to 2-OH-phenazine | Dihydro-2-OH-Phenazine to CoM-S-S-CoB | |

| ADP | 6.0 | 2.4 |

| None | 3.0 | 1.2 |

| SF | 5.8 | 2.8 |

| SF + ADP | 6.1 | 2.9 |

| DCCD + ADP | 4.8 | 1.1 |

| DCCD + SF + ADP | 5.7 | 2.7 |

When the electron transfer from dihydro-2-OH-phenazine to CoM-S-S-CoB was analyzed, the initial kinetics of ADP phosphorylation was found to be 0.6 μmol min−1 mg of protein−1 (Fig. 2B) and the initial rate of substrate conversion was 2.4 μmol min−1 mg of protein−1 (Table 2), indicating an ATP/2e− stoichiometry of 0.25 within the first minute of the reaction. ATP synthesis was abolished when either the uncoupler SF 6847 was added or one of the substrates (dihydro-2-OH-phenazine or CoM-S-S-CoB) was omitted. In parallel to the H2-dependent 2-OH-phenazine reduction, the addition of DCCD led to a decrease of electron transport from dihydro-2-OH-phenazine to CoM-S-S-CoB (Table 2) and to inhibition of ATP synthesis (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, in the absence of ADP the heterodisulfide reductase activity decreased to 50% of the control rate (ADP added [Table 2]) and ATP synthesis was abolished (Fig. 2B). Inhibition of electron transfer under these conditions was relieved by the addition of SF 6847, indicated by the stimulation of electron transport activities 2.4-fold (addition of DCCD) and 2.3-fold (ADP omitted) (Table 2) in comparison to the assays performed with no uncoupler. Thus, the effects of SF 6847 and DCCD on both partial electron transport reactions resemble the phenomenon of respiratory control observed in mitochondria.

DISCUSSION

Several membrane-bound proteins and enzyme systems from Methanosarcina strains have been found to be involved in the generation of transmembrane electrochemical ion gradients. The H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase, the F420H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase, and the CO:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase generate a proton motive force by redox potential-driven H+ translocation (8, 24). In contrast, the methyltetrahydromethanopterin:HS-CoM methyltransferase (20) and probably the formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase (14) are reversible sodium ion pumps. It is remarkable that protons as well as sodium ions are employed by M. mazei Gö1 as coupling ions in energy conservation.

In this report, we focus on the catalytic activity of the H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase system which is composed of a membrane-bound, F420-nonreducing hydrogenase and the heterodisulfide reductase (29). Until recently, detailed analysis of the system was hindered by the lack of information about the nature of electron carriers mediating electron transfer between the enzymes. With the identification of methanophenazine and the elucidation of the reactivity of its water-soluble analogue 2-OH-phenazine, the overall mechanism of electron transfer became evident (Fig. 3). It was found that the F420-nonreducing hydrogenase (VhoGA) catalyzes the oxidation of molecular hydrogen and transfers electrons via a b-type cytochrome (VhoC) to 2-OH-phenazine (reaction 1). The resulting dihydro-2-OH-phenazine is oxidized by the heterodisulfide reductase and the electrons are transferred to CoM-S-S-CoB (reaction 2) (6). Here it is shown that both partial reactions of the H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase are coupled to proton translocation, exhibiting stoichiometries of 0.9 H+/2e−. Thus, the ratios summed to 1.8 H+/2e−, which corresponds to the efficiency of the overall electron transport from H2 to CoM-S-S-CoB. Keeping in mind that about 50% of the membrane structures present in the vesicle preparations catalyzed electron transport but were unable to establish a proton gradient (8), the H+/2e− values of the partial reactions and of the overall reaction increase to 1.8 and 3.6, respectively. Accordingly, the sum of the ATP/2e− ratios of both reactions would rise from 0.5 to about 1.0. In agreement with this hypothesis is the fact that 3 to 4 H+/2e− were transferred by whole-cell preparations of M. barkeri when methane formation from methanol plus H2 was analyzed (5). Under standard conditions, the sum of the changes of free energy associated with reaction 1 and 2 is about −40 kJ/mol, which is sufficient to drive the phosphorylation of 1 mol of ATP (ΔG0′ = 31.8 kJ/mol [28]). However, in the environment of the cell, the ΔG value is probably more negative. It is to note that the methyl-CoM reductase, which is present in abundance in the cell, catalyzes the irreversible formation of the heterodisulfide from methyl-CoM and HS-CoB (ΔG0′ = −45 kJ/mol). Therefore, it is likely that the intercellular [CoM-S-S-CoB]/[HS-CoM] [HS-CoB] ratio is very high. As a consequence, the span of available free energy would be greater than calculated from standard conditions, indicating that the energy-conserving reduction of CoM-S-S-CoB is driven forward by the preceding methane-forming reaction (29).

FIG. 3.

Tentative scheme of membrane-bound electron transfer coupled to proton translocation in M. mazei Gö1. Mphen, methanophenazine; MphenH2, dihydromethanophenazine; VhoG, 40-kDa subunit of the F420-nonreducing hydrogenase; VhoA, 60-kDa subunit of the F420-nonreducing hydrogenase; VhoC, cytochrome b1 (Cytb1) encoded by the third gene (vhoC) of the hydrogenase operon; HdrDE, subunits of the heterodisulfide reductase; FeS, iron-sulfur clusters; Ni, nickel-iron center of the F420-nonreducing hydrogenase.

A tentative scheme of the mechanism of proton translocation, which is based on the structures and locations of the key enzymes of the system, is shown in Fig. 3. The operon encoding the F420-nonreducing hydrogenase from M. mazei Gö1 contains three genes (8). The deduced amino acid sequences revealed that the small (VhoG) and large (VhoA) subunits of the protein are homologous to the corresponding polypeptides of membrane-bound NiFe hydrogenases from several bacteria (9, 18, 22). The organisms contain a b-type cytochrome which is connected to the core enzyme. In M. mazei, this function is fulfilled by VhoC (cytochrome b1), which is encoded by the third gene of the hydrogenase operon. Electron microscopic immunogold labeling experiments revealed that at least part of the large subunit of the enzyme from Ralstonia eutropha is exposed toward the periplasm (10). Therefore, it is likely that the active center of the enzyme is located at the periplasmic face of the membrane. During H2 oxidation by R. eutropha, a electrochemical proton gradient is generated by linking movement of electrons from the periplasmic side to the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, with the release of protons in the periplasm and uptake of protons from the cytoplasm in the course of ubiquinone reduction (4, 17). The same mechanism was suggested for Δp generation by fumarate respiration with H2 in Wolinella succinogenes (12). Since the membrane-bound hydrogenases from R. eutropha and W. succinogenes are homologous to the corresponding enzyme from M. mazei Gö1, the same kind of energy conservation may be involved in the latter organism. The oxidation of molecular hydrogen at the periplasmic site of the cytoplasmic membrane of strain Gö1 would lead to the production of two scalar protons. The electrons derived from the reaction are transferred to cytochrome b1, which would accept two protons from the cytoplasm for the reduction of methanophenazine (Fig. 3).

The mechanism of energy conservation in the course of partial reaction 2 might also be based on scalar proton transfer. The purified heterodisulfide reductase from Methanosarcina species, which catalyzes the dihydro-2-OH-phenazine-dependent CoM-S-S-CoB reduction, is composed of two subunits (19, 26). HdrD harbors the active center and contains two Fe4S4 clusters which are involved in the reaction mechanism (26). The subunit is predicted to be membrane-associated since membrane-spanning helices are absent (27). HdrE is a b-type cytochrome and contains two distinct heme groups. Hydropathy plots revealed that the protein possesses five membrane-spanning helices (19). Redox-driven H+ translocation was detected in assays using washed vesicles from strain Gö1. However, the purified heterodisulfide reductase also catalyzed the reduction of CoM-S-S-CoB with dihydro-2-OH-phenazine as the electron donor, with high rates indicating that the enzyme is directly involved in proton translocation. A tentative mechanism of this process is shown in Fig. 3. We assume that in vivo electrons from dihydromethanophenazine are transferred to the heme group of HdrE and scalar protons are released at the outer phase of the cytoplasmic membrane. In a second step, the electrons are channeled to FeS clusters of HdrD and in the reactive center, CoM-S-S-CoB is reduced to HS-CoM and HS-CoB. We propose that protons necessary for this reaction are derived from the cytoplasm and are transferred to the active site by a proton-conducting channel built around a selected number of polar amino acid side chains as well as bound water molecules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bonn-Bad Godesberg).

We are indebted to G. Gottschalk, Göttingen, Germany, for support and stimulating iscussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abken H-J, Tietze M, Brodersen J, Bäumer S, Beifuss U, Deppenmeier U. Isolation and characterization of methanophenazine and the function of phenazines in membrane-bound electron transport of Methanosarcina mazei Gö1. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2027–2032. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2027-2032.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bäumer S, Murakami E, Brodersen J, Gottschalk G, Ragsdale S W, Deppenmeier U. The F420H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase system from Methanosarcina species. FEBS Lett. 1998;428:295–298. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00555-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becher B, Müller V. Δμ̃Na+ drives the synthesis of ATP via a Na+-translocating F1F0-ATP synthase in membrane vesicles of the archaeon Methanosarcina mazei strain Gö1. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2543–2550. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2543-2550.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernhard M, Schwartz E, Rietdorf J, Friedrich B. The Alcaligenes eutrophus membrane-bound hydrogenase gene locus encodes functions involved in maturation and electron transport coupling. J Bacteriol. 1997;178:4522–4529. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4522-4529.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaut M, Müller V, Gottschalk G. Proton translocation coupled to methanogenesis from methanol+hydrogen in Methanosarcina barkeri. FEBS Lett. 1987;215:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodersen J, Bäumer S, Abken H J, Gottschalk G, Deppenmeier U. Inhibition of membrane-bound electron transport of the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina mazei Gö1 by diphenyleneiodonium. Eur J Biochem. 1999;259:218–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deppenmeier U, Blaut M, Mahlmann A, Gottschalk G. Reduced coenzyme F420H2-dependent heterodisulfide oxidoreductase: a proton translocating redox system in methanogenic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9449–9453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deppenmeier U, Müller V, Gottschalk G. Pathways of energy conservation in methanogenic archaea. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:149–163. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dross F, Geisler V, Lengler R, Theis F, Krafft T, Fahrenholz F, Kojro E, Duchene A, Tripier D, Juvenal K, Kröger A. The quinone-reactive Ni/Fe-hydrogenase of Wolinella succinogenes. Eur J Biochem. 1992;206:93–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eismann K, Mlejnek K, Zipprich D, Hoppert M, Gerberding H, Mayer F. Antigenic determinants of the membrane-bound hydrogenase in Alcaligenes eutrophus are exposed toward the periplasm. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6309–6312. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6309-6312.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferry J G. Enzymology of the fermentation of acetate to methane by Methanosarcina thermophila. BioFactors. 1997;6:25–35. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520060104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross R, Simon J, Theis F, Kröger A. Two membrane anchors of Wolinella succinogenes hydrogenase and their function in fumarate and polysulfide respiration. Arch Microbiol. 1998;170:50–58. doi: 10.1007/s002030050614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heiden S, Hedderich R, Setzke E, Thauer R K. Purification of a cytochrome b containing H2:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase complex from membranes of Methanosarcina barkeri. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213:529–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaesler B, Schönheit P. The role of sodium ions in methanogenesis. Formaldehyde oxidation to CO2 and 2 H2 in methanogenic bacteria is coupled with primary electrogenic Na+ translocation at a stoichiometry of 2-3 Na+/CO2. Eur J Biochem. 1989;184:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamlage B, Blaut M. Characterization of cytochromes from Methanosarcina strain Gö1 and their involvement in electron transport during growth on methanol. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3921–3927. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3921-3927.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimmich G A, Randles J, Brand J S. Assay of picomole amounts of ATP, ADP and AMP using the luciferase enzyme system. Anal Biochem. 1975;69:187–206. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kömen R, Zannoni D, Schmidt K. The electron transport system of Alcaligenes eutrophus. Arch Microbiol. 1991;155:436–443. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kortlüke C, Horstmann K, Schwartz E, Rohde M, Binsack R, Friedrich B. A gene complex coding for the membrane-bound hydrogenase of Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6277–6289. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6277-6289.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Künkel A, Vaupel M, Heim S, Thauer R K, Hedderich R. Heterodisulfide reductase from methanol-grown cells of Methanosarcina barkeri is not a flavoprotein. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:226–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lienard T, Becher B, Marschall M, Bowien S, Gottschalk G. Sodium ion translocation by N5-methyltetrahydromethanopterin:coenzyme M methyltransferase from Methanosarcina mazei Gö1 reconstituted in ether liposomes. Eur J Biochem. 1996;239:857–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0857u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer F, Jussofie A, Salzmann M, Lübben M, Rohde M, Gottschalk G. Immunoelectron microscopic demonstration of ATPase on the cytoplasmic membrane of the methanogenic bacterium strain Gö1. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2307–2309. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.2307-2309.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menon N K, Robbins J, Peck H D, Jr, Chatelus C Y, Choi E S, Przybyla A E. Cloning and sequencing of a putative Escherichia coli [NiFe] hydrogenase-1 operon containing six open reading frames. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1969–1977. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1969-1977.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noll K M, Donnelly M I, Wolfe R S. Synthesis of 7-mercaptoheptanoylthreonine phosphate and its activity in the methylcoenzyme M methylreductase system. J Biol Chem. 1986;262:513–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peer C W, Painter M H, Rasche M E, Ferry J G. Characterization of a CO:heterodisulfide oxidoreductase system from acetate-grown Methanosarcina thermophila. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6974–6979. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6974-6979.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruppert C, Wimmers S, Lemker T, Müller V. The A1A0 ATPase from Methanosarcina mazei: cloning of the 5′ end of the aha operon encoding the membrane domain and expression of the proteolipid in a membrane-bound form in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3448–3452. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3448-3452.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simianu M, Murakami E, Brewer J M, Ragsdale S W. Purification and properties of the heme and iron-sulfur containing heterodisulfide reductase from Methanosarcina thermophila. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10027–10039. doi: 10.1021/bi9726483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonnhammer E L L, von Heijne G, Krogh A. Proceedings of Sixth International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology. Menlo Park, Calif: AAAI Press; 1998. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences; pp. 175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thauer R K, Jungermann K, Decker K. Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1977;41:100–180. doi: 10.1128/br.41.1.100-180.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thauer R K. Biochemistry of methanogenesis: a tribute to Marjory Stephenson. Microbiology. 1998;144:2377–2406. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]