Abstract

The AOX1 gene, which encodes an alternative oxidase, was isolated from the genomic DNA library of Candida albicans. The gene encodes a polypeptide consisting of 379 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 43,975 Da. The aox1/aox1 mutant strain did not show cyanide-resistant respiration under normal conditions but could still induce cyanide-resistant respiration when treated with antimycin A. The measurement of respiratory activity and Western blot analysis suggested the presence of another AOX. When C. albicans AOX1 was expressed in alternative oxidase-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae, it could confer cyanide-resistant respiration on S. cerevisiae.

In addition to the cytochrome-involved respiratory pathway, higher plants (11), protists (6), and fungi (17, 22) are known to possess an alternative, cyanide-resistant respiratory pathway, which is specifically inhibited by hydroxamic acids (27). Cyanide-resistant respiration appears to be mediated by alternative oxidase (AOX), which is believed to accept electrons from the ubiquinone pool of the main cytochrome pathway and to reduce oxygen to water (2). The detailed nature and the physiological roles of the alternative respiratory pathway mediated by AOX are still poorly understood. Cyanide-resistant respiration has been shown to be involved in thermogenic inflorescence (21), climacteric and ripening of fruits (15), and cell-type proportioning during Dictyostelium development (19). Some reports show that reactive oxygen species, such as superoxide radical anion or hydrogen peroxide, induce the expression of AOX (23, 32). These observations suggest that cyanide-resistant respiration is related to defense systems against oxidative stress.

In the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans, the existence of cyanide-resistant respiration has been previously reported (1, 28). However, the process by which the alternative respiratory pathway appears in this fungus is still controversial. As a first step to investigate the nature and the physiological roles of cyanide-resistant respiration in C. albicans, we isolated the AOX1 gene, which encodes an AOX, and report here the effects of disruption and overexpression of the AOX1 gene in C. albicans. We also report the functional expression of the C. albicans AOX1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Yeast strains and media.

The C. albicans and S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. For routine growth of cells, YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) was used. The cells containing plasmids or disrupted genes were cultured in synthetic dextrose (SD) minimal medium with the appropriate supplement (29). Ura− auxotrophs were selected on SD minimal medium supplemented with 625 mg of 5-fluoroorotic acid and 30 mg of uridine per liter (FOA medium).

TABLE 1.

C. albicans and S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | ||

| ATCC 10231 | Wild type | ATCCa |

| CAI4 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 | 9 |

| WH301 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 Δaox1::hisG-URA3-hisG/AOX1 | This work |

| WH302 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 Δaox1::hisG/AOX1 | This work |

| WH303 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 Δaox1::hisG/Δaox1::hisG-URA3-hisG | This work |

| WH304 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 Δaox1::hisG/Δaox1::hisG | This work |

| WH305 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 (pRC2312) | This workb |

| WH306 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 (pWK302) | This workc |

| S. cerevisiae | ||

| WH113 | MATa/MATα ade2-1/ADE2 his3-Δ1/his3-Δ200 leu2-3/LEU2 leu2-112/LEU2 lys2-801a/LYS2 trp1-289/trp1Δ ura3-52/ura3-52 | 13 |

| WH117 | MATa/MATα ade2-1/ADE2 his3-Δ1/his3-Δ200 leu2-3/LEU2 leu2-112/LEU2 lys2-801a/LYS2 trp1-289/trp1Δ ura3-52/ura3-52 (pRS424) | 13 |

| WH119 | MATa/MATα ade2-1/ADE2 his3-Δ1/his3-Δ200 leu2-3/LEU2 leu2-112/LEU2 lys2-801a/LYS2 trp1-289/trp1Δ ura3-52/ura3-52 (pWK303) | This workd |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

CAI4 + pRC2312.

CAI4 + pWK302.

WH113 + pWK303.

Isolation and characterization of the AOX1 gene from C. albicans.

A genomic library of C. albicans was generated by partially digesting chromosomal DNA with Sau3AI, followed by ligation into λEMBL3 vector (Stratagene) and packaging with Gigapack II packaging extracts (Stratagene). From the predicted amino acid sequences of AOXs from Sauromatum guttatum (24), Arabidopsis thaliana (14), Glycine max (33), Nicotiana tabacum (31), Mangifera indica (7), Trypanosoma brucei (4), Hansenula anomala (25), and Neurospora crassa (18), two highly conserved regions were identified, and the degenerate oligonucleotide primers corresponding to residues 145 to 151 (AGVPGMV) and 229 to 235 (GYLEEEA) of H. anomala AOX (25)—5′-GCTGGTGT(C/T)CC(A/T)GGTATGGT-3′ and 5′-GCTTCTTC(C/T)TCCAA(A/G)TAACC-3′, respectively—were synthesized. PCR using the oligonucleotide primer pair could amplify a DNA fragment of about 0.3 kbp from the chromosomal DNA of C. albicans ATCC 10231. When cloned and sequenced, the fragment showed a high degree of amino acid sequence similarity to H. anomala AOX upon BLAST searches of the GenBank database. The cloned PCR product was used as a probe to screen the λEMBL3 genomic library. From positive clones, the common 3.2-kbp EcoRV fragment was subcloned in pGEM-5Zf(+) (Promega) and sequenced.

The cloned insert contained a continuous open reading frame (ORF) of 1,140 bp that encodes a polypeptide consisting of 379 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 43,975 Da. C. albicans AOX1 did not contain the CUG codon, which encodes serine in C. albicans but encodes leucine in S. cerevisiae and elsewhere (26). The nucleotide sequence of AOX1 did not have the consensus sequence for splicing. The fact that the gene does not contain an intron was confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR (data not shown). The predicted amino acid sequence of C. albicans AOX showed 54, 35, and 24% identity to that of H. anomala AOX (25), N. crassa AOX (18), and S. guttatum AOX (24), respectively. The hydropathy plot of AOX obtained according to the method proposed by Kyte and Doolittle (16) predicted that the enzyme would be an integral membrane protein with two transmembrane segments corresponding to amino acid residues 176 to 194 and 239 to 257. This prediction agreed well with the previous reports (20) in which AOX was supposed to be an inner mitochondrial membrane protein with two membrane-spanning helices. According to the method proposed by Gavel and von Heijne (10), the cleavage site for the mitochondrial presequence was predicted to be between Ser residues at positions 42 and 43. The molecular mass of the presumed mature form of C. albicans AOX, which consists of 337 amino acids, was calculated to be 39,331 Da.

On genomic Southern analysis with the genomic DNA from C. albicans ATCC 10231, four bands were detected when the genomic DNA was digested with ClaI, EcoRI, or HindIII, and two bands were detected when the genomic DNA was digested with XbaI (data not shown). Since the nucleotide sequence of AOX1 ORF contains one ClaI site, one EcoRI site, two HindIII sites, and no XbaI site, this hybridization pattern strongly suggested that AOX is encoded by a gene family with two members in C. albicans. In order to estimate the mRNA size and study the possible transcriptional regulation of AOX1, Northern blot analysis was carried out. However, it was impossible to obtain the signal for AOX1, presumably because of the very low level of AOX1 mRNA.

Disruption and overexpression of AOX1 in C. albicans.

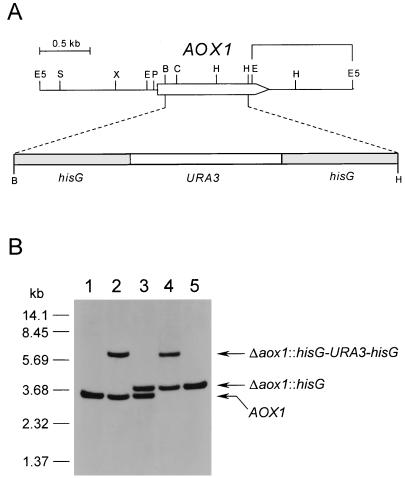

Disruption of AOX1 in C. albicans was carried out as described by Fonzi and Irwin (9). An in vitro construct was prepared by replacing a portion of the coding region of AOX1 with the hisG-URA3-hisG sequence (Fig. 1A), and used to transform CAI4. The resulting Ura+ transformants were screened by Southern blot analysis, and the spontaneous Ura− pop-out revertants from them were selected on FOA medium. A homozygous disruption of AOX1 was generated by repeating the above procedure, and confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1B). In order to overexpress AOX1 in C. albicans, we constructed the plasmid pWK302 by inserting the entire AOX1 gene and its flanking sequences into the plasmid pRC2312 (3). C. albicans cells were transformed with the parent plasmid pRC2312 or pWK302, and transformants containing either plasmid were selected by plating on uracil-deficient medium.

FIG. 1.

Sequential disruption of C. albicans AOX1. (A) Restriction map of the AOX1 locus and insertion of the hisG-URA3-hisG cassette at the BglII/HindIII sites in the AOX1 coding sequence. The endonuclease restriction sites are abbreviated as follows: B, BglII; C, ClaI; E, EcoRI; E5, EcoRV; H, HindIII; P, PstI; S, SpeI; X, XbaI. (B) Southern blot analysis with the bracketed sequence (as indicated in A) used as a probe. The DNA digested with BglII was from the following strains: lane 1, CAI4, AOX1/AOX1; lane 2, WH301, Δaox1::hisG-URA3-hisG/AOX1; lane 3, WH302, Δaox1::hisG/AOX1; lane 4, WH303, Δaox1::hisG/Δaox1::hisG-URA3-hisG; lane 5, WH304, Δaox1::hisG/Δaox1::hisG.

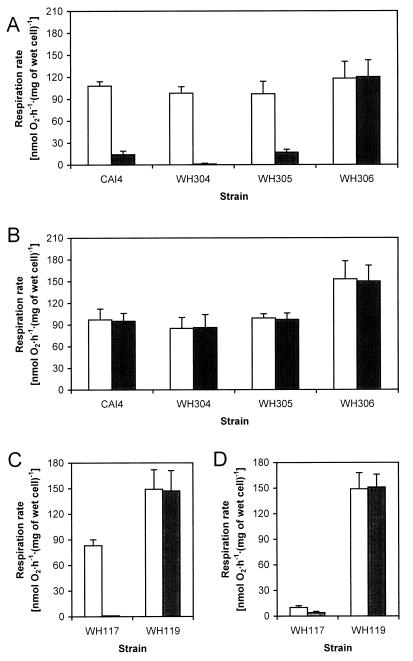

Respiration of cells was measured polarographically at 25°C by using a YSI 5300 Biological Oxygen Monitor Micro System (Yellow Springs Instrument) as described by Minagawa and Yoshimoto (22). The total respiration rate of fresh CAI4 was approximately 108 nmol of O2 · h−1 · (mg of wet cell)−1 (Fig. 2A). When 1 mM KCN was added to the cells, the respiration rate was reduced to 14 nmol of O2 · h−1 · (mg of wet cell)−1, which corresponds to the rate of cyanide-resistant respiration. The total respiration rate of fresh WH304 was about 9% lower than that of CAI4, and its cyanide-resistant respiration was scarcely observed on the addition of KCN. The respiratory behavior of WH305 carrying the empty vector pRC2312 was somewhat similar to that of CAI4. In the case of WH306 transformed with pWK302 plasmid containing AOX1, the total respiration rate was about 22% higher than that of WH305 as a reference, and the rate did not change on the addition of KCN. These results indicated that the cloned AOX1 gene encodes a functional AOX enzyme.

FIG. 2.

Respiratory characteristics of C. albicans and S. cerevisiae strains. Shown are respiratory activities of fresh cells of C. albicans (A), antimycin A-treated cells of C. albicans (B), fresh cells of S. cerevisiae (C), and antimycin A-treated cells of S. cerevisiae (D). Oxygen uptake in the absence (open bars) or the presence (solid bars) of 1 mM KCN was measured with an oxygen monitor. Data shown represent the means + standard errors (error bars) of three independent experiments. The absence of an error bar indicates that the error was too small to allow display of the error in the columns.

It has been reported that the expression of AOX protein is induced and cyanide-resistant respiration increases when the cytochrome pathway is blocked by the respiratory inhibitors (25, 30). To investigate the effects of respiratory inhibitor on cyanide-resistant respiration of C. albicans, cells were incubated in the presence of 10 μM antimycin A for 1 h as described by Sakajo et al. (25). Incubation of CAI4 in the presence of 10 μM antimycin A greatly enhanced cyanide-resistant respiration, the rate of which was almost identical to the total respiration rate (Fig. 2B). Unexpectedly, WH304 treated with antimycin A also showed cyanide-resistant respiration, the rate of which was about 91% of that of CAI4. Considering that WH304 is the aox1/aox1 null mutant strain, this observation strongly suggested that C. albicans may have another AOX, which can be induced by antimycin A. The respiratory activity of antimycin A-treated WH305 was similar to that of CAI4, and the cyanide-resistant respiration rate of antimycin A-treated WH306 was about 58% higher than that of WH305 as a reference.

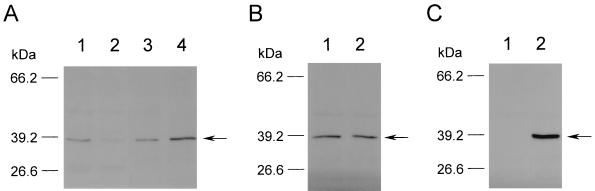

For Western blot analysis, C. albicans mitochondria were isolated as described previously (12); added to 125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, containing 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 20% glycerol, and 0.004% bromophenol blue; and boiled for 2 min. Polyacrylamide gel (8%) was used for separating the mitochondrial proteins. The resolved proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) and probed with the antibody raised against the AOX protein from S. guttatum (8) at dilutions of 1:1,000. Western blot analysis with fresh cells showed that AOX was little expressed in WH304 and the expression of AOX remarkably increased in WH306 compared with WH305 (Fig. 3A). These results were consistent with the measurement of respiration (Fig. 2A). In Western blots, AOX from C. albicans appeared to occur as a monomeric form with an apparent molecular mass of 39 kDa. The apparent molecular mass of C. albicans AOX coincided well with the predicted molecular mass of the mature enzyme (39,331 Da). When WH304 was treated with antimycin A, we could observe the induction of another AOX protein, which occurred at the same position in SDS-polyacrylamide gel as that of the cloned one (Fig. 3B). These observations demonstrated the presence of another AOX, which is also supported by the result of genomic Southern blot analysis, which indicated that AOX is encoded by a gene family with two members in C. albicans.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of AOX. (A) Western blot analysis of AOX from fresh cells of CAI4 (lane 1), WH304 (lane 2), WH305 (lane 3), and WH306 (lane 4). (B) Western blot analysis of AOX from antimycin A-treated cells of CAI4 (lane 1) and WH304 (lane 2). (C) Western blot analysis of AOX from WH117 (lane 1) and WH119 (lane 2). Mitochondrial proteins (30 μg) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with a monoclonal antibody to AOX. Numbers on the left side of the immunoblots are molecular masses of the standards. The arrow on the right side of each immunoblot indicates AOX.

Functional expression of C. albicans AOX1 in S. cerevisiae.

It has been reported that S. cerevisiae does not have cyanide-resistant respiration mediated by AOX (22). We introduced C. albicans AOX1 into S. cerevisiae to see whether it can confer cyanide-resistant respiration on S. cerevisiae. In order to express C. albicans AOX1 in S. cerevisiae, we constructed the plasmid pWK303 by inserting the entire AOX1 gene and its flanking sequences into the plasmid pRS424 (5). Then, S. cerevisiae cells were transformed with the parent plasmid pRS424 or pWK303, and Trp+ transformants were selected. As expected, the respiration of WH117 carrying the empty vector was completely inhibited by the addition of KCN (Fig. 2C). In the case of WH119 transformed with a multicopy plasmid containing C. albicans AOX1, the total respiration rate was about 80% higher than that of WH117 as a reference and the addition of KCN did not affect the respiration rate. The total respiration rate of WH117 incubated in the presence of 10 μM antimycin A decreased dramatically (Fig. 2D). The respiratory activity of antimycin A-treated cells of WH119 was similar to that of fresh cells of WH119. In accordance with the measurement of respiration, Western blot analysis demonstrated that AOX was highly expressed in WH119 (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that C. albicans AOX can be functionally expressed in AOX-deficient S. cerevisiae and confirmed that the presence of AOX is enough to carry out cyanide-resistant respiration.

According to Kumar and Söll (14), Arabidopsis AOX could confer cyanide-resistance on E. coli; E. coli cells transformed with a plasmid carrying the Arabidopsis AOX gene grew well in the presence of 0.5 mM KCN, which suppressed growth of the cells transformed with the empty vector. In order to examine if C. albicans AOX could enhance cyanide-resistant growth of S. cerevisiae, WH117 and WH119 were grown in the medium containing 0.5 mM KCN and cell growth was monitored. The presence of KCN significantly retarded the cell growth in both strains. However, there was no difference in cell growth pattern between WH117 and WH119 (data not shown). Presumably, an unknown cyanide-resistant respiratory pathway inherent in S. cerevisiae, which is not mediated by AOX, may be sufficient to cause cyanide-resistant growth in S. cerevisiae.

Since seed germination, wound healing, flowering, and exposure to cold shock or oxidants were shown to be associated with increased AOX activity, AOX seems to be closely related to cell differentiation or stress response. However, the precise regulation mechanism and physiological roles of AOX have not been fully understood yet. C. albicans, one of the dimorphic fungi, is a good model system for studying cell differentiation and understanding the biology of eukaryotic organisms. Therefore, the investigation of AOX in C. albicans is believed to contribute greatly to elucidating the nature of cyanide-resistant respiration. At present, we are attempting to clone another AOX from C. albicans, which is induced by respiratory inhibitors.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper have been submitted to GenBank under accession no. AF031229.

Acknowledgments

We thank William A. Fonzi for providing strain CAI4 and the p5921 plasmid and Richard D. Cannon for providing the pRC2312 plasmid. We also thank Thomas E. Elthon for the generous gift of the monoclonal antibody against AOX.

This work was supported by a research grant for the SRC (Research Center for Molecular Microbiology, Seoul National University) from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki S, Ito-Kuwa S. Respiration of Candida albicans in relation to morphogenesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 1982;23:721–726. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berthold D A, Siedow J N. Partial purification of the cyanide-resistant alternative oxidase of skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus) mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:113–119. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cannon R D, Jenkinson H F, Shepherd M G. Cloning and expression of Candida albicans ADE2 and proteinase genes on a replicative plasmid in C. albicans and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;235:453–457. doi: 10.1007/BF00279393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhuri M, Hill G C. Cloning, sequencing, and functional activity of the Trypanosoma brucei brucei alternative oxidase. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;83:125–129. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christianson T W, Sikorski R S, Dante M, Shero J H, Hieter P. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene. 1992;110:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarkson A B, Jr, Bienen E J, Pollakis G, Grady R W. Respiration of bloodstream forms of the parasite Trypanosoma brucei brucei is dependent on a plant-like alternative oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17770–17776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz-Hernandez A, Gomez-Lim M A. Alternative oxidase from mango (Mangifera indica, L.) is differentially regulated during fruit ripening. Planta. 1995;197:569–576. doi: 10.1007/BF00191562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elthon T E, Nickels R L, McIntosh L. Monoclonal antibodies to the alternative oxidase of higher plant mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 1989;89:1311–1317. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.4.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonzi W A, Irwin M Y. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gavel Y, von Heijne G. Cleavage-site motifs in mitochondrial targeting peptides. Protein Eng. 1990;4:33–37. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry M F, Nyns E J. Cyanide-insensitive respiration: an alternative mitochondrial pathway. Subcell Biochem. 1975;4:1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huh W-K, Kim S-T, Yang K-S, Seok Y-J, Hah Y C, Kang S-O. Characterization of d-arabinono-1,4-lactone oxidase from Candida albicans ATCC 10231. Eur J Biochem. 1994;225:1073–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.1073b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huh W-K, Lee B-H, Kim S-T, Kim Y-R, Rhie G-E, Baek Y-W, Hwang C-S, Lee J-S, Kang S-O. d-Erythroascorbic acid is an important antioxidant molecule in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:895–903. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar A M, Söll D. Arabidopsis alternative oxidase sustains Escherichia coli respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10842–10846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S, Patil B C, Sinha S K. Cyanide resistant respiration is involved in temperature rise in ripening mangoes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;168:818–822. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)92394-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambowitz A M, Sabourin J R, Bertrand H, Nickels R, McIntosh L. Immunological identification of the alternative oxidase of Neurospora crassa mitochondria. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1362–1364. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, Ritzel R G, McLean L L, McIntosh L, Ko T, Bertrand H, Nargang F E. Cloning and analysis of the alternative oxidase gene of Neurospora crassa. Genetics. 1996;142:129–140. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuyama S I, Maeda Y. Involvement of cyanide-resistant respiration in cell-type proportioning during Dictyostelium development. Dev Biol. 1995;172:182–191. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIntosh L. Molecular biology of the alternative oxidase. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:781–786. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.3.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meeuse B J D. Thermogenic respiration in aroids. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1975;26:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minagawa N, Yoshimoto A. The induction of cyanide-resistant respiration in Hansenula anomala. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1987;101:1141–1146. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a121978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minagawa N, Koga S, Nakano M, Sakajo S, Yoshimoto A. Possible involvement of superoxide anion in the induction of cyanide-resistant respiration in Hansenula anomala. FEBS Lett. 1992;302:217–219. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80444-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhoads D M, McIntosh L. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA clone encoding an alternative oxidase protein of Sauromatum guttatum (Schott) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2122–2126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakajo S, Minagawa N, Komiyama T, Yoshimoto A. Molecular cloning of cDNA for antimycin A-inducible mRNA and its role in cyanide-resistant respiration in Hansenula anomala. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1090:102–108. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90043-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos M A, Tuite M F. The CUG codon is decoded in vivo as serine and not leucine in Candida albicans. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1481–1486. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.9.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schonbaum G R, Bonner W D, Jr, Storey B T, Bahr J T. Specific inhibition of the cyanide-insensitive respiratory pathway in plant mitochondria by hydroxamic acids. Plant Physiol. 1971;47:124–128. doi: 10.1104/pp.47.1.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shepherd M G, Chin C M, Sullivan P A. The alternative respiratory pathway of Candida albicans. Arch Microbiol. 1978;116:61–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00408734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanlerberghe G C, McIntosh L. Coordinate regulation of cytochrome and alternative pathway respiration in tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:1846–1851. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.4.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanlerberghe G C, McIntosh L. Mitochondrial electron transport regulation of nuclear gene expression: studies with the alternative oxidase gene of tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:867–874. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.3.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner A M. A role for active oxygen species as 2nd messengers in the induction of alternative oxidase gene-expression in Petunia-hybrida cells. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:339–342. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00688-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whelan J, McIntosh L, Day D A. Sequencing of a soybean alternative oxidase cDNA clone. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:1481. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.4.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]