Emerging strategies for localized payload delivery to the myocardium.

Central Message.

Local myocardial delivery of biomaterial/cell-based therapeutics remains an area of active development and relevance to cardiac surgeons.

Perspective.

The successful translation of novel cardiac therapies relies on effective strategies for localized payload delivery to the myocardium. The purpose of this review is to analyze local myocardial delivery strategies currently in use, identify persistent limitations, and motivate clinically feasible directions for continued improvement of delivery technologies.

Localized delivery methods aim to achieve therapeutic payload concentrations at specific sites in the body while minimizing off-target delivery/accumulation. An emerging strategy to treat multiple cardiac pathologies is localized payload delivery to the myocardium, which has shown promise to advance treatment options for a wide range of disease states.1,2 Candidate payloads for cardiac therapies include pharmacological molecules/drugs, genes, cells, or a combination of these entities, all of which could be administered alone or in conjunction with implantable biomaterials that promote their localization. For example, a recent review highlighted extensive preclinical and clinical studies that support cell-based myocardial repair and regeneration in varied cardiac disease states despite challenges in delivery, with demonstrated reductions in inflammation and fibrosis, promotion of angiogenesis, and in some cases recovery of cardiac function.3 Irrespective of the specific payload, localized delivery offers better spatiotemporal control of myocardial concentrations compared with traditional oral or systemic intravenous administrations, thereby narrowing the therapeutic window by increasing payload bioavailability.4 Indeed, the clinical translation of the diverse myocardial payloads with manifest therapeutic potential will largely depend on the effectiveness/adoptability of the employed delivery method.

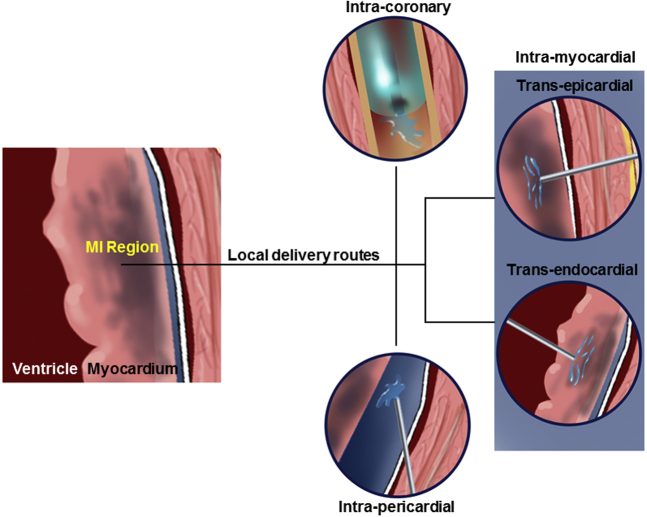

Localized myocardial delivery can be achieved by a range of approaches, including drug-loaded pumps and wafers,5, 6, 7 cardiac patches,8,9 and ultrasound-targeted microbubble cavitation.10,11 Although these and other approaches have distinct advantages and limitations, this review focuses on catheter- and injection-based approaches, which have potential for highly targeted payload delivery with minimal procedural invasiveness. The considered administrative routes include intracoronary delivery (ID), intrapericardial delivery (IPD), and direct intramyocardial delivery (IMD) via transepicardial and transendocardial routes (Figure 1). For each delivery strategy, a procedural overview, demonstrated therapeutic potential, inherent imitations, and exemplary studies are discussed. We conclude that direct IMD via the transepicardial route, by virtue of circumventing challenges associated with both hemodynamics and ventricular motion, represents a promising path forward for the clinical translation of injectable payloads. To support for the clinical feasibility of this approach, we describe the essential features of an enabling delivery system that could be incorporated into minimally invasive cardiac surgery with the potential to deliver a wide range of candidate payloads, including those with a biomaterial component.

Figure 1.

Different approaches for delivery of a payload to the myocardium, particularly targeted therapeutic delivery to the myocardial infarct (MI) region. Catheter-based approach delivers the payload via the coronary artery, whereas the pericardial approach places the payload into the pericardial space/fluid. Direct myocardial delivery would be through an endocardial or epicardial approach.

ID

Overview

ID to the myocardium is a noninvasive administrative route that entails injection of the payload through the coronary arteries or veins. Selective coronary catheterization and perfusion facilitate targeted delivery, wherein the myocardial payload can be effectively directed to the left ventricle (LV) or right ventricle12 and potentially more refined locations such as a myocardial infarct (MI) region or border zone.13 ID is commonly coupled with the stop-flow technique in which an angioplasty balloon is positioned and inflated at low pressures to stop coronary blood flow. During a flow arrest period of approximately 2 to 4 minutes, injectate is infused distally under controlled flow conditions that enhance both payload targeting and myocardial retention. Although arterial catheterization is most common with ID, retrograde coronary venous infusion has been considered in preclinical14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and clinical studies, with the expectation that the low pressure coronary venous system would facilitate payload retention.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Although it provides an alternate route in cases where coronary disease limits arterial access, a 2018 review of published studies concluded that retrograde coronary venous infusion provides inferior myocardial payload retention rates compared with arterial administration despite favorable hemodynamic status.29 Retrograde delivery via coronary sinus infusion has also been explored, with preclinical studies showing potential for plasmid delivery and retention over a significant range of injectate volumes.30 Moreover, coronary sinus infusion has been evaluated in clinical studies of autologous bone marrow delivery for patients with both ischemic and nonischemic heart failure (HF).23 This small clinical trial (60 patients) concluded that coronary sinus infusion is a safe delivery technique and that bone marrow treatment improved LV ejection fraction in both patient populations.

Demonstrated therapeutic potential

ID is a noninvasive administrative route that is well known by interventional cardiologists, relatively simple and inexpensive, and has an extensive history of clinical use. To enable ID, diverse myocardial payloads are stabilized in low viscosity solutions, which readily flow in catheter-based injection devices. In the MI context, ID is the most popular delivery method for multiple myocardial payloads, including mitochondria,31 stem cells,32, 33, 34 drugs,35,36 proteins,37,38 and genes.39 The feasibility and safety of ID-based bone marrow-derived cell therapies have been clinically established, with evidence for MI treatment efficacy.40 Moreover, in a study evaluating ID of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for treatment of chronic MI, delivery augmentation with the stop–flow technique was shown to have equivalent efficiency to transendocardial cell injection.41

Limitations

In cases of ischemic heart disease, severe stenosis of the coronary vasculature may limit ID by preventing arterial catheterization and increasing the risk of embolism. Although ID provides therapeutic benefits in patients with acute MI, efficacy is a less established in chronic clinical applications. For example, in a randomized clinical study of myocardial delivery of CD34(+) cells to 40 patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, ID was shown to be inferior compared with transendocardial delivery (TED) at 6 months in terms of ventricular function, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels, and exercise tolerance.42 In a clinical study involving chronic ischemic myopathy with bone marrow cells (BMCs), sustained ID infusion (∼10 minutes) with transient back-flow prevention was found to be well tolerated and safe, but myocardial function and patient performance were not significantly improved, raising the question targeted delivery efficiency.43 ID within the coronary circulation both creates a high potential for payload washout and presents challenges in targeted delivery, such as with therapeutics that target the peri-infarct zone.44 Indeed, ID of small molecules would be susceptible capillary clearance even with the use of a stop–flow technique.

Injectable biomaterials, endowed by various means with self-assembly characteristics and protracted gelation kinetics such that solids form shortly upon exit from the needle/catheter and entry into the myocardium, have gained significant attention as candidate payloads/platforms for myocardial delivery.45,46 However, administration of biomaterial-based therapies via ID introduces the inherent potential for early biomaterial polymerization within the coronary vasculature and/or biomaterial particulate generation/release within the circulation. Therefore, risks of biomaterial-based ID include both local loss of vessel patency and embolic formation. Nevertheless, recent advancements to facilitate intramyocardial biomaterial polymerization utilize shear thinning47,48 and environmentally responsive49,50 approaches, showing potential to address these risk factors and broaden the payload range for ID.

IPD

Overview

The pericardium consists of an external fibrous layer and internal serosal layer, which together enclose a fluid-filled pericardial cavity with a volume of approximately 20 to 60 mL.51 IPD entails payload injection into the pericardial cavity, which can be accessed in both open- and closed-chest procedures. Surgical access routes include thoracotomy with either medial sternotomy access or a lateral thoracotomy in which access is through the intercostal space. Multiple devices have been proposed to facilitate IPD in minimally invasive, percutaneous procedures, including the commercial products PerDUCER (Comedicus Inc.),52,53 AttachLifter (Developed at the Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiology of the Heart Center and the Technical Development Plant of the Medical Center and Medical Faculty of the Philipps University of Marburg, Office for Research and Technology Transfer),54 and other subxiphoid access systems.55,56 Methods for both bolus and sustained IPD delivery have been proposed to treat a range of cardiovascular diseases, including MI,57 arterial fibrillation,58,59 arrythmia,60,61 and pericarditis.62

Demonstrated therapeutic potential

IPD exploits the enclosed nature of the pericardium and the anatomical continuity with the myocardium, whereby payload injection into the pericardial cavity creates a reservoir that facilitates rapid transport and perfusion of the entire heart. Advantages of IPD are therefore due primarily to the position and structure of the pericardium, providing potential therapeutic benefits derived from both local and global enhancement of cardiac function. For example, IPD of sodium nitroprusside in a canine model of induced arrhythmia was shown to abolish cyclic flow variations, with therapeutic gains reported at lower dosing compared with intravenous administration.63 Other studies have evaluated a range of payloads for neural regulation of cardiac electrophysiology in canine models in which IPD via medial sternotomy was deployed, with delivery of prostaglandins, hexamethonium, and tetrodotoxin all showing clinical feasibility.64, 65, 66 Similarly, sustained (ie, 72 hours) IPD of the oxide donor drug amiodarone resulted in equivalent/enhanced myocardial levels compared with long-term oral dosing in adult sheep.67 In a porcine model of chronic myocardial ischemia, IPD of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) exhibited higher myocardial retention and lower systemic recirculation compared with intravenous administration.37 These and other6,68 studies support IPD as a promising delivery route to treat arrhythmias and circumvent systemic delivery limitations associated with off-target (primarily liver and kidney) drug accumulation.

Limitations

IPD inherently requires puncturing of the pericardium, which may compromise its physiological role. Whereas needle- or catheter-based IPD is safe in cases where sufficient pericardial fluid exists, diminished volume challenges delivery and elevates risk of surgical damage.69 Compared with ID, IPD is limited by a lack of proven access methods/technologies and less familiarity among surgeons. Patient-specific obstacles, including the presence of pericardial adhesions and excess epicardial fat, may further challenge IPD. Moreover, treatment localization to a specific myocardial territory is not possible, and in some cases adequate drug delivery to targeted regions is difficult. For example, IPD delivery of bFGF in a porcine model of chronic ischemia was noted to yield diminished subendocardial penetration compared with ID, although it did not compromise treatment efficacy.37 For sustained IPD applications, including antiarrhythmia therapies, the need for prolonged patient care and associated cost increases should be considered. Due to lymphatic drainage of the pericardial fluid, soluble payloads within the pericardial space may migrate to other organs and create moderate risk of extracardiac payload delivery.70

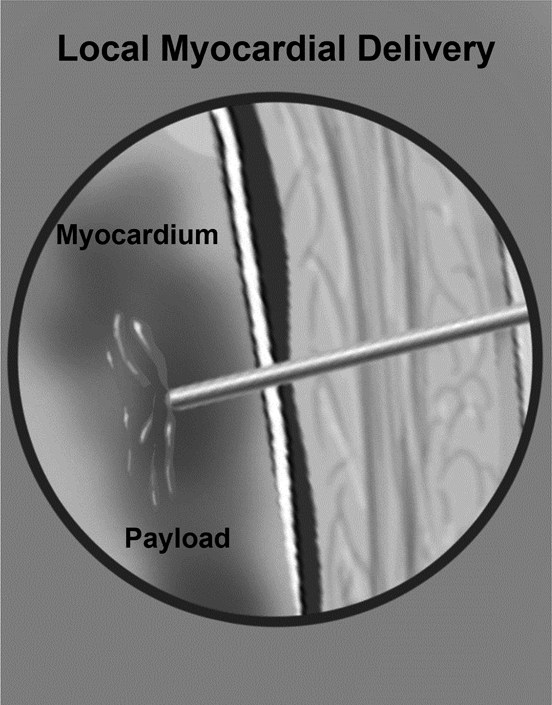

IMD: Transepicardial Route

Overview

IMD entails direct injection of a therapeutic payload into the myocardium and is therefore a direct administrative route. In open-chest procedures, epicardial access readily enables direct myocardial payload delivery, which in addition to transepicardial injection may be achieved via local biomaterial implantation or spraying. For example, in a clinical study of patients with ischemic heart disease that were undergoing a coronary artery bypass graft procedure, bFGF delivery via sustained-release heparin-alginate microcapsules implanted in epicardial fat was shown to be both feasible and safe.71 Multiple studies have shown that epicardial spraying of drug-loaded hydrogels is well tolerated, increases drug effectiveness over other administrative routes, and reduces the risk of extracardiac adverse drug side effects.36,72,73 Another clinical study of 100 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting showed that diffuse epicardial spraying of the drug amiodarone loaded in a polyethylene glycol-based hydrogel reduced postoperative atrial fibrillation for a period of 14 days.35

Demonstrated therapeutic potential

Advantages of IMD via the transepicardial route include visual access to the target site and the ability to readily control perforations or hemorrhage introduced during the procedure. Perhaps due to these practical advantages, early-stage/proof-of-concept studies involving IMD more commonly employ the transepicardial as opposed to transendocardial route. For example, in mice, transepicardial gene delivery via direct injection of modified mRNA demonstrated successful transfection and provided impetus for further development of this therapeutic approach.74 In a preclinical sheep MI model evaluating mesenchymal precursor cells delivered via transepicardial injection, reported outcomes included improvement in LVEF and LV end-diastolic volume over placebo at 8 weeks postinjection.75 Another preclinical study explored transepicardial delivery of commercially available dermal fillers (ie, acellular biomaterial) in an anteroapical infarct sheep model, wherein findings include a reduction in MI expansion at early post-MI times.76 Transepicardial injection of MSCs into the myocardium has been demonstrated in a range of MI models, with promising reports of postdelivery cellular differentiation into cardiomyocytes.77, 78, 79 Other combinations for the injectate (including cardiac stem cells, umbilical cord MSCs, and other cellular repair promoters) were developed and tested using the transepicardial delivery route for acute MI in animal models and small clinical trials.80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87 For example, in a porcine MI model, transepicardial delivery of human MSCs with tyrosine-protein kinase kit + human cardiac stem cells revealed a synergistic effect in scar size reduction and restoration of systolic function.88

A multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial with 78 patients with advanced HF assessed LV augmentation via IMD of an injectable calcium alginate hydrogel (Algisyl, LoneStar Heart Inc.), which was delivered during surgery (limited left anterior thoracotomy) as 12 to 15 sequential injections to the mid-LV wall spanning the anterior to posterior intraventricular groove.89,90 At 1-year follow-up, biomaterial treatment was not associated with significant adverse events, supporting the clinical safety of this approach. Moreover, improvements in exercise capacity and a reduction of major adverse cardiac events were observed, although the study was not adequately powered to detect efficacy. Thus, although these clinical findings support the safety of biomaterial IMD, future studies are needed to assess the extent and governing mechanisms of conferred benefits to the patient.

Limitations

The primary limitations of transepicardial delivery as a stand-alone procedure include surgical invasiveness and prolonged postoperative recovery, as well as moderate risks of embolization and arterial injury.91 To prevent injection-induced injury, small caliber needles may be deployed, but this in turn introduces risk of payload damage in the case of cell (ie, MSC) delivery. However, transepicardial delivery is currently primarily considered as an augmentative procedure to an ongoing open-chest procedure, and therefore as deployed introduces acceptable additional risk. Another identified limitation of transepicardial delivery pertains to elderly post-MI patients, who may have a thin LV wall and increased risk for cardiac perforation.

IMD: Transendocardial Route

Overview

TED entails direct payload injection through a needle-tipped catheter positioned by retrograde steering across the aortic valve following percutaneous peripheral artery access. A number of injection catheters are commercially available for TED, including the Helix (BioCardia Inc.)92 and Myostar (Biosense Webster Inc.),93,94 all of which enable some location and mapping of the endocardial surface to facilitate payload targeting. These devices use different approaches to detect and engage with the endocardial surface, including fluoroscopic guidance, ventriculography, and contouring, as well as contact-based electro-tracking. TED is a minimally invasive approach that is becoming increasingly familiar to clinicians, primarily interventional cardiologists, and has been used to deliver an array of cells88 and genes95 to the myocardium for treatment of various forms of cardiovascular disease.

Demonstrated therapeutic potential

TED has been examined in clinical trials to treat HF with reduced ejection fraction, chronic refractory angina with preserved EF, and MI.96 The clinical feasibly of TED is thus well established, with evidence for enhanced myocardial payload retention compared with both systemic intravenous delivery and local ID. Clinical trials examining the effect of bone marrow-derived CD133+ cells in patients with refractory angina concluded that TED was feasible and safe.97, 98, 99 Other studies provide some evidence for the therapeutic efficacy of TED. For example, in a small cohort of patients treated with TED of autologous BMCs, the treatment group (14 patients) showed improved EF at 4 months compared with the control group (7 patients).100 A randomized Phase 3 clinical trial with estimated 250 participants is currently ongoing where bone marrow MSCs are tried with a transendocardial Helix needle following demonstrated safety in Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials in a population of 20 and 30 patients, respectively.4

Limitations

Potential complications with TED include cardiac perforation, stroke, MI, and vascular injury, with evidence for device-specific differences in terms of adverse events.96 Although overall complications rates are under 10% across the reviewed studies, delivery devices comprising rigid helical needles sheathed within a flexible catheter exhibit the lowest rates of serious adverse events (1.1%), suggesting the importance of improved steering and enhanced tactility conferred by these devices. However, past reporting of procedure times and postprocedure outcomes is inconsistent and infrequent, preventing clinical consensus about the risk of TED and future directions for advanced device design. Although clinical trials suggest the feasibility and safety of TED, the therapeutic efficacy of this approach is comparatively less established. For example, TED of autologous BMCs to treat severe ischemic heart disease and LV dysfunction did not significantly improve LV end-systolic volume, maximal oxygen consumption, or reversibility on single photon emission computed tomography.101 Similarly, past studies report that TED-based cell therapy to treat refractory angina, although proven safe and feasible, did not improve patient quality of life97 or reduce the occurrence of myocardial ischemia and angina versus placebo.98

Summary, Future Directions, and Challenges

Summary of Reviewed Administrative Routes

Catheter- and needle-based payload delivery to the myocardium can be advanced through strategies that leverage various administrative routes, with each route demonstrating clinical potential despite persistent challenges and limitations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary detailing advantages and disadvantages of catheter- and injection-based myocardial delivery strategies

| Delivery route | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Intracoronary delivery |

|

|

| Intrapericardial delivery |

|

|

| Intramyocardial delivery: Transepicardial route |

|

|

| Intramyocardial delivery: Transendocardial route |

|

|

ID is a safe, simple, and familiar method, and while commonly used to treat MI is less suitable for treatment of chronic disease states and cases of severe vascular stenosis. A primary concern with ID is low myocardial payload retention, stimulating the use of a stop–flow technique to control the coronary blood flow environment and promote myocardial payload retention. The delivery of solid-forming injectates via ID introduces additional interventional risks, including loss of vessel patency and embolic formation, and as such this payload class is typically delivered via alternate (direct) routes.

IPD is a promising administrative route to treat the entire myocardium. Although readily accessible in the context of open-chest procedures, the continued advancement of noninvasive IPD strategies is needed to fully exploit the clinical utility of this delivery approach. Limitations of IPD include diminished cardiac site-specificity (compared with other direct local delivery options), the potential for unintended systemic delivery, the need to puncture the pericardium, and compromised access due to low pericardial fluid volume.

For preclinical studies using direct IMD, the transepicardial route is a commonly deployed method, and as such momentum is building for new technologies to enhance the translation of this approach. In addition to direct injections into the myocardium, biomaterial implantation/epicardial spraying are alternative methods for local myocardial delivery via the epicardial route. Direct IMD has been shown to be effective in terms of achieving therapeutic payload concentrations, minimizing off-target payload accumulation, and enabling surgical mitigation of intra-procedural risk factors including perforations and hemorrhage.

TED is the alternative approach for direct IMD, with demonstrated clinical feasibility for a broad range of cardiac therapies. The efficacy of TED-based therapies is less well established, although studies report that payload retention within the myocardium is superior with TED in comparison to systemic and local intravenous injections. Although generally safe for clinical implementation, device-specific differences in the occurrence of adverse events coupled with inconsistent clinical reporting on procedural outcomes limits the understanding of the risk associated with TED.

In comparison to these (and other) current delivery options, increasingly successful strategies will be less invasive, more efficient, highly targeted, and readily amenable to a wide range of therapeutic payloads, including biomaterial-based therapies. Given the recognized criteria and the comparative performance of current delivery strategies, it is likely that future transformative approaches will adopt a direct IMD route, with technological advancements that minimize procedural invasiveness and enable enhanced surface mapping and precise spatiotemporal control of injections with a targeted volume and myocardial depth.

Future Directions for IMD

Direct IMD has the inherent advantage of circumventing the coronary circulation and therefore mitigating embolic risk, but the obvious drawback of requiring direct access to the myocardium either via a transepicardial or transendocardial approach. Of these 2 options, the TED approach has generated the greatest interest from the medical industry because it can be implemented in a percutaneous procedure, resulting in a variety of TED devices currently in use. However, despite efforts to improve device steering and endocardial mapping, the fundamental challenge of catheter navigation within the dynamic environment of the LV chamber and controlled engagement with the endocardial surface remain limiting factors.

Alternatively, direct IMD via the transepicardial route requires open-chest surgical access to the epicardial surface and is therefore currently not feasible as a stand-alone procedure. However, it has been demonstrated in an experimental setting that this mode of IMD confers highly controllable injections into easily visualized target surfaces.48,50 Preclinical studies have shown that injection site patterning within specific myocardial domains is feasible and beneficial for the delivery of solid biomaterial-based payloads in a post-MI context, broadening the therapeutic potential of localized myocardial delivery.102

IMD is the most viable approach to solid-forming biomaterial injection because it minimizes the inherent risk of biomaterial introduction into the coronary circulation and thus embolic development and vessel occlusion. Biomaterial injections, which can be delivered either alone or in conjunction with bioactive agents, are gained increasing attention as payload systems with sustained delivery capabilities due to their biophysical properties in-situ. Moreover, in addition to the potential to better control and protract the residence time of incorporated small molecules within targeted myocardial territories, biomaterial-based approaches potentiate a fundamentally different cardiac treatment mechanism. It is becoming increasingly understood that biomaterial injections can alter the local geometry and mechanical behavior/properties of the myocardium and insomuch alter the mechanical performance of the heart.103 Building on the general concept of controlling cardiac mechanics to attenuate HF progression (ie, with wraps, meshes, and cardiac patches), these and other studies suggest that localized biomaterial injections can alter post-MI myocardial stress/strain patterns in a manner that attenuates adverse LV remodeling.102,103 A clear future direction of IMD is the evolution of strategies to allow minimally invasive implantation of solid-forming biomaterials with specific mechanical properties, bulk degradation/erosion rates, payload release rates, and in strategic spatial patterns, where these variables can be tuned for specific clinical scenarios.

The Technological Gap Limiting IMD

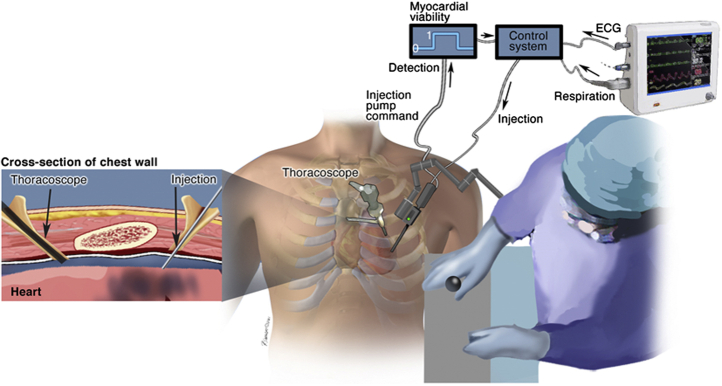

A potential solution to the technological gaps limiting IMD would be an injection system that utilizes the transepicardial route but does so in a closed-chest procedure. Here we envision a semiautomated injection system in which a needle is passed directly through the chest wall and engages with the epicardial surface.104 Such a system would be an extension of robotic cardiac surgery, which has been steadily evolving over the past 20 years, with the transformative feature of enabling cardiac surgeons to engage with the epicardial surface in a closed-chest setting. We envision that such an approach would at minimum demand continuous needle visualization throughout the procedure, exquisite control of needle positioning with respect to the beating heart, and automated payload injection when the needle is at a target myocardial depth. Additional system features may include control of needle position/injection actuation with simultaneously acquired electrocardiogram readings, fiber optic probes to visualize the targeted injection site, and electrosensitive components for discrimination of conducting/nonconducting myocardial regions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Operational schematic of semiautomated system for direct intramyocardial injection in a closed-chest setting.104 Envisioned system components include a robotically controlled needle injection/sensor apparatus that is introduced through the chest wall and positioned near the myocardial surface under the guidance of a cardiac surgeon. Needle position/injection site specification could then be refined/aided by electrical monitoring of myocardial conductivity via an incorporated sensor, with feedback discriminating viable/nonviable myocardium (in a post-myocardial infarct context). A control system would integrate myocardial viability signals with echocardiogram (ECG)/respiratory data to automate small volume (∼100 uL) intramyocardial injection via a positive pump, with synchronization of pump displacement and ECG signal to facilitate control of injection depth.

Conclusions

Strategies for increasingly noninvasive, efficient, and targeted payload delivery to the myocardium will expand the range of available clinical interventions for multiple disease states. The safety and efficacy of catheter- and injection-based approaches have been established in multiple clinical scenarios, but challenges and risks remain. Although iterative advancements in enabling technologies will progressively improve outcomes with the considered delivery routes, novel methods for direct intramyocardial delivery of solid biomaterial-based payloads could be a transformative step in cardiac therapy.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they have a conflict of interest. the doctors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant R01HL130972-01A1 as well as a Merit Award from the Veterans Health Administration (no. BX000168-10A1) to Dr Spinale.

References

- 1.Haley K.E., Almas T., Shoar S., Shaikh S., Azhar M., Cheema F.H., et al. The role of anti-inflammatory drugs and nanoparticle-based drug delivery models in the management of ischemia-induced heart failure. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;142:112014. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rolfes C., Howard S., Goff R., Iaizzo P.A. Localized drug delivery for cardiothoracic surgery, current concepts in general thoracic surgery. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/41321

- 3.Zhang J., Bolli R., Garry D.J., Marban E., Menasche P., Zimmermann W.H., et al. Basic and translational research in cardiac repair and regeneration: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:2092–2105. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kesselheim A.S., Misono A.S., Lee J.L., Stedman M.R., Brookhart M.A., Choudhry N.K., et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2514–2526. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keraliya R.A., Patel C., Patel P., Keraliya V., Soni T.G., Patel R.C., et al. Osmotic drug delivery system as a part of modified release dosage form. ISRN Pharm. 2012;2012:528079. doi: 10.5402/2012/528079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Brakel T.J., Hermans J.J.R., Janssen B.J., van Essen H., Botterhuis N., Smits J.F.M., et al. Intrapericardial delivery enhances cardiac effects of sotalol and atenolol. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44:50–56. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landau C., Jacobs A.K., Haudenschild C.C. Intrapericardial basic fibroblast growth factor induces myocardial angiogenesis in a rabbit model of chronic ischemia. Am Heart J. 1995;129:924–931. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mei X., Cheng K. Recent development in therapeutic cardiac patches. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:610364. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.610364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMahan S., Taylor A., Copeland K.M., Pan Z., Liao J., Hong Y. Current advances in biodegradable synthetic polymer based cardiac patches. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2020;108:972–983. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z., Xie M., Wang X., Lv Q., Ding S. Efficient gene delivery to myocardium with ultrasound targeted microbubble destruction and polyethylenimine. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2008;28:613–617. doi: 10.1007/s11596-008-0528-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Low S.S., Lim C.N., Yew M., Chai W.S., Low L.E., Manickam S., et al. Recent ultrasound advancements for the manipulation of nanobiomaterials and nanoformulations for drug delivery. Ultrason Sonochem. 2021;80:105805. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wehman B., Siddiqui O., Jack G., Vesely M., Li T., Mishra R., et al. Intracoronary stem cell delivery to the right ventricle: a preclinical study. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;28:817–824. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Slochteren F.J., van Es R., Gyöngyösi M., van der Spoel T.I.G., Koudstaal S., Leiner T., et al. Three dimensional fusion of electromechanical mapping and magnetic resonance imaging for real-time navigation of intramyocardial cell injections in a porcine model of chronic myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;32:833–843. doi: 10.1007/s10554-016-0852-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Formigli L., Perna A.M., Meacci E., Cinci L., Margheri M., Nistri S., et al. Paracrine effects of transplanted myoblasts and relaxin on post-infarction heart remodelling. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:1087–1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagikura K., Fukuda N., Yokoyama S., Yuxin L., Kusumi Y., Matsumoto T., et al. Low invasive angiogenic therapy for myocardial infarction by retrograde transplantation of mononuclear cells expressing the VEGF gene. Int J Cardiol. 2010;142:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.12.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong S.J., Hou D., Brinton T.J., Johnstone B., Feng D., Rogers P., et al. Intracoronary and retrograde coronary venous myocardial delivery of adipose-derived stem cells in swine infarction lead to transient myocardial trapping with predominant pulmonary redistribution. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83:E17–E25. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou D., Youssef E.A., Brinton T.J., Zhang P., Rogers P., Price E.T., et al. Radiolabeled cell distribution after intramyocardial, intracoronary, and interstitial retrograde coronary venous delivery: implications for current clinical trials. Circulation. 2005;112(9 Suppl):I150–I156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.526749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu F., Zhao X., Wu J., Cui Y., Mao Y., Chen K., et al. MSCs transfected with hepatocyte growth factor or vascular endothelial growth factor improve cardiac function in the infarcted porcine heart by increasing angiogenesis and reducing fibrosis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2524–2532. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prifti E., Di Lascio G., Harmelin G., Bani D., Briganti V., Veshti A., et al. Cellular cardiomyoplasty into infracted swine's hearts by retrograde infusion through the venous coronary sinus: an experimental study. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato T., Iso Y., Uyama T., Kawachi K., Wakabayashi K., Omori Y., et al. Coronary vein infusion of multipotent stromal cells from bone marrow preserves cardiac function in swine ischemic cardiomyopathy via enhanced neovascularization. Lab Invest. 2011;91:553–564. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vicario J., Piva J., Pierini A., Ortega H.H., Canal A., Gerardo L., et al. Transcoronary sinus delivery of autologous bone marrow and angiogenesis in pig models with myocardial injury. Cardiovasc Radiat Med. 2002;3:91–94. doi: 10.1016/s1522-1865(03)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokoyama S., Fukuda N., Li Y., Hagikura K., Takayama T., Kunimoto S., et al. A strategy of retrograde injection of bone marrow mononuclear cells into the myocardium for the treatment of ischemic heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel A.N., Mittal S., Turan G., Winters A.A., Henry T.D., Ince H., et al. REVIVE trial: retrograde delivery of autologous bone marrow in patients with heart failure. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:1021–1027. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva S.A., Sousa A.L., Haddad A.F., Azevedo J.C., Soares V.E., Peixoto C.M., et al. Autologous bone-marrow mononuclear cell transplantation after acute myocardial infarction: comparison of two delivery techniques. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:343–352. doi: 10.3727/096368909788534951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuma J., Carrasco A., Castillo J., Cruz C., Carrillo A., Ercilla J., et al. RESCUE-HF trial: retrograde delivery of allogeneic umbilical cord lining subepithelial cells in patients with heart failure. Cell Transplant. 2016;25:1713–1721. doi: 10.3727/096368915X690314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuma J., Fernandez-Vina R., Carrasco A., Castillo J., Cruz C., Carrillo A., et al. Safety and feasibility of percutaneous retrograde coronary sinus delivery of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation in patients with chronic refractory angina. J Transl Med. 2011;9:183. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vicario J., Campos C., Piva J., Faccio F., Gerardo L., Becker C., et al. Transcoronary sinus administration of autologous bone marrow in patients with chronic refractory stable angina Phase 1. Cardiovasc Radiat Med. 2004;5:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.carrad.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vicario J., Campo C., Piva J., Faccio F., Gerardo L., Becker C., et al. One-year follow-up of transcoronary sinus administration of autologous bone marrow in patients with chronic refractory angina. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2005;6:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gathier W.A., van Ginkel D.J., van der Naald M., van Slochteren F.J., Doevendans P.A., Chamuleau S.A.J., et al. Retrograde coronary venous infusion as a delivery strategy in regenerative cardiac therapy: an overview of preclinical and clinical data. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2018;11:173–181. doi: 10.1007/s12265-018-9785-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodenberg E.J., Patel D.S., Shirley B., Young B.W., Taylor A.F., Steidinger H.R., et al. Catheter-based retrograde coronary sinus infusion is a practical delivery technique for introducing biological molecules into the cardiac system. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;94:669–676. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowan D.B., Yao R., Akurathi V., Snay E.R., Thedsanamoorthy J.K., Zurakowski D., et al. Intracoronary delivery of mitochondria to the ischemic heart for cardioprotection. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherman W., Martens T.P., Viles-Gonzalez J.F., Siminiak T. Catheter-based delivery of cells to the heart. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006;3(Suppl 1):S57–S64. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carvalho E., Verma P., Hourigan K., Banerjee R. Myocardial infarction: stem cell transplantation for cardiac regeneration. Regen Med. 2015;10:1025–1043. doi: 10.2217/rme.15.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher S.A., Zhang H., Doree C., Mathur A., Martin-Rendon E. Stem cell treatment for acute myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD006536. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006536.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng X.D., Wang X.N., Yuan X.H., Wang W. Effectiveness of biatrial epicardial application of amiodarone-releasing adhesive hydrogel to prevent postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:939–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolderman R.W., Hermans J.J., Rademakers L.M., de Jong M.M.J., Bruin P., Dias A.A., et al. Epicardial application of an amiodarone-releasing hydrogel to suppress atrial tachyarrhythmias. Int J Cardiol. 2011;149:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laham R.J., Rezaee M., Post M., Xu X., Sellke F.W. Intrapericardial administration of basic fibroblast growth factor: myocardial and tissue distribution and comparison with intracoronary and intravenous administration. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;58:375–381. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajanayagam M.A., Shou M., Thirumurti V., Lazarous D.F., Quyyumi A.A., Goncalves L., et al. Intracoronary basic fibroblast growth factor enhances myocardial collateral perfusion in dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:519–526. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah A.S., Lilly R.E., Kypson A.P., Tai O., Hata J.A., Pippen A., et al. Intracoronary adenovirus-mediated delivery and overexpression of the beta(2)-adrenergic receptor in the heart: prospects for molecular ventricular assistance. Circulation. 2000;101:408–414. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.4.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang S., Yang Y.J., Li C.J., Gao R.L. Effects of intracoronary autologous bone marrow cells on left ventricular function in acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis for randomized controlled trials. Coron Artery Dis. 2008;19:327–335. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e328300dbd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Spoel T.I.G., Vrijsen K.R., Koudstaal S., Sluijter J.P.G., Nijsen J.F.W., de Jong H.W., et al. Transendocardial cell injection is not superior to intracoronary infusion in a porcine model of ischaemic cardiomyopathy: a study on delivery efficiency. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:2768–2776. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vrtovec B., Poglajen G., Lezaic L., Sever M., Socan A., Domanovic D., et al. Comparison of transendocardial and intracoronary CD34+ cell transplantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2013;128(11 Suppl 1):S42–S49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuethe F., Richartz B.M., Kasper C., Sayer H.G., Hoeffken K., Werner G.S., et al. Autologous intracoronary mononuclear bone marrow cell transplantation in chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy in humans. Int J Cardiol. 2005;100:485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Musialek P., Tekieli L., Kostkiewicz M., Miszalski-Jamka T., Klimeczek P., Mazur W., et al. Infarct size determines myocardial uptake of CD34+ cells in the peri-infarct zone: results from a study of (99m)Tc-extametazime-labeled cell visualization integrated with cardiac magnetic resonance infarct imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:320–328. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.979633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tous E., Purcell B., Ifkovits J.L., Burdick J.A. Injectable acellular hydrogels for cardiac repair. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2011;4:528–542. doi: 10.1007/s12265-011-9291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reis L.A., Chiu L.L., Feric N., Fu L., Radisic M. Biomaterials in myocardial tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016;10:11–28. doi: 10.1002/term.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shuman J.A., Zurcher J.R., Sapp A.A., Burdick J.A., Gorman R.C., Gorman J.H., III, et al. Localized targeting of biomaterials following myocardial infarction: a foundation to build on. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2013;23:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodell C.B., Lee M.E., Wang H., Takebayashi S., Takayama T., Kawamura T., et al. Injectable shear-thinning hydrogels for minimally invasive delivery to infarcted myocardium to limit left ventricular remodeling. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e004058. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.116.004058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi H., Wang C., Ma Z. Stimuli-responsive biomaterials for cardiac tissue engineering and dynamic mechanobiology. APL Bioeng. 2021;5:011506. doi: 10.1063/5.0025378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Purcell B.P., Barlow S.C., Perreault P.E., Freeburg L., Doviak H., Jacobs J., et al. Delivery of a matrix metalloproteinase-responsive hydrogel releasing TIMP-3 after myocardial infarction: effects on left ventricular remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;315:H814–H825. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00076.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ernst S., Sanchez-Quintana D., Ho S.Y. Anatomy of the pericardial space and mediastinum: relevance to epicardial mapping and ablation. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2010;2:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccep.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hou D., March K.L. A novel percutaneous technique for accessing the normal pericardium: a single-center successful experience of 53 porcine procedures. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003;15:13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seferovic P.M., Ristic A.D., Maksimovic R., Petrovic P., Ostojic M., Simeunovic S., et al. Initial clinical experience with PerDUCER device: promising new tool in the diagnosis and treatment of pericardial disease. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22(1 Suppl 1):I30–I35. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960221309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rupp H., Rupp T.P., Alter P., Jung N., Pankuweit S., Maisch B. Intrapericardial procedures for cardiac regeneration by stem cells: need for minimal invasive access (AttachLifter) to the normal pericardial cavity. Herz. 2010;35:458–465. doi: 10.1007/s00059-010-3382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tucker-Schwartz J.M., Gillies G.T., Scanavacca M., Sosa E., Mahapatra S. Pressure-frequency sensing subxiphoid access system for use in percutaneous cardiac electrophysiology: prototype design and pilot study results. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2009;56:1160–1168. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2008.2009527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Filgueira C.S., Igo S.R., Wang D.K., Hirsch M., Schulz D.G., Bruckner B.A., et al. Technologies for intrapericardial delivery of therapeutics and cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;151-152:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laham R.J., Hung D., Simons M. Therapeutic myocardial angiogenesis using percutaneous intrapericardial drug delivery. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22(1 Suppl 1):I6–I9. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960221305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Brakel T.J., Hermans J.J., Accord R.E., Schotten U., Smits J.F., Allessie M.A., et al. Effects of intrapericardial sotalol and flecainide on transmural atrial electrophysiology and atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:207–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Labhasetwar V., Levy R.J. Novel delivery of antiarrhythmic agents. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;29:1–5. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199529010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fei L., Baron A.D., Henry D.P., Zipes D.P. Intrapericardial delivery of L-arginine reduces the increased severity of ventricular arrhythmias during sympathetic stimulation in dogs with acute coronary occlusion: nitric oxide modulates sympathetic effects on ventricular electrophysiological properties. Circulation. 1997;96:4044–4049. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.11.4044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ayers G.M., Rho T.H., Ben-David J., Besch H.R., Jr., Zipes D.P. Amiodarone instilled into the canine pericardial sac migrates transmurally to produce electrophysiologic effects and suppress atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1996;7:713–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1996.tb00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tomkowski W.Z., Gralec R., Kuca P., Burakowski J., Orłowski T., Kurzyna M. Effectiveness of intrapericardial administration of streptokinase in purulent pericarditis. Herz. 2004;29:802–805. doi: 10.1007/s00059-004-2655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Willerson J.T., Igo S.R., Yao S.K., Ober J.C., Macris M.P., Ferguson J.J. Localized administration of sodium nitroprusside enhances its protection against platelet aggregation in stenosed and injured coronary arteries. Tex Heart Inst J. 1996;23:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miyazaki T., Pride H.P., Zipes D.P. Modulation of cardiac autonomic neurotransmission by epicardial superfusion. Effects of hexamethonium and tetrodotoxin. Circ Res. 1989;65:1212–1219. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miyazaki T., Zipes D.P. Pericardial prostaglandin biosynthesis prevents the increased incidence of reperfusion-induced ventricular fibrillation produced by efferent sympathetic stimulation in dogs. Circulation. 1990;82:1008–1019. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.3.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miyazaki T., Pride H.P., Zipes D.P. Prostaglandins in the pericardial fluid modulate neural regulation of cardiac electrophysiological properties. Circ Res. 1990;66:163–175. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marcano J., Campos K., Rodriguez V., Handy K., Brewer M.A., Cohn W.E. Intrapericardial delivery of amiodarone rapidly achieves therapeutic levels in the atrium. Heart Surg Forum. 2013;16:E279–E286. doi: 10.1532/hsf98.2013188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lazarous D.F., Shou M., Stiber J.A., Hodge E., Thirumurti V., Gonçalves L., et al. Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer induces sustained pericardial VEGF expression in dogs: effect on myocardial angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;44:294–302. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spodick D.H. Microphysiology of the pericardium in relation to intrapericardial therapeutics and diagnostics. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22(1 Suppl 1):I2–I3. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960221303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boulanger B., Yuan Z., Flessner M., Hay J., Johnston M. Pericardial fluid absorption into lymphatic vessels in sheep. Microvasc Res. 1999;57:174–186. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1998.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laham R.J., Sellke F.W., Edelman E.R., Pearlman J.D., Ware J.A., Brown D.L., et al. Local perivascular delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor in patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery. Results of a phase I randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation. 1999;100:1865–1871. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.18.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang W., Mei Y.Q., Yuan X.H., Feng X.D. Clinical efficacy of epicardial application of drug-releasing hydrogels to prevent postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garcia J.R., Campbell P.F., Kumar G., Langberg J.J., Cesar L., Deppen J.N., et al. Minimally invasive delivery of hydrogel-encapsulated amiodarone to the epicardium reduces atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11:e006408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sultana N., Magadum A., Hadas Y., Kondrat J., Singh N., Youssef E., et al. Optimizing cardiac delivery of modified mRNA. Mol Ther. 2017;25:1306–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamamoto H., Gorman J.H., III, Ryan L.P., Hinmon R., Martens T.P., Schuster M.D., et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal precursor cell therapy to limit remodeling after myocardial infarction: the effect of cell dosage. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gorman R.C., Jackson B.M., Burdick J.A., Gorman J.H. Infarct restraint to limit adverse ventricular remodeling. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2011;4:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9244-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pendyala L., Goodchild T., Gadesam R.R., Chen J., Robinson K., Chronos N., et al. Cellular cardiomyoplasty and cardiac regeneration. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2008;4:72–80. doi: 10.2174/157340308784245748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toma C., Pittenger M.F., Cahill K.S., Byrne B.J., Kessler P.D. Human mesenchymal stem cells differentiate to a cardiomyocyte phenotype in the adult murine heart. Circulation. 2002;105:93–98. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chiu R.C., Zibaitis A., Kao R.L. Cellular cardiomyoplasty: myocardial regeneration with satellite cell implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:12–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nakamura K., Neidig L.E., Yang X., Weber G.J., El-Nachef D., Tsuchida H., et al. Pharmacologic therapy for engraftment arrhythmia induced by transplantation of human cardiomyocytes. Stem. Cell Rep. 2021;16:2473–2487. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.He L., Chen X. Cardiomyocyte induction and regeneration for myocardial infarction treatment: cell sources and administration strategies. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9:e2001175. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202001175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamada Y., Wang X.D., Yokoyama S.I., Fukuda N., Takakura N. Cardiac progenitor cells in brown adipose tissue repaired damaged myocardium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:662–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kanelidis A.J., Premer C., Lopez J., Balkan W., Hare J.M. Route of delivery modulates the efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of preclinical studies and clinical trials. Circ Res. 2017;120:1139–1150. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oskouei B.N., Lamirault G., Joseph C., Treuer A.V., Landa S., Da Silva J., et al. Increased potency of cardiac stem cells compared with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in cardiac repair. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1:116–124. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Quevedo H.C., Hatzistergos K.E., Oskouei B.N., Feigenbaum G.S., Rodriguez J.E., Valdes D., et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells restore cardiac function in chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy via trilineage differentiating capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14022–14027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903201106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schuleri K.H., Feigenbaum G.S., Centola M., Weiss E.S., Zimmet J.M., Turney J., et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells produce reverse remodelling in chronic ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2722–2732. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kudo M., Wang Y., Wani M.A., Xu M., Ayub A., Ashraf M. Implantation of bone marrow stem cells reduces the infarction and fibrosis in ischemic mouse heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1113–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sheng C.C., Zhou L., Hao J. Current stem cell delivery methods for myocardial repair. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:547902. doi: 10.1155/2013/547902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee R.J., Hinson A., Bauernschmitt R., Matschke K., Fang Q., Mann D.L., et al. The feasibility and safety of Algisyl-LVR as a method of left ventricular augmentation in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: initial first in man clinical results. Int J Cardiol. 2015;199:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mann D.L., Lee R.J., Coats A.J., Neagoe G., Dragomir D., Pusineri E., et al. One-year follow-up results from AUGMENT-HF: a multicentre randomized controlled clinical trial of the efficacy of left ventricular augmentation with Algisyl in the treatment of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:314–325. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Raval A.N., Johnston P.V., Duckers H.J., Cook T.D., Traverse J.H., Altman P.A., et al. Point of care, bone marrow mononuclear cell therapy in ischemic heart failure patients personalized for cell potency: 12-month feasibility results from CardiAMP heart failure roll-in cohort. Int J Cardiol. 2021;326:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.de la Fuente L.M., Stertzer S.H., Argentieri J., Peñaloza E., Miano J., Koziner B., et al. Transendocardial autologous bone marrow in chronic myocardial infarction using a helical needle catheter: 1-year follow-up in an open-label, nonrandomized, single-center pilot study (the TABMMI study) Am Heart J. 2007;154:79.e1–79.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gepstein L., Hayam G., Ben-Haim S.A. A novel method for nonfluoroscopic catheter-based electroanatomical mapping of the heart. In vitro and in vivo accuracy results. Circulation. 1997;95:1611–1622. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.6.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ben-Haim S.A., Osadchy D., Schuster I., Gepstein L., Hayam G., Josephson M.E. Nonfluoroscopic, in vivo navigation and mapping technology. Nat Med. 1996;2:1393–1395. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kornowski R., Fuchs S., Leon M.B., Epstein S.E. Delivery strategies to achieve therapeutic myocardial angiogenesis. Circulation. 2000;101:454–458. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.4.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Raval A.N., Pepine C.J. Clinical safety profile of transendocardial catheter injection systems: a plea for uniform reporting. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;22:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jadczyk T., Ciosek J., Michalewska-Wludarczyk A., Szot W., Parma Z., Ochala B., et al. Effects of trans-endocardial delivery of bone marrow-derived CD133+ cells on angina and quality of life in patients with refractory angina: a sub-analysis of the REGENT-VSEL trial. Cardiol J. 2018;25:521–529. doi: 10.5603/CJ.2018.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wojakowski W., Jadczyk T., Michalewska-Włudarczyk A., Parma Z., Markiewicz M., Rychlik W., et al. Effects of transendocardial delivery of bone marrow-derived CD133+ cells on left ventricle perfusion and function in patients with refractory angina: final results of randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled REGENT-VSEL Trial. Circ Res. 2017;120:670–680. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jimenez-Quevedo P., Gonzalez-Ferrer J.J., Sabate M., Garcia-Moll X., Delagado-Bolton R., Llorente L., et al. Selected CD133⁺ progenitor cells to promote angiogenesis in patients with refractory angina: final results of the PROGENITOR randomized trial. Circ Res. 2014;115:950–960. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Perin E.C., Dohmann H.F., Borojevic R., Silva S.A., Sousa A.L.S., Mesquita C.T., et al. Transendocardial, autologous bone marrow cell transplantation for severe, chronic ischemic heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:2294–2302. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070596.30552.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Perin E.C., Willerson J.T., Pepine C.J., Henry T.D., Ellis S.G., Zhao D.X.M., et al. Effect of transendocardial delivery of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells on functional capacity, left ventricular function, and perfusion in chronic heart failure: the FOCUS-CCTRN trial [published correction appears in. JAMA. 2012;307:1717–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mukherjee R., Zavadzkas J.A., Saunders S.M., McLean J.E., Jeffords L.B., Beck C., et al. Targeted myocardial microinjections of a biocomposite material reduces infarct expansion in pigs. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1268–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li D.S., Avazmohammadi R., Rodell C.B., Hsu E.W., Burdick J.A., Gorman J.H., III, et al. How hydrogel inclusions modulate the local mechanical response in early and fully formed post-infarcted myocardium. Acta Biomater. 2020;114:296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Spinale F.G., Shazly T., Ahmadi D.A., Trainor H. Minimally invasive and semi-automated myocardial injection device. http://techfinder.sc.edu/technology/43747