Abstract

Objectives

Atrioventricular conductions disturbances, requiring permanent pacemaker implantation (PPI), represent a potential complication after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), However, little is known about the pacemaker dependency after PPI in this patient setting. This systematic review analyses the incidence of PPI, the short-term (1-year) pacing dependency, and predictors for such a state after TAVI.

Methods

We performed a systematic search in PUBMED, EMBASE, and MEDLINE to identify potentially relevant literature investigating PPI requirement and dependency after TAVI. Study data, patients, and procedural characteristics were extracted. Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals were extracted.

Results

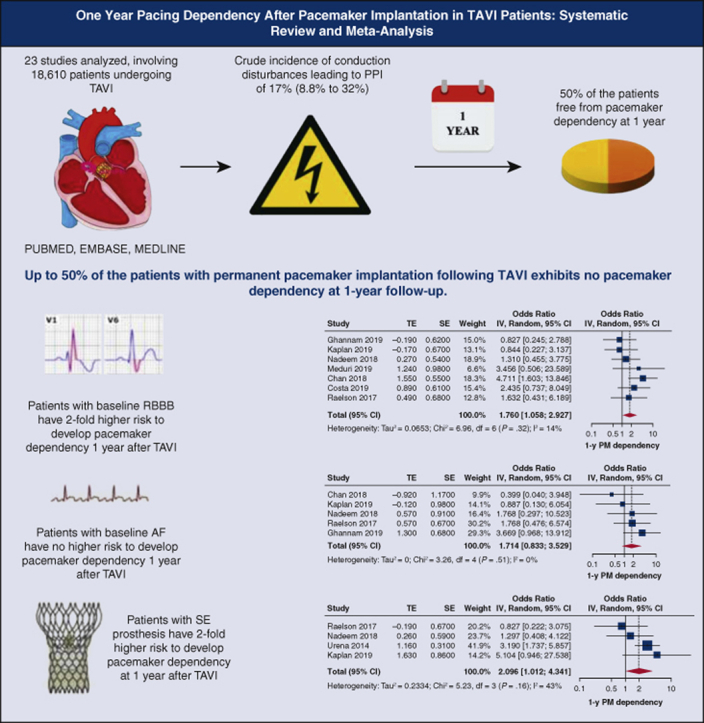

Data from 23 studies were obtained that included 18,610 patients. The crude incidence of PPI after TAVI was 17% (range, 8.8%-32%). PPI occurred at a median time of 3.2 days (range, 0-30 days). Pacing dependency at 1-year was 47.5% (range, 7%-89%). Self-expandable prosthesis (pooled OR was 2.14 [1.15-3.96]) and baseline right bundle branch block (pooled OR was 2.01 [1.06-3.83]) showed 2-fold greater risk to maintain PPI dependency at 1 year after TAVI.

Conclusions

Although PPI represents a rather frequent event after TAVI, conduction disorders have a temporary nature in almost 50% of the cases with recovery and stabilization after discharge. Preoperative conduction abnormality and type of TAVI are associated with higher PPI dependency at short term.

Key Words: conduction disturbances, pacemaker dependency, permanent pacemaker, transcatheter aortic valve implantation

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AF, atrial fibrillation; BE, balloon-expandable; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PPI, permanent pacemaker implantation; RBBB, right bundle branch block; SE, self-expandable; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation

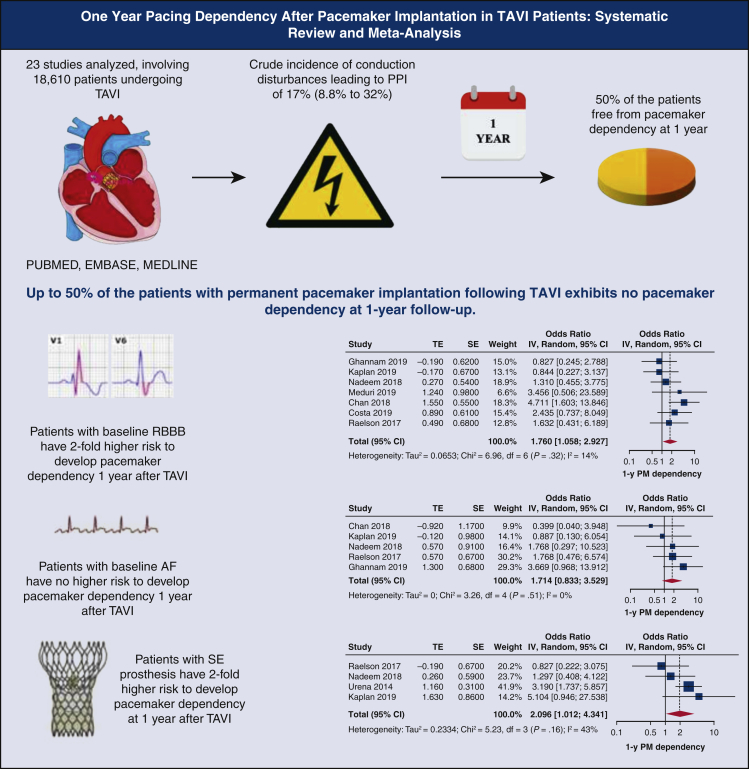

Graphical abstract

Up to 50% of the patients with permanent pacemaker implantation following TAVI exhibits no pacemaker dependency at 1-year follow-up. TAVI, Transcatheter aortic valve implantation; PPI, permanent pacemaker implantation; RBBB, right bundle branch block; TE, log odds ratio; SE, standard error; IV, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence limits; PM, pacemaker.

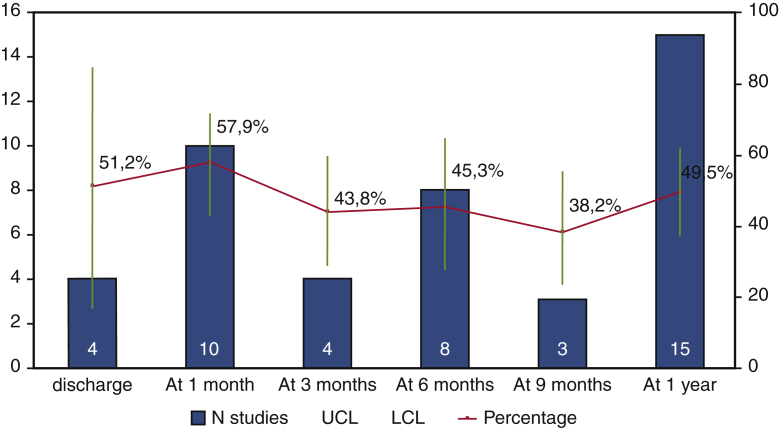

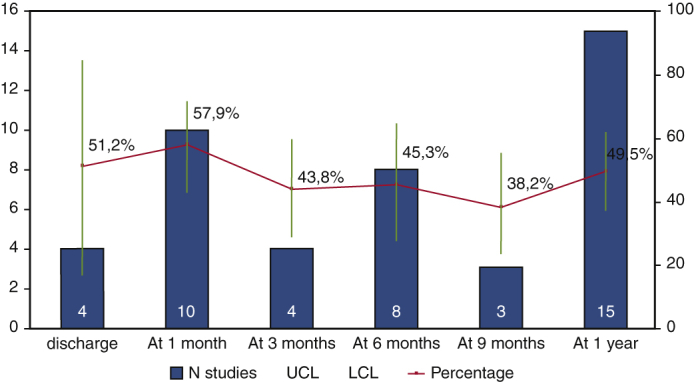

Rate of pacemaker dependency across the time after TAVI.

Central Message.

Up to 50% of the patients with permanent pacemaker implantation following TAVI exhibit no pacemaker dependency at 1-year follow-up.

Perspective.

Better understanding of pacemaker dependency after TAVI should allow better oriented guidelines with respect to indications and timing of pacemaker implantation, as well as postpermanent pacemaker implantation management, based on the high recovery rate of effective native atrio/ventricular conduction.

See Commentaries on pages 56 and 58.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) was first introduced in 20021 as a less-invasive therapeutic option in patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis unfit for cardiac surgery.2 Nowadays, there is a trend to extend these procedures even to intermediate- and low-risk patients, making the frequency of TAVI procedures grow exponentially.3 However, complications, such as atrioventricular conduction disturbances requiring permanent pacemaker implantation (PPI), may diminish the benefit of these procedures: the incidence of PPI after TAVI, for instance, represents a rather frequent event after TAVI.4 Indeed, an association between PPI and all-cause deaths and heart failure rehospitalizations at 1 year from TAVI has been recently shown.5 However, a certain percentage of atrioventricular conduction abnormalities after TAVI may resolve following PPI, even after a few days from implant.6 Presently, the current literature available on pacing dependency after TAVI is limited and based on studies with small patient samples (evidence level B).7,8 Therefore, we performed this systematic review to determine the incidence of PPI, the pacing dependency, and potential predictors for pacing-dependency at 1 year after TAVI procedures.

Methods

Research Strategy

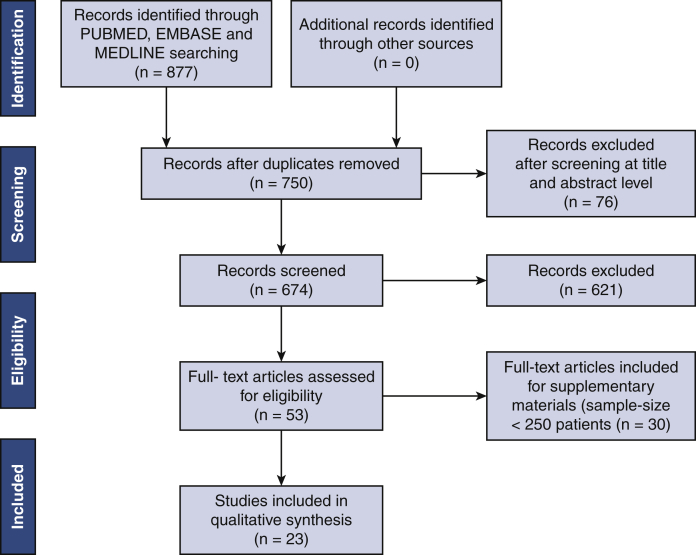

A broad, computerized literature search was performed to identify all relevant studies from PubMed, Embase, and MEDLINE databases. The PubMed database was searched entering the following key words: "Pacemaker, Artificial"[Mesh] OR pacemaker implantation AND "Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement"[Mesh] OR transcatheter aortic valve implantation. We restricted the research to English-language publications. Last access to the database was on April 25, 2020. The search was limited to studies in human recipients. A framework of the systematic review process is plotted in Figure 1, in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Because this study was a systematic review and meta-analysis based on published articles, ethical approval was waived by the institutional review board of the University Hospital of Maastricht.

Figure 1.

Study selection. Flow diagram of included studies based on the Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA).

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

Studies were included in the final analyses if patients were (1) >18 years; (2) >250 patients were included in the main analysis, to provide data interpretation of the most consistent clinical series; and (3) studies provided a definition of cardiac pacemaker dependency. Other studies following the same criteria, but having a smaller patient sample size (<250 patients), were included in a separated analysis (secondary analysis) and are provided in Appendix E1. Multiple publications from a single center were managed to include the last publication. If the same authors published more studies with the same series, the largest patient cohort was included. Studies were excluded if 1 of the following criteria was present: (1) presence of congenital pathology; (2) patients undergoing noncardiac surgery procedures or transcatheter procedure or heart transplantation; (3) no information provided about PPI; (4), publication before year 2002; or (5) outcomes not clearly reported or impossible to extract or calculate from the available results. Review, clinical update, and case reports were not taken into account. All potentially relevant studies were reviewed in detail to check their adhesion to the inclusion criteria. Title and abstracts of all retrieved paper were independently reviewed by 2 researchers (J.R. and M.D.M.) to identify studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Controversial findings were solved by the intervention of a third reviewer (R.L.). The quality of included studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for observational studies by 2 investigators independently (J.R. and M.D.M.).

Data Extraction

Microsoft Office Excel 2016 (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash) was used for data extraction that was performed independently by 2 researchers (K.V., L.V.). Year of publication, study design, sample size, age, Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score, inclusion period, left ventricular ejection fraction, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, valve type, follow-up, approach for TAVI, indications for PPI, timing of PPI (days), PPI rate, dependency definition, dependency follow-up (months), multivariable predictors of PPI, and PPI-related complications were extracted.

Statistical Analysis

The primary end point was 1-year pacing dependency, defined in different ways. Calculation of proportions of PM dependency at different time points was obtained using a meta-analytic approach by means of metaprop function of meta package in R (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were extracted. We calculated the I2 statistics (0% ∼ 100%) to explain the between-study heterogeneity, with I2 ≤ 25% suggesting more homogeneity, 25% < I2 ≤ 75% suggesting moderate heterogeneity, and I2 > 75% suggesting high heterogeneity. If the null hypothesis was rejected, a random effects model was used to calculate pooled effect estimates. If the null hypothesis was not rejected, a fixed-effects model was used to calculate pooled effect estimates; 95% CI was also reported. Forest plots were used to plot the effect size, either for each study or overall.

Publication bias was evaluated by graphical inspection of funnel plot; estimation of publication bias was performed with trim-and-fill method and quantified by means of Egger's linear regression test. On-leave out study analysis was performed as sensitivity analysis in case of moderate or high heterogeneity. Meta-regression was performed to test the influence of age, time of pacemaker implantation, and sample size. The software used for the analyses was R-studio (meta package), version 1.1.463 (2009-2018).

Results

Study Selection

A total of 877 records were initially screened at the title and abstract level, with 801 papers fully reviewed for eligibility. There were no duplicate data. Ultimately, 23 studies were identified and provided data for the research analysis.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 An additional 30 studies are considered in Appendix E1 because of their limited sample size (<250 patients). The flowsheet for selection of included studies is represented in Figure 1. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale confirmed a high-quality level for all studies included in the main analysis (Table E1).

Study, Participants, and Procedural Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of selected studies are represented in Table 1. Studies were published between 2014 and 2019, and patient recruitment occurred between January 2005 and February 2018; 26% of them (n = 6) were prospective,9,16,18,27,29,31 and the remaining studies were all retrospective observational. Mean duration of follow-up was 16 months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of studies including >250 patients (n = 23)

| Study | Year | Study design (no. centers) | Sample size | Age, y | STS score, % | Inclusion period | Left ventricle ejection fraction, % | Peripheral vascular disease, % | Diabetes mellitus, % | Valve type | Follow-up, mo∗ | Approach for TAVI | Mortality at 30 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjerre Thygesen et al9 | 2014 | Prospective (1) | 258 | na | na | na | na | na | na | 100% SE | na | na | na |

| Urena et al10 | 2014 | Retrospective (8) | 1556 | 80.5 | 7.5 | January 2005 to February 2013 | 55.5 | na | 31.1 | 55.1% BE 44.9% SE |

22 | na | 7% |

| Nazif et al11 | 2015 | Retrospective (21) | 1973 | 84.5 | 11.4 | May 2007 to September 2011 | 53.7 | 42.4 | 36 | 100% BE | 12 | na | 6.6% |

| Van Gils et al12 | 2017 | Retrospective (4) | 306 | 83 | 6.3 | May 2008 to February 2016 | na | 22 | 30 | 38.2% SE 34.7% SE 27.1% ME |

12 | na | 7% |

| Raelson et al13 | 2017 | Retrospective (1) | 578 | 85.5 | na | March 2009 to December 2014 | na | na | na | 21% SE 79% BE |

1 | na | na |

| Dumonteil et al14 | 2017 | Retrospective (14) | 250 | 84 | 6.3 | October 2012 to May 2014 | 58.3 | na | 22.5 | 100% ME | 12 | 100% Transfemoral | 4% |

| Kaplan et al15 | 2019 | Retrospective (1) | 594 | 81.6 | na | January 2011 to December 2017 | na | na | na | na | 12 | na | na |

| Chamandi et al16 | 2018 | Prospective (9) | 1692 | 81.5 | 10.9 | May 2009 to February 2015 | na | na | 33.1 | 50.3% BE 49.7% SE |

48 | na | 42.3% |

| Gaede et al17 | 2018 | Retrospective (1) | 1025 | 81.9 | na | 2010-2015 | na | 21.1 | 33.3 | na | 2.4 | na | na |

| Gonska et al18 | 2018 | Prospective (1) | 612 | 80.4 | 6.5 | February 2014 to September 2016 | 57.5 | na | 29.9 | 58.8% BE 36.7% ME 4.4% SE |

12 | na | 1.3% |

| Marzahn et al19 | 2018 | Retrospective (1) | 856 | 80.5 | na | July 2008 to May 2015 | 57.5 | na | 38 | 37.4% SE 57.8% BE 4.8% ME |

12 | 100% Transfemoral | na |

| Nadeem et al20 | 2018 | Retrospective (1) | 672 | 81.4 | 7.4 | 2011-2017 | 53.8 | 21.5 | 41 | na | 12 | na | na |

| Campelo-Parada et al21 | 2018 | Retrospective (2) | 347 | na | na | May 2010 to December 2015 | 54.6 | na | 37.3 | 100% BE | 1 | 77.8% Transfemoral | na |

| Mirolo et al22 | 2018 | Retrospective (1) | 936 | na | na | October 2009 to January 2017 | na | na | na | 95% BE 5% SE |

2.3 | na | na |

| Van Gils et al23 | 2018 | Retrospective (1) | 291 | 79 | na | January 2012 to December 2015 | na | na | 34 | 42% SE 51.5% BE 6.5% ME |

12 | 94% transfemoral 6% transsubclavian |

5% |

| Takahashi et al24 | 2018 | Retrospective (4) | 1621 | 84.3 | na | January 2010 to December 2014 | na | na | na | 72.5% SE | 13 | na | na |

| Chan et al25 | 2018 | Retrospective (2) | 913 | 81.6 | na | January 2012 to December 2017 | na | na | na | na | 12 | na | na |

| Ghannam et al26 | 2019 | Retrospective (1) | 573 | 79.8 | 6.4 | January 2012 to September 2017 | 57.2 | 45.8 | 37.8 | 100% SE | 17.1 | na | na |

| Costa et al27 | 2019 | Prospective (1) | 1116 | 82 | 4.4 | June 2007 to February 2018 | 53.3 | na | 28.9 | 61.8% SE 27.2% BE 0.5% ME 10.5% Others |

72 | 97% transfemoral 3% others |

3.9% |

| Dolci et al28 | 2019 | Retrospective (1) | 266 | 80 | na | February 2014 to February 2018 | 53 | 22 | 28 | 100% BE | 12 | 84% transfemoral 16% transapical |

na |

| Tovia-Brodie et al29 | 2019 | Prospective (1) | 795 | 82.5 | na | April 2012 to December 2016 | na | na | na | na | 28.2 | na | na |

| Junquera et al30 | 2019 | Retrospective (2) | 676 | 82 | 5 | May 2007 to March 2017 | 57.4 | na | 31.2 | 60.5% BE 35.2% SE 0.7% ME 0.3% others |

12 | 64.8% transfemoral | na |

| Meduri et al31 | 2019 | Prospective (1) | 704 | 82.5 | 6.6 | na | na | 28.2 | 30.9 | 34% SE 66% ME |

12 | na | na |

| Total | na | 79 | 18,610 | 81.8 (43-102) | 7.1 (0.74-34) | January 2005 to February 2018 | 55.6 | 29 | 32.6 | SE 38% BE 46% ME 13.5% others 2.5% |

16 | 88.2% transfemoral 2.3% transapical 0.9% transsubclavian Others 8.7% |

9.6% |

Values are n (%). STS score, Society of Thoracic Surgeons Risk Score; TAVI, transaortic valve implantation; na, not available; SE, self-expandable; BE, balloon-expandable; ME, mechanically expandable.

Follow-up is reported as mean or median as given by the authors.

In total, 18,610 patients were included in 23 studies from 79 centers. The crude incidence of PPI after TAVI procedure was 17%, ranging from 8.8%11 to 32%.14 Preprocedural risk was assessed by the STS score in the majority of the studies (11/23) and the mean STS score was 7.1 (0.74-34). Mean age was 81.8 years (range, 43-102 years). The implanted device was a self-expandable (SE) valve in 38% of patients, a mechanically expandable valve in 13.5%, and a balloon-expandable (BE) in 46% of the patient population. Others devices were used in 2.5% of the patients. Three studies used only BE valves,11,21,28 and 3 studies implanted solely SE valve.9,24,26 The transfemoral access route was preferred (88.2%) over the other approaches (transapical 2.3%; transsubclavian 0.9%, and other approach used in 8.7%). The mortality at 30 days was 9.6%. The baseline characteristics of the studies including <250 patients are provided in Table E2.

PPI Details

The PPI details in studies including >250 patients are reported in Table 2. Data regarding PPI details in studies including <250 patients are described in Table E3. All studies provided indications for PPI, except in 4 series.20,24,25,30 The main indications for PPI were divided into 3 main categories of atrioventricular conduction disorders: atrioventricular block (second and third degree) in 82.7% of the patients, sick sinus syndrome in 2.7%, severe bradycardia in 2.8%, and others indications in 11.8% of the patients, respectively. The timing of PPI varied remarkably among studies, occurring at a median time of 3.2 days (range, 0-30 days) from TAVI procedure. Nine studies didn't provide information about the timing of PPI.9,18, 19, 20, 21,24,25,27,29 The overall incidence of PPI reached 17% of the TAVI patients, ranging from 8.8% to 32% of the cases.

Table 2.

Pacemaker-related details in studies including >250 patients (n = 23)

| Study | Indications for PPI | Timing of PPI, d∗ | PPI rate | Dependency definition | Dependency rate | Dependency follow-up, mo∗ | Multivariable predictors of PPI | Association | PPI-related complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjerre Thygesen et al9 | 100% AVB | na | 27.4% | Resolution of conduction abnormalities | 50% | na | na | na | na |

| Urena et al10 | 75.3% AVB 7.1% SSS 7.9% bradycardia 9.6% others |

3 | 15.4% | “paced rhythm” reported | 66.9% | 12 | na |

|

na |

| Nazif et al11 | 79% AVB 17.3% SSS |

3 | 8.8% | “ventricular pacing” reported | 50.5% | 12 |

|

|

na |

| Van Gils et al12 | 99% AVB 1% SSS |

2 | 41% | % ventricular pacing rhythm reported | 89% | 12 |

|

|

na |

| Raelson et al13 | 82% AVB | 3 | 9% | No intrinsic ventricular activity during pacing at 30 bpm | 39% | 1 | na | na | na |

| Dumonteil et al14 | 88.9% AVB 5.9% others |

3 | 32% | “paced rhythm” reported | 55.4% | 12 |

|

|

na |

| Kaplan et al15 | 79% AVB 21% others |

2,5 | 13.1% | High-grade AVB with a ventricular escape rate of less than 40 beats/min on device interrogation | 21.9% | 12 | na |

|

na |

| Chamandi et al16 | 76.7% AVB 5.6% SSS 3.1% Bradycardia 14.6% others |

2 | 19.8% | 100% right ventricular pacing | 27.4% | 48 | na |

|

na |

| Gaede et al17 | 90% AVB 8% SSS 2% Bradycardia |

4 | 14.7% | Ventricular pacing >95% | 29.5% | 2.4 |

|

Predictors of lack of recovery of AVB

|

na |

| Gonska et al18 | 85.% AVB 10.1% Bradycardia 4.8% others |

na | 24.4% | “ventricular pacing” reported | 30.9% | 1 | na |

|

1.8% reoperation due to lead dislocation 2.4% hematomas/bleeding at the site of the pacemaker |

| Marzahn et al19 | 89% AVB 5.5% Bradycardia 4.1% SSS 1.4% others |

na | 16.9% | “right ventricular pacing %” reported | 55% | 12 | na | na | na |

| Nadeem et al20 | na | na | 21.7% | “right ventricular pacing %” reported | 45.5% | 12 | na |

|

na |

| Campelo-Parada et al21 | 84.3% AVB 9.3% Bradycardia Others 6.2% |

na | 9.2% | Ventricular pacing >1% at 1 mo = AVB resolution | 67.2% | 1 | na |

|

na |

| Mirolo et al22 | 68.8% AVB 30% others |

2,5 | 9.3% | Ventricular pacing ≥ 1% = significant | 75% | 2.9 | na | na | 1.25% endocarditis lead leading to pacemaker explanation 2.5% partial left pneumothorax secondary to subclavian vein puncture 1.25% ventricular lead deplacement |

| Van Gils et al23 | 96% AVB 5% SSS |

5 | 9.3% | Less than 20% ventricular pacing over 6 mo' follow-up | 25% | 6 | na | na | na |

| Takahashi et al24 | na | na | 16.4% | Absence, inadequate intrinsic ventricular rhythm, or ventricular pacing >95% in pacemaker interrogation during follow-up (PPM on VVI 30/min) | 52.8% | 13 | na |

|

na |

| Chan et al25 | na | na | 13.1% | Ventricular pacing reported | 59% | 12 | na | na | 1.6% atrial lead dislodgement 6% ventricular lead dislodgement |

| Ghannam et al26 | 100% AVB | 2,4 | 14% | No recovery of AV nodal conduction if CHB, high-grade AVB, or native ventricular rate <50 beats/min in absence of normal AV conduction | 50% | 12 | na |

|

1.2% (1 patient with right ventricular lead fracture) |

| Costa et al27 | 84.8% AVB 4.1%SSS 11% Others |

na | 13% | Absence of an escape or intrinsic rhythm for 30 s during temporary back-up pacing at a rate of 30 bpm | 33.3% | 12 | na |

|

na |

| Dolci et al28 | 80%AVB 11% Bradycardia 9% others |

4 | 13% | “paced rhythm” reported | 7% | 12 |

|

na | na |

| Tovia-Brodie et al29 | 92% AVB 8% others |

na | 8.8% | No need for ventricular pacing defined as <1% ventricular pacing and intrinsic 1:1 AV conduction with the device programmed to VVI 30 beats per minute | 39% | 28,2 |

|

na | 3.7% tamponade |

| Junquera et al30 | na | 6 | 12.7% | AVB/CHB recovery = ventricular pacing rate <1% | 33.4% | 12 | na | na | na |

| Meduri et al31 | 90% AVB 6% Bradycardia 4% others |

2 | 28.4% | Patients who were symptomatic or did not have a native rhythm + capture of the percentage of paced ventricular beats |

50% | 12 |

|

|

na |

| Total | 82.7% AVB 2.7% SSS 2.8% bradycardia 11.8% Others |

3.2 | 17% | na | na | 11.8 | na | na | na |

Values are n (%). PPI, Pacemaker implantation; AVB, atrioventricular block, na, not available; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; RBBB, right bundle branch block; BMI, body mass index; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; SE, self-expandable; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; PPM, permanent pacemaker; VVI, single-chamber device; DDD, dual-chamber device; AV, atrioventricular; CHB, complete heart block.

Follow-up is reported as mean or median as given by the authors.

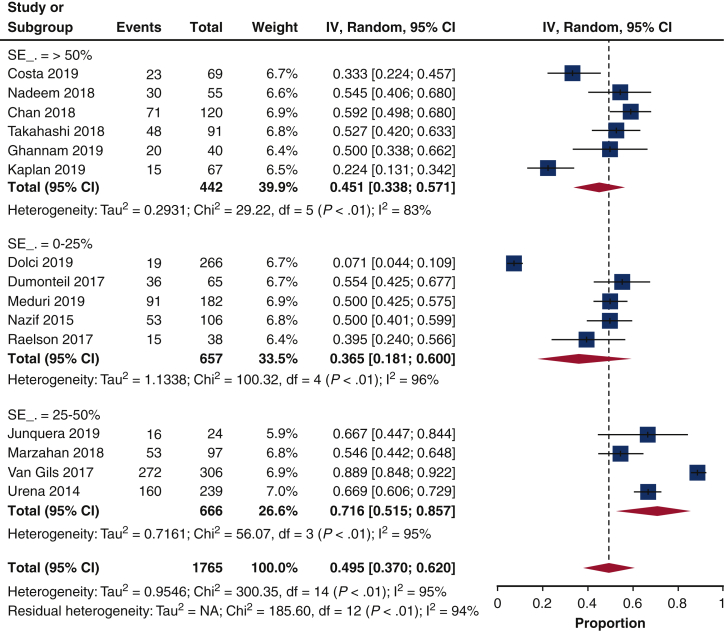

Pacemaker Dependency

There was a large heterogeneity in the assessment and definition of the pacemaker dependency at follow-up. Indeed, 43% of the studies (10/23)10, 11, 12,14,16,18, 19, 20,25,28 reported a right ventricular pacing rhythm as indicator of the pacemaker dependency at follow-up, whereas the remaining studies provided a wide range of pacemaker dependency definitions and evaluation.

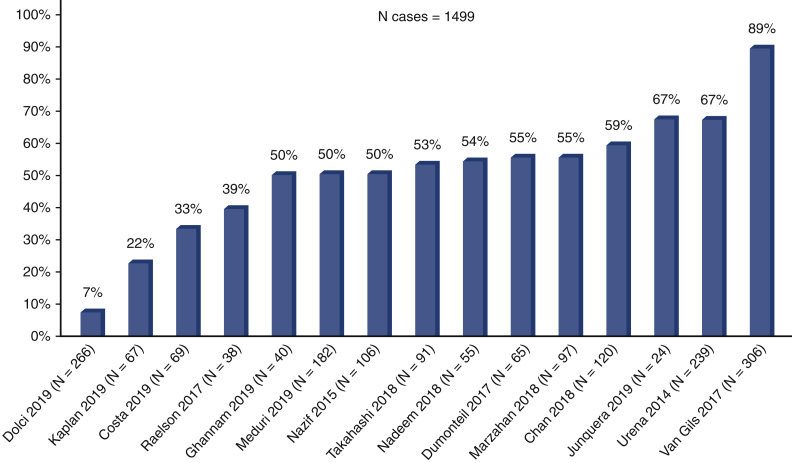

Of the selected 23 articles, the majority (15 studies10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15,19,20,24, 25, 26, 27, 28,30,31) reported the 1-year pacemaker dependency (Figure 2). The pacemaker dependency rate varied across time (Figure 3); it was 51.2% (16.7%-84.6%, n = 4) already at discharge, 57.9% (43.1%-71.3%, n = 10) at 1 month, 45.3%% (27.5%-64.5%, n = 8) at 6 months, and 49.5% (37.1%-61.9%, n = 15) at 1 year.

Figure 2.

Pacemaker dependency at 1 year. Bars represent 1-year pacemaker dependency. The rate of pacemaker dependency ranged from 7% to 89% in individual studies.

Figure 3.

Rate of pacemaker dependency across the time after TAVI. Pooled percentage is reported with 95% confidence limits (blue line). Light blue bars represent number of studies. Yellow line is the interpolation line. UCL, Upper confidence limit; LCL, lower confidence limit.

Influence of Baseline Right Bundle Branch Block (RBBB) and Atrial Fibrillation (AF) on 1-Year Pacemaker Dependency

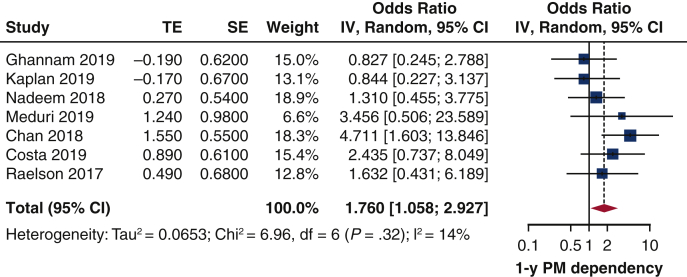

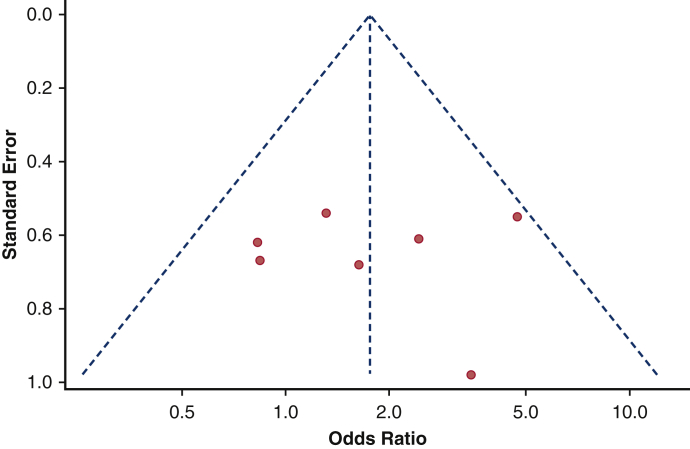

In 6 studies,13,15,20,25,27,31 among 531 patients undergoing pacemaker interrogation at 1 year, pacemaker dependency was present from 22% to 54% of the patients, and the difference between patients with and without baseline RBBB could be analyzed. The pooled OR was 1.76 (95% CI, 1.06-2.93). There was low heterogeneity (I2 = 14%) among the studies (Figure 4), nor was there publication bias (Figure E1). The Egger's test was not significant (P = .90). Leave-one-out study analysis (Table E4), as shown in the paper by Chan and colleagues25 influenced the pooled analysis, since leaving it in, the pooled estimates was not significant anymore. The association between preimplant RBBB and 1-year pacemaker dependency was not influenced by age (r = 0.0917, P = .6050), time of PPI (r = 0.0918, P = .9222), or sample size (r = 0.0920, P = .9245).

Figure 4.

Impact of baseline RBBB on 1-year rate of pacemaker dependency Forest plot. Patients with baseline RBBB have 2-fold greater risk to develop pacemaker dependency 1 year after TAVI. TE, Log odds ratio; SE, standard error; IV, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence limits; PM, pacemaker.

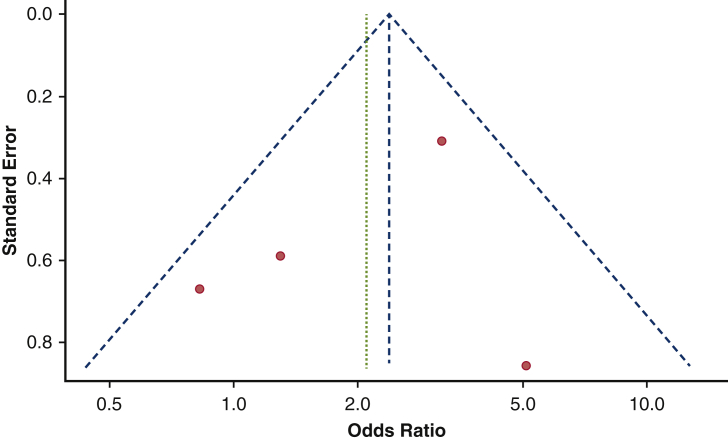

Figure E1.

Funnel plot on the impact of baseline RBBB on 1-year rate of pacemaker dependency. No publication bias was found among studies reporting the influence of baseline RBBB on pacemaker dependency.

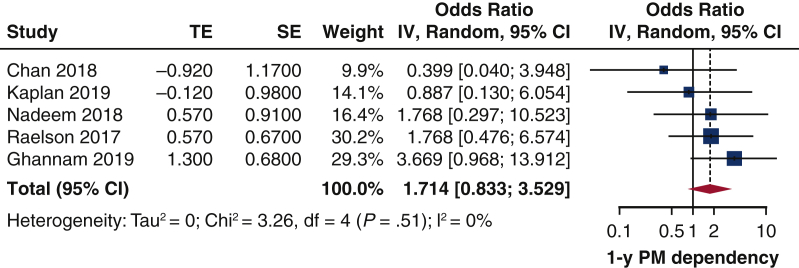

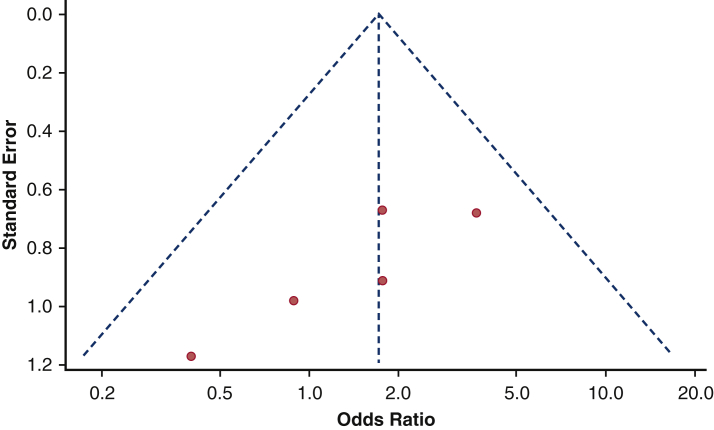

The impact of baseline AF could be investigated in 4 studies13,15,20,25 and revealed no effect on 1-year pacemaker dependency (pooled OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 0.83-3.53) (Figure 5). Again, there was neither heterogeneity among the studies nor publication bias (Figure E2) The Egger's test was not significant (P = .79). On-leave out study analysis (Table E4) confirmed as AF had no impact on pooled analysis.

Figure 5.

Impact of baseline AF on 1-year rate of pacemaker dependency. Forest plot. Patients with baseline AF have no greater risk to develop pacemaker dependency 1 year after TAVI. TE, Log odds ratio; SE, standard error; IV, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence limits; PM, pacemaker.

Figure E2.

Funnel plot on the influence of baseline AF on pacemaker dependency. No publication bias was found among studies reporting the influence of baseline AF on pacemaker dependency.

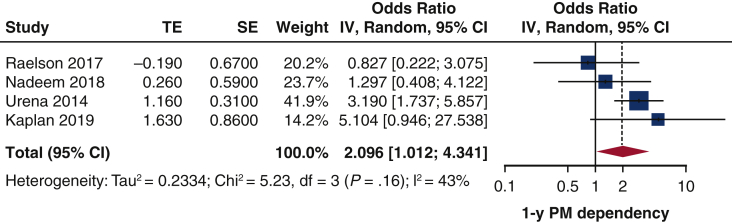

Type of Implanted Prosthesis on 1-Year Pacemaker Dependency

The comparison between SE and BE protheses in terms of 1-year pacemaker dependency could be evaluated in 6studies (796 patients).10,12,13,15,20,24 Patients who received SE prostheses had 2-fold greater risk for pacemaker dependency 1 year after TAVI (Figure 6). moderate heterogeneity was found (I2 = 43%). No publication bias was identified (Figure E3). The Egger's test was not significant (P = .5658). Leave-one-out study analysis (Table E4) showed as the paper by Urena and colleagues10 influenced the pooled analysis, since leaving it, the pooled estimates was not significant anymore. The association between preimplant SE and 1-year pacemaker dependency was not influenced by age (r = 0.1265, P = .5012), time of PPI (r = –1.1506, P = .0.6262), or sample size (r = 0.1123, P = .9812). The pacemaker dependency rate was significantly greater in those studies including more than 50% of SE prostheses (Figure E4).

Figure 6.

Impact of SE prosthesis (vs BE) on 1-year rate of pacemaker dependency. Forest plot. Patients with SE prosthesis have 2-fold greater risk to develop pacemaker dependency at 1 year after TAVI. TE, Log odds ratio; SE, standard error; IV, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence limits; PM, pacemaker.

Figure E3.

Funnel plot on the influence of SE versus BE valves on pacemaker dependency. No publication bias was found among studies reporting the influence of SE versus BE on pacemaker dependency.

Figure E4.

Forest plot pooling pacemaker dependency according to percentage of SE prosthesis included in the study. IV, Weighted mean difference; CI, confidence interval; SE, self-expandable.

Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block and 1-Year Pacemaker Dependency

One-year pacemaker dependency rate was not significantly different between study where pacemaker was implanted due to third-degree atrioventricular block in a rate ranging from70%-79% (41.4%; 26.1%-58.5%), 80%-99% (48.3%; 21.3%-76.5%), and 100% (53.8%, 45.6%-61.7%), P = .427.

Complications and Multivariable Predictors of PPI

Only 5 studies18,22,25,26,29 reported the PPI-related complications. The rate of PPI-related complications ranged from 1.2%26 to 6%.25 The list of various complications is reported in Table 2. Information about predictors of PPI were provided by 7 studies (5319 patients). Pre-existing RBBB was the most frequent determinant factor of PPI. Regarding pacemaker dependency after TAVI at follow-up, multivariable analysis to investigate the predictors was performed in 5 studies: early PPI after TAVI,17 PPI on day 1,27 and larger aortic annular size,26 were found as independent predictor of persistent atrioventricular conduction disturbances. In contrast, 2 studies failed to demonstrate significant predictors for atrioventricular conduction recovery or pacemaker dependency.13,22

Discussion

The main findings of this systematic review regarding PPI and subsequent recovery of atrioventricular conduction or persistent pacemaker dependency in TAVI are as follows (Figure 7): (1) up to 50% of the patients with PPI after TAVI exhibit no pacemaker dependency at 1 year follow-up; (2) patients with baseline RBBB and (3) SE prosthesis have 2-fold greater risk to develop pacemaker dependency 1 year after TAVI; and (4) baseline AF does not influence the risk of pacemaker dependency at 1 year.

Figure 7.

Up to 50% of the patients with permanent pacemaker implantation following TAVI exhibits no pacemaker dependency at 1-year follow-up. TAVI, Transcatheter aortic valve implantation; PPI, permanent pacemaker implantation; RBBB, right bundle branch block; TE, log odds ratio; SE, standard error; IV, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence limits; PM, pacemaker.

Several recent reports show that atrioventricular conduction defects requiring PPI post-TAVI may involve as much as 30% of the treated patients, therefore representing the most frequent complication in such a setting.16 However, nearly 50% of such patients are not pacemaker-dependent at 1-year follow-up, with recovery of atrioventricular conduction occurring even at a very early stage after implant, like before hospital discharge.28 Nonetheless, the range of postimplant pacemaker dependency or effective atrioventricular conduction restoration varies largely, ranging from 7%28 to 89%.12 This wide interval could be explained by heterogeneity and lack of consensus on pacemaker dependency definition. This limitation negatively influenced the study data interpretation in our analysis. Furthermore, pacemaker dependency may intermittently occur, thereby characterizing a different pattern of pacing dependency. This peculiar aspect was not available but might represent an additional factor to be investigated.

In our analysis, patients receiving SE valves and presenting with a preoperative RBBB had a 2-fold greater risk to have persistent pacing dependency at 1 year after TAVI. Ramazzina and colleagues (Table E2) showed that atrioventricular block as indication for PPI was always associated with pacemaker dependency at follow-up. In contrast, Gaede and colleagues17 demonstrated a low rate of long-term persistence of atrioventricular block after TAVI procedure. A few studies address investigate predictors of pacemaker dependency after TAVI. Naveh and colleagues (Table E2) showed that baseline RBBB, long post-TAVI PR interval, and delayed PR interval from baseline were independent predictors for long-term pacemaker dependency. Sharma and colleagues (Table E2) showed that bifascicular block, RBBB, intraprocedural complete heart block, and QRS duration >120 milliseconds were associated with pacemaker dependency at 30-day follow-up. The impact of baseline AF on pacemaker dependency at follow-up is controversial. Early PPI after TAVI procedure was the strongest predictor regarding persistent atrioventricular block and pacemaker dependency, based on large sample-size studies.17,27 According to these findings, we should emphasize that patients without baseline characteristics potentially leading to pacemaker dependency should benefit from other temporary leadless system as Micra AV (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn) to reduce the rate of permanent pacemaker implanted, as the Micra AV system is recently found to be safe; efficient and as performant as transvenous single-chamber pacemaker.32,33

Nowadays, guidelines regarding timing of PPI after TAVI are rather cloudy and not based on thorough clinical investigations.8,34 Due to the lack of consistent data, the dilemma about the appropriate timing for pacemaker implantation after TAVI is left to the discretion of the attending cardiologist according to the different centers' policies and therefore is associated with extreme variability in clinical management. Erkapic and colleagues35 showed that atrioventricular block occurs in more than 90% of the cases within the first post-TAVI week, which would allow to monitor carefully the patients at least seven days before considering PPI. However, some others studies support early PPI after TAVI procedure.30 Actually, as the optimal timing for PPI after TAVI is not established, the variability of decision certainly influences the outcome of pacemaker dependency, making difficult to conclude about the best interval to proceed to a definitive PPI.

PPI after TAVI is associated with increased long-term mortality.27 Faroux and colleagues5 show the negative impact of PPI after TAVI on survival and heart failure hospitalization within the year following TAVI. Xi and colleagues7 also show a greater all-cause mortality in TAVI patients receiving a PPI. In this systematic review, only 4 studies addressed the PPI-related complications and only 8 studies reported the 30-day mortality, making the overall appraisal of the impact of PPI on patient outcome likely underestimated, as emphasized by the Danish experience of Kirkfeldt and colleagues.36 Report on PPI-related complications is also markedly variable37 and the lack of a standardize international classification of these complications may further contribute to PPI-related complications and related outcome actually under-reported.

Limitations

This systematic review had several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the follow-up varied remarkably among the included studies. The 1-year dependency was not available for all studies, limiting the conclusion to only 15 studies, whereas the others publications provided a follow-up mainly to 1 to 3 months. Only 3 studies presented a longer follow-up up to 4 years. Second, the heterogeneity about pacemaker dependency definition in the studies semantically limits our ability to compare the studies. Third, although several studies identified some risk-factors for PPI and only 1 study states multivariable predictors of pacemaker dependency, there was no agreement between studies. Finally, this is a systematic review of the literature; analysis of individual patients-data level may provide further understandings: in many of studies it was not specifically clear if the patient's native rhythm was assessed and thereby knowing for certain which patients truly required PPI.

Conclusions

This systematic review investigates the rate and predictors of pacing dependency after TAVI. Data from literature show that almost one half of the pacemakers are actively operating at 1-year follow-up. Baseline RBBB and SE valves are associated with a greater rate of pacemaker dependency at follow-up. These findings suggest that atrioventricular conduction disturbances after TAVI are reversible in a large percentage of patients. Such a condition may occur at variable time after the TAVI procedure, even within the TAVI-related hospitalization and, therefore, at a very early stage. These findings clearly indicate the need of thorough investigations regarding timing of pacemaker implantation, recovery of atrioventricular conduction, and predictors of pacemaker dependence as endpoints for further studies.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr Vernooy reported research grant from Medtronic. Dr Van't Hof reported grants from Medtronic, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Abbott. Dr Lorusso reported grants from Medtronic, LivaNova, and Eurosets. All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix E1

Table E1.

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for the assessment of the risk of bias in individual nonrandomized studies

| Author | Score | Selection | Comparability | Outcome/exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjerre Thygesen et al9 | 8 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗ |

| Urena et al10 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Nazif et al11 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Van Gils et al12 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Raelson et al13 | 8 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗ |

| Dumonteil et al14 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Kaplan et al15 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Chamandi et al16 | 8 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗ |

| Gaede et al17 | 8 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗ |

| Gonska et al18 | 7 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ |

| Marzahn et al19 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Nadeem et al20 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Campelo-Parada et al21 | 8 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗ |

| Mirolo et al22 | 8 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗ |

| Van Gils et al23 | 8 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗ |

| Takahashi et al24 | 8 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗ |

| Chan et al25 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Ghannam et al26 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Costa et al27 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Dolci et al28 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Tovia-Brodie et al29 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗ |

| Junquera et al30 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

| Meduri et al31 | 9 | ∗∗∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗∗ |

Table E2.

Baseline characteristics of studies including <250 patients (n = 30)

| Study | Year | Study design (no. centers) | Sample size | Age, y | STS score, % | Inclusion period | Left ventricle ejection fraction, % | Peripheral artery disease, % | Diabetes mellitus, % | Valve type | Follow-up, mo∗ | Approach for TAVI | Mortality at 30 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinhal et alE1 | 2008 | Prospective (1) | 106 | 84.2 | na | na | 62.5 | na | na | 100% SAPIEN | 1 | na | na |

| Jilaihawi et alE2 | 2009 | Retrospective (1) | 30 | 84.4 | 8.3 | January 2007 to March 2008 | 47.5 | na | 17.6 | 100% MCV | na | na | 8.8% |

| Baan et alE3 | 2010 | Retrospective (1) | 34 | 80.4 | 5 | na | na | na | 32 | 100% MCV | 1 | na | 20.5% |

| Fraccaro et alE4 | 2011 | Retrospective (1) | 64 | 81 | na | May 2007 to April 2009 | 52.3 | 34.4 | na | 100% MCV | 12 | 94% transfemoral 6% transsubclavian |

5% |

| Van der boon et alE5 | 2013 | Prospective (1) | 167 | 81 | na | November 2005 to February 2011 | 51 | 10.2 | 21.6 | 100% MCV | 11,5 | 97% transfemoral 3% transsubclavian |

na |

| Pereira et alE6 | 2013 | Retrospective (1) | 65 | 79.3 | na | August 2007 to May 2011 | na | 47.7 | 38.5 | 100% MCV | 6 | 78.5% transfemoral 20% transsubclavian 1.5% direct aortic |

na |

| Goldenberg et alE7 | 2013 | Retrospective (1) | 191 | na | na | February 2009 to July 2012 | na | na | na | 65% MCV 35% SAPIEN |

17 | na | na |

| Ramazzina et alE8 | 2014 | Retrospective (1) | 97 | 83 | na | October 2010 to January 2013 | 55 | na | 26.4 | 61% MCV 39% SAPIEN |

12 | 100% transfemoral | na |

| Boerlage-Van Dijk et alE9 | 2014 | Retrospective (1) | 121 | 80.5 | 4.5 | October 2007 to June 2011 | na | na | 28 | 100% MCV | 12 | 100% Transfemoral | na |

| Renilla et alE10 | 2015 | Retrospective (1) | 95 | na | na | January 2007 to December 2011 | na | na | na | 100% MCV | 35 | 86.9% transfemoral 13% transsubclavian |

na |

| Petronio et alE11 | 2015 | Prospective (9) | 194 | 80.2 | 7.2 | October 2011 to April 2013 | na | 27.6 | 31 | 100% MCV | 1 | 89.7% transfemoral 6.2% transsubclavian 4.1% direct aortic |

1.6% |

| Weber et alE12 | 2015 | Retrospective (1) | 212 | 80.8 | 9.4 | 2008 - 2012 | 52.8 | na | 25 | 100% MCV | 9 | 100% transfemoral | 6.1% |

| Schernthaner et alE13 | 2016 | Retrospective (1) | 153 | 81 | 6 | na | na | na | 31 | 82% MCV 18% SAPIEN |

1,5 | 94% transfemoral 6% direct aortic |

na |

| Kostopoulou et alE14 | 2016 | Prospective (1) | 45 | 81 | na | January 2010 to February 2012 | 49 | na | 27 | 100% MCV | 24 | na | na |

| Sideris et alE15 | 2016 | Prospective (1) | 168 | na | na | January 2009 to October 2015 | na | na | na | 100% MCV | na | 100% transfemoral | na |

| Luke et alE16 | 2016 | Retrospective (1) | 140 | 81 | na | July 2011 to May 2016 | na | na | na | 81% MCV 19% EVOLUT |

na | 100% transfemoral | na |

| Makki et alE17 | 2017 | Retrospective (1) | 172 | 83 | na | November 2011 to January 2016 | 51 | na | 46 | 92% MCV 8% LOTUS |

22 | 100% transfemoral | na |

| Nijenhuis et alE18 | 2017 | Retrospective (1) | 155 | 80.5 | 6 | June 2007 to June 2015 | 59 | 30.3 | 34.8 | na | 24 | na | na |

| Naveh et alE19 | 2017 | Prospective (1) | 110 | 80.7 | na | September 2008 to November 2013 | 57.6 | 23.6 | 30 | 75.5% MCV 24.5% SAPIEN |

12 | 88.2% transfemoral 6.4% transsubclavian 5.5% direct aortic |

na |

| Alasti et alE20 | 2018 | Prospective (1) | 152 | 83.6 | na | April 2012 to October 2016 | 59.2 | 5.3 | 18.7 | 100% LOTUS | 12 | 99.4% transfemoral 0.6% direct aortic |

2.6% |

| Ortak et alE21 | 2018 | Prospective (1) | 66 | 80.4 | 3.7 | 2014 -2016 | 53.2 | na | na | 100% LOTUS | 7 | na | 3.5% |

| Rodes-Cabau et alE22 | 2018 | Prospective (11) |

103 | 80 | 5 | June 2014 to July 2016 | 56 | na | 43 | 14.5% MCV 37% EVOLUT R 51.5% SAPIEN |

12 | 86% transfemoral 10% transapical 4% transsubclavian |

na |

| Leong et alE23 | 2018 | Retrospective (1) | 67 | 80.5 | na | January 2013 to December 2015 | na | na | 30 | 16.4% EVOLUT R 35.8% MCV 34.3% SAPIEN 13.4% Others |

2,4 | na | na |

| Sharma et alE24 | 2018 | Prospective (1) | 226 | 81.2 | na | March 2012 to October 2016 | na | na | na | 100% BE | 1 | na | na |

| Bacik et alE25 | 2018 | Prospective (1) | 116 | 77.1 | na | August 2013 to Mar 2017 | 50.5 | na | 40.5 | 100% SAPIEN | 12 | 82.8% transfemoral 17.2% transapical |

na |

| Megaly et alE26 | 2019 | Prospective (1) | 172 | na | na | January 2010 to May 2017 | na | na | 50 | na | 12 | na | na |

| Yazdchi et alE27 | 2019 | Retrospective (1) | na | na | na | 2013 - 2017 | na | na | na | na | 14 | na | na |

| McCaffrey et alE28 | 2019 | Retrospective (1) | 98 | 79.6 | 5 | May 2015 to March 2018 | 55.7 | 26 | 35 | 100% SAPIEN | 1 | 93% transfemoral 6% transapical 1% direct aortic |

4.8% |

| Miura et alE29 | 2019 | Retrospective (1) | 201 | 84.8 | 6.4 | October 2013 to September 2016 | 60.6 | 9 | 26 | 100% SAPIEN | 13.5 | 68% transfemoral l 27% transapical 5% transiliac |

0.5% |

| Dhakal et alE30 | 2020 | Retrospective (1) | 176 | 80 | 5.7 | Seprember 2012 to March 2017 | 53 | 31 | 43 | na | 18.9 | na | na |

| Total | na | 49 centers | 3612 | 81.2 | 6 | November 2005 to March 2018 | 54.4 | 24.5 | 32.1 | 65.6% MCV 23.1% SAPIEN 8% LOTUS 2.7% EVOLUT 0.5% Others |

11.4 | 92.5% transfemoral 3% transsubclavian 1% direct aortic 3.2% transapical 0.3% transiliac |

6% |

Values are n (%). STS score, Society of Thoracic Surgeons Risk Score; TAVI, transaortic valve implantation; na, not available; MCV, Medtronic CoreValve.

Follow-up is reported as mean or median as given by the authors.

Table E3.

Pacemaker details in studies including < 250 patients (n = 30)

| Study | Indications PPI | Timing of PPI, d | PPI rate | Dependency definition | Dependency rate | Dependency follow-up, months∗ | Multivariable Predictors PPI | Association | PPI-related complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinhal et alE1 | na | 2 | 5.6% | na | 86% | 6 | na | na | na |

| Jilaihawi et alE2 | 90% AVB 10% SSS |

na | 33.3% | Description by case of the % ventricular pacing at follow-up | 66.6% | 1 |

|

na | na |

| Baan et alE3 | 100% AVB | 3 | 26.9% | “ventricular pacing” reported | 100% | 1 | na |

|

na |

| Fraccaro et alE4 | 96% AVB 4% SSS |

na | 39% | With pacemaker to VVI at the lowest rate possible: continuous pacing or complete AVB or AF with inadequate ventricular response | 23.5% | 12 |

|

na | na |

| Van der boon et alE5 | 83.3% AVB 13.8% bradycardia 2.7% others |

8 | 21.6% | By temporarily turning off the PPM or programming to a VVI modus at 30 bpm to assess dependency → if high-degree AVB (second degree Mobitz II or third degree) or a slow (<30 bpm) or absent ventricular escape rhythm observed | 44.4% | 11.5 | na | na | na |

| Pereira et alE6 | 100% AVB | 3 | 33% | Absence of any intrinsic or escape rhythm during back-up pacing at 30 beats/min (VVI) | 27% | 12 | na |

|

na |

| Goldenberg et alE7 | 61.5% AVB 3% SSS 34% others |

na | 16.8% | High degree of AVB (second degree or complete) or intrinsic rhythm <30 beats/min during pacemaker inhibition | 29% | 12 | na | na | na |

| Ramazzina et alE8 | 46% AVB 55% others |

na | 36.1% | >99% ventricular pacing | 29% | 12 |

|

|

na |

| Boerlage-Van Dijk et alE9 | 91.3% AVB | 3 | 19% | Ventricular-paced rhythm (no other definition) | 52% | 11.3 |

|

|

4.3% atrial lead repositioning 4.3% pocket hematoma 4.3% cerebral vascular accident |

| Renilla et alE10 | 100% AVB | 2 | 37.9% | Presence of a high-degree AVB (Mobitz II and III) or a slow <30 bpm or absent ventricular escape rhythm (pacemaker turned off or programmed to VVI modus at 30 bpm) | 39.1% | 35 | na | na | 3% pacemaker pocket infection |

| Petronio et alE11 | na | na | 24.4% | VVI programming 30 beats/min | 40.7% | 1 |

|

|

na |

| Weber et alE12 | 90% AVB 2% bradycardy 2% SSS 5% others |

na | 23% | Pacemaker is partially or frequently needed to ensure heartbeat | 35% | 9 | na | na | na |

| Schernthaner et alE13 | 78% AVB 7% SSS 13% Others |

7 | 20% | Absence of an escape or intrinsic rhythm for 30 s during temporary back-up pacing at a rate of 30 bpm | 37% | 1.5 | na | na | na |

| Kostopoulou et alE14 | 100% AVB | na | 22% | Asystole or CHB with or without escape rhythm after cessation of pacing | 9% | 12 |

|

|

na |

| Sideris et alE15 | 100% AVB | na | 38.7% | High ventricular pacing rate >99% | 100% | 6 | na | na | 1.5% pneumothorax |

| Luke et alE16 | 100% AVB | na | 39.3% | “Pacing" | 0.7% | 3 |

|

Trends with

|

na |

| Makki et alE17 | 63% AVB 4% bradycardia 33% others |

3 | 14% | Underlying ventricular asystole >5 s, CHB, >50% pacing, symptoms in the setting of bradycardia (rate <50 bpm) | 33% | 3 | na | na | na |

| Nijenhuis et alE18 | 87% AVB | 8 | 24% | Ventricular pacing reported | 68% | 27 |

|

na | na |

| Naveh et alE19 | 100% AVB | na | 34.5% | Absent or inadequate intrinsic ventricular rhythm on pacemaker interrogation (intrinsic rhythm <30 bpm); >5% VP from the last follow-up on pacemaker interrogation; any evidence of VP on pacemaker interrogation in case where the programmed AV interval was >300 ms | 68.4% | 12 |

|

na | 0% |

| Alasti et alE20 | 89.2% AVB 2.6% SSS 7.8% Others |

3 | 25% | The need for ventricular pacing when the pacing rate was lowered to 40 bpm for 10 s → dependent: slow (<40 bpm) or absent ventricular escape rhythm or AVB (Mobitz II or III) | 38% | 12 | na | na | 16% hematomas |

| Ortak et alE21 | 83% AVB 16% others |

na | 22% | na | 64% | 1 |

|

na | na |

| Rodes-Cabau et alE22 | 81% AVB 9% bradycardia 9% others |

42 | 11% | na | 78% | 12 | na | na | na |

| Leong et alE23 | 74.6% AVB 20.8% bradycardia 13.5% others |

2.3 | 44.8% | Ventricular pacing reported | 73% | 2.4 | na |

|

0% |

| Sharma et alE24 | na | na | 11.1% | Spontaneous response ventricular rate less than 30 bpm during backup pacing set at 30 beats/min for 30 s | 32% | 1 | na |

|

na |

| Bacik et alE25 | 49.8% AVB 6.3% SSS 43.9% others |

5.5 | 13.8% | More than 95% pacing events | 12% | 12 |

|

na | na |

| Megaly et alE26 | 50.6% AVB 34.9% others |

na | 35% | CHB requiring ventricular pacing | 3.5% | 12 | na | na | na |

| Yazdchi et alE27 | 78% AVB | 2 | 8.7% | Ventricular pacing reported | 87% | 14 | na | na | na |

| McCaffrey et alE28 | na | na | 11.2% | Ventricular pacing reported | 75% | 1 | na |

|

na |

| Miura et alE29 | 90% AVB 10% SSS |

6 | 5% | Ventricular pacing reported | 40% | 12 | na | na | na |

| Dhakal et alE30 | 80% AVB 17% SSS 3% others |

2 | 17% | Ventricular pacing rate | 54% | 2.7 | RBBB | In univariate analysis:

|

na |

| Total | 72% AVB 1.7% SSS 3% bradycardia 23.2% others |

6,5 | 23.8% | na | na | 9 | na | na | na |

Values are n (%). PPI, Pacemaker implantation; na, not available; AVB, atrioventricular block; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; LBBB, left bundle branch block; VVI, single-chamber device; AF, atrial fibrillation; RBBB, right bundle branch block; PPM, permanent pacemaker; MCV, Medtronic CoreValve; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; CHB, complete heart block; SE, self-expandable.

Follow-up is reported as mean or median as given by the authors.

Table E4.

Leave-one-study out analysis

| Left-out study | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBBB | |||

| Kaplan 201915 | 2.3798 | 1.1797-4.8008 | .0155 |

| Nadeem 201820 | 2.2425 | 1.0932-4.6002 | .0276 |

| Raelson 201713 | 2.0960 | 1.0400-4.2241 | .0385 |

| Costa 201927 | 1.9345 | 1.0126-3.9288 | .0479 |

| Meduri 201931 | 1.8850 | 1.0136-3.7261 | .0483 |

| Chan 201825 | 1.6386 | 0.8001-3.3559 | .1770 |

| AF | |||

| Kaplan 201915 | 1.2220 | 0.4251-3.5122 | .7098 |

| Nadeem 201820 | 0.9829 | 0.3378-2.8599 | .9748 |

| Raelson 201713 | 0.9094 | 0.2919-2.8336 | .8699 |

| Chan 201825 | 1.4551 | 0.5188-4.0811 | .4760 |

| SE | |||

| Kaplan 201915 | 1.9233 | 1.0326-3.7266 | .0426 |

| Nadeem 201820 | 2.3432 | 1.1402-4.8153 | .0205 |

| Raelson 201713 | 2.5419 | 1.3676-4.7244 | .0032 |

| Van Gils 201712 | 2.3947 | 1.1342-5.0562 | .0220 |

| Urena 201410 | 1.8686 | 0.8743-3.9938 | .1067 |

| Takahashi 201824 | 1.8711 | 1.0048-3.4844 | .0483 |

OR, Odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; RBBB, right bundle branch block; AF, atrial fibrillation; SE, self-expandable.

References

- 1.Cribier A., Eltchaninoff H., Bash A., Borenstein N., Tron N., Bauer F., et al. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis: first human case description. Circulation. 2002;106:3006–3008. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047200.36165.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leon M.B., Smith C.R., Mack M., Miller C., Moses J.W., Svensson L.G., et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kheiri B., Osman M., Abubakar H., Subahi A., Chachine A., Ahmed S., et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk surgical patients: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2019;20:838–842. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2018.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Rosendael P.J., Delgado V., Bax J.J. Pacemaker implantation rate after transcatheter aortic valve implantation with early and new-generation devices: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2003–2013. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faroux L., Chen S., Muntané-Carol G., Reguerio A., Philippon F., Sondergaard L., et al. Clinical impact of conduction disturbances in transcatheter aortic valve replacement recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2771–2781. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piazza N., Nuis R.-J., Tzikas A., Otten A., Onuma Y., Garia-Garcia H., et al. Persistent conduction abnormalities and requirements for pacemaking six months after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eurointervention. 2010;6:475–484. doi: 10.4244/EIJ30V6I4A80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xi Z., Liu T., Liang J., Zhou U.J., Liu W. Impact on postprocedural permanent pacemaker implantation on clinical outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:5130–5139. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.12.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusumoto F.M., Schoenfeld M.H., Barrett C., Edgerton J.R., Ellenbogen K.A., Gold M.R., et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2019;140:e382–e482. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjerre Thygesen J., Loh P.H., Cholteesupachai J., Franzen O., Sondergaard L. Reevaluation of the indications for permanent pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Invasive Cardiol. 2014;26:94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urena M., Webb J.G., Tamburino C., Munoz-Garcia A.J., Cheema A., Dager A.E., et al. Permanent pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: impact on late clinical outcomes and left ventricular function. Circulation. 2014;129:1233–1243. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nazif T.M., Dizon J.M., Hahn R.T., Xu K., Babaliaros V., Douglas P.S., et al. Predictors and clinical outcomes of permanent pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the PARTNER (Placement of AoRtic TraNscathertER Valves) trial and registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Gils L., Tchetche D., Lhermusier T., Abawi M., Dumonteuil N., Rodriguez-Olivares R., et al. Transcatheter heart valve selection and permanent pacemaker implantation in patients with pre-existent right bundle branch block. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005028. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raelson C.A., Gabriels J., Ruan J., Ip J.E., Thomas G., Liu C.F., et al. Recovery of atrioventricular conduction in patients with heart block after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017;28:1196–1202. doi: 10.1111/jce.13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumonteil N., Meredith I.T., Blackman D.J., Tchétché D., Hildick-Smith D., Spence M.S., et al. Insights into the need for permanent pacemaker following implantation of the repositionable LOTUS valve for transcatheter aortic valve replacement in 250 patients: results from the REPRISE II trial with extended cohort. Eurointervention. 2017;13:796–803. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-16-01025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan R.M., Yadlapati A., Cantey E.P., Passman R.S., Gajjar M., Knight B.P., et al. Conduction recovery following pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;42:146–152. doi: 10.1111/pace.13579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chamandi C., Barbanti M., Munoz-Garcia A., Latib A., Nombela-Franco L., Guttiérrez-Ibanez E., et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with new permanent pacemaker implantation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaede L., Kim W.K., Liebetrau C., Dörr O., Sperzel J., Blumenstein J., et al. Pacemaker implantation after TAVI: predictors of AV block persistence. Clin Res Cardiol. 2018;107:60–69. doi: 10.1007/s00392-017-1158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonska B., Keßler M., Wöhrle J., Rottbauer W., Seeger J. Influence of permanent pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation with new-generation devices. Neth Heart J. 2018;26:620–627. doi: 10.1007/s12471-018-1194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marzahn C., Koban C., Seifert M., Isotani A., Neub M., Hölschermann F., et al. Conduction recovery and avoidance of permanent pacing after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Cardiol. 2018;71:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadeem F., Tsushima T., Ladas T.P., Thomas R.B., Patel S.M., Saric P., et al. Impact of right ventricular pacing in patients who underwent implantation of permanent pacemaker after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122:1712–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campelo-Parada F., Nombela-Franco L., Urena M., Regueiro A., Jiménez-Quevedo P., Del Trigo M., et al. Timing of onset and outcome of new conduction abnormalities following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: role of balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Rev Esp Cardiol (Eng Ed) 2018;71:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirolo A., Viart G., Durand E., Savouré A., Godin B., Auquier N., et al. Pacemaker memory in post-TAVI patients: who should benefit from permanent pacemaker implantation? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;41:1178–1184. doi: 10.1111/pace.13422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Gils L., Baart S., Kroon H., Rahhab Z., El Faquir N., Rodriguez-Olivares R., et al. Conduction dynamics after transcatheter aortic valve implantation and implications for permanent pacemaker implantation and early discharge: the CONDUCT-study. Europace. 2018;20:1981–1988. doi: 10.1093/europace/euy074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi M., Badenco N., Monteau J., Gandjbakhch E., Extramiana F., Urena M., et al. Impact of pacemaker mode in patients with atrioventricular conduction disturbance after trans-catheter aortic valve implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92:1380–1386. doi: 10.1002/ccd.27594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan W.K., Danon A., Wijeysundera H.C., Singh S.M. Single versus dual lead atrioventricular sequential pacing for acquired atrioventricular block during transcatheter aortic valve implantation procedures. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122:633–637. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghannam M., Cunnane R., Menees D., Grossman M.P., Chetcuti S., Patel H., et al. Atrioventricular conduction in patients undergoing pacemaker implant following self-expandable transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;42:980–988. doi: 10.1111/pace.13694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costa G., Zappulla P., Barbanti M., Cirasa A., Todaro D., Rapisarda G., et al. Pacemaker dependency after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: incidence, predictors and long-term outcomes. Eurointervention. 2019;15:875–883. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-01060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolci G., Vollema E.M., Van Der Kley F., De Weger A., Ajmone Marsan N., Delgado V., et al. One-year follow-up of conduction abnormalities after transcatheter aortic valve implantation with the SAPIEN 3 valve. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124:1239–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tovia-Brodie O., Letourneau-Shesaf S., Hochstadt A., Steinvil A., Rosso R., Finkelstein A., et al. The utility of prophylactic pacemaker implantation in right bundle branch block patient pre-transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Isr Med Assoc J. 2019;12:790–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Junquera L., Freitas-Ferraz A.B., Padron R., Silva I., Nunes-Ferreira-Neto A., Guimaraes L., et al. Intraprocedural high-degree atrioventricular block or complete heart block in transcatheter aortic valve replacement recipients with no prior intraventricular conduction disturbance. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;95:982–990. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meduri C.U., Kereiakes D.J., Rajagopal V., Makkar R.R., O’Hair D., Linke A., et al. Pacemaker implantation and dependency after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the REPRISE III Trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012594. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore S.K.L., Chau K.H., Chaudhary S., Rubin G., Bayne J., Avula U.M.R., et al. Leadless pacemaker implantation: a feasible and reasonable option in transcatheter heart valve replacement patients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;42:542–547. doi: 10.1111/pace.13648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garweg C., Vandenberk B., Foulon S., Poels P., Haemers P., Ector J., et al. Leadless pacemaker for patients following cardiac valve intervention. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;113:772–779. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brignole M., Auricchio A., Baron-Esquivias G., Bordachar P., Boriani G., Breithardt O.-A., et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the task force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in Collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) Europace. 2013;15:1070–1118. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erkapic D., De Rosa S., Kelava A., Lehmann R., Fichtlscherer S., Hohnloser S.H. Risk for permanent pacemaker after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a comprehensive analysis of the literature. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:391–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirkfeldt R.E., Johansen J.B., Nohr E.A., Jorgensen O.D., Nielsen J.C. Complications after cardiac implantable electronic device implantations: an analysis of a complete, nationwide cohort in Denmark. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1186–1194. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ezzat V.A., Lee V., Ahsan S.N., Chow A.W., Segal O., Rowland E., et al. A systematic review of ICD complications in randomized controlled trials versus registries: is our ‘real-world’ data an underestimation? Open Heart. 2015;2:e000198. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References of low-sample studies including <250 patients

- Sinhal A., Altwegg L., Pasupati S., Humphries K.H., Allard M., Martin P., et al. Atrioventricular block after transcatheter balloon expandable aortic valve implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilaihawi H., Chin D., Vasa-Nicotera M., Jeilan M., Spyt T., Ng G.A., et al. Predictors for permanent pacemaker requirement after transcatheter aortic valve implantation with the CoreValve bioprosthesis. Am Heart J. 2009;157:860–866. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baan J., Jr., Yong Z.Y., Koch K.T., Henriques J.P., Bouma B.J., Vis M.M., et al. Factors associated with cardiac conduction disorders and permanent pacemaker implantation after percutaneous aortic valve implantation with the CoreValve prosthesis. Am Heart J. 2010;159:497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraccaro C., Buja G., Tarantini G., Gasparetto V., Leoni L., Razzolini R., et al. Incidence, predictors and outcomes of conduction disorders after transcatheter self-expandable aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:747–754. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Boon R.M.A., Van Mieghem N.M., Theuns D.A., Nuis R.J., Nauta S.T., Srruys P.W., et al. Pacemaker dependency after trans-catheter aortic valve implantation with the self-expanding Medtronic CoreValve System. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1269–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.11.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira E., Ferreira N., Caeiro D., Primo J., Adao L., Oliveira L., et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation and requirements of pacing over time. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36:559–569. doi: 10.1111/pace.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg G., Kusniec J., Kadmon E., Golovchiner G., Zabarsky R., Nevzorov R., et al. Pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:1632–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramazzina C., Knecht S., Jeger R., Kaiser C., Schaer B., Osswald S., et al. Pacemaker implantation and need for ventricular pacing during follow-up after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37:1592–1601. doi: 10.1111/pace.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerlage-Van Dijk L., Kooiman K.M., Yong Z.Y., Wiegerinck E.M., Damman P., Bouma B.J., et al. Predictors and permanency of cardiac conduction disorders and necessity of pacing after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37:1520–1529. doi: 10.1111/pace.12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renilla A., Rubin J.M., Rozado J., Moris C. Long-term evolution of pacemaker dependency after percutaneous aortic valve implantation with the CoreValve prosthesis. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:61–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronio A.S., Sinning J.M., Van Mieghem N., Zucchelli G., Nickenig G., Bekeredjian R., et al. Optimal implantation depth and adherence to guidelines on permanent pacing to improve the results of transcatheter aortic valve replacement with the Medtronic CoreValve System: the CoreValve Prospective, International, Post-Market ADVANCE-II study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:837–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M., Brüggemann E., Schueler R., Momcilovic D., Sinning J.M., Ghanem A., et al. Impact of left ventricular conduction defect with or without need for permanent right ventricular pacing on functional and clinical recovery after TAVR. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015;104:964–974. doi: 10.1007/s00392-015-0865-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schernthaner C., Kraus J., Danmayr F., Hammerer M., Schneider J., Hoppe U.C., et al. Short-term pacemaker dependency after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128:198–203. doi: 10.1007/s00508-015-0906-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostopoulou A., Karyofillis P., Livanis E., Thomopoulou S., Stefopoulos C., Doudoumis K., et al. Permanent pacing after transcatheter aortic valve implantation of a CoreValve prosthesis as determined by electrocardiographic and electrophysiological predictors: a single-centre experience. Europace. 2016;18:131–137. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sideris S., Benetos G., Toutouzas K., Drakopoulou M., Sotiropoulos E., Gatzoulis K., et al. Outcomes of same day pacemaker implantation after TAVI. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2016;39:690–695. doi: 10.1111/pace.12871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke D., Huntsinger M., Carlson S.K., Lin R., Tun H., Matthews R.V., et al. Incidence and predictors of pacemaker implant post commercial approval of the CoreValve system for TAVR. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. 2016;7:2452–2460. [Google Scholar]

- Makki N., Dollery J., Jones D., Crestanello J., Lilly S. Conduction distrubances after TAVR: electrophysiological studies and pacemaker dependency. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2017;18:S10–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijenhuis V.J., Van Dijk V.F., Chaldoupi S.M., Balt J.C., Ten Berg J.M. Severe conduction defects requiring permanent pacemaker implantation in patients with a new-onset left bundle branch block after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Europace. 2017;19:1015–1021. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveh S., Perlman G.Y., Elitsur Y., Planer D., Gilon D., Leibowitz D., et al. Electrocardiographic predictors of long-term cardiac pacing dependency following transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017;28:216–223. doi: 10.1111/jce.13147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alasti M., Rashid H., Rangasamy K., Kotschet E., Adam D., Alison J., et al. Long-term pacemaker dependency and impact of pacing on mortality following transcatheter aortic valve replacement with the LOTUS valve. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92:777–782. doi: 10.1002/ccd.27463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortak J., D'Ancona G., Ince H., Agma H.U., Sarak E., Öner A., et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation with a mechanically expandable prosthesis: a learning experience for permanent pacemaker implantation rate reduction. Eur J Med Res. 2018;23:14. doi: 10.1186/s40001-018-0310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodes-Cabau J., Urena M., Nombela-Franco L., Amat-Santos I., Kleiman N., Munoz-Garcia A.J., et al. Arrhythmic burden as determined by ambulatory continuous cardiac monitoring in patients with new-onset persistent left bundle branch block following transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the MARE study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1495–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong D., Sovari A.A., Ehdaie A., Chakravarty T., Liu Q., Jilaihawi H., et al. Permanent-temporary pacemakers in the management of patients with conduction abnormalities after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2018;52:111–116. doi: 10.1007/s10840-018-0345-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma E., Chu A.F. Predictors of right ventricular pacing and pacemaker dependence in transcatheter aortic valve replacement patients. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2018;51:77–86. doi: 10.1007/s10840-017-0303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacik P., Poliacikova P., Kaliska G. Who needs a permanent pacemaker after transcatheter aortic valve implantation? Bratisl Lek Listy. 2018;119:560–565. doi: 10.4149/BLL_2018_101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megaly M., Gössl M., Sorajja P., Anzia L.E., Henstrom J., Morley P., et al. Outcomes after pacemaker implantation in patients with new-onset left bundle-branch block after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Am Heart J. 2019;218:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdchi F., Hirji S., Kaneko T. Quality control for permanent pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:347–348. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey J.A., Alzahrani T., Datta T., Solomon A.J., Mercader M., Mazhari R., et al. Outcomes of acute conduction abnormalities following transcatheter aortic valve implantation with a balloon expandable valve and predictors of delayed conduction system abnormalities in follow-up. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:1845–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura M., Shirai S., Uemura T., Hayashi M., Takiguchi H., Ito S., et al. Clinical impact of intraventricular conduction abnormalities after transcatheter aortic valve implantation with balloon-expandable valves. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal B.P., Skinner K.A., Kumar K., Lotun K., Shetty R., Kazui T., et al. Arrhythmias in relation to mortality after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Am J Med. 2020;133:1336–1342.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]