Abstract

Adenosylcobalamin-dependent glycerol dehydratase undergoes inactivation by glycerol, the physiological substrate, during catalysis. In permeabilized cells of Klebsiella pneumoniae, the inactivated enzyme is reactivated in the presence of ATP, Mg2+, and adenosylcobalamin. We identified the two open reading frames as the genes for a reactivating factor for glycerol dehydratase and designated them gdrA and gdrB. The reactivation of the inactivated glycerol dehydratase by the gene products was confirmed in permeabilized recombinant Escherichia coli cells coexpressing GdrA and GdrB proteins with glycerol dehydratase.

Glycerol dehydratase (glycerol hydrolyase [EC 4.2.1.30]) is formed by some genera of the family Enterobacteriaceae, such as Klebsiella and Citrobacter, and other bacteria when they are grown anaerobically in a medium containing glycerol (7, 10, 13). The enzyme is involved in producing an electron acceptor for the fermentation of glycerol via the dihydroxyacetone (dha) pathway (2, 3, 14). It catalyzes adenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl)-dependent conversion of glycerol, 1,2-propanediol, and 1,2-ethanediol to the corresponding aldehydes. The enzyme undergoes mechanism-based inactivation by glycerol during catalysis (8, 9). The glycerol-inactivated enzyme in permeabilized cells (in situ) of Klebsiella pneumoniae undergoes rapid reactivation by exchange of the modified coenzyme for intact AdoCbl in the presence of ATP and Mg2+ (or Mn2+) (4, 18). The complex of enzyme and cyanocobalamin (CN-Cbl) is also activated in situ under the same conditions. Diol dehydratase, an isofunctional enzyme, also undergoes inactivation by glycerol during catalysis (1, 16). Recently, we have identified the two open reading frames (ORFs) in the 3′-flanking region of the diol dehydratase genes as the genes encoding a reactivating factor for diol dehydratase of Klebsiella oxytoca and designated them the ddrAB genes (6). The complex of the DdrA and DdrB proteins was demonstrated to serve as the reactivating factor in vitro for diol dehydratase (15). Homology searches with FASTA program revealed that polypeptides homologous to DdrA and DdrB are encoded by ORF4 (11) or dhaB4 (GenBank accession number U30903) (identity, 61%) and orf2b (GenBank accession number U30903) (identity, 30%), respectively, in the vicinity of the glycerol dehydratase genes (gldABC) of K. pneumoniae (6) (Fig. 1A). ORF4 (dhaB4) exists just downstream of the gldABC genes, whereas orf2b resides upstream of the gldABC genes and is transcribed in the direction opposite that of the gldABC genes. In the present communication, we report identification of these two ORFs as the genes encoding a reactivating factor for glycerol dehydratase.

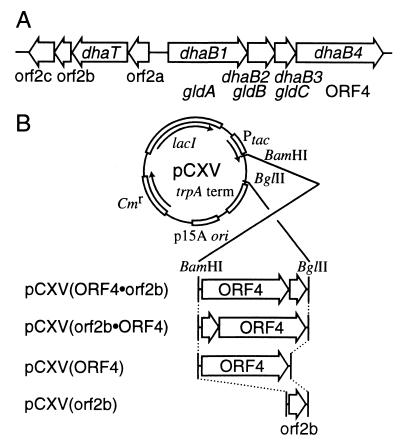

FIG. 1.

Construction of expression plasmids for ORF4 and/or orf2b in E. coli. (A) Schematic representation of the genes in the dha regulon of K. pneumoniae (11) (GenBank accession number U30903). The map is drawn to scale. ORFs are indicated by the open arrows, with the arrowhead indicating the direction of transcription. (B) The plasmids constructed for high-level expression of ORF4 and/or orf2b. Open arrows, ORFs; Cmr, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene; p15A ori, replication origin of p15A; trpA term, trpA transcriptional terminator; Ptac, tac promoter; lacI, lactose repressor gene.

Bacterial strain and construction of expression plasmids.

Escherichia coli JM109 was used as a host. pUSI2E(GD) (11) was used for overexpression of the gldABC (glycerol dehydratase) genes.

A DNA segment encoding the N-terminal region of the ORF4 product of K. pneumoniae ATCC 25955 was amplified from pUC(GD25) (11) by PCR with primer A (5′-GCGAAT TCCATATGCCG T TAATAGCCGGGAT TGATA - 3′ ) and primer B (5′-CGAGATCTCTTAAGCTGGCAACAAACGCCCTCGCCT-3′), then digested with NdeI and BglII, and cloned into the NdeI-BglII region of pUC28N (12) to produce plasmid pUC(ORF4N). A DNA segment encoding the C-terminal region of the ORF4 product was amplified from pUC(GD25) by PCR with primer C (5′-CGGGATCCCATATGCTTAAGCATCAAGGAGGGCGAACTG-3′) and primer D (5′-CGGAATTCAGATCTTTAATTCGCCTGACCGGCCAGTA-3′) and cloned into pCR2.1 vector (Promega) by TA cloning. A 0.2-kb EcoRV-BglII fragment from the resulting plasmid was ligated with the 3.2-kb EcoRV-BglII fragment from pUC(ORF4N) to construct pUC(ORF4NC). The 1.6-kb EcoRV fragment from pUC(GD25) was inserted into the EcoRV site of pUC(ORF4NC) to construct pUC(ORF4). The 1.8-kb NdeI-BglII fragment from pUC(ORF4) was inserted into the NdeI-BglII region of pCXV(DD) (6) to produce plasmid pCXV(ORF4). A 390-bp DNA fragment of the entire orf2b gene was amplified from the genomic DNA of K. pneumoniae ATCC 25955 by PCR with primer E (5′-CCGGATCCATATGTCGCTTTCACCGCCAGGCGT-3′) and primer F (5′-CGGAATTCGCGGGTATAGATACGAGATCTTCAG TTTCTCTC-3′) and cloned into pCR2.1 vector by TA cloning. The 0.4-kb NdeI-BglII fragment from the plasmid was inserted into the NdeI-BglII region of pCXV(DD) to produce plasmid pCXV(orf2b). pUC(ORF4) was digested partially with BamHI and then completely with BglII. The resulting 1.9-kb DNA fragment was ligated with pCXV(orf2b) digested with BamHI or BglII to construct pCXV(ORF4 · orf2b) or pCXV(orf2b · ORF4), respectively (Fig. 1B).

Requirement of ORF4 and orf2b genes for in situ reactivation of glycerol-inactivated glycerol dehydratase in recombinant E. coli cells.

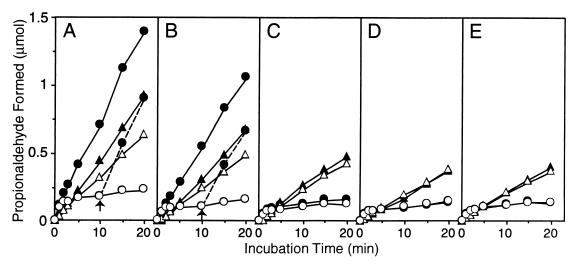

The ORF4 and/or orf2b gene was coexpressed in E. coli JM109 with the gldABC genes, and the ability of the inactivated holoenzyme to reactivate in situ was measured with glycerol and 1,2-propanediol as the substrates. Recombinant E. coli cells harboring expression plasmids were cultured and harvested as described previously (6). Permeabilized cells were prepared by treatment with 1% (vol/vol) toluene (4, 6), and the time course of dehydration of 1,2-propanediol and glycerol was determined (Fig. 2). The amount of aldehydic products formed by glycerol dehydratase reaction was determined by the 3-methyl-2-benzothiazolinone hydrazone method (17). Dehydration of glycerol by permeabilized E. coli cells expressing gldABC alone or gldABC plus ORF4 or orf2b was accompanied by concomitant inactivation, irrespective of the presence of ATP and Mg2+, and the reaction virtually ceased within 10 min (Fig. 2C to E), as observed with permeabilized K. pneumoniae cells (4). The rate constant for inactivation by glycerol in the absence of ATP and Mg2+ was 0.3 to 0.4 min−1 (Fig. 2), which is in good agreement with the value obtained in vitro with the enzyme from K. pneumoniae ATCC 25955 (0.35 min−1) (19). When 1,2-propanediol was used as a substrate, the dehydration-versus-time curve was nearly linear within 20 min. With E. coli cells coexpressing both ORF4 and orf2b, the initial, rapid phase of glycerol dehydration lasted for at least 20 min when ATP and Mg2+ were added to the reaction mixture in addition to AdoCbl (Fig. 2A and B). With these cells, the rate of dehydration of 1,2-propanediol was also enhanced in the presence of ATP and Mg2+. The reversal of the positions of ORF4 and orf2b in the expression plasmids did not significantly affect the rates of both dehydration reactions. Furthermore, addition of ATP and Mg2+ to the reaction mixture 10 min after initiation of the reaction caused the rate of dehydration of glycerol to increase to almost the rate seen when ATP and Mg2+ were added at the beginning of the reaction. These results indicated that both ORFs are required for the in situ reactivation of inactivated glycerol dehydratase, irrespective of the order of their positions in the plasmids. Thus, we designated ORF4 and orf2b gdrA and gdrB genes, respectively.

FIG. 2.

In situ dehydration of glycerol and 1,2-propanediol by recombinant E. coli cells over time. Toluene-treated E. coli JM109 (2 × 106 cells) carrying pUSI2E(GD) and pCXV(ORF4 · orf2b) (A), pUSI2E(GD) and pCXV(orf2b · ORF4) (B), pUSI2E(GD) and pCXV(ORF4) (C), pUSI2E(GD) and pCXV(orf2b) (D), or pUSI2E(GD) and pCXV (E) was incubated at 37°C for the indicated times with 15 μM AdoCbl in 30 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 50 mM KCl and 0.1 M glycerol (○, ●) or 1,2-propanediol (▵, ▴) in the presence (●, ▴) and absence (○, ▵) of ATP and MgCl2 (3 mM each) in a total volume of 1.0 ml. In panels A and B, ATP and MgCl2 were added to the reaction mixture 10 min (arrow) after the glycerol dehydration reaction was started. The amount of propionaldehyde or 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde formed was determined as described previously (17).

Expression of gdrA and gdrB genes in E. coli.

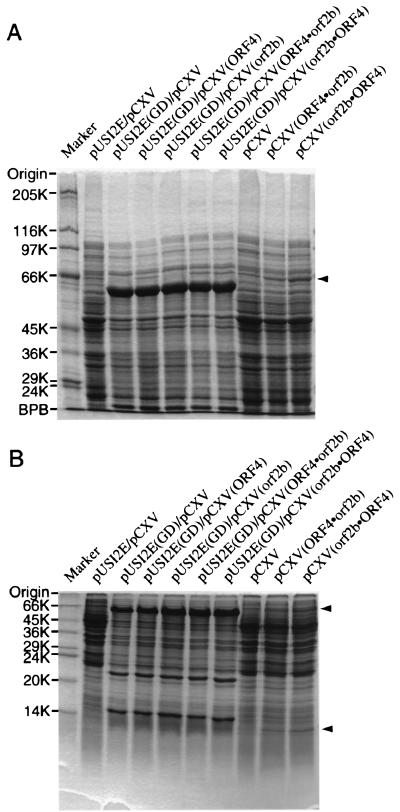

To confirm expression of the genes in E. coli, cells were disrupted by sonication. Homogenates of the recombinant E. coli cells carrying both gldABC and gdrAB on vectors pUSI2E and pCXV, respectively (Fig. 1B), were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (5) (Fig. 3). E. coli harboring plasmids containing gldABC produced thick protein bands with Mrs of 61,000, 22,000, and 16,000, which correspond to the α, β, and γ subunits of glycerol dehydratase, respectively. In contrast, only a thin protein band with an Mr of 64,000 was observed in homogenates of E. coli harboring plasmids containing gdrA and gldABC (Fig. 3A). Protein bands with Mrs of 64,000 and 12,000 were detected in the homogenate of E. coli harboring pCXV containing gdrA and gdrB, irrespective of their order, but not at all in the homogenate of E. coli carrying pCXV (control) (Fig. 3). Because the predicted molecular weights of the gdrA and gdrB gene products are 63,594 and 11,994, respectively, the polypeptides with Mrs of 64,000 and 12,000 were suggested to be GdrA and GdrB proteins, respectively.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE of homogenates of E. coli JM109 carrying expression plasmids. Gels with 7.5% polyacrylamide (A) or 15% polyacrylamide (B) were subjected to protein staining. The positions (in thousands [K]) of molecular weight markers SDS-7 plus SDS-6H (A) and SDS-7 (B) (Sigma) are shown to the left of the gels. The positions of the products of ORF4 and orf2b are indicated with arrowheads to the right of the gels. BPB, bromophenol blue.

Formation of a complex between the GdrA and GdrB proteins.

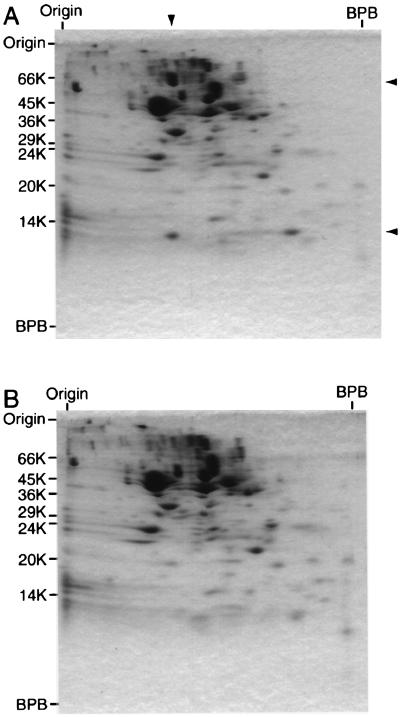

To characterize the gene products, the extract of E. coli carrying pCXV(orf2b · ORF4) was analyzed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, i.e., nondenaturing PAGE followed by SDS-PAGE (12) (Fig. 4A). The extract of E. coli carrying pCXV was electrophoresed as a control (Fig. 4B). In Fig. 4A, there were two polypeptide bands which comigrated under nondenaturing conditions and then dissociated into the two polypeptides with Mrs of 64,000 and 12,000 upon SDS-PAGE. The extract of E. coli carrying pCXV(ORF4 · orf2b) gave essentially the same result. The polypeptides were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and subjected to Edman sequencing. The N-terminal amino acid sequences of the polypeptides with Mrs of 64,000 and 12,000 were determined to be PLIAGI and SLSPPG, respectively. These sequences agreed with the N-terminal amino acid sequences deduced from the nucleotide sequences of ORF4 and orf2b, respectively, except that the N-terminal methionine residue was removed. The excess polypeptide with an Mr of 12,000 migrated faster in the first dimension. Therefore, it was concluded that these polypeptides are the GdrA and GdrB proteins, respectively, and that they exist as a tight complex. It is very likely that this complex is a putative reactivating factor for glycerol dehydratase.

FIG. 4.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of cell extract of E. coli carrying expression plasmids. Cell extracts of E. coli JM109 carrying pCXV(orf2b · ORF4) (A) and pCXV (B) were electrophoresed on 7% polyacrylamide gel under nondenaturing conditions (first dimension, from left to right) and then on SDS–13% polyacrylamide gel under denaturing conditions (second dimension, from top to bottom). In panel A, the position of two polypeptides which comigrated under nondenaturing conditions is indicated by the arrowhead over the gel and the positions of the products of ORF4 and orf2b are indicated by the arrowheads to the right of the gel. BPB, bromophenol blue.

In situ activation of glycerol dehydratase–CN-Cbl complex in E. coli coexpressing gdrAB with the glycerol dehydratase genes.

Table 1 summarizes the data on the ability of the recombinant E. coli strains to activate the enzyme–CN-Cbl complex in situ. In the presence of free AdoCbl, ATP, and Mg2+, E. coli cells coexpressing both gdrA and gdrB with the glycerol dehydratase genes showed a high level of activation of the glycerol dehydratase–CN-Cbl complex. The ability to activate the enzyme–CN-Cbl complex was very low with E. coli that coexpress gdrA or gdrB alone or that do not coexpress gdrA or gdrB. From these results, it is evident that both GdrA and GdrB proteins are essential for the in situ activation of the enzyme–CN-Cbl complex and, therefore, for the in situ reactivation of the inactivated holoenzyme. We propose calling the complex of these proteins a glycerol dehydratase-reactivating factor.

TABLE 1.

In situ activation of the glycerol dehydratase–CN-Cbl complex in E. coli coexpressing ORF4 and/or orf2b with the glycerol dehydratase genes on two expression vectorsa

| Recombinant E. colib | Extent of activation (%)c

|

|

|---|---|---|

| With ATP and MgCl2 | Without ATP and MgCl2 | |

| JM109/pUSI2E(GD)/pCXV(ORF4 · orf2b) | 94 | 3 |

| JM109/pUSI2E(GD)/pCXV(orf2b · ORF4) | 97 | 4 |

| JM109/pUSI2E(GD)/pCXV(ORF4) | 0 | 2 |

| JM109/pUSI2E(GD)/pCXV(orf2b) | 1 | 0 |

| JM109/pUSI2E(GD)/pCXV | 0 | 0 |

Toluene-treated cells (3 × 106 cells) were preincubated at 37°C for 20 min with 19 μM CN-Cbl in 31 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 63 mM KCl and 0.13 M 1,2-propanediol in a total volume of 0.8 ml. AdoCbl was then added to the mixture to a final concentration of 15 μM with and without ATP and MgCl2 (3 mM each) in a total volume of 1.0 ml. The amount of propionaldehyde formed between 5 and 10 min of incubation after the addition of AdoCbl was determined.

E. coli JM109 carrying two plasmids.

The extent of in situ activation of the enzyme–CN-Cbl complex was calculated on the basis of the amount of propionaldehyde formed between 5 and 10 min of incubation by permeabilized cells preincubated without CN-Cbl.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (Molecular Biometallics) (grant 08249226) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan, and a research grant from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Research for the Future) (grant RFTF96L00506).

We thank Koichi Mori for helpful discussion and Yukiko Kurimoto for assistance in manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachovchin W W, Eagar R G, Jr, Moore K W, Richards J H. Mechanism of action of adenosylcobalamin: glycerol and other substrate analogues as substrates and inactivators for propanediol dehydratase—kinetics, stereospecificity, and mechanism. Biochemistry. 1977;16:1082–1092. doi: 10.1021/bi00625a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forage R G, Foster M A. Glycerol fermentation in Klebsiella pneumoniae: functions of the coenzyme B12-dependent glycerol and diol dehydratases. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:413–419. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.2.413-419.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forage R G, Lin E C. dha system mediating aerobic and anaerobic dissimilation of glycerol in Klebsiella pneumoniae NCIB 418. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:591–599. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.2.591-599.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honda S, Toraya T, Fukui S. In situ reactivation of glycerol-inactivated coenzyme B12-dependent enzymes, glycerol dehydratase, and diol dehydratase. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:1458–1465. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.3.1458-1465.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mori K, Tobimatsu T, Hara T, Toraya T. Characterization, sequencing, and expression of the genes encoding a reactivating factor for glycerol-inactivated adenosylcobalamin-dependent diol dehydratase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32034–32041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pawelkiewicz J, Zagalak B. Enzymic conversion of glycerol into β-hydroxypropionaldehyde in a cell-free extract from Aerobacter aerogenes. Acta Biochim Pol. 1965;12:207–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poznanskaya A A, Yakusheva M I, Yakovlev V A. Study of the mechanism of action of adenosylcobalamin-dependent glycerol dehydratase from Aerobacter aerogenes. II. The inactivation kinetics of glycerol dehydratase complexes with adenosylobalamin and its analogs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;484:236–243. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(77)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider Z, Pawelkiewicz J. The properties of glycerol dehydratase isolated from Aerobacter aerogenes, and the properties of the apoenzyme subunits. Acta Biochim Pol. 1966;13:311–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smiley K L, Sobolov M. A cobamide-requiring glycerol dehydrase from an acrolein-forming Lactobacillus. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1962;97:538–543. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(62)90118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tobimatsu T, Azuma M, Matsubara H, Takatori H, Niida T, Nishimoto K, Satoh H, Hayashi R, Toraya T. Cloning, sequencing, and high level expression of the genes encoding adenosylcobalamin-dependent glycerol dehydrase of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22352–22357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tobimatsu T, Hara T, Sakaguchi M, Kishimoto Y, Wada Y, Isoda M, Sakai T, Toraya T. Molecular cloning, sequencing, and expression of the genes encoding adenosylcobalamin-dependent diol dehydrase of Klebsiella oxytoca. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7142–7148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toraya T. Diol dehydrase and glycerol dehydrase, coenzyme B12-dependent isozymes. In: Sigel H, Sigel A, editors. Metal ions in biological systems. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1994. pp. 217–254. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toraya T, Kuno S, Fukui S. Distribution of coenzyme B12-dependent diol dehydratase and glycerol dehydratase in selected genera of Enterobacteriaceae and Propionibacteriaceae. J Bacteriol. 1980;141:1439–1442. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.3.1439-1442.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toraya T, Mori K. A reactivating factor for coenzyme B12-dependent diol dehydratase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3372–3377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toraya T, Shirakashi T, Kosuga T, Fukui S. Substrate specificity of coenzyme B12-dependent diol dehydrase: glycerol as both a good substrate and a potent inactivator. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;69:475–480. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toraya T, Ushio K, Fukui S, Hogenkamp H P C. Studies on the mechanism of the adenosylcobalamin-dependent diol dehydrase reaction by the use of analogs of the coenzyme. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:963–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ushio K, Honda S, Toraya T, Fukui S. The mechanism of in situ reactivation of glycerol-inactivated coenzyme B12-dependent enzymes, glycerol dehydratase and diol dehydratase. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 1982;28:225–236. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.28.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yakusheva M I, Malahov A A, Poznanskaya A A, Yakovlev V A. Determination of glycerol dehydratase activity by the coupled enzymic method. Anal Biochem. 1974;60:293–301. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]