Abstract

Carbon catabolite repression in Bacillus megaterium is mediated by the transcriptional regulator CcpA. A chromosomal deletion of ccpA eliminates catabolite repression and reduces the growth rate on glucose. We describe four single-amino-acid mutations in CcpA which separate the growth effect from catabolite repression, suggesting distinct regulatory pathways for these phenotypes.

Bacillus megaterium exerts carbon catabolite repression (CCR) on transcription of the xyl operon to preferentially use energetically favorable carbon sources (29). As in Bacillus subtilis, two proteins play a central role in CCR, namely, the catabolite control protein CcpA and HPr of the phosphoenolpyruvate-sugar phosphotransferase system (6, 7, 9, 11). Upon phosphorylation of HPr at residue Ser46 by the metabolite-activated ATP-dependent kinase PtsK (27), it binds to CcpA (3), leading to recognition of DNA sequences called catabolite responsive elements (cre) (6, 7, 13). These are found in the xyl operon and in front of many catabolic genes and operons (10), several of which have been shown to be subject to CCR (reviewed in reference 8). Immunological evidence suggests that CcpA-like proteins are common to many gram-positive bacteria (18), and recent results have demonstrated that CcpA homologues are involved in CCR in Staphylococcus xylosus, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus pentosus, Lactococcus lactis, and Listeria monocytogenes (1, 4, 21, 22, 25). Thus, CcpA-mediated CCR turns out to be a widespread mechanism among gram-positive bacteria. In addition to the loss of CCR, a deletion of ccpA in B. megaterium, B. subtilis, and Lactococcus lactis also leads to a markedly decreased growth rate on minimal medium with various carbon sources (11, 22, 33).

There may be different pathways by which the catabolic signal is transmitted to CcpA-dependent target sites. CcpA binds without a cofactor to cre in front of amyE of B. subtilis (13), and in vitro repression is enhanced by combinations of HPr(Ser-P) and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate or NADP (14), whereas binding to cre sequences present in other operons is triggered by glucose-6-phosphate or HPr(Ser-P) alone (7, 24). Thus, CcpA may discriminate between different signals and respond with various outputs. We therefore asked whether the two major phenotypes, namely, CCR and the influence on growth rate, can be separated by mutations of ccpA.

Random mutagenesis of ccpA.

We randomly mutagenized the ccpA gene and set up an in vivo screen for novel or altered functions. The ccpA gene, including its putative promoter, was cloned into M13mp18 (34), and single-stranded DNA of the resulting phage mWH560 was treated with nitrite and amplified by error-prone PCR, as described previously (26). The resulting fragments were cloned into pWH2051 to give a pool of randomly mutated ccpA genes. The 5′ flanking region of ccpA in pWH2051 is shorter than in the otherwise isogenic plasmid pWH2005, which has been used for regulatory studies of CcpA (11, 16). However, CCR mediated by pWH2005 or pWH2051 carrying the wild-type gene is identical (data not shown).

Screening for ccpA alleles that differentially affect CCR and growth.

We screened the mutant pool for ccpA alleles that allow a chromosomal ccpA deletion mutant to grow normally on glucose as the sole carbon source without restoring CCR of the xyl operon (ccpAc, defective in CCR only). We also looked for strains deficient in growth but active in CCR (ccpAg, deficient in growth only). For this purpose, we constructed B. megaterium WH353 [lac ΔccpA gdh2φ(xylA1-spoVG-lacZ) ΔxylR] carrying a xylA-lacZ fusion and chromosomal deletions in ccpA and xylR to observe only the effects exerted by plasmid-encoded ccpA. The bacteria were transformed with the mutant pool of ccpA by protoplast transformation (28). After regeneration, the cells were plated on M9 minimal medium containing glucose (0.2%) as a regulatory carbon source, succinate (0.5%) as a carbon source which is not effective in CCR, and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) (80 mg/liter). We screened for large blue colonies (ccpAc) and small white colonies (ccpAg). Plasmid DNA was isolated, passaged through Escherichia coli, and again transformed into B. megaterium WH353 or WH419 [lac ΔccpA gdh2φ(xylA3-spoVG-lacZ)] (kindly provided by A. Wagner, Erlangen, Germany), and the phenotypes were reconfirmed on plates. Since B. megaterium WH419 carries a functional xylR gene, all experiments with this strain were carried out in the presence of 0.5% xylose in the growth medium. Results obtained with WH419 and WH353 were identical. The screen yielded six ccpAc alleles and one ccpAg mutant from about 2,500 primary transformants.

Characterization of ccpA mutations affecting catabolite repression only (ccpAc).

Sequencing of the ccpA alleles revealed that all ccpAc mutants carried multiple mutations, as listed in Table 1. We separated the mutations by combining ccpAc alleles with the wild type at the unique AflII site, followed by screening as described above. The subclones were named for the parental mutation, with the addition of “n” or “c”, indicating an N- or C-terminal mutation with respect to the restriction site. The superscript “c” was retained for those alleles that confer the ccpAc phenotype. The relative growth rates for the original mutants and all subclones were estimated from colony sizes on plates and are noted in Table 1. The ccpAc mutants were indistinguishable in colony size from those containing wild-type ccpA.

TABLE 1.

Effects of ccpAc and ccpAg alleles on xyl expression in B. megaterium WH419

| ccpA allele | Mutations in ccpA (positions 5′ and/or 3′ of AflII site) | CCR phenotype (% of wild type)a | Growth on platesb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | + (100) | + | |

| ΔccpA | − (9) | − | |

| ccpAc9 | T62A I73V N97S K137R P139L I216V | − (14) | + |

| ccpA9n | T62A I73V | + (39) | + |

| ccpA9c | N97S K137R P139L I216V | + (72) | + |

| ccpAc10 | T4S E149K | − (12) | + |

| ccpAc10n | T4S | − (15) | + |

| ccpA10c | E149K | + (93) | + |

| ccpAc12 | F74S I94V S138L I173V H193Y E206G | − (16) | + |

| ccpA12n | F74S I94V | + (67) | + |

| ccpA12c | S138L I173V H193Y E206G | + (38) | + |

| ccpAc19 | R47H K195R K201E | − (23) | + |

| ccpAc19n | R47H | − (21) | + |

| ccpA19c | K195R K201E | + (90) | + |

| ccpAc20 | N49S N97S D160G E189G | − (18) | + |

| ccpAc20n | N49S | − (14) | + |

| ccpA20c | N97S D160G E189G | —c (23) | − |

| ccpAc21 | N24S F74L I94V | − (17) | + |

| ccpAg14 | A17T | + (147) | +/− |

xylA-lacZ expression was determined in M9 medium containing succinate and xylose (0.5% each) or containing succinate (0.5%), xylose (0.5%), and glucose (0.2%) by the method of Miller (23). Measurements were repeated at least twice for three independent cultures, and repression factors were calculated by dividing respective activities; the result for the wild type was set at 100%, and repression below 25% was considered CCR negative.

Growth on M9 medium containing glucose (0.5%) or containing succinate (0.5%) and glucose (0.2%) was scored by visual inspection of colony sizes. +, colony size comparable to wild type; −, small colony; +/−, intermediate growth.

xylA-lacZ expression without glucose was reduced to less than 50% compared to wild-type ccpA; therefore, the phenotype was considered constitutive repression and not CCR negative.

To quantify CCR exerted by ccpA alleles, β-galactosidase activity in M9 medium with succinate or glucose and succinate as sole carbon sources was recorded. As expected from their blue phenotype on plates, the original ccpAc mutants show reduced CCR compared to wild-type ccpA, even though the remaining repression efficiency is higher than that of the ΔccpA mutant (Table 1). The mutants were considered CCR negative if they exerted 25% or less wild-type repression. The subclones of two multiply mutated ccpAc alleles (ccpAc9 and ccpAc12) did not show reduced CCR upon separation of the original mutations (Table 1). Three ccpA alleles with single mutations (ccpAc10n, ccpAc19n, and ccpAc20n) conferred wild-type-like growth along with reduced CCR (Table 1). To ensure that effects were not caused by different levels of CcpA expression, we performed Western blot analyses with extracts of total cell protein, as described previously (16). All of the mutant ccpA alleles expressed CcpA to levels similar to the wild type (data not shown).

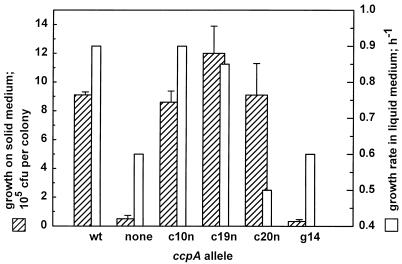

For those ccpAc mutants caused by a single-amino-acid exchange, the growth phenotype was quantified on M9 minimal medium with glucose (0.5%). Growth on plates was scored by determining the number of CFU per colony (Fig. 1). The values reflect the colony sizes given in Table 1. The growth rates in liquid medium (Fig. 1) are consistent with these observations for mutants CcpAc10n and CcpAc19n, which grow at the same rate as the wild type. CcpAc20n exhibits slower growth than the deletion mutant in liquid culture, which is in contrast to its behavior on solid medium. The activity of CcpA in CCR is dependent on the agitation of liquid cultures, with activities at low levels of agitation being comparable to those observed on solid media (2). The growth differences in CcpAc20n could be due to a similar effect, which may imply that growth regulation by CcpAc20n is sensitive to environmental conditions.

FIG. 1.

Growth of selected mutants on solid and liquid minimal media with 0.5% glucose as the sole source of carbon. To score growth on solid medium, cells were streaked on plates and incubated at 30°C for 20 h. Single colonies were excised with the surrounding agar and resuspended in liquid medium. The number of CFU was determined by plating aliquots from serial dilutions (hatched bars). Growth rates in liquid medium were determined at 32°C with vigorous agitation (open bars).

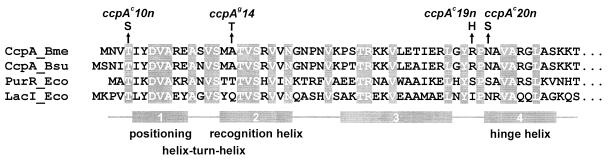

To interpret possible defects caused by the mutations, we made use of the common three-dimensional fold of LacI and PurR, which probably holds for the entire LacI/GalR family of bacterial regulators, including CcpA (32), and is supported by limited proteolysis (12) and mutational data (16, 17). Their functional implications are discussed in the light of structure-function relationships in LacI (5, 20) and PurR (30).

The three singular ccpAc mutations are located in the N-terminal DNA-binding domain of CcpA, as depicted in Fig. 2. The Thr4-to-Ser exchange in CcpAc10n aligns with Thr3 of PurR, where it is located N-terminally to the positioning α-helix 1 of the helix-turn-helix motif (Fig. 2) and does not contact DNA (30). Mutational analysis of LacI revealed that the equivalent Thr5 residue could be replaced only by Ser, yielding a partially active repressor (15). Our observation of diminished repression of xylA-lacZ by CcpAc10n resembles that result.

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignment of the N termini of B. megaterium (Bme) and B. subtilis (Bsu) CcpA and the purine and lactose repressors of E. coli (Eco). Identical amino acids are shaded. Numbered boxes below the sequences denote α-helices, as determined for PurR. The positions of amino acid exchanges of mutants isolated in this study are given above the sequences.

Arg47 is mutated to His in CcpAc19n. The equivalent residues Ser46 of PurR and Ile48 of LacI are involved in anchoring the DNA-binding domain to the core of the protein (30, 31). Any mutation at this position is likely to affect the positioning of the headpieces relative to the protein core and thus their alignment on the operator.

The ccpAc20n mutation, Asn49 to Ser, is located next to the hinge helix which connects the DNA-binding domain to the core of the protein and contacts DNA. Asn residues are frequently found at this position in the LacI/GalR family (32). PurR contains a Ser which contacts the DNA at a phosphate residue (30). Thus, the Asn49-to-Ser exchange in CcpA may affect DNA binding. In contrast to this, the corresponding residue in LacI, Asn50, is involved in interdomain contacts between the headpiece and the core (20, 31). The LacI Asn50-to-Ser mutant is fully active, while other residues at position 50 yield inactive mutants (15). Thus, the underlying reason for the reduced CCR may be altered DNA binding, but this conclusion is not unambiguously deducible from these data.

Taken together, all three ccpAc mutations are at positions likely to directly or indirectly affect DNA binding. This relates the loss of CCR to impaired recognition of cre. The fact that loss of CCR is not accompanied by a growth defect may be explained in two ways. Either DNA sequences recognized for growth regulation are different from the cre mediating CCR in xyl or from the cre consensus sequence in general or the interaction with possibly unknown cofactors leads to a titration effect that is lacking in the ΔccpA mutant but not in the ccpAc mutants.

Characterization of a ccpA mutant affecting growth only (ccpAg).

The only CcpAg mutation, CcpAg14, limited growth to small colonies on all media tested, but not as small as those of WH353 (ΔccpA). Therefore, the growth phenotype of ccpAg14 is designated “+/−” in Table 1. Quantification of its growth behavior on solid and liquid media led to values similar to those of the deletion mutant. The β-galactosidase activity of the xylA-lacZ fusion shows that the ccpAg14 mutant is even more efficient in repression than is the wild type (Table 1). CcpAg14 is expressed to a level similar to that of the wild-type protein, as determined by immunoblotting (data not shown).

The ccpAg14 mutation leads to a single-amino-acid exchange, Ala17 to Thr. This residue is located in the recognition helix (Fig. 2). The analogous Thr16 of PurR is involved in protein-DNA interaction and contacts two bases directly (30). The equivalent Gln18 of LacI also determines operator recognition (19, 20). One would therefore assume that the ccpAg14 mutation leads to an altered DNA-binding specificity of CcpA. However, because catabolite repression of xylA is even somewhat more effective with ccpAg14 than in the wild type, cre of xylA must be efficiently recognized. Thus, the growth rate reduction may not involve DNA binding, although the properties of this mutant would also be consistent with speculation that a different cis-acting sequence mediates growth rate control.

We have established for the first time that growth rate control and CCR are separable functions of CcpA. The underlying molecular basis could be interaction with different signal molecules, differences in signal transfer from the effector binding site to the headpiece, or recognition of different cis-acting sequences. The four single mutants are affected in amino acids involved in DNA recognition or interdomain contacts relevant for recognition of DNA. Although altered cofactor binding cannot be rigorously ruled out, binding of CcpA to as-yet-unidentified DNA sites is likely to be part of its function in growth regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Holger Ludwig, Bianka Wolf, and Michael Stock for help with some of the experiments and Jörg Stülke and Alexandra Kraus for fruitful discussions.

This study was supported by a personal grant of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung to E.K. and by the EU Biotech Programme, the Fonds der chemischen Industrie, and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through SFB 473.

REFERENCES

- 1.Behari J, Youngman P. A homolog of CcpA mediates catabolite control in Listeria monocytogenes but not carbon source regulation of virulence genes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6316–6324. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6316-6324.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chauvaux S, Paulsen I T, Saier M H., Jr CcpB, a novel transcription factor implicated in catabolite repression in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:491–497. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.491-497.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deutscher J, Küster E, Bergstedt U, Charrier V, Hillen W. Protein kinase-dependent HPr/CcpA interaction links glycolytic activity to carbon catabolite repression in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:1049–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egeter O, Brückner R. Catabolite repression mediated by the catabolite control protein CcpA in Staphylococcus xylosus. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:739–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.301398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman A, Fischmann T, Steitz T. Crystal structure of lac repressor core tetramer and its implications for DNA looping. Science. 1995;268:1721–1727. doi: 10.1126/science.7792597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujita Y, Miwa Y, Galinier A, Deutscher J. Specific recognition of the Bacillus subtilis gnt cis-acting catabolite-responsive element by a protein complex formed between CcpA and seryl-phosphorylated HPr. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:953–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gösseringer R, Küster E, Galinier A, Deutscher J, Hillen W. Cooperative and non-cooperative DNA binding modes of catabolite control protein CcpA from Bacillus megaterium result from sensing two different signals. J Mol Biol. 1997;266:665–676. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henkin T M. The role of the CcpA transcriptional regulator in carbon metabolism in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;135:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb07959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henkin T M, Grundy F J, Nicholson W L, Chambliss G H. Catabolite repression of α-amylase gene expression in Bacillus subtilis involves a trans-acting gene product homologous to the Escherichia coli lacI and galR repressors. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:575–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hueck C J, Hillen W, Saier M H., Jr Analysis of a cis-active sequence mediating catabolite repression in Gram-positive bacteria. Res Microbiol. 1994;145:503–518. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hueck C J, Kraus A, Schmiedel D, Hillen W. Cloning, expression and functional analyses of the catabolite control protein CcpA from Bacillus megaterium. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:855–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones B E, Dossonnet V, Küster E, Hillen W, Deutscher J, Klevit R E. Binding of the catabolite repressor protein CcpA to its DNA target is regulated by phosphorylation of its corepressor HPr. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26530–26535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J H, Guverner Z T, Cho J Y, Chung K-C, Chambliss G H. Specificity of DNA binding activity of the Bacillus subtilis catabolite control protein CcpA. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5129–5134. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.5129-5134.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J H, Voskuil M I, Chambliss G H. NADP, corepressor for the Bacillus catabolite control protein CcpA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9590–9595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleina L G, Miller J H. Genetic studies of the lac repressor. XIII. Extensive amino acid replacements generated by the use of natural and synthetic nonsense suppressors. J Mol Biol. 1990;21:295–318. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraus A, Hillen W. Analysis of CcpA mutations defective in carbon catabolite repression in Bacillus megaterium. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;153:221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraus A, Küster E, Wagner A, Hoffmann K, Hillen W. Identification of a corepressor binding site in catabolite control protein CcpA. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:955–964. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Küster E, Luesink E J, de Vos W M, Hillen W. Immunological crossreactivity to catabolite control protein CcpA from Bacillus megaterium is found in many Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;139:109–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehming N, Sartorius J, Kisters-Woike B, von Wilcken-Bergmann B, Müller-Hill B. Mutant lac repressors with new specificities hint at rules for protein-DNA recognition. EMBO J. 1990;9:615–621. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis M, Chang G, Horton N, Kercher M, Pace H, Schumacher M, Brennan R, Lu P. Crystal structure of the lactose operon repressor and its complexes with DNA and inducer. Science. 1996;271:1247–1254. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lokman B C, Heerikhuisen M, Leer R J, van den Broek A, Borsboom Y, Chaillou S, Postma P W, Pouwels P H. Regulation of expression of the Lactobacillus pentosus xylAB operon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5391–5397. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5391-5397.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luesink E, van Herpen R, Grossiord B, Kuipers O, de Vos W. Transcriptional activation of the glycolytic las operon and catabolite repression of the gal operon in Lactococcus lactis are mediated by the catabolite control protein CcpA. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:789–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miwa Y, Nagura K, Eguchi S, Fukuda H, Deutscher J, Fujita Y. Catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis gnt operon exerted by two catabolite-responsive elements. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1203–1213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2921662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monedero V, Gosalbes M, Perez-Martinez G. Catabolite repression in Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 is mediated by CcpA. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6657–6664. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6657-6664.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers R M, Lerman L S, Maniatis T. A general method for saturation mutagenesis of cloned DNA fragments. Science. 1985;229:242–247. doi: 10.1126/science.2990046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reizer J, Hoischen C, Titgemeyer F, Rivolta C, Rabus R, Stuelke J, Karamata D, Saier M H, Jr, Hillen W. A novel protein kinase that controls carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1157–1169. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rygus T, Hillen W. Catabolite repression of the xyl operon in Bacillus megaterium. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3049–3055. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.3049-3055.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmiedel D, Hillen W. Contributions of XylR, CcpA and cre to diauxic growth of Bacillus megaterium and to xylose isomerase expression in the presence of glucose and xylose. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;250:259–266. doi: 10.1007/BF02174383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schumacher M A, Choi K Y, Zalkin H, Brennan R G. Crystal structure of LacI member, PurR, bound to DNA: minor groove binding by α helices. Science. 1994;266:763–770. doi: 10.1126/science.7973627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suckow J, Markiewicz P, Kleina L G, Miller J, Kisters-Woike B, Müller-Hill B. Genetic studies of the Lac repressor. XV. 4000 single amino acid substitutions and analysis of the resulting phenotypes on the basis of the protein structure. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:509–523. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weickert M J, Adhya S. A family of bacterial regulators homologous to Gal and Lac repressors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15869–15874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wray L V, Jr, Pettengill F K, Fisher S H. Catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis hut operon requires a cis-acting site located downstream of the transcription initiation site. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1894–1902. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1894-1902.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]