Abstract

By using the ′lacZ gene, the activities of the nirI, nirS, and norC promoters were assayed in the wild type and in NNR-deficient mutants of Paracoccus denitrificans grown under various growth conditions. In addition, induction profiles of the three promoters in response to the presence of various nitrogenous oxides were determined. Transcription from the three promoters required the absence of oxygen and the presence both of the transcriptional activator NNR and of nitric oxide. The activity of the nnr promoter itself was halved after the cells had been switched from aerobic respiration to denitrification. This response was apparently not a result of autoregulation or of regulation by FnrP, since the nnr promoter was as active in the wild-type strain as it was in NNR- or FnrP-deficient mutants.

Many bacteria that face fluctuations in the oxygen concentrations in their natural habitats have the potential to switch from an aerobic mode of respiration into one that allows nitrogenous oxides to serve as terminal electron acceptors. In the complete version of the latter process, called denitrification, nitrate is sequentially reduced to dinitrogen gas via the intermediate compounds nitrite, nitric oxide (NO), and nitrous oxide. This type of respiration poses a threat to the bacteria since nitrite and, even more so, NO are cytotoxic compounds. Gene clusters encoding the reductases responsible for catalyzing these reactions have been encountered in many denitrifying species (3, 19). One of the best-characterized organisms in this respect is Paracoccus denitrificans, a gram-negative soil bacterium. It harbors the nar gene cluster encoding a membrane-bound nitrate reductase (4), the nap gene cluster encoding a periplasmic nitrate reductase (5), a locus encompassing the nir and nor gene clusters encoding the cd1-type nitrite reductase and NO reductase, respectively (7, 8), and the nos gene cluster encoding nitrous oxide reductase (11).

The expression of these gene clusters is tightly regulated (1, 17, 19). First of all, their levels of expression are inversely related to the environmental oxygen concentration. Second, the expression of the anaerobic oxidoreductases requires the presence of nitrate or its reduction products. Little is known about the nature and precise role of the regulatory proteins involved in signal perception and transcription activation during the adaptation of P. denitrificans to anaerobic nitrate respiration. The recent finding of a regulatory protein designated FnrP has shed more light on the adaptation of P. denitrificans to a change in the oxygen concentration (18). Another member of the FNR family of transcriptional regulators, designated NNR, specifically activates the transcription of the P. denitrificans nir and nor gene clusters in response to nitrate respiration (16). Evidence is emerging that NO is required for the expression of nirK (encoding a copper-type nitrite reductase) and the nor gene cluster of Rhodobacter sphaeroides (12–14). The transcription activation of these genes is under the control of the FNR homologue NnrR (14). This protein resembles the NNR protein found in P. denitrificans both in structure and in function.

All denitrifiers manage to keep the steady-state concentrations of nitrite and NO during denitrification below cytotoxic levels. The steady-state concentrations of free NO in denitrifying cultures of P. denitrificans, for instance, are in the nanomolar range (10). NNR is one of the proteins that control the free NO concentration by regulating the expression of the NO-producing (NIR) and -consuming (NOR) enzymes. As yet, R. sphaeroides is the only organism that has been shown to require NO as a signal for NNR-mediated expression (12–14). This study was aimed at elucidating whether this type of regulation plays a role in the activity of another denitrifier, P. denitrificans, as well and whether signals other than NO are required to modulate the activity of NNR.

Regulation of expression of the nnr promoters of P. denitrificans.

The nnr promoter region was cloned upstream of the ′lacZ gene of pBK11, yielding pPr771, which was then transferred to the P. denitrificans wild type and the NNR- and FnrP-deficient mutants. Table 1 shows the nnr promoter activity in these strains measured after overnight growth under three different growth conditions: (i) aerobic, (ii) oxygen-limiting, and (iii) anaerobic with NO3− (denitrification). In the wild-type strain the nnr promoter reached an activity of about 160 Miller units after aerobic and semiaerobic growth. When grown under denitrifying conditions, the promoter activity decreased to about 100 Miller units. These data indicate that the nnr promoter is always expressed but that the level of activity depends on whether the cell respires with oxygen or with nitrate as an electron acceptor. Its activity is decreased by 40% when nitrate is present but is not induced by oxygen limitation per se. The activity of the nnr promoter in the two mutants is comparable with that of the wild type, indicating that neither NNR nor FnrP has a role in the regulation of nnr transcription. This finding is in agreement with the observation that the nnr promoter region lacks DNA sequences involved in the binding of FNR homologues such as NNR and FnrP (16).

TABLE 1.

Growth condition-dependent activities of the nnr, norC, and nirS promoters

| Promoter | Activity (Miller units) (SEM) for

P. denitrificansa

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild

type

|

NNR deficient

|

FnrP

deficient

|

NirS deficient

|

||||||||||

| O2 | O2-lim | NO3− | NO2− | O2 | O2-lim | NO3− | O2 | O2-lim | NO3− | O2 | O2-lim | NO3− | |

| nnr | 157 (32.2) | 170 (4.9) | 91 (8.9) | ND | 171 (36.0) | 169 (4.9) | 107 (14.1) | 198 (43.0) | 175 (14.0) | 97 (8.2) | ND | ND | ND |

| nirS | 9 (1.2) | 46 (21.8) | 1,076 (104.2) | 732 (46.2) | 10 (1.5) | 10 (1.3) | 10 (1.2) | ND | ND | ND | 10 (0.9) | 10 (1.7) | 10 (1.8) |

| norC | 96 (8.4) | 142 (69.1) | 2,371 (302.6) | 2,100 (198.0) | 96 (8.9) | 38 (6.7) | 184 (24.0) | ND | ND | ND | 106 (8.8) | 51 (7.8) | 1,261 (190.2) |

The results are the means of at least three independent experiments with the standard errors of the mean (SEM). ND, not determined. Strains were cultured under the following growth conditions: O2, aerobically (flasks filled 1/5 with medium and heavily shaken); O2-lim, semiaerobically (flasks half filled with medium and slowly shaken); NO3−, anaerobically with 100 mM potassium nitrate (flasks completely filled with medium and not shaken); and NO2−, anaerobically with 10 mM potassium nitrite (flasks completely filled with medium and not shaken).

Nitrogenous oxides are required for NNR-mediated transcription activation.

In an earlier study, plasmid pBK11 derivatives with the nirS and norC promoter regions fused to the ′lacZ reporter gene were constructed (15). These fusions were transferred to the corresponding chromosomal loci of the P. denitrificans wild-type strain and to the NirS- and NNR-deficient mutants as confirmed by Southern analysis. Neither of the integrations affected the expression of the wild-type copies of the denitrification genes, as judged by the growth characteristics and reductase activities of the resulting strains (results not shown). Wild-type and mutant cells were grown aerobically, semiaerobically, or anaerobically with nitrate or nitrite (only the wild type) as terminal electron acceptors, after which the nirS and norC promoter activities were determined (Table 1). The results reveal that the two promoters present in the wild type are hardly active in cells grown aerobically. They show a small, about twofold increase after semiaerobic growth, and they reach their maximal activity after denitrifying growth with either nitrate or nitrite as a terminal electron acceptor. The maximal activities of the nirS and norC promoters with nitrate as an oxidant were about 1,100 and 2,400 Miller units, respectively, approximately 30- to 50-fold higher than those found in aerobically grown cells. When we repeated these experiments with both nitrate and oxygen present, we measured promoter activities that were comparable with those obtained after aerobic growth in the absence of nitrate (results not shown). These findings indicate that the absence of oxygen and the presence of nitrate or nitrite are prerequisites for the enhanced activity of these three promoters. The fact that the responses to nitrate and nitrite were almost equal suggests that not nitrate but nitrite or one of its reduction products, NO or nitrous oxide, is the signal for the observed increase in expression.

When the activities of the norC and nirS promoters were determined in NNR- and NirS-deficient mutant cells it turned out that the responses of these two promoters to added nitrate were largely diminished or absent. In the NNR-deficient mutant the nirS promoter was virtually silent, while the activity of the norC promoter was only 10% of that of the wild type. These findings corroborate the view that NNR is required for the transcription activation of the nirS and norC promoters during denitrification. In the NirS-deficient mutant grown in the presence of nitrate, the nirS promoter was also virtually silent, while the activity of the norC promoter was about 50% of the wild-type level. Furthermore, the NirS-deficient mutant accumulated nitrite in the culture medium apparently as a result of its inability to express nitrite reductase. We therefore concluded that the signal for the transcriptional activation of the two promoters was not nitrite but NO or nitrous oxide.

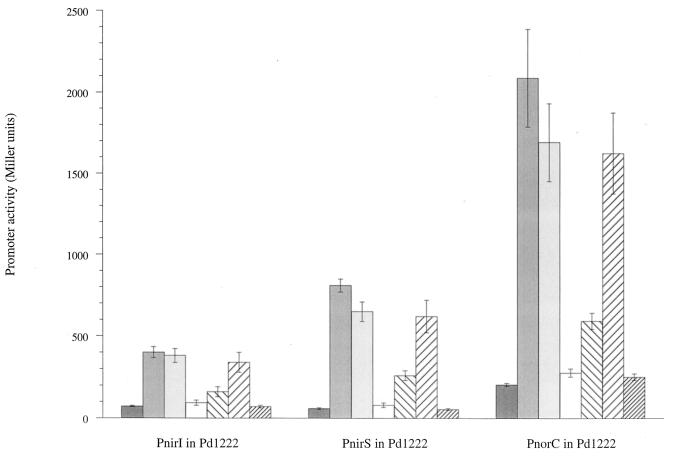

Since we had concluded from a previous study that the expression of the nirI promoter also depended on NNR, we determined the response of this promoter to added nitrogenous oxides as well. Attempts to induce the three promoters by adding NO to the growth medium resulted in untimely cell death, however. This may have been due to the extreme toxicity of NO. We therefore used sodium nitroprusside (SNP), which is an NO-generating agent (2), to release NO slowly into the culture medium. In this induction experiment, a wild-type strain equipped with either the nirI, nirS, or norC promoter fused with ′lacZ was cultured for 1 h in tubes completely filled with the medium and incubated without shaking to lower the oxygen concentration. After the addition of nitrate, nitrite, SNP, or nitrous oxide to these cultures, the levels of β-galactosidase expressed from the three target promoters were determined after overnight incubation. Figure 1 shows that SNP but not nitrous oxide induced the three promoters. At a concentration of 100 μM, SNP completely mimicked the nitrate and nitrite responses of the three promoters. The response to SNP was concentration dependent and reached maximal values in the micromolar range. In control experiments we observed no induction of the three promoters by ferricyanide, which is a structural homologue of SNP (results not shown). When we cultured the NirS-deficient mutant anaerobically in the presence of SNP, we found that the expression levels of its nirI and norC promoters resembled those of the promoters present in the wild type (results not shown).

FIG. 1.

Activities of the nirI (PnirI),

nirS (PnirS), and norC (PnorC) promoters in the

wild type (Pd1222) after induction with the N oxides listed. The

promoter was fused to the lacZ reporter gene. The activity

of the gene product β-galactosidase (in Miller units) in each strain

was determined after growth under the indicated conditions. Standard

errors of the mean are indicated by the error bars (n =

4). Symbols (from left to right):

, no addition;

, no addition;

, 3 mM nitrate;

, 3 mM nitrate;

, 3 mM nitrite; □, 1 μM SNP;

□, 10 μM SNP;

, 100 μM

SNP; ▨, 3 mM nitrous oxide.

, 3 mM nitrite; □, 1 μM SNP;

□, 10 μM SNP;

, 100 μM

SNP; ▨, 3 mM nitrous oxide.

NO is the signal for NNR-mediated transcription activation.

In order to corroborate the hypothesis that NO is the signal for NNR-mediated expression, we measured the nirI promoter activity in the NirS-deficient mutant after growing it together with a NorC-deficient mutant. The NorC-deficient mutant is a natural source of NO, since it lacks NO reductase and hence the ability to convert nitrite into NO (8). Conversely, the NirS-deficient mutant lacks the ability to form nitrite but should be able to reduce NO. A comparable type of experiment was carried out by the group led by Shapleigh, who studied norC promoter activities in Nir-deficient mutants of R. sphaeroides by using Achromobacter cycloclastes and “Rhizobium hedysari” HCNT1 as NO-producing bacteria (12). The NorC- and NirS-deficient mutants were cultured independently under aerobic growth conditions in a mineral medium with succinate as the carbon and free energy source and, at their midexponential phase of growth, aliquots of each culture were then mixed together in a fresh mineral medium supplemented with succinate and nitrate at seven different cell-to-cell ratios. The turbidity at 660 nm of each culture at the start was 0.1. The seven cultures were grown anaerobically overnight, after which the nirI promoter activities as well as the presence of nitrite, gas production (as reflected by air bubbles on top of the cultures), and the final turbidity at 660 nm were determined. Aliquots of the resulting cultures were also plated in duplicate on media with and without streptomycin in order to measure the final ratio of the two mutants after growth (the NirS-deficient mutant equipped with the nirI promoter-lacZ fusion is streptomycin resistant). The results of these analyses are presented in Table 2. The nirI promoter activities shown are related to the number of NirS cells ultimately present in each culture. The nirI promoter activity in the NirS-deficient mutant was relatively low but was increasingly induced to wild-type levels when these cells were mixed with increasing concentrations of NorC-deficient mutant cells.

TABLE 2.

Growth characteristics of and nirI promoter activities in mixed cultures of NirS- and NorC-deficient mutant cells

| Starting ratio (NorC−:NirS−)a | Characteristic

at the end of growthb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas | Nitrite | OD660 | Final ratio (NorC−:NirS−) | Activity of nirI in NirS− cells (Miller units) | |

| 1:0 | − | + | 0.19 | 1:0 | NAc |

| 4:1 | + | − | 1.92 | 1:1.8 | 541 |

| 2:1 | + | − | 2.39 | 1:6.8 | 487 |

| 1:1 | + | + | 2.31 | 1:7.4 | 460 |

| 1:2 | + | ++ | 1.89 | 1:12.5 | 306 |

| 1:4 | + | ++ | 0.95 | 1:17 | 220 |

| 0:1 | − | ++ | 0.40 | 0:1 | 35 |

The cells were grown separately under aerobic conditions and then mixed together at the various starting ratios listed till a final optical density at 660 nm (OD600) of 0.1 was reached and further incubated under denitrifying conditions.

Gas (as reflected by air bubbles on top of the cultures) was not produced (−) or was produced (+). Nitrite concentration in the culturing medium was determined with Nitur strips as not detectable (−), less than 5 mg/liter (+), or more than 5 mg/liter (++). Final ratios of NorC- and NirS-deficient mutant cells were calculated on the basis of the number of colonies obtained after plating appropriate dilutions of the cultures on plates with kanamycin (both strains can grow) and with kanamycin and streptomycin (only the NirS-deficient mutant can grow).

NA, not applicable.

In order to confirm that the induction of the nirI promoter was the result of the generation of NO in these cultures, we repeated these experiments with hemoglobin added to each of the cultures at the start of growth. Reduced hemoglobin almost irreversibly binds NO with a concomitant change in spectral properties. This property has been used to determine free NO concentrations in denitrifying cells (6, 9). We recorded the spectra of hemoglobin and NO-bound hemoglobin and compared these spectra with those obtained from hemoglobin present in the cultures after denitrifying growth. The spectral analyses showed that hemoglobin had bound NO in the cultures of the wild-type strain and in the mixed culture. Apparently, hemoglobin in these cultures was reduced by a so-far unknown redox reaction involving cellular components (most likely released after cell lysis), after which it had bound free NO. The spectra taken from the cultures of the NirS- or NorC-deficient mutants show that NO was not bound to the hemoglobin present in these cultures. For the NirS-deficient mutants this is clearly due to the inability of the cells to produce NO. The NorC-deficient mutants do produce NO, but it may well be that the hemoglobin added to the culture was not yet reduced or that the free NO concentration was already high enough to kill the cells and yet too low to allow visualization of the hemoglobin-NO adduct in the spectrum.

Conclusion.

We conclude that the NNR-mediated activation of the nirI, nirS, and norC promoters depends specifically on NO on the basis of four observations: (i) that the three promoters were all switched on in the presence of nitrate, nitrite, and SNP (an NO-generating agent) but not of nitrous oxide; (ii) that the three promoter activities were much lower in the NirS-deficient mutant, which is unable to produce NO; (iii) that the nirI and norC promoters in the NirS-deficient mutant were up-regulated by adding SNP to the growth medium; and (iv) that the nirI promoter in the NirS-deficient mutant was switched on when this strain was cultured in the presence of the NorC-deficient mutant, which produced NO. Our findings thus show that NO is a signal for NNR-mediated expression during denitrification in P. denitrificans, just as has been shown earlier for NnrR-mediated expression in R. sphaeroides (12–14).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Netherlands Foundation for Chemical Research (SON), with financial aid from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). This work was partly financed by the European Commission under contract ERB-FMB-ICT972594.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker S C, Ferguson S J, Ludwig B, Page M D, Richter O-M H, van Spanning R J M. Molecular genetics of the genus Paracoccus: metabolically versatile bacteria with bioenergetic flexibility. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1046–1078. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1046-1078.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates J N, Baker M T, Guerra R, Jr, Harrison D G. Nitric oxide generation from nitroprusside by vascular tissue. Evidence that reduction of the nitroprusside anion and cyanide loss are required. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42(Suppl):S157–S165. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90406-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berks B C, Ferguson S J, Moir J W B, Richardson D J. Enzymes and associated electron transport systems that catalyse the respiratory reduction of nitrogen oxides and oxyanions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1232:97–173. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(95)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berks B C, Page M D, Richardson D J, Reilly A, Cavill A, Outen F, Ferguson S J. Sequence analysis of subunits of the membrane-bound nitrate reductase from a denitrifying bacterium: the integral membrane subunit provides a prototype for the dihaem electron-carrying arm of a redox loop. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:319–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berks B C, Richardson D J, Reilly A, Willis A C, Ferguson S J. The napEDABC gene cluster encoding the periplasmic nitrate reductase system of Thiosphaera pantotropha. Biochem J. 1995;309:983–992. doi: 10.1042/bj3090983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carr G J, Page M D, Ferguson S J. The energy-conserving nitric-oxide-reductase system in Paracoccus denitrificans. Distinction from the nitrite reductase that catalyses synthesis of nitric oxide and evidence from trapping experiments for nitric oxide as a free intermediate during denitrification. Eur J Biochem. 1989;179:683–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Boer A P N, Reijnders W N M, Kuenen J G, Stouthamer A H, Van Spanning R J M. Isolation, sequencing and mutational analysis of a gene cluster involved in nitrite reduction in Paracoccus denitrificans. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1994;66:111–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00871635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Boer A P N, Van der Oost J, Reijnders W N M, Westerhoff H V, Stouthamer A H, Van Spanning R J M. Mutational analysis of the nor gene cluster which encodes nitric-oxide reductase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:592–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0592r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goretski J, Hollocher T C. Trapping of nitric oxide produced during denitrification by extracellular hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:2316–2323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goretski J, Zarifou O C, Hollocher T C. Steady-state nitric oxide concentrations during denitrification. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11535–11538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoeren F U, Berks B C, Ferguson S J, McCarthy J E G. Sequence and expression of the gene encoding the respiratory nitrous-oxide reductase from Paracoccus denitrificans. New and conserved structural and regulatory motifs. Eur J Biochem. 1993;218:49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwiatkowski A V, Laratta W P, Toffanin A, Shapleigh J P. Analysis of the role of the nnrR gene product in the response of Rhodobacter sphaeroides2.4.1 to exogenous nitric oxide. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5618–5620. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5618-5620.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwiatkowski A V, Shapleigh J P. Requirement of nitric oxide for induction of genes whose products are involved in nitric oxide metabolism in Rhodobacter sphaeroides2.4.3. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24382–24388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tosques I E, Shi J, Shapleigh J P. Cloning and characterization of nnrR, whose product is required for the expression of proteins involved in nitric oxide metabolism in Rhodobacter sphaeroides2.4.3. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4958–4964. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4958-4964.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Spanning, R. J. M., E. Houben, S. Koefoed, W. N. M. Reijnders, H. V. Westerhoff, A. P. N. De Boer, and N. Saunders. Submitted for publication.

- 16.Van Spanning R J M, De Boer A P N, Reijnders W N M, Spiro S, Westerhoff H V, Stouthamer A H, Van der Oost J. Nitrite and nitric oxide reduction in Paracoccus denitrificansis under the control of NNR, a regulatory protein that belongs to the FNR family of transcriptional activators. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00091-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Spanning R J M, De Boer A P N, Reijnders W N M, De Gier J W L, Delorme C O, Stouthamer A H, Westerhoff H V, Harms N, Van der Oost J. Regulation of oxidative phosphorylation: the flexible respiratory network of Paracoccus denitrificans. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1995;27:499–512. doi: 10.1007/BF02110190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Spanning R J M, De Boer A P N, Reijnders W N M, Westerhoff H V, Stouthamer A H, Van der Oost J. FnrP and NNR of Paracoccus denitrificansare both members of the FNR family of transcriptional activators but have distinct roles in respiratory adaptation in response to oxygen limitation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:893–907. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2801638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zumft W G. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:533–616. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.533-616.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]