Abstract

Van der Waals layered CuInP2S6 (CIPS) is an ideal candidate for developing two-dimensional microelectronic heterostructures because of its room temperature ferroelectricity, although field-driven polarization reversal of CIPS is intimately coupled with ionic migration, often causing erratic and damaging switching that is highly undesirable for device applications. In this work, we develop an alternative switching mechanism for CIPS using flexoelectric effect, abandoning external electric fields altogether, and the method is motivated by strong correlation between polarization and topography variation of CIPS. Phase-field simulation identifies a critical radius of curvature around 5 μm for strain gradient to be effective, which is realized by engineered topographic surfaces using silver nanowires and optic grating upon which CIPS is transferred to. We also demonstrate mechanical modulation of CIPS on demand via strain gradient underneath a scanning probe, making it possible to engineer multiple polarization states of CIPS for device applications.

Multiple intermediate polarization states of CuInP2S6 are mechanically modulated via flexoelectric engineering.

INTRODUCTION

Van der Waals layered CuInP2S6 (CIPS) has generated great excitement in recent years because of its room temperature ferroelectricity with out-of-plane spontaneous polarization (1–3), making it an ideal candidate to develop two-dimensional (2D) heterostructures for microelectronic devices (4–7). Ferroelectric field-effect transistors (6, 8), negative capacitance field-effect transistors (9, 10), ferroelectric tunneling junctions (1), and memristors (11) have all been demonstrated with CIPS, which are attractive for both logic and memory applications (6, 12) enabling future neuromorphic computing (13–15). Besides technological potentials, CIPS is also fascinating from a materials point of view, exhibiting exotic properties such as giant negative piezoelectricity (16, 17), tunable quadruple energy wells (18), large room temperature electrocaloric effect (16, 19), and strong coupling between ferroelectric polarization and ionic conductivity (13, 20, 21). It is this coupling that motivates our current study.

The hallmark of ferroelectricity is spontaneous polarization that can be switched by an external electric field (22, 23), while in CIPS, the polarization switching is intimately coupled with ionic migration (13, 20, 21). This is because paraelectric-ferroelectric phase transition and polarization switching are driven by hopping of Cu ions between two equivalent positions in the S6 octahedron of CIPS (24), and such hopping is also believed to result in the onset of ionic migration (13). The activation energies for ionic conductivity of CIPS were measured to be 1.16 eV out of plane and 0.55 eV in plane (25), suggesting that it is easier for Cu ions to hop in plane than across a van der Waals gap. This coupling has been used to realize out-of-plane polarization switching via in-plane electric field (20), and when carefully manipulated, polarization alignment against electric field is also possible (26). Nevertheless, field-driven ionic migration often causes erratic and damaging switching of CIPS (3), which is highly undesirable for device applications. Hence, alternative switching mechanisms have to be developed, for example, using electric field induced by ion adsorption (27). In this work, we abandon electric field altogether and explore the prospect of mechanical switching of CIPS instead via flexoelectric effect (14, 28–33).

RESULTS

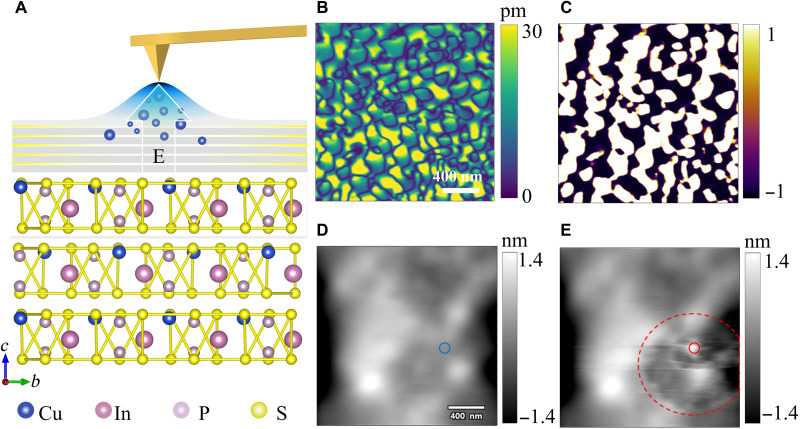

Pristine domain pattern of CIPS

The crystalline structure of CIPS is based on an ABC sulfur stacking, as schematically shown in Fig. 1A, consisting of successive [SCu1/3In1/3(P2)1/3S] layers separated by a van der Waals gap (30). There are two Cu sites within S6 octahedron, one near the upper S triangle and the other near a lower S triangle (24), labeled as Cu(1)u and Cu(1)d, respectively. Almost 90% of Cu is found in the Cu(1)u position below Curie temperature, resulting in loss of central symmetry and emergence of spontaneous polarization (34–36). Typical pristine ferroelectric domains of a 290-nm-thick CIPS flake are revealed by vertical piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) mappings of out-of-plane polarization, as shown in Fig. 1 (B and C), which are very similar to those previously reported in literature (3). During PFM measurement (37–42), a small AC voltage is applied through a scanning probe, exciting piezoelectric vibration of CIPS that can be measured by the photodiode. In principle, it is also possible to apply a larger DC voltage to switch the spontaneous polarization, as schematically shown in Fig. 1A, which inevitably induced migration of Cu ions under the scanning probe, and often causes sample damages (3, 13, 20, 43). When a DC voltage of ±6 V is applied through the scanning probe, substantial topographic change is observed in Fig. 1 (D and E) due to ionic migration–induced damage, while it fails to switch the polarization as shown by fig. S1. In other words, the strong coupling between polarization and ionic migration makes it quite challenging to manipulate CIPS polarization electrically.

Fig. 1. Structure and ferroelectricity of CIPS.

(A) Schematic crystalline structure of CIPS and migration of Cu ion under a scanning probe. (B and C) Typical vertical PFM amplitude (B) and phase (C) mappings revealing the ferroelectric domains of a CIPS flake, where we have taken the cosine of the phase angle in the phase mapping, with 1 corresponding to 0° phase for upward polarization in a material with negative piezoelectricity. (D and E) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) topography mappings before and after ±6 V applied via a scanning probe tip, exhibiting field-induced damage as revealed by topography change.

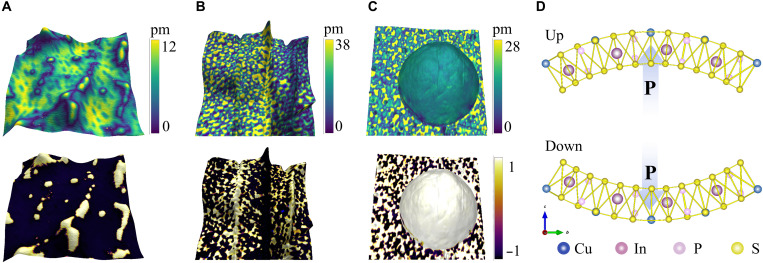

Topography-induced domain evolution

The oppositely polarized domains in Fig. 1 (B and C) are equally distributed, approximately 49 versus 51%, with a typical domain size of around 200 nm (fig. S2), which is larger than previously reported for a 290-nm-thick CIPS (1, 44). However, we also observe domain patterns that are distinctly different in places where there is large topography variation, as shown in Fig. 2. The mechanically exfoliated CIPS sample is usually atomically flat after transferring, but there are locations where topography varies, which is often accompanied by different domain characteristics. For example, a few protrusions are seen in Fig. 2A, which are all polarized in the same direction opposite to their surroundings, suggesting a strong correlation between polarization and topography feature. Wrinkles are also observed, as shown in Fig. 2B, having peaks polarized in one direction while valleys polarized in the other, with more detailed topography presented in fig. S3 demonstrating the correlation more clearly. There is also a large bubble observed in Fig. 2C, approximately 2.14 μm in radius and 374 nm in height, and it is uniformly polarized, in sharp contrast to the equally distributed domains in the surrounding area. These observations beg the question, What causes these different domain characteristics?

Fig. 2. Domain evolution associated with topography variation as revealed by vertical PFM amplitude and phase mappings, both imposed on 3D AFM topography.

(A) Protrusions. (B) Wrinkles. (C) A bubble. (D) Schematic flexoelectric effect. Image size: (A) 2 μm and (B and C) 5 μm.

The strong correlation between polarization and topography of CIPS seen in Fig. 2 (A to C) suggests that strain gradient may be important, and this can be understood schematically as shown in Fig. 2D. When there is an upward bending in CIPS, the upper part of the flake is elongated, while the lower part is shortened, and this strain gradient propels Cu ions into position of upward polarization where the free volume is larger. When it is bent downward, the opposite occurs, and this is precisely what we know as flexoelectric effect (30, 45–47). For more quantitative evaluation, we examine the radius of curvature R of these topography features in fig. S4, estimated to be 2.36, 3.8, and 2.16 μm, respectively, corresponding to a strain gradient 1/R of 0.42, 0.26, and 0.46 μm−1. With a flexoelectric coupling coefficient (14) of f13 = 3 V, the effective electric field is estimated to be 0.78 MV m−1 and larger, resulting in the alignment of the polarization at these topography features. When R increases, as demonstrated in fig. S5 (A and B), where all radii of curvature are larger than 17.9 μm, the domain pattern does not appear to be affected by the topographies. In fig. S5C, we also observe a valley with R around −1.5 μm, which does align the polarization downward as expected.

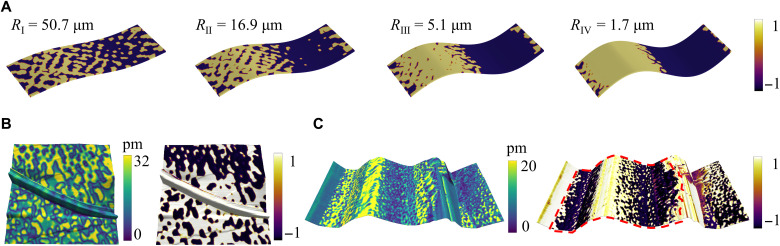

Flexoelectric engineering of CIPS

The strong effect of strain gradient on the ferroelectric domain pattern of CIPS raises an interesting prospect of flexoelectric engineering of CIPS, and to this end, we carry out phase-field simulation first to verify its feasibility. The pristine domain pattern of CIPS is captured well by the phase-field simulation (fig. S6), rendering us confidence on the model. We then design a wavy substrate following sinusoidal variation with different radius of curvature and examine the corresponding CIPS domain patterns in Fig. 3A. For a large radius of curvature of 50.7 μm, the domain pattern is not different from that of a pristine one, suggesting a negligible effect of strain gradient. When the radius of curvature is reduced to 16.9 μm and then to 5.1 μm, the domains are seen to gradually combine with each other, with upward polarized domains growing in the peak regions and downward polarized domains growing in the valleys. When the radius of curvature is further reduced to 1.7 μm, both regions become uniformly polarized, although in the opposite directions.

Fig. 3. Flexoelectric engineering of CIPS.

(A) Phase-field simulation of polarization distribution under different radii of curvature. (B and C) Flexoelectric engineering of CIPS domain patterns using (B) a silver nanowire with a diameter of 20 nm and (C) an optic grating with a period of 3 μm, as revealed by vertical PFM amplitude and phase mappings imposed on 3D AFM topography. Image size: (B) 2 μm and (C) 10 μm.

The simulations confirm the feasibility of flexoelectric engineering of CIPS, and to realize this, we design a process of transferring a CIPS flake onto a substrate with a silver nanowire of 20 nm in diameter. The part covering the silver nanowire becomes uniformly polarized as seen in Fig. 3B, with more details presented in fig. S7. Similar result is also obtained with a 90-nm silver nanowire (fig. S8). To determine the polarization direction, we have mapped vertical PFM response at a frequency of 100 kHz, much lower than the resonance, revealing a 0° phase for the nanowire-covered region (fig. S9), consistent with an upward polarization, because CIPS has negative piezoelectricity (17). We then transfer CIPS onto an optic grating with a period of 3 μm, as shown in Fig. 3C, and again observe upward polarization in the peak region and downward polarization in the valley. We also observe a case where CIPS fractures in the valley, as detailed in fig. S10, which releases the stress, and thus, no substantial change of the domain pattern is seen compared to the pristine state, further confirming the flexoelectric mechanism.

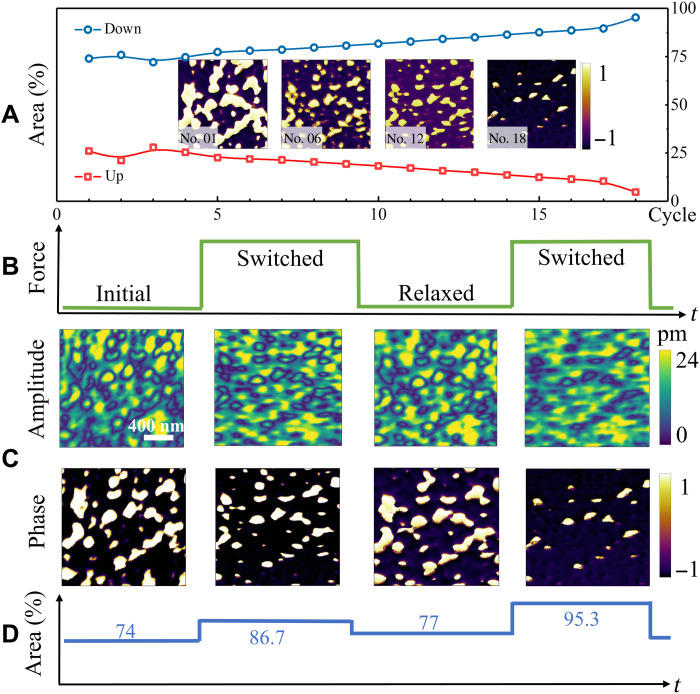

Mechanical modulation of CIPS

Last, we demonstrate mechanical modulation of CIPS on demand, via a scanning probe–induced flexoelectric effect as shown in Fig. 4. Through a finite element analysis of the tip and sample contact mechanics with a tip radius of 25 nm, we estimate that the average strain gradient underneath the scanning tip is about −5.8 μm−1 (figs. S11 and S12) for a tip force of 722 nN, capable of switching the polarization of CIPS. To realize this experimentally, we first apply a smaller tip force of 103 nN to map the ferroelectric domains of CIPS without switching it (1st scan) and then a larger one of 722 nN that is supposed to switch the polarization mechanically (2nd to 17th scans). Last, we map the domains again at the 18th scan with a tip force of 103 nN, and each scan takes about 4.25 min to complete. It is observed that with each cycle of mechanical scan, the downward polarization grows at the expense of the upward one (Fig. 4A), from the original 77% to the eventual 95.3%, and these mechanical scans induce negligible topography variation or damage in the process (fig. S13). We also study the relaxation of mechanically switched domains as schematically shown in Fig. 4B, consisting of four stages including initial mapping, mechanical switching, relaxation, and followed by another round of mechanical switching. The original domain pattern has around 74% polarization downward, which increases to 86.7% after eight cycles of mechanical scans (Fig. 4, C and D). After sitting for 96 min, downward polarization relaxes back to around 77% and then increases to 95.3% after another round of mechanical scans. We have also mechanically modulated another area, increasing the downward polarization from an initial 14 to 36%, as shown in fig. S14. It then gradually relaxes back to 28% after 300 min and keeps unchanged for over 15 hours. Such long relaxation time and incomplete reversibility may result from an ionic defect-polarization interlock as previously reported for CIPS (13). What is interesting here is that the polarization of CIPS can be mechanically modulated to multiple states by cyclic mechanical scans, a process mimicking synaptic plasticity. The polarization switched also enjoys a long relaxation time, and such nonvolatility is ideal for long-term potentiation (48) in neuromorphic computing.

Fig. 4. Mechanical modulation of CIPS.

(A) Variation of polarization with cycles of mechanical scans. (B) Schematics of initial, switching, relaxation, and another switching stages with two states of tip forces. (C) The corresponding vertical PFM amplitude and phase mappings in the four stages. (D) Percentage of downward polarization in the four stages.

DISCUSSION

Polarization switching is one of the major bottlenecks for the applications of CIPS that use its ferroelectricity, as the electrically driven process often causes ionic migration and damages, and the subtle balance has to be carefully maintained such that the applied electric field reverses the polarization without triggering longer-range ionic redistribution. Mechanical switching based on flexoelectric effect can effectively avoid such problem, enabling polarization reversal without inducing ionic migration. Notice that strain gradient can be highly localized, while electric field has an inevitably longer range, a characteristic that is important for avoiding ionic migration. While revising our manuscript, we have learned that such polarization manipulation has just been reported using sharp topography features generating a uniform domain pattern (49). We demonstrate, on the other hand, that multiple intermediate polarization states are possible not only by controlling the radius of curvature of topography but also via cyclic mechanical scanning. A couple of technical problems still have to be overcome for practical applications, because mechanical modulation of polarization states in CIPS has yet to accomplish high fidelity as electric poling in conventional ferroelectric materials. Mechanical robustness also requires further investigation, although topography damaging by mechanical scanning appears to be negligible, if any, as shown in fig. S13. Reducing the thickness from hundreds of nanometers to tens of nanometers is expected to improve the mechanical reliability further. An innovative method also needs to be designed to tune the polarization on demand more efficiently, as scanning probe is intrinsically slow, not amenable to high-speed applications. Nevertheless, we demonstrate that the polarization of CIPS can be modulated mechanically to multiple states without damaging, and the idea of flexoelectric engineering can be further developed not only for CIPS but also for a wider class of ferroelectric ionic conductors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Crystal growth

Single-crystal CIPS was grown by the chemical vapor transport method. The raw materials Cu, In, P, and S were put into a quartz test tube (inner diameter, 11 cm; length, 25 mm) according to the stoichiometric ratio to participate in the reaction, and iodine was used as the transport agent (2 mg cm−3) in the reaction process. The temperature of the evaporation and crystallization zones was set to 650° and 750°C, respectively, and the chemical reaction was carried out for 2 days. Subsequently, the evaporation and crystallization zones’ temperature was changed to 700° and 665°C, respectively, and the gas phase transport process continued for 5 days. After the reaction is complete, we waited for the test tube to cool to room temperature naturally, and then the desired CIPS single-crystal flakes can be obtained.

Substrate preparation

(i) With silver nanofiber: First, we spin-coat (2000 r min−1) silver nanowire suspension (Warner Hi-Tech; average diameter, 28 to 33 nm; average length, 18 to 23 μm) onto a clean silicon substrate and then transfer mechanically exfoliated CIPS onto the substrate; silver nanowires with a diameter of 90 nm (Aladdin; diameter, 90 nm; length, 50 μm) are treated in a similar manner. (ii) With triangular array grating: Silicon substrate (Tips Nano, TGG1, silicon; included angle, ~70°; corner radius, <10 nm) is used with the period of the triangular structure of the grating being 3 μm.

Mechanical exfoliation and transferring

CIPS flakes are transferred to the Si or silver nanofiber substrate by Scotch tape–based (50) mechanical exfoliation. For the triangular array grating substrate, the CIPS flakes are first mechanically stripped through a Scotch tape method, then transferred to homemade polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS; SYLGARD 184 Silicone Elastomer; the two-part silicone was mixed at a 10:1 mass ratio; then, PDMS was placed in a vacuum desiccator for degassing for 1 hour, and the degassed PDMS was heated in an oven at 60°C for 12 hours to expedite the polymer cross-linking), and lastly transferred to the grating via a transfer platform (Metatest, E1-T). Pressure is applied during the transfer process to ensure that the CIPS and the grating form a close contact.

PFM mapping

The ferroelectric domain structures were characterized by DART PFM (Asylum Cypher ES) with conductive Pt-coated silicon cantilevers. A tip with a spring constant of 2 N m−1 is driven with an AC voltage (Vac = 3 V) under the tip-sample contact resonant frequency (≈320 kHz).

Mechanical modulation

The experimental process of force-induced polarization modulation consists of four parts: (i) Initial state, (ii) switched stage, (iii) relaxed stage, and (iv) switched stage again, as shown in Fig. 4B. We first apply a smaller tip force of 103 nN to map ferroelectric domains without switching it (first scan) and then a larger one of 722 nN that is supposed to switch the polarization of CIPS (second to ninth scans). Last, we map the domains again at the 10th scan with a tip force of 103 nN. After sitting for 96 min, we repeat the above steps, except that we increase the number of 722-nN scans from 8 to 16, and each scan takes about 4.25 min to complete.

Phase-field simulation

On the basis of the Landau-Ginzburg-Devonshire theory, the free-energy density functional f of the CIPS thin film has the following form (51–54)

| (1) |

in which αij, αijkl, and αijklmn denote the Landau expansion coefficients; gijkl is the gradient coefficients; cijkl is the elastic constants; qijkl is the electrostrictive coefficients; fijkl represents the flexoelectric coupling coefficients; κ0 is the vacuum permittivity; and κij is the background dielectric coefficients. All energy expansions satisfy the symmetry of Cc, and the detailed form can be found in note S1. Pi, εij, and Ei are the polarization, strain, and electric field components, respectively, with the subscript “,i” representing the spatial derivative with respect to xi. In addition, all repeating subscripts in Eq. 1 follow the Einstein summation convention over the Cartesian coordinate components xi (i = 1, 2, and 3).

The spatiotemporal evolution of the polarization and domain structure is described by the time-dependent Ginzburg-Landau equation as

| (2) |

in which L is the kinetic coefficient that controls the mobility of domain evolution, denotes the total free energy functional in the whole system, and r and t represent the spatial position vector and time, respectively. In addition, the mechanical equilibrium equation including the contribution of strain gradients σij,j − tijl,lj = 0 and Maxwell’s equation Di,i = 0 are satisfied simultaneously for a body force–free and body charge–free ferroelectric material, where σij and tijl are components of stress and higher-order stress, respectively, and Di is electric displacement component. Numerical discretization, boundary conditions, and material parameters are detailed in note S1.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 12192213, 11972320, 12102164, and 12074164), the Leading Talents Program of Guangdong Province (no. 2016LJ06C372), the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory Program (2021B1212040001) from the Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province, the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (no. 2020A1515110989), the Key Research Project of Zhejiang Laboratory (no. 2021PE0AC02), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (no. RCBS20210609103201007), and the Guangdong Provincial Department of Education Innovation Team Program (2021KCXTD012).

Author contributions: J.L., and B.H. conceived and supervised the research. W.M. designed and carried out all experiments and the finite element simulation under the guidance of B.H. S.Z. performed thephase-field simulation under the guidance of Jie Wang. Y.B. prepared samples under the guidance of Junling Wang. J.L. wrote the manuscript, and all authors participated in discussion and revision.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S14

Notes S1 and S2

Table S1

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Liu F., You L., Seyler K. L., Li X., Yu P., Lin J., Wang X., Zhou J., Wang H., He H., Pantelides S. T., Zhou W., Sharma P., Xu X., Ajayan P. M., Wang J., Liu Z., Room-temperature ferroelectricity in CuInP2S6 ultrathin flakes. Nat. Commun. 7, 12357 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou S., You L., Zhou H., Pu Y., Gui Z., Wang J., Van der Waals layered ferroelectric CuInP2S6: Physical properties and device applications. Front. Phys. 16, 13301 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belianinov A., He Q., Dziaugys A., Maksymovych P., Eliseev E., Borisevich A., Morozovska A., Banys J., Vysochanskii Y., Kalinin S. V., CuInP2S6 room temperature layered ferroelectric. Nano Lett. 15, 3808–3814 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y., Weiss N. O., Duan X., Cheng H.-C., Huang Y., Duan X., Van der Waals heterostructures and devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16042 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geim A. K., Grigorieva I. V., Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang W., Wang F., Yin L., Cheng R., Wang Z., Sendeku M. G., Wang J., Li N., Yao Y., He J., Gate-coupling-enabled robust hysteresis for nonvolatile memory and programmable rectifier in Van der Waals ferroelectric heterojunctions. Adv. Mater. 32, e1908040 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albarakati S., Tan C., Chen Z. J., Partridge J. G., Zheng G., Farrar L., Mayes E. L. H., Field M. R., Lee C., Wang Y., Xiong Y., Tian M., Xiang F., Hamilton A. R., Tretiakov O. A., Culcer D., Zhao Y. J., Wang L., Antisymmetric magnetoresistance in van der Waals Fe3GeTe2/graphite/Fe3GeTe2 trilayer heterostructures. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw0409 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Si M., Liao P. Y., Qiu G., Duan Y., Ye P. D., Ferroelectric field-effect transistors based on MoS2 and CuInP2S6 two-dimensional van der Waals heterostructure. ACS Nano 12, 6700–6705 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X., Yu P., Lei Z., Zhu C., Cao X., Liu F., You L., Zeng Q., Deng Y., Zhu C., Zhou J., Fu Q., Wang J., Huang Y., Liu Z., Van der Waals negative capacitance transistors. Nat. Commun. 10, 3037 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumayer S. M., Tao L., O’Hara A., Susner M. A., McGuire M. A., Maksymovych P., Pantelides S. T., Balke N., The concept of negative capacitance in ionically conductive Van der Waals ferroelectrics. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001726 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B., Li S., Wang H., Chen L., Liu L., Feng X., Li Y., Chen J., Gong X., Ang K. W., An electronic synapse based on 2D ferroelectric CuInP2S6. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 2000760 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Q., Wen Y., Cai K., Cheng R., Yin L., Zhang Y., Li J., Wang Z., Wang F., Wang F., Shifa T. A., Jiang C., Yang H., He J., Nonvolatile infrared memory in MoS2/PbS van der Waals heterostructures. Sci. Adv. 4, eaap7916 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou S., You L., Chaturvedi A., Morris S. A., Herrin J. S., Zhang N., Abdelsamie A., Hu Y., Chen J., Zhou Y., Dong S., Wang J., Anomalous polarization switching and permanent retention in a ferroelectric ionic conductor. Mater. Horizons 7, 263–274 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang X., Wang X., Wang X., Zhang X., Niu R., Deng J., Xu S., Lun Y., Liu Y., Xia T., Lu J., Hong J., Manipulation of current rectification in van der Waals ferroionic CuInP2S6. Nat. Commun. 13, 574 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yue K., Liu Y., Lake R. K., Parker A. C., A brain-plausible neuromorphic on-the-fly learning system implemented with magnetic domain wall analog memristors. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau8170 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niu L., Liu F., Zeng Q., Zhu X., Wang Y., Yu P., Shi J., Lin J., Zhou J., Fu Q., Zhou W., Yu T., Liu X., Liu Z., Controlled synthesis and room-temperature pyroelectricity of CuInP2S6 ultrathin flakes. Nano Energy 58, 596–603 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.You L., Zhang Y., Zhou S., Chaturvedi A., Morris S. A., Liu F., Chang L., Ichinose D., Funakubo H., Hu W., Wu T., Liu Z., Dong S., Wang J., Origin of giant negative piezoelectricity in a layered van der Waals ferroelectric. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav3780 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brehm J. A., Neumayer S. M., Tao L., O’Hara A., Chyasnavichus M., Susner M. A., McGuire M. A., Kalinin S. V., Jesse S., Ganesh P., Pantelides S. T., Maksymovych P., Balke N., Tunable quadruple-well ferroelectric van der Waals crystals. Nat. Mater. 19, 43–48 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Si M., Saha A. K., Liao P. Y., Gao S., Neumayer S. M., Jian J., Qin J., Balke Wisinger N., Wang H., Maksymovych P., Wu W., Gupta S. K., Ye P. D., Room-temperature electrocaloric effect in layered ferroelectric CuInP2S6 for solid-state refrigeration. ACS Nano 13, 8760–8765 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu D.-D., Ma R.-R., Zhao Y.-F., Guan Z., Zhong Q.-L., Huang R., Xiang P.-H., Zhong N., Duan C.-G., Unconventional out-of-plane domain inversion via in-plane ionic migration in a van der Waals ferroelectric. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 6966–6971 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumayer S. M., Brehm J. A., Tao L., O’Hara A., Ganesh P., Jesse S., Susner M. A., McGuire M. A., Pantelides S. T., Maksymovych P., Balke N., Local strain and polarization mapping in ferrielectric materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 12, 38546–38553 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.W. Känzig, Ferroelectrics and antiferroeletrics, in Solid State Physics, F. Seitz, D. Turnbull, Eds. (Academic Press, 1957), pp. 1–197. [Google Scholar]

- 23.M. L. A. Glass, Principles and Applications of Ferroelectrics and Related Materials (Oxford Univ. Press, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maisonneuve V., Cajipe V. B., Simon A., Von Der Muhll R., Ravez J., Ferrielectric ordering in lamellar CuInP2S6. Phys. Rev. B 56, 10860–10868 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dziaugys A., Banys J., Macutkevic J., Vysochanskii Y., Anisotropy effects in thick layered CuInP2S6 and CuInP2Se6 crystals. Phase Transit. 86, 878–885 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumayer S. M., Tao L., O’Hara A., Brehm J., Si M., Liao P.-Y., Feng T., Kalinin S. V., Ye P. D., Pantelides S. T., Maksymovych P., Balke N., Alignment of polarization against an electric field in van der Waals ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 06063 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu D. D., Ma R. R., Fu A. P., Guan Z., Zhong N., Peng H., Xiang P. H., Duan C. G., Ion adsorption-induced reversible polarization switching of a van der Waals layered ferroelectric. Nat. Commun. 12, 655 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y., Wang X., Tang D., Wang X., Watanabe K., Taniguchi T., Gamelin D. R., Cobden D. H., Yankowitz M., Xu X., Li J., Unraveling strain gradient induced electromechanical coupling in twisted double bilayer graphene moire superlattices. Adv. Mater. 33, e2105879 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zelisko M., Hanlumyuang Y., Yang S., Liu Y., Lei C., Li J., Ajayan P. M., Sharma P., Anomalous piezoelectricity in two-dimensional graphene nitride nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 5, 4284 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu H., Bark C.-W., Esque de los Ojos D., Alcala J., Eom C. B., Catalan G., Gruverman A., Mechanical writing of ferroelectric polarization. Science 336, 59–61 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park S. M., Wang B., Das S., Chae S. C., Chung J. S., Yoon J. G., Chen L. Q., Yang S. M., Noh T. W., Selective control of multiple ferroelectric switching pathways using a trailing flexoelectric field. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 366–370 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L., Liu S., Feng X., Zhang C., Zhu L., Zhai J., Qin Y., Wang Z. L., Flexoelectronics of centrosymmetric semiconductors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 661–667 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Q. Deng, L. Liu, P. Sharma, A continuum theory of flexoelectricity, in Flexoelectricity in Solids: From Theory to Applications, A. K. Tagantsev, P. V. Yudin, Eds. (World Scientific, 2017), pp. 111–167. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maisonneuve V., Evain M., Payen C., Cajipe V. B., Molinié P., Room-temperature crystal structure of the layered phase CuIInIIIP2S6. J. Alloys Compd. 218, 157–164 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neumayer S. M., Zhao Z., O’Hara A., McGuire M. A., Susner M. A., Pantelides S. T., Maksymovych P., Balke N., Nanoscale control of polar surface phases in layered van der Waals CuInP2S6. ACS Nano 16, 2452–2460 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deng J., Liu Y., Li M., Xu S., Lun Y., Lv P., Xia T., Gao P., Wang X., Hong J., Thickness-dependent in-plane polarization and structural phase transition in van der Waals ferroelectric CuInP2S6. Small 16, e1904529 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gruverman A., Alexe M., Meier D., Piezoresponse force microscopy and nanoferroic phenomena. Nat. Commun. 10, 1661 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J., Li J.-F., Yu Q., Chen Q. N., Xie S., Strain-based scanning probe microscopies for functional materials, biological structures, and electrochemical systems. J. Materiomics 1, 3–21 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gruverman A., Scanning force microscopy for the study of domain structure in ferroelectric thin films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 14, 602 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalinin S. V., Bonnell D. A., Imaging mechanism of piezoresponse force microscopy of ferroelectric surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 65, 125408 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu W., Zeng K., Characterization of local electric properties of oxide materials using scanning probe microscopy techniques: A review. Funct. Mater. Lett. 11, 1830002 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng C., Yu L., Zhu L., Collins J. L., Kim D., Lou Y., Xu C., Li M., Wei Z., Zhang Y., Edmonds M. T., Li S., Seidel J., Zhu Y., Liu J. Z., Tang W. X., Fuhrer M. S., Room temperature in-plane ferroelectricity in van der Waals In2Se3. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar7720 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang D., Luo Z. D., Yao Y., Schoenherr P., Sha C., Pan Y., Sharma P., Alexe M., Seidel J., Anisotropic ion migration and electronic conduction in van der Waals ferroelectric CuInP2S6. Nano Lett. 21, 995–1002 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen L., Li Y., Li C., Wang H., Han Z., Ma H., Yuan G., Lin L., Yan Z., Jiang X., Liu J.-M., Thickness dependence of domain size in 2D ferroelectric CuInP2S6 nanoflakes. AIP Adv. 9, 115211 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zubko P., Catalan G., Tagantsev A. K., Flexoelectric effect in solids. Annu. Rev. Mat. Res. 43, 387–421 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu H., Kim D. J., Bark C. W., Ryu S., Eom C. B., Tsymbal E. Y., Gruverman A., Mechanically-induced resistive switching in ferroelectric tunnel junctions. Nano Lett. 12, 6289–6292 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wen Z., Qiu X., Li C., Zheng C., Ge X., Li A., Wu D., Mechanical switching of ferroelectric polarization in ultrathin BaTiO3 films: The effects of epitaxial strain. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 042907 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhong G., Zi M., Ren C., Xiao Q., Tang M., Wei L., An F., Xie S., Wang J., Zhong X., Huang M., Li J., Flexible electronic synapse enabled by ferroelectric field effect transistor for robust neuromorphic computing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 092903 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen C., Liu H., Lai Q., Mao X., Fu J., Fu Z., Zeng H., Large-scale domain engineering in two-dimensional ferroelectric CuInP2S6 via giant flexoelectric effect. Nano Lett. 22, 3275–3282 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Novoselov K. S., Geim A. K., Morozov S. V., Jiang D., Zhang Y., Dubonos S. V., Grigorieva I. V., Firsov A. A., Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu C., Wang J., Xu G., Kamlah M., Zhang T.-Y., An isogeometric approach to flexoelectric effect in ferroelectric materials. Int. J. Solids Struct. 162, 198–210 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang L., Zhou Y., Zhang Y., Yang Q., Gu Y., Chen L.-Q., Polarization switching of the incommensurate phases induced by flexoelectric coupling in ferroelectric thin films. Acta Mater. 90, 344–354 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Q., Nelson C. T., Hsu S. L., Damodaran A. R., Li L. L., Yadav A. K., McCarter M., Martin L. W., Ramesh R., Kalinin S. V., Quantification of flexoelectricity in PbTiO3/SrTiO3 superlattice polar vortices using machine learning and phase-field modeling. Nat. Commun. 8, 1468 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang B., Gu Y., Zhang S., Chen L.-Q., Flexoelectricity in solids: Progress, challenges, and perspectives. Prog. Mater Sci. 106, 100570 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen L.-Q., Phase-field method of phase transitions/domain structures in ferroelectric thin films: A review. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 91, 1835–1844 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon A., Ravez J., Maisonneuve V., Payen C., Cajipe V. B., Paraelectric-ferroelectric transition in the lamellar thiophosphate CuInP2S6. Chem. Mater. 6, 1575–1580 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shu L., Wei X., Pang T., Yao X., Wang C., Symmetry of flexoelectric coefficients in crystalline medium. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 104106 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang J., Kamlah M., Three-dimensional finite element modeling of polarization switching in a ferroelectric single domain with an impermeable notch. Smart Mater. Struct. 18, 104008 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang J., Zhang T.-Y., Size effects in epitaxial ferroelectric islands and thin films. Phys. Rev. B 73, 144107 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neumayer S. M., Eliseev E. A., Susner M. A., Tselev A., Rodriguez B. J., Brehm J. A., Pantelides S. T., Panchapakesan G., Jesse S., Kalinin S. V., McGuire M. A., Morozovska A. N., Maksymovych P., Balke N., Giant negative electrostriction and dielectric tunability in a van der Waals layered ferroelectric. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 024401 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li Y. L., Hu S. Y., Liu Z. K., Chen L. Q., Effect of substrate constraint on the stability and evolution of ferroelectric domain structures in thin films. Acta Mater. 50, 395–411 (2002). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S14

Notes S1 and S2

Table S1

References