Abstract

Objective:

To compare unreamed intramedullary nailing versus external fixation for the treatment of Gustilo-Anderson type II and IIIA open tibial fractures admitted to a hospital in rural Uganda.

Design:

Randomized clinical trial.

Setting:

Regional referral hospital in Uganda.

Patients:

Fifty-five skeletally mature patients with a Gustilo-Anderson type II or IIIA open tibia shaft fracture treated within 24 hours of injury between May 2016 and December 2019.

Intervention:

Unreamed intramedullary nailing (n = 31) versus external fixation (n = 24).

Main Outcome Measurements:

The primary outcome was function within 12 months of injury, measured using the Function IndeX for Trauma (FIX-IT) score. Secondary outcomes included health-related quality of life (HRQoL) using the EQ-5D-3L, radiographic healing using the Radiographic Union Scale for Tibia (RUST) fractures score, and clinical complications.

Results:

Treatment with an intramedullary nail resulted in a 1.0 point higher (95% CrI, 0.1 to 1.9) FIX-IT score compared to external fixation. Results were similar for the secondary patient-reported outcomes, EQ-5D-3L and EQ-VAS. RUST scores were not different between groups at any time point. Treatment with an intramedullary nail was associated with a 22.1% (95% CrI −42.6% to 1.7%) lower rate of malunion and a 20.8% (95% CrI −44.0% to 2.9%) lower rate of superficial infection.

Conclusion:

In rural Uganda, treatment of open tibial shaft fractures with an unreamed intramedullary nail results in marginal clinically important improvements in functional outcomes, though there is likely an important reduction in malunion and superficial infection.

Level of Evidence:

Therapeutic Level II. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Keywords: intramedullary nailing, external fixation, tibial shaft fractures, functional outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Open tibial shaft fractures are increasingly common in sub-Saharan Africa.1 The injury is fraught with complications and creates a substantial economic impact on patients and their families.2,3 Current evidence on the optimal treatment for open tibial shaft fractures is not necessarily generalizable to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) like Uganda, where the standard of care is external fixation.4,5

Access to timely, appropriate care remains an obstacle to much of the Ugandan population, especially in rural areas. Shortages of basic equipment, surgical implants, intraoperative radiograph, and surgical personnel are common.6,7 For these reasons, open tibia fractures are most often treated with external fixation. These fixation devices are more readily available, reusable, and do not depend on an intraoperative radiograph for their application. However, surgical capacity has been gradually improving with the expansion of the Ugandan orthopaedic surgeon training programs8 and with recognition from the international community of the importance of timely, appropriate care for open fractures.9

Although treatment with reamed intramedullary nail is the gold standard treatment for open tibial shaft fractures in high-income countries,5,10 the majority of evidence is sourced from high-income countries. There is no indication that this recommendation applies to austere environments with unique challenges such as intermittent radiographic capability, unreliable and often donated implant inventory, and vastly different socioeconomic stressors on the patients and their families. Remarkably, in a seminal randomized clinical trial in this region comparing intramedullary nail to external fixation for open tibial fractures, no difference was noted in the rate of reoperation or deep infection in neighboring Tanzania.11

The primary objective of this study was to compare unreamed intramedullary nailing with external fixation for the treatment of Gustilo-Anderson type II and IIIA open tibial fractures in rural Uganda. We hypothesized that unreamed intramedullary nailing would improve functional outcomes and have fewer complications within 1-year of injury. To answer these research questions, we used Bayesian analysis methods to incorporate prior research from high-income countries to derive more precise treatment effect estimates in the study population.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

The study was a parallel-group, randomized clinical trial performed at a regional hospital in Uganda. We screened all skeletally mature patients presenting to the accident and emergency department with open tibial shaft fractures. To meet the inclusion criteria, the patients were to be treated within 24 hours of hospital presentation and a radiographic confirmed isolated fracture with a Gustilo-Anderson classification of type II or IIIA. We excluded patients with fractures that extended less than 5 cm distal to tibial tubercle or less than 5 cm proximal to the tibiotalar joint, those with a pathological fracture, and patients with a pre-existing infection. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. The consent form was available in English and the local language, Runyankole. The study protocol was approved by the research ethics committee. The trial was registered with the Pan African Clinical Trial Registry (# BLINDED).

Randomization and Masking

Participants were randomly assigned to the treatment allocation in a 1:1 ratio. Computer randomization was not logistically viable. Instead, opaque envelopes were prepared onsite, sealed, and sorted in a random sequence. Research staff selected the next available envelope in the sequence to assign the treatment to patients after informed consent. The treating staff and patients were not blinded to their study group allocation.

Procedures

All patients were treated with antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis upon arrival. The open wounds were cleaned of any gross contamination, provisionally dressed, and the fracture splinted. At the time of definitive fixation, the injured limb was scrubbed preoperatively with copious amounts of soapy tap water, followed by irrigation with 6 to 9 liters of normal saline, then chlorhexidine or iodine. The wound and the fracture ends were then debrided of any devitalized tissues.

For patients allocated to the unreamed intramedullary nail treatment, the treating surgeon used a trans-patellar tendon start point and checked the position using intraoperative fluoroscopy. Once the nail was advanced, the surgeon secured the nail using at least 1 distal and proximal locking bolt. Dynamic bolt fixation was allowed for simple fracture patterns.

For patients allocated to the external fixation treatment, 2 fixation pins were placed distal to the fracture site, and 2 fixation pins were placed proximal to the fracture site to stabilize the fracture. Once fracture callus was observed on follow-up radiograph (approximately 6–12 weeks after injury), the external fixation was replaced with a patella tendon bearing cast kept in place for 4–6 weeks.

In both groups, the treating surgeon attempted to primarily close the wound at the time of definitive fixation, and intravenous antibiotics were continued for a period determined by the orthopaedic surgeon dependent on the healing status of the wound. Timely change of wound dressings was done depending on the soiling. In addition, all patients were offered postoperative physiotherapy to improve the range of motion of their knees and ankles while recovering in the hospital. Weight-bearing status was advanced at the discretion of the treating orthopaedic surgeon after the 4–8 week follow-up visit. At this point, if fracture callous was visible, the surgeon promoted patients in both groups to partial weight-bearing, with advancement to weight-bearing as tolerated at their next clinical visit. Follow-up visits in both groups were scheduled for 2 weeks, 4–8 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months post-randomization.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the patient’s functional status within 12 months, as measured using the Function IndeX for Trauma (FIX-IT) at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after randomization.1 FIX-IT is a validated measure that scores patient-reported function on a 12-point scale with four domains: single-leg stand, ambulation, palpation, and stress.12

Secondary outcomes included health-related quality of life (HRQoL), radiographic healing, and clinical complications. We measured HRQoL using the EQ-5D-3L on a scale from 0 to 1 (perfect health) and EQ-VAS (visual analog scale) on a scale from 0 to 100 (perfect health).13,14 Radiographic healing was measured using the Radiographic Union Scale for Tibia (RUST) fractures score.15 The RUST score is reported on a 12-point scale based on the presence of bridging callus on each of four cortices seen on two orthogonal radiographic views. Clinical complications included malunion, nonunion, deep surgical site infection, superficial infection, and wound healing complication. Malunion was defined as an angular deformity greater than 5 degrees in the coronal plane, 10 degrees in the sagittal plane, greater than 1 cm of shortening, or less than 50% cortical apposition. Nonunion was defined as failure to demonstrate improved healing (improved RUST score) on radiographs taken at least 3 months apart, at least 6 months postoperatively.

Statistical Analysis

A meta-analysis of previous clinical trials performed in high-income countries reported that the treatment of open tibial shaft fractures with intramedullary nails improved patient outcomes by a standardized effect of Cohen’s d=0.5 compared to treatment with external fixation.5 We scaled this effect to the FIX-IT score (mean = 1.5 points, SD = 1.7) and used these data to construct informative Bayesian priors. Assuming a 1-year average FIX-IT score of 8 points with a standard deviation (SD) of 3 points,5 25 patients in each study group provided over 80% probability of observing a 1.5-point change in the average FIX-IT score 12 months after randomization.

We analyzed outcomes using Bayesian models and an intention-to-treat approach. In Bayesian analyses, treatment effects are estimated using the trial data and incorporating the previous probability of effects estimated from earlier studies. The average treatment effect on FIX-IT scores, HRQoL, and radiographic healing within 12 months of injury was calculated using hierarchical Bayesian models. The hierarchical models account for the covariance of repeated measures of the outcome for individual patients and time trends from baseline to 12 months post-injury. Missing outcome data were assumed to be missing at random in the hierarchical models and accounted for within the covariance structure of the models. We evaluated the treatment effect on clinical complications using Bayesian generalized linear regression models with a Bernoulli distribution.

All models were estimated using both neutral and informative priors. The neutral priors assume a null effect with a moderate variance (SD, 0.5 for continuous outcomes; SD, 1.0 for binary outcomes). Models using informative prior assumed treatment effects of d=0.5 and scaled to the relevant outcome with a narrower variance. The specific details for the priors used in each analysis are included in the Appendix, see Supplemental Digital Content 1. We report treatment differences on an absolute scale with 95% credible intervals (CrI) for all outcomes. In addition, we present the probability of a treatment benefit greater than null for unreamed intramedullary nailing compared with external fixation. We also present the probability of a treatment benefit greater than the effect reported in the aforementioned meta-analysis (d=0.5) scaled to our included outcomes. A probability of treatment benefit can be interpreted as the likelihood that treatment with intramedullary nailing will lead to an outcome exceeding our prespecified threshold compared with external fixation. A probability of treatment benefit of 50% suggests the outcomes will be similar with either intervention. For simplicity, we report the results from the neutral prior models in the text. The informative prior results are included in the tables. All statistical analyses were performed using R Version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).16

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

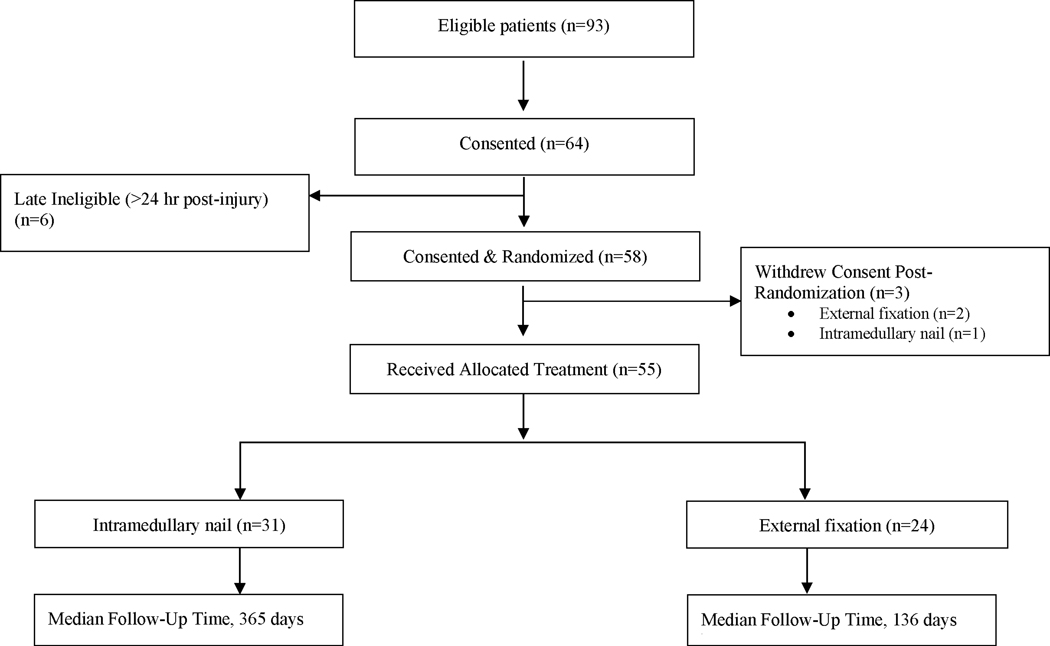

Between May 2016 and December 2019, 93 patients met the eligibility criteria, of which 64 patients consented to the trial (Figure 1). Six of the consented patients were not treated within 24 hours of injury and classified as late ineligible. An additional 3 patients withdrew consent after randomization. The final analysis included 55 patients (31 patients allocated to unreamed intramedullary nail treatment and 24 patients assigned to external fixation treatment). The mean age was 39 years (SD, 12) (Table 1). Two-thirds of the patients were male, and the majority of the fractures (76%) were classified as Gustilo-Anderson type IIIa. Baseline characteristics were broadly similar in both groups, with some differences in tobacco and alcohol use. All patients were adherent to their assigned treatment. The median follow-up time in the intramedullary nail group was 365 days and 136 days in the external fixation group.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Intramedullary Nail N = 31 | External Fixation N = 24 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 39 (11) | 39 (13) |

| Male | 21 (68%) | 16 (67%) |

| Smoker | 7 (23%) | 4 (17%) |

| Alcohol use | 21 (68%) | 10 (42%) |

| Gustilo-Anderson type | ||

| II | 8 (26%) | 5 (21%) |

| IIIA | 23 (74%) | 19 (79%) |

| OTA/AO classification | ||

| 42A | 18 (58%) | 15 (62%) |

| 42B | 9 (29%) | 8 (33%) |

| 42C | 4 (13%) | 1 (4%) |

| Mechanism of injury | ||

| Car | 3 (10%) | 3 (12%) |

| Motorbike | 20 (65%) | 19 (79%) |

| Other | 4 (13%) | 1 (4%) |

| Pedestrian | 4 (13%) | 1 (4%) |

Primary Outcome – FIX-IT Score

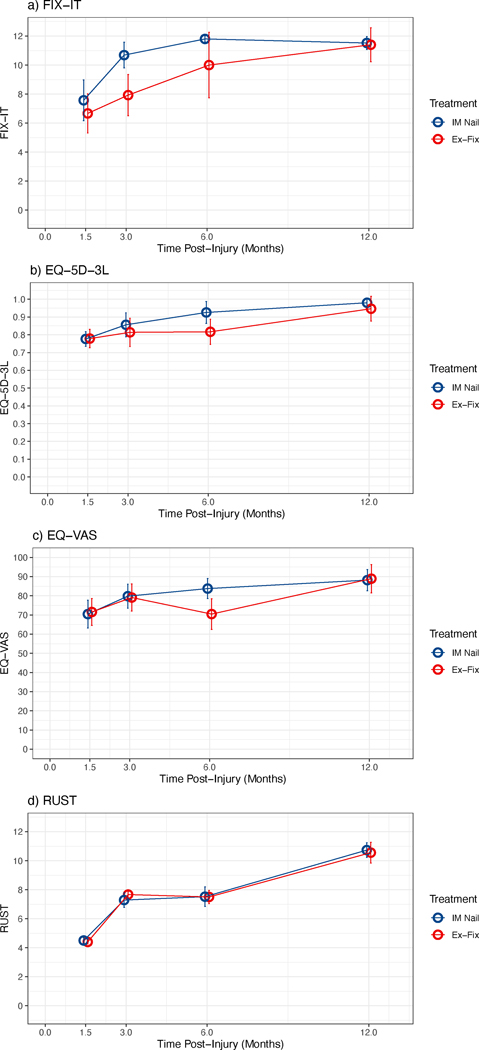

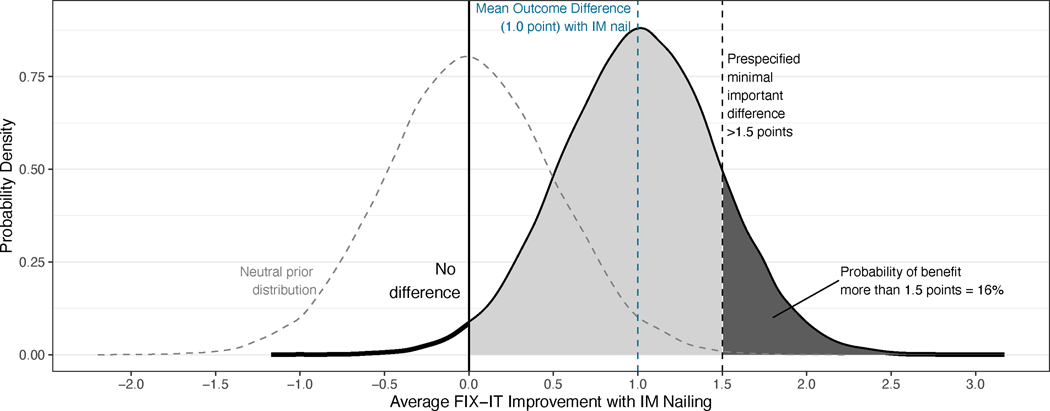

Within 12 months of injury, the FIX-IT score was 1.0-point higher (95% CrI, 0.1 to 1.9) in patients allocated to the intramedullary nailing group compared with the external fixation group (Table 2, Figure 2). Based on these data, the probability that intramedullary nailing has a greater than null treatment effect is 98%. However, there is only a 16% chance that the treatment benefit exceeds the hypothesized 1.5-point difference (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes, Treatment Differences, and Probability of Treatment Effect

| Outcome | IM Nail | External Fixation | Neutral Priors | Informative Priors1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CrI) | Prob of Treatment Benefit Greater than 0 | Prob of Treatment Benefit Greater than Pre-Specified MCID1 | Difference (95% CrI) | Prob of Treatment Benefit Greater than 0 | Prob of Treatment Benefit Greater than Pre-Specified MCID1 | |||

| Primary | ||||||||

| FIX-IT, overall mean ± SD | 10.3 ± 2.7 | 8.9 ± 3.0 | 1.0 (0.1 to 1.9) | 98% | 16% | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.1) | >99% | 38% |

| 1.5-month | 7.6 ± 3.3 | 6.7 ± 2.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3-month | 10.7 ± 1.8 | 7.9 ± 2.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6-month | 11.8 ± 0.4 | 10.0 ± 3.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12-month | 11.5 ± 1.1 | 11.4 ± 1.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Secondary | ||||||||

| EQ-5D-3L, overall mean ± SD | 0.88 ± 0.13 | 0.83 ± 0.13 | 0.05 (0.00 to 0.10) | 96% | 44% | 0.05 (0.00 to 0.10) | 96% | 45% |

| 1.5-month | 0.78 ± 0.09 | 0.78 ± 0.10 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3-month | 0.86 ± 0.13 | 0.81 ± 0.15 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6-month | 0.93 ± 0.13 | 0.82 ± 0.12 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12-month | 0.98 ± 0.06 | 0.95 ± 0.11 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| EQ-VAS, overall mean ± SD | 80.5 ± 14.5 | 77.1 ± 14.3 | 3.2 (−5.7 to 12.0) | 76% | 34% | 4.2 (−4.6 to 13.2) | 83% | 43% |

| 1.5-month | 70.4 ± 16.1 | 71.5 ± 12.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3-month | 79.8 ± 12.3 | 79.1 ± 13.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6-month | 83.8 ± 10.7 | 70.5 ± 13.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12-month | 88.2 ± 12.3 | 88.9 ± 12.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RUST, mean ± SD | 7.8 ± 3.0 | 7.4 ± 2.8 | 0.1 (−0.8 to 1.1) | 59% | 0% | 0.9 (0.2 to 1.7) | >99% | 6% |

| 1.5-month | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3-month | 7.3 ± 1.9 | 7.7 ± 0.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6-month | 7.5 ± 2.6 | 7.5 ± 1.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12-month | 10.7 ± 1.9 | 10.6 ± 2.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Malunion, no. (%) | 3 (9.7%) | 8 (33.3%) | −22.1% (−42.6% to −1.7%) | 98% | 87% | −15.7% (−30.2% to −1.5%) | 98% | 79% |

| Nonunion, no. (%) | 3 (9.7%) | 2 (8.3%) | 0.0% (−16.4% to 15.5%) | 47% | 23% | −1.6% (−15.1% to 10.8%) | 59% | 29% |

| Deep infection, no. (%) | 4 (12.9%) | 3 (12.5%) | 0.0% (−19.3% to 17.1%) | 49% | 30% | 0.0% (−17.6% to 18.6%) | 51% | 37% |

| Superficial infection, no. (%) | 6 (19.4%) | 10 (41.7%) | −20.8% (−44.0% to 2.9%) | 96% | 82% | −11.6% (−26.3% to 3.4%) | 93% | 80% |

| Wound healing, no. (%) | 3 (9.9%) | 2 (8.3%) | 0.8% (−16.3% to 17.4%) | 48% | 12% | −1.5% (−14.3% to 10.4%) | 59% | 28% |

Note: The informative priors and pre-specified minimal clinically important difference (MCID) are based on an effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.5 as observed in: Foote CJ, Guyatt GH, Vignesh KN, Mundi R, Chaudhry H, Heels-Ansdell D, Thabane L, Tornetta P 3rd, Bhandari M. Which Surgical Treatment for Open Tibial Shaft Fractures Results in the Fewest Reoperations? A Network Meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015 Jul;473(7):2179–92.

The effect size values are scaled below for each study outcome.

FIX-IT = 1.5-point; EQ-5D-3L = 0.05-point; EQ-VAS = 5-point; RUST = 1.5-point; malunion = 10% absolute difference; nonunion = 5% absolute difference; deep surgical site infection = 5% absolute difference; superficial infection = 5% absolute difference; wound healing = 5% absolute difference.

IM, intramedullary; CrI, credible interval.

Figure 2.

Temporal trends in a) FIX-IT score, b) EQ-5D-3L, c) EQ-VAS, and d) RUST score by treatment arm.

Figure 3.

Probability of improved FIX-IT score within 12 months of injury with intramedullary nailing versus external fixation as estimated using a Bayesian analysis with neutral priors.

Secondary Outcomes

Intramedullary nailing improved EQ-5D-3L by 0.05-points (95% CrI, 0.00 to 0.10) and the EQ-VAS by 3.2 points (95% CrI, −5.7 to 12.0) within 12 months of surgery compared with the external fixation (Table 2, Figure 2). The models suggest a high probability of improved HRQoL with intramedullary nailing (EQ-5D-3L, 96%; EQ-VAS, 76%). However, the likelihood that the treatment benefits exceeded clinically important differences (0.05-points for EQ-5D-3L and 5-points for EQ-VAS) was less than 50%.

Within 12 months of injury, the RUST score was not substantially different between treatment groups (0.1-points; 95% CrI, −0.8 to 1.1) (Table 2, Figure 2). Based on these data, the probability that intramedullary nailing has a greater than null treatment effect is 59%.

Patients allocated to intramedullary nailing had fewer malunions (10% vs. 33%; absolute risk reduction, 22.1%; 95% CrI −42.6% to 1.7%) and superficial infections (19% vs. 42%; absolute risk reduction,20.8%; 95% CrI −44.0% to 2.9%) than patients in the external fixation group (Table 2). The probability of any treatment benefit with intramedullary nailing compared with external fixation for malunions was 98% and 96% for superficial infections. Though not powered for statistical comparison, for those patients who experienced malunion in the external fixation group, the average coronal and sagittal malalignment was 7.1° (± 3.3°) and 10.0° (± 6.5°), respectively. For the patients who experienced malunion in the intramedullary nail group, the average coronal and sagittal malalignment was 8.4° (± 1.8°) and 1.6° (± 1.9°), respectively. Two patients in the external fixation group experienced severe malunions of greater than 15° angular deformity, and both were in the sagittal plane. We observed similar risks and probability of treatment benefits between treatment groups for nonunions (10% vs. 8%; prob. of benefit, 47%), deep infections (13% vs. 13%; prob. of benefit, 49%), and wound healing (10% vs. 8%; prob. of benefit, 48%).

DISCUSSION

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find a clinically important difference in functional outcome for open tibial shaft fractures in Uganda treated with intramedullary nail versus external fixation. This is the first orthopaedic randomized clinical trial conducted in Uganda, and these data will help guide the treatment and research of these devastating injuries in the region.

Despite the ubiquity of the injury, little research has been conducted on this fracture in sub-Saharan Africa. Esan et al17 conducted a non-randomized study comparing unreamed intramedullary nail versus external fixation for open tibial fractures in southwest Nigeria. The authors noted an increased incidence of deep infection in the external fixation group (35%) versus the intramedullary nail group (11%) but no difference in time-to-union. Though a limited sample size (n = 20 per group) and possible selection bias due to a non-randomized design, the results favor intramedullary nailing in a low-resource environment based on a lower deep infection rate.

In Tanzania, the partnership between Muhimbili Orthopaedic Institute and the University of California San Francisco recently reported a large randomized trial comparing hand-reamed intramedullary nails versus external fixation for open tibial fractures.11 Over 200 patients completed the 1-year follow-up. Contrary to the study in Nigeria but consistent with our results, the authors found no evidence of a difference in deep infection rates (intramedullary nail: 13.5% vs. external fixation: 11.8%, p = 0.84). The study in Tanzania also observed no significant difference in superficial surgical site infection (intramedullary nail: 8.1% vs. external fixation: 7.2%). In contrast, we noted a 21% higher risk for superficial infection in the external fixation group. The conflicting results might be explained by differences in post-surgical care expertise between our regional hospital and the ward at Muhimbili Orthopaedic Institute.

The malunion risk was a notable secondary outcome that favored the intramedullary nail group (9.7% vs. 33.3%). We observed similar magnitudes of malalignment between the groups in the coronal plane, but in the sagittal plane, the external fixation group appeared to be more at risk of severe deformity. Though this study was not powered to detect such a difference, it is likely a worthwhile recommendation to pay particular attention to the risk of malalignment when treating these fractures definitively with external fixation.

A significant strength of our study was the focus on functional outcomes. Given the demographics of the patients who sustain these injuries, returning to work after an open tibial fracture is often the difference between a positive outcome and destitution. Although treatment with an intramedullary nail did not result in a significant functional benefit at 12 months, recovery trajectory likely plateaued faster in the intramedullary nail group. This observation was also consistent with our HRQoL outcomes and echoed by Haonga et al.11 Though not as widely used as the Short Form-36 (SF-36) or the Short Musculoskeletal Function Assessment (SMFA), we found the FIX-IT to be easy to translate and administer in the local language, and the measure has proven reliability and correlates well with the SF-36.12 Additionally, we deemed the EQ-5D-3L, though not specifically a musculoskeletal assessment, to be easiest to translate, comprehend, and administer. Further, the measure has proven validity and reliability in sub-Saharan Africa.13

Importantly, the trajectory of recovery for the primary, functional outcome measure was steeper for the intramedullary nail group over the group treated with external fixation. This finding might have critical socioeconomic implications in low- and middle-income countries. Indeed, patients in Uganda who sustain a lower extremity long bone fracture can expect to lose 88% of their pre-injury annual income in the 12 months following the fracture.2 If treatment with an intramedullary nail can be performed expeditiously and safely, this treatment might be desirable if it returns a patient, who is often the sole income-earner for their family,3 back to work faster. However, this benefit might be obviated if the cost of the intramedullary nail implant is prohibitive to the patient versus an external fixator, which might be provided at a lesser cost since they are frequently reused. Though we were not able to quantify such variables in the present study, an important factor in the timely operative treatment of fractures in Uganda includes the patient’s ability to raise the funds required for the surgery. This issue, amongst other obstacles, contributes to a situation where just over half of lower extremity fractures deemed ‘operative’ are able to actually receive an operation.3 We found that treatment with external fixation achieved reasonable results, supporting its use as definitive treatment if it is the only expedient option available.

In the present study, we noted no difference in tibial healing judged by the RUST score at any time point. This result contrasts the study from Tanzania,11 which found a 1-point difference in modified RUST scores favoring intramedullary nailing at 1 year. Though the modified RUST score had not yet been evaluated at the outset of our study, it recently has proven reliability and validity amongst North American and Tanzanian surgeons.18 The difference in findings might be attributable to the modified RUST, including categories of cortical evaluation that include ‘bridging callus present’ and ‘non-bridging callus present’ versus the original RUST in which no differentiation was made between the two. This increased granularity might explain the discrepancy. On the whole, however, both studies found intramedullary nail and external fixation treatment to result in radiographic outcomes that were, on average, healed by 1 year.

Limitations of this study include limited follow-up, especially in the external fixation group. When examining the feasibility of this study, we noted that approximately 40% of participants were able to complete 1-year follow-up.19 Barriers to follow-up included prohibitive transportation costs and community pressure to turn to traditional forms of treatment (i.e., local ‘bone-setters’). Although we were initially concerned that traditional forms of treatment would present challenges with the recruitment of patients, we discovered that some patients continued to see them as a viable alternative healthcare professional for follow-up purposes, even when complications arose, potentially causing some of the observed attrition. For this study, treatment was provided free of charge to the patient. The option for free treatment might have aided in recruitment, but it does not necessarily reflect the reality of orthopaedic care in Uganda, where two of the main determinants of receiving operative care are social capital and financial leveraging.7 Another factor that does not necessarily reflect the ‘status quo’ of orthopaedic care is that all included patients received timely antibiotics, debridement, and surgery. Though this study focused on two common methods of surgical fixation, perhaps the main driver of the satisfactory results achieved by both groups was the administration of appropriate antibiotics followed by operative irrigation and debridement within 24 hours of presentation to the emergency department.

In conclusion, we found that treatment of open tibial shaft fractures with an unreamed intramedullary nail does not result in clinically important improvements in functional outcomes in rural Uganda. However, there is likely an important reduction in malunion and superficial infection with intramedullary nailing. Definitive treatment with external fixation remains a viable option, especially if cost or other barriers to intramedullary nailing are prohibitive to the patient’s care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research staff involved in collecting and entering the trial data, including Agnes Tumukunde, Buruno Habasa, Dimitrius Marino, Zachary Hannan, and Abdulai Bangura.

Funding

N. N. O’Hara reported receiving stock or stock options from Arbutus Medical, Inc. unrelated to this research. G. P. Slobogean reported receiving research funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the US Department of Defense, and the National Institutes of Health unrelated to this research; serving as a paid consultant with Smith & Nephew and Zimmer Biomet unrelated to this research; and receiving personal fees from Nuvasive Orthopaedics unrelated to this research.

The study received funding from the AO Alliance Foundation, an AOTrauma North America Resident Research Grant (Grant #R16RESRCH - UBC), and the UBC Branch for International Surgical Care. The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: # PACTR202007730039055

Conflict of Interest

The remaining authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.Johal H, Schemitsch EH, Bhandari M. Why a decade of road traffic safety? J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28 Suppl 1:S8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Hara NN, Mugarura R, Potter J, et al. Economic loss due to traumatic injury in Uganda: the patient’s perspective. Injury. 2016;47:1098–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Hara NN, Mugarura R, Potter J, et al. The socioeconomic implications of isolated tibial and femoral fractures from road traffic injuries in Uganda. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duan X, Al-Qwbani M, Zeng Y, et al. Intramedullary nailing for tibial shaft fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD008241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foote CJ, Guyatt GH, Vignesh KN, et al. Which surgical treatment for open tibial shaft fractures results in the fewest reoperations? A network meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:2179–2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kisitu DK, Eyler LE, Kajja I, et al. A pilot orthopedic trauma registry in Ugandan district hospitals. J Surg Res. 2016;202:481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephens T, Mezei A, O’Hara NN, et al. When surgical resources are severely constrained, who receives care? Determinants of access to orthopaedic trauma surgery in Uganda. World J Surg. 2017;41:1415–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Hara NN, O’Brien PJ, Blachut PA. Developing orthopaedic trauma capacity in Uganda: Considerations from the Uganda Sustainable Trauma Orthopaedic Program. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29 Suppl 10:S20–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Neill KM, Greenberg SL, Cherian M, et al. Bellwether procedures for monitoring and planning essential surgical care in low- and middle-income countries: caesarean delivery, laparotomy, and treatment of open fractures. World J Surg. 2016;40:2611–2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhandari M, Guyatt GH, Swiontkowski MF, et al. Surgeons’ preferences for the operative treatment of fractures of the tibial shaft. An international survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:1746–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haonga BT, Liu M, Albright P, et al. Intramedullary nailing versus external fixation in the treatment of open tibial fractures in Tanzania: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102:896–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhandari M, Wasserman SM, Yurgin N, et al. Development and preliminary validation of a Function IndeX for Trauma (FIX-IT). Can J Surg. 2013;56:E114–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chokotho L, Mkandawire N, Conway D, et al. Validation and reliability of the Chichewa translation of the EQ-5D quality of life questionnaire in adults with orthopaedic injuries in Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2017;29:84–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Group EuroQol. EuroQol - A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whelan DB, Bhandari M, Stephen D, et al. Development of the radiographic union score for tibial fractures for the assessment of tibial fracture healing after intramedullary fixation. J Trauma. 2010;68:629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2020: https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esan O, Ikem IC, Oginni LM, Esan OT. Comparison of unreamed interlocking nail and external fixation in open tibia shaft fracture management. West Afr J Med. 2014;33:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coburn A, Shearer D, Albright P, et al. Evaluating reliability and validity of the modified radiographic union scale for tibia (mRUST) among North American and Tanzanian surgeons. OTA Int. 2021;4:e093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kisitu DK, Stockton DJ, O’Hara NN, et al. The feasibility of a randomized controlled trial for open tibial fractures at a regional hospital in Uganda. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.