Abstract

Methanococcus voltae is a flagellated member of the Archaea. Four highly similar flagellin genes have previously been cloned and sequenced, and the presence of leader peptides has been demonstrated. While the flagellins of M. voltae are predicted from their gene sequences to be approximately 22 to 25 kDa, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis of purified flagella revealed flagellin subunits with apparent molecular masses of 31 and 33 kDa. Here we describe the expression of a M. voltae flagellin in the bacteria Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Both of these systems successfully generated a specific expression product with an apparently uncleaved leader peptide migrating at approximately 26.5 kDa. This source of preflagellin was used to detect the presence of preflagellin peptidase activity in the membranes of M. voltae. In addition to the native flagellin, a hybrid flagellin gene containing the sequence encoding the M. voltae FlaB2 mature protein fused to the P. aeruginosa pilin (PilA) leader peptide was constructed and transformed into both wild-type P. aeruginosa and a prepilin peptidase (pilD) mutant of P. aeruginosa. Based on migration in SDS-PAGE, the leader peptide appeared to be cleaved in the wild-type cells. However, the archaeal flagellin could not be detected by immunoblotting when expressed in the pilD mutant, indicating a role of the peptidase in the ultimate stability of the fusion product. When the +5 position of the mature flagellin portion of the pilin-flagellin fusion was changed from glycine to glutamic acid (as in the P. aeruginosa pilin) and expressed in both wild-type and pilD mutant P. aeruginosa, the product detected by immunoblotting migrated slightly more slowly in the pilD mutant, indicating that the fusion was likely processed by the prepilin peptidase present in the wild type. Potential assembly of the cleaved fusion product by the type IV pilin assembly system in a P. aeruginosa PilA-deficient strain was tested, but no filaments were noted on the cell surface by electron microscopy.

Flagellation is widespread among members of the domain Archaea, and it appears to be a unique motility system distinct from that of the other major prokaryotic lineage, the Bacteria (18). Significantly, no homologs of bacterial flagellins or any bacterial flagellum-related structural proteins (hook, rods, rings, hook-associated proteins, etc.) have been found in the sequences of the complete genomes of the flagellated archaea Methanococcus jannaschii (8), Archaeoglobus fulgidus (27), and Pyrococcus horikoshii (24). Flagellation in the archaea has best been studied in the mesophilic methanogen Methanococcus voltae (3, 17, 21, 22). M. voltae has been shown to possess four highly similar flagellin genes (flaA, flaB1, flaB2, and flaB3 [21]) which are followed immediately by a number of downstream open reading frames at least some of which have been shown to be cotranscribed with the flagellins (21, 47). Homologs of these downstream genes have been found in the immediate vicinity of the flagellin genes in the complete genome sequences of A. fulgidus (27), P. horikoshii (24), and M. jannaschii (8). None of these genes are found in the complete genome of the nonflagellated methanogen Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (38).

While four flagellin genes are found in M. voltae and all are transcribed to various degrees (21), only two flagellin bands are detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of KBr gradient-purified flagellar filaments (22). Evidence provided by mutational (17), transcriptional (21), and N-terminal (23) analyses have implicated the product of flaB2 as one of the major flagellins. These flagellins migrate in SDS-PAGE as proteins of approximately 31 and 33 kDa. This size is approximately 10 kDa larger than predicted from the gene sequences (FlaB2 is predicted to be 22.8 kDa [21]) and suggests a posttranslational modification such as glycosylation, as found in numerous other archaeal flagellins (4, 39, 50). While no posttranslational modifications have been described for the flagellins of M. voltae and the flagellins do not stain positively for glycoprotein by the periodic acid-Schiff or thymol sulfuric acid staining procedure (18), the deduced flagellin amino acid sequences do possess a number of the carbohydrate attachment consensus sequences Asn-X-Ser/Thr (21), which suggests that the flagellins may have a type of carbohydrate attachment that resists detection by conventional gel staining methods. Evidence from mutant studies suggests that the fully unmodified form of M. voltae flagellin may migrate at approximately 20 kDa (17). We therefore anticipated the migration of flagellin FlaB2 to be closer to that expected for unmodified flagellins when expressed in heterologous hosts in which flagellin modification is less likely to occur.

On an amino acid level, the flagellins of the archaea show no homology to bacterial flagellins but instead are highly similar to bacterial type IV pilins in their N termini (13). Like type IV pilins, archaeal flagellins are translated with short leader peptides which are cleaved before the flagellins are incorporated into the flagellum filament (1, 21). Here, we describe experiments which generate a source of M. voltae FlaB2 preflagellin in the bacterial host Escherichia coli, in which the leader peptide remained uncleaved. Also, we have expressed the flagellin gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which, unlike most E. coli strains, possesses a type IV pilin system (43). Expression in this system allowed us to test the possibility that archaeal flagellin is recognized as a substrate by the type IV pilus system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbial strains and growth conditions.

M. voltae PS (obtained from G. D. Sprott, National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) was grown in Balch medium 3 at 37°C in 1-liter bottles modified to accept serum bottle stoppers as previously described (22). Cultures were shaken at 100 rpm under an atmosphere of CO2-H2 (20%-80%) for 36 to 48 h. E. coli strains (Table 1) were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (36) supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical Co., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) when necessary. P. aeruginosa strains (Table 1) were grown at 37°C in tryptic soy broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with carbenicillin (200 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and tetracycline (200 μg/ml; Sigma) when necessary.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and strains used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| M. voltae | ||

| PS | Wild-type strain | |

| P-2 | Flagellum-deficient mutant of M. voltae PS | 17 |

| E. coli | ||

| BL21(DE3)/pLysS | Host for T7-based expression vectors | 45 |

| DH5α | ||

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAK | Wild-type host | |

| PAK-DΩ | Ω insertion mutation into pilD (prepilin peptidase gene) | 28 |

| PAO1 PilA− | Mutation in major pilin (PilA) | J. S. Mattick |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKJ41 | Source of M. voltae flaB2 gene; missing 5′ 15 nucleotides | 21 |

| pAW102 | contains 1.24-kb HindIII fragment which encodes P. aeruginosa pilA gene and promoter in pUCP vector | J. S. Mattick |

| pT7-7 | T7 promoter-based expression vector | 46 |

| pKJ91 | pT7-7 with flaB2 gene in NdeI site; same orientation as T7 promoter | This study |

| pKJ139 | As above with flaB2 excised by XbaI and religated in opposite orientation | This study |

| pUCP18/19 | E. coli-P. aeruginosa shuttle vector based on pUC18/19 | 37 |

| pKJ118 | pUCP18 with flaB2 gene excised from pKJ91 in XbaI site; fragment in same orientation as lac promoter | This study |

| pKJ119 | As above with flaB2 in opposite orientation | This study |

| pKJ156 | pUCP18 with fusion of pilA promoter, ribosome binding domain, leader peptide, and +1 Phe to flaB2 mature flagellin coding region | This study |

| pKJ248 | pUCP19 with fusion of pilA promoter, ribosome binding domain, leader peptide, +1 Phe, and +5 Glu to flaB2 mature flagellin coding region | This study |

Molecular techniques.

PCR was performed on a MiniCycler (MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.), using either Pwo DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim) or Taq DNA polymerase and reagents from Life Technologies, Gibco-BRL (Burlington, Ontario, Canada) under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min; and a final cycle of 72°C for 5 min. For amplification of the M. voltae flagellin gene flaB2, plasmid pKJ41 with a 1.3-kb EcoRI fragment carrying all but the extreme 5′ 15 bp (21) was used as the template for amplification by primers designed to reconstruct the 5′ end of the gene and to generate NdeI sites at the start codon and downstream of the stop codon [(forward, flaB2(N)for (5′GGAATTCCATATGAAAATAAAAGAATTCATGAGTAACAAAAAAGGTGC); reverse, flaB2(N)rev (5′GGAATTCCATATGTCACTATTGTAATTGAACTACTTTTGAATCG)]. In addition to the TAG stop codon, a TGA stop codon was incorporated prior to the NdeI site to ensure proper translation termination. The PCR-reconstructed flagellin gene was cloned into NdeI-digested, dephosphorylated pT7-7, which was then transformed into CaCl2-competent E. coli DH5α. pT7-7 with the insert in the correct orientation with respect to the T7 promoter was purified and then digested with XbaI. A 725-bp fragment containing flaB2 and a ribosome binding site eight nucleotides upstream from the start codon (Fig. 1) was gel purified with Prep-A-Gene (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and cloned into XbaI-digested pT7-7 as described above. Cells harboring pT7-7 with the insert in the opposite direction with respect to the T7 promoter were further used as a negative control. The XbaI fragment was also cloned into pUCP18 and transformed into P. aeruginosa strains rendered competent by three successive washes in ice-cold 0.15 M MgCl2 (35). Plasmids and host strains for induction in P. aeruginosa were kindly provided by John S. Mattick, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

FIG. 1.

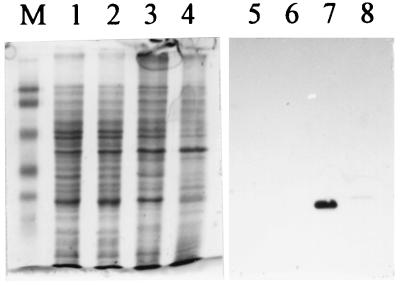

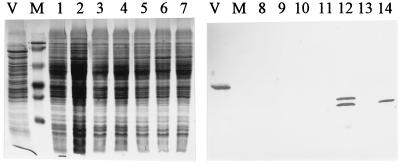

Specificity of polyclonal antibody raised in chickens against the FlaB2 flagellin of M. voltae. Lanes: 1 and 3, wild-type M. voltae whole cells; 2 and 4, M. voltae P-2 (17), a nonflagellated mutant in which the flagellin gene family has been disrupted by insertional mutagenesis; M, Bio-Rad prestained SDS-PAGE standards (low range): phosphorylase b (103 kDa), bovine serum albumin (81 kDa), ovalbumin (47.7 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (34.6 kDa), soybean trypsin inhibitor (28.3 kDa), and lysozyme (19.2 kDa). Lanes 1 and 2 are Coomassie blue stained; lanes 3 and 4 are immunoblots. For the immunoblot, primary antibody (chicken immunoglobulin Y) was used at a dilution of 1:5,000. Secondary antibody was used at a dilution of 1:50,000. Immunoblot lanes contained 1/100 of protein loaded into Coomassie blue-stained lanes. Note the strong, specific reaction with the flagellins in the wild-type cells and lack of reaction against the total cell protein of the flagellin mutant.

A hybrid construct in which the promoter, ribosome binding site, and leader peptide coding region of P. aeruginosa pilA was fused to the region of M. voltae flaB2 which encodes only the mature portion of the protein (i.e., following leader peptide cleavage) was also constructed. This was accomplished by PCR using a forward primer possessing an exogenous 5′ XbaI site [pilA(X) for (5′GCTCTAGAAGCTTTCCCTGTCCAGG)] specific to a region about 460 bp upstream of pilA on the plasmid pAW102 and a reverse primer [pilA(N)rev (5′GGAATTCCATATGTATCTCCATTGATATGTATAGG)] specific for a region near the pilA translation start site which converts the three bases upstream of the ATG to CAT in order to generate an NdeI site. As well, flaB2 of M. voltae was amplified with a primer specific for the region near the XbaI site downstream of flaB2 in the pT7-7 construct described above [flaB2(X)rev (5′GCTCTAGATCACTATTGTAATTGAACTACTTTTGAATCG)] and a primer [flaB2/pilAlp(N)for (5′GGAATTCCATATGAAAGCTCAAAAAGGCTTCTCAGGAATTGGTACCT TAATAG)] which assembles the pilA leader peptide coding region onto the portion of flaB2 which encodes only the mature flagellin and also changes the first amino acid residue after the cleavage site to a phenylalanine (as in PilA) from an alanine. Also, this primer converts the three bases around the ATG start site to an NdeI site. PCR was performed as described above. Both resulting PCR fragments were digested with NdeI, cleaned, and ligated together overnight at 16°C. This ligation mix was used as a PCR template for amplification, as described above, using primers pilA(X)for and flaB2(X)rev to amplify the full-length ligated hybrid. This hybrid (pilAlflaB2 fusion) was digested with XbaI and ligated into XbaI-digested pUCP18. Both orientations relative to the lac promoter were maintained. The same strategy was used to form a pilin-flagellin fusion in which the +5 position of the flagellin portion was changed to glutamic acid. For this PCR, the flaB2/pilAlp(N)for primer was replaced with the primer fusiongluF (5′GGAATTCCATATGAAAGCTCAAAAAGGCTTCTCAGGAATTGAGACCTTAATAG).

Plasmids were purified by the Promega Wizard Miniprep system (Fisher Scientific, Nepean, Ontario, Canada). Restriction endonucleases, calf intestinal phosphatase, and ligase were also purchased from Promega. Strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1.

Production of polyclonal antibodies.

FlaB2 was expressed in E. coli DH5α and separated by SDS-PAGE. The band corresponding to FlaB2 was excised. A 1-ml volume containing macerated acrylamide pieces containing FlaB2 (approximately 500 μg) and the adjuvant Quill A (100 μg; Cedarlane Laboratories Limited, Hornby, Ontario, Canada) was injected subcutaneously into 1-year-old white leghorn chickens. Boosts of the same mixture of FlaB2 and adjuvant were given subcutaneously on days 10, 20, and 34. A final injection was given on day 65, and antibodies were isolated from the eggs laid at least 1 week following the final injection. Antibodies were produced by RCH Antibodies, Sydenham, Ontario, Canada.

Induction of M. voltae flagellin synthesis.

E. coli and P. aeruginosa were grown overnight as described above, then inoculated at 1% (vol/vol) into 25 ml of fresh medium, and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 to 0.6. Isopropylthio-β-d-galactoside (IPTG; Life Technologies) was added to 2 mM, and growth was allowed to continue. For growth analyses, 0.3-ml samples were removed at 30-min intervals for spectrophotometric analysis. For detection of induction products, whole cells were prepared for SDS-PAGE as described by Laemmli (30). Samples were electrophoresed at 150 V for 1.5 h (Hoefer Mighty Small; Hoefer Scientific, San Francisco, Calif.). Bands were then visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue G-250, followed by destaining in water in a microwave oven (12) or by immunoblotting (48) using a polyclonal antibody raised in chickens against FlaB2 flagellin and shown to be specific (Fig. 1) as a primary antibody. The secondary antibody was a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-chicken (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.) used at a 1:50,000 dilution. Blots were developed with a chemiluminescence kit from Boehringer Mannheim Canada (Laval, Quebec, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vivo and in vitro labeling of flagellin.

The procedure followed for specific labeling of plasmid encoded proteins was similar to that of Watson et al. (49). E. coli strains were inoculated at 1% (vol/vol) into 25 ml of fresh medium as described above. At an OD600 of between 0.5 and 0.6, 0.2-ml aliquots of cells were harvested at 6,000 × g for 5 min and then washed in 1.5 ml of M9 salts (36). Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 1 ml of M9 salts supplemented with 0.5% methionine assay medium (Difco) in a plastic microcentrifuge tube and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. All subsequent incubations were at 37°C unless specified. Cells were induced by addition of IPTG to 2 mM and incubated a further 30 min. A duplicate culture of E. coli harboring pKJ91 was also processed without induction. Rifampin (Boehringer Mannheim) was then added to 200 μg/ml, and incubation continued for a further 30 min. Then 10 μCi of [35S]methionine (Redivue [35S]methionine; >1,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham Life Science, Inc., Oakville, Ontario, Canada) was added, and incubation continued for 10 min. Cells were harvested as described above, resuspended in 200 μl (total volume) of SDS-PAGE sample buffer, heated to 100°C for 5 min, and electrophoresed as described above. Gels were then fixed in 7% acetic acid at 4°C overnight, incubated for 30 min in En3Hance (DuPont, NEN Research Products, Boston, Mass.), dried at 80°C for 1 h in a model 543 gel drier (Bio-Rad), and exposed to Kodak X-Omat AR film (Fisher Scientific).

In vitro analyses of the pT7-7 constructs described in Table 1 were carried out with a linked T7 transcription-translation kit from Amersham Life Science according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each sample was labeled with 40 μCi of [35S]methionine (Redivue [35S]methionine; >1,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham Life Science).

Cell fractionation.

E. coli KJ91 was grown at 37°C overnight in LB containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml and subcultured at 1% (vol/vol) inoculum into medium of the same composition. When the culture reached an OD600 of 0.6, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 2 mM to induce synthesis of flagellin. After a further incubation of 2.5 h, the cells were pelleted and washed in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) containing 10% (wt/vol) sucrose. The cell pellet was resuspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) containing 18% (wt/vol) sucrose, 5 mM EDTA, and 100 μg of lysozyme per ml and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The cells were collected at 8,000 × g/10 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) containing DNase and RNase. The viscous solution was sonicated on ice twice for 30 s each time. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 5,000 × g/10 min. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 20,000 × g/30 min to collect the crude particulate fraction. The supernatant was centrifuged at 80,000 × g/90 min, and the resulting supernatant from this spin was considered the cytoplasm fraction. The crude particulate fraction was layered over a preformed step sucrose gradient as described by Sprott et al. (40). The membrane fraction was collected by syringe and washed once with distilled water. Material which pelleted through the sucrose gradient was also collected and washed once with distilled water.

P. aeruginosa periplasm was extracted by osmotic shock treatment with 0.2 M MgCl2 (15). Cytoplasm and membrane fractions of P. aeruginosa were isolated in a manner similar to that described for E. coli.

Preflagellin peptidase assay.

The assay for preflagellin peptidase activity in M. voltae was based on the prepilin peptidase assay developed for P. aeruginosa (44). The substrate for the assay was the crude particulate fraction of induced KJ91 (overproducing M. voltae FlaB2 with leader peptide) isolated as described above. The source of preflagellin peptidase was a M. voltae membrane fraction. M. voltae cells were grown for 18 h and harvested in a microcentrifuge. The pellet from a total of 6 ml of cells was resuspended in 100 μl of growth medium, and then the cells were lysed by the addition of 1 ml of distilled water. The resulting envelopes were collected by centrifugation for 10 min in an Eppendorf centrifuge. This pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of distilled water and used as the source of preflagellin peptidase. All isolations and assays were performed aerobically. The assay conditions were 6 μl of E. coli KJ91 membranes (12 μg of protein), 1 μl of M. voltae membranes (3 μg of protein), 1 μl of 0.5% cardiolipid (Sigma), and 2 μl of reaction buffer (5× reaction buffer was 125 mM HEPES buffer [pH 7.5] containing 2.5% Triton X-100). The reaction was started with the addition of the M. voltae fraction. At each time point, the 10-μl samples were mixed with 15 μl of electrophoresis sample buffer and immediately boiled for 5 min. For detection of peptidase activity, 2 μl of each sample was examined by Western blotting using a 1/10,000 dilution of the chicken polyclonal antibody raised to the M. voltae flagellin as primary antibody.

N-terminal sequence analysis.

Proteins to be sequenced were resolved by SDS-PAGE as described above and transferred onto Immobilon P (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) as previously described (48). The membrane was briefly stained with 0.1% Coomassie blue R250, destained in 50% methanol, and rinsed thoroughly with distilled water. Protein bands were sequenced by David Watson, National Research Council of Canada.

RESULTS

Induction of E. coli strains.

E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS as well as the same strain carrying pT7-7, pKJ91, or pKJ139 were grown to log phase, induced, and analyzed by both optical density and light microscopy (data not shown). The strain carrying pKJ91(pT7-7 with the flaB2 gene in the same orientation as the T7 promoter) began to lyse approximately 1 h postinduction, as determined both by a decrease in OD600 and by light microscopy, which revealed spheroplasts and cell debris. When the same strain was processed without induction, no lysis was observed. Induction of the control strains did not result in cell lysis. SDS-PAGE analysis revealed an induction product from the strain carrying pKJ91 migrating at approximately 26.5 kDa detected by both Coomassie brilliant blue staining and immunoblotting with antisera raised to the FlaB2 flagellin of M. voltae (Fig. 2). This induction product was detected only in E. coli harboring pT7-7 with flaB2 in the same orientation as the T7 promoter. Also, the 26.5-kDa band was not detected when this strain was examined uninduced. N-terminal sequencing of this induced protein revealed the sequence MKIKEFMSNK, which indicated that it was the product of flaB2 and that the short leader peptide recognized by M. voltae was not cleaved from the protein by E. coli.

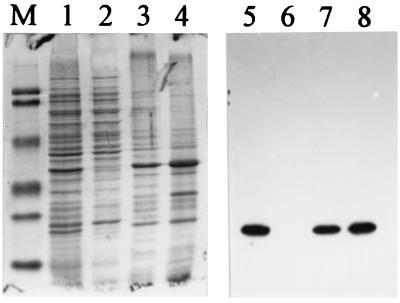

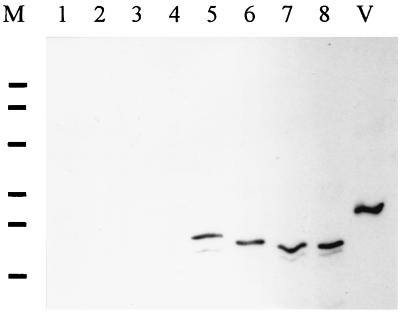

FIG. 2.

Inducible synthesis of flaB2 in E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS. Lanes: 1 and 5, cells with no added plasmid, induced; 2 and 6, cells carrying pKJ139, induced; 3 and 7, cells carrying pKJ91, induced; 4 and 8, cells carrying pKJ91, uninduced; M, molecular weight standards. Lanes 1 through 4 are Coomassie blue stained; lanes 5 through 8 are immunoblots. Immunoblot lanes contain 1/100 of the protein loaded into the Coomassie blue-stained lanes.

Detection of the induction product was also accomplished by [35S]methionine incorporation analysis. When cellular RNA polymerase expression was inhibited and T7 polymerase expression was induced, only the product of the pT7-7 insert should have been transcribed. A 26.5-kDa band, in addition to several lower-molecular-weight proteins, was detected in the strain carrying pKJ91 (data not shown). These smaller polypeptides were also often seen in SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblots of induced cells carrying pKJ91 and likely represent proteolytic degradation of the protein. In vitro labeling of the induction product was also performed. Incubation of plasmid pKJ91 in a rabbit reticulocyte system resulted in a unique radiolabeled protein band which migrated at approximately 25 kDa in SDS-PAGE (data not shown). All other labeled bands were common to all induced control plasmids, including pT7-7 alone and pKJ138.

In an attempt to localize the induction product in E. coli, induced cells were harvested and fractionated (Fig. 3). Detection of the expressed flagellin in fractionated samples was accomplished by Coomassie brilliant blue staining of SDS-polyacrylamide gels and also by immunoblotting. Preliminary experiments indicated that the flagellin was found associated with the particulate fraction and not in the cytoplasm, periplasm, or precipitated culture supernatant. To distinguish between membrane and inclusion body location, the particulate fraction was separated on a sucrose gradient. Approximately half of the flagellin banded with the membrane fraction, while the remainder pelleted through the gradient, indicating it may be associated with inclusion bodies.

FIG. 3.

Localization of FlaB2 in fractionated E. coli cells carrying pKJ91, 2.5 h after induction with IPTG. Lanes: 1 and 5, whole-cell lysate; 2 and 6, cytoplasmic fraction; 3 and 7, membrane fraction from sucrose gradient; 4 and 8, pellet from sucrose gradient; M, molecular weight standards. Lanes 1 through 4 are Coomassie blue stained; lanes 5 through 8 are immunoblots generated by using a primary antibody dilution of 1:5,000. The immunoblots contained 1/100 of the protein used for the Coomassie blue-stained gel.

Preflagellin peptidase activity.

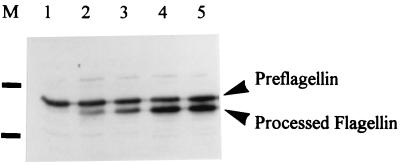

One of the potential uses for the overexpressed archaeal preflagellin is as substrate for the detection and purification of archaeal preflagellin peptidase. A simple assay system, based on that developed for detection of prepilin activity, involving mixing of membranes of E. coli overproducing the preflagellin, with M. voltae membranes, in the presence of cardiolipid and a buffer containing Triton X-100, clearly showed the effectiveness of the overexpressed preflagellin in detecting archaeal preflagellin peptidase activity. Western blot analysis of the preflagellin peptidase assay samples (Fig. 4) demonstrated the appearance, with time, of an additional cross-reactive band that migrated more quickly than the preflagellin in SDS-PAGE. This additional band increased in intensity with time, and its size corresponded to that expected for the processed flagellin. The N-terminal sequence determined for this smaller, cross-reactive band was Ala-Ser-Gly-Ile-Gly-Thr-Leu/Gly-Ile-Val-Phe, indicating that it was indeed the product of FlaB2 after cleavage of the 12-amino-acid leader sequence.

FIG. 4.

Demonstration of preflagellin peptidase activity in M. voltae membranes. The reaction tubes contained 6 μl of crude membranes from induced E. coli KJ91, 1 μl of M. voltae membranes, 2 μl of 125 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) containing 2.5% Triton X-100, and 1 μl of 0.5% cardiolipid. The reaction was started by the addition of M. voltae membranes. Samples were removed at 0, 2, 10, 20, and 30 min and then immediately mixed with 15 μl of electrophoresis sample buffer and boiled for 5 min; 2-μl aliquots were examined by immunoblotting using a primary antibody dilution of 1:10,000. Lanes: 1, 0 min; 2, 2 min; 3, 10 min; 4, 20 min, 5, 30 min. Positions of 28.3- and 19.2-kDa markers indicated in lane M.

Induction of P. aeruginosa strains.

Due to the presence of short leader peptides in both the type IV pilin superfamily and the flagellins of M. voltae, as well as the sequence similarity of archaeal flagellins and type IV pilins at their N termini (13), we attempted to express the flaB2 gene in a host which possessed a type IV pilin system. This would allow us to determine if the type IV prepilin peptidase could process the methanococcal preflagellin and to see if archaeal flagellin could substitute for type IV pilin and be assembled into a surface structure. To this end, native FlaB2 as well as two P. aeruginosa pilin-M. voltae FlaB2 fusions were tested (Fig. 5).

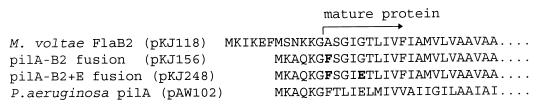

FIG. 5.

Alignment of N-terminal sequences of the M. voltae FlaB2 flagellin, the P. aeruginosa PilA pilin, and the products of the two fusion constructs with their leader peptides intact. The position of leader peptide cleavage shown represents that known for the M. voltae and P. aeruginosa proteins and predicted for the fusions. Shown in boldface are amino acid residues of interest in the fusion proteins: the +1 position change of the mature M. voltae FlaB2 to a phenylalanine from an alanine in both fusions, and the change in the +5 position of the mature FlaB2 from an glycine to a glutamic acid in the fusion encoded by pKJ248.

By using the E. coli/P. aeruginosa shuttle vector pUCP18 (37), an XbaI fragment containing the flaB2 coding sequence downstream of a ribosome binding site was prepared from pKJ91 described above and was inserted in both orientations into pUCP18. These constructs (Table 1), named pKJ118 (same orientation as the lac promoter) and pKJ119 (opposite orientation to the lac promoter), were then transformed into P. aeruginosa PAK. When the flaB2 gene was inserted in the same orientation as the lac promoter (pKJ118), an induction product was detected in P. aeruginosa in immunoblots but not by Coomassie staining (Fig. 6). The induction product often formed a doublet in immunoblots; however, the lower band varied in intensity between experiments and likely represents a stable degradation product. The upper band migrated as approximately 26.5 kDa. No such product could be detected when the flaB2 gene was inserted in the opposite orientation. When examined on the same SDS-polyacrylamide gel (not shown), the induction products from E. coli and P. aeruginosa appeared to migrate to the same position, suggesting that, as in E. coli, the leader peptide of the flagellin expressed in P. aeruginosa remains uncleaved. The product is not exported since no material could be detected in precipitated culture supernatant (not shown).

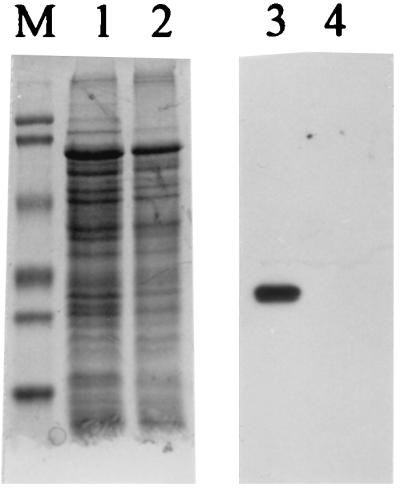

FIG. 6.

Expression of flaB2 and the pilin-flagellin fusion product in P. aeruginosa wild-type and prepilin peptidase mutant cells. Lanes: V, M. voltae; M, molecular weight markers; 1 and 8, P. aeruginosa PAK; 2 and 9, P. aeruginosa PAK pilD mutant; lanes 3 and 10, P. aeruginosa PAK carrying pUCP18; 4 and 11, P. aeruginosa PAK carrying pKJ119; 5 and 12, P. aeruginosa PAK carrying pKJ118; lanes 6 and 13, P. aeruginosa PAK pilD mutant carrying pKJ156; 7 and 14 P. aeruginosa PAK carrying pKJ156. Lanes 1 to 7 are Coomassie blue stained; lanes 8 to 14 are immunoblots generated by using a primary antibody dilution of 1:10,000. Immunoblots contained 1/10 the protein used for the Coomassie blue-stained gel.

Since it is unlikely that P. aeruginosa cleaved the native leader peptide from the M. voltae FlaB2, the mature flagellin would not have access to the pilus assembly system. Thus, we generated a hybrid flaB2 gene in which the leader peptide and the first amino acid of the mature flagellin were replaced by those of P. aeruginosa PilA (the major pilin). In addition, the region upstream of pilA in P. aeruginosa was included upstream of the hybrid flaB2 to provide the native promoter and ribosome binding site. It was anticipated that this hybrid would act as a substrate for the prepilin peptidase. This construct was ligated into pUCP18 to form pKJ156 and was examined in both wild-type P. aeruginosa PAK cells and mutants which were deficient in the leader peptidase (pilD mutants). In wild-type cells, we noted an expression product of approximately 25 kDa, about 1.5 kDa smaller than the unique protein expressed with the native flaB2 leader peptide (Fig. 6). If the difference in size is due to the smaller, 6-amino-acid leader peptide of pilA compared to the 12-amino-acid leader peptide of flaB2, we would expect a shift of about 700 Da, but if the pilA leader peptide is indeed being cleaved from hybrid flaB2, a shift of approximately 1.3 kDa is expected. The shift in apparent molecular observed is consistent with the pilin leader peptide being cleaved. To examine this more conclusively, the hybrid flagellin gene was transformed into a P. aeruginosa pilD mutant which lacks the leader peptidase. A finding that the gene product in this mutant was similar in size to the product observed in wild-type cells would suggest that in wild-type cells, the leader peptide is not cleaved. A finding that the fusion protein in the prepilin peptidase mutant is larger than the product observed in the wild-type cells would suggest that the leader peptide of the fusion is cleaved in the wild-type cells and that this cleavage is due to the activity of the prepilin peptidase. However, no induction product could be detected by immunoblotting in the pilD mutant (Fig. 6).

Much clearer results were obtained when the pilin-flagellin fusion also included a change in the flagellin portion at position +5. This position in the P. aeruginosa pilin is glutamic acid. Amino acid substitutions at this position in the pilin result in the synthesis of pilin that is processed but not assembled in P. aeruginosa (41). Since our aim was to determine if the P. aeruginosa pilus assembly system would utilize archaeal flagellin as a potential substrate, we prepared a pilin-flagellin hybrid with this +5 change from glycine to glutamic acid. This change at the DNA sequence level results in the loss of the lone KpnI site in the fusion, which was confirmed (data not shown). When the fusion expressed in wild-type and pilD mutant P. aeruginosa cells were subjected to immunoblotting the product was shown to migrate slightly slower in the pilD mutant cells (Fig. 7, lanes 6 and 7), indicating that processing of the fusion (i.e., cleavage of the leader peptide) was taking place in the wild-type cells and that the enzyme involved in the processing was the prepilin peptidase. Also shown in Fig. 7 is the expression of the methanogen flagellin with its native 12-amino-acid leader peptide which is not cleaved in P. aeruginosa cells (lane 5). This product migrated slightly slower than the pilin-flagellin fusion in the pilD mutant cells. This represents the mature flagellin with an extra 12 amino acids which migrates slower than the pilin-flagellin fusion in the pilD mutant (which represents the mature flagellin with an extra 6 amino acids), which in turn migrates slower than the same fusion in the wild-type P. aeruginosa (which represents the mature flagellin with no additional amino acids).

FIG. 7.

Expression of flaB2 and the pilin-flagellin fusion product with the additional position +5 change to glutamic acid in P. aeruginosa wild-type and prepilin peptidase mutant cells. Lanes: M, molecular weight markers; 1, wild-type P. aeruginosa PAK cells; 2, P. aeruginosa PAK pilD mutant cells; 3, PAK carrying pUCP19; 4, PAK pilD mutant carrying pUCP19; 5, PAK carrying pKJ118; 6, PAK pilD mutant carrying pKJ248; 7, PAK carrying pKJ248; 8, PAK carrying pKJ156; V, M. voltae cells. A primary antibody dilution of 1:5,000 was used in the blots.

In an attempt to determine if filaments were being assembled on the surface of cells expressing the hybrid flagellin gene, we examined, by electron microscopy, P. aeruginosa mutants harboring various plasmid constructs (not shown). To avoid possible interference with pili since archaeal flagella are much thinner than bacterial flagella (18), we used a pilin-deficient (pilA) strain as host. The product of the hybrid flaB2 was readily detected by immunoblot analysis of these cells (data not shown) as was the fusion carrying the additional +5 glutamic acid change (not shown), verifying that the gene was being expressed in this host. No filaments, other than flagella, could be detected on pilA cells harboring no plasmids, or on cells in which either the hybrid flaB2 plasmid construct or the hybrid flaB2 plasmid with the additional +5 glutamic acid change was contained (data not shown). Cells into which the native pilA gene on pUCP18 was transformed did possess pili on the cell surface, and these cells were also susceptible to pilus-specific phages.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the experiments described in this report was twofold. First, we wished to develop a reliable source of archaeal flagellin which still had the signal sequence attached. This was shown to be a substrate for the M. voltae preflagellin peptidase and will be useful for further analysis of this enzyme. Second, we wished to design experiments which would test the possibility of the archaeal flagellin being treated as a type IV pilin in heterologous expression studies.

We have expressed the M. voltae native flaB2 flagellin gene in both E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Much better production of FlaB2 was obtained in E. coli than in P. aeruginosa (compare Fig. 3, lane 1, to Fig. 6, lane 5), probably due to the codon usage. M. voltae with a G+C content of 31% utilizes a number of codons that are rarely used in E. coli. Recently, it was observed that poor expression of M. jannaschii proteins in E. coli could be overcome by using E. coli strains carrying a plasmid expressing three rare tRNA species (26). In P. aeruginosa, with an even higher G+C content than E. coli, this codon usage could be expected to be even more problematic.

Sequencing of the N terminus of the expressed protein confirmed that it was the product of the M. voltae flaB2 gene and that the leader peptide was not cleaved by E. coli, and presumably also not by P. aeruginosa. Surprisingly, the overexpressed flagellin migrated at 26.5 kDa, 5 to 7 kDa smaller than the flagellins isolated from purified M. voltae flagella (22). There is much evidence to suggest that the native unmodified forms of archaeal flagellins usually migrate at about 20 kDa (4, 17, 31, 39). Despite expression of this flagellin in bacterial hosts, it appears that some modification may be occurring which results in a product of approximately 26.5 kDa. Particularly interesting is the fact that this modification results in identical migration of the expressed flagellin in both E. coli and P. aeruginosa. While the nature of the putative modification in the bacterial hosts is not known, it has very recently been shown that the flagellins of a-type strains of P. aeruginosa (including preliminary data on strain PAK) are glycosylated (7). The nature of the glycosylation in these pseudomonads is still unknown; the authors believe an O link likely, although there are a number of N-glycosylation sequons (Asn-X-Ser/Thr) in the a-type flagellins (7). The pilins of some P. aeruginosa strains have also been shown to be glycosylated (9). Clearly, P. aeruginosa strains do possess the capability of protein glycosylation. Other examples of posttranslational modifications of bacterial flagellins include glycosylation (10, 34), methylation (14, 20), and phosphorylation (25).

The use of a membrane fraction containing this preflagellin product was shown to be useful in the detection of preflagellin peptidase activity in cell membranes of M. voltae, using methodologies similar to that developed for prepilin peptidase assays in P. aeruginosa (42). The assay system should also be useful in monitoring the purification of the preflagellin peptidase in future work. Since searches of the complete genomes reported for flagellated archaea do not detect homologs to prepilin peptidases, it may be that the preflagellin peptidase represents a new distant relative of known leader peptidases. The overexpressed preflagellin may also act as substrate in the detection of protein fractions responsible for the putative flagellin posttranslational modifications in M. voltae. As well, this product could be used to adsorb flagellin-binding proteins (e.g., flagellin-specific chaperones) from cell extracts. It has been suggested that cytoplasmic chaperones may be required to prevent nonspecific aggregation of the flagellins via their very hydrophobic N termini (18). Cytoplasmic ATP-dependent flagellin-binding proteins have been isolated from both methanogens and extreme halophiles (18, 29).

Type IV pilins from a variety of bacteria show a high degree of sequence homology for approximately the N-terminal 30 amino acids following the signal peptide (11). Thereafter there is little amino acid conservation among many different type IV pilins. Yet in at least certain cases (5, 16, 33), heterologous pilins with this limited stretch of amino acid homology can be recognized by the pilus accessory proteins and assembled into a pilus in P. aeruginosa. We have previously reported that archaeal flagellins have sequence homology to type IV pilins at the extreme N-terminal 20 to 25 amino acids of the mature protein (13). We have also presented other data consistent with an assembly mechanism for archaeal flagella which is different from that for bacterial flagella and which may be similar to that of pili (18). Recently, we reported that a gene, flaI, located just downstream of the flagellins and which may be cotranscribed with the flagellins shares homology with the ATP-binding pilT homologs required for synthesis of a fully functional type IV pilus (2). A homolog of flaI is also found in the immediate vicinity of the flagellin genes in M. jannaschii (8), A. fulgidus (27), and P. horikoshii (24).

P. aeruginosa, while possessing a type IV prepilin peptidase, was not able to cleave the native leader peptide from the M. voltae flagellin. This inability may be in part due to the fact that the pilins of P. aeruginosa are expressed with a leader peptide of only 6 amino acids, compared to 12 for M. voltae FlaB2. When the leader peptide of P. aeruginosa pilin was fused to the coding region for the M. voltae mature flagellin, cleavage of the leader peptide from the fusion protein appeared to occur, as determined by the shift in mobility in SDS-PAGE of this expression product as compared to that of the native protein. Interestingly, no expression product could be detected in mutants which lack the P. aeruginosa prepilin peptidase, presumably because in the absence of the peptidase activity, the protein is not stable and is quickly degraded in the cell. However, a second fusion in which the +5 position of the flagellin portion was changed to glutamic acid was detected readily in a PilD mutant. Comparison of the migration patterns of the full-length methanogen preflagellin (mature flagellin plus 12-amino-acid leader peptide) with the +5 glutamic acid fusion in the wild type and PilD mutant indicated that the intact preflagellin migrated slower than the fusion in the PilD mutant, which migrated slower than the fusion in the wild type. This indicated that the fusion product was being processed by the wild-type cells and that the enzyme responsible for this processing was the prepilin peptidase. Whether the prepilin peptidase was also methylating the N-terminal phenylalanine after cleavage of the leader peptide as it does in the pilin system is not known. These results indicate that the nature of the mature flagellin or pilin sequence downstream of the cleavage site is unimportant in discrimination by the leader peptidase. This supports the conclusions of Strom and Lory (41) and MacDonald et al. (32), who looked at the effect of different amino acid substitutions in P. aeruginosa pilin on leader peptide cleavage and pilus assembly.

Since the leader peptide of the fusion protein was cleaved, we reasoned that the product would have access to the pilus assembly apparatus and so examined the surface of cells for assembly of filaments similar in diameter to archaeal flagella. This was performed in a pilA strain (in which the pilA mutation also would reduce the competition of the flagellin for the prepilin peptidase) to aid in discrimination between archaeal flagella and the similarly sized native pili of P. aeruginosa. No archaeal filaments were detected in cells synthesizing either the FlaB2 fusion or the FlaB2 fusion with the additional +5 glutamic acid change. Strom and Lory (41) found that substitution of valine for glutamic acid at position +5 resulted in the synthesis of P. aeruginosa pilin that was processed by the leader peptidase but nevertheless was not assembled into a pilus structure. Since the +5 position in FlaB2 was also changed to glutamic acid from glycine, this is not the reason for the failure to assemble a structure on the cell surface. This observation suggests that flagellin assembly requires other specific accessory proteins from M. voltae. A number of such putative flagellum accessory genes have been identified in the flagellin multicistronic unit, and their products bear no significant similarity to other proteins previously described (2). Finally, it is also possible that further posttranslational modification of the flagellins is necessary before the subunits will assemble into the macromolecular structure. For example, glycosylation of flagellins appeared to be necessary for stable filament formation in M. deltae (4).

The experiments described in this report have resulted in the production of a source of archaeal preflagellin, which acts as a substrate for preflagellin peptidase. This enzyme may be specific for the archaeal flagellin system analogous to the prepilin peptidase of the type IV pilus system. One of the defining differences between the bacterial and the archaeal flagella systems is the presence of signal peptides on archaeal flagellins, a situation not described for bacterial flagellins. The possible exception is FlaA of Spirochaeta aurantia (6), but this protein represents the surface protein of the layered flagella and not the filament core proteins, and FlaA shows no homology to any other flagellins studied. Such a fundamental difference between the flagella of the two prokaryotic domains likely manifests itself in a mode of assembly of archaeal flagella clearly distinct from that of bacterial flagella, in which the new flagellin monomers travel down the hollow filament and incorporate at the distal tip (19). Continued study of this unique motility structure in this laboratory is focusing on the role of the archaeal specific accessory proteins in the structure and assembly of the archaeal flagellum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported an operating grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to K.F.J. D.P.B. was the recipient of an Ontario Graduate Scholarship. The MiniCycler used for PCR was purchased with a grant from the Advisory Research Committee of Queen’s University.

We thank Susan Koval for electron microscopy and John S. Mattick for helpful suggestions and the gift of plasmids and strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayley D P, Florian V, Klein A, Jarrell K F. Flagellin genes of Methanococcus vannielii: amplification by the polymerase chain reaction, demonstration of signal peptides and identification of the major components of the flagellar filament. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;258:639–645. doi: 10.1007/s004380050777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayley D P, Jarrell K F. Further evidence to suggest that archaeal flagella are related to bacterial type IV pili. J Mol Evol. 1998;46:370–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayley D P, Kalmokoff M L, Farinha M A, Jarrell K F. Localization of flagellin genes on the physical map of Methanococcus voltae. Curr Microbiol. 1995;30:93–96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayley D P, Kalmokoff M L, Jarrell K F. Effect of bacitracin on flagellar assembly and presumed glycosylation of the flagellins of Methanococcus deltae. Arch Microbiol. 1993;160:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beard M K M, Mattick J S, Moore L J, Mott M R, Marrs C F, Egerton J R. Morphogenetic expression of Moraxella bovis fimbriae (pili) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2601–2607. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2601-2607.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahamsha B, Greenberg E P. Cloning and sequence analysis of flaA, a gene encoding a Spirochaeta aurantia flagellar filament surface antigen. J Bacteriol. 1989;170:4023–4032. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1692-1697.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brimer C D, Montie T C. Cloning and comparison of fliC genes and identification of glycosylation in the flagellin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa a-type strains. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3209–3217. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3209-3217.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J-F, Adams M D, Reich CI, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Weidman J F, Furhmann J L, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Kelley J M, Peterson J D, Sadow P W, Hanna M C, Cotton M D, Roberts K M, Hurst M A, Kaine B P, Borodovsky M, Klenk H-P, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castric P. pilO, a gene required for glycosylation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1244 pilin. Microbiology. 1995;141:1247–1254. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-5-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doig P, Kinsella N, Guerry P, Trust T J. Characterization of a post-translational modification of Campylobacter flagellin: identification of a sero-specific glycosylation moiety. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:379–387. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.370890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupuy B, Taha M-K, Pugsley A P, Marschal C. Neisseria gonorrhoeae prepilin export studied in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7589–7598. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.23.7589-7598.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faguy D M, Bayley D P, Kostyukova A S, Thomas N A, Jarrell K F. Isolation and characterization of flagella and flagellin proteins from the thermoacidophilic archaea Thermoplasma volcanium and Sulfolobus shibatae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:902–905. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.902-905.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faguy D M, Jarrell K F, Kuzio J, Kalmokoff M L. Molecular analysis of archaeal flagellins: similarity to the type IV pilin-transport superfamily widespread in bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:67–71. doi: 10.1139/m94-011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glazer A N, DeLange R J, Martinez R J. Identification of epsilon-N-methyllysine in Spirillum serpens flagella and of epsilon-N-dimethyllysine in Salmonella typhimurium flagella. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;188:164–165. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(69)90059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoshino T, Kageyama M. Purification and properties of a binding protein for branched-chain amino acids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1980;141:1055–1063. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.3.1055-1063.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoyne P A, Haas R, Meyer T F, Davies J K, Elleman T C. Production of Neisseria gonorrhoeae pili (fimbriae) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7321–7327. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7321-7327.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarrell K, Bayley D P, Florian V, Klein A. Isolation and characterization of insertional mutants in flagellin genes in the archaeon Methanococcus voltae. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:657–666. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5371058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarrell K F, Bayley D P, Kostyukova A S. The archaeal flagellum: a unique motility structure. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5057–5064. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5057-5064.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones C J, Aizawa S-I. The bacterial flagellum and flagellar motor: structure, assembly and function. Adv Microbiol Physiol. 1991;32:109–172. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joys T M. The flagellar filament protein. Can J Microbiol. 1988;34:452–458. doi: 10.1139/m88-078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalmokoff M L, Jarrell K F. Cloning and sequencing of a multigene family encoding the flagellins of Methanococcus voltae. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7113–7125. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7113-7125.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalmokoff M L, Jarrell K F, Koval S F. Isolation of flagella from the archaebacterium Methanococcus voltae by phase separation with Triton X-114. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1752–1758. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1752-1758.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalmokoff M L, Karnauchow T M, Jarrell K F. Conserved N-terminal sequences in the flagellins of archaebacteria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;167:154–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91744-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawarabayasi Y, Sawada M, Horikawa H, Haikawa Y, Hino Y, Yamamoto S, Sekine M, Baba S, Kosugi H, Hosoyama A, Nagai Y, Sakai M, Ogura K, Otsuka R, Nakazawa H, Takamiya M, Ohfuku Y, Funahashi T, Tanaka T, Kudoh Y, Yamazaki J, Kushida N, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Yoshizawa T, Nakamura Y, Robb F T, Horikoshi K, Masuchi Y, Shizuya H, Kikuchi H. Complete sequence and gene organization of the genome of a hyperthermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. DNA Res. 1998;5:147–155. doi: 10.1093/dnares/5.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly-Wintenberg K, Anderson T, Montie T C. Phosphorylated tyrosine in the flagellum filament protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5135–5139. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5135-5139.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim R, Sandler S J, Goldman S, Yokota H, Clark A J, Kim S-H. Overexpression of archaeal proteins in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Lett. 1998;20:207–210. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klenk H-P, Clayton R A, Tomb J-F, White O, Nelson K E, Ketchum K A, Dodson R J, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Richardson D L, Kerlavage A R, Graham D E, Kyrpides N C, Fleischmann R D, Quackenbush J, Lee N H, Sutton G G, Gill S, Kirkness E F, Dougherty B A, McKenney K, Adams M D, Loftus B, Peterson S, Reich C I, McNeil L K, Badger J H, Glodek A, Zhou L, Overbeek R, Gocayne J D, Weidman J F, McDonald L, Utterback T, Cotton M D, Spriggs T, Artiach P, Kaine B P, Sykes S M, Sadow P W, D’Andrea K P, Bowman C, Fujii C, Garland S A, Mason T M, Olsen G J, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon, Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature (London) 1997;390:364–370. doi: 10.1038/37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koga T, Ishimoto K, Lory S. Genetic and functional characterization of the gene cluster specifying expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1371–1377. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1371-1377.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kostyukova A S, Jarrell K F. Abstracts of the Conference on Biology of Molecular Chaperones: biological roles and action of molecular chaperones. Aghia Pelaghia, Crete, Greece. 1995. Identification of chaperones from different methanogenic archaea, abstr. 53. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structure proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lechner J, Wieland F. Structure and biosynthesis of prokaryotic glycoproteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:173–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.001133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacDonald D L, Pasloske B L, Paranchuk W. Mutations in the fifth position glutamate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pilin affect the transmethylation of the N-terminal phenylalanine. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:500–505. doi: 10.1139/m93-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattick J S, Bills M M, Anderson B J, Dalrymple B, Mott M R, Egerton J R. Morphogenetic expression of Bacteroides nodosus fimbriae in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:33–41. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.33-41.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moens S, Michiels K, Vanderleyden J. Glycosylation of the flagellin of the polar flagellum of Azospirillum brasilense, a Gram-negative nitrogen-fixing bacterium. Microbiology. 1995;141:2651–2657. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsen R, DeBrusscher G, McCombie W R. Development of broad-host range vectors and gene banks: self-cloning of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:60–69. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.1.60-69.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Fritsch F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schweizer H P. Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19. Gene. 1991;97:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith D R, Doucette-Stamm L A, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Pothier B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Safer H, Patwell D, Prabhakar S, McDougall S, Shimer G, Goyal A, Pietrokovski S, Church G M, Daniels C J, Mao J-I, Rice P, Nolling J, Reeve J N. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum delta H: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Southam G, Kalmokoff M L, Jarrell K F, Koval S F, Beveridge T J. Isolation, characterization and cellular insertion of the flagella from two strains of the archaebacterium Methanospirillum hungatei. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3221–3228. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3221-3228.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sprott G D, Koval S F, Schnaitman C A. Cell fractionation. In: Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 72–103. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strom M S, Lory S. Amino acid substitutions in pilin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Effect on leader peptide cleavage, amino terminal methylation and pilus assembly. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1656–1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strom M S, Lory S. Kinetics and sequence specificity of processing of prepilin by PilD, the type IV leader peptidase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7345–7351. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7345-7351.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strom M S, Lory S. Structure-function and biogenesis of the type IV pili. Annu Rev Micriobiol. 1993;47:565–596. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strom M S, Nunn D N, Lory S. Posttranslational processing of type IV prepilin and homologs by PilD of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:527–540. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas, N. A., J. D. Correia, and K. F. Jarrell. 1999. Unpublished observations.

- 48.Towbin M, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watson A A, Alm R A, Mattick J S. Construction of improved vectors for protein production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1996;172:163–164. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wieland F, Paul G, Sumper M. Halobacterial flagellins are sulfated glycoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:15180–15185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]