Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) causes legal blindness in older adults worldwide. Soft drusen are the most extensively documented intraocular risk factor for progression to advanced AMD. A long-standing paradox in AMD pathophysiology has been the vulnerability of Asian populations to polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) in the presence of relatively few drusen. Age-related scattered hypofluorescent spots on late phase indocyanine green angiography (ASHS-LIA) was recently proposed as precursors of PCV. Herein, we offer a resolution to the paradox by reviewing evidence that ASHS-LIA indicates the diffuse form of lipoprotein-related lipids accumulating in Bruch’s membrane (BrM) throughout adulthood. Deposition of these lipids leads to soft drusen and basal linear deposit (BLinD), a thin layer of soft drusen material in AMD; Pre-BLinD is the precursor. This evidence includes: 1. Both ASHS-LIA and pre-BLinD/BLinD accumulate in older adults and start under the macula; 2. ASHS-LIA shares hypofluorescence with soft drusen, known to be physically continuous with pre-BLinD/BLinD. 3. Model system studies illuminated a mechanism for indocyanine green uptake by retinal pigment epithelium. 4. Neither ASHS-LIA nor pre-BLinD/ BLinD are visible by multimodal imaging anchored on current optical coherence tomography, as confirmed with direct clinicopathologic correlation. To contextualize ASHS-LIA, we also summarize angiographic characteristics of different drusen subtypes in AMD. As possible precursors for PCV, lipid accumulation in forms beyond soft drusen may contribute to the pathogenesis of this prevalent disease in Asia. ASHS-LIA also might help identify patients at risk for progression, of value to clinical trials for therapies targeting early or intermediate AMD.

Subject terms: Macular degeneration, Retinal diseases

Abstract

年龄相关性黄斑变性 (AMD) 是全球老年人致盲的主要原因之一。软性玻璃膜疣是其进展为晚期AMD最广为人知的眼内风险因素。而在AMD的病理生理学中有一个长期存在的悖论, 即在玻璃膜疣相对较少的情况下, 亚洲人群患息肉状脉络膜血管病变 (PCV) 的风险更高。我们最近的研究提出, 吲哚青绿血管造影晚期显现的年龄相关性散在低荧光点(ASHS-LIA)是PCV形成的先兆。在此, 我们回顾ASHS-LIA代表脂蛋白相关性脂质随着年龄增长在Bruch膜(BrM)中弥散性聚集的研究证据, 从而解释这一悖论。这些脂质沉积导致了软玻璃膜疣和基底线性沉积(BLinD)的形成,其中BLinD是软性玻璃膜疣样物质的弥散性沉积形式 (Pre-BLinD是其前体)。这些研究证据包括: 1、ASHS-LIA和pre-BLinD/ BLinD均在老年人眼内沉积, 并均始于黄斑下;2.ASHS-LIA与软性玻璃膜疣均表现为低荧光, 在结构上与pre-BLinD/BLinD有连续性。3.模型系统研究阐明了视网膜色素上皮摄取吲哚青绿的分子机制。4. ASHS-LIA和pre-BLinD/BLinD在包括光学相干断层扫描的多模式成像中均不可见, 而我们的直接临床病理相关性研究也证实了这一点。此外, 我们还总结了AMD中不同玻璃膜疣亚型的血管造影特征。作为PCV的可能先兆, 软玻璃膜疣以外形式的脂质沉积可能与这种亚洲人群多发疾病的发病机制有关。ASHS-LIA还可能有助于识别有进展风险的AMD患者, 对靶向治疗早期或中期AMD的临床试验有价值。

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the fourth largest cause of vision loss globally [1], due to macular neovascularization (MNV) and atrophy in its advanced forms (geographic atrophy, GA, for the underlying disease, and macular atrophy, MA, secondary to neovascularization). Aging is the main risk factor for AMD progression. Although many details remain to be learned, our views of AMD have been refined substantially through recent clinical imaging and anatomic/molecular pathology studies [2–4].

Numerous studies have focused on precursor lesions in the progression to different subtypes of advanced AMD. Drusen are the best documented intraocular risk factor for progression to advanced AMD [5, 6]. Eyes with both large drusen and pigmentary abnormalities are more likely to develop typical AMD, whereas pigmentary abnormalities without large drusen were associated with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV), a form of type 1 neovascularization AMD that is highly prevalent in Asian populations [7, 8]. Where PCV fits in the AMD spectrum has been controversial, because soft drusen are uncommon in eyes with PCV, unlike eyes with conventional AMD. Recently, an imaging feature, age-related scattered hypofluorescent spots on late phase indocyanine green angiography (ASHS-LIA) was proposed as a possible precursor of PCV [9], which if proven, represents a major step forward in understanding the pathogenesis of PCV. Interestingly, based on our findings and previous pathologic insights on aging and AMD, we infer that the ASHS-LIA represents lipid accumulation underneath the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), in the form of basal linear deposit (BLinD), its precursor, pre-BLinD, and before that, age-related Bruch’s membrane (BrM) lipidization.

This review will focus on ASHS-LIA and its clinical application and pathologic significance. We begin with a brief overview of retinal regions and layers, followed by early descriptions of drusen and aging eyes visualized with indocyanine green angiography (ICGA). We will summarize a model of drusen formation. The principles of ICGA labeling will be introduced. Characteristics and relevant factors of ASHS-LIA, how is ASHS-LIA formed, what ASHS-LIA represents, why this is important to know, and an outlook building on this new knowledge and synthesis will be presented.

AMD by the regions and layers

The retina is a multilayered component of the central nervous system that lines the internal surface of the ocular fundus. It converts the energy of environmental light to electric energy for transmission to the brain via the optic nerve. Human retina contains >100 million photoreceptors, including rods that respond to dim light and cones that response to colors in bright light (20:1 ratio of rods to cones). The fovea is a specialization in many primate species including humans. In the area between the vascular arcades, photoreceptors are roughly radially distributed around the center of the fovea, as captured by the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study grading grid (Fig. 1). In the center of the fovea (~1 mm diameter) is the all-cone foveola. This in turn centers a ~3 mm diameter macula lutea has abundant xanthophyll carotenoid pigments that provide a characteristic yellow color. The inner retinal layers are absent at the fovea and thick in the 6 mm-diameter central area (or macular region) surrounding it. The central area (containing macula lutea within it) and the optic nerve together comprise the posterior pole of the eye.

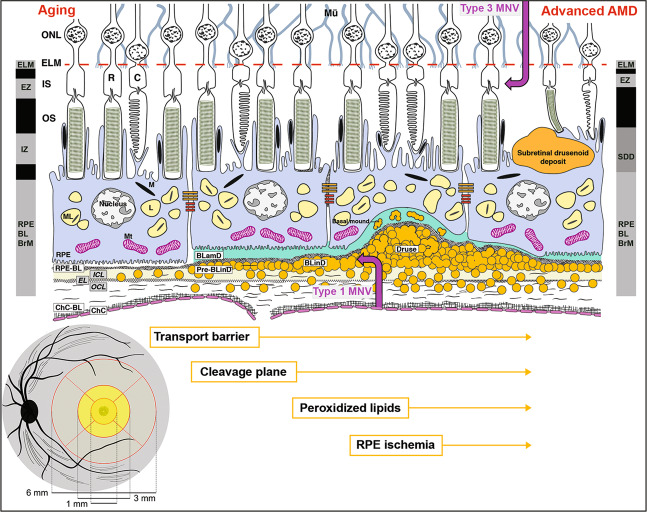

Fig. 1. Retinal layers, regions, and the role of lipid in AMD progression.

Lower left: The schematic shows the posterior pole of the ocular fundus. Black oval is the optic nerve, with arteries and veins of the retinal circulation shown. The Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study grading grid and its dimensions are shown. The grid consists of the central subfield, inner ring, and outer ring (1, 3, and 6 mm in diameter, respectively). The central subfield is mostly all cones with a few rods around its outer rim. The black stippling represents a central bouquet of very thin cone photoreceptors and supporting Müller glia. The 3 mm-diameter inner ring has prominent xanthophyll carotenoid pigments, shown as yellow, in the neurosensory retina, representing the macula lutea. The 6 mm diameter area is called central area or macular region. Upper: the trilaminar BrM consists of inner collagenous (ICL), elastic (EL), and outer collagenous (OCL) layers. With aging, lipoprotein particles (yellow circles) accumulate in the BrM, forming a transport barrier between the ChC and the outer retina. Pre-BLinD, a thin lipid layer between RPE-BL and the ICL of the BrM forms a cleavage plane. BLinD, continuous with pre-BLinD, contains ultrastructural evidence for lipid fusion and pooling and peroxidized lipids capable of promoting cytotoxic and proinflammatory response in vivo. Into this milieu, Type 1 neovascularization invades (mauve up-arrow). Soft drusen, a lump of the same extracellular material as in BLinD, could contribute to ischemia of the overlying RPE, which may migrate intraretinally (seen as hyperreflective foci). BLamD is stereotypically thickened basement membrane proteins (green, in middle and right) between the RPE plasma membrane and native RPE-BL, either replacing or incorporating infoldings of basal RPE. Basal mounds are soft drusen material trapped within BLamD. Between the RPE and photoreceptors are SDDs (first called reticular pseudodrusen), extracellular material that is directly disruptive to photoreceptors. Eyes with SDDs are at risk for type 3 MNV (mauve down-arrow). The black and gray columns at the right and left represent reflective bands of current optical coherence tomography. AMD age-related macular degeneration, BLinD basal linear deposit, BLamD basal laminar deposit, ChC choriocapillaris, ChC-BL ChC basal lamina, OS outer segments of photoreceptors, M melanosome, ML melanolipofuscin, Mt mitochondria.

The cells and tissues most prominently affected by AMD pathology are those of the outer retinal neurovascular unit, i.e., photoreceptors and their supporting RPE, Müller cells (in neurosensory retina), choriocapillaris (ChC) endothelium (in the choroidal vasculature) (Fig. 1), and deep capillary plexus in the retinal vasculature (not shown). As increasingly visible via optical coherence tomography (OCT), AMD features nine biologically distinct layers in <100 µm of vertical space between the external limiting membrane and the ChC. Between RPE and ChC is BrM, comprised of inner collagenous, elastic, and outer collagenous layers (ICL, EL, OCL). BrM functions as a vessel wall in parallel to vascular lumens of the ChC. On the inner aspect (closer to the front of the eye) is the basal lamina (BL) of the RPE and on the outer aspect is the BL of the ChC endothelium. Between the RPE-BL and the ICL is the sub-RPE-BL space, a potential space that fills with lipid in aging. In AMD, this space fills with drusen and neovascularization of choroidal origin, including PCV. Historically BrM was considered five layers (including the two BL). However, AMD pathology is most readily understood with a three-layer construct [10, 11].

ICGA of drusen and aging—initial studies

Drusen are extracellular deposits lying between RPE-BL and the ICL of BrM (Fig. 1). In 1997 Arnold et al. summarized how drusen appear in ICGA [12]. They classified drusen into four groups:1. hard drusen, 2. drusen derived from clusters of other drusen, 3. membranous (soft) drusen, and 4. regressing drusen. Soft drusen with membranous contents according to their own ultrastructural studies were hypofluorescent throughout ICGA. In contrast hard drusen were hyperfluorescent. Regressing drusen may show hyperfluorescence at early phases of ICGA; associated calcium deposits within drusen and pigmentation within the retina were hypofluorescent.

In 1999 Shiraki et al. [13] described hypofluorescent spots in normal aged fundus using video fundus camera angiograms, and in eight eyes of seven patients, using confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy angiograms after 30 min. These authors used the term age-related scattered hypofluorescent spots on late phase indocyanine green angiograms, later shortened to ASHS-LIA [14]. The sample of 115 eyes included those with a normal fundus or dry AMD, suggesting that ASHS-LIA was age-related but not correlated with dry AMD. ASHS-LIA was mainly distributed in the posterior pole, especially in the macular region. In 1998 Yoneya et al. [15] determined that in circulation, ICG binds to lipoprotein fractions of plasma, especially the phospholipid components of these multimolecular complexes. In 2001 Ito et al. [16] also using video technology found hypofluorescent patches in 20 of 23 eyes over 45 years and 2 of 11 eyes under age 45 years and offered possible explanations. These included irregular dye filling into the ChC, loss of arterioles resulting in delayed dye-filling, and hyperpigmentation of RPE blocking signal.

The requirement for video impeded follow up on these initial concepts. This would await development and commercialization of confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy with dual excitation and detection systems for fluorescein and ICG [17], and routine application of this technology in large clinic populations, as we show below.

Synopsis of drusen-driven AMD

Figure 1 shows the role of lipid in AMD progression, based on the three-layer vascular BrM and the well-known role of lipoproteins in atherosclerotic vascular disease. Early in adulthood, lipids start accumulating in BrM, forming a transport barrier between the ChC and the outer retina due to the hydrophobicity of lipids, especially esterified cholesterol, the dominant moiety. Then pre-BLinD (initially called “lipid wall”) is gradually formed, forming a cleavage plane between the RPE-BL and the ICL of BrM. It is thought that subsequent degradation of apolipoproteins associated with these lipids causes particle fusion and the formation of BLinD. BLinD is a thin layer of soft drusen material that contains peroxidized lipids capable of cytotoxicity and promoting a proinflammatory response in vivo, thus playing an essential role in AMD progression [18]. Soft drusen, a lump of the same extracellular material, contributes to ischemia of the overlying RPE by increasing the distance to the ChC, also impacting angiogenic regulators and promoting angiogenesis. Another new layer is BLamD, a thickening of native RPE-BL, which is also prominent in the macula and represents an anatomical risk factor for progression when abundant [19]. Lipids can be seen crossing BLamD [20].

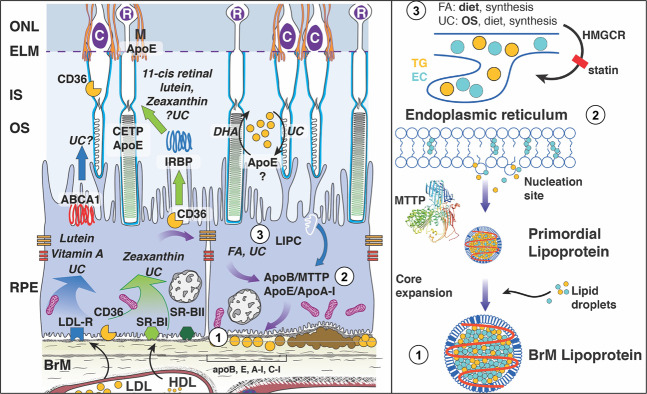

Ultrastructural and compositional studies together support lipoprotein particles of intraocular origin as a major mechanism by which these lipids arrive in BrM (Fig. 2). The principal component of soft drusen material was termed membranous debris by Sarks et al. [21], because it resembled coiled membranes by electron microscopy, signifying lipid-rich material. Lipid histochemistry of AMD eyes showed unesterified cholesterol in BrM, drusen and local cellular membranes, as expected, and also abundant neutral lipids especially esterified cholesterol. The latter, localizing only to BrM in early adulthood and to drusen later in life, increases markedly with age in normal eyes. The principal way esterified cholesterol is released by cells is in lipoprotein particles like hepatic very low-density lipoprotein, i.e., multimolecular complexes specialized to transport multiple lipid classes through aqueous media like plasma. Specialized ultrastructural techniques revealed that membranous debris was solid, space-filling particles in aged BrM that floated like lipoproteins and had surface-and-core morphology. Further, RPE expresses numerous genes known from lipoprotein biology, and thus has capacity to secrete these large lipoproteins. Local gene expression also provides a basis for why sequence variants in lipid/lipoprotein genes (e.g., APOE, LIPC) [22–24] modulate AMD risk. Cell culture studies showed that RPE can make drusen constituents including lipid by taking up only cell culture medium [25, 26]. Thus, we hypothesize that relatively healthy RPE constitutively releases material to plasma. This material builds up due to failure of transport across the ChC-BrM barrier, in an atherosclerotic-like progression, which begins in aging and exacerbates in AMD.

Fig. 2. Molecular circuitry for production of Bruch’s membrane lipoproteins.

Left Circles 1–3 are detailed in the right panel. Circle 1 shows accumulation of Bruch’s membrane lipoproteins, resulting in pro-inflammatory peroxidized lipids. Circle 2 shows generation of a primordial lipoprotein at the endoplasmic reticulum, with MTTP-mediated transfer of lipid as in liver and intestines. Circle 3 shows that in rough endoplasmic reticulum at apical RPE, lipid droplets destined for lipoproteins are formed from components originating in diet » outer segments » endogenous synthesis. Lutein, zeaxanthin, vitamin A, and some unesterified cholesterol (UC) enter RPE via receptor-mediated uptake of plasma lipoproteins. These are transferred to photoreceptors by mechanisms that may involve interphotoreceptor retinol-binding protein (IRBP, center), a hypothetical apolipoprotein (apo) E-based small HDL particle (right), or diffusion (not shown). Because lipids in Bruch membrane lipoproteins are rich in the fatty acid linoleate (and not docosahexaenoate), soft drusen are proposed as consequent to constitutive dietary delivery of lipophilic essentials to macular cells, and the RPE- mediated recycling of these unneeded lipids and those from outer segments to plasms via large lipoprotein particles. Lipoproteins accumulate between RPE-basal lamina and inner collagenous layer of Bruch’s membrane. ABCA1 ATP-binding-cassette A1, apoE apoB, apoA-I, apolipoproteins E, B, A-I; BrM Bruch’s membrane, C cones, CD36 cluster of differentiation 36, CETP cholesteryl ester transfer protein, DHA docosahexaenoate, EC esterified cholesterol, ELM external limiting membrane, FA fatty acid, HMGCR HMG co-A reductase, target of statins, IS inner segment, LDLR LDL-receptor, M Müller cells, MTTP microsomal triglyceride transfer protein, ONL outer nuclear layer, OS outer segment, R rods, SR-BI scavenger receptor BI, SR-BII scavenger receptor B2, TG triglyceride, UC unesterified cholesterol.

Remarkably, drusen follow the topography of cone photoreceptors and their support system. The abundance and progression risk conferred by soft drusen material is highly concentrated under the fovea and within the central 3 mm diameter [27–29]. It is thus postulated that the high concentration of soft drusen and AMD progression risk is a late-life consequence of HDL-mediated delivery of specialized xanthophyll carotenoid pigments (lutein and zeaxanthin) to the macula lutea (Fig. 1) throughout life. Therapeutic strategies based on this “oil spill” biology include lipid scavengers, modulators of lipoprotein production (e.g., statins), and a balanced diet with micronutrients or AREDS2 formulation to enrich HDL [30–33].

In sum, a means of visualizing soft drusen material in vivo would be highly valuable for patient management, treatment planning, enrollment criteria for clinical trials, and understanding AMD pathophysiology at a new level, to inspire new treatments. Does ASHS-LIA meet this challenge?

Principles of ICG angiography and visualization of outer retina

ICG is a well-tolerated, tricarbocyanine dye with a molecular weight of 775 daltons that absorbs light at 790–805 nm and has a peak emission at 835 nm. ICG dye has been used in medicine since 1956, when it was approved by the Federal Drug Administration for imaging cardiac and hepatic circulations. Ophthalmology was introduced to dye-based angiography using sodium fluorescein in 1961 [34], then in 1972, ICG dye was first used for the eye [35]. Since ICG excites and emits at near-infrared wavelengths, imaging signal penetrates the RPE, blood, and serous fluids allowing observation of the choroidal circulation behind the RPE [36]. ICGA is mainly used in the diagnosis of chorioretinal conditions, especially choroidal neovascularization and PCV, which benefits from the longer wavelength compared to sodium fluorescein [37]. Previous study reveals that ICG binds intensely to HDL and moderately to LDL in circulation [15]. This property leads to lower vascular or tissue permeability than sodium fluorescein, because HDL and LDL have larger diameters than albumin (11, 22, and 8.5 nm, respectively).

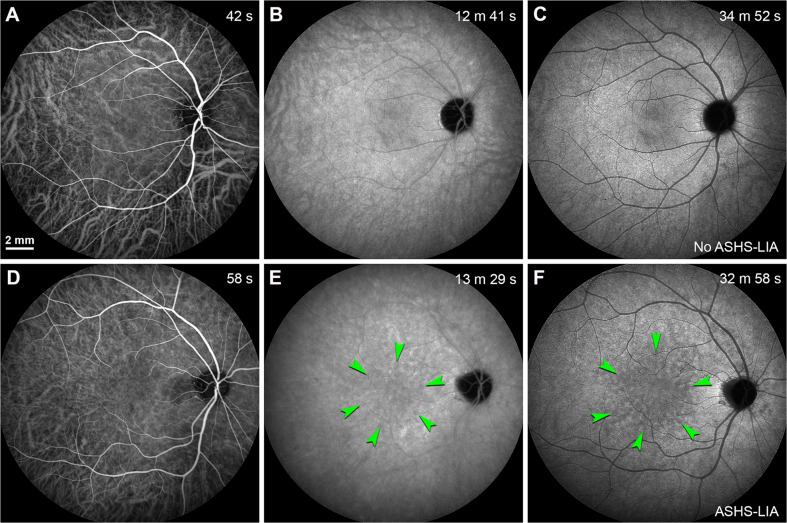

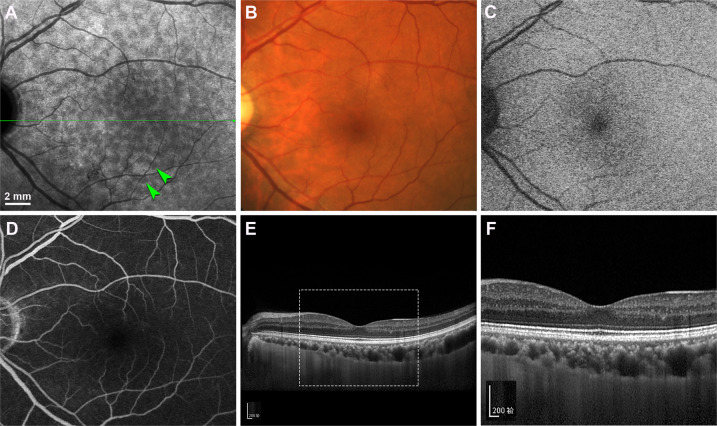

ICG dye localizes within retinal and choroidal vessels in the early-phase after injection (Fig. 3A). Further, it extravasates into the choroidal stroma and accumulates within the RPE over time (Fig. 3B). Homogeneous background fluorescence is observed in late phase ICGA under normal conditions (Fig. 3C). The phases visible in humans (Fig. 3) can also be seen in non-human primates and rats [38, 39], allowing mechanistic investigation of ICG dye uptake. In histologic sections of aged monkey eyes preserved at the middle- and late-stages of ICGA, the RPE-BrM complex, including drusen, was brightly fluorescent [38, 40]. It is not known whether the animals used in these studies had soft drusen, as not all aged monkeys have them [41, 42]. Thus, the idea that soft drusen material might exclude ICG could not be tested directly.

Fig. 3. Homogeneous background fluorescence in late phase ICGA and the formation of ASHS-LIA.

Scale bar in (A) applied to all panels. A–C Normal fundus fellow eye from a 38-year-old woman whose left eye was diagnosed with idiopathic choroidal neovascularization (not shown). D–F Normal fundi fellow eye from a 61-year-old man whose left eye was diagnosed with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (not shown). Time after ICG dye injection was indicated in the top right-hand corner. A ICG dye was located within retinal and choroidal vessels in the early-phase after injection; B ICG dye was extravasated into the choroidal stroma and accumulated within the RPE over time; C Homogeneous background fluorescence (no ASHS-LIA) was observed in late phase ICGA. D ICG dye was located within retinal and choroidal vessels in the early-phase after injection; E Scattered hypofluorescent spots (green arrowheads) were appreciable in the mid-phase after injection. F Hypofluorescent spots were obvious in late phase ICGA (ASHS-LIA) and distributed in the macular region (green arrowheads).

Cultured human RPE cells were found to take up ICG dye, involving an active transport mechanism that could be inhibited by ouabain administration [43]. These results suggest that normally functioning RPE cells are required for ICG imaging in vivo. Using adaptive optics enhanced ICG ophthalmoscopy, Tam et al. demonstrated that RPE cells in vivo took up ICG dye following systemic injection and contributed to the fluorescence signal observed in the late phase of ICGA [39].

In addition to normal functioning RPE, access of ICG dye from choroidal stroma to RPE through BrM is another prerequisite for signal in late phase ICGA. ICG dye is water-soluble and may bind preferentially to polar phospholipids over hydrophobic neutral lipids [15]. In this situation, deposits in the RPE- BrM complex, such as drusen, would play an important role in the fluorescence signal changes in ICGA. ICG dye could bind with phospholipid, but not with esterified cholesterol, unesterified cholesterol, or triacylglycerol [15], thus uptake by RPE and detection by cameras external to the eye is prevention. These considerations can explain how soft drusen could show hypofluorescence in late phase ICGA [12]. A principle of fluorescein angiography is that reduced signal (hypofluorescence) can be explained by ischemia (loss of blood flow), blockage of signal transmission by materials in the light path, or both [44]. Our considerations for AHSH-LIA indicate that reduced dye access from vasculature to target tissue (RPE) is another mechanism for hypofluorescence specific to ICGA. Understanding of distinct ICG patterns may facilitate better understanding of the disease processes and pathogenesis.

Characteristics of ASHS-LIA

The hypofluorescence of soft drusen throughout ICGA [12] is suggestive but does not prove that soft drusen exclude ICG dye. We reasoned that antecedents of soft drusen may also exclude ICG dye and thus present as hypofluorescence. We present evidence that ASHS-LIA is a strong candidate for an imaging correlate of these tissue-level effects.

In 2018, we reported multimodal imaging characteristics and associations of ASHS-LIA [14]. We used confocal laser scanning ophthalmoscopy, which provided a clear view and repeatable findings. Our sample was large, comprising 875 normal fellow eyes from 875 patients with various chorioretinal diseases seen in a major clinical center in China. Among those 875 patients ages 6–90 years (mean: 54.2 ± 16.4 years), ASHS-LIA was identified in 233 patients (26.6%) aged 33–87 years (mean: 65.8 ± 8.4 years). The youngest patient with ASHS-LIA in the cohort was a 33-year-old man who was diagnosed with PCV.

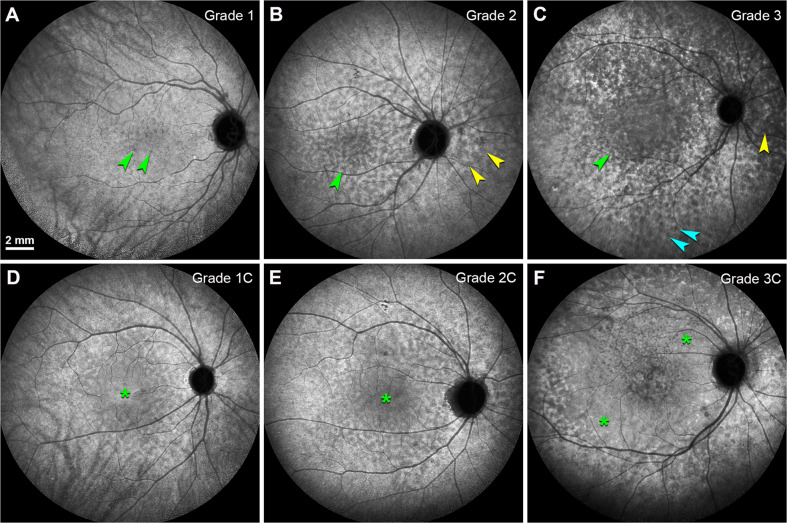

ASHS-LIA, mainly distributed in the macular region, was observed as early as about 15 min after ICG dye injection (Fig. 3E) and was obvious by 30 min post-injection (Fig. 3F). The diameter of the spots in ASHS-LIA ranged from 100 to 500 μm, with the majority between 200 and 300 μm. According to the region of involvement, we divided ASHS-LIA into three grades, as follows: grade 1, ASHS-LIA mainly in the macular region (Fig. 4A); grade 2, ASHS-LIA in the macular region and around the optic disc (Fig. 4B), and grade 3, ASHS-LIA throughout the whole posterior pole (Fig. 4C). In addition, the grade of ASHS-LIA increased with aging, and ASHS-LIA could be confluent at all grades (Fig. 4D–F). However, no corresponding abnormalities were observed on other imaging modality, including color fundus photography (CFP, Fig. 5B), blue fundus autofluorescence (FAF, Fig. 5C), FFA (Fig. 5D) and optical coherence tomography (OCT, Fig. 5E, F). The incidence of ASHS-LIA was highest in PCV patients, the second highest in patients with neovascular AMD, and then patients with dry AMD.

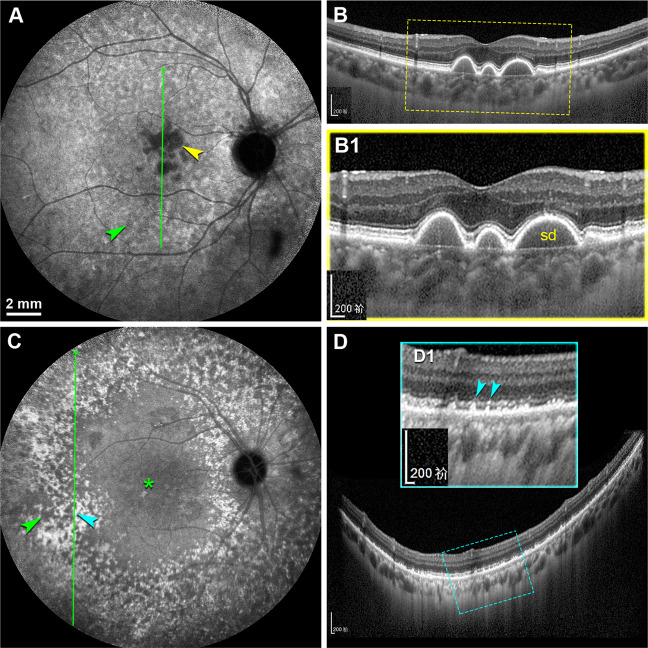

Fig. 4. The grades of ASHS-LIA based on the involved region.

Different grades of ASHS-LIA were shown in late phase ICGA (30 min after dye injection). Scale bar in (A) applied to all panels. A Grade 1: ASHS-LIA distributed in the macular region (green arrowheads); B Grade 2: ASHS-LIA distributed in the macular region (green arrowhead) and around the optic disc (yellow arrowheads); C ASHS-LIA distributed throughout the whole posterior pole (Teal arrowheads); D ASHS-LIA distributed in the macular region with partial confluence (green asterisk); E ASHS-LIA distributed in the macular region and around the optic disc, with partial confluence (green asterisk); F ASHS-LIA distributed throughout the whole posterior pole, with partial confluence (green asterisks).

Fig. 5. ASHS-LIA are invisible on other imaging modalities.

Normal fundi fellow eye from a 64-year-old man whose right eye was diagnosed with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (not shown). Scale bar in (A) applied to (A–D). A ASHS-LIA (green arrowheads) were distributed in the macular region in late phase ICGA. No corresponding changes were present in the color fundus photography (B), blue autofluorescence (C), and fluorescein fundus angiography (D). E Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) at green arrow in (A) showed that the retinal structure was generally normal, and the RPE band was intact and smooth, with no intraretinal, subretinal or sub-RPE visible deposition corresponding to ASHS-LIA. F Magnified SD-OCT image showed the white frame region in (E).

Of note, the hypofluorescent spots noted on late phase ICGA differed from the hypofluorescent lesions common in patients with inflammatory conditions involving the choroid such as multifocal choroiditis and acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE) [45, 46], not only in the distribution characteristics but also in the multimodal imaging features.

ASHS-LIA reveals fundus aging

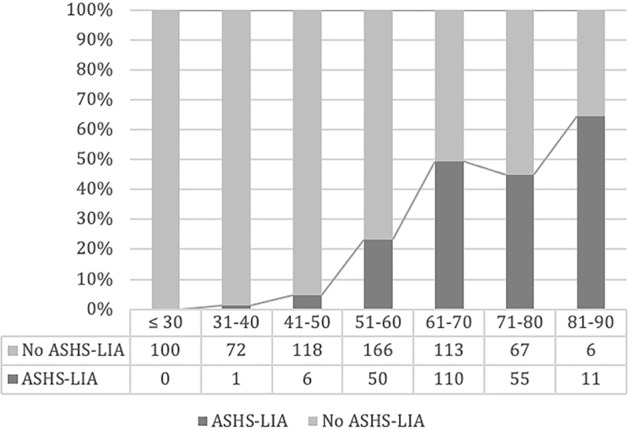

Our 2018 study in a large sample confirmed that ASHS-LIA was age-related [14]. The mean age of patients with ASHS-LIA was 65.8 compared to a mean age of 50 years old for patients without ASHS-LIA. In a multiple logistic regression analysis, age was most relevant independent factor for ASHS-LIA frequency. Figure 6 shows that a steady rise of ASHS-LIA frequency starting in early adulthood.

Fig. 6. The frequency of ASHS-LIA increases with age after age 30 years.

Patients were divided into seven subgroups by age in decades. The percentage of eyes with ASHS-LIA increased markedly with aging. No ASHS-LIA was observed in the age group of ≤30. The percentage of eyes with ASHS-LIA were 1.4%, 4.8%, 23.1%, 49.3%, 45.1% and 64.7% respectively in the age groups of 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–70, 71–80 and 81–90. Data are replotted from Chen et al. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2018 [14].

Since ASHS-LIA was age-related, hypofluorescent on ICGA and mainly located in the macular region, we examined the association between ASHS-LIA and drusen, the hallmark lesions of early AMD. Soft drusen were also age-related, hypofluorescent on ICGA, and mainly located in the macular region [5]. In this scenario, we inferred that ASHS-LIA might reveal soft drusen material. Thus, we explored this association in a cohort of 345 patients [47]. We found that the frequency of soft drusen increased with the grade of ASHS-LIA. Further, both soft drusen and ASHS-LIA presented as hypofluorescence in late phase ICGA, and soft drusen were located inside the region with ASHS-LIA (Fig. 7A, B). Hard drusen in contrast presented as hyperfluorescence in late phase ICGA, outside the region with ASHS-LIA (Fig. 7C, D). Therefore, we inferred that ASHS-LIA revealed fundus aging and might show soft drusen material in the sub-RPE- BL space.

Fig. 7. The distribution relationship of ASHS-LIA and soft & hard drusen.

A, B The right eye from a 78-year-old man with PCV in his left eye (not shown). A Late phase ICGA showed that soft drusen presented as dense hypofluorescence in the macular region (yellow arrowhead), and ASHS-LIA were present in its surround (green arrowhead). B SD-OCT at green arrow in (A) showed drusenoid pigment epithelium detachment corresponding to the soft drusen. B1 Magnified SD-OCT image showed the yellow frame region in (B). sd, soft drusen. C, D The right eye from a 66-year-old woman with PCV in her left eye (not shown). C Late phase ICGA showed ASHS-LIA (green arrowhead) throughout the posterior pole, with remarkable confluence (asterisk). Hard drusen presented as hyperfluorescent spots (teal arrowhead) and were located outside the ASHS-LIA. D SD-OCT at green arrow in (C) showed focal high reflective deposits underneath the RPE, corresponding to the hyperfluorescent spots in (C). D1 Magnified SD-OCT image (the teal frame region in D) showed the high reflective deposits elevated the RPE and the myoid zone (teal arrowheads).

Since the incidence of ASHS-LIA was highest in PCV patients [14], we wondered if ASHS-LIA was associated with the occurrence and clinical characteristics of PCV [14]. In 187 patients with PCV, we found that a large percentage of these patients (62.6%) showed ASHS-LIA [9]. Compared with PCV patients without ASHS-LIA, PCV patients with ASHS-LIA were significantly older, more frequently had bilateral lesions, and less frequently showed choroidal vascular hyperpermeability (CVH), another important imaging feature in patients with PCV [48] or central serous chorioretinopathy [49]. Previous studies revealed that CVH might be associated with the occurrence of PCV and the treatment response to intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF but with inconsistent outcomes [48, 50, 51]. Our study indicated that ASHS-LIA might be an important precursor lesion of PCV and might confer a risk of bilateral involvement. We speculated that ASHS-LIA might represent a pathway in PCV pathogenesis differ from CVH [9]. Our findings shed light on why drusen were not so common in PCV patients as in typical AMD patients, and why the onset age of PCV patients were younger than typical AMD patients.

What does ASHS-LIA represent?

Based on our own findings, knowledge from previous pathology studies, and results of the experimental studies above, we speculate that ASHS-LIA represents neutral lipid accumulation in all its forms, i.e., within BrM, pre-BLinD, and BLinD, thus representing the total burden of lipoprotein accumulation over adulthood that culminates in soft drusen in AMD. The main reasons are that: 1. Both ASHS-LIA and lipoproteins rich in esterified cholesterol accumulate in older adults; 2. Both ASHS-LIA and lipid deposition start under the macula; 3. ASHS-LIA shares hypofluorescence with soft drusen, known to be physically continuous with pre-BLinD/BLinD. 4. Neither ASHS-LIA nor pre-BLinD/ BLinD are visible by multimodal imaging anchored on current OCT.

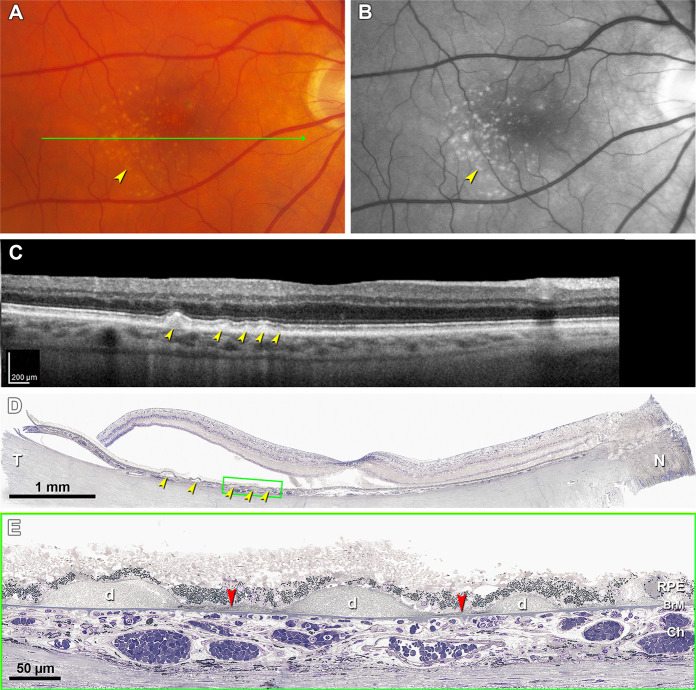

With sensitive histochemistry lipid may be detectable within BrM as early as the third decade of life [52–54], close to earliest age of ASHS-LIA visibility [14]. Lipid deposition in BrM is sevenfold higher in the macular region than in the periphery [55]. Pre-BLinD between the RPE-BL and the ICL of BrM forms in normal eyes >60 years of age [18, 54, 56]. BLinD was first described as membranous debris due to an appearance of coiled membranes by electron microscopy [10, 21, 57]. However, lipid-preserving ultrastructural techniques demonstrated BLinD as a thin, tightly packed layer (0.4–2 µm) of lipoprotein-derived debris containing neutral lipids [20, 58]. Since the axial resolution of current SD-OCT is about 5 µm, BLinD cannot be detected clinically. Our recent study [59] confirmed with direct clinicopathologic correlation that soft drusen could be detected by OCT-based multimodal imaging, but BLinD could not (Fig. 8A–C). Accordingly, ASHS-LIA is invisible on OCT-based multimodal imaging [14]. BLinD and soft drusen are diffuse and focal deposits, respectively, of the same material, located in precisely the same plane (Fig. 8D, E). Therefore, BLinD should share hypofluorescence with soft drusen in ICGA (Fig. 7A).

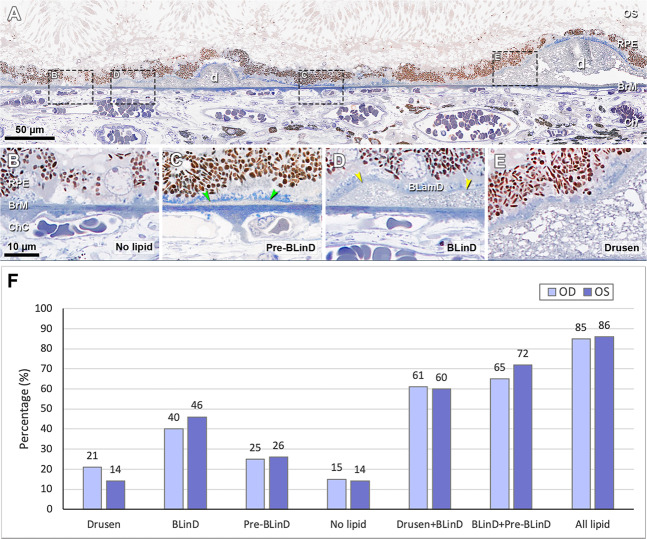

Fig. 8. BLinD and soft drusen are diffuse and focal deposits of the same lipoprotein-derived debris located in the same plane [59].

A–C Soft drusen are visible in OCT-based multimodal imaging (yellow arrowheads), basal linear deposit is not. A Color fundus photograph shows yellowish drusen in the macular region especially inferior temporal to the fovea. B Red-free image shows drusen clearly. C SD-OCT B-scan at green arrow in (A) shows several RPE elevations with a medium and homogeneous internal hyperreflectivity representing soft drusen. D Corresponding histologic image shows soft drusen (yellow arrowheads) that correspond well with the B-scan. Green frame shows a region magnified in (E). Retina is artifactually detached at the inner segment myoids (bacillary layer detachment). E Three soft drusen with finely granular, lightly osmophilic contents (d) are continuous with BLinD (red arrowheads) containing the same material, both underneath the RPE. Sixty-nine-year-old white old man with early age-related macular degeneration.

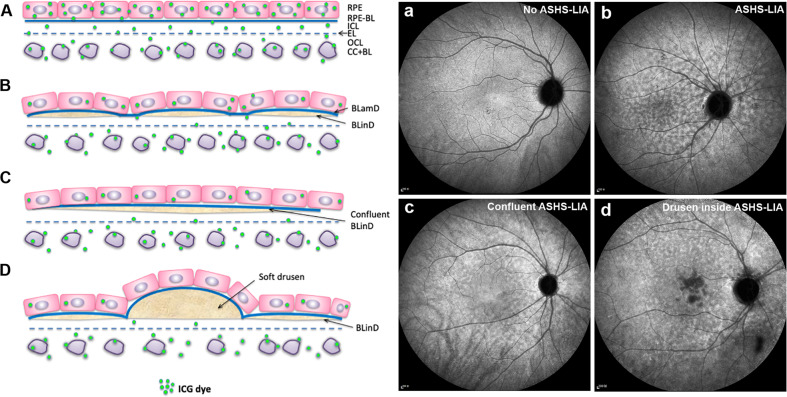

A model for the evolution of ASHS-LIA is presented in Fig. 9. After systemic injection, ICG dye is extravasated into the choroidal stroma, penetrating BrM, and accumulating within RPE over time [38, 40]. ICG dye is water-soluble and binds preferentially to phospholipid over hydrophobic neutral lipid such as esterified cholesterol [15]. In healthy young adults, ICG dye passes through BrM and is taken up by the RPE (Fig. 9A) resulting in a homogeneous background fluorescence in late phase ICGA (Fig. 9a). With aging, lipids in BrM impede ICG dye through BrM to reach the RPE (Fig. 9B) and present as hypofluorescent spots in late phase ICGA (Fig. 9b). As lipids become confluent as pre-BLinD and BLinD (Fig. 9C), confluent hypofluorescence is observed in late phase ICGA (Fig. 9c). Soft drusen are thicker deposits of the same material as BLinD (Fig. 9D), blocking more ICG passage to RPE, and presenting as more hypofluorescent than preceding stages (Fig. 9d).

Fig. 9. Proposal of correlation between ASHS-LIA and BLinD.

A Normal structure of the RPE, BrM, and choroidal capillaries (CC). Five layers of connective tissue are visible: basal lamina of the RPE (RPE-BL); inner collagenous layer (ICL); elastic layer (EL); outer collagenous layer (OCL); and basal lamina of the choriocapillaris endothelium (CC-BL). Under normal conditions, ICG dye could extravasate into the choroidal stroma, pass through BrM and eventually be taken up by the RPE. Therefore, homogeneous background fluorescence is observed in late phase ICGA (a). B With aging, the BLinD (dark yellow) formed between the ICL of BrM and the RPE basal lamina, containing mainly neutral lipids, could reduce ICG dye through BrM into the RPE. Hence, hypofluorescence is observed (b). Blue material represents the BLamD. C BLinD could be confluent and further reduced ICG dye through BrM into the RPE. Therefore, confluent hypofluorescence is observed (c). D Both soft drusen and the BLinD is located in precisely the same sub-RPE space and contain mainly neutral lipids. Soft drusen could impede ICG dye through BrM into the RPE to a higher degree than BLinD because of thicker deposits. Hence, soft drusen present as dense hypofluorescence in late phase ICGA.

Differential staining of drusen by angiographic dye was suggested by Pauliekhoff et al. [60]. Hard drusen were located outside the ASHS-LIA and presented as hyperfluorescence in late phase ICGA. Hard drusen also contain lipoproteins but at a much lower concentration than soft drusen [61]. Thus, hard drusen may manifest as hyperfluorescence in late phase ICGA due to either higher proportion of phospholipids binding more ICG dye, more ICG reaching the RPE due to lower neutral lipid content, or both. These two effects cannot be distinguished at this time.

BLinD and Pre-BLinD—conferring undetected risk for AMD progression

BLinD is a thin layer of soft drusen material, in the same compartment as drusen [62]. Previous studies based on histopathology indicated that together BLinD and soft drusen comprised an “Oil Spill” on aging BrM [18, 52] and AMD’s specific deposits. Since BLinD was thought to be undetectable in vivo based on current multimodal imaging technology, our understanding of its clinical significance is limited.

By high-resolution light-microscopic histology and clinicopathologic correlation, we demonstrated that BLinD covered more fundus area than soft drusen, invisibly increasing progression risk [63]. In brief, categories of the sub-RPE-BL lipid including soft drusen, BLinD, pre-BLinD and no lipid were detected in two eyes from one patient (Fig. 10A–E). The percentage of BrM covered by these lipid forms was determined (Fig. 10F). In the right and left eyes, respectively, Drusen + BLinD, together comprising high-risk lesions, accounts for 60–61% of the total area of histologically detectable lipid. Clinically invisible BLinD + pre-BLinD account for 65–72% of this area. Drusen account for only 14–21%. Thus, the area of BLinD was 1.9–3.4 times larger than the drusen area.

Fig. 10. Distribution of sub-RPE-BL lipid in early AMD eye [63].

A A panoramic view of a section showing categories of the sub-RPE-BL lipid. Black dashed frames are magnified in (B–E). B No sub-RPE-BL lipid. C Pre- BLinD is a flat layer of finely granular material in gray (green arrowheads). D Basal linear deposit is an undulating layer of the same extracellular material as in soft drusen (yellow arrowheads), usually continuous with pre-BLinD. E Soft drusen are lump version of the same extracellular material, usually continuous with BLinD. F Sub-RPE-BL lipid distribution in fellow eyes. AMD age-related macular degeneration, BL basal lamina, BLinD basal linear deposit, BLamD basal laminar deposit, Ch choroid, ChC choriocapillaris, d drusen, OS outer segment. All lipid, drusen + BLinD + pre-BLinD. Scale bar in (B) applies to (B–E).

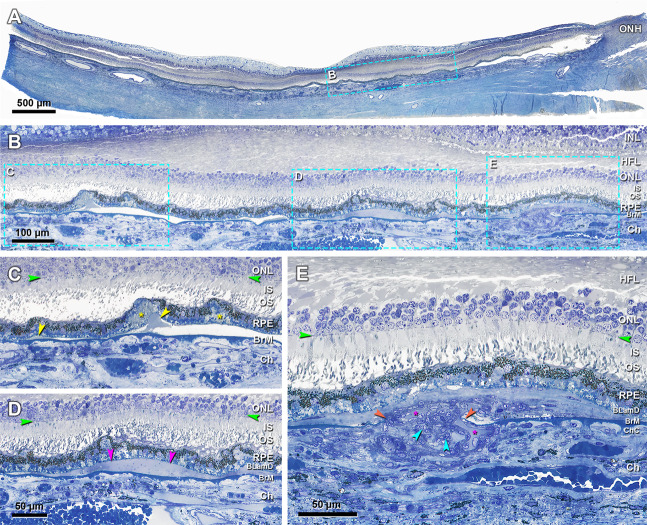

Figure 11 shows the continuity of BLinD and soft drusen with type 1 MNV and exudation [59]. In the sub-RPE-BL space of one continuous histologic section (Fig. 11A, B), four elements were seen: BLinD, a small soft druse (Fig. 11C), fluid (Fig. 11D), and MNV of choroidal origin breaching BrM (Fig. 11E). This is powerful and direct evidence of the role that soft druse material plays in the AMD progression. In another clinicopathologic correlation, we demonstrated that type 1 MNV broke through BrM and invaded the sub-RPE-BL space containing BLinD and soft drusen [4]. Interestingly in the index case, BLinD and soft drusen was either removed or replaced by the invading type 1 MNV. The neovascular membrane supported outer retina structure and good vision during 9 years of follow-up. Type 1 MNV commonly causes exudation and vision loss in AMD progression [64]. In a significant minority of patients, however, type 1 MNV is beneficial, as in our case, and might be detected with OCT angiography [65].

Fig. 11. Continuity of basal linear deposit and soft drusen with type 1 neovascularization and exudation [59].

A Panoramic view of a section that passes through the edge of the foveal floor, judging from the rod-free zone and single row of ganglion cell bodies. Teal frame shows a region magnified in (B). B One continuous compartment contains BLinD and soft druse (frame C), fluid (frame D), and type 1 neovascularization (frame E), magnified in (C–E), respectively. C Druse continuous with BLinD (yellow arrowheads) and fringe of BLinD persists at a site of artifactual separation of BLamD from the inner collagenous layer of BrM. Yellow asterisk, basal mound. D Fluid in the same sub-RPE-basal lamina compartment (fuchsia arrowheads). E Choroidal neovessels with patent lumens (fuchsia asterisks) pass through a break in BrM (orange arrowheads), accompanied by pericytes (teal arrowheads) and fibrous material. An 81-year-old female donor. INL inner nuclear layer. Green arrowheads, ELM external limiting membrane. Scale bar in (D) applies to (C and D).

Discussion and outlook

To contextualize ASHS-LIA, we summarize in the Table 1 angiographic characteristics of different drusen subtypes in AMD. The Table shows that drusen with weak or absent ICG signal are also drusen most clearly associated with AMD progression.

Table 1.

Summary of angiographic characteristics of drusen subtypes.

| FA | ICGA | |

|---|---|---|

| Hard drusena | + | + |

| Soft drusena | − | − |

| Cuticular drusenb | + | +/− |

| Large drusen associated with cuticularb | + | − |

| ASHS-LIA (studies in this review) | Undetectable | − |

Gaps in our understanding of ASHS-LIA can be addressed by future research, using standardized imaging conditions and confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy for ICGA. One objective is to refine the stages of ASHS-LIA using regional distribution, spot size, degree of confluence, and patient age to determine if ASHS-LIA reflects the progression sequence of drusen known from tissue-level studies. Another is to close the conceptual gap between tissue-level studies in European-descent populations with imaging studies from Asian populations with high prevalence of PCV. A third is to investigate the relationship between pachydrusen (solitary drusen with irregular contours) [66, 67], also seen in Asian populations, and ASHS-LIA. A fourth objective is to learn the genetic associations of ASHS-LIA.

To conclude, good evidence supports the hypothesis that ASHS-LIA represents exclusion of a dye that does not bind the principal hydrophobic lipids in BrM and does not gain access to the RPE. It is in the right place and exhibits the right population associations over time to represent the spectrum of age- and AMD-related lipoprotein deposition as learned from tissue-level studies. It has potentially important clinical significance in making it possible to observe the progression of neutral lipid accumulation in BrM in vivo. As a possible risk factor for PCV, ASHS-LIA might help investigations into the pathogenesis of this prevalent disease. Use of ASHS-LIA to image lipid load in individual patients may help resolve long-standing questions about the role of drusen in AMD. While soft drusen material in the form of BLinD could not be appreciated clinically in populations vulnerable to PCV, drusen could be downplayed as important for AMD progression. For the same reason of few apparent drusen, the place of PCV in AMD spectrum could be questioned; perhaps these patients have abundant BLinD instead. ASHS-LIA also might help identify patients at risk for progression, by virtue of having a substantial lipid load. This information is valuable to clinical trials for therapies targeting early or intermediate AMD.

Author contributions

LC, PY, CAC. Visualizing lipid behind the retina in aging and age-related macular degeneration, via indocyanine green angiography (ASHS-LIA). LC: searched literature, made figures, wrote paper, edited paper. PY: edited paper. CAC: searched literature, made figures, wrote paper, edited paper.

Funding

This work was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 82171083) and the Macula Foundation, New York, an anonymous donor to UAB for AMD research, and Heidelberg Engineering. Basic research in drusen biology and AMD histopathology was supported by NIH grant R01EY06109 (CAC).

Competing interests

CAC receives research funds from Genentech/Hoffman La Roche and Regeneron.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Flaxman SR, Bourne RRA, Resnikoff S, Ackland P, Braithwaite T, Cicinelli MV, et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990-2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e1221–e1234. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li M, Dolz-Marco R, Messinger JD, Wang L, Feist RM, Girkin CA, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor-treated type 3 neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:276–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li M, Dolz-Marco R, Huisingh C, Messinger JD, Feist RM, Ferrara D, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2019;39:802–16. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L, Messinger JD, Sloan KR, Swain TA, Sugiura Y, Yannuzzi LA, et al. Nonexudative macular neovascularization supporting outer retina in age-related macular degeneration: a clinicopathologic correlation. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:931–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curcio CA. Soft drusen in age-related macular degeneration: biology and targeting via the oil spill strategies. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:AMD160–AMD181. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-24882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein R, Klein BE, Knudtson MD, Meuer SM, Swift M, Gangnon RE. Fifteen-year cumulative incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:253–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasaki M, Kawasaki R, Uchida A, Koto T, Shinoda H, Tsubota K, et al. Early signs of exudative age-related macular degeneration in Asians. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91:849–53. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spaide RF, Jaffe GJ, Sarraf D, Freund KB, Sadda SR, Staurenghi G, et al. Consensus nomenclature for reporting neovascular age-related macular degeneration data: consensus on neovascular age-related macular degeneration nomenclature study group. Ophthalmology. 2019;127:616–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Zhang X, Li M, Liao N, Wen F. Age-related scattered hypofluorescent spots on late-phase indocyanine green angiography as precursor lesions of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:2102–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.19-26968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarks SH, Arnold JJ, Killingsworth MC, Sarks JP. Early drusen formation in the normal and aging eye and their relation to age related maculopathy: a clinicopathological study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:358–68. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.3.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sura AA, Chen L, Messinger JD, Swain TA, McGwin GJ, Freund KB, et al. Measuring the contributions of basal laminar deposit and Bruch’s membrane in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61:19. doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.13.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnold JJ, Quaranta M, Soubrane G, Sarks SH, Coscas G. Indocyanine green angiography of drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:344–56. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)70826-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiraki K, Moriwaki M, Kohno T, Yanagihara N, Miki T. Age-related scattered hypofluorescent spots on late-phase indocyanine green angiograms. Int Ophthalmol. 1999;23:105–9. doi: 10.1023/A:1026571327117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Zhang X, Liu B, Mi L, Wen F. Age-related scattered hypofluorescent spots on late-phase indocyanine green angiography: the multimodal imaging and relevant factors. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;46:908–15. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoneya S, Saito T, Komatsu Y, Koyama I, Takahashi K, Duvoll-Young J. Binding properties of indocyanine green in human blood. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1286–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito YN, Mori K, Young-Duvall J, Yoneya S. Aging changes of the choroidal dye filling pattern in indocyanine green angiography of normal subjects. Retina. 2001;21:237–42. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holz FG, Bellmann C, Rohrschneider K, Burk RO, Volcker HE. Simultaneous confocal scanning laser fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:227–36. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)80095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curcio CA, Millican CL. Basal linear deposit and large drusen are specific for early age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:329–39. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarks SH. Ageing and degeneration in the macular region: a clinico-pathological study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60:324–41. doi: 10.1136/bjo.60.5.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curcio CA, Presley JB, Millican CL, Medeiros NE. Basal deposits and drusen in eyes with age-related maculopathy: evidence for solid lipid particles. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:761–75. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarks S, Cherepanoff S, Killingsworth M, Sarks J. Relationship of basal laminar deposit and membranous debris to the clinical presentation of early age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:968–77. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Souied EH, Benlian P, Amouyel P, Feingold J, Lagarde JP, Munnich A, et al. The epsilon4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene as a potential protective factor for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:353–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)80146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neale BM, Fagerness J, Reynolds R, Sobrin L, Parker M, Raychaudhuri S, et al. Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7395–400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912019107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng CY, Yamashiro K, Chen LJ, Ahn J, Huang L, Huang L, et al. New loci and coding variants confer risk for age-related macular degeneration in East Asians. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6063. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson LV, Forest DL, Banna CD, Radeke CM, Maloney MA, Hu J, et al. Cell culture model that mimics drusen formation and triggers complement activation associated with age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18277–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109703108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilgrim MG, Lengyel I, Lanzirotti A, Newville M, Fearn S, Emri E, et al. Subretinal Pigment Epithelial Deposition of Drusen Components Including Hydroxyapatite in a Primary Cell Culture Model. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:708–19. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-21060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Lee AJ, Chia EM, Smith W, Cumming RG, et al. Ten-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:92–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudolf M, Clark ME, Chimento MF, Li CM, Medeiros NE, Curcio CA. Prevalence and morphology of druse types in the macula and periphery of eyes with age-related maculopathy. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:1200–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollreisz A, Reiter GS, Bogunovic H, Baumann BA, Jakob A, Schlanitz FG, et al. Topographic distribution and progression of soft drusen in age-related macular degeneration implicate neurobiology of the fovea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62:26. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.2.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudolf M, Curcio CA, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Sefat AMM, Tura A, Aherrahrou Z, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide L-4F removes bruch’s membrane lipids in aged nonhuman primates. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:461–72. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludwig CA, Vail D, Rajeshuni NA, Al-Moujahed A, Rosenblatt T, Callaway NF, et al. Statins and the progression of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0252878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research G. Lutein + zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids for age-related macular degeneration: the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:2005–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Francisco SG, Smith KM, Aragones G, Whitcomb EA, Weinberg J, Wang X, et al. Dietary Patterns, Carbohydrates, and Age-Related Eye Diseases. Nutrients. 2020;12:2862. doi: 10.3390/nu12092862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novotny HR, Alvis D. A method of photographing fluorescence in circulating blood of the human eye. Tech Doc Rep SAMTDR USAF Sch Aerosp Med. 1960;60-82:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flower RW, Hochheimer BF. Clinical infrared absorption angiography of the choroid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972;73:458–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(72)90079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dzurinko VL, Gurwood AS, Price JR. Intravenous and indocyanine green angiography. Optometry. 2004;75:743–55. doi: 10.1016/S1529-1839(04)70234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yannuzzi LA, Slakter JS, Sorenson JA, Guyer DR, Orlock DA. Digital indocyanine green videoangiography and choroidal neovascularization. Retina. 1992;12:191–223. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199212030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang AA, Morse LS, Handa JT, Morales RB, Tucker R, Hjelmeland L, et al. Histologic localization of indocyanine green dye in aging primate and human ocular tissues with clinical angiographic correlation. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1060–8. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)96008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tam J, Liu J, Dubra A, Fariss R. In Vivo Imaging of the Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Mosaic Using Adaptive Optics Enhanced Indocyanine Green Ophthalmoscopy. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:4376–84. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsubara T, Uyama M, Fukushima I, Matsunaga H, Takahashi K. [Histological proof of indocyanine green angiography-healthy eyes]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1999;103:497–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yiu G, Tieu E, Munevar C, Wong B, Cunefare D, Farsiu S, et al. In Vivo Multimodal Imaging of Drusenoid Lesions in Rhesus Macaques. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15013. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14715-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yiu G, Chung SH, Mollhoff IN, Wang Y, Nguyen UT, Shibata B, et al. Long-term evolution and remodeling of soft drusen in rhesus macaques. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61:32. doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.2.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang AA, Zhu M, Billson F. The interaction of indocyanine green with human retinal pigment epithelium. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1463–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rabb MF, Burton TC, Schatz H, Yannuzzi LA. Fluorescein angiography of the fundus: a schematic approach to interpretation. Surv Ophthalmol. 1978;22:387–403. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(78)90134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung JJ, Mrejen S, Freund KB, Yannuzzi LA. Idiopathic multifocal choroiditis with peripapillary zonal inflammation: a multimodal imaging analysis. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2014;8:141–4. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Opremcak EM. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE) Insight. 2013;38:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen L, Zhang X, Li M, Gan Y, Wen F. Drusen and age-related scattered hypofluorescent spots on late-phase indocyanine green angiography, a candidate correlate of lipid accumulation. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:5237–45. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koizumi H, Yamagishi T, Yamazaki T, Kinoshita S. Relationship between clinical characteristics of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and choroidal vascular hyperpermeability. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:305–313 e301. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iida T, Kishi S, Hagimura N, Shimizu K. Persistent and bilateral choroidal vascular abnormalities in central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 1999;19:508–12. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasahara M, Tsujikawa A, Musashi K, Gotoh N, Otani A, Mandai M, et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy with choroidal vascular hyperpermeability. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:601–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanagi Y, Ting DSW, Ng WY, Lee SY, Mathur R, Chan CM, et al. Choroidal Vascular Hyperpermeability as a Predictor of Treatment Response for Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy. Retina. 2018;38:1509–17. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Curcio CA, Johnson M, Rudolf M, Huang JD. The oil spill in ageing Bruch membrane. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:1638–45. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bird AC. Bruch’s membrane change with age. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:166–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.3.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Curcio CA, Millican CL, Bailey T, Kruth HS. Accumulation of cholesterol with age in human Bruch’s membrane. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:265–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson M, Dabholkar A, Huang JD, Presley JB, Chimento MF, Curcio CA. Comparison of morphology of human macular and peripheral Bruch’s membrane in older eyes. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:791–9. doi: 10.1080/02713680701550660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruberti JW, Curcio CA, Millican CL, Menco BP, Huang JD, Johnson M. Quick-freeze/deep-etch visualization of age-related lipid accumulation in Bruch’s membrane. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1753–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarks SH, Van Driel D, Maxwell L, Killingsworth M. Softening of drusen and subretinal neovascularization. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1980;100:414–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang JD, Presley JB, Chimento MF, Curcio CA, Johnson M. Age-related changes in human macular Bruch’s membrane as seen by quick-freeze/deep-etch. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:202–18. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen L, Messinger JD, Kar D, Duncan JL, Curcio CA. Biometrics, Impact, and Significance of Basal Linear Deposit and Subretinal Drusenoid Deposit in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62:33. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pauleikhoff D, Zuels S, Sheraidah GS, Marshall J, Wessing A, Bird AC. Correlation between biochemical composition and fluorescein binding of deposits in Bruch’s membrane. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1548–53. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(92)31768-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang L, Clark ME, Crossman DK, Kojima K, Messinger JD, Mobley JA, et al. Abundant lipid and protein components of drusen. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Curcio CA. Antecedents of Soft Drusen, the Specific Deposits of Age-Related Macular Degeneration, in the Biology of Human Macula. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:AMD182–AMD194. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-24883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen L, Messinger JD, Sloan KR, Wong J, Roorda A, Duncan JL, et al. Abundance and multimodal visibility of soft drusen in early age-related macular degeneration: a clinicopathologic correlation. Retina. 2020;40:1644–8. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen L, Messinger JD, Ferrara D, Freund KB, Curcio CA. Fundus autofluorescence in neovascular age-related macular degeneration, a clinicopathologic correlation relevant to macular atrophy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5:1085–96. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2021.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharma A, Parachuri N, Kumar N, Bandello F, Kuppermann BD, Loewenstein A, et al. Terms non-exudative and non-neovascular: awaiting entry at the doors of AMD reclassification. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259:1381–3. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spaide RF. Disease Expression in Nonexudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration Varies with Choroidal Thickness. Retina. 2018;38:708–16. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang X, Sivaprasad S. Drusen and pachydrusen: the definition, pathogenesis, and clinical significance. Eye (Lond) 2020;35:121–33. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-01265-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sarks JP, Sarks SH, Killingsworth MC. Evolution of soft drusen in age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond) 1994;8:269–83. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balaratnasingam C, Cherepanoff S, Dolz-Marco R, Killingsworth M, Chen FK, Mendis R, et al. Cuticular drusen: clinical phenotypes and natural history defined using multimodal imaging. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:100–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]