Abstract

The most abundant carbon source transported into legume root nodules is photosynthetically produced sucrose, yet the importance of its metabolism by rhizobia in planta is not yet known. To identify genes involved in sucrose uptake and hydrolysis, we screened a Sinorhizobium meliloti genomic library and discovered a segment of S. meliloti DNA which allows Ralstonia eutropha to grow on the α-glucosides sucrose, maltose, and trehalose. Tn5 mutagenesis localized the required genes to a 6.8-kb region containing five open reading frames which were named agl, for α-glucoside utilization. Four of these (aglE, aglF, aglG, and aglK) appear to encode a periplasmic-binding-protein-dependent sugar transport system, and one (aglA) appears to encode an α-glucosidase with homology to family 13 of glycosyl hydrolases. Cosmid-borne agl genes permit uptake of radiolabeled sucrose into R. eutropha cells. Analysis of the properties of agl mutants suggests that S. meliloti possesses at least one additional α-glucosidase as well as a lower-affinity transport system for α-glucosides. It is possible that the Fix+ phenotype of agl mutants on alfalfa is due to these additional functions. Loci found by DNA sequencing to be adjacent to aglEFGAK include a probable regulatory gene (aglR), zwf and edd, which encode the first two enzymes of the Entner-Doudoroff pathway, pgl, which shows homology to a gene encoding a putative phosphogluconolactonase, and a novel Rhizobium-specific repeat element.

Photosynthetically derived sucrose is the main source of carbon for legume root nodules. In fact, sucrose is the first radiolabeled compound found in the root nodules and bacteroids of nodulated plants which are incorporating 14CO2 via photosynthesis (2, 53, 62). The identification of radiolabeled sucrose in the bacteroids in these studies suggests that sucrose is being transported across the symbiosome membrane.

Based on these observations, we thought it possible that sucrose uptake and hydrolysis may be required for, or induced during, symbiosis. However, the possible importance of sucrose metabolism during symbiosis has not yet been evaluated. To date, research on carbon metabolism in indeterminate nodules, such as those formed in the Medicago sativa-Sinorhizobium meliloti symbiosis, has focused on the role of dicarboxylic acids in nitrogen fixation (9, 16, 54, 70). Although it has been demonstrated that transport of dicarboxylic acids is required for nitrogen fixation, it seems unlikely that dicarboxylic acids are required by bacteroids as a carbon source per se. S. meliloti dct mutants, which fail to transport dicarboxylic acids, cannot utilize carbon sources such as succinate in the free-living state (20) and are Fix− (16, 70). However, these strains are able to induce and invade nodules, and they proceed through several stages of bacteroid development, becoming blocked just prior to active nitrogen fixation (64). The efficiency of the tricarboxylic acid cycle is reduced in dct strains, and the defect in nitrogen fixation may be due to failure to produce enough ATP to power the nitrogenase holoenzyme.

Sucrose metabolism has been examined at the biochemical level in both fast- and slow-growing rhizobia (30, 44). No evidence of sucrose phosphorylase activity, required for sucrose uptake via the phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system utilized by enteric bacteria, has been found in fast- or slow-growing rhizobia (44). Studies of disaccharide metabolism have demonstrated that sucrose hydrolysis and uptake activities are inducible in S. meliloti (30). The results of competition studies suggest that S. meliloti possesses at least three systems for disaccharide uptake: one system that transports sucrose, maltose, and trehalose; a second which transports lactose; and a third which transports cellobiose (30). Transport of sucrose in the infection thread has not been investigated.

In these experiments, we sought to identify S. meliloti genes involved in sucrose transport or hydrolysis, so that we could begin to address the question of whether sucrose is utilized during nodule invasion or bacteroid development. Mutants of S. meliloti which cannot utilize sucrose (11) or grow poorly on sucrose (3) have been isolated, but these strains fail to utilize several carbon sources, and the defects in metabolism were found to be downstream of sucrose uptake or cleavage. No genes involved in S. meliloti sucrose uptake or hydrolysis have been identified, nor have mutants of S. meliloti that are unable to utilize sucrose yet retain the ability to utilize fructose and glucose, a key phenotype predicted for strains defective in sucrose hydrolysis or transport, been reported.

Since no Rhizobium mutants that were specifically defective in sucrose utilization had been reported, and we had not succeeded in isolating them by direct screening, we turned to a different strategy. This involved introducing a cosmid library of S. meliloti DNA into a heterologous host unable to utilize sucrose and selecting for derivatives that could grow on sucrose. This type of approach has been used successfully to identify sucrose utilization genes in the phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system by screening in Escherichia coli (25). In our case, E. coli proved to be unsuitable, possibly because its G+C content is so much lower than that of S. meliloti; therefore, we instead used Ralstonia eutropha, a gram-negative soil bacterium with a high (∼66%) G+C content that we have shown in previous work expresses the phbC gene of S. meliloti (68).

We report here the identification of five S. meliloti genes which permit the growth of R. eutropha on sucrose, maltose, or trehalose. These genes evidently encode an α-glucosidase and a system for the transport of α-glucosides. A cosmid carrying these genes permits uptake of radiolabeled sucrose by R. eutropha. In addition, we report the sequence of a putative regulatory locus (aglR), the Entner-Doudoroff genes of S. meliloti, a putative phosphogluconolactonase gene, pgl, and a novel Rhizobium-specific repeat element.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth media.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacterial strains were routinely grown in LB medium (42), which was supplemented with 2.5 mM MgSO4 and 2.5 mM CaCl2 in the case of S. meliloti. Minimal medium M9 (40) supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4, 0.25 mM CaCl2, 1 mg of d-biotin per liter, and 0.4% filter-sterilized carbon source was used to assay the growth of S. meliloti strains. Defined medium MM1N [medium MM1 (50) with the concentration of (NH4)2SO4 increased to 0.2%] supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) filter-sterilized fructose or 0.4% (wt/vol) filter-sterilized sucrose was used to assay growth of R. eutropha strains. Where noted, NH4Cl was substituted for (NH4)2SO4, keeping constant the final concentration of nitrogen in the medium. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 150 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml; gentamicin sulfate, 5 μg/ml for E. coli and 50 μg/ml for S. meliloti; kanamycin sulfate, 50 μg/ml; nalidixic acid, 50 μg/ml; neomycin sulfate, 200 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 10 μg/ml. To select for Tn5 kanamycin was used with E. coli and R. eutropha and neomycin was used with S. meliloti.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Sinorhizobium meliloti | ||

| Rm1021 | SU47 str-21 | 45 |

| SG1001 | Rm1021 agpA::TnphoA | 24 |

| Rm9620 | Rm1021 aglK2::Tn5 | This work |

| Rm9621 | Rm1021 aglE49::Tn5 | This work |

| Rm9622 | Rm1021 aglF95::Tn5 | This work |

| Rm9623 | Rm1021 aglA112::Tn5 | This work |

| Rm9624 | Rm1021 aglG127::Tn5 | This work |

| Rm9625 | Rm1021 aglA279::Tn5 | This work |

| Rm9626 | Rm1021 aglA115::Tn5 | This work |

| Rm9627 | Rm1021 aglA182::Tn5 | This work |

| Rm9628 | Rm1021 aglE192::Tn5 | This work |

| Rm9631 | Rm1021 aglA112::Tn5-233a | This work |

| Rm9632 | Rm1021 aglE49::Tn5-233a | This work |

| Rm9633 | Rm9631 agpA::TnphoA | This work |

| Rm9634 | Rm9632 agpA::TnphoA | This work |

| Ralstonia eutropha H16 | Wild type, Sms | 50 |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | ||

| At123 | GMI9023 ≡ GMI9050 cured of pAtC58 Smr, Rifr | 55 |

| At125 | GMI9023 pRmeSU47bΩ5007::Tn5-oriT Nmr/Kmr | 19 |

| At128 | GMI9023 pRmeSU47aΩ30::Tn5-11 Gmr Spr/Kmr Smr | 19 |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| C2110 | polA Nalr | B. Staskawicz |

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169(φ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Clontech |

| MT614 | MM294 malE::Tn5 | T. M. Finan |

| MT609 | polA1 thy Spr | T. M. Finan |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript SK+ | Ampr, ColE1 cloning vector | Stratagene |

| pBluescript II KS+ | Ampr, ColE1 cloning vector | Stratagene |

| pRK600 | pRK2013 npt::Tn9, Cmr | 19 |

| pPH1JI | IncP, Gmr, Spr | 8 |

| pR751 | IncP, Tpr | 46 |

| pLAFR1 | Tcr, IncP broad-host-range cosmid vector | 23 |

| pSW213 | Tcr, IncP broad-host-range vector | 12 |

| pLW200 | pLAFR1 derivative carrying S. meliloti agl region | This work |

| pLW249 | pLW200 aglE49::Tn5 | This work |

Obtained by replacement of the corresponding Tn5 insertion with Tn5-233 (14).

Genetic techniques.

Conjugal transfer of plasmids was accomplished in triparental matings using pRK600 to provide transfer functions. Plasmid-borne insertions were recombined into the S. meliloti genome via homogenotization as described (18) previously, using pPH1JI or pR751 as the incompatible IncP plasmid. Insertions were then transduced by using bacteriophage φM12 into strain Rm1021 to ensure a clean genetic background. Southern hybridization was performed to check the construction of each strain. To obtain Gmr Spr derivatives of S. meliloti Tn5-induced mutations, Tn5 insertions were replaced with Tn5-233 (14) as previously described (29).

DNA manipulations.

Plasmid and cosmid DNA was isolated from overnight cultures of E. coli by the alkaline lysis method (42) or by purification over a Qiagen column. DNA-modifying enzymes were used according to the instructions of the supplier (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass., or TaKaRa Biomedicals, Shiga, Japan). GeneScreen Plus membranes (Dupont/NEN, Boston, Mass.) were used for Southern hybridizations. Radiolabeled DNA probes were prepared with the NEBlot random labeling kit (New England Biolabs) and [α-32P]dCTP from Dupont/NEN or Amersham.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

Plasmids were purified for sequencing by using a Qiagen plasmid mini kit. The sequencing strategy was based on a detailed restriction map of pLW200. Each of the 10 EcoRI fragments of pLW200 was subcloned into pBluescript SK+. These plasmids and defined subfragments cloned into pBluescript SK+ or pBluescript II KS+ were subjected to fluorescently labeled dideoxy termination reactions at the MIT Biopolymers laboratory or in an MJ Research thermal cycler. The sequencing reactions were then separated on an ABI Prism apparatus at the MIT Biopolymers laboratory or at the Molecular Biology facility at Dartmouth. Contigs were prepared using the SeqMan software program (Lasergene). Comparisons of nucleotide sequences and translated nucleotide sequences were performed by using the BLAST algorithms (1, 28) to search the databases maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Searches of SWISSPROT by using Profile Scan to find PROSITE (5) patterns were performed with the resources maintained by ExPasy in Switzerland. Additional analysis was performed with the package of software developed by the Genetics Computing Group (26), DNA Strider version 1.2, and the DNASTAR programs by Lasergene.

Isolation of cosmids which improve the growth of R. eutropha on sucrose.

An S. meliloti genomic library in pLAFR1 (23) was mated into R. eutropha H16, and transconjugants were selected on MM1N plates containing sucrose as the sole carbon source. In the initial screen, half of the selective plates contained NH4Cl as a nitrogen source and half contained (NH4)2SO4, but all subsequent experiments used (NH4)2SO4 as a nitrogen source. R. eutropha strains carrying pLW200 and related plasmids produced visible colonies after 3 days of incubation and were scored for growth on sucrose after 5 days. After 11 days of incubation at 30°C, these strains produced colonies approximately 4 mm in diameter. A control strain carrying pLAFR1 did not produce visible colonies even after 11 days of incubation at 30°C, although translucent microcolonies could be observed under magnification. All cosmid-containing strains tested produced 4-mm colonies within 4 days on medium containing the permissive carbon source fructose.

Construction of mutagenized plasmids.

Cosmids were mutagenized with Tn5 by using previously described techniques (29). In hundreds of separate matings, pLW200 was conjugally transferred into MT614, which carries a Tn5 insertion in malE. Cosmids were then conjugally transferred into MT609, selecting with spectinomycin, tetracycline, and kanamycin to obtain isolates carrying mutagenized cosmids. Individual colonies were picked and used as donors in triparental matings with R. eutropha H16. R. eutropha transconjugants were selected on MM1N containing fructose, tetracycline, and kanamycin and then challenged to grow on MM1N containing sucrose, tetracycline, and kanamycin. Approximately 10% of the mutagenized cosmids were unable to promote growth on sucrose. Cosmids were conjugally transferred from R. eutropha H16 into E. coli C2110 for DNA preparation and analysis. Cosmid-borne Tn5 insertions were localized by standard restriction mapping techniques.

Sugar transport assays.

[U-14C]sucrose (615 mCi mmol−1; 22.8 GBq mmol−1) was obtained from Amersham Life Science (Buckinghamshire, England). R. eutropha H16 harboring pLAFR1, pLW200, or pLW249 was grown in MM1-tetracycline supplemented with both 0.5% fructose and 0.4% sucrose until the optical density at 600 nm was approximately 0.8. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in MM1-tetracycline containing 0.4% sucrose and incubated for 2 h at 30°C, after which they were pelleted, resuspended in an equal volume of MM1, and incubated without carbon source for 15 min at 30°C. One milliliter was withdrawn for measurement of optical density, and radiolabeled sucrose was added to 2 ml of cells to a final concentration of 1.6 nM. Samples (0.1 ml) were withdrawn in duplicate at 0.5, 3, 5, 7.5, 30, and 60 min after the addition of label, applied to Millipore HA filters under vacuum, and washed twice with 2 ml of MM1. Filters were dried at 68°C for 15 min, and 5 ml of Hydrofluor scintillant (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, Ga.) was added before disintegrations per minute were determined in a Beckman LS 6000SC scintillation counter.

Genetic mapping techniques.

The genes identified in this study were mapped by the method of Finan et al. (19). Genomic DNA from Rm1021 and Agrobacterium tumefaciens At123, At125, and At128 was digested with EcoRI, subjected to electrophoresis in a 0.6% agarose gel, transferred to a GeneScreen Plus membrane, and probed with the insert from pLW201, which contains the C-terminal half of aglG and the majority of aglA.

Plant inoculation assays.

M. sativa cv. Iroquois was obtained from Agway (Plymouth, Ind.). S. meliloti strains were tested for the ability to nodulate alfalfa on nitrogen-free Jensen’s medium as described elsewhere (39). Plants were grown in a constant temperature room at 25°C with a 20-h light cycle. Observations were made weekly for at least 6 weeks. Each nodulation assay included the control treatments of water, wild-type S. meliloti Rm1021, and an exoA mutant, Rm7031 (39). The presence of pink, cylindrical nodules on dark green healthy plants was taken as evidence that nitrogen fixation was occurring. Plants lacking nodules or with ineffective nodules were stunted and chlorotic.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence reported in this work has been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession no. AF045609.

RESULTS

Identification of S. meliloti genomic clones which promote growth on sucrose.

An S. meliloti genomic library was mated into wild-type R. eutropha, and transconjugants were selected on MM1N containing abundant nitrogen and sucrose as the sole carbon source. Approximately 24,000 transconjugants were screened from three separate matings. Fewer than 0.1% of the transconjugants were able to grow on the sucrose plates. We scored colonies for growth by comparing the size of colonies with that of an isogenic strain harboring the vector pLAFR1. Although R. eutropha cannot utilize sucrose as a carbon source, it does form microcolonies on this medium because it is a facultative chemolithotroph capable of using CO2 as a carbon source. These translucent microcolonies were seen only when plates were examined under a dissecting microscope.

In contrast, some transconjugant strains produced visible colonies after 3 days of incubation, and we scored for ability to grow on sucrose after 5 days of incubation. These colonies have the same color and colony morphology as strains grown on fructose. No cosmids which allowed R. eutropha to grow at the same rate on sucrose plates as on fructose were identified, and strains carrying cosmids of interest reached only 4 mm in diameter after 11 days of incubation. Seventeen colonies which permit the growth of the recipient on sucrose were selected for further study.

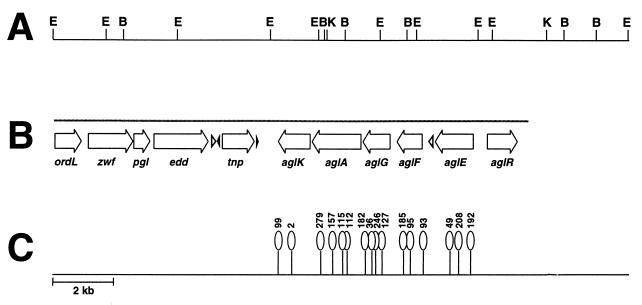

Identification of a segment of S. meliloti DNA that improves the growth of R. eutropha on sucrose.

Restriction mapping revealed that the 17 cosmids chosen appear to contain the same region of the S. meliloti genome. Only two restriction patterns were represented in the candidate cosmids. A 19.4-kb region of DNA is present in each of the cosmids, and two of the cosmids contain an additional 3 kb of DNA. We chose a representative cosmid carrying the smaller insert (pLW200) for further study (Fig. 1A). No single EcoRI restriction fragment from pLW200, when cloned into a broad-host-range vector, was able to confer the growth advantage on sucrose. To identify the region(s) of importance, pLW200 was subjected to transposon Tn5 mutagenesis and subsequently mated into R. eutropha. Transconjugants were selected on MM1N-fructose plates and then tested for the ability to grow on sucrose. Approximately 10% of the transconjugants carrying mutagenized cosmids were unable to grow on sucrose. In all, we isolated more than 70 mutagenized cosmids which failed to promote growth on sucrose. The Tn5 insertions in these cosmids map to a central 6.8-kb region which is required for the improved growth phenotype (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the agl region of S. meliloti. (A) Restriction map of the insert of pLW200. Restriction sites indicated: EcoRI (E), BamHI (B), and KpnI (K). (B) Positions and extents of the putative protein coding regions identified by sequence analysis are shown by open arrows. Open triangles indicate the positions and orientation of RIME1. Black triangles indicate the positions of the 39-bp repeat element. The grey line above the arrows indicates the region sequenced. (C) Positions of Tn5 insertions which eliminate the ability of pLW200 to promote the growth of R. eutropha on the α-glucosides sucrose, maltose, and trehalose.

The same segment of S. meliloti DNA also permits growth of R. eutropha on maltose and trehalose.

To relate our observations to the previous study of disaccharide metabolism by S. meliloti (30), we tested whether the cosmid conferring the ability to grow on sucrose influenced the ability of R. eutropha to grow on maltose, trehalose, or the galactosides lactose and melibiose. The cosmid pLW200 improved the growth of R. eutropha on the α-glucoside disaccharides but not on lactose or melibiose, nor did it influence growth on fructose. pLW249, one of the Tn5 insertion mutants of pLW200 identified because it fails to improve the growth of R. eutropha on sucrose, is also unable to promote growth on maltose or trehalose as a sole carbon source. These results are consistent with the suggestion (30) that S. meliloti uses the same transport system for sucrose, maltose, and trehalose.

DNA sequence suggests this region encodes a binding-protein-dependent transport system for α-glucosides.

Analysis of transposon insertions and DNA sequence data has led to the detection of five loci within the 6.8-kb region identified by Tn5 mutagenesis (Fig. 1B). Since they have been implicated in α-glucoside utilization, we have named these genes agl. The genes are arranged in the order aglEFGAK. On the basis of sequence homologies, aglA appears to encode an α-glucosidase, whereas aglK, aglF, aglG, and aglE appear to encode a periplasmic-binding-protein-dependent transport system. The proposed functions of the deduced gene products and their closest database homologues are summarized in Table 2. Transport of the α-glucosides sucrose, maltose, and trehalose followed by their cleavage by AglA can account for how this set of genes confers the ability to utilize these three sugars.

TABLE 2.

| Deduced protein | Closest database homologue | Protein family | Sequence features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AglK | Agrobacterium radiobacter LacK (66) | ABC ATP-binding cassette proteins | ATP/GTP-binding motif (P-loop) and ABC transporter signature (5) |

| AglA | Bacillus coagulans oligo-1,6-glucosidase (65) | Family 13 of glycosyl hydrolases (α-glucosidases) (31–33) | Contains 7 invariant amino acids found at the active site of α-amylase enzymes (63) |

| AglG | Synechocystis Slr0531 (35, 37) | MalFG family of inner membrane permeases | Inner membrane permease signature (5) |

| AglF | Synechocystis Slr0530 (35, 37) | MalFG family of inner membrane permeases | Inner membrane permease signature (5) |

| AglE | Synechocystis Slr0529 (35, 37) | MalE family of periplasmic sugar binding proteins | |

| AglR | Escherichia coli RafR (4) | LacI family of transcriptional regulators | |

| Zwf | Pseudomonas aeruginosa Zwf (41) | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase signature (5) |

| Pgl | P. aeruginosa Pgl (41) | 6-Phosphogluconolactonase (41) and SOL/DevB family of putative oxidoreductases (57) | |

| Edd | Agrobacterium tumefaciens MocB (38) | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydratase | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydratase signatures (5) |

Mutants of S. meliloti disrupted by insertions in genes carried on pLW200 can utilize sucrose and are Fix+.

All of the Tn5 insertions shown in Fig. 1 were transferred from the mutagenized cosmid into the Rm1021 genome by homogenotization, and the Tn5 insertions were subsequently transduced into Rm1021 to ensure a clean genetic background. The resulting mutants were tested for the ability to utilize various carbon sources. All of the mutants are able to utilize glucose and succinate as carbon sources. S. meliloti aglA mutants, which are disrupted in the gene encoding the putative α-glucosidase, grow as well as or almost as well as wild type in sucrose and trehalose but grow more slowly in liquid cultures containing maltose. S. meliloti aglE mutants, which are disrupted in the putative periplasmic binding protein, and aglF and aglG mutants, which are disrupted in the putative inner membrane permeases, grow more slowly than the wild type or aglA mutant in liquid cultures containing sucrose, maltose, or trehalose and fail to grow in liquid cultures in which the concentration of trehalose or maltose is reduced to 1 mM. aglE, aglF, and aglG mutants form weakly growing colonies on M9 plates containing sucrose, maltose, or trehalose. These data strongly suggest that S. meliloti possesses at least one additional α-glucosidase activity besides the one proposed to be encoded by aglA. Because the mutants defective in the putative transport system are more severely affected than those affected in the putative α-glucosidase, we propose that aglE, aglF, aglG, and aglK encode the major transport system for import of α-glucosides into the cell and that there is at least one other, possibly lower-affinity, pathway for import of these sugars. In addition, because the growth defect is more severe in the aglE and aglF mutants than the aglA mutant, these data suggest that the proposed additional α-glucosidase is not an extracellular enzyme. All of the agl mutants are able to elicit Fix+ nodules on M. sativa.

AglA shares homology with α-glucosidases.

The predicted amino acid sequence of AglA shares homology with many members of family 13 of glycanases, also referred to as the α-amyase family (31–33). The family is composed of proteins with diverse substrate specificities and products (63). Significantly, AglA shares homology with proteins that have been demonstrated to cleave sucrose, trehalose, and oligosaccharides composed of glucose.

aglK, aglF, and aglG appear to encode components of an ATP-dependent inner membrane permease.

The deduced protein AglK shows strong homology to several members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family of cytoplasmic ATP-hydrolyzing peripheral membrane proteins. AglF and AglG are homologous to members of the MalF/MalG family of inner membrane sugar permeases. The E. coli protein MalG has been proposed to be involved in protein-protein interactions with MalK, a cytoplasmic ATP-hydrolyzing peripheral membrane protein and homologue of AglK (13, 48). The hydrophobicity traces for AglF and AglG suggest that they could form six transmembrane domains, consistent with the hypothesis that they are integral membrane proteins. Taken together, it seems likely that AglF and AglG are integral membrane proteins which may be involved in transport of sugar substrates across the inner membrane.

AglE shares homology with periplasmic solute binding proteins.

AglE appears to be a member of the MalE periplasmic solute binding protein family. The closest homologue of AglE is Slr0529, a hypothetical protein of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803, which in turn shares homology with two periplasmic sugar binding proteins: the maltose/maltodextrin binding protein MalE of E. coli (15, 58) and MsmE of Streptococcus mutans, which is involved in the uptake of melibiose, raffinose, and isomaltotriose (56). The highest conservation between MalE, MsmE, Slr0529, and AglE is in a region which in MalE forms the hinge between N- and C-terminal domains and is adjacent to residues which have been shown to contact the substrate in the ligand-bound crystal (60). The structure of maltose binding protein has been compared to those of other periplasmic substrate binding proteins, and although they tend to have very different primary sequences, their three-dimensional structures show many similarities (52).

Support for the inference that AglE is a periplasmic binding protein is provided by gene order in the agl region. In almost every reported case (10), genes encoding periplasmic solute binding proteins are directly upstream of their associated inner membrane permease genes. It seems possible that aglE encodes a periplasmic binding protein which would interact with the putative sugar permeases encoded by aglF and aglG.

AglR, a putative regulatory protein, is homologous to DNA binding proteins.

The aglR open reading frame, upstream of aglE and divergently transcribed, encodes a deduced protein homologous to transcriptional regulators of the lacI family of repressors. Many proteins in this family are involved in catabolite repression of sugar utilization operons. aglR lies outside the 6.8-kb region of pLW200 shown to be required for the utilization of α-glucoside disaccharides by R. eutropha, as would be expected if it serves as a negative regulator of the expression of the other agl genes.

The agl genes permit uptake of sucrose by R. eutropha.

To test our model that the aglE, aglF, aglG, and aglK gene products are involved in transport of α-glucosides, we examined the ability of an R. eutropha strain harboring pLW200 to incorporate radiolabeled sucrose. These experiments were conducted with R. eutropha in order to observe the activity of the agl genes outside the context of other S. meliloti sucrose transport or hydrolysis systems. As shown in Fig. 2, pLW200, which carries the agl genes, is able to promote the uptake of [U-14C]sucrose. This effect is not seen in an isogenic strain carrying the vector pLAFR1 or in a strain harboring pLW249, a derivative of pLW200 which has a Tn5 insertion in the aglE gene. These results suggest that the genes carried on pLW200 encode a functional system for the transport of sucrose.

FIG. 2.

Uptake of [14C]sucrose by R. eutropha H16 harboring pLAFR1 (▴), pLW200 (■), or pLW249 (⧫). OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

The agl region maps to the S. meliloti chromosome.

S. meliloti has three replicons, the chromosome and two megaplasmids of 1.4 and 1.7 Mb (59). The agl region was mapped by Southern hybridization using the method of Finan et al. (19). EcoRI-digested genomic DNA from Rm1021, Rm9623, Rm9624, Rm9625, and A. tumefaciens strains cured of the Ti plasmid and carrying (i) S. meliloti megaplasmid pRmeSU47a, (ii) S. meliloti megaplasmid pRmeSU47b, or (iii) no megaplasmid was probed with the insert from pLW201, which contains the C-terminal half of aglG and the majority of aglA. A strongly hybridizing band of 2.1 kb was observed in the lane containing DNA isolated from Rm1021, and strongly hybridizing bands of approximately 8 kb were present in the lanes containing DNA from the three S. meliloti Tn5 insertion mutants. No bands were seen in the lanes containing DNA from the A. tumefaciens strains, indicating that the locus maps to the S. meliloti chromosome and not to one of the megaplasmids.

Identification of Entner-Doudoroff genes.

Because all of the cosmids identified in our screen had such a large (∼20-kb) overlap, we were interested in whether additional loci involved in sugar metabolism mapped nearby, and we determined the DNA sequence of 7.3 kb downstream of the agl region. Several open reading frames were identified. Of particular interest are two loci, zwf and edd, which appear to encode the first two enzymes of the Entner-Doudoroff pathway. The Entner-Doudoroff pathway is known to be the major pathway for glucose utilization in S. meliloti (61), but these loci have not been previously cloned from S. meliloti. The activities encoded by zwf and edd have been detected in the free-living state and in the bacteroid fraction of alfalfa nodules (36). A nitrosoguanidine-induced mutant of S. meliloti lacking glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity has been isolated (11) and found to be Fix+ on alfalfa, suggesting that this enzymatic activity is not essential during symbiosis or that there may be an additional, developmentally regulated locus encoding this activity.

A small open reading frame between zwf and edd encodes a protein with homology to Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pgl, which is identified in GenBank accession AF029673 as 6-phosphogluconolactonase (41), and we have provisionally named this locus pgl. The location of the pgl gene between zwf and edd is interesting, because 6-phosphogluconolactonase acts between glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase in the Entner-Doudoroff pathway. S. meliloti Pgl also shows homology to the DevB/SOL family of oxidoreductases (57).

Repeat elements and an insertion element in the agl region.

An unusual feature of this region is the presence of two copies of RIME1, a Rhizobium-specific intergenic mosaic element. This repeat element was first identified between chvI and exoS of S. meliloti (49). RIME1 contains two large inverted repeats and was named for its structural similarity to BIME, a repeat element found in enteric bacteria (27). The 5′ copy of RIME1 is found between aglE and aglF, and the 3′ copy is immediately upstream of the insertion sequence described below.

RIMEs have been previously identified by DNA sequencing in S. meliloti, Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234, and Rhizobium leguminosarum (49). In addition, RIME sequences hybridized to DNA from Agrobacterium rhizogenes but not that of A. tumefaciens or Bradyrhizobium japonicum (49). Although Østerås et al. (49) reported that no copies of RIME were identified on the Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 megaplasmid by Southern hybridization, we were able to identify three copies of RIME1 by performing a BLASTN search of the symbiotic megaplasmid of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 (22). We also identified additional copies in Rhizobium trifolii and the phoCDET (6) and exp (7) regions of S. meliloti. All copies of RIME1 found to date are located in intergenic regions or overlapping the coding region by a few bases.

We have also identified a novel insertion element between edd and aglK. This insertion element consists of an apparently fragmented reading frame flanked by 39-bp terminal inverted repeats. The nucleotide sequence in this region is highly homologous to the Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 megaplasmid locus y4zb, and the S. meliloti potential coding region encodes a polypeptide with strong homology (interrupted by in-frame stop codons) to the hypothetical protein Y4zb. Y4zb is thought to be a transposase, but the y4zb locus is not flanked by the terminal inverted repeats seen in S. meliloti. Both Y4zb and its S. meliloti homologue exhibit limited homology to transposases from Bacillus stearothermophilus (69) and insertion sequences, and we have therefore tentatively named the locus tnp. It is possible that this locus is, or at one time during the evolution of the strain had been, involved in integration or recombination functions.

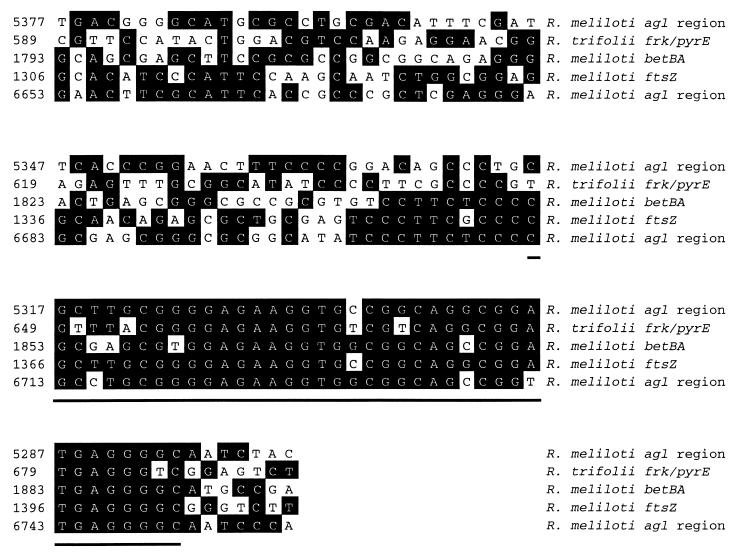

The 39-bp terminal inverted repeats show homology to intergenic sequences in S. meliloti and R. trifolii. We observed that this 39-bp sequence is 100% conserved in an intergenic region downstream of S. meliloti ftsZ (43). We also found that the same 39 bp are 87% conserved with a sequence between the S. meliloti betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (betB) and choline dehydrogenase (betA) genes (51) and are 86% conserved with sequence overlapping the stop site of the Rhizobium trifolii fructokinase (frk) gene (17). These data are shown in Fig. 3. It seems possible that these occurrences of the 39-bp repeat element represent former sites of genomic recombination.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the intergenic regions of S. meliloti agl region, S. meliloti ftsZ (L25440), R. trifolii frk pyrE (U08434) and S. meliloti betBA (U39940). The 39-bp terminal repeat element which flanks tnp in the S. meliloti agl region is underlined.

DISCUSSION

We have isolated a cosmid containing S. meliloti DNA which is able to promote growth on sucrose, maltose, or trehalose and have obtained Tn5 insertions in the cosmid which abolish that ability. DNA sequencing led to the identification of five possible protein coding regions within the boundaries defined by Tn5 insertions. We have demonstrated that the cosmid promotes the uptake of radiolabeled sucrose by R. eutropha and that S. meliloti agl mutants are affected for growth on α-glucosides. Considering these data and incorporating inferences made about these proteins on the basis of their deduced amino acid sequences, we propose that the AglEFGK proteins form a periplasmic-binding-protein-dependent transport system for α-glucoside disaccharides and that AglA is an α-glucosidase active on the disaccharides trehalose, sucrose, and maltose. Although agl mutants grow more slowly on α-glucoside disaccharides, they can still utilize these carbon sources and our model therefore accounts for these observations by including at least one additional mechanism for transporting and cleaving sucrose, maltose, and trehalose.

If our model is correct and S. meliloti possesses more than one glycanase which is able to cleave sucrose, maltose, and trehalose, it would not be the first example of redundant glycanase activity in S. meliloti. exoK mutants, which are deficient in the production of an extracellular glycanase active on the acidic exopolysaccharide succinoglycan, still possess succinoglycan-cleaving activity. Three loci, exsH, prsD, and prsE, were found to encode the second glycanase and the system required to export the glycanase (71). The S. meliloti genome is approximately 6.6 Mb, severalfold larger than the genome of Haemophilus influenzae (21), and so the existence of redundant functions is perhaps not too surprising.

The agl genes encode one of the first periplasmic-binding-protein-dependent transport systems identified in S. meliloti. Gage and Long have identified a gene encoding an S. meliloti periplasmic binding protein required for transport of α-galactosides (24). The agpA (α-galactoside permease) gene that they have found is homologous to opp genes encoding oligopeptide permeases (34). A TnphoA insertion in agpA renders S. meliloti unable to grow on α-galactosides but does not affect the symbiotic properties of the strain. To test whether removal of both the agp and agl systems would affect symbiosis, we constructed double mutants which are disrupted in the genes encoding the α-galactoside binding protein (agpA) and either the proposed α-glucoside binding protein (aglE) or glycosyl hydrolase (aglA). Both the agpA aglE and agpA aglA strains are still able to utilize α-glucosides and are Fix+. In addition to the periplasmic-binding-protein-dependent systems for α-glucosides and α-galactosides, S. meliloti appears to contain a periplasmic-binding-protein-dependent system for fructose uptake. Williams et al. showed that an S. meliloti periplasmic protein cross-reacts with an antibody raised against the A. radiobacter fructose binding protein (67). However, the genes encoding the presumed fructose transport system have not been identified.

One of the most novel inferences to come out of this work is that aglE may encode a periplasmic binding protein with specificity for sucrose, maltose, and trehalose. If our model is correct, to our knowledge we have identified the first bacterial periplasmic sugar binding protein which specifically binds to sucrose, maltose, and trehalose. Although the deduced protein AglE shares only weak homology with E. coli MalE, the region of highest homology is adjacent to residues known to be involved in substrate binding. The region of starch filled cells in interzone II-III of alfalfa nodules (64) raises the possibility that the starch breakdown product maltose could be a carbon source for bacteroids. Our model also implies that the uncharacterized Synechocystis proteins Slr0529, Slr0530, and Slr0531 are involved in sugar transport. Sucrose and trehalose are known to be transported by Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 (47), but no genes have yet been assigned to those functions.

We have characterized the DNA region which lies downstream of the agl genes and found several open reading frames which appear to encode enzymes involved in oxidation-reduction reactions. Although only the agl genes, located in the central 7 kb of the approximately 20 kb found in all the cosmids isolated in this work, were shown to be required for α-glucoside utilization, the zwf and edd genes are proposed to be involved in metabolism of the monosaccharides produced after cleavage of sucrose, trehalose, and maltose. zwf and edd are the first examples of Entner-Doudoroff genes cloned from Rhizobium, Sinorhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, or Azorhizobium. The substrates for the products of pgl and ordL are unknown.

The presence of two copies of RIME1 in this region is intriguing. No one knows the function or origin of RIME1, but it could represent leftover termini from transposition or cross-species lateral transfer events. The inverted repeats of RIME could act as a binding site for a regulatory protein. If RIME1 is able to form hairpins, and these hairpins act as transcriptional terminators, it is possible that premature termination could occur at RIME1, leading to an abundance of truncated transcript containing only aglE and a paucity of full-length transcripts. This hypothesis is interesting because it has been shown that E. coli periplasmic substrate binding proteins such as MalE are approximately 30 times as numerous in the cell as their cognate integral membrane permeases (10). This disparity is thought to reflect transcriptional differences, and a REP repeat element found between malE and malF is believed to be involved. Alternatively, the difference could be accounted for by differences in ribosome binding site strength. As more genomes are sequenced, several repeat elements and mosaic elements will undoubtedly be found and may prove useful as tools for taxonomic studies.

Because S. meliloti mutants disrupted in agl genes encoding the putative transport system are severely affected in their growth on α-glucosides, it appears that aglEFGK encode the major system for transport of these sugars. These results are consistent with the report that S. meliloti uses the same uptake system to transport sucrose, maltose, and trehalose (30). Identification of the sucrose utilization system encoded by the agl genes should help to make it possible to screen for mutants defective in sucrose utilization and thus evaluate the importance of sucrose metabolism during the nodulation process. Indeed, preliminary results indicate that it is possible to isolate mutants of either aglA or aglE strains that are unable to metabolize the α-glucosides sucrose, maltose, and trehalose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant GM31030 awarded to G.C.W.

We thank Dan Gage for communication of unpublished results and members of the laboratory for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoniw L D, Sprent J I. Primary metabolites of Phaseolus vulgaris nodules. Phytochemistry. 1978;17:675. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias A, Cerveñansky C, Gardiol A, Martinez-Drets G. Phosphoglucose isomerase mutant of Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:409–414. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.1.409-414.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aslanidis C, Schmid K, Schmitt R. Nucleotide sequences and operon structure of plasmid-borne genes mediating uptake and utilization of raffinose in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6753–6763. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6753-6763.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bairoch A. PROSITE: a dictionary of sites and patterns in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2013–2018. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.suppl.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bardin S, Dan S, Østerås M, Finan T M. A phosphate transport system is required for symbiotic nitrogen fixation by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4540–4547. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4540-4547.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker A, Rüberg S, Küster H, Roxlau A A, Keller M, Ivashina T, Cheng H-P, Walker G C, Pühler A. The 32-kilobase exp gene cluster of Rhizobium meliloti directing the biosynthesis of galactoglucan: genetic organization and properties of the encoded gene products. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1375–1384. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1375-1384.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beringer J E, Benyon J L, Buchanan-Wollaston A V, Johnston A W B. Transfer of the drug-resistance transposon Tn5 to Rhizobium. Nature. 1978;276:633–634. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolton E, Higgisson B, Harrington A, O’Gara F. Dicarboxylic acid transport in Rhizobium meliloti: isolation of mutants and cloning of dicarboxylic acid transport genes. Arch Microbiol. 1986;144:142–146. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boos W, Lucht J M. Periplasmic binding protein-dependent ABC transporters. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1175–1209. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cerveñansky C, Arias A. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in pleiotropic carbohydrate-negative mutant strains of Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:1027–1030. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.1027-1030.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen C-Y, Winans S C. Controlled expression of the transcriptional activator gene virG in Agrobacterium tumefaciens by using the Escherichia coli lac promoter. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1139–1144. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1139-1144.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dassa E. Sequence-function relationships in MalG, an inner membrane protein from the maltose transport system in E. coli. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:39–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Vos G F, Walker G C, Signer E R. Genetic manipulations in Rhizobium meliloti using two new transposon Tn5 derivatives. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;204:485–491. doi: 10.1007/BF00331029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duplay P, Bedouelle H, Fowler A, Zabin I, Saurin W, Hofnung M. Sequences of the malE gene and of its product, the maltose-binding protein of Escherichia coli K12. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:10606–10613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelke T H, Jagadish M N, Pühler A. Biochemical and genetic analysis of Rhizobium meliloti mutants defective in C4-dicarboxylate transport. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:3019–3029. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fennington G J, Hughes T A. The fructokinase from Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii belongs to group I fructokinase enzymes and is encoded separately from other carbohydrate metabolism enzymes. Microbiology. 1996;142:321–330. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-2-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finan T M, Hartwieg E K, LeMieux K, Bergman K, Walker G C, Signer E R. General transduction in Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:120–124. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.120-124.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finan T M, Kunkel B, de Vos G F, Signer E R. Second symbiotic megaplasmid in Rhizobium meliloti carrying exopolysaccharide and thiamine synthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:66–72. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.66-72.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finan T M, Oresnik I, Bottacin A. Mutants of Rhizobium meliloti defective in succinate metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3396–3403. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3396-3403.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J-F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, Mckenney K, Sutton G, Fitzhugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J D, Scott J, Shirley R, Liu L-I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, Mcdonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–498. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. , 507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freiberg C, Fellay R, Bairoch A, Broughton W J, Rosenthal A, Perret X. Molecular basis of symbiosis between Rhizobium and legumes. Nature. 1997;387:394–401. doi: 10.1038/387394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman A M, Long S R, Brown S E, Buikema W J, Ausubel F M. Construction of a broad host range cosmid cloning vector and its use in the genetic analysis of Rhizobium mutants. Gene. 1982;18:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gage D, Long S. α-Galactoside uptake in Rhizobium meliloti: isolation and characterization of agpA, a gene encoding a periplasmic binding protein required for melibiose and raffinose utilization. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5739–5748. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5739-5748.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia J L. Cloning in Escherichia coli and molecular analysis of the sucrose system of the Salmonella plasmid SCR-53. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;201:575–577. doi: 10.1007/BF00331358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genetics Computer Group. Program manual for the GCG package. Madison, Wis: Genetics Computer Group; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilson E, Saurin W, Perrin D, Bachellier S, Hofnung M. Palindromic units are part of a new bacterial interspersed mosaic element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1375–1383. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.7.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gish W, States D J. Identification of protein coding regions by database similarity search. Nat Genet. 1993;3:266–272. doi: 10.1038/ng0393-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glazebrook J, Walker G C. Genetic techniques in Rhizobium meliloti. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:398–418. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04021-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glenn A R, Dilworth M J. The uptake and hydrolysis of disaccharides by fast- and slow-growing species of Rhizobium. Arch Microbiol. 1981;129:233–239. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henrissat B. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1991;280:309–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. New families in the classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1993;293:781–788. doi: 10.1042/bj2930781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henrissat B, Romeu A. Families, superfamilies and subfamilies of glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem J. 1995;311:350–351. doi: 10.1042/bj3110350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hiles I D, Gallagher M P, Jamieson D J, Higgins C F. Molecular characterization of the oligopeptide permease of Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1987;195:125–142. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirosawa M, Kaneko T, Tabata S. Cyanobase: visual presentation of information on the genome of Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 through WWW. In: Hagiya M, et al., editors. Proceedings of Genome Informatics Workshop 1995. Tokyo, Japan: Universal Academy Press; 1995. pp. 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irigoyen J J, Sanchez-Diaz M, Emerich D W. Carbon metabolism enzymes of Rhizobium meliloti cultures and bacteroids and their distribution within alfalfa nodules. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2587–2589. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2587-2589.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim K-S, Farrand S K. Ti plasmid-encoded genes responsible for catabolism of the crown gall opine mannopine by Agrobacterium tumefaciens are homologs of the T-region genes responsible for synthesis of this opine by the plant tumor. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3275–3284. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3275-3284.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leigh J A, Signer E R, Walker G C. Exopolysaccharide-deficient mutants of Rhizobium meliloti that form ineffective nodules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6231–6235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long S, Reed J W, Himawan J, Walker G C. Genetic analysis of a cluster of genes required for synthesis of the calcofluor-binding exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4239–4248. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4239-4248.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma J F, Hager P W, Howell M L, Phibbs P V, Hassett D J. Cloning and characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa zwf gene encoding glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, an enzyme important in resistance to methyl viologen (paraquat) J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1741–1749. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1741-1749.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Margolin W, Long S R. Rhizobium meliloti contains a novel second homolog of the cell division gene ftsZ. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2033–2043. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.2033-2043.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martinez-de Drets G, Arias A, de Cutinella M R. Fast- and slow-growing rhizobia: differences in sucrose utilization and invertase activity. Can J Microbiol. 1974;20:605–609. doi: 10.1139/m74-092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meade H M, Long S R, Ruvkun G B, Brown S E, Ausubel F M. Physical and genetic characterization of symbiotic and auxotrophic mutants of Rhizobium meliloti induced by transposon Tn5 mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:114–122. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.114-122.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyer R J, Shapiro J A. Genetic organization of the broad-host-range IncP-1 plasmid R751. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:1362–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.3.1362-1373.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mikkat S, Effmert U, Hagemann M. Uptake and use of the osmoprotective compounds trehalose, glucosylglycerol, and sucrose by the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Arch Microbiol. 1997;167:112–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikaido H. Maltose transport system of Escherichia coli: an ABC-type transporter. FEBS Lett. 1994;346:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Østerås M, Stanley J, Finan T M. Identification of rhizobium-specific intergenic mosaic elements within an essential two-component regulatory system of Rhizobium species. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5485–5494. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5485-5494.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peoples O P, Sinskey A J. Poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) biosynthesis in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16: identification and characterization of the PHB polymerase gene (phbC) J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15298–15303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pocard J A, Vincent N, Boucompagni E, Tombras-Smith L, Poggi M C, le Rudulier D. Molecular characterization of the bet genes encoding glycine betaine synthesis in Sinorhizobium meliloti 102F34. Microbiology. 1997;143:1369–1379. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-4-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quiocho F A, Ledvina P S. Atomic structure and specificity of bacterial periplasmic receptors for active transport and chemotaxis: variation of common themes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romanov V I, Hajy-zadeh B R, Ivanov B F, Shaposhnikov G L, Kretovich W L. Labelling of lupine nodule metabolites with 14CO2 assimilated from the leaves. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:2157–2160. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ronson C W, Lyttleton P, Robertson J G. C4-dicarboxylate transport mutants of Rhizobium trifolii form ineffective nodules on Trifolium repens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;82:6231–6245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rosenberg C, Huguet T. The pAtC58 plasmid is not essential for tumor induction. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;196:533–536. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Russell R R, Aduse-Opoku J, Sutcliffe I C, Tao L, Ferretti J J. A binding protein-dependent transport system in Streptococcus mutans responsible for multiple sugar metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4631–4637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shen W-C, Stanford D R, Hopper A K. Los1p, involved in yeast pre-tRNA splicing, positively regulates members of the SOL gene family. Genetics. 1996;143:699–712. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shuman H A. Active transport of maltose in Escherichia coli K12. Role of the periplasmic maltose-binding protein and evidence for a substrate recognition site in the cytoplasmic membrane. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:5455–5461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sobral B W S, Honeycutt R J, Atherly A G, McClelland M. Electrophoretic separation of the three Rhizobium meliloti replicons. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5173–5180. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.16.5173-5180.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spurlino J C, Lu G Y, Quiocho F A. The 2.3-Å resolution structure of the maltose- or maltodextrin binding protein, a primary receptor of bacterial active transport and chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5202–5219. doi: 10.2210/pdb1mbp/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stowers M D. Carbon metabolism in Rhizobium species. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1985;39:89–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.39.100185.000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Streeter J G. Transport and metabolism of carbon and nitrogen in legume nodules. In: Callow J A, editor. Advances in botanical research. London, England: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 129–187. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Svensson B. Protein engineering in the α-amylase family: catalytic mechanism, substrate specificity, and stability. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:141–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00023233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vasse J, deBilly F, Camut S, Truchet G. Correlation between ultrastructural differentiation of bacteroids and nitrogen fixation in alfalfa nodules. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4295–4306. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4295-4306.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watanabe K, Kitamura K, Suzuki Y. Analysis of the critical sites for protein thermostabilization by proline substitution in oligo-1,6-glucosidase from Bacillus coagulans ATCC 7050 and the evolutionary consideration of proline residues. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2066–2073. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2066-2073.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Williams S G, Greenwood J A, Jones C W. Molecular analysis of the lac operon encoding the binding-protein-dependent lactose transport system and β-galactosidase in Agrobacterium radiobacter. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1755–1768. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams S G, Greenwood J A, Jones C W. Agrobacterium radiobacter and related organisms take up fructose via a binding-protein-dependent active-transport system. Microbiology. 1995;141:2601–2610. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-10-2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Willis L B, Walker G C. The phbC (poly-β-hydroxybutyrate synthase) gene of Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) meliloti and characterization of phbC mutants. Can J Microbiol. 1998;44:554–564. doi: 10.1139/w98-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu K, He Z Q, Mao Y M, Sheng R Q, Sheng Z J. On two transposable elements from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Plasmid. 1993;29:1–9. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yarosch O K, Charles T C, Finan T M. Analysis of C4-dicarboxylate transport genes in Rhizobium meliloti. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:813–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.York G M, Walker G C. The Rhizobium meliloti exoK and prsD/prsE/exsH genes are components of independent degradative pathways which contribute to production of low-molecular-weight succinoglycan. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:117–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4481804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]