Abstract

Background: The Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is a very important and effective policy in the health system of countries worldwide. Using the experiences and learning from the best practices of successful countries in the UHC can be very helpful. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to provide a scoping review of successful global interventions and practices in achieving UHC.

Methods: This is a scoping review study that has been conducted using the Arkesy and O'Malley framework. To gather information, Embase, PubMed, The Cochrane Library, Scopus, Scientific Information Database, and MagIran were searched using relevant keywords from 2000 to 2019. Studies about different reforms in health systems and case studies, which have examined successful interventions and reforms on the path to UHC, were included. Articles and abstracts presented at conferences and congresses were excluded. Framework Analysis was also used to analyze the data.

Results: Out of 4257 articles, 57 finally included in the study. The results showed that of the 40 countries that had successful interventions, most were Asian. The interventions were financial protection (40 interventions that were categorized into 14 items), service coverage (31 interventions categorized into 7 items), population coverage (36 interventions categorized into 9 items), and quality (18 interventions categorized into 7 items), respectively. Also, the positive results of interventions on the way to achieving UHC were financial protection (14 interventions), service coverage (7 interventions), population coverage (9 interventions), and quality (7 interventions), respectively.

Conclusion: This study provides a comprehensive and clear view of successful interventions in achieving the UHC. Therefore, with consideration to lessons learned from successful interventions, policymakers can design appropriate interventions for their country.

Keywords: Universal Health Coverage, Health Care Reform, Financing, Services Coverage, Quality, Scoping Review

What is “already known” in this topic

The UHC approach has been highly considered by countries in the last two decades, and these countries have taken many steps with success or failure in the road of achieving UHC. Accordingly, reviewing and learning from the successful interventions of other countries and learning from these experiences in the field of UHC can be very useful.

What this article adds

This study provides the comprehensive and clear view of successful interventions performed in most countries at different income levels, which seek to achieve the UHC. Reporting these successful interventions can be a model and guide for other countries to avoid the costs and recurring mistakes.

Introduction

The UHC has been introduced by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a viable approach and a way for countries to access equitable health services and ultimately a healthy community (1, 2). The UHC can be accepted as a very important and effective policy in the health system of countries, which can improve the quality of people's lives to an acceptable level by providing equitable quality health services to all people everywhere without any financial pressure (3-11). Thus, achieving UHC can have a significant impact on health promotion, easier access to health care for those in need, and improved public health, especially for the poor (12, 13).

Given the importance of achieving UHC for high- and middle-income countries, the number of countries trying to achieve this has increased in the last 2 decades (14, 15). In addition, nowadays, countries by increasing their knowledge and awareness of strategies and applying the experiences of successful countries as well as acquiring the necessary capabilities to meet their urgent needs, are trying to take the path of achieving UHC (16-18). Like other high-income countries that have achieved UHC, low- and middle-income countries, with taking into account the structure and resources that they have on the path to UHC undertake measures, such as mobilizing resources, fulfilling the political commitments necessary to implement health-related policies, and implementing effective reforms and interventions in macronational policies (1, 19-21). The UHC can be one of the most challenging political processes that require the support of various stakeholders, including health system policymakers (4). Although all countries pursue the same goal of achieving UHC, the path and duration of achieving this goal depend on the structure and resources of the countries as well as the specific effective factors of each country (4).

Given the specific circumstances of each country, there is no uniform way of achieving UHC, and countries act based on their structural strengths and weaknesses. (4, 22-24). To achieve UHC, countries need to identify their strategic issue. For example, in the field of stewardship, financing, resources generation, and service provision, each country based on its health system needs, identifies effective factors, such as prioritizing health system reforms according to its own factors, such as prioritizing health system reforms (25), considering organizational structure and its capacity (26-28), having national and political commitment (29-32), economic growth (33-35), financial protection (36-39), health insurance coverage (15, 34, 40), prevention of catastrophic costs (41, 42), reduction of out-of-pocket payments (41, 43-49), health insurance prepayment (40, 50-53), national policies for human resources training (25-27) and geographical distribution of services (54-57), and given its weaknesses or strengths in these functions, to reform and strengthen its health system on the path to UHC.

On the path to UHC, it is crucial to consider the functions of the health system and reform these functions based on the specific circumstances of the countries. In this regard, using the experiences of other countries and learning from the best practices in successful countries in the field of UHC can be highly useful. The definition of the best practices in this study is to paying attention to the experiences and successful interventions of countries’ health systems in the achievement of UHC.Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to review the successful global interventions and practices to achieve UHC in the form of a scoping review.

- Identify successful financial protection interventions, reforms, and practices in achieving UHC

- Identify interventions, improvements, and successful service coverage practices in achieving UHC

- Identify successful population coverage interventions, reforms, and practices in achieving UHC

- Identify successful interventions, reforms, and practices in the quality of health services in achieving UHC

Methods

This was is a scoping review study conducted in 2019 based on the book "A Systematic Review to Support Evidence-Based Medicine" (58).

Information Sources

Required information was searched in the Embase, PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Scopus, Scientific Information Database, and MagIran from January 2000 until the end of January 2019. The keywords of Universal health coverage, Universal health care coverage, Universal health care coverage, Universal coverage, UHC, Strength,* Transform,* interventions, improve,* program,* innovations, initiative, Financing, "Service delivery", Stewardship, and "Resource generation" were used in the search. Some specialized journals, Google Scholar, and the references of included articles were reviewed manually. The databases of the European Association for Gray Literature Exploitation and the Health Care Management Information Consortium as well as the WHO and World Bank sites were also searched (Table 1).

Table 1. Complete Search Strategy for PubMed Databases.

| Set | Strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | (((("universal health care coverage") OR "universal healthcare coverage"[Title/Abstract]) OR "universal health coverage"[Title/Abstract]) OR "universal coverage"[Title/Abstract]) OR "UHC"[Title/Abstract] Filters: Publication date from 2000/01/01 to 2019/1/31; English | 3735 |

| #2 | (Strength [TIAB] OR Strengthes [ TIAB] OR Transfor [TIAB] OR Transfores [TIAB] OR intervention [TIAB] OR interventions [TIAB] OR improve [TIAB] OR improvement [TIAB] OR programm [TIAB] OR programmes [TIAB] OR initiative [TIAB] OR initiatives [TIAB] OR innovation [TIAB] OR innovations [TIAB] OR Financing [TIAB] OR Financings [TIAB] OR "Service delivery" [TIAB] OR Stewardship [TIAB] OR "Resource generation" [TIAB]) Filters: Publication date from 2000/01/01 to 2019/1/31; English | 1958401 |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | 1666* |

| * Filters activated: Publication date from 2000/01/01 to 2019/1/31, English. | ||

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria: All observational (descriptive studies about different reforms in health systems) and intervention studies, especially case studies, which have examined successful interventions and reforms of countries on the path to UHC and published between 2000 and 2019, were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria: Articles and abstracts presented at conferences and congresses as well as studies that did not report successful interventions were excluded.

Review Process:

In this study, the Arkesy and O'Malley frameworks for scoping review were used. This framework is the first methodological framework for conducting scoping review research published in 2005 (59). The framework consists of 6 steps: (1) identification of the research question; (2) identification of relevant studies, (3) study selection; (4) Data charting; (5) data analysis and reporting the results; and (6) consultation exercise. The study also used the (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) PRISMA framework to report the results (60, 61).

The study process was such that initially the titles of all articles were reviewed and articles that were incompatible with the aims of the study were excluded. Subsequently, abstracts and full-texts of the articles were studied, respectively, and studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria and had poor correlation with study aims were identified and excluded. Data were extracted according to a researcher-made data extraction form, and entered into the designed table. At first, as a pilot for data extraction form, the data of 5 papers were extracted and the deficiencies of the original form were eliminated. The whole process of systematic review was performed by 2 researchers independently and disputes were referred to a third researcher.

Given that it was necessary to study the full-text of the included studies to extract data, this was done by the research team in 2 stages. However, in the third and fourth stages of the Arkesy and O'Malley frameworks, after the initial extraction of the data from the selected studies, the research team reexamined the data in 2 sessions carefully and, finally, the studies were rescreened by the research team to include precisely relevant and high-quality studies. Endnote X9 software was also used to organize study titles and abstracts as well as identify duplicates.

Data Analysis

The framework analysis was used to analyze the data, which is a hierarchical approach used to classify and organize data based on key themes, concepts, and emerging classes. Data were extracted by 2 researchers and entered in to data extraction table. The steps for analyzing and coding the data were (1) familiarity with the text of articles (immersion in article results); (2) identifying and extracting primary themes (identifying and extracting more articles relevant to primary themes); (3) placing articles in determined themes, (4) reviewing and completing the results of each theme with the use of results of the articles and ensuring the reliability of the themes and the results extracted in each theme (in cases of disagreement between the 2 coders, the dispute was referred to the third researcher). Textual data were analyzed manually and categorized into dimensions of UHC (financial protection, population coverage, service coverage, and quality) using the framework analysis method (62, 63). In case of disagreement between researchers, the study was reviewed by a third person who was an expert, and with the authors' consensus, the proper function was selected.

Results

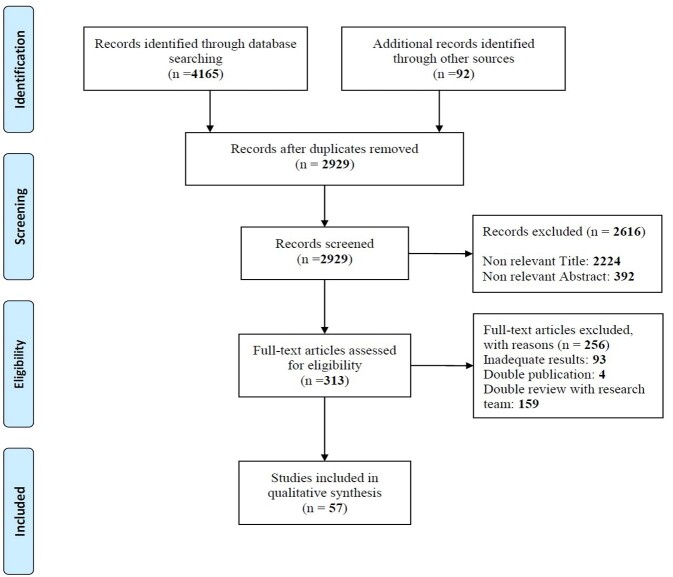

Of the 4257 articles found, 1328 were excluded as duplicate papers and 2616 were excluded in title and abstract reviews. Also, of the 313 articles entered the full-text review phase, 256 were excluded because of lack of appropriate information and lack of reporting of the required information as well as rescreening of the full-text. Finally, 57 articles were included in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the searches and Inclusion process.

The results of included studies are summarized in supplementary file1 (Appendix 1).

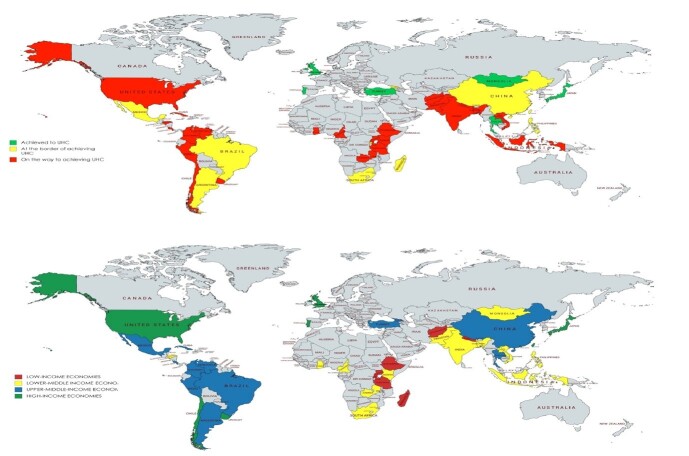

Country of Study

Studies published on successful interventions to achieve UHC were conducted in 40 countries. Most studies were in Asia, with 14 countries, and the least in European countries with 4 studies. Most studies were conducted in Thailand (6 studies), China (6 studies), Mexico (6 studies), and Brazil (6 studies). Among these countries, 5 achieved to UHC, 11 were at the border of achieving, and others were on the path to UHC. Also, according to the latest World Bank classification in 2019-2020 (64), 9 studies were conducted in low-income countries (LICs), 13 in lower-middle income countries (LMIC), 18 in upper-middle income countries (UMIC) and 9 studies in High-Income Countries (HIC), and 8 in more than 1 country (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Countries’ successful interventions on the path to UHC with different condition and suc-cessful interventions in achieving UHC in countries based on the World Bank’s latest classification.

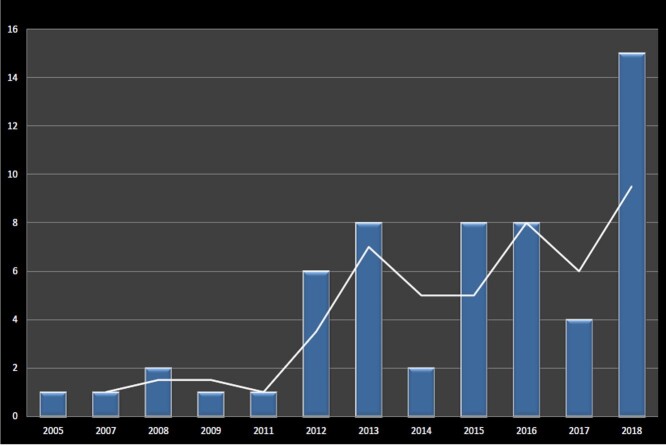

Trend of Publications Year

The time trend of the studies’ publication shows that most of the studies, except for 2, were published after the announcement of UHC as a global, international health policy for all countries by the WHO in 2008, and most of studies (n = 15 studies) were published in 2018 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The time trend of interventional studies' publication on the path to UHC

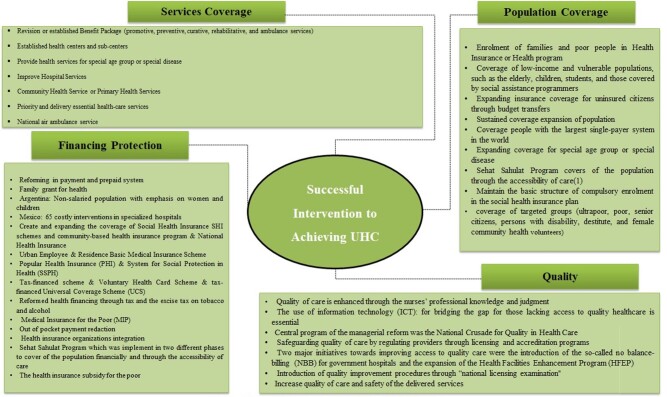

Interventions According to the Dimensions of UHC

According to the type of interventions in each of the UHC dimension, interventions were categorized into different parts as follows: financial protection (40 interventions categorized into 14 items), service coverage (31 interventions categorized into 7 items), population coverage (36 interventions categorized into 9 items), and quality (18 interventions categorized into 7 items). The most and the least interventions were financial protection and quality, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Successful interventions in achieving UHC in countries

Successful Results of Interventions

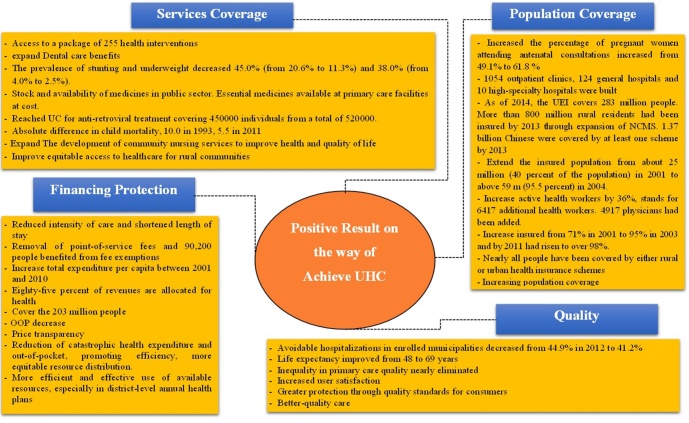

According to the type of successful results gained from interventions in countries in each of the UHC dimension, results were categorized into different items as follows: financial protection (n = 14 items), service coverage (n = 7 items), population coverage (n = 9 items), and quality (n = 7 items) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Achieving positive results on the way to achieving UHC

Discussion

Out of 4257 articles found, finally 57 were included in the study. These articles examined successful interventions in 40 countries on the path to UHC. Most studies were conducted in Asia and the least in Europe.

Results were categorized into different items: financial protection (n = 14 items), service coverage (n = 7 items), population coverage (n = 9 items), and quality (n = 7 items). Most of the interventions were done in LMICs. The results show that most of the interventions in the field of service coverage are targeted specific groups, such as children, adolescents, women, and as specific patients.

The results of the reviewing the time trend of study publication revealed that most studies (except for 2) were published after announcing the UHC as a national and international policy for countries by the WHO in 2008 (3, 65). Also, the time trend of articles publication indicates the importance and great attention of countries to international health-related policies. Considering the many efforts being made in this area, again the high importance of this issue and its repeated mention by the WHO and the commitment of countries to achieve UHC by 2030, demonstrates the feasibility of conducting interventional studies and publication of very important and modeling articles for other countries. Therefore, published articles in this field need to address the performed intervention in more detail so that other countries do not make repeated and costly mistakes when using model countries' experiences (3, 6, 66, 67).

Most of the interventions were done in LMICs and UMICs. Few studies were conducted in high or LICs. One of the possible reasons could be that the HICs are fully achieved UHC and need for no major interventions. In LICs, also, the low interventions could be due to their low income and their inability to finance the structural and basic interventions and to develop major infrastructure. However, evidence suggests that LICs have also taken substantial measures and successful interventions to achieve UHC, given the importance of health and its impact on their economies and sustainable development. However, valuable interventions in countries, such as Nepal (68, 69), Uganda (70, 71), Rwanda (72), Tanzania (56, 73), Ethiopia (74), Afghanistan (75), and Madagascar, (76) have been conducted and positive results have been reported. In addition to published studies in this area, it should be noted that many successful interventions may have taken place before the announcement of this global policy in 2008, which has not been published with the aim of UHC, and these studies are likely to be lost.

Each country, taking into account its own needs and specific circumstances, undertakes specific interventions to achieve UHC. Considering the economic conditions of countries, the results of the present study show that most of the interventions have been performed in the field of financing or financial protection functions. Thus, most interventions in these countries have focused on the insurance system and targeted the poor people or specific groups of society (69, 72, 77-81).

Also, one of the issues that mostly reformed by countries is the payment and premium systems (76, 82-84). Similarly, a study by Elio Borgonovi and Emilia Compagni (2013) indicates that social, economic, and political sustainability are key drivers of health interventions and reforms in achieving UHC (85). Also, in many studies, social health insurance (SHI) (86), premium (50, 51, 87), cost containment (88), national health insurance system (89-91), tax revenue (92, 93), risk-pooling mechanisms (4, 92) and strategic purchasing (94) are crucial factors in the financial protection function of achieving UHC, such that positive reform interventions in these areas can draw countries one step closer to achieving their original goal.

That is why financing function or the financial protec tion dimension and interventions in them can be considered as an essential component of achieving UHC. The results of the study showed that successful interventions in the countries under study have positive results such as reduction in the intensity of care and a decrease in length of hospital stay (82, 95), elimination of costs of services that cause overuse of health services (76), allocating a large percentage of income to health (79), reducing out-of-pocket payments (96), and so on.

The results show that most of the interventions in the field of service coverage are targeted specific groups, such as children, adolescents, women, and specific patients, which could be due to the high vulnerability of women and children under 5 years old and the financial inability of these groups in LMICs. Also, designing dedicated and fully customized service packages can be much more efficient and effective than comprehensive service packages designed for the population of a country without considering the specific needs of different groups. With regard to specific diseases, special conditions, such as chronicity, being erodible, and cost consuming, can lead to catastrophic expenditure; for this reason, people with specific illnesses are covered by free services. Interventions in service coverage show that most interventions are in areas such as modifying or creating service packages based on people's needs at all levels of service provision or for different age groups and specific diseases, and also implementing fundamental interventions in primary health care or community-based health care. Interventions in this area have been in line with the findings of studies that have identified service packages as a major and very effective factor in achieving UHC (15, 88, 97-100).

The study showed that most of the interventions in the field of population coverage were related to the coverage expansion in specific groups or diseases (69, 73, 76, 79, 80, 101-106). Countries are also trying to cover poor households and individuals by implementing mandatory or voluntary insurance programs to cover more population (15, 79, 81, 107, 108). Thailand, for example, with the aim of covering its population considering socioeconomic conditions, by implementing a 30 Bahat health plan, could increase its insured population from 40% to 95% within 4 years, which is also considered one of the most successful interventions in this field (109). China has also been able to cover its entire population by implementing urban and rural health insurance plans (77, 78).

Studying the results of interventions in different countries showed that most of the interventions targeted financial protection and most of the published results also were in this area. This could be due to the importance of financing and reimbursement in the health system and financial protection of citizens against illness, as interventions in this area can reflect an early impact and can be better monitored and evaluated. However, results from the quality dimension are less reported. One of the reasons may be that interventions in this field are new and, on the other hand, the long-term impact of quality improvement interventions can be effective in publishing less studies in this area. Delays in the considering of the quality of health services by the WHO as the fourth dimension could also be another reason for the low publication of quality interventions and their effects on UHC.

The results of the present study show that quality interventions with 18 cases had the least report. However, studies on UHC have identified the quality of care and regulatory mechanisms for quality as one of the most influential factors in achieving UHC (36, 55, 110-112). One of the reasons for low interventions in this dimension could be the overemphasis of countries on the quantity of services provided and coverage of the majority of the population. It can also be attributed to the late introduction of this dimension and its recognition as the hidden dimension of UHC. While implementing programs related to other dimensions of public health coverage, countries need to take into account the quality and its monitoring, so that the interventions can be more efficient and effective. However, given the importance of quality in health, countries have taken important interventions, such as training and using experienced nurses (103), using information technology to reduce medical errors and filling the gap in access to health services (113), maintaining quality of service by licensing qualified individuals and hospitals accreditation (16, 114), and improving patient safety (34). However, the results of interventions in the quality dimension indicate maintaining and enhancing the quality of health care for service receivers through the implementation of quality standards and increasing users' satisfaction with services and eliminating the inequality in accessing quality health services in some countries (84, 115, 116).

One of the limitations of this study was the use of only English and Farsi languages to search and collect studies and documentation based on the authors' familiarity with these 2 languages. However, reports and documentation of successful interventions in countries may have been published and documented in other languages than have not been reviewed in this study. It should be noted that the present study examined only successful interventions that had good and significant results for countries. The reader should note that also some countries on the path to achieving UHC have had unsuccessful and costly interventions that can be used as a model to learn from failures and that only focusing on successful patterns cannot be effective.

Conclusion

Despite the issues raised in achieving UHC and necessity of interventions in the dimensions of UHC, and in light of the results, it should be made clear that in addition to providing the countries with the appropriate technical conditions on this path, the financial resources and political commitment of officials in all disciplines are essential, as the continuity and sustainability of this policy will achieve UHC. The results show that each country, depending on their particular economic, social and political circumstances have selected appropriate intervention mechanisms and tools for achieving UHC and have intervened. Each country has also been able to achieve significant progress in this area by identifying its weaknesses and prioritizing the most important ones for intervention, have achieved remarkable success in this regard, and have taken a step forward. Therefore, lessons learned from successful interventions in these countries can be highly efficient and effective through localizing and combining with target country' features.

Implications for Research and Policy

The present study provides a comprehensive and clear view of successful interventions performed in most countries at different income levels that seek to achieve UHC, and summarizing and reporting these successful interventions can be a model and guide for other countries to avoid the costs and mistakes. The results showed that countries have paid little attention to the quality of services. Therefore, more attention is needed to design and implement comprehensive interventions and policies to improve the quality of services in achieving UHC. Valid interventions with strong methodology and the use of control groups are recommended for future studies. Specific methodological evaluation of interventions is also recommended for future studies.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the experts for their contribution, time, and invaluable comments. Also, we are very grateful to Iran University of Medical Sciences for providing financing support.

Appendix 1.

Characterized of studies included and summarized in the study.

| Author & Year | Country | Dimensions | Health System Function | Innovations / Intervention | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan, W. Y, et al, 2017 (1) | China & Hong Kong |

Services Coverage

Population Coverage Quality |

Stewardship

Services Delivery |

- The Central government of China established CHS centers and subcenters in place in every neighborhood within a 15-minute walking distance to ensure close-to-home primary care.

- Community Nursing Services CHN is improving health care accessibility in China; and the scope of CHN service places much focus on promoting public health - The government provides financial support on the basic public health (BPH) service package, which is determined by the number of citizens using CHN centers’ services. The BPH services are broad and comprehensive, including (a) to establish health profiles and medical records; (b) to provide health education; (c) disease prevention and vaccination; (d) to provide health management for the elderly, pregnant women, children and citizens with hypertension, diabetes or serious mental illness; (e) to control infectious diseases and public health emergencies and (f) to monitor public health. |

- Quality of care is also enhanced because the nurses’ professional knowledge and judgment ensure that the patients are properly assessed, served, and most importantly, referred to the other health care professionals for appropriate care.

- Community-based nursing services present a great opportunity for nurses to enhance their contributions to Universal Health Coverage. - The development of community nursing services has expanded the scope of nursing services to those in need of, not just hospital-level nursing care, but more holistic care to improve health and quality of life. |

| Cheng, S. H. et al, 2012 (2) | Taiwan | Financial Protection | Financing |

- Review of impacts of implementation diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments on health care provider's behavior under a universal coverage system in Taiwan.

- Reforming of payment system |

-The DRG-based payment resulted in reduced intensity of care and shortened length of stay. |

| de Andrade, L. O. et al, 2015 (3) |

Brazil

Chile Colombia Cuba |

Financial Protection

Population Coverage Quality |

Stewardship

Financing Services Delivery |

- Brazil: The conditional cash transfer (family grant) was established in 2003 to ensure access to social rights for health care to provider social rights for health care.

- The program unified several existing programs (School Grant, Food Grant, Food Card, and Gas Grant) and in 2011 became part of the broader government strategy Plan (Plan Brazil without Misery) to raise population income and welfare. The Plan Brazil without Misery targets Brazilian households with per person incomes of less than R$70 (about US$30). The program has three axes: productive, second; access to public services and third, income transfers. - Chile: (Chile Grows with You) is a system of protection for early childhood development, with a mission to monitor, protect, and uphold the rights of all children and their families by providing programs and services, which enable special support for the poorest households that account for most vulnerable families. - Colombia: (From birth to Forever) is the National Strategy for Comprehensive Care in Early Childhood in Colombia. The strategy aims to unify the efforts of the public and private sectors, civil society organizations, and international cooperation to improve the experience and outcomes of early childhood in Colombia. The strategy a community nursery program that provided nutrition and child care for children from poor households. The strategy focuses on strengthening primary health care, including through participatory and social mobilization approaches, with the local authorities playing an important part in supporting progress towards universal health coverage and wider sustainable development objectives. - Cuba: Cuba’s Dengue Prevention Program and Eradication is a comprehensive set of intersectoral interventions aimed at elimination and control of Aedes aegypti mosquito through environmental sanitation, hygiene, and collective household actions. Underpinned by legislation, the program includes the local government, the Ministry of Public Health, community associations, family doctors, water resources management, the antimosquito brigade, and several civil society organizations. - The Dengue Prevention Programme’s grounding at the primary healthcare level, with implementation leadership provided by provincial and municipal governments and participatory approaches to create local level needs assessment and action plans, offers important lessons for intersectoral action for universal health coverage, and sustainable development. |

- Brazil: The Bolsa Família program (family grant) in Brazil is widely regarded as a success. It has lifted millions of people out of poverty, supported people with the greatest unmet need to access health services and has contributed to progressive realization of universal health coverage.

- Between 2002 and 2011, the percentage of pregnant women (in the target population) attending seven or more antenatal consultations increased from49.1% to 61.8%. Inter sectoral action through Bolsa Família has also contributed to improvements in health and action on social determinants. Integration of health and education policies in Bolsa Família expanded access for the poorest groups in Brazil and in 2003–13, contributed to substantial increases in immunization and reduced child mal nutrition, and in 2004–09 to reductions in under-5 mortalities. - Chile: The evidence so far suggests positive effects in reducing child poverty and increasing access to educational opportunities and health. - Colombia: the strategy is a platform to enhance coverage and quality of health care. - Cuba: The program has led to a reduction of dengue infections and improved environmental management for vector control. |

| Edward, A. et al, 2015 (4) | Afghanistan |

Services Coverage

Population Coverage |

Stewardship

Resources Generation Services Delivery |

- Innovative strategies of paired male and female Community Health Workforce CHWs, institution of a special cadre of community health supervisors, and community health councils were introduced as systems strengthening mechanisms.

- CHW: The deployment of volunteer CHWs by the Ministry of Public Health implemented in 2003, to improve equitable access to healthcare for rural communities. One male and one female CHW were selected and trained for each village health post, serving up to 150 households. The CHW job description included treatment of childhood diseases, provision of contraceptives, health promotion, and demand-creation for preventive and maternal health services at the supporting health facility. |

- Formative assessments evidenced that CHWs were highly valued as they provided equitable, accessible and affordable 24h care.

- Improve equitable access to healthcare for rural communities |

| Frenk, J and Gomez-Dantes, O. 2018 (5) | Latin America |

Services Coverage

Population Coverage Financial Protection |

Stewardship

Services Delivery Financing |

- Argentina: Plan name: Plan Nacer -2003 -Non-salaried population with emphasis on women and children-Maternal and child services provided in ambulatory facilities with gradual expansion to surgical services for congenital heart diseases

- Chile: Plan name: Plan de Acceso Universal a Garant IAS Explıcitas (AUGE) 2005, all the population- 80 interventions that cover around 60% of the national burden of disease. - Colombia: Plan name: Plan Obligatorio de Salud (POS) 1993- All the population- Comprehensive health packages that includes essentials and costly interventions - Honduras: Plan name: Plan de Beneficios en Salud (PBS) 2003- Poor, rural population with emphasis on women and Children-Maternal and child ambulatory services, with emphasis in health promotion and preventive interventions. - Mexico: Plans name: Catalogo Universal de Servicios Esenciales de Salud (CAUSES). Fondo de Protecci_on contra Gastos Catastroficos (FPGC). Seguro, 2003 -Non-salaried population- 280 essential interventions provided by ambulatory facilities and general hospitals (CAUSES) and 65 costly interventions provided in specialized hospitals (FPGC). - Peru: Plan name: Plan Esencial de Aseguramiento en Salud or PEAS, 2009 -All the population- 140 essential interventions with emphasis on maternal and child care |

- These programs were the initial reforms in these countries to achieve public health coverage, which hoped to achieve public health coverage because of the progress and positive effects of implementing these reforms in these countries. To achieve this important goal, these countries need experts to implement innovative reforms tailored to the needs of the country. |

| Frenk, J. et al, 2009 (6) | Mexico |

Services Coverage

Financial Protection Population Coverage |

Stewardship

Financing Resources Generation |

- In 2003, the Mexican Congress approved a reform establishing the System of Social Protection in Health, whereby public funding for health is being increased by one percent of the 2003 gross domestic product over seven years to guarantee universal health insurance.

- In the System of Social Protection in Health, funds are allocated into four components: (i) stewardship, information, research and development; (ii) community health services; (iii) non-catastrophic, personal health services; and (iv) high-cost personal health services. - The Seguro Popular is the insurance instrument devised to finance these services under the reform. For financing purposes, personal health services derive from two sources: a package of essential interventions provided in outpatient settings and general hospitals and financed through a fund for personal health services, and a package of highcost, specialized interventions financed through the Fondo de Protección contra Gastos Catastróficos Fund for Protection against Catastrophic Expenditures. - The Seguro Popular will offer coverage to all Mexicans not protected by any other public insurance scheme: the self-employed, those who are out of the labour market and those in the informal sector of the economy. - The Seguro Popular is financed, first, through a social contribution from the federal government. Second, since there is no employer, financial coresponsibility is established between the federal and state governments to generate the so-called federal and state solidarity contributions. The third contribution comes from families and is tied to income, as in the case of social security institutions. |

- In a phase of seven years, this will provide access to formal social insurance, to the 45 million Mexicans who had been excluded from it in the past.

- The new Seguro Popular scheme guarantees access to a package of 255 health interventions targeting more than 90% of the causes leading to service demand in public outpatient units and general hospitals, and a package of 18 costly interventions. - The population with social protection in health increased 20% between 2003 and 2007. - Expenditure for health increased from 4.8% of the GDP in 1990 to 5.6% in 2000 and to 6.5% in 2006. - Public health expenditure as a percentage of total health expenditure increased from 43.8% in 2002 to 46.4% in 2006. - The budget of the MoH increased 72.5% in real terms between 2000 and 2006. - The proportion of the MoH health budget devoted to investment increased from 3.8% in 2000 to 9.1% in 2006, and because of this, the MoH was able to construct 751 outpatient clinics and 104 hospitals, including high-specialty hospitals in the poorest states, between 2001 and 2006. In the public sector as a whole, 1054 outpatient clinics, 124 general hospitals and 10 high-specialty hospitals were built in the same period. |

| Garchitorena, A. et al, 2017 (7) | Madagascar |

Services Coverage

Financial Protection Population Coverage |

Stewardship

Services Delivery Financing |

- A national policy for universal health coverage was signed in December 2015, focused primarily on developing a national health insurance system that pools contributions from taxes, external donor grants, and other sources, to create a prepaid system that reduces fees at the point of service.

- Since 2014 two pilot programs to remove access barriers by providing primary health care services free of charge were implemented in a rural district of Madagascar. - Intervention 1: - The conditions of the Vatovavy-Fitovinany region prompted the World Bank to include it in a project for Emergency Support to Critical Education, Health, and Nutrition Services, implemented in five regions in extreme need across Madagascar. The health component of this project aimed to increase access to health care by providing an essential package of services at no cost for children under age five and pregnant women. The program was implemented in Ifanadiana at all thirteen major health centers but did not cover the districts six other health centers, which were classified as basic health centers. The essential services covered prevention of and treatment for a wide range of conditions. The program was initiated in Ifanadiana in February 2014 and was carried out by local nongovernmental organizations through a voucher system. Every woman attending the health center for antenatal, delivery, or postnatal care (first six weeks) or escorting a child under age five with any illness received a voucher from a program agent. After consultation at the health center, the patient could preset her voucher at the center’s dispensary to receive free medicines prescribed by the center’s Ministry of Health staff. - Intervention 2: - In early 2014 Madagascar’s Ministry of Health also partnered with a nongovernmental organization, PIVOT, to create a model health district for the country based on the WHO’s framework of six building blocks of health system strengthening. Ifanadiana was chosen as the place to test the model health district interventions. This program’s first phase focused primarily on the catchment area of four major health centers, representing approximately one-third of Ifanadiana’s population. In these health centers, supply-side initiatives such as infrastructure renovations and support for different clinical programs have been progressively implemented over the first two years. The most discrete policy change implemented in this area was a program to eliminate point-of-service payments for all patients seeking care at the four targeted health centers. This program, covered costs of forty essential medicines and twenty medical supplies Some additional health system strengthening activities span the entire district, such as hiring medical and non-medical staff at health centers to comply with Ministry of Health policies, training medical staff to improve quality of care, and establishing a referral ambulance network to facilitate access to secondary care. |

- The two programs’ removal of point-of-service fees was associated with health care utilization increases of nearly two-thirds for all patients, more than half for children under age five, and more than 25 percent over two years in maternity consultations.

- Baseline outpatient utilization rates were higher at major health centers than at basic health centers for all patients (relative change: 1.60) and for children under age five (RC: 1.44) but not for maternity care. Each additional health care provider presents in the health center in-creased utilization (RC: 1.09). - The direct costs of the two reimbursement programs were low. In the period from the beginning of each program until December 2015, 90,200 people benefited from fee exemptions in Ifanadiana health centers, with an average cost of US$0.60 per patient. |

| Suneela Garg, 2018 (8) | India |

Services Coverage

Quality |

Stewardship

Services Delivery Resources Generation Financing |

- From medical coverage to achieving holistic health: A paradigm shifts from provision of essential to quality health care at the primary care level. These wellness centers will provide comprehensive healthcare for the management of non-communicable diseases with lifestyle modifications, maternal and child care, adolescent health, nutritional and health education, promotion of menstrual hygiene, and free essential drugs and diagnostic services. Basic dental, ENT and ophthalmology services will also be provided at these centers.

- Primary healthcare with focus on systems beyond medicine: There is a renewed governmental focus on hygiene sanitation, housing, clean indoor air by provision of clean fuels, and expansion of immunization service and coverage. All these initiatives that influence the health of the poor, vulnerable, and under-served population have achieved excellent success in their respective domains. - Focus on protecting maternal health: The Maternal Death Surveillance Response program is geared toward reducing maternal mortality and near misses by improving quality of maternal death reporting with the appropriate capacity building. It involves tracking and identifying the cause of every maternal death at both the facility and the community level and using the information generated for health system strengthening and capacity building for precluding future instances. - Promoting gender equity: There is a welcome and sustained focus on ending female feticide, improving child sex ratio and education of the girl child through the campaign of the government of India called (Save the girl child – Educate the girl child). Promoting menstrual hygiene by the distribution of free of cost menstrual pads, prevention and control of anemia by the distribution of weekly iron‑folic acid tablets in schools, construction of toilets in all schools, scholarships for girls from vulnerable sections of society. - The use of information technology (ICT): for bridging the gap for those lacking access to quality healthcare and reaching the unreached is essential. The various ICT application in healthcare being explored in India include telemedicine, vaccine and drug inventory control and storage, training of health workers, disseminating health education, promotion of behavior change, drug adherence in tuberculosis (TB). - Promotion of generic medicines and cheaper implants to significantly lower out‑of‑pocket costs: The Affordable Medicines and Reliable Implants for Treatment schemes reflect prioritization toward amelioration of routine treatment costs for patients lacking insurance coverage for their outpatient expenses. Strict quality control measures and ubiquitous drug availability and affordability through promotion of entrepreneurial opportunities are the key program drivers. - Public–private partnerships (PPP): Collaborative efforts between private and public sector for improving health service delivery, expansion of coverage, and last mile service delivery have found significant traction in the past two decades. Furthermore, utilizing PPP in critical national health programs such as TB to improve drug adherence and cure rates in patients reaching private sector has received growing impetus. - Strengthening of national programs in TB and HIV‑AIDS |

- The advancement of UHC in India shows a steady evolution.

- Sustainable development regarding universal access to good education, sanitation, clean energy, safe environmental and sound infrastructure which are essential for realizing and maintaining a state of good health is in a state of acceleration. |

| He, A. J and Wu, S. 2017 (9) | China |

Financial Protection

Population Coverage |

Stewardship

Financing |

- The landmark health reform plan announced in 2009. In this health reform expanding the coverage of SHI schemes stands out as one of the five strategic objectives. An additional US$125 billion equivalent to 53 % of the coun-try’s total health expenditures in 2009 has been spent in the first phase of the reform from 2009 to 2011.

- Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance Scheme (UEI): Launched in 1998 after successful pilots in two cities, the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance Scheme (UEI) is the first initiative to fulfill the government’s com-mitment to universal coverage. All urban employees are required to join, by paying 2 % of their payroll income, which is matched by an employer’s contribution of 6 %. The UEI is administered by human resources and social security bureaus at the city level, which have a certain degree of discretion in setting the rate of contribution, deductibles, copayments, reimbursement ceilings, and the methods of collecting premiums as well as paying pro-viders. Upper-level social security authorities exert oversight on the operation of local schemes. - New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) in 2003: As a voluntary insurance program, the NCMS is pooled at the county level and administered by local health bureaus, with vertical supervision from the central and provincial health authorities. The scheme is funded by enrollees’ premiums (about 20 %) and generous subsidies from both central and local governments (about 80 %). In order to avoid adverse selection, enrolment is required at the household level. - Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance Scheme (URI): Introduced in 2007, URI aims to insure students, children, and other unemployed urban residents, who were not previously protected by the UEI. Like the NCMS, the URI was designed as a voluntary program, and requires enrollment at the household level to reduce adverse selection. Similar to the arrangements of the NCMS, the URI is also financed by both individual contribution and govern-ment subsidies, at a 30–70 split. The actual rates of premiums and subsidies largely depend on individuals’ eco-nomic situations and the financial capacity of the local government. Local governments are given autonomy in designing their schemes, and therefore, benefit packages vary across localities. |

- As of 2014, the UEI covers 283 million people.

- With consideration to strong political commitment and administrative mobilization, the NCMS has expanded dramatically in coverage, despite its voluntary nature. More than 800 million rural resi-dents had been insured by 2013. - All SHI schemes have expanded significantly in the past decade: 1.37 billion Chinese were covered by at least one scheme by 2013, an achievement largely attributable to the strong political will of the central leadership, generous government subsidies, and the high mobilization capacity of the country’s admin-istrative machinery. - In parallel with the marked increase in outpatient visits, hospital admissions more than doubled between 2003 and 2011; the effect was most signifi-cant in rural areas. - ** In other words, the reform has not yet made significant progress towards its professed goal of providing affordable care. - ** Moreover, the structural fragmentation of the SHI system has undermined both equity and efficiency of risk pooling; reforms are necessary. - *** Significant disparities exist across the three schemes as well as different regions. As the most generous scheme, the UEI has wider coverage and offers higher benefits than URI and NCMS, thanks to its greater financing capacity. The average UEI premium is ten times higher than those of other schemes. |

| Hongoro, C. et al, 2018 (10) | Uganda | Population Coverage | Stewardship |

- A project entitled “Supporting Policy Engagement for Evidence-based Decisions (SPEED) for Universal Health Coverage (UHC) in Uganda” was launched by the School of Public Health at Makerere University (MakSPH) in 2015. The overall objective of SPEED Project is to strengthen capacity for policy analysis, implementation moni-toring and analysis of impact and thereby contribute to accelerating progress towards UHC in Uganda. The SPEED project seeks to conduct 3 barometer surveys over its 5-year life span (2015–2020).

- Policy Implementation Barometer (PIB) survey which is a mechanism to reveal gaps in policy implementation and thereby provide feedback to the decision makers about the implementation of a selected set of policy programmes for UHC. PIB is proposed as a mechanism to provide feedback to the decision makers about the implementation of a selected set of policy programmes at various implementation levels (macro, meso and micro level). The main objective is to establish the extent of implementation of malaria, family planning and emergency obstetric care policies in Uganda and use these results to support stakeholder engagements for corrective action - The specific objectives of the PIB study are (1) To assess the perceived appropriateness of policy programs im-plemented to address identified policy problems, (2) To assess, using priority parameters, the extent to which the prerequisites for implementation are established, (3) To determine the enablers and constraints to implementation of the selected policies , (4) To compare on-line and face-to-face administration of the PIB questionnaire among target respondents and (5) To document stakeholder responses to PIB findings with regards to policy implementa-tion, awareness and actions. - The main objective is to establish the extent of implementation of malaria, family planning and emergency obstet-ric care policies in Uganda and use these results to support stakeholder engagements for corrective action. |

- UHC objectives for Uganda by ensuring that the selected policy cases for the barometer are relevant to the UHC agenda and government priorities. Ap-plication of an accountability framework such as a policy implementation barometer will foster a sense of responsibility amongst implementers and upstream monitoring will therefore become more effective and hopefully the impact will improve.

- Policies succeed or fail for a variety of reasons and this study seeks to unpack the drivers and bottle-necks in the implementation of specific policies towards UHC in Uganda that is malaria, family planning and emergency obstetric care. These are transnational priority health areas affecting most countries in the sub-region. |

| Hughes D and Lee-thongdee S, 2007 (11) | Thailand | Population Coverage |

Stewardship

Services Delivery |

- The 30 Baht Scheme: is a new public health insurance scheme that provides treatments within a defined benefit package to registered members for a copayment of 30 baht. The 30 Baht Scheme filled the coverage gap left by the existing public health insurance schemes (US$0.80; 0.64 euro; and £0.43) per chargeable episode.

- All members register with a contracting unit and receive a gold card entitling them to care in their home area. Elderly people, children, and poor people receive a special version of the registration card and pay no fee. Drugs prescribed are limited to those on a national list, some high-cost or chronic disease treatments are sub-ject to cost ceilings, and there was initially no entitlement to antiretroviral thera-py or hemodialysis (although these were later brought within the scheme). Treat-ment outside the area of registration is limited to accident and emergency care. Finance for the scheme comes mainly from public revenues paid to local contract-ing units on the basis of population. |

- The 30 Baht Scheme extended the insured population from about twenty-five million (40 percent of the population) in 2001 to above fifty-nine million (95.5 percent) in 2004.

- Although basic coverage was achieved remarkably quick-ly, the 30 baht project required a transformation of the resource allocation system. |

| Kingue, S, et al, 2013 (12) | Cameroon | Population Coverage |

Stewardship

Resources Generation Financing |

- The Cameroonian government developed an HRH emergency plan for the years 2006 to 2008.

- The main strategy for reducing HRH problems in Cameroon is therefore to capital-ize on the existing potential – primarily by improving the coordination and effec-tiveness of the key stakeholders' current efforts to improve the health system. - Between 2007 and 2010, Cameroonian HRH received increased financial support from external sponsors. Over this period, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank – via the Heavily Indebted Poor Country initiative – and the French government – via the Contrat de Désendettement et de Développement – together contributed about 7359 million African Financial Community (CFA) francs to-wards the salaries of health workers in Cameroon. - The HRH emergency plan for 2006–2008 did not solve the maldistribution of HRH in Cameroon, where health care is concentrated in urban areas; the low allo-cation of financial resources for HRH, or the absence of an accreditation system for HRH training. External resources were therefore mobilized to develop new approaches to address these challenges. The mobilization process started in 2007, with a 2-day conference on HRH organized by the Global Health Workforce Alli-ance. This conference resulted in the Douala Plan of Action.4 In 2010 – with fi-nancial support from the World Health Organization (WHO), the Global Health Workforce Alliance, the French Development Agency and the European Union – Cameroon's Ministry of Public Health formally adopted and implemented a “country coordination and facilitation” process. The aims were to clarify the main challenges to effective HRH in Cameroon and to subsequently create an integrated, participatory and comprehensive HRH-development strategy – for the years 2011–2015 – that would address these challenges. |

- the Cameroonian government in response to the HRH crisis, Implementation of this plan led to the recruitment of 5400 health workers, the opening of new training schools for health workers, the revision of the training curricula for paramedical staff, and a simplification of the process that contract or temporary workers need to follow to become permanent employees in the public sector.

-Between 2007 and 2009, the number of active health workers in Cameroon increased by 36% (Implementation of the HRH emergency plan resulted in the recruitment of 6417 additional health workers between 2007 and 2009.), Such recruitment increased the number of active health workers in the country from 11 528 in 2005 to 15 720 in 2009 – a 36% increase. Lessons: -In the improvement of HRH, strong leadership is needed to ensure effective coordination and communication be-tween the many different stakeholders. A national process of coordination and facilitation can produce a consensus-based view of the main HRH challenges. Once these chal-lenges have been identified, the stakeholders can plan appropriate interventions that are coordinated, evidence-based and coherent. |

| Felicia Marie Knaul and Julio Frenk, 2005, (13) | Mexico |

Finance protection

Population Coverage Services Coverage |

Stewardship

Financing Services Delivery |

- System for Social Protection in Health (SSPH):

- The reform was passed into law in April 2003, and the new insurance scheme, called the System for Social Protection in Health (SSPH), went into operation January 2004 with the goal of achieving universal coverage by 2010. The Popular Health Insurance (PHI) is the operational program of the new system. The affiliation process runs from 2004 to 2010, so that 14.3 percent of the approximately eleven million families that make up the uninsured population will be included each year. Preference must be given to families from the lowest income deciles. Reducing out-of-pocket payments tend to be inequitable, unjust, and inefficient a cause and a result of the imbalances discussed above is atarget of the reform. A new public insurance scheme (PHI) was devised to fi-nance personal health services. For funding purposes, personal health services are divided between an essential package of prima-ry- and secondary-level interventions in ambulatory settings and general hospitals, and a package of high-cost tertiary care fi-nanced through the Fund for Protection against Catastrophic Expenditures. - New system of social protection in health that will offer public insurance to all citizens. - The reform has four main objectives: (1) to generate a gradual, predictable, financially sustainable, and fiscally responsible mecha-nism to increase public spending in health so as to correct the existing disequilibria; (2) to stimulate greater allocational efficiency by protecting spending for public health interventions that are cost-effective but tend to be underfunded; (3) to protect families from excessive health spending by offering a collective mechanism that fairly manages the risks associated with paying for person-al health services; and (4) to transform the incentives in the system by moving from supply-side to demand-side subsidies to pro-mote quality, efficiency, and responsiveness to users. - The logic of the reform separates funding between personal and community health services by establishing a separate fund for the latter that is used exclusively to finance public health programs. - The package of essential services is covered by funds administered at the state level, because these services are associated with low risk, high-probability health events. |

- Through a new system of social protection in health that will offer public insurance to all citizens, the reform is expected to reduce cata-strophic and out-of-pocket spending while promoting efficiency, more equitable resource distribution, and better-quality care. |

| Knaul, F. M. et al, 2012, (14) | Mexico |

Finance protec-tion

Quality |

Stewardship

Financing Services Delivery |

- The 2003 reform established a system encompassing all three dimensions—risk, patient, and finance— embedded in the concept of social protection of health. Specifically, public health interventions, institutions and dedicated financing are providing protection against health risks; system-wide initiatives that enhance patient safety, effectiveness, and responsiveness are protecting the quali-ty of health care and Seguro Popular is continually expanding protection against the financial shocks of disease and disability.

- The financial reform was complemented with supply strengthening provisions, including hospital management reform, improved schemes for drug supply, outcome-oriented information systems, a master plan for long-run investment in health infrastructure, and technology assessment. - Innovations to promote protection for patients and against health risks: - Emphasis was also placed on public health through the following instruments: (1) a protected fund for community services; (2) a set of personal health promotion and disease prevention guides (similar to the traditional immunization certificates) with a gender and life course perspective; (3) a comprehensive reorganization of regulatory activities through a new public health agency—the Federal Commission for the Protection against Health Risks (COFEPRIS) charged with safety and efficacy approvals of new drugs and medical devices, food safety regulations, enforcement of environmental and occupational health standards, and control of mar-keting of hazardous substances such as alcohol and tobacco; and (4) major investments in public health to enhance security through epidemiological surveillance and improved preparedness to respond to emergencies, natural disasters, pandemics, and bioterrorism. - To reinforce patient protection, the central program of the managerial reform was the National Crusade for Quality in Health Care. The purpose of this program was to enhance patient safety, improve responsiveness, manage facility accreditation and provider certification, implement quality improvement initiatives, measure technical and interpersonal quality, and undertake performance benchmarking among states and other organizations. - Another important innovation was the creation of the National Center for Health Technology Excellence (CENETEC) in 2004. This Centre produces information and enables an evidence-based approach for investment and use of medical technologies, and coordinates the development of clinical practice guidelines. It has achieved international recognition and is a WHO collaborating center. - Innovations to promote financial protection: - Key to the financial innovations introduced by the SSPH is the separation of funding between personal health services and health-related public goods (including non-personal health services). The separation is designed to protect public health services, which tend to be at risk in reforms that expand insurance. Funds are aggregated over the population without access to social security and divided into four components: (1) stewardship, information, research, and development; (2) community health services; (3) essen-tial personal or clinical health services; and (4) high-cost, catastrophic health interventions. |

- Evidence shows significant progress in reduction of catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishing health expenditure. Catastrophic and impoverishing health-care payments from 1992 to 2010 show a long-run downward trend. In 2000, 3·1% of households had CHE and 3·3% had IHE. By 2010, the values had dropped to 2% for CHE and 0·8% for IHE.

- The differences between households with and without social security are decreasing. The differential share of out-of-pocket spending in house-hold income and CHE fell for all groups between 2004 and 2010, especially for families without so-cial security. IHE fell from 0·2% to 0·1% for households with social security, and from 2·1% to 1·6% for the rest of the population. - Seguro Popular is successfully closing the gaps in health financing across population groups the gap in the per capita allocation of public resources fell more than 70% be-tween 2004 and 2010. |

| Limwattanano et al, 2016 (15) | Thailand |

Finance protection

Population Coverage |

Financing

Stewardship Services Deliv-ery |

- Pre-reform:

- The single largest scheme was a non-contributory Medical Welfare Scheme that entitled the poor, children, the elderly (60+), the disabled and a few other groups to care in public facilities free of charge. This tax-financed scheme covered 32% of the population in 2001. The annual budget per enrollee was just 273 Baht (~$6.82) in 1998 (excluding salary costs). - The second largest programme prior to the reform was a Voluntary Health Card Scheme in which 21% of the population was enrolled in 2001. For 500 Baht ($12.50) per year, households could purchase a health card that entitled up to five house-hold members to free care at public facilities. The private contribution was supplemented by a 1000 Baht tax-financed gov-ernment subsidy. With over four enrollees per card on average, the budget was often insufficient to provide adequate care and, similar to the welfare scheme, there was substantial cross subsidization. - Active and retired government employees and their dependents were and continue to be covered by an entirely tax-financed scheme that provides completely free care at public health facilities. This Civil Servants Medical Benefit Scheme covered 8.5% of the population in 2001. Operating under an uncapped fee-for-service system with a generous benefit package, spending per capita was almost 2500 Baht ($62.50) per enrollee in 1998. - Post-reform: - All Thai citizens not covered by the two employment-based schemes were given entitlement to coverage by the newly instituted, tax-financed Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) that replaced the welfare and voluntary enrollment schemes. Starting in April 2001 with its introduction in six pilot provinces, the scheme was expanded to cover 15 provinces in June 2001 and the remaining provinces by October of that year. - Beneficiaries of the UCS are entitled to inpatient treatment, ambulatory care and prescribed medicines at facilities within a local provider network. The benefit package is near comprehensive. Medicines can be prescribed from a restricted list con-taining a large proportion of generics. - On top of the coverage extension, the main ingredients of the supply side measures were: 1. a closed-end capitation-based budget; 2. gatekeeper control of access to specialist care; 3. prospective payment of hospitals for inpatient treatment; and, 4. a single public purchaser of care and medicines for UCS beneficiaries (from 2006). |

- Pre-reform:

- Ten years before the universal coverage reform in 2001, two-thirds of Thai citizens had no formal health insurance. Expansion of various public health insurance schemes cut this fraction to less than 30% just be-fore the reform. - The second largest programme prior to the reform was a Voluntary Health Card Scheme in which 21% of the population was enrolled in 2001. - Post-reform: - The percentage of the population covered by some form of health insurance jumped from 71% in 2001 to 95% in 2003, and by 2011 coverage had risen to over 98%. - In the post-reform period, such that real total expenditure per capita doubled be-tween 2001 and 2010, and public health expenditure per capita increased by almost 170%. Due to rapid economic growth, total health spending as a share of GDP in-creased by only 0.6 of a percentage point from 2001 to 2010. Household OOP spending held roughly constant in real terms and fell as a percentage of GDP. - The reform had the largest and most signifi-cant impact on household spending on ambulatory care, which was reduced by 38%, on average. |

| Long, S. K. 2008, (16) | Massachusetts USA | Population Coverage |

Stewardship

Financing Services Delivery |

- Massachusetts health reform includes expansions to the Medicaid program (called MassHealth), the creation of a new program that provides income-related subsidies for health insurance (the Commonwealth Care Health Insurance Program, or CommCare), the creation of a new purchasing arrangement (Commonwealth Choice, or CommChoice) via the new Com-monwealth Connector, health insurance market reforms, and requirements that both individuals and employers participate in the health insurance system.

- Key Components of the Massachusetts Health Reform: - Expansion of MassHealth (Medicaid) to children up to 300% of poverty - Expansion of MassHealth Insurance Partnership Program, which provides insurance subsidies and employer tax credits to workers in small firms to 300% of poverty. - Increase in enrollment caps for MassHealth programs for long-term unemployed adults (eligible up to 100% of poverty), disabled working adults (eligible at any income level), and people with HIV (eligible up to 200% of poverty). - Restoration of dental, vision, and other MassHealth benefits to adults. - Creation of new MassHealth wellness benefit/incentive program - Increase in hospital and physician rates under MassHealth. - Creation of CommCare, which provides subsidized insurance for adults up to 300% poverty who are not eligible for MassHealth and do not have access to employer coverage - Creation of Connector Authority, which provides purchasing vehicle for individuals without access to employer coverage and small employers (< 51 employees) via CommChoice. |

- Creation of new Young Adult products for up to 26-year-olds who do not have access to employer coverage

- Extend dependent coverage rules up to age 26 or two years after loss of IRS dependent status, whichever is earlier - Requirement that employers with 11+ employees offer access to Section 125 plan or face potential of a “free-rider sur-charge” if employees use substantial amounts of care through the Health Safety Net Trust Fund. - Requirement that employers must make a “fair and reasonable” contribution toward the cost of health insurance or pay a “fair share” assessment of $295 per employee. - Merger of nongroup and small-group markets - Requirement that all adults age 18 and older have health insurance if it is affordable (“individual mandate”). - Yet another goal of Massachusetts’ health care initiative is to improve access to affordable care both by expanding health insurance coverage and by raising the standard for what counts as insurance. - The uninsurance rate for adults ages 18–64 in Massachusetts dropped by almost half. As a result, in fall 2007, roughly one year after the state’s health reform initiative began; nearly 93 percent of nonelderly adults in the state were insured. - For adults with incomes below 300 percent of poverty (the target population for CommCare), the uninsurance rate dropped by nearly eleven percentage points as a result of health reform, down to about 13 percent in fall 2007. - Dental care benefits were expanded under MassHealth. - There were significant gains in access to care across the overall population under reform, with the gains concentrated among low-income adults. There were very few changes in access to care for higher-income adults, however, the changes that were ob-served suggest that there have been some improvements in access to care for that group as well. |

| Lu, C. et al, 2012 (17) | Rwanda |

Finance protection

Services Coverage |

Financing

Services Delivery Stewardship |

Mutuelles de sante´ (Mutuelles): is a community-based health insurance program established by the Government of Rwanda (GoR) as a key component of the national health strategy on providing universal health care and reaching the health Millen-nium Development Goals (MDGs).

Facing limited resources, the GoR has been implementing Mutuelles since 1999 to provide affordable basic services, espe-cially child and maternal care, to the uninsured population. A pilot program was implemented in three selected districts in 1999 and 2000. To standardize the main parameters of Mutuelles, such as the benefits package, enrollment fees, subsidization mechanisms, organizational structure, management systems, etc., the Mutuelles Health Insurance Policy was approved by the GoR at the end of 2004. Until it was fully implemented in 2006, there was variation and flexibility in scheme design across districts. In 2008, a law on the creation, organization, and management of Mutuelles was enacted, which further strengthened the strategy. Approximately 50 percent of Mutuelles’ funding was comprised of annual member premiums. The remaining half was ob-tained via transfers from other insurance funds, charitable organizations, NGOs, development partners, and the GoR. Providers are paid by Mutuelles directly, either through monthly capitation rates on a fee for-service basis, or performance-based payments. Mutuelles uses a policy of household subscription. Enrolled households are affiliated to designated health centers. With referrals from the health center, members may obtain hospital services covered by Mutuelles. To mitigate adverse selection, enrollees must wait one month to utilize covered services. |

To date, Rwanda is the only country in sub-Saharan Africa where more than 90% of the population is covered by community based health programs.

The evidence suggests that at the individual level, Mutuelles improved medical care utilization among the general population, under-five children, and women with child delivery. At the household level, Mutuelles protected households from catastrophic health spend-ing. At the provincial level, was existans a positive effect of Mutuelles coverage on child and maternal care coverage. At the national level, observed an increase in medical care coverage accompanied by a decrease in OOPS and percentage of households with catastrophic health spending. It seems plausible that the increase in medical care coverage contributed to major improvements in child mortality and maternal mortality during the same period. Currently, Rwanda is one of the few African countries that stand a chance of reaching the targets of health MDGs. *The positive results of the Mutuelles program in promoting medical care utilization and financial risk protection suggests that the community-based health insurance scheme can be an effective tool for achieving universal health coverage, together with other policy instruments. |

| Lu, J. F. R. and Chiang, T. L. 2018, (18) | Taiwan | Population Coverage Quality | Rescuers Generation |

Four key strategies adopted in the health service sector development Taiwan:

1) Enhancing public-private partnerships in developing medical resources with tax incentives and subsidies: Taiwan was able to exploit the economic resources to inculcate its health workforce and facilitate capacities building and has applied a combination of macro-controls and market forces to the health resource management at different levels of economic devel-opment. Once the economy started to boom, the government exerted efforts in engaging private investment and devise appro-priate policy to ameliorate distribution imbalance. Public-private partnership is one key to the success of service sector development, but the expansion of private sector cannot be left completely unregulated. 2) Ameliorating regional disparities in medical resource distribution through incentives and effective regulation: Taiwan’s government took multifaceted actions to successfully tackle the issues of supply shortage as well as maldistribution of physicians and hospital beds. Important throughout were the use of economic incentives, public-private partnerships, while government regulation also played a crucial role in stabilizing market supply and the geographic distribution of healthcare providers. 3) Safeguarding quality of care by regulating providers through licensing and accreditation programs. 4) Promoting an evidence-based policy-making process. The efforts exerted by the government, with the private sector partnerships, in AAAQ framework are described as below: Availability: Strengthen, plan and support the cultivation of health workforce through founding 4 public medical schools and subsidizing 8 private medical schools. Provide financial incentives (tax advantages and interest-free grants) to build up hospital capacities. Accessibility: Reduce inequality in workforce distribution through incentives (interest-free grants for hospital building projects in the non-metropolitan area and Group Practice Centers) and regulatory (constraints on the expansion of large private hospitals in resource-saturated metropolitan areas) approaches delineated in the Medical Care Network planning program. Acceptability: Reinforce the regulation of medical practices through 1975 New Physicians Act and 1986 Medical Care Act, which cracked down the practices of those who did not receive formal medical education and enforced the requirement of two-year resident training program and specialist licensing to meet public expectation. Quality: Safeguard hospital service quality, a nationwide all-hospital accreditation program was implemented in 1987. |

The key to its success in providing effective coverage to its 23 million populations was the readiness of the health service sector.

Taiwan’s experiences in service sector development manifest the importance of economics resources and political leadership. |

| Maluka, S. et al, 2018 (19) | Tanzania | Services Coverage |

Services Delivery

Stewardship |

Design and implementation of Service Agreement (SAs) between local governments and non-state providers) NSPs) for the provision of primary health care services.