Abstract

Background and objectives

Patient self-rating based scales such as Numerical Rating Scale, Visual Analog Scale that is used for postoperative pain assessment may be problematic in geriatric or critically ill patients with communication problems. A method capable of the assessment of pain in objective manner has been searched for years. Analgesia nociception index, which is based on electrocardiographic data reflecting parasympathetic activity, has been proposed for this. In this study we aimed to investigate the effectiveness of analgesia nociception index as a tool for acute postoperative pain assessment. Our hypothesis was that analgesia nociception index may have good correlation with Numerical Rating Scale values.

Methods

A total of 120 patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I and II undergoing any surgical procedure under halogenated-based anesthesia with fentanyl or remifentanil were enrolled for the study. At the 15th minute of arrival to the Postoperative Care Unit the patients’ pain was rated on a 0–10 point Numerical Rating Scale. The patients’ heart rate, blood pressure, and analgesia nociception index scores were simultaneously measured at that time. The correlation between analgesia nociception index, heart rate, blood pressure and Numerical Rating Scale was examined.

Results

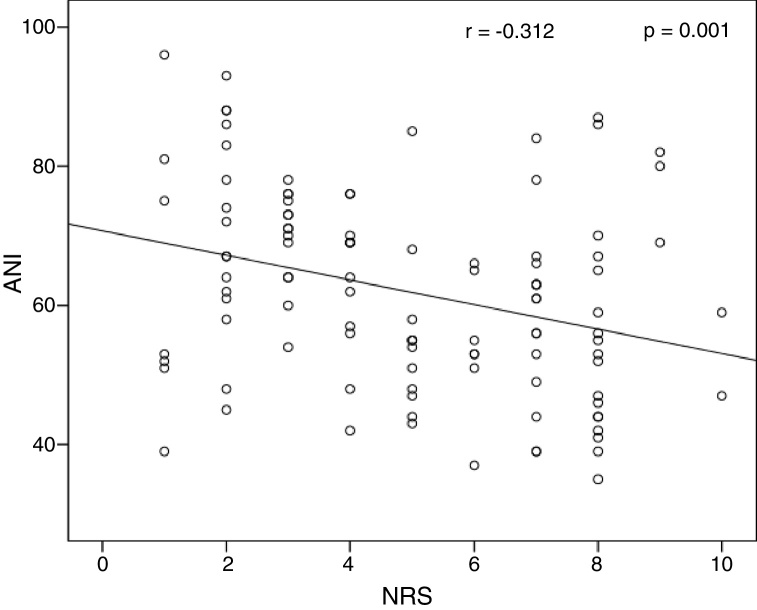

The study was completed with 107 patients, of which 46 were males (43%). Mean (SD) analgesia nociception index values were significantly higher in patients with initial Numerical Rating Scale ≤3, compared with Numerical Rating Scale >3 (69.1 [13.4] vs. 58.1 [12.9] respectively, p < 0.001). A significant negative linear relationship (r2 = −0.312, p = 0.001) was observed between analgesia nociception index and Numerical Rating Scale.

Conclusion

Analgesia nociception index measurements at postoperative period after volatile agent and opioid-based anesthesia correlate well with subjective Numerical Rating Scale scores.

Keywords: Analgesia/nociception index, Postoperative pain, Pain assessment

Resumo

Justificativa e objetivo

As escalas baseadas na autoavaliação de pacientes, como a Escala Visual Numérica e a Escala Visual Analógica, que são usadas para avaliar a dor pós-operatória podem ser problemáticas em pacientes geriátricos ou em estado crítico com problemas de comunicação. Portanto, um método capaz de avaliar a dor de maneira objetiva vem sendo pesquisado há anos. O índice de analgesia/nocicepção, baseado em dados eletrocardiográficos que refletem a atividade parassimpática, tem sido proposto para tal avaliação. Neste estudo, objetivamos investigar a eficácia do índice de analgesia/nocicepção como uma ferramenta para a avaliação da dor pós-operatória aguda. Nossa hipótese foi que o índice de analgesia/nocicepção pode ter boa correlação com os valores da Escala de Classificação Numérica.

Métodos

Um total de 120 pacientes com estado físico ASA I e II, submetidos a qualquer procedimento cirúrgico com o uso de anestésicos halogenados associados a fentanil ou remifentanil, foi incluído no estudo. No 15° minuto após a chegada à sala de recuperação pós-anestesia, a dor dos pacientes foi avaliada em uma escala numérica de 0–10 pontos. Os escores de frequência cardíaca, pressão arterial e o índice de analgesia/nocicepção dos pacientes foram medidos simultaneamente naquele momento. A correlação entre o índice de analgesia/nocicepção, frequência cardíaca, pressão arterial e a Escala Visual Numérica foi avaliada.

Resultados

O estudo foi concluído com 107 pacientes, dos quais 46 eram do sexo masculino (43%). Os valores da média (DP) do índice de analgesia/nocicepção foram significativamente maiores nos pacientes com valor inicial na Escala Visual Numérica ≤ 3, em comparação com valor na mesma escala >3 (69,1 [13,4] vs. 58,1 [12,9], respectivamente, p < 0,001). Uma relação linear negativa significativa (r2 = -0,312, p = 0,001) foi observada entre o índice de analgesia/nocicepção e a Escala Visual Numérica.

Conclusão

As mensurações do índice de analgesia/nocicepção no pós-operatório após anestesia com agentes halogenados e opioides mostraram boa correlação com os escores subjetivos da Escala Visual Numérica.

Palavras-chave: Índice de analgesia/nocicepção, Dor pós-operatória, Avaliação da dor

Introduction

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines the pain as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage. The term “emotional” in the definition makes the pain a subjective experience, so patient self-rating based scales such as Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Wong-Baker FACES scale are used for postoperative pain assessment. However, these scales are problematic in pediatric, geriatric or critically ill patients, in patients with communication problems and those on sedation. Postoperative delirium may also be confounding. For these reasons, a method capable of the assessment of pain in objective manner has been searched for years.

In the past, conventional indices of pain like heart rate and blood pressure were used to predict the pain. But these indices have been questioned, because of the multiple interactions between autonomic, nervous and cardiovascular systems. More sophisticated indices, such as skin conductance, surgical pleth index and pupillary reflex dilatation have been investigated and shown correlation with acute pain; however again not being sufficiently accurate to recommend their routine use in clinical practice.1, 2, 3, 4, 5

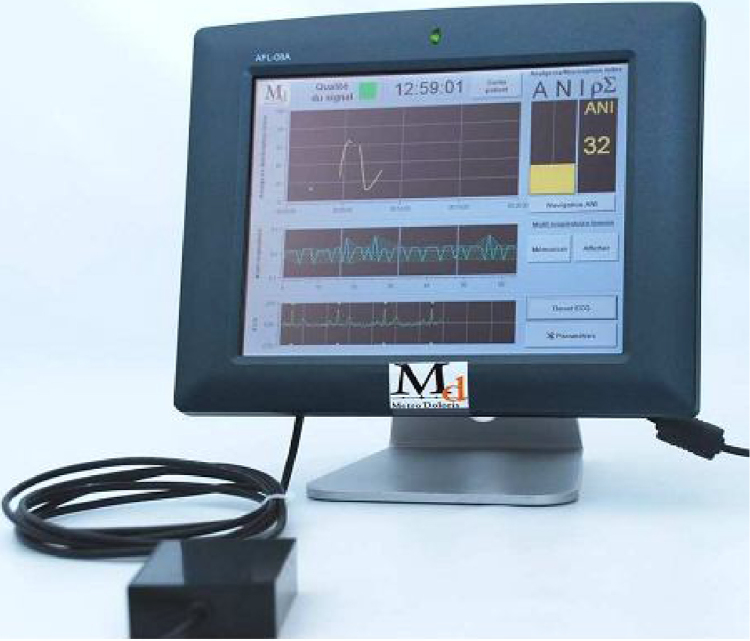

Most recently, an Analgesia Nociception Index (ANI) (Metrodoloris, Lille, France) has been proposed for the assessment of acute nociception and pain. ANI is based on Electrocardiographic (ECG) data obtained by two electrodes placed on the patient's chest. ANI is computed from a frequency domain-based analysis of the High Frequency (HF) component (HF: 0.15–0.5 Hz) of Heart Rate Variability (HRV), also taking into account the Respiration Rate (RR) as a potential confounder. It is displayed as a score from 0 to 100, reflecting parasympathetic activity, i.e. lower values meaning low, and higher values meaning high parasympathetic activity. Pain itself results in the predominance of sympathetic activity, so the ANI values decrease with pain. Fig. 1 demonstrates ANI monitor.

Figure 1.

Physiodoloris monitor. Lower scope: ECG signal. Middle scope: normalized, mean centered and band pass filtered RR series. Upper scope: ANI trend curve.

Although ANI was introduced mostly for intraoperative pain assessment, its use in Postanesthesia Care Unit (PACU) was investigated and resulted in good correlation with subjective measures of pain.6, 7, 8

In this study we aimed to investigate the performance and effectiveness of ANI as a tool for acute postoperative pain assessment in PACU. Our hypothesis was that ANI may have good correlation with NRS values, even with the use of the drugs affecting autonomic nervous system.

Methods

This prospective observational study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Malatya Clinical Research Ethics Committee, 2014/191, 03.12.2014) and performed between January and March 2017 at Adiyaman University Educational and Research Hospital. The study was supported by Adiyaman University Scientific Research Project Unit (TIPFMAP/2015-0012). STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) recommendations were followed. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients before the operation. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I and II patients undergoing any surgical procedure under halogenated-based anesthesia with fentanyl or remifentanil were enrolled for the study. The exclusion criteria were age <18 and >65 years, arrhythmia, preoperative β-blocker use, psychiatric diseases, autonomic nervous system disorders, epilepsy, and inability to cooperate or understand the numerical rating scale.

At the 15th minute of arrival to the PACU the patients were asked to rate their pain on a 0–10 point NRS. The evaluated pain was resting pain, and the evaluation was done by an anesthesia specialist attending the operation. The patients were asked about their pain arising from the operated area and its severity based on the description of NRS made preoperatively. The patients’ Heart Rate (HR), Blood Pressure (BP), and ANI scores were simultaneously measured at that time by an another observer. The anesthetist measuring the NRS's was blind to the ANI scores.

The patients’ HR and BP values were measured in the PACU by an automated system via monitors used for routine postoperative follow-up (KMA 800, Petaş®, Ankara, Turkey). NRS was measured via independent observer, blinded to the study. The patients were acknowledged preoperatively about the NRS, knowing that “10” points stood for the worst perceivable pain, and “0” points signified no pain at all.

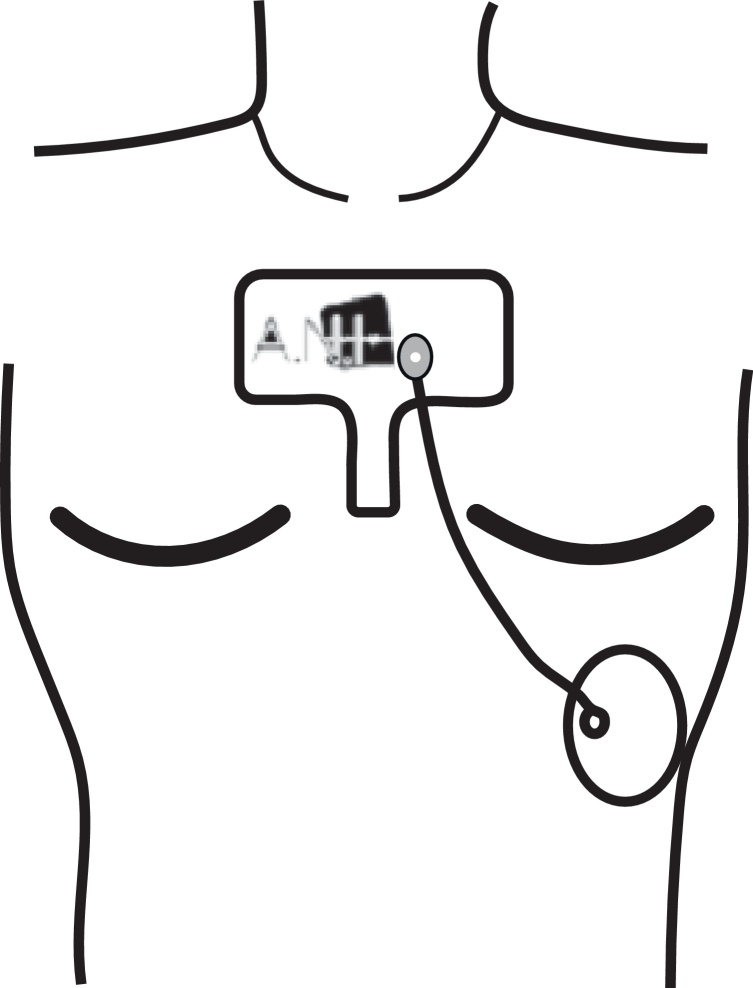

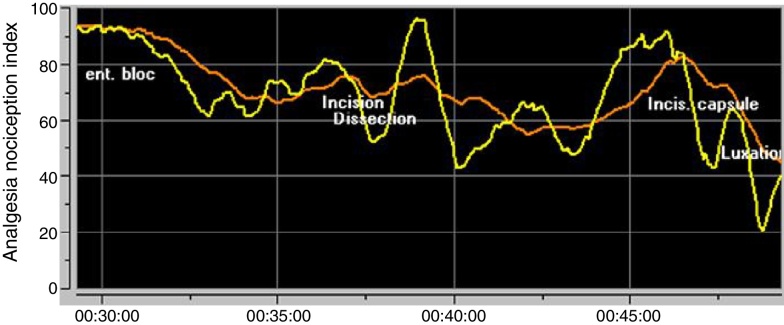

ANI values were measured by Physiodoloris® monitor (Metrodoloris®, Lille, France) using two ECG electrodes placed on the patient's chest at upper part of the sternum and at the standard electrocardiographic V5 point (Fig. 2). The monitor displays two values for ANI. First one is the instantaneous ANI value, which is displayed in yellow color, the second is ANI value averaged over 4 min, displayed in orange (Fig. 3). The instantaneous ANI was used for recordings, i.e. the yellow one.

Figure 2.

ANI electrode position.

Figure 3.

ANI parameters. Yellow, instantaneous ANI; orange, ANI averaged over 4 minutes.

A power analysis were performed by G*Power software to determine the appropriate sample size required for the study. The sample size calculation was based on pilot study, an alpha error of 0.05 and a power of 80% (based on an estimated ANI standard deviation of 12). This gave a required total sample size of 93. In order to allow for potential drop outs and missing data, 120 patients were recruited. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 15.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were presented as a mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables were presented as percentages. Normal distribution was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test or Shaphiro–Wilk test. Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared using the Independent samples t-test for two groups (NRS ≤ 3 and NRS > 3) and One Way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test for three groups (NRS score 1–3, 4–5 and 6–10). Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient was used to explore the associations between ANI and other variables. A p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 120 patients were enrolled for the study. Seven patients had technical difficulties with the ANI monitoring, and the data of 6 patients have been lost, so the study was completed with 107 patients, of which 46 were males (43%). Table 1 demonstrates the patients’ characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study patients.

| Variables | NRS ≤ 3 (n = 37, 34.6%) |

NRS > 3 (n = 70, 65.4%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | 0.001a | ||

| Male | 24 (52.2) | 22 (47.8) | |

| Female | 13 (21.3) | 48 (78.7) | |

| ASA class, n (%) | 0.679 | ||

| I | 19 (36.5) | 33 (63.5) | |

| II | 18 (32.7) | 37 (67.3) | |

| Age (years) | 35.5 (15.6) | 39.3 (14.0) | 0.200 |

| BMI (kg. m−2) | 25.9 (4.8) | 27.7 (6.7) | 0.145 |

| ANI | 69.1 (13.4) | 58.1 (12.9) | <0.001a |

| SAP (mm Hg) | 126.9 (14.2) | 132.5 (14.6) | 0.063 |

| DAP (mm Hg) | 72.0 (8.5) | 75.3 (9.7) | 0.083 |

| HR (beats/min) | 76.7 (15.5) | 78.0 (12.9) | 0.642 |

Values are given as mean (SD), or n (%). BMI, body mass index; ANI, analgesia/nociception index; SAP, systolic arterial pressure; DAP, diastolic arterial pressure; HR, heart rate.

p < 0.05.

Considering pain evaluation, 37 patients (34.6%) had mild pain (NRS ≤ 3), whereas 70 (65.4%) had moderate to severe pain (NRS > 3). About half of the male patients had moderate to severe pain (NRS > 3), whereas this ratio was almost 80% for females, and this difference between genders was statistically significant. No significant difference was detected between the groups with NRS ≤ 3 and NRS > 3 as regards the ASA physical status, age, and BMI (Table 1).

Mean (SD) ANI values were significantly higher in patients with initial NRS ≤ 3, compared with NRS > 3 (69.1 [13.4] vs. 58.1 [12.9] respectively, p < 0.001). The differences between the groups with NRS ≤ 3 and NRS > 3 as regards systolic and diastolic arterial pressures, and the heart rate were not statistically significant.

Table 2 shows the association between ANI and NRS. Lower ANI scores were found in “severe” vs. “mild” and “moderate” vs. “mild” groups defined by NRS.

Table 2.

Association between ANI and NRS.

| NRS | n | ANI | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | 37 | 69.1 (13.4)a | 64.58–3.52 |

| 4–5 | 24 | 59.2 (11.6)b | 54.31–64.11 |

| 6–10 | 46 | 57.5 (13.6)b | 53.49–61.59 |

NRS, numerical rating scale; ANI, analgesia/nociception index. ANI is presented as mean (SD). The different letters in each column indicate significant differences between the groups (p < 0.05).

Table 3 shows the correlation between ANI and other parameters. The only significant correlation was found between ANI and NRS. A significant negative linear relationship (r2 = −0.312, p = 0.001) was observed between ANI and NRS (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Correlations between ANI and other parameters.

| Parameters | Correlation coefficient | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.001 | 0.995 |

| BMI | 0.103 | 0.293 |

| NRS | −0.312 | 0.001 |

| SAP | 0.019 | 0.845 |

| DAP | −0.076 | 0.434 |

| HR | −0.023 | 0.816 |

BMI, body mass index; ANI, analgesia/nociception index; SAP, systolic arterial pressure; DAP, diastolic arterial pressure; HR, heart rate.

Figure 4.

Correlations between ANI and NRS score.

Discussion

The main finding of the study was that ANI scores were negatively correlated with NRS. NRS represents the subjective component of the pain, and values ≤3 indicate mild pain, whereas values > 3 stand for moderate to severe pain. ANI represents the objective component of pain, and as it shows the parasympathetic activity in numbers, lower values stand for pain. A negative linear relationship between ANI and NRS was found in our study, which meant lower ANI scores with higher NRS values (i.e., pain). NRS score 3 was taken as a threshold for comparison of ANI scores, because this is the value intolerable to most of the patients, and this value is also used as a threshold for interventions to alleviate pain.

Ledowski et al.6 have found a weak correlation between ANI and NRS after general anesthesia, and linked this phenomenon to the effect of anesthetic drugs and sedation in PACU, which may have influenced ANI. Le Guen et al. have studied the correlation between ANI and VAS in laboring parturients, and found significant negative linear relationship. The patients in this study were naturally conscious.9 Ledowski et al.10 have also stated that recovery from sevoflurane based anesthesia may be associated with higher sympathetic activity compared with recovery after Total Intravenous Anesthesia (TIVA) with propofol, and this may also influence ANI. Many other factors other than anesthetic drugs also affect sympathetic activity. Some of them are arousal, anxiety, agitation, and noise, which are commonly encountered in PACU. They increase sympathetic activity and so affect ANI scores. These examples of confounders have previously been described, and suspected to impair the accuracy of monitors of pain as skin conductance or surgical stress index.11, 12 The relationship between acute postoperative pain and autonomic stress response may be far less linear, which reduces the performance of any pain monitor based solely on the assessment of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity.

ANI has been shown to correlate with hemodynamic stress response13 and predict treatment success for tourniquet-related hypertension.14 ANI has been found to be more reactive than skin conductance for prediction of intraoperative pain in children.1 All these studies have been performed under general anesthesia, and ANI may perform better under general anesthesia, where other abovementioned confounders of autonomic nervous system are reduced or eliminated.

Severe postoperative pain is associated with delayed postoperative ambulation, increased hemodynamic reactivity, increased pulmonary complications, decreased patient satisfaction, development of chronic postoperative pain, increased PACU length of stay, and increased patient morbidity and mortality. Optimal analgesic strategies are therefore of great importance.15, 16 Current ASA guidelines recommend using standardized, validated instruments for regular evaluation and documentation of pain intensity, the effects of analgesic therapy, and side-effects of the therapy. Undertreatment of pain in elderly is widespread, and it is recommended that pain assessment and therapy should be integrated in the perioperative care of geriatric patients. Moreover, pain assessment tools should be adapted to patients’ cognitive abilities.16 Treatment of acute postoperative pain continues to be a major challenge.

Pupillary reflex measurement has been reported as an objective assessment of acute postoperative pain.17 Migeon et al.3 have compared this reflex with ANI, and found a good correlation. Herein non-invasive nature of ANI makes it a better tool. ANI was compared with VAS (0–100 mm) in study enrolling orthopedic surgery patients, and a good correlation was detected between ANI and VAS both during painless and painful periods.18

More recently, ANI was used as a tool for prediction of antinociception/nociception balance in the patients undergoing laparoscopic abdominal surgery.13 Anesthesia induction decreased HR and SAP, and increased ANI, which indicated parasympathetic predominance. After start of surgery and pneumoperitoneum ANI values decreased, but no significant changes in HR and SAP were detected. Although the difference in ANI were significant between patients with NRS ≤ 3 and NRS > 3 in our study, no significant difference was observed between the groups as regards HR, SAP and DAP. These results are in concordance with the previous studies, and support the phenomenon that hemodynamic variables are far less insufficient as a prediction tool for pain.

Boselli et al. have demonstrated a negative linear relationship between ANI measured at arousal from general anesthesia and immediate postoperative pain measured by NRS.8 In this study ANI scores < 50 have corresponded to moderate-to-severe pain (NRS > 3). This threshold was 57 in the study of Boselli et al. enrolling ear-nose-throat surgery patients.7 In our study we have demonstrated mean ANI scores of 59 and 57 for moderate and severe pain, respectively. The different threshold values may be explained by different opioid preferences, volatile-based vs. intravenous only-based anesthesia, different surgical procedures, and perioperative use of drugs that have influence on autonomic nervous system. So, we recommend the standardization of other parameters (i.e., anesthetic drugs, homogenous surgical population) when performing studies in this domain. Moreover, Boselli et al.8 have made their measurements at arousal from general anesthesia, just immediately before extubation. This avoids the effect of stress and anxiety, and ANI measurements are theoretically affected mainly by pain. So, ANI measurements performed just before extubation may be more reliable than the measurements performed in PACU. We have made our measurements at 15th minute after arrival to PACU, naturally under the effect of abovementioned confounders. Another difference in our study was that we have not excluded the patients receiving neostigmine and atropine for the reversal of neuromuscular blockade. We routinely use reversal of neuromuscular blockade after elective surgeries, where the patients are extubated at the end of the procedure. At special circumstances we use sugammadex for the reversal. It might have been wise to use sugammadex for all the patients to avoid the interference of atropine and neostigmine combination with autonomic nervous system, but this was not done because of the financial reasons, nor was this approved by the ethics committee. The minimum time interval between the reversal agent combination and ANI measurement was ensured.

Significant difference was detected between males and females. Four out of 5 females had experienced moderate-to-severe pain in PACU. Moderate-to-severe immediate postoperative pain was observed in 65% of the patients. This ratio was 35% in the study of Boselli et al.8 Although the genetic factors might have been contributory, this difference probably reflects the institutional local treatment protocols and approach to postoperative pain.

Some limitations of the study were noted. First, as mentioned above, the possible effect of atropine and neostigmine combination on the autonomic nervous system could not have been avoided. But, this was performed to all the patients routinely, and time interval of 20 min was provided before the ANI measurement. Boselli et al.8 have stated that their results may not be extrapolable to patients receiving anticholinesterase for reversal. We have included these patients in our study, and the results may be interpreted as preliminary in this context. Second, we have used fentanyl or remifentanil as opioids to support general anesthesia, but these opioids might have had different effects on heart rate variability.19, 20 Standardization of the opioid agent would have been wise. Third, ASA status I–II patients were selected for the study, so the results cannot be extrapolated to patients with higher ASA status, which commonly represents a great portion in daily clinical practice. Last, standardization of the surgical population would be also wise, as some surgery types are naturally known to result in more algesia.

In conclusion, ANI measurements at postoperative period after volatile agent and opioid-based anesthesia correlate well with subjective NRS scores of the patients. Whether this correlation has clinical significance needs to be studied. ANI measurement in PACU is a simple and non-invasive method in predicting moderate-to-severe acute postoperative pain, and guiding analgesic interventions.

Funding

The study was supported by Adiyaman University Scientific Research Project Unit (TIPFMAP/2015-0012).

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the Anesteshesiology and Reanimation residents of Adiyaman Educational and Research Hospital for their valuable contribution in the data acgusition process for the study.

References

- 1.Sabourdin N., Arnaout M., Louvet N., et al. Pain monitoring in anesthetized children: first assessment of skin conductance and analgesia-nociception index at different infusion rates of remifentanil. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23:149–155. doi: 10.1111/pan.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gruenewald M., Herz J., Schoenherr T., et al. Measurement of the Nociceptive Balance by Analgesia Nociception Index (ANI) and Surgical Pleth Index (SPI) during Sevoflurane – Remifentanil Anaesthesia. Minerva Anestesiol. 2015;81:480–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Migeon A., Desgranges F.P., Chassard D., et al. Pupillary reflex dilatation and analgesia nociception index monitoring to assess the effectiveness of regional anesthesia in children anesthetised with sevoflurane. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23:1160–1165. doi: 10.1111/pan.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ledowski T., Bromilow J., Paech M.J., et al. Monitoring of skin conductance to assess postoperative pain intensity. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:862–865. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ledowski T., Pascoe E., Ang B., et al. Monitoring of intra-operative nociception: skin conductance and surgical stress index versus stress hormone plasma levels. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:1001–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledowski T., Tiong W.S., Lee C., et al. Analgesia nociception index: evaluation as a new parameter for acute postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:627–629. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boselli E., Daniela-Ionescu M., Bégou G., et al. Prospective observational study of the non-invasive assessment of immediate postoperative pain using the analgesia/nociception index (ANI) Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:453–459. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boselli E., Bouvet L., Bégou G., et al. Prediction of immediate postoperative pain using the analgesia/nociception index: a prospective observational study. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:715–721. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Guen M., Jeanne M., Sievert K., et al. The analgesia nociception index: a pilot study to evaluation of a new pain parameter during labor. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ledowski T., Bein B., Hanss R., et al. Neuroendocrine stress response and heart rate variability: a comparison of total intravenous versus balanced anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1700–1705. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000184041.32175.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ledowski T., Ang B., Schmarbeck T., et al. Monitoring of sympathetic tone to assess postoperative pain: skin conductance vs. surgical stress index. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:727–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilies C., Gruenewald M., Ludwigs J., et al. Evaluation of the surgical stress index during spinal and general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:533–537. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeanne M., Clement C., De Jonckheere J., et al. Variations of the analgesia nociception index during general anaesthesia for laparoscopic abdominal surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2012;26:289–294. doi: 10.1007/s10877-012-9354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Logier R., De Jonckheere J., Delecroix M., et al. Heart rate variability analysis for arterial hypertension etiological diagnosis during surgical procedures under tourniquet. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2011;2011:3776–3779. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2011.6090645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerbershagen H.J., Aduckathil S., van Wijck A.J., et al. Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: a prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:934–944. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31828866b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:248–273. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aissou M., Snauwaert A., Dupuis C., et al. Objective assessment of the immediate postoperative analgesia using pupillary reflex measurement: a prospective and observational study. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1006–1012. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318251d1fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logier R., Jeanne M., De Jonckheere J., et al. PhysioDoloris: a monitoring device for analgesia/nociception balance evaluation using heart rate variability analysis. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2010;2010:1194–1197. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2010.5625971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galletly D.C., Westenberg A.M., Robinson B.J., et al. Effect of halothane, isoflurane and fentanyl on spectral components of heart rate variability. Br J Anaesth. 1994;72:177–180. doi: 10.1093/bja/72.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latson T.W., McCarroll S.M., Mirhej M.A., et al. Effects of three anesthetic induction techniques on heart rate variability. J Clin Anesth. 1992;4:265–276. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(92)90127-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]