Abstract

Background

Hypothermia occurs in up to 20% of perioperative patients. Systematic postoperative temperature monitoring is not a standard of care in Brazil and there are few publications about temperature recovery in the postoperative care unit.

Design and setting

Multicenter, observational, cross-sectional study, at Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal and Hospital Materno Infantil de Brasília.

Methods

At admission and discharge from postoperative care unit, patients undergoing elective or urgent surgical procedures were evaluated according to tympanic temperature, vital signs, perioperative adverse events, and length of stay in postoperative care unit and length of hospital stay.

Results

78 patients, from 18 to 85 years old, were assessed. The incidence of temperatures <36 °C at postoperative care unit admission was 69.2%. Spinal anesthesia (p < 0.0001), cesarean section (p = 0.03), and patients who received morphine (p = 0.005) and sufentanil (p = 0.003) had significantly lower temperatures through time. During postoperative care unit stay, the elderly presented a greater tendency to hypothermia and lower recovery ability from this condition when compared to young patients (p < 0.001). Combined anesthesia was also associated to higher rates of hypothermia, followed by regional and general anesthesia alone (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this pilot study showed that perioperative hypothermia is still a prevalent problem in our anesthetic practice. More than half of the analyzed patients presented hypothermia through postoperative care unit admission. We have demonstrated the feasibility of a large, multicenter, cross-sectional study of postoperative hypothermia in the post-anesthetic care unit.

Keywords: Body temperature, Hypothermia, Anesthesia, Postoperative care

Resumo

Justificativa

A hipotermia ocorre em até 20% dos pacientes no perioperatório. A monitorização sistemática pós-operatória da temperatura não é um padrão de atendimento no Brasil e há poucas publicações sobre recuperação da temperatura na sala de recuperação pós-anestésica.

Desenho e cenário

Estudo multicêntrico, observacional, transversal, conduzido no Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal e no Hospital Materno Infantil de Brasília.

Métodos

Na admissão e alta da sala de recuperação pós-anestesia, os pacientes submetidos a procedimentos cirúrgicos eletivos ou de urgência foram avaliados de acordo com a temperatura timpânica, sinais vitais, eventos adversos perioperatórios, tempo de permanência na sala de recuperação pós-anestesia e tempo de internação hospitalar.

Resultados

Setenta e oito pacientes com idades entre 18 e 85 anos foram avaliados. A incidência de temperatura <36 °C na admissão à sala de recuperação pós-anestesia foi de 69,2%. Raquianestesia (p < 0,0001), cesariana (p = 0,03) e os pacientes que receberam morfina (p = 0,005) e sufentanil (p = 0,003) apresentaram temperaturas significativamente menores ao longo do tempo. Durante a permanência na sala de recuperação pós-anestesia, os pacientes idosos apresentaram uma tendência maior a apresentarem hipotermia e menor capacidade de recuperação dessa condição, em comparação com os pacientes jovens (p < 0,001). Anestesia combinada também foi associada a taxas mais altas de hipotermia, seguida pelas anestesias regional e geral isoladas (p < 0,001).

Conclusão

Em conclusão, este estudo piloto mostrou que a hipotermia perioperatória ainda é um problema prevalente em nossa prática anestésica. Mais de metade dos pacientes analisados apresentaram hipotermia durante a admissão à sala de recuperação pós-anestésica. Demonstramos a viabilidade de um grande estudo multicêntrico, transversal, de hipotermia pós-operatória em sala de recuperação pós-anestésica.

Palavras-chave: Temperatura corporal, Hipotermia, Anestesia, Cuidados pós-operatórios

Introduction

The human thermoregulating system allows for variations around 37 °C to maintain metabolic functions.1 Autonomic thermoregulatory responses are triggered so as to maintain the body temperature at an approximate constant value. Anesthetic induction decreases metabolic heat production and mitigates the physiological thermoregulatory responses.2, 3 Most anesthetics change core temperature control, inhibiting thermoregulatory responses against the cold, such as vasoconstriction and muscle tremors. Besides, most of these drugs have a vasodilating effect, considered to be the responsible mechanism for the redistribution phenomenon.4, 5 This later event and the patient's exposure to low temperatures in the operating room are the main factors inducing and maintaining perioperative hypothermia.5, 6, 7

Up to 20% of patients develop hypothermia in the perioperative period.8 This incidence increases significantly in the postoperative period, ranging from 60% to 90%.9 Since even mild hypothermia can result in unfavorable outcomes, it's imperative for the anesthesiologist to actively intervene in the perioperative hypothermia mechanism, to prevent its deleterious effects.10, 11, 12

Despite all these evidences, temperature monitoring is not routinely and systematically performed in many centers, including our hospital. Therefore, the aim of this pilot study was to determine whether the incidence of postoperative hypothermia (detected in the Post-Anesthetic Care Unit – PACU) is significant and if there are risk factors associated. Accordingly, this pilot study intends to detect the feasibility of a larger study, to test and refine a protocol of normothermia (targeted temperature management), to establish accurate recruitment targets and trial costs, and to confirm the sample size calculation.

Methods

Study design

We performed a multicenter, prospective pilot study of postoperative patients undergoing elective and emergency surgeries at Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal and Hospital Materno Infantil de Brasília.

Registration

The study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (Fundação de Ensino e Pesquisa em Ciências da Saúde, FEPECS, Brasília, DF, Brazil) and registered in Plataforma Brasil under CAAE number 2294615.0.0000.5553 and report number 1.418.778 (http://aplicacao.saude.gov.br/plataformabrasil).

Study population

All patients meeting inclusion criteria, between February and July of 2016, at both hospitals were assessed for eligibility. The inclusion criteria comprised patients who agreed to participate and signed the written informed consent; American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status PI–PIII; ages between 18 and 85 years old; and patients admitted to the PACU, whether extubated or who were not intubated. Those who remained intubated in the postoperative period (due to risk of sepsis and temperature deregulation) or who were admitted to the intensive care unit were not included. Ten patients were excluded because of missing data, as lack of temperature report.

Study protocol

Tympanic temperature was measured at the arrival and discharge from operating room. It was also measured at PACU, from admission through stay and discharge. Length of PACU stay, length of hospital stay, and occurrence of adverse events were evaluated as well.

The diagnosis of hypothermia was considered when patients presented central temperature <36 °C at PACU admission, determined by tympanic temperature. For data analysis, patients were divided in groups according to temperature and age. Hypothermic patients were referred to as Group H; normothermic patients as Group N; elderly patients as Group E; and young patients as Group Y. Demographic and clinical data, anesthesia technique, opioid use, type of surgery, warming in the operating room and PACU, prevalence of chills, complications, length of PACU stay and length of hospital stay were analyzed.

Data analysis

Sample size was based on previous study with 70 patients that evaluated the prevalence of hypothermia. Additional 20% subjects were required to allow adjustment of other factors, such as withdraws, missing data, and lost follow-up.13

Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to determine normal distribution of the continuous variables. Mann–Whitney test was applied to discrete variables not normally distributed. Chi-squared (χ2) or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables. Student's t test was applied to continuous variables with normal distribution. Wilcoxon test was applied to the discrete and paired variables. Data are expressed as means and standard deviations for continuous variables, medians and interquartile ranges for asymmetric variables, and in numbers and/or percentages for categorical variables.

Longitudinal analysis of repeated temperature measures was performed using Type II Wald Chi-Squared test from the deviance analysis for linear mixed effects models (lmer models from lme4 package and analysis of variance (ANOVA) from car package).

Univariate analysis was used to identify risk factors associated with postoperative hypothermia. Explanatory factors with significant univariate association with hypothermia (p < 0.20) were used to construct a forced entry multivariate logistic regression model, expressed in adjusted Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). The dummy variable method was applied for the polytomous categorical variables regression. Interactions between variables were systematically investigated and collinearity was considered when the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was higher than 10 and the level of tolerance (1/VIF) lower than 0.1. The likelihood ratio test was used to evaluate the final model discrimination for the prevalence of postoperative hypothermia, and the Hosmer–Lemeshow statistical method to test the model calibration. The area under the ROC curve was calculated as a descriptive tool to measure the model bias. p-Values under 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data was analyzed using CRAN's R statistical package version 3.4.1.

Results

Seventy-eight patients were included in the study. Sixty-two were female and 16 male (more female patients were included due to obstetric service). Ages ranged from 18 to 82 years old, with mean value of 39 years old. Mean weight was 72 kg, ranging from 48 kg to 111 kg. The minimum and maximum heights were 148 cm and 174 cm, with mean value of 162 cm. From the total number of procedures performed, 19 (24.4%) were under general anesthesia, 55 (70.5%) under regional anesthesia, and the remaining 4 (5.1%) underwent combined general and regional anesthesia. Mean duration of anesthesia was 112 min, with a minimum of 30 min and maximum of 420 min.

Fifty-four (69.2%) patients presented hypothermia at PACU admission. Fifty-one patients (65.4%) were between 34 °C and 35.9 °C, and three patients (3.8%) were under 34 °C (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis. Hypothermia (H) versus normothermia (N) group.

| Hypothermia (n = 54) |

Normothermia (n = 24) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.4 ± 16.8 | 42.9 ± 18.8 | 0.305a |

| Weight (kg) | 73.7 ± 14.5 | 69.7 ± 17.1 | 0.334a |

| Height (m) | 1.62 ± 0.07 | 1.62 ± 0.08 | 0.764a |

| Gender (M/F) | 13/39 | 9/16 | 0.317b |

| ASA classification, n (%) | |||

| I | 9 (16.7) | 6 (25) | 0.380b |

| II | 38 (70.3) | 13 (54.2) | |

| III | 7 (13) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Elderly, n (%) | 8 (14.8) | 6 (25) | 0.359b |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 17 (31.5) | 8 (33.3) | 0.952b |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 5 (9.2) | 6 (25) | 0.091b |

| Obesity, n (%) | 10 (18.5) | 3 (12.5) | 0.428b |

| Hypothyroidism, n (%) | 2 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0.320b |

| Anesthesia, n (%) | |||

| General | 6 (11.1) | 13 (54.2) | <0.001b, e |

| Regional | 46 (85.2) | 9 (37.5) | |

| Combined | 1 (1.8) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Use of opioids, n (%) | |||

| Fentanyl | 6 (11.1) | 8 (33.3) | |

| Sufentanil | 4 (7.4) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Morphine | 3 (5.6) | 1 (4.2) | 0.003c, e |

| Sufentanil + morphine | 13 (24) | 0 (0) | |

| Fentanyl + morphine | 2 (3.7) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Remifentanil + morphine | 0 (0) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Fentanyl + remifentanil | 0 (0) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Types of surgery, n (%) | 4 (7.4) | ||

| Broncoesofagology | 1 (1.85) | 0 (0) | |

| Oral and maxillofacial | 0 (0) | 1 (4.17) | |

| Head and neck | 1 (1.85) | 0 (0) | |

| General surgery | 2 (3.7) | 2 (8.33) | |

| Oncology | 2 (3.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Thoracic | 2 (3.7) | 3 (12.5) | 0.612b |

| Vascular | 2 (3.7) | 1 (4.17) | |

| Gynecology | 1 (1.85) | 0 (0) | |

| Obstetric | 27 (50) | 10 (41.7) | |

| Neurosurgery | 2 (1.85) | 0 (0) | |

| Orthopedia | 5 (9.26) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Urology | 9 (16.7) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Prolonged wakefulness, n (%) | (0) | (0) | – |

| Heating with air in OR, n (%) | 8 (14.8) | 1 (4.2) | 0.194b |

| Heating with mattress in OR, n (%) | 3 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 0.251b |

| Heated serum in OR, n (%) | 17 (31.5) | 8 (33.3) | 0.700b |

| Heating with air in PACU, n (%) | 4 (7.4) | 2 (8.3) | 0.661c |

| Heating with mattress in PACU, n (%) | 2 (3.7) | 1 (4.2) | 0.780b |

| Heated serum in PACU, n (%) | 4 (7.4) | 42 (8.3) | 0.655c |

| Length of stay in the PACU (min) | 94.73 ± 34.4 | 78.1 ± 30.3 | 0.057d |

| Length of hospital stay (hours) | 103.5 ± 115.2 | 111.3 ± 153.5 | 0.248d |

| Chills, n (%) | 7 (13) | 1 (4.2) | 0.203c |

| Complications, n (%) | 5 (9.3) | 0 (0) | 0.109b |

Categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as means and standard deviations.

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiology; OR: Operation Room; PACU: Post Anesthetic Care Unit.

Student's t test.

Chi-square test.

Fisher test.

Mann–Whitney U test.

p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Patients in the Hypothermia Group (H) predominantly underwent regional anesthesia (p < 0.001) and received the association of morphine and sufentanil (24% vs. 0%, respectively, for hypothermia and normothermia groups), while the normothermia group (N) received predominantly fentanyl (33.3% and 11.1%, respectively) (p = 0.003). There was no difference in the distribution of surgical specialties (Table 1).

Half of the elderly and 23% of the young patients were male (p = 0.045), and the mean ages were 70 and 33 years old, respectively (p < 0.001). There was a predominance of ASA physical status Grades II and III in the elderly patients group (50% and 42.9%, respectively), compared to young patients group (68.89% and 9.4%, respectively) (p = 0.006). In the elderly group, there was a predominance of urologic surgeries (57.15%), most cases being transurethral resection of the prostate, and in the young patients group there was a predominance of Cesarean sections (57.8%) (p = 0.004). Most young patients underwent regional or general anesthesia (73.4% and 25%, respectively), while 57.1% of elderly patients were submitted to regional anesthesia, 21.4% to general anesthesia and 21.4% to combined general and regional anesthesia (p = 0.009) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Elderly versus young group.

| Elderly (n = 14) |

Young patients (n = 64) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70.29 ± 6.2 | 33.3 ± 10.6 | <0.001a, d |

| Weight (kg) | 79 ± 20.4 | 71 ± 14.9 | 0.325a |

| Height (m) | 1.62 ± 0.1 | 1.62 ± 0.07 | 0.891a |

| Gender (M/F) | 7/7 | 15/49 | 0.045b, d |

| ASA classification, n (%) | 0.006b, d | ||

| I | 1 (7.1) | 14 (21.9) | |

| II | 7 (50) | 44 (68.8) | |

| III | 6 (42.9) | 6 (9.4) | |

| Hypertension | 11 (78.5) | 14 (22) | <0.001b, d |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (21.4) | 8 (12.5) | 0.385b |

| Obesity | 1 (7.1) | 12 (18.7) | 0.291b |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 (7.1) | 1 (1.6) | 0.231b |

| Anesthesia, n (%) | |||

| Inhalational | 4 (28.6) | 6 (9.4) | 0.097b |

| Total intravenous | 1 (7.1) | 10 (15.6) | |

| Anesthesia, n (%) | |||

| General | 3 (21.4) | 16 (25) | |

| Regional | 8 (57.1) | 47 (73.4) | 0.009b, d |

| Combined | 3 (21.4) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Use of opioids, n (%) | |||

| Fentanyl | 3 (21.4) | 11 (17.2) | |

| Sufentanil | 1 (7.1) | 4 (6.3) | |

| Morphine | 1 (7.1) | 3 (4.7) | 0.205c |

| Sufentanil + morphine | 0 (0) | 13 (20.3) | |

| Fentanyl + morphine | 2 (14.3) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Remifentanil + morphine | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Fentanyl + remifentanil | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Types of surgery, n (%) | |||

| Broncoesofagology | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Oral and maxillofacial | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Head and neck | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| General surgery | 2 (14.3) | 2 (3.13) | |

| Oncology | 0 (0) | 2 (3.13) | |

| Thoracic | 0 (0) | 4 (6.25) | 0.004c, d |

| Vascular | 1 (7.15) | 2 (3.13) | |

| Gynecology | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Obstetric | 0 (0) | 37 (57.8) | |

| Neurosurgery | 1 (7.15) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Orthopedia | 2 (14.3) | 7 (11) | |

| Urology | 8 (57.15) | 5 (7.8) | |

| Prolonged wakefulness, n (%) | (0) | (0) | – |

| Heating with air in OR, n (%) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (6.3) | 0.008b, d |

| Heating with mattress in OR, n (%) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (3.1) | 0.460c |

| Heated serum in OR, n (%) | 10 (71.4) | 15 (23.4) | 0.001b, d |

| Heating with air in PACU, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (9.4) | 0.171b |

| Heating with mattress in PACU, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (4.7) | 0.309b |

| Heated serum in PACU, n (%) | 2 (14.3) | 4 (6.3) | 0.437b |

| Chills, n (%) | 1 (7.1) | 7 (10.9) | 0.672b |

| Complications, n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (7.8) | 0.280b |

| Hypothermia, n (%) | 8 (57.1) | 45 (70.3) | 0.339b |

Categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as means and standard deviations.

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiology; OR: Operation Room; PACU: Post Anesthetic Care Unit.

Student's t test.

Chi-square test.

Fisher test.

p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Median tympanic temperature in the operating room decreased from admission (36.3 °C) through discharge (35.6 °C) (average difference: 0.9; 95% CI 0.514–0.799; p < 0.001). At PACU, there was an increase in median tympanic temperature at discharge (T = 36 °C) in relation to the admission temperature (T = 35.6 °C) (average difference: 0.4; 95% CI 0.657 to −0.206; p = 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Global analysis of the temperature from the operating room until the post anesthetic care unit.

| Outcome | Median (interquartile range) | Average difference (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tympanic temperature in the OR | |||

| Admission | 36.3 (35.8–36.6) | 0.9 (0.514–0.799) | <0.0001a |

| Discharge | 35.6 (35.0–36.1) | ||

| Tympanic temperature in the PACU | |||

| Admission | 35.6 (34.9–36.1) | 0.4 (−0.657 to 0.206) | 0.0001a |

| Discharge | 36.0 (35.6–36.5) | ||

Discrete variables were expressed as median and interquartile range.

OR: Operation Room; PACU: Post Anesthetic Care Unit; CI: Confidence Interval.

p < 0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed by Wilcoxon test.

Comparing age groups during PACU stay, there was a significant difference between the overall temperatures (p < 0.05) and in temperature evolution through all time intervals after 30 min, in which the elderly group showed a higher tendency to hypothermia and worse recovery over time (Table 4).

Table 4.

Evolution of the tympanic temperature in the PACU as a function of time in elderly (≥60 years) and young (<60 years) patients.

| Temperatures | Elderly (n = 14) |

Young (n = 64) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arrival on OR | 36.2 ± 0.4 | 36.4 ± 0.5 | 0.854 |

| Exit from OR | 35.7 ± 0.7 | 35.7 ± 0.55 | 0.384 |

| Arrival on PACU | 35.4 ± 0.6 | 35.8 ± 0.57 | 0.134 |

| 15 min | 35.6 ± 0.9 | 35.5 ± 0.68 | 0.650 |

| 30 min | 35.2 ± 0.6 | 35.7 ± 0.61 | 0.101 |

| 45 min | 35.3 ± 0.7 | 35.9 ± 0.79 | 0.033a |

| 1 h | 35.2 ± 0.8 | 36.0 ± 0.65 | 0.004a |

| 1 h 15 min | 35.2 ± 0.7 | 36.1 ± 0.49 | <0.001a |

| 1 h 30 min | 34.8 ± 0.8 | 36.1 ± 0.5 | 0.001a |

| 1 h 45 min | 35.1 ± 0.5 | 36.1 ± 0.58 | 0.010a |

| 2 h | 35.5 ± 0.4 | 36.1 ± 0.6 | 0.202 |

| 2 h 15 min | 35.6 ± 0.7 | 35.9 ± 0.59 | 0.643 |

| Exit from PACU | 35.6 ± 0.7 | 36.1 ± 0.59 | 0.018a |

Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as means and standard deviations.

OR: Operation Room; PACU: Post Anesthetic Care Unit; min: minutes.

p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Data were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test.

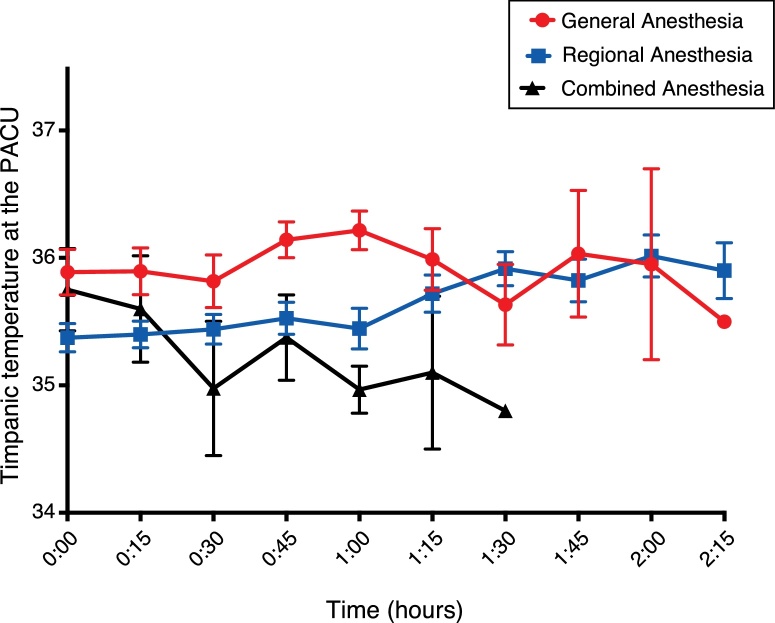

As for anesthetic technique and evolution of temperature through PACU stay, patients under combined anesthesia presented the highest levels of hypothermia, followed by regional anesthesia, and general anesthesia technique showed the best indicators (p < 0.001). This could be clearly observed in the intervals of 60 and 75 min (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Evolution of the tympanic temperature in the PACU as a function of time in patients undergoing general, regional and combined anesthesia. Differences in temperature were globally statistically significant (*p < 0.001) and in each time interval where the bars don’t intersect. Continuous red line: general anesthesia group; continuous blue line: regional anesthesia group; continuous black line: combined anesthesia group. *p < 0.05 was considered significant. PACU, Post Anesthetic Care Unit.

Longitudinal analysis of repeated temperature measures evidenced that spinal anesthesia correlated to both a lower initial temperature at PACU (p = 0.00002) and a faster recovery rate (p = 0.01). In patients undergoing cesarean section, spinal anesthesia mildly associated to temperature recovery rate at PACU (p = 0.02427), whereas in non-obstetric patients, spinal anesthesia was associated only to a lower temperature at PACU admission (p = 0.0002587). The use of warm forced-air convection correlated to a faster temperature raising at PACU (p = 0.0000003). Operating room temperature correlated to PACU admission temperature (p = 0.0305). Age strongly correlated to rate of temperature recovery (p = 0.000000076). Gender correlated to rate of temperature recovery, being faster on women (p = 0.0039). Opioid choice was associated with both temperature at PACU admission (p = 0.008) and temperature recovery rate at PACU (p = 0.0000073) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Analysis of deviance table (Type II Wald Chi-Square tests) of linear mixed effects model to predict temperature.

| Independent variable | Chi-square | Pr (>Chi-square) |

|---|---|---|

| Spinal anesthesia | ||

| Temperature | 63.0562 | <0.0001a |

| Spinal | 17.9251 | <0.0001a |

| Temperature: Spinal | 5.6002 | 0.01796a |

| Cesarea considering use of spinal anesthesia | ||

| Temperature | 86.7207 | <0.000a |

| Spinal | 0.1661 | 0.68357 |

| Temperature: Spinal | 5.0752 | 0.02427a |

| Hot air convection | ||

| Temperature | 86.1308 | <0.0001a |

| Hot air convection | 0.9452 | 0.3309 |

| Temperature: Hot air convection | 25.8577 | <0.0001a |

| Age (years) | ||

| Temperature | 66.4415 | <0.0001a |

| Age | 1.9894 | 0.1584 |

| Temperature: Age | 28.8965 | <0.0001a |

| Gender | ||

| Temperature | 62.5628 | <0.0001a |

| Gender | 0.0932 | 0.760136 |

| Temperature: Gender | 8.3174 | 0.0033927a |

| OR temperature | ||

| Temperature | 14.0678 | 0.0001763a |

| OR temperature | 4.6765 | 0.03057a |

| Opioid use | ||

| Temperature | 18.566 | <0.0001a |

| Opioid use | 17.084 | 0.008981a |

| Temperature: Opioid use | 33.810 | <0.0001a |

p < 0.05 was considered significant.

After univariate analysis, the following candidate variables were selected for multivariate analysis: diabetes mellitus, anesthesia technique, use of opioids, air-forced warming in OR, length of PACU stay and complications.

The variables’ collinearity test showed a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) between 1.055 and 1.125, and a tolerance level between 0.889 and 0.941, demonstrating non-colinearity among variables. The likelihood ratio test revealed that the model including hypothermia was significant (X2 [11] = 21.54; p = 0.028). The Hosmer–Lemeshow analysis indicated the model's positive predictive validity (p = 0.988). The explanatory model based on these variables resulted in an area under the ROC curve of 0.349 (95% CI 0.210–0.488). However, the multivariate analysis was not able to identify independent risk factors for postoperative hypothermia. Protective factors such as general anesthesia and fentanyl use were observed (Table 6).

Table 6.

Results of the multivariate analysis.

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus (Yesa/No) | 3.032 | 0.826–11.127 | 0.095 |

| Type of anesthesia | |||

| Regionala | 1 | – | |

| General | 0.119 | 0.035–0.397 | 0.001b |

| Combined | 1.091 | 0.081–14.664 | 0.948 |

| Use of opioids | |||

| Sufentanil + morphinea | 1 | – | – |

| Fentanyl | 0.159 | 0.038–0.657 | 0.011b |

| Sufentanil | 2.545 | 0.257 | 0.424 |

| Morphine | 1.826 | 0.173 | 0.617 |

| Fentanyl + morphine | 1.846 | 0.232 | 0.562 |

| Heating with air in OR (Yesa/No) | 4.200 | 0.492–35.873 | 0.190 |

| Length of stay in the PACU (hours) | 0.985 | 0.967–1.003 | 0.102 |

| Complications (Yesa/No) | 0.906 | 0.830–0.988 | 0.112 |

OR: Operation Room; PACU: Post Anesthetic Care Unit; CI: Confidence Interval. Data were analyzed by logistic regression.

Reference category.

p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrated that hypothermia is still a frequent problem in our service. This study showed that 69.2% of patients had temperatures <36 °C at PACU admission.

Both old and recent observational studies also point to a high prevalence of hypothermia in the perioperative period. Poveda et al., in a study with 70 patients, observed a significant drop in patients’ temperature in the first hour of surgery, reaching a mean of 33.6 °C by the end of the fourth hour.14 Vaughan and colleagues, in a study with 198 patients, observed a 60% prevalence of hypothermia in the Postoperative Care Unit (PACU).13 More recently, Gurunathan et al. observed that, from the 87 elderly patients who underwent hip surgery, one third was hypothermic at PACU arrival, despite active warming methods.15

Our finding of predominance of hypothermia in patients undergoing regional anesthesia contrasts with the literature, since disturbances in the thermal equilibrium caused by neuraxial anesthesia are considered to be similar to general anesthesia, and less than combined anesthesia.16 Probably, this may be due to our considerable number of individuals who underwent regional anesthesia receiving subarachnoid administration of opioids (morphine or morphine associated with sufentanil). Also, the high number of patients scheduled to urological surgeries may have contributed to increased hypothermia incidence, since bladder irrigation may certainly increase thermal disregulation. A study with 40 patients scheduled to transurethral resection of the prostate compared irrigation solutions at 21 °C and 37 °C. There was a significant decrease in temperature of patients receiving fluids at room temperature.17 Our findings agree with this result.

The proposed mechanism for hypothermia caused or exacerbated by intrathecal opioids administration is not yet fully understood. A study suggests that this phenomenon occurs due to the dispersion of the circulating soluble opioids into the hypothalamus, exerting pharmacological effects in mu receptors of the thermoregulatory center, or through peripheral spinal kappa receptors.18 Models in animals using intrathecal sufentanil, alfentanil and morphine corroborate these assertions, as well as clinical studies in humans.19, 20 In a study with 60 patients undergoing cesarean section, the authors compared the temperatures of those receiving spinal anesthesia with bupivacaine alone and those with bupivacaine and morphine. Decreases in the tympanic temperature were observed in both groups, with more significant hypothermia in those patients receiving intrathecal opioids.21

In our study, the longitudinal assessment of tympanic temperature in the PACU showed elderly patients with lower temperatures and longer delays in hypothermia regression than younger patients. This fact is confirmed by literature, which reports a higher prevalence and longer duration of perioperative hypothermia in this age group.14, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Older individuals have a lower response to heat stress, mainly because of inferior vasoconstriction ability, reduced muscle mass and decreased ability to produce heat,27 enhancing their risk for hypothermia and its deleterious effects.

In the PACU dynamic temperature assessment, the combined anesthesia technique also resulted in worse levels of hypothermia, followed by regional and general anesthesia. This finding may be explained by the loss in core thermoregulation caused by general anesthesia associated to the inability of a thermoregulatory response in lower limbs secondary to the regional technique; all together lead to more intense hypothermia and slower recovery to normal thermal patterns than when these anesthetic techniques are administered individually.16 According to Horn et al., without prewarming, 72% of the patients scheduled for major abdominal surgery under combined general and epidural anesthesia became hypothermic.28 In another study, a rapid temperature decrease during combined general and epidural anesthesia was also observed in five healthy volunteers and in patients undergoing colorectal surgery. The vasoconstriction threshold was near 34.5 °C. When the study ended after three hours of anesthesia, patients under combined anesthesia were 1.2 °C more hypothermic than those under general anesthesia alone.29 This effect was also found in our study.

Our study was not able to identify independent risk factors for postoperative hypothermia due to the limited sample. Multivariate analysis found that general anesthesia accompanied by fentanyl were protective factors, however these findings are in disagreement with the literature also probably because of the limited sample.

Cross-sectional studies area suitable for identifying the risks factors that may influence the probability of occurrence of a given clinical condition, and do not consider any treatment in question, since they only allow for observation of individuals from exposure to outcome. This study type also presents other important limitations, such as the difficulty in investigating conditions of low prevalence and the research team is not being able to control the complete process of the trial in progress. In addition, it is necessary to highlight the use of a small sample size as a limitation of the present study; however, this is a pilot study designed to provide data for a more complete study.30

We were able to confirm that out study, like other cross-sectional studies, was safe, easy to apply, relatively fast to run, very low cost, with the possibility of analyzing several data through a simple observation of the patient in the PACU. We state that a larger number of patients are necessary for a more accurate analysis, the exclusion of observational biases and deeper analysis of the risk factors most related to hypothermia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this pilot study showed that perioperative hypothermia is still a prevalent problem in our anesthetic practice. More than half of the analyzed patients presented hypothermia through PACU stay, with a higher incidence in elderly patients, patients undergoing combined anesthesia and those under regional anesthesia with intrathecal opioids. An accurate sample size calculation for a definitive cross-sectional study can be made. In conclusion, we have demonstrated the feasibility of a large, multicenter, cross-sectional study of postoperative hypothermia in the post-anesthetic care unit.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sessler D.I. Mild perioperative hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1730–1737. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706123362407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez M., Sessler D.I., Walter K., et al. Rate and gender dependence of the sweating, vasoconstriction, and shivering thresholds in humans. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:780–788. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yousef M.K., Dill D.B., Vitez T.S., et al. Thermoregulatory responses to desert heat: age, race and sex. J Gerontol. 1984;39:406–414. doi: 10.1093/geronj/39.4.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sessler D.I. Perioperative thermoregulation and heat balance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;813:757–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsukawa T., Sessler D.I., Sessler A.M., et al. Heat flow and distribution during induction of general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:662–673. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Angelo Vanni S.M., Castiglia Y.M.M., Ganem E.M., et al. Preoperative warming combined with intraoperative skin-surface warming does not avoid hypothermia caused by spinal anesthesia in patients with midazolam premedication. Sao Paulo Med J Rev Paul Med. 2007;125:144–149. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802007000300004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark R.E., Orkin L.R., Rovenstine E.A. Body temperature studies in anesthetized man: effect of environmental temperature, humidity, and anesthesia system. J Am Med Assoc. 1954;154:311–319. doi: 10.1001/jama.1954.02940380021007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurz A. Physiology of thermoregulation. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2008;22:627–644. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart S.M., Lujan E., Huff C.L. Innovations and excellence: the incidence of adult hypothermia in the postanesthesia care unit. Perioper Nurs Q. 1987;3:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank S.M., Fleisher L.A., Breslow M.J., et al. Perioperative maintenance of normothermia reduces the incidence of morbid cardiac events. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1997;277:1127–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurz A., Sessler D.I., Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1209–1216. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605093341901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmied H., Kurz A., Sessler D.I., et al. Mild hypothermia increases blood loss and transfusion requirements during total hip arthroplasty. Lancet Lond Engl. 1996;347:289–292. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90466-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaughan M.S., Vaughan R.W., Cork R.C. Postoperative hypothermia in adults: relationship of age, anesthesia, and shivering to rewarming. Anesth Analg. 1981;60:746–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poveda V.B., Galvao C.M., Dantas R.A.S. Hipotermia no período intra-operatório em pacientes submetidos a cirurgias eletivas. Acta Paul Enferm. 2009;22:361–366. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurunathan U., Stonell C., Fulbrook P. Perioperative hypothermia during hip fracture surgery: An observational study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23:762–766. doi: 10.1111/jep.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sessler D.I. Perioperative heat balance. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:578–596. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh R., Asthana V., Sharma J.P., et al. Effect of irrigation fluid temperature on core temperature and hemodynamic changes in transurethral resection of prostate under spinal anesthesia. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8:209–215. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.134508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawls S.M., Benamar K. Effects of opioids, cannabinoids, and vanilloids on body temperature. Front Biosci Sch Ed. 2011;3:822–845. doi: 10.2741/190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabbe M.B., Grafe M.R., Mjanger E., et al. Spinal delivery of sufentanil, alfentanil, and morphine in dogs. Physiologic and toxicologic investigations. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:899–920. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199410000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kavee E.H., Bernstein J., Zakowski M.I., et al. The hypothermic action of epidural and subarachnoid morphine in parturients. Reg Anesth. 1991;16:325–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hui C.-K., Huang C.-H., Lin C.-J., et al. A randomised double-blind controlled study evaluating the hypothermic effect of 150 μg morphine during spinal anaesthesia for Caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:29–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeGroot D.W., Havenith G., Kenney W.L. Responses to mild cold stress are predicted by different individual characteristics in young and older subjects. J Appl Physiol Bethesda Md 1985. 2006;101:1607–1615. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00717.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wetz A.J., Perl T., Brandes I.F., et al. Unexpectedly high incidence of hypothermia before induction of anesthesia in elective surgical patients. J Clin Anesth. 2016;34:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kongsayreepong S., Chaibundit C., Chadpaibool J., et al. Predictor of core hypothermia and the surgical intensive care unit. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:826–833. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000048822.27698.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agrawal N., Sewell D.A., Griswold M.E., et al. Hypothermia during head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1278–1282. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200308000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frank S.M., Beattie C., Christopherson R., et al. Epidural versus general anesthesia, ambient operating room temperature, and patient age as predictors of inadvertent hypothermia. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:252–257. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199208000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenney W.L., Munce T.A. Invited review: aging and human temperature regulation. J Appl Physiol Bethesda Md 1985. 2003;95:2598–2603. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00202.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horn E.-P., Bein B., Broch O., et al. Warming before and after epidural block before general anaesthesia for major abdominal surgery prevents perioperative hypothermia: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016;33:334–340. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joris J., Ozaki M., Sessler D.I., et al. Epidural anesthesia impairs both central and peripheral thermoregulatory control during general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:268–277. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knight P. Conducting research in anaesthesia and intensive care medicine. Anesthesiol J Am Soc Anesthesiol. 2002;97:1327–1328. [Google Scholar]