Abstract

The performance and clinical implications of the deep learning aided algorithm using electrocardiogram of heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (DeepECG-HFrEF) were evaluated in patients with acute HF. The DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm was trained to identify left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD), defined by an ejection fraction (EF) < 40%. Symptomatic HF patients admitted at Seoul National University Hospital between 2011 and 2014 were included. The performance of DeepECG-HFrEF was determined using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values. The 5-year mortality according to DeepECG-HFrEF results was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method. A total of 690 patients contributing 18,449 ECGs were included with final 1291 ECGs eligible for the study (mean age 67.8 ± 14.4 years; men, 56%). HFrEF (+) identified an EF < 40% and HFrEF (−) identified EF ≥ 40%. The AUC value was 0.844 for identifying HFrEF among patients with acute symptomatic HF. Those classified as HFrEF (+) showed lower survival rates than HFrEF (−) (log-rank p < 0.001). The DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm can discriminate HFrEF in a real-world HF cohort with acceptable performance. HFrEF (+) was associated with higher mortality rates. The DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm may help in identification of LVSD and of patients at risk of worse survival in resource-limited settings.

Subject terms: Machine learning, Cardiovascular diseases, Diagnostic markers, Prognostic markers

Introduction

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) increases the risk of systemic embolism, stroke, and death compared to heart failure (HF) with preserved LV systolic function1. Although Vasan et al. showed a decline in asymptomatic LVSD over the past three decades, the prognosis of LVSD has remained unchanged, emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and adequate management of LVSD2. While echocardiography is the standard tool for LVSD diagnosis, the results are highly influenced by operator-dependent factors and its interpretation is subjective, resulting in high dependence to assessor’s expertise3. These limitations restrict the routine use of echocardiography in a resource-limited medical setting. Thus, the development of alternative screening tools for LVSD has been attempted, such as biochemical options and electrocardiogram (ECG)4–9.

The use of ECG for LVSD diagnosis has been ongoing since 1996, from identification of simple abnormalities on ECG to the more recent development of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms5,7–15. Various AI algorithms have been developed and performed based on different definitions of LVSD (e.g., ejection fraction (EF) < 35%7,10,14, < 40%8,9,11–13, or < 50%12) and for distinct study populations9,13. Despite advancement in AI-based LVSD diagnosis, an AI algorithm to identify LVSD patients with an EF < 40% has not been validated in a clinical population of patients with symptomatic HF regardless of EF. To address this gap, we validated the previously developed AI algorithm by Cho et al.8 into a deep learning-aided algorithm using ECG for HF with reduced ejection fraction (DeepECG-HFrEF) to identify LVSD, specifically LVSD with an EF < 40% among symptomatic HF patients regardless of EF. For training, we used 12-lead 10 s ECGs recorded from patients with symptomatic HF at Seoul National University Hospital who were enrolled in the Korean Acute HF (KorAHF) Registry. We further evaluated the predictive power of the DeepECG-HFrEF on 5-year all-cause mortality.

Results

Baseline characteristics

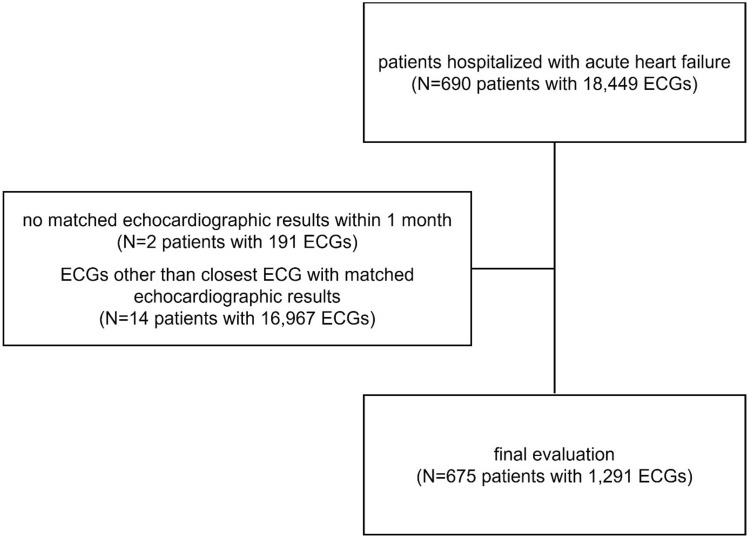

A total of 690 patients, contributing 18,449 ECGs, who were hospitalized for acute HF were eligible. Of these, those with no matching echocardiography within one month of enrollment (191 ECGs from 2 patients) and ECGs that were not the closest matching to the echocardiography (16,979 ECGs from 14 patients) were excluded. After exclusion, 675 patients contributing 1291 ECGs were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). The mean time interval between the ECG and echocardiography was 29.1 h, with over 82.1% (1060/1291) of the ECGs matched within 24 h of the index echocardiography.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart—Among the patients hospitalized with acute heart failure, subjects with no matching echocardiographic results within 1 months and electrocardiograms other than closest match to the echocardiographic results were excluded. ECG electrocardiogram.

Characteristics of the patients based on the archived ECGs classified by DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm are presented in Table 1. Characteristics of the study population according to echocardiographic results at enrollment are summarized in Supplemental Table S1. Owing to the usage of multiple ECGs from the same patient, the sum of DeepECG-HFrEF based patient-set was larger than the original patient-set. However, the paired datasets were used per patient mostly once or twice. Those classified in the DeepECG-HFrEF (+) group were more likely to be men, to have more comorbidities, to be admitted for de novo HF than for acute decompensated HF, and to present with more severe symptoms of dyspnea. Among the etiologies of HF, ischemic (45.8%) was the most common etiology in the DeepECG-HFrEF (+) group, whereas valvular heart disease (30.1%) was the most common etiology in the DeepECG-HFrEF (−) group. The most prevalent HF group also differed between the two groups, with HFrEF being the most prevalent in the DeepECG-HFrEF (+) group and HFpEF in the DeepECG-HFrEF (−) group. The echocardiographic values differed between the two groups. The DeepECG-HFrEF (+) group showed worse EF along with worse early diastolic velocity (E/e’), and right ventricle systolic pressure (RVSP). These results were consistently observed when confined to ECGs specifically corresponding to HFrEF patients (Supplement Table S2). The confidence score of DeepECG-HFrEF for each ECG was presented with corresponding left ventricular end systolic dimension (LVESD) as scatterplot (Supplement Figure S1). False-positive cases appeared to have smaller LVESD than true-positive cases and similar pattern was seen on false-negative cases when compared to true-negative cases.

Table 1.

Clinical data of the patients according to the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm.

| DeepECG-HFrEF (+) (N = 600) | DeepECG-HFrEF (−) (N = 691) | Overall (N = 1291) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | 68.5 ± 13.5 | 67.2 ± 15.2 | 67.8 ± 14.4 | 0.102 |

| Men | 398 (66.3%) | 325 (47.0%) | 723 (56.0%) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.4 ± 4.0 | 23.7 ± 3.9 | 23.6 ± 4.0 | 0.122 |

| Current smoker | 90 (15.0%) | 88 (12.7%) | 178 (13.8%) | 0.257 |

| Hypertension | 379 (63.2%) | 391 (56.6%) | 770 (59.6%) | 0.017 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 266 (44.3%) | 237 (34.3%) | 503 (39.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Status of HF | 0.027 | |||

| De novo HF | 163 (27.2%) | 151 (21.9%) | 314 (24.3%) | |

| Acute decompensated HF | 437 (72.8%) | 437 (78.1%) | 977 (75.7%) | |

| HF class according to EF | < 0.001 | |||

| HFpEF | 90 (15.0%) | 448 (64.8%) | 538 (41.7%) | |

| HFmrEF | 86 (14.3%) | 120 (17.4%) | 206 (16.0%) | |

| HFrEF | 424 (70.7%) | 123 (17.8%) | 547 (42.4%) | |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| EF, % | 33.5 ± 12.8 | 51.6 ± 12.9 | 43.2 ± 15.7 | < 0.001 |

| LVESV, mL | 131.7 ± 72.2 | 76.7 ± 46.5 | 110.7 ± 69.0 | < 0.001 |

| LVEDV, mL | 184.3 ± 81.9 | 131.3 ± 55.8 | 164.1 ± 77.4 | < 0.001 |

| E/A ratio | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| Deceleration time, ms | 159.6 ± 66.1 | 201.0 ± 92.3 | 182.9 ± 84.4 | < 0.001 |

| E/e' | 21.9 ± 11.1 | 19.4 ± 13.0 | 20.5 ± 12.3 | 0.001 |

| RVSP, mmHg | 48.2 ± 14.7 | 44.6 ± 15.7 | 46.2 ± 15.3 | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory | ||||

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 57.6 ± 30.7 | 64.0 ± 32.7 | 60.9 ± 31.9 | 0.001 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 1745.4 ± 1547.4 | 1043.4 ± 1240.5 | 1444.5 ± 1464.5 | < 0.001 |

BMI body mass index, BNP B-type natriuretic peptide, ECG electrocardiogram, EF ejection fraction, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, HF heart failure, HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, HFmrEF heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction, HFrEF heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, LVEDV left ventricular end-diastolic volume, LVESV left ventricular end systolic volume, RVSP right ventricular systolic pressure.

ECG findings

The differences in various ECG parameters between the two DeepECG-HFrEF groups are shown in Table 2. The DeepECG-HFrEF (+) group showed a higher heart rate with longer QRS duration and QTc interval, as well as more prominent QRS widening, QTc prolongation, and Q wave. The two groups did not differ in the PR interval, PR prolongation, or axis. Among causes of QRS widening, left bundle branch block (LBBB) and intraventricular conduction delay (IVCD) were more common in the DeepECG-HFrEF (+) than (−) group (p = 0.001). Similar patterns were observed within the ECGs of HFrEF patients (Supplement Table S3).

Table 2.

ECG findings according to the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm.

| DeepECG-HFrEF (+) (n = 600) | DeepECG-HFrEF (−) (n = 691) | Overall ECG (n = 1291) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, pbm | 90.7 ± 22.3 | 79.4 ± 20.5 | 84.7 ± 22.1 | < 0.001 |

| PR interval, ms | 173.6 ± 36.5 | 173.8 ± 40.8 | 173.7 ± 38.7 | 0.946 |

| QRS duration, ms | 120.3 ± 32.4 | 106.5 ± 28.5 | 112.9 ± 31.2 | 0.049 |

| QTc interval, ms | 484.8 ± 48.7 | 460.1 ± 44.0 | 471.6 ± 47.8 | < 0.001 |

| Rhythm | ||||

| Sinus rhythm | 412 (68.7%) | 422 (61.1%) | 834 (64.6%) | 0.005 |

| AF or AFL | 159 (26.5%) | 232 (33.6%) | 391 (30.3%) | 0.006 |

| Other* | 30 (5.0%) | 37 (5.4%) | 67 (5.2%) | 0.803 |

| PR prolongation† | 62 (16.1%) | 57 (14.2%) | 119 (9.2%) | 0.487 |

| QRS widening‡ | 134 (22.3%) | 94 (13.6%) | 228 (17.7%) | < 0.001 |

| LBBB | 40 (6.7%) | 19 (2.7%) | 59 (4.6%) | 0.001 |

| RBBB | 27 (4.5%) | 45 (6.5%) | 72 (5.6%) | 0.144 |

| IVCD | 39 (6.5%) | 17 (2.5%) | 26 (4.3%) | 0.001 |

| QTc prolongation§ | 440 (73.3%) | 317 (45.9%) | 757 (58.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Q wave | 166 (27.7%) | 111 (16.1%) | 277 (21.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Anteroseptal | 106 (17.7%) | 48 (6.9%) | 154 (11.9%) | |

| Lateral wall | 11 (1.8%) | 1 (0.1%) | 12 (0.9%) | |

| Inferior wall | 49 (8.2%) | 62 (9.0%) | 111 (8.6%) | |

| Axis | 0.937 | |||

| Normal or LAD | 511 (85.3%) | 588 (85.1%) | 1099 (85.1%) | |

| RAD or no mans' land | 88 (14.7%) | 103 (14.9%) | 191 (14.8%) | |

*VT, VF, high-degree AVB or junctional rhythm.

†PR interval > 200 ms.

‡QRS duration > 140 ms.

§Male > 450 ms, Female > 470 ms.

Performance of the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm for different EF cut-offs

The performance of the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm for different EF cut-off values are reported in Supplement Table S4. Using the optimal cut-off, based on Youden's index, the AUC value for identifying HFrEF among patients with HF was 0.845. For an EF < 40% cut-off, the sensitivity was 0.779, with specificity of 0.763, positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.708, negative predictive value (NPV) of 0.824, and accuracy of 0.770. The AUC, sensitivity, PPV, and accuracy increased, while NPV decreased with an increase in EF.

Performance of the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm according to actual EF

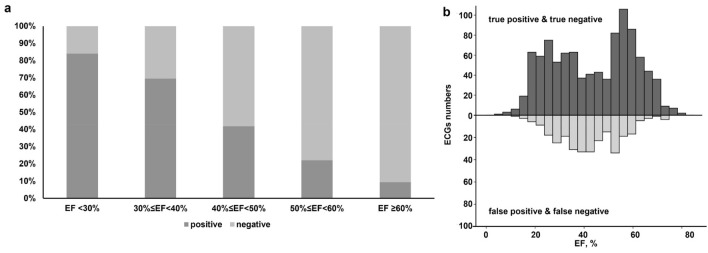

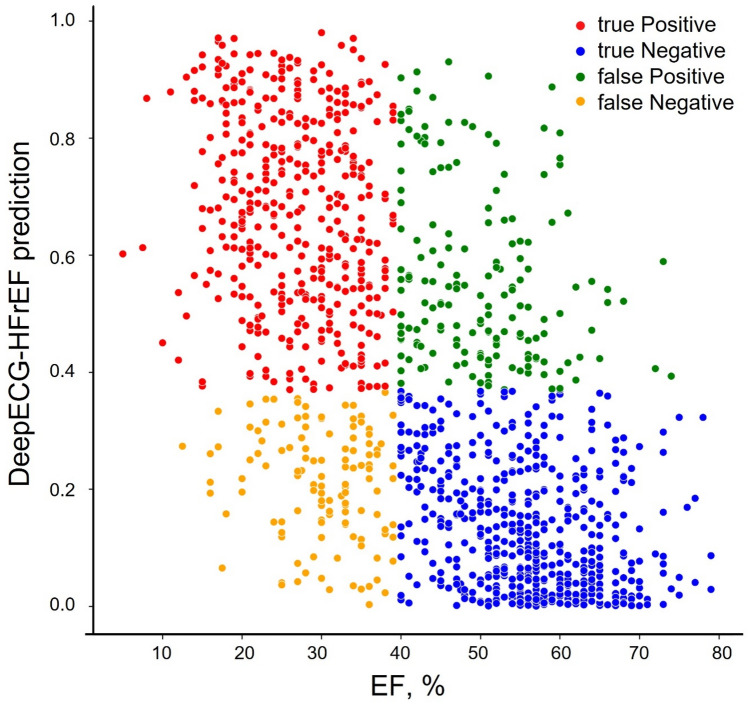

The proportion of patients diagnosed with DeepECG-HFrEF (+) increased when the actual EF was lower (Fig. 2A). The DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm was more likely to yield false-positive and false-negative results when the actual EF was near 40% (Fig. 2B). The scatter plot also shows a higher proportion of correct classifications (true-positives) when the actual EF was lower (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

(a) Proportion of DeepECG-HFrEF (+) according to actual EF (b) Distribution of correct and incorrect cases of DeepECG-HFrEF according to actual EF—The proportion of patients diagnosed with DeepECG-HFrEF (+) increased with the lower actual EF. The false-positives and false-negatives of DeepECG-HFrEF were more likely yielded when the EF was near 40%. ECG electrocardiogram, EF ejection fraction.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot demonstrating observed EF and DeepECG-HFrEF prediction—The proportion of true-positives was higher with lower actual EF even in the scatter plot. EF ejection fraction.

Performance of DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm in different subpopulations

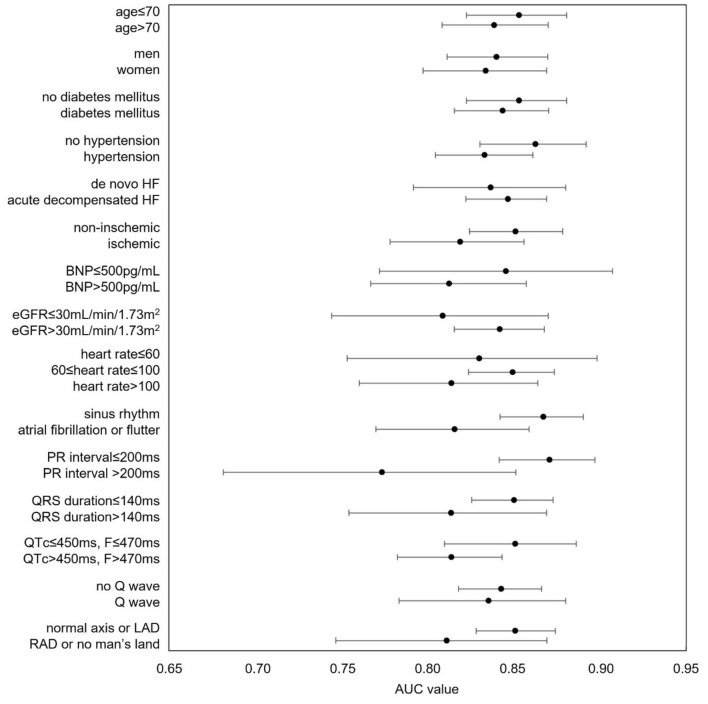

Figure 4 is a forest plot of the AUC and associated 95% confidence interval (CI) for the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm according to various clinical patient parameters. The performance of the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm was slightly better in the subgroups of patients: age ≤ 70 years, without hypertension, non-ischemic HF, sinus rhythm, PR interval ≤ 200 ms, QRS duration ≤ 140 ms, corrected QT interval of ≤ 450 ms for men and ≤ 470 ms for women, and normal axis or LAD.

Figure 4.

Forest plot depicting AUC values (95% confidence interval) of the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm in identifying LVSD in different subpopulation. The forest plot of DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm showed similar performance among various clinical parameters. AUC area under the receiver-operator characteristic curve, BNP B-type natriuretic peptide, EF ejection fraction, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, HF heart failure, LAD left axis deviation, RAD right axis deviation.

The 5-year all-cause mortality

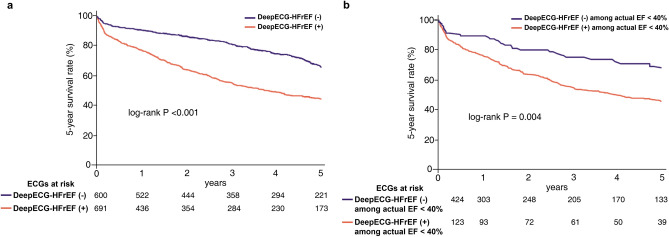

Overall, the 5-year survival was worse in the DeepECG-HFrEF (+) than (−) group (p < 0.001; Fig. 5A). The Kaplan–Meier curve also showed a lower survival rate among patients with an actual EF< 40% (Fig. 5B). The crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for 5-year all-cause mortality for the three different models are reported in Table 3 All components of model 1 showed significantly increased crude HR and multivariable-adjusted HR. In model 2, echocardiographic EF < 40% added to model 1, DeepECG-HFrEF (+) remained as significantly higher HR even after multivariable-adjustment. In model 3, which included a B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) > 500 pg/mL added to model 1, DeepECG-HFrEF (+) was offset by BNP.

Figure 5.

(a) Kaplan–Meier curve for mortality at 5-year follow up according to the DeepECG-HFrEF (Total ECGs = 1291) (b) Kaplan–Meier curve for mortality at 5-year follow up according to the DeepECG-HFrEF among patients with actual EF < 40%—The patients classified as DeepECG-HFrEF positive showed worse 5-year survival. ECG electrocardiogram; EF ejection fraction.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted hazard ratio for 5-year all-cause mortality among 1291 of heart failure ECGs.

| Crude | Multivariable adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| Age > 70 | 2.733 (2.269–3.291) | < 0.001 | 2.734 (2.192–3.411) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.674 (1.416–1.980) | < 0.001 | 1.235 (1.007–1.515) | 0.043 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 1.764 (1.486–2.094) | < 0.001 | 1.357 (1.106–1.665) | 0.003 |

| CKD stage 4–5 | 1.849 (1.464–2.336) | < 0.001 | 1.590 (1.250–2.023) | < 0.001 |

| DeepECG-HFrEF (+) | 1.496 (1.265–1.770) | < 0.001 | 1.351 (1.109–1.646) | 0.003 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Age > 70 | 2.733 (2.269–3.291) | < 0.001 | 2.726 (2.184–3.403) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.674 (1.416–1.980) | < 0.001 | 1.235 (1.006–1.515) | 0.043 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 1.764 (1.486–2.094) | < 0.001 | 1.362 (1.110–1.673) | 0.003 |

| CKD stage 4–5 | 1.849 (1.464–2.336) | < 0.001 | 1.591 (1.251–2.023) | < 0.001 |

| DeepECG-HFrEF (+) | 1.496 (1.265–1.770) | < 0.001 | 1.381 (1.099–1.734) | 0.006 |

| EF < 40% | 1.215 (1.027–1.438) | 0.023 | 1.044 (0.831–1.310) | 0.713 |

| Model 3 | ||||

| Age > 70 | 2.733 (2.269–3.291) | < 0.001 | 2.693 (1.981–3.660) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.674 (1.416–1.980) | < 0.001 | 1.016 (0.770–1.339) | 0.913 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 1.764 (1.486–2.094) | < 0.001 | 1.375 (1.042–1.813) | 0.024 |

| CKD stage 4–5 | 1.849 (1.464–2.336) | < 0.001 | 1.719 (1.245–2.375) | 0.001 |

| DeepECG-HFrEF (+) | 1.496 (1.265–1.770) | < 0.001 | 1.103 (0.837–1.453) | 0.487 |

| BNP > 500, pg/mL | 1.693 (1.221–2.348) | 0.002 | 1.585 (1.126–2.232) | 0.008 |

BNP B-type natriuretic peptide, CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease, ECG electrocardiogram, EF ejection fraction, HR hazard ratio.

Discussion

In this study, we validated the DeepECG-HFrEF to identify LVSD in patients with symptomatic HF regardless of EF and evaluated the predictive power of the algorithm for the 5-year all-cause mortality. The DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm showed outstanding performance in discriminating LVSD among patients with HF. DeepECG-HFrEF (+) was associated with a worse 5-year survival, even when compared to using the actual EF value. To our knowledge, this is the first study to validate the performance of a deep learning-based AI algorithm for LVSD detection and to show risk predictability in symptomatic patients with HF.

LVSD is identified in 40–50% of patients with HF16. Although survival rates of patients with HF have recently improved in developed countries, patients with HF still show an eight-fold higher mortality than an age-matched population17,18. Not only does HF increase the risk of mortality, but the associated economic burden cannot be overlooked. The economic burden of HF was estimated to be $108 billion per annum globally in 2012, with 60% direct costs to the healthcare system and 40% indirect costs to society through morbidity and others19. Such burden is even higher in Asian countries compared to the United States, with a large proportion of the HF-related healthcare costs directly associated to hospitalization20. The impact of this burden is accentuated among elderly patients, with almost three-quarters of the total resources assigned to HF being solely devoted to the older population21. The increase in the proportion of elderly individuals in the general population, social ageing phenomenon, is consistent throughout the world, with the elderly population projected to double to almost 1.6 billion globally, from 2025 to 205022. Considering the economic burden of HF in the elderly population, there is a need to improve early diagnosis and treatment of LVSD to slow or even prevent its progression to HF.

A summary of currently developed AI algorithms for the detection of LVSD and the validation of these algorithms is provided in Supplementary Table S5. The definition of LVSD and the primary endpoint differed among studies, with an EF cut-off of 35% to 40% having been used. The study population used for validation also differed between the studies, from using patients at a community general hospital to patients in cardiac intensive care unit and patients with COVID-199,12,13. As a result of these differences in the clinical population used, the proportion of patients within the validation population varied between 2 and 20%7,11. Our study is the first to validate the algorithm to detect LVSD solely using patients with HF. Our results showed the strength of the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm to discriminate LVSD even when the prevalence of HF is high.

Despite recent advances in HF pharmacotherapy, the mortality and rehospitalization rates of patients with HF are still high. Therefore, the identification of high-risk patients who would benefit the most from comprehensive HF treatment is urgently required23. A few studies suggested the promising role of AI support for the early diagnosis of low EF15. Regarding AI for the detection of LVSD, only one study, by Attia et al., reported on the power of an AI algorithm to predict future LVSD development7. Our study is the first to show an association between long-term survival and LVSD of patients with HF based on an AI algorithm. Our results show that the AI algorithm can identify abnormalities in ECG before overt LVSD is observed on echocardiography.

The AI algorithms are known for being a “black box” with exact mechanism unexplainable. However, there are some ECG characteristics in the DeepECG-HFrEF (+) group which might have contributed to the prognostic performance of the algorithm. The DeepECG-HFrEF (+) group had significantly increased corrected QT intervals and increased proportions of LBBB and IVCD. A study by Lee et al. showed that LBBB and IVCD were associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and rehospitalization due to HF aggravation24. Regarding the QTc interval, a study by Park et al. showed a J-curve association between the corrected QT interval and mortality among patients with acute HF, with a nadir of 440–450 ms in men and 470–480 ms in women25. Thus, such an association might be one of the factors used by the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm to differentiate between the two groups. Nevertheless, as our study did not specifically differentiate the corrected QT interval according to sex, the application of results by Park et al. should be done with caution25. Thus, we can carefully interpret that the features shown in the DeepECG-HFrEF (+) group, such as LBBB and IVCD, might be factors that the algorithm is searching for group classification.

There is no clear explanation for the increased false-positive and false-negative rates among patients with an EF near 40%. One plausible explanation might be that the clustering near an EF of 40% may be a heterogeneous group. A previous study by Rastogi et al. showed heterogeneity in the underlying demographics of HFmrEF to be associated with changes in EF over time26. Among the HFmrEF groups, improvement in EF tends to be associated with coronary artery disease, while a worsening of EF is more likely to coexist with hypertension and diastolic dysfunction26. Patients with acute coronary syndrome are more likely to have dynamic changes in their ECGs and EF over a short period of time27,28. As ischemia was the leading cause of acute HF among patients in the KorAHF Registry, such dynamic changes might have contributed to heterogeneity, resulting in a discrepancy between actual EF and DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm results29.

Limitations

The limitations of our study need to be acknowledged in the interpretation of results. First, owing to the retrospective design used, causation between identified factors of LVSD among patients with HF could not be inferred. Further validation of the algorithm using a prospective study design is needed. Second, generalization of our results is limited, and should be cautiously interpreted, as the study population was drawn from a single hospital site in Korea. Further studies on a wider range of race and ethnicity are necessary, as done per the study conducted by the Mayo Clinic using an artificial intelligence-augmented electrocardiogram (AI-ECG) in the United States and Uganda9,14. Third, although most of the ECGs were matched to echocardiography within 24 h, some were performed within 30 days. Although these time gaps might influence the performance of our model, the mean ± standard deviation of time gaps for true positive, false positive, false negative, and true negative are 22.0 (± 65.6), 30.6 (± 86.4), 31.3 (± 107.3), and 33.6 (± 90.2), respectively, which was not statistically significant (p = 0.192). Also, the performance of the algorithm although the 30-day maximum has generally been accepted in previous studies10,12. It is important to note that the ECG matched to echocardiography within 24 h comprised 82.1% of the data used in this study. Fourth, HF medication compliance was not considered. As angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and beta-blockers are known to have a favorable prognosis for the treatment of LVSD, data on such medication adherence would have affected survival. Fifth, our study focused on the association between ECG and echocardiography and included multiple ECG and echocardiographic data from one person. This may have had a slight influence on the survival analysis. A sequential study using a single ECG and echocardiography from individual patients would be useful to confirm our results. Lastly, our study used visually estimated EF values documented by the examiners because EF measurement by Simpson’s biplane or other calculated methods were inadequate either by poor echocardiographic window or severely unbalanced myocardial contraction (61 out of 1291 cases).

Conclusions

The DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm showed acceptable performance in distinguishing HFrEF in a real-world HF cohort. Patients with a DeepECG-HFrEF (+) classification had a significantly worse 5-year survival. Application of the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm may be of specific benefit in resource-limited clinical settings where echocardiography is not readily eligible to identify high-risk patients who may benefit from active therapeutic intervention.

Methods

Statement of ethics

Our Institutional Review Boards approved this retrospective database study at Seoul National University Hospital (No.2012-191-1186). The requirement for informed consent from the study subjects was waived by the IRB of Seoul National University Hospital due to the retrospective study design. All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Use of the data from the KorAHF Registry was previously approved (Institutional Review Boards of Seoul National University Hospital No. 2004-166-1119)29.

Study population

This was a retrospective validation study of the AI ECG algorithm for patients with symptomatic HF at Seoul National University Hospital. The ECGs used to validate the DeepECG-HFrEF for the diagnosis of HFrEF were retrieved from the KorAHF Registry. Eligible were patients who had undergone ECG and echocardiography within a 30-day interval. Patients with missing demographics, ECGs, and echocardiographic information were excluded. For patients who underwent repeated ECGs and echocardiography, all records were verified, and the ECGs performed closest to (before or after) the index echocardiography selected for analysis. All ECGs included in the analysis were manually reviewed by two certified cardiologists to confirm the cardiac rhythm diagnosis.

Data management

Demographic and echocardiographic data, and clinical outcomes were obtained from the KorAHF Registry25,29. The 12-lead ECGs were performed using the MUSE system (MAC 5500 HD, versions 5D to 8, GE Healthcare), at a sampling rate of 500 Hz. The left ventricular EF was determined using the following hierarchical approach: Simpson’s biplane method was used preferentially; if this was not available, then other calculated methods were used; and finally, if EF could not be calculated, then visual estimation was used. HF was classified according to the left ventricular EF, as follows: HFrEF (EF < 40%); HF with mildly reduced EF (HFmrEF, EF: 40–50%); and HF with preserved EF (HFpEF, EF > 50%)30.

AI Algorithm

The original convolutional neural network (CNN)-based algorithm was previously described, developed, and externally validated8. The DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm to detect a LVEF < 40% was validated to detect an EF < 40% from 12-lead 10 s ECGs data of HF patients. The algorithm was implemented on the TensorFlow (Google, Mountain View, CA) framework and written in Python (version 3.6; Python Software Foundation, Beaverton, OR). For this study, the algorithm was newly implemented on PyTorch (Facebook, Menlo Park, CA), with no additional training or optimization of the original algorithm. The output for the algorithm is a continuous value between 0 and 1, representing a confidence score for an EF < 40%. Using a certain cut-off value, all tests either had a positive (+) or negative (−) result, and none of the tests were considered intermediate.

Statistical analysis

A comprehensive panel of diagnostic performance metrics was summarized to evaluate the performance of the DeepECG-HFrEF algorithm. In particular, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, accuracy, and accuracy of the validation study were determined using the original algorithm positive (+) of greater than or equal to the cut-off of 0.370, indicating that the input ECG had a confidence score of 0.370 to detect a LVEF < 40%8. The AUC with confidence interval was evaluated via a 2000-sample bootstrapping method. We examined the optimal threshold, which is defined as the threshold that maximizes the sum of sensitivity and specificity (i.e., Youden’s index). Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and compared using the unpaired Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies or percentages and were compared using the chi-squared test. For the secondary objective of exploring the long-term prognostic impact of DeepECG-HFrEF (+), the Kaplan–Meier method was used with between-group differences assessed using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional-hazards regression model was used to identify the predictors of 5-year all-cause mortality. The performance of three models was evaluated: DeepECG-HFrEF (+) model 1 (age > 70 years, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 4–5); DeepECG-HFrEF (+) model 2 (echocardiographic results of EF < 40%, age > 70 years, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and CKD stage 4–5); and DeepECG-HFrEF (+) model 3 (BNP > 500 pg/mL, age > 70 years, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and CKD stage 4–5). All reported p-values were two-sided, with a p-value < 0.05 considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the data collection, data interpretation, and literature research, and were involved in all stages of manuscript development.

Funding

No funding was received in this study. Development of the AI algorithm was supported by VUNO Inc., Seoul, Korea. JMC, GCO, HYL, SL, MC, YL have no financial conflicts of interest. All authors contributed to the data collection, data interpretation, and literature research, and were involved in all stages of manuscript development.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are all available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Figure 5, where the label of the orange-colored line in panel (b) was incorrectly given as "DeepECG HFrEF (-) among EF < 40%".

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: JungMin Choi and Sungjae Lee.

Change history

10/13/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-022-22012-7

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-18640-8.

References

- 1.McMurray JJV, et al. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction, heart failure, and the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ. Heart Fail. 2013;6:451–460. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasan RS, et al. Epidemiology of left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure in the framingham study: an echocardiographic study over 3 decades. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2018;11:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffmann R, et al. Analysis of interinstitutional observer agreement in interpretation of dobutamine stress echocardiograms. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1996;27:330–336. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonagh TA, et al. Biochemical detection of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction. Lancet. 1998;351:9–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davie AP, et al. Value of the electrocardiogram in identifying heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction. BMJ : Br. Med. J. 1996;312:222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7025.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potter EL, et al. Machine learning of ECG waveforms to improve selection for testing for asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2021;14:1904–1915. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2021.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attia ZI, et al. Screening for cardiac contractile dysfunction using an artificial intelligence–enabled electrocardiogram. Nat. Med. 2019;25:70–74. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho J, et al. Artificial intelligence algorithm for screening heart failure with reduced ejection fraction using electrocardiography. ASAIO J. 2021;67:314–321. doi: 10.1097/mat.0000000000001218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jentzer JC, et al. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction identification using artificial intelligence-augmented electrocardiogram in cardiac intensive care unit patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021;326:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adedinsewo D, et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled ECG algorithm to identify patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction presenting to the emergency department with dyspnea. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2020;13:e008437. doi: 10.1161/circep.120.008437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashou AH, et al. Artificial intelligence-augmented electrocardiogram detection of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in the general population. Mayo. Clin. Proc. 2021;96:2576–2586. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon JM, et al. Development and validation of deep-learning algorithm for electrocardiography-based heart failure identification. Korean. Circ. J. 2019;49:629–639. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2018.0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attia ZI, Kapa S, Noseworthy PA, Lopez-Jimenez F, Friedman PA. Artificial intelligence ECG to detect left ventricular dysfunction in COVID-19: a case series. Mayo. Clin. Proc. 2020;95:2464–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mondo CK, et al. External validation of an electrocardiography artificial intelligence-generated algorithm to detect left ventricular systolic function in a general cardiac clinic in Uganda. Eur. Heart J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ehjci/ehaa946.1013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao X, et al. Artificial intelligence–enabled electrocardiograms for identification of patients with low ejection fraction: a pragmatic, randomized clinical trial. Nat. Med. 2021;27:815–819. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies MK, et al. Prevalence of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure in the echocardiographic heart of England screening study: a population based study. Lancet. 2001;358:439–444. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A, Eriksson H, Lappas G. Heart failure in the general population of men—morbidity, risk factors and prognosis. J. Intern. Med. 2001;249:253–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2001.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahimi K, Duncan M, Pitcher A, Emdin CA, Goldacre MJ. Mortality from heart failure, acute myocardial infarction and other ischaemic heart disease in England and Oxford: a trend study of multiple-cause-coded death certification. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2015;69:1000–1005. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-205689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook C, Cole G, Asaria P, Jabbour R, Francis DP. The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;171:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung H, Sohn IS. Economic burden of heart failure in Asian countries based on real-world data. Korean Circ. J. 2021;51:694–695. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao L, Allen LA, Whellan DJ. Economic burden of heart failure in the elderly. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:447–462. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wan He, D. G., and Paul Kowal. An Aging World: 2015, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2016/demo/P95-16-1.html (2014).

- 23.Choi HM, Park MS, Youn JC. Update on heart failure management and future directions. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2019;34:944. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.428.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JH, et al. Prognostic implication of ventricular conduction disturbance pattern in hospitalized patients with acute heart failure syndrome. Korean Circ. J. 2019;49:602–611. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2018.0290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park CS, et al. J-curve relationship between corrected QT interval and mortality in acute heart failure patients. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2020;35:1371–1384. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2019.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rastogi A, Novak E, Platts AE, Mann DL. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical outcomes for heart failure patients with a mid-range ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017;19:1597–1605. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikus K, et al. Electrocardiographic classification of acute coronary syndromes: a review by a committee of the International society for holter and non-invasive electrocardiology. J. Electrocardiol. 2010;43:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ezekowitz JA, et al. Declining in-hospital mortality and increasing heart failure incidence in elderly patients with first myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;53:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SE, et al. A multicentre cohort study of acute heart failure syndromes in Korea: rationale, design, and interim observations of the korean acute heart failure (KorAHF) registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014;16:700–708. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu JJ, Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. Heart failure with mid-range (borderline) ejection fraction: clinical implications and future directions. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are all available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.