Abstract

Background

Coagulation dysfunction represents a serious complication in patients during the COVID-19 infection, while fulminant thrombotic complications emerge as critical issues in individuals with severe COVID-19. In addition to a severe clinical presentation, comorbidities and age significantly contribute to the development of thrombotic complications in this disease. However, there is very little data on association of congenital thrombophilia and thrombotic events in the setting of COVID-19. Our study aimed to evaluate the risk of COVID-19 associated thrombosis in patients with congenital thrombophilia.

Methods

This prospective, case-control study included patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection, followed 6 months post-confirmation. The final outcome was a symptomatic thrombotic event. In total, 90 COVID-19 patients, 30 with known congenital thrombophilia and 60 patients without thrombophilia within the period July 2020–November 2021, were included in the study. Evaluation of hemostatic parameters including FVIII activity and D-dimer was performed for all patients at 1 month, 3 months and 6 months post-COVID-19 diagnosis.

Results

Symptomatic thrombotic events were observed in 7 out of 30 (23 %) COVID-19 patients with thrombophilia, and 12 out of 60 (20 %) without thrombophilia, P = 0.715. In addition, the two patient groups had comparable localization of thrombotic events, time to thrombotic event, effect of antithrombotic treatment and changes in FVIII activity, while D-dimer level were significantly increased in patients without thrombophilia.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that patients with congenital thrombophilia, irrespective of their age, a mild clinical picture and absence of comorbidities, should receive anticoagulant prophylaxis, adjusted based on the specific genetic defect.

Abbreviations: COVID, Corona Virus Disease; VTE, Venous Thromboembolism; AT, Antithrombin; FV Leiden, Factor V Leiden; FII G20210A, Prothrombin mutation; BMI, Body Mass Index; DVT, Deep Venous Thrombosis; PE, Pulmonary Embolism; PCR/RFLP, polymerase chain reaction/restriction fragment length polymorphism; HBS, Heparin Binding Site; OR, Odds Ratio; AC, Anticoagulants; VKA, Vitamin K antagonist; DOAC, Direct Oral Anticoagulant; LMWH, Low Molecular Weight Heparin; FVIII, Factor VIII; FEU, Fibrinogen Equivalent; UT, Unusual Thrombosis; CT, Computed Tomography

Keywords: Congenital thrombophilia, COVID-19 infection, Venous thromboembolism risk

1. Introduction

Coagulation dysfunction represents a serious complication in patients with COVID-19 infection and can lead to fulminant thrombotic complications which adds to the morbidity in this patient population [1]. Based on previous studies, several changes towards the prothrombotic phenotype can be explained by the profound inflammatory response, as well as by hypoxia [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. Activation of the coagulation system caused by the presence of a novel coronavirus may result in numerous vascular complications such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) and arterial thrombosis, with significant implications on the clinical outcome for COVID-19 patients [7]. Thromboembolism significantly increases the odds of mortality in COVID-19, being as high as 74 % [8]. It should be emphasized that the severity of the clinical picture, as well as comorbidities, significantly contribute to the development of thrombotic complications. In relation to the clinical presentation, many patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) secondary to COVID-19, develop life-threatening thrombotic complications despite anticoagulation [9]. Additionally, increasing age is associated with a higher prevalence of VTE and pulmonary embolism, while increased body-mass index was only shown to be associated with increased prevalence of pulmonary embolism [10].

Thrombophilia has been hypothesized to contribute to thrombotic risk, however this hypothesis is based almost entirely on individual case reports [11], [12], [13]. To date, the largest published cohort study included 13 patients with congenital thrombophilia, and the majority of patients with severe thrombophilia did not develop symptomatic thrombotic events during COVID-19, including those with previous thrombosis. A possible explanation for the low incidence of thrombosis in COVID-19 patients with thrombophilia may relate to the fact that these patients were in fact treated with anticoagulants prior to the infection, or at the very early stages of disease [14].

Our study aimed to primarily evaluate the risk of thrombosis among COVID-19 patients with known congenital thrombophilia, and to compare their results to COVID-19 patients without thrombophilia. The secondary goal was to evaluate the effect of anticoagulant therapy in the prevention of thrombosis in these patients.

2. Materials and methods

Institutional approval for the study was granted by the Local Research Ethics Committee in accordance with the internationally accepted ethical standards. Each patient signed the informed consent form.

Patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection related to nasopharyngeal swab SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test were prospectively recruited and followed for 6 months post-COVID-19 infection. Inclusion criteria were: all patients older than 18 years of age, with known thrombophilia, who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Patients with COVID-19 infection without thrombophilia who were referred to the COVID hospital with symptoms of COVID infection, and who were confirmed positive for SARS-CoV-2 were included as a control group. The study took place in the period from July 2020 to November 2021. The data related to the period of hospitalization were obtained from the health information system of the Clinical Hospital Center “Bezanijska Kosa” (Heliant, v7.3, r48602) or from the patient discharge list and medical records. Participant data included demographic data: age, gender, BMI, comorbidities, previous thrombosis, anticoagulant status prior to COVID-19 and during the COVID-19 treatment, as well as clinical presentation of COVID-19 infection.

Thrombotic events developed during the acute COVID-19 infection, or in the following next 6 months, were defined as COVID-19 related thrombosis. In all suspected thrombotic events color Doppler or computed tomography (CT scan) were performed with the results used for the differentiation of the type and location of thrombotic events.

During the follow-up period, the laboratory evaluation of hemostatic parameters included FVIII activity and D-dimer at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months post-COVID-19 infection. Specifically, whole blood was collected into two Vacutainer citrate tubes (Vacutest; Kima, containing 1/10 volume sodium citrate stock solution at 0.129 mmol/L) using sterile, atraumatic venipuncture. Two samples were taken for each patient and prepared using the standard method to obtain platelet poor plasma, with aliquots stored at −80 °C until testing. Factor VIII:C was measured using the 1-stage clotting assay with IL test reagents (Instrumentation Laboratory, Milan, Italy), and analyses were performed using IL ACL 6000 coagulometers (Instrumental Laboratory Milano), with levels above 1.5 IU/mL considered as increased [15]. D-dimer was measured using the Innovance D-dimer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics), immunoturbidimetric assay for the quantitative determination of cross-linked fibrin degradation products (D-dimer) in human plasma using BCS Siemens coagulometer, with results expressed in mg/L FEU (fibrinogen equivalent units). The cut-off value used for discrimination of VTE was 0.5 mg/L FEU for patients under 50 years of age, while in patients older than 50 years of age adjusted D-dimer level was used.

Results of the hemostatic parameters and data related to patients with thrombophilia (genetic results and anamnestic data related to the thrombotic or anticoagulant status) were collected from the laboratory information system and thrombophilia registry.

2.1. Statistical analyses

Description of the data was performed using median and interquartile range (IQR) (for non-Gaussian data distribution) and mean and standard deviation (SD) (for Gaussian data distribution). Differences between groups were measured using the Mann-Whitney U test and Independent samples t-Test. Kaplan-Meier test was used for determination of time-to-thrombotic event estimation. Correlation between parameters was performed using the Spearman's rho test. The statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 21.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patients with congenital thrombophilia

Clinical and biological characteristics of 30 patients with COVID-19 and congenital thrombophilia are shown in Table 1 , and included 8 patients with Antithrombin (AT) deficiency. The mutations on the SERPINC1 gene that cause two types of AT deficiency, were present in an equal number in the heterozygous variant, except for one carrier of the homozygous Type II HBS deficiency. Four patients had Protein S (PS) deficiency, with the diagnosis made on the basis of functional and antigenic PS assays, without the corresponding genetic results. The prothrombotic mutations on the F5 and F2 genes were noted in 18 patients, with 12 patients being carriers of the Factor V (FV) Leiden mutation (c.1601G > A p.R534Q), 2 of which were homozygous. Three patients were carriers of the c.*97G > A heterozygous prothrombin gene mutation, with a further two being carriers of the c.1787G>A (Belgrade mutation), with one patient being a carrier of both heterozygous prothrombotic mutations, while one a carrier of the AT deficiency Type I and FV Leiden mutation (c.548Cdel, p.Ser151(183)SerfsX100, heterozygous/c.1601G>A p.R534Q). In patients with congenital thrombophilia 7 were asymptomatic carriers, while recurrent VTE was observed in 8 patients, all of whom were placed on long-term vitamin K antagonists (VKA).

Table 1.

Clinical and biological characteristics of patients with COVID-19 carrying congenital thrombophilia.

| Congenital thrombophilia | Gene | Gene variant | Age | Sex | Age of the 1st event | Recurrent VTE | AC status before COVID | COVID related VTE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antithrombin deficiency (8) | SERPINC1 | Type II HBS (4) | ||||||

| P1 | c.391 C>T, p.Leu99 (131)Phe (AT Budapest 3), homozygous | 34 | Female | 14 | Yes | VKA, long life | During COVID-19, 2 months after | |

| P2 | p.Leu99(131)Phe (AT Budapest 3), heterozygous (3) | 44 | Male | 12 | No | No | During COVID-19 | |

| P3 | 49 | Female | 32 | Yes | VKA, long life | |||

| P4 | 63 | Female | 53 | No | No | |||

| Type I (4) | ||||||||

| P5 | Deletion of exon 3 | 41 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| P6 | c.1019-1022TGGAdel, p.Leu308(340)LeufsX5, heterozygous (1) | 41 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| P7 | c.548Cdel, p.Ser151(183)SerfsX100, heterozygous/c.1601G>A p.R534Q (1) | 26 | Female | 19 | Yes | VKA, long life | ||

| P8 | c.415-416AAdel, p.Lys139(171)ValfsX16, heterozygous (1) | 28 | Female | 21 | Yes | VKA, long life | ||

| Protein S deficiency (4) | PROS1 | Missing | ||||||

| Activity | ||||||||

| P1 (35%) | 46 | Male | 27 | No | No | |||

| P2 (13%) | 33 | Female | No | No | No | |||

| P3 (39%) | 58 | Female | 38 | Yes | VKA, long life | |||

| P4 (12%) | 61 | Male | 55 | No | Aspirin | |||

| FV Leiden (12) | F5 | c.1601G>A p.R534Q | ||||||

| P1 | Heterozygous | 41 | Female | No | No | No | 3 months after | |

| P2 | Heterozygous | 40 | Male | No | No | No | During COVID-19 | |

| P3 | Heterozygous | 33 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| P4 | Heterozygous | 48 | Female | No | No | No | 5 months after | |

| P5 | Heterozygous | 34 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| P6 | Heterozygous | 36 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| P7 | Heterozygous | 63 | Female | #32 | #Yes | #VKA, long life | ||

| P8 | Homozygous | 47 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| P9 | Homozygous | 36 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| P10 | Heterozygous | 35 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| P11 | Heterozygous | 49 | Male | No | No | No | 3 months after | |

| P12 | Heterozygous | 37 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| Prothrombin (3) | F2 | c.*97G>A | ||||||

| P1 | Heterozygous | 24 | Male | No | No | No | 3 months after | |

| P2 | Heterozygous | 24 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| P3 | Heterozygous | 22 | Female | No | No | No | ||

| Prothrombin Belgrade (2) | F2* | c.1787G>A | ||||||

| P1 | Heterozygous | 45 | Female | 31 | Yes | VKA, long life | ||

| P2 | Heterozygous | 41 | Female | 27 | Yes | VKA, long life | ||

| FVLeiden/prothrombin (1) | F5/F2 | c.1601G>A p.R534Q/c.*97G>A | ||||||

| P1 | Heterozygous | 40 | Female | No | No | No |

# one patient from FV Leiden group was on long time VKA due to the recurrent thrombosis.

3.2. Case-control analysis of patients with congenital thrombophilia

Clinical features of the 30 COVID-19 patients with thrombophilia and 60 patients without thrombophilia are shown in Table 2 . The following parameters were significantly different between the two groups: age, comorbid diseases, previous thrombosis, the need for hospitalization, respiratory support and anticoagulant status prior to the COVID-19 infection. During the follow-up period, thrombotic events were observed in 7 out of 30 (23 %) patients with thrombophilia and 12 out 60 (20 %) without thrombophilia, P = 0.715. A similar distribution of thrombosis location, time to thrombotic event, and changes in FVIII activity were observed across both groups, while, D-dimer was significantly higher in patients without thrombophilia. There was a significant correlation between the VTE occurrence and FVIII function across all measurements. When it comes to D-dimer, only the measurement at one month post infection showed significant correlation with VTE (Table 3, Supplemental Data).

Table 2.

Case-control analysis of clinical features of COVID-19 patients with and without thrombophilia.

| Patient group | Age mean (SD) | Sex F/M | BMI median (IQR) | Weight overweight/obese | Comorbid disease n/N (%) |

Previous VTE n/N (%) |

COVID-19 treatment Home/hospital |

COVID-19 Clinical picture |

AC status before COVID 19 | FVIII (IU) median (IQR) 1 m 3 m 6 m |

D-dimer mg/L FEU median (IQR) 1 m 3 m 6 m |

Localization of COVID-19 related thrombosis | Time of VTE During/after |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombophilia | 40.63 (11.11) | 24/6 | 24.7 (5.6) | 9/3 | 6/30 (20) | 14/30 (47) | 29/1 | Mild 20 Pneumonia 10 Respiratory Support 0 |

VKA 7 | 1.85 (1.03) 1.55 (0.56) 1.48 (0.71) |

0.79 (1) 0.55 (0) 0.39 (0) |

DVT 5 PE 1 UT 1 |

3/4 |

| No thrombophilia | 49.47 (13.58) | 43/17 | 25.0 (6.5) | 15/8 | 31/60 (51) | 8/60 (13) | 42/18 | Mild 42 Pneumonia18 Respiratory Support *18 |

VKA 1 | 1.83 (0.8) 1.59 (0.98) 1.45 (0.78) |

0.85 (1) 0.45 (1) 0.45 (0) |

DVT 4 PE 3 DVT/PE 2 UT 3 |

1/11 |

| P value | <0.001 | 0.8 | 0.002 | 0.554 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.935 * <0.001 |

0.001 | # 0.183 & 0.123 ** 0.94 |

# 0.015 & 0.031 ** 0.003 |

0.927 | 0.117 |

F/M (female/male), BMI (body mass index-overweight BMI > 25), Obese BMI > 30, COVID (corona virus disease), AC status (anticoagulant status-use of AC drugs), m – month, FVIII (Factor VIII), FEU (fibrinogen equivalent units-0.5 mg/L cut-off value used for discrimination of VTE), m (month), UTE (unusual thrombosis), SD (standard deviation), IQR (interquartile range) * difference in relation to the respiratory support (3 patients with CT score 17 were on mechanical ventilation), difference between investigated groups in relation to the hemostatic parameters during 1 month #, 3 months & and 6 months ** of follow up.

Analysis of hemostatic parameters during the follow up shows that patients who developed thrombosis, regardless of the thrombophilia status, had a significantly higher level of FVIII compared to patients who did not develop thrombosis. In case of D-dimer, the difference was significant only at the 1 month post-infection (Table 4, Supplemental Data).

3.3. Use of antithrombotic therapy during COVID-19 infection

Eleven patients with thrombophilia and 8 without thrombophilia received oral anticoagulant therapy, which included VKA (8 with and one without thrombophilia), and DOAC (3 with thrombophilia and 5 without thrombophilia). Patients on VKA therapy were stable, with the INR level maintained in the range of 2 to 3. Patients receiving DOAC introduced during the COVID-19 infection, 8 patients received Rivaroxaban (20 mg per day), and two patients without thrombophilia received Apixaban (2 × 2.5 mg per day). From the group that was already on VKA treatment, one patient with AT deficiency developed acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT) on two occasions. The first event occurred during the acute infection, while the second recurrent event developed in the period two months after she become PCR negative for SARS-CoV-2.

Hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 infection received a high prophylactic dose of Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH), Enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously twice daily, while patients with non-severe disease received Enoxaparin 40 mg once daily. Eight patients with thrombophilia received Enoxaparin once daily, while 18 patients without thrombophilia received a high prophylactic dose of LMWH. Two patients (one patient with thrombophilia (carrier of FV Leiden mutation) and one without thrombophilia) received only one week of Enoxaparin prophylaxis, and developed thrombotic events post-COVID-19 infection. There were 3 patients without thrombophilia who presented with severe COVID-19 and who required respiratory support, that had thrombotic events within 1 to 3 months post interruption of anticoagulant therapy.

An equal number patients from both groups with a mild clinical picture received 100 mg Aspirin for one month post COVID-19 diagnosis, with one patient with thrombophilia (carrier of the FVLeiden mutation) developing a thrombotic event 5 months post-COVID-19 diagnosis.

There were 30 young patients with a mild clinical picture (4 with thrombophilia and 26 without thrombophilia) that did not receive prophylaxis. Thrombotic events developed in 3 patients with thrombophilia during acute infection (one patient with heterozygous AT deficiency type II HBS and one patient with heterozygous FV Leiden mutation). Both of these patients developed distal vein thrombosis, while the carrier of prothrombin mutation developed abdominal thrombosis (v. portae) 3 months post-COVID-19 infection. Eight patients without thrombophilia developed thrombosis, one during acute infection and 7 at 1 month to 4 months post-infection.

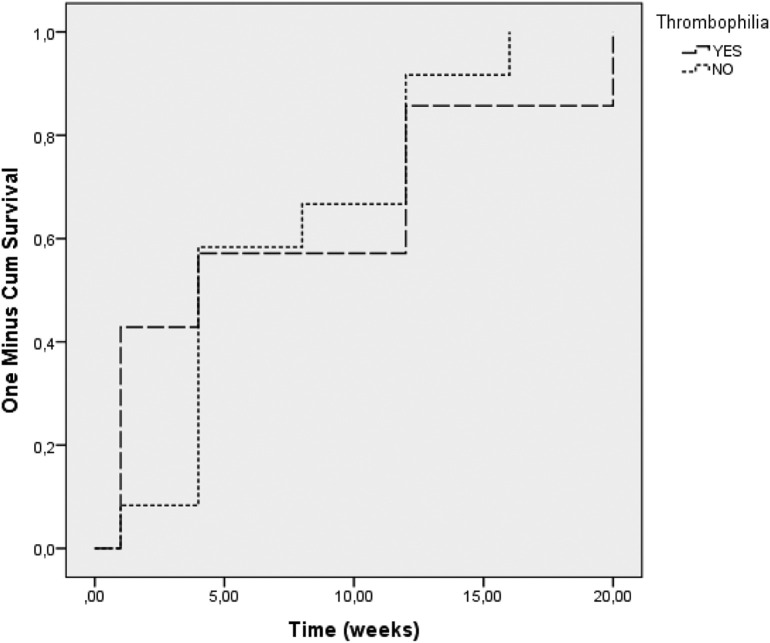

The timing of thrombotic events in relation to the COVID-19 infection across the entire cohort is shown in Fig. 1 , showing that presence of thrombophilia did not have an effect on the timing of the thrombotic event, P = 0.819.

Fig. 1.

Time of VTE occurrence depending on thrombophilia presence.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest case-control study of patients with congenital thrombophilia infected with SARS-CoV-2. The main finding was that there was an equal incidence of thrombotic events among patients with congenital thrombophilia and those without thrombophilia related to COVID-19, with the risk for VTE being present several months post SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our results confirm previous findings that low incidence of thrombosis in thrombophilia patients may be related to the fact that these patients were already treated with anticoagulants prior to the COVID-19 infection [14]. Another important reason for a comparable incidence of thrombotic events associated with COVID-19 could be linked to the younger age, a mild clinical picture and lower incidence of comorbidities in the thrombophilia group. Contrary to this, in the group without thrombophilia there was a high number of patients with comorbidities including cardiac disease, diabetes and hypothyroidism, that could significantly affect the development of a more severe clinical presentation. The fact that two patients without thrombophilia developed thrombosis one month post discharge is in accordance with previously published study describing high incidence of thrombosis in patients with severe clinical presentation [1].

According to existing guidelines, the use of LMWH is recommended for prophylaxis or treatment COVID-19 induced thrombosis [16], [17], [18], and 57 % of our patients (27 % with thrombophilia and 30 % without thrombophilia) were in fact receiving LMWH. The prophylaxis was introduced based on risk stratification and published recommendations [16] during admission to the COVID hospital, except for those who were already receiving VKA and, as expected there was a low incidence of thrombosis was observed in these patients, regardless of the thrombophilia status.

On the other hand, the majority of young patients who had a mild clinical picture received Aspirin and did not have thrombotic complications, while the remainder did not receive any antithrombotic therapy, as per recommendations. In the latter patient group, an equally high number of patients developed thrombosis, independent of the thrombophilia status.

Considering that FVIII is an acute phase reactant, there is debate as to whether increased FVIII levels in represent an increased inflammatory state [19]. We observed significantly higher FVIII levels in patients who developed thrombosis, compared to those without thrombosis. An increase in FVIII could in fact suggest hypercoagulability in patients post-COVID-19, supported by increase across both patient populations. Our results suggest that monitoring of FVIII levels could be a useful tool in assessing hypercoagulability and possible thrombotic risk, especially in patients with known thrombotic risk factors. Previous studies have shown that patients admitted to intensive care, or those with severe COVID-19 requiring respiratory support, had increased FVIII levels during the acute infection [20], [21], [22], [23]. In addition, hospitalized COVID-19 patients with increased FVIII levels, maintained a significantly higher FVIII level, compared to healthy controls 4 months post-discharge [24].

Our results related to asymptomatic young carriers of thrombophilia presenting with non-severe COVID-19 infection, who have not received any antithrombotic therapy, is consistent with recent findings of Mahmoud et al. Namely, the authors emphasize that inherited thrombophilia with endotheliopathy appears to be a plausible mechanism for thrombosis in a proportion of noncritical patients with COVID-19, without association with COVID-19 severity [25]. With this in mind, it is important that all patients with congenital thrombophilia, regardless of age, a mild clinical picture or absence of comorbidities, receive adequate prophylaxis. The type and duration of anticoagulation therapy and secondary thromboprophylaxis should be adjusted based on the specific genetic defect that causes thrombophilia. When analyzing thrombotic events in relation to the type of thrombophilia and applied prophylaxis, AT deficiency is the most severe thrombophilia in the setting of COVID-19. In patients with homozygous antithrombin Type II HBS deficiency, the risk for VTE is particularly pronounced, even in the presence of mild clinical COVID infection and absence of comorbidities [11].

The main limitation of our study is small sample size, in addition to the selection bias present due to the significant difference between investigated and control group in relation to comorbidities and clinical presentation of COVID-19 infection, as a possible risk factor for development of COVID-19 related thrombosis. Despite limitations, our study is the first prospective study representing valuable data related to thrombophilia in the setting of COVID-19 infection.

5. Conclusion

Our study showed an equal incidence of thrombotic events among patients with congenital thrombophilia and those without thrombophilia in the setting of COVID-19, and that the risk for VTE may be present for several months post-COVID-19 infection. Patients with congenital thrombophilia, regardless of the age, and in the setting of a mild clinical picture or absence of comorbidities, should receive anticoagulant prophylaxis adjusted for the specific genetic defect. Patients with homozygous AT deficiency Type II HBS were among those with the highest risk for thrombosis related to COVID-19 infection.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant 451-03-9/2021-14/200042 from the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development, Serbia.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2022.08.020.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary tables

References

- 1.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., Arbous M.S., Gommers D.A.M.P.J., Kant K.M., et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fei Y., Tang N., Liu H., Cao W. Coagulation dysfunction: a hallmark in COVID-19. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2020;144(10):1223–1229. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0324-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han H., Yiang L., Liu R., Liu F., Wu K., Li J., et al. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2020;58(7):1116–1120. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Favaloro E.J., Lippi G. Maintaining hemostasis and preventing thrombosis in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—Part III. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2022;48:3–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1736169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langer F., Kluge S., Klamroth Oldenburg J. Coagulopathy in COVID-19 and its implication for safe and efficacious thromboprophylaxis. Hamostaseologie. 2020;40:1–6. doi: 10.1055/a-1178-3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malas M.B., Naazie I.N., Elsayed N., Mathlouthi A., Marmor R., Clary B. Thromboembolism risk of COVID-19 is high and associated with a higher risk of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29:100639. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helms J., Tacquard C., Severac F., Leonard-Lorant I., Ohana M., Delabranche X., et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Minno A., Ambrosino P., Calcaterra I., Di Minno M.N.D. COVID-19 and venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis of literature studies. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2020;46(07):763–771. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1715456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovac M., Markovic O., Lalic-Cosic S., Mitic G. High risk of venous thrombosis recurrence in fully anticoagulated patient with antithrombin deficiency during COVID-19: a case report. IJCDW. 2021 doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1739129. Published online. 12-14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiore J.R., Ciarallo M., Di Stefano M., Sica S., Scarale M., Maria D’Errico M., et al. Severe systemic thrombosis in a young COVID-19 patient with a rare homozygous prothrombin G20210A mutation. Le Infezioni in Medicina. 2021;2:259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betancourt M.F., Grant K.M., Johnson J.S., Kelkar D.S., Sharma K. Positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA with significant inflammatory state and thrombophilia after 12 weeks of initial diagnosis of COVID-19 infection. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2021 Jan-Mar;13(1):42–43. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_286_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de la Morena-Barrio M.E., Bravo-Perez C., de la Morena-Barrio B., et al. A pilot study on the impact of congenital thrombophilia in COVID-19. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021;51 doi: 10.1111/eci.13546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koster T., Blann A.D., Briët E., Vandenbroucke J.P., Rosendaal F.R. Role of clotting factor VIII in effect of von Willebrand factor on occurrence of deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet. 1995;345(8943):152–155. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moores L.K., Tritschler T., Brosnahan S., Carrier M., Collen J.F., Doerschug K., Holley A.B., Jimenez D., Le Gal G., Rali P., et al. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2020;158:1143–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D., et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spyropoulos A.C., Levy J.H., Ageno W., Connors J.M., Hunt B.H., Iba T., et al. Scientific and standardization committee communication: clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18(8):1859–1865. doi: 10.1111/jth.14929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai A.W., Cushman M., Rosamond W.D., Heckbert S.R., Russell P.T., Aleksic N., et al. Coagulation factors, inflammation markers, and venous thromboembolism: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology (LITE) Am. J. Med. 2002;113(8):636–642. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahraini M., Dorgalaleh A. PhD1The impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on blood coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways: a review of prothrombotic changes caused by COVID-19. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2022;48:19–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1736166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panigada M., Bottino N., Tagliabue P., et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: a report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18(07):1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/jth.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabatabai A., Rabin J., Menaker J., et al. Factor VIII and functional protein C activity in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a case series. A A Pract. 2020;14(07) doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000001236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Meijenfeldt F.A., Havervall S., Adelmeijer J., et al. Prothrombotic changes in patients with COVID-19 are associated with disease severity and mortality. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;5(01):132–141. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Meijenfeldt F.A., Havervall S., Adelmeijer J., et al. Sustained prothrombotic changes in COVID-19 patients 4 months after hospital discharge. Blood Adv. 2021;5(03):756–759. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elbadry Mahmoud I., Tawfeek A., Abdellatif Mohammed G., Eman H., et al. Unusual pattern of thrombotic events in young adult non-critically ill patients with COVID-19 may result from an undiagnosed inherited and acquired form of thrombophilia. Br. J. Haematol. 2022;196:902–922. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables