Abstract

Extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors are a heterogeneous group of alternative sigma factors that regulate gene expression in response to a variety of conditions, including stress. We previously characterized a mycobacterial ECF sigma factor, SigE, that contributes to survival following several distinct stresses. A gene encoding a closely related sigma factor, sigH, was cloned from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis. A single copy of this gene is present in these and other fast- and slow-growing mycobacteria, including M. fortuitum and M. avium. While the M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis sigH genes encode highly similar proteins, there are multiple differences in adjacent genes. The single in vivo transcriptional start site identified in M. smegmatis and one of two identified in M. bovis BCG were found to have −35 promoter sequences that match the ECF-dependent −35 promoter consensus. Expression from these promoters was strongly induced by 50°C heat shock. In comparison to the wild type, an M. smegmatis sigH mutant was found to be more susceptible to cumene hydroperoxide stress but to be similar in logarithmic growth, stationary-phase survival, and survival following several other stresses. Survival of an M. smegmatis sigH sigE double mutant was found to be markedly decreased following 53°C heat shock and following exposure to cumene hydroperoxide. Expression of the second gene in the sigH operon is required for complementation of the sigH stress phenotypes. SigH is an alternative sigma factor that plays a role in the mycobacterial stress response.

Extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors constitute a diverse family of proteins within the ς70 class of bacterial RNA polymerase sigma subunits. This group was originally defined by conservation of sequence, and in some cases of function, of these proteins among several bacterial species (24). Many of these proteins, including those first described for Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, have been shown to play a role in the regulation of gene expression required for survival following exposure to stress (6, 9, 13, 18, 31). With the rapid expansion of bacterial genomic sequence data, it has become apparent that many bacterial species have several genes that encode ECF-type sigma factors, although in most cases the functions of these proteins have not been defined.

Because of the role of some ECF sigma factors in regulating the interaction of bacteria with the extracellular environment and in the adaptation of bacteria to stress, these proteins are of interest as potential regulators of virulence factors in bacterial pathogens. Examples of this role have been described for P. aeruginosa and Salmonella spp. (6, 11). Mycobacteria are major pathogens of humans, yet little is known regarding determinants of virulence in these organisms or the regulation of mycobacterial gene expression during infection. As a step toward determining whether sigma factor-regulated gene expression plays a role in mycobacterial pathogenesis, we have begun to examine the role of ECF sigma factors in the mycobacterial stress response.

We previously characterized a mycobacterial ECF sigma factor, designated SigE, that plays a role in bacterial survival following a variety of in vitro stresses (39). Examination of the sequence of the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv demonstrated the presence of a gene closely related to sigE. This report describes the cloning and initial characterization of this mycobacterial ECF sigma factor designated SigH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture and stress conditions.

Strains and plasmids are described in Table 1. E. coli cultures were grown on L agar or in L broth. M. smegmatis liquid cultures were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.5% albumin, 0.085% NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 80 (7H9-ADCTw). M. smegmatis was plated on Middlebrook 7H10 plates supplemented with 0.2% glucose or on L agar. Ampicillin (50 to 70 μg/ml), kanamycin (20 to 50 μg/ml), zeocin (30 μg/ml), and apramycin (30 μg/ml) were added to culture media as indicated.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| M. smegmatis | ||

| mc2-155 | High-frequency transformation strain of M. smegmatis derived from wild-type strain mc2-6 | 37 |

| RH244 | mc2-155 sigE::zeo (Zeor) [SigE−]; result of recombination of pRH1264Z into chromosome of mc2-155 | This study |

| RH280 | mc2-155 sigH::aph (Kmr) [SigH−]; result of recombination of pRH1301 into chromosome of mc2-155 | This study |

| RH296 | mc2-155 sigH::aph (Kmr) [SigH−]; independent isolate constructed in same way as RH280 | This study |

| RH315 | RH244 sigH::aph (Zeor Kmr) [SigE− SigH−]; result of recombination of pRH1317 into chromosome of RH244 | This study |

| RH328 | RH244 sigH::aph (Zeor Kmr) [SigE− SigH−]; independent isolate from RH315 | This study |

| M. bovis BCG | Pasteur strain of M. bovis BCG (attenuated strain of M. bovis) | A. Aldovini |

| E. coli | ||

| XL1-Blue MRF′ | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac[F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| Y1090 | F− Δ(lac)U169 lon-100 araD139 rpsL (Strr) supF mcrA trpC22::Tn10 (pMC9 Tetr Ampr) | 16 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript KS+ | E. coli cloning vector; Apr | Stratagene |

| pRH1264Z | Zeocin resistance gene driven by hsp70 promoter inserted into blunted BglII site of M. smegmatis sigE gene in pBluescript | This study |

| pRH1274 | 3.5-kb insert in pBluescriptKS+ containing sigH locus of M. tuberculosis H37RV isolated from genomic DNA library in λZAP | This study |

| pRH1276 | 7-kb insert in pUC19 containing sigH locus of M. smegmatis isolated from genomic DNA library in pUC19 | This study |

| pRH1301 | aph of TN903 inserted into BamHI site in coding region of M. smegmatis sigH in pRH1276; Kmr | This study |

| pJEM15 | E. coli-mycobacterium shuttle vector with promoterless lacZ gene for construction of transcriptional fusions to lacZ | 38 |

| pRH1313 | Heat-inducible promoter (MtP2) of M. tuberculosis/M. bovis BCG sigH gene cloned upstream of lacZ in pJEM15 | This study |

| pPR23 | E. coli-mycobacterium shuttle vector with sacB and temperature-sensitive mycobacterial ori; gentamicin resistant | 28 |

| pRH1317 | 2.2-kb NotI fragment of pRH1301 containing sigE::aph inserted into NotI site of pPR23 | This study |

| pMH94A | Mycobacterial integrating vector with Kmr gene replaced by apramycin resistance from pVK173T (23, 27) | This study |

| pRH1335 | pMH94A with M. smegmatis sigH coding and promoter region inserted into EcoRI site | This study |

| pRH1341 | pMH94A with M. smegmatis sigH promoter, coding region, and adjacent gene inserted into EcoRI site | This study |

Experiments to determine survival following heat shock (42 and 53°C), acid shock (50 mM citric acid and HCl at pH 4), and hydrogen peroxide exposure (5 mM) were performed in 7H9-ADCTw as previously described (39). Experiments to determine survival following exposure to reactive nitrogen intermediates generated from nitrite were performed as described elsewhere (8). Several heat shock temperatures were tested; based on initial results, 50°C was used for heat shock induction of sigH gene expression and 53°C was used to quantify differences in survival following heat shock. To determine susceptibility to cumene hydroperoxide, M. smegmatis mc2-155 was grown to log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.1 to 0.5) and then incubated in various concentrations of the reagents to determine a concentration that resulted in approximately 90% killing after 2 h. This concentration was then used for time-kill experiments in which dilutions were plated at serial time points following exposure.

As a second method to determine cumene hydroperoxide susceptibility, paper discs were impregnated with 10 μl of 40 mM cumene hydroperoxide and placed onto LB agar plates onto which approximately 106 M. smegmatis had been spread. The susceptibility of wild-type and mutant strains was determined by measuring the diameter of the zone of inhibition after 2 to 3 days of growth.

Cloning of mycobacterial sigH genes.

The following primers, based on the M. tuberculosis H37Rv sequence from cosmid MTCY7D11, were synthesized and used to amplify a 464-bp product: 5′-CTGTACGGCGGTGCGCTGCG-3′ and 5′-AAGACCGCGCAACTGACGTCG-3′. This PCR product was used to probe a M. tuberculosis genomic DNA library in λgt11 (40). A clone containing a 3.5-kb insert was obtained and verified to contain the M. tuberculosis sigH locus by restriction analysis and limited DNA sequencing. The M. tuberculosis sigH clone was used to probe an M. smegmatis genomic DNA library in pUC19 to obtain a clone containing a 7-kb insert that included the M. smegmatis sigH locus (15).

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

Lambda DNA was purified and plasmid DNA was isolated according to standard methods (34). Restriction and modifying enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs or Boehringer Mannheim. Genomic DNA from M. smegmatis, M. fortuitum, M. bovis BCG, and M. avium was purified as previously described (17). M. tuberculosis genomic DNA was obtained from Patrick Brennan and John Belisle (Colorado State University). Southern blot analysis was performed with an NEBlot Phototope kit (New England Biolabs) or with an ECL kit (Amersham), using M. tuberculosis DNA from the sigH-coding region as a probe, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequencing of the M. smegmatis sigH gene was performed on subcloned restriction fragments and by using oligonucleotide primers based on adjacent sequence. Sequencing was performed on automated DNA sequencers, using Taq dye terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), in the core sequencing facility of the Children’s Hospital Mental Retardation Research Center. Sequence assembly and analysis were performed with Sequencher (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.), the Wisconsin Package (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.), and Macvector (Oxford Molecular, Oxford, England).

Transcriptional analysis.

Primer extension was performed as previously described (39). Total RNA was isolated from M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG by the hot phenol method or by using a Fast RNA Prep kit (Bio 101) (34). Primers used to determine the sigH transcriptional start sites were 5′-GGCGTCTCGGGCTCGACCCGGTCGACGTCAG-3′ and 5′-TCGCGTCGCGCTCGAAACGCGCGGTCAACTC-3′ for M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG, respectively. Quantification of primer extension bands was performed by scanning of the film and performing densitometry with NIH Image software.

Reverse transcription (RT) of 2 μg of total mycobacterial RNA, using the primer 5′-CGCGGATCCTGGTTGTCTTCTAGCCC-3′ (underlined bases correspond to the end of the gene immediately 3′ to sigH), was performed by using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) incubated at 42°C, followed by removal of RNA by RNase H; 2 μl of this reaction mixture was used as the substrate for PCR (30 cycles of 95°C for 2 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min in a 50-μl reaction mixture with 2 mM MgCl2), using Amplitaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). For PCR, the primer 5′-TGTTTCCCACGATGACTGACG-3′, corresponding to the beginning of sigH, was used together with the primer used in the RT reaction. The expected size of the product of this reaction is 979 bp.

Construction of a transcriptional fusion of the heat-inducible sigH promoter to lacZ.

A transcriptional fusion of the heat shock-inducible promoter region of M. tuberculosis (M. bovis BCG) sigH (MtP2) to a promoterless β-galactosidase gene was constructed in the E. coli-mycobacterial shuttle vector pJEM15 (38). This promoter region was amplified by PCR using the primers 5′-CACCGGACCGCGGGACAGGC-3′ and 5′-TGCAGGTACCGAACCAATC-3′. Restriction sites incorporated into the primers are underlined. The resulting PCR products were digested with SacII plus KpnI and cloned into the corresponding sites in pJEM15 to generate pRH1313. Correct promoter sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The resulting construct incorporated 64 bp 5′ to the transcription start sites of MtP2. pRH1313 was transformed into M. smegmatis mc2-155 and M. bovis BCG to assess the activity of MtP2 in these mycobacterial species.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed as previously described (25), with the following modifications. M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG were grown to log phase (OD600 of 0.2 to 0.5), pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in Z buffer (25). The cells were then lysed by beating in a 2-ml microcentrifuge tube approximately one-fourth filled with glass beads in a Bead-Beater (Biospec Products). The cell debris was pelleted, and β-galactosidase activity was determined in the supernatant following addition of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (final concentration, 4 mg/ml) by measuring absorbance at 405 nm at 5-min intervals for 1 h. Because of the potential for variable cell lysis and less accurate correlation of OD600 with cell number in mycobacteria, β-galactosidase activity was calculated as ΔOD405 per minute per milligram of protein in the cleared cell lysate, rather than in Miller units. Protein concentrations were determined by using a NanoOrange kit (Molecular Probes). β-Galactosidase activity and protein concentration were measured in triplicate.

Construction and complementation of M. smegmatis sigH mutants.

pRH1276 was digested with BamHI, and the 1.3-kb aph (kanamycin resistance) gene of Tn903 from pUC4KSac was inserted in the same transcriptional orientation as sigH, to generate pRH1301 (1). This insertion disrupts the sigH structural gene between codons 81 and 82 of the inferred SigH protein. This suicide construct was electroporated into mc2-155; transformants were selected on kanamycin plates and then screened by PCR to distinguish single from double homologous recombination events. Two independent clones in which a double crossover had occurred were identified. The occurrence of allelic exchange resulting in a single disrupted copy of sigH in the chromosome was confirmed by Southern blotting of chromosomal DNA, and these strains were designated RH280 and RH296.

RH244 was constructed by transforming mc2-155 with pRH1264Z followed by PCR screening and Southern analysis to document gene replacement of the wild-type sigE with the zeocin-disrupted sigE, as previously described (39). To generate a sigE sigH double mutation in M. smegmatis, RH244 was transformed with pRH1317. Cells were grown at 32°C, plated on LB plates containing kanamycin and sucrose, and incubated at 39°C as described elsewhere (28). DNA from individual colonies was screened as described above. The occurrence of allelic exchange resulting in gene replacement was confirmed for two independent isolates by Southern blotting of chromosomal DNA, and the strains were designated RH315 and RH328.

For complementation experiments, a DNA fragment containing an intact copy of the M. smegmatis sigH coding and promoter regions was introduced into RH315 and RH328 by using pMH94A, a derivative of the integrating vector pMH94 in which the kanamycin resistance gene had been replaced with the apramycin resistance gene of pVK173T (23, 27). The same vector was used to introduce the sigH promoter and coding regions together with the coding sequence of the adjacent 3′ gene into RH315 and RH328.

Western blot analysis.

Lysates of M. smegmatis RH244, RH280, RH315, and mc2-155 were made following growth to log phase and 50°C heat shock. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transfer to nylon membranes were performed according to standard methods. Blots were probed with monoclonal antibody IT-41 (HAT3) directed against DnaK (Hsp70) of M. tuberculosis and known to be cross-reactive with the M. smegmatis DnaK (21). Colorimetric detection of bound antibody was performed with the Protoblot II AP system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the sigH locus of M. smegmatis has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF144091.

RESULTS

Cloning, Southern blotting, and sequence analysis of the mycobacterial sigE locus.

A BLAST search of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA sequence with the M. tuberculosis sigE sequence identified an open reading frame in the cosmid MTCY7d11 related to but distinct from sigE (4). A PCR product based on this sequence was used as a probe to isolate clones containing this putative sigma factor gene, named sigH (Rv3223c), from genomic DNA libraries of M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis (15, 40). Southern blot analysis using the coding region of the M. tuberculosis sigH gene as a probe showed that a single copy of this gene was present in M. smegmatis, M. fortuitum, M. avium, M. tuberculosis, and M. bovis BCG (not shown).

Analysis of the sigH locus in M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis revealed that the M. smegmatis deduced amino acid sequence of 216 amino acids was 89% identical to the M. tuberculosis sequence of 217 amino acids. Additional potential translational start sites using GTG as the initiation codon can be identified 5′ to those used in this analysis. However, the deduced amino acid sequences of these upstream regions in M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis are not significantly similar.

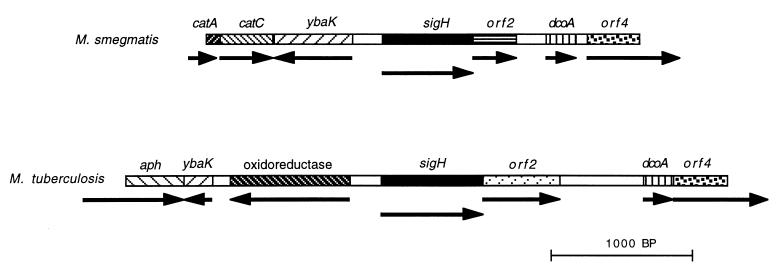

In contrast to the conserved organization of the mycobacterial sigE locus, the organization of the mycobacterial chromosome surrounding sigH differs substantially between M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis (Fig. 1). Immediately 5′ to M. smegmatis sigH is an open reading frame in the opposite transcriptional orientation that is highly similar to a gene of unknown function, designated ybaK, that is present in E. coli and several other species. Further 5′ in M. smegmatis are two open reading frames that are highly similar to catechol dioxygenase (catA) and muconolactone isomerase (catC) genes of Acinetobacter lwoffii and other species. In contrast, immediately 5′ to the M. tuberculosis sigH gene is a putative oxidoreductase gene. Further 5′ is a fragment of ybaK, followed by an open reading frame with similarity to the carboxy-terminal region of aminoglycoside phosphotransferases.

FIG. 1.

The sigH loci of M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis. The sigH genes are highly conserved, but the genes immediately downstream from sigH in these species show no similarity. There are several other differences in the organization of the flanking regions of the chromosome in these species (see text).

Immediately 3′ of M. smegmatis sigH and in the same transcriptional orientation is an open reading frame of 300 bases; the initiation codon of this putative gene overlaps the stop codon of sigH. This putative protein shows limited similarity to YbbM, a putative protein encoded by a gene immediately 3′ to the ECF sigma factor gene ybbL (sigW) of Bacillus subtilis (22). In M. tuberculosis, an open reading frame of 546 bases is similarly oriented and has an initiation codon overlapping the sigH stop codon. The deduced amino acid sequence is highly similar to that of another M. tuberculosis protein of unknown function (4). It is not similar to the M. smegmatis sequence in the corresponding location. Further 3′ to this gene are two open reading frames that encode similar proteins in M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis.

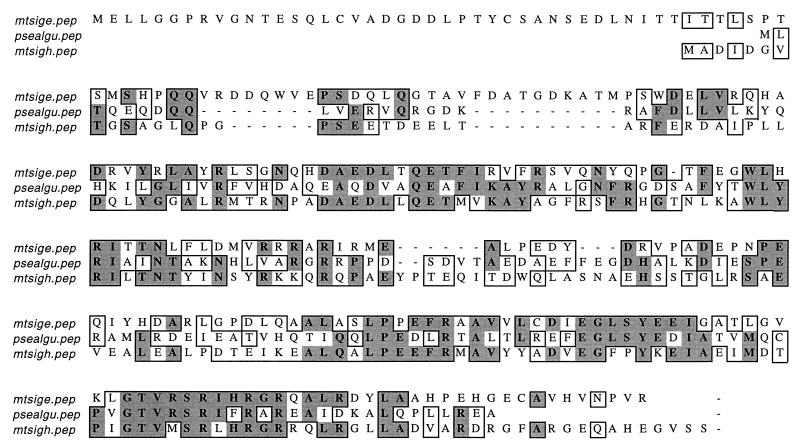

The identification of SigH as a putative ECF sigma factor is based on its sequence similarity to other known ECF sigma factors. The two most closely related sigma factors are SigE of mycobacteria and AlgU of P. aeruginosa (Fig. 2). Consistent with the conservation of −35 promoter regions in ECF-dependent promoters, the greatest proportion of conserved amino acid sequence among these proteins is in region 4.2, where M. tuberculosis SigH is 48% identical to M. tuberculosis SigE and 43% identical to P. aeruginosa AlgU. As is the case in many ECF sigma factors, SigH has a short region 1 compared to the region 1 of the primary sigma factors of most bacteria.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the inferred amino acid sequences of M. tuberculosis SigH (mtsigH.pep), P. aeruginosa AlgU (psealgu.pep), and M. tuberculosis SigE (mtsigE.pep). Identical residues are shaded. M. tuberculosis SigH is 40% identical to M. tuberculosis SigE and 26% identical to P. aeruginosa AlgU, with the greatest similarity in regions 2 and 4.

Characterization of sigH promoters in M. bovis BCG and M. smegmatis.

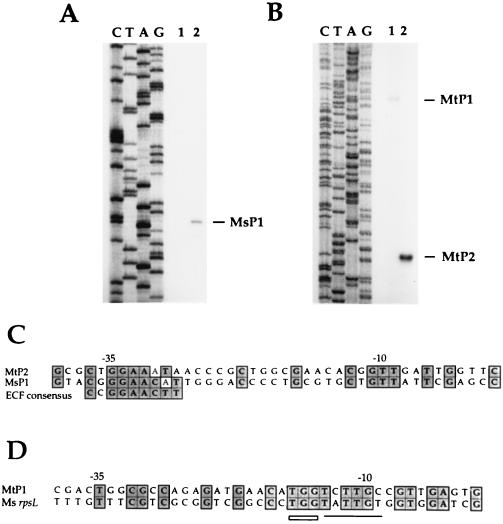

Primer extension analysis was performed to identify the promoters of the sigH genes of M. bovis BCG and M. smegmatis (Fig. 3A). For both species, a strong band identifying the 5′ end of an RNA transcript (MtP2 for M. bovis and MsP1 for M. smegmatis) was observed following heat shock. The band corresponding to this transcription start site was faintly visible in the absence of heat shock in both M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG and was induced approximately fivefold following heat shock. In M. bovis BCG but not in M. smegmatis, an additional, less intense band was seen at 37°C that decreased in intensity following heat shock (MtP1). These transcription start sites are located 163 (MsP1), 296 (MtP1), and 198 (MtP2) bases 5′ of the inferred initiation codon of sigH in M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG.

FIG. 3.

Primer extension mapping of the mycobacterial sigH transcription start sites in vivo. (A) M. smegmatis. (B) M. bovis BCG. Primer extension reactions were performed with RNA isolated after growth at 37°C (lane 1) or after 50°C heat shock (lane 2). (C) Sequence 5′ of the M. smegmatis P1 (MsP1) and the M. bovis BCG P2 (MtP2) transcription start sites compared to the ECF-dependent promoter −35 consensus sequence. (D) Sequence 5′ of the M. bovis BCG P1 transcription start site (MTP1) compared to the M. smegmatis rpsL promoter. Identical residues are shaded. The M. tuberculosis sequence 5′ of MtP1 and MtP2 is identical to that of M. bovis BCG.

Analysis of sequence 5′ to the transcription start sites revealed promoter elements related to previously identified mycobacterial promoters and to promoters of other species (Fig. 3B). The promoter region of M. bovis BCG was confirmed by direct sequencing to be identical to that of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. MtP1 is highly similar to the well-characterized rpsL promoter of M. smegmatis, a gene that is presumably transcribed by the primary mycobacterial sigma factor SigA (Fig. 3B) (20, 30). The −10 regions of these two promoters are identical in four of six positions. In addition, the MtP1 promoter matches the rpsL promoter sequence at all three positions in the extended −10 region, a region that was demonstrated to be important for optimal expression of rpsL. This extended −10 region has been observed to play an important role in efficient transcription initiation from promoters that lack −35 consensus regions (26). The MtP1 and rpsL promoters show less similarity in the −35 region.

MtP2 and MsP1, the heat shock-inducible promoters of M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis, both show substantial similarity in the −35 region to the consensus sequence of ECF sigma factor-dependent promoters (24), with seven of nine and six of nine matches, respectively. MtP2 and MsP1 are identical to each other in five of nine positions in this region. No highly conserved consensus −10 region has been defined for ECF sigma factor-dependent promoters; limited similarity of unknown significance was found in the −10 regions of MtP2 and MsP1.

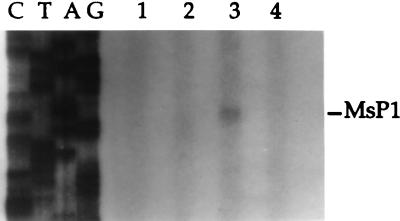

Genes encoding ECF sigma factors of other species have been shown to be autoregulated; i.e., RNA polymerase incorporating the ECF sigma factor is required for transcription of the gene encoding that sigma factor. To determine whether sigH was autoregulated, primer extension analysis was performed on RNA isolated from mc2-155 and RH280 following growth at 37°C or after 50°C heat shock (Fig. 4). No sigH transcript was visible in either strain grown at 37°C. Following heat shock, however, a transcript was present in the wild type but not in the sigH mutant. This result indicates that RNA polymerase incorporating SigH is required for transcription of sigH from MsP1 following heat shock.

FIG. 4.

Autoregulation of sigH transcription in M. smegmatis. Primer extension reactions were performed with RNA isolated from mc2-155 (lane 1) and RH280 (lane 2) after growth at 37°C and from mc2-155 (lane 3) and RH280 (lane 4) after 50°C heat shock.

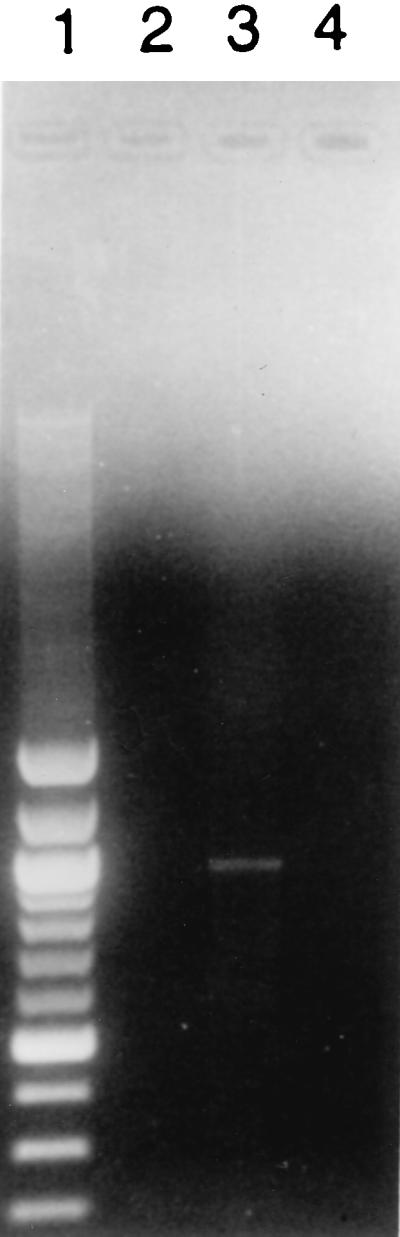

The overlap of the 3′ end of sigH and the start codon of the adjacent downstream gene suggested that these genes are part of an operon expressed from the sigH promoters identified by primer extension. RT-PCR using a pair of primers spanning this region of overlap in M. smegmatis generated a single product of the size expected for these genes to be expressed as a single mRNA transcript (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

RT-PCR of M. smegmatis RNA. Primers flanking sigH and the second gene in the operon were used to perform RT-PCR on 2 μg of M. smegmatis mc2-155 total RNA. The PCR product was electrophoresed in 1% agarose containing ethidium bromide. Lane 1, 100-bp ladder (bright bands are at 500 and 1,000 bp); lane 2, RT-PCR of RNA isolated following growth at 37°C; lane 3, RT-PCR of RNA isolated following 50°C heat shock; lane 4, PCR of RNA isolated following 50°C heat shock without an initial RT reaction. A single band of the expected size (979 bp) is seen only in lane 3, indicating that both genes are expressed from a single RNA transcript.

β-Galactosidase expression from the heat shock-inducible promoter MtP2.

The heat shock-inducible sigH promoter MtP2 identified in M. bovis BCG was cloned upstream of the promoterless β-galactosidase gene in the shuttle vector pJEM15 (38). β-Galactosidase activity from this construct was measured in M. bovis BCG and in M. smegmatis. MtP2 showed substantial activity at 37°C (10-fold greater than vector control activity) in M. bovis BCG but not in M. smegmatis. Following a 50°C heat shock, expression from MtP2 remained undetectable in M. smegmatis and declined slightly, followed by recovery to baseline or slightly higher levels in M. bovis BCG.

Analysis and complementation of M. smegmatis sigH mutants.

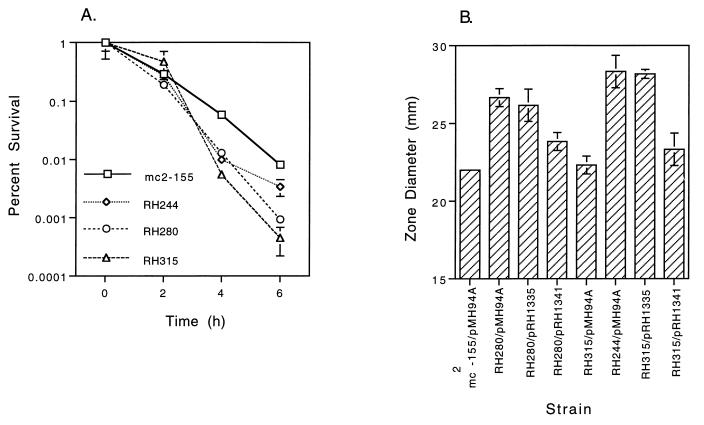

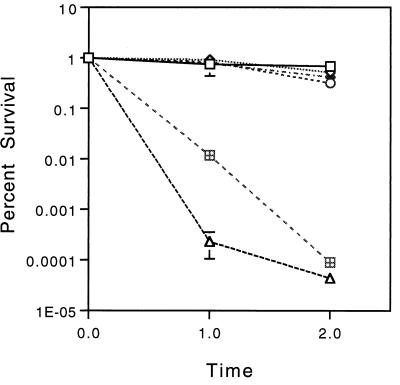

The sigH gene was disrupted by introducing the kanamycin resistance gene (aph) of Tn903 into the coding region of this gene on the chromosome of mc2-155 by allelic exchange. No differences in colony morphology were observed between the sigH mutants and the parental strain mc2-155 when plated on solid medium, and no difference in growth rate at 30 or 37°C in liquid medium was observed. No significant differences in survival were observed following several distinct stresses, including 42°C heat shock, 0°C cold shock, 50 mM citric acid stress, pH 4 HCl acid stress, exposure to 5 mM hydrogen peroxide, and exposure reactive nitrogen stress (20 mM NaNo2 incubated at pH 5.3). In addition, no difference was observed in survival during stationary phase for up to 10 days. The sigH mutant strain RH280 was substantially more susceptible to organic peroxide stress when measured by plating at serial time points following exposure, as was the sigE mutant strain RH244 (Fig. 6A). When measured by inhibition of growth around a paper disc impregnated with cumene hydroperoxide, RH280 but not RH244 was significantly more susceptible than mc2-155 (Fig. 6B). In multiple experiments, RH280 was no different from or slightly more susceptible to 53°C heat shock than the wild type, as was RH244 (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

(A) Survival of M. smegmatis mc2-155 (sigH+), RH244 (sigE), RH280 (sigH), and RH315 (sigH sigE) following exposure to 0.25 mM cumene hydroperoxide. Strains were grown at 37°C to log phase (OD600 of 0.1 to 0.5) and diluted in medium to approximately equal densities, cumene hydroperoxide was added, and dilutions were removed for plating at the indicated times. (B) Inhibition of growth of M. smegmatis strains around paper discs impregnated with 10 μl of 40 mM cumene hydroperoxide. The ability of a single copy of sigH (pRH1335) and a single copy of sigH plus the second gene in the operon (pRH1341) to complement the increased susceptibility of RH280 and RH315 was determined. The diameter of the zone of no growth surrounding the disc was measured on day 3. Each error bar represents ±1 standard deviation.

FIG. 7.

Survival of M. smegmatis mc2-155 (sigH+), RH244 (sigE), RH280 (sigH), and RH315 (sigH sigE) following 53°C heat shock. Strains were grown at 37°C to log phase (OD600 of 0.1 to 0.5), diluted in medium to approximately equal densities, and then transferred to a 53°C water bath. The ability of a single copy of sigH (pRH1335) and a single copy of sigH plus the second gene in the operon (pRH1341) to complement the increased susceptibility of RH315 was determined. Colonies were counted following 4 days of incubation. Each error bar represents ±1 standard deviation. □, mc2-155/pMH94A; ◊, RH244/pMH94A; ○, RH280/pMH94A; ▵, RH315/pMH94A; ⊞, RH315/pRH1335; ⧫, RH315/pRH1341.

Two independent sigE sigH double mutants (RH315 and RH328) were generated by disruption of sigE with a zeocin resistance gene and disruption of sigH with a kanamycin resistance gene. These strains were markedly more susceptible to 53°C heat shock than the wild type and than either the sigE or sigH single-mutant strains (Fig. 7). No difference between RH315 and mc2-155 was observed for the other stresses tested with the exception of organic peroxide exposure, where the double mutant showed significantly less survival than either single mutant and the wild type following exposure to cumene hydroperoxide (Fig. 6).

To determine whether these phenotypes were the direct result of disruption of sigH, a wild-type copy of the sigH gene and its promoter region were introduced as a single copy into RH280, RH315, and RH328. The double-mutant strains remained highly susceptible to heat shock (53°C) and exposure to cumene hydroperoxide, and there was no change in the phenotype of the sigH mutant (Fig. 6B and 7). To determine whether this lack of complementation was the result of polarity of the mutation or the disrupted sigH allele being dominant, a wild-type copy of the sigH gene and its promoter region plus the immediate downstream gene were introduced into the mutant strains. Both the heat shock and organic peroxide phenotypes of the double mutant were substantially complemented by the introduction of sigH and the downstream gene, as was the susceptibility to cumene hydroperoxide of the sigH mutant (Fig. 6B and 7). No evidence of dominance of the mutant allele was seen.

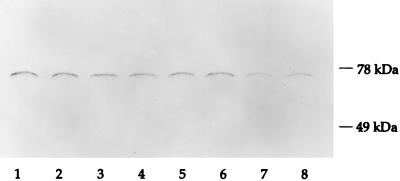

Expression of DnaK in sigE and sigH mutant strains of M. smegmatis.

Because of the apparent role of both SigE and SigH in the heat shock response, we determined whether expression of the heat shock chaperone DnaK was dependent on either of these sigma factors. Western blot analysis of lysates of mc2-155, RH244, RH280, and RH315 using the monoclonal antibody HAT3 (IT-41) (21), which recognizes an epitope present in M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis DnaK, demonstrated substantial expression of this protein in all strains, whether grown at 37°C or after 50°C heat shock, indicating that its expression is not SigE or SigH dependent (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Western blot analysis of DnaK expression in wild-type and mutant strains of M. smegmatis. Western blotting of M. smegmatis lysates was performed with the anti-mycobacterial DnaK monoclonal antibody IT-41 (HAT3). Lanes 1 and 2, RH244 (sigE); lanes 3 and 4: RH280 (sigH); lanes 5 and 6, RH315 (sigE sigH); lanes 7 and 8, mc2-155. Lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7, lysates made following growth at 37°C; lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8, lysates made following 50°C heat shock.

DISCUSSION

The initial identification of the ECF subfamily of sigma factors linked a relatively small number of alternative sigma factors in a group based on sequence similarity, conservation of −35 region sequences of ECF sigma factor-dependent promoters, and a broad definition of conserved function (24). The large number of ECF-type sigma factors identified in bacterial genomes that have been recently sequenced suggests that members of this family are likely to regulate many types of genes in response to a wide variety of conditions.

In M. tuberculosis, 10 of 13 putative sigma factors are members of the ECF subfamily (4). In addition to SigH, whose initial characterization we describe in this report, four mycobacterial sigma factors have been characterized to some extent. SigA appears to be the primary mycobacterial sigma factor (10, 30). SigB is highly similar to SigA but is nonessential and plays a role in the response to stress (10). SigE is widely distributed in mycobacterial species and plays a role in survival following stress (39). SigF is present only in species of the M. tuberculosis complex and is expressed in response to stress and starvation (5).

The results presented here indicate that SigH, like SigE, is present in fast- and slow-growing mycobacteria and plays a role in the bacterial stress response. The induction of transcription following heat shock suggests that genes regulated by SigH may be important in the heat shock response of mycobacteria. The absence of a difference in survival of the sigH mutant compared to wild-type M. smegmatis following 42°C heat shock and the small difference following 53°C heat shock is surprising in this regard. In the context of these phenotypes, the strong induction of sigH transcription suggests the presence of multiple mechanisms for the response to heat shock in mycobacteria.

This interpretation is supported by the expression of the heat shock chaperone DnaK in single- and double-mutant strains as well as in the wild type. The presence of multiple, possibly overlapping, responses to high temperature heat shock is also supported by the much greater susceptibility to heat shock of the sigE sigH double mutant compared to either single mutant. Overlap of gene regulation by ECF sigma factors has been found recently in B. subtilis, where for four different genes, RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing either SigW or SigX was shown to initiate transcription from the same promoter (13, 14).

The second stress for which SigH appears to be important in mycobacterial survival is oxidative stress from exposure to organic peroxide. Increased killing following exposure to cumene hydroperoxide of the sigH mutant, and to a lesser extent the sigE mutant, relative to the wild type, and greater susceptibility of the sigE sigH double mutant, suggests the presence of protective mechanisms mediated by each of these two sigma factors. The lack of altered susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide of the sigH mutant or of the sigE sigH double mutant relative to wild type indicates that the responses in M. smegmatis to these oxidative stresses differ. Differences in both phenotype and protein expression of mycobacteria following responses to these different peroxides have been noted previously (7, 32, 36). Greater susceptibility of mycobacteria to organic hydroperoxide than to hydrogen peroxide could result from the large lipid content of the mycobacterial cell wall that may be subject to peroxidation by these organic reagents. The lipid-rich mycobacterial cell wall may also act as a barrier to the effects of water-soluble hydrogen peroxide.

Both sigH and the adjacent 3′ gene were found to be required for complementation of sigH mutant stress phenotypes in M. smegmatis. The expression of these genes as a single transcript from the autoregulated sigH promoter indicates that this gene, like sigH itself, is dependent on SigH for its expression. While it is possible that this gene encodes a protein that functions in a direct protective role against these stresses, the near-complete complementation of two distinct phenotypes is more consistent with the product of this gene functioning to regulate the expression of other gene products, either directly or as a positive regulator of SigH activity. The latter mechanism is well described for the regulation of alternative sigma factor activity in B. subtilis, where activities of the stress-responsive SigB and the sporulation-specific SigF are both regulated through interactions of positive and negative regulators (12, 35).

The sigH MtP1 promoter is of interest in the context of what is currently known of mycobacterial promoters. Its −10 region is highly similar to the well-characterized rpsL promoter of M. smegmatis and to the consensus −10 region identified in several putative promoters identified in M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis (2, 20). Of the two bases in the MtP1 −10 hexamer that diverge from this consensus, one is at the second position, where C is present in the place of the highly (>90%) conserved A. This divergence from the consensus may account for the weak signal observed in the primer extension experiments. Like the rpsL promoter, MtP1 lacks a −35 region that matches known consensus −35 sequences, a finding typical of the majority of mycobacterial promoters (2). MtP1 does have the extended −10 TGN motif that plays an important role mycobacterial rpsL transcription as well as in E. coli and other species in promoters lacking consensus −35 elements (19, 29, 33). This extended −10 region appears to be relatively common among mycobacterial promoter sequences, occurring in more than 20% of those identified (3).

The −35 elements of MsP1 and MtP2 are highly similar and match closely the ECF consensus. Like previously defined ECF-dependent promoters, MsP1 and MtP2 lack consensus −10 elements. The similarity between regions 4.2 of the mycobacterial SigH proteins and this region in AlgU and other ECF sigma factors supports the importance of the −35 element in transcription initiation. The nature of the two promoters identified in M. bovis BCG suggests (i) transcription from MtP1 by RNA polymerase containing the primary sigma factor SigA and (ii) expression from MtP2 mediated by RNA polymerase incorporating SigH.

While SigH proteins of M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis are highly similar and have similar −35 promoter elements, several results suggest that they may have different functions or regulation. The lack of activity of the MtP2-lacZ transcriptional fusion in M. smegmatis, both at 37°C and after heat shock is surprising given its activity at 37°C in M. bovis BCG. While differences in activity of other promoters between these species has been noted, most mycobacterial promoters that are active in one species are active in the other (2, 38). The differences in the −35 regions of these promoters may be sufficient to account for the difference in activity of the two promoters in M. smegmatis and in M. bovis BCG.

The second observation that suggests different functions for sigH in M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis is the marked difference in the organization of the chromosome adjacent to sigH in these species. Of particular interest is the gene immediately 3′ to sigH. Our data indicate that this gene plays an important role in the SigH-mediated stress response in M. smegmatis. The absence of sequence similarity in the corresponding gene in M. tuberculosis makes it unlikely that this gene has a similar role in this species.

Taken together, functional data for M. smegmatis and the sequence and transcriptional analyses of both species suggest a model in which sigH is nonessential and is expressed at low levels under nonstressed conditions. Following stress, e.g., heat shock, transcription of sigH and its adjacent 3′ gene is markedly increased. Autoregulation of the inducible sigH promoter provides a positive feedback mechanism for rapidly increasing the amount of SigH present in the cell in response to stress. At least in M. smegmatis, the second gene in the sigH operon is essential for the sigH-mediated stress response.

Our data do not exclude the formal possibility that this second gene is solely responsible for the phenotypes of the mutant strains as well as for the autoregulation of the sigH promoter. However, a model in which this gene acts as a positive regulator of SigH function, for example, through direct interaction with SigH, is consistent with our data as well as with known mechanisms for the regulation of sigma factor activity. Alternatively, the product of this gene could directly regulate the expression of genes involved in the mycobacterial stress response. Whether the unrelated gene in the corresponding position in the M. tuberculosis has a similar function remains to be determined, as does the mechanism by which heat shock is transduced into activation of transcription from the inducible mycobacterial sigH promoters.

SigH, like SigE and SigF, plays a role in the mycobacterial stress response. The presence of multiple mechanisms for the regulation of stress responses is consistent with the need for the bacteria to adapt to a variety of stresses during extracellular growth and after uptake by macrophages during the course of infection. The major stresses with which M. tuberculosis must contend are those encountered during the course of infection. Thus, sigma factors that regulate gene expression in response to stress response are likely to play an important role in regulation of gene expression that is essential for M. tuberculosis pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-37901 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by a grant from the World Health Organization Vaccine Research and Development Program. S.G. was supported by a student intern award from the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation.

Monoclonal antibody IT-41 (HAT3) was obtained from the UNPD/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. We thank John Belisle and Patrick Brennan for M. tuberculosis genomic DNA and Eric Rubin for helpful discussions.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

During review of this article, we became aware of a report in which M. tuberculosis sigH transcription was shown to be induced following heat shock (R. Manganelli, E. Dubnau, S. Tyagi, F. R. Kramer, and I. Smith, Mol. Microbiol. 31:715–724, 1999).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barany F. Single-stranded hexameric linkers: a system for in phase insertion mutagenesis and protein engineering. Gene. 1985;37:111–123. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bashyam M, Kaushal D, Dasgupta S, Tyagi A. A study of the mycobacterial transcription apparatus: identification of novel features in promoter elements. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4847–4853. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4847-4853.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashyam M, Tyagi A K. Identification and analysis of “extended −10” promoters from mycobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2568–2573. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2568-2573.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMaio J, Zhang Y, Ko C, Young D, Bishai W. A stationary-phase stress-response sigma factor from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2790–2794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deretic V, Schurr M, Boucher J, Martin D. Conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to mucoidy in cystic fibrosis: environmental stress and regulation of bacterial virulence by alternative sigma factors. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2773–2780. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2773-2780.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhandayuthapani S, Zhang Y, Mudd M, Deretic V. Oxidative stress response and its role in sensitivity to isoniazid in mycobacteria: characterization and inducibility of ahpC by peroxides in Mycobacterium smegmatis and lack of expression in M. aurum and M. tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3641–3649. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3641-3649.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrt S, Shiloh M, Ruan J, Choi M, Gunzburg S, Nathan C, Xie Q-W, Riley L. A novel antioxidant gene from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1885–1896. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.11.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson J, Gross C. Identification of the ςE subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: a second alternative ς factor involved in high temperature gene expression. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1462–1471. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez M, Doukhan L, Nair G, Smith I. sigA is an essential gene in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:617–628. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guiney D, Fang F, Krause M, Libby S, Buchmeier N, Fierer J. Biology and clinical significance of virulence plasmids in Salmonella serovars. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(Suppl. 2):S146–S151. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.supplement_2.s146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haldenwang W. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang X, Decatur A, Sorokin A, Helmann J. The Bacillus subtilis ςX protein is an extracytoplasmic function ς factor contributing to survival at high temperature. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2915–2921. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2915-2921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang X, Fredrick K, Helmann J. Promoter recognition by Bacillus subtilis ςW: autoregulation and partial overlap with the ςX regulon. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3765–3770. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3765-3770.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Husson R, James B, Young R. Gene replacement and expression of foreign DNA in mycobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:519–524. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.519-524.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huynh T, Young R, Davis R. Constructing and screening cDNA libraries in λgt10 and λgt11. In: Glover D, editor. DNA cloning. Vol. 1. Oxford, England: IRL Press; 1985. pp. 49–78. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs W, Jr, Kalpana G, Cirillo J, Pascopella L, Snapper S, Udani R, Jones W, Barletta R, Bloom B. Genetic systems for mycobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:537–555. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04027-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keiichiro H, Amemura M, Nashimoto H, Shinagawa H, Makino S. The rpoE gene of Escherichia coli, which encodes ςE, is essential for bacterial growth at high temperature. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2918–2922. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2918-2922.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keilty S, Rosenberg M. Constitutive function of a positively regulated promoter reveals new sequences essential for activity. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:6389–6395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenney T, Churchward G. Genetic analysis of the Mycobacterium smegmatis rpsL promoter. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3564–3571. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3564-3571.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khanolkar-Young S K H, Andersen A B, Bennedsen J, Brennan P J, Rivoire B, Kuijper S, McAdam K P W J, Abe C, Batra H V, Chaparas S D, Damiani G, Singh M, Engers H D. Results of the third immunology of leprosy/immunology of tuberculosis antimycobacterial monoclonal antibody workshop. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3925–3927. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3925-3927.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero M G, Bessieres P, Bolotin A, Borchert S, Borriss R, Boursier L, Brans A, Braun M, Brignell S C, Bron S, Brouillet S, Bruschi C V, Caldwell B, Capuano V, Carter N M, Choi S K, Codani J J, Connerton I F, Danchin A, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–56. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee M, Pascopella L, Jacobs W, Jr, Hatfull G. Site-specific integration of mycobacteriophage L5: integration-proficient vectors for Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and bacille Calmette-Guerin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3111–3115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lonetto M, Brown K, Rudd K, Buttner M. Analysis of the Streptomyces coelicolor sigE gene reveals the existence of a subfamily of eubacterial RNA polymerase ς factors involved in the regulation of extracytoplasmic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7573–7577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minchin S, Busby S. Location of close contacts between Escherichia coli RNA polymerase and guanine residues at promoters either with or without consensus −35 region sequences. Biochem J. 1993;289:771–775. doi: 10.1042/bj2890771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paget E, Davies J. Apramycin resistance as a selective marker for gene transfer in mycobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6357–6360. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6357-6360.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelicic V, Jackson M, Reyrat J-M, Jacobs W J, Gicquel B, Guilhot C. Efficient allelic exchange and transposon mutagenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10955–10960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ponnambalam S, Webster C, Bingham A, Busby S. Transcription initiation at the Escherichia coli galactose operon promoters in the absence of the normal −35 region sequences. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:16043–16048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Predich M, Doukhan L, Nair G, Smith I. Characterization of RNA polymerase and two sigma factor genes from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:355–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raina S, Missiakas D, Georgopoulos C. The rpoE gene encoding the ςE (ς24) heat shock sigma factor of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1995;14:1043–1055. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosner J, Storz G. Effects of peroxides on susceptibilities of Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium smegmatis to isoniazid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1829–1833. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabelnikov A G, Greenberg B, Lacks S. An extended −10 promoter alone directs transcription of the DpnII operon of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Mol Biol. 1995;250:144–155. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt R, Morgolis L, Duncan R, Coppolecchia D, Moran C, Jr, Losick R. Control of developmental transcription factor ςF by sporulation regulatory proteins SpoIIAA and SpoIIAB in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9221–9225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherman D, Khisimuzi M, Hickey M, Arain T, Morris S, Barry III C, Stover C. Compensatory ahpC gene expression in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1996;272:1641–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snapper S, Melton R, Mustafa S, Kieser T, Jacobs W., Jr Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1911–1911. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timm J, Lim E, Gicquel B. Escherichia coli-mycobacterial shuttle vectors for operon and gene fusions to lacZ: the pJEM series. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6749–6753. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6749-6753.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Q-L, Kong D, Lam K, Husson R. A mycobacterial extracytoplasmic function sigma factor involved in survival following stress. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2922–2929. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2922-2929.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young R, Bloom B, Grosskinsky C, Ivanyi J, Thomas D, Davis R. Dissection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens using recombinant DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2583–2587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]