Abstract

We previously cloned a genomic DNA fragment from the serogroup O11 Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA103 that contained all genes necessary for O-antigen synthesis and directed the expression of serogroup O11 antigen on recombinant Escherichia coli and Salmonella. To elucidate the pathway of serogroup O11 antigen synthesis, the nucleotide sequence of the biosynthetic genes was determined. Eleven open reading frames likely to be involved in serogroup O11 O-antigen biosynthesis were identified and are designated in order as wzzPaO111 (wzz from P. aeruginosa serogroup O11), wzxPaO11, wbjA, wzyPaO11, wbjB to wbjF, wbpLO11 and wbpMO11 (wbpL and wbpM from serogroup O11). Consistent with previous descriptions of O-antigen biosynthetic gene loci, the entire region with the exception of wbpMO11 has a markedly reduced G+C content relative to the chromosomal average. WzyPaO11 shows no significant similarity at the protein or DNA sequence level to any database sequence and is very hydrophobic, with 10 to 12 putative transmembrane domains, both typical characteristics of O-antigen polymerases. A nonpolar chromosomal insertion mutation in wzyPaO11 in P. aeruginosa PA103 confirmed the identity of this gene. There is striking similarity between WbjBCDE and Cap(5/8)EFGL, involved in type 5 and type 8 capsule biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. There is nearly total identity between wbpMO11 and wbpMO5, previously shown by others to be present in all 20 P. aeruginosa serogroups. Using similarity searches, we have assigned functions to the proteins encoded by the PA103 O-antigen locus and present the potential steps in the pathway for the biosynthesis of P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 O antigen.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that expresses a number of virulence factors. One of these factors, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), is the immunodominant antigen responsible for serogroup specificity. The LPS is composed of three parts: lipid A, embedded in the membrane; a core oligosaccharide; and the variable O antigen (also called B-band LPS), composed of repeating oligosaccharide units that extend out from the cell surface. There are 20 different serogroup antigens of P. aeruginosa that differ in their monosaccharide composition and/or linkages between sugar residues. P. aeruginosa has an additional rhamnan-containing polysaccharide component, termed common antigen (also referred to as A-band LPS) (21).

P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 has one of the simplest O-antigen structures (22): [-3)–α-l-FucNAc–(1-3)–β-d-FucNAc–(1-2)–β-d-Glc-(1-)]. Serogroup O11 strains are common in the environment and in hospital outbreaks and have recently been shown to exhibit multidrug resistance (13, 48). The serogroup O11 strain PA103 has been used for identification and characterization of numerous virulence factors and in animal and tissue culture models of infection (20, 29, 40, 50). We previously reported the cloning of the O-antigen locus of P. aeruginosa PA103 and the surface expression of P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 antigen on Escherichia coli (16). In a mouse model, oral vaccination with an attenuated Salmonella typhimurium strain expressing P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 has been shown to protect against oral challenge with a P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 strain (33).

The biosynthetic pathway for the production of LPS is complex. Genes for synthesis of the lipid A, LPS core, and O side chain components are often found in separate regions of the chromosome. The genes encoding the enzymes for the synthesis of O antigen (previously referred to as rfb genes) are usually clustered and may form an operon. It is interesting that the G+C content of these regions is often significantly lower than that of the rest of the chromosome, suggesting that genes for O-antigen synthesis may have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer from organisms with a lower G+C content. O-antigen synthesis involves a number of genes encoding products for the production of nucleotide sugar precursors, for the transfer of the sugars into the O-antigen polymer, and for the linkage of the O-antigen unit onto the LPS core to form the complete LPS (36).

One of the final steps in the synthesis of full-length O antigen is the polymerization of individual O-antigen subunits by O-antigen polymerase, encoded by the wzy (previously referred to as rfc) gene. Inactivation of the wzy gene results in a strain wherein the LPS core is capped with a single O-antigen unit. This phenotype is referred to as semirough or core-plus-one. In general, all wzy genes have the following characteristics: a lower G+C content and skewed codon bias compared to the rest of the chromosome (although it may be similar to other linked genes involved in O-antigen synthesis) and a gene product that is predicted to be highly hydrophobic, with 11 to 13 transmembrane domains. It is interesting that even with these similarities, there is no obvious homology between wzy genes from different organisms or from different families of serogroups from the same organism. In P. aeruginosa, the wzy gene of strain PAO1 (serogroup O5) was identified by complementation of the serum-sensitive (i.e., killed in the presence of 10% normal human serum) phenotype of the core-plus-one mutant of PAO1, AK1401 (7). We and others noted the low G+C content of this gene, the hydrophobic nature of the inferred amino acid sequence, the potential transmembrane regions, and the distribution of this gene only in strains that share a structurally related O-repeat backbone (7, 10). In this report, we present the nucleotide sequence analysis of the O-antigen gene locus from P. aeruginosa PA103. We recognized 11 open reading frames (ORFs) and confirmed that one of them corresponds to the O-antigen polymerase. On the basis of similarities to other gene products involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis, we propose a pathway for the synthesis of P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 O antigen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Luria (L) broth or agar was used for routine growth of bacteria. Cetrimide agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) was used as a selective medium for P. aeruginosa. Minimal medium (18) with glucose (20 mM), supplemented with tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan (1 mM each) as required, was used for determination of auxotrophy in P. aeruginosa. The media contained ampicillin (50 to 100 μg/ml), carbenicillin (250 μg/ml), gentamicin (15 μg/ml for E. coli; 250 μg/ml for P. aeruginosa), tetracycline (10 μg/ml for E. coli; 70 to 100 μg/ml for P. aeruginosa), sucrose (5% wt/vol), isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 40 μg/ml), and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal; 40 μg/ml) as required.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PA103 | IATS serogroup O11 | 25 |

| PAO1 | IATS serogroup O5 | 23 |

| AK1401 | O-antigen polymerase mutant of PAO1, LPS core-plus-one O-antigen subunit | 3 |

| AK44 | LPS-specific-bacteriophage-resistant mutant of PAO1, LPS complete core | 23 |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA | Gibco BRL |

| SM10 | thi-1 thr leu tonA lacY supE recA RP4-2-Tc::Mu, Kmr | 45 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEX100T | Mobilizable, counterselectable gene replacement vector; Apr/Cbr, sucrose susceptible | 43 |

| pUCGM | Contains aacC1; Apr, Gmr | 42 |

| pUCP18/19 | High-copy-number E. coli/P. aeruginosa shuttle vectors; Apr/Cbr | 41 |

| pMO012437 | Contains DNA from the 39-min region of PAO1 in the broad-host-range cosmid pLA2917 | 35 |

| pMO011618 | Contains DNA from the 40-min region of PAO1 in the broad-host-range cosmid pLA2917 | 35 |

| pLAFR1 | Broad-host-range cosmid; Tcr | 14 |

| pLPS2 | pLAFR1 containing an approximately 26.2-kb DNA fragment from P. aeruginosa PA103 encompassing the serogroup O11 O-antigen gene cluster | 16 |

| pLPS224 | pLAFR1 harboring an approximately 2.4-kb Asp718I-HindIII fragment from pLPS2 containing the wbpLO11 gene | 12 |

| pGEM226 | pGEM3 (Promega Corp.) harboring an approximately 4.4-kb NsiI-EcoRI fragment derived from pLPS2; contains the 3′ end of wbpLO11, tRNA-asnV, tyrB, and wbpMO11 | This study |

| pCF100 | pGEM226 EcoRI-NcoI deletion derivative; contains tRNA-asnV and tyrB | This study |

| pCF101 | pEX100T harboring an approximately 1.6-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pCF100; contains tyrB | This study |

| pCF102 | pCF101 containing the aacC1 gene from pUCGM, inserted into the unique XhoI site in tyrB | This study |

| pCD100 | pUCP19 harboring an approximately 3.5-kb Asp718I-XhoI fragment derived from pLPS2 encompassing wzyPaO11 | This study |

| pCD101 | pCD100 with the aacC1 gene from pUCGM inserted into the unique BssHII site in wzyPaO11 | This study |

| pCD102 | pEX100T harboring an approximately 4.7-kb PvuII fragment derived from pCD101, encompassing wzyPaO11::aacC1 | This study |

| pCD103 | pUCP18 harboring a 2.2-kb EcoRI-Asp718I fragment derived from pCD100 containing wzyPaO11 | This study |

DNA manipulations.

Plasmid DNA was isolated with Wizard Plus Minipreps (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) or plasmid kits (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). Genomic DNA was isolated by the method of Woo et al. (51) or with the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.). Restriction endonucleases and modification enzymes (Boehringer Mannheim Corp., Indianapolis, Ind.) were used as specified by the manufacturer.

Plasmids were introduced into E. coli as previously described (8). The plasmids were transformed into P. aeruginosa by the electroporation protocol of Smith and Iglewski (47). Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed as previously described (8). Following agarose gel electrophoresis, DNA fragments were isolated with the QIAquick or QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen) as specified by the manufacturer. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed on a RAGE apparatus (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) as previously described (15).

For Southern blots, restriction endonuclease-digested genomic DNA was separated on 0.7% agarose gels and transferred to a GeneScreen (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.)-charged nylon membrane as previously described (17) or with the Vacugene XL vacuum blotting system (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) as directed by the manufacturer. DNA probe labelling, hybridization, and detection were carried out with the ECL direct nucleic acid labelling and detection system (Amersham Life Science, Cleveland, Ohio) as specified in the protocol provided with the kit. For Southern blotting after PFGE, plasmid DNA was labelled with 32P by nick translation and used as a probe.

Oligonucleotide primers used in PCR and nucleotide sequence determinations were purchased from the Great American Gene Co. or Ransom Hill (Ramona, Calif.). PCR was performed with the EasyStart PCR Mix-in-a-Tube (Molecular Bio-Products, Inc., San Diego, Calif.) and a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR System 2400 thermocycler as specified by the manufacturer. Nucleotide sequence determinations of both strands of plasmid pLPS2 insert DNA were carried out by the Molecular Medicine Unit at Beth Israel Hospital (Boston, Mass.) and the Biomolecular Research Facility (University of Virginia). The sequence upstream of wzzPaO11 (wzz from P. aeruginosa serogroup O11), including himD, was obtained from a PCR fragment amplified from P. aeruginosa PA103 chromosomal DNA. Nucleotide sequence fragments were assembled and analyzed with the Sequencher (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.), Gene Inspector (Textco Corp., West Lebanon, N.H.), and GCG version 9 (Genetics Computer Group, Inc., Madison, Wis.) computer programs. GenBank database searches (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md.) were conducted by the FASTA search protocol of Pearson and Lipman (32).

In vitro mutagenesis and gene replacement.

A nonpolar mutation of wzyPaO11 was constructed in vitro by insertion of a gentamicin resistance gene (aacC1), recovered as an 879-bp SmaI fragment from plasmid pUCGM, into the unique BssHII site (rendered blunt) in wzyPaO11 on plasmid pCD100. wzyPaO11::aacC1 was then recovered from the resultant plasmid (pCD101) as an approximate 4.7-kb PvuII fragment and ligated to SmaI-digested pEX100T. This construct (pCD102) was introduced into the mobilizing E. coli strain SM10, and SM10(pCD102) was conjugated with P. aeruginosa PA103 by pelleting approximately equal numbers of donor (grown overnight at 37°C) and recipient (grown overnight without shaking at 42°C) strains in microcentrifuge tubes and spotting them onto the center of an L agar plate. After incubation for 12 to 18 h at 37°C, the cells were resuspended in 1 ml of L broth and plated on gentamicin-containing cetrimide plates. Colonies arising after 48 h were purified on the same medium and then swabbed onto L agar plates containing both gentamicin and sucrose. Since pEX100T contains the sacB gene, which renders gram-negative bacteria sensitive to sucrose, colonies arising on sucrose- and gentamicin-containing plates carried wzyPaO11::aacC1 on the chromosome and had lost the vector-associated sacB gene. These colonies were tested for sensitivity to carbenicillin to confirm the loss of vector DNA. Gene replacement was further confirmed by PCR amplification of chromosomal DNA with primers flanking the aacC1 insertion site in wzyPaO11. The PCR product from P. aeruginosa PA103 wzyPaO11::aacC1, estimated by agarose gel electrophoresis, was larger than that generated from wild-type chromosomal DNA by an amount consistent with the size of the aacC1 gene. Southern blot analysis of Asp718I-digested chromosomal DNA from the mutant and wild-type strains with wzyPaO11 as the probe showed a similar increase in hybridizing-band size for the mutant strain.

For disruption of tyrB on the chromosome, an approximately 1.6-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pCF100, containing the tyrB gene, was excised, rendered blunt, and ligated to pEX100T. The resulting construct (pCF101) was linearized at the unique XhoI site within tyrB, and rendered blunt; into it was ligated the SmaI fragment containing the gentamicin resistance gene from pUCGM, to yield pCF102. Plasmid pCF102 was introduced into the mobilizing E. coli strain SM10, and conjugation and gene replacement into P. aeruginosa strains PA103 and PAO1 were carried out as described above.

Isolation of LPS.

P. aeruginosa LPS was isolated as previously described (8) or by the proteinase K digestion method of Hitchcock and Brown (19), followed by hot-phenol extraction with slight modifications. Briefly, cells grown overnight on L agar plates with appropriate antibiotics were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6. Cells from 4.5 ml of the suspension were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in 200 μl of lysis buffer (2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 4% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, and 0.002% bromophenol blue in 1 M Tris [pH 6.8]), and boiled for 15 min. The lysed cells were treated with RNase and DNase for 30 min at 37°C and digested for 3 h at 59°C with 120 μg of proteinase K. The digested lysates were then extracted with an equal volume of 90% phenol for 15 min at 65°C with periodic vortexing. After centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at maximum speed for 10 min, both the aqueous and phenol layers were transferred to new tubes and extracted with 1 ml of diethyl ether. The aqueous layers from these extractions were removed, pooled, and again extracted with hot phenol. The aqueous layer (blue) was again extracted with 1 ml of ether and centrifuged, and the LPS-containing aqueous layer was diluted 1:3 with fresh lysis buffer and used for Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) analysis.

Tricine-SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblotting.

LPS samples were separated by Tricine-SDS-PAGE, as previously described (8), on 17% (37.8:1 acrylamide-bis-acrylamide) running gels. LPS was visualized by silver staining with a silver-staining kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) as specified by the manufacturer. After separation by Tricine-SDS-PAGE, LPS was transferred to a NitroBind nitrocellulose membrane (Micron Separations Inc., Westboro, Mass.) by using the Trans-Blot semidry electrophoretic transfer cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories) as specified by the manufacturer.

Western immunoblot analyses were performed as previously described (8). The antibodies used were monoclonal antibody (MAb) specific to P. aeruginosa O11 or O5 LPS (Rougier Bio-Tech Ltd., Montreal, Quebec, Canada), common antigen-specific MAb N1F10 (purchased from J. S. Lam, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada), or polyclonal antisera to P. aeruginosa O11 or O5 LPS (34). The blots were developed at room temperature with anti-mouse immunoglobulin M–alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim Corp., Indianapolis, Ind.) for the MAb and anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G–alkaline phosphatase (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) for the polyclonal antisera. Sigma Fast 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium tablets (Sigma Chemical Co.) were used as the alkaline phosphatase substrate as specified by the manufacturer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence from himD to tyrB appears in the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ nucleotide sequence data libraries under accession no. AF147795.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mapping of the O-antigen gene locus.

PFGE was used to map the 26.2-kb fragment of PA103 DNA that was previously shown to encode all the genes necessary for P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 O-antigen synthesis to the P. aeruginosa chromosome. PFGE maps of strain PA103 and two other strains have been compared with the physical map of strain PAO1 (44). SpeI-digested fragments from P. aeruginosa PA103 and PAO1 were separated by PFGE and probed with pLPS2. The probe hybridized to the largest SpeI fragment (585 kb) in strain PA103 and to a fragment of approximately 260 kb in strain PAO1. The 260-kb SpeI fragment of PAO1 has been mapped to 39 to 40 min on the physical linkage map of the chromosome (35). To determine whether pLPS2 hybridized to the same region of the chromosome in strain PA103 and PAO1, defined cosmid clones (pMO012437 from the 39-min region and pMO011618 from the 40-min region of PAO1 [35]) were used to probe PFGE-separated fragments of both strains. The cosmid clones hybridized to the appropriate SpeI fragment in PAO1 (400 and 260 kb, respectively) and to the largest SpeI fragment in PA103, thus indicating that the O-antigen locus of PA103 is in the 39- to 40-min region of the P. aeruginosa chromosome, the same region to which the PAO1 O-antigen locus has been previously localized (7, 24).

Sequence analysis of the P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 O-antigen genes and predicted proteins.

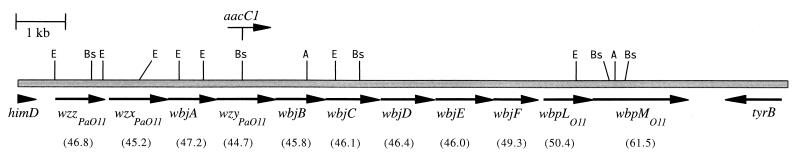

Figure 1 shows the P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 O-antigen biosynthetic gene cluster. The O-antigen locus consists of 11 potential ORFs all transcribed in the same direction and residing between the housekeeping genes himD and tyrB, essentially the same location as the previously described serogroup O5 O-antigen locus of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (4). However, all serogroup O11 ORFs appear to be involved in O-antigen biosynthesis, unlike the serogroup O5 locus, where the hisH and hisF genes and the insertion element IS1209 were found within the O-antigen gene cluster (4). O-antigen gene clusters typically have a G+C content more than 10% lower than the chromosomal average of the organism (36). Consistent with this observation, all of the serogroup O11 O-antigen genes, with the exception of wbpM from serogroup O11 (wbpMO11), have G+C contents (Fig. 1) at least 10% lower than the P. aeruginosa chromosomal average of 65 to 67 mol% (7, 30, 49).

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 strain PA103 O-antigen biosynthetic gene cluster. The numbers in brackets indicate the G+C content of each gene in moles percent. The site of insertion of the Gmr determinant (aacC1) in wzyPaO11 is shown. The arrows represent the limits of each ORF and the predicted direction of transcription. A, Asp 718I; Bs, BssHII; E, EcoRI.

The best results of comparisons of each deduced serogroup O11 O-antigen biosynthetic protein against protein databases by using the FASTA search strategy (32) are summarized in Table 2. Of the 11 identified ORFs, 10 are predicted to encode proteins with significant similarities to bacterial proteins previously found to be involved in synthesis of surface polysaccharides, including LPS O antigens of gram-negative bacteria and capsular polysaccharides of gram-positive bacteria.

TABLE 2.

P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 strain PA103 O antigen biosynthetic proteins: properties and similarities to database sequencesa

| Protein | Size (aab/kDa) | Similar proteins | % identity (expectation value) | Putative function | Database accession no.c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WzzPaO11 | 345/38.5 | WzzPaO5 (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) | 41 (3.8 × 10−53) | O-antigen chain length determinant | U50397 |

| WzzE (Salmonella typhimurium) | 21 (0.18) | O-antigen chain length determinant | O33789 (SP) | ||

| WzzE (Escherichia coli) | 23 (0.45) | O-antigen chain length determinant | P25905 (SP) | ||

| CpsC (partial) (Streptococcus pneumoniae) | 31 (0.6) | Capsule polysaccharide chain length determinant | AF030373 | ||

| Wzb8 (Escherichia coli) | 20 (0.66) | O-antigen chain length determinant | O33953 (SP) | ||

| WzxPaO11 | 411/44.3 | RfbX (Escherichia coli) | 26 (7.8 × 10−26) | O-antigen transporter | P37746 (SP) |

| Wzx (Yersinia enterocolitica) | 22 (4.1 × 10−18) | O-antigen transporter | S51260 (PIR) | ||

| mth347 (Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum) | 26 (6.5 × 10−18) | O-antigen transporter | AE000819 | ||

| RfbX (Shigella dysenteriae) | 23 (4.4 × 10−15) | O-antigen transporter | Q03583 (SP) | ||

| mth367 (Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum) | 23 (3.6 × 10−11) | O-antigen transporter | AE000822 | ||

| EpsK (Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris) | 20 (9.4 × 10−8) | Similar to O-antigen transporter | U93364 | ||

| Cap8K (Staphylococcus aureus) | 22 (6.4 × 10−6) | Capsule synthesis | U73374 | ||

| WbjA | 334/37.8 | PhcG024 (Pyrococcus horikoshii) | 25 (2.8 × 10−9) | Hypothetical protein | AB009478 |

| PmHAS (Pasteurella multocida) | 27 (3.4 × 10−7) | Hyaluronan synthase (glycosyltransferase) | AF036004 | ||

| AmsB (Erwinia amylovora) | 29 (2.3 × 10−5) | Amylovoran biosynthesis (glycosyltransferase) | Q46632 (SP) | ||

| PssI (Rhizobium leguminosarum) | 24 (2.4 × 10−5) | Glycosyltransferase | AF028810 | ||

| PssH (Rhizobium leguminosarum) | 23 (6.4 × 10−5) | Glycosyltransferase | AF028810 | ||

| WzyPaO11 | 411/46.0 | ||||

| WbjB | 344/38.6 | Cap8E (Staphylococcus aureus) | 68 (2.2 × 10−92) | Capsule biosynthesis | U73374 |

| Cap5E (Staphylococcus aureus) | 67 (5.5 × 10−92) | Capsule biosynthesis | U81973 | ||

| Protein D homolog (Methanococcus jannaschii) | 40 (1.5 × 10−44) | Homolog of capsular biosynthetic protein D | D64432 (PIR) | ||

| FlaA1 (Helicobacter pylori) | 39 (2.4 × 10−43) | Flagellin synthesis | AE000595 | ||

| FlaA1 (Caulobacter crescentus) | 39 (3.2 × 10−43) | Flagellin synthesis | U27301 | ||

| YpqP (partial) (Bacillus subtilis) | 41 (2.2 × 10−21) | Similar to capsule biosynthetic protein | P54183 (SP) | ||

| YodU (Bacillus subtilis) | 50 (3.8 × 10−21) | UDP-glucose epimerase | AF015775 | ||

| WbjC | 372/41.4 | Hypothetical protein (Acholeplasma laidlawii) | 47 (4.6 × 10−72) | Probable nucleotide binding protein | S33518 (PIR) |

| Cap8F (Staphylococcus aureus) | 42 (2.0 × 10−62) | Capsule biosynthesis | U73374 | ||

| Cap5F (Staphylococcus aureus) | 42 (4.5 × 10−62) | Capsule biosynthesis | U81973 | ||

| PhaM009 (Pyrococcus horikoshii) | 23 (2.2 × 10−5) | Vi polysaccharide biosynthesis | AB009524 | ||

| Nse (Aquifex aeolicus) | 26 (0.0076) | Nucleotide sugar epimerase | AE000735 | ||

| WbjD | 376/42.8 | Cap5G (Staphylococcus aureus) | 54 (2.4 × 10−81) | Capsule biosynthesis | U81973 |

| Cap8G (Staphylococcus aureus) | 54 (3.7 × 10−81) | Capsule biosynthesis | U73374 | ||

| BplD homolog (Methanococcus jannaschii) | 31 (3.8 × 10−38) | LPS biosynthesis | G64487 (PIR) | ||

| Mth837 (Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum) | 33 (2.2 × 10−33) | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-2-epimerase | AE000860 | ||

| Ph1617 (Pyrococcus horikoshii) | 34 (1.7 × 10−31) | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-2-epimerase | AP000006 | ||

| WbpI (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) | 30 (3.7 × 10−30) | LPS biosynthesis-epimerase | U50396 | ||

| WbjE | 400/44.6 | Hypothetical protein (Synechocystis sp.) | 25 (3.8 × 10−19) | Hypothetical protein | D90901 |

| Cap5L (Staphylococcus aureus) | 25 (1.3 × 10−18) | Capsule biosynthesis | U81973 | ||

| Cap8L (Staphylococcus aureus) | 25 (1.5 × 10−18) | Capsule biosynthesis | U73374 | ||

| BplE (Bordetella pertussis) | 23 (4.1 × 10−8) | Glycosyltransferase involved in LPS biosynthesis | S70676 (PIR) | ||

| WbpJ (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) | 21 (5.7 × 10−8) | LPS biosynthesis-transferase | U50396 | ||

| WbjF | 314/34.5 | WbpK (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) | 52 (1.2 × 10−64) | LPS biosynthesis-dehydratase | U50396 |

| GalE (Vibrio cholerae) | 40 (2.9 × 10−43) | UDP-glucose-4-epimerase | Q56623 (SP) | ||

| ORF35x7 (Vibrio cholerae) | 43 (5.4 × 10−43) | LPS biosynthesis | Y07788 | ||

| WbiG (Burkholderia pseudomallei) | 39 (4.9 × 10−35) | Epimerase/dehydratase | AF064070 | ||

| HpnA (Zymomonas mobilis) | 28 (5.8 × 10−13) | Biosynthesis of hapanoid sugar side chains | AJ001401 | ||

| Cap8N (Staphylococcus aureus) | 28 (5.7 × 10−11) | Capsule biosynthesis | U73374 | ||

| Cap5N (Staphylococcus aureus) | 33 (6.7 × 10−11) | Capsule biosynthesis | U81937 | ||

| WbpLO11 | 341/37.2 | WbpLO5 (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) | 65 (5.8 × 10−144) | LPS biosynthesis-glycosyltransferase | U50396 |

| WbcO (Yersinia enterocolitica) | 53 (8.4 × 10−73) | Glycosyltransferase (LPS biosynthesis) | S51265 (PIR) | ||

| Llm (Staphylococcus aureus) | 27 (7.7 × 10−20) | Involved in methicillin resistance/autolysis | A55856 (PIR) | ||

| TagO (Bacillus subtilis) | 25 (2.2 × 10−19) | Und-P N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (teichoic acid biosynthesis) | AJ004803 | ||

| WbiH (Burkholderia pseudomallei) | 35 (5.1 × 10−18) | Und-P N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase | AF064070 | ||

| WbpMO11 | 665/74.5 | WbpMO5 (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) | 96 (2.7 × 10−259) | LPS biosynthesis-epimerase | U50396 |

| Orf10 (Vibrio cholerae) | 50 (1 × 10−58) | Epimerase/dehydratase | U47057 | ||

| WbcP (Yersinia enterocolitica) | 49 (1.6 × 10−57) | Galactose modification (LPS biosynthesis) | S51266 (PIR) | ||

| Orf3 (Neisseria meningitidis) | 46 (1.2 × 10−53) | Documentation withdrawn | AF014804 | ||

| RfbU (Vibrio cholerae) | 47 (2.6 × 10−52) | Mannosyltransferase | Y07788 | ||

| LpsB2 (Rhizobium etli) | 49 (7.8 × 10−42) | dTDP-glucose-4,6-dehydratase | U56723 | ||

| WlbL (Bordetella pertussis) | 46 (1.8 × 10−36) | LPS biosynthesis | S70683 | ||

| WbiI (Burkholderia pseudomallei) | 40 (6 × 10−29) | Putative epimerase/dehydratase | AF064070 | ||

| CapD (Staphylococcus aureus) | 40 (6.6 × 10−29) | Capsule biosynthesis | P39853 | ||

| Cap5D (Staphylococcus aureus) | 39 (7 × 10−28) | Capsule biosynthesis | U81973 | ||

| Cap8D (Staphylococcus aureus) | 38 (1.3 × 10−27) | Capsule biosynthesis | U73374 | ||

| Protein D homolog (Methanococcus jannaschii)d | 42 (9.7 × 10−21) | Homolog of capsular biosynthetic protein D | D64432 (PIR) | ||

| YpqP (partial) (Bacillus subtilis)d | 43 (7.9 × 10−12) | Similar to capsule biosynthetic protein | P54183 (SP) | ||

| FlaA1 (Caulobacter crescentus)d | 32 (3.9 × 10−11) | Flagellin synthesis | U27301 | ||

| WbjB (Pseudomonas aeruginosa)d | 31 (1.5 × 10−9) | AF147795 (this study) | |||

| Cap8E (Staphylococcus aureus)d | 32 (2.6 × 10−8) | Capsule biosynthesis | U73374 |

Nonredundant database searched 8 August 1998.

aa, amino acids.

SP, Swiss-Prot; PIR, Protein Identification Resource.

Aligns over the C-terminal half of WbpM.

O-antigen transport and assembly genes: wzz, wzx, and wzy.

The deduced amino acid sequence of wzzPaO11 has about 41% identity to WzzPaO5 of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and 21 and 23% identity to WzzE of Salmonella typhimurium and E. coli, respectively, which suggests that this gene encodes the P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 O-antigen chain length determinant (Table 2). At the nucleotide level, wzzPaO11 and wzzPaO5 have 55% identity. WzzPaO11 has an overall hydrophilic character but does exhibit strong predicted transmembrane regions at both the N and C termini, characteristic of Wzz proteins in general (5) and suggesting that they are localized to the inner membrane. Using TnphoA, Morona et al. (28) have shown that the cloned Shigella flexneri Wzz is an integral membrane protein whose central hydrophilic portion is located in the periplasmic space, where it is proposed to interact with the O-antigen polymerase (Wzy) and/or ligase (WaaL) proteins. Burrows et al. (5) have disrupted the wzz genes in P. aeruginosa serogroup O5 and O16 strains, resulting in an altered distribution of O-antigen chain lengths. They also showed that wzzPaO5 could regulate the chain length of the heterologous O antigen of Shigella dysenteriae, extending previous observations that Wzz proteins are not O-antigen specific (1, 2, 5).

The deduced amino acid sequence of wzxPaO11 is 26% identical to E. coli RfbX (Wzx) and 22% identical to the Yersinia enterocolitica Wzx proteins (Table 2), suggesting that wzxPaO11 encodes the P. aeruginosa O11 O-antigen transporter (flippase). As is characteristic of flippases in general, WzxPaO11 is very hydrophobic (grand average of hydropathicity [GRAVY] = 1.084) and exhibits 11 or 12 potential transmembrane domains. Wzx proteins are involved in the transport of completed O-antigen subunits across the inner membrane; disruption of wzx in E. coli led to the accumulation of undecaprenol phosphate (Und-P)-linked O subunits in the cytoplasm (26). Of particular note, WzxPaO11 shows 22% identity to Cap8K (Table 2), which is proposed to be a transporter of type 8 capsule polysaccharide in Staphylococcus aureus. This sequence similarity may reflect the presence of a common fucosamine disaccharide residue in the S. aureus capsule and the P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 O antigen.

A gene within the sequence of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 O-antigen gene locus, wbpF, was recently reanalyzed and found to be the serogroup O5 O-antigen transporter; it was therefore redesignated wzx (6). WbpF did not appear in a FASTA search comparing WzxPaO11 to the database; similarly, this newly recognized protein showed no significant similarity to WzxPaO11.

The wzyPaO11 gene had no significant homology at either the DNA or protein sequence level to any sequence deposited in the databases that were searched. The predicted protein is very hydrophobic (GRAVY = 1.067) and has 10 or 12 predicted transmembrane domains. The distribution of the transmembrane domains is similar to that in the previously described WzyPaO5, the serogroup O5 O-antigen polymerase (7).

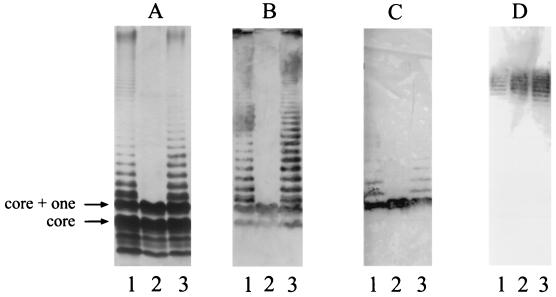

Since the putative WzyPaO11 protein shows no significant homology to database sequences, nonpolar insertional inactivation of wzyPaO11 was undertaken to verify its function. P. aeruginosa PA103 wzyPaO11::aacC1 cells produce a truncated LPS consisting of the core substituted with one O-antigen repeating unit, which is indicative of an inability to polymerize O-antigen repeating units (Fig. 2A to C, lanes 2). The presence of one repeating unit indicates that O-antigen subunit synthesis is unaffected by disruption of wzyPaO11. Restoration of full-length LPS production by plasmid-borne wzyPaO11 (lanes 3) confirmed both the role of Wzy in polymerizing O-antigen subunits and the nonpolarity of the gentamicin resistance determinant inserted into the wzy gene in P. aeruginosa PA103 wzyPaO11::aacC1. Thus, wzyPaO11 encodes the serogroup O11 antigen polymerase. Consistent with observations of wzyPaO5 mutants (10), interruption of wzyPaO11 does not affect production of the d-rhamnan common antigen (Fig. 2D), indicating that WzyPaO11 plays no apparent role in synthesis of this component of the LPS.

FIG. 2.

Effect of wzy on LPS biosynthesis. (A) Silver-stained Tricine-SDS-PAGE gel. (B) Western immunoblot obtained with serogroup O11-specific polyclonal serum. (C) Western immunoblot obtained with serogroup O11-specific MAb. (D) Western immunoblot obtained with the common antigen-specific MAb, N1F10. Lanes: 1, PA103; 2, PA103 wzyPaO11::aacC1; 3, PA103 wzyPaO11::aacC1(pCD103). The positions of the core and core-plus-one O-antigen repeating units (arrows) are shown.

It is characteristic of O-antigen polymerases that they exhibit little or no homology to one another (27), except in cases where different serogroup O antigens form a chemically and structurally related family (11). This is not surprising since they are involved in recognizing and polymerizing different polysaccharide subunits that define structurally distinct O antigens. The observed lack of sequence homology between the Wzy proteins of P. aeruginosa PA103 (serogroup O11) and PAO1 (serogroup O5), whose O antigens are structurally dissimilar, supports the notion that the differences in sequence reflect substrate specificity. What is less clear is why the proteins differ so completely in primary structure when their function and probably their structure are conserved. Whether this difference reflects the involvement of most of the primary amino acid sequence in direct interaction with different cognate substrates and/or specific transport and assembly proteins that may have coevolved or is an indication that the wzy genes are each acquired from evolutionarily distant sources (and therefore even the structurally and functionally conserved regions could differ substantially in primary structure) remains to be seen. The latter case is in keeping with the proposed idea that serogroup-specific O antigen genes in general may often be acquired, at least in part, from distantly related organisms (see below).

In view of the apparent unrelatedness of WzyPaO11 and WzyPaO5, these proteins would not be expected to be functionally interchangeable. Indeed, plasmid pCD103, containing wzyPaO11 gene, complements P. aeruginosa PA103 wzyPaO11::aacC1 (Fig. 2) but does not complement the P. aeruginosa PAO1 serogroup O5 O-antigen polymerase mutant, AK1401, as determined by Western immunoblotting. When plasmid pCD103 was reisolated from strain AK1401(pCD103), it could still restore full-length LPS production in PA103 wzyPaO11::aacC1, confirming the integrity of plasmid pCD103 in strain AK1401 (data not shown). This indicates that the Wzy proteins probably need to maintain overall structural similarities but must use their primary amino acid sequence to recognize and polymerize their cognate O-antigen subunits.

O-antigen biosynthetic genes, wbjA to wbjF, wbpLO11, and wbpMO11.

The deduced amino acid sequence of the wbjA gene shows significant similarity to various glycosyltransferases (Table 2). The protein is generally hydrophilic (GRAVY = −0.228), but there are one or two potential transmembrane domains.

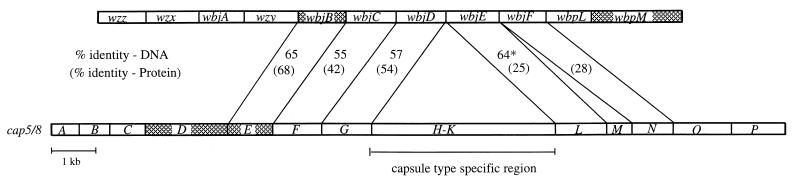

The deduced amino acid sequences from wbjB, wbjC, wbjD, and wbjE exhibit close identity to amino acid sequences corresponding to proteins involved in the synthesis of Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharides (Table 2). The S. aureus type 5 and type 8 capsule biosynthetic loci are composed of 16 ORFs denoted cap5/8A to cap5/8P (transcribed in that order) (39) (see Fig. 3). Two regions, composed of cap5/8A to cap5/8G and capL to capP, are essentially identical between the two capsule loci, with nucleotide sequence identities ranging from 97.4 to 99.7%. Flanked by these two common regions, Cap5H to Cap5K contain no significant identity to their Cap8H to Cap8K counterparts and are considered to be the capsule type-specific regions of each of these strains (39).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the serogroup O11 O-antigen synthesis genes of P. aeruginosa PA103 (top) and type 5/8 capsular polysaccharide synthesis genes of S. aureus (bottom) (GenBank accession no. U73374 and U81973). The identity at both the DNA and protein levels is indicated. Where there are slight differences between type 5 and 8 homologies, the identity with the best expectation value is used (Table 2). The capH to capK genes are capsule type-specific genes that are not homologous and differ slightly in total size. The asterisk indicates identity cap5L over a 100-bp overlap. The shaded areas represent homologies as follows: WbpM is approximately 39% identical to Cap5D and 31% identical to WbjB; Cap5E is 37% identical to Cap5D.

WbjB is 68 and 67% identical to the Cap8E and Cap5E proteins, respectively. WbjC is 47% identical to a putative nucleotide binding protein described in Acholeplasma laidlawii; however, it is also clearly related to Cap8F and Cap5F (42% identity for each). WbjD is related to Cap5G and Cap8G (54% identity for each). WbjE has 25% identity to three proteins, Cap5L, Cap8L, and a hypothetical protein from Synechocystis sp. (Table 2).

The relatedness of WbjB to WbjE to components involved in S. aureus capsule synthesis is also evident at the nucleotide level (Fig. 3), with wbjB being approximately 65% identical to cap8E, wbjC being approximately 55% identical to cap8F, and wbjD being approximately 57% identical to cap5/8G. While wbjE does not have significant overall identity to cap5/8L to cap5/8P does appear on a FASTA nucleotide database search with 64% identity over a 100-nucleotide overlap (expectation = 0.04).

The deduced amino acid sequence of wbjF shows the strongest similarity to WbpK from P. aeruginosa PAO1 (52% identity) and UDP-glucose-4-epimerase (GalE) from Vibrio cholerae (40% identity) (Table 2). WbjF also exhibits less, but still significant, relatedness to Cap5/8N from S. aureus. At the nucleotide level, wbjF exhibits 57% identity to wbpK.

WbjF and WbpMO11 (described below), are similar to Cap5/8N and Cap5/8D (and Cap5/8E in the C-terminal portion), respectively, which are common to both S. aureus capsule types. These similarities (and those of WbjB to WbjE, described above) suggest that the structures of serogroup O11 O antigen and the S. aureus type 5 and type 8 capsular polysaccharides should have a common constituent. In fact, all three structures share α-l-FucNAc–(1-3)–β-d-FucNAc as a major component of their overall structures (22, 39).

The deduced amino acid sequence of WbpLO11 shows high identity to WbpLO5 from P. aeruginosa PAO1 (65%) and WbcO from Y. enterocolitica (53%) (Table 2). There is also significant identity with the Und-P N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase TagO from Bacillus subtilis (25%) and WbiH from Burkholderia pseudomalleii. At the nucleotide level, wbpLO11 shows significant identity to both wbpLO5 (61%) and wbcO (60%).

Both WbpLO5 and WbcO are thought to initiate O-antigen subunit synthesis by adding FucNAc to the lipid carrier Und-P, after which the remaining sugars of the O antigen subunit are processively added (4, 46). Like the other proposed initiating glycosyltransferases, WbpLO11 is highly hydrophobic, having a GRAVY of 0.844 and possessing 9 to 11 predicted transmembrane domains. The likely integration of WbpLO11 in the inner membrane suggests a role in anchoring O-antigen subunit synthesis to the membrane and possible association with the O-antigen transporter that would translocate the completed O-antigen units across the inner membrane to be polymerized.

The similarity between WbpLO11 and WbpLO5 suggested that these two proteins may be functionally interchangeable. Supporting this, plasmid pLPS224 (12), containing wbpLO11, was able to complement the serogroup O5 LPS defect in the P. aeruginosa PAO1 mutant strain AK44 (data not shown), an LPS-deficient mutant (23) previously used to identify the wbpLO5 gene from strain PAO1 (9). Moreover, previous work from our laboratory showed that pLPS224 also complements unknown mutations in certain P. aeruginosa O-antigen-deficient strains (isolated from the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis) to restore the expression of serogroup O6 and O9 LPS (12). Consistent with the observed sequence similarity between WbpLO11 and WbpLO5 and the functional interchangeability of the wbpL gene, an internal probe derived from wbpLO11 hybridized with genomic DNA from all 20 P. aeruginosa serogroup strains under low-stringency conditions (data not shown).

While the nature of the mutation in AK44 is not known, it affects only O-antigen expression while leaving common antigen expression intact (9). In contrast, insertional mutagenesis of wbpLO5 to create a null mutation abolished the expression of both antigens, leading the authors to suggest that WbpLO5 is involved in initiation of synthesis of both common and O-antigen repeating units in serogroup O5 strain PAO1 (38).

In the serogroup O5 sequence reported, an insertion element, IS1209, was found between wbpL and wbpM, and it was suggested that this insertion element represents the junction between “serogroup-specific” and “nonspecific” regions of O-antigen gene clusters in P. aeruginosa (4). However, no insertion elements were found in the PA103 serogroup O11 O-antigen locus.

The wbpMO11 gene sequence and its deduced amino acid sequence are virtually identical to those of wbpMO5 described in P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Table 2). Southern blot analysis with a wbpMO11 internal fragment as probe has confirmed that this gene is common to all 20 P. aeruginosa serogroup strains, a homology also noted by Burrows et al. (4). WbpMO11 shows extensive identity to the ORF10 product (epimerase/dehydratase) of V. cholerae (50%) and WbcP of Y. enterocolitica (49%), involved in the synthesis of serotype O:3 LPS outer core. As is the case for many of the serogroup O11 O-antigen biosynthetic proteins (described above), WbpMO11 also shows significant similarity to non-serotype-specific proteins involved in S. aureus capsule synthesis, particularly CapD (Table 2). The presence of FucNAc in the structures of S. aureus type 5 and 8 capsules, Y. enterocolitica outer core, and many of the P. aeruginosa O antigens suggests that CapD, WbcP, and WbpMO11 may all function in the synthesis of this residue. Indeed, Skurnik et al. (46) speculate that WbcP is involved in the biosynthesis of GalNAc or FucNAc. Burrows et al. (4) also suggest that the WbpM proteins of P. aeruginosa are involved in making either GalNAc or FucNAc, found in nearly all of the 20 serogroup LPS structures. For serogroup O5 LPS, they propose that WbpM converts UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-GalNAc, which is subsequently processed to UDP-FucNAc by WbpK and WbpB (4). Sau et al. (39) suggest that CapD is an epimerase or dehydratase involved in synthesis of d-FucNAc and that it works in conjunction with other non-serotype-specific Cap proteins in the synthesis of the fucosamine disaccharide common to both type 5 and type 8 capsule structures. WbpMO11 may function similarly in conjunction with the above-described WbjB to WbjE proteins (showing extensive homology to Cap proteins [see above]) to synthesize the same disaccharide in the O11 O-antigen subunit.

Consistent with observations reported for WbcP (46), the proteins showing homology to WbpMO11 fall into two distinct groups (Table 2). The first contains proteins with a size similar to WbpMO11 (665 amino acids) that exhibit strong predicted transmembrane helices within approximately the first 200 amino acids. The second group of proteins are approximately half the size of WbpMO11 or less and show significant identity to the C-terminal half of WbpMO11 (Table 2). Most of these proteins are involved in sugar processing, with the exception of Caulobacter crescentus FlaA1, which is required for the synthesis of flagellin. The presence in WbpM and its homologs of two distinct domains suggests that the WbpM family of proteins may have arisen as fusions, which now localize biosynthesis to the membrane. The distinct potential membrane-spanning regions in the N termini of these proteins imply that localization to the membrane is important for proper function. Proteins involved in sugar conversions in most LPS biosynthetic systems described are usually soluble cytoplasmic proteins (46), suggesting that the action of the WbpM family of proteins is more complex than simple sugar conversion. The consensus that these proteins are probably involved in synthesis of FucNAc, postulated to be the initiating sugar for synthesis of many P. aeruginosa serogroup LPS subunits, prompts speculation that WbpM and its homologs are membrane associated to synthesize the initiation sugar and/or transfer it directly to the corresponding membrane-bound initiating glycosyltransferase (perhaps WbpL) for linking to the lipid carrier Und-P. The involvement of WbpM in the synthesis of O antigen was confirmed by Burrows et al.: a mutation of wbpMO5 in PAO1 resulted in loss of serogroup O5 O antigen (4).

The nucleotide sequence conservation of WbpM among the 20 P. aeruginosa serogroup strains is intriguing. Conservation implies a similar function for this protein in each strain despite the differences in the O-antigen subunits being made in each serogroup. This conserved function may reflect the presence of FucNAc and/or GalNAc in the majority of the O-antigen subunit structures (22), consistent with the proposed involvement of WbpM in the synthesis of these sugars (4). WbpM could also be involved in synthesis of more highly conserved structures such as the LPS core or possibly even non-LPS molecules. Whether mutations in wbpM have additional effects on other structures is currently under investigation.

Nucleotide sequence downstream of the O-antigen locus: asnV, tyrB, and uvrB genes.

The near total identity observed between the nucleotide sequences of wbpMO11 and wbpMO5 continues downstream of this gene. In the PAO1 sequence analysis (4), a gene designated wbpN was identified between wbpM and uvrB. The deduced amino acid sequence of WbpN showed 19.2% identity to homocitrate synthase from Rhodobacter sphaeorides, and it was proposed that this protein may be involved in LPS biosynthesis (4). In the PA103 sequence there is no ORF corresponding to wbpN, since there is a stop codon in the middle of this region. Moreover, in both PA103 and PAO1, an overlapping ORF whose deduced amino acid sequence shows over 50% identity to E. coli (GenBank accession no. P04693) and S. typhimurium (GenBank accession no. Z68874) TyrB was identified on the opposite strand. This similarity extends to other aminotransferases including AspC of E. coli (47% identity; GenBank accession no. P00509) and Haemophilus influenzae (47% identity; GenBank accession no. P44425) and PhhC of P. aeruginosa (45% identity; GenBank accession no. P43336). The location of the putative tyrB gene corresponds to that of a partial aminotransferase sequence found upstream of the P. aeruginosa uvrB gene by Rivera et al. (37) (GenBank accession no. X93486). Along with tyrB, we noted a tRNA gene showing approximately 95% identity to E. coli asnV (GenBank accession no. X52792) and located between wbpM and tyrB. We also found this tRNA gene in the sequence reported for this region in PAO1.

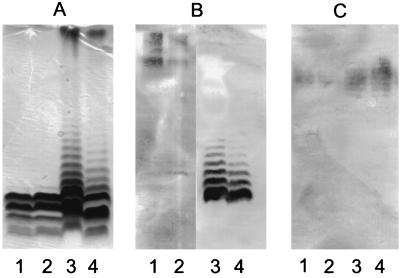

To test whether tyrB plays a role in LPS production, tyrB mutations in PA103 and PAO1 were constructed. Consistent with the data of Patel et al. (31), these tyrB mutants showed a leaky auxotrophic phenotype and required either tyrosine or phenylalanine for growth but did not grow when supplemented with tryptophan. The tyrB mutation did not have any obvious effect on the expression of O antigen or common antigen in either PA103 or PAO1 (Fig. 4). The presence of housekeeping genes adjacent to wbpM suggests that wbpM is probably the terminal gene in both O antigen gene clusters.

FIG. 4.

Effect of tyrB on LPS biosynthesis. (A) Silver-stained Tricine-SDS-PAGE gel. (B) Western immunoblot obtained with serogroup O5 (lanes 1 and 2)- or serogroup O11 (lanes 3 and 4)-specific MAb. (C) Western immunoblot obtained with the common antigen-specific MAb, N1F10. Lanes: 1, PAO1; 2, PAO1 tyrB::aacC1; 3, PA103; 4, PA103 tyrB::aacC1.

Serogroup O11 O-antigen biosynthetic genes were probably horizontally acquired.

The identity between the P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 O antigen genes wbjB to wbjD and capE to capG at both the DNA and protein sequence levels and the similarity of their order and orientation provide strong evidence of the transfer of these genes from S. aureus or another as yet uncharacterized low-G+C-containing organism (Fig. 3). Although the similarities are less dramatic, wbjE and wbjF also appear to have similar foreign origins (Fig. 3). While the method of acquisition of these genes is not known, a section of the wbjB nucleotide sequence (nucleotides 230 to 740) exhibits significant identity to the B. subtilis bacteriophage SPB attachment (attB) site (GenBank accession no. M81761) (58%, expectation value = 1.6 × 10−22). Moreover, the B. subtilis YpqP partial protein (with similarities to capsular polysaccharide proteins) showing similarity to WbjB (Table 2) is reported as partial due to interruption of ypqP by insertion of the SPB prophage. A second potential attB site also occurs in wbpMO11 (52% identity over nucleotides 1140 to 1630). The presence of these sites suggests a bacteriophage-mediated event in the transfer of polysaccharide genes and supports a gram-positive origin for these genes. In addition, the homology between WbjB and the C-terminal half of WbpMO11 (Table 2) extends to the nucleotide level (approximately 53% identity over a 548-nucleotide overlap). The possibility that these homologous end regions were duplicated during the bacteriophage-mediated insertion of the intervening DNA suggests that at least a portion of wbpM, found in all 20 P. aeruginosa serogroup strains, may also have outside origins.

Proposed steps for the synthesis of serogroup O11 O antigen.

On the basis of the structure of the P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 O-antigen unit and the similarity of potential gene products to other gene products involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis, we propose the following steps for the synthesis of this serogroup O antigen. The FucNAc-FucNAc portion of the serogroup O11 O-antigen subunit structure, similar to that found in S. aureus type 5 and 8 capsules, is synthesized by the combined actions of WbjB to WbjF. WbjA adds a glucose residue to the FucNAc disaccharide to complete the O subunit. WbpMO11 and WbpLO11 synthesize the initiating sugar (probably FucNAc) and transfer it to Und-P at the membrane. Like other Wzy-dependent O antigens, the subunits are then transported across the membrane and polymerized by WzxPaO11 and WzyPaO11, respectively, and are then attached to the LPS core with the O-antigen chain length being controlled by WzzPaO11.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Amy Staab and Yan Ren.

This research was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (F238) to D.J.E. and by research grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (P757) and the NIH (RO1 AI35674) to J.B.G.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bastin D A, Romana L K, Reeves P R. Molecular cloning and expression in Escherichia coli K-12 of the rfb gene cluster determining the O antigen of an E. coliO111 strain. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2223–2231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batchelor R A, Alifano P, Biffali E, Hull S I, Hull R A. Nucleotide sequences of the genes regulating O-polysaccharide antigen chain length (rol) from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: protein homology and functional complementation. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5228–5236. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5228-5236.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry D, Kropinski A M. Effect of lipopolysaccharide mutations and temperature on plasmid transformation efficiency in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can J Microbiol. 1986;32:436–438. doi: 10.1139/m86-082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burrows L L, Charter D F, Lam J S. Molecular characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosaserotype O5 (PAO1) B-band lipopolysaccharide gene cluster. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:481–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.1351503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burrows L L, Chow D, Lam J S. Pseudomonas aeruginosaB-band O-antigen chain length is modulated by Wzz (Rol) J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1482–1489. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1482-1489.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burrows L L, Lam J S. Effect of wzx (rfbX) mutation on A-band and B-band lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosaO5. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:973–980. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.973-980.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyne M J, Jr, Goldberg J B. Cloning and characterization of the gene (rfc) encoding O-antigen polymerase of Pseudomonas aeruginosaPAO1. Gene. 1995;167:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyne M J, Jr, Russell K S, Coyle C L, Goldberg J B. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa algCgene encodes phosphoglucomutase, required for the synthesis of a complete lipopolysaccharide core. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3500–3507. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3500-3507.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasgupta T, Lam J S. Identification of rfbA, involved in B-band lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosaserotype O5. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1674–1680. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1674-1680.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Kievit T R, Dasgupta T, Schweizer H, Lam J S. Molecular cloning and characterization of the rfc gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa(serotype O5) Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:565–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Kievit T R, Staples T, Lam J S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa rfcgenes of serotypes O2 and O5 could complement O-polymerase-deficient semi-rough mutants of either serotype. FEMS Microbiol Letts. 1997;147:251–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans D J, Pier G B, Coyne M J, Jr, Goldberg J B. The rfb locus from Pseudomonas aeruginosastrain PA103 promotes the expression of O antigen by both LPS-rough and LPS-smooth isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:427–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farmer J J, III, Weinstein R A, Zierdt C H, Brokopp C D. Hospital outbreaks caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: importance of serogroup O11. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:266–270. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.2.266-270.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman A M, Long S R, Brown S E, Buikema W J, Ausubel F M. Construction of a broad host range cosmid cloning vector and its use in the genetic analysis of Rhizobiummutants. Gene. 1982;18:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg J B, Hatano K, Pier G B. Synthesis of lipopolysaccharide O side chains by Pseudomonas aeruginosaPAO1 requires the enzyme phosphomannomutase. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1605–1611. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1605-1611.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg J B, Hatano K, Small-Meluleni G, Pier G B. Cloning and surface expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa O antigen in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10716–10720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg J B, Ohman D E. Cloning and expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosaof a gene involved in the production of alginate. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:1115–1121. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.3.1115-1121.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg J B, Ohman D E. Construction and characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa algB mutants: role of algBin high-level production of alginate. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1593–1602. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1593-1602.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hitchcock P J, Brown T M. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonellalipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:269–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang P J, Hauser A R, Apodaca G, Fleiszig S M J, Wiener-Kronish J, Mostov K, Engel J N. Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosagenes required for epithelial cell injury. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1249–1262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4311793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knirel Y A, Kochetkov N K. The structure of lipopolysaccharides of gram-negative bacteria. III. The structures of O-antigens: a review. Biochemistry (Moscow) 1994;59:1325–1383. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knirel Y A, Vinogradov E V, Kocharova N A, Paramonov N A, Kochetkov N K, Dmitriev B A, Stanislavsky E S, Lanyi B. The structure of O-specific polysaccharides and serological classification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Acta Microbiol Hung. 1988;35:3–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kropinski A M, Chan L C, Milazzo F H. The extraction and analysis of lipopolysaccharides from Pseudomonas aeruginosastrain PAO, and three rough mutants. Can J Microbiol. 1979;25:390–398. doi: 10.1139/m79-060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lightfoot J, Lam J S. Chromosomal mapping, expression and synthesis of lipopolysaccharide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a role for guanosine diphospho (GDP)-d-mannose. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:771–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu P V. Exotoxins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. I. Factors that influence the production of exotoxin A. J Infect Dis. 1973;128:506–513. doi: 10.1093/infdis/128.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu W S, Cole R A, Reeves P R. An O-antigen processing function for Wzx (RfbX): a promising candidate for O-antigen flippase. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2102–2107. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2102-2107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morona R, Mavris M, Fallarino A, Manning P A. Characterization of the rfc region of Shigella flexneri. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:733–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.733-747.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morona R, Van Den Bosch L, Manning P A. Molecular, genetic, and topological characterization of O-antigen chain length regulation in Shigella flexneri. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1059–1068. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.1059-1068.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohman D E, Sadoff J C, Iglewski B H. Toxin A-deficient mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosaPA103: isolation and characterization. Infect Immun. 1980;28:899–908. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.3.899-908.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palleroni N J. Family I. Pseudomonadaceae. In: Kreig N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Williams Co.; 1984. p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel N, Stenmark-Cox S L, Jensen R A. Enzymological basis for reluctant auxotrophy for phenylalanine and tyrosine in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:2972–2978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pier G B, Meluleni G, Goldberg J B. Clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosafrom the murine gastrointestinal tract is effectively mediated by O-antigen-specific circulating antibodies. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2818–2825. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2818-2825.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pier G B, Thomas D M. Lipopolysaccharide and high molecular weight polysaccharide serotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 1982;148:217–223. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratnaningsih E, Dharmsthiti S, Krishnapillai V, Morgan A, Sinclair M, Holloway B W. A combined physical and genetic map of Pseudomonas aeruginosaPAO. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2351–2357. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-12-2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeves P. Evolution of SalmonellaO antigen variation by interspecific gene transfer on a large scale. Trends Genet. 1993;9:17–22. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90067-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rivera E, Vila L, Barbe J. The uvrB gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosais not DNA damage inducible. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5550–5554. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5550-5554.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rocchetta H L, Burrows L L, Pacan J C, Lam J S. Three rhamnosyltransferases responsible for assembly of the A-band d-rhamnan polysaccharide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a fourth transferase, WbpL, is required for the initiation of both A-band and B-band lipopolysaccharide synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1103–1119. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00871.x. . (Erratum, 30:1131, 1998.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sau S, Shasin N, Wann E R, Lee J C, Foster T J, Lee C Y. The Staphylococcus aureusallelic genetic loci for serotype 5 and 8 capsule expression contain the type-specific genes flanked by common genes. Microbiology. 1997;143:2395–2405. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawa T, Ohara M, Kurahashi K, Twining S S, Frank D W, Doroques D B, Long T, Gropper M A, Wiener-Kronish J P. In vitro cellular toxicity predicts Pseudomonas aeruginosavirulence in lung infections. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3242–3249. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3242-3249.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schweizer H P. Escherichia-Pseudomonasshuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19. Gene. 1991;97:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schweizer H P. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques. 1993;15:831–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schweizer H P, Hoang T T. An improved system for gene replacement and xylE fusion analysis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1995;138:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00055-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shortridge V D, Pato M L, Vasil A I, Vasil M L. Physical mapping of virulence-associated genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosaby transverse alternating-field electrophoresis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3596–3603. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3596-3603.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad-host-range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skurnik M, Venho R, Toivanen P, Al-Hendy A. A novel locus of Yersinia enterocoliticaserotype O:3 involved in lipopolysaccharide outer core biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:575–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17030575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith A W, Iglewski B H. Transformation of Pseudomonas aeruginosaby electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:10509. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.24.10509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tassios P T, Gennimata V, Maniatis A N, Fock C, Legakis N J The Greek Pseudomonas aeruginosa Study Group. Emergence of multidrug resistance in ubiquitous and dominant Pseudomonas aeruginosaserogroup O:11. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:897–901. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.897-901.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.West S E H, Iglewski B H. Codon usage in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9323–9335. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.19.9323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.West S E H, Kaye S A, Hamood A N, Iglewski B H. Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants that are deficient in exotoxin A synthesis and are altered in expression of regA, a positive regulator of exotoxin A. Infect Immun. 1994;62:897–903. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.897-903.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woo T H S, Cheng A F, Ling J M. An application of a simple method for the preparation of bacterial DNA. BioTechniques. 1992;13:696–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]