Abstract

Background

Schistosomiasis is a neglected tropical disease (NTD) that affects around 200 million people worldwide, the majority of whom are children aged 5 to 15 years. It is one of the most significant public health problems in tropical and subtropical regions. Entamoeba histolytica infection is common in areas where schistosomiasis is endemic because Schistosoma mansoni infection can reduce the host’s immune response, resulting in increased morbidity.

Case Presentation

This is the story of a 12-year-old male adolescent from the Guji zone of the Oromia regional state of Ethiopia who presented to Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (HUCSH) complaining of bloody diarrhea of 1 week associated with vomiting of ingested matter of 2 weeks. He also had history of fever, chills, rigors, arthralgia, and weight loss during a 2 weeks period. Further questioning revealed that he had previously swum in a pond and had a self-limited itchy skin condition. The family said that similar cases had occurred in their town that resolved with medications provided at a local health center.

Conclusion

Schistosomiasis and amebiasis are major public health issues, especially in impoverished areas. Schistosomiasis presents differently clinically depending on the phase and clinical form in which it manifests, making diagnosis and management challenging. As a result, it necessitates an integrated collaboration involving clinicians, pathologists, and public health professionals. We describe ulcerative colitis (UC) ascribed to schistosomiasis and amoebiasis coinfection, and fulminant hepatitis due to schistosomiasis. As there was no report of liver abscess on sonographic scanning, hepatitis may not be due to coinfection. This case will be an alert to clinicians and public health personnel who are striving for the ultimate eradication of schistosomiasis and also teaches us that treating co-infections of both is beyond just giving praziquantel and antiamebics.

Keywords: schistosomiasis, amebiasis, coinfection, ulcerative colitis, fulminant hepatitis

Introduction

Schistosomiasis is a parasite ailment that affects 200 million people worldwide, the majority of whom are children between the ages of 5 and 15 years.1–5 According to World Health Organization data, it is a neglected tropical disease (NTD) and one of the most common parasite infections, affecting more than 236 million people worldwide.4,6–10

The geographic distribution of schistosomiasis varies per species; however, endemic locations can be found in tropical and subtropical parts of Africa, Asia, South America, and the Caribbean. Schistosomes have a complex life cycle, with snails serving as intermediate hosts and humans serving as the final host. S. mansoni, a parasitic trematode that parasitizes humans and other primates, is one of the principal agents of the intestinal form, along with S. japonicum, S. mekongi, and S. intercalatum. Infected persons excrete parasite eggs in their feces and urine, which can contaminate fresh, warm water, particularly in locations where cleanliness is low. When the eggs hatch, miracidia are released which infect snails, breed asexually, and emerge as cercariae. After that, the cercariae penetrate the human skin and convert into schistosomula. The schistosomula travel through blood and lymph, finally reaching the left side of the heart and the mesenteric and portal arteries, where the mature worms settle in 3–6 weeks after infection. The immunological response that follows sexual reproduction with egg deposition in many organs causes tissue damage and illness.3,5,8–12

The pooled prevalence of human intestinal protozoan parasitic infections in Ethiopia, where Entamoeba histolytica is the most common parasite, was 25.01% (95% CI: 20.08%-29.95%) according to the systematic review and meta analysis (14.09%, 95% CI: 11.03%-17.14%).

Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Human Intestinal.13

Entamoeba histolytica infection is common in areas where schistosomiasis is endemic because S. mansoni infection can reduce the host’s immune response, resulting in increased morbidity.14,15 Overall, a previous infection with Schistosoma frequently affects a subsequent Entamoeba histolytica illness that follows. There are consequences for patient care and recovery since, in several of these studies on coinfection, the greater severity of the subsequent infection was linked to a particular, protracted form of the disease in humans.16

From a clinical standpoint, schistosomiasis is divided into three stages: (i) cercarial dermatitis, which appears 24 hours after cercariae penetrate the dermis; (ii) acute schistosomiasis, which appears 3–8 weeks after infection; and (iii) chronic schistosomiasis, which appears months or years after infection and is caused by the formation of granulomas in the tissues around the schistosome.16–18

Katayama fever develops in roughly 4 to 6 weeks in someone who has never been infected. Symptoms begin to appear at the same time that egg deposition begins. S. mansoni, S. haematobium, and especially S. japonicum have all been linked to Katayama fever. It is thought to be the outcome of circulating immune complexes, which cause a serum sickness-like reaction. Fever, chills, arthralgias, myalgias, dry cough, wheezing, abdominal pain, and diarrhea are some of the signs and symptoms. Physical manifestations include rashes, painful hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy.5,9,11,18

According to earlier studies, 45.3% of patients with S. mansoni positive colonic biopsies have schistosomiasis, but S mansoni eggs in feces are found only in 11.1% of patients with S. mansoni positive colonic biopsies.19,20

Because of the parasite’s potential to cause inflammation and fibrosis, chronic schistosomiasis is mostly caused by granulomatous inflammation caused by the parasite’s eggs accumulating in various organs. After traveling through the portal venous system and embolizing in the liver or spleen, or if moving to the systemic circulation, the lungs, brain, or spinal cord, the eggs reach the various tissues. Patients born in endemic countries contract the infection during childhood and may develop a chronic condition as a result of continuous reinfection by freshwater contact, with subtle clinical differences depending on the schistosome species. As a result, Sub-Saharan African countries account for 90% of all Schistosomiasis cases worldwide. Prevalence rates for S. haematobium range from 10% to 50% in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East, and 1% to 40% for S. mansoni in Sub-Saharan Africa and South America, with comparable percentages for S. japonicum in Indonesia, parts of China, and Southeast Asia.9,10,16,17,21

Intestinal Schistosomiasis is a common chronic problem that has been documented in cases for many years and is caused by infection with Schistosoma mansoni, S. japonicum, S. intercalatum, S. mekongi, and, on rare occasions, S. haematobium. Recurrent exposure and the amount of parasite eggs present in the mucosa of the intestinal tract, primarily the colon and rectum, where they generate an inflammatory reaction and the formation of granulomas, ulcers, and fibrosis, determine the severity.9,22,23

Chronic or intermittent abdominal pain, asthenia, weight loss, anorexia, and diarrhea are the most prevalent symptoms of intestinal Schistosomiasis. It can be accompanied by anemia in severe cases, which is caused by bleeding from ulcerations in the colon and rectum (which might mimic chronic colitis caused by other etiologies, including inflammatory bowel disease). Furthermore, patients have a higher incidence of colorectal polyps, particularly rectal polyps and granulomatous inflammation can degenerate into polyps, which are the most common intestinal lesion in chronic intestinal Schistosomiasis and can even trigger the appearance of dysplasia; however, these polyps were all discovered during colonoscopy and presented as large polyps rather than cecal thickening. They can even develop intestinal obstructive symptoms 28 that look like colon cancer in some circumstances.4,22,24

Clinical signs in patients with a suitable exposure history, as well as microscopic analysis of feces or urine for eggs, are used to make the diagnosis. Eosinophilia is found in 33–66% of patients. Serological techniques, such as ELISAs for distinct schistosome species, have varying sensitivity and are unable to distinguish between acute and chronic infection.1,14,25–27

When the accurate diagnosis is made, the anti-parasitic medication praziquantel can be used to help the patient recover completely. Schistosomiasis is more common because of the close contact between humans and infected water. The strategies to prevent schistosomiasis are the elimination of intermediate hosts and avoiding contact with infected water sources. Praziquantel, metriphonate, and oxamniquine are some of the current treatments. The therapy of choice is praziquantel 40–60 mg/kg divided into 1–3 doses for one day.1,4,5,9,18,21,26,28–30

Its relative ineffectiveness against recent infection is a big flaw of praziquantel, which may occasionally lead to low cure rates in highly endemic settings. Research also revealed that some schistosoma isolates had lower sensitivity to this medication. In the case of young schistosomula, this medicine is less effective, and numerous therapy courses may be required.30

An Ethical Review

The patient’s father provided informed consent for the publication of this case report after the letter of permission to do so was obtained from Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (HUCSH) Institutional review Board (IRB).

Case Presentation

This is a case of a 12-year-old male adolescent who was referred to HUCSH from the Oromia region’s Guji zone with complaints of bloody diarrhea lasting for one week and occurring 8–10 times per day, which had intensified in the days leading up to his presentation to our hospital. He also had a 2-week history of vomiting of ingested matter 3–5 times per day, which became bilious and more frequent over the last two days prior to his admission to our hospital. He also had a history of high-grade intermittent fever, chills, rigors, arthralgia, and a significant but unquantified weight loss during the two-week period.

Further questioning revealed that he had previously swum in a pond and had a self-limited itchy skin condition. The family said that similar cases had occurred in their town that resolved with medications provided at a local health center; however, their child’s situation was unusual and more serious despite the fact that he was treated likewise.

He was started on metronidazole, ceftriaxone, cimetidine, Vit B complex, and Vit K with the impression of fulminant viral hepatitis, schistosomiasis and acute kidney injury (AKI), and was referred to Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (HUCSH) for inpatient care and further workup for the above complaints.

Physical examination: General appearance: acute sick looking; Vital signs: all were within normal limits with the exception of the temperature, which was 37.8 degree Celsius.

Abdominal examination revealed tenderness in the epigastrium area and hepatomegaly, with a total liver span of 11 cm. The rectal examination was normal. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. The rest of the exam was also unremarkable.

Investigation course (See Table 1)

Table 1.

Summary of Pertinent Investigation Results of the Case

| Investigation | Result | Remarks | Normal Values for His Age® | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | Negative | ||||

| HBSag | Negative | ||||

| HCV Ab | Negative | ||||

| ANA | Negative | ||||

| Bilirubin | <1.0 | ||||

| Total | First | 2.33 | Elevated | ||

| Second (done after 3dy) | 1.84 | ||||

| Direct | First | 1.69 | Yet elevated, but subsided | ||

| Second (done after 3dy) | 1.53 | ||||

| AST | First | 137mg/dl | Elevated 3 times | 10–40 | |

| Second (done after 3dy) | 35 | Normal | |||

| ALT | First | 110mg/dl | Elevated 2.5 times | 5–45 | |

| Second (done after 3dy) | 41mg/dl | ||||

| Coagulation Profile | |||||

| PTT | 68 | 2.4X raised | 25–35 | ||

| 16.4 | 1.17X raised | ||||

| PT | 21.1 seconds | Elevated | 11–13.5 seconds | ||

| INR | 2.41 | Elevated | 0.8–1.1 | ||

| Serum Albumin | 3.9 g/dl | Normal | 3.4–5 0.4 g/dl | ||

| Renal Function Test | |||||

| Creatinine | 1.5mg/dl | BUN/Cr: 26.5 |

Prerenal azotemia | 0.31–0.88 | |

| BUN | 85mg/dl | 7–18 | |||

| Stool microscopy |

E.hist.trophozoite S.masonia ova |

Amebiasis, and Schistosomiasis | |||

| Stool Ag for H. pylori infection | Negative | ||||

| CBC | |||||

| WBC | 12,000/mm3 N=67.8% L=22.5% E=9.7% |

High for age | 4.0–10.5 | ||

| Platelet | 92,000/mm3 | Low | 150–450×106 | ||

| Eosinophil | 9.7%, | Elevated | 1–3% | ||

| Fecal Calprotectin (CLIA) | 7.68 microgram/g | Normal | 50 microgram/g | ||

Note: ®.44

The investigation results for malaria (Rapid Diagnostic Test/blood film), antinuclear antibody (ANA), serology for hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and HIV were all negative.

The total and direct serum bilirubin were 2.33 mg/dL and 1.69 mg/d, respectively (elevated), and subsequently dropped to 1.84 mg/dL and 1.53mg/dL after 3 days, respectively. The serum albumin was in the normal range,3.9 g/dl.

Stool Examination revealed ova of S. mansoni and Trophozoite stages of E. histolytica.But the stool antigen examination for H. pylori infection was negative.

Abdominal ultrasound revealed hepatomegaly with hypodense hepatic nodules likely due to acute hepatitis, and also significant wall thickening and edema of the colon and the small bowel loops likely due to enterocolitis.

The results of complete blood count (CBC) were as follows: WBC = 12 *103(elevated), Neutrophil = 67.8%, Lymphocyte = 22.5%, Eosinophil = 9.7%, Platelet = 92 *103(Low), other parameters were all normal.

Aspartate transaminase (AST) was 137 U/L on the day of admission (elevated 2.5 times) and 35U/L on the 3rd days, whereas the alanine transaminase (ALT) was 110 U/L on the day of admission (elevated 2.5 times) 41U/L on the 3rd days.

Coagulation profile (all were elevated): PTT=68.2.4 seconds, PT = 21.1seconds, INR = 2.41, after 1 week PT = 16.4 seconds =1.17 (normal).

The renal function test revealed creatinine of 1.5 mg/dL and urea of 85 mg/dL, with BUN/Cr ratio of 26.5, suggestive of prerenal azotemia (from the vomiting and poor intake he had).

Urine analysis: Leucocyte = +1, WBC = 7-10/HPF, Protein = +2, Ketone = +1, and the rest of the urinalysis results were unremarkable. It suggests urinary tract infection, and perhaps kidney insults from Schistosoma mansoni.

The serum electrolytes and random blood sugar were all in the normal ranges.

Fecal Calprotectin (CLIA)=7.68 microgram/g [less than 50 is normal (negative)]. It helps to differentiate irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), monitor the effectiveness of IBD therapy, and detect IBD relapse.31,32

Colonoscopy: After informed consent, video pan colonoscopy was done smoothly up to the cecum and revealed diffuse colon mucosal inflammation with intense rectal inflammation with extensive ulceration and exudates and loss of vascular patterns. Rectal biopsy was taken with the impression of ulcerative colitis r/o IBD with the recommendation of fluid and electrolyte and antibiotics with follow histology and laboratory tests for differential diagnosis and treatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Colonoscopy findings of a-12-year-old male adolescent from Ethiopia: Diffuse colon mucosal inflammation with intense rectal inflammation with extensive ulceration and exudates and loss of vascular patterns, and biopsied with the impression of Ulcerative colitis rule out IBD.

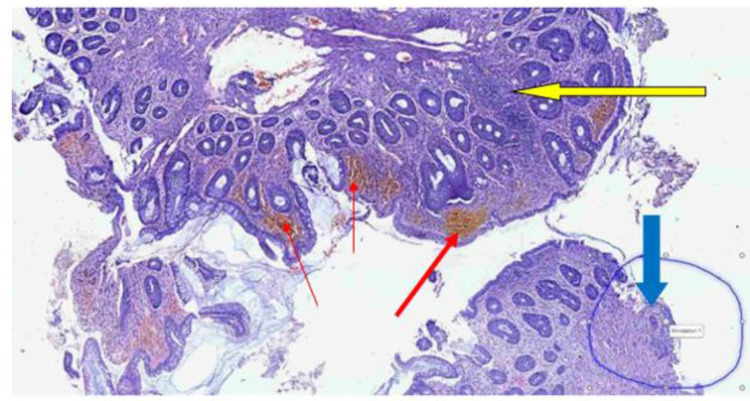

The macroscopic examination (gross description): multiple gray white to gray brown soft tissue fragments,0.5 cm, in aggregate. Note: Due to the loss of elastic tension and to formalin shrinkage, the measurements in the gross description may be less than those taken at the time of surgical removal (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Low power photomicrograph revealing fragments of mucosal biopsy with foci of lymphoplasmacytic (yellow arrow) lamina propria infiltration, hemorrhage (red arrows) and a focus of an egg of S. mansoni (down blue arrow).

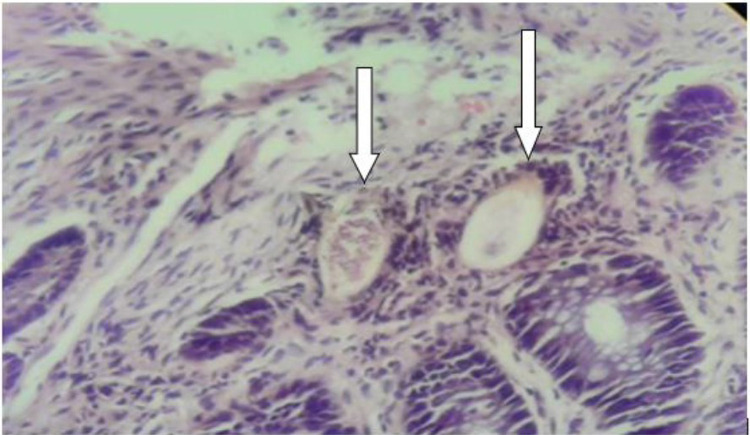

Figure 3.

High power photomicrograph showing eggs of S.mansoni (down arrows) with surrounding inflammatory cells.

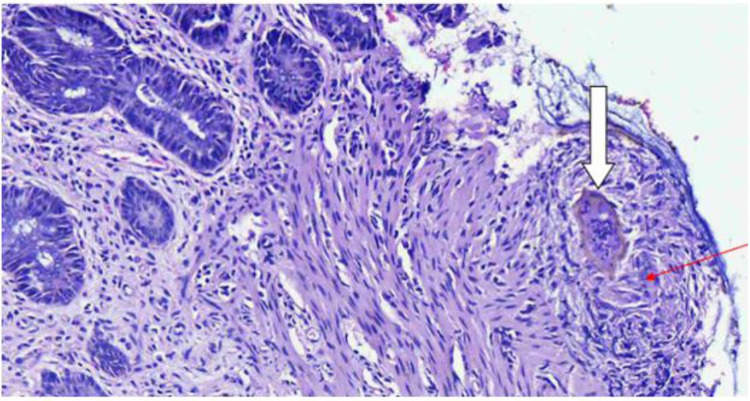

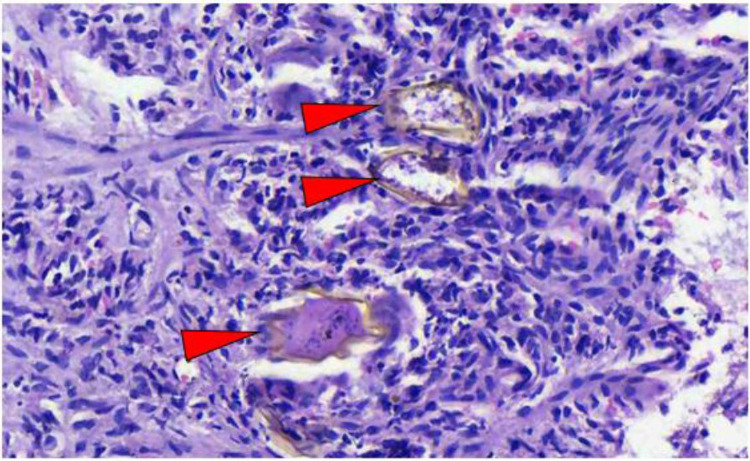

Microscopic description of biopsy: Section show colonic type mucosal fragments with diffuse lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic infiltrates in the lamina propria associated with mild crypt distortion, fibrosis, areas of hemorrhage and foci of neutrophilic infiltrates. There are few Schistosoma eggs and focus of giant cell reaction (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

High power photomicrograph showing an egg of S. mansoni (down arrow) surrounded by mixed inflammatory cells and multinucleated giant cell (red arrow) with adjacent fibrosis.

Figure 5.

High power photomicrograph revealing eggs of S. mansoni (red arrow heads) surrounded by mononuclear inflammatory cells in the lamina propria.

The final biopsy diagnosis was colon and rectum schistosomiasis.

He was admitted to our hospital for two weeks and was given prednisolone 2 mg/kg (ie, 30 mg po bid) and Praziquantel (40 mg/kg/day, ie, 2 tablets of 600 mg po/day). Serial determinations of liver and renal function tests and coagulation profiles were done. He also had repeated abdominal ultrasound exams, which all showed improvements over the previous results. He was then referred to a gastroenterologist for evaluation, where a colonoscopy and biopsy were performed, and schistosomiasis induced ulcerative colitis was confirmed, and he continued prednisolone 2 mg/kg (30 mg po bid) for another one month, and stopped being tapered over 2 months and the second dose of praziquantel (1200 mg) was also given within 1 month interval. Now, his clinical condition is apparently okay, and he is attending his school without any symptoms.

Discussion

We report the ulcerative colitis due to S. mansoni and E.histolyticacoinfection, andFulminant hepatitis due to S. mansoni in a 12-year-old adolescent from Ethiopia, which is a typical age in endemic countries.5,10,11,19,33 Entamoeba histolytica infection is common in areas where schistosomiasis is endemic because S.mansoni infection can reduce the host’s immune response, resulting in increased morbidity in addition to the fact that both are water born diseases, and reflects the burden of neglected tropical diseases.14,15,34–37

Literature shows that increased levels of E. histolytica infection with amoebic invasiveness were directly correlated with the severity of S. mansoni colonic polyps. According to one study, damage caused by S. mansoni eggs in the intestinal mucosa may encourage E. histolytica to proliferate and invade the mucosa, whereas a different study theorized that S. mansoni infection may weaken the immune system and make people more susceptible to E. histolytica.34,35

The patient developed Fulminant hepatitis after a few days of non-specific symptoms following a recent contact with stagnant water (perhaps contaminated). The lack of clinical signs of portal hypertension suggested that the disease was in an acute stage.11 Acute infection is further supported by the appearance of ultrasonography hypodense hepatic nodules and stool microscopy finding. These findings may concur with the widely held belief that hepatocyte function is affected during the various stages of schistosomiasis if the patient is also infected with another parasite, amebiasis in our case.5,11,17,36 However, the hepatic nodules detected on ultrasound were not described as liver abscess suggestive of amoebic liver abscess. As a result, rather than coinfection, we considered schistosomiasis as the primary cause of Fulminant hepatitis in this patient.

In this instance, the coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia could represent hematologic manifestations of S. mansoni, and the coagulation profile and platelet count should be obtained to examine both the treatment response and complications.37

The colonoscopy revealed macroscopic lesions that were treated with praziquantel but did not resolve, indicating a bowel inflammatory chronic condition. The lack of response could also be due to low efficacy of praziquantel.37,38 The fact that our patient also had E. histolytica may indicate that the infective colitis could be due to co-infection which might affect the response to treatment. A Schistosoma infection was discovered after a colon biopsy and feces investigation, which was treated with praziquantel plus prednisolone and resulted in a complete recovery. According to earlier research, 45.3% of patients with S. mansoni positive colonic biopsies have schistosomiasis, but S. mansoni eggs in feces are only found in 11.1% of patients with S. mansoni positive colonic biopsies. In our situation, however, the results of the stool examination and the colonoscopy were complimentary (positive results).19,20,22 Despite the fact that the clinical manifestations and sonographic findings indicate an acute infection, the colonoscopy observations of eggs indicate chronic schistosomiasis. This could be because the patient is from an endemic location, has had numerous bouts of reinfection, and is hence acute on chronic infection.4 The fact that our patient also had E. histolytica may indicate that the infective colitis could be due to co-infection.15,16

Despite the fact that Schistosoma mansoni causes renal symptoms, this patient’s urinary tract infection may have been a fortuitous finding. Proteinuria (which was plus 2 in this case) could be caused by S. mansoni, as similar cases have been documented in the literatures. S. mansoni may be to blame for this patient’s renal failure, as comparable findings have been reported even though the possibility of prerenal acute kidney injury due to gastrointestinal loss and poor intake, as evidenced by renal function tests, is very likely. The immunologic character of the glomerular lesion in S. mansoni is one of the postulated mechanisms.7,13,15,22,38–40

Praziquantel is the preferred drug for the treatment of schistosomiasis. In the case of young schistosomula, this medicine is less effective, and numerous therapy courses may be required. The patient was given multiple courses of praziquantel, but he continued to worsen clinically and biochemically. This is consistent with observations that praziquantel can worsen the clinical status of acute schistosomiasis patients. In the treatment of acute schistosomiasis, concomitant administration of schistosomicide medicines and corticosteroids alleviates this reaction and acts synergistically. The combination of praziquantel and prednisolone, according to our data, was responsible for the remission of UC and fulminant hepatitis in this patient.1,5,9,18,19,28,41–43

Conclusion

Schistosomiasis and amoebiasis are major public health issues, especially in impoverished areas. Schistosomiasis presents differently clinically depending on the phase and clinical form in which it manifests, making diagnosis and management challenging. As a result, it necessitates an integrated collaboration involving clinicians, pathologists, and public health professionals. We describe ulcerative colitis (UC) ascribed to schistosomiasis and amoebiasis coinfection, and fulminant hepatitis due to schistosomiasis. As there was no report of liver abscess on sonographic scanning, hepatitis may not be due to coinfection. This case will be an alert to clinicians and public health personnel who are striving for the ultimate eradication of schistosomiasis and also teaches us that treating co-infections of both is beyond just giving praziquantel and antiamebics.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the managing teams who participated in the management of this patient throughout his stay in our hospital. Our Special thanks go to Makira medium clinic for initial evaluation, management, prompt referral and data completion. Lastly, but not the least, we would like to acknowledge the father of the case, Obbo Abera Kebede for his willingness in providing all the documents, and update on the clinical conditions of the case.

Data Sharing Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave the final approval of the version to be published; agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.De E. Schistosomiasis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25(3):599–625. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8553(05)70265-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chitsulo L, Loverde P, Engels D. Schistosomiasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:12–13. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan PWG, Jordan P, Webbe G. Human schistosomiasis. Human schistosomiasis. 1993;87–158. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization WH. The control of schistosomiasis: second report of the WHO expert committee. WHO Tech Rep Ser. 1993;830:1–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shinawi MK, Kovalski Y, Berkowitz D, Brik R, Kassis I, Shamir R. Fulminant hepatitis associated with schistosoma mansoni. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32(5):605–607. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200105000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kloos H, Lo CT, Birrie H, Ayele T, Tedla S, Tsegay F. Schistosomiasis in Ethiopia. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26(8):803–27.7. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90174-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moroni G. Schistosomiasis-associated kidney disease. Front Med. 2020;1808:13 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senanayake N. Schistosomiasis. Trop Geogr Med. 1990;458–473. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gyssels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, et al. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368(9541):1106–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King CH. Parasites and poverty: the case of schistosomiasis. Acta Trop. 2010;113:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doherty JFMA, Wright SG, Wright SG. Katayama fever: an acute manifestation of schistosomiasis. BMJ. 1996;313(7064):1071–1072. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7064.1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Wahab MF, Esmat G, Ramzy I. Schistosoma haematobium infection in Egyptian schoolchildren: demonstration of both hepatic and urinary tract morbidity by ultrasonography. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86(4):406–409. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90241-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DIRES, TEGEN. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Intestinal Parasitic Infections Among Primary School Children in Deradestancte North West Ethiopia. Diss; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansour NS, Youssef FG, Mikhail EM, Mohareb EW. Amebiasis in schistosomiasis endemic and non-endemic areas in Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1997;27(3):617–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolabella SS, Coelho PM, Borçari IT, Mello NA, Andrade ZD, Silva EF. Morbidity due to Schistosoma mansoni-Entamoeba histolytica coinfection in hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus). Revista da SociedadeBrasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2007;40:170–174. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822007000200005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abruzzi A, Fried B. Coinfection of Schistosoma (Trematoda) with bacteria, protozoa and helminths. Adv Parasitol. 2011;Jan(77):1–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norman F, Perez-Molina JA, López-Vélez R, Perez-Molina JA, López-Vélez R. Parasitic infections in travelers and immigrants: part II helminths and ectoparasites. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:87–99. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harries AD, Cook GC. Acute schistosomiasis (Katayama fever): clinical deterioration after chemotherapy. J Infection. 1987;14(2):159–161. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(87)92002-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FatenLimaiem AS. Crohn’s disease and schistosomiasis: a rare association. Pan African Medical Journal. 2016;1:548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rizzo M, Barresi E, Berneis K, et al. A case of bowel schistosomiasis not adhering to endoscopic findings. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:44. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i44.7044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zoni A, Catalá L, Ault SK. Schistosomiasis Prevalence and Intensity of Infection in Latin America and the Caribbean Countries, 1942-2014: a Systematic Review in the Context of a Regional Elimination Goal. PLoS Neglect Trop. 2016;10(3):e0004493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qin X, Bai T, Zhang L, et al. The clinical features of chronic intestinal schistosomiasis related intestinal lesions. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(21). doi: 10.1186/s12876-020-01591-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lingscheid T. European Travelers and Migrants: analysis of 14 Years TropNet Surveillance Data. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:567–574. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Combes A, Magdy M, Morris DL. Intestinal schistosomiasis mimicking caecal malignancy. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90(12):2576–2577. doi: 10.1111/ans.15944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahmoud AAF. The ecology of eosinophils in schistosomiasis. J Infect Dis. 1982;145(5):613–622. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.2.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunne DW, Butterworth AE, Sturrock RF, et al. Human antibody responses to Schistosoma mansoni: the influence of epitopes shared between different life-cycle stages on the response to the schistosomulum. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:123–131. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiatt RAOE, Sotomayor ZR, Sotomayor ZR, et al. Serial observations of circulating immune complexes in patients with acute schistosomiasis. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:665–670. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.5.665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ong EL. Acute schistosomiasis (Katayama fever): corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy. Scand J Infect Dis. 1989;21(4):473–474. doi: 10.3109/00365548909167455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buonfrate DTFGF. Imported chronic schistosomiasis: screening and management issues. J Travel Med. 2020;1:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cioli D, Pica-Mattoccia L. Praziquantel. Parasitol Res. 2003;90(1):S3–9. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0751-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sihag S, Tan B, Semenov S. Faecal calprotectin for screening of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease: diagnostic meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1):341. doi: 10.1186/s12876-020-01486-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson P, Casey A, Lawrence SJ, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin during the investigation of suspected pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(6):941. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross AG, Olds GR, Li Y, Williams GM, McManus DP. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(16):1212–1220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamm DM, Agossou A, Gantin RG, et al. Coinfections with Schistosoma haematobium, Necator americanus and Entamoeba histolytica/Entamoeba dispar in Children: chemokine and cytokine responses and changes after antiparasite treatment. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(11):1583–1591. doi: 10.1086/598950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Everts B, Perona-Wright G, Smits HH, et al. Omega-1, a glycoprotein secreted by Schistosoma mansoni eggs, drives Th2 responses. J Exp Med. 2009;206(8):1673–1680. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cesmeli EVD, Voet D. Ultrasound and CT changes of liver parenchyma in acute schistosomiasis. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:758–760. doi: 10.1259/bjr.70.835.9245889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eyayu T, Zeleke AJ, Seyoum M, Worku L. Basic coagulation profiles and platelet count among Schistosoma mansoni-infected adults attending Sanja primary hospital, northwest Ethiopia. Res Rep Trop Med. 2020;11:27. doi: 10.2147/RRTM.S244912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukushige M, Chase-Topping M, Woolhouse ME, Mutapi F. Efficacy of praziquantel has been maintained over four decades (from 1977 to 2018): a systematic review and meta-analysis of factors influence its efficacy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(3):e0009189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neema M. Renal abnormalities and its associated factors among school-aged children living in Schistosoma mansoni endemic communities in Northwestern Tanzania. BMC Tropical Medicine Health. 2020;48:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moriearty BE. Elution of renal anti-schistosome antibodies in human Schistosomiasis mansoni. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1977;26:717–722. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1977.26.717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carlier Y, Camus D, Figueiredo FM, Capron A, Carlier Y, Figueiredo JFM. Immunological studies in human schistosomiasis. Am JTrop Med Hyg. 1075;24:949–954. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1975.24.949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.NSaEA YS. Hepatobiliary Schistosomiasis Journal of Clinical Translational Hepatology. Eurosurveillance. 2014;2:212–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lambertucci JR. Acute schistosomiasis: clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic features. Rev Ins Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1993;35(5):399–404. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46651993000500003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sbsgs KR. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21 ed. 2020. [Google Scholar]