Abstract

Polypharmacy, usually defined as taking ≥5 prescribed medications, increases chances of drug–drug interactions and toxicities, and may harm cancer patients who need multiple chemotherapeutic agents and supportive medications. We analyzed the effects of polypharmacy in overall survival (OS) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). A total of 399 patients were divided into two groups: patients with polypharmacy (≥5 medications) versus without polypharmacy (<5 medications). Polypharmacy was associated with age ≥60 years, Karnofsky Performance Status of ≤80, hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) comorbidity index of ≥5, and adverse cytogenetics. Patients with polypharmacy were less likely to receive intensity chemotherapy or HCT. One-year OS of patients with polypharmacy versus those without polypharmacy was 29 vs. 49% (p<.001). Polypharmacy conferred worse OS in patients <60 years (37 vs. 65% at 1 year, HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.21–3.15) but not in patients ≥60 years (26 vs. 27% at 1 year, HR 1.12, 95% CI 0.81–1.57). Thus, polypharmacy has negative impact on OS in AML, particularly among patients aged <60 years.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, polypharmacy, overall survival, medications, prognosis

Introduction

Polypharmacy is commonly defined as taking ≥5 prescribed medications [1-3]. Although multiple definitions have been used, a systemic review reported 5 as the most common cutoff for polypharmacy in almost half of the total 110 studies [3]. Polypharmacy is quite prevalent in adults in general, especially those ≥60 years of age. In young adults, medications for developmental disabilities, chronic pain, mental health, and comorbidities such as diabetes, heart disease, and neurological conditions including stroke usually contribute to polypharmacy [2,4]. Older adults are at greater risk for polypharmacy as they are often frail, and have multimorbidity and cognitive impairment [5]. Residence at long term care facilities has also been associated with polypharmacy in older adults [6]. In one survey of patients ≥65 years of age, 31% of patients used more than 1 pharmacy, and 50% received prescriptions from more than 1 provider [7]. In addition, over the counter medications and herbal supplements are distinctly unrecognized but significant cause of polypharmacy in patients of all age groups [7,8]. The risk of polypharmacy is higher in cancer patients who need multiple medications for their cancer treatment and supportive care in addition to the treatment for other comorbidities [8,9]. Polypharmacy has been reported in 50–80% of patients with cancer [10,11]. In one study, two-thirds of cancer patients also took 2 over-the-counter medications and 2 vitamins, herbs, or supplements [12].

Polypharmacy confers a substantial risk of adverse drug reactions; drug–drug reaction occurs in 35% of older patients taking ≥5 prescribed medications [13]. One study reported a 13% risk of potential drug interactions in cancer patients who received 2 medications, which increased to 82% in patients with ≥7 drugs [14]. Drug interactions contribute significantly to iatrogenic toxicities and may increase clinic visits by more than 50% in older patients [15,16]. Other significant risks with polypharmacy include increased hospitalization with longer length of stay, falls, and functional decline [2,5,10,17,18]. Almost one-third of unplanned hospitalizations can likely be prevented, if adverse drug events with polypharmacy can be avoided [19]. In addition, polypharmacy is an important cause of financial toxicity in cancer patients, which can affect patients’ ability to afford medications for cancer treatment, and even for basic needs of life [20].

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients are likely to be at a greater risk of polypharmacy and the complications from polypharmacy given the nature of AML (e.g. need for antimicrobial prophylaxis) and frequent use of intensive chemotherapy. However, data on polypharmacy among patients with AML is limited. It is important to explore the effects of polypharmacy in AML patients; polypharmacy can significantly increase toxicities while undergoing chemotherapy and may reduce the quality of life and survival. We, therefore, hypothesized that polypharmacy leads to worse overall survival (OS) in adults with AML, particularly in older adults.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective single-center study at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. All new cases of AML, other than acute promyelocytic leukemia, diagnosed or treated at our center from 2000 to 2016 were identified via a query of the electronic health record. The study was approved by the institutional review board.

We used the number of prescribed medications at the time of diagnosis to examine the outcomes of AML. Patients were divided into two groups: patients with polypharmacy (≥5 medications) versus those without polypharmacy (<5 medications). No distinction was made between scheduled and PRN medications and all medications were included in the analysis. We divided induction chemotherapy into intensive and low-intensity groups. Intensive chemotherapy included standard-dose cytarabine with anthracycline (7 + 3) and others. Low-intensity chemotherapy included hypomethylating agents (azacitidine or decitabine), low dose cytarabine, and others. HCT-CI was used in the study using the last pulmonary function test (PFT) on record. Among patients with no prior PFTs, the absence of a diagnosis of COPD or other pulmonary disease was interpreted as a normal score on PFTs.

Fisher’s exact test was used to identify the association of polypharmacy with baseline characteristics. OS, defined as the time from diagnosis of AML to death from any cause, was determined by the Kaplan–Meier method, and comparison of survival curves was done using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard models were used to determine the effect of polypharmacy on OS adjusting for other covariates. Polypharmacy was considered both as a continuous variable and dichotomized at 5. Also, the interaction of polypharmacy with age, Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), cytogenetics, HCT-CI, and initial chemotherapy was explored in the models. Due to the significant interaction of polypharmacy with age, final Cox models were performed for the entire cohort and separately for <60 years and ≥60 years old. p<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

We included 399 patients in our study – 49% (n = 197) with polypharmacy and 51% (n = 202) without polypharmacy (Table 1). Among the entire cohort of patients, 48% were female, 59% were ≥60 years, 96% were white, and 34% had adverse cytogenetics.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Polypharmacy (n, %) |

No polypharmacy (n, %) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <.0001 | ||

| <60 years | 46 (23.4) | 118 (58.4) | |

| ≥60 years | 151 (76.6) | 84 (41.6) | |

| Sex | .6 | ||

| Female | 98 (49.7) | 94 (46.8) | |

| Male | 99 (50.3) | 107 (53.2) | |

| Race | .4 | ||

| White | 190 (97) | 189 (95) | |

| Non-white | 6 (3) | 10 (5) | |

| HCT comorbidity index at diagnosis | <.0001 | ||

| 0 | 52 (27.2) | 109 (55.1) | |

| 1–2 | 52 (27.2) | 36 (18.2) | |

| 3–4 | 60 (31.4) | 50 (25.2) | |

| ≥5 | 27 (14.2) | 3 (1.5) | |

| KPS at diagnosis | <.0001 | ||

| <60 | 25 (13) | 6 (3.1) | |

| 70–80 | 76 (39.6) | 44 (23.1) | |

| 90–100 | 91 (47.4) | 141 (73.8) | |

| Cytogenetic risk categories | .01 | ||

| Favorable | 10 (5.7) | 18 (9.3) | |

| Intermediate | 94 (53.4) | 122 (63.2) | |

| Adverse | 72 (40.9) | 53 (27.5) | |

| Initial chemotherapy (n, %) | <.0001 | ||

| Intensive | 111 (56.3) | 163 (80.7) | |

| Low intensity | 60 (30.5) | 27 (13.4) | |

| None | 26 (13.2) | 12 (5.9) | |

| HCT performed (n, %) | <.0001 | ||

| Yes | 33 (17.4) | 74 (37.4) | |

| No | 149 (78) | 119 (60) | |

| 30-day OS (%, range) | 70 (63–76) | 86 (81–90) | <.001 |

| Age <60 | 85 (70–92) | 93 (87–97) | |

| Age ≥60 | 66 (58–73) | 76 (66–84) | |

| 90-day OS (%, range) | 51 (44–58) | 76 (69–81) | <.001 |

| Age <60 | 69 (53–80) | 88 (81–93) | |

| Age ≥60 | 46 (38–54) | 58 (46–68) | |

| 1-year OS (%, range) | 29 (22–35) | 49 (42–57) | .09 |

| Age <60 | 37 (23–51) | 65 (55–73) | |

| Age ≥60 | 26 (19–33) | 27 (18–37) | |

HCT: hematopoietic cell transplant; KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status; OS: overall survival.

The median number of medications for the entire cohort was 4 (range 0–39); 8 medications (range 5–39) for patients with polypharmacy vs. 2 (range 0–4) for those without polypharmacy. Significantly more patients with polypharmacy, compared to those without polypharmacy, were ≥60 years (77 vs. 42%, p<.0001). Patients with polypharmacy were more likely to have KPS of ≤80 (53 vs. 26%, p<.0001), hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) comorbidity index (HCT-CI) of ≥5 (14 vs. 1%, p<.0001), and adverse cytogenetics (41 vs. 27%, p=.01). A smaller proportion of patients with polypharmacy received intensive chemotherapy (56 vs. 81%, p<.0001) and underwent HCT (17 vs. 37%, p<.0001). However, only age, and not KPS, cytogenetics, HCT-CI, and initial chemotherapy had significant interaction with polypharmacy (p=.013).

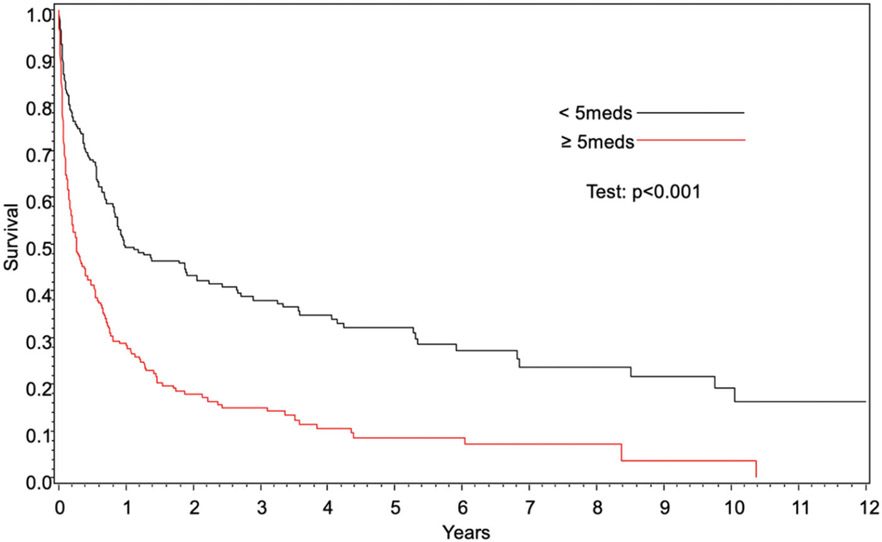

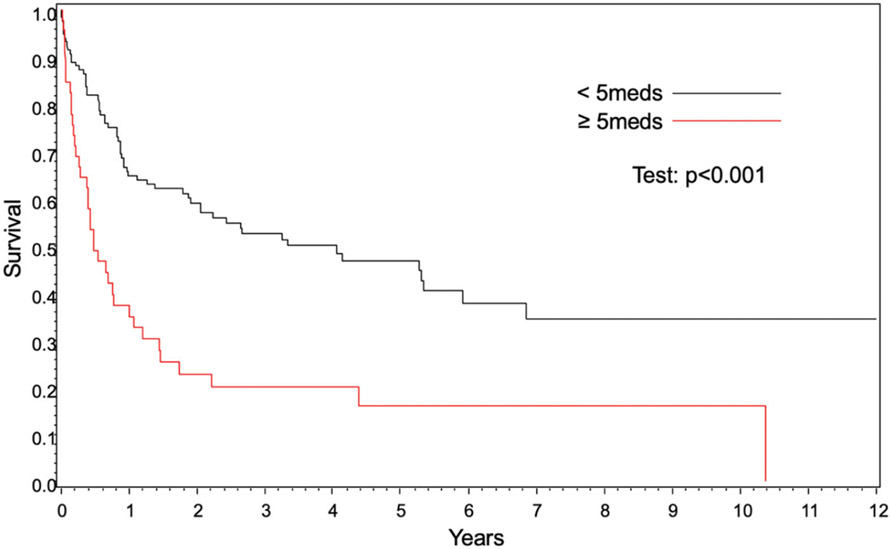

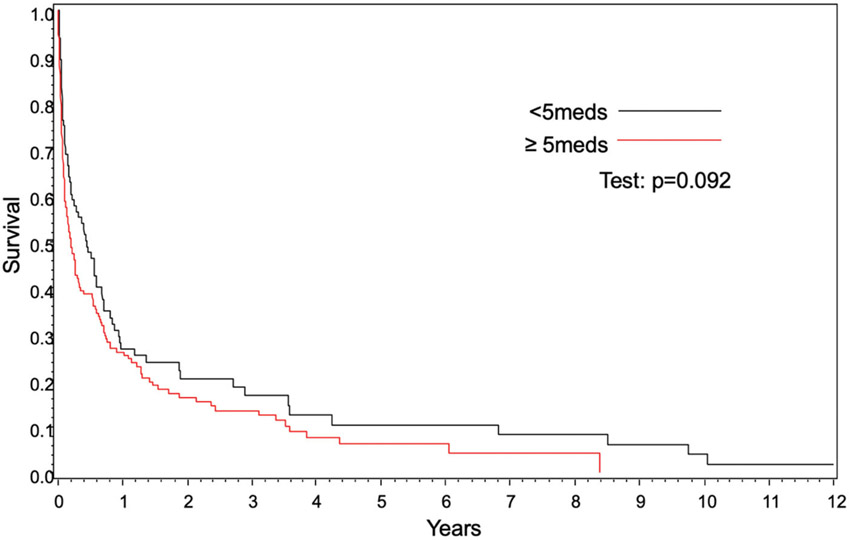

OS was significantly worse in patients with polypharmacy compared to those without polypharmacy (hazard ratio [HR] 1.34, (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–1.77], p=.03) (Figure 1, Table 1). Polypharmacy conferred worse OS in patients <60 years of age (37 vs. 65% at 1 year, p<.001); however, OS was similar in patients ≥60 years (26 vs. 27% at 1 year, p=.09) (Figures 2 and 3). In 2 separate multivariate analyses, polypharmacy was associated with worse OS in patients <60 years of age (HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.21–3.15) but not in patients ≥60 years (HR 1.12, 95% CI 0.81–1.57) (Tables 2 and 3). The risk of death for patients with polypharmacy was consistently higher than those without polypharmacy at 6 months (HR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.6), 9 months (HR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.8), and 12 months (HR 2.6, 95% CI 1.6–4.3).

Figure 1.

Overall survival based on polypharmacy.

Figure 2.

Overall survival for age <60 years based on polypharmacy.

Figure 3.

Overall survival for age ≥60 years based on polypharmacy.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival.

| Parameter | Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p Value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Polypharmacy (≥5 vs. <5) | 2.9 (1.6–2.6) | <.0001 | 1.9 (1.2–3.1) | .006 |

| Age ≥60 vs. <60 | 2.6 (1.04–3.3) | <.0001 | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | .0001 |

| KPS < or = 80 vs. 90–100 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | .001 | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | .5 |

| HCI ≥3 vs. 0–2 | 1.6 (1.3–2.1) | <.0001 | 1.3 (1.03–1.7) | .02 |

| Intermediate vs. adverse cytogenetics | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | <.0001 | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | <.0001 |

| Favorable vs. adverse cytogenetics | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | .0001 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | .005 |

| No chemotherapy vs. intensive chemotherapy | 8.3 (5.6–12.2) | <.0001 | 7.8 (5–12.2) | <.0001 |

| Low intensity vs. intensive chemotherapy | 3.1 (2.3–4.1) | <.0001 | 1.9 (1.4–2.7) | <.0001 |

| HCT, Yes vs. No | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | <.0001 | ||

CI: confidence interval; KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status; HCI: hematopoietic cell transplant comorbidity index; HCT: hematopoietic cell transplant.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of overall survival for different age groups.

| Parameter | Age <60 years |

Age ≥60 years |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p Value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Polypharmacy (≥5 vs. <5) | 1.9 (1.2–3.1) | .006 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | .4 |

| KPS < or = 80 vs. 90–100 | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | .5 | 1.06 (0.7–1.4) | .6 |

| HCI ≥3 vs. 0–2 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | .8 | 1.4 (1.08–2) | .01 |

| Intermediate vs. adverse cytogenetics | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | .01 | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | .0001 |

| Favorable vs. adverse cytogenetics | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | .1 | 0.3 (0.09–1.05) | .06 |

| No chemotherapy vs. intensive chemotherapy | 13.3 (3.6–49.3) | <.0001 | 7.1 (4.3–11.8) | <.0001 |

| Low intensity vs. intensive chemotherapy | 4.6 (2.1–10.1) | .0001 | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) | .002 |

CI: confidence interval; KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status; HCI: hematopoietic cell transplant comorbidity index.

Polypharmacy, as a continuous variable, conferred worse OS in cox regression multivariate analysis (HR 1.1, 95% CI 1.07–1.1). Other significant factors included older age (as a continuous variable), KPS ≤80, adverse cytogenetics, HCT-CI ≥3, and less intense or no chemotherapy.

Discussion

In our study, polypharmacy was noted in half of the patients with an average of 8 medications. Patients with polypharmacy were older, had greater HCT-CI and adverse cytogenetics, and were less likely to receive intensive chemotherapy and HCT. Polypharmacy had negative impact in OS of AML patients. Interestingly, when stratified by age, there was negative impact of polypharmacy on patients aged <60 years but no impact on patients ≥60 years of age.

Prevalence of polypharmacy has been variable in different studies and may range from 10 – 95%, especially in older patients with cancer [3,10,12,20-24]. In most studies, 8–9 was the average number of medications in cancer patients, and as many as 43% of patients took ≥10 medications [3,8,10,12,24]. Hanigan et al. reported use of >20 drugs, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements, in 10% of patients during chemotherapy [12]. More than half of cancer patients are known to use supplements and alternative medicines [8,23,25]. There has been one prior study in AML in older adults. In this study, polypharmacy was noted in 38% of patients at the time of admission for induction chemotherapy, which increased to 68% in patients who survived induction and were discharged from the hospital [26].

Our findings of association of polypharmacy with poor performance status and higher comorbidity burden align well with existing literature. In addition, patients with polypharmacy are more likely to have increased disabilities, and frailty [10,11]. In our analysis, polypharmacy was associated with adverse cytogenetics. The exact reason is unclear and has not been reported in the literature. Adverse cytogenetics, which confers worse prognosis in AML, may have influenced the outcomes in patients with polypharmacy [27-30]. No study has analyzed the effects of polypharmacy on intensive chemotherapy and HCT in AML; however, poor functional status and multiple comorbidities, which are associated with polypharmacy, negatively impact receipt of intensive chemotherapy and HCT [31,32]. Other factors associated with polypharmacy such as increased drug interactions with more grade III/IV toxicities and chemotherapy-related side effects can have important implications in AML treatment [33]. This may lead to treatment delay or dose reduction of chemotherapy, and subsequently decreased chance of remission and HCT [5,26]. Additionally, polypharmacy usually becomes worse with initiation of chemotherapy and supportive care.

Our results confirm the hypothesis of negative impact of polypharmacy on OS in AML. Interestingly, however, there was negative impact of polypharmacy on patients aged <60 years but no impact on patients ≥60 years of age. Prior studies in different cancer types have demonstrated mixed results. One study in older non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients reported reduced progression-free survival and worse survival with increased grade ≥3 toxicity, while a meta-analysis of phase II/III studies in ovarian cancer patients 21–83 years of age found increased overall grade ≥3 toxicity with polypharmacy without any effect on OS [5,34]. Only one study has evaluated the effects of polypharmacy in AML patients >60 years of age which reported lower remission rates, increased 30-day mortality, and worse OS with polypharmacy [26]. To the best of our knowledge, no study has analyzed the effect of polypharmacy in adult AML patients <60 years of age.

Several potential explanations may account for varying effects of polypharmacy based on age. Older patients with AML commonly have significant comorbidities and poor performance status, higher proportion of adverse cytogenetics, and decreased chances of receiving intensive chemotherapy and HCT [31,32,35]. These factors are known to independently impact the OS and thus, older patients may have worse prognosis anyway, hence the effects of polypharmacy may get diluted. Conversely, younger patients, particularly those without polypharmacy, are usually fit and more likely to receive intensive chemotherapy and HCT [32]. Younger patients on multiple drugs may have greater drug interactions and toxicities, thus reducing the benefit from intensive chemotherapy [13,15,21]. In contrast to older adults, comorbidities seem to maintain independent prognostic importance in younger patients. Also, polypharmacy in younger patients may be reflective of early onset of comorbidities which accumulate over the years and may lead to suboptimal management of cancer, pain, and mental health [36-38]. These factors can also decrease therapy adherence [39].

Our study is limited due to its single-center retrospective design with heterogeneous patient characteristics and different chemotherapy regimens. Our data included prescribed drugs and may not have accurately captured over-the-counter medications, herbs, or other supplements not disclosed readily by patients. We analyzed the total number of medications but could not ascertain the appropriateness of the medications on a retrospective chart review. Toxicities related to polypharmacy could not be assessed reliably in a retrospective fashion. However, we demonstrate an association between polypharmacy and OS including the use of chemotherapy and HCT.

Conclusion

While traditionally older adults are considered to be at a greater risk of polypharmacy, our study highlights that the effect of polypharmacy can be important in younger adults with AML. Given the impact of polypharmacy on OS, patients with newly diagnosed AML should be assessed for appropriateness of prescribed and over the counter medication. Whether active deprescribing of inappropriate medicines can improve outcomes need further studies.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, 1 U54 GM115458, which funds the Great Plains Institutional Development Award (IDeA) Clinical Translational Research (CTR) Network, and the Fred and Pamela Buffett Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute [P30 CA036727].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- [1].Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, et al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):230–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Halli-Tierney AD, Scarbrough C, Carroll D. Polypharmacy: evaluating risks and deprescribing. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(1):32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Turner JP, Jamsen KM, Shakib S, et al. Polypharmacy cut-points in older people with cancer: how many medications are too many? Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(4):1831–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Haider SI, Ansari Z, Vaughan L, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in Victorian adults with intellectual disability. Res Dev Disabil. 2014;35(11):3071–3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lin RJ, Ma H, Guo R, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients is associated with reduced survival and increased toxicities. Br J Haematol. 2018;180(2):267–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jokanovic N, Tan ECK, Dooley MJ, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(6):535.e1–535.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Safran DG, Neuman P, Schoen C, et al. Prescription drug coverage and seniors: findings from a 2003 national survey. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(Suppl Web Exclusives):W5-152–W5-W166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sokol KC, Knudsen JF, Li MM. Polypharmacy in older oncology patients and the need for an interdisciplinary approach to side-effect management. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2007;32(2):169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Puts MTE, Costa-Lima B, Monette J, et al. Medication problems in older, newly diagnosed cancer patients in Canada: how common are they? A prospective pilot study. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(6):519–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Prithviraj GK, Koroukian S, Margevicius S, et al. Patient characteristics associated with polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing of medications among older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3(3):228–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Turner JP, Shakib S, Singhal N, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in older people with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(7):1727–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hanigan MH, Dela Cruz BL, Thompson DM, et al. Use of prescription and nonprescription medications and supplements by cancer patients during chemotherapy: questionnaire validation. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2008;14(3):123–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279(15):1200–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Goldberg RM, Mabee J, Chan L, et al. Drug-drug and drug-disease interactions in the ED: analysis of a high-risk population. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(5):447–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18,820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329(7456):15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhan C, Arispe I, Kelley E, et al. Ambulatory care visits for treating adverse drug effects in the United States, 1995–2001. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(7):372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Badgwell B, Stanley J, Chang GJ, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment of risk factors associated with adverse outcomes and resource utilization in cancer patients undergoing abdominal surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108(3):182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sharma M, Loh KP, Nightingale G, et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in geriatric oncology. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(5):346–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Marcum ZA, Amuan ME, Hanlon JT, et al. Prevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Balducci L, Goetz-Parten D, Steinman MA. Polypharmacy and the management of the older cancer patient. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(Suppl 7):vii36–vii40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lees J, Chan A. Polypharmacy in elderly patients with cancer: clinical implications and management. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(13):1249–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Maggiore RJ, Dale W, Gross CP, et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults with cancer undergoing chemotherapy: effect on chemotherapy-related toxicity and hospitalization during treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(8):1505–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Maggiore RJ, Gross CP, Hurria A. Polypharmacy in older adults with cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15(5):507–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nightingale G, Hajjar E, Swartz K, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-led medication assessment used to identify prevalence of and associations with polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use among ambulatory senior adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1453–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Werneke U, Earl J, Seydel C, et al. Potential health risks of complementary alternative medicines in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(2):408–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Elliot K, Tooze JA, Geller R, et al. The prognostic importance of polypharmacy in older adults treated for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Leuk Res. 2014;38(10):1184–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Byrd JC, Mrózek K, Dodge RK, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461). Blood. 2002;100(13):4325–4336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Grimwade D, Hills RK, Moorman AV, et al. Refinement of cytogenetic classification in acute myeloid leukemia: determination of prognostic significance of rare recurring chromosomal abnormalities among 5876 younger adult patients treated in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials. Blood. 2010;116(3):354–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Results of intensive chemotherapy in 998 patients age 65 years or older with acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: predictive prognostic models for outcome. Cancer. 2006;106(5):1090–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Cassileth PA, et al. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2000;96(13):4075–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bhatt VR, Gundabolu K, Koll T, et al. Initial therapy for acute myeloid leukemia in older patients: principles of care. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59(1):29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bhatt VR, Chen B, Lee SJ. Use of hematopoietic cell transplantation in younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a National Cancer Database Study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(7):873–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hamaker ME, Seynaeve C, Wymenga ANM, et al. Baseline comprehensive geriatric assessment is associated with toxicity and survival in elderly metastatic breast cancer patients receiving single-agent chemotherapy: results from the OMEGA study of the Dutch Breast Cancer Trialists’ Group. Breast. 2014;23(1):81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Woopen H, Richter R, Ismaeel F, et al. The influence of polypharmacy on grade III/IV toxicity, prior discontinuation of chemotherapy and overall survival in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140(3):554–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bhatt VR, Chen B, Gyawali B, et al. Socioeconomic and health system factors associated with lower utilization of hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(10):1288–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Murphy CC, Fullington HM, Alvarez CA, et al. Polypharmacy and patterns of prescription medication use among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2018;124(13):2850–2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shay LA, Parsons HM, Vernon SW. Survivorship care planning and unmet information and service needs among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(2):327–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wu X-C, Prasad PK, Landry I, et al. Impact of the AYA HOPE comorbidity index on assessing health care service needs and health status among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(12):1844–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Butow P, Palmer S, Pai A, et al. Review of adherence-related issues in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4800–4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]