Summary

Background

Little is known about how patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) experience their symptoms, receive care, and cope with their disease. Patients commonly seek peer support from online communities, which provide insights on unmet needs and barriers to care. We performed a qualitative analysis of electronic health forums to characterize patient-to-patient conversations about EoE symptoms and the experience of disease.

Methods

We identified three publicly accessible electronic health forums hosting EoE communities. Conversation threads posted between July 2018 and June 2020 were coded using emergent and a priori codes based on the THRIVE conceptual framework of coping with chronic illness.

Results

Of 659 threads (4,933 posts) collected over two years, a random sample of 240 threads (30 per 3-month quarter) were selected for analysis. Thematic saturation was reached after 172 threads. Patient experience of EoE was driven by their perspectives in four key domains: (i) perception of EoE as episodic rather than chronic, (ii) treatment choices, (iii) personal definitions of success in the disease, and (iv) views of providers.

Conclusion

Online health communities are a valuable and unfiltered source of patient perspectives that can be used to understand patient needs and goals. EoE patients interpret their disease as sporadic events and lack reliable sources of knowledge, which may influence how patients prioritize treatment. If providers are to succeed in providing high-quality EoE care, they need to equip themselves with evidence-based knowledge, engage in shared decision making, and look outside of clinical settings to recognize barriers to disease management.

Keywords: barriers, chronic, decision making, knowledge, preferences, symptoms, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has emerged over the last three decades as a leading cause of dysphagia, esophageal food impactions, and esophageal dysfunction in both adults and children worldwide.1,2 As our understanding of this new chronic disease evolves, evidence-based clinical guidelines for EoE recommend maintenance treatments to minimize symptoms and prevent complications of disease progression.3–5 Currently available effective treatments include elimination diet, medications such as topical corticosteroids and proton pump inhibitors, and endoscopic dilation.6 However, EoE quickly recurs after treatment is withdrawn and challenges of patient loss to follow-up, poor adherence to treatment, and long-term disease control are well documented.7–10 Untreated disease and failure to adhere to recommended treatments are major risk factors for esophageal strictures and recurrent food impactions, as well as a significant burden on health-related quality of life.11–14

This inconsistency between recommended and actual EoE care prompts a need to understand patient perspectives on disease management, particularly as knowledge about the disease pathophysiology, risk, and available treatments evolves. Despite growing literature on patient-reported outcomes in EoE, little is known about how patients experience and interpret their disease.15 Described in prior survey studies, EoE patients value symptom improvements and shared decision making (SDM) with their providers, but still suffer from unmet needs across medical and socioemotional domains.16–18 Outside of these curated research settings, we are unaware of how EoE patients experiences their disease. Existing knowledge gaps in EoE care include how patients perceive and describe their symptoms, define successes in managing their chronic disease, access and receive care, and use these experiences to make decisions about disease control. A poor understanding of how patients interpret their disease may impact not only how providers view adherence to therapy, disease control, and patient quality of life, but also hinders how providers interact with and educate patients, and manage this disease. Gaining insight into patients’ values and beliefs about their disease is important for many practical reasons (e.g. to improve clinical outcomes and quality of EoE care). First for patients, this knowledge can be used to increase uptake of treatments by addressing misconceptions and tailor therapies to patient preferences. Second, these insights may inform patient–provider interventions to augment the collaborative management of this chronic disease. Third, in a new disease where clinical ambiguity exists around evolving treatments and natural history, understanding the illness through the lens of those who experience it is essential to managing it.

EoE patients may use online sources to seek peer support and these virtual forums serve as unguarded data sources that provide raw insights on barriers to care and communication. A form of social media, online health communities provide a way for patients to exchange health information, share experiences, and receive social support.19,20 As a result, these forums represent an unexplored source of patient-generated information which can shed light on unmet needs and barriers in disease management.21,22 In contrast to surveys and structured interviews, often of participants recruited from specialty clinics or advocacy groups, mining these unsolicited sources reduces self-selection and researcher biases, and offers a different and perhaps more complete view of the spectrum of patients with EoE. Therefore, we aimed to characterize patient-to-patient conversations about EoE symptoms and the experience of disease using qualitative analysis of online health forum discussions. We hypothesized that these discussions would reveal new insights to how patients view EoE and factors that drive disease management outside of a curated research setting.

METHODS

Data collection

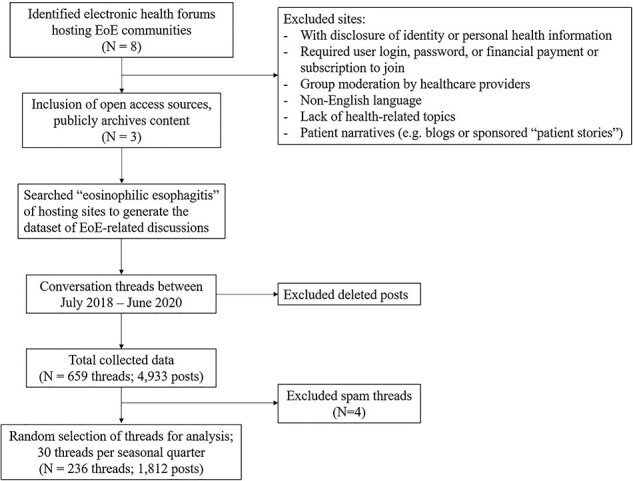

As social media broadly includes any interactive online community, ranging from networking sites (e.g. Facebook, LinkedIn), content communities (e.g. Instagram, YouTube), collaborative projects (e.g. Wikipedia), and blogs (e.g. Twitter, WordPress), we restricted our data collection to online forums where direct patient-to-patient conversations occur. We identified electronic health forums hosting EoE communities, restricting to open access sources of publicly archived content without identifiable personal health information or requirements for a user login, password, or subscription (Fig. 1).23 Exclusion criteria were group moderation by healthcare providers, non-English language, lack of health-related topics (e.g. responses to lay press), and patient narratives in the form of blogs or sponsored “patient stories”. To preserve the privacy of patient peer support groups, we excluded online communities that required financial payment or subscription to join, creation of a secure user account and login for access (e.g. Facebook, Twitter), or disclosure of identity or personal health information. The dataset of EoE-related discussions was built by searching for “eosinophilic esophagitis” in the search tab of sites hosting virtual communities. Other search terms related to symptoms or treatments (e.g. dysphagia, diet, steroids) were not applied in order to increase specificity of the search and limit potentially confounding threads about other medical conditions with similar symptoms or treatments, particularly as a diagnosis of EoE could not be verified by individual endoscopic and histologic data. A total of 790 threads (5,545 posts) dating back to 2007 were collected across three online forums (Reddit, HealingWell, HealthBoards). As the gross majority of threads (659; 4,939 posts) were created in the recent two years, conversation threads posted between July 2018 and June 2020 consisting of original posts and responses related to EoE (including diagnosis, testing, risks, symptoms, treatment, provider interactions) were collected for analysis. Posts deleted by site administrators or individuals were inaccessible to each site’s search function, thus unavailable for inclusion. Minor typographical errors within individual posts were corrected for clarity. This study was deemed to be exempt by the University of Michigan Medical Institutional Review Board as all data were publicly archived discourse.

Fig. 1.

Data collection search strategy.

Data analysis

To capture recent patient experiences, ensure equal distribution of sampling per year, and account for potential seasonal variation in symptoms and disease severity, we randomly selected 30 threads per seasonal quarter, comprising 120 threads per year (July 2018–June 2019, July 2019–June 2020), totaling 240 threads over the last two years for analysis and coded conversation threads using thematic analysis. We estimated that 30 threads would allow us to reach thematic saturation, after which few new topics are discovered.24 After reading all 240 threads, we eliminated four spam threads that were produced by organizational accounts of bots. Ultimately, 236 total threads (1,812 posts) were included. An iterative process of content analysis was used to identify themes within the posts. A preliminary list of codes was developed based on the researchers’ clinical knowledge and the THRIVE (Therapeutic interventions, Habit and routine, Relational-social factors, Individual differences, Values and beliefs, Emotional factors) conceptual framework of coping with chronic illness.25 Conversation threads were coded using both those a priori codes and emergent codes. After reading the posts, we developed and iteratively adjusted a list of relevant codes. When a new theme was added, previously analyzed threads were reexamined. Because the unit of analysis was online conversation threads among anonymous posters, the unique characteristics of individuals were unknown and thus not linked to individual statements for the purpose of analysis. We planned to sample additional threads if thematic saturation was not achieved, however, thematic saturation was reached after 172 threads and an additional 68 threads were coded to confirm that no additional themes emerged. A total of 1,812 posts representing 462 people were included. Using thematic analysis, we combined the codes into higher level categories and identified relationships among the categories. All coding was performed by one coder in consultation with the authorship team using Dedoose 8.0.35 software (SocioCultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

RESULTS

The 21 codes developed in the analysis were merged into four overarching themes, highlighting the perspectives driving patient management of EoE: (i) perception of EoE as episodic rather than chronic, (ii) treatment choices, (iii) defining success in disease, and (iv) views of providers.

EoE as episodic rather than chronic

When discussing their condition in online EoE communities, outside of a clinical setting, individuals commonly described their symptoms as “flares”—self-limiting attacks rather than a constant, chronic condition. Patients often reported feeling well between these episodes and were unaware of why or when these episodes would suddenly come on or resolve (Table 1, quote 1A–1B). For example, one individual recounted their typical eating habits, intermittent exacerbations, and return to their previous state (Table 1, quote 1B). Symptoms of dysphagia and chest pain were interpreted as acute worsening, often suggestive of an esophageal food impaction or near-impacted food bolus. Although these episodes may be infrequent, many described these acute symptoms as disruptive and often times traumatic (Table 1, quotes 1C–1E). Episodes of dysphagia or challenges around eating were viewed as unpredictable, without clear triggers, and often self-managed with (i) strategies and home remedies to resolve acute symptoms and (ii) learned eating behaviors to prevent these episodes.

Table 1.

EoE as episodic rather than chronic: representative quotations from selected posts

| Theme: EoE as episodic rather than chronic | |

|---|---|

| Sporadic and temporary nature of flares | 1A: “I was diagnosed in May, and after a few week-long flare ups the summer went fairly smoothly. Unfortunately, a few days after I moved into to my new house I had a really bad incident with food getting stuck that lasted for hours, this flare-up is still going on.” 1B: “I am actually very fortunate with my EOE in that, while anything I eat or drink always takes forever to actually fully swallow, I will go for quite a while between times where things actually won’t go down and so they just come back up. Oftentimes once I throw up, I’ll have trouble with things just not going down any time I eat, no matter what it is, for anywhere from a day to a few weeks and then things will go back to ‘normal’.” |

| Acute flares as disruptive and traumatic | 1C: “I went out to dinner tonight with some family at a restaurant, and had another flare-up of my EOE. I had to go to the restroom multiple times, and kept cough and vomiting… I hate when incidents like this happen, especially in public.” 1D: “It’s taking so damn long and every time I get another flare up I never want it to happen again. It takes me months just to get the courage to try something else in case I get another flare up:/” 1E: “Usually if I have trouble swallowing it goes away within 2 minutes...today I couldn’t get anything down, even water, for about an hour. I was scared, embarrassed, frustrated, and I couldn’t be there for my two kids...” |

| Self-management: treating acute symptoms | 1F: “Normally when my EOE flares up, it happens in the first couple bites of a meal, and then goes away in less than 10 minutes after I vomit once or twice.” 1G: “If food gets stuck #1 thing is to stay calm. I sit up, drink some tea, (or Diet Coke, its proven to help dissolve the food) if you give it time it will go down” 1H: “So, I got food stuck in my esophagus again last night. Happens fairly regularly. It was bad enough that I couldn’t swallow any fluids. So I tried the usual, vomit it back up, force it down, some olive oil, some fizzy drink. It was going nowhere. So I thought I’d try and dissolve it using some digestive enzymes; try to recreate the stomach juices in my esophagus... every few hours I mixed a capsule of enzymes with a small amount of coke, forced it down and let it sit there. Sure enough, this morning, the meat that was stuck was much softer and I was able to use the other techniques to clear my esophagus. It’s still painful obviously, but didn’t require a trip to the hospital. So was actually much quicker. (And cheaper if you’re not in the UK)” |

| Self-management: prevention | 1I: “I now really do take it very slow with new foods, meat products, and anything that is difficult to eat (I chew completely/smaller bites) and I have water ready to go always… I have been able to eliminate most scary incidences just by eating smaller/slower/chewing food completely, I also removed steak/harder meats from foods I eat).” 1 J: “think about foods that tend to cause incidents for you. For me, its things I can’t super easily chew into very small bits. Steak/cuts of beef is the worst for me (I never eat it anymore, not worth the risk)” 1 K: “For meat, best thing to do for me is cook it for a really long time. Get a slow cooker (6 hours) or Instapot (1 hour to 1.5 h) this usually breaks down the protein in the meat that gives me issues and I’m able to eat meat at every meal.” |

Self-management—treating acute symptoms: “Any remedies for while you’re choking”?

This view of EoE as distinct events was also apparent as people with EoE commonly develop and use “do-it-yourself” techniques to manage acute symptoms. Several endorsed various strategies and shared advice on how to relieve these attacks, often as a tradeoff to seeking immediate medical care. How effectively patients with EoE can deal with, respond to, and tolerate these episodes plays a role in the overall disease management in how they may value seeking treatment. These “as needed” methods include forceful regurgitation, drinking liquids (e.g. hot water, soda), deep breathing, transitioning to liquid or soft foods (Table 1, quotes 1F–1H). Searching for answers, those with EoE also shared and explored less common creative tips including positional changes (e.g. standing up, turning the neck, pulling shoulders back), over the counter medications (“make myself throw up and take a Benadryl”), relaxation techniques (“take some deep breaths and try to relax”), alternative therapies (“take inhaled CBD… it’s a great anti-inflammatory”), and potentially harmful advice (e.g. digestive enzymes or supplements, eating POP ROCKS® candy with soda, or “waiting it out” at home).

Self-management—prevention: “Take small bites and chew your food well”

Despite the intermittent and unpredictable nature of symptoms and viewing the disease as isolated episodes, many adopt adaptive eating behaviors around eating to limit their symptoms and prevent future events (Table 1, quotes 1I–1K). These habits may be intentional or unconsciously developed, and include avoidance of particular foods, altering the consistency of food, eating slowly, and chewing carefully. How patients view their symptoms, and therefore their disease, as a series of distinct events or episodes influences how they manage the disease, commonly with “as needed” strategies and changing their eating habits. Hidden, and differing from provider views, these attitudes and self-management tactics shed light on minimizing symptoms and resultant delays in diagnosis and treatment that are common in EoE care.

Treatment choices

The domain of treatment choices includes patients’ opinions about and use of dietary therapies, endoscopic dilation, and medications—including topical corticosteroids (TCS) and proton pump inhibitors (PPI). Patients seek treatment in various forms, ranging from over-the-counter PPIs to invasive procedures. Individuals with EoE discussed how these standard treatments are used and valued, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of each (For PPI and dilation, see Supplementary Results, Supplementary Results). As they struggle through multiple treatments, patients share their experiences and actively seek advice about their options. Individuals commonly describe challenges in navigating the various treatments and seek peer support and recommendations (Table 2, quotes 2A–B).

Table 2.

Treatment choices: representative quotations from selected posts

| Theme: Treatment choices | |

|---|---|

| Struggling between treatment choices | 2A: “So I just got my results back for my second endoscopy... was much improved from the first endoscopy and that they want me to continue taking budesonide… as someone who isn’t a fan of medication, I don’t feel like continuing it. I feel like going on a diet would be better for me, but I’m still torn on it. What should I do? Should I continue taking the medication, or should I try a diet?” 2B: “Anyone have some generalized methods of going through the elimination method? How I’d start”? |

| Topical corticosteroids | 2C: “I see much better relief with the [fluticasone]… I took it for around 4 months straight. I’ve been good so far. I’m thankfully no longer taking it, as my EE is in remission.” 2D: “I have taken Budesonide… in that dosage daily for about 3 months before my EoE went into remission, and then I would stop until I became symptomatic again… Budesonide was \*very\* effective when I took it, and in fact was the first treatment I ever took that completely eliminated my symptoms… So if you’re looking for an effective treatment, I would say it might be worth the risk. However, it (as far as I know/knew at the time) is not a permanent daily treatment.” 2E: “As soon as I got diagnosed, my dr. put me on a [fluticasone] inhaler. It worked amazingly. Symptoms completely gone… I really want to go off it... now that I’ve eliminated some foods, but even just as a temporary fix, something like that might help you function until you can get more tailored treatment later” 2F: “so far I’ve done dilation 4 times, and [pantoprazole] + [fluticasone]… And I’ve been “fine” (minimal impaction incidents) with just the meds as long as I take them *every day* like I should. Where I have problems is when I get too comfortable and stop taking the meds (or stop taking them regularly)—then I start having issues again within a year and have to remind myself that I can’t go off of them.” |

| Dietary therapy | 2G: “I turned down the steroid for now... I’d rather figure out what is triggering it first and see if we can get that under control.” 2H: “Doc prescribed Budesonide, but it feels to me like we’re just treating the symptoms instead of solving the problem.” 2I: “I have always opposed meds because I don’t like taking meds and I also feel as if there’s other more natural ways to control it.” 2 J: “I am on the sfed [six-food elimination] diet now and am hoping… I can pinpoint the food that’s causing this. I really am afraid of having to take steroids for the rest of my life and I want to avoid it if I can help it.” 2 K: “I’d be lying if I told you it was easy… While the new diet is stressful and depressing at first, the relief makes it all worth it. To be able to eat and not choke or be in horrible pain makes up for the relatively plain and repetitive meals I eat.” 2 L: “After being sick for 2 and a half years, I was diagnosed with EoE! …even though the diet is restrictive I am so glad to have answers. Don’t get me wrong though, it’s been hard!!!! I miss food so much sometimes, but the longer I’ve gone without it the less I’ve missed it… I haven’t felt this good in years!!! … The elimination diet is rough but hang in there! Being 18 and in college, it can be hard and expensive, but it’s worth it for sure. I feel great!” |

Topical corticosteroids: “as far as I know… is not a permanent daily treatment”

Many patients polarized non-PPI EoE treatments (TCS and diet elimination) either as quick fixes or maintenance therapies. They cited the immediate benefits of TCS, viewed as an effective treatment but often for the short-term. Several individuals called attention to a curative view of topical steroids, or using a short-course of treatment to get rid of the disease (Table 2, quote 2C). Others who used topical steroids temporarily appreciated its effectiveness but viewed the treatment as palliative or reducing the symptoms without removing the disease. For many who ascribed value to the medication to inducing disease control, also recognized its temporary use as a limitation when symptoms recurred (Table 2, quote 2D). For others, TCS were viewed as a temporizing method or bridge to alleviate symptoms before considering tailored therapies such as the elimination diet (Table 2, quote 2E). However, other individuals admitted to using daily medications and expressed an understanding of long-term disease control. For example, one individual reflected on their disease control on medications and recurrence of symptoms with decreased adherence (Table 2, quote 2F).

Dietary therapy: “I’d like to find the source instead of relying solely on medication.”

In contrast to medications, diet therapy was viewed as a tailored long-term or “natural” approach to identify the root cause and for many, preferred over using medications for this reason. Many who recognized EoE as a chronic disease preferred changing their diet over using long-term medications. Medications were viewed as covering up the problem and a crutch instead of addressing the cause of the disease. Many voiced their preferences for using dietary approaches over medications for fear of relying on lifelong medications and viewed dietary changes as a more permanent solution (Table 2, quotes 2G–2J. Although the diet therapy was universally described to be challenging and stressful, many reported that the trouble was worth the relief in symptoms and feeling well (Table 2, quotes 2K–2L).

As EoE is a relatively new disease, patients struggle to manage their disease by experimenting with potential therapies. Varying perspectives on these treatments give insight on how they use these therapies and shows the diversity of ways patients view their disease. These threads revealed a diversity in how patients use treatments ranging from daily medications or restrictive diets to periodic dilation retreatments. Some patients liked medications because they offered more immediate improvement whereas others discussed the desire to treat disease by identifying the root cause (i.e. diet). This diversity in how patients try and view treatments is important for providers to know and understand.

Defining success in disease: “Don’t expect that things will be ‘normal’ in the process”

Just as patients grapple with different treatment options, they also varied in how they define success, good outcomes, and disease objectives. Defining or assigning success in disease management was a way that some patients found meaning in living with their disease, as well as goals for how far they would go with treatments. This was commonly defined by improvement in symptoms and feeling healthy, ability to eat favorite foods, not relying on medications, living without fear, normal endoscopic and pathology results, or learning to cope with the disease. For many, disease success was defined as limiting how much the disease disrupts their daily life and minimizing symptoms, regardless of the cost. Specifically, enjoying favorite foods, improving symptoms, and avoiding a potentially fatal complication were cited by patients as factors that influence their decision to use a medication to treat disease (Table 3, quotes 3A–3B). Many defined success objectively through measured improvements in endoscopic features and histology. These positive test results served as rewards for using treatment and validated the therapies (Table 3, quotes 3C–3D). Although improving symptoms was worth the cost of using medications or dietary restrictions for many, weighing the risks of treatment and finding ways to cope without treatment was important to others. Different perceptions of risks and inconvenience versus benefit were discussed as factors in the decision to avoid treatments, interventions, or tests. Many instead valued adapting to their symptoms and for some, found comfort in this self-awareness and autonomy (Table 3, quotes 3E–3F). Acceptance of the chronic disease and learning to cope were ways that some found meaning in living with EoE. Many who use these online health communities also sought out and found positive peer support to reorient their definitions of disease success (Table 3, quote 3G).

Table 3.

Defining success in disease: representative quotations from selected posts

| Theme: Defining success in disease | |

|---|---|

| Minimizing symptoms | 3A: “All I really want is to take the right steroid & eat a big bowl of spaghetti without choking to death.” 3B: “Once I started taking omeprazole in the morning, my symptoms took about 6 weeks to go away. Beyond taking the pills, having EoE currently does not affect my life in any way.” |

| Objective improvements | 3C: “I took budesonide for 3 months and was very consistent with both time of day (not sure that matters) and making sure I took both doses correctly. At my first endoscopy they were unable to get the scope down, and after treatment my esophagus was measuring at a normal size and 0 eosinophils from biopsy results.” 3D: “I also take budesonide (4 vials per night) in a shot glass and mix with 4 packets of Truvia®… My EOE doctor changed me to this regime and my last endoscopy in March, I had zero eosinophils! Wooo. Took freaking forever to get to that one point. I remember choking on my own spit at one point.” |

| Adapting to symptoms | 3E: “I know everyone’s battle plans are different and conditions for each person are unique to them, but for me, I have difficulty swallowing (a ringed esophagus with a permanent narrowed stricture), I’ve had several upper-endos and every time the doctor is like, here take these drugs for the rest of your life, oh yeah, and take these other drugs (steroids) and just keep forking over money to us. I said no… for me, I didn’t want to go that route… I was diagnosed with moderate to severe EoE... I have been to the hospital a couple times now for food bolus impaction because of the ring, it sucks, but I have adapted as best as possible and I am always aware of what I’m eating, drinking, doing.”. 3F: “I also skipped the regular endoscopes. It felt too invasive for me. I can feel food going down, I know if it is going down easy, needs some help (water) or worse. Perhaps I’m a bad patient but that felt right for me:)” |

| Acceptance | 3G: “I wish I had adjusted my thinking much earlier in the process. You’ll need to adjust your definition of ‘normal’. It’s a manageable but chronic condition. Take all the steps. Do dilation if you need it and can. Take your meds religiously. Try an elimination diet to identify and remove the root cause of the reaction, if possible. But do not neglect the condition. And don’t expect that things will be “normal” in the process. The good news is that once you reset your expectations, routine, and what/how you eat, you’ll have minimal problems. And you’ll find joy in trying new and interesting foods that you might not have otherwise. Not to mention the interesting social dynamics that get created when you no longer center your socialization around food. It can be a positive journey.” |

Recognizing and addressing patient priorities in managing EoE is crucial to starting and optimizing effective treatment strategies. Patient-reported outcomes do not necessarily align with providers’ goals of symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement. Understanding how patients interpret the disease and define their own successes sets the stage for improving the quality of care for this chronic disease.

Views regarding providers: “Since EoE was discovered more recently, not all gastroenterologists even know what it is”

In contrast to provider-perceived barriers to EoE treatment (e.g. financial costs, convenience), patients frequently described their interactions with provider as drivers of the EoE care and specifically, negative encounters as barriers to disease management. Several patients described encounters with providers who lacked knowledge about the disease and its treatments. One patient described the need for knowledgeable gastroenterologists as a significant burden and limitation to disease control. Gastroenterologists were viewed by patients as uninformed and unaware of the disease, leaving patients feeling frustrated and potentially with untreated disease (Table 4, quotes 4A–4D). Providers’ lack of knowledge was reported as a reason for transitions of care and seeking second opinions. In many cases, patients felt better versed in disease management and could educate their doctor (Table 4, quote 4E).

Table 4.

View of providers: representative quotations from selected posts

| Theme: Views of providers | |

|---|---|

| Providers as unknowledgeable | 4A: “I got diagnosed a year and a half ago (I’m 20), and one of the most difficult things about this disease is that a lot of GI doctors will not be super knowledgeable about it”. 4B: “It seems a lot of doctors refuse to believe EoE is a real thing … Even the specialist who diagnosed me admitted he never came across this disease before and didn’t know much about it.” 4C: “This wasn’t even on the doc’s radar initially. He said he’s never actually diagnosed this disease before.” 4D: “I’m 19 and I was diagnosed in May and my first couple months of dealing with this as a student have been really rough too. It can feel very confusing because not every doctor/medical professional you communicate knows the specifics, in fact most don’t.” 4E: “I agree I feel like most doctors don’t really know much about EoE, I hope I’ll have better luck with a different doctor, and now that I know what this ‘disease’ is called… I can maybe give the doctor more insight in some way.” |

| Providers as unsupportive of patient choices | 4F: “I was diagnosed with EoE about 2 years ago... the GI doctor only wanted to treat it with [omeprazole] and had little faith in changing my diet to treat it. I was discouraged and never followed up with the doctor.” 4G: “My doc said I should try elimination but that it usually doesn’t work. I was under the impression it did help people. He said he suspects people have trouble sticking to diet so it ends up not working. He also gave me the steroid to swallow if I want to go that route. I guess I’ll give this diet a go but I need a really great book or recipes cause this sounds like it’ll suck.” 4H: “I was diagnosed with EOE at 17, and now at 25, have never had a good gastroenterologist. When I was diagnosed, at least in my area, knowledge of the condition was relatively new, so I went to two different GIs initially, neither of which was very helpful (one prescribed oral steroid pills which I could barely swallow, and the other lacked empathy and was only interested in an endoscopy twice a year).” 4I: “If your doctor is unsupportive and wishes to only medicate without lifestyle change, I would consider finding a new doctor whose values align with yours.” |

Despite recognizing provider inexperience in EoE, patients commonly encountered providers who were unsupportive of patient choices. Doctors are viewed as close-minded to therapies outside of their own recommendations, skeptical, and unsympathetic. The lack of a collaborative patient–provider relationship resulted in being patients’ loss to follow-up or trying therapies independently (Table 4, quotes 4F–4H). Conversely, EoE patients value collaborative relationships with their providers particularly in the setting of navigating this emerging disease and seek out those who value SDM (Table 4, quote 4I).

DICSUSSION

Online health communities are a valuable and unfiltered source of patient perspectives and disease-related language that can be used to understand patient needs and goals, improve education, and facilitate communication. In this qualitative study, people with EoE reported patient perspectives that drive management of their EoE across domains of viewing the disease as episodes rather than a chronic disease, treatment choices, definitions of disease success, and views of providers. Most viewed their disease experience as multifaceted with both positive and negative factors that impact how their disease is managed.

An important finding in our study is that people with EoE report varying views on disease chronicity, treatment courses and duration, and how they define disease success—many of which may diverge from provider views and clinical guidelines, thus highlighting a significant knowledge gap in our understanding of how patients perceive their disease and a vital need for patient-centered care in EoE.23,26–29 Patients commonly refer to the disease in the context of acute flares and episodes. This false conception of EoE as an intermittent condition instead of a chronic disease results in using techniques to resolve temporary symptoms, and applying medications and endoscopic dilation for short-term relief. Interestingly, patients reported using adaptive behaviors to prevent future episodes, a well-documented phenomenon practiced by EoE patients, but this did not necessarily translate into interpreting the disease as requiring long-term treatment.30 An exception to this was how dietary therapy is viewed as targeting the cause of the disease by identifying and avoiding food triggers. This contrast highlights opportunities to correct misconceptions about disease chronicity and in turn, how treatments are chosen and applied. Although providers may recognize the adaptive eating behaviors common to EoE, our findings showcase how patients’ understanding of EoE as a sporadic condition versus chronic disease differ from that of providers. Although a patient’s unawareness of their chronic symptoms and compensatory eating practices has implications for how they seek care, monitor, or interpret their symptoms, and use or decline treatments, a provider’s lack of understanding of patient disease perception is a barrier to providing quality care.

Although guidelines recommend assessing treatment endpoints in three domains—symptoms, histology, and endoscopic findings—these may be inconsistent with how patients perceive disease success and their individual values. In a recent survey of Swiss EoE patients, Safroneeva et al. showed that over 90% prioritized improvement of symptoms and quality of life as treatment goals.18 In our prior work, we demonstrated that patients with EoE are motivated to treat their disease to prevent complications or worsening of disease and ongoing symptoms. Barriers were specific to topical steroids (side effects, financial cost), dietary therapy (inconvenience of a restrictive diet), and endoscopic dilation (belief that it is a high risk procedure, discomfort).16 Our current findings build on this to include patient preferences for avoiding certain treatments and disease acceptance, bringing to light how patient goals and priorities may differ from providers’ treatment goals, and ultimately guide disease management. When it comes to decision making around specific treatment choices or even delaying or deferring treatment, many concrete (e.g. financial cost, inconvenience) and abstract (e.g. risk perception, self-efficacy) factors play a role. Thus there are opportunities not only to provide education, but also to elicit patient preferences to elect management plans concordant with their values and attitudes. Particularly when faced with multiple therapies, providers need awareness and understanding of how and why patients choose or defer treatment. Informed by our findings, future research and interventions should focus on patient preferences for disease management and improved patient–provider communication as foundations of to providing quality care.

Our finding of patients’ views on providers as unknowledgeable and unsupportive calls for attention and highlights areas to target provider-based interventions in EoE care. As there are currently no standardized ways of discussing EoE management, patients receive information by self-directed learning from online resources such as advocacy groups, social media, and online health communities. Compounded on this, previous studies demonstrate heterogeneous practice patterns in the management of EoE, often differing from consensus guidelines.28,31,32 The current findings build upon on our prior work that patients with EoE value but do not experience SDM, a process that requires providers to have and deliver evidence-based knowledge, patients to clarify their preferences, and effective patient–provider communication, around decisions for treatment.16,17 Negative experiences with providers who lacked EoE-related knowledge and understanding of patient values dissuaded patients from using treatment, decreased confidence in their physician, and put the onus on patients to self-educate and in some cases, teach their doctor. This not only highlights the complex nature of adoption of a new disease and provider awareness, but also underscores the critical need for standardized provider-targeted education as a key foundation of quality care. If providers are to succeed in providing high-quality EoE care, they need to equip themselves with evidence-based knowledge, engage in collaboration that recognizes differences in provider and patient understandings of the disease and SDM, and look outside of the clinical setting to recognize barriers to disease management.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This is the first study to specifically examine EoE patient perspectives outside of a clinical or traditional research setting, but there are strengths and limitations to acknowledge. First, as this analysis was limited to online conversations threads among anonymous individuals, the diagnosis of EoE could not be confirmed. It is possible that some posts included users without EoE who attributed their symptoms to this disease or even automatically generated posts by bots or organizations. During the coding process, care was taken to discern posts focused on the topic of EoE from unrelated threads (e.g. about other atopic or gastrointestinal diseases) by authors with clinical and research expertise in EoE. Threads or spam posts by bots or organizations were screening out specifically by reading through all threads prior to coding and eliminating those that were irrelevant or misleading. Our search did not yield duplicate posts from the same individual, but by nature of the online discourse, multiple posts from and between individuals enhanced the forum discussions and were included. Second, although we included conversation threads from three online EoE communities across two years, the unique characteristics of the posters were unknown and we cannot assess diversity of age, sex, race, ethnicity, and geography among the individuals, or their provider types. Our findings are supported by achieving thematic saturation prior to coding all of the threads, however, it is possible that some patient perspectives were not represented. Third, as our data collection was restricted to open access online forums with specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, the analysis does not reflect posts from private patient groups or secure web communities. Our qualitative approach was designed to elicit new knowledge rather than describing statistical representation in this population. Although the use of existing social media posts reduces self-selection, recall, and researcher biases, there exist other potential biases of reliability and generalizability, particularly given the anonymity of the individuals. However, because anonymity is known to increase self-disclosure and a disinhibition effect, in which people self-disclose more online than in person, is commonly observed in online environments, we leveraged this anonymity to gain unique patient insights on EoE.33 To our knowledge, there are no studies comparing patient disclosure on social media versus in clinical settings, but recent work by Levy et al. demonstrated that 61%–81% of patients withhold medically relevant information from their clinicians, further supporting the value of social media listening to identify unmet needs and provide authentic insights that are otherwise undisclosed during traditional clinical encounters.34 Although there is a likelihood of dishonesty in any patient-reported forum or clinical setting, no evidence exists to suggest that individuals are more dishonest in anonymous online health communities.

Existing studies on patient-reported outcomes and experiences in EoE include surveys and interviews. These prior studies offer a curated glimpse of EoE patient experiences through the lens of participants recruited from specialized EoE-specific gastroenterology practices or EoE patient advocacy groups, thus are subject to selection and response biases. Survey findings may not be generalizable to a wider population of patients who are less engaged and are limited to responses crafted by researchers who may not themselves experience the disease; interview studies rely on those willing to share their opinions with researchers, many of whom are affiliated with medical centers. Although not specific to the EoE population, a large majority of patients withhold medical information from their physicians, suggesting that degrees of untruth exist within both filtered research and clinical settings. In contrast, we explored unbiased conversations on online health forums to gain unguarded and previously unheard patient perspectives. These unsolicited insights between patients offer different and perhaps more complete perspectives that patients may not freely express to their providers, and augment our understanding of how they view the disease and treatments. In particular, critical views of providers, nonadherence to treatment, and preference to defer treatment are examples of essential EoE patient voices previously unheard in existing studies, likely not disclosed during clinical encounters, and challenging to measure without significant bias. Insights from observational studies such as this allow us to examine if findings from studies to date and our clinical experiences translate into the public environment.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates the complex ways that EoE is experienced and managed from an unfiltered patient perspective on social media, highlighting the diversity of factors that influence the decision making and behaviors of patients who suffer from the disease. EoE patients interpret their disease as sporadic events and lack reliable sources of knowledge, which may influence how chronic treatment is prioritized and misjudged as nonadherence. Treatments are polarized as short-term fixes (medication) or personalized long-term commitments (diet), and patients’ definitions of success and their interaction with providers may impact decisions about treatment. These perspectives must be considered for effective treatment and long-term care as fundamental drivers of disease management. Finally, as EoE is an emerging diagnosis, these observations of how patients interpret their symptoms, struggle with treatments, and weigh preferences can be applied to other new diseases where uncertainty lies.

Supplementary Material

Guarantor of the article: Joy W. Chang.

Specific author contributions: Study concept and design: JWC; Data acquisition: JWC, VLC; Qualitative coding: JWC; Data interpretation: JWC, RD; Drafting of the manuscript: JWC; Study supervision: RD; Critical revision of the manuscript: JWC, JHR, ESD, LPW, RD.

Financial support: JWC is supported by a training grant from the Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR) (U54AI117804).

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Joy W Chang, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Vincent L Chen, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Joel H Rubenstein, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; Veterans Affairs Center for Clinical Management Research, Ann Arbor VA Medical Center, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Evan S Dellon, Division of Gastroenterology, Center for Esophageal and Swallowing Disorders, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Lauren P Wallner, Division of General Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Raymond De Vries, Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

References

- 1. Dellon E S, Hirano I. Epidemiology and natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(2): 319–332.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dellon E S, Jensen E T, Martin C F, Shaheen N J, Kappelman M D. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12(4): 589–596.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dellon E S, Gonsalves N, Hirano Iet al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(5): 679–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Furuta G T, Liacouras C A, Collins M Het al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 2007; 133(4): 1342–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liacouras C A, Furuta G T, Hirano Iet al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128(1): 3–20.e6quiz 21-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hirano I, Chan E S, Rank M Aet al. AGA Institute and the joint task force on allergy-immunology practice parameters clinical guidelines for the Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2020; 158(6): 1776–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dellon E S, Woosley J T, Arrington Aet al. Rapid recurrence of eosinophilic esophagitis activity after successful treatment in the observation phase of a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18(7): 1483–1492.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greuter T, Safroneeva E, Bussmann Cet al. Maintenance treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with swallowed topical steroids alters disease course over a 5-year follow-up period in adult patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17(3): 419–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mehta P, Pan Z, Furuta G T, Kwan B M. Mobile health tool detects adherence rates in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7(7): 2437–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang R, Hirano I, Doerfler B, Zalewski A, Gonsalves N, Taft T. Assessing adherence and barriers to long-term elimination diet therapy in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 2018; 63(7): 1756–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lucendo A J, Arias-Gonzalez L, Molina-Infante J, Arias A. Determinant factors of quality of life in adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. United European Gastroenterol J 2018; 6(1): 38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Safroneeva E, Coslovsky M, Kuehni C Eet al. Eosinophilic oesophagitis: relationship of quality of life with clinical, endoscopic and histological activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42(8): 1000–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schoepfer A M, Safroneeva E, Bussmann Cet al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology 2013; 145(6): 1230–1236.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warners M J, Oude Nijhuis R A B, Wijkerslooth L R H, Smout A, Bredenoord A J. The natural course of eosinophilic esophagitis and long-term consequences of undiagnosed disease in a large cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113(6): 836–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taft T H, Kern E, Keefer L, Burstein D, Hirano I. Qualitative assessment of patient-reported outcomes in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011; 45(9): 769–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chang J W, Rubenstein J H, Mellinger J Let al. Motivations, barriers, and outcomes of patient-reported shared decision making in eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 2021; 66(6): 1808–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hiremath G, Kodroff E, Strobel M Jet al. Individuals affected by eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders have complex unmet needs and frequently experience unique barriers to care. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2018; 42(5): 483–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Safroneeva E, Balsiger L, Hafner Det al. Adults with eosinophilic oesophagitis identify symptoms and quality of life as the most important outcomes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 48(10): 1082–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Solberg L B. The benefits of online health communities. Virtual Mentor 2014; 16(4): 270–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thanawala S U, Beveridge C, Muir A Bet al. Hashing out current social media use in eosinophilic_esophagitis. Dis Esophagus 2021; doab059. doi: 10.1093/dote/doab059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Castaneda P, Sales A, Osborne N H, Corriere M A. Scope, themes, and medical accuracy of eHealth peripheral artery disease community forums. Ann Vasc Surg 2019; 54: 92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marcon A R, Ravitsky V, Caulfield T. Discussing non-invasive prenatal testing on Reddit: the benefits, the concerns, and the comradery. Prenat Diagn 2021; 41(1): 100–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chang J W, Dellon E S. Challenges and opportunities in social media research in gastroenterology. Dig Dis Sci 2021In press; 66(7): 2194–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Malterud K, Siersma V D, Guassora A D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res 2016; 26(13): 1753–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. White K, Issac M S, Kamoun C, Leygues J, Cohn S. The THRIVE model: a framework and review of internal and external predictors of coping with chronic illness. Health Psychol Open 2018; 5(2): 2055102918793552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miller T L, Desai A D, Garrison M M, Lee D, Muir A, Lion K C. Drivers of variation in diagnosis and management of eosinophilic esophagitis: a survey of pediatric gastroenterologists. Dig Dis Sci 2021. 10.1007/s10620-021-07039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sharma A, Eluri S, Philpott H, Lemberg D A, Dellon E S. EoE down under is still EoE: variability in provider practice patterns in Australia and New Zealand among pediatric gastroenterologists. Dig Dis Sci 2021; 66(7): 2301–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chang J W, Saini S D, Mellinger J L, Chen J W, Zikmund-Fisher B J, Rubenstein J H. Management of eosinophilic esophagitis is often discordant with guidelines and not patient-centered: results of a survey of gastroenterologists. Dis Esophagus 2019; 32(6): doy133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schoepfer A M, Panczak R, Zwahlen Met al. How do gastroenterologists assess overall activity of eosinophilic esophagitis in adult patients? Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110(3): 402–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alexander R, Alexander J A, Ravi Ket al. Measurement of observed eating behaviors in patients with active and inactive eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17(11): 2371–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eluri S, Iglesia E G A, Massaro M, Peery A F, Shaheen N J, Dellon E S. Practice patterns and adherence to clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management of eosinophilic esophagitis among gastroenterologists. Dis Esophagus 2020; 33(7): doaa025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McClain A, O'Gorman M, Barbagelata Cet al. Adherence to biopsy and follow-up guidelines in a population-based cohort of children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18(11): 2620–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Suler J. The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol Behav 2004; 7(3): 321–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Levy A G, Scherer A M, Zikmund-Fisher B J, Larkin K, Barnes G D, Fagerlin A. Prevalence of and factors associated with patient nondisclosure of medically relevant information to clinicians. JAMA Netw Open 2018; 1(7): e185293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.