Abstract

Background

The characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 Omicron variant have not been fully described. Unlike other variants, the Omicron variant replicates rapidly in the bronchus. Therefore, we hypothesized that it would have different computed tomography (CT) findings from non-Omicron variants.

Methods

We enrolled patients with COVID-19 who visited our hospital and underwent chest CT during the first month of the Omicron wave (January 2022; N = 231) and the previous non-Omicron wave (July 2021; N = 87). We retrospectively evaluated the differences in the prevalence rate and CT characteristics of COVID-19 pneumonia between the two waves.

Results

The prevalence of pneumonia was significantly lower in the Omicron wave group (79/231, 34.2%) compared to the previous wave group (67/87, 77.0%) (P < 0.001). For the predominant distribution pattern of pneumonia, the Omicron wave group revealed a significantly lower rate of the peripheral pattern and a higher rate of the random pattern than the previous wave group. In addition, the Omicron wave group had a significantly lower rate of consolidation than the previous wave group. The ground-glass opacities (GGOs) rate was similar between the two wave groups. For GGOs patterns, cluster-like GGOs along the bronchi on chest CT were more frequently observed during the Omicron wave than during the previous wave.

Conclusion

The Omicron wave group had a lower COVID-19 pneumonia prevalence than the previous wave group. Cluster-like GGOs should be noted as a characteristic CT finding of pneumonia during the Omicron wave.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, Pneumonia, Omicron variant, Computed tomography, Cluster-like ground-glass opacities

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CT, computed tomography; GGOs, ground-glass opacities; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

1. Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Omicron variant was first reported in South Africa on November 24, 2021 [1]. The Omicron variant spread rapidly worldwide and replaced other variants of SARS-CoV-2. A previous report showed that the Omicron variant was less likely to cause severe disease than other variants [2]. The Omicron variant is considered less likely to cause pneumonia due to its low replication competence in the lung parenchyma [3]. However, we do not have precise data on whether the prevalence rate of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia during the Omicron wave is lower than that during the previous wave.

COVID-19 pneumonia typically presents with subpleural ground-glass opacities (GGOs), consolidation, and a crazy paving pattern [4]. We speculated that these shadows of COVID-19 pneumonia are seen in subpleural lung lesions because SARS-CoV-2 replicates in the alveolar epithelium [5]. One of the distinct characteristics of the Omicron variant that distinguishes it from previous variants, such as Alpha and Delta, is its rapid replication in the bronchial epithelium cells [3]. Based on this fact, COVID-19 caused by the Omicron variant can cause inflammation not only in lung parenchyma but also along the bronchi, which results in bronchial pneumonia.

Influenza pneumonia shows a cluster-like pattern along the bronchi [6]. Conventional COVID-19 (pre-Omicron) pneumonia without high replication competence in the bronchi is reported to rarely exhibit these cluster-like GGOs [6]. However, we hypothesized that COVID-19 pneumonia caused by the Omicron variant shows cluster-like GGOs more frequently than that caused by the previous variants.

Therefore, this study aimed to clarify the differences in the prevalence rate and CT characteristics of COVID-19 pneumonia between the Omicron variant and the previous non-Omicron (Alpha and Delta variants) waves.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study population

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hiroshima City Funairi Citizens Hospital (approval number 2021018, and the date of approval was March 10, 2022). Informed consent was obtained from the included patients via the opt-out method.

In this study, 235 and 88 patients with COVID-19 visited our hospital during the first month of the Omicron wave (January 1–31, 2022) and the previous non-Omicron (Alpha and Delta variants) wave (July 1–31, 2021), respectively. A total of 308 patients (Omicron wave, 220 patients; non-Omicron wave, 88 patients) were diagnosed with COVID-19 by a positive polymerase chain reaction test; however, 15 patients were diagnosed by qualitative antigen test alone during the Omicron wave.

For all the patients included in this study, visiting the hospital was considered desirable by the COVID-19 Coordination Office, Hiroshima Prefectural Government, based on their symptoms, such as high fever, cough, dyspnea, fatigue, and/or hypoxemia.

Since COVID-19 pneumonia was suspected from their symptoms and desaturation, a CT examination was essentially performed with patients’ consent to assess COVID-19 pneumonia and determine the appropriate treatment accordingly.

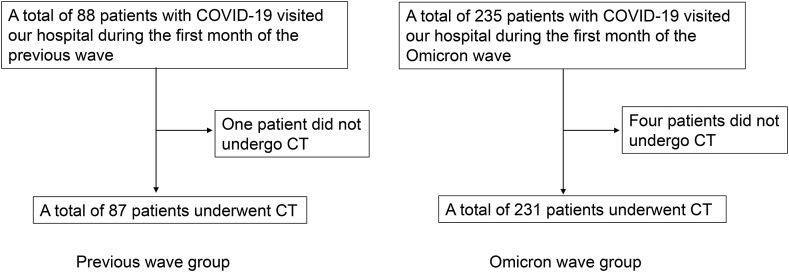

Of these patients, 231 in the Omicron wave group and 87 in the previous wave group underwent chest CT (Fig. 1 ). Data on age, sex, smoking habit, comorbidities, days from onset to hospital visit, COVID-19 vaccination status, percutaneous arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) at the time of the first visit to our hospital, and presence of COVID-19 pneumonia based on chest CT images were collected from electronic medical records and compared between the two groups.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient enrollment. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CT, computed tomography.

2.2. Evaluation of COVID-19 pneumonia on CT images

In cases where COVID-19 pneumonia was diagnosed by the attending physician, another three pulmonologists separately evaluated predominant distribution and morphologic patterns without clinical information. In patients with a split decision among the three pulmonologists, the majority opinion was adopted as the final decision.

Predominant distribution and morphologic patterns were decided according to the following rules. First, the lung peripheries were defined as the outer one-third of the lung, while the remaining was considered the central area [7]. The predominant distribution pattern of the lesions was classified as follows: peripheral (mainly peripheral lesions), central (mainly central lesions), diffuse (continuous lesions from subpleural to central), or random (without predilection for peripheral and central lesions) [6].

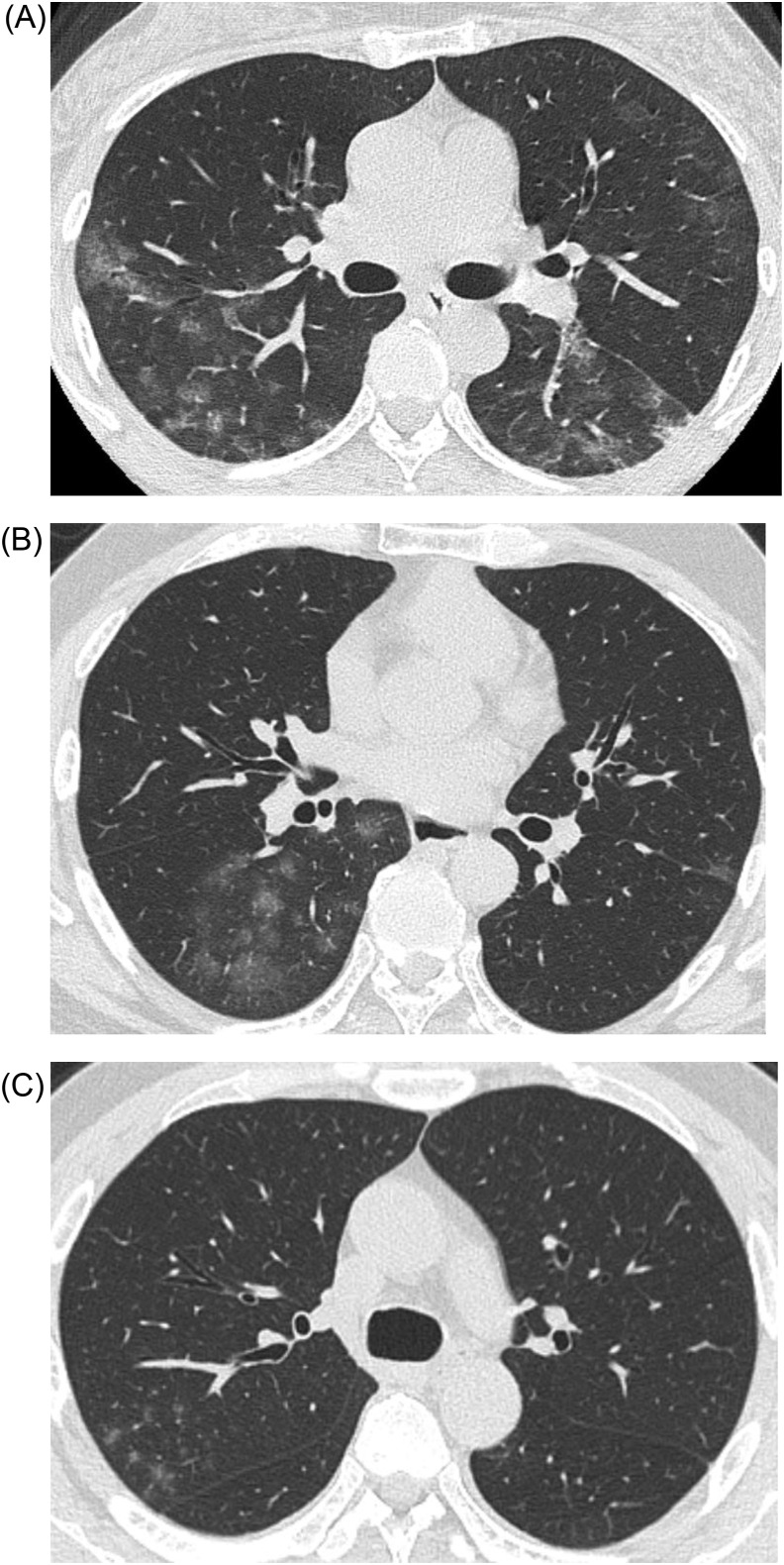

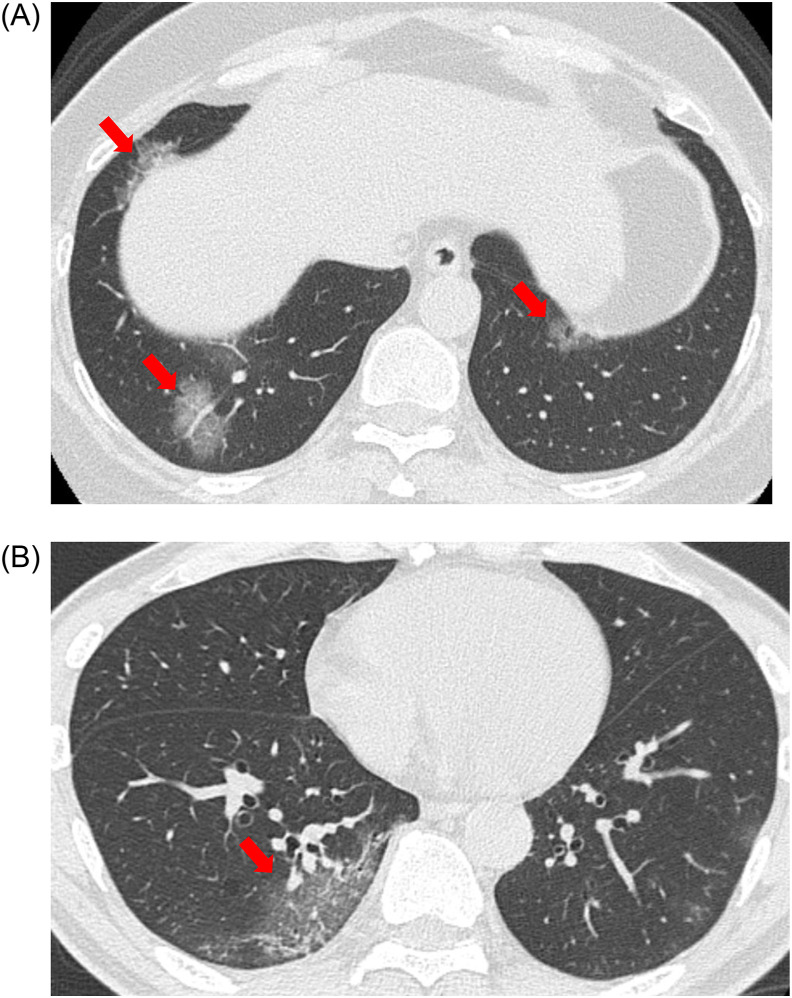

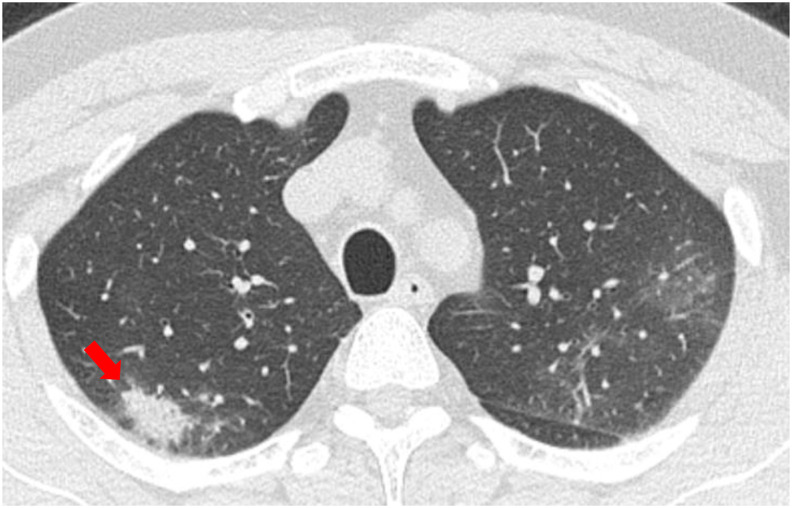

The representative morphologic patterns of COVID-19 pneumonia on CT are shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5 . In this study, we classified the morphologic patterns of COVID-19 pneumonia according to the following three technical terms: GGOs (Fig. 2, Fig. 3), consolidations (Fig. 4), and crazy paving patterns (lesions characterized by thickened interlobular septa overlapping with ground-glass shadows) (Fig. 5). The GGOs involvement pattern was classified as cluster-like (Fig. 2A–C) or patchy (Fig. 3A and B) in reference to a study conducted by Wang H et al. [6]. We defined cluster-like GGOs as multiple GGOs along the bronchi and patchy GGOs as subpleural GGOs.

Fig. 2.

Representative computed tomography (CT) images of cluster-like ground-glass opacities (GGOs). (A) CT image of a 52-year-old woman who presented to our hospital on the eighth day after onset (Omicron wave). Cluster-like GGOs were noted in the right upper and left lower lobes. (B) CT image of a 51-year-old man who presented to our hospital on the eighth day after onset (Omicron wave). Cluster-like GGOs were noted in the right lower lobe. (C) CT image of a 44-year-old man who presented to our hospital on the tenth day after onset (Omicron wave). Cluster-like GGOs were noted in the right upper lobe.

Fig. 3.

Representative computed tomography (CT) images of patchy ground-glass opacities (GGOs). (A) CT image of a 55-year-old woman who presented to our hospital on the tenth day after onset (Omicron wave). Patchy GGOs (red arrows) were noted in both the lower lobes. (B) CT image of a 62-year-old man who presented to our hospital on the fifth day after onset (Previous wave). Patchy GGO (red arrow) was noted in the right lower lobe. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 4.

Representative computed tomography (CT) image of consolidation. CT image of a 49-year-old man who presented to our hospital on the sixth day after onset (Previous wave). Consolidation (red arrow) with subpleural distribution was noted in the right upper lobe.

Fig. 5.

Representative computed tomography (CT) image showing a crazy-paving pattern. CT image of a 54-year-old woman who presented to our hospital on the ninth day after onset (Omicron wave). A crazy-paving pattern with subpleural distribution was noted in the right upper lobe.

2.3. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the median (range). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the variables between the two groups. Fisher's exact test was performed for categorical variables. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 16.0.0® (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of patient demographics and prevalence of COVID-19 pneumonia between the two wave groups

Patient demographics in the two wave groups are shown in Table 1 . The prevalence of COVID-19 pneumonia was significantly lower in the Omicron wave group (79/231, 34.2%) than in the previous wave group (67/87, 77.0%) (P < 0.001). The Omicron wave group had a significantly lower proportion of male patients and higher rates of hypertension and chronic lung disease as comorbidity. The vaccination rate was higher in the Omicron wave group than in the previous wave group (P < 0.001). Although the median ages were not significantly different between the two wave groups, the number of patients aged ≥65 years was higher in the Omicron wave group.

Table 1.

Comparison of patients with COVID-19 during the Omicron wave (January 2022) and the previous wave (July 2021).

| Previous wave (N = 87) | Omicron wave (N = 231) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 41 (18–84) | 44 (15–99) | 0.124 |

| Age ≥65 years | 6 (6.9%) | 49 (21.2%) | 0.002 |

| Male, n (%) | 58 (66.7%) | 116 (50.2%) | 0.011 |

| Smoking habit | 37 (42.5%) | 76 (32.9%) | 0.117 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Diabetes | 6 (6.9%) | 20 (8.7%) | 0.819 |

| Hypertension | 5 (5.7%) | 49 (21.2%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 1 (1.1%) | 25 (10.8%) | 0.003 |

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) | 8 (9.2%) | 26 (11.3%) | 0.687 |

| Days from onset to hospital visit, median (range) | 5 (1–9) | 4 (1–17) | 0.162 |

| Vaccination, n (%) | 3 (3.4%) | 151 (65.4%) | <0.001 |

| The prevalence of pneumonia in COVID-19 patients | 77.0% (67/87) | 34.2% (79/231) | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

At the first visit, 17 of the 231 patients in the Omicron wave group (median age, 87 years [35–98 years]) presented with hypoxemia defined as SpO2 <93%, 10 with COVID-19 pneumonia, and 7 without COVID-19 pneumonia.

On the contrary, all the patients in the previous wave group did not experience hypoxemia with SpO2 <93%, regardless of the presence or absence of COVID-19 pneumonia.

Subsequently, patients in each group were divided into two groups according to the presence (pneumonia positive [+] group) or absence (pneumonia negative [−] group) of COVID-19 pneumonia (Table 2 ). An intra-group comparison was then performed as a subgroup analysis.

Table 2.

Comparison of patients with and without COVID-19 pneumonia during the Omicron wave (January 2022) and the previous wave (July 2021).

| Previous wave (N = 87) | Omicron wave (N = 231) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia (+) N = 67 | Pneumonia (−) N = 20 | P-value | Pneumonia (+) N = 79 | Pneumonia (−) N = 152 | P-value | |

| Age (years), median (range) | 43 (18–70) | 35.5 (18–84) | 0.661 | 51 (19–98) | 40 (15–99) | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 45 (67.2%) | 13 (65.0%) | >0.99 | 50 (63.3%) | 66 (43.4%) | 0.005 |

| Smoking habit | 26 (38.8%) | 11 (55.0%) | 0.211 | 31 (39.2%) | 45 (29.6%) | 0.139 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Diabetes | 5 (7.5%) | 1 (5.0%) | >0.99 | 11 (13.9%) | 9 (5.9%) | 0.0495 |

| Hypertension | 3 (4.5%) | 2 (10.0%) | 0.324 | 22 (27.9%) | 27 (17.8%) | 0.090 |

| Chronic lung disease | 1 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.99 | 7 (8.9%) | 18 (11.8%) | 0.656 |

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) | 7 (10.5%) | 1 (5.0%) | 0.676 | 13 (16.5%) | 13 (8.6%) | 0.082 |

| Days from onset to hospital visit, median (range) | 5 (1–9) | 3 (1–9) | <0.001 | 5 (1–11) | 3 (1–17) | <0.001 |

| Vaccination, n (%) | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (10.0%) | 0.131 | 47 (59.5%) | 104 (68.4%) | 0.192 |

BMI, body mass index.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

In the Omicron wave group, patients in the pneumonia (+) group were older and more likely to be male and had higher rates of diabetes as comorbidity compared to the pneumonia (−) group; however, in the previous wave group, the difference in these indices between the pneumonia (+) and pneumonia (−) groups did not reach statistical significance. The number of days from onset to hospital visit was longer in the pneumonia (+) group than in the pneumonia (−) group in both the waves. The vaccination rate in the pneumonia (+) group was only 1.5% in the previous wave group, whereas it was 59.5% in the Omicron wave group.

3.2. Comparison of predominant distribution and morphologic patterns between the two wave groups

The CT characteristics were compared in 79 and 67 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in the Omicron wave and previous wave groups, respectively (Table 3 ). As for the predominant distribution pattern, the Omicron wave group exhibited a significantly lower peripheral pattern incidence and higher random pattern incidence than the previous wave group. The morphologic pattern showed that the previous wave group exhibited a significantly higher consolidation incidence than the Omicron wave group. Although the incidence of the GGOs and patchy GGOs were similar between the two wave groups, cluster-like GGOs were observed significantly more often in the Omicron wave group than in the previous wave group.

Table 3.

Comparison of imaging features of COVID-19 pneumonia during the Omicron wave (January 2022) and the previous wave (July 2021).

| COVID-19 pneumonia cases in Previous wave (N = 67) No. (%) |

COVID-19 pneumonia cases in Omicron wave (N = 79) No. (%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion distribution | |||

| Peripheral | 49 (73.1%) | 37 (46.8%) | 0.001 |

| Central | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (2.5%) | >0.99 |

| Diffuse | 5 (7.5%) | 3 (3.8%) | 0.470 |

| Random | 12 (17.9%) | 37 (46.8%) | <0.001 |

| CT findings | |||

| GGOs | 60 (89.6%) | 76 (96.2%) | 0.187 |

| Consolidation | 44 (65.7%) | 38 (48.1%) | 0.044 |

| Crazy-paving pattern | 17 (25.4%) | 12 (15.2%) | 0.147 |

| GGOs involvement pattern | |||

| Patchy | 47 (70.1%) | 48 (60.8%) | 0.296 |

| Cluster-like | 14 (20.9%) | 36 (45.6%) | 0.003 |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

CT, computed tomography.

GGOs, ground-glass opacities.

3.3. Relationship between hypoxemia, and predominant distribution and morphologic patterns of COVID-19 pneumonia during the Omicron wave

Patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in the Omicron wave group were divided into hypoxemia (+) and hypoxemia (−), and CT characteristics were compared between the groups (Table 4 ). The predominant distribution pattern showed that the hypoxemia (+) group exhibited a significantly higher incidence of diffuse patterns than the hypoxemia (−) group. However, the number was small in both the groups. There were no significant differences between the two groups for other imaging features.

Table 4.

Comparison of imaging features of COVID-19 pneumonia between hypoxemia (+) and hypoxemia (−) patients during the Omicron wave.

| COVID-19 pneumonia cases during the Omicron wave (N = 79) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxemia (−) (N = 69) No. (%) |

Hypoxemia (+) (N = 10) No. (%) |

P-value | |

| Lesion distribution | |||

| Peripheral | 34 (49.3%) | 3 (30.0%) | 0.322 |

| Central | 2 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | >0.99 |

| Diffuse | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0.041 |

| Random | 32 (46.4%) | 5 (50.0%) | >0.99 |

| CT findings | |||

| GGOs | 66 (95.7%) | 10 (100%) | >0.99 |

| Consolidation | 34 (49.3%) | 4 (40%) | 0.739 |

| Crazy-paving pattern | 12 (17.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.345 |

| GGOs involvement pattern | |||

| Patchy | 41 (59.4%) | 7 (70.0%) | 0.732 |

| Cluster-like | 31 (44.9%) | 5 (50.0%) | >0.99 |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

CT, computed tomography.

GGOs, ground-glass opacities.

4. Discussion

In Japan, the prevalence rate of COVID-19 pneumonia has been reported to be 86.6% as of July 2020, before the appearance of the SARS-CoV-2 variant [8]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the prevalence rate of COVID-19 pneumonia in Japanese patients after the SARS-CoV-2 variant appeared. Although about 80% of patients with COVID-19 developed pneumonia as a complication during the Alpha and Delta variants wave, only 34% of these patients developed COVID-19 pneumonia during the Omicron wave, which was similar to the result of the study conducted in South Africa (37%) [9]. We speculated two possible reasons for the lower COVID-19 pneumonia prevalence rate in the Omicron wave; the Omicron variant causes less damage to the lung parenchyma than the previous variants, and many people had been vaccinated before the Omicron variant appeared.

The period between onset and presentation to our hospital was 2 days longer in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia than in patients without COVID-19 pneumonia in both waves. Thus, it may be desirable to introduce treatment as soon as symptoms appear, regardless of the variant. Regarding age, patients with COVID-19 pneumonia during the Omicron wave tended to be significantly older than those without COVID-19 pneumonia. Based on this result, we speculated that COVID-19 pneumonia tends to occur in much older patients in the Omicron variant cases compared to the previous variant cases.

Among the vaccinated patients, those who developed COVID-19 pneumonia were more in the Omicron wave group than those in the previous wave group. However, we could not simply compare the two groups due to differences in the timing of vaccination and the number of vaccinated patients. In Japan, far more people had received two doses of vaccine before the Omicron variant appeared than before the Alpha and Delta variants appeared [10]. Older people received two doses of vaccine earlier than all the other generations; however, most missed the third dose of vaccine before the Omicron variant hit [10]. Thus, the efficacy of the vaccination, i.e., the degree of neutralizing antibody titers, decreased over time in older people. This may be why older patients were likely to develop COVID-19 pneumonia during the Omicron wave.

Although there was no significant difference in the median ages between the two wave groups, a greater number of infected older patients were in the Omicron wave group. Additionally, the Omicron wave group included patients with hypoxemia at the first visit, most of whom were older. From these two findings, we can conclude that some older infected patients developed hypoxemia.

In Hiroshima City, the number of patients with COVID-19 was reported to be 301 in July 2021 and 15,881 in January 2022 [11]. In the early stage of the previous wave (July 2021), the provision of health care was relatively sufficient, which allowed most patients to visit a hospital before developing hypoxemia. This may be the reason that no patients in the previous wave group had hypoxemia at the first visit. Furthermore, the higher rate of patients with hypoxemia in the Omicron wave group compared to that in the previous wave group may have affected the prevalence of pneumonia in this study.

The second notable finding in this study was the remarkable differences in the predominant distribution and morphologic patterns of COVID-19 pneumonia between the two wave groups. Randomly distributed lesions and cluster-like GGOs were more frequently observed in the Omicron wave group, while peripheral distributed lesions and patchy GGOs were more frequently observed in the previous wave group. The exact mechanism is unknown; however, the following has been hypothesized: the primary target cells of SARS-CoV-2 are reportedly alveolar type II epithelial cells [12,13]. Previous non-Omicron variants may likely form patchy GGOs through infection with a predilection for the peripheral area of the lung, where alveoli are more abundant than in the central area.

In contrast, compared to other variants, the Omicron variant is more likely to grow in the bronchial epithelial cells and less likely to grow in the lung parenchyma [3]. These features in the growth of the Omicron variant can cause bronchial inflammation through the proximal to distal sites with alveolar inflammation around these bronchi, which leads to bronchial pneumonia and form the characteristic CT images of cluster-like GGOs. We speculated that because of the less familiarity of the Omicron variant to the lung parenchyma than other variants [3], each cluster-like GGO does not tend to fuse and spread widely. From this point of view, we must pay attention to the appearance of new SARS-CoV-2 variants in the future, which can rapidly replicate in both the bronchial and lung alveolar cells, leading to severe pneumonia and high death rates.

This study had several limitations. First, this retrospective study was only conducted in a single facility; therefore, the sample size was small. Thus, further investigation, including more patients, is needed. Second, we divided the patients into two wave groups according to the duration of each wave. For example, since a genome analysis report from Hiroshima Prefecture showed that the Omicron variant was detected in 98% of the screening tests performed in January 2022 [14], we presumed that patients with COVID-19 who visited our hospital during January 2022 were infected with the Omicron variant. However, as we could not precisely confirm the type of variant using real-time polymerase chain reaction, patients with COVID-19 infected with the Alpha or Delta variants could have been included in the Omicron wave group. Third, there were significant differences in comorbidities and vaccination rates between the two wave groups. These could affect the CT findings.

5. Conclusion

Among patients with COVID-19, those infected during the Omicron wave had a lower prevalence rate of pneumonia than those infected during the previous wave. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that the Omicron variant was likelier to exhibit cluster-like GGOs along the bronchi than the Alpha or Delta variants. Therefore, clinicians should take heed of changes in the CT characteristics during the Omicron wave.

Funding

This research was funded by “Advanced study aim to contribute creating new evidence in COVID-19 based on the local government-academia collaboration research system in Hiroshima”: AMED Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases, Grant Number JP20fk0108453.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

References

- 1.Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern

- 2.Wolter N., Jassat W., Walaza S., Welch R., Moultrie H., Groome M., et al. Early assessment of the clinical severity of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in South Africa: a data linkage study. Lancet. 2022;399:437–446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00017-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hui K.P.Y., Ho J.C.W., Cheung M.C., Ng K.C., Ching R.H.H., Lai K.L., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant replication in human bronchus and lung ex vivo. Nature. 2022;603:715–720. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Churruca M., Martínez-Besteiro E., Couñago F., Landete P. COVID-19 pneumonia: a review of typical radiological characteristics. World J Radiol. 2021;13:327–343. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v13.i10.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Y., Wang L., Ben S. Meta-analysis of chest CT features of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2021;93:241–249. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H., Wei R., Rao G., Zhu J., Song B. Characteristic CT findings distinguishing 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) from influenza pneumonia. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:4910–4917. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06880-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song F., Shi N., Shan F., Zhang Z., Shen J., Lu H., et al. Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295:210–217. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsunaga N., Hayakawa K., Terada M., Ohtsu H., Asai Y., Tsuzuki S., et al. Clinical epidemiology of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Japan: report of the COVID-19 Registry Japan. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e3677–e3689. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdullah F., Myers J., Basu D., Tintinger G., Ueckermann V., Mathebula M., et al. Decreased severity of disease during the first global omicron variant covid-19 outbreak in a large hospital in tshwane, South Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;116:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.12.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health and Welfare 2022. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000922123.pdf

- 11.Hiroshima city homepage. https://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/site/korona/276823.html

- 12.Delorey T.M., Ziegler C.G.K., Heimberg G., Normand R., Yang Y., Segerstolpe Å., et al. COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets. Nature. 2021;595:107–113. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bridges J.P., Vladar E.K., Huang H., Mason R.J. Respiratory epithelial cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19. Thorax. 2022;77:203–209. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiroshima prefectural government homepage. https://www.pref.hiroshima.lg.jp/site/hcdc/henikabu.html