Abstract

Bacillus subtilis contains three metalloregulatory proteins belonging to the ferric uptake repressor (Fur) family: Fur, Zur, and PerR. We have overproduced and purified Fur protein and analyzed its interaction with the operator region controlling the expression of the dihydroxybenzoate siderophore biosynthesis (dhb) operon. The purified protein binds with high affinity and selectivity to the dhb regulatory region. DNA binding does not require added iron, nor is binding reduced by dialysis of Fur against EDTA or treatment with Chelex. Fur selectively inhibits transcription from the dhb promoter by ςA RNA polymerase, even if Fur is added after RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Since neither DNA binding nor inhibition of transcription requires the addition of ferrous ion in vitro, the mechanism by which iron regulates Fur function in vivo is not obvious. Mutagenesis of the fur gene reveals that in vivo repression of the dhb operon by iron requires His97, a residue thought to be involved in iron sensing in other Fur homologs. Moreover, we identify His96 as a second likely iron ligand, since a His96Ala mutant mediates repression at 50 μM but not at 5 μM iron. Our data lead us to suggest that Fur is able to bind DNA independently of bound iron and that the in vivo role of iron is to counteract the effect of an inhibitory factor, perhaps another metal ion, that antagonizes this DNA-binding activity.

Iron is an essential and often growth-limiting nutrient for microorganisms. The rapid oxidation of ferrous to ferric iron, which is virtually insoluble at a nearly neutral pH, reduces the level of bioavailable iron far below the approximately 1 μM that most organisms require for optimal growth (4, 18, 28, 29). Consequently, many bacteria synthesize and excrete high-affinity iron chelators (siderophores) that can solubilize ferric iron and subsequently be imported by a corresponding ferri-siderophore uptake system (29). The expression of genes for siderophore biosynthesis and transport is repressed by added iron. In many bacteria, this repression is mediated by a metal-sensing DNA-binding protein, the ferric uptake repressor (Fur) protein (22, 23).

Fur has been best characterized from Escherichia coli (designated FurEC), but homologs have been identified in numerous other bacteria (22, 23). In vivo, FurEC represses a large regulon of iron uptake functions when iron is present in excess (6). Most other metals are ineffective at eliciting repression in vivo, although Mn(II) leads to the repression of some, but not all, Fur-regulated genes (3, 5, 21, 32). In many gram-negative bacteria, selection for manganese-resistant (Mnr) mutants leads to mutations in fur, suggesting that the ability of Mn(II) to activate Fur for DNA binding may be a source of manganese toxicity, perhaps by inappropriately repressing iron uptake functions (21).

FurEC is an ∼16-kDa dimeric protein with an amino-terminal DNA recognition domain and a carboxyl-terminal metal-binding domain (12, 37). In vitro studies have demonstrated that FurEC binds to a specific DNA target site, the fur box, and that this binding requires a divalent metal ion as a cofactor (3, 14). In the vast majority of studies, Mn(II) is used to activate Fur, since this ion, unlike Fe(II), is stable in the presence of oxygen. It is generally assumed that Mn(II)-Fur is functionally analogous to the Fe(II) form thought to mediate repression in vivo. However, the metal-binding sites of Fur are not yet well characterized. Fur binds two divalent ions per monomer, and binding is thought to involve a cluster of conserved histidine residues and two pairs of cysteines in the carboxyl-terminal metal-binding domain (12, 24). One site is apparently occupied by a tightly associated (structural) zinc ion, while the second site is thought to bind Fe(II) reversibly to regulate DNA binding (24).

Bacillus subtilis contains three Fur homologs (8, 17) that regulate a peroxide stress response (PerR), zinc uptake (Zur), and iron uptake (Fur). Fur regulates the expression of several operons implicated in iron transport (8, 23), including the dihydroxybenzoate siderophore biosynthesis (dhb) operon. Transcription of the dhb operon is initiated from a single ςA-dependent promoter with an overlapping consensus fur box (33). Mutations in this fur box or in fur prevent the iron-mediated repression of dhb (8, 33). However, unlike its homologs from gram-negative organisms, B. subtilis Fur does not recognize Mn(II) as a corepressor in vivo, and selection for Mnr does not generate fur mutants (8, 9).

We have overproduced and purified B. subtilis Fur and initiated a study of its interactions with both DNA and metal ions. Surprisingly, Fur is purified in an active zinc-containing form that does not require the addition of Fe(II) to bind DNA or to repress transcription. Nevertheless, genetic studies are consistent with a model in which iron does interact directly with Fur in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotide primers.

The strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli DH5α was used for routine cloning experiments, while RK4353 (RecA+) was used to generate multimeric plasmids for efficient Campbell integration into the B. subtilis genome. To overproduce Fur, the gene was amplified by PCR with primers 75 and 76. These primers introduce NdeI and KpnI sites on the PCR product ends; these sites are then used for cloning into NdeI-KpnI-cut pET17b (Novagen), generating pHB6505. The synthetic oligonucleotide primers used were obtained from the DNA Services Facility of the Cornell New York State Center for Advanced Technology-Biotechnology.

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| B. subtilis | ||

| ZB307A | W168 SPβc2Δ2::Tn917::pSK10Δ6 | 42 |

| MO1099 | amyE::erm pheA1 trpC2 | 19 |

| HB1000 | ZB307A attSPβ | 9 |

| HB6543 | HB1000 fur::kan | 8 |

| HB6634 | HB1000 amyE::erm | This work |

| HB6637 | HB6543 amyE::erm | This work |

| HB6640 | HB6637 amyE::fur | This work |

| HB6650 | HB6634 amyE::fur H93A | This work |

| HB6651 | HB6634 amyE::fur H97A | This work |

| HB6652 | HB6634 amyE::fur H132A | This work |

| HB6653 | HB6634 amyE::fur C100A | This work |

| HB6654 | HB6634 amyE::fur C103A | This work |

| HB6655 | HB6634 amyE::fur C140A | This work |

| HB6656 | HB6634 amyE::fur C143A | This work |

| HB6657 | HB6637 amyE::fur H93A | This work |

| HB6658 | HB6637 amyE::fur H97A | This work |

| HB6659 | HB6637 amyE::fur H132A | This work |

| HB6660 | HB6637 amyE::fur C100A | This work |

| HB6661 | HB6637 amyE::fur C103A | This work |

| HB6662 | HB6637 amyE::fur C140A | This work |

| HB6663 | HB6637 amyE::fur C143A | This work |

| HB6668 | HB6634 amyE::fur H95A | This work |

| HB6670 | HB6634 amyE::fur H96A | This work |

| HB6672 | HB6637 amyE::fur H96A | This work |

| HB6673 | HB6637 amyE::fur H95A | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | φ80 Δ(lacZ)M15 Δ(argF-lac)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1 | 34 |

| RK4353 | araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 flhD5301 gyrA219 non-9 rpsL150 ptsF25 relA1 deoC1 | V. J. Stewart |

| BL21(DE3)/pLysE | F−ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm(DE3)/pLysE | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBKSII+ | pBR322 replicon | Stratagene |

| pDG1662 | Ectopic integration vector | 19 |

| pET17b | Overexpression vector | Novagen |

| pGEM-cat | pGEM-3zf(+)-cat-1 | 41 |

| pJM114 | pBS (Stratagene) with kan gene | 31 |

| pJPM122 | cat-lacZ operon fusion vector for phage SPβ | 36 |

| pHB6502 | pGEM-cat with 3.3-kb XbaI-SphI fragment including fur | 8 |

| pHB6504 | pHB6502 with the 0.4-kb BsiWI-NsiI fragment replaced by the 1.4-kb Acc65I-PstI kan gene from pJM114 | 8 |

| pHB6505 | pET17b with the 0.47-kb NdeI-KpnI fragment encoding fur (primers 75 and 76) | This work |

| pHB6524 | pGEM-cat with the fur gene (primers 140 and 139) | This work |

| pHB6525 | pDG1662 with the fur gene | This work |

| pHB6527 | pGEM-cat with the fur H93A gene | This work |

| pHB6528 | pGEM-cat with the fur H97A gene | This work |

| pHB6529 | pGEM-cat with the fur H132A gene | This work |

| pHB6530 | pGEM-cat with the fur C100A gene | This work |

| pHB6531 | pGEM-cat with the fur C103A gene | This work |

| pHB6532 | pGEM-cat with the fur C140A gene | This work |

| pHB6533 | pGEM-cat with the fur C143A gene | This work |

| pHB6534 | pGEM-cat with the fur H95A gene | This work |

| pHB6537 | pGEM-cat with the fur H96A gene | This work |

| pHB6538 | pDG1662 with the fur H93A gene | This work |

| pHB6539 | pDG1662 with the fur H97A gene | This work |

| pHB6540 | pDG1662 with the fur H132A gene | This work |

| pHB6541 | pDG1662 with the fur C100A gene | This work |

| pHB6542 | pDG1662 with the fur C103A gene | This work |

| pHB6543 | pDG1662 with the fur C140A gene | This work |

| pHB6544 | pDG1662 with the fur C143A gene | This work |

| pHB6545 | pDG1662 with the fur H95A gene | This work |

| pHB6547 | pDG1662 with the fur H96A gene | This work |

| pHB6548 | pJPM122 with the 0.4-kb HindIII-BamHI fragment encoding dhbA | This work |

| Primersb | ||

| 75 (forward) | 5′-GAGGGAAACATATGGAAAACCG-3′ | This work |

| 76 (reverse) | 5′-TGAGAAAAGGTACCCGCTCG-3′ | This work |

| 139 (reverse) | 5′-CATACTCTGGATCCACCCATATC-3′ | This work |

| 140 (forward) | 5′-TTAATGGAAAAGCTTACATCTAGAC-3′ | This work |

| 147 (H93A) | 5′-GGCGCAGCTGCCTTTCATCAC-3′ | This work |

| 148 (H95A) | 5′-GCTCACTTTGCTCACCACTTG-3′ | This work |

| 149 (H96A) | 5′-CACTTTCATGCCCACTTGGTG-3′ | This work |

| 150 (H97A) | 5′-TTTCATCACGCCTTGGTGTGC-3′ | This work |

| 151 (H132A) | 5′-ATTAAAGATGCTAGATTGACG-3′ | This work |

| 152 (C100A) | 5′-CACTTGGTGGCCATGGAGTGC-3′ | This work |

| 153 (C103A) | 5′-TGCATGGAGGCCGGAGCCGTTG-3′ | This work |

| 154 (C140A) | 5′-TTCACGGCATTGCGCACCGCTGTAACG-3′ | This work |

| 155 (C143A) | 5′-TGCCACCGCGCTAACGGAAAAG-3′ | This work |

| 200 (forward) | 5′-GCGTTTTAAGCTTCACCCTGA-3′ | This work |

| 201 (reverse) | 5′-GCTTTGAGGATCCTCACAACC-3′ | This work |

Amino acid changes are shown as, e.g., H93A.

Restriction enzyme cloning sites and relevant mutagenized nucleotides are underlined.

Reagents, media, and growth conditions.

Chemicals and antibiotics were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.) unless otherwise indicated. CuSO4 (99.999%), FeSO4 (99.999%), FeCl3 (at least 99.99%), MnCl2 (99.999%), NiSO4 (99.999%), and ZnSO4 (99.999%) were obtained from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, Wis.). Radioactive isotopes were purchased from DuPont, NEN Research Products (Boston, Mass.). Manganese- and iron-limited minimal media (MM) were prepared as previously described (7). Ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was used for the selection of E. coli strains. Erythromycin (1 μg/ml) and lincomycin (25 μg/ml) (for testing macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance), kanamycin (10 μg/ml), spectinomycin (100 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml) were used for the selection of B. subtilis strains.

DNA manipulations and sequencing.

Routine molecular biology procedures and DNA manipulations were carried out as described previously (34). B. subtilis transformation was done by standard procedures (13). E. coli plasmid DNA and DNA fragments were isolated with QIAprep Spin Miniprep and PCR purification and gel extraction kits, respectively (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). Restriction endonucleases, DNA ligase, Vent DNA polymerase, T4 polynucleotide kinase, and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), Sequenase (Amersham Life Science Inc.), Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and RNasin RNase inhibitor (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.) were used according to manufacturers’ instructions. DNA sequencing was performed on both strands for new constructs with AmpliTaq-FS DNA polymerase and dye terminator chemistry at the DNA Services Facility of the Cornell New York State Center for Advanced Technology-Biotechnology.

Overproduction and purification of Fur.

Wild-type Fur was purified with E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysE (39) containing pHB6505, a pET17b derivative. A 1-liter culture was grown from a fresh transformant at 37°C in Luria broth containing 0.4% glucose to enhance plasmid stability. At an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Amersham Life Science) was added to 1 mM, and growth was continued for 1 h. Rifampin was added to 100 μg/ml, incubation was continued for 2 h, and the cells were harvested. Cell pellets were suspended in 20 ml of disruption buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 2 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 mM NaCl, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 5% [vol/vol] bacterial protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma P8465]) containing 130 μg of hen egg white lysozyme/ml, and the suspension was incubated on ice for 10 min. Sodium deoxycholate was added to 0.05% (wt/vol), and the cell suspension was disrupted by pulsed sonication for 2 min. Lysates were diluted with 20 ml of TEDG buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 1 mM PMSF) and clarified twice by centrifugation for 15 min each time. The resulting supernatant was applied at 4°C to a heparin–Sepharose CL-6B column (Pharmacia LKB, Piscataway, N.J.), and Fur was eluted with a linear gradient of 0.05 to 1 M NaCl in TEDG buffer (it elutes near 350 mM NaCl). Fractions containing Fur were pooled, precipitated with ammonium sulfate (65% saturation), suspended in TEDG buffer, and applied to a Mono-Q (HR5/5) column for Pharmacia fast protein liquid chromatography. Fur was eluted with 350 mM NaCl, concentrated by ammonium sulfate precipitation, and resuspended in TEDG buffer containing 300 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT. Fur was further purified by fast protein liquid chromatography on a Superdex-75 column with the same buffer. As judged against molecular mass standards, Fur elutes with an apparent molecular mass of 35 kDa, as predicted for a dimer. Fur was >98% pure, as judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The glycerol concentration was adjusted to 50% (vol/vol), and Fur was stored in aliquots at −20°C. The Fur protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, Calif.) dye-binding (Bradford) assay and refers in all cases to the dimeric protein.

The percentage of purified Fur active for DNA binding can be estimated from the transcription repression experiments. In these studies, between 16 and 32 nM Fur was required to completely repress transcription from a 4 nM DNA template. Since these experiments are performed at concentrations of Fur well above the measured dissociation constant, we can estimate the fraction of active Fur as being between 0.12 and 0.25 (assuming that the binding of a single dimer is sufficient for repression). All Fur concentrations reported in this study are total protein rather than active molecules.

To estimate the metal content of Fur, Fur was dialyzed at 4°C three times against TG buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 1 mM PMSF) and analyzed by flame atomic absorption spectroscopy at the ICP Analytical Laboratory of the Cornell Department of Fruit and Vegetable Science. Iron, zinc, and nickel atomic absorption standard solutions were purchased from Sigma.

Treatment of Fur with chelators.

Two strategies were used to remove loosely associated metals from Fur. In one protocol, Fur was dialyzed at 4°C against TEDG buffer containing 25 mM EDTA and 300 mM NaCl and then dialyzed against TEDG buffer containing 1 mM DTT and 300 mM NaCl to reduce the concentration of EDTA. The glycerol concentration was adjusted to 50% (vol/vol) and Fur was stored in aliquots at −20°C. In the other protocol, Fur was preincubated with 5% (wt/vol) Chelex 100 (Bio-Rad) in electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) buffer (see below) on ice for 1 h with frequent mixing. The resin was allowed to settle, and the Fur-containing supernatant was removed and used in EMSA.

EMSAs with the dhb promoter.

A DNA fragment containing the promoter, fur box, and partial coding sequence (to codon 53) of dhbA was generated by PCR with primers 200 and 201, which incorporate HindIII and BamHI sites, respectively. The 400-bp product was cleaved with AlwNI, generating a 280-bp fragment (containing the promoter and fur box) and a 120-bp downstream fragment. DNA was end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase. Fur was equilibrated in EMSA buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 50 mM KCl, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml) for 10 min at room temperature (RT), 50 pM (1 fmol) of end-labeled DNA and 5 μg of competitor salmon testis DNA per ml were added, and incubation was continued for 10 min at RT. The reactions were analyzed next to a dye marker on a 4% nondenaturing gel (40 mM Tris-acetate) that was prerun for 10 min in Tris-acetate buffer containing 0.5 mM DTT. After 2 h at 150 V, the gel was dried and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen for analysis (STORM; Molecular Dynamics, Inc.). The data points were fit, by use of the DeltaGraph Professional reiterative curve-fitting algorithm, to an equation of the following form: percent DNA bound equals 100{1/[1 + (K/[Fur])n]}. In this equation, K represents the apparent dissociation constant for Fur binding, [Fur] is the concentration of dimeric Fur protein, and n is the cooperativity coefficient. Both K and n were independently optimized. Competition experiments were done with either the same dhb fragment or a PCR product containing the fur coding region as a nonspecific control.

In vitro transcription of the dhb promoter fragment.

The dhb-containing template and the vector control for in vitro transcription assays were generated by linearizing pHB6548 and pJPM122, respectively, with BamHI. B. subtilis core RNA polymerase and ςA preparations were described previously (25, 26). RNA polymerase holoenzyme (RNAP) was reconstituted by incubating the core with ςA (1:5 molar ratio) on ice for 15 min prior to use. The DNA template (4 nM) was preincubated with RNAP (80 nM, unless otherwise indicated) in transcription buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 50 mM KCl, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 U of RNasin RNase inhibitor per reaction) for 10 min at 37°C. To assay transcriptional repression, Fur or RNAP was preincubated with DNA for 5 min at RT or 37°C, respectively, prior to the addition of the other protein. When appropriate, 10 μM freshly dissolved FeSO4 was added. Transcription was initiated by the addition of a nucleotide mixture (400 μM each ATP, GTP, and CTP and 60 μM [α-32P]UTP; ∼3,000 cpm/pmol), and reaction mixtures were incubated for 8 min at 37°C. The reactions were stopped with 100 μl of stop solution (2.5 M ammonium acetate, 20 mM EDTA [pH 8], 0.2 mg of glycogen per ml), and nucleic acids were recovered by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation prior to resuspension in 10 μl of formamide gel loading buffer (80% formamide, 10 mM EDTA [pH 8], 1 mg of xylene cyanol FF per ml, 1 mg of bromphenol blue per ml). The samples were denatured for 4 min at 90°C and loaded on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The gel was dried and exposed to a STORM PhosphorImager screen for analysis.

Siderophore assays.

B. subtilis cultures were grown overnight at 37°C in MM with or without added FeCl3 (5 μM). Siderophore levels were determined with the Arnow assay as previously described (2, 9). Siderophore yields were normalized to the cell mass by dividing the measured siderophore level (OD510) by the culture density (OD600). All assays were performed with duplicate samples, and the values were averaged.

PCR.

The PCR mixture contained HB1000 chromosomal DNA, 50 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 100 pmol each of the forward and reverse primers, and 2 U of Vent DNA polymerase (or 1.25 U of Pfu DNA polymerase) in a total volume of 100 μl. The reaction mixtures were denatured for 2 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, 30 s at 50°C (or 55°C, depending on the primers used), and 30 s at 72°C and a final extension of 5 min at 72°C.

Megaprimer site-directed mutagenesis and complementation analysis.

The fur-containing 810-bp DNA fragment (100 bp upstream of the fur transcription start site to 220 bp downstream of the fur translation stop codon) was amplified from HB1000 chromosomal DNA with primers 140 and 139 by PCR as described above with the following modifications: cloned Pfu polymerase and Pfu buffer were used instead of Vent polymerase, the annealing temperature was 47°C, and the extension time was 1 min. The resulting product was cloned into pGEM-cat as a HindIII-BamHI fragment (pHB6524), sequenced, and then subcloned from pHB6524 into pDG1662 to generate pHB6525. For fur complementation analysis, pHB6525 was transformed into HB6637, and double-crossover recombinants were selected with chloramphenicol and screened for Spcs and macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B sensitivity, ensuring integration at amyE. The resulting strain (HB6640) was tested by siderophore assays for complementation of fur::kan. With pHB6524 as a template, the various histidine and cysteine mutants were generated by megaprimer PCR mutagenesis as described previously (35) with a few modifications. Briefly, pHB6524 was cut with HindIII and PCR amplified with the appropriate mutagenic primer (147 to 155) and primer 139 at an annealing temperature of 50°C. To enrich for the megaprimer DNA strand, the first PCR product was used as a template in a subsequent asymmetric PCR with 10-fold less of the mutagenic primer than of primer 139. The asymmetric PCR product was used with primer 140 and BamHI-cut pHB6524 as a template in a third PCR at an annealing temperature of 48°C. The final product was purified, cloned into pGEM-cat as an 810-bp HindIII-BamHI fragment (pHB6527 to pHB6534 and pHB6537), sequenced, and then subcloned into pDG1662 (pHB6538 to pHB6545 and pHB6547). The pDG1662-derived plasmids were then integrated into HB6637 (fur null mutant) and HB6634 (fur wild type) (HB6650 to HB6663, HB6668, HB6670, HB6672, and HB6673) to study complementation and recessiveness to wild-type Fur, respectively.

Immunoprecipitation of Fur from 35S-Met-labeled cells.

Cells were grown to the late logarithmic phase in MM without iron supplementation. Aliquots (1.6 ml) were labeled with l-[35S]methionine (20 μCi; 1,175 Ci/mmol) for 45 min, chased with nonradioactive methionine (2.5 mM), cooled on ice, and centrifuged. Cell pellets were washed with 0.8 ml of glucose buffer (50 mM glucose, 25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8]), resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer (glucose buffer with 0.1 mg of lysozyme per ml), and incubated on ice for 10 min. One hundred microliters of detergent solution (2% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate) was added, and the samples were vortexed and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was preadsorbed to 50 μl of protein G-agarose suspension (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) for 3 h. After centrifugation for 20 s, the supernatant was incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-FurEC antibodies for 1 h, 50 μl of protein G-agarose was added, and incubation was continued overnight. The pellets were washed in the buffers recommended by the manufacturer (Boehringer). All of the previous incubations were performed at 4°C on a rocking platform, unless otherwise indicated. The pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of gel loading buffer, boiled for 5 min, and centrifuged, and the immunoprecipitated proteins in the supernatant were separated by SDS–12% PAGE. The gel was dried and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen for analysis.

RESULTS

Overproduction, purification, and physical characterization of Fur.

The fur gene was cloned into pET17b, and Fur was overproduced in E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysE (39). Since the fur gene was toxic for E. coli, it was necessary to use pLysE to stabilize the pET transformants (38). The overproduced Fur was almost equally distributed between inclusion bodies and the extract supernatant and was purified to homogeneity from the supernatant. Purification was achieved by chromatography on heparin-Sepharose, Mono-Q, and Superdex-75. Fur elutes from the Superdex-75 column with an apparent molecular mass of 35 kDa, in agreement with its calculated dimeric mass, and with the dimeric state of FurEC in solution (4, 12). From promoter titration experiments (see Materials and Methods and below), we estimate that between 12 and 25% of the isolated Fur is active for DNA binding.

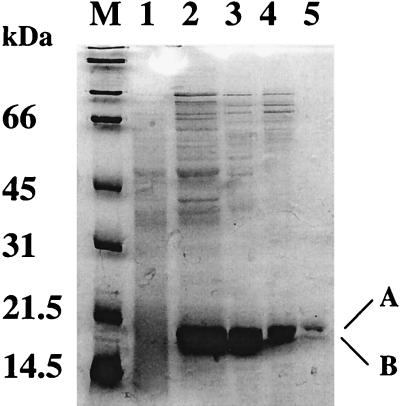

As purified, Fur migrates on SDS-polyacrylamide gels as a doublet, with the predominant and larger product (A) corresponding to the expected molecular mass of 17.4 kDa (Fig. 1). The identities of the purified proteins (A and B, separately) were confirmed by amino-terminal sequencing of the first 10 amino acid residues, which matched the predicted Fur sequence (8). Unlike FurEC (40), B. subtilis Fur retains its N-terminal methionine. The faster-migrating band (B) could be either an isoform of Fur with altered mobility or a degradation product. This band was observed consistently despite the addition of a cocktail of protease inhibitors during cell lysis. Since the two isoforms persist even after reduction with freshly prepared β-mercaptoethanol or DTT, it is unlikely that there is an intramolecular disulfide bond. Therefore, we tentatively conclude that the smaller band is truncated at its C terminus. A protease-sensitive region has also been observed in the C-terminal region of FurEC mutants altered in either of two conserved cysteines (11). Preliminary atomic absorption spectroscopy indicates that zinc but neither iron nor manganese copurifies with Fur (calculated molar ratio of Zn to Fur of between 2 and 3).

FIG. 1.

Purification of Fur and SDS–12% PAGE analysis of fractions from the purification of Fur. Lanes: M, molecular mass standards; 1 and 2, total proteins from uninduced and IPTG-induced BL21(DE3)/pLysE/pHB6505, respectively; 3, pooled fractions from heparin-Sepharose; 4, pooled fractions from Mono-Q; 5, fraction from Superdex-75. Fur runs just below the 21.5-kDa marker, and the Fur doublet is indicated by A and B on the right.

Fur binds specifically to the dhb promoter region.

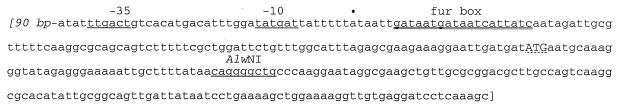

Purified Fur was assayed for DNA binding in EMSAs with a 400-bp fur box-containing dhb promoter fragment cleaved with AlwNI to generate a 280-bp fur box-containing fragment and a 120-bp control fragment (Fig. 2). When incubated with the dhb promoter fragment, 10 nM Fur caused an electrophoretic mobility shift of the larger, fur box-containing fragment but not the fragment lacking a fur box (Fig. 3A, lane 2). The specificity of the interaction of Fur with the dhb promoter fragment was tested in competition assays with either the same dhb DNA fragment or an unrelated DNA fragment generated by PCR. Fur at 10 nM was first incubated with 50 pM end-labeled dhb fragment before the addition of 10 or 100 nM cold competitor DNA, and incubation was continued for another 10 min at RT (Fig. 3B). While the dhb promoter region efficiently competed for binding, the nonspecific DNA did not compete, even when present in a 10-fold molar excess (100 nM) over Fur. This result demonstrates that Fur specifically interacts with the dhb fur box-containing promoter element. The inability of 10 nM Fur to efficiently shift labeled DNA in the presence of 10 nM dhb competitor is consistent with our estimation of the fraction of active Fur as being between 12 and 25%.

FIG. 2.

dhb promoter-operator region. The −35 and −10 regions of the dhb ςA-dependent promoter (33) are indicated by underlining. The fur box required for iron-mediated repression of dhb transcription (33) is indicated by double underlining, and the start codon (ATG) for dhbA is shown in uppercase letters. The fragment used in the EMSA experiments extends from ∼90 bp upstream of the −35 element (as indicated) to the right bracket. The AlwNI site used to bisect the dhb fragment for EMSA experiments is indicated.

FIG. 3.

Specific binding of Fur to the dhb regulatory region. (A) The dhb promoter fragment (50 pM) was cut with AlwNI, end labeled, and incubated with native or EDTA-treated Fur. Lanes: 1, no Fur; 2, 10 nM Fur; 3, 10 nM EDTA-treated Fur. The positions of the unbound fur box and the shifted complex are indicated by unbound and bound, respectively. (B) The dhb promoter fragment (50 pM) was incubated with Fur for 10 min prior to the addition of cold competitor DNA. Lanes: 1, no Fur; 2, 10 nM Fur; 3, 10 nM Fur and 10 nM dhb competitor DNA; 4, 10 nM Fur and 100 nM dhb competitor DNA; 5, 10 nM Fur and 10 nM nonspecific competitor DNA; 6, 10 nM Fur and 100 nM nonspecific competitor DNA. The shifted complex is displaced only by the addition of the specific dhb competitor DNA.

Effects of Fe(II) on the binding of Fur to the dhb promoter region.

DNA binding by Fur is thought to require an activating metal ion. We attempted to remove loosely associated metal ions from Fur by dialysis against buffer containing 25 mM EDTA followed by dialysis against buffer lacking EDTA. Surprisingly, the EDTA-treated Fur was just as active as the native Fur in EMSAs (Fig. 3A, lane 3). Similarly, treatment of Fur with Chelex did not inhibit DNA binding (data not shown). Thus, purified Fur binds to the dhb promoter fragment in the absence of any added metal ions, and any copurifying metal ions required for binding (e.g., zinc) appear to be tightly associated and not easily removed by chelating agents.

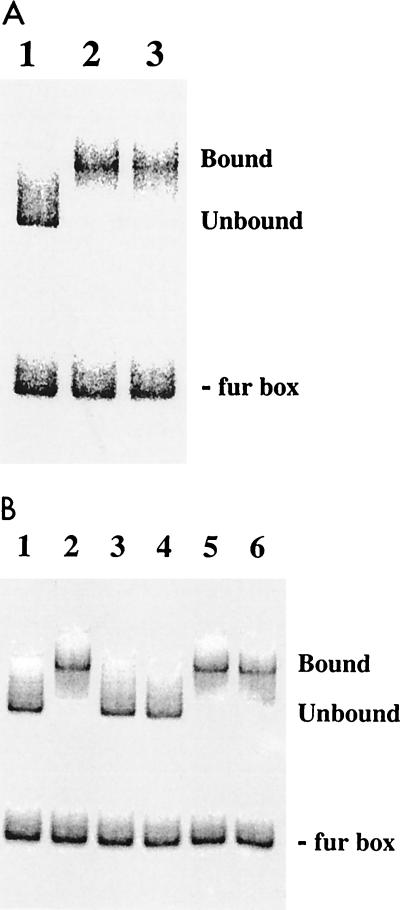

B. subtilis Fur represses dhb expression in vivo in response to iron (8, 33). However, as purified, Fur is able to bind to DNA specifically in the absence of added iron. To clarify the discrepancy between the in vitro and in vivo data, we wished to determine if Fe(II) increases the affinity of Fur for the dhb promoter fragment. EMSAs were conducted over a range of Fur concentrations (0.06 to 128 nM) in the presence and absence of added ferrous ion (Fig. 4). In the absence of added iron, the best-fit binding curve corresponded to a Kd (apparent) of 4.6 nM (corresponding to a Kd of ∼0.8 nM when corrected for active protein) and a cooperativity coefficient of 2, perhaps indicating oligomerization of Fur concomitant with DNA binding. In the presence of added iron, the calculated affinity of Fur for DNA was enhanced twofold (apparent Kd, 2.3 nM) and cooperativity was slightly increased (cooperativity coefficient, ∼3). These results suggest that Fe(II) does increase, albeit only modestly, the interaction of Fur with the fur box-containing fragment.

FIG. 4.

Effect of added Fe(II) on the affinity of Fur for the dhb promoter region. A curve for the binding of Fur to the dhb promoter fragment in the presence and absence of Fe(II) is shown. Fur (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 nM) in the presence of Fe(II) (■) and Fur (0.06, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 nM) in the absence of Fe(II) (●) were incubated with 50 pM end-labeled template and separated by nondenaturing PAGE, and the percentages of bound and unbound DNA were determined by PhosphorImager analysis with the program ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics, Inc.).

Repression of dhb transcription by Fur in vitro.

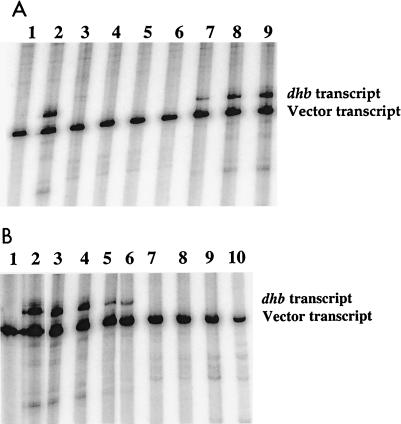

Despite the lack of a dramatic effect on DNA-binding affinity, we hypothesized that Fe(II) might nevertheless stabilize a conformation of Fur necessary for efficient transcriptional repression. To test this idea, purified B. subtilis ςA holoenzyme was used to transcribe a linearized plasmid DNA template to produce a 268-bp runoff dhb transcript together with a smaller, vector-derived transcript that serves as a control for nonspecific effects of Fur (Fig. 5A, lane 2). As expected, when the vector alone was used as a template, the larger, dhb transcript was not observed (Fig. 5A, lane 1). Fur (4 to 80 nM) was preincubated with the dhb template (4 nM) prior to the addition of 80 nM RNAP. Repression of the dhb transcript was evident at 16 nM Fur and was complete at 32 nM Fur. Fur did not repress the vector-derived transcript at any of the concentrations tested. Thus, Fur specifically represses dhb transcription.

FIG. 5.

Fur specifically represses dhb transcription. (A) Addition of Fur before RNAP. The linearized vector (lanes 1 and 3) or the dhb-containing template DNA (lanes 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) (4 nM) was incubated with 80 nM RNAP for 10 min at 37°C (lanes 1 and 2) or with Fur for 5 min at RT prior to the addition of 80 nM RNAP and incubation for another 5 min at 37°C (lanes 3 to 9). Lanes: 1 and 2, no Fur; 3 and 4, 80 nM Fur; 5, 64 nM Fur; 6, 32 nM Fur; 7, 16 nM Fur; 8, 8 nM Fur; 9, 4 nM Fur. The positions of the dhb transcript and the vector transcript are indicated on the right. (B) Addition of Fur after RNAP. The linearized vector (lane 1) or the dhb-containing template DNA (lanes 2 to 10) (4 nM) was incubated with 80 nM RNAP for 10 min at 37°C (lanes 1 and 2) or preincubated with 80 nM RNAP for 5 min at 37°C prior to the addition of Fur alone (lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9) or Fur and Fe(II) (lanes 4, 6, 8, and 10) and incubation for another 5 min at RT. Lanes: 1 and 2, no Fur; 3, 4 nM Fur; 4, 4 nM Fur and 10 μM Fe(II); 5, 16 nM Fur; 6, 16 nM Fur and 10 μM Fe(II); 7, 64 nM Fur; 8, 64 nM Fur and 10 μM Fe(II); 9, 256 nM Fur; 10, 256 nM Fur and 10 μM Fe(II). The positions of the dhb transcript and the vector transcript are indicated on the right.

To determine if Fe(II) affects the ability of Fur to repress transcription, we measured transcriptional repression in the presence and absence of freshly prepared 10 μM Fe(II). In these studies, we altered the order of addition such that the DNA template was preincubated first with RNAP and then with Fur for 5 min prior to initiation of the transcription reactions. Once again, 16 nM Fur led to significant repression, which was complete at 32 nM Fur (Fig. 5B). The addition of Fe(II) did not affect the ability of Fur to repress the transcription of dhb. However, there was some repression of the vector-derived transcript at the highest Fur concentration tested (256 nM), and this effect did require iron.

Repression of dhb transcription by Fur in vivo: role of conserved histidine and cysteine residues in repression.

While iron is required for the in vivo repression of siderophore biosynthesis, our in vitro studies indicate that Fe(II) addition is not required for the specific binding and repression of dhb transcription. In contrast, in other studies of FurEC, the addition of divalent cations is typically required to observe DNA binding (3, 14, 22). Unfortunately, little is known about the actual mechanism of iron sensing by Fur proteins, although it is thought that binding involves a subset of the conserved histidine and cysteine residues in the carboxyl-terminal domain.

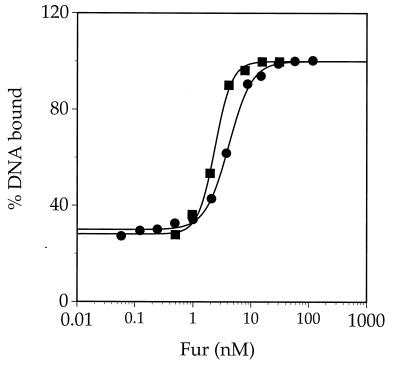

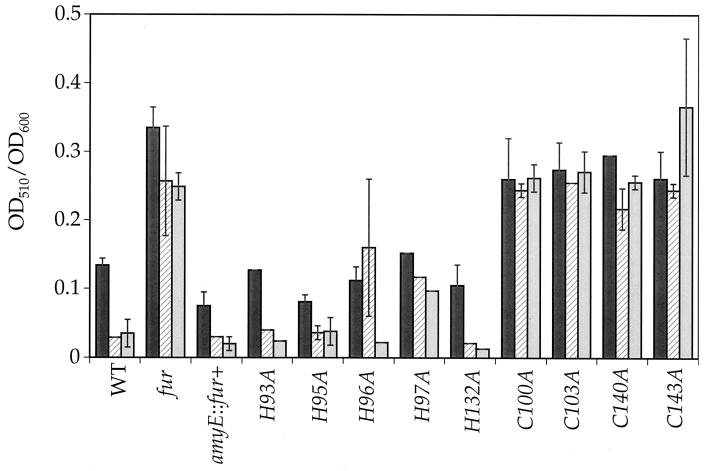

We used site-directed mutagenesis of the fur gene to individually alter nine cysteine and histidine residues to alanine. We inserted the wild-type and mutant fur genes in single copies at amyE and tested for complementation of a fur null mutant (Fig. 6). As an indirect measure of the transcriptional activity of the dhb locus, we monitored the levels of siderophores (dihydroxybenzoic acid and dihydroxybenzoyl serine) present in cell supernatants after growth in the presence of various concentrations of iron. In this assay, the H93A-, H95A-, and H132A-expressing strains all displayed a pattern of iron-mediated repression not significantly different from that of the wild type. In contrast, the strains expressing mutant Fur proteins altered in any of the four Cys residues were completely derepressed for dhb expression, similar to the fur null mutant. The H96A and H97A Fur mutants appeared to have altered function. While the H97A mutant protein displayed very little iron responsiveness, it did not yield a completely derepressed null phenotype. The H96A mutant protein had the most interesting phenotype: it displayed a level of basal activity similar to that of the wild type and mediated full repression of dhb at 50 μM but not 5 μM added iron.

FIG. 6.

Complementation of fur::kan by the various histidine-to-alanine and cysteine-to-alanine fur mutations. The mutations were inserted at amyE in HB6637 (fur::kan) by a double recombination event, the strains were grown in MM in the absence (dark gray bar) or presence of 5 μM Fe(III) (hatched bar) or 50 μM Fe(III) (light gray bar), and catechol siderophore yields were expressed as OD510/OD600 ± standard deviations. WT, wild type.

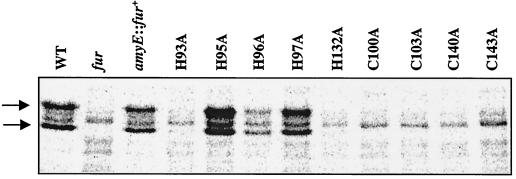

To determine whether the null phenotypes observed for some of the mutants (Fig. 6) were due to instability of the mutant proteins, we labeled the various B. subtilis mutant strains with l-[35S]methionine, immunoprecipitated Fur from whole-cell extracts by using polyclonal antibodies against FurEC, and analyzed the precipitates by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 7). These antibodies cross-react with purified B. subtilis Fur in dot blot assays (data not shown) and allow visualization of a protein with the expected size for Fur (17.4 kDa) in the wild-type strain but not in a fur mutant strain. In addition to full-length Fur, a smaller protein is also detected. This is likely to be a degradation product of Fur, since it is missing from the fur mutant strain.

FIG. 7.

Fur is destabilized by all four cysteine mutations and two of the histidine mutations. Pulse-labeled fur mutants were lysed, and Fur was immunoprecipitated from the extracts with polyclonal antibodies against E. coli Fur and protein-G agarose beads. The immunoprecipitated proteins in the supernatant were separated by SDS–12% PAGE, and the gel was analyzed by PhosphorImager analysis. Arrows show full-length Fur (upper band) and a Fur degradation product (lower band). WT, wild type.

The immunoprecipitation experiment revealed nearly wild-type levels of Fur in the strains expressing the H95A, H96A, and H97A proteins. The presence of essentially wild-type levels of H96A Fur and H97A Fur is significant, since these proteins had altered responses to iron in vivo. The H93A and H132A proteins were present at very low levels in this assay, despite their nearly normal biological activity. We do not know whether the reduced levels of these proteins resulted from instability in vivo or during the immunoprecipitation procedure. The lack of signal for the four Cys mutant proteins suggests that these proteins may fail to accumulate in vivo, consistent with their null phenotypes, with the stability defects of two FurEC Cys mutant proteins (11), and with the finding that these mutant proteins are unstable when overproduced in E. coli (data not shown). Although it seems unlikely, we cannot yet rule out the possibility that one or more of these mutations may affect the ability of these antisera to recognize Fur.

DISCUSSION

We report the purification and initial characterization of the DNA- and metal-binding properties of B. subtilis Fur, the first member of the Fur family to be biochemically characterized from a gram-positive organism.

In vitro repression of the dhb promoter.

B. subtilis Fur acts as an iron-dependent repressor of the dhb operon in vivo (8, 33). However, in vitro Fe(II) failed to significantly affect either the affinity of Fur for the dhb operator (Fig. 4) or the ability of Fur to repress transcription (Fig. 5). We conclude that in vitro Fur is an iron-independent repressor of dhb transcription. Interestingly, Fur efficiently represses transcription even if RNAP is incubated with the dhb promoter region prior to the addition of Fur. This finding suggests either that Fur can bind to the promoter region downstream of prebound RNAP or that Fur can displace RNAP. Further studies are needed to distinguish between these possibilities. For comparison, in vitro studies have demonstrated that neither FurEC nor E. coli RNAP can displace the other (15, 16).

Interactions of Fur with metal ions.

FurEC is the prototype for a large family of metal-dependent repressors (22), including three functionally distinct B. subtilis homologs (8, 17). It is generally accepted that Fur binds to Fe(II) in vivo and is thereby activated to bind DNA, leading to the repression of iron uptake functions. However, the interaction of Fur with metal ions is not well understood.

The most unexpected finding from this work is the lack of a requirement for added iron for either DNA binding or transcriptional repression in vitro. As purified, B. subtilis Fur contains zinc, as reported for FurEC (24), but little or no iron. Moreover, DNA binding is insensitive to treatment of Fur with chelating agents, including dialysis against EDTA or incubation with Chelex, and is not appreciably enhanced by the addition of Fe(II). Thus, if metal ions are required to activate Fur for DNA binding, they appear to be tightly bound under our purification conditions.

FurEC binds at least two metal ions per monomer in a carboxyl-terminal metal-binding domain that contains several conserved histidine and cysteine residues (11, 12, 24). FurEC has recently been found to be a zinc metalloprotein (24) with a tightly associated zinc ion thought to play a structural role. This ion is coordinated with two sulfur ligands, perhaps Cys92 and Cys95 (equivalent to Cys100 and Cys103 in B. subtilis Fur), and two nitrogen or oxygen ligands. Further analyses have revealed that Fur purified in the presence of chelators retains a single zinc ion (Zn1Fur), while in the absence of chelators each monomer binds two zinc ions (Zn2Fur) (1). Remarkably, both forms bind DNA with similar affinities (1), consistent with our findings that Fur from B. subtilis contains associated zinc and binds DNA even in the absence of added iron.

The second, lower-affinity metal-binding site is presumed to be the regulatory site. In vivo, FurEC maintains a level of free (chelatable) iron near 10 μM (27). Thus, the in vivo dissociation constant for the functional interaction of Fe with Fur is probably near 10 μM. In vitro studies have suggested that FurEC can be activated for DNA binding by several divalent ions, including Co(II), Cu(II), Cd(II), Fe(II), and Mn(II) (14). Similar results have been obtained with Pseudomonas aeruginosa Fur (30). The origins of the in vivo metal selectivity of Fur-mediated repression, in view of the promiscuous metal-binding properties of the purified protein, are not yet clear. Presumably, levels of free metal ions in the cell are tightly regulated, and only iron (and under some conditions, manganese) (5, 21, 32) achieves a sufficient level to effect repression.

A model for interactions of B. subtilis Fur with metal ions.

We currently favor a model for Fur that includes roles for both a structural zinc-binding site and a regulatory site that senses the presence of iron. Our in vivo studies of Fur-mediated repression indicate that two histidines (H96 and H97, corresponding to D89 and H90 in both FurEC and Salmonella typhimurium Fur) are likely candidates for Fe(II) ligands. A role for these residues in binding iron is consistent with the finding that S. typhimurium H90 mutants are iron blind (20). Curiously, mutation of these residues in FurEC failed to affect iron-dependent regulation (11).

How can we reconcile the apparent lack of a requirement for an activating metal ion in vitro with the well-documented effects of iron on in vivo activity? We suggest that in vivo Fur is bound to an inhibitor of DNA binding that is antagonized by iron. In principle, this inhibitor might be another protein, a low-molecular-weight ligand, or another metal ion. The last possibility is particularly attractive, as it is easy to imagine how another metal ion might compete for the Fe(II)-binding site. A corollary of this hypothesis is that this alternate form of Fur might be active for DNA binding at some sites, albeit not those associated with the regulation of iron uptake functions.

This model is consistent with several observations. First, the ability of S. typhimurium H90A Fur to function in the acid tolerance response, despite an inability to repress siderophore biosynthesis genes, suggests that Fur lacking bound Fe(II) may still have DNA-binding activity (20). Second, Fur proteins containing different metal ions have distinct DNA-binding specificities. For example, while most PerR-regulated genes can be repressed by either iron or manganese, the fur gene is repressed only by manganese (7–10 and unpublished data). Similarly, repression of the sodA gene by FurEC is effected only by iron, while either iron or manganese can lead to repression of the aerobactin genes (32). By extension, it is easy to imagine that in vivo a divalent metal ion binds Fur and stabilizes a conformation inactive for binding to iron-regulated target sites (although not, perhaps, to other target sites) and that only upon displacement by Fe(II) is the ability to bind to iron-regulated promoter regions recovered. Indeed, previous studies indicated that the supplementation of growth medium with some divalent cations can derepress siderophore biosynthesis and the expression of Fur-regulated genes (9).

In summary, our work confirms the notion that iron regulation in B. subtilis is mediated by a Fur homolog that binds directly to a fur box, as inferred from previous genetic analyses. However, we have not yet been able to demonstrate iron-responsive DNA binding in vitro because the protein binds tightly to DNA in the absence of added iron. We suggest that in vivo there is an inhibitory factor, perhaps a metal ion, absent from our in vitro system. We are presently exploring this possibility by using crude extracts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Vasil for providing the anti-E. coli Fur antibodies.

This work was supported by NSF grant MCB9630411.

REFERENCES

- 1.Althaus E W, Outten C E, Ohlsen K E, Cao H, O’Halloran T V. The ferric uptake regulation (Fur) repressor is a zinc metalloprotein. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6559–6569. doi: 10.1021/bi982788s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnow L E. Colorimetric determination of the components of 3,4 dihydroxyphenylalanine-tyrosine mixtures. J Biol Chem. 1937;228:531–537. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagg A, Neilands J B. Ferric uptake regulation protein acts as a repressor, employing iron (II) as a cofactor to bind the operator of an iron transport operon in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1987;26:5471–5477. doi: 10.1021/bi00391a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagg N, Neilands J B. Molecular mechanism of regulation of siderophore-mediated iron assimilation. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:509–518. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.4.509-518.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bearden S W, Staggs T M, Perry R D. An ABC transporter system of Yersinia pestis allows utilization of chelated iron by Escherichia coli SAB11. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1135–1147. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1135-1147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun V. Avoidance of iron toxicity through regulation of bacterial iron transport. Biol Chem. 1997;378:779–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bsat N, Chen L, Helmann J D. Mutation of the Bacillus subtilis alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (ahpCF) operon reveals compensatory interactions among hydrogen peroxide stress genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6579–6586. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6579-6586.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bsat N, Herbig A, Casillas-Martinez L, Setlow P, Helmann J D. Bacillus subtilis contains multiple Fur homologs: identification of the iron uptake (Fur) and peroxide regulon (PerR) repressors. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:189–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, James L P, Helmann J D. Metalloregulation in Bacillus subtilis: isolation and characterization of two genes differentially repressed by metal ions. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5428–5437. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5428-5437.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L, Keramati L, Helmann J D. Coordinate regulation of Bacillus subtilis peroxide stress genes by hydrogen peroxide and metal ions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8190–8194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coy M, Doyle C, Besser J, Neilands J B. Site-directed mutagenesis of the ferric uptake regulation gene of Escherichia coli. BioMetals. 1994;7:292–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00144124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coy M, Neilands J B. Structural dynamics and functional domains of the Fur protein. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8201–8210. doi: 10.1021/bi00247a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutting S M, VanderHorn P B. Genetic analysis. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 1990. pp. 27–74. [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Lorenzo V, Wee S, Herrero M, Neilands J B. Operator sequences of the aerobactin operon of plasmid ColV-K30 binding the ferric uptake regulation (fur) repressor. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2624–2630. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2624-2630.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escolar L, de Lorenzo V, Perez-Martin J. Metalloregulation in vitro of the aerobactin promoter of Escherichia coli by the Fur (ferric uptake regulation) protein. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:799–808. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6211987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escolar L, Perez-Martin J, de Lorenzo V. Coordinated repression in vitro of the divergent fepA-fes promoters of Escherichia coli by the iron uptake regulation (Fur) protein. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2579–2582. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2579-2582.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaballa A, Helmann J D. Identification of a zinc-specific metalloregulatory protein, Zur, controlling zinc transport operons in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5815–5821. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5815-5821.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerinot M L. Microbial iron transport. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:743–772. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guérout-Fleury A-M, Frandsen N, Stragier P. Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1996;180:57–61. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall H K, Foster J W. The role of Fur in the acid tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium is physiologically and genetically separable from its role in iron acquisition. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5683–5691. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5683-5691.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hantke K. Selection procedure for deregulated iron transport mutants (fur) in Escherichia coli K-12: fur not only affects iron metabolism. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;210:135–139. doi: 10.1007/BF00337769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hantke K, Braun V. Control of bacterial iron transport by regulatory proteins. In: Silver S, Walden W, editors. Metal ions in gene regulation. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1997. pp. 11–44. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helmann J D. Metal cation regulation in Gram-positive bacteria. In: Silver S, Walden W, editors. Metal ions in gene regulation. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1997. pp. 45–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacquamet L, Aberdam D, Adrait A, Hazemann J-L, Latour J-M, Michaud-Soret I. X-ray absorption spectroscopy of a new zinc site in the Fur protein from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2564–2571. doi: 10.1021/bi9721344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juang Y L, Helmann J D. The δ subunit of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase: an allosteric effector of the initiation and core-recycling phases of transcription. J Mol Biol. 1994;239:1–14. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juang Y L, Helmann J D. A promoter melting region in the primary ς factor of Bacillus subtilis: identification of functionally important aromatic amino acids. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1470–1488. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keyer K, Imlay J A. Superoxide accelerates DNA damage by elevating free-iron levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13635–13640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neilands J B. Siderophores. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;302:1–3. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neilands J B. Siderophores: structure and function of microbial iron transport compounds. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26723–26726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochsner U A, Vasil A I, Vasil M L. Role of the ferric uptake regulator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the regulation of siderophores and exotoxin A expression: purification and activity on iron-regulated promoters. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7194–7201. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7194-7201.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perego M. Integrational vectors for genetic manipulation in Bacillus subtilis. In: Sonenshein A L, editor. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 615–624. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Privalle C T, Fridovich I. Iron-specificity of the Fur-dependent regulation of the biosynthesis of the manganese-containing superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5178–5181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowland B M, Taber H. Duplicate isochorismate synthase genes of Bacillus subtilis: regulation and involvement in the biosyntheses of menaquinone and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:854–861. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.854-861.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Séraphin B, Kandels-Lewis S. An efficient PCR mutagenesis strategy without gel purification that is amenable to automation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3276–3277. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.16.3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slack F J, Mueller J P, Sonenshein A L. Mutations that relieve nutritional repression of the Bacillus subtilis dipeptide permease operon. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4605–4614. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4605-4614.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stojilkovic I, Hantke K. Functional domains of the Escherichia coli ferric uptake regulator protein (Fur) Mol Gen Genet. 1995;247:199–205. doi: 10.1007/BF00705650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Studier F W. Use of bacteriophage lysozyme to improve an inducible T7 expression system. J Mol Biol. 1991;219:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90855-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wee S, Neilands J B, Bittner M L, Hemming B C, Haymore B L, Seetharam R. Expression, isolation and properties of Fur (ferric uptake regulation) protein of Escherichia coli K12. Biol Metals. 1988;1:62–68. doi: 10.1007/BF01128019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Youngman P. Use of transposons and integrational vectors for mutagenesis and construction of gene fusions in Bacillus species. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 1990. pp. 221–266. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuber P, Losick R. Role of AbrB in Spo0A- and Spo0B-dependent utilization of a sporulation promoter in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2223–2230. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.2223-2230.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]