Abstract

Introduction

Though severe illness due to COVID-19 is uncommon in children, there is an urgent need to better determine the risk factors for disease severity in youth. This study aims to determine the impact a preexisting endocrine diagnosis has on severity of COVID-19 presentation in youth.

Methods

The cross-sectional chart review study included all patients less than 25 years old with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR at St. Louis Children's Hospital between March 2020 and February 2021. Electronic medical record data for analysis included patient demographics, BMI percentile, inpatient hospitalization or admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), and the presence of a preexisting endocrine diagnosis such as diabetes mellitus (type 1 and type 2), adrenal insufficiency, and hypothyroidism. Two outcome measures were analyzed in multivariate analysis: inpatient admission and PICU admission. Adjusted odds ratios with a 95% CI were calculated using binary logistic regression, along with p values after Wald χ<sup>2</sup> analysis.

Results

390 patients were included in the study. Mean age was 123.1 (±82.2) months old. 50.3% of patients were hospitalized, and 12.1% of patients were admitted to intensive care. Preexisting diagnoses of diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hypothyroidism were associated with an increased risk of hospital and ICU admission, independent of socioeconomic status.

Discussion/Conclusion

This study provides evidence that unvaccinated youth with a preexisting diagnosis of obesity, hypothyroidism, or diabetes mellitus infected with COVID-19 are more likely to have a more severe clinical presentation requiring inpatient hospital admission and/or intensive care.

Keywords: COVID-19, Obesity, Diabetes, Adrenal insufficiency, Hypothyroidism

Introduction

More than 12 million children in the USA have been diagnosed with COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, representing approximately 18.9% of cumulative cases [1]. Though most children with COVID-19 do not develop severe disease or require specific therapy, children with certain medical conditions may be at increased risk for severe disease, and therefore may be eligible for therapeutic strategies to prevent disease progression [2]. Recent studies have looked at potential risk factors for severe COVID-19 presentation to guide these recommendations and have shown that diabetes mellitus and obesity are endocrine disorders that pose a significant risk for severe disease in both children and adults with COVID-19 [3, 4]. The impact of other preexisting endocrine disorders such as hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency on the clinical presentation of COVID-19 in youth has not been evaluated. Such studies may inform practitioners about potential patient groups at increased risk for developing severe infection and guide pediatric-specific recommendations for the treatment of COVID-19. Furthermore, it may help guide prioritization strategies for vaccination and therapeutic interventions in limited resource settings. This study aimed to determine if preexisting endocrine disorders such as adrenal insufficiency, obesity, overweight, diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism in youth are associated with higher rates of severe COVID-19.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Washington University School of Medicine and Saint Louis Children's Hospital (SLCH), a 400-bed pediatric hospital with a 40-bed pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), in Saint Louis, MO, USA. The study was approved by the university's Human Research Protection Office Committee. Chart review was performed on all patients less than 25 years old who had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR at St. Louis Children's Hospital between March 2020 and February 2021.

After chart review, data from the electronic medical record (EPIC) was collected for analysis. These measures included: age, sex, patient's address, BMI percentile, inpatient hospitalization or admission to the PICU, and the history of a preexisting endocrine diagnosis such as diabetes mellitus (type 1 and type 2), adrenal insufficiency, and hypothyroidism. The diagnosis of endocrinopathy in all patients included in this study preceded infection with COVID-19. Patients with preexisting primary or central hypothyroidism, regardless of whether they presented to the hospital biochemically euthyroid, were classified as having a diagnosis of hypothyroidism in this study. Patients were classified as having a history of adrenal insufficiency if they had a preexisting diagnosis of primary or central adrenal insufficiency or if they had a history of chronic use of high dose oral steroids that could cause adrenal suppression and be at risk for disturbed stress response during infectious stress [5]. Patients were classified as normal weight, overweight, or obese based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition [6]. Obese patients were defined as having a BMI percentile greater than 95, and overweight patients were defined as having a BMI percentile greater than 85 but less than 95. BMI percentiles were calculated using the PediTools Electronic Growth Chart Calculators with the 2000 CDC growth chart used for reference [7, 8]. To provide continuity from childhood to adulthood, we used the age 20 reference to calculate BMI percentiles when individuals were 20 years of age or older, as others have done [9, 10, 11]. Socioeconomic status was calculated using the patient's address and the Neighborhood Atlas® software from the University of Wisconsin [12]. This software uses the 2018 American Community Survey to generate a National Percentile Area Deprivation Index (ADI), which allows for an objective comparison of socioeconomic status across the USA. Severity of COVID-19 disease was determined by the need for inpatient admission and PICU admission, which is similar to the definitions in other literature [4].

Descriptive statistics were performed on all variables. Mean, standard deviations, and confidence intervals were calculated. To examine the association between patients admitted to inpatient care, or PICU, with a preexisting endocrine disorder, binary logistic regression was performed. Two outcome measures were analyzed in multivariate analysis: inpatient admission and PICU admission. ADI score, obesity, diabetes mellitus, adrenal insufficiency, age, and hypothyroidism were included in binary logistic regression due to either statistical significance or clinical importance. Adjusted odds ratios with 95% CI were calculated, along with p values after Wald χ2 analysis. Results were interpreted as statistically significant if p < 0.05 in two-tailed tests. Analyses were performed with statistical package SPSS© Version 27 for Mac. Graphics were produced using Adobe Illustrator and PRISM.

Results

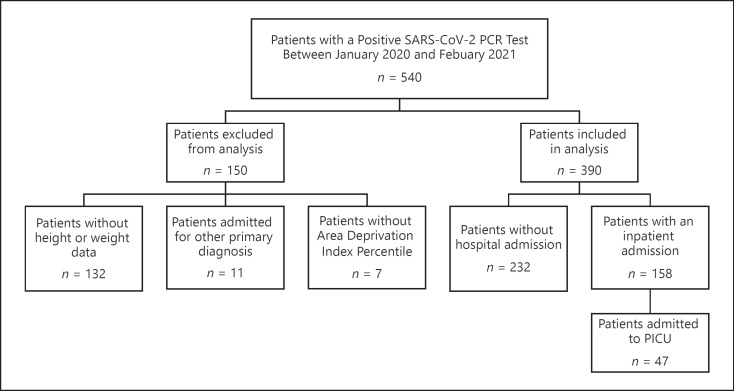

As shown in Figure 1, 540 patients had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test at St. Louis Children's Hospital between March 2020 and February 2021. 150 patients were excluded from the analysis: 132 patients were missing BMI data, 11 were admitted to SLCH for either trauma or emergent surgery, and 7 were excluded due to missing socioeconomic data.

Fig. 1.

Total number of cases considered for data analysis after excluding for invalid records and missing data.

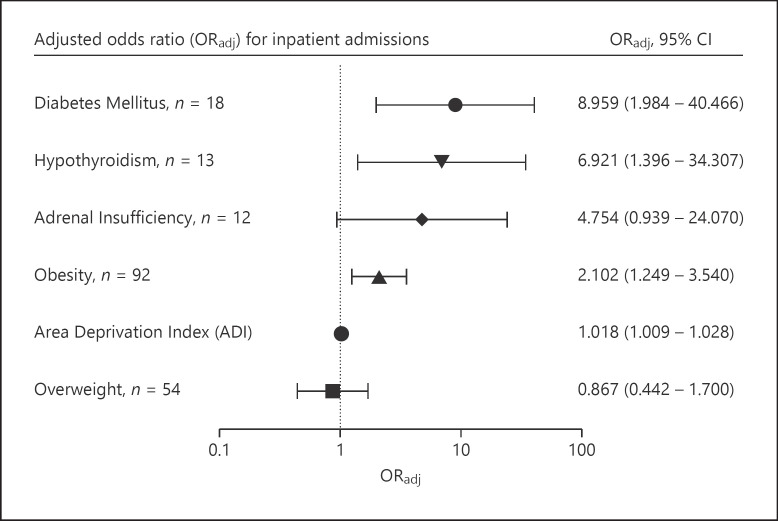

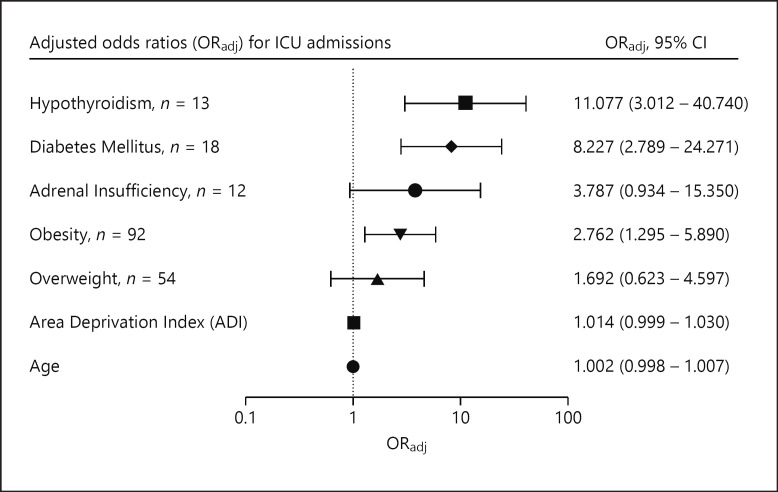

The remaining 390 patients were included in this study. Population characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 123.1 months old (SD = 82.2), and 194 (49.7%) of the patients were male. Mean ADI was 63.63 (SD = 25.4) The most prevalent endocrine condition among the patients studied was obesity, followed by overweight and diabetes mellitus (both type 1 and type 2). The mean HbA1c of those with diabetes was 11.0% (SD = 3.2.). 158 (40.5%) patients were admitted, with 47 (12.1%) patients admitted to intensive care. Of the 13 patients with a preexisting diagnosis of hypothyroidism, 1 had central hypothyroidism and the rest had primary hypothyroidism. Only 2 of the patients were biochemically hypothyroid at the time of positive COVID-19 testing, and all others were euthyroid. Eleven of the 13 patients were hospitalized, and the two nonadmitted were euthyroid. Of the patients with endocrinopathies included in the study, 4 patients had coexisting hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency, and all 4 of these patients were admitted to the hospital. In addition, one patient had coexisting hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus, and 2 patients had coexisting diabetes and adrenal insufficiency. National percentile socioeconomic status, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hypothyroidism were associated with an increased odds of inpatient admission (p < 0.05). As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, after controlling for age, SES, weight, hypothyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency in the multivariate model, children with diabetes had 8.96 times increased odds of being admitted than kids without diabetes. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 3, adrenal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and obesity were associated with an increased odds of PICU admission (p < 0.05). While not statistically significant when considering p values, adrenal insufficiency had an adjusted odds ratio of 1.692 (95% CI: 0.934–15.350), suggesting a possible association between adrenal insufficiency and an increased odds of intensive care.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study participants

| Inpatient admission |

PICU admission |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yes (n = 158), n (%) | no (n = 232), n (%) | yes (n = 47), n (%) | no (n = 343), n (%) | n = 390, n (%) | |

| Age | |||||

| Mean age in months (σ) | 125.3 (83.3) | 121.57 (81.6) | 151.9 (75.2) | 119.1 (82.4) | 123.1 (82.2) |

| Area deprivation index (ADI) | |||||

| Mean ADI (σ) | 71.0 (22.7) | 58.6 (25.9) | 71.6 (21.7) | 62.5 (25.7) | 63.63 (25.4) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 118 (50.9) | 76 (48.1) | 23 (48.9) | 171 (49.9) | 194 (49.7) |

| Female | 114 (49.1) | 82 (51.9) | 24 (51.1) | 172 (50.1) | 196 (50.3) |

| Weight categorization | |||||

| Obese | 53 (33.5) | 39 (16.8) | 20 (42.6) | 72 (21.0) | 92 (23.6) |

| Overweight | 19 (12.0) | 35 (15.1) | 8 (17.0) | 46 (13.4) | 54 (13.8) |

| Healthy weight | 86 (54.4) | 158 (68.1) | 19 (40.4) | 225 (65.6) | 255 (62.6) |

| Endocrine disorders | |||||

| Adrenal insufficiency | 10 (6.3) | 2 (0.9) | 6 (12.8) | 6 (1.7) | 12 (3.1) |

| Hypothyroidism | 11 (7.0) | 2 (0.9) | 8 (17.0) | 5 (1.5) | 13 (3.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (10.1) | 2 (0.9) | 10 (21.3) | 8 (2.3) | 18 (4.6) |

Table 2.

Binary logistic regression for inpatient admission

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | ORadj | 95% lower CI | 95% upper CI | p value | ORadj | 95% lower CI | 95% upper CI | |||

| Age | 0.664 | 1.001 | 0.998 | 1.003 | ||||||

| Area deprivation index | <0.001 | 1.021 | 1.012 | 1.029 | <0.001 | 1.018 | 1.009 | 1.028 | ||

| Sex | 0.592 | 0.895 | 0.597 | 1.342 | ||||||

| Obesity | <0.001 | 2.498 | 1.55 | 4.024 | 0.005 | 2.102 | 1.249 | 3.540 | ||

| Overweight | 0.391 | 0.769 | 0.423 | 1.401 | 0.678 | 0.867 | 0.442 | 1.700 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.001 | 12.958 | 2.936 | 57.195 | 0.004 | 8.959 | 1.984 | 40.466 | ||

| Adrenal insufficiency | 0.009 | 7.77 | 1.679 | 35.962 | 0.060 | 4.754 | 0.939 | 24.070 | ||

| Hypothyroidism | 0.006 | 8.605 | 1.881 | 39.377 | 0.018 | 6.921 | 1.396 | 34.307 | ||

ORadj, adjusted odds ratios.

Fig. 2.

ORadj for inpatient admissions. Odds ratios were calculated for endocrine disorders and other factors with clinical significance. ORadj (95% CI); ORadj, adjusted odds ratios.

Table 3.

Binary logistic regression for PICU admission

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | ORadj | 95% lower CI |

95% upper CI |

p value | ORadj | 95% lower CI |

95% upper CI |

|

| Age | 0.012 | 1.005 | 1.001 | 1.009 | 0.295 | 1.002 | 0.998 | 1.007 |

| Area deprivation index | 0.023 | 1.015 | 1.002 | 1.029 | 0.074 | 1.014 | 0.999 | 1.030 |

| Sex | 0.906 | 0.964 | 0.524 | 1.774 | ||||

| Obesity | 0.002 | 2.788 | 1.479 | 5.256 | 0.009 | 2.762 | 1.295 | 5.890 |

| Overweight | 0.503 | 1.324 | 0.582 | 3.012 | 0.302 | 1.692 | 0.623 | 4.597 |

| Diabetes mellitus | <0.001 | 11.318 | 4.206 | 30.451 | <0.001 | 8.227 | 2.789 | 24.271 |

| Adrenal insufficiency | <0.001 | 8.22 | 2.533 | 26.672 | 0.062 | 3.787 | 0.934 | 15.350 |

| Hypothyroidism | <0.001 | 13.867 | 4.323 | 44.477 | <0.001 | 11.077 | 3.012 | 40.740 |

ORadj, adjusted odds ratios.

Fig. 3.

ORadj for ICU admissions. Odds ratios were calculated for endocrine disorders and other factors with clinical significance. ORadj (95% CI); ORadj, adjusted odds ratios.

Discussion/Conclusion

Throughout 2020 and 2021, COVID-19 was a leading cause of death in the USA, with a high prevalence of disease in the pediatric population [1, 13]. COVID-19 hospitalization rates in adolescents increased 5-fold over the summer of 2021 with unvaccinated patients making up most admissions [14]. With this increasing number of hospitalized patients, there is an urgent need for a better understanding of predictors of disease severity to determine populations at risk that will benefit from preventative and therapeutic interventions to decrease hospitalization and mortality rates. This study supports the established association between obesity and poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, with severity of COVID-19 presentation in adults [15, 16], and it further demonstrates that pediatric patients with COVID-19 who had a preexisting diagnosis of obesity, hypothyroidism, or diabetes mellitus were more likely to have a severe clinical presentation requiring inpatient hospital admission. This association was independent of socioeconomic status. Furthermore, it demonstrates that pediatric patients with diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and obesity were more likely to require intensive care. Though prior studies have discussed the association between severe COVID-19 disease and preexisting health conditions, many were based on billing code data, and the prevalence of endocrine disorders, such as obesity and diabetes, was not representative of those in the US pediatric population [17, 18, 19]; hence, this study provides evidence that preexisting endocrinopathies are risk factors for predisposing youth to severe COVID-19.

Obesity rates in children and adolescents have been increasing over the past few decades, with a current prevalence of approximately 19.3% in the general population [18]. This trend has been driven by socioeconomic status, with obesity prevalence being higher in low-income communities [20]. The prevalence of obesity in this study population was 23.6%, which is similar to national disease rates [18]. This study confirms prior data demonstrating that obesity is a risk factor for COVID-19 disease severity [4]. Children with obesity, but not overweight, were twice as likely to be admitted to the hospital with COVID-19. However, this association was present independent of socioeconomic status/residence in areas with an increased area deprivation index, age, or sex. Similarly, increased rates of inpatient admission due to other infectious diseases, such as H1N1 and bacterial infections, have been observed among obese populations [21, 22]. Chronic inflammation and altered immunity seen in patients with obesity may explain this relationship [23]. Furthermore, this data emphasizes the importance of strategies to mitigate COVID-19 in pediatric communities with higher rates of obesity regardless of socioeconomic status.

Increased risk for comorbidities and serious infections have been documented in patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus [24]. This study confirmed findings by Kompaniyets et al. [4] that showed increased hospitalization and ICU admission rates in children with diabetes mellitus and COVID-19. This association could be attributed to poor glycemic control, given that patients with diabetes mellitus in our study had an HbA1c higher than the target HbA1c recommended by the American Diabetes Association [25]. Even though some studies have demonstrated a clear relationship between poor glycemic control and lower socioeconomic status, our study failed to demonstrate that disease severity among patients with diabetes mellitus was dependent on socioeconomic status [26, 27]. This data emphasizes the importance of identifying and applying interventions that help children and young adults with diabetes mellitus reduce their risk for severe COVID-19 disease.

There is a paucity of data related to the association of underlying hypothyroidism with COVID-19 disease severity. Two prior studies in adults concluded that hypothyroidism does not predispose patients to a higher risk of hospitalization, ICU admission, or death [28, 29]. However, this has not previously been evaluated in COVID-19 pediatric cohort studies to date. This study showed that youth with hypothyroidism and COVID-19 were 6.9 times more likely to be admitted to a hospital and 11 times more likely to require intensive care than the general population. This data suggests that preexisting thyroid disease will likely make patients more vulnerable to a more severe COVID-19 clinical presentation. The multivariate model in this study accounted for the coexistence of hypothyroidism among patients with diabetes mellitus. Therefore, this data suggests that hypothyroidism is an independent risk factor for disease severity among pediatric patients. The increased risk of inpatient and PICU admission was independent of age, sex, BMI, or SES. Because thyroid hormone regulates multiple organ systems, different mechanisms have been speculated to be involved in the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and thyroid illness [30]. Though the results from this study suggest that pediatric patients with hypothyroidism are at an increased risk of developing a more severe COVID-19 clinical presentation, it is unclear if preexisting thyroid disease increases their susceptibility to COVID-19 infection.

Patients with adrenal suppression may be at higher risk of presenting with an adrenal crisis during an acute illness, such as COVID-19 [31]. However, there is currently no clear evidence that adrenal insufficiency patients are more likely to develop a severe course of disease. A study of adult COVID-19 patients early in the pandemic did not demonstrate an association between severe disease and adrenal insufficiency [32]. An abstract presented at the Endocrine Society suggested that youth with adrenal insufficiency and COVID-19 had higher rates of mortality and a more severe clinical presentation [33]. Though our study did not support that claim, prompt stress dosing (as used by the patients in this study) is key to prevent adrenal crises during COVID-19 illness. Further studies with larger sample size are needed to better understand the potential association between history of adrenal insufficiency and COVID-19 disease severity.

Lower socioeconomic status is often associated with limited healthcare access, higher rates of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease, increased utilization of health services, and early death [34]. Likewise, lower socioeconomic status may also lead to increased exposure to COVID-19, placing much of the burden of the pandemic on the most disadvantaged communities [26]. In this study, we used ADI scores as a measure of socioeconomic status. ADI is based on census data that has been validated, allowing for an objective ranking of residence by degree of social deprivation. Patients in this study resided in neighborhoods that were more disadvantaged than the national average. Though ADI percentiles were higher in patients that were hospitalized or required intensive care, ADI was not a predictor of disease severity. This suggests that severe disease presentation is driven by BMI, diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism and not by socioeconomic status. Given the lower SES of the entire study population, findings from this study highlight the critical need for improved healthcare delivery and disease prevention strategies.

The findings in this study are subject to several limitations. As shown in Figure 1, 150 patients from the original sample were excluded from analysis for missing BMI data, admissions primarily for reasons other than COVID-19, and missing ADI scores. Though the exclusion of these patients may have limited the sample size, it prevented the overestimation of COVID-19 hospitalization rates. Endocrine disorders were present in a small number of patients, leading to wide 95% confidence intervals in multivariable analysis. However, the lower 95% confidence intervals for diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and obesity were well above 1, suggesting that our conclusions may be generalizable and that those patients are still at elevated risk for a more severe clinical COVID-19 presentation. Despite the small number of patients with endocrinopathies, diabetes mellitus, adrenal insufficiency, and hypothyroidism had slightly higher prevalence in our study than reported rates in the general population [17, 18, 19]. This may be because SLCH is a tertiary medical center, where many patients with a higher prevalence of comorbidities are transferred from regional hospitals to receive a higher level of care. In this study, few patients had coexisting multiple endocrine disorders. While the binary logistic regression analysis accounts for these co-diagnoses, further statistical analyses in this study are limited due to the small sample size of this cohort. Thus, additional studies of this subset of patients are necessary. Endocrine conditions in this study were not subclassified by etiology; therefore, specific associations between the etiology of endocrinopathies (type 1 DM vs. type 2, or central vs. primary hypothyroidism, primary vs. secondary adrenal insufficiency, etc.) and COVID-19 disease severity may have been missed. Finally, data presented in this study predates COVID-19 vaccinations in youth; therefore, associations between endocrine disorders and COVID-19 severity presented in this study may not extrapolate to a vaccinated population.

This study highlights that presence of preexisting diagnosis of hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, and obesity predisposes unvaccinated children and adolescents to a more severe clinical presentation of COVID-19. Data from this study suggest that practitioners should consider patients with these endocrinopathies for available therapeutic and preventive strategies that decrease disease progression. Further studies are needed to analyze these relationships in the vaccinated population.

Statement of Ethics

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Washington University School of Medicine and the Saint Louis Children's Hospital (SLCH) in Saint Louis, MO, USA. The study was approved by the University's Human Research Protection Office Committee, approval number 202101185. Chart review was performed on all patients less than 25 years old that had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR at St. Louis Children's Hospital between March 2020 and February 2021. Written informed consent was not required.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

Funding was obtained through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through the National Institutes of Health (<UL1 TR002345> [to <William Powderly>]). Funding was used to support the CRTC, which N.R.B.'s work was funded by.

Author Contributions

Nicholas R. Banull: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing − original draft, and writing − review & editing. Ana Maria Arbelaez: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, and writing − review & editing. Patrick J. Reich: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, data collection, validation, and writing − review & editing. Dorina Kallogeri: methodology, validation, writing − review & editing, and formal analysis. Carine Anka, Jennifer May, Hope Shimony, and Kathleen Wharton: data collection, investigation, methodology, validation, and writing − review & editing.

Data Availability Statement

Requests for de-identified data can be made by contacting the corresponding author (A.M.A.).

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the Infection Prevention Team at St. Louis Children's Hospital (Patricia Kieffer, Geoffrey Ikpeama, Emily Jacoby, and Louise Jadwisiak), for generating the COVID-19 line list for analysis.

Nicholas R. Banull and Patrick J. Reich contributed equally to the manuscript.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Children and COVID-19: state-level data report. 2021. Available from: https://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report/

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics Management strategies in children and adolescents with mild to moderate COVID-19. 2021. [updated 12/27/2021]. Available from: https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/outpatient-covid-19-management-strategies-in-children-and-adolescents/

- 3.Rawshani A, Kjölhede EA, Rawshani A, Sattar N, Eeg-Olofsson K, Adiels M, et al. Severe COVID-19 in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in Sweden: a Nationwide Retrospective Cohort Study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;4:100105. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kompaniyets L, Agathis NT, Nelson JM, Preston LE, Ko JY, Belay B, et al. Underlying medical conditions associated with severe COVID-19 illness among children. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4((6)):e2111182. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borresen SW, Klose M, Baslund B, Rasmussen AK, Hilsted L, Friis-Hansen L, et al. Adrenal insufficiency is seen in more than one-third of patients during ongoing low-dose prednisolone treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177((4)):287–95. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Styne DM, Arslanian SA, Connor EL, Farooqi IS, Murad MH, Silverstein JH, et al. Pediatric obesity-assessment, treatment, and prevention: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102((3)):709–57. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou JH, Roumiantsev S, Singh R. PediTools electronic growth chart calculators: applications in clinical care, research, and quality improvement. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22((1)):e16204. doi: 10.2196/16204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;((314)):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright CM, Parker L, Lamont D, Craft AW. Implications of childhood obesity for adult health: findings from Thousand Families Cohort Study. BMJ. 2001;323((7324)):1280–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7324.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, Must A. Association of depression and anxiety disorders with weight change in a Prospective Community-Based Study of children followed up into adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160((3)):285–91. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Must A, Anderson SE. Body mass index in children and adolescents: considerations for population-based applications. Int J Obes. 2006;30((4)):590–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible: the neighborhood atlas. N Engl J Med. 2018;378((26)):2456–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1802313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker COVID-19 continues to be a leading cause of death in the U.S. in August 2021. 2021. Available from: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/covid-19-continues-to-be-a-leading-cause-of-death-in-the-u-s-in-august-2021/

- 14.Delahoy MJ, Ujamaa D, Whitaker M, O'Halloran A, Anglin O, Burns E, et al. Hospitalizations associated with COVID-19 among children and adolescents: COVID-NET. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly. 2021;70:1255–60. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7036e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolff D, Nee S, Hickey NS, Marschollek M. Risk factors for COVID-19 severity and fatality: a structured literature review. Infection. 2021;49((1)):15–28. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01509-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pescatore JM, Sarmiento J, Hernandez-Acosta RA, Skaathun B, Quesada-Rodriguez N, Rezai K. Glycemic control is associated with lower odds of mortality and successful extubation in severe COVID-19. J Osteopath Med. 2021;122((2)):111–5. doi: 10.1515/jom-2021-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Diabetes Association Statistics about diabetes diabetes.org. 2018. Available from: https://www.diabetes.org/resources/statistics/statistics-about-diabetes.

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevalence of childhood obesity in the United States. 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html.

- 19.Hunter I, Greene SA, MacDonald TM, Morris AD. Prevalence and aetiology of hypothyroidism in the young. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83((3)):207–10. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemmingsson E. Early childhood obesity risk factors: socioeconomic adversity, family dysfunction, offspring distress, and junk food self-medication. Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7((2)):204–9. doi: 10.1007/s13679-018-0310-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alsiö Å, Nasic S, Ljungström L, Jacobsson G. Impact of obesity on outcome of severe bacterial infections. PLoS One. 2021;16((5)):e0251887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honce R, Schultz-Cherry S. Impact of obesity on influenza A virus pathogenesis, immune response, and evolution. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1071. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza'ai H, Rahmat A, Abed Y. Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13((4)):851–63. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.58928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koren D, Levitsky LL. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Rev. 2021;42((4)):167–79. doi: 10.1542/pir.2019-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Diabetes Association 13. Children and adolescents: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2020;44((Suppl 1)):S180–99. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel JA, Nielsen FBH, Badiani AA, Assi S, Unadkat VA, Patel B, et al. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Public Health. 2020;183:110–1. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassan K, Loar R, Anderson BJ, Heptulla RA. The role of socioeconomic status, depression, quality of life, and glycemic control in type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 2006;149((4)):526–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Gerwen M, Alsen M, Little C, Barlow J, Naymagon L, Tremblay D, et al. Outcomes of patients with hypothyroidism and COVID-19: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:565. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brix TH, Hegedüs L, Hallas J, Lund LC. Risk and course of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients treated for hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9((4)):197–9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duntas LH, Jonklaas J. COVID-19 and thyroid diseases: a bidirectional impact. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5((8)):bvab076. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmet A, Mokashi A, Goldbloom EB, Huot C, Jurencak R, Krishnamoorthy P, et al. Adrenal suppression from glucocorticoids: preventing an iatrogenic cause of morbidity and mortality in children. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2019;3((1)):e000569. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2019-000569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carosi G, Morelli V, Del Sindaco G, Serban AL, Cremaschi A, Frigerio S, et al. Adrenal insufficiency at the time of COVID-19: a Retrospective Study in patients referring to a tertiary center. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106((3)):e1354–61. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raisingani MG. Risk of complications in children with adrenal insufficiency and Covid-19. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5((Suppl 1)):A721. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff. 2002;21((2)):60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Requests for de-identified data can be made by contacting the corresponding author (A.M.A.).