Abstract

During endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis, the DNA binding protein GerE stimulates transcription from several promoters that are used by RNA polymerase containing ςK. GerE binds to a site on one of these promoters, cotX, that overlaps its −35 region. We tested the model that GerE interacts with ςK at the cotX promoter by seeking amino acid substitutions in ςK that interfered with GerE-dependent activation of the cotX promoter but which did not affect utilization of the ςK-dependent, GerE-independent promoter gerE. We identified two amino acid substitutions in ςK, E216K and H225Y, that decrease cotX promoter utilization but do not affect gerE promoter activity. Alanine substitutions at these positions had similar effects. We also examined the effects of the E216A and H225Y substitutions in ςK on transcription in vitro. We found that these substitutions specifically reduced utilization of the cotX promoter. These and other results suggest that the amino acid residues at positions 216 and 225 are required for GerE-dependent cotX promoter activity, that the histidine at position 225 of ςK may interact with GerE at the cotX promoter, and that this interaction may facilitate the initial binding of ςK RNA polymerase to the cotX promoter. We also found that the alanine substitutions at positions 216 and 225 of ςK had no effect on utilization of the GerE-dependent promoter cotD, which contains GerE binding sites that do not overlap with its −35 region.

When its nutrients are depleted, the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis undergoes a morphologically and genetically complex differentiation process that culminates in the production of an endospore (18, 51). Early during this differentiation, the cell divides asymmetrically, creating a larger compartment called the mother cell and a smaller forespore compartment. These two cell types follow different developmental paths, exhibiting different patterns of gene expression (18, 38, 51). These patterns of gene expression are determined by the successive appearance of secondary sigma factors, which direct RNA polymerase to different sets of promoters (18, 41). Additional DNA binding proteins further regulate transcription by RNA polymerase containing these sigma factors.

The product of this differentiation process, the endospore, is encased in a proteinaceous coat which confers resistance to a number of environmental insults (2). The genes encoding most of these spore coat proteins are transcribed in the mother cell compartment, and their gene products are deposited around the forespore (1, 16, 18, 38, 41). Gene expression in the mother cell compartment consists of four temporally expressed gene sets (55). Specific members of each temporal set regulate expression of genes in subsequent gene sets. ςE is the first sigma factor active in the mother cell, and it directs the expression of the first gene set, which includes the gene encoding the DNA binding protein SpoIIID (5, 16, 31, 43). SpoIIID, in conjunction with ςE, activates transcription of the next set of genes which includes sigK, the gene that encodes ςK, the second and final sigma factor active in the mother cell (19, 29, 33, 47). RNA polymerase containing ςK transcribes the third gene set, which includes several spore coat genes and the gene encoding the DNA binding protein GerE (10, 11, 46, 52, 55). The fourth set of genes includes additional spore coat genes, and their expression is dependent on both ςK RNA polymerase and GerE (15, 24, 44, 45, 52–55).

GerE is an 8.5-kDa DNA binding protein which can act both as an activator and as a repressor of transcription (3, 13, 20, 22, 24, 44–46, 53–55). The work in this study focuses on its positive regulatory effects. It is not known how GerE stimulates promoter activity, but one possibility is the direct interaction of GerE with one or more subunits of RNA polymerase. Transcriptional activators in bacteria can be divided into two groups, based on the location of their binding sites in the promoter regions of the genes they are activating (23, 26). Class I activators bind to sites that are upstream from the −35 region of promoters, and several have been shown to contact the C-terminal domain of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase (8, 17, 25, 26, 40). Class II factors bind to sites that overlap the −35 region. There is evidence that class II factors may interact with the sigma subunit or with the N terminus of the alpha subunit (4, 6, 7, 30, 37, 39, 42, 48). The location of GerE binding sites differs among the promoters that are stimulated by GerE. In some instances the sites overlap the −35 region of the promoter; in others, the sites are further upstream from the transcriptional start site (24, 53, 54). Therefore, it is possible that GerE makes different contacts with RNA polymerase, depending on which promoter it is affecting.

Two GerE binding sites are present in the cotX promoter, centered at −36.5 and −60.5 with respect to the transcription start site (53). Because the region protected by GerE from DNase I digestion extends into the −35 region, we hypothesized that GerE contacts ςK at this promoter. If GerE stimulation of cotX promoter activity requires the interaction of GerE with ςK, then it may be possible to identify amino acid substitutions in ςK that interfere with its interaction with GerE but have little effect on the activity of ςK RNA polymerase on promoters at which interaction between ςK and GerE is not required. Here, we identify two amino acid residues of ςK that are required for the efficient utilization of the cotX promoter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

EUKW9711 was constructed for the purification of RNA polymerase containing ςK. Strain AH45, a JH642 derivative with a spoIIIG in-frame deletion, was transformed with chromosomal DNA from a bofA::cat mutant to create EUKW9710. EUKW9711 was constructed by transforming EUKW9710 with pPolHis1, creating a His tag on the C terminus of the β′ subunit. The remaining B. subtilis strains used in this study are listed in Table 1 or described in the text. Escherichia coli DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories) or One Shot cells (Invitrogen) were used for routine molecular cloning work, and BL21(λDE3)pLysS (Stratagene) was used for overexpression of the GerE protein.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Strain | Derivation or genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| JH642 | trpC2 pheA1 | J. Hoch |

| MO1100 | JH642 sigK | R. Losick |

| VO558 | MO1100 gerE36 | R. Losick |

| SR276 | MO1100 sigK::neo | R. Losick |

| ZB307A | SPβc2del2::Tn917::pSK10Δ6 | P. Zuber |

| EUKW9612 | MO1100 transformed with pKW10 and lysogenized with SPβ cotX-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9613 | EUKW9612 sigK-E216K | This work |

| EUKW9614 | EUKW9612 sigK-F224L/H225Y | This work |

| EUKW9615 | MO1100 transformed with pE216K | This work |

| EUKW9616 | EUKW9615 SPβcotX-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9617 | EUKW9615 SPβgerE-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9618 | EUKW9615 SPβcotD-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9619 | MO1100 transformed with pE216A | This work |

| EUKW9620 | EUKW9619 SPβcotX-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9621 | EUKW9619 SPβgerE-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9622 | EUKW9619 SPβcotD-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9623 | MO1100 transformed with pF224L | This work |

| EUKW9624 | MO1100 transformed with pH225Y | This work |

| EUKW9625 | EUKW9623 SPβcotX-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9626 | EUKW9623 SPβgerE-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9627 | EUKW9623 SPβcotD-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9628 | EUKW9624 SPβcotX-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9629 | EUKW9624 SPβgerE-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9630 | EUKW9624 SPβcotD-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9701 | MO1100 transformed with pF224A | This work |

| EUKW9702 | MO1100 transformed with pH225A | This work |

| EUKW9703 | EUKW9702 SPβcotX-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9704 | EUKW9702 SPβgerE-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9705 | EUKW9702 SPβcotD-lacZ | This work |

| EUKW9711 | trpC2 spoIIIGΔ bofA::cat; pPolHis1 | This work |

| EUKW9812 | EUKW9711 transformed with pE216A | This work |

| EUKW9811 | EUKW9711 transformed with pH225Y | This work |

pKH2, a derivative of pSR134, was constructed to be a template for random mutagenesis of sigK, the gene encoding ςK. pSR134 is a derivative of pSK5 (32) that contains an additional 850 bp flanking downstream chromosomal sequences. A HindIII fragment containing the tetracycline resistance cassette from pBEST309 (27) was cloned into the HindIII site approximately 560 bp downstream of sigK, creating pKH2. pGerE-EX was constructed by Jim Brannigan to be used for the expression of GerE by replacing the NdeI-BamHI fragment of pET-26b(+) (Novagen) with a 240-bp NdeI-BamHI fragment containing the gerE gene, thus placing gerE under the control of a T7 promoter. The pPolHis1 plasmid was designed to place a His tag at the 3′ terminus of the rpoC gene, which encodes the β′ subunit of the B. subtilis RNA polymerase. When used to transform B. subtilis, this plasmid integrates by a single homologous recombination event at the rpoC locus. First, a 1.2-kb spectinomycin resistance cassette (34), extracted by BamHI and BglII digestion from pAH256 (20), was inserted at the BglII site of pET-21b (Novagen). The orientation of the spectinomycin resistance cassette was determined to be toward the bla gene of the vector. Then, the spectinomycin resistance cassette was reversed by cutting the recombinant plasmid with PstI and subsequent ligation. The desired orientation, toward the lacI gene of the vector, was confirmed by cleavage with EcoRI. Finally, a Pfu polymerase-amplified product encoding a 1,026-bp-long C-terminal part of β′ was obtained by using the BSBETA′-F and BSBETA′-R primers (Table 2). This product was inserted between the NdeI and SacI sites of the intermediate plasmid, creating an in-frame hexaHis extension to the carboxy-terminal part of β′. The accuracy of the junction was determined by sequencing. The resultant plasmid is pPolHis1, and DH5α with this plasmid (strain ECE120) is available from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center (Ohio State University). pKW21 was constructed to be a template for in vitro transcription by inserting into pCR2.1-TOPO a 413-bp region of the gerE promoter that was amplified by using the GER-676F and GERE-1088R primers (Table 2). The accuracy of all cloning was confirmed by sequencing by using Sequenase version 2.0 (Amersham).

TABLE 2.

Primers

| Primer | Sequence 5′ to 3′ |

|---|---|

| BSBETA′-F | ATTTCATATGCGCTTAGAACGCTTA |

| BSBETA′-R | CCGCGAGCTCGATGCTTCAACCGGGACCATATCG |

| GER-676F | AACAAACTGATCATGACAGTCG |

| GERE-1088R | TCGTTAGCGACGGCTTCGA |

| COTX-H3 | CGTGTTTTTCTTAAGCTTTCTC |

| COTX-BCLI | GAGCAGCTCATTGAACTGATCA |

| SIGK2 | GGATGCAGAGGACTTAATCTCC |

| SRSIGK3′ | TATCACGAGGCCCTTTCGTC |

| E216K-FOR | ATCAGCGCCCGCTTTTTAATCC |

| E216K-REV | GTATCGCGGATTAAAAAGCGGG |

| E216A-FOR | GCTATGTATCGCGGATTGCAAAGCGGGCGC |

| E216A-REV | GCGCCCGCTTTGCAATCCGCGATACATAGC |

| H225Y-FOR | GCTGATGAAGATGTTTTATGAGTTTTATCG |

| H225Y-REV | CGATAAAACTCATAAAACATCTTCATCAGC |

| H225A-FOR | GCTGATGAAGATGTTTGCTGAGTTTTATCG |

| H225A-REV | CGATAAAACTCAGCAAACATCTTCATCAGC |

Construction of promoter fusions.

A 237-bp PCR fragment of the cotX promoter region was amplified with COTX-H3 and COTX-BCLI (Table 2) by Pfu polymerase and inserted into pTKlac (28), replacing a HindIII-BamHI fragment and creating a promoter fusion to the lacZ gene. This plasmid was linearized by digestion with PstI and transformed into B. subtilis ZB307A, creating an SPβ specialized transducing phage carrying the cotX-lacZ promoter fusion. A phage lysate was prepared by heat induction.

A 413-bp PCR fragment containing the gerE promoter region (as described above for pKW21) was cloned into pMLK83 (21), replacing a HindIII-BamHI fragment and creating a promoter fusion to the gusA gene. This plasmid, pKW10, was linearized by digestion with PstI and introduced into the B. subtilis chromosome by transformation with selection for the linked neomycin resistance cassette at 3 μg/ml. Disruption of the amyE locus was confirmed by amylase-deficient phenotype on Luria-Bertani (LB) plates containing 1% starch (12).

Random PCR mutagenesis.

Random mutations were introduced into the C-terminal two-thirds of the sigK gene by PCR (35). The template DNA used was pKH2, and the primers used for amplification (SIGK2 and SRSIGK3′) were within region 2.2 of ςK or within the vector sequences (Table 2). The sigK gene, flanking chromosomal DNA, and the tetracycline resistance marker were amplified under standard PCR conditions, with the exception of the addition of MnCl2 to a final concentration of 0.1 to 0.25 mM. The reaction mixture differed from that described in the protocol of Leung et al. (35) by the omission of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and β-mercaptoethanol, and nucleotide ratios were not altered.

Screening of potential mutants.

Tetr transformants were patched onto Difco sporulation medium (DSM) plates containing either X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside; the substrate for the cotX-lacZ fusion) or X-Gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronic acid; the substrate for the gerE-gusA fusion). Colonies that were white on the X-Gal plates and blue on the X-Gluc plates were selected for further analysis. The frequency of cotransformation of the mutant phenotype with Tetr marker was determined to be 88 to 90% by patching 100 Tetr transformants each on DSM plates with X-Gal or X-Gluc.

Site-directed PCR mutagenesis.

Site-specific changes were made in sigK by using the QuickChange kit from Stratagene (creating pE216K, pE216A, pF224L, pF224A, pH225Y, and pH225A). pKH2 was the DNA template, and primers used for the mutagenesis were complementary and divergent 30-bp oligonucleotides with the mutations located in the center of the sequences (Table 2). The DNA polymerase used in the reactions was the high-fidelity Pfu enzyme from Stratagene. The presence of the mutations was confirmed by sequencing the sigK gene of each plasmid.

Sporulation assay.

The B. subtilis strains were grown for 24 h in DSM liquid. Samples from each culture (1 ml) were heated at 80°C for 10 min. The number of CFU in both heated and unheated samples was determined by plating cells diluted by 10−2, 10−4, and 10−6 onto LB medium containing tetracycline (7.5 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml).

Purification of RNA polymerases.

Strains EUKW9711, EUKW9811, and EUKW9812 were grown for 7.5 h after the onset of sporulation in 1 liter of DSM containing chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml) and spectinomycin (50 μg/ml). The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 10 ml of buffer 1 (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) containing 2.5 mM imidazole. Cells were disrupted by two passages through a French pressure cell at 70,000 kPa and pelleted by centrifugation for 20 min at 4°C and 12,000 × g. Proteins from the supernatant were adsorbed at 4°C to 4 ml of a Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) superflow matrix (Qiagen) previously equilibrated with buffer 1 containing 2.5 mM imidazole. After at least 1 h, the resin was packed into a disposable column and washed with 15 ml of buffer 1 containing 20 mM imidazole. The His-tagged RNA polymerase was eluted from the column with buffer 1 containing 300 mM imidazole. The fractions eluted from the column were tested for RNA polymerase activity in a nonspecific activity assay as previously described (49). The amount of active ςK RNA polymerase in each preparation was determined and normalized by its activity on the GerE-independent, ςK-dependent promoter gerE in run-off transcription assays.

Partial purification of GerE.

BL21(λDE3)pLysS cells containing pGerE-EX were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 0.7 in LB medium containing chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml) and kanamycin (30 μg/ml), at which time expression of GerE was induced by the addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The cells were grown for an additional 2.5 h at 37°C. The harvested cells were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 20% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.3 mg of PMSF. Cells were lysed at 4°C by a single passage through a French pressure cell at 70,000 kPa and centrifuged for 20 min at 4°C and 31,000 × g. Proteins from the supernatant were loaded onto a 1-ml Hi-Trap heparin column (Pharmacia) and eluted by a gradient from 100 to 500 mM NaCl by using a Pharmacia fast-protein liquid chromatography system. Fractions were electrophoresed on an 18% polyacrylamide gel to determine which fractions contained GerE. Fractions containing the majority of GerE protein were combined and dialyzed against 1 liter of storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 20% glycerol, and 1 mM EDTA) for 4 h at 4°C. Aliquots were stored at −80°C.

In vitro transcription.

Plasmids pJZ6 (52) digested with BglII and pKW21 digested with EcoRI were used as templates for in vitro transcription reactions. Both templates, GerE, and RNA polymerase containing either wild-type or mutant ςK were preincubated for 10 min at 37°C in a 40-μl volume with a final concentration of 33 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.9), 10 mM magnesium acetate, 0.5 mM DTT, and 0.15 mg of bovine serum albumin. Ribonucleotides (500 μM final concentration of ATP, CTP, and GTP [Boehringer Mannheim] and 2 μCi of [α-32P]UTP [400 Ci/mmol; Amersham]) were added for 1 min before reinitiation was prevented by the addition of 10 μg of heparin (Sigma). Five minutes later, unlabelled UTP (500 μM final concentration) (Boehringer Mannheim) was added for an additional 5-min incubation. Reactions were stopped by the addition of sodium acetate (0.3 M final concentration) and ethanol precipitation of nucleic acids. Before being loaded on a 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea sequencing gel, nucleic acids were resuspended in 10 μl of a urea sequencing dye. Transcripts were quantitated by densitometry with the ImageQuant software coupled to a PhosphorImager 445 SI (Molecular Dynamics). Specific transcription from the cotX and gerE promoters produced nucleotide transcripts of 183 and 107 bp, respectively.

RESULTS

Mutant sigK alleles that reduce cotX expression but not gerE expression.

We sought to identify mutations in sigK that specifically decreased cotX promoter activity while having no effect on the activity of the ςK-dependent, GerE-independent promoter, gerE. The gene encoding ςK consists of two gene fragments, spoIVCB and spoIIIC, that are separated by a 42-kb region of DNA called the skin element (50). The skin element sequences are deleted during sporulation from the mother cell chromosome by a site-specific recombination event to create an intact sigK gene (32). Cells engineered to have a skinless sigK were shown to follow normal timing for sporulation (32). For the purpose of easier manipulation of the gene and introduction of mutations into the chromosome, all strains and plasmids used in this study contain the skinless sigK.

A series of random mutations in sigK were generated by PCR mutagenesis of a 3.9-kb region of pKH2 that included sigK, flanking chromosomal DNA, and the tetracycline resistance cassette. The mutations were introduced into the bacterial chromosome by transformation of B. subtilis EUKW9612 to tetracycline resistance with purified PCR products (Fig. 1). EUKW9612 contained two reporter fusions, a cotX-lacZ and gerE-gusA. The cotX fusion served as the GerE-dependent fusion, while gerE promoter activity was not dependent on GerE (10, 53). Tetracycline-resistant transformants were patched onto DSM plates containing either X-Gal or X-Gluc, and colonies that were white on the X-Gal plates, indicating that these strains had decreased cotX activity, were selected for further analysis. From these we chose colonies that were blue on X-Gluc, indicating that these strains are still capable of GerE-independent, ςK-dependent transcription. Furthermore, to avoid isolation of mutations that decreased expression from many ςK-dependent promoters, we eliminated the strains that were sporulation deficient (Spo−); that is, strains that did not form heat-resistant spores as determined by heat tests. We screened over 3,400 tetracycline-resistant transformants and identified six strains that were Spo+ and deficient in cotX activation, two of which did not decrease transcription from the gerE promoter.

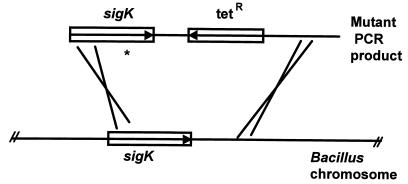

FIG. 1.

Introduction of sigma mutations into the B. subtilis chromosome. B. subtilis EUKW9612 was transformed to tetracycline resistance with purified mutagenized PCR products (14). The chromosomal copy of sigK was replaced with the mutant copy by recombination within regions of homology. The asterisk denotes a mutation.

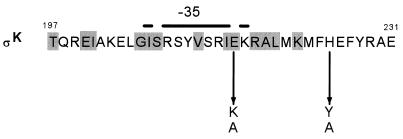

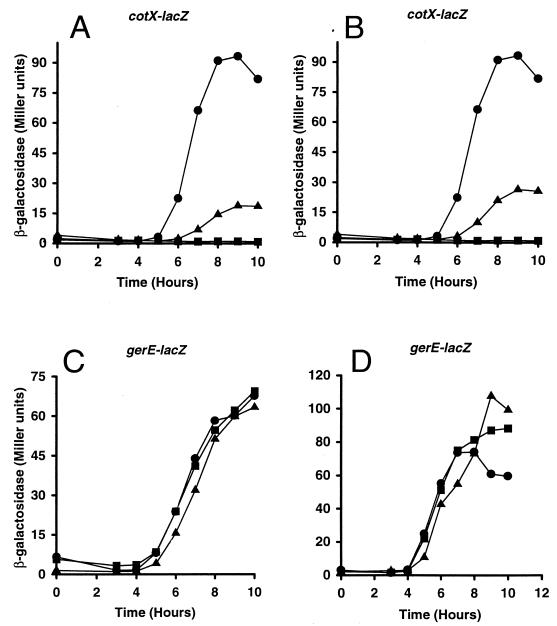

The phenotype of these two strains was shown by transformation to be linked to the tetracycline resistance marker (see Materials and Methods). We then determined the nucleotide sequence of the sigK gene from the chromosome of the two mutant strains and identified mutations that encoded a single-amino-acid substitution in one strain (EUKW9613) and two-amino-acid substitutions in adjacent residues in the other strain (EUKW9614). The mutation in EUKW9613 resulted in a glutamate-to-lysine substitution at position 216 in ςK (E216K), and the mutations in EUKW9614 resulted in a phenylalanine-to-leucine change at position 224 and a histidine-to-tyrosine substitution at position 225 (F224L/H225Y) (Fig. 2). Both mutant strains produced wild-type numbers of heat-resistant spores (Table 3). Since the mutations in strain EUKW9614 resulted in two amino acid substitutions, we used site-directed mutagenesis to isolate strains containing each of the single-amino-acid substitutions. We also reconstructed the mutation at position 216, using site-directed mutagenesis. These three strains were transduced with a specialized transducing phage SPβ that carried either the cotX-lacZ or the gerE-lacZ promoter fusion, and β-galactosidase accumulation in the cultures was monitored throughout sporulation (Fig. 3). We found that both the H225Y and the E216K substitutions reduced expression from the cotX promoter but that neither affected expression from the gerE promoter. The F224L substitution had no effect on cotX or gerE promoter activity (data not shown). From these data, we conclude that the single-amino-acid substitutions at position 216 and 225 specifically decrease the activation of the GerE-dependent promoter cotX.

FIG. 2.

Amino acid substitutions in ςK that affect cotX activation. The amino acid sequence of the C terminus of ςK is shown with the position numbers of the first and last amino acids. Shaded boxes indicate residues that are conserved among sigma factors in the ς70 family, and the bar above the sequence denotes the region of sigma factors responsible for recognition of the −35 region of promoters. The single-amino-acid substitutions that specifically reduced cotX expression are depicted by an arrow from the original amino acid residue to the substitution.

TABLE 3.

Sporulation assay

| Strain | No. of viable cells/ml | No. of heat-resistant spores/ml |

|---|---|---|

| MO1100 (wild-type sigK) | 5.5 × 108 | 3.4 × 108 |

| VO558 (gerE36) | 3.0 × 108 | 3.2 × 108 |

| SR276 (sigK::neo) | 5.0 × 108 | 40 |

| EUKW9613 (sigK-E216K) | 5.5 × 108 | 3.9 × 108 |

| EUKW9614 (sigK-F224L/H225Y) | 3.0 × 108 | 2.5 × 108 |

FIG. 3.

Effects of amino acid substitutions in ςK on transcription from the cotX and gerE promoters. B. subtilis MO1100 (wild type) (circles), VO558 (gerE36) (squares), and sigK mutant strains (triangles) containing promoter-lacZ fusions (cotX in panels A and B and gerE in panels C and D) were grown in DSM liquid medium. The mutant strains are EUKW9616 (ςK-E216K) (A), EUKW9628 (ςK-H225Y) (B), EUKW9617 (ςK-E216K) (C), and EUKW9629 (ςK-H225Y) (D). Samples were taken at the onset of stationary phase or sporulation (T0) and at 1-h intervals thereafter (T3 to T11) and assayed for β-galactosidase accumulation. Two independent transductants for each of the above-mentioned strains were assayed for β-galactosidase activity, and the averages are shown.

An alanine substitution at position 216 or 225 in ςK reduces cotX transcription but not gerE transcription.

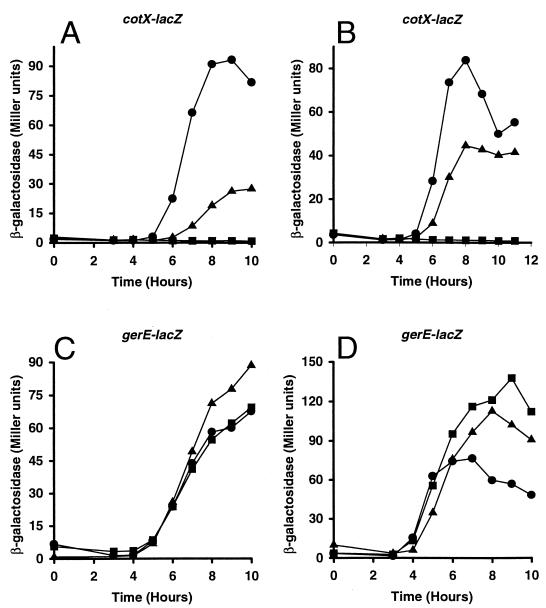

Since cotX promoter activity requires GerE, whereas gerE promoter activity does not, it seems likely that the E216K and H225Y substitutions in ςK interfere with its interaction with GerE. To test whether E216 and H225 in ςK are required for cotX promoter utilization, we introduced alanine substitutions at these positions, creating strains EUKW9619 and EUKW9702 (Fig. 2), respectively, and examined the effect of the mutations on promoter utilization in vivo. Alanine substitutions were chosen in order to replace the original amino acid residues without introducing large side chains with different charges. These strains were transduced with a specialized transducing phage SPβ that carried either the cotX-lacZ or the gerE-lacZ promoter fusion, and β-galactosidase accumulation in the cultures was monitored throughout sporulation (Fig. 4). The E216A mutation reduced the peak of cotX activation to 32% of the wild-type peak activity (Fig. 4A), whereas the H225A mutation reduced peak expression to 55% of wild-type peak activity (Fig. 4B). Expression of gerE-lacZ was higher in both mutant strains than in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4C and D). These data correlate well with the results obtained with the original mutations and support the notion that the amino acid residues at positions 216 and 225 of ςK play a role in the utilization of the GerE-dependent promoter cotX.

FIG. 4.

Effect of alanine substitutions in ςK on transcription from the cotX and gerE promoters. B. subtilis MO1100 (wild type) (circles), VO558 (gerE36) (squares), and sigK mutant strains (triangles) containing promoter-lacZ fusions (cotX in panels A and B and gerE in panels C and D) were grown in DSM liquid medium. The mutant strains are EUKW9620 (ςK-E216A) (A), EUKW9703 (ςK-H225A) (B), EUKW9621 (ςK-E216A) (C), and EUKW9704 (ςK-H225A) (D). Samples were taken at the onset of stationary phase or sporulation (T0) and at 1-h intervals thereafter (T3 to T11) and assayed for β-galactosidase accumulation. Two independent transductants for each of the above-mentioned strains were assayed for β-galactosidase activity, and the averages are shown.

RNA polymerases containing ςK-E216A or ςK-H225Y have reduced transcription from the cotX promoter in vitro.

In order to eliminate the possibility that the reduction in cotX expression in strains containing the substitutions in ςK was the result of some unknown indirect effect of the ςK mutations on the physiology of the cell, we examined the effects of two of these mutations in vitro with run-off transcription assays (Fig. 5 and 6). We isolated ςK RNA polymerase from EUKW9711 (wild-type ςK), EUKW9812 (E216A ςK), and EUKW9811 (H225Y ςK) cultures that were induced to sporulate. Cells were harvested approximately 7.5 h after the onset of sporulation, the time at which ςK is active. To ensure that we were isolating predominantly ςK RNA polymerase, these strains contain a mutation in spoIIIG, the gene that encodes the late forespore-specific ςG factor. The bofA::cat mutation is also present to bypass the forespore-specific signal that is normally required for ςK activation (9).

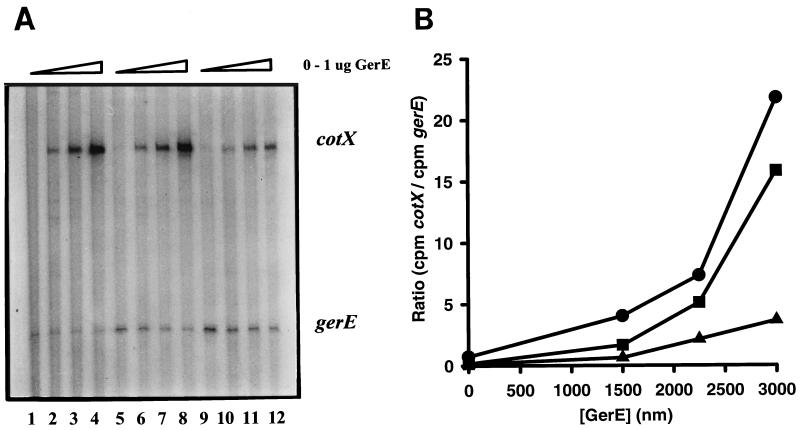

FIG. 5.

Comparison of cotX activation in vitro by wild-type and mutant ςK RNA polymerases. (A) An autoradiograph of radiolabelled transcripts that were subjected to electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide gel is shown. DNA templates (1.5 μg of each template) were incubated with ςK RNA polymerase alone (lanes 1, 5, and 9) or with 0.25 μg (lanes 2, 6, and 10), 0.5 μg (lanes 3, 7, and 11), or 1 μg (lanes 4, 8, and 12) of partially purified GerE. Lanes 1 to 4, 5 to 8, and 9 to 12 contain RNA polymerase purified from EUKW9711 (wild type), EUKW9812 (ςK-E216A), and EUKW9811 (ςK-H225Y), respectively. The positions of run-off transcripts of the expected sizes, as judged by the migration of end-labeled 50-bp DNA ladder (Pharmacia), are indicated. (B) Quantification of the data shown in panel A. The cotX signal is standardized by division with the gerE signal from the same lane; the ratio is plotted against the concentration of GerE in the reaction mixture. EUKW9711 (circles), EUKW9812 (squares), and EUKW9811 (triangles).

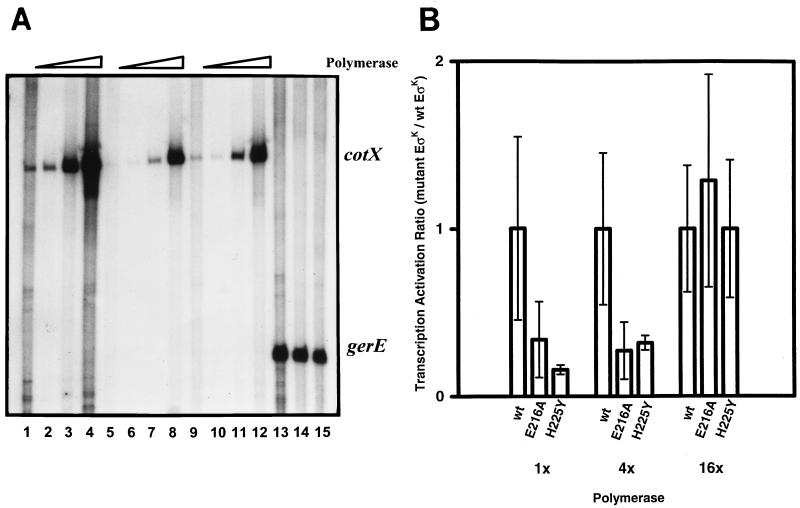

FIG. 6.

In vitro transcription with limiting amounts of ςK polymerase. (A) An autoradiograph of radiolabelled transcripts that were subjected to electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide gel is shown. One microgram of DNA template (pJZ6 for lanes 1 to 12 or pKW21 for lanes 13 to 15) was incubated with ςK RNA polymerase alone (lanes 1, 5, and 9) or with 0.5 μg of GerE (lanes 2 to 4, 6 to 8, and 10 to 12). Lanes 1 to 4, 5 to 8, and 9 to 12 contain RNA polymerase purified from EUKW9711 (wild type), EUKW9812 (ςK-E216A), and EUKW9811 (ςK-H225Y), respectively. Half of the amounts of RNA polymerase used in Fig. 5 was added in lanes 1, 4, 5, 8, and 9 and 12 to 15. One-eighth of the amounts was added in lanes 3, 7, and 11. A 1/32 fraction of the amounts was added in lanes 2, 6, and 10. The positions of run-off transcripts of the expected sizes, as judged by the migration of end-labeled 50-bp DNA ladder (Pharmacia), are indicated. (B) Quantification of the data shown in panel A. Data are represented as the amount of cotX signal made with RNA polymerase containing mutant ςK normalized against the gerE signal generated by using the equivalent amount of polymerase, divided by the equivalent expression for wild-type (wt) ςK. The ratio is plotted against the amount of polymerase in the reaction mixture. Error bars show the standard deviations for three independent experiments. EUKW9711 (wild type), EUKW9812 (E216A), and EUKW9811 (H225Y).

In vitro transcription reactions were carried out by coincubating the GerE-dependent cotX promoter or the GerE-independent gerE promoter with mutant or wild-type RNA polymerase holoenzyme and GerE protein in two types of experiments. In the first type of experiment, various concentrations of partially purified GerE protein (0 to 3,000 nM) were added to the reactions that contained two DNA templates, the cotX promoter and the gerE promoter. These results showed that addition of GerE to reactions containing wild-type ςK-RNA polymerase resulted in increased transcription from the cotX promoter, while transcription from the GerE-independent promoter gerE decreased (Fig. 5). This reduction of gerE transcription was probably caused by competition with the cotX promoter for ςK-RNA polymerase. This GerE-dependent repression of gerE transcription was not observed in reaction mixtures that contained only the gerE promoter template (data not shown). The addition of GerE to reaction mixtures containing the mutant ςK-E216A RNA polymerase also stimulated cotX transcription almost as efficiently as was seen with the wild-type ςK RNA polymerase (Fig. 5). In contrast, the addition of GerE to reaction mixtures containing the mutant ςK-H225Y RNA polymerase stimulated cotX transcription less efficiently than observed with wild-type ςK RNA polymerase (Fig. 5).

In the second type of experiment, a constant concentration of GerE was added to reactions containing various concentrations of wild-type or mutant RNA polymerase. In these reactions, the concentration of ςK RNA polymerase was lower than the concentration of DNA template; therefore, only a single promoter DNA template was added to eliminate competition of the promoters for ςK RNA polymerase. The results of these experiments (Fig. 6) showed that at low ςK RNA polymerase concentrations, the mutant ςK polymerases used the cotX promoter less efficiently than the wild-type form of ςK RNA polymerase. Because the effects of the ςK mutations were less severe at high polymerase concentrations (Fig. 6B), these mutations may affect the initial binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter—formation of the closed complex. Although we have not done extensive kinetic analysis of cotX promoter activation, we suggest that GerE acts, at least in part, to stimulate initial binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter. Regardless of which step in cotX promoter utilization is stimulated by GerE, the E216A and H225Y substitutions in ςK directly reduced the utilization of the cotX promoter. The H225Y substitution had the greater effect on the GerE-dependent utilization of the cotX promoter.

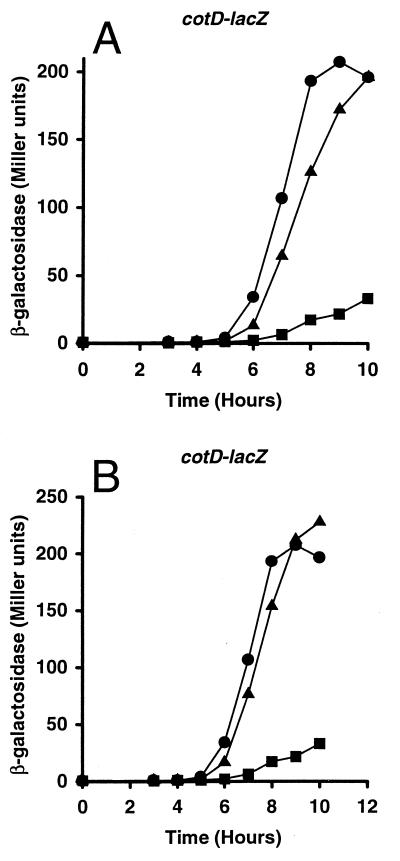

E216 and H225 of ςK are not required for cotD promoter activity.

GerE also stimulates the activity of the cotD promoter (24, 54, 55). In this case GerE binds to sites centered at −25.5 and −47.5 (24); therefore, GerE may interact with a different surface of the ςK RNA polymerase than the surface required for stimulation of cotX promoter activity. To determine whether positions 216 and 225 in ςK are required for GerE stimulation of cotD promoter activity, we transduced strains containing the mutant sigK alleles with an SPβ phage that carried the cotD-lacZ promoter fusion. We assessed the effect of the alanine substitutions on cotD promoter utilization by monitoring β-galactosidase accumulation in the cultures during sporulation (Fig. 7). In contrast to their effect on cotX promoter activity (Fig. 4A and B), the E216A and H225A substitutions in ςK had little effect on cotD promoter activity (Fig. 7). Evidently, E216 and H225 in ςK are not necessary for cotD promoter activity. Therefore if, as argued below, H225 of ςK is a site required for interaction with GerE at the cotX promoter, GerE may stimulate cotD promoter activity by a different interaction with ςK RNA polymerase.

FIG. 7.

Effect of alanine substitutions in sigK on transcription from the cotD promoter. B. subtilis MO1100 (wild type) (circles), VO558 (gerE36) (squares), and mutant strains (triangles) containing cotD-lacZ were grown in DSM liquid medium. The mutant strains are EUKW9622 (E216A) (A) and EUKW9705 (H225A) (B). Samples were taken at the onset of stationary phase or sporulation (T0) and at 1-h intervals thereafter (T3 to T10) and assayed for β-galactosidase accumulation. Two independent transductants for each of the above-mentioned strains were assayed for β-galactosidase activity, and the averages are shown.

DISCUSSION

We have found that amino acid substitutions at positions 216 and 225 in ςK decrease cotX promoter activation without affecting expression from the gerE promoter. Both the originally isolated substitutions and the alanine substitutions at these positions have similar effects; therefore, it seems unlikely that all of these substitutions change the specificity of promoter recognition such that the mutant sigmas could not interact with cotX promoter DNA but were able to interact productively with gerE promoter DNA. Because the alanine substitutions reduce cotX promoter activity, we infer that the side chains of the lysine substituted at position 216 and the tyrosine substituted at position 225 were not interfering with activation but, rather, that E216 and H225 of ςK are required for maximum cotX promoter activity. In vitro transcription results show that the decrease in cotX promoter activity is not a result of some unknown change in the physiology of the cell. In addition, the substitutions at positions 216 and 225 in ςK do not grossly alter the structure of ςK, because the mutant polymerases were still able to use the gerE promoter in vitro. RNA polymerase containing the E216A-substituted ςK was stimulated efficiently in vitro by GerE to use the cotX promoter, but its activity on the gerE promoter in the absence of GerE was lower than that of wild-type polymerase. Therefore, the E216A substitution may have affected interaction of ςK with cotX promoter DNA. In contrast, GerE stimulated use of the cotX promoter in vitro by RNA polymerase containing the H225Y-substituted ςK less efficiently than by wild-type ςK RNA polymerase. Therefore, H225 in ςK is probably involved in a ςK-GerE interaction at the cotX promoter. We believe that it is unlikely, but we cannot eliminate the possibility that H225 is also involved in an interaction with cotX promoter DNA.

We suggest that interaction of GerE with the region of ςK near position 225 is important for cotX promoter activity, but we do not exclude the possibility that additional interactions between GerE and RNA polymerase may also be required for stimulation of cotX promoter activity. The amino acid substitutions at positions 216 and 225 in ςK cause a decrease in cotX promoter activity but do not abolish cotX transcription completely. This raises the possibility that GerE makes more than one contact with RNA polymerase at this promoter. E. coli catabolite gene activator protein (CAP) is an example of a transcriptional activator that makes several contacts with RNA polymerase. At class II CAP-dependent promoters, CAP binds as a dimer to sequences that overlap the −35 region of the promoter. The upstream subunit of the dimer contacts the C-terminal domain of the α subunit, while the downstream subunit interacts with the N-terminal domain of the α subunit (7, 42, 56). Similarly, E. coli FNR protein also has more than one interaction with RNA polymerase when it binds as a dimer to sites that overlap the −35 region. In this case, the upstream FNR molecule interacts with the C-terminal domain of α and the downstream molecule contacts the ς70 subunit of RNA polymerase (36).

In the cotX promoter, there are two adjacent binding sites, one of which overlaps the −35 region (53). Our results support a model in which GerE activates transcription from the cotX promoter by interacting with RNA polymerase specifically through the ςK subunit. It is not clear, however, which GerE molecule is involved in this interaction, but from the studies of other activators, it would be expected to be between ςK and the GerE molecule bound to the downstream site which overlaps the −35 region. This contact may not be the only interaction between GerE and the RNA polymerase at cotX, because the mutations do not abolish cotX promoter activity. Therefore, the upstream GerE molecule may interact with the C-terminal domain of the α subunit. This additional interaction could account for the residual activity from the cotX-lacZ promoter fusion in the mutant strains. Moreover, the H225A substitution in ςK did not interfere with the activation of another promoter that is stimulated by GerE, cotD. Therefore, despite its small size, GerE appears to be capable of activating promoters in more than one way, presumably by interacting with different surfaces of ςK RNA polymerase.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Losick for encouraging us to pursue this project and, along with S. Roels, for generously providing many sigK strains and plasmids for this work. We also thank A. Aronson for the gift of plasmid pJZ6 and J. Brannigan for providing us with plasmid pGerE-EX and helpful advice on GerE purification. We gratefully acknowledge L. Kroos, R. Losick, O. Resnekov, J. Scott, and W. Shafer for important comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by grant MCB-9727722 to C.P.M. from the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe A, Koide H, Kohno T, Watabe K. A Bacillus subtilis spore coat polypeptide gene, cotS. Microbiology. 1995;141:1433–1442. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-6-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson A I, Fitz-James P. Structure and morphogenesis of the bacterial spore coat. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:360–402. doi: 10.1128/br.40.2.360-402.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagyan I, Setlow B, Setlow P. New small acid-soluble proteins unique to spores of Bacillus subtilis: identification of the coding genes and regulation and function of two of these genes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6704–6712. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6704-6712.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldus J M, Buckner C M, Moran C P., Jr Evidence that the transcriptional activator Spo0A interacts with two sigma factors in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:281–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beall B, Driks A, Losick R, Moran C P., Jr Cloning and characterization of a gene required for assembly of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1705–1716. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1705-1716.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckner C M, Moran C P. A region in Bacillus subtilis ςH required for Spo0A-dependent promoter activity. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4987–4990. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4987-4990.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busby S, Ebright R H. Transcription activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2771641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Ebright Y W, Ebright R H. Identification of the target of a transcription activator protein by protein-protein photocrosslinking. Science. 1994;265:90–92. doi: 10.1126/science.8016656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cutting S, Oke V, Driks A, Losick R, Lu S, Kroos L. A forespore checkpoint for mother cell gene expression during development in B. subtilis. Cell. 1990;62:239–250. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90362-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cutting S, Panzer S, Losick R. Regulatory studies on the promoter for a gene governing synthesis and assembly of the spore coat in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1989;207:393–404. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cutting S, Zheng L B, Losick R. Gene encoding two alkali-soluble components of the spore coat from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2915–2919. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2915-2919.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutting S M, Vander Horn P B. Genetic analysis. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1990. pp. 27–74. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel R A, Errington J. Cloning, DNA sequence, functional analysis and transcriptional regulation of the genes encoding dipicolinic acid synthetase required for sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:468–483. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decatur A L, Losick R. Three sites of contact between the Bacillus subtilis transcription factor sigmaF and its antisigma factor SpoIIAB. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2348–2358. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donovan W, Zheng L B, Sandman K, Losick R. Genes encoding spore coat polypeptides from Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Driks A, Losick R. Compartmentalized expression of a gene under the control of sporulation transcription factor sigma E in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9934–9938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.9934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebright R H. Transcription activation at Class I CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:797–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Errington J. Bacillus subtilis sporulation: regulation of gene expression and control of morphogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:1–33. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.1-33.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halberg R, Kroos L. Sporulation regulatory protein SpoIIID from Bacillus subtilis activates and represses transcription by both mother-cell-specific forms of RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:425–436. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henriques A O, Beall B W, Moran C P., Jr CotM of Bacillus subtilis, a member of the alpha-crystallin family of stress proteins, is induced during development and participates in spore outer coat formation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1887–1897. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1887-1897.1997. . (Erratum, 179:4455.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henriques A O, Beall B W, Roland K, Moran C P., Jr Characterization of cotJ, a sigma E-controlled operon affecting the polypeptide composition of the coat of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3394–3406. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3394-3406.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henriques A O, Bryan E M, Beall B W, Moran C P., Jr cse15, cse60, and csk22 are new members of mother-cell-specific sporulation regulons in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:389–398. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.389-398.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hochschild A, Dove S L. Protein-protein contacts that activate and repress prokaryotic transcription. Cell. 1998;92:597–600. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichikawa H, Halberg R, Kroos L. Negative regulation by the Bacillus subtilis GerE protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8322–8327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Igarashi K, Ishihama A. Bipartite functional map of the E. coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit: involvement of the C-terminal region in transcription activation by cAMP-CRP. Cell. 1991;65:1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90553-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishihama A. Protein-protein communication within the transcription apparatus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2483–2489. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2483-2489.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itaya M. Construction of a novel tetracycline resistance gene cassette useful as a marker on the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1992;56:685–686. doi: 10.1271/bbb.56.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenney T J, Moran C P., Jr Genetic evidence for interaction of sigma A with two promoters in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3282–3290. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3282-3290.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroos L, Kunkel B, Losick R. Switch protein alters specificity of RNA polymerase containing a compartment-specific sigma factor. Science. 1989;243:526–529. doi: 10.1126/science.2492118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuldell N, Hochschild A. Amino acid substitutions in the −35 recognition motif of sigma 70 that result in defects in phage lambda repressor-stimulated transcription. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2991–2998. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2991-2998.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunkel B, Kroos L, Poth H, Youngman P, Losick R. Temporal and spatial control of the mother-cell regulatory gene spoIIID of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1735–1744. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.11.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kunkel B, Losick R, Stragier P. The Bacillus subtilis gene for the development transcription factor sigma K is generated by excision of a dispensable DNA element containing a sporulation recombinase gene. Genes Dev. 1990;4:525–535. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunkel B, Sandman K, Panzer S, Youngman P, Losick R. The promoter for a sporulation gene in the spoIVC locus of Bacillus subtilis and its use in studies of temporal and spatial control of gene expression. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3513–3522. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3513-3522.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LeBlanc D J, Lee L N, Inamine J M. Cloning and nucleotide base sequence analysis of a spectinomycin adenyltransferase AAD(9) determinant from Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1804–1810. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung D W, Chen E, Goeddel D V. A method for random mutagenesis of a defined DNA segment using a modified polymerase chain reaction. Technique. 1989;1:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li B, Wing H, Lee D, Wu H-C, Busby S. Transcription activation by Escherichia coli FNR protein: similarities to, and differences from, the CRP paradigm. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2075–2081. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.9.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li M, Moyle H, Susskind M M. Target of the transcriptional activation function of phage lambda cI protein. Science. 1994;263:75–77. doi: 10.1126/science.8272867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Losick R, Stragier P. Crisscross regulation of cell-type-specific gene expression during development in B. subtilis. Nature. 1992;355:601–604. doi: 10.1038/355601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Makino K, Amemura M, Kim S K, Nakata A, Shinagawa H. Role of the sigma 70 subunit of RNA polymerase in transcriptional activation by activator protein PhoB in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1993;7:149–160. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mencia M, Monsalve M, Rojo F, Salas M. Transcription activation by phage phi29 protein p4 is mediated by interaction with the alpha subunit of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6616–6620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moran C P., Jr . RNA polymerase and transcription factors. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 653–667. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niu W, Kim Y, Tau G, Heyduk T, Ebright R H. Transcription activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters: two interactions between CAP and RNA polymerase. Cell. 1996;87:1123–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81806-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roels S, Driks A, Losick R. Characterization of spoIVA, a sporulation gene involved in coat morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:575–585. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.575-585.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roels S, Losick R. Adjacent and divergently oriented operons under the control of the sporulation regulatory protein GerE in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6263–6275. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6263-6275.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sacco M, Ricca E, Losick R, Cutting S. An additional GerE-controlled gene encoding an abundant spore coat protein from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:372–377. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.2.372-377.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandman K, Kroos L, Cutting S, Youngman P, Losick R. Identification of the promoter for a spore coat protein gene in Bacillus subtilis and studies on the regulation of its induction at a late stage of sporulation. J Mol Biol. 1988;200:461–473. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90536-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sato T, Harada K, Ohta Y, Kobayashi Y. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis spoIVCA gene, which encodes a site-specific recombinase, depends on the spoIIGB product. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:935–937. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.935-937.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schyns G, Buckner C M, Moran C P., Jr Activation of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIG promoter requires interaction of Spo0A and the sigma subunit of RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5605–5608. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5605-5608.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schyns G, Sobczyk A, Tandeau de Marsac N, Houmard J. Specific initiation of transcription at a cyanobacterial promoter with RNA polymerase purified from Calothrix sp. PCC 7601. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:887–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stragier P, Kunkel B, Kroos L, Losick R. Chromosomal rearrangement generating a composite gene for a developmental transcription factor. Science. 1989;243:507–512. doi: 10.1126/science.2536191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stragier P, Losick R. Molecular genetics of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:297–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Fitz-James P C, Aronson A I. Cloning and characterization of a cluster of genes encoding polypeptides present in the insoluble fraction of the spore coat of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3757–3766. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3757-3766.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang J, Ichikawa H, Halberg R, Kroos L, Aronson A I. Regulation of the transcription of a cluster of Bacillus subtilis spore coat genes. J Mol Biol. 1994;240:405–415. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng L, Halberg R, Roels S, Ichikawa H, Kroos L, Losick R. Sporulation regulatory protein GerE from Bacillus subtilis binds to and can activate or repress transcription from promoters for mother-cell-specific genes. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91051-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng L B, Losick R. Cascade regulation of spore coat gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1990;212:645–660. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90227-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou Y, Pendergrast P S, Bell A, Williams R, Busby S, Ebright R H. The functional subunit of a dimeric transcription activator protein depends on promoter architecture. EMBO J. 1994;13:4549–4557. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06776.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]