Abstract

Expertise refers to outstanding skill or ability in a particular domain. In the domain of emotion, expertise refers to the observation that some people are better at a range of competencies related to understanding and experiencing emotions, and these competencies may help them lead healthier lives. These individual differences are represented by multiple constructs including emotional awareness, emotional clarity, emotional complexity, emotional granularity, and emotional intelligence. These constructs derive from different theoretical perspectives, highlight different competencies, and are operationalized and measured in different ways. The full set of relationships between these constructs has not yet been considered, hindering scientific progress and the translation of findings to aid mental and physical well-being. In this article, we use a scoping review procedure to integrate these constructs within a shared conceptual space. Scoping reviews provide a principled means of synthesizing large and diverse literature in a transparent fashion, enabling the identification of similarities as well as gaps and inconsistencies across constructs. Using domain-general accounts of expertise as a guide, we build a unifying framework for expertise in emotion and apply this to constructs that describe how people understand and experience their own emotions. Our approach offers opportunities to identify potential mechanisms of expertise in emotion, encouraging future research on those mechanisms and on educational or clinical interventions.

Keywords: alexithymia, emotional awareness, emotional creativity, emotional granularity, emotional intelligence

Remember the old story about the blind men and the elephant? Each touching a different part of an elephant to learn what it is like, they proclaim it to have different properties. The blind men analogy illustrates how important constructs in psychology are rediscovered, defined in slightly different ways, and labeled with slightly different words. The domain of emotion has an example of one of these situations, represented by constructs including emotional awareness, emotional clarity, emotional complexity, emotional granularity, and emotional intelligence. These constructs share the observation that some people are better than others at a range of competencies related to understanding and experiencing emotions, and these competencies may help them lead healthier lives. There are differences in how these constructs are operationalized and measured, and in the theoretical perspectives that inform them. There have been calls to directly compare and integrate these constructs and their measures (e.g., Gohm & Clore, 2000; Grossmann et al., 2016; Grühn et al., 2013; Ivcevic et al., 2007; Joseph & Newman, 2010; Kang & Shaver, 2004; Kashdan et al., 2015; Lindquist & Barrett, 2008; Lumley et al., 2005; Maroti et al., 2018; Schimmack et al., 2000). In response, we collected them under the term “expertise” for its reference to outstanding skill or ability in a particular domain (Ericsson et al., 2018). Our goal is to craft a unifying framework to evaluate findings, offering an opportunity to accumulate knowledge with clear ties to mental and physical well-being.

To create this framework, we use domain-general accounts of expertise to deductively articulate a set of core features. We then use this framework to structure the findings from a scoping review of constructs that describe individual differences in emotional competencies. Scoping reviews provide a principled means of synthesizing large and diverse literatures in a transparent fashion, allowing scientists to identify similarities as well as gaps and inconsistencies across constructs (Pham et al., 2014). We use the results of our scoping review to evaluate an integrative framework for structuring future work, with implications for the conceptual model that may best guide that work. This approach, we suggest, organizes scientific knowledge, and reveals potential mechanisms to motivate programs of research and intervention. As proof of concept, we focus this article on the mental representation of one’s own emotional experience. Future work can expand this framework to include, for example, constructs related to the representation of others’ emotional experiences, or to the regulation of emotion.

We begin this article by briefly reviewing the history of individual differences in the mental representation of emotional experience, illustrating the proliferation of constructs in this domain and its consequences for scientific research and clinical practice. Next, we introduce the construct of expertise and the features of our unifying framework. In the Method section, we provide details on the scoping review procedure that we used to integrate included constructs (noted in italics throughout) within a shared conceptual space. In the Results section, we illustrate this conceptual space using a series of networks that allow us to visualize and describe the relationships between constructs. We then remap the included constructs onto a common expertise framework, through this process interrogating the theoretical perspectives associated with different constructs, as well as the relationship between construct and measurement. Finally, in the Discussion, we consider the conceptual and methodological advances suggested by our unifying framework, including their potential impacts on future work.

Individual Differences in the Mental Representation of Emotional Experience

There is a growing number of constructs that describe how people understand and experience their own emotions. A brief history of this domain provides a sense of its scope and complexity. Interest in individual differences in the mental representation of emotional experience is found within the psychoanalytic tradition around the beginning of the 20th century (e.g., Freud, 1891, 1895). With few exceptions (e.g., Meltzoff & Litwin, 1956; Saul, 1947; Wessman & Ricks, 1966), early scientific study was focused on clinical diagnosis and treatment (e.g., Freedman & Sweet, 1954; Henry & Shlien, 1958; Ruesch, 1948).1 This research often centered on patients with psychosomatic disorders (e.g., Alexander, 1950; MacLean, 1949; Marty & de M’Uzan, 1963), leading to the formalization of the construct of alexithymia in the 1970s (e.g., Nemiah, 1970; Nemiah et al., 1976; Sifneos, 1972). (Construct definitions can be found in Table 2; for more in-depth construct summaries, see Supplemental Materials.)

Table 2.

Summary of Constructs for the Mental Representation of Emotional Experience

| Construct | Definition | Common measure(s) | Measure type | Dominant theoretical perspective(s)a | Publications reviewedb | Publications included | Example publication(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexithymiaf | The inability to identify, describe, and introspect about one’s emotional experiences (Aaron et al., 2018); the inability to mentally represent one’s emotional experiences (Lane et al., 2015) | Toronto Alexithymia Scale, 20-item version (TAS-20; Bagby et al., 1994)c | Global self-report | Psychoanalytic (historical) | 164 | 43 | Nemiah and Sifneos (1970); Taylor et al. (1985) |

| Awareness | The extent to which one understands, describes, and attends to one’s emotional experiences (Mankus et al., 2016) | Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale (LEAS; Lane et al., 1990); Trait Meta-Mood Scales (TMMS) for Clarity, Attention (Salovey et al., 1995) | Task performance; Global self-report | Cognitive-developmental; Appraisal | 148 | 13 | Lane and Schwartz (1987); Thompson et al. (2009) |

| Clarity | The extent to which one unambiguously identifies, labels, and describes one’s own emotional experiences (Boden & Thompson, 2017) | TMMS, Clarity subscale (Salovey et al., 1995); TAS-20, Difficulty Identifying Feelings subscale (TAS-20, DIF; Bagby et al., 1994) | Global self-report | Appraisal | 148 | 12 | Salovey et al. (1995); Boden and Berenbaum (2011) |

| Competenceg | The extent to which one identifies, expresses, understands, regulates, and uses one’s own emotions and those of others (Brasseur et al., 2013) to facilitate appropriate actions (Izard, 2009) | Emotional Competence Inventory (ECI; Boyatzis et al., 2000); Profile of Emotional Competence (PEC; Brasseur et al., 2013)d | Multirater assessment; Global self-report | Basic emotion; Appraisal (causal) | 44 | 5 | Boyatzis et al. (2000); Brasseur et al.(2013) |

| Complexity | The extent to which one simultaneously experiences different(ly valenced) emotions, and/or differentiates between a varied and nuanced set of emotions (Grühn et al., 2013) | Range and Differentiation of Emotional Experiences Scale (RDEES; Kang & Shaver, 2004); Empirically derived indices from emotion intensity ratings | Global self-report; Experience samplinge | Cognitive-developmental; Appraisal | 126 | 18 | Kang and Shaver (2004); Grühn et al. (2013) |

| Creativity | The ability to produce emotional responses that are novel, authentic, and effective, as well as one’s preparedness to use this ability (Averill, 1999) | Emotional Creativity Inventory (Averill, 1999); Emotional Consequences, Emotional Triads (Averill & Thomas-Knowles, 1991) | Global self-report; Task performance | Constructionist (social) | 33 | 6 | Averill and Thomas-Knowles (1991); Averill (1999) |

| Diversityh | The variety and relative abundance of the emotions one experiences (Quoidbach et al., 2014); the breadth of emotions one experiences (Kang & Shaver, 2004) | Empirically derived index across emotion frequency ratings; RDEES, Range subscale (Kang & Shaver, 2004) | Experience samplinge; Global self-report | Appraisal; Constructionist (psychological) | 53 | 4 | Quoidbach et al. (2014); Sommers (1981) |

| Flexibility | The ability to adapt one’s emotional experiences in a situation-specific manner (Fu et al., 2018) | Changes in emotion intensity ratings after mood induction; Emotional Flexibility Scale (Fu et al., 2018) | Mood induction; Global self-report | Appraisal | 54 | 4 | Waugh et al. (2011); Zhu and Bonanno (2017) |

| Granularityi | The ability to represent one’s emotional experience in a nuanced and specific manner, often (but not always) marked through language (Lee et al., 2017; Tugade et al., 2004) | Within-person correlations (e.g., intraclass correlations) across emotion intensity ratings; RDEES, Differentiation subscale (Kang & Shaver, 2004) | Experience samplinge; Global self-report | Constructionist | 153 | 24 | Barrett (2017a); Barrett et al. (2001); Tugade et al. (2004) |

| Intelligencej | The ability to perceive and express emotion, understand and reason with emotion, and regulate emotion in the self and others (Mayer et al., 2000) | Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT; Mayer et al., 2002)c | Task performance | Basic emotion; Appraisal (causal) | 353 | 44 | Mayer and Salovey (1997); Bar-On (1997); Siegling et al. (2015) |

Without modifiers, names of theoretical perspectives are inclusive of all variants (e.g., “appraisal” includes “descriptive” and “causal” perspectives; “constructionist” includes “psychological,” “neural,” “developmental,” etc.). Research on alexithymia is historically derived from the psychoanalytic tradition, with contemporary accounts departing from this theoretical perspective.

Number of publications identified through database searching and/or key reviews.

Other common measures are discussed in the Supplemental Materials.

Also assessed as intelligence.

Experience sampling measures are analyzed to produce behavioral indices.

Includes agnosia.

Includes utilization.

Includes range.

Includes differentiation.

Includes quotient.

In the 1980s and 1990s, an explosion of emotion-related research produced constructs such as emotional intelligence (e.g., Goleman, 1995; Salovey & Mayer, 1990), emotional awareness (Lane et al., 1990; Lane & Schwartz, 1987), emotional complexity (e.g., Larsen & Cutler, 1996; Tobacyk, 1980), emotional creativity (Averill & Thomas-Knowles, 1991), emotional literacy (e.g., Steiner, 1984), and emotional fitness (Cooper & Sawaf, 1997). Emotional intelligence, especially, became a hotspot of activity in both the academy (e.g., Bar-On, 1997; Mayer & Salovey, 1997; Schutte et al., 1998) and industry (e.g., Cooper & Sawaf, 1997; Grandey, 2000; Law et al., 2004). Constructs continued to proliferate, such as emotion differentiation (Barrett et al., 2001) and its synonym emotional granularity (Tugade et al., 2004), emotional clarity (e.g., Palmieri et al., 2009), and emotional flexibility (Waugh et al., 2011). Today, a quick Internet search turns up additional constructs, such as emotional agility (David, 2016), emodiversity (Quoidbach et al., 2014), and affective agnosia (Lane et al., 2015). To make matters more complex, most constructs are associated with multiple measures (e.g., there are nine measures for alexithymia in adults reviewed in Bermond et al., 2015), and some measures are used to assess more than one construct. For example, the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS; e.g., Bagby et al., 1994) has been used as an index of emotional clarity (e.g., Erbas et al., 2018) and the Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale (LEAS; Lane et al., 1990) has been used as a measure of alexithymia (e.g., Lane et al., 1996).

When a phenomenon is important in psychological science, it is discovered again and again, each time with a different name and emphasizing different features. There are many reasons for this state of affairs (e.g., “Psychologists treat other peoples’ theories like toothbrushes—no self-respecting person wants to use anyone else’s.”; Mischel, 2008). Nonetheless, this construct proliferation comes with a cost: It slows the accumulation of knowledge, causes problems with reproducibility, and obscures common mechanisms. Construct proliferation also limits the applied potential of research in this domain. Each construct purports to—and often does—predict indicators of mental and physical health, among other real-world outcomes. This overlap is problematic if scientists and clinicians do not understand why a construct confers protection. For example, alexithymia is (positively) associated with mental health disorders, substance abuse and eating disorders, chronic pain and functional gastrointestinal disorders, and coronary heart disease (see Bermond et al., 2015; Lumley et al., 2007; Taylor, 2000, for reviews). However, emotional intelligence is also (negatively) associated with depression and anxiety symptoms, substance abuse, and physical health complaints (see Bar-On, 2000; Mayer et al., 2008; Salovey et al., 2002; Zeidner et al., 2012, for reviews).

Many constructs for how people understand and experience their own emotions have in common the idea that mentally representing emotional experience is an ability or skill that can be learned, practiced, and honed, making these constructs particularly compelling targets for research and intervention. Improvement in ability over time provides insight into developmental pathways and means by which skills can be harnessed for well-being. Viewing the mental representation of emotional experience as an ability or skill also connects these constructs with the concept of expertise. In the next section, we expand upon this connection and use it to motivate our unifying framework.

What Is Expertise?

Expertise has previously been mentioned with regard to emotion-related abilities (e.g., Mayer et al., 2001; McBrien et al., 2020; Pistoia et al., 2018; von Salisch, 2001), but has not been used as a framework for systematic investigation and synthesis. Expertise has several defining characteristics that are relevant to the domain of emotion, as it is: (a) supported by extensive and specific domain knowledge, (b) characterized by enhanced information-processing capacities, (c) demonstrated through reliable task performance, and (d) developed through awareness and deliberate practice (e.g., Bédard & Chi, 1992; Steels, 1990; Sternberg, 1998; Ullén et al., 2016). To create a framework that can be flexibly applied to constructs for individual differences in emotional competencies, we distilled these defining characteristics into a set of 12 core features (Table 1). We identified these features deductively, based on prior literature on expertise and findings in domain-general psychological science. We briefly review each of these features (noted in bold throughout), use it to describe a quality of experts in contrast to novices, and pose a hypothesis about its role in the domain of emotion.

Table 1.

Features of Expertise

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Structure of knowledge | Differentiated, efficiently organized concepts |

| Breadth of knowledge | Diverse, elaborated concepts |

| Type of knowledge | Specialized, domain-relevant concepts |

| Mental representation | Sophisticated, relational processing |

| Verbal representation | Specific labeling, description |

| Ability or skill | Reliable, task-based performance |

| Adaptive responses | Effective actions, outcomes |

| Context-specificity | Situation-dependent flexibility |

| Awareness | Conscious access |

| Attention | Reflective monitoring |

| Deliberate practice | Intentional improvement, expansion |

| Prediction | Proactive planning, adjustment |

Extensive and Specific Domain Knowledge

Expertise requires a broad and efficiently structured body of specialized domain knowledge (Bédard & Chi, 1992). This knowledge includes both explicit, declarative knowledge of domain-relevant concepts, as well as implicit, functional knowledge of how those concepts might be deployed (Sternberg, 1998; Sternberg et al., 1995; see also the distinction between deep and surface knowledge by Steels, 1990). In other words, there are types of knowledge that experts must possess. Experts’ concepts are organized into highly interconnected networks, as opposed to novices who have fewer and weaker links between concepts (Bédard & Chi, 1992; Sternberg, 1998). Experts’ concepts are also more specific and lead to a subordinate-level shift in categorization (e.g., Bukach et al., 2006). For novices, categorization proceeds according to boundaries established as “cognitively basic” in a given cultural context (Rosch et al., 1976). In contrast, experts are able to differentiate between more specific categories (Tanaka & Taylor, 1991; see also Schyns, 1991; Schyns et al., 1998). While novices might see only yellow versus green, color experts such as painters might distinguish lime, olive, and chartreuse. This differentiation extends to how experts verbally represent their experience by using language to label specific categories or describe specific properties (Tanaka & Taylor, 1991; Tversky & Hemenway, 1984).

In the domain of emotion, these features suggest that experts possess concepts for emotion that are varied and precise. We hypothesize that these concepts build upon functional knowledge of the domain: what emotions can and typically mean, when they are helpful or appropriate, how to smoothly navigate transitions, etc. We further hypothesize that experts can easily name the experiences that correspond with these concepts, going beyond conventional levels of description (e.g., “angry”) to pinpoint their feelings more exactly (e.g., “livid,” “resentful,” “amped up”).

Enhanced Information-Processing Capacities

Experts also differ from novices in how they implement domain-relevant knowledge (Steels, 1990), and exhibit enhanced information-processing capacities (Bédard & Chi, 1992; Sternberg, 1998; Ullén et al., 2016). Whereas novices rely on surface-level perceptual features to make decisions and predictions, experts harness abstract, functional features to optimally address task demands (Bédard & Chi, 1992; Schyns et al., 1998). For example, a novice may believe olive and chartreuse work equally well for painting a wall “green,” whereas an expert would consider the impacts of undertone and lighting on perceived color—and may ultimately suggest emerald to create a balanced calm (e.g., Goldstone, 1995). Experts can differentiate between categories that seem equivalent to novices (e.g., olive and chartreuse) because they employ more precise features to encode similarities and contrasts (e.g., breaking down “color” into the properties of hue, saturation, and brightness; Burns & Shepp, 1988; Goldstone, 1994; see also Schyns et al., 1998; Tanaka, 1998; Williams et al., 1998). In this way, experts easily construct sophisticated mental representations, and use nonobvious properties (e.g., the mood associated with a color) to determine which action is maximally effective at achieving a given goal (Sternberg, 1998). This type of holistic and relational processing is a hallmark of expertise and impacts how new knowledge is acquired. While novices learn by rote, experts can efficiently generalize to new exemplars using abstract, functional similarities (Bukach et al., 2006).

In the domain of emotion, “mental representation” suggests, at its most fundamental level, that individuals can process information from the body (e.g., visceral sense data) and/or from the world (e.g., vocal tones of others) as features of emotional experience. We hypothesize that experts in emotion build on this ability by identifying the psychological features that are most functionally salient and disregarding perceptual similarities or contrasts that are functionally irrelevant (e.g., by understanding that heart palpitations and fatigue can both signal anxiety in the context of an upcoming deadline).

Reliable Task Performance

Expertise is not only a matter of having domain-relevant knowledge and enhanced information-processing capacities; these must also be demonstrated through measurable behavioral outcomes. Experts are distinguished from nonexperts on the basis of ability or skill in task performance that is reliable and replicable (Ericsson & Lehmann, 1996; Ericsson & Ward, 2007). For example, an expert painter produces works of art that consistently exemplify color theory; an expert interior designer is highly recommended by satisfied customers. This suggests that individual differences in expertise should be derived from a series of adaptive responses, observed over time or across contexts, and judged according to their context-specific efficacy (Ericsson & Lehmann, 1996; Ericsson & Smith, 1991). In contrast to novices, experts flexibly adapt their actions to the situation at hand. Multiple methods can be used to assess expertise depending on the ability or skill in question. Different aspects of color expertise might be demonstrated via perceptual discrimination, verbal fluency, or practical application (e.g., interior design that leads to shorter recovery time, reduced pain medication, and increased satisfaction in hospital patients; Rubin et al., 1998).

In the domain of emotion, these features suggest that expertise is best assessed using tasks that require individuals to “perform” mental representation of emotional experience—in other words, to document or communicate their thoughts and feelings. We hypothesize that these tasks vary in the amount of constraint placed on the response (e.g., endorsing a set of emotion adjectives vs. freely describing an emotional episode), but in principle should be unconstrained enough to allow for variation across contexts (i.e., flexibility). We further hypothesize that these tasks should be repeated to assess patterns of behavior over time (i.e., reliability).

Awareness and Deliberate Practice

Scientists debate the extent to which expertise in a particular domain is due to trait-level dispositions or genetic factors (e.g., Ericsson, 2014; Plomin et al., 2014a, 2014b). There is overall consensus, however, that substantial training is critical to developing expertise and that expertise can be enhanced through deliberate practice (Ullén et al., 2016). Deliberate practice involves both improving existing skills and expanding the set and scope of skills. This is done by updating knowledge, identifying alternative solutions, and encountering novel experiences (Ericsson, 2006; Ericsson & Charness, 1994). An expert painter might seek out opportunities to work with new colors, subject matter, or materials, and might spend time learning about pigments and application techniques to create particular impressions (Ford, 2016; Protter, 1997). These processes require awareness and sustained attention (Ericsson, 2007; Ullén et al., 2016). Experts engage in reflective and careful monitoring of their domain understanding and abilities (Sternberg, 1998). This regular evaluation leads to more effective resource allocation (Sternberg, 1984; Sternberg & Kagan, 1986), such that experts are better at determining what information to attend to and how to prepare for upcoming demands. That is, experts are better at predicting what will happen next and planning their actions accordingly, thereby minimizing error and meeting situation-specific needs more efficiently.

In the domain of emotion, these features suggest that experts continue to hone their ability to mentally represent emotional experiences. We hypothesize that they do so by actively attending to their experiences of emotion, and by receiving repetitive, unambiguous feedback from social others (Laland, 2017). By “practicing” emotion in these ways, we hypothesize that experts become better equipped for future events and challenges.

The features in Table 1, when taken together, describe expertise as skilled performance within a given domain and relative to situation-specific needs. Experts must possess the “basic” domain knowledge shared by other culture members (e.g., a color expert must learn primary and secondary color categories, their prototypical hues, boundaries, and names) as well as specialized knowledge shared by other domain experts (e.g., the difference between hue, saturation, and brightness). Experts can also flexibly deploy this knowledge, depending on context-driven goals or functions: For example, an expert uses different language when describing the color of a toy apple to an American toddler (“red”) than when suggesting a pigment for painting a stormy night sky (“Pantone 7545c”). These become important points as we return to the discussion of expertise in the domain of emotion and use the above features to build an organizational framework. To inform this process, we conducted a scoping review of individual differences in the mental representation of emotional experience, which we describe next.

Method

Scoping Review Overview

Scoping reviews are a rigorous and transparent process for surveying the literature on broad topics (Pham et al., 2014) that aim to map key constructs and sources and types of data (Mays et al., 2001), as well as to depict the interrelations among these constructs. As such, scoping reviews can be particularly useful when the topic is complex or heterogeneous because they can identify gaps and assess the value of undertaking further research (Daudt et al., 2013). The most common scoping review procedure is the iterative process proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), which involves identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; selecting studies; charting the data; and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

In the present article, we followed this approach to synthesizing research. After formulating our research question, we (a) identified relevant constructs; (b) selected relevant publications; (c) extracted and (d) organized the data; and (e) summarized, illustrated, and synthesized the results. Throughout this process, we were guided by the materials from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) workgroup (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2009). We also looked to qualitative synthesis methods to inform our use of expertise as an a priori framework for situating and remapping the included constructs. Framework synthesis (Pope et al., 2000), for example, offers a deductive approach to extract and synthesize a large volume of data from qualitative research, and suggests the use of feature-based charts to visually interrogate the nature of constructs under study (for details, see Data Organization section, below; see also Kastner et al., 2012).

Construct Identification

We identified potential constructs to include in the review via several sources, with the goal of being as inclusive as possible. The constructs included in Kashdan et al. (2015)—alexithymia, awareness, clarity, complexity, and differentiation/granularity2—served as an initial base, as this review provided a comprehensive recent starting point. To these, we added other constructs for individual differences in emotional knowledge, repertoire, or skill (i.e., those that describe how people understand and experience their own emotions). The first and senior authors developed a preliminary list of constructs based on their knowledge of the literature, frequent Google Scholar search terms (e.g., which words are suggested after typing “emotion[al]”), and popular science pieces on emotional health. Constructs were iteratively added to the list during publication selection, screening, and full-text review, as described below.

We excluded constructs from further consideration if they dealt exclusively with the perception, expression, or regulation of emotion. These domains were out of scope for the present review due to concerns with size and feasibility. The decision to omit constructs related to emotion regulation was also based on the ontological debate of whether the regulation of emotion is fundamentally different from its mental representation or experience (Gross & Barrett, 2011). However, the close relationship between emotion representation and regulation also meant that it was impossible to draw a clean line for construct inclusion. Some constructs, such as intelligence and competence, include the ability to regulate emotion (among other core aspects). We have retained these constructs because of their prominence in the literature on emotion-related abilities and their previous ties to expertise (e.g., Mayer et al., 2001).

Constructs were also excluded if they: were not specific to emotion (e.g., social skill; Riggio, 1986 or resilience; Connor & Davidson, 2003); had strictly interpersonal meanings (e.g., affective sensitivity; Kagan & Schneider, 1987 or emotional literacy; Steiner, 1984); were formulated only within a developmental, lifespan, or industrial/organizational context (e.g., affective social competence; Halberstadt et al., 2001 or emotional fitness; Cooper & Sawaf, 1997). Because our focus is on the mental representation of emotional experience, we excluded constructs dealing with general affect (i.e., pleasant vs. unpleasant mood) and the dynamics therein (e.g., affect intensity; Larsen & Diener, 1987, affective instability; Trull et al., 2008, or trait affect; Watson & Walker, 1996). We were interested in constructs with impacts for health and well-being; however, this was not a formalized criterion.

The first author reviewed example publications for each potential construct to determine if it met criteria for inclusion. Final decisions regarding inclusion were made through discussion with the senior author. In cases of uncertainty or disagreement, we erred on the side of inclusion. In total, we considered 133 constructs, of which 40 were included. For a full list of included constructs and corresponding publication search results, see Table S1. For a full list of excluded constructs, example publications, and reasons for exclusion, see Table S2.

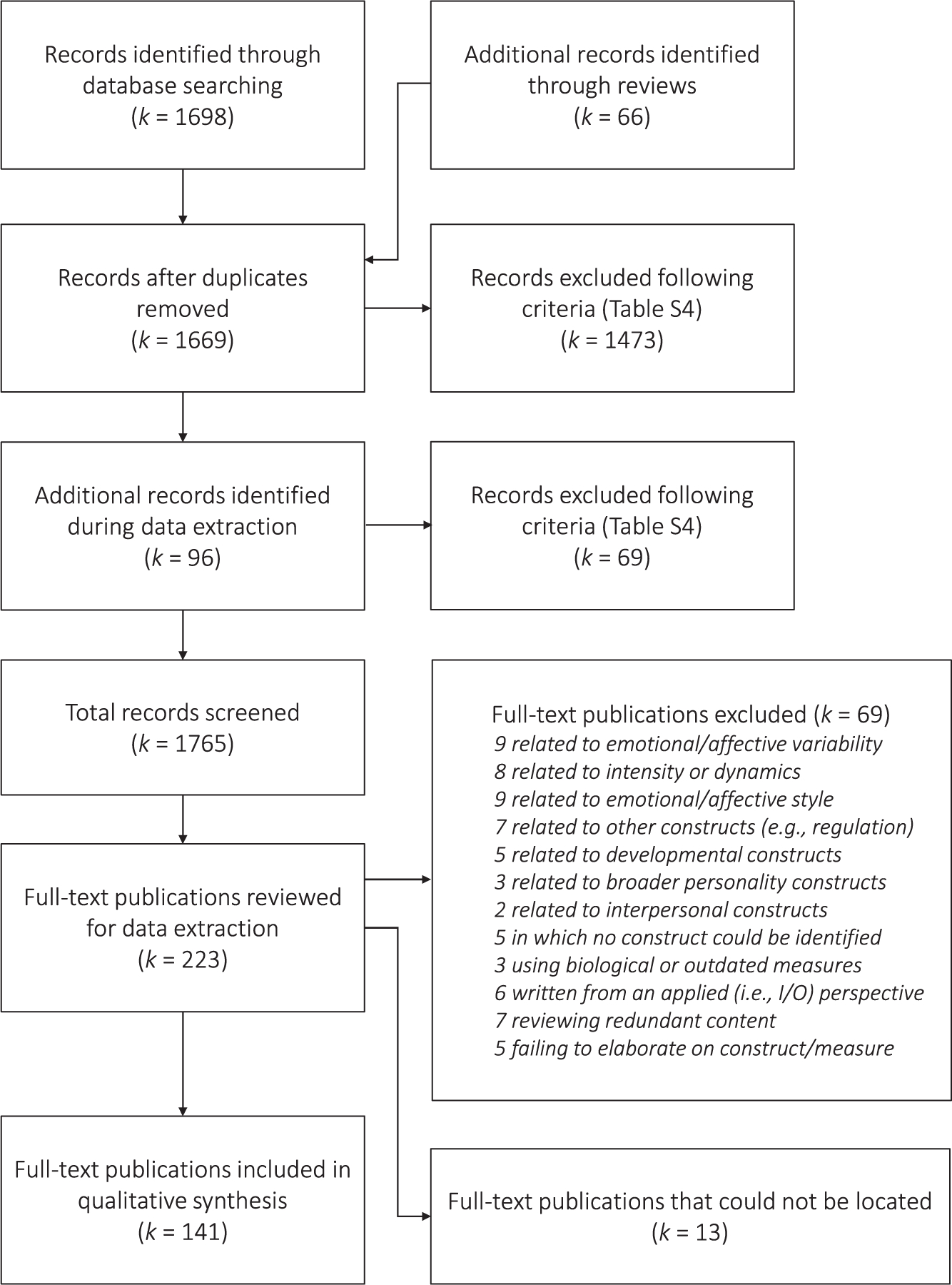

Publication Selection

The American Psychological Association’s PsycINFO database was used to locate literature published up to the date of search; primary searches were conducted between May and October of 2018, going back to the earliest print date of 1927. Literature for each construct was searched separately, with the construct name as the keyword for the search (e.g., “alexithymia”). Multiword constructs were searched using several keyword phrases to ensure all possible variants were included in review: “emotional [CONSTRUCT]” (e.g., “emotional awareness”), “emotion [CONSTRUCT]” (e.g., “emotion awareness”), “affective [CONSTRUCT]” (e.g., “affective awareness”), and “affect [CONSTRUCT]” (e.g., “affect awareness”).3 Only literature written in English and in peer-reviewed journals or edited volumes was included; gray literature (e.g., dissertations or theses) was not considered. Results were further filtered to include only publications in which the keyword (phrase) was included in the title or abstract. See Figure 1 for a flowchart of publication identification, screening, and review. For a full list of search terms, dates, and hits, see Table S1.

Figure 1. Flowchart Describing Identification, Abstract Screening, and Full Review of Publications, Based on PRISMA Guidelines by Moher et al. (2009).

Note. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Four search terms generated more than 500 hits in PsycINFO, even after filters were applied: “alexithymia” (2,529 records), “emotional awareness” (548 records), “emotional competence” (681 records), and “emotional intelligence” (3,428 records). Because the volume of results for these four constructs far out-weighed that of the others (which together yielded 1,316 records), and would have been unfeasible to review, we followed a two-part procedure to select relevant literature. First, we entered these search terms in Clarivate’s Web of Science database (which covers publications from 1900), where we could sort search results based on the number of citations. As before, we searched only for phrases appearing in the publication “topic,” with publications limited to articles, reviews, and book chapters written in English. In this case, however, we only selected those publications with at least 100 citations. This resulted in a much-reduced set of 382 records to be screened across the four constructs (Table S1). Second, to ensure we captured all key publications, we consulted a set of reviews for each construct (Table S3). Based on and including these reviews, we identified 66 publications potentially related to construct definition and measurement. These records were individually added to the list for further screening. Altogether, this process yielded 1,764 publications; 95 duplicates were removed, leaving 1,669 unique records.

Two trained undergraduate research assistants screened abstracts for identified publications to confirm they met the criteria for inclusion. Publications were excluded from further review if they: (a) described the construct or measure in relation to a specific domain (e.g., art appreciation, romantic relationships); (b) assessed the construct using only biological measures (e.g., fMRI or EEG); or (c) merely applied an existing measure to a sample of participants, without modifying that measure or directly comparing it to another (Table S4). Throughout this screening process, our goal was to identify publications that introduced, reformulated, critiqued, or compared the constructs of interest and their corresponding measures. We focused on these publications because they are especially likely to provide clear construct definitions and direct information on interrelationships between multiple constructs or measures. Of note, comparisons between constructs or measures could be either conceptual or empirical. All abstracts were screened independently by both research assistants, with the first and/or senior author adjudicating difficult or ambiguous cases. Of the 1,669 publications screened, 1,473 were excluded (i.e., 196 were retained at this stage).

Data Extraction

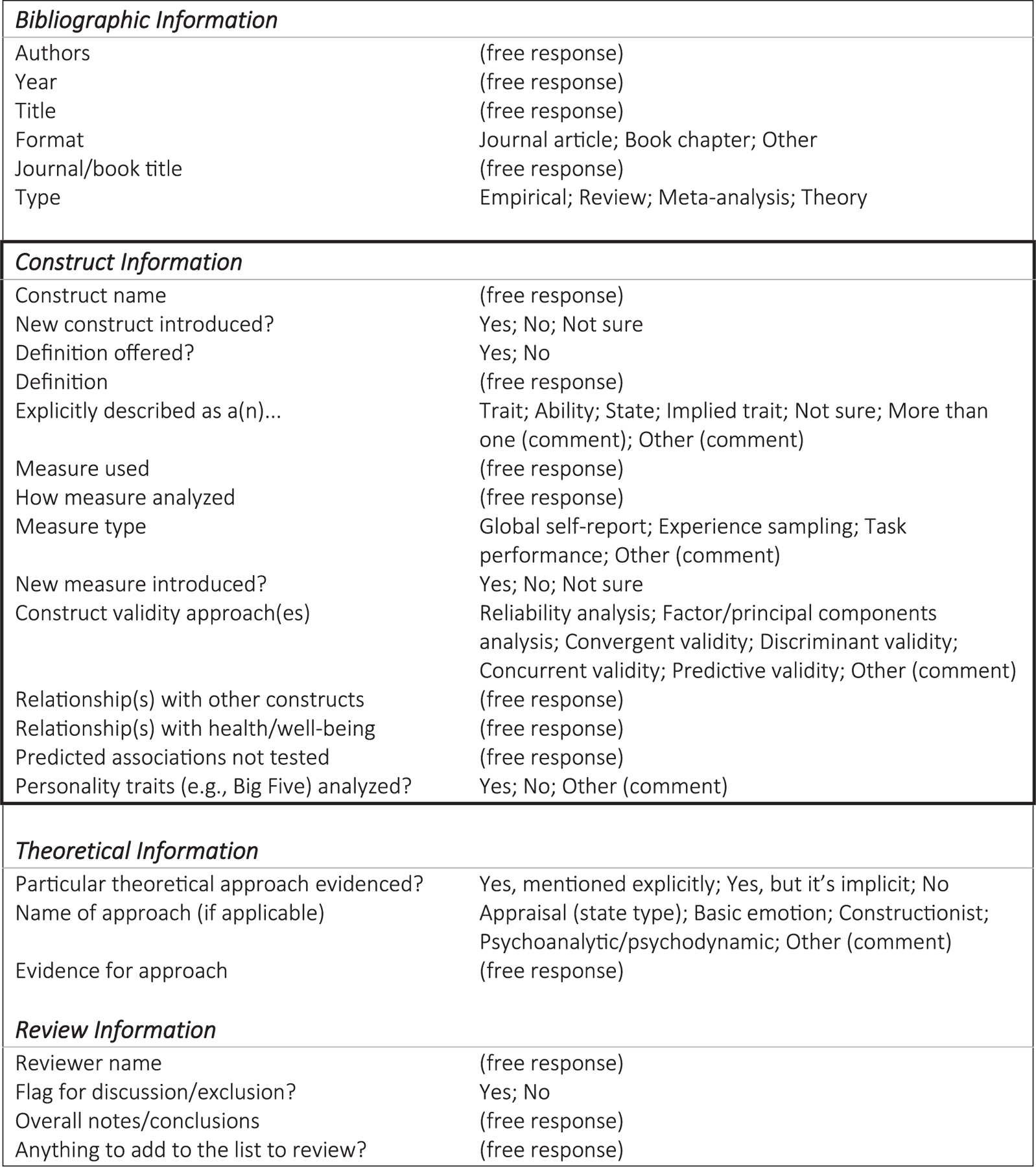

Data from publications were extracted following a coding procedure designed to capture each construct’s definition, measurement, validity, and relationships with other psychological and health variables, as well as theoretical background. For each publication, we recorded the information provided in Figure 2. Because publications could describe more than one construct, construct-specific items could be repeated until all constructs were documented.

Figure 2. Data Extraction Template Completed for Each Fully Reviewed Publication.

Note. Questions regarding a specific construct (“Construct Information” box) were repeated until all included constructs had been documented.

Publications were randomly assigned to a team of two reviewers. Both members of the team independently read and coded the publication and resolved any discrepancies through discussion to produce a consensus record.4 Difficult or ambiguous cases were addressed in meetings with all reviewers. As part of data extraction, reviewers were asked to identify, from the works cited, any additional publications that may be relevant. This iterative identification method extended our previous search and selection steps, as it was not constrained by the presence of specific keywords. Ninety-six publications were added in this way, 27 of which passed screening for further review, bringing the total to 223 publications. Full print or online versions could not be located for 13 records (e.g., they were published in books only held by European libraries), such that data were extracted for 210 publications.

Reviewers could recommend that a publication be excluded from analysis. For example, the full version of an article might have clarified that one or more of the inclusion criteria had not been met (see Figure 1, for list of reasons for exclusion). Through reading and discussion, we also decided to exclude all publications related to affective/emotional style, as well as those related to affective/emotional variability. We found that style (e.g., Davidson, 1992, 1998, 2000) did not provide sufficient treatment of the mental representation and behavioral measurement of specific emotional experiences (instead focusing on tendencies to approach vs. withdraw and underlying brain systems). Variability was initially included because it can refer to range, diversity, or context-specificity in experienced emotion (e.g., Barrett, 2009; Waugh et al., 2011). However, the publications that met our selection criteria dealt exclusively with affective dynamics.5 With these records removed, 141 publications remained. See Table 2 for a final list of included constructs and the number of publications representing each. The final database of publications, including key data extracted for each, is available via our online data repository (https://osf.io/a6vzk/).

Data Organization

We approached our goal of mapping the selected domain of research, individual differences in the mental representation of emotional experience, in three ways. First, we summarized the definition, common measures, and dominant theoretical perspective of each included construct. To do this, we reviewed the definitions extracted for a given construct and selected a representative (and typically recent) definition based on one or two of the included publications. We also used the extracted data to identify commonly used measures for the construct and their corresponding measurement type. For example, we identified two commonly used measures for awareness. Most of the publications we reviewed used the LEAS(Lane et al., 1990), which is a performance-based measure, but there were also publications that used the Clarity and Attention subscales of the Trait Meta-Mood Scales (TMMS; Salovey et al., 1995), which is a global self-report measure. Similarly, we identified the dominant theoretical approaches or perspectives adopted in publications about the construct. We summarize these data in a Table 2 to provide a high-level overview of the constructs pertaining to the mental representation of emotional experience and to illustrate key commonalities and differences among constructs.

Second, we illustrated the interrelationships between constructs, considering both conceptual and empirical connections. To determine conceptual connections, we reviewed all definitions extracted for a given construct, and any notes made from the included publications’ discussion sections. Constructs were often comprised of multiple facets (i.e., subordinate constructs). For example, Kang and Shaver (2004) define complexity as comprised of range and differentiation; as such, we documented “range” and “differentiation” as facets of “complexity”, as well as links between each facet and the superordinate construct.6 Furthermore, publications often referred to relationships between the constructs in our review. For example, Kang and Shaver (2004) also discuss the relationship between complexity and intelligence, which we documented. In this way, we compiled a list of all the constructs and their facets, and a matrix of the conceptual connections between them.

Using a similar procedure, we built a matrix of empirical connections between constructs, with connections established whenever publications reported correlations between two or more of our included constructs. For each empirical connection, we documented the average effect size of the relationship (i.e., the r value) and the specific measures used. We used the matrices of conceptual connections and empirical connections (available via our online data repository) to build networks that allowed us to examine the relationships between constructs that are hypothesized as well as those that are apparent in the literature.

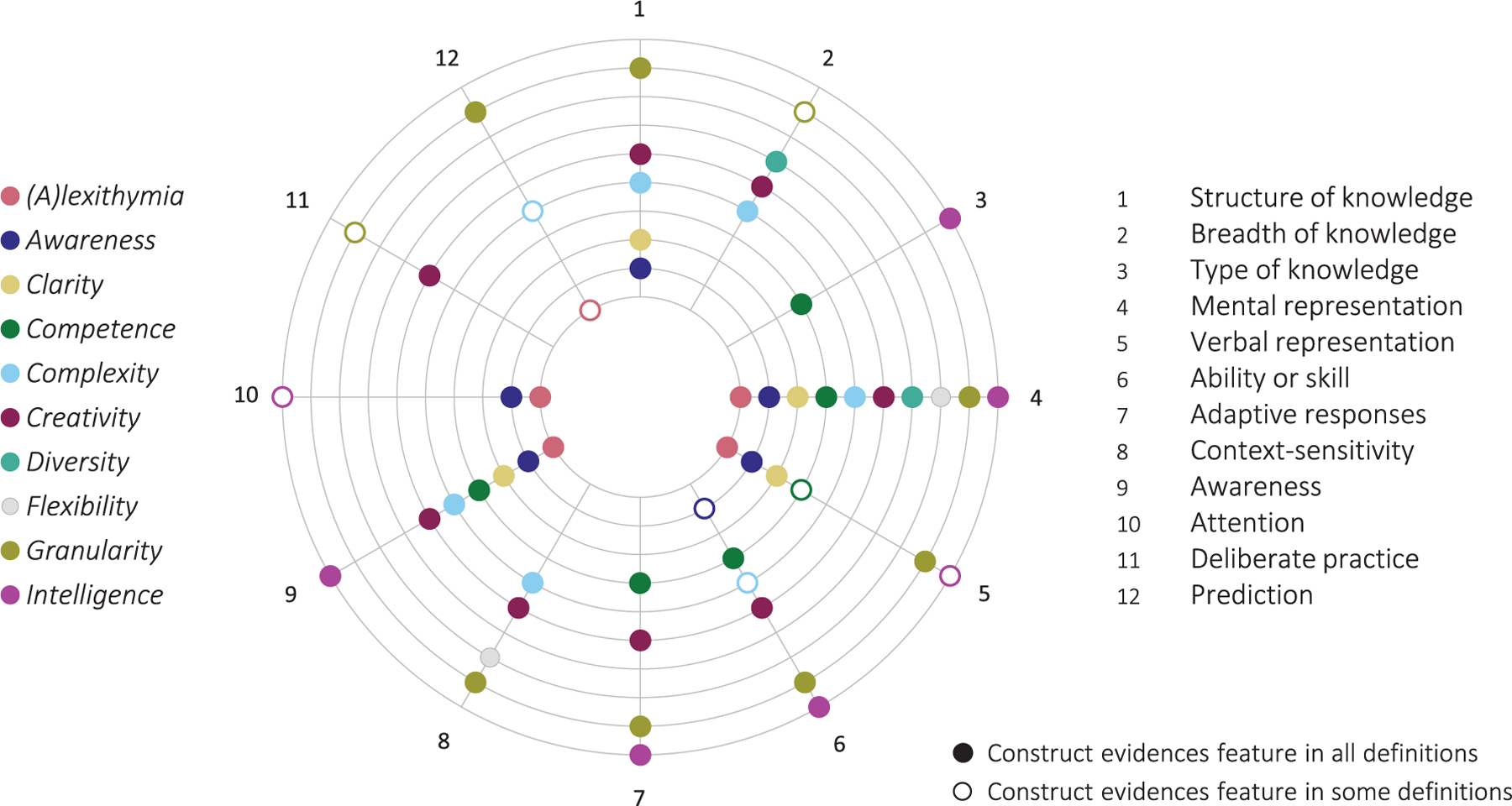

Third, we inductively generated a list of the features of expertise represented by each construct. To do this, we reviewed the definitions, measurement information, and notes extracted from each publication and noted salient characteristics about the construct in question. We then compared these characteristics to the features of domain-general expertise described in Table 1. For example, awareness stresses the role of conscious cognition in emotional experience (Lane et al., 1990; Lane & Schwartz, 1987), and so it fulfills the feature of awareness. Likewise, granularity stresses the need for differentiated emotion concepts (Barrett, 2004, 2017a), and so it fulfills the feature of structure of knowledge. In this way, we used constructs’ key characteristics to map them onto an integrated framework. We present the results of this synthesis as a polar plot illustrating the distribution of features across constructs for the mental representation of emotional experience.

Results

Summarizing Constructs for the Mental Representation of Emotional Experience

Table 2 presents the final list of included constructs along with their definitions, common measures, dominant theoretical perspectives, number of reviewed publications, and key publications (for individual construct summaries, see pages 11–20 of the Supplemental Materials). Ignoring modifiers (e.g., “emotion[al],” “affect[ive]”), there were 15 constructs represented in the extracted data. Two pairs of constructs were synonymous: differentiation and granularity (Kashdan et al., 2015; Smidt & Suvak, 2015),7 and intelligence and quotient (e.g., Bar-On, 1997, 2000). For the present analyses, we adopted the labels “granularity” and “intelligence.” Four constructs—agnosia, diversity, utilization, and range—were represented by only one or two publications each. Based on this small literature size and the constructs’ definitions, we (a) merged diversity and range, (b) subsumed agnosia under alexithymia, and (c) subsumed utilization under competence. Together, these decisions produced a final total of 10 constructs.

Two constructs—alexithymia and intelligence—had particularly large literatures to summarize, with 43 and 44 included publications, respectively. In each case, there are several competing definitions and measures, the history and details of which were out of scope for the present review.8 For current purposes, we focused on the work of Taylor, Bagby, and Parker for alexithymia (e.g., Bagby et al., 1994; Taylor et al., 1985) and the work of Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso for intelligence (e.g., Mayer et al., 2002; Salovey & Mayer, 1990). The definitions and measures introduced by these research groups are the most widely used and/or psychometrically validated in their respective literatures (alexithymia: Lumley et al., 2007; but see Kooiman et al., 2002; intelligence: Cherniss, 2010; Joseph & Newman, 2010; Livingstone & Day, 2005; but see Maul, 2012; Roberts et al., 2010). Other prominent definitions and measures are presented in the Supplemental Materials (e.g., the Emotional Quotient Inventory [EQ-i]; Bar-On, 1997; the Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Questionnaire [BVAQ]; Bermond & Oosterveld, 1994).

The first trend made clear by this summary is a similarity in how these constructs are typically measured. In the research shown in Table 2, nine of the 10 constructs were measured using global self-report instruments (e.g., the Toronto Alexithymia Scale, 20-item version [TAS-20]; Bagby et al., 1994). Seven of the 10 constructs were (also) measured using indices/scores derived from performance-based tasks (e.g., the LEAS; Lane et al., 1990), retrospective emotion frequency ratings (e.g., for calculating diversity; Quoidbach et al., 2014), or in-the-moment emotion intensity ratings (e.g., intraclass correlations for granularity; e.g., Tugade et al., 2004). In-the-moment intensity ratings, which are typically gathered via experience sampling procedures, have been described as a behavioral measure of emotion because they do not rely on memory or aggregation over time (Barrett & Barrett, 2001; Robinson & Clore, 2002). It has been argued that behavioral measures are more appropriate for measuring the skills or abilities represented by the present constructs (Joseph & Newman, 2010; Kashdan et al., 2015; Siegling et al., 2015), whereas global self-report instruments may capture individuals’ beliefs about themselves and other biases (e.g., Barrett, 1997; Mayer et al., 2001; Robinson & Clore, 2002). Notwithstanding, all of the measures reviewed evidenced construct validity and had predictive utility for outcomes of interest (e.g., Bagby et al., 2020).

Another key take-away from Table 2 is the role played by various theoretical perspectives on emotion. Across all 10 constructs, appraisal-theoretic influences appeared most often. These influences included both “causal” appraisal perspectives (e.g., Frijda, 1986; Lazarus, 1991; Plutchik, 1980; Roseman, 1991; Scherer, 1984), which hold that appraisals are mental processes that give rise to the experience of emotion, as well as “descriptive” appraisal perspectives (e.g., Clore & Ortony, 2000, 2008; Moors et al., 2013; Scherer, 2009a, 2009b), which hold that appraisals capture the content or meaning of emotional experience (for the distinction between these approaches, see Barrett, 2016; Barrett et al., 2007; Gross & Barrett, 2011). Work on clarity, diversity, and flexibility has been mostly influenced by appraisal perspectives, whereas work on intelligence and competence has also been shaped by basic emotion perspectives (e.g., Ekman, 1972; Izard, 1993; Tomkins, 1962, 1963) and work on awareness and complexity has also been shaped by cognitive-developmental perspectives (e.g., Labouvie-Vief & Medler, 2002; Lane & Schwartz, 1987; Piaget, 1937; Werner & Kaplan, 1963).

Work on alexithymia has been historically situated within a psychoanalytic or psychodynamic tradition (e.g., Freud, 1891; Marty & de M’Uzan, 1963; Ruesch, 1948), which understands emotional experience as a way of symbolizing or processing internal or unconscious conflicts (e.g., Krystal, 1979; Lesser, 1981; Nemiah & Sifneos, 1970; Taylor, 1984). Contemporary accounts of alexithymia, however, understand it as deficits in the processing of emotional information (e.g., Lane et al., 2000; Lumley et al., 2007). Work on creativity and granularity has been anchored in a (social) constructionist framework (e.g., Averill, 1980; Barrett, 2009; James, 1884; Russell, 2003), which emphasizes the influence of individual history, cultural background, and physical and situational context on the experience of emotion. Each of these theoretical perspectives has implications for understanding individual differences in the mental representation of emotional experience, how they can be measured, and whether they can be improved. We return to this point in the construct synthesis section, below.

Illustrating Relationships Between Constructs

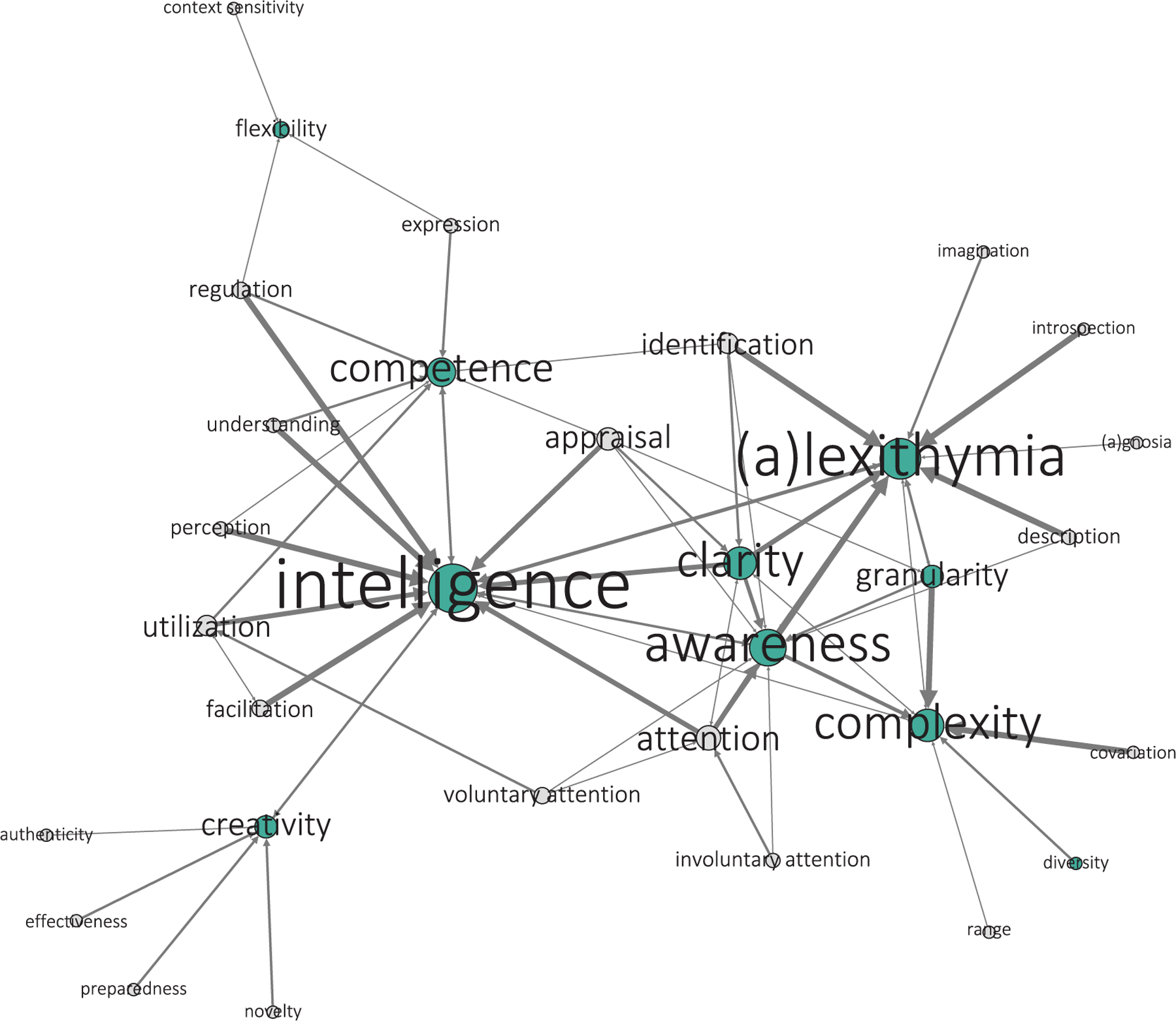

Conceptual Relationships

Figure 3 provides a descriptive network illustration of the conceptual interrelationships between constructs and their facets as they are defined in the published literature. Nodes corresponding to constructs are teal, while nodes corresponding to facets are light gray; for clarity of viewing (and in keeping with Table 2), all nodes are labeled without modifiers (e.g., “emotion[al]”). Nodes and their labels are sized according to their number of connections. Connections linking a facet to a broader construct are indicated with an arrow directed at the construct; connections linking two “peer” constructs are indicated with an arrow at either end. Connections are weighted by the number of publications represented, from a scale of one (a single publication; thinnest lines) to five (five or more publications; thickest lines). Weights were capped at five to provide a representative sense of endorsement rates, while accounting for differences in publication selection for high-volume constructs such as alexithymia and intelligence. Finally, facets have been renamed to facilitate integration in the network. For example, source clarity (Boden & Berenbaum, 2011; Boden & Thompson, 2015; Cameron et al., 2013; Lischetzke & Eid, 2017) is referred to as “appraisal” to highlight connections to appraisal-theoretic perspectives as well as to other constructs such as competence (Scherer, 2007) and intelligence (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Furthermore, constructs and facets defined as inabilities have been conceptually inverted. For example, alexithymia is defined as “the inability to identify, describe, and introspect about one’s emotional experiences” (Aaron et al., 2018); when inverted as “(a)lexithymia”, these facets became the abilities of identification, description, and introspection.9 As identification was also a facet of awareness (Bagby et al., 2006; Boden & Thompson, 2015), clarity (Boden & Berenbaum, 2011; Lischetzke & Eid, 2017), and competence (Brasseur et al., 2013), this node could be connected accordingly.

Figure 3. Network Based on Conceptual Interrelationships Documented Between Constructs and Their Facets.

Note. Node color distinguishes constructs summarized in Table 2 (teal) from facets added during data extraction (light gray). Only publications by Taylor, Bagby, and colleagues (e.g., Bagby et al., 1994; Taylor et al., 1985) and Mayer, Salovey, and colleagues (e.g., Mayer et al., 2002; Salovey & Mayer, 1990) are represented for alexithymia and intelligence, respectively. For a version of this network including other definitions of these constructs, see Figure S1. Nodes and their labels are sized according to their number of connections (i.e., degree). Facets are connected to broader constructs with an arrow directed at the construct; constructs are connected to each other with an arrow at both ends. Connections are weighted counts of the number of publications represented, such that the thinnest lines represent a single publication, and the thickest lines represent five or more publications. Nodes renamed from the original publications to facilitate integration: “granularity” also refers to differentiation (e.g., Barrett et al., 2001); “covariation” also refers to dialecticism (e.g., Grossmann et al., 2016); “regulation” also refers to repair (Salovey et al., 1995); “appraisal” also refers to source clarity (e.g., Boden & Berenbaum, 2011); “identification” also refers to type clarity (e.g., Boden & Berenbaum, 2011); “voluntary attention” (e.g., Boden & Thompson, 2015) also refers to redirected attention (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Facets noting the use of language to verbalize emotion (e.g., labeling; Swinkels & Giuliano, 1995) are referred to as “description” (following Bagby et al., 1994). Nodes conceptually inverted: “(a)gnosia”; “(a)lexithymia” and its facets identification, description, introspection (vs. externally oriented thinking), and imagination (vs. reduced fantasy). Network visualization created in Gephi (Bastian et al., 2009) using the Yifan Hu Proportional layout (Hu, 2005).

Across the network, connections between constructs reflect underlying relationships between subdomains, research groups, and theoretical perspectives. Missing connections between constructs at the periphery reflect, then, opportunities for conceptual integration. For example, we observed that the constructs of flexibility and diversity shared fewer connections with their neighboring constructs (i.e., their nodes were smaller): flexibility was indirectly connected to competence (via the facets of regulation and expression), and diversity was only directly connected to complexity. In contrast, the constructs of intelligence, (a)lexithymia, awareness, and clarity had many complex connections (i.e., their nodes were larger and connected by thick lines to multiple other nodes). These constructs were directly linked to each other and indirectly linked via the facets of appraisal, attention, and identification. In other words, these constructs were often described as separate but related and were conceptualized with overlapping features.

Broadly, we interpret the network in Figure 3 as depicting several interrelated clusters of constructs with intelligence, (a)lexithymia, and awareness/clarity as hubs. The intelligence cluster was the largest and included constructs oriented toward applied contexts, such as competence and flexibility. Creativity also formed a part of this cluster, although as a satellite of intelligence; this relationship reflects the theoretical context in which creativity was introduced as a constructionist alternative to intelligence (e.g., Averill, 2004; Ivcevic et al., 2007). The (a)lexithymia cluster, the second largest, evidenced its clinical origins through the neurological construct of (a)gnosia (Lane et al., 2015), and facets derived from the psychoanalytic tradition such as introspection (i.e., the inverse of externally oriented thinking) and imagination (i.e., the inverse of reduced fantasy). Still, this cluster had many nodes in common with the awareness/clarity cluster, which bridges clinical application with a basic science interest in describing the mental representation of emotional experience (e.g., voluntary vs. involuntary attention; Huang et al., 2013; source vs. type clarity; Boden & Berenbaum, 2011). This descriptive emphasis is shared by the complexity cluster, whose constructs additionally seek to capture individual differences across the lifespan (e.g., Grühn et al., 2013) and across cultures (e.g., Grossmann et al., 2016). Granularity did not have a clear cluster membership; it shared a strong connection with complexity but was also situated between (a)lexithymia and awareness.

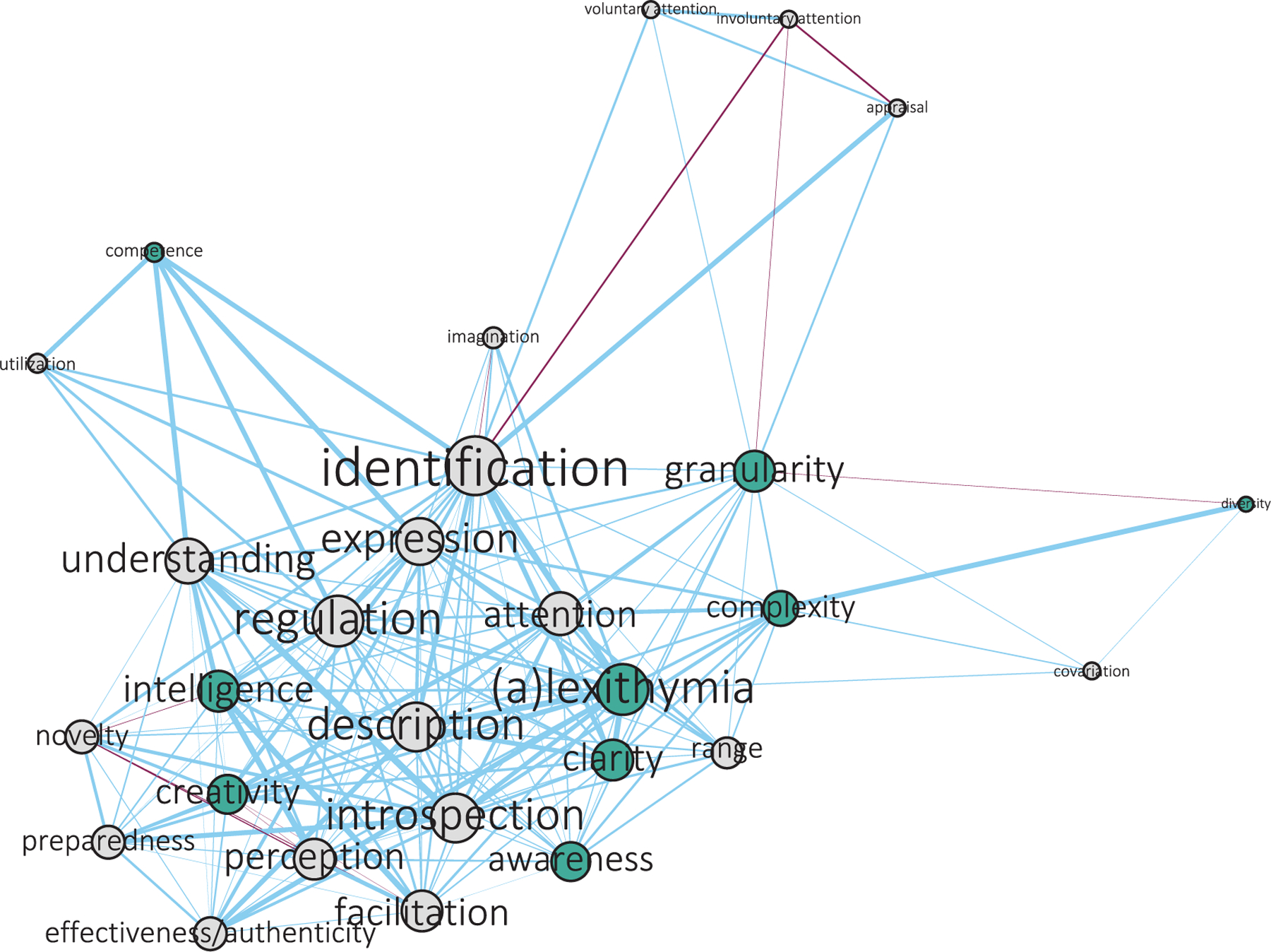

Empirical Relationships

Figure 4 provides a descriptive network illustration of the empirical interrelationships between constructs. As in Figure 3, constructs are represented by teal nodes, facets by light gray nodes, and nodes are sized by their number of connections. In this network, however, connections between nodes represent statistical relationships (i.e., correlations) between the constructs/facets, regardless of the measure used to collect these data. The connections represent mean effect sizes (r) of all reported correlations and are colored according to the direction of correlation (blue for positive, purple for negative). Importantly, because (a)lexthymia and its facets were conceptually inverted, so were corresponding connections: publications documenting negative correlations between alexithymia and intelligence (e.g., Parker et al., 2001), for example, are displayed as positive (blue) connections between the two nodes. Additionally, the network layout was structured using the strength of the mean effect sizes. Connections are undirected (i.e., there are no arrows), denoting bidirectional relationships.

Figure 4. Network Based on Empirical Interrelationships Documented Between Constructs and Their Facets.

Note. Node color distinguishes constructs summarized in Table 2 (teal) from facets added during data extraction (light gray). Connection color distinguishes direction of correlation (blue for positive, purple for negative). Only publications by Taylor, Bagby, and colleagues (e.g., Bagby et al., 1994; Taylor et al., 1985) and Mayer, Salovey, and colleagues (e.g., Mayer et al., 2002; Salovey & Mayer, 1990) are represented for alexithymia and intelligence, respectively. For a version of this network including other definitions and measures of these constructs, see Figure S2. Connections are undirected. The network is structured according to the strength of the mean effect sizes. Nodes renamed from the original publications to facilitate integration: “granularity” also refers to differentiation (e.g., Barrett et al., 2001); “covariation” also refers to dialecticism (e.g., Grossmann et al., 2016); “regulation” also refers to repair (Salovey et al., 1995); “appraisal” also refers to source clarity (e.g., Boden & Berenbaum, 2011); “identification” also refers to type clarity (e.g., Boden & Berenbaum, 2011); “voluntary attention” (e.g., Boden & Thompson, 2015) also refers to redirected attention (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Facets noting the use of language to verbalize emotion (e.g., labeling; Swinkels & Giuliano, 1995) are referred to as “description” (following Bagby et al., 1994). Nodes conceptually inverted: “(a)gnosia”; “(a)lexithymia” and its facets identification, description, introspection (vs. externally oriented thinking), and imagination (vs. reduced fantasy). Network visualization created in Gephi (Bastian et al., 2009) using the Yifan Hu Proportional layout (Hu, 2005).

This network provides a high-level snapshot of how data are collected and analyzed in relation to the constructs reviewed. In Figure 3, conceptual connections between constructs were sparser and organized into several interrelated but distinguishable clusters. In Figure 4, empirical connections between constructs are numerous. Constructs were frequently compared against each other, even if they were not considered to be conceptually related. There were also a variety of comparisons made, although it was rare for more than two constructs to be compared within a single publication (cf. Lumley et al., 2005). Facets of (a)lexithymia and intelligence were dominant in this network, reflecting the ubiquity of their corresponding measures (e.g., TAS-20; Bagby et al., 1994: Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test [MSCEIT]; Mayer et al., 2002). The most common comparison (i.e., largest node) was with the facet of identification (shared by (a)lexithymia, awareness, clarity, and competence), emphasizing how important the ability to categorize emotional experience is for measuring multiple constructs. Several nodes—(a)gnosia, context-sensitivity, and flexibility—remained unconnected and therefore are not represented in this network. Also, note, however, that because our goal was to review a representative rather than comprehensive set of publications, it is likely that there are missing comparisons—particularly for the high-volume constructs of alexithymia and intelligence.

This network suggests overlap in what constructs measure and, from this perspective, lends credibility to our proposal to integrate these constructs within a unifying framework. The overall relationship, after inverting (a)lexithymia, is positive; negative correlations are few and generally weak. Nodes generally form one cluster, except for constructs such as diversity and competence whose measures were less often compared in the publications we reviewed. This observation builds on prior meta-analytic comparisons of common measures for (a)lexithymia (TAS-20) and awareness (LEAS; Maroti et al., 2018) and on studies comparing multiple constructs and measures for each (e.g., Gohm & Clore, 2002; Ivcevic et al., 2007; Kang & Shaver, 2004; Lumley et al., 2005). These studies have found positive, small effect-size relationships between measures, which researchers have typically interpreted as discriminant validity for the constructs in question. For example, a significant but weak meta-analytic correlation of r = .12 was used to argue that (a)lexithymia and awareness were separate but related (Maroti et al., 2018). Figure 4 situates these findings with respect to a larger network, emphasizing the similarity of these constructs when viewed from a higher level. Nonetheless, the interpretation of correlation strength also depends upon the conceptual model used to structure a given domain (Bollen & Lennox, 1991), a point to which we return in the discussion.

Synthesizing Constructs Based on Features of Expertise

Figure 5 presents the set of 12 features hypothesized to constitute expertise in emotion, as determined deductively from accounts of domain-general expertise. These features are presented in the same order as in Table 1. The polar plot summarizes which features are represented by the constructs included in this review, as determined inductively from definitions, measures, and notes extracted from the selected publications. Features are plotted along radial lines, with constructs plotted along concentric circles in alphabetical order from (a)lexithymia (the innermost circle) to intelligence (the outermost circle). Data points indicate where a feature is present; in cases of disagreement or conflicting accounts within the literature, the data point is not filled (see Table S5 for example publications in support of each point).

Figure 5. Features of Expertise in Emotion, as Determined Deductively From Accounts of Domain-General Expertise.

Note. For an alternative presentation of these data, see Table S5. Features are plotted along radial lines, with constructs plotted along concentric circles in alphabetical order from (a)lexithymia (the innermost circle) to intelligence (the outermost circle). Data points indicate where a feature is present; in cases of disagreement or conflicting accounts within the literature, the data point is not filled.

Overall, in Figure 5 we see a many-to-many (rather than one-to-one) mapping between constructs and features. Two things are especially noteworthy. First, features varied in the number of constructs in which they were present. Every construct satisfied the feature of mental representation. This is by design, as this feature was a conceptual prerequisite for inclusion in our review. Other than the criterion, however, there is no single feature that is present in all constructs. Some aspects of the feature space are underrepresented. Second, constructs varied in the number of features they covered. Intelligence, granularity, and creativity were the most comprehensive, while flexibility and diversity were the least. However, more comprehensive constructs were not necessarily consistent in the features they covered. Moreover, the number of features covered by a construct is not intended as an index of quality or utility: As we discuss next, the presence of features was largely driven by underlying theoretical assumptions about the nature of emotions and methods of measurement.

One of the primary dimensions on which constructs differed is the nature of the conceptual knowledge underlying the mental representation of emotional experience. Most construct definitions explicitly acknowledged that knowledge or “mental content” is a central feature of expertise. The majority of constructs specified something about the structure (i.e., quality) of knowledge: granularity, for example, required emotion concepts (i.e., accrued knowledge and experience) to be nuanced and precise (e.g., Barrett et al., 2001; Tugade et al., 2004), while complexity emphasized high-dimensionality (e.g., Carstensen et al., 2000; Ong et al., 2017) and creativity underscored person-specificity (e.g., Averill, 1999; Fuchs et al., 2007). Creativity and granularity—along with diversity and complexity—also highlighted the breadth of knowledge supporting emotional experience. In the case of diversity and complexity, this could be seen in the emphasis on range (e.g., Kang & Shaver, 2004; Quoidbach et al., 2014). For creativity, breadth was captured by an emphasis on novelty (e.g., Averill, 1999; Ivcevic et al., 2017), whereas for granularity breadth was implied by having emotion concepts that are specific rather than overlapping (thereby covering more conceptual “space”; Barrett, 2017a).

Instead of speaking to the structure or breadth of knowledge, work on intelligence and competence focused on the type of knowledge. That is, these constructs followed the assumption (from basic and/or causal appraisal accounts of emotion) that one could be “correct” or “incorrect” in one’s knowledge—and that accuracy was critical for expertise (e.g., Izard et al., 2011; Mayer & Salovey, 1997; Scherer, 2007). By these accounts, having more, or differently structured, knowledge does not necessarily enhance expertise, if one does not already know the specific things one should know about emotions, such as their (evolutionarily endowed) forms and functions (e.g., Izard, 2009; Salovey & Mayer, 1990; Scherer, 2007).

Another primary dimension of expertise in emotion was whether it was considered an ability or skill versus a trait. Four of the 10 constructs we reviewed were conceptualized predominantly as abilities or skills: competence (e.g., Brasseur et al., 2013), creativity (e.g., Averill, 1999), granularity (e.g., Kashdan et al., 2015), and intelligence (e.g., Mayer et al., 2000).10 Ability models broadly assumed that expertise is not a latent capacity, but something that is continually acquired throughout the lifespan and can be actively improved (e.g., Kashdan et al., 2015; Mayer et al., 2016). In contrast, five constructs were described, either implicitly or explicitly, as traits: (a)lexithymia, awareness, clarity, complexity, and diversity. Awareness (e.g., Lane & Schwartz, 1992) and complexity (e.g., Lindquist & Barrett, 2008) have alternatively been conceptualized as abilities or skills.

Three features captured the types of behaviors that indicate expertise. By most accounts, verbal representation of emotional experience provides key—if not unparalleled—insight into mental representation. “Verbal representation” included the identification (i.e., labeling) and description of emotion, and formed a central part of (a)lexithymia (e.g., Bermond et al., 1999; Sifneos, 1973; Taylor, 1984), awareness (e.g., Lane & Schwartz, 1987; Swinkels & Giuliano, 1995; Thompson et al., 2009), clarity (e.g., Boden & Thompson, 2017; Lischetzke & Eid, 2017), and granularity (e.g., Barrett, 2004; Lee et al., 2017). The appropriate (i.e., normative) use of language was also included in some conceptualizations of competence (e.g., Scherer, 2007) and intelligence (e.g., Ivcevic et al., 2007).

Adaptive responses were a further concomitant of competence, creativity, granularity, and intelligence, although these constructs differed in their understanding of “adaptive.” As noted above, measures of competence and intelligence tended to assume universal or at least strongly normative operationalizations of emotional behaviors (e.g., Izard, 2009; Mayer et al., 2000). These constructs also assumed that expertise should meet criteria that are more-or-less context-invariant (e.g., Averill, 2004; Petrides, 2010), with these criteria taken from hypotheses about evolutionarily endowed forms and functions (e.g., Izard, 2009; Scherer, 2007), established by a panel of emotion researchers (Mayer et al., 2000), or derived from a sample of U.S. participants (Mayer et al., 2000). In all cases, there was an assumption of a single “best” way to respond, with individual variability in response considered an undesirable deviation from this norm.11

By comparison, constructs such as complexity, creativity, and granularity stressed context-sensitivity in assessment and interpretation (e.g., Averill, 1999; Kashdan et al., 2015; Lindquist & Barrett, 2008). The cross-cutting assumption—based largely on constructionist and descriptive appraisal perspectives—was that expertise is a relative rather than absolute measure, and varies naturally as a function of culturally, personally, and situationally relevant goals and constraints (e.g., Averill, 1999; Barrett, 2017a).

Two features related to how expertise shapes emotional experience. Most constructs specified that expertise included awareness of emotion—that individuals consciously represent and navigate emotional experience (e.g., Lane & Schwartz, 1987; Subic-Wrana et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2009). Granularity was a notable exception to this trend. Although the measurement of granularity invokes the use of verbal representation (which requires conscious access), the experience of granular emotions does not per se require subjective awareness (Barrett, 2017a, 2017b; see also Lambie & Marcel, 2002). Constructs such as (a)lexithymia and awareness expanded subjective awareness further to include attention to emotions. This attention can take the form of active scanning or monitoring (e.g., Coffey et al., 2003; Gohm & Clore, 2002; Salovey et al., 1995; Swinkels & Giuliano, 1995) or of introspection or internally oriented thought (e.g., Marty & de M’Uzan, 1963; Taylor et al., 1985), and can be voluntary or involuntary (e.g., Boden & Thompson, 2015; Elfenbein & MacCann, 2017).12

Two final features related to how expertise is acquired and implemented. Many accounts of domain-general expertise speak to its acquisition via deliberate practice (e.g., Ullén et al., 2016). The only constructs to explicitly advocate for such an approach to emotion were creativity and granularity. With its facet of “preparedness,” creativity directly tapped the intuition that individuals develop expertise through intentional engagement with and reflection upon their emotions (Averill, 1999). Similarly, individuals can improve their granularity by being “collectors of experience” (Barrett, 2017a), seeking out new ways to expand their perspective and gain new, more nuanced concepts. Granularity further emphasized that these new concepts lead to improved prediction (Barrett, 2017a). Individuals with greater expertise are more skilled at using their knowledge and can better anticipate and adjust to upcoming challenges. While constructs such as creativity and flexibility did emphasize context-sensitivity, as discussed above, they did not capture the proactive planning accounted for by prediction. Prediction was also discussed in some accounts of (a)lexithymia (Lane et al., 2015) and complexity (Lindquist & Barrett, 2008).

Discussion

The idea that some people are better or worse than others at understanding and experiencing emotions is widely held. Decades of research support the existence of individual differences in emotional competencies, with thousands of studies demonstrating the various ways in which individuals can excel or be deficient, and the downstream consequences of these individual differences for mental health, physical health, and other real-world outcomes. Yet, the volume of research and variety of individual differences can also be a hindrance to scientific discovery and practical application. There are dozens of psychological constructs (and an even greater number of measures) pertaining to individual differences in the mental representation of emotional experience, and research on these constructs is often found in separate literature with separate audiences, research goals, and theoretical assumptions.

In the present article, we have proposed a means to integrate these constructs within a unifying framework based on features of domain-general expertise. Through a scoping review procedure, we conducted an iterative and systematic review of the literature. We identified 10 core constructs: alexithymia, awareness, clarity, complexity, competence, creativity, diversity, flexibility, granularity, and intelligence. For each construct, we interrogated a representative set of publications to determine the features of expertise represented, the primary methods of measurement, and their underlying theoretical perspectives. We also situated constructs with respect to each other in terms of definition and measurement, illustrating conceptual and empirical relationships using networks. Finally, we remapped constructs to a set of deductively generated features for expertise so that we could compare them. Throughout this process, we observed overlaps, gaps, and inconsistencies in construct definition and measurement that provide insight into the nature of expertise in emotion as it pertains to the mental representation of emotional experience. These findings provide a framework for interpreting a broader set of emotion-related individual differences and have implications for future research.

Scoping Review Summary

We created an expertise framework for emotion as a means of querying and comparing constructs in this domain. Returning to the opening analogy of the blind men and the elephant, our intention was to integrate a diverse set of individual differences so that we could describe the different parts and examine how (and if) they all fit together. We explored the nomological network for the mental representation of emotional experience by illustrating the relationships between constructs. The conceptual network, based primarily on construct definitions, reflected the motivations of theorists. The connections in this network revealed a body of research with several interrelated clusters of constructs, anchored by intelligence, alexithymia, and awareness and clarity. We interpret these clusters as evidence of the conceptual splintering or rediscovery that has produced the different “parts of the elephant.” This splintering was not as evident, however, when we examined the empirical connections between constructs as measured. Instead, the web of correlations between these constructs and their facets suggested broad overlap across the network—that these constructs may be part of the same elephant, even if they do differ in some way or another.

We explored the nature of these conceptual differences by analyzing the features of expertise represented by each construct. We identified several features that were shared by many of the surveyed constructs, beyond the feature that served as an inclusion criterion (i.e., mental representation). Among the major commonalities were that experts are consciously aware of their experiences and that experts use specific language to verbally represent them. In line with domain-general accounts, expertise in emotion was often seen as an ability or skill. There were also clear distinctions. Perhaps the most notable was between constructs that focus on types of knowledge and normative or stipulated responses in determining expertise, such as competence and intelligence, and those that focus on the structure of the knowledge and context-sensitivity of the response, such as creativity and granularity. These differences were often rooted in theoretical assumptions about emotion—such as the contrast we highlighted between the basic emotion and causal appraisal accounts that ground competence and intelligence and constructionist accounts that ground creativity and granularity. Differences between constructs were also influenced by other motivating factors, such as the goals of a program of research (e.g., to help managers work with personnel, to help clinicians treat patients, to better understand underlying mechanisms).

There are some useful general observations that we can make from this work. In both our network- and feature-based analyses, we observed that certain constructs are more central to this domain than others. Flexibility and diversity, for instance, may be peripheral constructs. It is possible that these constructs have less support because they are backed by less literature. It is also possible that these constructs are less representative of expertise in emotion. Likewise, we “zoomed in on” only one portion of a much larger nomological network of constructs related to individual differences in emotional competencies. As such, the connections between our subnetwork and its neighboring networks are not visible. For example, we excluded constructs that dealt exclusively with the perception, expression, and regulation of emotion. Yet, these processes emerged as facets of competence (e.g., Brasseur et al., 2013), flexibility (e.g., Fu et al., 2018), and intelligence (e.g., Mayer & Salovey, 1997). We interpret this as an indication of the overlap between a set of interrelated bodies of research.

Limitations

Although we sought to integrate across many different emotional competencies, there are necessary limits on the scope of this work. A more comprehensive account of expertise in emotion would also include constructs related to the regulation of emotion in oneself (e.g., coping, control), those related to the representation of others’ emotional experiences (e.g., recognition, empathy), and those related to the management of emotion in others (e.g., capital, attunement; see Table S2). It may further include research on affective dynamics, changes across the lifespan, and disordered emotional health. We conceptualize the understanding and management of emotions as an umbrella, the exact structure of which should be determined through systematic review and synthesis of relevant constructs. In this regard, we echo prior work that has conceptualized emotional intelligence as a broad, multifaceted domain (e.g., Bar-On, 1997; Elfenbein & MacCann, 2017; Palmer et al., 2008; Tett et al., 2005). In their initial 1990 publication, Salovey and Mayer proposed a taxonomic framework for emotional intelligence as a set of skills related to emotion in oneself and others. Here, we have built upon this framework by introducing a set of domain-general features that provide a basis for interpretation of expertise in emotion writ broadly.