Abstract

Objective

This study explored how various markers of objective and subjective socioeconomic status (SES) are associated with cognitive impairment among older Indian adults.

Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted using large nationally representative survey data.

Setting and participant

This study used data from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (2017–2018). The sample included 31 464 older adults aged 60 years and above.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Outcome variable was cognitive impairment, measured through broad domains of memory, orientation, arithmetic function, and visuo-spatial and constructive skills. We estimated descriptive statistics and presented cross-tabulations of the outcome. Χ2 test was used to evaluate the significance level of differences in cognitive impairment by subjective (ladder) and objective SES measures (monthly per-capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) quintile, education and caste status). Multivariable linear and logistic regression analyses were conducted to fulfil the objectives.

Results

A proportion of 41.7% and 43.4% of older adults belonged to low subjective (ladder) and objective (MPCE) SES, respectively. Older adults with low subjective (adjusted OR (aOR): 2.04; p<0.05) and objective SES (aOR: 1.32; p<0.05) had higher odds of having cognitive impairment in comparison with their counterparts, with a stronger subjective SES–cognitive impairment association. Older adults with lower education or belonged to lower caste had higher odds of cognitive impairment than their counterparts. Interaction analyses revealed that older adults who belonged to lower subjective and objective (poorest MPCE quintile, Scheduled Castes and lowest education) SES had 2.45 (CI: 1.77 to 3.39), 4.56 (CI: 2.97 to 6.98) and 54.41 (CI: 7.61 to 388.93) higher odds of cognitive impairment than those from higher subjective and objective SES, respectively.

Conclusion

Subjective measures of SES were linked to cognitive outcomes, even more strongly than objective measures of SES; considering the relative ease of obtaining such measures, subjective SES measures are a promising target for future study on socioeconomic indicators of cognitive impairment.

Keywords: old age psychiatry, delirium & cognitive disorders, mental health, economics

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The study uses a large nationally representative sample of older persons from both rural and urban areas of India.

The cross-sectional design of the study eliminates the opportunity for drawing of causal inferences among variables.

Some individuals may become cognitively impaired because they are illiterate and could not respond with accuracy to several measures.

Introduction

Cognitive impairment, including dementia as an outcome of decline in cognitive ability, increases considerably with the rapidly growing population of older adults.1 Worldwide, almost 80% of the general public are concerned about developing dementia at some point in time and one in four people think that they can do nothing to prevent such a cognitive decline.2

Various indices of economic hardship, including lack of education, poor household economy, unemployment and employment frustration, are linked with poor physical health conditions resulting in cognitive deficits.3–5 Similarly, evidence suggests an aggregate or cumulative effect of socioeconomic risk factors on cognitive impairment in later years of life.6–8 Persons with higher cumulative socioeconomic status (SES) demonstrated an advantage in cognitive functioning.9 A growing body of literature suggests that people who accumulated more wealth may be able to more easily translate it into better environmental circumstances or less stressful living conditions, further contributing to better cognitive health in later life.7 10 11 Studies reported improvements in mental well-being for older people after the introduction of an income supplemental programme.12 13 Measured by a test of processing speed, associations of educational attainment and current poverty index were found with late-life cognitive impairment in multiple studies.7 14 15 Furthermore, a major contributing factor may include poor literacy resulting in an inability to benefit from strategies for early prevention of cognitive impairment.16

Two approaches to SES: subjective and objective SES measures

Objective SES is commonly indicated by household wealth index and individual educational attainment, and caste status in particular Indian context.17–19 Although these indicators are highly correlated,20 they reflect more of one’s power or prestige.21 In comparison, the subjective SES captures individuals’ perceptions of their position in the social hierarchy, thus representing a psychological process.22

In this regard, people make judgements of where they belong in the social hierarchy relative to others based on cognitive averaging of their economic status, education, occupation and other objective indicators using different reference groups.23 There is a growing body of research documenting that if people perceive themselves to be subordinate to others, they report lower self-esteem and greater stress, and they are likely to suffer from diseases more often than people who do not regard themselves to be of lower status.24 Hence, subjective SES as a rank-based judgement that is composed of an evaluative judgement whereas the objective resources would place a person in rank within a specific context, which is derived mainly via the social comparison process.

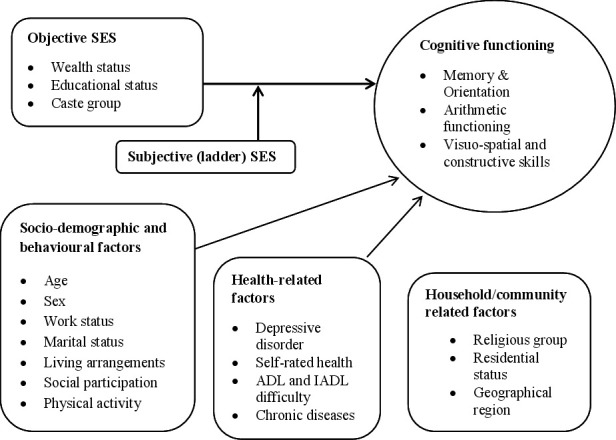

Evidence for the association between poor socioeconomic indicators with worse mental health outcomes is abundant in the geriatric research. Many previous studies in India and other countries have reinforced that illiteracy, lower social status and poor financial status were strongly associated with worse cognitive function at the individual level.1 25 26 Similarly, the association of subjective SES and physical and mental health of older adults is explored in a couple of studies in Asian countries.27 28 However, the difference in the role that subjective and objective socioeconomic factors play in contributing to declining in late-life cognition is poorly understood in the context of developing countries. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to explore the late-life cognitive impairment as a function of older individuals’ objective and subjective SES using a large representative survey information of older adults aged 60 years and above in India. A conceptual framework based on the above-mentioned theoretical background is summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework. ADL, activity of daily living; IADL, instrumental ADL; SES, socioeconomic status.

Data, variables and methods

Data source

We used data from the recent release of Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) wave 1.29 LASI is a full-scale national survey of scientific investigation of the health, economic, and social determinants and consequences of population ageing in India, conducted in 2017–2018. The LASI is a nationally representative survey of over 72 000 older adults aged 45 years and above across all states and union territories (UTs) of India. The survey adopted a three-stage sampling design in rural areas and a four-stage sampling design in urban areas. In each state/UT, the first stage involved the selection of Primary Sampling Units (PSUs), that is, subdistricts (Tehsils/Talukas), and the second stage involved the selection of villages in rural areas and wards in urban areas in the selected PSUs.29 In rural areas, households were selected from selected villages in the third stage. However, sampling in urban areas involved an additional stage. Specifically, in the third stage, one Census Enumeration Block (CEB) was randomly selected in each urban area.29 In the fourth stage, households were selected from this CEB. The detailed methodology, with the complete information on the survey design and data collection, is published elsewhere and in the survey report.29 30 The present study is conducted on eligible respondents aged 60 years and above (31 464 older individuals from both rural and urban areas).

Variable description

Outcome variable

Cognitive impairment was measured through broad domains of memory, orientation, arithmetic function, and visuo-spatial and constructive skills. It is followed from the cognitive module of the Health and Retirement Study, the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, and the Mexican Health and Aging Study, based on different cognitive measures including: immediate (0–10 points) and delayed word recall (0–10 points); orientation related to time (0–4 points) and place (0–4 points); arithmetic ability based on serial 7s (0–5 points), computation (0–2) and backward counting from 20 (0–2 points); visuo-spatial and constructive skills based on paper folding (0–3) and pentagon drawing (0–1); and object naming (0–2). The overall score ranged between 0 and 43, and a higher score indicated better cognitive functioning. The lowest 10th percentile was used as a proxy measure of poor cognitive functioning.29 Further, for the analytical purpose, the score was reversed to assess the cognitive impairment among older adults and thus after reversing, the higher score indicated higher levels of cognitive impairment. In our study, the respondents who received assistance during the cognition module were excluded from the analysis.

SES exposures

The main explanatory variables were subjective SES (ladder SES) and objective SES (household wealth quintile, education and caste status) among older adults.

The subjective SES was assessed using the Macarthur scale,31 with a ladder technique and the question used to assess the variable was ‘Think of the ladder with 10 stairs as representing where people stand in our society. At the top of the ladder are the people who are the best off—those who have the most money, most education and best jobs. At the bottom are the people who are the worst off—who have the least money, least education, and the worst jobs or no jobs. The higher up you are on this ladder, the closer you are to the people at the very top and the lower you are, the closer you are to the people at the very bottom of your society.’ The scale is used to measure the subjective SES across different populations in India and other countries.32 33 A score of 0–10 was generated as per the number of rungs marked by the respondents, and the variable of subjective SES was coded as 0–3 as ‘low’, 4–7 as ‘middle’ and 8–10 as ‘high’.34

The monthly per-capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) quintile was assessed using household consumption data. The MPCE was used as one of the measures of objective SES. Sets of 11 and 29 questions on the expenditures on food and non-food items, respectively, were used to canvas the consumption pattern of the sample households. Food expenditure was collected based on a reference period of 7 days, and non-food expenditure was collected based on reference periods of 30 days and 365 days. Food and non-food expenditures have been standardised to the 30-day reference period. The MPCE is computed and used as the summary measure of consumption.29 The available categories of the variable comprised of five quintiles, that is, poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest. Since keeping the actual categories would produce a large number of categories during the interaction analysis, MPCE was further recoded into three categories for easy interpretability and better understanding while applying the interaction terms. Thus, the MPCE quintile was further recoded as ‘low’ (poorest and poorer), ‘middle’ and ‘high’ (richer and richest).35

Another objective SES measure was educational status of older adults. As documented in multiple studies, brain functioning and cognitive processing are modulated by formal education of individuals and the illiterate population who received no formal education due to several sociocultural and economic reasons are at greater risk of cognitive impairment and dementias.36 The educational status in the current study was coded as no education/primary not completed, primary, secondary and higher. Finally, caste system in India is a social hierarchy that is passed down through families, and groups of people dictate the professions and social prestige merely by their caste status.19 As an objective SES measure, caste in the study was recoded as Scheduled Tribes, Scheduled Castes, Other Backward Classes and Others based on specific administrative classification.19 The Scheduled Caste includes a group of the population that is socially segregated and financially/economically marginalised by their low status as per Hindu caste hierarchy. The Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes are among the most disadvantaged socioeconomic groups and have substantially lower wealth than the ‘forward’ caste groups in India.37 The Other Backward Classes refer to the group of people who were identified as ‘educationally, economically and socially backward’ and occupy positions in the middle.38 The ‘Others’ caste category denotes the groups having higher social status and refers to a large number of the forward castes and comparatively advantaged populations in the country.38

Other covariates

Individual factors

The following sociodemographic variables were included in the analysis according to the previous literature sources that have shown their associations with the cognitive outcomes.39–42 Age was used as continuous variable. Sex was coded as male and female. Working status was coded as currently working, retired and not working. Marital status was coded as currently married, widowed and others. Others included divorced/separated/never married. Living arrangement was coded as living alone, living with spouse, living with spouse and children and living with others. Social participation was coded as ‘no’ and ‘yes’. Social participation was measured through the question ‘Are you a member of any of the organisations, religious groups, clubs or societies?’ The response was coded as ‘no’ and ‘yes’.43 Physical activity status was coded as frequent (every day), rare (more than once a week, once a week, one to three times in a month) and never. The question through which physical activity was assessed was ‘How often do you take part in sports or vigorous activities, such as running or jogging, swimming, going to a health centre or gym, cycling, or digging with a spade or shovel, heavy lifting, chopping, farm work, fast bicycling, cycling with loads?’44

Health-related factors

Health-related covariates that were shown to associate with cognitive impairment and are considered as possible confounders of the SES–cognition relationship in the current analyses include depression,42 self-rated health,45 functional difficulty46 and morbidity.47 The probable major depression among older adults with symptoms of dysphoria was calculated using the Short Form Composite International Diagnostic Interview. This scale estimates a probable psychiatric diagnosis of major depression and has been validated in field settings and widely used in population-based health surveys.29 On a scale of 0–10, the respondents who had three or more symptoms were considered as depressed.48 Self-rated health was available in a 5-point scale, representing excellent, very good, good, fair and poor.49 Difficulty in activities of daily living (ADLs) was coded as ‘no’ and ‘yes’. ADL refers to normal daily self-care activities (such as movement in bed, changing position from sitting to standing, feeding, bathing, dressing, grooming, personal hygiene, etc). The ability or inability to perform ADLs is used to measure a person’s functional status, especially in case of people with disabilities and the ones in their older ages.50 Difficulty in instrumental ADLs (IADLs) was coded as ‘no’ and ’yes’. Respondents were asked if they were having any difficulties that were expected to last more than 3 months, such as preparing a hot meal, shopping for groceries, making a telephone call, taking medications, doing work around the house or garden, managing money (such as paying bills and keeping track of expenses), and getting around or finding an address in unfamiliar places.43 Morbidity was coded as no morbidity, 1 and 2+.43 This variable was created using the data on chronic diseases which include hypertension, chronic heart diseases, stroke, any chronic lung disease, diabetes, cancer or malignant tumour, any bone/joint disease, neurological/psychiatric disease or high cholesterol.

Household/community-related factors

Taking cue from earlier research, we also added the following characteristics as control variables in order to improve the precision of the results.39 51 52 Religion was coded as Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Others. Place of residence was coded as rural and urban. The geographical regions of India were categorised as North, Central, East, Northeast, West and South.

Statistical analysis

We estimated descriptive statistics and presented cross-tabulations of the outcome in the study. Additionally, multivariable logistic and linear regression analyses53 54 were conducted to establish the association between the outcome variable (cognitive impairment) and SES. The results were presented in the form of OR, adjusted OR (aOR) and standardised regression coefficients (beta) with 95% CI. Variance inflation factor was generated in STATA V.1455 to check the multicollinearity, and it was found that there was no evidence of multicollinearity in the variables used.56 57

Moreover, interaction effects43 58 were observed for subjective SES and multiple objective SES measures with cognitive impairment among older adults in India. Model 1 represents the unadjusted effects, whereas model 2 represents the adjusted effects. The analysis was controlled for age, sex, working status, marital status, living arrangement, social participation, physical activity, depression, self-rated health, difficulty in ADLs and IADLs, morbidity, religion, place of residence and regions. Models 3, 4 and 5 represent interaction effects which are adjusted for individual, health and household/community-related factors.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

Table 1 represents socioeconomic and demographic profile of older Indian adults included in this study. The mean age of the study population was 69.2 years (SD: 7.5). It was found that about 41.7% of older adults belong to low subjective SES and only 7% belong to higher subjective SES. Additionally, about 43.4% of older adults belonged to low objective SES and about 35.6% belonged to higher objective SES. About 13.1% (n=3250) of older adults were cognitively impaired in reference to 86.9% (n=21 580) who were not cognitively impaired.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic and demographic profile of older adults in India

| Background characteristics | Sample | Percentage |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | ||

| Subjective SES | ||

| Ladder SES | ||

| Low | 13 127 | 41.7 |

| Medium | 16 142 | 51.3 |

| High | 2195 | 7.0 |

| Objective SES | ||

| MPCE quintile | ||

| Low | 13 660 | 43.4 |

| Medium | 6590 | 21.0 |

| High | 11 213 | 35.6 |

| Education | ||

| Not educated/primary not completed | 21 381 | 68.0 |

| Primary | 3520 | 11.2 |

| Secondary | 4371 | 13.9 |

| Higher | 2191 | 7.0 |

| Caste | ||

| Scheduled Castes | 5949 | 18.9 |

| Scheduled Tribes | 2556 | 8.1 |

| Other Backward Classes | 14 231 | 45.2 |

| Others | 8729 | 27.7 |

| Individual characteristics | ||

| Age in years (mean (SD)) | 69.2 (7.5) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 14 931 | 47.5 |

| Female | 16 533 | 52.6 |

| Working status | ||

| Working | 9680 | 30.8 |

| Retired | 13 470 | 42.8 |

| Not working | 8314 | 26.4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Currently married | 19 391 | 61.6 |

| Widowed | 11 389 | 36.2 |

| Others | 684 | 2.2 |

| Living arrangement | ||

| Living alone | 1787 | 5.7 |

| Living with spouse only | 6397 | 20.3 |

| Living with children and spouse | 21 475 | 68.3 |

| Living with others | 1805 | 5.7 |

| Social participation | ||

| No | 30 053 | 95.5 |

| Yes | 1411 | 4.5 |

| Physical activity | ||

| Frequent | 5651 | 18.0 |

| Rarely | 4023 | 12.8 |

| Never | 21 790 | 69.3 |

| Health factors | ||

| Depression* | ||

| No | 27 995 | 91.3 |

| Yes | 2657 | 8.7 |

| Self-rated health* | ||

| Excellent | 964 | 3.1 |

| Very good | 4192 | 13.6 |

| Good | 10 693 | 34.7 |

| Fair | 10 331 | 33.5 |

| Poor | 4630 | 15.0 |

| Difficulty in ADLs | ||

| No | 23 802 | 75.7 |

| Yes | 7662 | 24.4 |

| Difficulty in IADLs | ||

| No | 16 130 | 51.3 |

| Yes | 15 334 | 48.7 |

| Morbidity | ||

| No morbidity | 14 773 | 47.0 |

| 1 | 9171 | 29.2 |

| 2+ | 7520 | 23.9 |

| Household/community-related factors | ||

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 25 871 | 82.2 |

| Muslim | 3548 | 11.3 |

| Christian | 900 | 2.9 |

| Others | 1145 | 3.6 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Rural | 22 196 | 70.6 |

| Urban | 9268 | 29.5 |

| Region | ||

| North | 3960 | 12.6 |

| Central | 6593 | 21.0 |

| East | 7439 | 23.6 |

| Northeast | 935 | 3.0 |

| West | 5401 | 17.2 |

| South | 7136 | 22.7 |

| Total | 31 464 | 100.0 |

*If sample may be less due to missing cases.

ADLs, activities of daily living; IADLs, instrumental ADLs; MPCE, monthly per-capita consumption expenditure.

About 26.4% of older adults got retired from employment and 30.8% were currently working. Nearly 36.2% of older adults were widowed. Only 5.7% of older adults were living alone and 68.3% were living with their children and spouse. Only 4.5% of older adults reported that they socially participate. Nearly 69.3% of older adults were never involved in any physical activity. About 8.7% of older adults suffered from major depression. Nearly 15.0% of older adults reported poor self-rated health. About 24.4% and 48.7% of older adults reported difficulty in ADLs and IADLs.

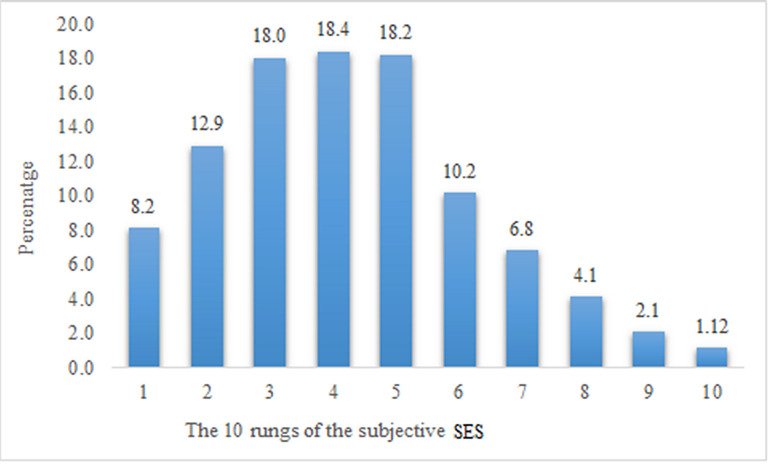

Figure 2 presents the percentage distribution of subjective SES (ladder SES) that ranges from 1 to 10, representing lowest to highest rank. A proportion of 8.2% of older adults marked their SES in the bottom of the ladder (lowest), whereas a proportion of only 1.1% marked their SES at the top of the ladder (highest).

Figure 2.

The distribution of the subjective socioeconomic status (SES) (1–10: lowest to highest rank).

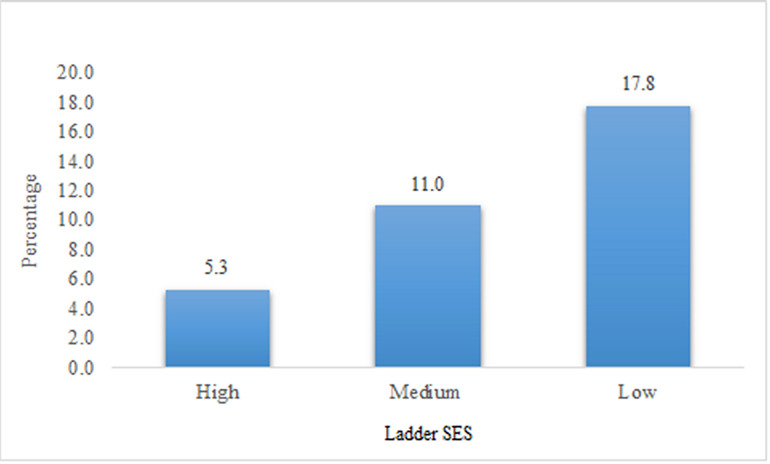

Figure 3 reveals that the lower the subjective SES (17.8%; p<0.001) of an older adult, the higher the prevalence of cognitive impairment.

Figure 3.

Percentage of older adults with cognitive impairment by their subjective socioeconomic status (SES).

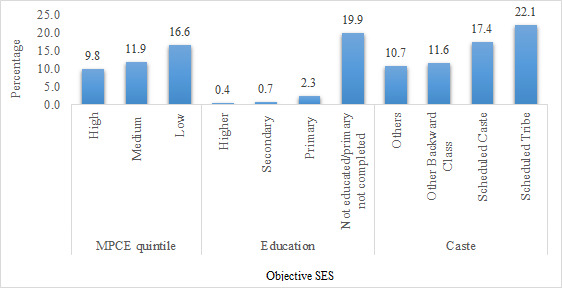

Figure 4 reveals that the lower the objective SES (measured by MPCE quintile) (16.6%; p<0.001) of an older adult, the higher the prevalence of cognitive impairment. With regard to other objective SES measures, older adults with no education/primary not completed had highest prevalence of cognitive impairment (19.9%; p<0.001). Similarly, older adults from Scheduled Tribe category had highest prevalence of cognitive impairment (22.1%; p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Percentage of older adults with cognitive impairment by their objective socioeconomic status (SES). MPCE, monthly per-capita consumption expenditure.

Table 2 represents the logistic regression estimates of cognitive impairment among older adults. In model 2, which is an adjusted model, it was revealed that older adults who belonged to lower subjective SES had significantly higher odds of cognitive impairment (aOR: 2.04; p<0.05) in reference to older adults who belonged to higher subjective SES. Moreover, older adults who belonged to lower objective SES (MPCE quintile) had 32% significantly higher odds of suffering from cognitive impairment (aOR: 1.32; p<0.05) in comparison with older adults who belonged to higher objective SES (MPCE quintile). Older adults who were not educated/with minimum education had significantly higher odds of cognitive impairment in reference to older adults with higher education (aOR: 22.4; p<0.05). Older adults who belonged to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes had 22% (aOR: 1.22; p<0.05) and 80% (aOR: 1.80; p<0.05) significantly higher odds of cognitive impairment in reference to older adults from other (higher) caste category, respectively. Online supplemental table 1 represents the regression estimates for cognitive impairment among older adults in India. In online supplemental table 2, model 1 included subjective SES and individual, health and household factors; model 2 included MPCE quintile and individual, health and household factors; model 3 included education and individual, health and household factors; and model 4 included caste and individual, health and household factors. These separate models for each aspect of SES also showed the similar pattern and odds of cognitive impairment were even greater in case of older adults who were not educated/with minimum education. Online supplemental table 2 represents sensitivity analysis estimates (aORs) of cognitive impairment among older adults when the outcome variable, that is, cognitive impairment, was adjusted for education (lowest 10th percentile of each educational category was considered cognitively impaired, that is, with a cut-off score of 14 for no educated/primary not completed, 21 for primary, 24 for secondary and 27 for higher education groups). The results showed no changes in the observed associations and the pattern remained the same for all the subjective and objective SES measures, except education.

Table 2.

Regression estimates for cognitive impairment among older adults in India, 2017–2018

| Background characteristics | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| OR (95% CI) | Standardised beta | aOR (95% CI) | Standardised beta | |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | ||||

| Subjective SES | ||||

| Ladder SES | ||||

| High | Reference | Reference | ||

| Medium | 2.01* (1.63 to 2.47) | 0.107 | 1.43* (1.14 to 1.79) | 0.102 |

| Low | 3.83* (3.11 to 4.71) | 0.172 | 2.04* (1.63 to 2.56) | 0.157 |

| Objective SES | ||||

| MPCE quintile | ||||

| High | Reference | Reference | ||

| Medium | 1.20* (1.07 to 1.34) | 0.011 | 1.12 (0.99 to 1.26) | 0.020 |

| Low | 1.50* (1.37 to 1.64) | 0.032 | 1.32*(1.19 to 1.46) | 0.051 |

| Education | ||||

| Not educated/primary not completed | 58.91* (27.97 to 124.07) | 0.694 | 22.40* (10.58 to 47.41) | 0.514 |

| Primary | 6.45* (2.96 to 14.03) | 0.204 | 3.83* (1.75 to 8.36) | 0.142 |

| Secondary | 2.55* (1.13 to 5.73) | 0.108 | 1.94 (0.86 to 4.38) | 0.072 |

| Higher | Reference | Reference | ||

| Caste | ||||

| Scheduled Castes | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.16) | 0.005 | 1.22* (1.06 to 1.39) | 0.027 |

| Scheduled Tribes | 1.38* (1.22 to 1.55) | 0.029 | 1.80* (1.55 to 2.09) | 0.067 |

| Other Backward Classes | 0.86* (0.78 to 0.96) | −0.038 | 0.98 (0.87 to 1.1) | −0.005 |

| Others | Reference | Reference | ||

Model 2 was adjusted for individual, health and household factors.

*if p<0.05

aOR, adjusted OR; MPCE, monthly per-capita consumption expenditure.

bmjopen-2021-052501supp001.pdf (45.3KB, pdf)

In models 3, 4 and 5 (table 3), which reveal the interaction results for cognitive impairment, it was found that older adults who belong to lower subjective as well as objective SES were 2.45 times significantly more likely to suffer from cognitive impairment in reference to older adults from higher subjective as well as objective SES (MPCE quintile) (aOR: 2.45; p<0.05). In reference to older adults with high ladder SES and higher education, older adults with high ladder SES and no education/primary not completed (aOR: 24.14; p<0.05), middle ladder SES and no education/primary not completed (aOR: 37.07; p<0.05) and low ladder SES and no education/primary not completed (aOR: 54.41; p<0.05) had significantly higher odds of cognitive impairment. Older adults from low ladder SES and belonged to the Scheduled Castes (aOR: 2.88; p<0.05), low ladder SES and belonged to the Scheduled Tribes (aOR: 4.56; p<0.05) and low ladder SES and belonged to the Other Backward Classes (aOR: 2.15; p<0.05) had significantly higher odds of cognitive impairment in reference to older adults from high ladder SES and other (higher) caste category. Online supplemental table 3 represents sensitivity analysis estimates (interaction models) for cognitive impairment among older adults after adjusting for education, and the results indicated towards similar findings.

Table 3.

Interaction estimates for cognitive impairment among older adults in India, 2017–2018

| Background characteristics | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||

| aOR (95% CI) | Standardised beta | aOR (95% CI) | Standardised beta | aOR (95% CI) | Standardised beta | |

| Ladder SES # MPCE quintile | ||||||

| High # high | Reference | |||||

| High # middle | 1.28 (0.92 to 1.77) | 0.085 | ||||

| High # low | 1.95* (1.39 to 2.72) | 0.102 | ||||

| Middle # high | 0.79 (0.42 to 1.48) | 0.008 | ||||

| Middle # middle | 1.51* (1.08 to 2.11) | 0.084 | ||||

| Middle # low | 2.09* (1.49 to 2.95) | 0.092 | ||||

| Low # high | 1.24 (0.77 to 1.98) | 0.011 | ||||

| Low # middle | 1.77* (1.28 to 2.45) | 0.125 | ||||

| Low # low | 2.45* (1.77 to 3.39) | 0.160 | ||||

| Ladder SES # education | ||||||

| High # higher | Reference | |||||

| High # secondary | 2.12 (0.22 to 20.49) | 0.021 | ||||

| High # primary | 8.91* (1.1 to 72.16) | 0.037 | ||||

| High # not educated/primary not completed | 24.14* (3.34 to 174.63) | 0.168 | ||||

| Middle # higher | 1.57 (0.18 to 13.48) | 0.032 | ||||

| Middle # secondary | 3.06 (0.41 to 22.74) | 0.116 | ||||

| Middle # primary | 5.82 (0.8 to 42.55) | 0.167 | ||||

| Middle # not educated/primary not completed | 37.07* (5.19 to 264.9) | 0.568 | ||||

| Low # higher | 2.11 (0.13 to 34.01) | 0.020 | ||||

| Low # secondary | 4.68 (0.6 to 36.81) | 0.079 | ||||

| Low # primary | 8.65* (1.17 to 64.2) | 0.129 | ||||

| Low # not educated/primary not completed | 54.41* (7.61 to 388.93) | 0.602 | ||||

| Ladder SES # caste | ||||||

| High # Others | Reference | |||||

| High # Other Backward Classes | 1.39 (0.83 to 2.32) | 0.003 | ||||

| High # Scheduled Caste | 1.69 (0.82 to 3.48) | 0.016 | ||||

| High # Scheduled Tribe | 1.04 (0.52 to 2.07) | −0.005 | ||||

| Middle # Others | 1.53* (1.01 to 2.32) | 0.081 | ||||

| Middle # Other Backward Classes | 1.60* (1.06 to 2.41) | 0.081 | ||||

| Middle # Scheduled Caste | 1.89* (1.23 to 2.89) | 0.078 | ||||

| Middle # Scheduled Tribe | 2.72* (1.77 to 4.2) | 0.105 | ||||

| Low # Others | 2.27* (1.49 to 3.46) | 0.083 | ||||

| Low # Other Backward Classes | 2.15* (1.42 to 3.26) | 0.111 | ||||

| Low # Scheduled Caste | 2.88* (1.89 to 4.39) | 0.108 | ||||

| Low # Scheduled Tribe | 4.56* (2.97 to 6.98) | 0.132 | ||||

Models 3, 4 and 5 were adjusted for individual, health and household factors.

#=interaction.

* if p<0.05

aOR, adjusted OR; MPCE, monthly per-capita consumption expenditure; SES, socioeconomic status.

Discussion

This study, using a large representative data on older population in India, was in parallel to multiple earlier studies in India and other developing countries which found that older individuals with lower SES experience cognitive impairment compared with people with higher SES.1 25 59 60 This association has been identified in case of both objective and subjective measures of SES. Studies have illustrated empirical evidence on the positive relationship between SES as measured by objective indices of material resources and subjective measures, and psychological well-being.61 62 Similarly, the interactive effect in our study found that older adults with lower levels of subjective and objective SES were at a greater risk of having cognitive impairment.

However, subjective SES was identified to have a much stronger association with cognitive impairment in the unadjusted and adjusted regression estimates in comparison with objective SES measured by household MPCE quintile. With respect to this strong association, there can be some possible explanations. At first, obviously, subjective SES was more meaningful than household wealth index. Higher economic status does not necessarily mean more resources at disposal, if compared with higher individual circumstances, but positive social comparison does. In addition, people with greater household economic status may endure more pressures and mental stress, which in turn may affect their mental health status and cognitive ability.63 This could be mainly due to the subjectivity character of subjective SES. This potential explanation can also be attributed to different perceptions towards wealth and social status among older population in India.

Furthermore, considering the education–cognitive function association, the current findings suggest that higher education is a protective factor against cognitive impairment in older individuals. A hypothesised mechanism is that education is transformed to personal experience and self-perceptions about own social standing, which in turn translate into health and disease. Similarly, the current findings suggest that older adults with no education and low levels of subjective SES had much greater odds of cognitive impairment compared with those with higher education and higher subjective SES. This finding agrees with the previous evidence on the moderating role of education in the relationship between subjective SES and cognitive function. Also, as documented in earlier research,22 subjective SES is a means through which education may influence health outcomes among older people. Nevertheless, proper path analysis using longitudinal data and conducting moderation as well as mediation analyses is needed to test these claims.

Finally, older adults belonging to the lower caste groups (with low social status) were found to be more likely to be cognitively impaired in the study in comparison with those who belong to higher castes. Importantly, in a previous study, it was observed that indicators of subjective SES differ across sociodemographic groups including race, and interpretations may vary when perceiving themselves on the existing social hierarchy.24 Previous studies in India have demonstrated that the socioeconomic disadvantages such as lower income and lack of education were associated with belonging to lower castes (Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes).18 19 64 65 Further, lower caste status being a factor of less opportunities in economic spectrum also contributes to poorer health, health inequalities and mortality burden in India.17 38 66 It is however demonstrated that since individuals may estimate their SES relative to others in a specific community or social group, the social disadvantage may not necessarily negatively influence their mental well-being.61 This suggests that the SES could be better captured by assessing the interactions between subjective and objective measures of SES.

The current study provides crucial clues about what measure of SES highly reflects on cognitive health in old age by underlining the importance of the cumulative dimension of subjective SES and different traditional measures including wealth status, education and caste. Similarly, although no statistical test was performed which assesses whether the difference in magnitude of the association detected by separate models is non-zero and statistically significant, the current findings revealed a greater strength of correlation between subjective SES and cognitive impairment, compared with objective SES measure. The findings also showed the underperformance of traditional measure of wealth status compared with subjective SES. Considering the current findings and the existing evidence,61 separate SES-related ladders that evaluate subjective perceptions of individuals’ economic status (MPCE), education and social status (caste hierarchy in Indian context) may be suggested in well-being research. This is because subjective SES may reflect individuals’ present social circumstances and an assessment of their past experiences and future prospects. As suggested in previous studies, subjective perception of one’s SES might also encompass his/her household resources, life chances and opportunities, and thus captures a broader range of aspects of social stratification than traditional measures of SES do.23 31 67 The finding further underscores the need for future longitudinal investigation of subjective SES-related measurement strategies to obtain a better understanding of the SES–cognitive functioning link especially in poor-resource settings. The effects of country affluence on population health have been demonstrated. Several cross-country comparisons have documented considerable variations in the strength of subjective SES–health relationship between affluent and low-income countries with a stronger association in the latter ones.68 69

There are several limitations of the present study to be considered. The major limitation is the cross-sectional design of the study eliminating the opportunity for drawing of causal inferences among variables. Indeed, it is important to consider that the cognitive measure used in this study included elements that are acquired through years of education and several elements are compounded by literacy levels. Hence, a large number of individuals who are illiterate may be miscategorised as cognitively impaired because they cannot respond with accuracy to several measures, and therefore, reliable cognitive assessment tools should be developed and validated among poorly educated older people in an Indian context. In this regard, much greater odds of cognitive impairment among illiterate population with large CI, even after controlling for several covariates in the main and sensitivity analyses, with separate models for each aspect of SES, may also be a result of a very different sample of older adults with higher education (7%) from those without education (68%). Importantly, due to lack of evidence of algorithm for combing various cognitive tests in the Indian context, we weight all tests equally and use an additive measure for overall cognitive functioning in the current study. Some of the tests may be far better than others in screening for or assessing the degree of cognitive dysfunction or dementia, and thus, the current approach may be misleading and should be addressed in future studies.

In addition, there is a possibility of some of the covariates included in the current analysis potentially being on the pathway between the key explanatory variables and outcome variable. For example, the objective SES, measured by caste, which is generally determined at birth, could influence individuals’ life course in multiple ways, such as their participation in physical or social activities. This may eventually result in collider stratification that leads to biased estimates in the multivariable models in the current study. Finally, there may also be floor or ceiling effects for SES because we have only three categories for both SES measures of ladder and MPCE quintiles.

Notwithstanding these limitations, there were several advantages in this study. At first, this may be the first study to identify the association between both objective and subjective SES indicators and cognitive impairment based on a comprehensive measure with a score of 0–43 among the older Indian population. The large sample of the present study that is free from selection bias includes all SES groups of Indian population that credits to the representativeness and generalisability of the findings. In addition to including multiple SES groups, this study also includes participants living both in rural and urban areas which enhance the generalisability of the results. Further, the findings of the present study provide empirical support to the body of literature that highlights the vulnerability of older adults who have low subjective and objective SES to the worse cognitive health outcomes. Finally, future research may focus on longitudinal associations of various socioeconomic markers with mental health outcomes among middle-aged and older adults in India.

Conclusion

Subjective measures of SES were linked to cognitive outcomes, potentially even more strongly than were the objective measures of SES. Thus, considering the relative ease of obtaining such measures, subjective SES measures are a promising target for future study on socioeconomic indicators of cognitive impairment. The current findings also highlight the importance of subjective SES measure and its interaction with objective (traditional) measures of SES including wealth, education and caste status in assessing the mental health outcomes in developing countries. The findings also suggest that more attention should be placed on subjective SES indicators when investigating socioeconomic influences on cognitive functioning among older adults in India.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, for providing the LASI survey data for undertaking this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: TM and TVS conceived and designed the research paper. SS and TM analysed the data. TVS contributed to agents/materials/analysis tools. TM and SS wrote the manuscript. TM, SS and TVS refined the manuscript. TM acts as guarantor responsible for the overall content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The study uses a secondary data which are available on reasonable request through https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/lasi-wave-i.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

Ethics approval

The necessary guidelines and ethics for undertaking the LASI survey were approved by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). The agencies that conducted the field survey for the data collection had collected prior informed consent (signed and oral) for both the interviews and biomarker tests from the eligible respondents in accordance with the Human Subjects Protection. All methods in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations by the ICMR. There was no number/ID of the approval(s) mentioned in the LASI report (https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/sites/default/files/LASI_India_Report_2020_compressed.pdf).

References

- 1.Wu F, Guo Y, Zheng Y, et al. Social-economic status and cognitive performance among Chinese aged 50 years and older. PLoS One 2016;11:1–9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0166986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s Disease International . World Alzheimer report 2019. attitudes to dementia 2019.

- 3.Burgard SA, Brand JE, House JS. Perceived job insecurity and worker health in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:1–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mutha PK, Robert L, Sainburg KYH. Associations of employment frustration with self-rated physical and mental health among Asian American immigrants in the US labor force. Bone 2008;23:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas C, Benzeval M, Stansfeld SA. Employment transitions and mental health: an analysis from the British household panel survey. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:243–9. 10.1136/jech.2004.019778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y, Back JH, Kim J, et al. Multiple socioeconomic risks and cognitive impairment in older adults. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2010;29:523–9. 10.1159/000315507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, Gu D, Hayward MD. Early life influences on cognitive impairment among oldest old Chinese. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2008;63:25–33. 10.1093/geronb/63.1.s25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horvat P, Richards M, Malyutina S, et al. Life course socioeconomic position and mid-late life cognitive function in eastern Europe. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2014;69:470–81. 10.1093/geronb/gbu014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyu J, Burr JA. Socioeconomic status across the life course and cognitive function among older adults: an examination of the latency, pathways, and accumulation hypotheses. J Aging Health 2016;28:40–67. 10.1177/0898264315585504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cagney KA, Lauderdale DS. Education, wealth, and cognitive function in later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002;57:163–72. 10.1093/geronb/57.2.p163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang ZX, Plassman BL, Xu Q, et al. Lifespan influences on mid- to late-life cognitive function in a Chinese birth cohort. Neurology 2009;73:186–94. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ae7c90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galiani S, Gertler PJ, Bando R. Non-contributory pensions for the poor, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salinas-Rodríguez A, Torres-Pereda MDP, Manrique-Espinoza B, et al. Impact of the non-contributory social pension program 70 y más on older adults' mental well-being. PLoS One 2014;9:e113085. 10.1371/journal.pone.0113085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeki Al Hazzouri A, Haan MN, Kalbfleisch JD, et al. Life-course socioeconomic position and incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment without dementia in older Mexican Americans: results from the Sacramento area Latino study on aging. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:1148–58. 10.1093/aje/kwq483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang M, Gale SD, Erickson LD, et al. Cognitive function in older adults according to current socioeconomic status. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 2015;22:534–43. 10.1080/13825585.2014.997663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manly JJ, Touradji P, Tang M-X, et al. Literacy and memory decline among ethnically diverse elders. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2003;25:680–90. 10.1076/jcen.25.5.680.14579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Po JYT, Subramanian SV. Mortality burden and socioeconomic status in India. PLoS One 2011;6:e16844. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corsi DJ, Subramanian SV. Socioeconomic gradients and distribution of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity in India. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e190411. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subramanian SV, Nandy S, Irving M, et al. Role of socioeconomic markers and state prohibition policy in predicting alcohol consumption among men and women in India: a multilevel statistical analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83:829–36. doi:/S0042-96862005001100012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shavers VL. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J Natl Med Assoc 2007;99:1013–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen E, Martin AD, Matthews KA. Socioeconomic status and health: do gradients differ within childhood and adolescence? Soc Sci Med 2006;62:2161–70. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demakakos P, Nazroo J, Breeze E, et al. Socioeconomic status and health: the role of subjective social status. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:330–40. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh-Manoux A, Marmot MG, Adler NE. Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosom Med 2005;67:855–61. 10.1097/01.psy.0000188434.52941.a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaked D, Williams M, Evans MK, et al. Indicators of subjective social status: differential associations across race and sex. SSM Popul Health 2016;2:700–7. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang L, Martikainen P, Silventoinen K, et al. Association of socioeconomic status and cognitive functioning change among elderly Chinese people. Age Ageing 2016;45:673–9. 10.1093/ageing/afw107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Huang Y, Cheng HG. Lower intake of vegetables and legumes associated with cognitive decline among illiterate elderly Chinese: a 3-year cohort study. J Nutr Health Aging 2012;16:549–52. 10.1007/s12603-012-0023-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki Y, Shobugawa Y, Nozaki I, et al. Association between depressive symptoms and objective/subjective socioeconomic status among older adults of two regions in Myanmar. PLoS One 2021;16:e0245489. 10.1371/journal.pone.0245489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nobles J, Weintraub MR, Adler NE. Subjective socioeconomic status and health: relationships reconsidered. Soc Sci Med 2013;82:58–66. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), NPHCE, MoHFW . Longitudinal ageing study in India (LASI) wave 1. Mumbai, India 2020.

- 30.Bloom DE, Sekher TV, Lee J. Longitudinal aging study in India (LASI): new data resources for addressing aging in India. Nat Aging 2021;1:1070–2. 10.1038/s43587-021-00155-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, et al. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychol 2000;19:586. 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hooker ED, Campos B, Hoffman L, et al. Is receiving social support costly for those higher in subjective socioeconomic status? Int J Behav Med 2020;27:325–36. 10.1007/s12529-019-09836-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suchday S, Chhabra R, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. Subjective and objective measures of socioeconomic status: predictors of cardiovascular risk in college students in Mumbai, India. Ethn Dis 2008;18:S2–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen B, Covinsky KE, Stijacic Cenzer I, et al. Subjective social status and functional decline in older adults. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:693–9. 10.1007/s11606-011-1963-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahinkorah BO. Individual and contextual factors associated with mistimed and unwanted pregnancies among adolescent girls and young women in selected high fertility countries in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel mixed effects analysis. PLoS One 2020;15:e0241050. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petersson KM, Reis A, Ingvar M. Cognitive processing in literate and illiterate subjects: a review of some recent behavioral and functional neuroimaging data. Scand J Psychol 2001;42:251–67. 10.1111/1467-9450.00235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chitnis S. Definition of the terms scheduled castes and scheduled tribes: a crisis of ambivalence. The politics of backwardness: reservation policy in India New Delhi: centre for policy research;104. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zacharias A, Vakulabharanam V. Caste stratification and wealth inequality in India. World Dev 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muhammad T, Srivastava S, Sekher TV. Assessing socioeconomic inequalities in cognitive impairment among older adults: a study based on a cross-sectional survey in India. BMC Geriatr 2022;22:389. 10.1186/s12877-022-03076-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murman DL. The impact of age on cognition. Semin Hear 2015;36:111–21. 10.1055/s-0035-1555115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lei X, Hu Y, McArdle JJ, et al. Gender differences in cognition among older adults in China. J Hum Resour 2012;47:951–71. 10.3368/jhr.47.4.951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muhammad T, Meher T. Association of late-life depression with cognitive impairment: evidence from a cross-sectional study among older adults in India. BMC Geriatr 2021;21:1–13. 10.1186/s12877-021-02314-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srivastava S, Muhammad T. Violence and associated health outcomes among older adults in India: a gendered perspective. SSM Popul Health 2020;12:100702. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar M, Srivastava S, Muhammad T. Relationship between physical activity and cognitive functioning among older Indian adults. Sci Rep 2022;12:1–13. 10.1038/s41598-022-06725-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kato K, Zweig R, Schechter CB, et al. Personality, self-rated health, and cognition in centenarians: do personality and self-rated health relate to cognitive function in advanced age?. Aging 2013;5:183–91. 10.18632/aging.100545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burton CL, Strauss E, Bunce D, et al. Functional abilities in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Gerontology 2009;55:570–81. 10.1159/000228918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vassilaki M, Aakre JA, Cha RH, et al. Multimorbidity and risk of mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:1783–90. 10.1111/jgs.13612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muhammad T, Maurya P. Social support moderates the association of functional difficulty with major depression among community-dwelling older adults: evidence from LASI, 2017-18. BMC Psychiatry 2022;22:317. 10.1186/s12888-022-03959-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muhammad T, Hossain B, Das A, et al. Relationship between handgrip strength and self-reported functional difficulties among older Indian adults: the role of self-rated health. Exp Gerontol 2022;165:111833. 10.1016/j.exger.2022.111833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srivastava S, Debnath P, Shri N, et al. The association of widowhood and living alone with depression among older adults in India. Sci Rep 2021;11:1–13. 10.1038/s41598-021-01238-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu H, Ostbye T, Vorderstrasse AA, et al. Place of residence and cognitive function among the adult population in India. Neuroepidemiology 2018;50:119–27. 10.1159/000486596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee J, Smith JP. Regional disparities in adult height, educational attainment and gender difference in Late- life cognition: findings from the longitudinal aging study in India (LASI). J Econ Ageing 2014;4:26–34. 10.1016/j.jeoa.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Osborne J, King JE. Binary logistic regression. In: Best practices in quantitative methods. SAGE Publications, Inc, 2011: 358–84. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aiken LS, West SG, Pitts SC. Multiple linear regression. In: Handbook of psychology, 2003: 481–507. [Google Scholar]

- 55.StataCorp . Stata: release 14. statistical software 2015.

- 56.Lewis-Beck M, Bryman A, Futing Liao T. Variance inflation factors. In: The SAGE encyclopedia of social science research methods, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vogt W. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). In: Dictionary of statistics & methodology, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muhammad T, Govindu M, Srivastava S. Relationship between chewing tobacco, smoking, consuming alcohol and cognitive impairment among older adults in India: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 2021;21:85. 10.1186/s12877-021-02027-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nutakor JA, Dai B, Zhou J, et al. Association between socioeconomic status and cognitive functioning among older adults in Ghana. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021;36:2–31. 10.1002/gps.5475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kumar H, Arokiasamy P, Selvamani Y. Socioeconomic disadvantage, chronic diseases and their association with cognitive functioning of adults in India: a multilevel analysis. J Popul Ageing 2020;13:285–303. 10.1007/s12062-019-09243-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Navarro-Carrillo G, Alonso-Ferres M, Moya M, et al. Socioeconomic status and psychological well-being: revisiting the role of subjective socioeconomic status. Front Psychol 2020;11:1–15. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma X, McGhee SM. A cross-sectional study on socioeconomic status and health-related quality of life among elderly Chinese. BMJ Open 2013;3:17–19. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Callan MJ, Kim H, Matthews WJ. Predicting self-rated mental and physical health: the contributions of subjective socioeconomic status and personal relative deprivation. Front Psychol 2015;6:1–14. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khubchandani J, Soni A, Fahey N, et al. Caste matters: perceived discrimination among women in rural India. Arch Womens Ment Health 2018;21:163–70. 10.1007/s00737-017-0790-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bapuji H, Chrispal S. Understanding economic inequality through the lens of caste. J Bus Ethics 2020;162:533–51. 10.1007/s10551-018-3998-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muhammad T, Maurya P. Gender differences in the association between perceived income sufficiency and self-rated health among older adults: a population-based study in India. J Women Aging 2021:1–14. 10.1080/08952841.2021.2002663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG. Subjective social status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:1321–33. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00131-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Semyonov M, Lewin-Epstein N, Maskileyson D. Where wealth matters more for health: the wealth-health gradient in 16 countries. Soc Sci Med 2013;81:10–17. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Präg P, Mills MC, Wittek R. Subjective socioeconomic status and health in cross-national comparison. Soc Sci Med 2016;149:84–92. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-052501supp001.pdf (45.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The study uses a secondary data which are available on reasonable request through https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/lasi-wave-i.