Abstract

In this paper, we describe two open reading frames coding for a NAD-dependent malic enzyme (mae) and a putative regulatory protein (clyR) found in the upstream region of citCDEFG of Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris 195. The transcriptional analysis of the citrate lyase locus revealed one polycistronic mRNA covering the mae and citCDEF genes. This transcript was detected only on RNA prepared from cells grown in the presence of citrate. Primer extension experiments suggest that clyR and the citrate lyase operon are expressed from a bidirectional A-T-rich promoter region located between mae and clyR.

Leuconostocs are heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria used as a starter in association with lactococci for the manufacture of fermented milks and cheeses. Leuconostocs contribute to cheese flavor and texture due to the production of diacetyl, acetoin, acetate, and carbon dioxide from citrate metabolism. Conversion of citrate into pyruvate by lactic acid bacteria requires three enzymes: a citrate permease (CitP), a citrate lyase (CL) that cleaves intracellular citrate into acetate and oxaloacetate, and an oxaloacetate decarboxylase that catalyzes the oxaloacetate decarboxylation into carbon dioxide and pyruvate. CitP catalyzes an electrogenic exchange of divalent citrate and monovalent organic acid, resulting in the generation of a membrane potential (17, 18). The CL (EC 4.1.3.6) was shown to form a functional complex (Mr, 585,000) of three proteins: a γ subunit (acyl carrier protein [ACP]), a β subunit (citryl-S-ACP lyase; EC 4.1.3.34), and an α subunit (citrate:acetyl-ACP transferase; EC 2.8.3.10) (1, 7). This enzymatic complex is active only if the thioester residue of the prosthetic group linked to the γ subunit is acetylated. This activation is catalyzed by an SH-CL ligase (EC 6.2.1.22) which converts HS-ACP in the presence of ATP and acetate to acetyl-S-ACP (21, 22).

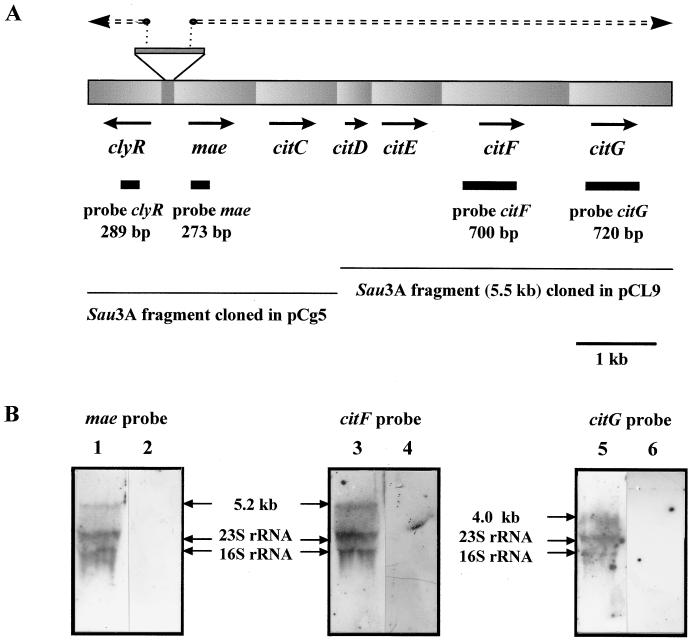

Recently, we used a reverse genetic strategy to clone and characterize five genes of the CL multienzymatic complex from a genomic library of Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris 195 constructed by ligation into pJDC9 (1). Two clones contained in plasmids pCL9 and pCg5 were selected. Plasmid pCL9 was shown to contain an incomplete citC gene coding for CL ligase and the genes citDEFG for ACP, the β and α subunits, and CitG, respectively. The function of the citG product remains unknown. Plasmid pCg5 was shown to contain DNA encoding the N terminus of CL ligase (citC). The citCDEFG genes are clustered on a 5.2-kb DNA fragment (Fig. 1). The absence of intergenic regions between citC, citD, citE, and citF suggested that all of these genes could be expressed in an large polycistronic mRNA.

FIG. 1.

(A) Organization of the CL genes in L. mesenteroides. Every gene is drawn to scale, and orientations of transcription are indicated by arrows. The Sau3A DNA fragments cloned in plasmids pCL9 and pCg5 are shown as thin lines at the bottom. Transcription initiation points are indicated by small open circles, and the transcripts are indicated by a double broken line. Probes used for Northern blotting are shown as solid bars. (B) Northern blot autoradiogram. Total RNAs prepared from L. mesenteroides cells grown in the presence of citrate (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or in its absence (lanes 2, 4, and 6) were analyzed by electrophoresis on agarose-formamide gels, blotted onto a nylon membrane, and hybridized with mae (lane 1 and 2), citF (lane 3 and 4), or citG (lane 5 and 6). Arrows indicate the migration positions of 23S and 16S rRNAs and the 5.2- and 4.0-kb transcripts. Sizes were determined by using an RNA ladder (9.5 to 0.25 kb; Gibco-BRL).

In this paper, we describe two open reading frames (ORFs) coding for an NAD-dependent malic enzyme (mae) and a putative regulatory protein (clyR) found in the upstream region of citCDEFG. One polycistronic mRNA covering the mae and citCDEF genes was detected only in RNA prepared from cells grown in the presence of citrate. The clyR gene and the CL operon are expressed from a bidirectional extraordinary A-T-rich promoter region located between mae and clyR.

CL activity of L. mesenteroides is induced by citrate.

CL activity was determined from cells growing in MRS medium (6) in the absence or presence of citrate or malate. When the optical density at 600 nm of a culture of L. mesenteroides had reached 0.4, citrate (10 g/liter) or malate at (5 g/liter) was added to the growth medium. CL activity was assayed at 25°C in a coupled spectrophotometric assay as described previously (1). Because CL could be inactivated by deacetylation of a prosthetic group linked to its ACP, the enzyme sample was chemically acetylated with 5 mM acetic anhydride for 1 min at 25°C and then used immediately for determination of CL activity. One unit of CL activity is defined as 1 mol of citrate converted to acetate and oxaloacetate per min. Malate enzyme activity was determined as described by Kobayashi et al. (14).

In the absence of citrate, no CL or malic enzyme activity was detected. Addition of citrate to the medium resulted in strong induction of CL activity (2.5 U/mg of protein). When cells were grown in malate medium, the CL activity was not induced. In the presence of citrate or malate, no malic enzyme activity was detected in L. mesenteroides subsp. cremoris (data not shown).

Sequence analysis of the upstream region of the citCDEFG gene cluster.

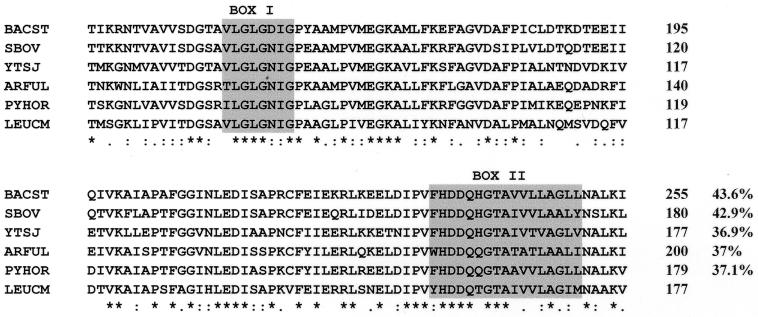

The DNA sequence of the upstream region of citCDEFG was determined on both strands by oligonucleotide primer walking using the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (Thermosequenase kit; Amersham) with pCg5 as a template. A 1,127-bp ORF in the same orientation as citCDEFG was found (Fig. 1). This ORF encoded a 375-amino-acid protein (calculated molecular mass, 39,475 Da) preceded by a putative ribosome binding site (RBS) (5′-AAGGAG-3′) which is complementary to the 3′ end of the L. mesenteroides 16S rRNA sequence (26). The stop codon of this ORF was located 73 nucleotides upstream of the start codon of citC. A comparison of the primary structure of the putative protein with protein sequences in the Swissprot and Pirprot sequence data banks revealed similarities to malic enzymes. Therefore, this gene was designated mae and encodes a putative malate oxidoreductase. Malic enzymes [(s)-malate:NAD+ oxidoreductase (decarboxylating)] which catalyze malate oxidative decarboxylation are classified into three groups (EC 1.1.1.38, EC 1.1.1.39, and EC 1.1.1.40) on the basis of coenzyme specificity and ability to catalyze the decarboxylation of oxaloacetate. The putative mae gene product of L. mesenteroides showed a high level of sequence identity (37 to 44%) to the NAD-dependent malic enzymes (EC 1.1.1.38) of Bacillus subtilis (16), Streptococcus bovis (11), Pyrococcus horikoshii (12), Archaeoglobus fulgidus (13), and Bacillus stearothermophilus (14). Two highly conserved sequences (box I and box II) were found (Fig. 2). Box I corresponds to an NAD-binding domain (24). The amino acid sequence from position 153 to position 169 (box II) is described as the malic enzyme signature in the Prosite database {PS00331; F-x-[DV]-D-x(2)-G-T-[GSA]-x-[LIVMA]-[GAST](2)-[LIVMF](2)}. However, a phenylalanine residue, which is the first amino acid of the consensus pattern, is replaced in our sequence by a tyrosine at position 153. Replacement of the same phenylalanine residue with a tryptophan is also observed in the sequence of the malic enzyme from A. fulgidus (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of part of the deduced amino acid sequence of mae from L. mesenteroides (LEUCM) with parts of the sequences of the malic enzymes from B. stearothermophilus (BACST; protein sequence accession no. P16468), Streptococcus bovis (SBOV; accession no. U35659), B. subtilis (YTSJ; accession no. Z99118), A. fulgidus (ARFUL; accession no. AE000984), and P. horikoshii (PYHOR; accession no. 3257695). Identical amino acids are indicated by asterisks. The conserved region corresponding to an NAD-binding domain and the malic enzyme signature are enclosed in boxes I and II, respectively. The numbers on the right are amino acid positions in the protein sequences. The percentages on the right are the levels of identity between the entire protein sequence deduced from mae and the sequences of the previously described proteins.

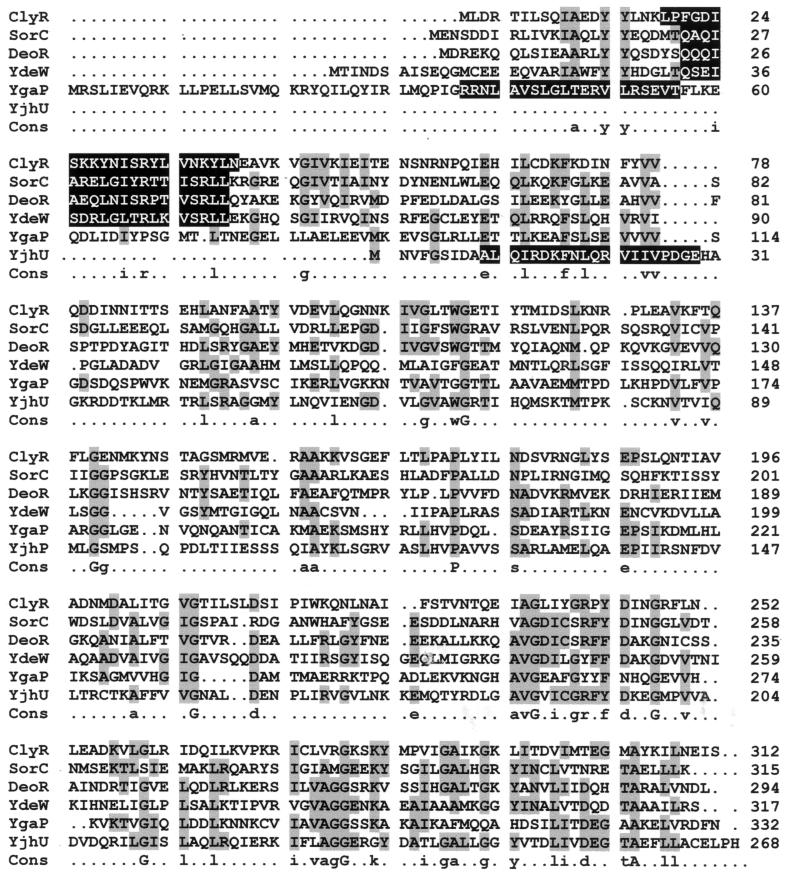

Sequence analysis of the upstream region of mae revealed a 939-bp ORF transcribed divergently from the mae-citCDEFG genes (Fig. 1). This ORF encoded a putative protein of 312 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 35,080 Da. A potential RBS (5′-GGAGG-3′), is localized 8 bp upstream of the translation start site (ATG). A comparison of the primary structure of the putative protein with protein sequences in data banks revealed similarities to regulatory proteins belonging to the SorC family of transcriptional regulators. The highest degree of identity (23.3%) was found with SorC, which positively and negatively regulates, in the presence and absence of l-sorbose, respectively, the transcription of the sorbose operon of Klebsiella pneumoniae (23, 25). Significant identity was also shown with YhjU, a hypothetical transcriptional regulator of Escherichia coli (4), and DeoR, a deoxyribonucleotide regulator of B. subtilis (20). In the N-terminal part of the 312-amino-acid polypeptide gene product, a helix-turn-helix motif was identified (positions 21 to 34) by using the weight matrix of Dodd and Egan (8). This motif probably forms a DNA-binding region, suggesting that this gene product could act as an activator or repressor of transcription. Because of its localization near the citrate lyase operon, we named this gene clyR. Alignment of multiple amino acid sequences performed with the Multalign program (5) showed that identity scores were particularly high in the N-terminal sequence in which the helix-turn-helix was present and in the last 80 amino acids of the C terminus of the SorC family of regulators (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Multiple-sequence alignment of ClyR with proteins belonging to the SorC family of transcriptional regulators: SorC, from K. pneumoniae (protein sequence accession no. P37078); DeoR, a deoxyribonucleoside regulator from B. subtilis (accession no. P39140); YdeW, a hypothetical transcriptional regulator in the HipB-UxaB intergenic region of E. coli (accession no. P76141); YgaP, a hypothetical transcriptional regulator in the gap 5′ region of Bacillus megaterium (accession no. P35168); YjhU, a hypothetical transcriptional regulator in the fecI-fimB intergenic region of E. coli (accession no. P39356). Sequence identities (percentages) between ClyR and the individual proteins are as follows: SorC, 23.3%; YjhU, 26.2% in a 221-amino-acid overlap; DeoR, 22.6%; YdeW, 20.7%; YgaP, 18.7%. The deduced primary sequences were aligned by the multiple-sequence alignment program Multalign (5). Amino acids conserved in at least three of the six sequences shown are shaded. The helix-turn-helix domains are white letters in black boxes. The derived consensus (Cons) sequence corresponding to amino acids conserved in at least four sequences is in the bottom row. All sequences are numbered from Met-1.

Transcriptional analysis of the CL locus.

To determine the transcriptional organization and the nature of CL activity induction, in vivo transcripts of the CL locus were detected by dot blotting and Northern hybridization analysis. RNA was prepared as previously described (15) from Leuconostoc cells grown on MRS medium in the presence or absence of citrate. DNA probes specific for mae (273 bp), citF (700 bp) citG (720 bp), and clyR (289 bp) were generated by PCR amplification using pCL9 and pCg5 as templates (Fig. 1). For Northern blot analysis, 30 μg of RNA was loaded on a denaturing 0.9% (wt/vol) agarose–6.6% (wt/vol) formaldehyde gel and, after electrophoresis, transferred to Nitran membranes (Amersham). DNA radiolabeling, transfer, and hybridization were performed as described previously (1).

Using DNA probes for mae, citC, citF, and citG, the dot blot experiments revealed that transcripts were detected only in mRNA prepared from cells grown in the presence of citrate (data not shown). In the Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1), only one major mRNA transcript was detected by the mae, citF, and citG probes. No mRNA transcript was detected by dot blotting or Northern blotting using the clyR probe. When probes for mae and citF were used, a single large transcript of approximately 5.2 kb was detected. The length of the transcript is consistent with the size expected from the total nucleotide sequence of the mae-citCDEF genes (5 kb). The transcript detected by the citG probe had a size of 4.0 kb. Since this mRNA did not hybridize with the mae and citF probes, it presumably corresponds to an RNA starting downstream of the region corresponding of the citF probe and ending downstream of citG or from processing of a larger transcript including the mae-citCDEF genes. These transcripts were detected only from citrate-induced cells (Fig. 1). Two bands corresponding in size to rRNAs (1,541 and 2,904 bases) were detected in RNA from cells grown in the presence of citrate. As previously reported by others (9, 10), these bands corresponded to citCDEF mRNA fragments that were presumably degraded in the course of RNA purification.

These results establish that the mae-citCDEF genes are cotranscribed from a common citrate-regulated promoter-operator region located upstream of mae. The physical arrangement of these genes suggested that they form an operon.

Determination of the 5′ terminus of the CL operon.

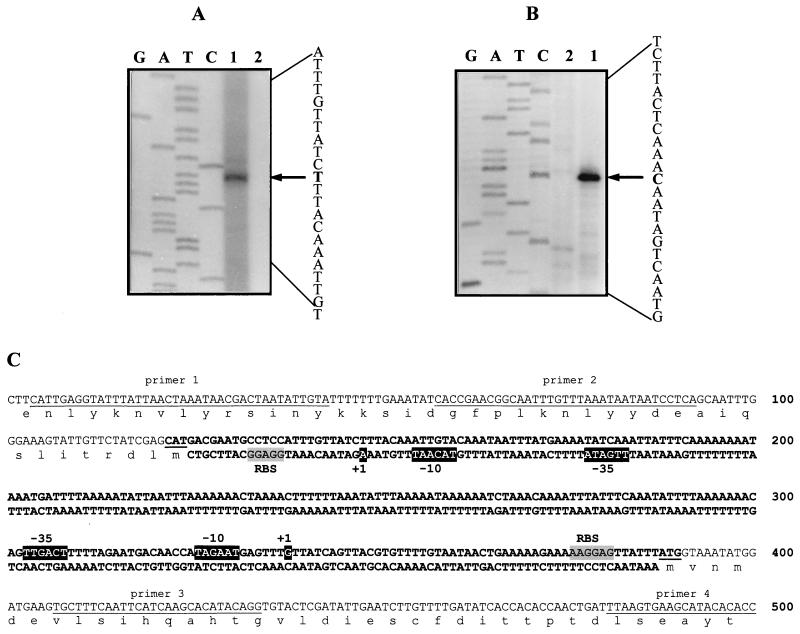

To determine the transcription start site, primer extension experiments were performed. For this, 1 pmol of each primer was annealed with 5 μg of total RNA, followed by synthesis of 32P-labeled cDNA using reverse transcriptase as previously described (15). The radiolabeled products were then separated on a 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel and visualized by autoradiography. The start site was determined with two different primers complementary to the 407-to-441 (primer 3) and 480-to-500 (primer 4) nucleotide sequences (Fig. 4). RNA (30 μg) prepared from cells grown in the presence or absence of citrate was used. Figure 4B shows the result of a primer extension experiment using primer 4. Transcripts from the mae promoter were detected only in citrate-induced cells. No signal was detected in the absence of a primer (data not shown). Primer extension analysis gave unique signals for the two primers used. A comparison of the extension product with the DNA sequencing ladder as a standard showed that the 5′ end of the mRNA corresponded to a G nucleotide positioned at nucleotide 338, 50 bp upstream of the putative translational initiation codon of the mae reading frame (Fig. 4). This finding suggests that the polycistronic mRNA starts at this site. The sequence TTGACT-17 bp-TAGAAT located a short distance upstream is a likely candidate for the operon promoter.

FIG. 4.

Determination of the transcription start site of mae and clyR. (A) Primer extension performed with clyR primer 1. (B) Primer extension performed with mae primer 4. Primer extension reactions were performed as described in the text. Primer extension products were obtained by using RNA isolated from L. mesenteroides cells grown in the presence of citrate (lane 1) or in its absence (lane 2). The same oligonucleotide primer used for the primer extension analysis was used for sequencing by the dideoxy-chain termination method. G, guanine; A, adenosine; T, thymine; C, cytosine. A sequence complementary to that read from the ladder is shown, and the start site of the transcript is indicated by an arrow. (C) Nucleotide sequence of the mae-clyR intergenic region containing the bidirectional promoter region of the mae-citCDEF and clyR genes. The 239-bp intergenic region between translation codons of the mae and clyR genes is in boldface. The −10 and −35 regions and the transcription initiation sites (+1) are white letters in black boxes. The putative RBSs are shaded. The ATGs of the mae and clyR genes are underlined.

Primer extension analysis of the transcriptional start point of clyR.

Regulatory proteins are weakly synthesized in cells. If the clyR gene product is a regulatory protein, the difficulty in detecting mRNA from it was not surprising. However, the transcriptional start site of clyR was successfully determined by primer extension experiments using two different oligonucleotides extending from nucleotide 4 to nucleotide 44 (primer 1) and from nucleotide 59 to nucleotide 93 (primer 2) (Fig. 4). RNA (30 μg) from cells grown in the presence or absence of citrate was used. An extension product was detected only when RNA prepared from citrate-induced cells was used. Primer extension analysis gave unique signals for the two primers used. No signal was detected in the absence of a primer. Figure 4A show the result of a primer extension experiment using primer 1. The extension product indicated that the 5′ end of the mRNA corresponded to nucleotide A located 24 bp upstream of the start codon of the clyR gene. This transcription start point allowed localization of the putative promoter to the sequence TTGATA-17 bp-TACAAT (Fig. 4).

Conclusion.

In this paper, we describe two ORFs potentially coding for an NAD-dependent malic enzyme (mae) and a putative regulatory protein (clyR) found in the upstream region of citCDEFG of L. mesenteroides. This is the first report of genes coding for a putative malic enzyme and a regulator protein belonging to the SorC family in a lactic acid bacterium. The mae product showed a high level of sequence similarity to malic enzymes of B. stearothermophilus that, in addition to the NAD-dependent oxidative decarboxylation of l-malate, catalyzes the decarboxylation of oxaloacetate. The CL activity of L. mesenteroides was induced by citrate, and a transcript from mae-citCDEFG was detected only in RNA prepared from cells grown in the presence of citrate. However, no significant malic enzyme activity could be detected in cells grown in the presence of citrate, showing that the malic enzyme is not induced by citrate while transcription of mae is citrate dependent. The role of the mae gene product in citrate metabolism remains to be determined. This gene could code for an inactive malic enzyme or does not encode a malic enzyme. The mae gene in the CL operon is not present in the other CL operon previously described in K. pneumoniae (2). The transcription of the citS-oadGAB and citC operons encoding citrate carrier, oxaloacetate decarboxylase, and CL, respectively, is citrate dependent in K. pneumoniae cells grown anaerobically. In this organism, expression of the citrate fermentation genes was shown to be positively controlled by a two-component signal transduction system encoded by the promoter-distal gene of the citS operon, citA (sensor kinase) and citB (response regulator) (3, 19).

In L. mesenteroides, the DNA region (189 nucleotides) between the transcription starts of clyR and mae containing the two identified putative promoters showed an extraordinarily high A+T content (82.1%) (Fig. 4). These promoters showed close similarity to the consensus found in promoters from gram-positive bacteria and E. coli. Divergent promoter regions in bacteria are frequently targets for the control of gene expression at the transcriptional level. The divergent promoter region between the clyR and mae genes is likely to be a putative target for recognition by a regulatory protein involved in the control of the CL activity of L. mesenteroides. The fact that the extension product obtained with the clyR primers was only obtained with RNA from citrate-grown cells provides the only experimental evidence that ClyR could regulate the mae-citCEDF genes. The disruption of clyR certainly will allow us to elucidate its function in the expression of the CL operon. Unfortunately, no useful techniques are available at this time for this type of genetic approach to L. mesenteroides.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported herein has been combined with sequences from previous GenBank submissions (accession no. Y10621).

Acknowledgments

S.B. was the recipient of a fellowship from the Programme Intergouvernemental Franco-Algérien. This work was supported by a grant from the Conseil Régional de Bourgogne.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bekal S, Van Beuumen J, Samyn B, Garmyn D, Henini S, Diviès C, Prévost H. Purification of Leuconostoc mesenteroides citrate lyase and cloning and characterization of the citCDEFG gene cluster. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:647–654. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.647-654.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bott M, Dimroth P. Klebsiella pneumoniae genes for citrate lyase and citrate lyase ligase: localization, sequencing and expression. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:347–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bott M, Meyer M, Dimroth P. Regulation of anaerobic citrate metabolism in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:533–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burland V, Plunkett III G, Sofia H, Daniels D, Blattner F. Analysis of the Escherichia coli genome. VI. DNA sequence of the region from 92.8 through 100 minutes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2105–2119. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.12.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Man J C, Rogosa M, Sharpe M E. A medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. J Appl Bacteriol. 1960;23:130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimroth P, Eggerer H. Isolation of subunits of citrate lyase and characterization of their function in the enzyme complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3458–3462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodd I B, Egan J B. Systematic method for the detection of potential lambda Cro-like DNA-binding regions in proteins. J Mol Biol. 1987;194:557–564. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90681-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henningan A N, Reeve J N. mRNAs in methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus vannielii: numbers, half-lives and processing. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:655–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang F, Coppola G, Calhoun H. Multiple transcripts encoded by the ilvGMEDA gene cluster of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4871–4877. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.4871-4877.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawai S, Suzuki H, Yamamoto K, Inui M, Yakawa H, Kumagai H. Purification and characterization of a malic enzyme from the ruminal bacterium Streptococcus bovis ATCC 15352 and cloning and sequencing of its gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2692–2700. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.2692-2700.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawarabayasi Y, Sawada M, Horikawa H, Haikawa Y, Hino Y, Yamamoto S, Sekine M, Baba S, Kosugi H, Hosoyama A, Nagai Y, Sakai M, Ogura K, Otsuka R, Nakazawa H, Takamiya M, Ohfuku Y, Funahashi T, Tanaka T, Kudoh Y, Yamazaki J, Kushida N, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Yoshizawa T, Nakamura Y, Robb F T, Horikoshi K, Masuchi Y, Shizuya H, Kikuchi H. Complete sequence and gene organization of the genome of a hyper-thermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. DNA Res. 1998;5:147–155. doi: 10.1093/dnares/5.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klenk H P, Clayton R A, Tomb J, White O, Nelson K E, Ketchum K A, Dodson R J, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Richardson D L, Kerlavage A R, Graham D E, Kyrpides N C, Fleischmann R D, Quackenbush J, Lee N H, Sutton G G, Gill S, Kirkness E F, Dougherty B A, McKenney K, Adams M D, Loftus B, Peterson S, Reich C I, McNeil L K, Badger J H, Glodek A, Zhou L, Overbeek R, Gocayne J D, Weidman J F, McDonald L, Utterback T, Cotton M D, Spriggs T, Artiach P, Kaine B P, Sykes S M, Sadow P W, D’Andrea K P, Bowman C, Fujii C, Garland S A, Mason T M, Olsen G J, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature. 1997;390:364–370. doi: 10.1038/37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi K, Doi S, Negro S, Urabe I, Okada H. Structure and properties of malic enzyme from Bacillus stearothermophilus. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3200–3205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labarre C, Diviès C, Guzzo J. Genetic organization of the mle locus and identification of a mleR-like gene from Leuconostoc oenos. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4493–4498. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4493-4498.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lapidus A, Galleron N, Sorokin A, Ehrlich S D. Sequencing and functional annotation of the Bacillus subtilis genes in the 200 kb rrnB-dnaB region. Microbiology. 1997;143:3431–3441. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-11-3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marty-Teysset C, Lolkema J S, Schmitt P, Diviès C, Konings W N. Membrane potential-generating transport of citrate and malate catalyzed by CitP of Leuconostoc mesenteroides. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25370–25376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marty-Teysset C, Posthuma C, Lolkema J S, Schmitt P, Diviès C, Konings W N. Proton motive force generation by citrolactic fermentation in Leuconostoc mesenteroides. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2178–2185. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2178-2185.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer M, Dimroth P, Bott M. In vitro binding of the response regulator CitB and its carboxy-terminal domain to A+T rich DNA target sequences in the control region of the divergent citC and citS operons of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:719–731. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxild H H, Anderson L N, Hammer K. dra-nupC-pdp operon of Bacillus subtilis: nucleotide sequence, induction by deoxyribonucleosides, and transcriptional regulation by the deoR-encoded DeoR repressor protein. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:424–434. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.424-434.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmellenkamp B, Eggerer H. Mechanism of enzymic acetylation of desacetyl citrate lyase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1987–1991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.5.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh M, Srere P A, Klapper D G, Capra J D. Subunit and chemical composition of citrate lyase from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Eur J Biochem. 1976;251:2911–2915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wehmeier U F, Lengeler J W. Sequence of the sor-operon for l-sorbose utilization from Klebsiella pneumoniae KAY2026. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;19:348–351. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wierenga R K, Terptra P, Hol W G F. Prediction of the occurrence of the ADP-binding βαβ fold in protein, using an amino-acid sequence fingerprint. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:101–107. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wohrl B M, Wehmeier U F, Lengeler J W. Positive and negative regulation of expression of the l-sorbose (sor) operon by SorC in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;224:193–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00271552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang D, Woese C R. Phylogenetic structure of the Leuconostoc: an interesting case of a rapidly evolving organism. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1989;12:145–149. [Google Scholar]