Abstract

Enterococci have been recognized as major pathogens causing nosocomial and community-acquired infections. The emergence of antimicrobial-resistant enterococci is one of the major public health challenges worldwide. While many enterococcal species have been identified, Enterococcus avium is rarely detected in humans. Here we present an interesting case of urinary tract infection and haematuria involving E. avium in a 72-year-old patient. The patient underwent antibiotic therapy and surgical procedures with excellent improvement. This case report highlights the important role of E. avium in clinical settings.

Keywords: haematuria, urinary tract infection, Enterococcus avium, VITEK 2

Introduction

Enterococci are Gram-positive, catalase-negative and non-spore-forming bacteria that usually inhabit the alimentary tract of humans and animals [1, 2]. Enterococci are known to be important pathogens in humans, and their ability to inherit or acquire antibiotic resistance determinants is a global public health issue, causing significant morbidity and mortality [3]. Vancomycin resistance in enterococci was first reported in the UK in 1986, and the rapid increase of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) raised alarms in many countries [4, 5]. VRE infections are associated with increased mortality, longer length of stay, increased risk of discharge to a long-term care facility or readmission and higher costs [6]. Severe enterococcal infection-associated morbidity and mortality remain as high as 20–40 %, despite advances in antimicrobial therapy over the past few decades [7]. Enterococci are also common nosocomial pathogens, being responsible for approximately 14 % of hospital-acquired infections in the USA [8]. To date, approximately 58 different enterococcal species have been identified. Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium are the most common, and they cause a variety of infections in humans, including bacteraemia, endocarditis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), prostatitis, intra-abdominal infection, cellulitis and wound infection [9, 10]. E. avium is also a member of the genus Enterococcus , and this species is mostly found in birds. E. avium is rarely a cause of infection in humans. In this study, we present an interesting case in which E. avium was isolated from urine collected from a patient showing UTI symptoms and haematuria.

Case presentation

A 72-year-old patient with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, endometrial cancer and atrial fibrillation initially had symptoms of urinary frequency and urgency, as well as dysuria and haematuria.

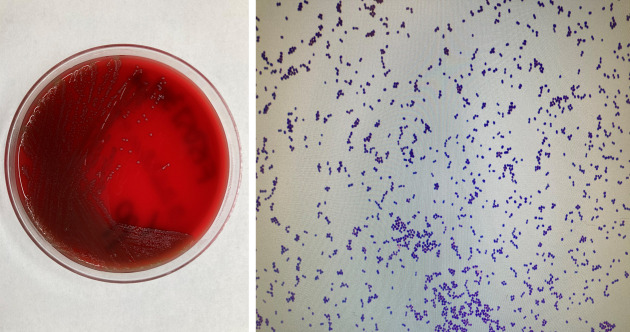

The patient went to a primary care physician and was treated with a 1 week course of cefuroxime for uncomplicated cystitis. A urine specimen was collected and submitted to our clinical microbiology laboratory for bacterial culture. After 24 h of incubation at 35 °C in 5 % CO2, growth was observed on nonselective blood and chocolate agar plates. Small, grey, non-haemolytic colonies grew on the selective Columbia CNA agar plate. Gram-positive cocci were seen on the microscopic examination of a Gram-stained smear, as shown in Fig. 1. The isolate was identified as E. avium by the VITEK 2 system with an excellent confidence score of 99 %. Other bright reddish-pink colonies were also seen to grow on the selective MacConkey agar plate. These colonies were Gram-negative bacilli, and were identified as Escherichia coli .

Fig. 1.

Small, grey, non-haemolytic colonies of Enterococcus avium were observed on sheep blood agar, and microscopic examination of a Gram-stained smear revealed small Gram-positive cocci at 1000× magnification.

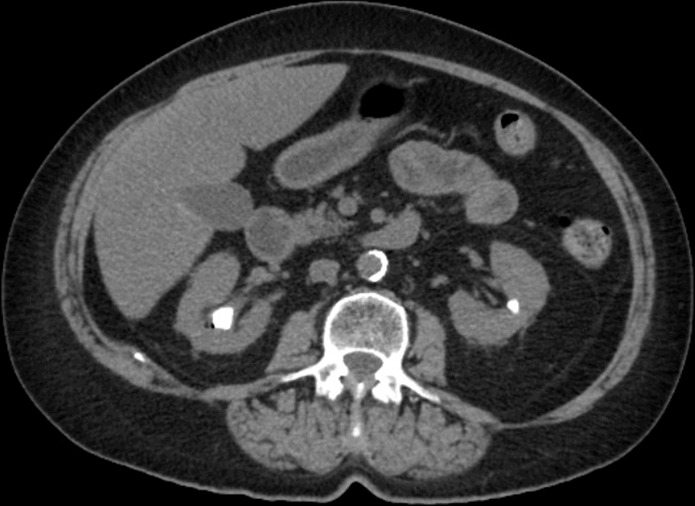

After completing the full course of antibiotics as prescribed, the UTI symptoms improved significantly; however, the painless haematuria persisted. The patient reported that the bloody urine was visible in the toilet bowl, and there was also a small amount on the toilet paper as the patient wiped. The patient denied any significant bleeding into the undergarments between voids. A newly collected urine specimen was submitted for bacterial culture. There was no growth on the agar after 48 h of incubation, and the urine culture was considered negative. Urinary cytology was negative for high-grade urothelial carcinoma. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed a 2.8 cm staghorn stone in the upper pole of the right kidney and a 8 mm nonobstructing stone in the interpolar region of the left kidney (Fig. 2). No focal renal lesions were identified. Ureteral stones or hydronephrosis were not noted. However, there was diffuse wall thickening and oedema of the bladder. Cystoscopy revealed a bleeding lesion just to the right of the bladder neck that was mildly ulcerated. The lesion (approximately 0.5 cm) was resected, and the entire base of the resection site was cauterized. The patient also underwent the percutaneous nephrolithotomy to remove the staghorn stone in the right kidney. The patient was eventually discharged and did well on the follow-up visit.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal and pelvic CT. The cut showed a 2.8 cm staghorn stone in the upper pole of the right kidney and a 8 mm non-obstructing stone in the interpolar region of the left kidney.

Discussion

E. avium , formerly ‘group Q streptococcus’, has rarely been known as a pathogen in humans. During the 12 years from 1997 to 2009, there were 53 patients with E. avium bacteraemia at a tertiary-care hospital in the Republic of Korea, and the mortality rate was 11.3 % [11]. Mohanty and co-authors found the first case of brain abscess due to E. avium in a 19-year-old man with chronic otitis media since childhood [12]. This bacterium has been isolated in abscess aspirates from different organs, such as the spleen and pancreas [13, 14]. Only a few other clinical diseases caused by E. avium have been reported, including endocarditis, osteomyelitis, peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis and cholecystitis [15–18]. However, UTI and haematuria associated with E. avium are very rare. Here we present an interesting case of UTI and haematuria involving E. avium in an adult patient. Since E. avium is very commonly found in birds, one of the risk factors for E. avium infection is contact with birds. There is no evidence that the E. avium infection in this patient was acquired through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. Therefore, the source of infection could not be identified. The clinical significance of E. avium is questionable in causing UTI and haematuria in this clinical case, since E. coli was also isolated in the same urine specimen. E. coli has been documented to be the most prevalent agent of uncomplicated and complicated UTIs. It is important to point out that E. avium grew a high number of 50 000 colony-forming units (c.f.u.) ml−1 in the urine specimen, suggesting its causative role in this clinical case. Our keyword search ( E. avium and UTI or haematuria or cystitis) in PubMed identified only two previously published studies [19, 20]. Ishihara et al. reported 24 E. avium strains isolated from Japanese patients with complicated UTIs between 1988 and 2000 [19]. In northern India, E. avium was isolated in two urine specimens collected from patients diagnosed with community-acquired UTIs [20]. In addition, E. avium was reported in blood and the E. avium bacteraemia-related mortality rate was 11.3 % [21]. This rare micro-organism was also found in cerebrospinal fluid and caused meningoencephalitis [22]. Taken together, we should consider E. avium to be a clinical pathogen associated with UTI and haematuria in this case. The association of E. avium with UTI and haematuria further extends the clinical spectrum of this rare pathogen.

Conclusion

E. avium has emerged as a pathogen causing a variety of human infections. The detection of E. avium in urine collected from this case and in sterile sites such as blood or cerebrospinal fluid from the previous reports highlights the important role in the pathogenicity of E. avium in humans. To the best of our knowledge, our case study is the first report showing the possible association of E. avium and haematuria. Although E. avium is thought to have low virulence, a high mortality rate in patients with bacteraemia, especially in those with severe underlying conditions, has been reported. Therefore, accurate diagnosis and early treatment are essential to achieve a successful outcome.

Funding information

The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the clinical microbiology laboratory at UPMC for help with initial isolation and characterization of the isolate.

Author contributions

T.P., S.H. and A.A.: designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

Approval from the ethical committee was not required due to the nature of this case report. Abiding by the Declaration of Helsinki, patient anonymity was guaranteed.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; UTI, urinary tract infection; VRE, vancomycin -resistant enterococci.

References

- 1.Hammerum AM. Enterococci of animal origin and their significance for public health. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:619–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krawczyk B, Wityk P, Gałęcka M, Michalik M. The many faces of Enterococcus spp.-commensal, probiotic and opportunistic pathogen. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1900. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9091900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagetti P, Bonofiglio L, García Gabarrot G, Kaufman S, Mollerach M, et al. Resistance to β-lactams in enterococci. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2019;51:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ram.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray BE. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:710–721. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003093421007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cetinkaya Y, Falk P, Mayhall CG. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:686–707. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.4.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang H-Y, Perencevich EN, Nair R, Nelson RE, Samore M, et al. Incidence and outcomes associated with infections caused by vancomycin-resistant enterococci in the United States: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38:203–215. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiore E, Van Tyne D, Gilmore MS. Pathogenicity of enterococci. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7:10. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0053-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beganovic M, Luther MK, Rice LB, Arias CA, Rybak MJ, et al. A review of combination antimicrobial therapy for Enterococcus faecalis bloodstream infections and infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:303–309. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller WR, Murray BE, Rice LB, Arias CA. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci: therapeutic challenges in the 21st century. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:415–439. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arias CA, Murray BE. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:266–278. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Na S, Park HJ, Park K-H, Cho O-H, Chong YP, et al. Enterococcus avium bacteremia: a 12-year clinical experience with 53 patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:303–310. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohanty S, Dhawan B, Kapil A, Das BK, Pandey P, et al. Brain abscess due to Enterococcus avium . Am J Med Sci. 2005;329:161–162. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farnsworth TA. Enterococcus avium splenic abscess: a rare bird. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:765. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00456-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki A, Matsunaga T, Aoki S, Hirayama T, Nakagawa N, et al. A pancreatic abscess 7 years after A pancreatojejunostomy for calcifying chronic pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1062–1067. doi: 10.1007/s005350200179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirzoyev Z, Anavekar N, Wilson F, Uslan D, Baddour L, et al. Enterococcus avium endocarditis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:876–878. doi: 10.1080/00365540410024754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cottagnoud P, Rossi M. Enterococcus avium osteomyelitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1998;4:290. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1998.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calça R, Gomes da Silva F, Martins AR, Branco PQ. Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis caused by Enterococcus avium . BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:e240272. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-240272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verhaegen J, Pattyn P, Hinnekens P, Colaert J. Isolation of Enterococcus avium from bile and blood in a patient with acute cholecystitis. J Infect. 1997;35:77–78. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(97)91097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishihara S, Yamada T, Yokoi S, Ito M, Yasuda M, et al. Antimicrobial activity of imipenem against isolates from complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19:565–569. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goel V, Kumar D, Kumar R, Mathur P, Singh S. Community acquired enterococcal urinary tract infections and antibiotic resistance profile in North India. J Lab Physicians. 2016;8:50–54. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.176237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Na S, Park HJ, Park K-H, Cho O-H, Chong YP, et al. Enterococcus avium bacteremia: a 12-year clinical experience with 53 patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:303–310. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones S, England R, Evans M, Soo SS, Venkatesan P. Microbiologically confirmed meningoencephalitis due to Enterococcus avium: a first report. J Infect. 2007;54:e129–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]