Abstract

Background

Aerosols and spatter are generated in a dental clinic during aerosol‐generating procedures (AGPs) that use high‐speed hand pieces. Dental healthcare providers can be at increased risk of transmission of diseases such as tuberculosis, measles and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) through droplets on mucosae, inhalation of aerosols or through fomites on mucosae, which harbour micro‐organisms. There are ways to mitigate and contain spatter and aerosols that may, in turn, reduce any risk of disease transmission. In addition to personal protective equipment (PPE) and aerosol‐reducing devices such as high‐volume suction, it has been hypothesised that the use of mouth rinse by patients before dental procedures could reduce the microbial load of aerosols that are generated during dental AGPs.

Objectives

To assess the effects of preprocedural mouth rinses used in dental clinics to minimise incidence of infection in dental healthcare providers and reduce or neutralise contamination in aerosols.

Search methods

We used standard, extensive Cochrane search methods. The latest search date was 4 February 2022.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials and excluded laboratory‐based studies. Study participants were dental patients undergoing AGPs. Studies compared any preprocedural mouth rinse used to reduce contaminated aerosols versus placebo, no mouth rinse or another mouth rinse. Our primary outcome was incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers and secondary outcomes were reduction in the level of contamination of the dental operatory environment, cost, change in mouth microbiota, adverse events, and acceptability and feasibility of the intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors screened search results, extracted data from included studies, assessed the risk of bias in the studies and judged the certainty of the available evidence. We used mean differences (MDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) as the effect estimate for continuous outcomes, and random‐effects meta‐analysis to combine data

Main results

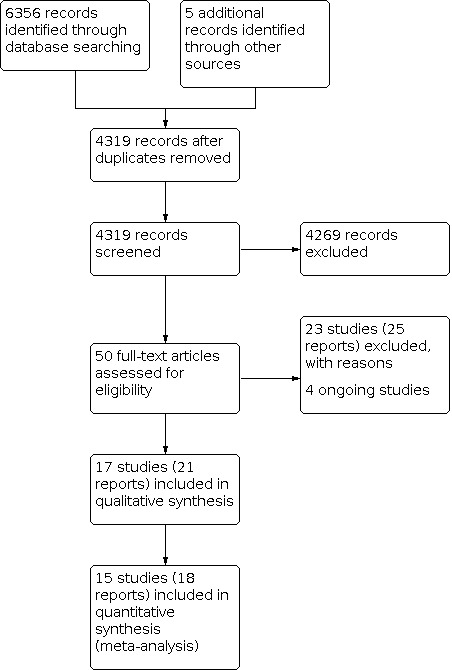

We included 17 studies with 830 participants aged 18 to 70 years. We judged three trials at high risk of bias, two at low risk and 12 at unclear risk of bias.

None of the studies measured our primary outcome of the incidence of infection in dental healthcare providers.

The primary outcome in the studies was reduction in the level of bacterial contamination measured in colony‐forming units (CFUs) at distances of less than 2 m (intended to capture larger droplets) and 2 m or more (to capture droplet nuclei from aerosols arising from the participant's oral cavity). It is unclear what size of CFU reduction represents a clinically significant amount.

There is low‐ to very low‐certainty evidence that chlorhexidine (CHX) may reduce bacterial contamination, as measured by CFUs, compared with no rinsing or rinsing with water. There were similar results when comparing cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) with no rinsing and when comparing CPC, essential oils/herbal mouthwashes or boric acid with water. There is very low‐certainty evidence that tempered mouth rinses may provide a greater reduction in CFUs than cold mouth rinses. There is low‐certainty evidence that CHX may reduce CFUs more than essential oils/herbal mouthwashes. The evidence for other head‐to‐head comparisons was limited and inconsistent.

The studies did not provide any information on costs, change in micro‐organisms in the patient's mouth or adverse events such as temporary discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction or hypersensitivity. The studies did not assess acceptability of the intervention to patients or feasibility of implementation for dentists.

Authors' conclusions

None of the included studies measured the incidence of infection among dental healthcare providers. The studies measured only reduction in level of bacterial contamination in aerosols. None of the studies evaluated viral or fungal contamination. We have only low to very low certainty for all findings. We are unable to draw conclusions regarding whether there is a role for preprocedural mouth rinses in reducing infection risk or the possible superiority of one preprocedural rinse over another. Studies are needed that measure the effect of rinses on infectious disease risk among dental healthcare providers and on contaminated aerosols at larger distances with standardised outcome measurement.

Keywords: Humans; Chlorhexidine; Chlorhexidine/therapeutic use; Communicable Diseases; Communicable Diseases/drug therapy; Health Personnel; Mouthwashes; Mouthwashes/therapeutic use; Oils, Volatile; Respiratory Aerosols and Droplets; Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; Water

Plain language summary

Does use of mouth rinse before a dental procedure reduce the risk of infection transmission from patient to health professional?

Why is this question important?

Many dental procedures generate droplets that settle on a surface quickly. If high‐speed instruments, such as a drill, are used, aerosols are generated, which consist of tiny particles that remain suspended in the air and that can be inhaled or that settle farther away on surfaces. These aerosols contain a variety of micro‐organisms and may transmit infections either through direct contact or indirectly through the contaminated surfaces. To prevent the spread of infection, it may help to reduce the number of micro‐organisms that are present in these aerosols. The use of mouth rinses before a dental procedure ('preprocedural mouth rinse') has been suggested as a possible way to reduce the amount of contamination of these aerosols. Chlorhexidine, povidone iodine and cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) are some of the commonly used mouth rinses. They act by killing or inactivating the micro‐organisms in the mouth and thereby reducing the level of contamination in the aerosol that is generated. We wanted to find out whether rinsing the mouth before a dental procedure reduces the contamination of aerosols produced during dental procedures in practice and helps prevent the transmission of infectious diseases.

How did we identify and evaluate the evidence?

We searched for all relevant studies that compared mouth rinses used before dental procedures against placebo (fake treatment), no intervention or another mouth rinse considered to be inactive. We then compared the results, and summarised the evidence from all the studies. Finally, we assessed our confidence in the evidence. To do this, we considered factors such as the way studies were conducted, study sizes and consistency of findings across studies.

What did we find?

We found 17 studies that met our inclusion criteria. These studies used chlorhexidine, CPC, essential oil/herbal mouth rinses, povidone iodine and boric acid in comparison to no rinsing, or rinsing with water, saline (salt water) or another mouth rinse. None of the studies measured the how often dental healthcare providers became infected with micro‐organisms. All the included studies measured the level of bacterial contamination in droplets or aerosols in the dental clinic. They did not examine contamination with viruses or fungi.

Most rinses decreased bacterial contamination in aerosols to some extent, but there was considerable variation in the effects and we do not know what size of reduction is necessary to reduce infection risk.

The studies did not provide any information on costs, change in micro‐organisms in the patient's mouth or side effects such as temporary discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction or hypersensitivity. The studies did not assess whether patients were happy to use a mouth rinse or whether it was easy for dentists to implement.

Overall, the results suggest that using a preprocedural mouth rinse may reduce the level of bacterial contamination in aerosols compared with no rinsing or rinsing with water, but we have only low or very low certainty that the evidence is reliable and we do not know how this reduction in contamination relates to the risk of infection.

What does this mean?

We have very little confidence in the evidence, and further studies may change the findings of our review. No studies measured infection risk or investigated viral or fungal contamination.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The evidence in this Cochrane Review is current to February 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Chlorhexidine compared to no rinsing for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic.

| Chlorhexidine compared with no rinsing for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental healthcare professionals treating them Settings: university hospital Intervention: CHX Comparison: no rinsing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no rinsing | Risk with CHX | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level | High heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis (I² = 89%; 2 studies) | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CHX: chlorhexidine; CI: confidence interval. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

Summary of findings 2. Chlorhexidine compared to water for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic.

| Chlorhexidine compared to water for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental healthcare professionals treating them Setting: university hospital Intervention: CHX Comparison: water (distilled) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with distilled water | Risk with CHX | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – combined patient and operator level | The range of mean reduction in level of contamination was 114.7 to 1963 CFUs | MD 632.94 CFUs lower (1267.33 lower to 1.45 higher) | — | 80 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | Since heterogeneity was high (I² = 92%), we repeated the sensitivity analysis by removing Reddy 2012, which used 0.2% CHX (the other 2 studies used 0.12% CHX). The result was MD 956.11 CFUs lower (95% CI 1626.04 lower to 286.19 lower). |

| Reduction in the level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – combined operator, assistant and patient level | The mean reduction in the level of contamination was 114.7 CFUs | MD 101.1 CFUs lower (107.01 lower to 95.19 lower) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | Study compared tempered CHX vs distilled water. |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CHX: chlorhexidine; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to inconsistency. bDowngraded one level due to imprecision. cDowngraded one level due to risk of bias.

Summary of findings 3. Chlorhexidine compared to saline for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic.

| Chlorhexidine compared to saline for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental care professionals treating them Setting: university hospital Intervention: CHX Comparison: saline | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with saline | Risk with CHX | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level | The mean reduction in the level of contamination was 46.5 CFUs | MD 21.33 CFUs lower (36.80 lower to 5.86 lower) | — | 12 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Reduction in the level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CHX: chlorhexidine; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to serious risk of bias. bDowngraded two levels due to serious imprecision.

Summary of findings 4. Chlorhexidine compared to essential oils/herbal mouthwashes for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic.

| Chlorhexidine compared to essential oils/herbal mouthwashes for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental care professionals treating them Setting: university hospital Intervention: CHX Comparison: essential oils/herbal mouthwash | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with essential oils/herbal mouthwash | Risk with CHX | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level | The mean reduction in level of contamination ranged from 24.68 to 56.2 CFUs |

MD 23.09 CFUs lower (34.4 lower to 11.78 lower) |

— | 76 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The studies compared 0.2% CHX to tea tree essential oil, herbal mouthwash A and herbal mouthwash B (see Table 5). |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – assistant level | The mean reduction in the level of contamination ranged from 19.25 to 26 CFUs | MD 12.21 CFUs lower (15.58 lower to 8.83 lower) | — | 76 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The studies compared 0.2% CHX to tea tree essential oil, herbal mouthwash A and herbal mouthwash B (see Table 5). |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CHX: chlorhexidine; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. bDowngraded one level due to imprecision.

1. Details of essential oil and herbal mouth rinses.

| Study | Intervention name in study | Composition |

| Bay 1993 | Essential oil mouthwash C | Listerine (active ingredients: menthol (mint) 0.042%, thymol (thyme) 0.064%, methyl salicylate (wintergreen) 0.06%, and eucalyptol (eucalyptus) 0.092%) |

| Gupta 2014 | Herbal mouthwash B | Natural herb bibhitaki (terminilia bellirica) 10 mg, Nagavalli (Piper betle) 10 mg, peelu (Salvadora persica) 5 mg, powders peppermint satva (mentha spp) 1.6 mg, yavani satva (caraway) 0.4 mg, oils gandhapura taila (wintergreen) 1.2 mg and cardamom 0.2 mg |

| Nayak 2020 | Herbal mouthwash A | Befresh, which contains cinnamomum zeylanicum, mentha spicata, syzygium aromaticum, and eucalyptusglobulus |

| Shetty 2013 | Essential oil mouthwash A | Tea tree oil |

| Suresh 2011 | Essential oil mouthwash B | Eucalyptol + thymol + methyl salicylate + menthol |

Summary of findings 5. Chlorhexidine compared to povidone iodine for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic.

| Chlorhexidine compared to povidone iodine for reduction in the level of contamination in aerosols | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental care professionals treating them Setting: university hospital Intervention: CHX Comparison: povidone iodine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with povidone iodine | Risk with CHX | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level (aerobic cultures) | The range of mean reduction in level of contamination was 30 to 52 CFUs | MD 10.75 CFUs lower (26.24 lower to 4.74 higher) | — | 52 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level (aerobic and anaerobic cultures combined) | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 35.4 CFUs | MD 4.7 CFUs lower (7.01 lower to 2.39 lower) | — | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | — |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – aerobic cultures | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 18.5 CFUs | MD 0.20 CFUs higher (7.28 lower to 7.68 higher) | — | 40 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – anaerobic cultures | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 19.5 CFUs | MD 0.8 CFUs lower (11.65 lower to 10.05 higher) | — | 40 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CHX: chlorhexidine; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to risk of bias. bDowngraded two levels due to imprecision. c Downgraded one level due to risk of bias.

Summary of findings 6. Chlorhexidine compared to cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic.

| Chlorhexidine compared to cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental care professionals treating them Setting: university hospital Intervention: CHX Comparison: CPC | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with CPC | Risk with CHX | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 62.2 CFUs | MD 2.20 CFUs lower (9.07 lower to 4.67 higher) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Tempered CHX vs tempered CPC |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – assistant | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 38.7 CFUs | MD 0.20 CFUs lower (6.30 lower to 5.90 higher) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Tempered CHX vs tempered CPC |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator | The range of mean reduction in level of contamination was 6.9 to 71.5 CFUs | MD 4.43 CFUs higher (2.27 lower to 11.13 higher) | — | 50 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Cold CHX vs cold CPC |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – assistant | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 47.3 CFUs | MD 8.80 CFUs higher (2.70 higher to 14.90 higher) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Cold CHX vs cold CPC |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 71.5 CFUs | MD 11.50 CFUs lower (18.37 lower to 4.63 lower) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Tempered CHX vs cold CPC |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – assistant | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 47.3 CFUs | MD 8.80 CFUs lower (14.90 lower to 2.70 lower) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Tempered CHX vs cold CPC |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 62.2 CFUs | MD 13.60 CFUs higher (6.73 higher to 20.47 higher) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Cold CHX vs tempered CPC |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – assistant | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 38.7 CFUs | MD 17.40 CFUs higher (11.30 higher to 23.50 higher) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Cold CHX vs tempered CPC |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 61 CFUs | MD 30 CFUs lower (85.86 lower to 25.86 higher) | — | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | CHX vs CPC+Zn+F (CPC plus zinc and sodium fluoride) |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CHX: chlorhexidine; CI: confidence interval; CPC: cetylpyridinium chloride; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. bDowngraded two levels due to imprecision. cDowngraded one level due to inconsistency,

Summary of findings 7. Tempered chlorhexidine compared to non‐tempered chlorhexidine for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic.

| Tempered chlorhexidine compared to non‐tempered chlorhexidine for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental care professionals treating them Setting: university hospital Intervention: tempered CHX Comparison: non‐tempered CHX | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐tempered CHX | Risk with tempered CHX | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 75.8 CFUs | MD 15.8 CFUs lower (22.67 lower to 8.93 lower) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – assistant level | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 56.1 CFUs | MD 17.60 CFUs lower (23.70 lower to 11.50 lower) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – combined | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 24.4 CFUs | MD 10.80 CFUs lower (15.15 lower to 6.45 lower) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Reduction in the level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. bDowngraded two levels due to imprecision.

Background

The use of high‐speed hand pieces, ultrasonic scalers and similar devices in dental clinics contributes to the generation of contaminated aerosols and spatter (Meng 2020), which have the potential to harbour harmful viral, bacterial and fungal organisms, and can be a source of infection (Mosaddad 2019). Over 700 microbial species have been detected in saliva, including the recent coronavirus‐19 (COVID‐19) virus; though they become diluted in the water during aerosol‐generating procedures (AGPs), they may pose a risk of infection in dental healthcare providers (Li 2020; To 2020). Such contaminated aerosols and spatter generated during dental procedures can also remain suspended in the air or settle on surfaces in a dental clinic (Laheij 2012), through which the transmission of diseases such as tuberculosis, measles and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) can occur directly through inhalation of these droplets or aerosols, or indirectly from contact with contaminated surfaces (Harrel 2004). The droplets generated during coughing, sneezing and speaking are usually larger than 5 μm in diameter and settle in the near vicinity (less than 1 m), whereas bioaerosols produced during AGPs remain afloat for a considerable amount of time and spread virulent pathogens over a distance of 1.8 m, causing potential risk to dental healthcare providers and patients (Jones 2015).

In March 2020, the highly pathogenic and transmissible COVID‐19 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2)) virus emerged and spread rapidly around the world. Due to the unknown modes of transmission and uncertainty in the management of the viral infection, most dental practices were suspended across the globe (Fallahi 2020; Hughes 2020). Clinical studies with a small sample size have evaluated body fluids of people with COVID‐19 and reported remarkably high levels of SARS‐CoV‐2 in saliva and the oropharynx (Jeong 2020; Yoon 2020), pointing towards a potential source of infective aerosols during dental treatment of SARS‐CoV‐2‐positive people.

One study on the impact of adhering to infection control guidelines by 2195 dentists in the USA showed that the existing infection control recommendations may be sufficient to prevent COVID‐19 infection in dental settings (Estrich 2020). This could be attributed to the adherence of dentists to currently recommended Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) infection prevention and control guidelines such as disinfection (99.1%), using personal protective equipment (PPE) (85.2%), COVID‐19 screening (98.5%), use of masks by staff members (99.1%), social distancing (98.9%), preprocedural mouth rinse (12%) and use of extraoral suction (4%). It can be assumed that any intervention to reduce the ambient microbial load during AGPs would further mitigate the risk of infection transmission.

In view of this, organisations such as the UK's Faculty of General Dental Practice (FGDP) and the CDC published strict guidelines for safe and effective practice including preprocedural mouth rinsing (CDC 2020; FGDP 2020). Yoon 2020 reported a short‐term reduction of SARS‐CoV‐2 viral load in saliva following chlorhexidine (CHX) mouth rinse. One randomised control trial in 2021 involving 16 SARS‐CoV‐2‐positive patients showed sustained reduction in viral loads with the use of two commercially available mouth rinses (Seneviratne 2021).

In vitro studies have provided some evidence on commercially available oral rinses reducing the viral load including that of SARS‐CoV‐2 (Bidra 2020; Meister 2020), and other enveloped viruses such as SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV, influenza A, parainfluenza, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B, herpes simplex virus type‐1, herpes simplex virus type‐2, human immunodeficiency virus‐1 and human papilloma virus (HPV) (Reis 2021). Effect of mouth rinses on viral load may not always correlate with their effect on the infectivity (replicating virus) of the viral culture (Gottsauner 2020). This advocates for a systematic evaluation of available clinical trials utilising these oral rinse formulations in prevention of infection transmission through contaminated aerosols.

Interventions that could possibly reduce the volume of aerosols generated during dental procedures, or their level of contamination, are evaluated in one Cochrane rapid review (Nagraj 2020). Our planned Cochrane Review will complement Nagraj 2020 by exploring the available evidence on the effectiveness and safety of preprocedural mouth rinses for preventing transmission of infectious diseases in a dental clinic.

Description of the condition

Dental AGPs are used during endodontic treatment, periodontal and restorative procedures involving the use of high‐speed hand pieces, ultrasonic scalers and high‐pressure air syringes, which are responsible for most aerosols generated in a dental clinic (Barnes 1998; Eliades 2020; Gross 1992; Harrel 2004; Veena 2015). The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) have categorised AGPs as those procedures that will produce aerosol particles such as ultrasonic scaling, using high‐speed air rotor and air polishing (Group A), that may produce aerosol particles such as slow‐speed/electric hand piece, prophylaxis with pumice, 3‐in‐1 syringe (either air or water) and diathermy (Group B) and that may produce spatter but are unlikely to produce aerosol particles such as dental examination without the use of 3‐in‐1 syringe, dental extraction, impression and intraoral radiography (Group C) (SDCEP 2021). However, there is no global consensus on the list of dental procedures that can be considered AGPs (Jackson 2020).

Some dental procedures can indirectly generate aerosols by agitating the airway (e.g. intraoral radiography or maxillary impressions). These procedures may induce the patient to cough forcibly, thereby releasing aerosols filled with microbes (Mair 2020). However, AGPs have been more commonly attributed to cross‐infection in dentistry (Chanpong 2020; Harrel 2004). While performing AGPs, the quantifiable risk of disease transmission is based on patient factors (i.e. whether they are infected with, or the carrier of, any disease), virulence of the pathogenic micro‐organism, type of procedure, duration of procedure, ability to employ mitigation factors such as aerosol‐reducing interventions and the probability of success of the intervention (Koletsi 2020). Bacteria can multiply rapidly by replicating their DNA, unlike most viruses that need entry into a living cell (such as a human cell) to be able to reproduce (Munita 2016). This is of significance in a compromised host that has increased susceptibility to allow micro‐organisms to colonise, replicate and survive.

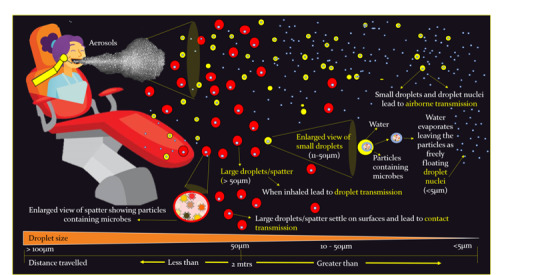

Considering that dental treatment involves close contact between the patient and the treating dentist, any type of aerosol that is generated can lead to cross‐infection, and minimising the number of contaminated aerosols generated is key to infection control (Eliades 2020; Zemouri 2017). The aerosols generated can be differentiated into spatter, droplet and droplet nuclei, based on the particle size (Harrel 2004; Mair 2020). 'Spatter' are the larger droplets that are greater than 50 µm in diameter and are airborne for only a brief period of time (Wells 1934). The smaller 'droplets' remain suspended in the air for varying amounts of time, after which the water content evaporates, leaving the solid particles called 'droplet nuclei' (5 µm or less) to freely float in the air (Harrel 2004; James 2016; Mair 2020). The smaller droplets and droplet nuclei are responsible for airborne transmission of infectious diseases (James 2016) (Figure 1). In addition to pathogenic and non‐pathogenic bacteria, viruses and other micro‐organisms, bioaerosols also contain components of plaque, nasopharyngeal and oral secretions, and traces of materials used in dental procedures (Eliades 2020; Zemouri 2017).

1.

Aerosols and spatter generated in the dental clinic. mtrs: metres.

Description of the intervention

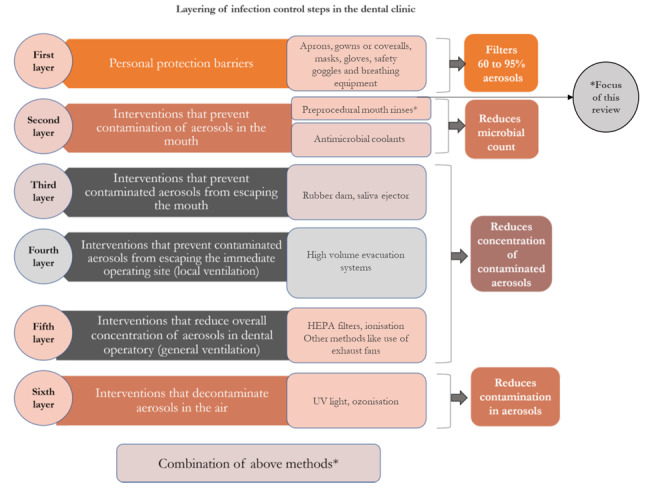

The chain of spread of infection consists of a reservoir, portal of exit from the reservoir (such as aerosols), an infectious agent, a susceptible host and a portal of entry into the host through a nasal or oral cavity (Mupparapu 2019). 'Infective dose' is of relevance when it comes to transmission of infectious diseases, and any technique that mitigates this dose would be beneficial in dental procedures (Li 2004). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that any strategy used for reducing the viable microbial content of aerosols could lower the risk of cross‐contamination in the dental setting (Fine 1992). Preprocedural mouth rinses would supplement this endeavour, along with PPE, rubber dam isolation, high‐volume suction, high‐efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, UV lights, and ozonisation. The layering of infection control steps, as described by Harrel 2004, reduces risk with ultimate aim of breaking the transmission chain, preventing cross‐infection, and ensuring safe and effective dental practice. Most of the tested oral rinses have shown broad‐spectrum antibacterial, antimicrobial and virucidal properties (Corner 1988; Meister 2020). A detailed infographic is presented in Figure 2 (Nagraj 2020).

2.

Layering of infection control steps in the dental clinic. HEPA: high‐efficiency particulate air; UV: ultraviolet.

Layering of infection control steps

Layer 1: personal protective barriers

PPE includes masks or respirators, gowns or coveralls, protective eye wear and face shields that reduce and protect from exposure to aerosols. A Cochrane Review evaluated the use of PPE for infection control (Verbeek 2020). Hence this intervention is not included in this review.

Layer 2: preprocedural rinses and antimicrobial coolants

Layer 2 involves interventions such as preprocedural use of mouth rinses and antimicrobial coolants that prevent contamination of aerosols in the mouth. Antimicrobial agents such as CHX and povidone iodine are used as coolants along with ultrasonic scalers. The effectiveness of antimicrobial coolants is presented in a Cochrane Review (Nagraj 2020). The use of preprocedural mouth rinses is included in this review and is described in the next section of this review.

Layers 3, 4, 5 and 6

Layers 3, 4, 5 and 6 are interventions that prevent contaminated aerosols from escaping the mouth (e.g. rubber dam and saliva ejector), prevent contaminated aerosols from escaping the immediate operatory (e.g. high‐volume evacuation), reduce overall concentration of aerosol in the operatory using HEPA filters, and that decontaminate aerosols in air (such as UV light and ozonisation), respectively. The effectiveness of these interventions to reduce contaminated aerosols in a dental operatory is evaluated in another Cochrane Review (Nagraj 2020).

How the intervention might work

Chlorhexidine

CHX, chemically a bisbiguanide, is considered as a gold standard disinfectant in dentistry (Mandel 1994). It is a superior antiplaque agent with broad antimicrobial spectrum that includes gram‐positive and gram‐negative organisms, certain bacterial spores, lipophilic viruses, yeasts and dermatophytes (Jones 1997; Mandel 1994). This mouth rinse is commercially available in concentrations of 0.12% to 0.2% of CHX gluconate, with or without alcohol (Ciancio 2000). Although some studies on the virucidal effects of CHX against SARS‐CoV and related viral infections under biologically mimicked conditions have shown proven benefit (Yoon 2020), other studies have reported no antiviral property with the use of CHX (Jones 1997; Marui 2019; Meister 2020).

The most important property of CHX is the intrinsic ability to be retained by the oral surfaces and released gradually into the oral cavity over a period of time (Carrilho 2010). Staining of teeth and gingiva has been reported with use of CHX for more than seven days, except in formulations that contain polyvinylpyrrolidone in addition to CHX (Tartaglia 2019). Taste alteration and increased calculus formation are other reported adverse effects (Ciancio 2000).

Cetylpyridinium chloride

Cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) is a cationic quaternary ammonium with broad‐spectrum antimicrobial and antiviral properties (Popkin 2017). It acts by penetrating the cell wall of organisms causing lysis and destruction. It is a surface‐active agent specifically active against gram‐positive organisms and yeast. It is commercially available in concentrations ranging from 0.05% to 0.10%. It is an established antiplaque agent and is used as an adjuvant in mild‐to‐moderate gingivitis (Ciancio 2000).

Essential oils

Essential oils are plant extracts obtained by distillation or cold press and are mixed with a carrier oil base to be used commercially. They are powerful antioxidants with regenerating, oxygenating and immune‐strengthening properties (Araujo 2015). Tea tree oil, helichrysum oil, chamomile oil, clove oil, eucalyptus oil and lavender oil are commonly used. Generally, mouth rinses contain oil of thymol, menthol, eucalyptol, and methyl salicylate in a hydroalcohol solution (Claffey 2003). Essential oils have antimicrobial properties and work by killing planktonic and biofilm‐associated bacteria and a broad spectrum of bacteria and yeasts associated with halitosis, gingivitis and periodontitis. They disrupt bacterial cell membranes and cell walls, inhibit bacterial growth and development, inhibit glucosyltransferase enzymes, reduce extracellular polysaccharide formation, and reduce plaque endotoxin levels (Alshehri 2018; Araujo 2015). Essential oils have also shown antiviral properties by causing capsid disintegration and viral expansion and thus making them ineffective (Wani 2021).

Herbal mouth rinses

Herbal mouth rinses are available as non‐prescription medications, and are widely used due to the belief that alternative or complementary therapy offers no or minimal adverse effects (Sridharan 2016). Botanical sources such as neem, basil, lemon grass, chamomile, linseed, leaf extracts such as from Carica papaya or guava leaf, peppermint, turmeric (Cai 2020), and green propolis (Pedrazzi 2015) have been incorporated into aqueous solutions to be used as mouth rinses. These are phytotherapeutic plants, containing a mixture of active agents such as catechins, tannins and sterols (Manipal 2016). These mouth rinses from botanical sources have been shown to have significant effects on both gram‐positive and gram‐negative organisms, including Escherichia coli, Streptococcus species and Salmonella species (Dua 2015). They possess significant antimicrobial and superoxide scavenging properties, leading to reduction in the bacterial load, decrease in overall inflammation and reduction in oxidative stress, ultimately leading to healing and recovery (Dua 2015; Mathur 2018).

Povidone iodine

Povidone iodine is a broad‐spectrum antimicrobial agent with established in vitro efficacy against many gram‐positive and gram‐negative bacteria including mycobacteria; bacterial spores; and a wide range of enveloped and non‐enveloped viruses, fungi and protozoa (Kanagalingam 2015). The microbicidal action of povidone iodine is related to the non‐complexed, freely mobile elemental iodine (Kanagalingam 2015). This activated iodine reacts in electrophilic reactions with enzymes of the respiratory chain as well as with amino acids from the cell membrane proteins both located in the cell wall. As a result, the well‐balanced tertiary structure necessary for maintaining the respiratory chain is destroyed and the micro‐organism is irreversibly damaged (Eggers 2018).

There were significant reductions in SARS‐CoV‐2 viral load when povidone iodine mouth rinse was tested under biologically mimicked conditions (Meister 2020). Povidone iodine as gargles and throat sprays demonstrated rapid virucidal activity against coronavirus strains, especially SARS‐CoV, after 10 seconds' exposure (Kariwa 2004). The exposure of 120 seconds was effective against Candida albicans that reduced the overall treatment cost of fungal infections (Kanagalingam 2015).

C31G

C31G is an equimolar mixture of alkyl dimethylglycine and alkyl dimethyl amine oxide that is buffered with citric acid (Corner 1988). It is a surface‐active agent effective against gram‐positive and gram‐negative bacteria and is used in a concentration of 0.5%. It acts by inhibition of bacterial glycolysis, bacterial adherence and low minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) against a host of microbes (Corner 1988).

Hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide in low concentrations is used in mouth rinses, dentifrices and teeth‐whitening agents (Mandel 1994; Walsh 2000). Commercially available mouth rinses contain 1% to 3% of hydrogen peroxide (Hossainian 2011). Being a strong oxidising agent, it exerts good antimicrobial effects against gram‐positive and gram‐negative organisms. Nevertheless, there is no evidence to support the use of hydrogen peroxide mouth rinses as an antiviral agent (Ortega 2020).

Saline

Saline is known to have antibacterial properties. One study using home‐made saline with a concentration of 2% and 5.8% showed marked activity on gram‐positive bacteria and the antibacterial effect for a 2% solution lasted three hours and for a 5.8% solution lasted five hours (Nokam Kamdem 2022). Nokam Kamdem and colleagues found the 5.8% saline to be as effective as 0.1% CHX.

Ozonated water

Ozone (O3) is an allotropic form of oxygen and has the ability to oxidise organic material. Because of this property, it has been topically used to reduce infections affecting the oral cavity (Nagayoshi 2004).

Boric acid

Boric acid 0.75% to 3% has been used as antimicrobial and antifungal agent because of its potential fungicidal and bacteriostatic action. It contains AN0128, a boron‐containing compound that has demonstrated antimicrobial and anti‐inflammatory properties (Luan 2008), and has been successfully used in the field of dentistry as irrigation agent to reduce the periodontal pocket depth in people with periodontitis (Sağlam 2013).

Why it is important to do this review

Although aerosols produced during AGPs in the dental clinic have always been considered a potential threat for transmission of diseases among dentists and dental personnel, there are virtually no documented transmission episodes of any of these through dental practices. This concern of transmission has become even more important in the context of the current pandemic challenge posed by COVID‐19. Epidemics such as those of SARS, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and now COVID‐19 warrant superior infection control practices in dental clinics to sustain and provide necessary services during challenging times (Meng 2020). People attending dental clinics can cough, sneeze or undergo dental procedures that aerosolise dental materials, saliva and blood along with micro‐organisms. People who are infected can be in the incubation period, be asymptomatic or choose to conceal their infection (Meng 2020). Hence, it is the duty of healthcare professionals to take necessary precautions to the highest possible level.

Following the suspension of most dental practices due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, strict infection control guidelines are being proposed by major governing bodies across the world in order to resume routine practices, without which people with oral health problems will go untreated, and dental practices will have financial impact (CDC 2020; FGDP 2020). CDC guidelines recommend that dental settings need to balance providing necessary services to patients while minimising the risk of transmission of infectious diseases in the dental clinic. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) classified dentists as in the very high‐risk category due to the potential exposure to pathogenic micro‐organisms through AGPs. Also, according to the US Department of Labor, dental hygienists have the highest occupational risk at 99.7%, followed by the dental assistants at 92.5% and general dentists at 92.1%.

With current concerns about the transmission of infectious diseases and cross‐contamination in the dental setting, several methods have been proposed to reduce the risk of infection spread. Use of mouth rinses by the patient before the commencement of any dental procedure has been proposed and tested in various clinical and laboratory studies as a possible measure to reduce the amount of contamination in the aerosols generated during AGPs (Fine 1996; Hunter 2014; Joshi 2017). In one recently published rapid review on AGPs and their mitigation in International Dental Guidance documents, 82% (51/63) of documents recommended preprocedural mouth rinse for people without COVID; however, only 10/51 documents provided references to support the recommendation (Clarkson 2020). Different types of mouth rinses are commercially available, but there is uncertainty regarding the use of these preprocedural mouth rinses as we do not know if they are effective for preventing the risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols, and if so, whether one might work better than another. This review may help dental professionals prepare themselves to adopt best practices to reduce the risk of infection and help in the reduction of contaminated aerosols.

Objectives

To assess the effects of preprocedural mouth rinses used in dental clinics to minimise incidence of infection in dental healthcare providers and reduce or neutralise contamination in aerosols.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) either with parallel arm or cluster‐RCT design in dental patients. We included cross‐over design for secondary objectives but planned to include first‐period data from cross‐over trials as parallel‐arm studies. We excluded quasi‐RCTs, split‐mouth studies, controlled clinical trials and experimental studies conducted in a laboratory environment.

Types of participants

We included studies with dental patients undergoing AGPs.

Types of interventions

We included any preprocedural rinse that aimed to reduce contaminated aerosols in dental clinics, compared to placebo, no mouth rinse or another mouth rinse. We excluded studies that combined preprocedural rinse with other methods to reduce the aerosols, as this is beyond the scope of the review.

Types of outcome measures

We could not find any recommended core outcomes related to this review published in the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative (COMET 2020). Hence, the review authors decided on the outcomes by consensus.

Primary outcomes

Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers (dentists, dental surgery assistants, dental hygienists, dental technologists, dental laboratory staff, dental aides or trainee students)

Measurement of outcomes: whether a participant infected any dental healthcare provider; if so, we planned to count it as one event.

Secondary outcomes

Reduction in the level of contamination by particles larger than 5 µm (droplets) at distances of less than 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment

Reduction in the level of contamination by particles of 5 µm or less (droplet nuclei) at distances of 2 m or more from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment

Cost

Change of microbiota in the patient's mouth

Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity

Acceptability and feasibility of the intervention to patients and dental healthcare providers

Measurement of outcomes: we planned to measure the reduction in the level of contamination using colony‐forming units (CFUs), where the samples could be collected with culture plates, or the results of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or index of microbial air contamination (IMA). We planned to measure cost in GBP or USD, and change of microbiota using CFUs or viral load. Adverse events are described qualitatively. Acceptability and feasibility of the interventions was to be measured using ordinal (e.g. Likert scale) or dichotomous (e.g. yes/no) data.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions:

Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register (searched 4 February 2022) (Appendix 1);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Register of Studies (searched 4 February 2022) (Appendix 2);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 4 February 2022) (Appendix 3);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 4 February 2022) (Appendix 4);

World Health Organization COVID‐19 Global Literature on Coronavirus Disease Database (search.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov) (searched 4 February 2022) (Appendix 5);

Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register (covid-19.cochrane.org/) (searched via the Cochrane Register of Studies) (searched 4 February 2022) (Appendix 6).

Subject strategies were modelled on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE Ovid, presented in Appendix 3. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategies designed by Cochrane for identifying RCTs as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Technical Supplement to Chapter 4 (Lefebvre 2020). We also used a search filter to identify non‐randomised studies, as presented in Waffenschmidt 2020.

Searching other resources

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist searched the following trials registries to identify ongoing studies:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/) (searched 4 February 2022) (Appendix 7);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch) (searched 4 February 2022) (Appendix 8).

We searched the reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews for further studies.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects.

We checked to ensure that none of the included studies were retracted due to error or fraud.

We contacted the original authors for clarification and further data if trial reports were unclear.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts. The search was designed to be sensitive and include controlled clinical trials, these were filtered out early in the selection process if they were not randomised. We resolved any conflicts during the screening process by discussion. If this was not possible, we consulted a third review author (arbiter) and reached consensus through discussion. We used online Rayyan software to screen the titles and abstracts (Rayyan 2016).

Two review authors independently screened the full‐text articles. We resolved any conflicts during the screening by mutual discussion. If this was not possible, we consulted a third review author (arbiter) and reached consensus through discussion. For included studies, we extracted useful information and data from the full‐text articles. These are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. We also present the Characteristics of excluded studies tables, stating the reasons for the exclusion of studies.

Data extraction and management

One review author designed the data extraction form and another review author tested its suitability. Two review authors independently extracted the data using the data extraction form. We limited the data extraction to a minimal set of required data items.

Where studies had multiple publications, we collated the reports of the same study, so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest for the review. Such studies had a single identifier with multiple references.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane RoB 1 tool for RCTs, the results of which were reported in a table; Higgins 2011). For RCTs, we classified each domain as being at high, low or unclear risk of bias. We attempted to contact the trial authors if there was insufficient information or it was unclear. We resolved any disagreements by discussion between the review authors. If consensus was not reached, we consulted a third review author (arbiter).

Measures of treatment effect

We reported continuous outcomes as means differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). If the included trials reported continuous outcomes obtained from different instruments, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD) as the effect measure, with 95% CIs.

We planned to qualitatively describe the costs for the interventions used. For ordinal data, we planned to dichotomise the data and present the effect sizes as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs. We planned to present the effect sizes for dichotomous outcomes as RRs with 95% CIs. However, none of the included studies reported costs for the interventions, dichotomous and ordinal data.

Unit of analysis issues

For the primary outcome, the unit of analysis was the event of infection in any of the dental healthcare providers. For the secondary outcomes, the unit of analysis was the participant undergoing the AGP. In multi‐arm trials, we selected the relevant arms for inclusion in our analyses. If more than two arms were relevant to this review, we planned to split the control group between multiple comparisons so that participants were not double‐counted in a meta‐analysis. However, none of the meta‐analyses had this issue.

Dealing with missing data

When we encountered trials with missing data, we contacted the investigators or sponsors of these studies, if the contact author's email address was available. We calculated missing data from other data, such as standard deviations (SDs) and P values. We planned to re‐analyse the data according to the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle whenever possible. However, we did not encounter such trials.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by visually inspecting the forest plots to determine closeness of point estimates with each other and overlap of CIs. We used the Chi² test with a P value of 0.1 to indicate statistical significance. We also used the I² statistic, following the interpretation recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (0% to 40% might not be important; 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100% represents considerable heterogeneity) (Higgins 2019).

Assessment of reporting biases

If we had included 10 or more studies, we planned to construct a funnel plot to investigate any potential reporting bias. However, most of the analyses were based on fewer than 10 studies.

Data synthesis

We analysed the data using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020). In the absence of substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity, we performed meta‐analysis using the random‐effects model. If there was substantial or considerable heterogeneity, we investigated this using a subgroup analysis. Where a meta‐analysis was not appropriate, we discussed the data narratively.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to investigate heterogeneity by performing the following subgroup analyses.

Type of AGP (e.g. ultrasonic and sonic scaling, tooth preparation using air turbine hand piece or air abrasion, three‐way syringe).

Duration or dosage (or both) of mouth rinse.

Position of the culture plates (for CFU).

Type of culture media used (aerobic and anaerobic).

Type of air sampler used (Reynier's, Andersen cascade, Surface Air System sampler, Active Casella slit sampler).

Of these, we had sufficient data to conduct subgroup analyses based on position of the culture plates and type of culture media used.

Sensitivity analysis

To explore the possible effect of losses to follow‐up on the effect estimates for the secondary outcomes, we planned to perform sensitivity analyses. We planned to remove those studies at high risk of bias (studies assessed to have high risk of bias in at least one domain) and report if any there were significant differences between the results of these analyses. However, most comparisons were based on single studies, or all the included studies were at high risk of bias or we could not meta‐analyse the data due to high heterogeneity for which we had no explanation.

For dichotomous outcomes, we planned to vary the event rate within the missing participants from intervention and control groups within plausible limits. However, none of the included studies reported the outcomes dichotomously.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We planned to summarise the results of the analyses in summary of findings tables for the following outcomes, for all comparisons.

Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers.

Reduction in the level of contamination by particles larger than 5 µm (droplets) at distances of less than 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment.

Reduction in the level of contamination by particles 5 µm or less (droplet nuclei) at distances of 2 m or more from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment.

Adverse events.

However, we did not find any included studies reporting the primary outcome (incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers). Hence, we summarised the results of the analyses in summary of findings tables for the other three outcomes for seven comparisons only.

To identify the most important seven comparisons, we engaged stakeholders (four general dental practitioners and six specialists) who ranked the comparisons. We have presented the top seven comparisons identified by stakeholders as summary of findings tables (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8). For the other nine comparisons, we presented the summary of findings as additional tables (Table 9; Table 10; Table 11; Table 12; Table 13; Table 14; Table 15; Table 16; Table 17).

2. Cetylpyridinium chloride compared to no rinsing for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic.

| Cetylpyridinium chloride compared to no rinsing for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental healthcare professionals treating them Setting: university hospital Intervention: CPC Comparison: no rinsing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no rinsing | Risk with CPC | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 41.7 CFUs | MD 34.8 CFUs lower (65.92 lower to 3.68 lower) | — | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 644 CFUs | MD 583 CFUs lower (958.36 lower to 207.64 lower) | — | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | CPC+Zn+F vs no rinsing |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – combined | The range of mean reduction in level of contamination was 803.3 to 875 CFUs | MD 0.75 CFUs lower (1.32 lower to 0.18 lower) | — | 200 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | CPC formulation vs no rinsing |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CI: confidence interval; CPC: cetylpyridinium chloride; CPC+Zn+F: cetylpyridinium chloride + zinc + fluoride; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. bDowngraded two levels due to imprecision.

3. Cetylpyridinium chloride compared to water for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic.

| Cetylpyridinium chloride compared to water for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental healthcare professionals treating them Setting: university hospital Intervention: CPC Comparison: water | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with water | Risk with CPC | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 55.6 CFUs | MD 48.7 CFUs lower (67.82 lower to 29.58 lower) | — | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | CPC vs water |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 307 CFUs | MD 246 CFUs lower (437.96 lower to 54.04 lower) | — | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | CPC+ZN+F vs water |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – combined | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 569 CFUs | MD 0.78 CFUs lower (1.24 lower to 0.31 lower) | — | 105 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | CPC formulation vs water |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CI: confidence interval; CPC: cetylpyridinium chloride; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. bDowngraded two levels due to imprecision.

4. Tempered cetylpyridinium chloride compared to cold cetylpyridinium chloride for preventing risk of infection in dental healthcare providers and contamination of aerosols in dental clinic.

| Tempered cetylpyridinium chloride compared to cold cetylpyridinium chloride for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental healthcare professionals treating them Setting: university hospital Intervention: tempered CPC Comparison: cold CPC | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with cold CPC | Risk with tempered CPC | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 71.5 CFUs | MD 9.3 CFUs lower (16.17 lower to 2.43 lower) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – assistant | The mean reduction in level of contamination was 47.3 CFUs | MD 8.6 CFUs lower (14.7 lower to 2.5 lower) | — | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Reduction in level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CI: confidence interval; CPC: cetylpyridinium chloride; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. bDowngraded two levels due to imprecision.

5. Povidone iodine compared to saline for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers.

| Povidone iodine compared to saline for preventing transmission of infectious diseases through aerosols in dental healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Population: dental patients undergoing aerosol‐generating procedures and dental care professionals treating them Setting: university hospital Intervention: povidone iodine Comparison: saline | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with saline | Risk with povidone iodine | |||||

| Incidence of infection of dental healthcare providers | Not reported | |||||

| Reduction in the level of contamination by particles > 5 µm (droplets) at distances of < 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment – operator level | The mean reduction was 46.5 CFUs | MD 16.5 CFUs lower (32.65 lower to 0.35 lower) | — | 12 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Reduction in the level of contamination by particles ≤ 5 µm (droplet nuclei) at distances of ≥ 2 m from patient's oral cavity in the operative environment | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse events such as transient discolouration, altered taste, allergic reaction, hypersensitivity | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CFU: colony‐forming unit; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||