Abstract

A set of open reading frames (ORFs) potentially encoding signal transduction proteins are clustered around icfG, a gene implicated in the regulation of carbon metabolism, in the genome of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. slr1860 is the ORF for icfG, whose predicted product resembles the protein phosphatases SpoIIE, RsbU, and RsbX from Bacillus subtilis. Bracketing slr1860/icfG are (i) ORF slr1861, whose predicted product resembles the SpoIIAB, RsbT, and RsbW protein kinases from B. subtilis, and (ii) ORFs slr1856 and slr1859, whose predicted products resemble the respective phosphoprotein substrates for the B. subtilis protein kinases: SpoIIAA, RsbS, and RsbV. In order to determine whether the protein products encoded by these ORFs possessed the functional capabilities suggested by sequence comparisons, each was expressed in Escherichia coli as a histidine-tagged fusion protein and analyzed for its ability to participate in protein phosphorylation-dephosphorylation processes in vitro. It was observed that ORF slr1861 encoded an ATP-dependent protein kinase capable of phosphorylating Slr1856 and, albeit with noticeably lower efficiency, Slr1859. Site-directed mutagenesis suggests that Slr1861 phosphorylated these proteins on Ser-54 and Ser-57, respectively. Slr1860 exhibited divalent metal ion-dependent protein-serine phosphatase activity. It catalyzed the dephosphorylation of Slr1856, but not Slr1859, in vitro.

Like most cyanobacteria, Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 grows autotrophically by fixing CO2 or heterotrophically on a fixed source of carbon, such as glucose. Genetic analyses indicate that the icfG gene participates in the coordination of inorganic carbon and glucose metabolism in this cyanobacterium (4). The expression of icfG requires glucose. Inactivation of this gene severely impairs, in a glucose-dependent fashion, the ability of the cyanobacterium to successfully shift from growth on high levels of inorganic carbon to growth on low, limiting levels. For example, while icfG mutant cells cultured on high levels of inorganic carbon as a sole carbon source grow normally following a step down to low inorganic carbon, they fail to grow if glucose is added concomitant with this shift. The presence of glucose in the growth medium prior to the step down to low inorganic carbon also blocks growth of icfG mutant cells, regardless of whether glucose is present following the shift.

The determination of the complete genome sequence of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (18) revealed that icfG resides in a region of the genome rich in open reading frames (ORFs) whose predicted protein products possess regulatory potential (Fig. 1). Prominent among these is slr1860, the ORF for icfG itself, whose predicted sequence resembles that of a protein-serine/threonine phosphatase of the PPM family (1, 5, 31, 36). The predicted product of ORF slr1861 resembles a family of protein-serine/threonine kinases of Bacillus subtilis that include SpoIIAB, RsbT, and RsbW (Fig. 2), while slr1856 and slr1859 potentially encode homologs of the phosphoprotein substrates for the aforementioned B. subtilis protein kinases (Fig. 3) (36). As an integral step in determining whether carbon metabolism in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 is coordinated, in whole or in part, via protein phosphorylation-mediated signaling processes, the products of these four ORFs were expressed as fusion proteins in Escherichia coli and their abilities to participate in phosphotransfer and/or phosphohydrolase reactions were examined in vitro.

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of slr1856, slr1859, slr1860/icfG, and slr1861. Shown is the gene map from the Cyanobase database (18) outlining the relative positions of ORFs slr1856, slr1859, slr1860/icfG, and slr1861 within the complete nucleotide sequence of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. ORFs are labeled by arrows whose sizes and orientations indicate their relative lengths and the directions in which they are presumed to be transcribed. slr1857 encodes a potential homolog of GlgX, a glycogen-debranching enzyme (34). Homologs for the remaining ORFs, slr1852 to -1855 and slr1862, have yet to be identified.

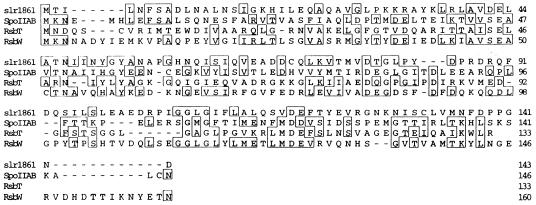

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the DNA-derived sequence of Slr1861 with the SpoIIAB, RsbT, and RsbW protein-serine or threonine kinases from B. subtilis. Shown is the deduced amino acid sequence of Slr1861 from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (18) aligned with that of the known protein-serine or threonine kinases SpoIIAB (12), RsbT (33), and RsbW (16) from B. subtilis by using the Lasergene program. Amino acid identities between two or more of the sequences shown are boxed. Dashes indicate where sequence gaps were introduced to optimize the alignment of conserved regions.

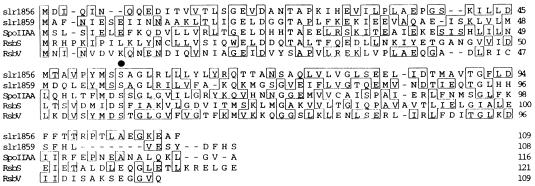

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the DNA-derived amino acid sequences of Slr1856 and Slr1859 from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 with those of known phosphoproteins from B. subtilis. Shown are the deduced amino acid sequences of Slr1856 and Slr1859 from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (18) aligned with that of the known phosphoproteins SpoIIAA (12), RsbS (33), and RsbV (16) from B. subtilis by the Lasergene program. Amino acid identities are boxed. Dashes indicate where sequence gaps were introduced to optimize alignment of conserved regions. The site phosphorylated on SpoIIAA, Ser-58, is indicated by the solid circle (24).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Standard procedures.

Protein concentrations were measured by the method of Bradford (7) with premixed reagent and a standardized solution of bovine serum albumin, both from Pierce (Rockford, Ill.). Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed as described by Laemmli (20). Gels were stained as described by Fairbanks et al. (11). Phosphoamino acid analysis was performed essentially as described by Kamps and Sefton (17).

Growth of organism and isolation of genomic DNA.

The cyanobacterial strain Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was grown with continuous aeration and lighting in BG-11 medium (26). Upon reaching the late exponential stage of growth, the cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with 500 mM Tris, pH 8.0, containing 100 mM EDTA, and stored at −70°C. Genomic DNA was isolated as described by Shi and Carmichael (29).

Oligonucleotide primers for PCR.

The sequences of the forward primers used to amplify ORFs slr1856, slr1859, slr1860/icfG, and slr1861 by PCR were 5′-CGATGGATCCCCATGGATATTCAAATTAATCAA-3′, 5′-CGATGGATCCCCATGGCTTTCAACATCGAATCG-3′, 5′-CGATGGATCCCAATGAAAATGAAACTGATTCAA-3′, and 5′-CGATGGATCCCCATGACTATTTTAAATTTTTCC-3′, respectively. In order to facilitate subsequent cloning of PCR products, the 5′ end of each forward primer contained a sequence suitable for annealing to the restriction sites formed by the cleavage of DNA with BamHI. The sequences of the reverse primers used to amplify ORFs slr1856, slr1859, slr1860/icfG, and slr1861 by PCR were 5′-CCAGCTGCAGTCCATGGTGTCCTGCTAAAATG-3′, 5′-CCAGCTGCAGTTCATTGGTTTAATTTACCAAAAGTA-3′, 5′-CCAGCTGCAGGTCATGGCACCTAATTACGGTAA-3′, and 5′-CCAGCTGCAGGCCATGAAAAAAGAAACAATAAC-3′, respectively. In order to facilitate subsequent cloning of PCR products, the 3′ end of each reverse primer contained a sequence suitable for annealing to the restriction sites formed by the cleavage of DNA with PstI.

Cloning of slr1856, slr1859, slr1860/icfG, and slr1861.

All routine molecular biological procedures were performed according to the methods of Sambrook et al. (27). The ORFs slr1856, slr1859, slr1860/icfG, and slr1861 (18) were amplified from the genomic DNA of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 by PCR. Briefly, genomic DNA (1 μg) was incubated in a volume of 50 μl containing 50 pmol of each of the appropriate forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers and 5 U of Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, each sample was subjected to 25 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min per kb of DNA to be amplified. The resulting mixture was ligated into the plasmid vector pRSET-C (Invitrogen, Portland, Oreg.) with T4 DNA ligase. This vector adds a 33-amino-acid N-terminal extension to create recombinant fusion proteins. This extension contains a hexahistidine, or His tag, sequence for purification of recombinant proteins by affinity chromatography on metal chelate columns, an epitope for the anti-Xpress antibody (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) for their detection, and an enterokinase cleavage site to facilitate proteolytic removal of the N-terminal extension. The ligation mixtures were used to transform competent cells of E. coli DH5α (Life Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). Plasmids were then isolated by conventional means. To insure the fidelity of the PCR amplification process, the ORF insert within each plasmid expression vector was sequenced on both strands by the dideoxy method of Sanger et al. (28) with a Sequenase kit (U.S. Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio).

Expression of Slr1856, Slr1859, Slr1860/IcfG and Slr1861 in E. coli and preparation of cell lysates.

Isolated plasmids (see above) were used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) from Promega (Madison, Wis.). Cultures of transformed E. coli were grown in 100 ml of Luria broth containing 50 μg of ampicillin/ml until the A600 was in the range of 0.6 to 1.0. At this point, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 0.4 mM, and the cultures were incubated overnight at 30°C. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 10 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, containing 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mg of lysozyme/ml, and 100 μg of DNase I/ml. After standing on ice for 30 min, the cells were lysed by sonic disruption and centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 30 min to remove debris and any remaining intact cells. The presence of recombinant proteins was analyzed on Western blots with the anti-Xpress antibody following the manufacturer’s protocols. The anti-Xpress antibody is directed against an epitope located within the short N-terminal extension that the pRSET-C expression vector fuses onto recombinant proteins.

Metal-chelate chromatography of recombinant proteins.

Columns of Pharmacia (Uppsala, Sweden) Fast-Flo chelating Sepharose, 0.5 by 5 cm, were charged with Ni2+ by passing 5 ml of 50 mM NiSO4 through each column. The columns were then equilibrated with 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, containing 500 mM NaCl and 5 mM imidazole (buffer A). E. coli lysates, prepared as described above, were diluted with four volumes of buffer A and applied to the columns, and the columns were washed with buffer A. The column flowthrough was collected and saved for future analysis. Adhering proteins were eluted from each column with 2.5 ml of buffer A in which the imidazole concentration was increased to 250 mM. Fractions, 0.5 ml each, were collected, and those containing high concentrations of protein were saved for future analysis.

Site-directed mutagenesis of slr1856 and slr1859.

The codon, AGC, encoding Ser-54 of the product of slr1856 was altered to that for alanine, GCC, in a copy of the ORF that had been cloned into expression vector pRSET-C with a GenEditor kit from Promega (Madison, Wis.) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The codon for Ser-57 of the product of slr1859, AGT, was altered to that for alanine, GCT, in a similar fashion. The mutagenically altered proteins were expressed as described above.

Assay of protein phosphorylation.

Portions of cell lysates or the flowthrough fractions from metal chelate columns, containing 20 μg of total protein, or the adherent fractions from metal chelate columns (13 μg) were incubated either alone or in combination for 15 min at 25°C in a volume of 20 μl containing 20 mM MES (morpholine ethanesulfonic acid), pH 6.5, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM [γ-32P]ATP (total, 4 μCi). The reaction was terminated by the addition of 5 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The entire mixture was then applied to an SDS–15% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed, and the 32P-labeled phosphoproteins were visualized by autoradiography with either Fuji (Tokyo, Japan) RX X-ray film or a Packard Instruments (Meriden, Conn.) Instantimager electronic autoradiography system.

Preparation of 32P-phosphorylated Slr1856 and Slr1859 for assays of protein phosphatase activity.

Slr1856, Slr1859, and Slr1861 were expressed in E. coli and partially purified by metal chelate chromatography as described above. Aliquots, 50 μg each, of Slr1861 protein kinase were treated with EnterokinaseMax (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocols to remove the N-terminal fusion sequence. The enterokinase was then removed by passing the material through a column of immobilized soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). The protein kinase was then mixed with either 200 μg of Slr1856 or 400 μg of Slr1859 in a volume of 1.0 ml of 20 mM MES (pH 6.5), containing 20 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM [γ-32P]ATP (750 μCi), and incubated overnight at room temperature. The phosphorylated proteins were then separated from the Slr1861 protein kinase and the unreacted [γ-32P]ATP by metal chelate chromatography as described above, with the exception that the columns were charged with ZnSO4 in place of NiSO4.

Assay of protein phosphatase activity.

Slr1860 proved refractory to purification by metal chelate chromatography. Therefore, 10 μg of protein from lysates of E. coli expressing Slr1860 were incubated at 37°C in a volume of 30 μl of 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0, containing 1 mM dithiothreitol, 3 mM MnCl2, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml, and one of the following 32P-labeled phosphoprotein substrates at the indicated concentrations: casein, 2 μM protein-bound [32P]phosphate; Slr1856, 0.5 μM protein-bound [32P]phosphate; or Slr1859, 0.5 μM protein-bound [32P]phosphate. Casein that had been phosphorylated on serine residues with [32P]phosphate was prepared as described by Kennelly et al. (19). The reaction was terminated, typically after 60 min, by the addition of 100 μl of 20% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid. The acidified solution was mixed briefly and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 3 min, and the [32P]phosphate present in a 75-μl aliquot of the supernatant fluid was determined by liquid scintillation counting in 1 ml of Scintisafe Plus 50% liquid scintillation fluid (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.). Occasionally, the identity of the reaction product as inorganic phosphate was verified by the molybdic acid extraction procedure of Martin and Doty (22), as modified by Kennelly et al. (19).

The protein phosphatase activities of PP1-cyano1, PP1-arch1, and PP1-arch2 were assayed under the same conditions as those described for Slr1860, with the exception that the quantity of protein phosphatase assayed was reduced to 1 μg, 0.1 ng, and 0.1 ng, respectively. PP1-cyano1 was expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity as described by Shi et al. (30). Purified recombinant PP1-arch1 and PP1-arch2 were prepared as described by Leng et al. (21) and Solow et al. (32), respectively. The protein phosphatase activity of Sll1387 was determined as described above, with the exception that 50 mM imidazole, pH 8, was substituted for 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0, and the quantity of protein phosphatase assayed was reduced to 1 μg. The gene for Sll1387 was cloned and expressed, and the recombinant protein was purified by metal chelate chromatography by procedures similar to those described above (28a).

RESULTS

Slr1861 phosphorylates Slr1856 in vitro.

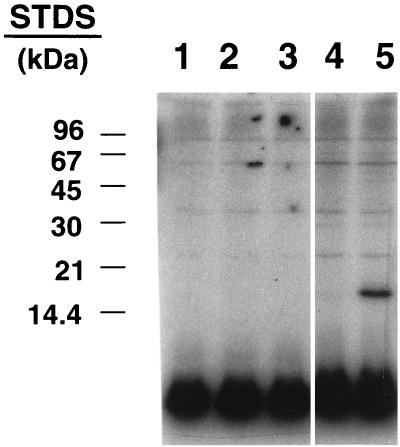

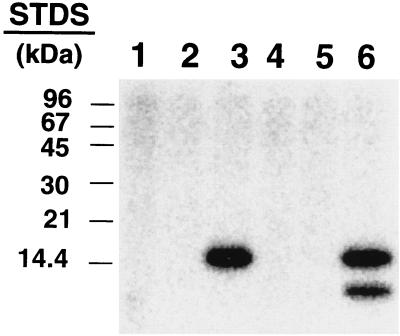

Slr1856, Slr1859, Slr1860/IcfG, and Slr1861 were expressed as fusion proteins in E. coli. The 33-amino-acid N-terminal fusion domain contained a hexahistidine (His tag) sequence to facilitate purification, an epitope for a commercial antibody, and a cleavage site for the protease enterokinase. When extracts from E. coli expressing Slr1861 were mixed with extracts from cells expressing Slr1856 and incubated with Mg2+ and [γ-32P]ATP, a prominently phosphorylated polypeptide that migrated with an apparent molecular mass of roughly 15 kDa could be detected following SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4). Phosphorylation did not take place unless extracts from cells expressing Slr1856 and Slr1861 were both present.

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylation of a ≈15-kDa polypeptide occurred when lysates from E. coli expressing Slr1861 were mixed with lysates from E. coli expressing Slr1856. ORFs slr1856 and slr1861 were expressed as histidine-tagged fusion proteins in E. coli, and lysates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Portions, containing 20 μg of total protein, of each lysate were incubated alone or in combination with [γ-32P]ATP and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described in Materials and Methods. Shown is the autoradiogram of the assay mixture following SDS-PAGE. Lane 1 contains lysate from cells transformed with vector alone. Lanes 2 and 3 contain lysate from cells expressing Slr1861 and Slr1856, respectively. Lane 4 contains lysate from cells transformed with vector alone combined with lysate from cells expressing Slr1856. Lane 5 contains lysate from cells expressing Slr1861 to which lysate from cells expressing Slr1856 was added. The positions of protein standards (STDs) are indicated at the left. The prominent species that appears at the bottom of the gel comigrating with the dye front is unreacted [γ-32P]ATP and, perhaps, some 32Pi.

Several observations suggested that the phosphorylated protein was Slr1856 and that the protein kinase responsible for its phosphorylation was Slr1861. First, the apparent size of the phosphoprotein matched that calculated for the Slr1856 fusion protein. Second, the phosphorylated protein migrated with a mass identical to that of a polypeptide that exhibited immunoreactivity with an antibody directed against an epitope within the fusion domain introduced by the pRSET-C expression vector (Fig. 5). Third, the reaction could be reconstituted with fractions that adhered to and were subsequently eluted from metal chelate columns designed to bind His-tagged proteins (Fig. 6). Lastly, treatment with enterokinase, which should cleave off the majority of the N-terminal fusion domain from recombinant Slr1856, resulted in the appearance of a second phosphorylated polypeptide somewhat smaller than the original (Fig. 6). Since enterokinase is highly selective for an infrequently encountered amino acid sequence, i.e., Asp4-Lys, it would be expected that few, if any, endogenous proteins in E. coli would exhibit sensitivity to this protease. Moreover, as predicted for recombinant Slr1856, the smaller phosphopeptide that appeared following protease treatment failed to react with antibodies directed against the N-terminal fusion domain (data not shown).

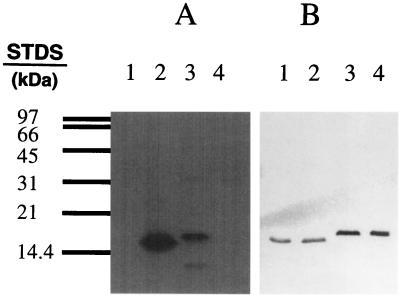

FIG. 5.

Site-directed mutagenesis suggests Slr1856 and Slr1859 are phosphorylated by Slr1861 on serine residues 54 and 57, respectively. A mutationally-altered form of Slr1856 in which Ser-54 was replaced with alanine, Slr1856 (Ser-54/Ala), and a mutationally altered form of Slr1859 in which Ser-57 was replaced by alanine (Slr1859) (Ser-57/Ala), were prepared and expressed as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Aliquots, containing 20 μg of protein each, from E. coli cells expressing either Slr1856 (Ser-54/Ala) (lane 1), Slr1856 (lane 2), Slr1859 (lane 3), or Slr1859 (Ser-57/Ala) (lane 4) were mixed with 20 μg of lysate from cells expressing Slr1861 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described in Materials and Methods. Shown is the autoradiogram of the reaction mixture following SDS-PAGE. (B) Results of a Western blot, performed as described in Materials and Methods with the anti-Xpress antibody, of a duplicate gel containing 20 μg each of protein from lysates from E. coli expressing Slr1856 (Ser-54/Ala) (lane 1), Slr1856 (lane 2), Slr1859 (lane 3), and Slr1859 (Ser-57/Ala) (lane 4). STDs, standards.

FIG. 6.

The ≈15-kDa polypeptide binds to metal chelate columns and is sensitive to cleavage by enterokinase. Lysates from E. coli expressing Slr1856 and Slr1861 were passed through separate 1-ml columns of Pharmacia Fast-Flo Chelating Sepharose that had been charged with NiSO4. The columns were prepared and run as described in Materials and Methods. Aliquots of various fractions were combined, incubated with [γ-32P]ATP, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described in Materials and Methods. By contrast to Fig. 4, however, the region of the gel containing the dye front was removed prior to autoradiography in order to prevent interference by this prominent source of 32P radioactivity in the detection of the less prominent signals from 32P-labeled phosphoproteins. Shown is an electronic autoradiogram of the reaction mixture following SDS-PAGE. Lanes 1 and 2 show the results obtained when the adhering protein fraction, 13 μg each, from E. coli expressing Slr1861 and Slr1856, respectively, were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP. Lane 3 shows the results when 13 μg (each) of these fractions were combined. Lanes 4 to 6 are identical to lanes 1 to 3 with the exception that following incubation with [γ-32P]ATP, the protein fractions were incubated for an additional 15-min period at 37°C with 1 μg of enterokinase (Invitrogen) prior to the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

Slr1859 is a relatively poor substrate for the Slr1861 protein kinase.

While sequence comparisons suggested that both Slr1856 and Slr1859 represented potential substrates for the Slr1861 protein kinase, it was consistently observed that the efficiency of phosphorylation of Slr1856 was much higher than that of Slr1859. As can be seen in Fig. 5, incubation of both phosphoproteins with Slr1861 and [γ-32P]ATP produced significantly lower levels of phosphorylation of the latter, even though Western blots revealed that the concentration of Slr1859 present in the assay mixture significantly exceeded that of Slr1856. Since it was possible that the N-terminal fusion domain of recombinantly produced Slr1859 might be interfering in some way with the phosphorylation process, we also tested recombinant Slr1859 in which this domain had been removed with enterokinase. This failed to improve the qualities of Slr1859 as an Slr1861 substrate (data not shown).

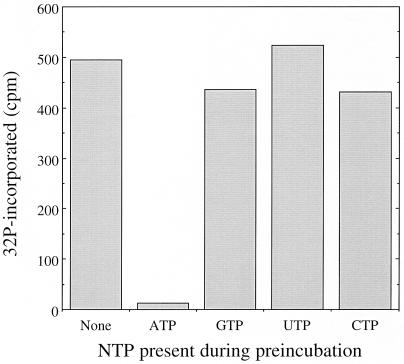

Slr1861 uses ATP as a phosphoryl donor substrate.

The nucleotide specificity of Slr1861 was explored by preincubating Slr1861 and Slr1856 in the presence of unlabeled nucleotide triphosphates. If the nucleotide present in the preincubation mixture serves as a substrate for the Slr1861 protein kinase, the phosphorylation site on Slr1856 should become occupied with unlabeled phosphoryl residues prior to the addition of [γ-32P]ATP. This will result in a decrease in subsequent radiophosphate incorporation into Slr1856. A molar excess of [γ-32P]ATP over the unlabeled nucleotides was employed in the second incubation to minimize any potential kinetic inhibitory effects upon the subsequent ATP-dependent phosphorylation of Slr1856. As can be seen in Fig. 7, only ATP was able to attenuate the incorporation of [32P]phosphate into Slr1856, indicating that Slr1861 is an ATP-specific protein kinase.

FIG. 7.

The Slr1861 protein kinase uses ATP as a phosphoryl donor. Recombinant Slr1856 and Slr1861 were partially purified by metal chelate affinity chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. Slr1861 (13.5 μg) and Slr1856 (10.5 μg) were then preincubated for 60 min under standard protein phosphorylation conditions with the exception that the indicated, nonradioactive nucleotides were substituted at a final concentration of 50 μM for [γ-32P]ATP. At the end of this time [γ-32P]ATP was added to a final concentration of 100 μM. The mixture was then incubated for a further 15 min, and the phosphoprotein content was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by electronic autoradiography. Shown are the quantities of [32P]phosphate present in the Slr1856 as a function of the nucleotide present in the preincubation.

Site-directed mutagenesis suggests Slr1856 and Slr1859 are phosphorylated by Slr1861 on serine residues 54 and 57, respectively.

Phosphoamino acid analyses indicated that Slr1856 and Slr1859 were phosphorylated on serine residues (data not shown). Comparisons with SpoIIAA, the substrate for the SpoIIAB protein kinase (25), suggested that Slr1861 might target the corresponding residues on Slr1856 and Slr1859. These residues are Ser-54 and Ser-57, respectively (Fig. 3). Therefore, mutationally altered forms of Slr1856 and Slr1859 in which the putative phosphoacceptor serine residues were replaced with nonphosphorylatable alanine residues were constructed and expressed in E. coli. The mutationally altered forms of Slr1856 and Slr1859 proved refractory to phosphorylation by Slr1861 (Fig. 5), as would be expected if the altered residues served as the phosphoacceptor sites in the native proteins.

Slr1860/IcfG exhibits protein phosphatase activity toward Slr1856, but not Slr1859, in vitro.

Expression of Slr1860/IcfG in E. coli resulted in the appearance of an appropriately sized polypeptide on Western blots probed with antibodies against the N-terminal fusion domain (data not shown). Its appearance was accompanied by an increase in the level of protein phosphatase activity, as detected with [32P]phosphocasein that had been phosphorylated on serine residues with the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, present in cell extracts. We asked whether Slr1860/IcfG was capable of dephosphorylating Slr1856 and/or Slr1859. Both proteins were phosphorylated with Slr1861 and then separated from unreacted [γ-32P]ATP by affinity chromatography on a metal chelate column. The labeled phosphoproteins were then incubated with cell extracts from mock-transformed E. coli or from E. coli expressing Slr1860/IcfG. As can be seen in Table 1, only the latter extract contained the factor required to catalyze dephosphorylation of Slr1856. Slr1859, however, proved completely refractory to dephosphorylation by Slr1860/IcfG. Removal of the fusion domain from recombinant Slr1859 prior to challenge with Slr1860/IcfG had no effect on the former’s susceptibility to dephosphorylation (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Protein phosphatase activity of Slr1860/IcfGa

| Phosphatase | Metal | Phosphate released (pmol) from:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casein | Slr1856 | Slr1859 | ||

| E. coli lysate (control) | None | 0.1 | −b | − |

| E. coli lysate | Mg2+ | 0.2 | − | − |

| E. coli lysate | Mn2+ | 0.2 | − | − |

| Slr1860/IcfG | None | 0.3 | − | − |

| Slr1860/IcfG | Mg2+ | 0.4 | 7.4 | − |

| Slr1860/IcfG | Mn2+ | 0.3 | 8.5 | − |

| PP1-cyano1 | Mn2+ | 19.0 | − | − |

| Sll1387 | Mn2+ | 20.1 | − | − |

| PP1-arch1 | Mn2+ | 26.2 | − | − |

| PP1-arch2 | Mn2+ | 31.8 | − | − |

The protein phosphatase activities of Slr1860/IcfG and various other prokaryotic protein phosphatases toward the phosphoproteins listed were assayed as described in Materials and Methods. Where indicated, the activating divalent metal ion Mn2+ was either omitted or replaced by an equal concentration of Mg2+. The concentration of protein-bound [32P]phosphate in each assay was 2 μM for casein and 0.5 μM for Slr1856 and Slr1859.

−, not detectable (<0.1 pmol).

Extraction with molybdic acid verified that the product of the reaction between Slr1860/IcfG and phosphorylated Slr1856 was inorganic phosphate (data not shown). As would be expected for an enzyme of the PPM family (3), Slr1860/IcfG protein phosphatase activity was dependent upon the presence of a divalent metal ion such as Mn2+ or Mg2+ (Table 1). Parallel incubations with four different protein phosphatases of the PPP family revealed that, despite their robust activities toward casein, none of them proved capable of hydrolyzing the phosphoserine residues on either Slr1856 or Slr1859 (Table 1). These enzymes included the protein product of ORF slr11387 from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (31, 36), PP1-cyano1 from Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7820 (30), PP1-arch1 from Sulfolobus solfataricus (19, 21), and PP1-arch2 from Methanosarcina thermophila sp. strain TM-1 (32).

DISCUSSION

As predicted from an examination of its DNA-derived amino acid sequence, the protein product of slr1861 from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 exhibited protein-serine kinase activity in vitro. Slr1861 constitutes the latest addition to a small but growing family of protein kinases whose prototype is SpoIIAB. The bacterial members of this family—SpoIIAB, RsbT, and RsbW—exhibit faint, but recognizable, homology with the histidine kinases of the two-component system (8, 10, 23, 35). The latter phosphorylate aspartic acid residues on response regulator proteins or domains through a mechanism that involves the formation of a transient phosphoenzyme intermediate on a conserved histidine residue (2). Slr1861 and its homologs lack the conserved, catalytic histidine residue of the two-component histidine kinases and target serine residues on their substrate proteins. Thus, despite sharing what was apparently a common progenitor, the SpoIIAB-like and histidine protein kinases appear to be distinct not only in their substrate specificities but in their basic catalytic mechanisms as well. The eukaryotic equivalents of the SpoIIAB-like protein kinases, the so-called mitochondrial protein kinases, also exhibit faint homology with histidine kinases, also lack the catalytic histidine residue of the latter, and also target serine residues on their substrate proteins (13).

The genes encoding RsbT and RsbW protein kinases in B. subtilis are located in operons that encode their phosphoprotein substrates, i.e., RsbS and RsbV, as well as the countervailing protein phosphatases, i.e., RsbU and RsbX, that restore these phosphoproteins to their dephosphorylated state. In the icfG gene cluster of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 a somewhat similar arrangement was observed (Fig. 1). The genes for two candidate phosphoprotein substrates, slr1856 and slr1859, were identified by homology searches. Slr1861 readily phosphorylated Slr1856 in vitro. However, this was not the case with Slr1859. Only by loading our protein phosphorylation assays with significantly greater quantities of Slr1859 than was done for Slr1856 were we able to convince ourselves that phosphate transfer to the Slr1859 was taking place. Removal of the N-terminal fusion domain failed to ameliorate Slr1859’s refractory behavior. Removal of the fusion domain from the Slr1861 protein kinase was also ineffective in enhancing the efficiency with which this enzyme phosphorylated Slr1859. Although phosphorylation of Slr1859 occurred with only a fraction of the efficiency observed with Slr1856, both phosphotransfer reactions displayed the site specificity predicted from comparisons with SpoIIAA, the substrate for SpoIIAB (25).

The refractory behavior of Slr1859 in vitro casts doubt on whether it represents a physiologically relevant substrate for the Slr1861 protein kinase. This conclusion was further reinforced by the sharp contrast in the behavior of the Slr1860/IcfG protein phosphatase toward the phosphorylated forms of Slr1856 and Slr1859. In our hands, the Slr1860/IcfG protein phosphatase selectively dephosphorylated Slr1856 but exhibited no detectable activity toward an equivalent concentration, as measured in protein-bound phosphoryl groups, of the phosphorylated form Slr1859, even after the removal of the latter’s N-terminal fusion domain with enterokinase. Protein phosphatase activity was divalent metal ion dependent, consistent with the classification of Slr1860/IcfG as a member of the PPM family (3). The specificity of Slr1860/IcfG for Slr1856 was strikingly reciprocal in nature, as the latter resisted all attempts to dephosphorylate it with several highly active and broadly specific protein phosphatases from prokaryotic organisms. Included in their number were two PPP-type protein phosphatases of cyanobacterial origin, Sll1387 from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (31, 36) and PP1-cyano1 from M. aeruginosa PCC 7820 (30). Slr1859 resisted the attentions of these protein phosphatases as well. The stringent substrate specificity of the Slr1860/IcfG protein phosphatase was reminiscent of that of its homologs from B. subtilis. For example SpoIIE would not dephosphorylate a mutationally altered form of its physiological substrate protein, SpoIIAA, following replacement of the phosphoserine residue normally present by phosphothreonine (9), while the RsbU and RsbX protein phosphatases displayed strict, and opposing, specificities for a single member of the pair of homologous phosphoproteins RsbS and RsbV (35).

The ineffectiveness of Slr1859 as a substrate for either the Slr1861 protein kinase or the Slr1860/IcfG protein phosphatase may reflect improper folding of the protein when produced by recombinant methods. However, three factors suggest that this is not the case. First, a homologous protein, Slr1856, was produced by the same means in an apparently native conformation. Second, phosphorylation of Slr1859 displayed the predicted site specificity. Third, the resistance of phosphorylated Slr1859 to protein phosphatases such as PP1-cyano1 suggests that it possessed a specific, well-defined three-dimensional structure. PP1-cyano1 displays extremely broad substrate specificity in vitro (30). Thus, while the native form of Slr1859 might prove resistant to PP1-cyano1 and the other PPP-family protein phosphatases tested, it is difficult to imagine that a misfolded or unfolded form would prove so strikingly resistant to their hydrolytic capabilities.

An alternative explanation for the behavior of Slr1859 is that it may serve as the physiological substrate for another protein kinase and/or protein phosphatase. A circumstantial argument in support of this is the modular architecture displayed by other bacterial signaling units employing SpoIIAB and its homologs. In the spo and rsb systems a one-to-one match between protein kinase and substrate protein has been faithfully observed. If one-to-one modularity represents the general pattern, then we would predict that Slr1856 is part of a functional module that includes Slr1860/IcfG and Slr1861, while the protein kinase and protein phosphatase that act on Slr1859 in vivo are encoded elsewhere in the genome of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Homology searches indicate that the genome of this cyanobacterium encodes as many as seven PPM protein phosphatases homologous to Slr1860/IcfG (31, 36) and three potential histidine kinase homologs that lack a clearly recognizable catalytic histidine (24)—possible candidates for SpoIIAB-like protein-serine kinases. One such ORF, sll1968, has been implicated through genetic studies in the regulation of photomixotrophic growth of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (15). If protein kinases and/or protein phosphatases from physically distinct operons control the phosphorylation state of Slr1859 in vivo, this opens up numerous possibilities for regulating a fundamental and pervasive cellular process, the coordination of carbon metabolism, in a multivalent fashion. In the spo and rsb systems of B. subtilis, phosphorylation-dephosphorylation modulates the abilities of key components in these signaling systems to bind to and sequester specific sigma factors until an appropriate stimulus triggers their release, initiating the transcription of sporulation-specific genes in the case of the former (10, 23) and a suite of general stress-response genes in the latter (6, 14, 16). The likely target of the phosphorylation-dephosphorylation system from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 described herein, therefore, may be a sigma factor responsible for activating expression of genes encoding enzymes required for the metabolism of inorganic carbon when CO2 is limiting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant R01 GM55067 from the National Institutes of Health (to P.J.K.) and an NSF and Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Molecular Evolution (to K.M.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler E, Donella-Deana A, Arigoni F, Pinna L A, Stragier P. Structural relationship between a bacterial developmental protein and eukaryotic PP2C protein phosphatases. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:57–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.1801552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alex L A, Simon M I. Protein histidine kinases and signal transduction in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Trends Genet. 1994;10:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barford D. Molecular mechanisms of the protein serine/threonine phosphatases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:407–412. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beuf L, Bedu S, Durand M-C, Joset F. A protein involved in co-ordinated regulation of inorganic carbon and glucose metabolism in the facultative photoautotrophic cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC6803. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:855–864. doi: 10.1007/BF00028880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bork P, Brown N P, Hegyi H, Schultz J. The protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) superfamily: detection of bacterial homologues. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1421–1425. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boylan S A, Redfield A R, Price C W. Transcription factor sigma B of Bacillus subtilis controls a large stationary-phase regulon. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3957–3963. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.3957-3963.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford M M. A rapid and simple method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dufour A, Haldenwang W G. Interactions between a Bacillus subtilis anti-sigma factor (RsbW) and its antagonist (RsbV) J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1813–1820. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1813-1820.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duncan L, Alper S, Arigoni F, Losick R, Stragier P. Activation of cell specific transcription by a serine phosphatase at the site of asymmetric division. Science. 1995;270:641–644. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan L, Losick R. SpoIIAB is an anti-sigma factor that binds to and inhibits transcription by regulatory protein sigmaF from Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;88:9934–9938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fairbanks G, Steck T L, Wallace D F H. Electrophoretic analysis of the major polypeptides of the human erythrocyte membrane. Biochemistry. 1975;10:2606–2617. doi: 10.1021/bi00789a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fort P, Piggot P J. Nucleotide sequence of sporulation locus spoIIA in Bacillus subtilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2147–2153. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-8-2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris R A, Popov K M, Zhao Y, Kedishvili N Y, Shimomura Y, Crabb D A. A new family of protein kinase—the mitochondrial protein kinases. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1995;35:147–162. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(94)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hecker M, Schumann W, Voelker U. Heat-shock and general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:417–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.396932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hihara Y, Ikeuchi M. Mutation of a novel gene required for photomixotrophic growth leads to enhanced photoautotrophic growth of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Photosynth Res. 1997;53:243–252. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalman S, Duncan M L, Thomas S M, Price C W. Similar organization of the sigB and spoIIA operons encoding sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5575–5585. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5575-5585.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamps M P, Sefton B M. Acid and base hydrolysis of phosphoproteins bound to immobilon facilitates analysis of phosphoamino acids in gel-fractionated proteins. Anal Biochem. 1989;176:22–27. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneto T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanaba A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;30:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennelly P J, Oxenrider K A, Leng J, Cantwell J S, Zhao N. Identification of a serine/threonine-specific protein phosphatase from the archaebacterium Sulfolobus solfataricus. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6505–6510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leng J, Cameron A J, Buckel S, Kennelly P J. Isolation and cloning of a protein-serine/threonine phosphatase from an archaeon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6510–6517. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6510-6517.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin J B, Doty D M. Determination of inorganic phosphate. Modification of isobutyl alcohol procedure. Anal Chem. 1949;21:965–967. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Min K-T, Hilditch C M, Diederich B, Errington J, Yudkin M D. Sigma F, the first compartment-specific transcription factor of B. subtilis, is regulated by an anti-sigma factor that is also a protein kinase. Cell. 1993;74:735–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90520-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizuno T, Kaneko T, Tabata S. Compilation of all genes encoding bacterial two-component signal transducers in the genome of the cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. DNA Res. 1996;3:407–414. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.6.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Najafi S M A, Willis A C, Yudkin M D. Site of phosphorylation of SpoIIAA, the anti-sigma factor for sporulation-specific ςF of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2912–2913. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2912-2913.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury J B, Herdman M, Stanier R Y. Generic assignments, strain histories, and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.Shi, L., and P. J. Kennelly. Unpublished data.

- 29.Shi L, Carmichael W W. pp1-cyano2, a protein serine/threonine phosphatase 1 gene from the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa UTEX 2063. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:528–531. doi: 10.1007/s002030050531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi L, Carmichael W W, Kennelly P J. Cyanobacterial PPP-family protein phosphatases possess multifunctional capabilities and are resistant to microcystin-LR. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10039–10046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi L, Potts M, Kennelly P J. The serine, threonine, and/or tyrosine-specific protein kinases and protein phosphatases of prokaryotic organisms. A family portrait. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1998;22:229–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solow B, Young J C, White R H, Kennelly P J. Gene cloning and expression and characterization of a toxin-sensitive protein phosphatase from the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila TM-1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5072–5075. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5072-5075.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wise A A, Price C W. Four additional genes in the sigB operon of Bacillus subtilis that control activity of the general stress factor ςB in response to environmental signals. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:123–133. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.123-133.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang H, Liu M Y, Romeo T. Coordinate genetic regulation of glycogen catabolism and biosynthesis in Escherichia coli via the CsrA gene product. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1012–1017. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1012-1017.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang X, Kang C M, Brody M S, Price C W. Opposing pairs of serine protein kinases and phosphatases transmit signals of environmental stress to activate a bacterial transcription factor. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2265–2275. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang C C, Gonzalez L, Phalip V. Survey, analysis, and genetic organization of genes encoding eukaryotic-like signaling proteins on a cyanobacterial genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3619–3625. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.16.3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]