Abstract

The pandemic has accelerated e-commerce adoption for both consumers and sellers. This study aims to identify factors critical to the adoption of electronic markets (EM) during the pandemic, from the perspective of small sellers in non-metro cities. The research design utilizes core dimensions of the UTAUT model and selected constructs from protection motivation theory; since business closure vulnerability also triggers electronic market adoption. A questionnaire survey method was used to collect data from 150 sellers from tier-II/III cities of India. Study results identified performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence and perceived vulnerability as significant determinants of behavioural intention towards adoption of EM. The findings also explain the moderating impact of sellers' awareness of information technology and merchants’ age on behavioural outcomes. Given the growing demands from such cities, the research offers insights for marketers to understand the bottlenecks and ways to motivate small sellers to get associated with EMs.

Keywords: Electronic marketplace, UTAUT, Protection motivation theory, Perceived vulnerability, Self-efficacy

Introduction

The pandemic accelerated the shift to digital shopping and growing use of devices such as smart phones, tablets and smart voice assistants e.g., Amazon Echo, Google Home and Samsung SmartThings (Mohammed, 2022). Post-COVID, online shopping in India increased and the e-retail market grew by 25 percent in 2020–21 (Roggeveen & Sethuraman, 2020). Data confirms that Indian retail sales surpassed pre-pandemic levels, generating 40 petabytes of data hourly.1 Electronic Markets (EM) is a digital inter-organizational network-based environment that provides technological and logistic infrastructure to buyers/sellers and facilitates electronic transactions (Holzmüller and Schlüchter, 2002). Amazon, Flipkart and Myntra are leading EMs in India. At the point of onset of COVID-19, electronic markets such as Amazon India and Flipkart, registered a 120–140 percent increase in shipments.2 Small businesses like grocery stores (Kirana stores) and small retail sellers who relied on conventional selling were forced to go online (Dannenberg et al., 2020). Amazon recorded a fifty per cent increase in the number of new sellers joining the platform3.

Government of India has been promoting e-commerce through initiatives such as Udaan, Start-Up India and Digital India, to develop the e-commerce sector (Misra et al., 2020).According to the Economic Times, the Indian e-commerce market will reach the U.S. $100 billion mark by 2025 as a result of improved Internet availability in rural areas,4 denoting an annual increase of 25–30 per cent growth. Given the size of the country and its untapped market of approximately 625–675 million people, EM is a growing area of research. Its role as a third-party mediator connecting different parts of a value chain in electronic business is increasingly important (Stockdale and Standing, 2002; Singh et al., 2021).

Following Government's advisory related to stay-at-home and social distancing 5; consumers were forced to get accustomed to online platforms and small stores were encouraged to embrace digital technologies. Organizations such as eBay and Amazon, benefited the most because they were continuing operations under their original business models. Initially, all e-commerce businesses focused on customers in Tier I (metro) cities due to consumers’ enhanced spending power and digital literacy. According to Business Line (2020),6 volume of online shoppers in Tier II & III cities and rural areas significantly increased during COVID. This created opportunities for EMs to target new markets where customers were ready to experiment but preferred to work in regional languages (Kapuria & Nalawade, 2021). To make e-commerce user-friendly and accessible to local sellers, Flipkart for example, recently introduced three new languages (BI India Tech Bureau, 2020). However, the majority of Indian retailers’ financial accounts and store operations were maintained physically (Kapuria & Nalawade, 2021). Heavy reliance on cash, physical locations, catering to smaller areas, and manually managing staff and stocks, limited the capacity of such stores for digital adoption (Seethamraju & Diatha, 2018). While the pandemic has accelerated the shift to a digital market, local sellers faced the challenge of how to adapt to EM. The difficulties were attributed to lack of awareness about the benefits of EM, technical resources and expertise, security concerns and financial constraints (Grandon & Pearson, 2004; MacGregor et al., 2010).

Empirical research is scant on EM adoption from the perspective of small sellers in a developing country (Molla & Heeks, 2007). Further, little emphasis is seen on the factors that drive small offline retailers to transition to EM from the traditional model, a gap that this study aims to fill. Previous studies have focussed on success factors for e-commerce in developed countries but very few have examined factors affecting e-commerce adoption in developing countries (Fearon et al., 2010; Hossain et al., 2021). Further, the studies overlooked local realities in tier-2 and tier-3 cities of developing nations such as norms, resources, infrastructure and culture (Hempel & Kwong, 2001; Odedra-Straub, 2003). Kshetri (2007) suggested that e-business adoption models of developed countries cannot be applied to developing economies due to contextual differences between the countries. Various factors that inhibit the adoption of EM are complex implementation techniques, limited organizational readiness, lack of investment, time and knowledge of businesses (MacGregor & Kartiwi, 2010). Before turning digital, moderator analysis needs to be carried out in a certain geographical area (Hossain et al., 2021). In this context, technical experience, which is closely related to both familiarity and competence, is important in understanding customers' perspectives, attitudes and actions in EM adoption (Nysveen & Pedersen, 2004). Similarly, age is an important moderator since older sellers’ needs, concerns, abilities and competencies with technology differ significantly from those of their younger counterparts (Chen & Persson, 2002).

In the Indian context, tier-II and tier-III cities were not technology ready and have been challenged since long by lack of network access and awareness about the benefits of creating an online presence. The current research intends to close these research gaps by examining small sellers' perceptions in relation to EM entry, and various dimensions that may have a significant impact on their decision. Thus, the following research questions were formulated:

RQ1: To investigate the impact of technological adoption factors on small sellers’ intention of EM adoption in developing markets of non-metros (Tier I/II cities) during a pandemic;

RQ2: The impact of protection motivation factors such as business obsolescence and closure of the business (PV), in the adoption of EM, during a pandemic;

RQ3: To examine the moderating impact of sellers’ age (Liébana-Cabanillas et al., 2015; Riskinanto et al., 2017) and previous experience (Castaneda et al., 2007) with EM adoption.

This study demonstrates the importance of factors, outlines a research process for elucidating such dimensions, and proposes a contextual model for small businesses entering EMs. The study contributes significantly to the existing literature on the use of EMs by small businesses because earlier established models utilized in the EM community ignored country and small-business-specific elements that may have a substantial impact on intent to use EM.

The decision to migrate to technology solutions is driven by human behaviour that can be explained by the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) model (Venkatesh et al., 2003). EM is technology-driven and justifies the use of the UTAUT model. The primary construct that captures acceptance of EM by small firms is behavioural intention (BI). The present study proposes an extension of the UTAUT model, in an environment quite different from the usual. The rationale for the proposed framework is as follows. Several small businesses were predicted to close in the initial months of the pandemic (Kapuria & Nalawade, 2021). An apt way forward to avoid such vulnerabilities was digitizing their sales and business operations. In a 2020 poll conducted during the lockdown, 40% of small grocery stores expressed their willingness to explore and experiment with online delivery and supply platforms to help sustain themselves (Kapuria & Nalawade, 2021). Thus, new variables of ‘threat’ and ‘coping’ (Knowles and Olatunji, 2021) were believed to impact the decision-making process for small sellers. Under such circumstances, EMs play an important role in helping sellers to tide over the pandemic crisis (Mansur, 2020). Taking into account the pandemic-induced threat of business closure, which necessitated going digital, the proposed model integrates additional determinants from protection motivation theory (PMT) (Rogers, 1975). Despite the relevance of PMT in the COVID-19 situation, very few studies have employed PMT to investigate user behaviour and decision-making (Kim et al., 2021; Pakpour & Griffiths, 2020; Reznik et al., 2020; Soraci et al., 2020). Majority of literature on technology adoption is skewed toward consumer experience (Min et al., 2021; Srivastava et al., 2021). Discussion is limited on EM adoption from the sellers’ perspective of threat and coping appraisals (Srivastava et al., 2021). The findings of this study will enable investors to understand the factors that enable uptake of EM by non-metro sellers, with direct implications for e-commerce theory, research and practice.

The present section introduces the topic of research. Section 2 gives a detailed literature review followed by the theoretical framework in Sect. 3. Section 4 explains the research methodology for conducting the analysis. In the first stage, PLS-SEM was employed to understand the significant influence of antecedents on EM acceptance; in the second stage, an important performance framework was employed to identify the importance of antecedents. Section 5 discusses the results, followed by discussions in Sect. 6 that help in identifying areas of importance and improvement, the conclusions, and how this research has moved forward the body of EM community knowledge.

Review of literature

Electronic markets and sellers

There is a substantial overview of literature on the interest of sellers in electronic markets (Bandara et al., 2020). Many studies revealed the potential of electronic markets in business operation and customer interaction (Kumar & Ayedee, 2021; Raza & Khan, 2021). For example, buyers can use electronic markets to find suppliers who meet their particular needs at a reduced cost. This increases consumers’ accessibility and seller visibility in electronic markets (Lee, 1998; Lynn et al., 2022). At the same time, from the sellers’ viewpoint, Duan et al., (2018) discussed the supply chain efficiencies of sellers which have increased while using electronic markets, since it reduces multiple intermediaries in the process. Products are sold to the customers through virtual mode based on product information rather than physical appearance (Wei et al., 2018). Holzmüller and Schlüchter (2002) predicted the use of EM and emphasized different economic benefits provided to sellers by selling their products thus. Wang et al., (2006) indicate that system capabilities, special offers and familiarity with business processes are a few facilitating factors provided by EM to sellers. In addition, during the COVID epidemic, some research revealed high adoption of electronic markets by sellers due to enhanced convenience in online procedures, consumers’ preferences and reduced transaction risk (Akpan et al., 2020; Lynn et al., 2022). As per Akpan et al., (2020), it was during the pandemic that small sellers became more conscious of technology-based trades, and their role in increasing operational efficiency and competitive advantage. However, the usage of electronic markets by sellers has been debated recently. Despite the importance of electronic markets, studies revealed a lack of growth and adoption among sellers (Bandara et al., 2020; Indriastuti & Fuad, 2020; Kumar & Ayedee, 2021).

Sellers in both Business to Consumer (B2C) and Consumer to Consumer (C2C) markets face severe competition in electronic markets (Indriastuti & Fuad, 2020; Taeuscher, 2019). Consumers can approach multiple sellers for their products and services, and choose one based on convenience and price. This forces sellers to shift to such platforms and promote their products for better perceptibility (Akpan et al., 2020). According to Hwang (2009), participating in a socially constructed electronic market system can increase organizational legitimacy but reduces sellers' bargaining power. Following social norms, sellers who use electronic markets can face significant demand variability and unpredictable competitor actions. Simultaneously, many vendors lack trust due to little or no connection with customers. This may lead to e-commerce fraud related to late payments and unnecessary consumer disputes (Bandara et al., 2020). Lack of knowledge of technology resources and IT assistance also deter merchants from using electronic markets (Costa & Castro, 2021; Duan et al., 2018). Inadequate knowledge of vendors about e-commerce platforms influences their use and exploitation of these markets (Lynn et al., 2022). All these concerns are raised and discussed in past literature exploring low growth and adoption of electronic markets by sellers.

The recent pandemic outbreak imposes great vulnerability on businesses (Raza & Khan, 2021). Previous research revealed a substantial pandemic impact on local businesses and transactions due to the constraints imposed and low consumer demands in urban marketplaces (Hoang et al., 2021; Lynn et al., 2022). According to Kumar and Ayedee (2021), merchants must optimize their existing business processes using ICT and e-commerce to stay competitive. These improvements are required to handle the management of both raw–materials and supply-chain, which is impacted by COVID 19. Various studies have acknowledged these platforms' high convenience and utility in sales and logistics operations (Kizgin et al., 2018). However, little exploration is done in the COVID 19 context. Sellers’ business and demand related vulnerabilities during a pandemic can be reduced since, with the help of electronic markets, they can approach large groups of customers (Bandara et al., 2020).

Self-efficacy is defined as, 'individual's belief in one's ability to accomplish specific activities’ (Srivastava et al., 2021; Wan & Wang, 2018). There is evidence showing that users’ self-efficacy is associated with behavioural intention, and plays a significant role in the adoption of electronic markets (Kim et al., 2009). As technology continues to evolve, ability of sellers to use electronic markets for selling, delivering and handling operations is linked to the performance and adoption of such market places (Kim et al., 2009; Wan & Wang, 2018). Customers' needs change and expand as online marketplaces deliver a greater variety of products and services (Edwards et al., 2022). How sellers handle online platforms and use innovative methods to boost their visibility and customer acceptability determines their survival in the electronic markets. Drawing upon social cognitive theory, Wan and Wang (2018) identified seller self-efficacy as a major differentiating and growth factor in electronic markets. As suggested by Dholakia and Kshetri (2004), sellers' self-efficacy in handling online transactions, technological challenges and consumer enquiries influence their adoption of electronic markets. They are confident in their ability to adapt to the evolving online shopping behaviours and the dynamic business environment. Sellers will trust and use electronic markets more if they can address these problems efficiently (Kim et al., 2009). Literature has revealed the importance of self-efficacy in the online context, particularly for customers (Reznik et al., 2020; Soraci et al., 2020). Limited studies exist in the pandemic scenario but with inadequate understanding of seller self-efficacy (Edwards et al., 2022).

Users' demographics and socio-economic characteristics have been discussed along with their online behaviour, particularly in electronic markets (Passyn et al., 2011; Wagner et al., 2017). Age, gender and experience were found to have little effect on behavioural intention in most studies (Loebbecke et al., 2010). However, we discovered diverse findings among sellers. According to Misra et al. (2020), home décor retailers are more concerned about facilitating conditions than apparel retailers. Lubis (2018) confirmed the importance of demographics in online behaviour. However, there are some cases where demographics have no influence on user behaviour (Wang and Cheng 2004; Loebbecke et al., 2010). This reveals the gap in demographic understanding of EM adoption in literature. Table 1 summarises recent studies in the context.

Table 1.

Summary of recent studies of EM adoption

| Research profile | Purpose of the study | Findings of the study | Theory(s) adopted |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Authors: Duan et al., (2018) Method: Empirical (DEA) Sample: 43 electronic markets |

The purpose of the study is to identify the efficiency-oriented important factors in the development of e-market in electronic trade | The efficiency of electronic markets depends on their international coverage, fixed price mechanism, social media engagement, years in operations, product specialization and ownership | NA |

|

Authors: Wan and Wang (2018) Method: Empirical Sample: 267 sellers |

The study talks about entrepreneurial self-efficacy and remote work-efficacy, and their impact on operational creativity and performance in online marketplaces |

Operational creativity improves sellers’ performance in online marketplaces. Customer engagement and attractive page layout enhance the operational creativity of sellers |

Social cognitive theory |

|

Authors: Edwards et al., (2022) Method: SEM analysis Sample: 252 B2B salespeople |

The research explores the relationship between B2B sales performance, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial sales behaviours | Self-efficacy enhances creative selling and sales innovation. To improve effectiveness, management should promote and recognize new selling methods | NA |

|

Authors: Idris et al., (2017) Method: Descriptive Sample: NA |

Critical analysis of existing innovation adoption theories for explaining SMEs’ e-commerce adoption | There is a need for an integration framework. The synergy between the perceived e-readiness model and the technology organization environment framework is considered |

Perceived E-readiness Model Technology organization environment framework |

|

Authors: Ikumoro and Jawad (2019) Method: Descriptive Sample: NA |

The study examined extrapolative elements to explain Malaysian SMEs' inclination to use intelligent conversational agents for e-commerce | The study identified 11 critical factors including usefulness, relative advantages, security and others that influence AI based technology adoption in e-commerce among SMEs |

UTAUT Technology-organization -environment framework (TOE) |

|

Authors: Wang et al., (2006) Method: Case study method Sample: NA |

This paper examines EM adoption from both buyers and sellers’ perspectives | The results of the case studies show that performance expectancy is the most crucial factor for adoption | NA |

|

Authors: Naughton et al., (2020) Method: Case study method Sample: NA |

The purpose is to analyze how SMEs create and apply supply chain agility (SCA) in the context of rising environmental uncertainty |

Organizational attitudes shape how SMEs perceive environmental unpredictability, address organizational vulnerabilities and establish SCA | NA |

|

Authors: Indriastuti and Fuad (2020) Method: Descriptive Sample: NA |

The purpose the study is to explore the sustainable framework for SMEs during pandemic times | To be sustainable, SMEs must adopt a new business mindset based on technology. The study confirmed that SMEs lack knowledge on digital skills | NA |

|

Authors: Ferreira et al., (2021) Method: Semi-structured interviews method Sample: NA |

This study looks into the supply chain during the COVID-19 pandemic for SME food firms, identifying relevant areas for improvement | There are a few constraints related to lack of supply chain process, lack of alternative suppliers, low budget and others that influence SME performance | Complex adaptive system theory |

Theoretical background

Literature review on electronic markets and related factors revealed a gap in research linked to seller-based studies, particularly in a pandemic context. This study used a combination of two grounded theories developed over the last decade. The first theory examines determinants that influence the adoption of IT and related technologies. The second theory investigates the protection motivation factors influencing the adoption of IT to cope with adverse outcomes. Prior researches have used different approaches to study the behaviour of adoption of technology such as the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989), Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1988) and Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1985). The present study follows UTAUT as a theoretical base. UTAUT explains about seventy per cent of the variance in behavioural intention to use technology and about fifty per cent of the variance in technology use (Venkatesh et al., 2012).

Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology

The UTAUT Model (Venkatesh et al., 2003) has been widely used to assess users' acceptability of information technology. UTAUT includes two technology attributes: performance expectancy (PE) and effort expectancy (EE), and two contextual drivers: social influence (SI) and facilitating conditions (FC) (Alshehri, 2012). These factors have been extensively used in previous studies to assess individuals' perceptions of new technology and the context of technology adoption (Venkatesh et al., 2012). The UTAUT factors indicate the influence of technical capabilities, facilitating environment and social norms, on users' beliefs regarding certain digital or technology exposure (Dwivedi et al., 2019). Additionally, a substantial amount of research suggests the model's high explanatory power for predicting users' behaviour intention towards new technologies (Dwivedi et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2020). In the electronic market context, past UTAUT-based studies discussed utilitarian benefits associated with online convenience and transaction utility (Rodrigues et al., 2016). Wang et al., (2006) demonstrated the relevance of the UTAUT framework for EM adoption, stating that the most significant aspect for participating users is performance expectancy, followed by ease of use. In particular, sellers perceive these benefits based on e-commerce skills (Uzoka, 2008). Variables' performance expectancy examines the effectiveness of online markets to improve business performance to sellers (Idris et al., 2017). At the same time, effort expectancy develops sellers' understanding of how electronic markets save time and effort which will impact future adoption of these marketplaces (Idris et al., 2017). Thoung (2002) deliberated performance expectancy, facilitating conditions as significant UTAUT factors to determine their effect on the adoption of EM by sellers. Concerning contextual drivers, facilitating conditions were explained on technical facilities, infrastructure and system support provided to sellers for e-commerce convenience (Pakpour & Griffiths, 2020; Reznik et al., 2020). Lack of these supports and services in the market prevents sellers from offering tailored services to clients based on their needs and preferences (Soraci et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2006). Next, social norms described sellers’ trust in social norms and social pressure in adopting electronic markets for achieving competitive advantage and meeting consumer demand (Srivastava et al., 2021). During the pandemic, firms experienced low demand and a tough business environment (Kumar & Ayedee, 2021). Various articles demonstrate how merchants are utilizing ICT and e-commerce to streamline current business operations during the crisis time (Kim et al., 2021; Kumar & Ayedee, 2021; Rodrigues et al., 2016). Social influence has also forced online sellers to remain competitive (Ikumoro & Jawad, 2019). Enhanced service delivery and logistics management may be achievable through electronic markets during COVID 19 (Kim et al., 2021; Min et al., 2021). Such features are shared on various social platforms that encourage new sellers and influence their intention (Bandara et al., 2020). The current research proposes using UTAUT variables to determine sellers' intention because they measure both technological and contextual aspects of a product or service.

Protection motivation theory (PMT)

The protection motivation theory was developed to measure users' risk management behaviour (Rather, 2021). Threat evaluations assess the magnitude and probability of risk, while coping mechanisms assess the protective efficacy of the system and users (Herath & Rao, 2009; Youn et al., 2021; Rather, 2021). PMT has been used in online marketplaces for assessing privacy and system vulnerabilities (Chen et al., 2017; Mousavi et al., 2020; Vance et al., 2012). These studies examined how users respond to such fear appeals (Johnston & Warkentin, 2010) and how these concerns might be effectively managed with a recommended course of action. According to Teofilus et al., (2020), usage of online marketplaces has a variety of technical and economic advantages. These places may help users stay competitive and meet current demand. Fear or tension drives individual protection behaviour. This desired behaviour will reduce fear while engaging in adaptive responses. (Boss et al., 2015). Users revealed high protective motives when faced with uncertainties and challenges that affect their behaviours (Xiao et al., 2014). For example, Naughton et al., (2020) suggested that businesses that face supply chain disruptions seek to protect themselves by partnering with suppliers, enforcing safety frameworks and so on. Yoo et al., (2021) highlighted users' protective motives towards malicious technologies by generating emotion-focused motives and avoiding malicious content. Similarly, various studies revealed the positive influence of PMT variables on online platform adoption (Boss et al., 2015; Rahi et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2019).

During the COVID crisis, sellers were highly vulnerable, as they faced financial and business issues (Edwards et al., 2022). Sellers' vulnerability is explained as their fear of undesirable outcomes such as business closure and weak demand (Akpan et al., 2020; Lynn et al., 2022; Naughton et al., 2020). The pandemic has affected business processes and increased seller concerns. At the same time, the literature focuses on sellers' protection strategies and coping abilities in COVID 19 crises (Edwards et al., 2022; Ferreira et al., 2021). The sudden outbreak forced sellers to seek alternatives to prevent store closures. It necessitated the use of new digital platforms and non-contact modes to safeguard operations (Akpan et al., 2020). Small retailers have shown interest to associate with electronic markets than establishing their own websites. Similarly, non-metros buyers and sellers adopted a new mindset by opting for digital sales (Aqeel et al., 2020). These actions exhibit the protective motives of sellers or firms during the crisis that influence their adoption of e-commerce platforms (Johnston & Warkentin, 2010). Merchants are reconsidering traditional procedures by adopting digital platforms and e-commerce technologies to reduce business risk and meet consumers’ demands (Kumar & Ayedee, 2021). Hence, the study suggests that PMT may be an appropriate theory to assess pandemic fear appeals and the protective motives of sellers that influence EM adoption.

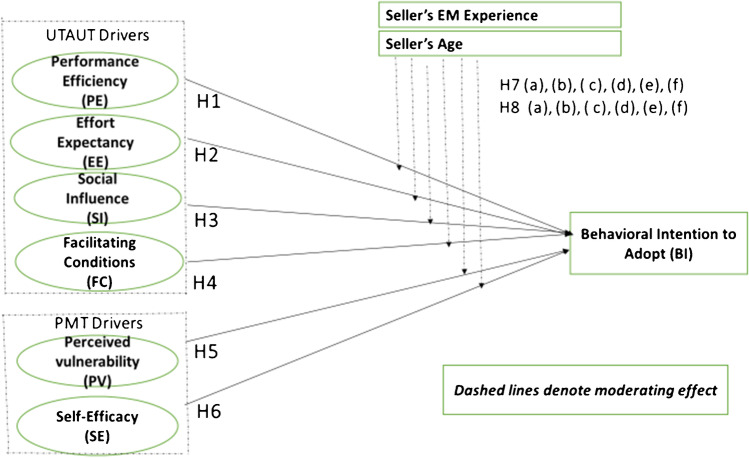

Integrated model

The study combines PMT and UTAUT to explore sellers' risk perceptions of COVID-19 and their EM adoption behaviour due to the following reasons: First, the adoption of electronic markets has been widely discussed in consumer behaviour and information system literature (Min et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2018). Past studies talked about consumer perception and predictors of EM adoption (Srivastava et al., 2021). This study found limited research on sellers’ behaviour to adopt electronic markets (Akpan et al., 2020). In recent years, a few researchers have discussed firms’ revival strategies related to supply chain, digital or technology interventions, and green processes, during COVID 19, but work is still underway (Akpan et al., 2020; Lynn et al., 2022; Naughton et al., 2020). There are very few studies on sellers in the COVID 19 context. Second, understanding EM's convenience and utility to sellers in a crisis are crucial. Also, the impact of these marketplaces on sellers' e-commerce needs must be addressed. UTAUT framework is adopted for this research because it evaluates both technological and contextual aspects of a product or service. The impact of UTAUT factors on electronic market adoption has not been studied in the COVID 19 scenario (Edwards et al., 2022; Soraci et al., 2020). The present study fills this gap in the existing literature.

Third, sellers are looking into online platforms or e-commerce sites to sustain their operations and protect themselves from the COVID 19 crisis (Naughton et al., 2020). Understanding sellers' fear appeals and protective motives are critical. It is notable that the UTAUT framework cannot contain behavioural or motivational variables linked to adoption intention (Singh et al., 2021). To fill this gap, this study integrates UTAUT with protection motivation theory as it reveals how people are motivated to react to negative consequences via assessment processes. Recently, Taheri-Kharameh et al., (2020) confirmed protection motivation, coping assessments and rational fear as protective behaviour determinants. PMT variables may explain sellers' business threats and coping techniques that influence electronic market adoption (Chen et al., 2017; Mousavi et al., 2020). The study measures sellers' probability and amount of risk in a pandemic by the variable perceived vulnerability. Also, sellers' efficacy explains their coping abilities in unfavourable COVID-19 situations (Yoon et al., 2002; Teofilus et al., 2020). We eliminate response efficacy which assesses system efficacy in difficult situations. The reason is that system efficacy has already been examined in UTUAT under facilitating conditions (Dwivedi et al., 2019). Thus, the PMT constructs of perceived vulnerability and self-efficacy were found to be suitable to understand sellers' adoption of electronic markets in the current pandemic scenario. Fourth, the moderating effect of sellers' age and experience is included to refine existing research in the domain.

Based on thearguments presented above, the following conceptual model is proposed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The proposed model

Hypotheses development

Performance expectancy (PE)

According to Venkatesh et al., (2003), PE is an individual’s perception that the usage of innovative technology will improve performance. In the context of EMs, PE is the extent to which the availability of the EMs will improve sellers’ performance (Davis, 1989). Factors related to time-saving and efficiency, as part of Ems, are included in PE (Srihivasan et al., 2002). Studies show a significant link between PE and e-commerce adoption (Venkatesh et al., 2003). The impact of PE on EM adoption has also been scrutinized (Wang et al., 2006; Büyüközkan, 2004; Subawa et al., 2019; Wijaya & Handriyantini, 2020). According to Wang et al., (2008), increased PE is associated with a stronger behavioural intention to utilize EM. Thus, the study proposes:

H1: Performance expectancy (PE) positively influences the behavioural intention (BI) of electronic market sellers.

Effort expectancy (EE)

EE is a construct that refers to doing business in EM as a simple process (Alhilali, 2013; Guo et al., 2015). Wang et al., (2008) state that EE characterizes the ‘technological ease’ associated with the system and must be judged based on efforts required by small sellers to establish an online presence. In the COVID scenario, sellers are expected to be equipped with the know-how to operate mobile, Internet, etc. Small sellers must be conversant with different payment methods such as Google Pay and Paytm. Hence, based on the complexity of new technology, sellers may decide if the transition to EM would be feasible (Abd Latif et al., 2011). Venkatesh et al., (2003) and Kabra et al., (2017) established that EE is the most influential variable in the model; this was validated using different perspectives and technological environments. EE is important as this will determine how users would utilize technology in the future (Lee, 2009; Park & Ohm, 2014). Conversely, Wang et al., (2006) state that EE did not significantly impact EM adoption decisions. Hence, this study proposes:

H2: Effort expectancy positively influences the behavioural intention of sellers of electronic market.

Facilitating condition (FC)

FC is defined as the seller's perception of the availability of resources and assistance in utilizing technology (Davis, 1989; Yu, 2012). FC is critical in that it influences the adoption of e-commerce (MacGregor & Kartiwi, 2010; Mzee et al., 2015; Subawa et al., 2019). Factors that support EM are: familiarity with online business processes and well-developed technical infrastructure, which are included in this construct (Prihastomo et al., 2018). Thus, in EM adoption, FC is an important consideration that encourages sellers to utilize EM services for technological requirements (Rogers, 2010). Therefore, we propose:

H3: Facilitating condition positively influences the behavioural intention of sellers of electronic market.

Social influence (SI)

Environmental influences such as thoughts of relatives, friends and colleagues, on individual behaviour are known as social influence (Venkatesh et al., 2003; San Martín and Herrero, 2012). The influence of SI on user behaviour has been widely established, specifically in diverse areas of technology adoption (Venkatesh et al., 2003). SI is important as this encourages sellers to register with EMs (Fearon et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2016). Thus, influence and encouragement provided by friends, customers and partners play an important role in increasing sellers' awareness of and willingness to accept technology (Zhou, 2011, Wong and Dioko, 2013; Alshehri et al., 2019). Alrawashdeh et al., (2012) and Yu (2012) found a significant relationship between the two constructs but Cheng et al., (2011), Deng et al., (2011) and Wong and Dioko (2013) found an insignificant relationship. According to Akbar and Parvez (2009) and Chua et al., (2018), social influence has a substantial effect that determines BI. Hence, it is proposed:

H4: Social influence positively influences the behavioural intention of sellers of electronic market.

Perceived vulnerability (PV)

When confronted with a risk, protection motivation triggers a shift in attitude (Milne et al., 2000). Threat and the associated fear can inspire adaptive behaviour when a person tries to cope with the threat to "avert the threatened danger” (Knowles and Olatunji, 2021). Mobility restrictions during the COVID-19 crisis have impacted small firms adversely that relied on regular cash transactions and loyal consumers. Furthermore, small firms are vulnerable due to the limited financial and administrative support given that the COVID-19 pandemic could last longer than anticipated (Bartik et al., 2020). The fear or the psychological aspect of the pandemic and the move to EM adoption have been assessed by researchers (Pakpour and Griffiths, 2020; Ahorsu et al., 2020; Harper and Rhodes, 2020) by measuring users’ vulnerability to the situation and how it affects their attitude.

Thus, our study hypothesizes that factors affecting motivation protection behaviour would be associated with PV. The higher the business perceives the risk and fear of closure, the higher is the probability of timely entering Ems, as a coping strategy to mitigate the threat. Thus, the perception of threat would lead to behavioural change to switch to EM.

H4: Perceived vulnerability positively influences the behavioural intention of sellers of electronic market.

Self-efficacy (SE)

Self-efficacy (SE) describes a person's belief in his or her capability to accomplish a certain task (Bandura, 2000). People with high self-efficacy focus attention and motivation on tasks that help them achieve their goals. Prior studies by Rahi et al., (2021); Bilgrami et al., (2020) assessed the self-efficacy of patients and reported a favourable intention to use telemedicine and other technologically driven interventions, which help them to manage sickness more effectively. Several other studies (Bilgrami et al., 2020; Chow et al., 2013; Deng & Liu, 2017; Guo et al., 2015; Lankton & Wilson, 2007; Yeşilyurt et al., 2016) also report that computer self-efficacy has a beneficial effect on patient intention to use telemedicine health services. In the current context, SE is the seller's judgment of their capacity to sell on EM which is a coping response (Milne et al., 200). More specifically, while assessing sellers' decision to sell on EM, the SE of sellers has been shown to significantly influence their intention to assume protective behaviour while adopting EM (Hsu & Chiu, 2004). Maddux and Rogers (1983) explain the direct influence of SE on variables of PMT theory. When individuals perceive that their efficacy in coping with unwanted outcomes is high, they evaluate actions favourably. SE in embracing new EMs during the ongoing pandemic plays an important role in predicting prevention behaviours, and influences behavioural intention (BI) to EM adoption.

H5: Self-efficacy positively influences the behavioural intention of sellers of electronic market.

Behavioural intention (BI)

An individual's desire to engage in a particular behaviour is referred to as BI (Krueger & Brazel, 1994).). BI drives behaviour that determines users' acceptance and adoption of technology (Krueger & Brazel, 1994). BI is an important variable that has been investigated, particularly in technology adoption models (Abubakar & Ahmad, 2013).

Moderating effect of sellers’ EM experience

Previous research has looked into the importance of experience on attitudes and behaviour intentions (Castaneda et al., 2007). A study by Venkatesh et al. (2008) reported that a longer user experience with technology allows users to take better advantage of technical resources. Other studies by Goldsmith, (2002); Yoon et al. (2002) found that users with more technical experience and regular access to the Internet are generally satisfied with their e-purchasing behaviour.

Despite the fact that sellers’ experience of registering and operating on EM is crucial in vendor market partnerships, this aspect has received little attention from academia and industry (Kumar et al., 2019). EMs must ensure that vendors are comfortable managing orders on their platforms. Sellers could apply their past expertise and experience with electronic payments, social media tools and mobile applications to use of EM. For example, more experienced e-commerce or other information technology users may find it easier to access and/or continue to use EM than less experienced users. Whether one wants to sell little or a lot, sellers can utilize EM tools to manage operations and sell successfully online. However, EMs entail operational challenges related to products, customers and software (Carter Thom James, 2020). Any unresolved issue that is not fixed instantly has the potential to affect sales in EM and the seller’s reputation. Lack of skills that limits adoption of new technologies is also validated by Choudhury et al. (1998), Enterworks (2000) and Mello (2000), who reported that the level of sellers' knowledge to handle an electronic product catalogue essentially limits their intent to enter EM. On the other hand, for experienced users, selling on EMs can be an easy way to reach potential buyers (Grewal, et al., 2001; Hossain et al., 2021). Further, sellers’ experience positively influences the inclination to sell online and to cope with the challenging environment (Wang & Cheng 2004). Thus, we hypothesize that seller's EM experience moderates the effects of PE, EE, FC, SI, threat and coping appraisals to adoption of new digital platforms.

H7: (a, b, c, d, e, f): Difference in EM experience of sellers moderates the relationship between PE, EE, FC, SI, threat and coping appraisals and the Behavioural Intention of sellers of Electronic Market.

Moderating effect of sellers’ age: younger and older sellers

Older generation may find technology or new devices difficult to utilize, whereas younger generations may embrace them with ease (Riskinanto et al., 2017). A study by Liébana-Cabanillas et al., (2015) sought to determine if age had a moderating influence on the adoption of new mobile payment methods. In another study on internet banking, by Yousafzai and Yani-de-Soriano (2012), innovation resistance among mature consumers was found higher as compared to younger consumers. Older adults are slower to adopt new technologies than younger adults (Czaja et al., 2006), but they would do so if the technologies appear to be useful, especially in maintaining their quality of life (Heinz et al., 2013). As a result, it is critical to understand how older people adopt technology. Hill et al. (2015) used quantitative survey methodologies to investigate older persons' experiences with technology uptake and use.

Astuti et al. (2014) found that in a developing country, age is a critical variable in determining sellers’ intention to adopt EM. Previous research reported a negative correlation between users’ age and IT adoption (Joines et al., 2003). The main cause for older users' lack of interest in technology adoption is lack of computer literacy (Wagner et al., 2017). Older adults may intend to continue the conventional manner of selling in an offline store due to perceived hurdles (i.e., privacy, irritation) and technical issues (Passyn et al., 2011). Agwu and Murray (2014) claim that the younger generation has fewer inhibitions when it comes to accepting EM, especially during COVID-19. As a result, younger consumers may consider switching to EM. Thus, it is proposed that:

H8: (a, b, c, d, e, f): Sellers' age moderates the relationship between PE, EE, SI, FC, threat and coping appraisals and Behavioural Intention of sellers in Electronic Market.

Research methodology

The objective of the study is to measure the behavioural intention of small-sellers towards the adoption of EM. The present study considered small sellers from non-metro cities (Tier II/ III) registered with three major electronic markets namely, Amazon, Flipkart and Myntra. Indian cities are divided into tiers I, II and III on the basis of a grading structure devised by the Government of India (www.mapsofindia.com). As per IBEF (2021), tier II and III cities will drive the next phase of growth for the Indian retail sector due to an increase in disposable income and access to mobile internet. Due to lack of data on existing EM sellers (sampling frame) the study used a non-probability-based sampling method and selected the respondents based on the researcher's subjective evaluation (Saunders & Townsend, 2018) based on the premise that the respondents were existing sellers registered with EM. A pilot/pre-test was conducted with 30 respondents to ensure the appropriateness of the scales and improvement, if any, required in the questionnaire. The questionnaire was independently validated by three academics and four experts from Amazon and Flipkart.

Based on the PLS-SEM model, the minimum sample size was estimated between 100–150 (Rezaei, 2015). Moreover, since respondents included sellers only (not consumers), the sample size of 150 is acceptable (Rigdon, 2016). The research objective was explained to all the participants, and participation was optional. First, the researcher personally administered the questionnaire to the first 30 respondents for the pilot study; second, available email and contact details of all registered sellers on the three selected EMs were collected through personal and professional contacts and an online link was shared with them.

The questionnaire was divided into two sections. Section one had seven variables: gender, age, type of business, number of years registered with Amazon, and frequency of order per week (shown in Table 2). Data collection was completed in ten days to ensure consistency in the sampling time frame. Of the 186 responses collected, 36 were incomplete and not used for analysis, leaving a sample size of 150. Response rate of the questionnaire was approximately 81 per cent. Research constructs adopted in earlier studies were included in the second section of the questionnaire (Appendix A: Measurement scale).

Table 2.

Demographic profile of respondents

| Demographics | Frequencies | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 91 | 59.16 |

| Female | 59 | 40.84 | |

| Age (years) | 18–30 | 40 | 26.67 |

| 31–40 | 48 | 32.00 | |

| 41–50 | 35 | 23.33 | |

| Above 50 | 27 | 18.00 | |

| No of years registered with EM | Less than 6 months | 60 | 40 |

| 6 months to less than a year | 48 | 32 | |

| 1–3 years | 25 | 16.67 | |

| More than 3 years | 17 | 11.33 | |

| Frequency of receiving order | None | 20 | 13.33 |

| An order in several weeks | 45 | 30 | |

| An order per week | 38 | 25.33 | |

| An order in a day | 29 | 19.33 | |

| Multiple orders in a day | 18 | 12 | |

| Type of business | General Store | 41 | 27.33 |

| Footwear and Apparel | 44 | 29.33 | |

| Gift shops | 37 | 24.67 | |

| Stationery and office products | 28 | 18.67 | |

Results

Common method bias

Common method bias is a systematic bias in the measures due to the measuring method (Doty & Glick, 1998). This occurs when all variables are measured with the same method or from the same source (Richardson et al., 2009). The existence of common method bias might potentially skew the expected relationships between various constructs in the model (Jakobsen and Jensen, 2015). In an electronic commerce empirical study, when a single questionnaire survey measures all constructs and at the same time, there is probability that the tested relationships between constructs have an effect of common method variance which is minimized by maintaining respondent’s anonymity (Tehseen et al., 2017).

Scale statements for the construct were adapted to the local context. Respondents were assured that the data was collected for academic purposes. Two tests were used namely, Harman's common factor test (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986) and full collinearity assessment approach (Kock, 2015). With Harman's common factor test, a minimal increase in the R-square value was observed. Using the full collinearity assessment approach, the VIF value for the inner model was found below the threshold value of 5 (Hair et al., 2019), indicating that the data collected had less probability of common method bias.

Demographic details

The sample consisted of 60% males and 40% females (Table 2). A larger percentage of males is reported because owners/managers of small businesses are usually male members. However, 40% of the sample being female shows the growing interest of Indian women in business. The majority of sellers have been operating on an EM that was set up for less than three years. Classification was done by type of business: General store (wide variety of goods including groceries), Footwear, Gift shops, and Stationery & Office products.

Measurement model (Construct validity)

To evaluate the measurement model (Construct validity) and item loadings, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), researchers assessed Composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach alpha (CA) values. Six constructs (Performance expectancy, effort expectancy, facilitating condition, social influence, perceived vulnerability and self-efficacy) were assessed to establish reliability and validity (Table 3). Reliability and validity tests ensure that all the statements used to measure the constructs provide good formative questions (Hair et al., 2019). This also addresses the suitability to make accurate predictions relevant to the study. Consistency was determined using Cronbach alpha values. As per Nunnally (1978), an alpha value of 0.700 and above indicates that statements in the scale meet the internal consistency criterion. Thus, all variables satisfy the requirements for internal consistency. Composite reliability (CR) was investigated, wherein the statements were weighted based on the construct statements' loadings. The CR of all the constructs was within the range of 0.70 to 0.90 (Hair et al., 2019). The average variance extracted for all items was greater than 0.50 (Hair et al., 2019). Table 3 presents the results for statement-wise loading, AVE and CR.

Table 3.

Construct validity

| Research construct | Item | Item loading | Average variance extracted (AVE) | Composite rReliability (CR) | Cronbach aAlpha (CA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effort expectancy | EE1 | 0.852 | 0.645 | 0.843 | 0.716 |

| EE2 | 0.887 | ||||

| EE3 | 0.700 | ||||

| Facilitating conditions | FC1 | 0.844 | 0.631 | 0.835 | 0.717 |

| FC2 | 0.863 | ||||

| FC3 | 0.700 | ||||

| Perceived vulnerability | PV1 | 0.89 | 0.631 | 0.863 | 0.683 |

| PV2 | 0.851 | ||||

| Self-efficacy | SE1 | 0.909 | 0.740 | 0.850 | 0.658 |

| SE2 | 0.809 | ||||

| Performance expectancy | PE1 | 0.741 | 0.501 | 0.797 | 0.660 |

| PE2 | 0.701 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.715 | ||||

| PE4 | 0.702 | ||||

| Behavioural intention | BI1 | 0.779 | 0.628 | 0.835 | 0.703 |

| BI2 | 0.835 | ||||

| BI3 | 0.763 | ||||

| Social influence | SI1 | 0.875 | 0.677 | 0.863 | 0.766 |

| SI2 | 0.793 | ||||

| SI3 | 0.799 |

In addition, the Fornell-Larcker criterion (1981) and Cross loading (Discriminant validity) were used to assess discriminant validity (DV). Diagonals represent the square root of AVE, and off-diagonals reflect the correlation, as seen in Table 4. The values displayed for the Fornell-Larcker criterion show that diagonal values are greater than off-diagonals, implying the presence of discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity

| EE | FC | PB | PC | PE | Sat | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | 0.803 | ||||||

| FC | 0.282 | 0.794 | |||||

| PB | 0.686 | 0.218 | 0.795 | ||||

| PC | 0.227 | 0.105 | 0.442 | 0.861 | |||

| PE | 0.595 | 0.238 | 0.528 | 0.167 | 0.707 | ||

| Sat | 0.679 | 0.292 | 0.749 | 0.292 | 0.677 | 0.792 | |

| SI | 0.191 | 0.682 | 0.075 | 0.235 | 0.178 | 0.281 | 0.822 |

Further, bold values represent loadings above the suggested threshold of 0.5 for each component (Table 5). Discriminant validity among constructs is inferred when an item's loadings on constructs are higher than all of its cross-loadings with other constructs. Highlighted values are loadings for each statement, above the prescribed value of 0.5; item loadings for its construct are higher than all cross-loadings with other constructs.

Table 5.

Cross loadings

| EE | FC | PV | SE | PE | BI | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE1 | 0.852 | 0.124 | 0.259 | 0.121 | 0.397 | 0.388 | -0.060 |

| EE2 | 0.887 | 0.178 | 0.256 | 0.21 | 0.377 | 0.453 | -0.024 |

| EE3 | 0.700 | 0.200 | 0.224 | 0.042 | 0.203 | 0.319 | 0.232 |

| FC1 | 0.150 | 0.844 | 0.148 | 0.065 | 0.104 | 0.197 | 0.441 |

| FC2 | 0.211 | 0.863 | 0.179 | 0.104 | 0.177 | 0.200 | 0.439 |

| FC3 | 0.112 | 0.700 | 0.039 | -0.011 | 0.075 | 0.099 | 0.285 |

| PV1 | 0.163 | 0.088 | 0.890 | 0.285 | 0.051 | 0.201 | 0.174 |

| PV2 | 0.116 | 0.044 | 0.851 | 0.229 | 0.036 | 0.143 | 0.102 |

| SE1 | 0.426 | 0.153 | 0.890 | 0.909 | 0.325 | 0.486 | 0.008 |

| SE2 | 0.430 | 0.144 | 0.851 | 0.809 | 0.292 | 0.422 | 0.066 |

| PE1 | 0.262 | 0.069 | 0.259 | -0.063 | 0.741 | 0.342 | 0.097 |

| PE2 | 0.341 | 0.122 | 0.272 | 0.096 | 0.701 | 0.312 | 0.054 |

| PE3 | 0.241 | 0.226 | 0.271 | -0.001 | 0.715 | 0.324 | 0.135 |

| PE4 | 0.327 | 0.027 | 0.198 | 0.123 | 0.702 | 0.318 | 0.076 |

| BI1 | 0.435 | 0.152 | 0.460 | 0.186 | 0.319 | 0.779 | 0.166 |

| BI2 | 0.358 | 0.171 | 0.366 | 0.090 | 0.406 | 0.835 | 0.191 |

| BI3 | 0.359 | 0.199 | 0.413 | 0.207 | 0.371 | 0.763 | 0.151 |

| SI1 | 0.047 | 0.349 | 0.010 | 0.138 | 0.146 | 0.211 | 0.875 |

| SI2 | -0.016 | 0.404 | 0.049 | 0.082 | 0.108 | 0.169 | 0.793 |

| SI3 | 0.083 | 0.539 | 0.051 | 0.210 | 0.043 | 0.130 | 0.799 |

Evaluation of structural model and hypothesis testing

Bootstrapping procedure (Chin, 1998) with 5000 sub-samples was used to check the significance of relationships proposed in the model. The PLS-SEM method tests the relationships. The square residual (SRMR) value is 0.078, indicating a good model fit which is below the prescribed 0.08 (Henseler et al., 2014). In measuring the PLS model, we calculated R-square value, f-square, and Q-square (Henseler et al., 2016). These tests explain the dependent variables’ predictive power, effect size and predictive relevance. Our model finds 53.1 per cent variance in explaining the seller's BI for health care devices. The R-square value of 0.531 indicates good predictive accuracy of our model (Hair et al., 2019). Another method for predictive relevance is Q2, obtained through the blindfolding procedure available in PLS software. As per Hair et al., (2019), the 0.01, 0.15 and 0.35 values indicate small, medium and large effects. The endogenous construct, behavioural intention, has a Q2 value of 0.241. VIF values assess collinearity between constructs. As per Hair et al., (2019), the acceptable cut-off for the VIF is < 5. Table 6 shows that the VIF value for all constructs is below 2, indicating no collinearity.

Table 6.

VIF values

| Construct | VIF |

|---|---|

| Effort expectancy | 1.475 |

| Facilitating conditions | 1.414 |

| Perceived vulnerability | 1.482 |

| Self-efficacy | 1.140 |

| Performance expectancy | 1.283 |

| Social influence | 1.403 |

Structural relationships and hypothesis testing

After establishing model fit, the next step calculated standardized coefficients for the hypothesized relationships. Table 7 presents standardized beta coefficients, standard error, and t-value from bootstrapping procedure. EE (0.223, 0.000), PV (0.313, 0.000), PE (0.234, 0.00) and SI (0.153, 0.026) are significantly and positively related to seller’s BI. Hence, if the seller perceives the EM as important for business survival, their BI would increase. If the seller perceives the EM platform is easy to register and use, their BI would increase.

Table 7.

Structural relationships and hypothesis testing

| Hypotheses (and desired relationship) | Standardized Beta coefficients | Std. error | t-value | P-value & decision | 2.5% CI LL | 97.5% CI UL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effort expectancy → Behavioural intention | 0.223 | 0.059 | 3.747 | 0.000 (S) | 0.11 | 0.345 |

| Facilitating conditions → Behavioural intention | 0.004 | 0.075 | 0.054 | 0.957 (NS) | -0.14 | 0.148 |

| Perceived vulnerability → Behavioural intention | 0.313 | 0.076 | 4.128 | 0.000 (S) | 0.164 | 0.458 |

| Self-efficacy → Behavioural intention | 0.037 | 0.057 | 0.644 | 0.520 (NS) | -0.08 | 0.145 |

| Performance expectancy → Behavioural intention | 0.234 | 0.066 | 3.543 | 0.000 (S) | 0.094 | 0.351 |

| Social influence → Behavioural intention | 0.153 | 0.068 | 2.232 | 0.026 (S) | 0.015 | 0.279 |

[*S-supported *NS-Not Supported]

We also validate a positive relationship between PE and BI. The result confirms a significant impact of SI on BI. Further, SE (0.037, 0.52) and facilitating conditions (0.004, 0.957) do not significantly impact BI.

The findings show that age has a moderating effect in three of the six causal relationships: between PE and BI, EE and BI, and PV and BI. In particular, the difference between the path between PE and BI, and EE and BI favoured young sellers. In contrast, the difference between the path between PV and BI favoured older sellers.

The findings also show that EM has a moderating effect in three of the six causal relationships: between EE and BI, between PV and BI, and between SE and BI. In particular, the difference between EE and BI, and SE and BI favoured experienced sellers. In contrast, the path between PV and BI favoured less experienced sellers who joined the EM platform recently.

Importance performance matrix analysis (IPMA)

The IPMA analysis extends the results of structural relationships by accounting for the performance of each construct. As per Hair et al., (2019), IPMA analysis findings from PLS give direct, indirect and total relationships, and extend the analysis by incorporating another dimension by calculating the actual performance of each construct. An example of this calculation is given below since a five-point Likert scale was used:

If the response to X1 is, say 4, on a scale of 5, then, the rescaled score for performance is 75.

Results from the rescaled analysis and the initial analysis (total effects) are illustrated in Table 8. As shown in Table 9, although the construct self-efficacy has high performance (73.258), it is not a significant determinant in predicting BI of sellers in EM.

Table 8.

Result of multigroup analysis

| Age | EM Experience | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 35 | > = 35 | Diff | Low | High | Diff | |

| PE- > BI | 0.659 | 0.462 | S | 0.209 | 0.314 | NS |

| EE- > BI | 0.445 | 0.205 | S | 0.424 | 0.639 | S |

| SI- > BI | 0.374 | 0.336 | NS | 0.48 | 0.355 | NS |

| FC- > BI | 0.128 | 0.667 | NS | 0.005 | 0.08 | NS |

| PV- > BI | 0.546 | 0.637 | S | 0.491 | 0.215 | S |

| SE—> BI | 0.355 | 0.288 | NS | 0.5 | 0.657 | S |

Table 9.

IPMA results

| Construct | Total effect | Construct performances for BI |

|---|---|---|

| Effort expectancy | 0.223 | 76.448 |

| Facilitating conditions | 0.004 | 60.518 |

| Perceived vulnerability | 0.037 | 69.885 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.313 | 73.258 |

| Performance expectancy | 0.234 | 68.126 |

| Social influence | 0.153 | 55.907 |

The most critical construct in line with IPMA result is EE (76.448). This signifies that, particularly for the sellers in tier II cities, their registration on EM which displays products and other technical features should be easily understandable. Ease of effort will encourage use of EM. The third most important indicator was PV (69.885), indicating a higher possibility of intimidation of business closure. The chance of adopting protective behaviours increases as PV to a threat increase (Burns et al., 2017). As per results, social influence (55.907) is not a significant indicator because EM adoption is still in nascent stage for small sellers in India. If the peer group (SI), whose opinion is valued, refers to EM platform use, individuals are more likely to consider them for selling their products (Bozan et al., 2015). Therefore, EM marketers should work on strengthening the construct.

Discussion

The study aims to assess sellers’ behavioural intention to use EM during pandemic period. The study yields a few major findings. The findings suggest a positive impact of performance expectancy (PE) and effort expectancy (EE) of electronic market system on sellers' behavioural intention (BI), in line with previous findings in the literature (Idris et al., 2017; Uzoka, 2008). Studies illustrated that users would be more satisfied with new technology if they perceive it to be more useful in performing routine tasks (Pappas et al., 2014; Venkatesh et al., 2003). At the same time, the pandemic made sellers more aware of the role of technology in increasing operational efficiency and competitive advantage (Akpan et al., 2020). Recent pandemic-focused studies revealed that sellers consider electronic system's convenience of use, efficacy and technical capabilities, as beneficial to sustain their operations (Lynn et al., 2022; Raza & Khan, 2021). EMs provide a basic framework to manage product distribution, supply chain, customers interaction, packaging, financial assistance (Deng et al., 2019). This allows sellers to move forward without interruption (Lynn et al., 2022).

Results further confirm the significant impact of social influence (SI) on behavioural intention (BI). SI, in the context of the seller, means that the seller agrees with people associated with him/her that s/he should use this technology. Our results are similar to Chopdar and Sivakumar (2019), where SI significantly impacts BI. Substantial peer pressure to be present from electronic platforms may have attracted sellers' attention and engagement during the epidemic (Srivastava et al., 2021).

Kumar and Aydee (2021) claim that social communities influence sellers' decisions. The rise of social media and online reviews has made it more important for sellers to use online market places to stay ahead of competitors. Further, government facilitation through technology in B2B and B2C markets would improve ease of doing business and the ease of procurement for essential items for sellers during pandemic times (Sharma, 2022). It has also created new opportunities to create digital storefronts that connect people with those living around them. The analysis indicates that facilitating conditions (FC) do not have a significant impact on behavioural intention of sellers. The possible reason could be lack of knowledge of sellers about system capabilities and funding options, and special offers made by EM (Wang et al., 2006). At the same time, in response to COVID 19, sellers argue that policymakers are not prioritizing e-commerce enough in terms of resources, financial aid and operational bottlenecks.7 The results contradict past findings which indicated a positive impact of FC on using e-market places (Baptista & Oliveira, 2015; Chopdar & Sivakumar, 2019).

With respect to PMT determinants, perceived vulnerability was found to significantly impact behavioural intention of sellers. The findings indicated high vulnerability of the seller to the COVID 19 situation, which affects their perception of using EM. This phenomenon could be explained by the fact that small town sellers struggling to get back to a semblance of normalcy in an unstable pandemic environment were found to exhibit greater motivation to adopt existing EM's available in the market (Kumar & Ayedee, 2021). The epidemic has highlighted not only the relevance of digital technologies but also business vulnerabilities. Sellers or MSMEs benefit from EM since it facilitates cross-border trade and reduces the digital divide that improves business sustainability in tough times (Bandara et al., 2020). This improves the perception of sellers towards EM. As per the structural relationship results, self-efficacy (SE) does not significantly impact behavioural intention. This could be owing to sellers' lack of awareness and expertise of EM (Lynn et al., 2022). According to Costa and Castro (2021), self-efficacy is affected by SMEs' lack of technological readiness and digital literacy, affecting their ability to adopt EM in a pandemic scenario.

Result of importance-performance matrix analysis (IPMA) considers each construct's performance (Ringle and Marko, 2016). As per the IPMA results, social influence (55.907) is not a meaningful indicator. Reason may be that the tier II city respondents were only lately exposed to e-commerce-based businesses and lacked awareness of the benefits and technological knowledge related to the concept of e-business (Wang et al., 2006). Aggregators like Amazon recently announced a Local Stores initiative in India to influence sellers to move their offline corporations to the online platform.8 In these difficult times, it is more important than ever to educate sellers about the risks and benefits of e-commerce, and persuade them to use it. The IPMA score of SE is also determined to be of great importance. Thus, the SE score of IPMA 73.258 reflects tremendous potential for expansion for small-town merchants. One way to subsequently address this is by observing how other firms perform on EM, which would help in increasing a sense of trust in themselves.

Furthermore, the findings also show that sellers' age has a significant moderating effect on behavioural intention on three of the relationships namely PE, EE and PV. The result implies that young sellers found EM more relevant and useful for their business; at the same time, they also found registering in EM and selling through EM more convenient as compared to the older group. However, perceived vulnerability is found significantly high in older groups implying that they are more threatened about closure of business if they do not join EM as a platform to sell their products. During the COVID-19 pandemic, business obsolescence i.e., not having a presence in EMs and losing customers and business, acts as fear appeal (Tran, 2021). Lastly, analysis of the moderating effect of EM experience revealed that the relationship is significant in EE, PV and SE on sellers' BI. The path difference coefficient value implies that experienced sellers perceive EM as more convenient and are more confident about their skills in operating EM platform compared to sellers who have joined the EM platform more recently. The moderation on different profiles of sellers will help EM's in planning different ways of handholding sellers while bringing them online.

Theoretical implications

The study serves as a basis to better understand the behaviour of sellers belonging to Indian tier II/III cities, towards electronic markets, amid the restrictions imposed in Indian cities to check the pandemic. The article advances UTAUT and PMT factors to the EM adoption research from the sellers' perspective. Using an integrated model, it highlights sellers' functional and protective motives. The research highlighted the importance of technological, contextual, and motivational antecedents of EM adoption for small-town sellers.

The study's unique contribution is that all previous studies have tested EM adoption by targeting developed nations (Deng et al., 2019). Developed markets seem to have reached maturity and growth rate has become stagnant. Further, previous studies mainly emphasized customers' behavioural intention in tier I cities (Mehta et al., 2020). EMs are now targeting consumers as well as sellers located in small cities to enhance their reach and survivability. But no empirical study has addressed the need for small town sellers for electronic markets, in the changed consumer behaviour scenario during the pandemic. Traditional traders, who never intended to transact online, were forced to adopt innovative approaches after they ran out of options due to the pandemic (Naughton et al., 2020). Thus, there was a need to deeply analyze the dimensions of the UTAUT model, especially from the standpoint of sellers in cities that had recently adopted EM (Akpan et al., 2022). The study reveals that for sellers, technology attributes are critical in providing consumer services, improving transaction utility and other operational convenience. Regarding contextual determinants, the study revealed a significant impact of social influence but no influence of facilitating conditions on sellers' perceptions of EM adoption. This reflects a lack of knowledge about EM services and offers to sellers. However, the study found a positive impact of social influence from other competitors employing EMs. Moreover, people have used various social media channels to communicate about EM benefits and concerns (Hwang, 2009). Future research can explore these contextual drivers from the seller's perspective.

The results reinforce that PE has a positive influence on seller's behavioural intention to use EMs. Various studies confirmed the performance benefits of technology provided by EM as the main impetus among the respondents (Wang et al., 2006; Wijaya & Handriyantini, 2020; Iqbal, 2018). EE also influences the seller's BI. EMs provide the tools to manage operations and to sell successfully online. Conversely, past research concludes that effort expectancy does not affect sellers' intentions (Wijiya & Handriyantini, 2020).

The present study modifies the conceptual model to include PV and SE, and factors such as EE, FC, PE and SI. Thus, the UTAUT model is extended with constructs from PMT and tested to assess sellers' behavioural intention to launch on EM. Sellers remain a critical component in any EM, and understanding their BI is a major factor in its continued success and growth.

The study examines sellers' fear appeals and their adaptive responses during COVID 19 using the PMT model. The theory is used for assessing users’ motivation to protect themselves from perceived threats (Boss et al., 2015; Rainear & Christensen, 2017), which helped rationalize the current study. The findings suggest that sellers’ threat evaluation of business closure encouraged them to have positive views and intentions about selling online (Kumar & Ayedee, 2021). The study found that the COVID 19 epidemic increased sellers' fear appeal by highlighting operational and performance vulnerabilities owing to the constraints imposed. The study additionally discusses how electronic markets might help manage and prevent these threats by doing business online (Bandara et al., 2020). In future studies, researchers should examine how COVID 19 affects sellers' perceptions and coping mechanisms. However, the non-significance of self-efficacy suggests a lack of awareness of EM services, which may limit potential use (Costa & Castro, 2021). Researchers can start understanding how sellers' knowledge and digital literacy affect their efficacy to use technology.

The study also emphasizes the importance of seller characteristics—seller age and his/her IT experience, which are crucial to adopting e-commerce services (Goldsmith, 2002; Šumak et al., 2017). The justification for employing different profiles of sellers is that it may alter expectations from EM vendors. Results of the moderating impact, in theory, will help existing technology adoption models, and EMs are to devise strategies for easy and effective migration for all types of sellers. Future studies should focus on overcoming the barriers that prevent small firms from adopting and implementing digital technologies (Akpan, 2020).

Another implication of the present findings is the moderating influence of sellers' characteristics on their readiness to use e-markets. They offer a fresh perspective by highlighting elements that are important to different profiles of sellers when it comes to e-marketplace usage.

Practical implications

Due to COVID-19-induced forced compliance to several rules and restrictions, there was a lack of certainty about the adoption of EM by small firms who were apprehensive about EM market strategies and pricing policies. EMs charge commission which reduces profit percentage which, though valid in the short-term, does not apply in the long run. Small city sellers were apprehensive that adopting e-commerce would be a strategic mistake and a waste of existing resources as their target audience was well adjusted to offline transactions before the pandemic. However, developing better alternatives for tier II/III city firms could benefit in the long run. It was thus crucial to understand the perception of these sellers and the factors influencing their intention to adopt new EM platforms for business. The current study suggests an empirical model that could support future research in identifying additional factors, to get a clear picture of local sellers' perspectives on EM acceptance in India. The research supports pandemic as a catalyst for structural change in consumption and digital transformation in electronic markets. Despite EMs’ efforts to create a pleasant and hassle-free experience for sellers, the number of sellers or vendors on EMs has not increased much in smaller tier cities. EM Managers/Investors can use this study to understand the bottlenecks and factors that motivate tier II/III sellers to join them in order to recover or even grow sales during and after COVID-19 (Kim et al., 2020; Rahi et al., 2021). The EM option can be implemented with modest technical knowledge. Furthermore, low-cost/low-effort technologies can assist smaller firms in conducting virtual operations in times of community lockdown (Akpan et al., 2020) and help build a sustainable business.

In this article, we examine how the pandemic influenced digital transformation on the sellers’ ends as well, and how businesses might adapt to digital sales. Sellers’ insights during the pandemic indicate that the market is transitioning to e-commerce. The rise of online shopping provides new opportunities for harnessing success after COVID-19 (Knowles et al., 2020).

Limitations and future research directions

The research has certain limitations. Since data was collected during the pandemic through online questionnaires, the sellers were still adapting to the new environment. Hence, the method used for data collection may not have covered all aspects of the changing needs and nature of sellers' business. Future research could consider larger samples and longitudinal studies as well as target different dimensions such as price value, stress and other factors affecting sellers’ BI. Multi-group analysis based on different categories of products or services could also be conducted to understand the antecedents of EMs. Further research can explore post-adoption attributes such as sellers’ satisfaction and intention to continue using EMs. Future studies can also assess the relationship between BI and the actual usage of EM by sellers.

Conclusion

The current research contributes to the body of knowledge on EMs in Indian tier II and III cities. Small businesses were particularly vulnerable to economic downturns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic since they had limited resources to adapt to the changing circumstances. The study integrated the UTAUT model with additional constructs from PMT theory to evaluate small sellers' readiness to embrace EM for survival during the pandemic. Furthermore, it suggests that to successfully onboard new small sellers, EMs should understand their expectations, emphasize their benefits and provide them with an easy-to-use EM platform. Thus, by identifying characteristics that influence small sellers' intention, the current study provides information to support EM adoption by sellers in tier II and tier III cities.

Footnotes

Digital India allocation doubles to Rs. 3073 crore. Times Now. Retrieved from https://www.timesnownews.com

4E-commerce market in India may touch $100 billion by 2020: FICCI-KPMG report—ET CIO. (2015, December 9). Economic Times CIO. Retrieved from https://cio.economictimes.indiatimes.com

Pandemic tailwinds: E-commerce sales set to double in 2020 https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/info-tech/pandemic-tailwinds-push-e-commerce-growth-estimate-to-40-in-2020/article62197754.ece

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Richa Misra, Email: richa.misra@jaipuria.ac.in.

Renuka Mahajan, Email: renuka.mahajan@jaipuria.ac.in.

Nidhi Singh, Email: nidhi.singh@jaipuria.ac.in.

Sangeeta Khorana, Email: skhorana@bournemouth.ac.uk.

Nripendra P. Rana, Email: nrananp@gmail.com

References

- Abd Latif, A. R., Adnan, J., & Zamalia, M. (2011). Intention to use digital library based on modified UTAUT model: perspective of Malaysian postgraduate students. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, 116–122. 10.5281/zenodo.1058275

- Abubakar FM, Ahmad H. The moderating effect of technology awareness on the relationship between UTAUT constructs and behavioural intention to use technology: A conceptual paper. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research. 2013;3(2):14–23. doi: 10.52283/NSWRCA.AJBMR.20130302A02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agwu E, Murray PJ. Drivers and inhibitors to e-Commerce adoption among SMEs in Nigeria. Journal of Emerging Trends in Computing and Information Sciences. 2014;5(3):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action control (pp. 11–39). Springer.

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Theory of reasoned action-Theory of planned behavior. University of South Florida. 1988;2007:67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, M. M., & Parvez, N. (2009). Impact of service quality, trust, and customer satisfaction on customers loyalty. ABAC Journal, 29(1).

- Akpan, I. J., Udoh, E. A. P., & Adebisi, B. (2020). Small business awareness and adoption of state-of-the-art technologies in emerging and developing markets, and lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 1–18. 10.1080/08276331.2020.1820185

- Alhilali A. Technology adaptation model and road map to successful implementation of ITIL. Journal of Enterprise Information. 2013;26(5):553–576. doi: 10.1108/JEIM-07-2013-0041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]