Abstract

Background

The development of cardiac fibrosis involves the activation of cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) and their differentiation into myofibroblasts, which leads to the disruption of the extracellular matrix network. In the past few years, microRNAs (miRNA) have been described as potential targets for treating cardiac diseases. Although miR‐338‐3p has been shown to participate in the development of carcinoma, whether it affects cardiac fibrosis is unclear.

Methods

We examined the expression profiles of microRNAs in left ventricular samples of heart failure mice established by thoracic aortic constriction (TAC). Real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) was used to detect the expression of miR‐338‐3p. CCK‐8 assay/Transwell migration assay was used to measure the proliferation rate/migration of CFs. Luciferase reporter gene assay was used to test the binding between miR‐338‐3p and FGFR2.

Results

This study demonstrated that miR‐338‐3p was significantly decreased in thoracic aortic constriction mice. Cardiac miR‐338‐3p amounts were also reduced in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Interestingly, miR‐338‐3p overexpression inhibited α‐SMA, COL1A1, and COL3A1 expression, as well as cell proliferation and migration in CFs. Bioinformatics analysis and dual‐luciferase reporter assays revealed FGFR2 was targeted by miR‐338‐3p, whose antifibrotic effect could be alleviated by overexpression of FGFR2. Moreover, in DCM cases, serum miR‐338‐3p levels were markedly elevated in individuals with worse outcomes.

Conclusions

The present study provides evidence that miR‐338‐3p suppresses cardiac fibroblast activation, proliferation, and migration by directly targeting FGFR2 in mice. Besides, serum miR‐338‐3p might constitute a potential prognostic biomarker of dilated cardiomyopathy.

Keywords: cardiac fibroblast, cardiac fibrosis, FGFR2, miR‐338‐3p

miR‐338‐3p suppresses cardiac fibroblast activation, proliferation, and migration by directly targeting FGFR2.

1. INTRODUCTION

Myocardial fibrosis is a hallmark pathological change after myocardial injury, which features excessively high extracellular matrix (ECM) production that contributes to degrading the normal tissue architecture. 1 Myocardial fibrosis is tightly associated with reduced patient survival in heart failure (HF), 2 but its exact mechanism has not been fully clarified, while effective antifibrotic treatment approaches are lacking. 3 , 4 Of note, cardiac fibroblasts (CFs), as a major cardiac cell type in mammalians, play important roles during cardiac fibrosis. 5

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) represent small noncoding RNAs that suppress the expression of multiple genes by degrading or translationally inhibiting the mRNA targets. 6 It has been reported that dysregulation of miRNAs, including overexpression of profibrotic miRNAs (miR‐21 and miR‐223) 7 , 8 and downregulation of antifibrotic miRNAs (miR‐24 and miR‐26a), 9 , 10 is involved in cardiac fibrosis. The latter findings provide a new insight for exploring novel therapeutic approaches to reverse cardiac fibrosis.

Currently, miR‐338‐3p's involvement in cardiac fibrosis remains unclear, although emerging evidence suggests its role in the development of several cancers. Using miRNA arrays, this study demonstrated that miR‐338‐3p amounts were markedly decreased in ventricular specimens from transverse aortic constriction (TAC) mice as well as patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Furthermore, qPCR validated the downregulation of miR‐338‐3p in left ventricular (LV) tissue specimens. MiR‐338‐3p overexpression inhibited CF differentiation into myofibroblasts. Moreover, bioinformatics analysis and in vitro data revealed that fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2), belonging to the family of fibroblast growth factor receptors, was a direct miR‐338‐3p target. Collectively, these data provide evidence that miR‐338‐3p attenuates the activation of CFs through targeting of FGFR2. Therefore, miR‐338‐3p represents a potential target for cardiac fibrosis prevention.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Sample collection and ethics

Eight‐week‐old male and pregnant female C57BL/6 mice were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. All experiments followed the National Institute of Health Publication (1996) guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Revised No. 85–23).

Human left ventricular tissue specimens were taken from seven individuals with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) during heart transplantation. Non‐HF specimens were extracted from non‐HF donor hearts not meeting the criteria for cardiac transplantation (eight non‐HF donors). All participants or their immediate family members (for non‐HF donors) provided signed informed consent before enrollment.

Serum miR‐338‐3p amounts were measured in DCM cases. Totally 77 DCM patients were enrolled in Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital between January 1, 2016 and March 31, 2019. The diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy was based on the clinical manifestation of heart failure and the enlargement of left ventricular detected by echocardiography. Patients with confirmed etiologies of heart failure were excluded from this study (e.g., ischemic heart disease, alcoholic heart disease, hypertrophic heart disease, etc.). After 12–14 h of fasting, 5–10 ml of whole venous blood was collected from the elbow vein and centrifuged (3000 rpm, 10 min; ambient conditions). The resulting serum was kept at −80°C for further use. The primary study endpoint was the composite endpoint of cardiovascular adverse events, including all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, cardiac shock, readmission for heart failure, heart transplant, and malignant arrhythmia, during follow‐up. The mean follow‐up time was 1.73 years.

This trial had approval from the ethics committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital (No. GDREC2019546H[R1]). The Observational Study for Patients with Dilated Cardiomyopathy has been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov Protocol Registration and Results System (NCT04837612).

2.2. Animal model of heart failure established by thoracic aortic constriction

A mouse model of heart failure was established by thoracic aortic constriction (TAC), in 8‐week‐old male C57BL/6 mice. The mice were randomly allocated to two groups. In the TAC group for heart failure (group F), mice were performed transaortic arch constriction and normally fed for 4 weeks. Meanwhile, no surgery was performed in the non‐surgery group (group N). Surgery was carried out after approval from the ethics board of Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital (No. 2013081A), following the national and institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals. After 4 weeks, cardiac ultrasound was performed to confirm left ventricular enlargement and heart failure. Then, the mice were sacrificed after being weighed. Whole hearts were removed and weighed, and heart/body mass ratios were calculated. Cardiac tissue slides were made for H&E staining and Masson staining.

2.3. MiRNA and gene expression profiling

Total RNA extraction was carried out from ventricular tissue specimens from TAC and control mice. The obtained total RNA was utilized for miRNA arrays based on miRCURY LNA™ microRNA Array (service provided by Kangchen Biotech, Shanghai, China) and gene expression profiling on Arraystar LncRNA V3.0 (Arraystar Inc.,). Real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) was carried out to validate microarray data.

2.4. CF isolation and culture

CFs were isolated from neonatal (1–2 days old) C57BL/6 mice. Ventricle specimens were chopped before digestion with a mixture of 60% trypsin and 40% collagenase. After centrifugation, cell resuspension was performed with DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. This was followed by 2 h incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for fibroblast attachment. Third‐passage CFs were assessed in subsequent assays.

2.5. qRT‐PCR

Total RNA was obtained from heart specimens and CFs with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) as directed by the manufacturer. Total RNA (1.0 μg, 12 μl system) underwent reverse transcription with the ImProm‐II™ Reverse Transcription System (Promega). Then, mRNA quantification utilized SYBR GREEN qPCR Super Mix (Invitrogen) and the ABI PRISM® 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems. Normalization was carried out with 18S RNA. The Bulge‐Loop miRNA qPCR primer kit (RiboBio,) was utilized for miRNA quantitation, normalized to U6 expression.

2.6. Cell transfection

The miR‐338‐3p mimic/inhibitor and negative control (mimic/inhibitor‐NC) were obtained from RiboBio. Transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX as directed by the manufacturer. Passage‐3 CFs were transfected with miRNA mimic or inhibitor, in parallel with respective negative controls (50 nM). The overexpression plasmid vector of the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene was constructed by MingKong Biotechnology limited (Guangzhou, China), and transfected with Lipofectamine™ 2000 as directed by the manufacturer.

2.7. Luciferase reporter assay

The 3’UTR of FGFR2 mRNA comprising the target sequence of miR‐338‐3p (Genewiz,) was cloned into the psi‐CHECK2 Vector (MingKong Biotechnology limited), yielding the FGFR2 wt‐luc vector. Similarly, the 3’UTR of FGFR2 mRNA with mutant target sequence of miR‐338‐3p was cloned into the psi‐CHECK2 Vector to generate the FGFR2 mutant‐luc vector. Following 48 h of transfection, luciferase activity measurement was performed with the Dual‐Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) as directed by the manufacturer.

2.8. Immunoblot

Total protein extraction from cardiac fibroblast specimens with protein lysis buffer (RIPA) supplemented with 100 mM PMSF (Beyotime,). The BCA Protein Assay Kit (Keygen Biotech,) was utilized for protein quantitation. Equal amounts of total protein were resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE), followed by electro‐transfer onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes and blocking with 5% nonfat milk in tris buffered saline containing tween 20 (TBS‐T) for 1 h at ambient. Next, overnight incubation at 4°C was carried out with rabbit anti‐alpha‐smooth muscle actin (anti‐αSMA) (1:1000, Abcam), anti‐collagen type I alpha 1 (anti‐COL1A1) (1:3000, Abcam), anti‐collagen type I alpha 2 (anti‐COL1A2) (1:1000, Abcam), anti‐collagen type III alpha 1 (anti‐COL3A1) (1:5000, Abcam), and anti‐FGFR2 (1:1000, Abcam) primary antibodies.

Glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used for normalization. Then, samples were carried out with anti‐rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; 1:1000, Abcam) at ambient for 2 h. Finally, development was performed with Kodak film developer (FujiFilm,).

2.9. Cell proliferation assay

Transfected cells underwent seeding in 96‐well plates at 1 × 104/well, and cell proliferation was examined with Cell Counting Kit‐8 (Keygen Biotech,), as directed by the manufacturer. A microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was utilized for absorbance reading.

2.10. Transwell migration assay

Cardiac fibroblasts (1 × 105 cells) underwent seeding into transwell inserts containing 8‐μm polyethylene terephthalate membranes (BD, REF353097) in 24‐well plates containing 5% FBS, for 24 h incubation. Then, cell fixation was performed with 4% formalin for 20 min, followed by crystal violet (Sigma‐Aldrich) staining for 10 min. Migrated cells were viewed under a phase‐contrast microscope (Olympus CKX41), and imaged with an Olympus MC30 camera using the ImageJ 1.44 software (Java).

2.11. Immunofluorescence staining

CFs underwent fixation with 4% formalin (20 min at ambient). Then, cell permeabilization was performed with 0.2% Triton X‐100 for 20 min, followed by blocking with 10% goat serum in PBS‐T (1 h at ambient). Next, the samples underwent overnight incubation with anti‐α‐SMA‐Cy3 primary antibodies (1:500 in 10% goat serum; Sigma,) at 4°C. Phalloidin eFluor™ 660 (Invitrogen) was used for labeling cytoskeletal F‐Actin Cell as described by the manufacturer. Counterstaining was carried out with DAPI. Fifteen fields/specimens (200 x magnification) were examined microscopically.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SD and compared by two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test (group pairs) or one‐way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post‐test (multiple groups). p < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. MiR‐338‐3p is downregulated in cardiac fibrosis

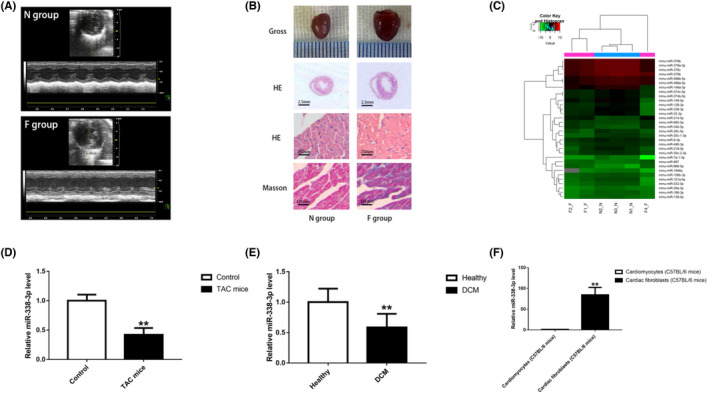

Compared with mice subjected to no surgery, TAC mice showed prominent LV enlargement and myocardial fibrosis, as indicated by ultrasound and Masson staining (Table S1, Figure 1A,B).

FIGURE 1.

MiR‐338‐3p is downregulated in cardiac fibrosis. A. M‐mode cardiac ultrasound was performed to confirm left ventricular enlargement and heart failure in TAC mice. B. Gross and histological observations indicated that TAC mice showed prominent LV enlargement and myocardial fibrosis. C. Heat map of myocardial miRNAs with differential expression between the F and N groups (n = 3). D. MiR‐338‐3p amounts were decreased in heart tissue specimens from the F group (n = 3) compared with the N group (n = 3). E. MiR‐338‐3p amounts were reduced in left ventricular specimens from DCM patients (n = 7) in comparison with healthy controls (n = 8). F. MiR‐338‐3p was mainly expressed in C57BL/6 mice CFs. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01 versus the corresponding control groups. DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; F group = mouse model of left ventricular enlargement and heart failure established by transversal aortic constriction(TAC); N group = normal control; CF = cardiac fibroblast

The miRNA profiling of ventricular tissue samples demonstrated a total of 28 dysregulated miRNAs (fold change >1.5 and p < 0.05), including 23 down‐regulated miRNAs and five up‐regulated miRNAs (Figure 1C). The top 10 differentially expressed miRNAs (Table S2) were chosen for validation by qRT‐PCR in both mouse heart and human left ventricular tissue samples.

Of note, as validated by qRT‐PCR, miR‐338–3p was strikingly downregulated in left ventricular tissue specimens collected from TAC mice compared with those from mice without surgery (fold change, 0.42; p < 0.01) (Figure 1D). Furthermore, we examined miR‐338–3p amounts in left ventricular tissue specimens from patients with DCM and non‐HF donors. Interestingly, miR‐338–3p expression was markedly decreased in left ventricular tissue from patients with DCM compared with non‐HF donors (fold change, 0.59; p < 0.01) (Figure 1E). Taken together, the above findings implicated a close association of miR‐338–3p with cardiac fibrosis.

Subsequently, to define miR‐338–3p's relative distribution across cardiac tissues, we isolated CFs and cardiomyocytes from neonatal C57BL/6 mice. As shown by qRT‐PCR, miR‐338–3p amounts were remarkably higher in fibroblasts in comparison with cardiomyocytes (Figure 1F). Thus, we hypothesized that miR‐338–3p potentially has an essential function in cardiac fibrosis progression by modulating the biological behavior of CFs. To test such hypothesis, in‐vitro studies were performed.

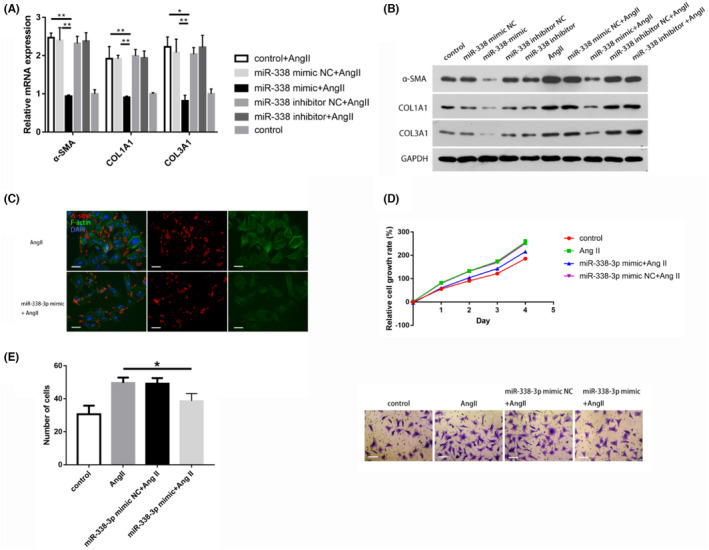

3.2. Overexpression of miR‐338‐3p suppresses angiotensin II‐induced cardiac fibroblast activation

Previous studies revealed CF activation and transformation into myofibroblasts as an essential etiological event in cardiac fibrosis. 11 To assess miR‐338–3p's effects on CF activation and phenotype transformation, CFs underwent transfection with 50 nM miR‐338–3p mimic/inhibitor and incubation for 48 h with exposure to Ang II at 100 nM. As anticipated, the mimic transfection group exhibited more than 5*104 fold of miR‐338–3p expression in comparison with mimic NC‐transfected cells (Figure S1). The amounts of α‐SMA, Col1A1, and Col3A1, key biomarkers of fibroblast activation, were significantly elevated after treatment with AngII and suppressed by miR‐338–3p overexpression (Figure 2A,B). Consistently, immunofluorescence staining indicated that versus NC‐treated cells, AngII‐stimulated CFs overexpressing miR‐338–3p demonstrated remarkably reduced proportion of differentiated myofibroblasts, as reflected by α‐SMA (red color) and F‐actin stress fibers (green color) (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2.

MiR‐338‐3p overexpression suppresses CF activation, proliferation, and migration. A. α‐SMA, COL1A1, and COL3A1 mRNA amounts in AngII‐stimulated CFs after transfection with 50 nM miR‐338‐3p mimic/inhibitor and respective negative controls, normalized to ß‐Actin expression. B. Protein amounts of α‐SMA, COL1A, and COL3A1 in CFs after transfection with 50 nM miR‐338‐3p mimic/inhibitor and respective negative controls in the presence or absence of AngII stimulation (100 nM), normalized to GADPH expression. C. Immunofluorescent staining of α‐SMA (red) and F‐Actin (green) in AngII‐induced CFs after transfection with 50 nM miR‐338‐3p mimic or control. Scale bar = 25 μm. D. Proliferation analysis (CCK‐8 assay) of AngII‐treated CFs after transfection with 50 nM miR‐338‐3p mimic or negative control. E. Transwell migration assay of AngII‐treated CFs after transfection with 50 nM miR‐338‐3p mimic or negative control. Scale bar = 50 μm. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01 versus respective controls. AngII = angiotensin II; α‐SMA = alpha smooth muscle Actin; CCK‐8 = Cell Counting Kit‐8; CFs = cardiac fibroblasts; COL1A1 = Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain; COL3A1 = Collagen Type 3 Alpha 1 Chain; FGFR2 = Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2; F‐Actin = Fibrous Actin; GADPH = glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; NC = negative control

3.3. MiR‐338‐3p overexpression attenuates proliferation and migration in CFs

Next, miR‐338‐3p's effects on CF proliferation were examined. AngII‐induced CFs underwent transfection with 50 nM miR‐338–3p mimic or NC for 48 h, followed by the CCK‐8 assay. The generated cell growth curves suggested that miR‐338‐3p overexpression suppressed CF proliferation in a time‐dependent manner (Figure 2D). Similarly, miR‐338‐3p overexpression starkly restrained CF migration, as revealed by the transwell migration assay (Figure 2E).

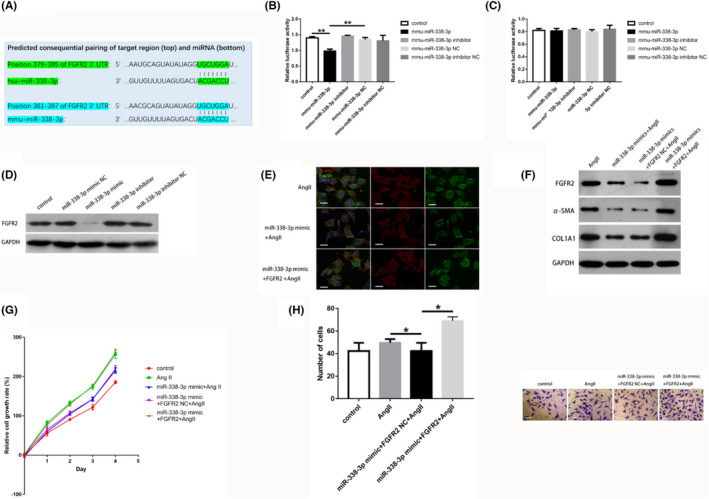

3.4. MiR‐338‐3p directly targets FGFR2

Given miR‐338‐3p's enrichment in CFs, along with the observed effect on CF activation, proliferation, and migration, we hypothesized that miR‐338‐3p potentially targets the 3´UTR of mRNA involved in the differentiation and biological behavior of CFs. The Targetscan algorithm (http://www.targetscan.org/) 12 disclosed the potential binding of miR‐338‐3p to FGFR2, a member of the FGFR family, which is involved in a wide array of pathways such as the RAS‐MAPK and PI3K‐AKT pathways (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/pathway.html).

MiR‐338‐3p (22 nt), particularly its seed sequence, is found on chromosome 17q25.3 in all mammalians. The predicted binding site is shown in Figure 3A. For validation, the 3’UTR of FGFR2 mRNA with mmu‐miR‐338‐3p binding site underwent cloning into the psiCHECK‐2 vector. Luciferase reporter assays confirmed that in 293 T cells, mmu‐miR‐338‐3p reduced the luciferase activity in the wild‐type group (Figure 3B), without influence on FGFR2 expression in the FGFR2 3’UTR‐mut group (Figure 3C), implying miR‐338‐3p directly targets the 3’UTR of FGFR2 mRNA.

FIGURE 3.

FGFR2 is a miR‐338‐3p target that blunts miR‐338‐3p‐mediated antifibrotic activity in CFs. A. Alignment of miR‐338‐3p and FGFR2 according to Targetscan (vertical bars), showing a high level of interaction and sequence conservation among mammalians. B and C. Luciferase activity assays demonstrated that the 3´‐UTR of FGFR2 was targeted by miR‐338‐3p. 293 T cells underwent transfection with FGFR2 3’‐UTR wild type reporter vector alongside miR‐338‐3p mimic and inhibitor, as well as respective controls (B). 293 T cells underwent transfection with FGFR2 3’‐UTR mutant reporter vector alongside 50 nM miR‐338‐3p mimic and inhibitor, as well as respective controls (C). D. Protein levels of FGFR2 were decreased significantly in CFs transfected with 50 nM miR‐338‐3p mimic. E. MiR‐338‐3p downregulated α‐SMA (red) and F‐Actin (green) in AngII‐induced CFs, which was reversed by FGFR2 overexpression. Scale bar = 25 μm. F. Protein amounts of α‐SMA and COL1A1 in AngII‐stimulated CFs after transfection with 50 nM miR‐338‐3p mimic and FGFR2‐overexpression plasmid, or respective negative controls. G. FGFR2 reversed the suppression of AngII‐treated CFs induced by 50 nM miR‐338‐3p (CCK8 assay). H. FGFR2 restored the inhibition of migration in AngII‐treated CFs in response to miR‐338‐3p overexpression (transwell assay). Scale bar = 50 μm. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01 versus respective controls. α‐SMA = alpha smooth muscle Actin; CCK‐8 = Cell Counting Kit‐8; CFs = cardiac fibroblasts; COL1A1 = Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain; FGFR2 = Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2; F‐Actin = Fibrous Actin; GADPH = glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; NC = negative control

To assess whether miR‐338‐3p regulates endogenous FGFR2 in CFs, 50 nM miR‐338‐3p mimic and inhibitor, and respective negative controls underwent transfection into CFs. As shown by immunoblot, miR‐338‐3p mimic significantly attenuated FGFR2 expression (Figure 3D), confirming miR‐338‐3p regulated endogenous FGFR2 in CFs.

To finally determine FGFR2’s effect on miR‐338‐3p‐related anti‐fibrotic activity in CFs, we transfected CFs with FGFR2 plasmid and/or miR‐338‐3p mimic followed by Ang II administration for 48 h. As expected, overexpression of FGFR2 restored the reductions of α‐SMA and COL1A1 amounts in CFs after miR‐338‐3p overexpression (Figure 3E,F). In addition, overexpression of FGFR2 blocked the repressive effects of miR‐338 on proliferation and migration in CFs challenged with Ang II (Figure 3G,H). Jointly, these findings revealed FGFR2 as a direct target of miR‐338‐3p controlling its potential effects during the development of cardiac fibrosis.

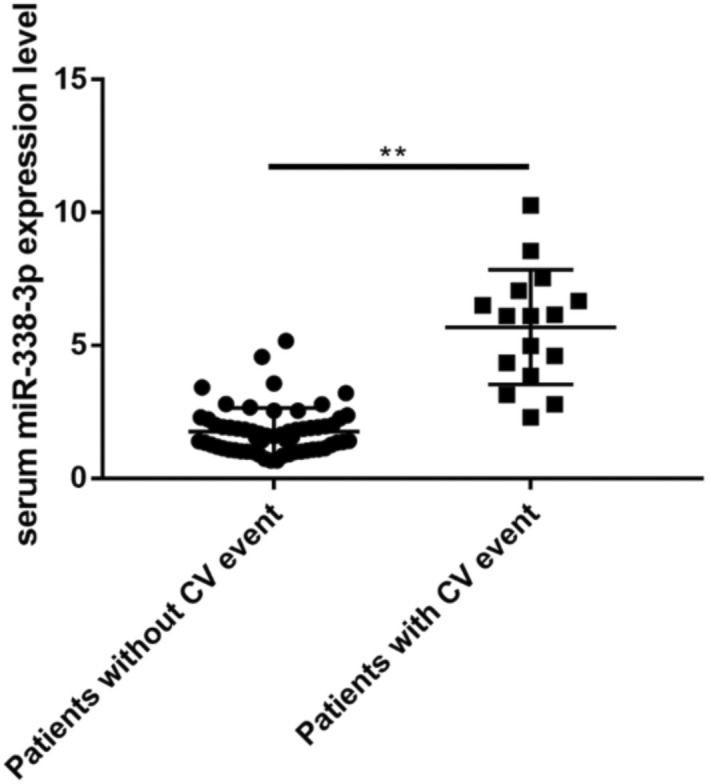

3.5. Serum miR‐338‐3p content is positively correlated with the incidence of cardiovascular adverse events in clinical dilated cardiomyopathy

Totally 77 patients with DCM were followed up for average of 1.73 years. The demographic characteristics of the DCM cohort, as stratified by the presence (n = 16) or absence (n = 61) of adverse cardiovascular events are listed in Table 1, revealing no marked differences between the two groups in gender, renal function, ventricular end diastolic diameter (LVDD), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), baseline heart rate, and corrected QT interval (QTc) (all p > 0.05). As detected by qRT‐PCR, serum miR‐338‐3p amounts at baseline were starkly raised in patients with adverse cardiovascular events, indicating that escalated serum miR‐338‐3p content at baseline was potentially related to poor prognosis in DCM (Figure 4).

TABLE 1.

Clinical demographic feature of patients in Figure 4

| Patients without CV events (n = 61) | Patients with CV events (n = 16) | p‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female), n (%) | 11 (18.0) | 6(37.5) | 0.095 |

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 45.71 ± 16.01 | 63.26 ± 16.80 | <0.001 |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/mL), mean ± SD | 3286.64 ± 4802.26 | 7154.09 ± 5549.53 | 0.007 |

| Creatinine (umol/L), mean ± SD | 99.13 ± 82.61 | 118.40 ± 41.72 | 0.371 |

| LVDD (mm), mean ± SD | 66.49 ± 10.44 | 68.81 ± 8.53 | 0.415 |

| LA (mm), mean ± SD | 44.69 ± 8.67 | 51.57 ± 12.00 | 0.015 |

| LVEF (%), mean ± SD | 28.49 ± 8.41 | 26.88 ± 9.30 | 0.506 |

| Baseline heart rate (bpm), mean ± SD | 91.69 ± 25.83 | 86.67 ± 19.68 | 0.489 |

| QTc (ms), mean ± SD | 462.73 ± 53.29 | 477.08 ± 43.19 | 0.373 |

FIGURE 4.

Serum miR‐338‐3p amounts at admission in individuals with or without cardiovascular adverse events during follow‐up. CV = cardiovascular. **, p < 0.01 versus respective controls

4. DISCUSSION

Cardiac fibrosis pathologically involves the activation of CFs, as reflected by the proliferation and migration of CFs, as well as fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts, which leads to excessive ECM accumulation. On the other hand, several miRNAs have been reported to be involved in cardiac fibrosis progression. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10

As shown above, miR‐338‐3p amounts were starkly decreased in ventricle samples from both TAC mice and patients with DCM. MiR‐338 has two mature forms, including miR‐338‐3p and miR‐338‐5p. Previous evidence suggests miR‐338‐3p suppresses migration, proliferation and invasion in several cancers such as glioblastoma and gastric cancer 13 , indicating its tumor suppressor activity via modulating of cellular biological behaviors. In another study, miR‐338‐3p was shown to be an antifibrotic miRNA suppressing cell activation and proliferation in hepatic stellate cells through miR‐338‐3p/CDK4 signaling. 14 Nevertheless, few data are available regarding miR‐338‐3p's involvement in cardiac fibrosis. The current work firstly reported that miR‐338‐3p was significantly decreased in ventricular tissue specimens from both TAC mice and patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Importantly, we observed that miR‐338‐3p was enriched in CFs in comparison with cardiomyocytes. Thus, miR‐338’s involvement in CF activation and differentiation during cardiac fibrosis was further demonstrated by in vitro studies. As shown above, miR‐338‐3p overexpression suppressed CF proliferation and migration, and downregulated Col1 and α‐SMA, two major markers of CF activation, thereby implying the suppressive effect of miR‐338‐3p on CF activation in cardiac fibrosis. However, miR‐338‐3p's effect in cardiac fibrosis deserved further validation in future in vivo studies.

Subsequently, we identified FGFR2, a member of the FGFR family, as a functional miR‐338‐3p target. The FGFR family contributes to the development of several cancers, through the activation of these receptors can lead to MAPK and PI3K‐AKT pathway activation. 15 , 16 , 17 Furthermore, it was reported that fibroblast‐specific FGFR2 gene disruption alleviates kidney fibrosis following ischemia/reperfusion injury in a mouse model. 18 However, to date, FGFR2 function in cardiac fibrosis has not been clearly determined. As demonstrated above, miR‐338‐3p overexpression decreased FGFR2 amounts in CFs; further, luciferase reporter assays confirmed miR‐338‐3p directly targeted FGFR2. On the other hand, FGFR2 overexpression upregulated Col1 and α‐SMA, and attenuated the antifibrotic activity of miR‐338‐3p on CFs. Jointly, these findings supported that miR‐338‐3p attenuates the development of cardiac fibrosis through targeting of FGFR2 in CFs. Hence, this report indicated that miR‐338‐3p and its target FGFR2 may represent two potential treatment targets for developing a new metabolically oriented approach to combat cardiac fibrosis and heart failure. Nonetheless, this requires further investigation. One of the major issues is the pleiotropic effects of miRNAs. In the case of miR‐338‐3p, systemic treatment might affect other processes, resulting in unexpected deleterious effects. In addition, current treatments applying miRNAs are not cell‐specific and cause a rather general overexpression of microRNAs. Still, the current findings provide new insights into cardiac fibrosis in heart failure, which may inform the development of new therapeutics.

Recently, miRNAs have been found in a stable form in body fluids, often packaged in extracellular vesicles. 19 Consequently, miRNAs have emerged as biomarkers of cardiovascular disease. 20

Of interest, we noted that serum miR‐338‐3p levels were starkly elevated in dilated cardiomyopathy patients with poor outcomes. Meanwhile, miR‐338‐3p was downregulated in dilated cardiomyopathy ventricular specimens compared with normal controls. This discrepancy could be attributed to two points. First, serum levels of miRNAs can be regulated by multiple factors, and the left ventricular tissue may not be the only source of miR‐338‐3p in vivo. Secondly, dilated cardiomyopathy patients with poor outcomes probably have faster progression of cardiac fibrosis, and the antifibrotic factor miR‐338‐3p may be elevated due to negative feedback against fibrosis derived from the body, which deserves further investigation.

5. CONCLUSION

In summary, this study demonstrated that miR‐338‐3p suppresses CF activation, proliferation, and migration through targeting of FGFR2 on CFs in mice. Serum miR‐338‐3p represents a potential prognostic biomarker of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C H, R W, ZJ W, and Z F carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. JJ L and YL H performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. JD X, M W, YH W, and WX M helped to collect the biological samples. M W designed the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest.

INFORMED CONSENT STATEMENT

The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This trial had approval from the ethics committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital (No. GDREC2019546H[R1]). All participants or their immediate family (for non‐HF donors) signed written informed consent before being enrolled in the present study. The Observational Study for Patients with Dilated Cardiomyopathy has been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov Protocol Registration and Results System (NCT04837612).

RESEARCH INVOLVING ANIMALS

All experiments followed the National Institute of Health Publication (1996) guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Revised No. 85–23).

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

All participants or their immediate family (for non‐HF donors) signed written informed consent before enrolled in the present study.

The expression level of serum miR‐338‐3p was measured in patients with DCM. 77 DCM patients were enrolled from Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital from January 1, 2016 to March 31, 2019.

CONSENT TO PUBLISH

Not applicable.

Supporting information

AppendixS 1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

Huang C, Wang R, Lu J, et al. MicroRNA‐338‐3p as a therapeutic target in cardiac fibrosis through FGFR2 suppression. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36:e24584. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24584

Cheng Huang, Rui Wang, Jianjun Lu, and Yongli He Co‐first author.

Funding information

The current study was funded by the National Science Foundation of China (No. 81300230) to Huang. Guangdong Foundation of Medical Science (No. C2019043) to Huang, Guangzhou Foundation of Science and Technology (No. 202102080011) to Wu, Guangzhou Foundation of Science and Technology (No. 202102020500) to Wang.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ma ZG, Yuan YP, Wu HM, Zhang X, Tang QZ. Cardiac fibrosis: new insights into the pathogenesis. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14:1645‐1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsigkou V, Siasos G, Bletsa E, et al. The predictive role for ST2 in patients with acute coronary syndromes and heart failure. Curr Med Chem. 2020;27:4479‐4493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stratton MS, Bagchi RA, Felisbino MB, et al. Dynamic chromatin targeting of BRD4 stimulates cardiac fibroblast activation. Circ Res. 2019;125:662‐677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aghajanian H, Kimura T, Rurik JG, et al. Targeting cardiac fibrosis with engineered T cells. Nature. 2019;573:430‐433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Takeda N, Manabe I, Uchino Y, et al. Cardiac fibroblasts are essential for the adaptive response of the murine heart to pressure overload. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:254‐265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pasquinelli AE. MicroRNAs and their targets: recognition, regulation and an emerging reciprocal relationship. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:271‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu X, Xu Y, Deng Y, Li H. MicroRNA‐223 regulates cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction by targeting RASA1. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;46:1439‐1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, et al. MicroRNA‐21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature. 2008;456:980‐984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang B, Zhang A, Wang H, et al. miR‐26a limits muscle wasting and cardiac fibrosis through exosome‐mediated microRNA transfer in chronic kidney disease. Theranostics. 2019;9:1864‐1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang J, Huang W, Xu R, et al. MicroRNA‐24 regulates cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:2150‐2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nagaraju CK, Robinson EL, Abdesselem M, et al. Myofibroblast phenotype and reversibility of fibrosis in patients with end‐stage heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2267‐2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife. 2015;4:e05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang WY, Lu WC. Reduced expression of hsa‐miR‐338‐3p contributes to the development of glioma cells by targeting mitochondrial 3‐Oxoacyl‐ACP synthase (OXSM) in glioblastoma (GBM). Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:9513‐9523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duan B, Hu J, Zhang T, et al. miRNA‐338‐3p/CDK4 signaling pathway suppressed hepatic stellate cell activation and proliferation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang T, Liu D, Wang Y, et al. FGFR2 promotes gastric cancer progression by inhibiting the expression of Thrombospondin4 via PI3K‐Akt‐Mtor pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;50:1332‐1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pfaff MJ, Xue K, Li L, Horowitz MC, Steinbacher DM, Eswarakumar JVP. FGFR2c‐mediated ERK‐MAPK activity regulates coronal suture development. Dev Biol. 2016;415:242‐250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li XY, Tao H, Jin C, et al. Cordycepin inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo via targeting FGFR2 and blocking ERK signaling. Chin J Nat Med. 2020;18:345‐355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu Z, Dai C. Ablation of FGFR2 in fibroblasts ameliorates kidney fibrosis after ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Kidney Dis (Basel). 2017;3:160‐170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Creemers EE, Tijsen AJ, Pinto YM. Circulating microRNAs: novel biomarkers and extracellular communicators in cardiovascular disease? Circ Res. 2012;110:483‐495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhu H, Fan GC. Extracellular/circulating microRNAs and their potential role in cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;1:138‐149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

AppendixS 1

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.