Abstract

Background

Mucormycosis is a rare invasive fungal disease with high mortality. Early diagnosis and targeted drugs are crucial to improving clinical outcomes.

Methods

We searched the electronic hospital database of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine for adult patients with mucormycosis between 2000 and 2021. Demographic, clinical, treatment, and outcome data were collected and compared with the data in the relevant literature.

Results

Eleven cases of mucormycosis—four of multisite infection, one of skin infection, five of lung infection, and one of gastrointestinal infection—were found and analyzed. The patients were diagnosed mainly based on pathological and histological findings, and three patients had metagenomic next‐generation sequencing findings. Delayed diagnosis (i.e., diagnosis >7 days after patient admission or >30 days after onset of symptoms) results in poor prognosis compared with early diagnosis.

Conclusions

Improving awareness and shortening diagnosis time may improve the prognosis of mucormycosis. If mucormycosis is suspected, appropriate samples should be collected as soon as possible and submitted for biopsy, culture, or mNGS to confirm the diagnosis.

Keywords: biopsy, culture, early diagnosis, metagenomic next‐generation sequencing (mNGS), mucormycosis

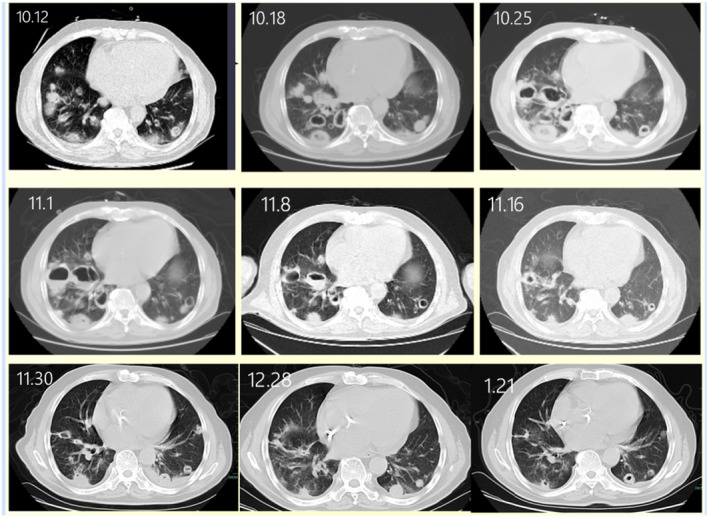

Patient 8 was admitted to the hospital because of a cough and sputum for 3 days. Bronchoscopy was performed, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was used for culture and mNGS. BALF mNGS revealed Rhizopus, and sputum fungal culture revealed a small amount of Rhizopus. Lung computed tomography (CT) changes in patient 8 from admission (October 12, 2021) to the first follow‐up after discharge (January 21, 2022) are shown in Figure 1.

1. INTRODUCTION

Mucormycosis is a rare invasive fungal disease. It is associated with significant morbidity in patients with poor immune function, especially in patients with diabetes, those undergoing chemotherapy or cancer immunotherapy, solid organ, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, those with hematological malignancies, and those treated with long‐term corticosteroids. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 A study from India published in 2019 identified post‐pulmonary tuberculosis (6.9%) and chronic kidney disease (8.9%) as emerging risk factors of mucormycosis. 6

The reported incidence of mucormycosis has been increasing. 9 Mucormycosis is a serious disease; it progresses rapidly and the mortality rate is high, ranging from 40% to 80%. 5 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Common antifungal drugs are often ineffective against mucormycosis, and the current first‐line monotherapy drugs include amphotericin B/amphotericin B lipid complex, isavuconazole, and posaconazole. 4 The effectiveness of combination therapy is not yet clear and may be considered if there is no significant increase in toxicity. 4 The time required to treat mucormycosis is unknown and may range from weeks to months. 4

Early treatment of mucormycosis is very important; previous studies have shown that delayed therapy after diagnosis is an important factor in the reported adverse results. 1 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 8 As targeted drugs become more accessible, early diagnosis becomes crucial for improving clinical outcomes. However, early diagnosis is difficult because mucormycosis is rare.

This study aimed to showcase the accumulated experience of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine in the management of patients with mucormycosis, discuss potential gaps in diagnostic methods, and share methodological recommendations.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The cases of mucormycosis in the hospital's electronic database were reviewed, and all adult patients (>18 years of age) diagnosed with mucormycosis between 2000 and 2021 were included. In addition, demographic and clinical data from the clinical records of the included patients were obtained.

The infection was classified according to the site of infection and included pulmonary mucormycosis (PM), gastrointestinal mucormycosis (GM), and cutaneous mucormycosis (CM). If two or more non‐adjacent parts were involved, it was classified as disseminated disease (DM).

The diagnostic criteria were based on the consensus definition of invasive fungal disease. 4 For patients with susceptibility risk factors, compatible clinical and radiological characteristics, and systemic antifungal improvement, the disease was classified as invasive mucormycosis (IM). The diagnosis was confirmed by the growth of Mucor on culture, histopathological examination showing the fungal structure compatible with Mucor, or metagenomic next‐generation sequencing (mNGS).

Differences in the year of diagnosis, time from patient admission to diagnosis (days), and time from symptoms to diagnosis (days) were also determined. The clinical outcomes were survival or death.

Categorical variables were compared using Pearson's chi‐squared test, and continuous variables were compared using Student's t test. Survival curves of patients who received early diagnosis vs. those who received delayed diagnosis were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences in the survival rates between two groups were analyzed using the log‐rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS test (v. 21.0).

3. RESULTS

A total of 11 patients with IM were identified. Table 1 summarizes the details of each case. Patient 10 experienced nausea and abdominal distension after taking posaconazole for 1 month, while the other patients showed no obvious discomfort in response to posaconazole.

TABLE 1.

Details of patients with mucormycosis diagnosed at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine from 2010 to 2021

| Nu | Age | Type | Predisposing condition(s) | Immunosuppressive or chemotherapy | T1 | T2 | T3 | Diagnosis method (s) | Treatment (time: month) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 | DM | LT and DM1 | Immunosuppressive | 2012 | 37 | 39 | Culture | AB (1 month) | 1 |

| 2 | 62 | CM | LT | Immunosuppressive | 2014 | 6 | 21 | Biopsy | AB + P (2 months) | 0 |

| 3 | 45 | DM | Leukemia | Chemotherapy | 2016 | 27 | 36 | Culture | AB (1 month) | 1 |

| 4 | 67 | PM | Cancer | No | 2019 | 58 | 60 | Biopsy | P (0.5 months) | 1 |

| 5 | 47 | DM | LT | Immunosuppressive | 2020 | 27 | 37 | Culture | AB + P (1 month) | 1 |

| 6 | 65 | GM | KT | Immunosuppressive | 2020 | 1 | 21 | Biopsy | AB (1 month) → P (0.5 month) | 0 |

| 7 | 31 | DM | KT | Immunosuppressive | 2021 | 1 | 7 | mNGS | AB (0.5 month) → P (6 months) | 0 |

| 8 | 62 | PM | AAV | Immunosuppressive | 2021 | 3 | 6 | mNGS and culture | AB + P (2.5 months) → P (>2 months) | 0 |

| 9 | 67 | PM | TB | No | 2021 | 6 | 36 | Culture | P (4 months) | 0 |

| 10 | 73 | PM | Cancer | No | 2021 | 4 | 34 | Culture | P (1 month) | 0 |

| 11 | 73 | PM | KC and DM1 | No | 2021 | 5 | 25 | mNGS and culture | P (2 months) | 0 |

Note: 0 means survival and 1 means death.

Abbreviations: AAV, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody‐associated vasculitis; AB, amphotericin B; CM, cutaneous mucormycosis; DM, disseminated mucormycosis; DM1, diabetes mellitus; GM, gastrointestinal mucormycosis; KC, kidney cancer; KT, kidney transplantation; LT, liver transplantation; mNGS, metagenomic next‐generation sequencing; Nu, patient number based on the time of diagnosis; P, posaconazole; PM, pulmonary mucormycosis; T1, year of diagnosis; T2, time from patient admission to diagnosis (days); T3, Time from symptom onset to diagnosis (days); TB, tuberculosis.

The microbial culture method was used to diagnose mucormycosis in patients 1, 3, 5, 9, and 10. This approach often has a long turnaround time and requires discussion with multiple physicians to analyze the results and reach a diagnosis. Biopsy was used to diagnose mucormycosis in patients 2, 4, and 6. The time to diagnose mucormycosis via biopsy was equivalent to the time for surgery and collection of biopsy specimens. mNGS was used for diagnosing mucormycosis in patients 7, 8, and 11. mNGS results of the three patients were reported <2 days after specimen acquisition. Details of the strains detected by mNGS are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Results of metagenomics next‐generation sequencing (mNGS) in three patients

| Nu | Name | Sequence number | Name | Sequence number | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Mucor | 108 | Mucorracemosus | 88 | 95.0% |

| 8 | Rhizopus | 7 | Rhizopus microsporus | 7 | 99.0% |

| 11 | Lichtheimia | 32 | Lichtheimia ramose | 32 | 99.0% |

Abbreviation: Nu, patient number based on the time of diagnosis.

Patient 7 was admitted to the hospital because of a fever for 6 days. The patient had a history of kidney transplantation. One day after admission, blood mNGS was positive for Mucor. Therefore, amphotericin B was prescribed for antimucormycosis treatment. Half a month later, he was discharged in stable condition, and amphotericin B prescription was changed to oral posaconazole for antimucormycosis treatment.

Patient 8, who had a history of voriconazole prophylaxis, was admitted to the hospital because of a cough and sputum for 3 days. He had a history of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)‐associated vasculitis treated with corticosteroid and cyclophosphamide therapy. Bronchoscopy was performed, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was used for culture and mNGS. BALF mNGS revealed Rhizopus, and sputum fungal culture revealed a small amount of Rhizopus. Thus, amphotericin B and posaconazole were prescribed for anti‐mucormycosis treatment. The patient was discharged after two and a half months after his condition stabilized, and amphotericin B and posaconazole were replaced with oral posaconazole for anti‐mucormycosis treatment. Lung computed tomography (CT) changes in patient 8 from admission (October 12, 2021) to the first follow‐up after discharge (January 21, 2022) are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Computed tomography (CT) scan showing changes in the lungs of patient 8

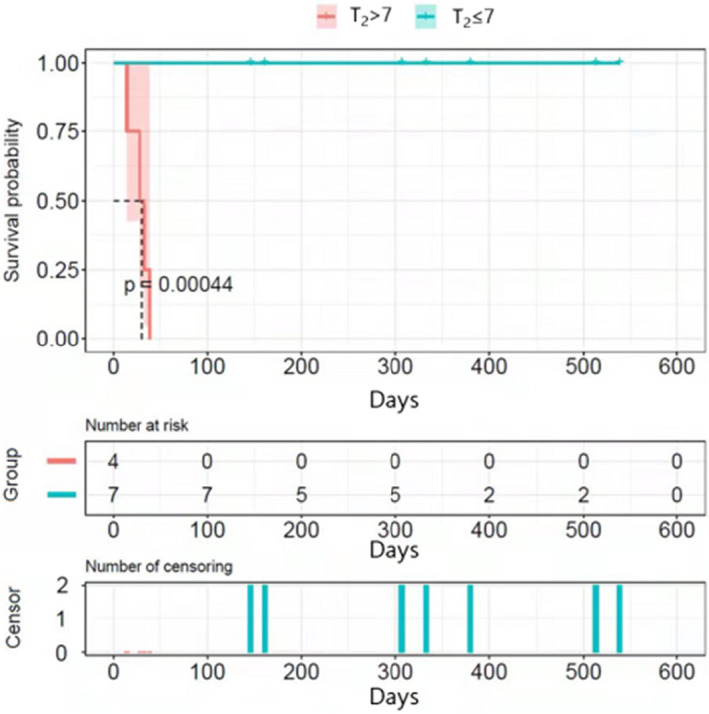

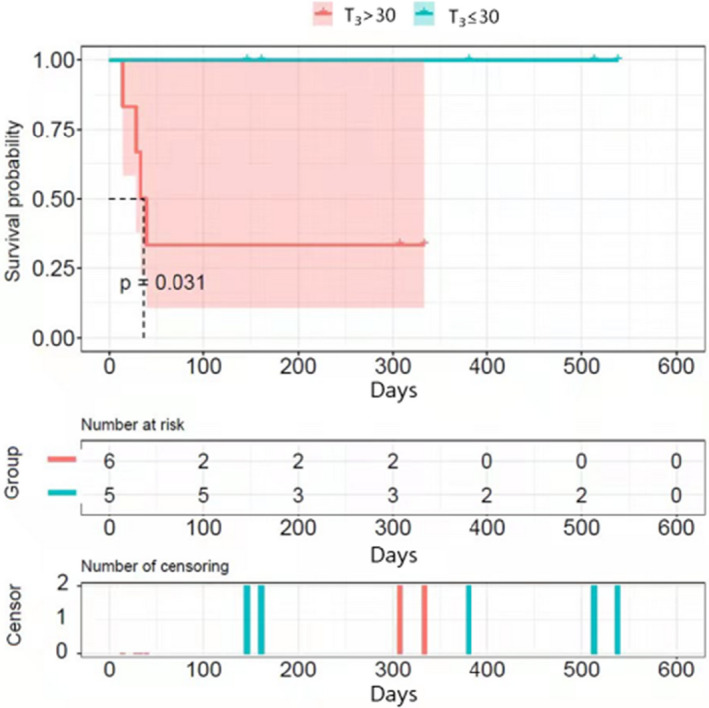

Seven patients were discharged under stable conditions, whereas the other four patients died. Table 3 summarizes the clinical data of the two patient groups based on clinical outcomes. Figures 2 and 3 show the survival curves of patients who received an early diagnosis vs. those who received a delayed diagnosis.

TABLE 3.

Clinical data of two patient groups divided based on clinical outcome

| Survival (n = 7) | Death (n = 4) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 61.9 ± 5.4 | 50.0 ± 5.9 | 0.189 |

| WBC count | 10.9 ± 2.1 | 13.3 ± 4.1 | 0.580 |

| Neutrophils% | 78.7 ± 4.6 | 65.5 ± 20.3 | 0.567 |

| Lymphocyte% | 12.1 ± 2.9 | 22.0 ± 15.7 | 0.578 |

| CRP | 93.3 ± 34.2 | 43.0 ± 32.1 | 0.357 |

| PCT | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.630 |

| T2 | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 37.3 ± 7.3 | 0.019 |

| T2 > 7 | 0.0% (0/7) | 100.0% (4/4) | 0.003 |

| T3 | 21.4 ± 4.4 | 43.0 ± 5.7 | 0.016 |

| T3 > 30 | 28.6% (2/7) | 100.0% (4/4) | 0.061 |

Abbreviations: CRP, C‐reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; T2, time from patient admission to diagnosis (days); T3, tTime from symptom onset to diagnosis (days); WBC, white blood cell.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival after the admission. The two groups are divided based on T2, the time from patient admission to diagnosis (days)

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival after admission. The two groups are divided based on T3, the time from symptoms to diagnosis (days)

4. DISCUSSION

Higher awareness of mucormycosis and the availability of better diagnostic tools may promote the early diagnosis of mucormycosis in high‐risk patients. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 The cases we analyzed were largely from recent years. This may be due to the increase in the population at risk, the availability of improved diagnostic methods, and the recently gained experience with Mucor fungi diagnosis.

Until 2 years before conducting this study, that is, until 2020, biopsy and culture were the main diagnostic methods employed at our hospital. Coupled with inexperience, diagnosis often takes a long time and the prognosis is poor. Here, we reported four cases of disseminated mucormycosis, three of which—patients 1, 3, and 5—were diagnosed using microbial culture. Microbial culture remains an essential tool for diagnosing mucormycosis. However, the culturing of microorganisms requires suitable conditions, culture time is long, the operation is complicated, the detection rate is low, and extensive medical staff experience is required. 14 , 15 Three patients with delayed diagnosis died. Mucormycosis is an invasive fungal disease, 16 , 17 and Mucor infection is characterized by blood vessel invasion. 18 Patient 7 was tested using mNGS, which has a short turnaround time; the quick detection of Mucor mold via mNGS facilitated rapid diagnosis and timely treatment.

The early diagnosis of mucormycosis is of utmost importance for improving patient outcomes. 1 However, considering that this disease is rare, mucormycosis is not suspected except in the case of a high degree of suspicion. Diagnosis involves the recognition of risk factors, assessment of clinical manifestations, early use of imaging modalities, and prompt initiation of diagnostic methods based on histopathology, culture, and advanced molecular techniques. 9 We reported five cases of pulmonary mucormycosis. Although the clinical manifestations and chest CT findings were not specific in all five cases, some cases were highly suspicious. For example, patient 8 had ANCA‐associated vasculitis and regularly took immunosuppressive agents. He also had a history of voriconazole prophylaxis, which suggested a high risk of mucormycosis. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 Bronchoscopy is convenient at our hospital. Therefore, the patient's BALF was tested immediately using mNGS and culture, and mucor mold was quickly found, which clarified the diagnosis and accelerated the treatment of mucormycosis. Therefore, mNGS is an excellent tool for early pathogenic detection and may prove to be especially useful for the confirmation of highly suspicious cases.

In recent years, mNGS has been increasingly used at our hospital for the diagnosis of unknown rare pathogenic infections. It can simultaneously detect almost any DNA or RNA information in a sample. It does not require assumptions about the type of infection‐causing pathogen. 23 , 24 With mNGS, unculturable or difficult‐to‐cultivate microbial species, as well as unknown or rare microbial species can be identified in complex samples. 25 Moreover, mNGS offers the advantage of a short turnaround time and can be used for genus and species identification. Thus, mNNGS results often provide valuable hints for culture.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Mucormycosis is characterized by difficult diagnosis, rapid progression, and a high fatality rate. The prognosis of mucormycosis infection is rapid, and thus, the clinical outcome can benefit greatly by improving awareness and early diagnosis using diagnostic methods with a short turnaround time. An effective multidisciplinary approach is essential to achieving this goal. We postulate that when mucor infection is suspected, appropriate samples should be collected as soon as possible and submitted for biopsy, culture, or mNGS to confirm the diagnosis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

No.

Wang J, Wang Y, Han F, Chen J. Multiple diagnostic methods for mucormycosis: A retrospective case series. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36:e24588. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24588

JiaXin Wang and YaoMin Wang contributed equally to this work.

Funding information

This study received no external funding.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chamilos G, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Delaying amphotericin B‐based frontline therapy significantly increases mortality among patients with hematologic malignancy who have zygomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:503‐509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vaughan C, Bartolo A, Vallabh N, Leong SC. A meta‐analysis of survival factors in rhino‐orbital‐cerebral mucormycosis—Has anything changed in the past 20 years? Clin Otolaryngol. 2018;43:1454‐1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sun HY, Singh N. Mucormycosis: its contemporary face and management strategies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:301‐311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cornely OA, Alastruey‐Izquierdo A, Arenz D, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the mycoses study group education and research consortium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(12):e405‐e421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634‐653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prakash H, Ghosh AK, Rudramurthy SM, et al. A prospective multicenter study on mucormycosis in India: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Med Mycol. 2019;57:395‐402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Corzo‐Leon DE, Chora‐Hernandez LD, Rodriguez‐Zulueta AP, Walsh TJ. Diabetes mellitus as the major risk factor for mucormycosis in Mexico: epidemiology, diagnosis, and outcomes of reported cases. Med Mycol. 2018;56:29‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cuenca‐Estrella M, Bernal‐Martinez L, Isla G, Gomez‐Lopez A, Alcazar‐Fuoli L, Buitrago MJ. Incidence of zygomycosis in transplant recipients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:37‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Skiada A, Pavleas I, Drogari‐Apiranthitou M. Epidemiology and diagnosis of mucormycosis: an update. J Fungi (Basel). 2020;6(4):265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guinea J, Escribano P, Vena A, et al. Increasing incidence of mucormycosis in a large Spanish hospital from 2007 to 2015: epidemiology and microbiological characterization of the isolates. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marty FM, Ostrosky‐Zeichner L, Cornely OA, et al. Isavuconazole treatment for mucormycosis: a single‐arm open‐label trial and case‐control analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:828‐837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shoham S, Magill SS, Merz WG, et al. Primary treatment of zygomycosis with liposomal amphotericin B: analysis of 28 cases. Med Mycol. 2010;48:511‐517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Legrand M, Gits‐Muselli M, Boutin L, et al. Detection of circulating mucorales DNA in critically ill burn patients: preliminary report of a screening strategy for early diagnosis and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:1312‐1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Walsh TJ, Gamaletsou MN, McGinnis MR, Hayden RT, Kontoyiannis DP. Early clinical and laboratory diagnosis of invasive pulmonary, extrapulmonary, and disseminated mucormycosis (Zygomycosis). Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:S55‐S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nam BD, Kim TJ, Lee KS, Kim TS, Han J, Chung MJ. Pulmonary mucormycosis: risk factors, radiologic findings, and pathologic correlation. Eur Radiol. 2018;28:788‐795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jeong W, Keighley C, Wolfe R, et al. The epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of case reports. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:26‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chitasombat M, Niparuck P. Deferiprone as adjunctive treatment for patients with invasive mucormycosis: a retrospective case series. Infect Dis Rep. 2018;10:7765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Muggeo P, Calore E, Decembrino N, et al. Invasive mucormycosis in children with cancer: a retrospective study from the infection working Group of Italian Pediatric Hematology Oncology Association. Mycoses. 2019;62:165‐170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marty FM, Cosimi LA, Baden LR. Breakthrough zygomycosis after voriconazole treatment in recipients of hematopoietic stem‐cell transplants. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:950‐952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Imhof A, Balajee SA, Fredricks DN, Englund JA, Marr KA. Breakthrough fungal infections in stem cell transplant recipients receiving voriconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:743‐746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Siwek GT, Dodgson KJ, De Margarida M‐S, et al. Invasive zygomycosis in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients receiving voriconazole prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:584‐587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chamilos G, Marom EM, Lewis RE, Lionakis MS, Kontoyiannis DP. Predictors of pulmonary zygomycosis versus invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:60‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rytter H, Jamet A, Coureuil M, Charbit A, Ramond E. Which current and novel diagnostic avenues for bacterial respiratory diseases? Front Microbiol. 2020;11:616971‐616971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haidar G, Singh N. Fever of unknown origin. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(5):463‐477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gu W, Miller S, Chiu CY. Clinical metagenomic next‐generation sequencing for pathogen detection. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019;14:319‐338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]