Abstract

We evaluate quartile rankings of countries during the Covid-19 pandemic using both official (confirmed) and excess mortality data. By December 2021, the quartile rankings of three-fifths of the countries differ when ranked by excess vs. official mortality. Countries that are ‘doing substantially better’ in the excess mortality are characterized by higher urban population shares; higher GDP/Capita; and higher scores on institutional and policy variables. We perform two regressions in which the ratio of Cumulative Excess to Official Covid-19 mortalities (E/O ratio) is regressed on covariates. In a narrow study, controlling for GDP/Capita and vaccination rates, by December 2021 the E/O ratio was smaller in countries with higher vaccination rates. In a broad study, adding institutional and policy variables, the E/O ratio was smaller in countries with higher degree of voice and accountability. The arrival of vaccines in 2021 and voice and accountability had a discernible association on the E/O ratio.

Keywords: Voice and accountability, Official mortality, Excess mortality, Vaccines

Data availability

Interested readers can find a GitHub repository with the paper's raw data, source code, and analysis at: https://github.com/snairdesai/COVIDMortalities.

1. Introduction

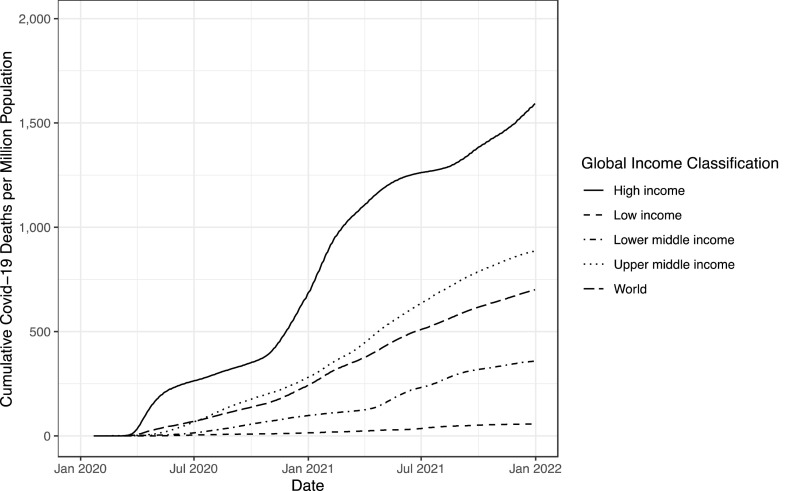

As a benchmark, the paper opens by documenting the remarkable heterogeneity of countries' Covid-19 mortality experiences during the first two Covid-19 years, from 2020 to 2021. The heterogeneity in countries’ performance is illustrated by Fig. 1 below, which displays cumulative official Covid-19 deaths per million for high-, upper-middle, lower-middle, and low-income countries, as well as for the World overall.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative official Covid-19 deaths per million, high-, upper-middle, lower-middle, low-income countries, and the World, 2020–2021. Authors' analysis of data from Our World in Data.1

At first glance, one may conclude that higher-income countries experienced a much worse pandemic. However, recent literature suggests that officially reported mortality may not reflect the true distribution of death tolls, since the limitations of official statistics and data infrastructures vary across the globe.2 Countries have different levels of reporting and testing availability, or disparate definitions of ‘Covid-19’ deaths. This is due to different abilities of medical systems to capture the diversity of Covid-19 deaths and, in some cases, even intentional under-reporting.3

The standard method of tracking changes in total mortality is “excess mortality” due to unusual circumstances such as the pandemic. Excess mortality is the gap between how many people died in a country during a given time period, regardless of cause, and how many deaths would have been expected if the pandemic had not occurred.4 To gain further insight on data limitations associated with confirmed (i.e., officially reported) Covid-19 counts, we evaluate the quartile ranking of countries using both official and excess Covid-19 mortality data. Contrasting countries’ ranking using these two data sources reveals sharp and systematic contrasts in mortality statistics. In particular, while higher GDP per capita is associated with a worse mortality ranking (i.e., a quartile with higher mortality) using the official Covid-19 mortality data, we find the opposite result in the excess mortality data — higher GDP per capita is associated with a better mortality ranking (i.e., a quartile with lower mortality).

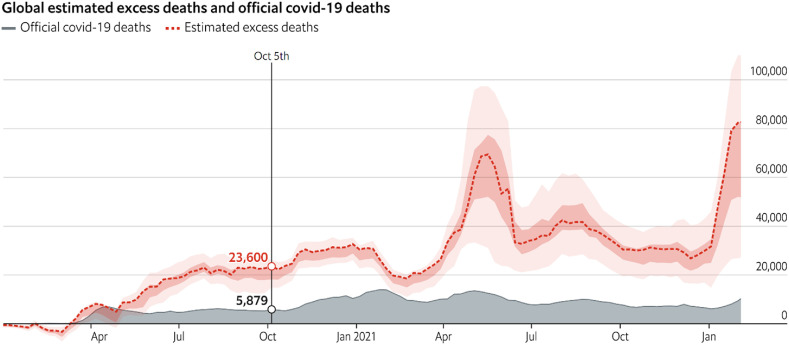

Fig. 2 plots the world excess and the official Covid-19 deaths during the first two Covid-19 years (2020–2021). It clearly illustrates the higher mean and standard deviation of excess deaths in comparison to officially reported deaths.

Fig. 2.

Global estimated excess deaths and official Covid-19 deaths, January 2020–February 2022.

Source: The Economist. February 4th, 2022.

Yet despite the clear evidence of gaps between official and excess mortality metrics (which might be expected given their disparate calculations), there is no consensus around the extent to which these metrics differed, especially in the context of a global setting over an extended period of the pandemic. Vandoros (2020) examined excess mortality during the initial phase of the virus in England and Wales, using historical data from the UK Office of National Statistics. Using a difference-in-difference estimation technique where the treatment period began with the first officially reported Covid death, Vandoros found there were nearly 1000 additional weekly deaths which were not officially reported as Covid-related over the first few months of 2020, as compared to a historical baseline average from 2015 - 2019.5

Gibertoni et al. (2021) compared official and excess deaths across a more expansive sample of 67 countries from the start of the pandemic until the end of 2020, using Covid data collated from Our World in Data (OWID), and historical data from the World Mortality Data. The authors use a set of negative binomial regressions to estimate projected deaths in 2020 using their historical baseline period (2015–2019). These estimates are then compared to actual deaths reported by OWID. They find most countries in the sample had higher than expected deaths in 2020, even after accounting for Covid-related deaths. The authors further classify these countries into two distinct groups: those with large gaps between excess and official deaths (largely Latin American and Eastern European countries), and those with more moderate gaps (a much more heterogenous group of countries). Countries with negative excess deaths also tended to have low official mortalities (with a large majority located in East Asia), and national testing capacity was associated with the extent of gaps between official and excess deaths.6 Rivera et al. (2020) extend their analysis to include not only excess all-cause mortalities, but also influenza and pneumonia mortalities in the first phase of the pandemic within the US. When compared to a historical baseline period from 2015 to 2020, the authors find evidence of greater excess mortality from Covid-19 nationally, and in nine states in particular. They also report large gaps in excess deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza across the US sample. The authors conclude that official US mortality reporting in the early phase of the pandemic substantially understaded actual mortality – and note that excess mortalities are not attributable to Covid-19 alone, but that other causes are also at play.

To gain further insight on these questions, we perform two sets of regressions, in which the ratio of Cumulative Excess to Official Covid-19 mortalities (E/O ratio) is regressed on a large set of covariates. We focus on more than 140 countries with cumulative excess mortality usually higher than official mortality, and run our analysis both at the end of 2020 and at the end of 2021. Thus, our sample and timeframe are much richer than prior studies. In the first, narrow study, we control only for GDP/Capita and vaccination rates. In the second, broad study, we add other institutional and policy variables. In the narrow study we find that by December 2021, Cumulative Excess/Official Covid-19 mortality ratios are smaller for countries with higher vaccination rates. In the broad study — both at the end of 2020 and at the end of 2021 — a higher urban population share and a higher score on voice and accountability are associated with lower Cumulative Excess/Official Covid-19 mortality ratios, but the vaccination variable at the end of 2021 becomes insignificant — probably due to multicollinearity with the other controls.

We close our analysis by contrasting the quartile rankings between the two data sets at the end of 2021. For 3/5ths of the countries in our sample, quartile rankings differ by 2 between the two data sets (e.g., a nation will have a quartile ranking of 3 based on the official mortality data, but a ranking of 1 based on the excess mortality data). We also contrast countries that are ranked substantially better to countries that are ranked substantially worse, based on their excess mortality as compared to their official Covid-19 mortality count. We classify countries that are “doing substantially better in excess” as any nation in the sample that recorded a ranking of at least two quartiles better (i.e., ranked in a lower mortality quartile) when using excess mortalities, as opposed to official mortalities. Conversely, we categorize countries that are “doing substantially worse in excess” as any nation in the sample which recorded a quartile ranking of at least two worse (i.e., higher mortality) when using excess mortalities, as opposed to official mortalities. On average, the countries which are ‘doing substantially better in excess’ are characterized by higher urban population share; higher GDP/Capita; better rule of law, voice accountability, and government effectiveness; and substantially higher vaccination rates.

These results suggest that one should take official Covid-19 mortality counts with a grain of salt, and should supplement this information with excess mortality data. We also find that governance indicators, in particular, voice and accountability, and other structural variables (such as urban population share) may explain the ranking gaps between the two data sets (Kaufmann et al., 2011). In addition, our results provide corroboratory evidence from excess deaths, notably that the officially reported Covid-19 mortality counts have undercounted true Covid-19 deaths for most countries. We also find some evidence, though less powerful, that older population demographics have registered higher mortalities; and low-income countries have had a worse experience with the pandemic (Economist (2022b); Knutson et al. (2022)). The arrival of vaccines in early 2021 was also correlated with the gap between excess and official mortality — the strength of this relationship likely varied by country. Notably, the heterogeneous impact of vaccines may also reflect the global shortages of vaccinations, resulting in unequal worldwide vaccination rates.

2. Data

Our full dataset is constructed by supplementing the Our World in Data database on Covid-19 with a few other datasets, including the World Development Indicator (WDI) database, the World Governance Indicator (WGI) database (Kraay and Mastruzzi, 2011), a global panel database of pandemic policies (Hale et al., 2021), and the Economist's tracker for Covid-19 excess deaths. The full dataset covers 170 countries at a weekly frequency from January 1, 2020, to December 31, 2021.

Specifically, from the Our World in Data's Covid-19 database, we use cumulative officially reported Covid-19 mortality counts (per million population), the total number of Covid-19 vaccination doses administered per 100 people in the total population (Mathieu et al., 2021), population density, the share of individuals older than 65, and GDP per capita.

We use the share of urban population from the WDI database; and rule of law, voice and accountability, and government effectiveness from the WGI database. Rule of law captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence. The voice-and-accountability variable captures perceptions of the extent to which a country's citizens can participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and free press. Lastly, government effectiveness captures perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government's commitment to such policies.7

We also use cumulative excess mortality per million population from the Economist's tracker for Covid-19 excess deaths, which is calculated by comparing all-cause mortality in a given country and time frame with a historical baseline from prior years. A linear trend is then fit for the year, accounting for long-term increases or decreases in mortality, and a fixed effect is implemented for each week or month up to February 2020 to account for short-term fluctuations.

3. Quartile evidence contrasting official versus excess cumulative Covid-19 Mortality, 2020–2021

We start by tabulating the quartile rank order of mortality per million during the first two Covid-19 years (from the beginning of 2020 to the end of 2021) using the two mortality measures, i.e., the official (or reported) mortality and the excess mortality. Next, we describe the large discrepancies of countries’ ranking between the two mortality measures. To gain further insight, we present regressions accounting for these differences, and close with discussion and interpretations.

Table 1 reports the average statistics of countries in quartiles of cumulative official Covid-19 mortality per million up to December 31, 2021. Table 2 replicates Table 1, but for excess Covid-19 mortalities. Table 1A, relegated to the appendix, reports the country list within each quartile of official mortality. Table 2A (also in the Appendix) replicates Table 1A, but for excess mortality data. We order the ranks of the quartiles so that a lower quartile consists of countries with lower cumulative mortalities.

Table 1.

Average quartiles statistics of cumulative official Covid-19 mortality, December 31, 2021.

| Variable | 1st Quartile (Lowest Cum. Mortality) | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile (Highest Cum. Mortality) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 58,162,373 | 68,463,139 | 12,154,505 | 33,903,606 |

| Population Density | 239 | 399.2 | 229.8 | 104.6 |

| Urban Population Share | 44 | 56.3 | 66 | 69 |

| Aged 65+ Population Share | 4.5 | 6.5 | 9.5 | 13.9 |

| GDP per Capita (in $1000) | 7.2 | 20.5 | 25 | 22.3 |

| Rule of Law | −0.6 | −0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Voice and Accountability | −0.6 | −0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Government Effectiveness | −0.7 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Vaccinations | 33.9 | 87.9 | 103.3 | 117.5 |

Notes: Each row in Table 1, Table 2 captures average demographic indicators within each quartile. Population is calculated as cumulative totals as reported by the United Nations in 2020; population density is calculated as the number of people divided by total land area measured in square kilometers; and gross domestic product is calculated at purchasing power parity (constant 2011 international dollars) – all from Our World in Data. Rule of Law, Voice and Accountability, and Government Effectiveness are ranked on a scale of −1 to 1 (with 1 representing a higher country score), and were pulled from the Worldwide Governance Indicators. Vaccinations is the number of Covid-19 vaccines administered per hundred population (also pulled from OWID).

Table 2.

Average statistics of excess mortality/millions of countries in quartile, December 31, 2021.

| Variable | 1st Quartile (Lowest Cum. Mortality) | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile (Highest Cum. Mortality) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 40,485,718 | 25,673,282 | 26,800,349 | 69,443,370 |

| Population Density | 491.1 | 242.5 | 114.3 | 122.3 |

| Urban Population Share | 62.3 | 52.1 | 57.8 | 62.8 |

| Aged 65+ Population Share | 8.4 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 10.9 |

| GDP per Capita (in $1000) | 24.4 | 16.5 | 15.6 | 17.1 |

| Rule of Law | 0.4 | −0.1 | −0.3 | −0.2 |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.3 | −0.2 | −0.3 | 0 |

| Government Effectiveness | 0.3 | −0.2 | −0.2 | −0.1 |

| Vaccinations | 95.8 | 79.2 | 74 | 87.1 |

Contrasting the average statistics in each quartile of cumulative official Covid-19 mortality per million up to December 2021 (Table 1) with those in the same quartiles of cumulative excess mortality per million in December 2021 (Table 2) reveals intriguing fundamental differences between these two mortality measures and the resulting country quartile rankings.

Table 1 indicates that, on average, higher GDP/capita countries performed poorly relative to low- and middle-income countries in terms of their cumulative official Covid-19 mortality ranking. The best-performing official mortality quartile's average income/capita is the lowest (about $7200) of all quartiles, only 1/3 of that of the higher mortality quartiles. Similar observations apply to measures of institutional quality. Rule of law, voice and accountability, and government effectiveness are significantly higher and positive for the worst-performing quartiles (e.g., the third and fourth quartiles).

Intriguingly, almost the opposite patterns characterize the quartiles of cumulative excess mortality, reported in Table 2. The lowest excess mortality quartile's average income/capita is the highest (about $24,400) of all quartiles. Average income/capita in the worst excess mortality quartile is only 3/5 of the average income/capita of the best performing quartile. The quartile with the lowest excess mortality is now characterized by the highest rule of law, voice and accountability, and government effectiveness scores.

These observations raise fundamental concerns about the quality of confirmed (or official) cumulative mortality data in Covid-19 times. It also challenges simplistic interpretations and generalizations, like the notion that on average, OECD countries failed in dealing with Covid-19 challenges relative to low- and middle-income countries. This view is supported by the quartiles’ average statistics when measured using official Covid-19 mortality, but is mostly rejected when measured using excess mortality data. The sharp contrast between the two tables suggests that countries which ranked higher in terms of rule of law, voice, accountability, and government effectiveness are also countries where the (mainly positive) gap between the official Covid-19 mortality and the excess mortality is smallest.

4. Statistical analysis of the gap between official and excess cumulative Covid-19 mortality, 2020–2021

To obtain further insight on the gap between official and excess cumulative Covid-19 mortality, we run regressions accounting for the ratio of Cumulative Excess/Official Covid-19 mortalities (henceforth, E/O ratio) across countries. A higher E/O ratio implies that the excess mortality is larger than official mortality, and vice versa. Because excess mortality is estimated consistently across countries, it serves as cross-country benchmark against which official mortality can be compared with in a cross-country setup. These regressions are run for two dates; at the end of 2020, and at the end of 2021. We focus on countries in which cumulative excess mortality exceeds cumulative official mortality. This is the case for the vast majority of countries. The sample includes more than 120 countries as of end-2020, and more than 140 countries as of end-2021. We use the following specification:

| (1) |

where i denotes country; t denotes the sub-samples, i.e. the excess mortality as of 12/28/2020 and 12/27/2021; X is a matrix of socioeconomic variables, including GDP per-capita, population density, urban share, age above-65 share, rule of law, voice and accountability, and government effectiveness, all referring to the pre-pandemic values of year 2019. Vaccination is the total vaccinations per hundred of the population; and c is the constant term.

Table 3 provides the estimation of the E/O ratio using a set of structural regressors, including the level of income (as measured by GDP per capita), a set of demographic variables including population density, urban population share, share of individuals above 65, and a set of variables from the World Governance Indicators database measuring the quality of governance - including rule of law, voice and accountability, and government effectiveness; as well as a Covid-19 vaccination level (as measured by the number of Covid-19 vaccinations administered per hundred population).

Table 3.

Broad regressions of cumulative excess/official Covid-19 mortality across countries with additional Controls, 2020 and 2021.

|

Dependent variable: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E/O | ||||

| As of 12/28/2020 |

As of 12/27/2021 |

|||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| GDP per Capita | −2.6829 (2.0413) | 2.0157 (4.0279) | −0.2222 (0.2809) | 0.2980 (0.3966) |

| Population Density | 0.0310 (0.0582) | am | ||

| Urban Population Share | −5.5658** (2.4446) | −0.7608*** (0.2455) | ||

| Aged 65+ Population Share | 6.1060 (9.3970) | 0.6140 (0.9260) | ||

| Rule of Law | −29.0065 (150.0266) | −3.5680 (13.7032) | ||

| Voice and Accountability | −85.4492 (79.6006) | −13.6045* (7.0166) | ||

| Government Effectiveness | 27.1762 (127.2772) | 3.6186 (12.7480) | ||

| Total Vaccinations per Hundred Population | −0.2105** (0.0813) | −0.1220 (0.0858) | ||

| Constantt |

109.6314** (50.6259) |

268.2816* (141.5579) |

38.8660*** (6.3376) |

57.1352*** (13.8960) |

| Observations | 123 | 121 | 147 | 145 |

| R2 | 0.0141 | 0.0823 | 0.1004 | 0.2013 |

| Residual Std. Error | 415.9638 | 415.1160 | 48.2743 | 44.8026 |

| F Statistic | 1.7275 | 1.4485 | 8.0318*** | 4.2836*** |

Note: *,**,*** correspond to 10%, 5% and 1% significance, respectively.

Columns (1) and (3) of Table 3 shows the regression results with only the level of income (as measured by GDP per capita) and the level of vaccination (as measured by the number of Covid-19 vaccinations administered per hundred population), as of end-2020 and end-2021 separately. Results show that, at the end of 2020 and 2021, the associations between E/O ratio and GDP per capita are both negative but statistically insignificant. In 2021, however, as Covid-19 vaccines became widely available throughout the year for a large number of countries, the association between E/O ratio and the vaccination level in the international sample is significantly negative.8

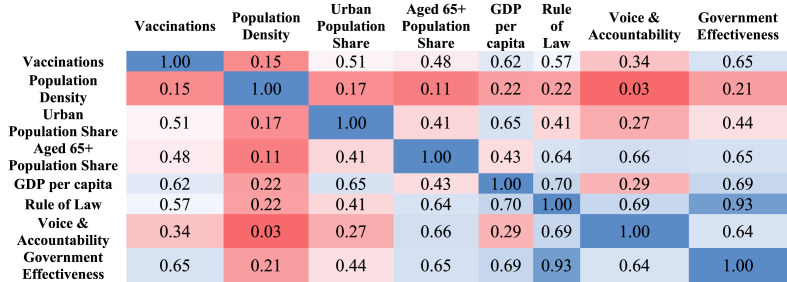

Columns (2) and (4) of Table 3 shows the regression results with the addition of more structural variables. Column (2) shows that, at the end of 2020, the association between E/O and urban population share is significantly negative while the associations with other indicators are all insignificant. At the end of 2021, as shown in column (4), in addition to the significant and negative association with urban population share, E/O ratio is significantly and negatively correlated with voice and accountability. Notably, the vaccination level that had a significantly negative impact on the E/O ratio at the end of 2021 in column (3) is now insignificant although still negative in spite of the presence of the additional variables above. It is likely that this is due to a high degree of multicollinearity between vaccinations and other controls. Table 3A in the appendix presents a correlation matrix of our core variables which appears to confirms those suspicions.

These results show that on average, countries which record higher perceptions of citizens’ ability to participate in selecting their government, and rank higher on freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media are likely to experience a smaller gap between their cumulative excess and official mortalities. One possible explanation of this result is that it would be harder for a country with higher perceptions of voice and accountability to manipulate officially reported mortality.9 Relatedly, countries with a higher urban population share would find it harder to manipulate officially reported mortality because urban populations are likely to have better access to both domestic and international information.

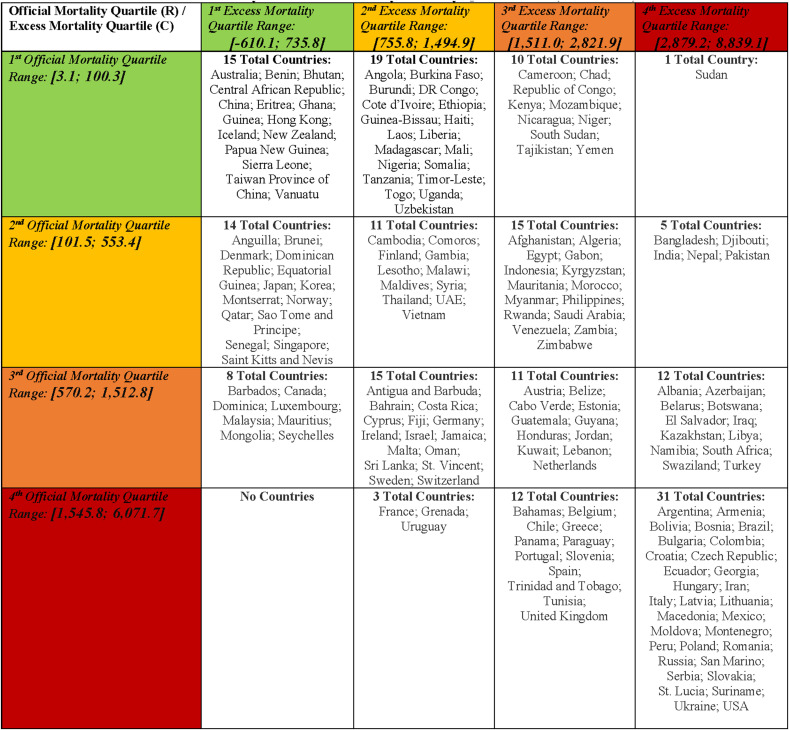

Table 4 reports country mortality quartiles as ranked by their official (or reported) Covid-19 mortality (rows) against their mortality quartiles as ranked by excess Covid-19 mortality (columns) in a 4 by 4 matrix. Based on this construction, the diagonal of this matrix reports 68 countries that are in the same mortality quartile under both the official and excess counts (i.e., Australia is ranked in the lowest mortality quartile regardless of whether this is calculated based on their official deaths or their excess deaths). These countries represent about 37% of the global sample. In contrast, the ranking of countries that are further away from the main diagonal differ more between their official and excess mortality counts. For example, Sudan is far removed from the main diagonal — ranking at the highest quartile based on excess mortality measures, but the lowest quartile based on official mortality. Other examples include France, which ranks in the 4th quartile in terms of official mortality but ranks in the 2nd quartile in terms of excess mortality or Bangladesh, which is in the 2nd quartile in terms of official mortality but is in the 4th quartile in terms of excess mortality. We proceed by focusing on these countries — and in particular the subset of countries whose rankings differ between these two metrics (official and excess) by at least two quartiles.10

Table 4.

Country official mortality quartile against excess mortality quartile (end of 2021).

Note that the mortality ranges of countries given their respective quartile rankings are quite heterogenous. For example, the net difference in the range of official Covid mortality in the first quartile is roughly 100 deaths per million (range: 3.1–100.3). However, the gap in these ranges steadily increases for higher quartiles (in the fourth quartile, the net range for official mortality is roughly 4500 deaths per-million given the range of 1545.8–6071.7). Examining quartiles based on excess mortalities, we note that the first quartile range is from minus 610 to 735, a net range of 1345 deaths per million. This range is substantially larger than the one observed for the first quartile of official Covid mortality (100 deaths per million). The net difference in the range does not strictly increase as we move to higher quartiles — however the highest excess mortality quartile has a substantially higher net value. In the fourth quartile, the net range for excess mortality is roughly 6000 deaths per million given the range of 2879–8839. In contrast, the net range for officially reported Covid mortality in the fourth quartile is roughly 4500 deaths per million, given the range of 1545–6071 deaths per million.

Possible explanations accounting for these heterogenous patterns of officially reported Covid mortality include limited and fragmented administrative and medical capacities across the countries in our sample. In some cases, it may also reflect the wish of a ‘strong-men’ regimes to minimize political criticism in countries with limited voice and accountability, and other structural obstacles inhibiting the identification and counting of Covid mortality. These factors constrain the officially reported Covid mortality, but don't necessarily bind the excess mortality statistics, which might account for some of the large mortality gaps between excess and official mortality in the higher mortality quartiles. 11

Table 5 reports the average statistics for countries that are “doing substantially worse in excess” — any country that recorded a quartile ranking at least two worse (i.e., higher mortality) when using excess mortalities as opposed to official mortalities (for example, Bangladesh) — and comparing them to countries that are “doing substantially better in excess” — any countries that recorded a quartile ranking at least two better (i.e., lower mortality) when using excess mortalities as opposed to official mortalities (for example, France). When contrasting countries that are ranked substantially better to countries that are ranked substantially worse in excess mortality as opposed to official mortality, we find that, on average, the ‘doing substantially better in excess’ countries are characterized by: higher urban population share [66% versus 38%]; older (12% versus 4% of aged 65 and older); recording a substantially higher GDP/Capita ($ 29,000 versus $ 3000); scoring better in rule of law, voice accountability, and government effectiveness; and achieving substantially higher vaccination rates (as measured by the number of Covid-19 vaccinations administered per hundred population) [144 versus 26]. 12

Table 5.

Summary statistics of “doing better in excess” deaths and “doing worse in excess” deaths.

| Variable | Mean | St. Dev. | Min. | 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doing Substantially Better in Excess Mortality | ||||||

| Population Density | 217.05 | 233.10 | 1.98 | 58.00 | 274.29 | 664.46 |

| Urban Population Share | 66.19 | 22.09 | 31.15 | 48.74 | 80.93 | 95.33 |

| Aged 65+ Population Share | 11.78 | 5.12 | 4.03 | 7.63 | 14.88 | 19.72 |

| GDP per Capita (in $1000) | 29.37 | 24.06 | 9.67 | 15.29 | 32.71 | 94.28 |

| Rule of Law | 0.76 | 0.63 | −0.26 | 0.32 | 1.13 | 1.79 |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.86 | 0.51 | −0.15 | 0.57 | 1.22 | 1.50 |

| Government Effectiveness | 0.71 | 0.72 | −0.34 | 0.21 | 1.15 | 1.84 |

| Vaccinations per Hundred Population | 144.22 | 47.41 | 66.10 | 102.78 | 178.83 | 199.36 |

| Doing Substantially Worse in Excess Mortality | ||||||

| Population Density | 175.31 | 324.43 | 11.83 | 30.49 | 145.88 | 1265.04 |

| Urban Population Share | 37.95 | 17.91 | 16.43 | 26.04 | 41.59 | 77.78 |

| Aged 65+ Population Share | 3.87 | 1.17 | 2.49 | 3.10 | 4.65 | 5.99 |

| GDP per Capita (in $1000) | 3.18 | 1.65 | 0.93 | 1.72 | 4.57 | 6.43 |

| Rule of Law | −0.98 | 0.49 | −1.93 | −1.22 | −0.57 | −0.02 |

| Voice and Accountability | −1.02 | 0.61 | −1.83 | −1.42 | −0.58 | 0.15 |

| Government Effectiveness | −0.98 | 0.70 | −2.34 | −1.44 | −0.66 | 0.39 |

| Vaccinations per Hundred Population | 26.35 | 33.65 | 0.00 | 1.72 | 47.34 | 101.80 |

Note: “Doing Substantially Better in Excess” is the sample of countries that recorded a ranking at least two better quartiles (i.e., quartiles with lower cumulative mortality) when using excess rather than official mortalities, and “Doing Substantially Worse in Excess” is the sample of countries which recorded a ranking of at least two worse quartiles (i.e., quartiles with higher cumulative mortality) when using excess rather than official mortalities.

These gaps support the view that better governance scores account for the countries with the largest gaps between excess and official mortality. Notably, these characteristics are also associated with higher GDP/Capita, older populations, and (in some studies) with sufficiently high vaccination levels. The overall positive correlations between these variables, reported in Table 3A (see the Appendix), suggests that without more granular data, ranking of the relative importance of these factors is not feasible.

5. Concluding remarks

As the Covid-19 pandemic has caused significant death tolls globally, cross-country analyses and global comparisons have been widely conducted to investigate Covid-19 mortality across many dimensions (i.e., economic, political, social, etc.). With most of these studies relying on official statistics on Covid-19 mortality as reported by countries, the quality of the underlying official mortality statistics plays a critical role in shaping the results obtained. Importantly, there are widely documented limitations in the official mortality statistics that mask the ranking of countries in terms of life preservation. Some of these limitations include differences in countries’ capacities to test for Covid-19, determine the cause of death, and disparate definitions of death.

To investigate the limitations of official Covid-19 mortality, we contrast this measure with excess mortality, which is calculated as the difference of all-cause mortality during the Covid-19 pandemic from a baseline trend modeled from historical mortality data. We show that countries' quartile rankings differ quite substantially between excess and official cumulative mortalities. Countries who fare the best in terms of cumulative excess mortality record the highest income and institutional quality (as measured by rule of law, voice and accountability, government effectiveness). This evidence is further supported by a simple regression analysis of the ratio of excess to official mortality on country-specific indicators as well as a deeper examination of individual country's quartile movements between measures of official and excess mortality. Specifically, governance variables, in particular, voice and accountability, other structural variables (such as urban population share) explain the ranking gaps between the two data sets.

These results suggest that one should take the official Covid-19 mortality counting with some skepticism and that it should be supplemented by excess mortality data. 13 However, it should be noted that excess mortality data is subject to limitations that may affect its quality as well. Not all excess mortality is due to covid-19. There might be a reduction in other deaths, due to the pandemic, which might lead to an underestimate of excess mortality. More generally mortality not directly attributable to the Covid-19 virus might have increased or decreased as a result of the pandemic. Tanaka and Okamoto (2021) find that during the first five months of the pandemic the suicide rate in Japan decreased and subsequently increased. For Greece, Vandoros (2022) finds that, due to reduced mobility during Covid-19 lockdowns deaths due to car accidents decreased. Estimates by Chen et al. (2020) for China suggest that early interventions to contain the Covid-19 outbreak led to improvements in air quality that brought health benefits in non-Covid-19 deaths, which could potentially have outnumbered the confirmed deaths attributable to Covid-19 in China (4633 official deaths as of May 4, 2020). Maringe et al. (2020) provide evidence suggesting that substantial increases in the number of avoidable cancer deaths in England are to be expected as a result of diagnostic delays due to the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK.

On the other hand some limitations of the official mortality statistics have been mitigated, and therefore, the results in this paper may not solely be attributed to the quality of official mortality statistics (see Whittaker et al., 2021; Helleringer and Queiroz, 2021). 14 Notably, the growing importance of GDP/Capita and vaccination rates in explaining the cross-country variation of the cumulative excess/official Covid-19 death ratios at the end of 2021. Novel literature has covered the gains from vaccination in terms of reducing all-cause and Covid-specific mortality quite thoroughly, and the findings mirror our paper's results (see Watson et al., 2022; Zhong et al., 2022). These findings both align with and motivate concerns of the World Health Organization about the global shortages of vaccinations, resulting in unequal worldwide vaccination rates.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, to maximize the sample size, we rely on the mid-point estimates of excess deaths, whose upper and lower bounds vary with the underlying data and models (see Adam (2022) for comparisons). Secondly, our estimation focuses on contrasting Covid-19 excess and official deaths and their linear associations with several controls in a non-experimental setting. Thirdly, cross country variations in the effectiveness of vaccines and in the variants of concern, both of which have evolved with the pandemic's path, are nuances in the relationships of the variables studied that we abstracted from. Due to current data limitations, they are currently beyond the scope of our analysis.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

For OWID data, see: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cumulative-covid-deaths-region.

We are grateful for the detailed comments of anonymous referees and the Editor. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, and IMF management, nor those of the Brown School of Public Health.

See Karlinsky and Kobak (2021), the Economist article “There have been 7m-13m excess deaths worldwide during the pandemic.” Mulligan (2021) concluded that in the US, excess mortality is closely related to deaths of despair -- social isolation may be part of the mechanism that turns a pandemic into a wave of deaths of despair.

Arguably, ‘strong-men’ regimes with limited voice and accountability may prefer to under-report official Covid mortality. See E Silva et al. (2020) paper on Brazil's likely intentional underreporting of official Covid mortality during 2020.

Among the world's 156 countries with at least 1 million people data on total mortality was available for just 84. To fill in these voids in estimation of excess-mortality, The Economist has built a machine-learning model, which estimates excess deaths for every country on every day since the pandemic began. It is based both on official excess-mortality data and on more than 100 other statistical indicators. The final figures use governments' official excess-death numbers whenever and wherever they are available, and the model's estimates in all other cases.

See Gibertoni et al., 2021: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/article-abstract/2781968.

For a complete description of the variables used in these analyses, along with ranges and data sources, see: https://github.com/snairdesai/COVIDMortalities/blob/main/Output%20Data/VariableDescription.xlsx.

Notably, this finding may also reflect the scarcity of quality vaccinations, and the resultant rationing.

Beyer et al. (2022) find that higher levels of development, statistical capacity, and voice and accountability are associated with more precise national accounts data.

Table 4 is based on the authors’ analysis of data from The Economist, and Data on Covid-19 by Our World in Data.

Note that Table 4 also demonstrates that the mortality ranges across all countries of excess mortality exceed those of reported Coving mortality by about 50%: the excess mortality net range is 9439 per million deaths [-600 – 8839] versus the reported Covid mortality net range of 6068 [3–6071]. Notably, the negative excess mortality observed in several countries during the first two pandemic years was below the usual level, possibly due to social distancing measures also jointly decreasing non-Covid infectious mortality (i.e, from the flu), and the ability of some Island Economies to insulate by sharply cutting tourism and enforcing strict quarantine periods for incoming arrivals (e.g. Australia, New Zealand and several other countries).

The positive association of the share of aged 65 plus with ‘doing better’ may reflect higher life expectancy in countries where the older population affords retirement and greater isolation, and higher vaccination rates by the end of 2021.

The imprecision of official statistics is due to a number of reasons. First, the infrastructure needed and capacity to register and report all deaths varies across countries. Second, there are delays in death reporting that make mortality data provisional and incomplete. The extent of the delay and counting capacity varies by country. See Aron et al. (2020) and Adam (2022).

The precision of official COVID-19 mortality statistics is subject to how well-resourced the medical system is, which tends to vary across countries and is likely to improve with learning-by-doing and the mobilization of public resources to the system. Challenges to the official mortality statistics include whether COVID-19 was the cause of death. Such determination is subject to the quality of, among other, to the medical-examiner system and the coroner system. More generally, countries have different systems of issuing death certificates, that involve technocrats, elected officials, and physicians. In the case of COVID-19, the quality of autopsies matters greatly as symptoms of acute respiratory distress inflammatory responses signaling a viral infection needs to be sorted into COVID-19 induced deaths and deaths due to other reasons. See also The Economist (2022a).

Appendix.

Table 1A.

Country List of Quartiles of Cumulative Official Covid-19 Mortality, December 31, 2021

| 1st Quartile (Lowest Cum. Mortality) Range = [3.1, 100.3] |

2nd Quartile Range = [101.5, 553.4] |

3rd Quartile Range = [570.2, 1512.8] |

4th Quartile (Highest Cum. Mortality) Range = [1545.8, 6071.7] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burundi | Rwanda | Kuwait | Iran |

| Vanuatu | Korea | Belarus | St. Lucia |

| China | Senegal | El Salvador | Bolivia |

| Bhutan | Malawi | Iraq | Panama |

| New Zealand | Equatorial Guinea | Mauritius | Uruguay |

| Chad | Gabon | Mongolia | Grenada |

| Niger | Pakistan | Dominica | Bahamas, The |

| South Sudan | Gambia, The | Cabo Verde | France |

| Tanzania | Algeria | Sri Lanka | Serbia |

| Tajikistan | Japan | Cyprus | Portugal |

| Benin | Singapore | St. Vincent and the Grenadines | Ecuador |

| Congo, Democratic Republic of the | Syria | Fiji | Spain |

| Nigeria | Bangladesh | Oman | Greece |

| Burkina Faso | Comoros | Canada | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Sierra Leone | Cambodia | Bahrain | Suriname |

| Eritrea | Mauritania | Azerbaijan | Chile |

| Central African Republic | Afghanistan | Libya | Russia |

| Côte d'Ivoire | Venezuela | Jamaica | Tunisia |

| Hong Kong SAR | Djibouti | Guatemala | United Kingdom |

| Guinea | Zambia | Israel | Italy |

| Togo | Montserrat | Barbados | Mexico |

| Mali | Egypt | Malta | Paraguay |

| Nicaragua | Qatar | Malaysia | Ukraine |

| Taiwan Province of China | United Arab Emirates | Kazakhstan | Moldova |

| Madagascar | Brunei Darussalam | Turkey | Latvia |

| Ghana | Norway | Botswana | Belgium |

| Uzbekistan | Saudi Arabia | Honduras | United States |

| Lao P.D.R. | São Tomé and Príncipe | Swaziland | Poland |

| Angola | Finland | Albania | Colombia |

| Liberia | Lesotho | Ireland | Argentina |

| Ethiopia | Thailand | Antigua and Barbuda | Slovenia |

| Mozambique | Vietnam | Netherlands | Armenia |

| Papua New Guinea | Zimbabwe | Jordan | Lithuania |

| Congo, Republic of | Anguilla | Germany | San Marino |

| Yemen | India | Seychelles | Brazil |

| Haiti | Myanmar | Guyana | Slovak Republic |

| Cameroon | Dominican Republic | Lebanon | Croatia |

| Uganda | Nepal | Switzerland | Romania |

| Sudan | Morocco | Namibia | Czech Republic |

| Guinea-Bissau | Kyrgyz Republic | Costa Rica | Georgia |

| Somalia | Philippines | Luxembourg | Macedonia, FYR |

| Australia | Maldives | Estonia | Montenegro, Rep. of |

| Timor-Leste | Indonesia | Belize | Hungary |

| Kenya | St. Kitts and Nevis | Sweden | Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Iceland | Denmark | Austria | Bulgaria |

| NA | NA | South Africa | Peru |

Table 2A.

Country List of Quartiles of Cumulative Excess Mortality/Millions of Countries, December 31, 2021

| 1st Quartile (Lowest Cum. Mortality) Range = [-610.1, 735.8] |

2nd Quartile Range = [755.8, 1494.9] |

3rd Quartile Range = [1511.0, 2821.9] |

4th Quartile (Highest Cum. Mortality) Range = [2879.2, 8839.1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palau | Ireland | Cameroon | Bangladesh |

| New Zealand | Cyprus | Tajikistan | United States |

| Australia | Antigua and Barbuda | Afghanistan | St. Lucia |

| Kiribati | Syria | Kenya | Iran |

| Marshall Islands | St. Vincent and the Grenadines | Mozambique | Suriname |

| Nauru | Côte d'Ivoire | Zambia | Argentina |

| Tonga | Finland | Morocco | Italy |

| Eritrea | Oman | Rwanda | Colombia |

| Vanuatu | Fiji | Yemen | Brazil |

| Samoa | Cambodia | Congo, Republic of | El Salvador |

| Papua New Guinea | Israel | Kuwait | Libya |

| Taiwan Province of China | Grenada | Gabon | Botswana |

| Solomon Islands | Thailand | Panama | Nepal |

| Seychelles | Nigeria | Mauritania | Pakistan |

| Iceland | Uruguay | Algeria | India |

| Montserrat | Tanzania | Austria | Namibia |

| Korea | Malta | Venezuela | Ecuador |

| Central African Republic | Jamaica | Belize | Turkey |

| Japan | United Arab Emirates | Niger | Azerbaijan |

| Singapore | Liberia | Netherlands | San Marino |

| Bhutan | Gambia, The | Chile | South Africa |

| St. Kitts and Nevis | Togo | Bahamas, The | Czech Republic |

| Barbados | Comoros | Belgium | Latvia |

| Anguilla | Uzbekistan | Lebanon | Hungary |

| Turkmenistan | Angola | Kyrgyz Republic | Moldova |

| Tuvalu | Madagascar | Jordan | Kazakhstan |

| Hong Kong SAR | Mali | Philippines | Bolivia |

| China | Guinea-Bissau | United Kingdom | Swaziland |

| Qatar | Uganda | Cabo Verde | Poland |

| Sierra Leone | Sweden | South Sudan | Ukraine |

| Equatorial Guinea | Malawi | Myanmar | Croatia |

| Malaysia | Haiti | Saudi Arabia | Mexico |

| Mongolia | Timor-Leste | Greece | Armenia |

| Norway | Maldives | Portugal | Albania |

| Mauritius | Lesotho | Nicaragua | Slovak Republic |

| Brunei Darussalam | Congo, Democratic Republic of the | Spain | Georgia |

| Benin | Lao P.D.R. | Tunisia | Montenegro, Rep. of |

| Micronesia | Germany | Trinidad and Tobago | Djibouti |

| Denmark | Costa Rica | Guatemala | Romania |

| Dominican Republic | Ethiopia | Chad | Sudan |

| Luxembourg | France | Indonesia | Peru |

| Dominica | Somalia | Paraguay | Iraq |

| Canada | Burkina Faso | Guyana | Belarus |

| Senegal | Burundi | Zimbabwe | Lithuania |

| Ghana | Sri Lanka | Slovenia | Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Guinea | Bahrain | Honduras | Macedonia, FYR |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | Switzerland | Estonia | Russia |

| NA | Vietnam | Egypt | Serbia |

| NA | NA | NA | Bulgaria |

Table 3A.

Correlation Matrix of Variables in the Estimation

Note: Vaccinations is the number of Covid-19 vaccinations administered per hundred population.

References

- Adam D. The pandemic's true death toll: millions more than official counts. Nature. 2022;601:312–315. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron J., Muellbauer alongside J., Giattino C., Ritchie H. Our World in Data. University of Oxford; 2020. “A pandemic primer on excess mortality statistics and their comparability across countries.” Guest post. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer R., Hu Y., Yao J. 2022. Measuring Quarterly Economic Growth from Outer Space. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Wang M., Huang C., Kinney P.L., Anastas P.T. Air pollution reduction and mortality benefit during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Lancet Planet. Health. 2020;4(6):e210–e212. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Data on Covid-19 (coronavirus) by Our World in Data https://github.com/owid/Covid-19-data/tree/master/public/data Accessed.

- Economist . 2022. Autopsies and Covid-19: America's Elected Coroners Are Too Often a Public-Health Liability - the Politics of Death. January 29th. [Google Scholar]

- Economist . June 1st.Economist's tracker for Covid-19 excess deaths; 2022. How the WHO Estimates Covid's True Death Toll.https://github.com/TheEconomist/Covid-19-excess-deaths-tracker Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- Gibertoni D., Reno C., Capodici A., Esposito F., Lenzi J., Golinelli D., Sanmarchi F. Exploring the gap between excess mortality and COVID-19 deaths in 67 countries. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., Kira B., Petherick A., Phillips T., et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) Nat. Human Behav. 2021;5(4):529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleringer S., Queiroz B.L. Measuring excess mortality due to the Covid-19 pandemic: progress and persistent challenges. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlinsky A., Kobak D. Tracking excess mortality across countries during the covid-19 pandemic with the world mortality dataset. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.69336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann D., Kraay A., Mastruzzi M. The worldwide governance indicators: methodology and analytical issues 1. Hague J. Rule Law. 2011;3(2):220–246. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson V., Aleshin-Guendel S., Karlinsky A., Msemburi W., Wakefield J. 2022. Estimating Global and Country-specific Excess Mortality during the COVID-19 Pandemic. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.09081. [Google Scholar]

- Maringe C., Spicer J., Morris M., Purushotham A., Nolte E., Sullivan R., Rachet B., Aggarwal A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu E., Ritchie H., Ortiz-Ospina E., et al. A global database of Covid-19 vaccinations. Nat. Human Behav. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan C.B. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2021. Deaths Of Despair And the Incidence Of Excess Mortality In 2020 (No. W28303) [Google Scholar]

- Rivera R., Rosenbaum J.E., Quispe W. Excess mortality in the United States during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiol. Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1017/S0950268820002617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e Silva Lena Veiga, et al. COVID-19 mortality underreporting in Brazil: analysis of data from government internet portals. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(8) doi: 10.2196/21413. The Economist. February 4th, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Okamoto S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat. Human Behav. 2021;5(2):229–238. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandoros S. Excess mortality during the covid-19 pandemic: early evidence from England and Wales. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;258 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandoros S. COVID-19, lockdowns and motor vehicle collisions: empirical evidence from Greece. Inj. Prev. 2022;28(1):81–85. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-044139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson O.J., Barnsley G., Toor J., Hogan B.A., Winskill P., Ghani A. Global impact of the first year of Covid-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker C., Walker P.G., Alhaffar M., Hamlet A., Djaafara B.A., Ghani A., et al. Under-reporting of deaths limits our understanding of true burden of Covid-19. BMJ. 2021;ume 375 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong M., Kshirsagar M., Johnston R., Dodhia R., Glazer T., Kim A., Michael D., Nair-Desai S., Tsai T.C., Friedhoff S., Lavista Ferres J.M. Estimating vaccine-preventable covid-19 deaths under counterfactual vaccination scenarios in the United States. medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.05.19.22275310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Interested readers can find a GitHub repository with the paper's raw data, source code, and analysis at: https://github.com/snairdesai/COVIDMortalities.