This cross-sectional study describes the association between chronic disease burden and patients’ adverse financial outcomes.

Key Points

Question

What is the association between chronic disease diagnoses and adverse financial outcomes among commercially insured adults?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 2 854 481 adults, the likelihood of adverse financial outcomes was substantially higher with a greater number of chronic conditions.

Meaning

Patients with chronic disease experience a significantly greater burden of adverse financial outcomes compared with healthier patients; research to understand the mechanisms behind this association is critically needed to design policies to improve financial outcomes for patients with chronic conditions.

Abstract

Importance

The bidirectional association between health and financial stability is increasingly recognized.

Objective

To describe the association between chronic disease burden and patients’ adverse financial outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study analyzed insurance claims data from January 2019 to January 2021 linked to commercial credit data in January 2021 for adults 21 years and older enrolled in a commercial preferred provider organization in Michigan.

Exposures

Thirteen common chronic conditions (cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, dementia, depression and anxiety, diabetes, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, serious mental illness, stroke, and substance use disorders).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Adjusted probability of having medical debt in collections, nonmedical debt in collections, any delinquent debt, a low credit score, or recent bankruptcy, adjusted for age group and sex. Secondary outcomes included the amount of medical, nonmedical, and total debt among individuals with nonzero debt.

Results

The study population included 2 854 481 adults (38.4% male, 43.3% female, 12.9% unknown sex, and 5.4% missing sex), 61.4% with no chronic conditions, 17.7% with 1 chronic condition, 14.8% with 2 to 3 chronic conditions, 5.4% with 4 to 6 chronic conditions, and 0.7% with 7 to 13 chronic conditions. Among the cohort, 9.6% had medical debt in collections, 8.3% had nonmedical debt in collections, 16.3% had delinquent debt, 19.3% had a low credit score, and 0.6% had recent bankruptcy. Among individuals with 0 vs 7 to 13 chronic conditions, the predicted probabilities of having any medical debt in collections (7.6% vs 32%), any nonmedical debt in collections (7.2% vs 24%), any delinquent debt (14% vs 43%), a low credit score (17% vs 47%) or recent bankruptcy (0.4% vs 1.7%) were all considerably higher for individuals with more chronic conditions and increased with each added chronic condition. Among individuals with medical debt in collections, the estimated amount increased with the number of chronic conditions ($784 for individuals with 0 conditions vs $1252 for individuals with 7-13 conditions) (all P < .001). In secondary analyses, results showed significant variation in the likelihood and amount of medical debt in collections across specific chronic conditions.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cross-sectional study of commercially insured adults linked to patient credit report outcomes shows an association between increasing burden of chronic disease and adverse financial outcomes.

Introduction

The association between financial health and physical health is bidirectional,1 and poor financial status is a known risk factor for the development of chronic disease.1,2 There is evidence that individuals with more medical debt forgo medical care at higher rates3 and have higher rates of poor physical health, psychiatric disorders, and all-cause mortality.4,5,6,7

The financial consequences of illness can also be considerable.8,9,10 Financial burden during and after illness is mediated via 2 mechanisms: the direct out-of-pocket cost of care and the indirect effects on the patient’s ability to earn income.11,12 Health insurance protects patients from bearing the full cost of their medical care, although patients with both chronic disease and acute illness often still face substantial out-of-pocket medical expenses, particularly those with commercial insurance.13,14,15 Patients have even less protection from income loss during illness, relying on a patchwork of family resources, short-term sick leave, and the US’s disaggregated social safety net. Even when eligible for social services, patients rarely recoup the income they have lost due to illness.12

Prior work has suggested that the burden of medical debt in the US is considerable and increasing over time,16 but studies have been limited by a lack of data that contain both detailed clinical diagnoses and objective financial outcomes for the same individuals across a broad range of chronic conditions.17,18 Our objective was to describe the association between chronic disease burden and patient financial outcomes using a novel data source—commercial credit data—in a large commercially insured population.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

We used medical claims data from adult enrollees in the commercial preferred provider organization (PPO) plan of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM), a large state-level insurance plan with approximately 3.5 million enrollees. The insurance claims data were accessed via the Michigan Value Collaborative (MVC), a partnership between Michigan hospitals and BCBSM. This project was reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board with a waiver of patient informed consent. The study was reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.19

The BCBSM claims include comprehensive medical and pharmaceutical claims for all enrollees in the health plan. Individuals older than 65 years were included if they remained employed, had their primary insurance through an employed spouse, or had purchased a supplementary Medicare plan (Medigap) within the BCBSM PPO network. Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare enrollees without Medigap coverage through the BCBSM PPO network were not included in the analysis. Individuals were excluded from the study cohort if they had missing or invalid personal identifiers. Full details of inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in the eAppendix and eFigure 1 in the Supplement.

Linkage to Commercial Credit Report Data

The Michigan Value Collaborative identified all individuals enrolled in the BCBSM PPO plan in January 2021 and used direct patient identifiers (patient name, address, date of birth, and Social Security number) to link them to their Experian commercial credit report data from January 2021.20 After the linkage, all personal identifiers were removed by Experian prior to delivery of the data back to MVC, who then provided our study team with a limited use data set without any direct patient identifiers. All subsequent analyses were conducted using a deidentified unique person ID created specifically for the data linkage that could not be linked back to any direct patient identifiers. The credit data include a flag for deceased status; individuals reported as deceased were excluded from the study. Small numbers of individuals in the credit data were missing a credit score, and these individuals were coded as not having a low credit score in our analysis.

Identification of Chronic Disease Diagnoses

To identify chronic disease diagnoses in the BCBSM claims data, we adapted a validated algorithm from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Chronic Conditions Warehouse (CCW) for identifying chronic disease diagnoses in Medicare claims data.21 The CCW algorithm uses several different categories of inpatient and outpatient claims, some of which were not categorizable in the BCBSM claims data, so we adapted the CCW algorithm to match the claims data categories that have been previously validated in the BCBSM data.22 Additional details regarding the algorithms used in the study are presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Because the CCW algorithms require a multiyear period of continuous enrollment, we further restricted the cohort to individuals continuously enrolled in the plan for 2 years, from January 2019 to January 2021. A set of 13 chronic conditions diagnoses were chosen to be identified for individuals in the study cohort: cancer (including breast, colorectal, prostate, lung, endometrial, and leukemias/lymphomas), congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, dementia (including Alzheimer disease and other dementias), depression and anxiety, diabetes, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, liver disease (cirrhosis and other liver conditions except viral hepatitis), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, serious mental illness (including schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders), stroke (including transient ischemic attack), and substance use disorders (including alcohol and drug use disorders). These conditions were chosen a priori to include common and clinically important medical and psychiatric chronic conditions in the US, as well as those associated with substantial personal and financial disruption.5,6,23,24

Outcome Measures, Independent Variables, and Covariates

The credit report data contain a rich set of credit outcomes, including medical debt in collections, nonmedical debt in collections, total delinquent debt, the VantageScore 4.0 credit score, and whether an individual had declared bankruptcy in the past 2 years. Medical and nonmedical debt in collections are mutually exclusive categories, while total delinquent debt includes both medical and nonmedical debt in collections, as well as all past-due debt not yet sent to collections. Institutions vary in when they send past-due debt to collections, with some waiting only 30 days to send debt to collections and others waiting up to 180 days.25 Nonmedical past-due debt or debt in collections appears on credit reports immediately. However, beginning in 2017, all the major credit agencies began imposing a 180-day waiting period before medical debt appears on an individual’s credit report.26 The VantageScore 4.0 credit score is a proprietary credit score, analogous to the FICO score,27 which ranges between 300 and 850 and reflects how likely a borrower is to repay a loan. Credit scores less than or equal to 660 are classified as low prime or subprime, at which point borrowers may be denied credit or only offered credit with higher interest rates and fees.28,29

We examined 5 binary adverse credit outcomes: the presence of any medical debt in collections, any nonmedical debt in collections, any delinquent debt, whether an individual had a low credit score, and whether an individual had declared bankruptcy in the past 2 years. We also examined average dollar amounts of medical debt in collections, nonmedical debt in collections, and all delinquent debt among individuals with nonzero amounts of debt in each category.

Our key independent variable was an individual’s number of chronic conditions, categorized as 0, 1, 2 to 3, 4 to 6, and 7 to 13 chronic conditions. These cutoffs were chosen after examining the distribution of the sum of chronic conditions in the cohort but before conducting our analysis, to ensure that all categories contained an adequate number of individuals for hypothesis testing. In secondary analyses, we also used binary variables for the presence or absence of each specific chronic condition.

Covariates in the BCBSM claims included age and sex. The BCBSM data on sex included 3 categories: male, female, and unknown, and we maintained these categories in our analyses. Both age and sex were set to missing if these values were missing or inconsistent within-person or over time.

Statistical Analysis

For continuous outcomes (medical debt in collections, nonmedical debt in collections, and total delinquent debt), we used 2-part exponential hurdle models to simultaneously estimate the adjusted probability of an individual having a given credit outcome for each chronic condition category and the adjusted conditional mean amount of debt for individuals with nonzero debt in that category. For binary outcomes (low credit score or any bankruptcy), we used logistic regression models to estimate the adjusted probability of an outcome. For all models, covariates included patient age group and sex, and standard errors were robust.

In a secondary analysis, we used 2-part exponential hurdle models to estimate the average marginal effect of each of the 13 chronic conditions on both the probability of having any medical debt in collections and the change in medical debt in collections for individuals with nonzero medical debt in collections. As above, all models used robust standard errors and were adjusted for age group and sex. All P values were from 2-sided tests, and results were significant at P < .05. All analyses were performed using Stata/MP statistical software, version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

The analytic cohort included 2 854 481 adults, of whom 1 753 599 (61.4%) had no chronic conditions, 504 319 (17.7%) had 1 chronic condition, 422 187 (14.8%) had 2 to 3 conditions, 154 099 (5.4%) had 4 to 6 conditions, and 20 277 (0.7%) had 7 to 13 conditions. The most common chronic conditions were hypertension (681 072 [23.9%]), depression/anxiety (446 224 [15.6%]), and diabetes (256 472 [9.0%]) (Table). The number of chronic conditions increased with patient age (eFigure 2 in the Supplement), and women were slightly more likely to have more chronic conditions than men (eFigure 4 in the Supplement). Overall, 274 279 (9.6%) patients in the study cohort had medical debt in collections, 237 575 (8.3%) had nonmedical debt in collections, 465 031 (16.3%) had any delinquent debt, 551 409 (19.3%) had a low credit score, and 16 263 (0.6%) had declared bankruptcy in the past 2 years. Among individuals with nonzero debt in each category, the mean (SD) amount of medical debt in collections was $975 ($2671), mean (SD) nonmedical debt in collections was $2050 ($3772), and mean (SD) total delinquent debt was $2485 ($6873) (Table).

Table. Characteristics of Commercially Insured Adults in Michigan in 2021.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total individuals | 2 854 481 (100) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1 094 776 (38.4) |

| Female | 1 236 816 (43.3) |

| Unknown | 369 456 (12.9) |

| Missing/inconsistent | 153 433 (5.4) |

| Age group, y | |

| 20-24 | 186 935 (6.6) |

| 25-34 | 342 095 (12.0) |

| 35-44 | 423 126 (14.8) |

| 45-54 | 526 128 (18.4) |

| 55-64 | 647 118 (22.7) |

| 65-74 | 382 181 (13.4) |

| ≥75 | 345 750 (12.1) |

| Missing/inconsistent | 1148 (<0.1) |

| No. of chronic conditions | |

| 0 | 1 753 599 (61.4) |

| 1 | 504 319 (17.7) |

| 2-3 | 422 187 (14.8) |

| 4-6 | 154 099 (5.4) |

| 7-13 | 20 277 (0.7) |

| Chronic conditions | |

| Cancer | 97 140 (3.4) |

| Congestive heart failure | 84 377 (3.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 202 139 (7.1) |

| Dementia | 42 496 (1.5) |

| Depression/anxiety | 446 224 (15.6) |

| Diabetes | 256 472 (9.0) |

| Hypertension | 681 072 (23.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 197 401 (6.9) |

| Liver disease | 53 360 (1.9) |

| COPD/asthma | 202 479 (7.1) |

| Serious mental illness | 9027 (0.3) |

| Stroke | 34 368 (1.2) |

| Substance use disorder | 59 564 (2.1) |

| Credit outcomes | |

| Any medical debt in collections | 274 279 (9.6) |

| Any nonmedical debt in collections | 237 575 (8.3) |

| Any delinquent debt | 465 031 (16.3) |

| Low credit score (≤660) | 551 409 (19.3) |

| Any bankruptcy (past 2 y) | 16 263 (0.6) |

| Medical debt in collections (among those with any), mean (SD), $ | 975 (2671) |

| Nonmedical debt in collections (among those with any), mean (SD), $ | 2050 (3772) |

| Total delinquent debt (among those with any), mean (SD), $ | 2485 (6873) |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

In unadjusted analyses, we found a negative association between age and adverse credit outcomes, with larger proportions of younger age groups experiencing these outcomes (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). We also found an association between adverse credit outcomes and female sex, with women slightly more likely to have adverse credit outcomes than men (eFigure 5 in the Supplement).

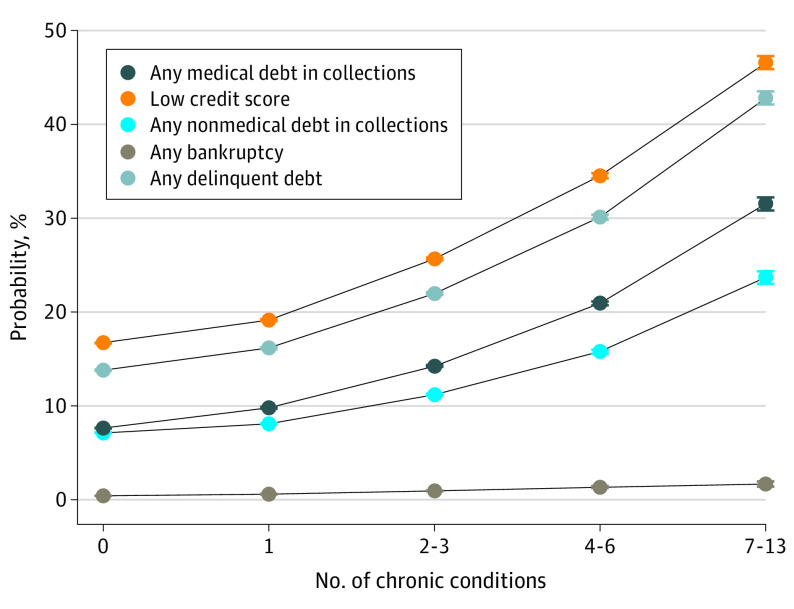

Probability of Adverse Credit Outcomes by Number of Chronic Conditions

We found increases in both adjusted and unadjusted rates of adverse credit outcomes as the number of chronic conditions increased for all credit outcomes (Figure 1; eTable 2 in the Supplement). Among individuals with 0 vs 7 to 13 chronic conditions, the estimated probabilities of having any medical debt in collections (7.7% vs 32%), any nonmedical debt in collections (7.2% vs 24%), any delinquent debt (14% vs 43%), a low credit score (17% vs 47%) or recent bankruptcy (0.4% vs 1.7%) were all considerably higher for individuals with more chronic conditions and increased with each increasing category of number of chronic conditions. All estimates for chronic condition categories greater than 0 were significantly different from 0 chronic conditions (all P < .001). Full regression estimates are available in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Predicted Probability of Credit Outcomes by Number of Chronic Conditions.

Each line reports the predicted probability of each debt outcome by the number of chronic conditions. Results are from 2-part exponential hurdle models (for medical debt in collections, nonmedical debt in collections, and any delinquent debt) and logit regression models (for low credit score and any bankruptcy). Additional covariates in all models include sex and age-band fixed effects. Standard errors are robust. All estimates for chronic condition categories greater than 0 are significantly different from 0 chronic conditions (all P < .001). Error bars indicate the 95% CI for each estimate. Full regression estimates available in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

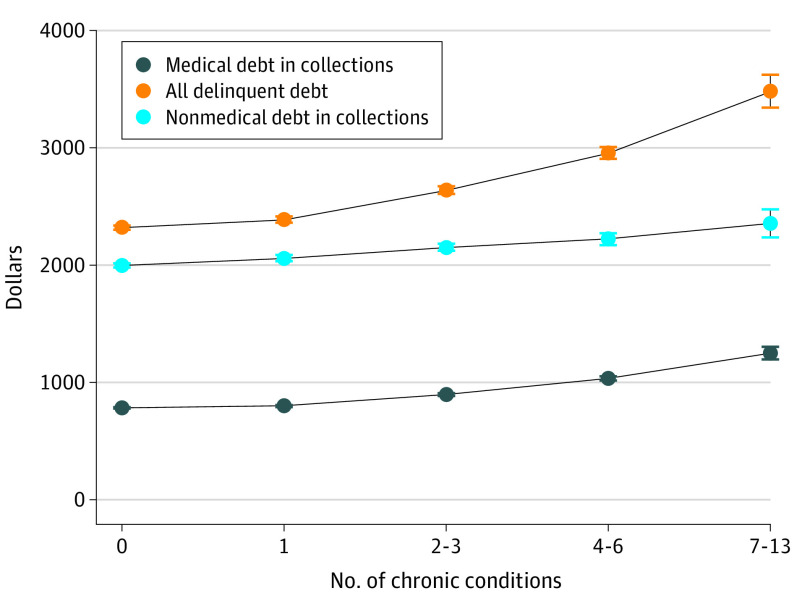

Predicted Debt Among Individuals With Nonzero Debt by Number of Chronic Conditions

For individuals with any medical debt, the adjusted amount of medical debt in collections increased with the number of chronic conditions, increasing 60% from $784 for individuals with 0 chronic conditions to $1252 for individuals with 7 to 13 chronic conditions. For individuals with nonmedical debt in collections, the adjusted amount of nonmedical debt increased by 18% from $1999 for individuals with 0 chronic conditions to $2357 for individuals with 7 to 13 chronic conditions (Figure 2). The adjusted amount of all delinquent debt, which includes medical debt in collections, increased by 50% across chronic disease burden categories from $2320 for individuals with no chronic conditions to $3483 for individuals with 7 to 13 conditions. All estimates for chronic condition categories greater than 0 are significantly different from 0 chronic conditions (all P ≤ .001). Full regression estimates are available in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Figure 2. Average Debt Among Individuals With Nonzero Debt by the Number of Chronic Conditions.

Each line reports the estimated average debt (in dollars) for each debt outcome among individuals with any nonzero debt in that category by the number of chronic conditions. Results are from 2-part exponential hurdle models; additional covariates in all models include sex and age-band fixed effects. Standard errors are robust. All estimates for chronic condition categories greater than 0 are significantly different from 0 chronic conditions (all P ≤ .001). Error bars indicate the 95% CI for each estimate. Full regression estimates available in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Probability of Medical Debt in Collections and Predicted Medical Debt in Collections by Specific Condition

All 13 conditions were associated with a significantly higher adjusted probability of having medical debt in collections compared with individuals who did not have those same conditions (Figure 3). However, there was significant variation in the additional risk of having medical debt in collections associated with each chronic condition. Serious mental illness and substance use disorders were associated with the highest increase in rates of medical debt in collections (16.1 and 15.7 percentage point increases, respectively), and cancer with the lowest (1.2 percentage point increase). Among individuals with nonzero medical debt in collections, we also found that all 13 chronic conditions were significantly associated with higher adjusted amounts of medical debt in collections (Figure 4). The chronic conditions associated with the greatest adjusted increases in medical debt in collections among individuals with any medical debt in collections were severe mental illness ($274), substance use disorders ($268), stroke ($235), congestive heart failure ($234), and liver disease ($228).

Figure 3. Estimated Increase in the Probability of Having Medical Debt in Collections by Type of Chronic Condition.

Each column reports the marginal increase in the absolute predicted probability (in percentage points) of having medical debt in collections for each chronic condition relative to not having that condition. Results are from 2-part exponential hurdle models (1 for each chronic condition); additional covariates for all models include sex and age-band fixed effects. Standard errors are robust. All point estimates are significantly different from the reference category of not having each chronic condition (P < .001). Error bars indicate the 95% CI for each estimate. CHF indicates congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure 4. Estimated Increase in Dollar Amount of Medical Debt in Collections by Type of Chronic Condition Among Individuals With Nonzero Medical Debt in Collections.

Each bar reports the marginal increase in predicted medical debt in collections (in dollars) for each chronic condition relative to not having that condition for individuals with any medical debt in collections. Results are from 2-part exponential hurdle models (1 for each chronic conditions); additional covariates for all models include sex and age-band fixed effects. Standard errors are robust. All point estimates are significantly different from the reference category of not having each chronic condition (P < .001). Error bars indicate the 95% CI for each estimate. CHF indicates congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

We found an association between chronic disease diagnoses and adverse credit report outcomes across all examined outcomes, with increasing rates of medical debt in collections, nonmedical debt in collections, total delinquent debt, low credit score, and recent bankruptcy as an individual’s number of chronic conditions increased. We also found that among individuals with any nonzero debt outcome, individuals with more chronic conditions had significantly higher dollar amounts of debt. These results have important implications for patients, as worsened financial health is associated with increased rates of forgone medical care,3,10 worse physical and mental health,4,5,6 and increased mortality.7

In addition to the stepwise association between the number of chronic conditions and adverse credit outcomes, each individual chronic condition we examined was associated with both increased rates of medical debt in collections and increased amounts of medical debt in collections among individuals with any medical debt. Rates of medical debt in collections and amounts of medical debt varied significantly across different chronic conditions. Substance use disorders, serious mental illness, congestive heart failure, dementia, and stroke were the conditions with the largest increase in the probability of having medical debt in collections. Among individuals with medical debt in collections, severe mental illness was associated with the largest increase in debt burden, followed by substance use disorders, stroke, congestive heart failure, and liver disease.

Other studies have shown that some of these conditions are associated with adverse financial outcomes4,6,30,31,32; however, we are not aware of prior studies that have directly compared financial outcomes across all of these conditions. The significant variation we found across chronic conditions suggests potentially different mechanisms for this association; some conditions may be associated with particularly costly treatments and therefore high out-of-pocket expenses, while others may be more likely to directly affect a patient’s ability to work and earn income.11

Perhaps surprisingly, in the study cohort, a cancer diagnosis conferred the smallest increase in rates of medical debt in collections and had less associated medical debt in collections than other chronic conditions we examined, despite a growing literature demonstrating adverse financial outcomes among patients with cancer.9,33,34,35,36,37,38 This finding may have been affected by the study’s inclusion criteria, as the study’s commercially insured population was younger than the overall US population and the 2-year period of continuous enrollment potentially excluded patients with cancer receiving costly end-of-life care. A limited number of survey studies have compared the risk of adverse financial outcomes specifically between cancer and heart disease and found conflicting results.39,40 Nonetheless, results of this study demonstrate that many different common chronic conditions are associated with substantial rates of adverse financial outcomes.

The study results are consistent with prior studies that have used survey data to show an association between increasing numbers of chronic conditions and increasing patient-reported out-of-pocket costs and medical debt.41,42,43 Those studies often lacked the detailed clinical diagnoses we are able to identify in claims data; lacked many of the detailed financial outcomes that we examined here, including past-due debt not yet sent to collections, low credit score, and recent bankruptcy; and lacked the statistical power to examine the association between specific chronic conditions and financial outcomes. To our knowledge, the current study is among the first to use administrative financial data linked at the individual level to examine the association between objectively measured financial outcomes and chronic disease diagnoses, and the large sample size and the unique characteristics of the data enabled us to compare multiple objective financial outcomes across a broader range of clinical conditions than has been possible in prior studies.

We cannot discern the direction of causality in the association that we find between chronic conditions and poor financial health in this analysis. Some portion of this association is likely explained by poor financial health leading to the development of additional chronic conditions, while another portion may be due to chronic disease causing additional financial burden and worsened credit outcomes. We find that both medical and nonmedical debt in collections rise with increased chronic disease burden, although medical debt in collections rises faster, suggesting that both direct costs (the out-of-pocket expense of medical care) and indirect costs (effects of illness on an individual’s ability to earn income) may have important associations with adverse financial outcomes.

Further research in this area is needed to determine the relative importance of these pathways, as the policy implications of each are different. If poor financial well-being leads to additional chronic disease, policy makers should consider new social safety-net policies to reduce poverty rates and should explicitly incorporate improvements in physical health—and correspondingly reduced health care spending—as a benefit of antipoverty programs. If, in contrast, chronic disease diagnoses are directly leading to adverse financial outcomes, then improving commercial insurance benefit design would be warranted to provide additional protection from out-of-pocket medical expenses, particularly for conditions identified as being costly for patients. In addition, policy makers should consider expanding access to disability benefits and implementing other social safety net policies to help patients recoup income loss after illness.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The study included commercially insured adults in Michigan who were continuously enrolled over a 2-year period, and it may therefore understate financial burden in other geographic regions or among individuals with unstable insurance coverage.8 The data come from a state-level commercially insured population and may not be representative of individuals insured by Medicare or Medicaid; this is supported by the fact that overall rates of medical debt in collections in the data set were slightly lower than in Michigan overall (9.6% vs 13%).44 The data also lack important individual-level covariates including income, race and ethnicity, and access to care, so we were unable to analyze the association of these covariates with financial outcomes; prior work has suggested that race and ethnicity are important predictors of medical debt.45 More generally, claims-based algorithms may not fully capture diagnoses of chronic conditions.46

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study, results showed an association between chronic disease burden and adverse financial outcomes for patients, with an increasing likelihood of multiple adverse financial outcomes and increasing debt burden as the number of chronic diagnoses increased. We also found significant variation in the likelihood and burden of medical debt across different chronic conditions. Further research into the causal mechanisms of these associations is critical to develop policies to improve financial outcomes for patients with chronic conditions.

eAppendix. Details of cohort construction

eFigure 1. Details of analytic cohort construction

eFigure 2. Number of chronic conditions by age group

eFigure 3. Credit outcomes by age group

eFigure 4. Number of chronic conditions by sex

eFigure 5. Credit outcomes by sex

eTable 1. Details of algorithms used to identify chronic conditions

eTable 2. Individuals with each credit outcome by the number of chronic conditions

eTable 3. Estimated probability of credit outcomes by chronic disease category

eTable 4. Estimated amounts of debt by number of chronic conditions among individuals with any non-zero debt

References

- 1.Khullar D, Chokshi DA. Health, income, & poverty: where we are & what could help. Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. Published October 18, 2018. Accessed July 21, 2022. doi: 10.1377/hpb20180817.901935 [DOI]

- 2.Beaglehole R, Reddy S, Leeder SR. Poverty and human development: the global implications of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1871-1873. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.736926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalousova L, Burgard SA. Debt and foregone medical care. J Health Soc Behav. 2013;54(2):204-220. doi: 10.1177/0022146513483772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweet E, Nandi A, Adam EK, McDade TW. The high price of debt: household financial debt and its impact on mental and physical health. Soc Sci Med. 2013;91:94-100. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jenkins R, Bhugra D, Bebbington P, et al. Debt, income and mental disorder in the general population. Psychol Med. 2008;38(10):1485-1493. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meltzer H, Bebbington P, Brugha T, Farrell M, Jenkins R. The relationship between personal debt and specific common mental disorders. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(1):108-113. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pool LR, Burgard SA, Needham BL, Elliott MR, Langa KM, Mendes de Leon CF. Association of a negative wealth shock with all-cause mortality in middle-aged and older adults in the United States. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1341-1350. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kluender R, Mahoney N, Wong F, Yin W. Medical debt in the US, 2009-2020. JAMA. 2021;326(3):250-256. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.8694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(2):80-81, 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Souza JA, Conti RM. Mitigating financial toxicity among US patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(6):765-766. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witte J, Mehlis K, Surmann B, et al. Methods for measuring financial toxicity after cancer diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review and its implications. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1061-1070. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobkin C, Finkelstein A, Kluender R, Notowidigdo MJ. The economic consequences of hospital admissions. Am Econ Rev. 2018;108(2):308-352. doi: 10.1257/aer.20161038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang W. Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: a ten-year trend. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(1):15-25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adrion ER, Ryan AM, Seltzer AC, Chen LM, Ayanian JZ, Nallamothu BK. Out-of-pocket spending for hospitalizations among nonelderly adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1325-1332. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moniz MH, Fendrick AM, Kolenic GE, Tilea A, Admon LK, Dalton VK. Out-of-pocket spending for maternity care among women with employer-based insurance, 2008-15. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(1):18-23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the comprehensive score for financial toxicity (COST). Cancer. 2017;123(3):476-484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fagerlin A, Sepucha KR, Couper MP, Levin CA, Singer E, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Patients’ knowledge about 9 common health conditions: the DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(5)(suppl):35S-52S. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10378700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levinger B, Benton M, Meier S. The cost of not knowing the score: self-estimated credit scores and financial outcomes. J Fam Econ Issues. 2011;32(4):566-585. doi: 10.1007/s10834-011-9273-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avery RB, Calem PS, Canner GB, Bostic RW. An overview of consumer data and credit reporting. Federal Reserve Bulletin. 2003;89(2):47-73. doi: 10.17016/bulletin.2003.89-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse . Category definitions. Accessed October 1, 2021. https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories

- 22.Ellimoottil C, Syrjamaki JD, Voit B, Guduguntla V, Miller DC, Dupree JM. Validation of a claims-based algorithm to characterize episodes of care. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(11):e382-e386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad FB, Anderson RN. The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. JAMA. 2021;325(18):1829-1830. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):263-270. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axelton K. Can Medical Bills Hurt Your Credit? Experian Blog. Published October 22, 2019. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/can-medical-bills-affect-credit-report/

- 26.Andrews M. Credit agencies to ease up on medical debt reporting. NPR. Published July 11, 2017. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/07/11/536501809/credit-agencies-to-ease-up-on-medical-debt-reporting

- 27.What is a FICO score? Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Accessed October 15, 2021. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-is-a-fico-score-en-1883/

- 28.VantageScore Solutions, LLC . VantageScore 4.0 User Guide. VantageScore Solutions, LLC; 2019.

- 29.Brown J. What is a bad credit score? Forbes Advisor. Published May 21, 2021. Accessed March 14, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/credit-score/what-is-a-bad-credit-score/

- 30.Coughlin SS, Datta B, Berman A, Hatzigeorgiou C. A cross-sectional study of financial distress in persons with multimorbidity. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23:101464. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hudson B, Hunt V, Waylen A, McCune CA, Verne J, Forbes K. The incompatibility of healthcare services and end-of-life needs in advanced liver disease: a qualitative interview study of patients and bereaved carers. Palliat Med. 2018;32(5):908-918. doi: 10.1177/0269216318756222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heo S, Lennie TA, Okoli C, Moser DK. Quality of life in patients with heart failure: ask the patients. Heart Lung. 2009;38(2):100-108. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381-390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zafar SY. Financial toxicity of cancer care: it’s time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108(5):djv370. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauer AG, Jefferson M, Nahhas GJ, et al. Financial toxicity and strain among men receiving prostate cancer care in an equal access healthcare system. Cancer Med. 2020;9(23):8765-8771. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dee EC, Nipp RD, Muralidhar V, et al. Financial worry and psychological distress among cancer survivors in the United States, 2013-2018. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(9):5523-5535. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06084-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilligan AM, Alberts DS, Roe DJ, Skrepnek GH. Death or debt? national estimates of financial toxicity in persons with newly-diagnosed cancer. Am J Med. 2018;131(10):1187-1199.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhanvadia SK, Psutka SP, Burg ML, et al. Financial toxicity among patients with prostate, bladder, and kidney cancer: a systematic review and call to action. Eur Urol Oncol. 2021;4(3):396-404. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2021.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valero-Elizondo J, Chouairi F, Khera R, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, cancer, and financial toxicity among adults in the United States. JACC CardioOncol. 2021;3(2):236-246. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2021.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones SMW, Chennupati S, Nguyen T, Fedorenko C, Ramsey SD. Comorbidity is associated with higher risk of financial burden in Medicare beneficiaries with cancer but not heart disease or diabetes. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(1):e14004. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richard P, Walker R, Alexandre P. The burden of out of pocket costs and medical debt faced by households with chronic health conditions in the United States. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu WY, Retchin SM, Seiber EE, Li Y. Income-based disparities in financial burdens of medical spending under the Affordable Care Act in families with individuals having chronic conditions. Inquiry. 2019;56:46958019871815. doi: 10.1177/0046958019871815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: the COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120(20):3245-3253. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Debt in America: an interactive map. Accessed June 28, 2022. https://apps.urban.org/features/debt-interactive-map/

- 45.Novak PJ, Ali MM, Sanmartin MX. Disparities in medical debt among US adults with serious psychological distress. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):549-555. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Details of cohort construction

eFigure 1. Details of analytic cohort construction

eFigure 2. Number of chronic conditions by age group

eFigure 3. Credit outcomes by age group

eFigure 4. Number of chronic conditions by sex

eFigure 5. Credit outcomes by sex

eTable 1. Details of algorithms used to identify chronic conditions

eTable 2. Individuals with each credit outcome by the number of chronic conditions

eTable 3. Estimated probability of credit outcomes by chronic disease category

eTable 4. Estimated amounts of debt by number of chronic conditions among individuals with any non-zero debt