Abstract

Candida auris is a fungal pathogen of high concern due to its ability to cause healthcare-associated infections and outbreaks, its resistance to antimicrobials and disinfectants and its persistence on human skin and in the inanimate environment. To inform surveillance and future mitigation strategies, we defined the extent of skin colonization and explored the microbiome associated with C. auris colonization. We collected swab specimens and clinical data at three times points between January and April 2019 from 57 residents (up to ten body sites each) of a ventilator-capable skilled nursing facility with endemic C. auris and routine chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) bathing. Integrating microbial-genomic and epidemiologic data revealed occult C. auris colonization of multiple body sites not targeted commonly for screening. High concentrations of CHG were associated with suppression of C. auris growth but not with deleterious perturbation of commensal microbes. Modeling human mycobiome dynamics provided insight into underlying alterations to the skin fungal community as a possible modifiable risk factor for acquisition and persistence of C. auris. Failure to detect the extensive, disparate niches of C. auris colonization may reduce the effectiveness of infection-prevention measures that target colonized residents, highlighting the importance of universal strate- gies to reduce C. auris transmission.

C. auris has emerged as a human pathogen of high concern due to its extensive antifungal resistance, high mortality rates associated with invasive infections and its potential to cause healthcare-associated outbreaks1–3. A recent systematic review of nearly 5,000 cases of C. auris from 33 countries reported an overall crude mortality rate of 39%4. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have declared C. auris to be an urgent public health threat, the first fungal pathogen to receive this designation5. Persistent skin colonization6 likely contributes to the epidemic potential of C. auris. Healthcare providers may contaminate their hands, gloves or clothing with C. auris by touching the skin of a colonized patient. C. auris can then be transmitted to another patient if the healthcare provider fails to perform adequate hand hygiene or adhere to other infection-prevention measures. Additionally, shedding from colonized patients’ skin into the healthcare environment, calculated to occur at a rate of a million microbes per hour7, creates an environmental reservoir and source of ongoing nosocomial transmission8–11. In the US, high-acuity long-term care facilities such as long-term acute care hospitals and ventilator-capable skilled nursing facilities have reported high prevalence of C. auris, and there is concern that these facilities may serve as drivers of regional C. auris spread2,3,12,13.

Effective infection-control measures play a central role in the management of C. auris because frequent resistance to multiple classes of antifungal agents (that is, azoles, polyenes, echinocandins) limits treatment options for invasive infection14–16. Constraining effective infection control is the paucity of published data concerning the spatial extent of skin colonization by C. auris and clarity on the relative sensitivity of different body sites to identify residents colonized with C. auris. Occult colonization has been shown to underlie transmission in recalcitrant outbreaks involving other pathogens, including Klebsiella pneumoniae17. Efficacy of the bis-biguanide antiseptic CHG in controlling C. auris colonization is another uncertainty. While CHG bathing is a common component of multimodal C. auris control programs in acute and long-term care settings, previous investigators have reported persistent colonization of residents, environmental contamination and ongoing C. auris transmission despite CHG bathing9,12,18.

C. auris was first detected in metropolitan Chicago, IL, in 2016, where post-acute care facilities have become epicenters for this pathogen3,12. Here we report on an integrated clinical research program to study C. auris colonization of residents at a ventilator-capable skilled nursing facility in Chicago with endemic C. auris and routine CHG bathing. We conducted serial point prevalence surveys of skin, oral and perianal sites to investigate C. auris using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods and analyzed the relationship of CHG concentration with growth of C. auris and the skin microbiota. Phylogenetic marker genes of bacterial and fungal communities (16S rRNA and internal transcribed spacer (ITS)1, respectively) permit high-resolution investigation into the microbiome associated with clinical samples. To understand community dynamics of C. auris skin colonization, we investigated the temporal stability and diversity of skin, oral and gut bacterial and fungal communities.

Results

Overview of study participants.

We conducted three monthly point prevalence surveys between January and April 2019 on the ventilator ward of a skilled nursing facility in Chicago, IL. At the time of each survey, research personnel collected swab specimens from up to ten body sites (anterior nares, external auditory canal, axilla, inguinal crease, perianal skin, toe web, palm and fingertips, buccal mucosa and tongue and tracheostomy site) for semiquantitative (n = 1,358) and quantitative (n = 424) C. auris culture, microbiome analysis (n = 1,358) and quantification of CHG concentration (n = 813) (Supplementary Table 1). Clinical data were collected at bedside from electronic medical records and recorded onto standardized data-collection forms. Fifty-seven (72%) of 79 unique residents on the ward during the study period participated, and, of those participating, 49 (86%) residents were found to be colonized with C. auris at one or more body site in one or more survey. Overall, residents were older adults, had a history of colonization or infection with carbapenem-resistant bacteria and had long lengths of stay before the first date of sample collection (Table 1). Residents with C. auris colonization were more likely to require an invasive medical device (for example, gastrostomy tube, mechanical ventilation) and were more likely to have received antibacterial agents in the 90 d before the first sample collection. While no participant developed C. auris clinical infection during the study period, review of clinical microbiology data from the time of admission through 6 months after the last survey identified one resident with a C. auris bloodstream infection 6 weeks before sample collection and two residents with C. auris bloodstream infections in the 6 months after the surveys concluded.

Table 1 |.

Bivariate associations of clinical characteristics with C. auris-colonization status at the time of the first survey

| Colonized (n = 46) | Not colonized (n = 11) | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Length of stay (d) between admission and first swab (M ± IQR) | 361 ± 801 | 571 ± 1,372 | 1.00 (0.99,1.00) | 0.26 |

| Age in years (mean ± s.d.) | 59 ± 14 | 59 ± 14 | 1.00 (0.95,1.05) | 0.89 |

| Female (n (%)) | 18 (39) | 5 (45) | 0.77 (0.20,2.91) | 0.74 |

| African American (n (%)) | 31 (74) | 9 (90) | 0.31 (0.066,2.76) | 0.42 |

| Mechanical ventilation (n (%)) | 23 (50) | 0 (0) | 23.00 (1.28,413.3) | 0.002 |

| Gastrostomy tube (n (%)) | 35(78) | 3 (27) | 9.33 (2.08,41.89) | 0.003 |

| Tracheostomy (n (%)) | 34 (74) | 6 (55) | 2.36 (0.61,9.17) | 0.27 |

| Urinary catheter (n (%)) | 33 (72) | 3 (27) | 6.77 (1.55,29.56) | 0.012 |

| Hospital stay within past 90d (n (%)) | 20 (44) | 3 (27) | 2.13 (0.50,9.11) | 0.5 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (M ± IQR) | 3 ± 2 | 3 ± 2 | 0.91 (0.65,1.28) | 0.59 |

| Congestive heart failure (n (%)) | 10 (22) | 5 (45) | 0.33 (0.084,1.32) | 0.11 |

| Chronic lung disease (n (%)) | 36(78) | 6 (55) | 3.00 (0.76,11.90) | 0.11 |

| Braden scale scorea (mean ± s.d.) | 13 ± 2 | 16 ± 5 | 0.74 (0.59,0.94) | 0.013 |

| History of carbapenemase- producing bacterial colonization or infectionb | 31 (67) | 6 (55) | 1.72 (0.45,6.56) | 0.49 |

| Antibacterial receipt in prior 90 d (n (%)) | 34 (74) | 5 (45) | 3.4 (0.88,13.21) | 0.030 |

| Antifungal receipt in prior 90 d (n (%)) | 5 (11) | 0 (0) | 3.05 (0.16,59.29) | 0.57 |

The Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk assesses a person’s risk of developing a pressure ulcer by examining six criteria: moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition and friction and shear.

Screening of facility residents for carbapenemase-producing bacterial colonization was performed routinely. Screening for colonization by other multidrug-resistant organisms was not performed.

CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; M, median; OR, odds ratio.

All isolates were susceptible to the commonly used antifungal agents fluconazole, amphotericin B and micafungin (Supplementary Table 2). Genomes and ITS1 sequences of C. auris isolates matched those of the South American clade IV19. Between isolates, the number of single-nucleotide variants ranged from one to 20 (mean = 14, N = 4) when reads were mapped to a nanopore reference genome generated from an isolate from this outbreak, consistent with clonality within the facility.

Patterns of body-site colonization with C. auris.

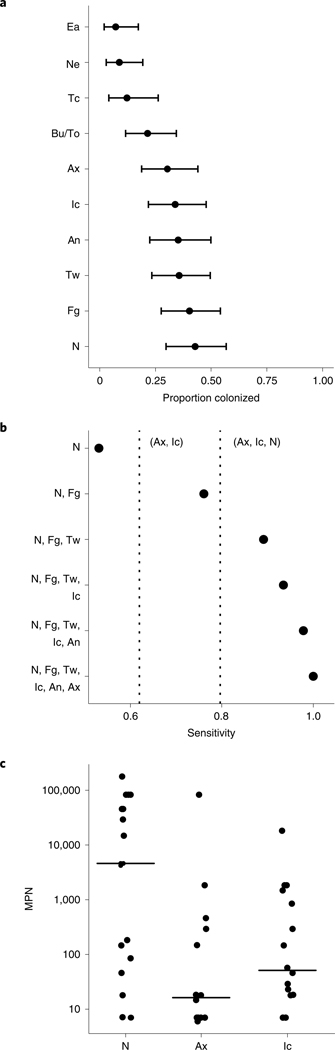

To identify the spatial extent of C. auris colonization across the human body, we surveyed ten body sites with both culturing and microbial sequencing (Extended Data Fig. 1). Patterns of body-site colonization were highly individualized (Extended Data Fig. 2). Across all study participants, the frequency of colonization varied by body site: 42.9% of residents tested positive at nares, 40.4% of residents tested positive at palms and/or fingertips, and 35.7% of residents tested positive at toe webs (Fig. 1a). Importantly, residents who were culture negative at commonly targeted screening sites (here only unilaterally sampled axilla, inguinal crease and/or nares) were frequently colonized at other body sites, such as palms and/or fingertips. Of those who were colonized, 30.4% were colonized at a single body site, with monocolonization most commonly occurring at either the anterior nares or palms and/or fingertips (Extended Data Fig. 2). C. auris never monocolonized the buccal mucosa, tongue, neck, tracheostomy site or external auditory canal.

Fig. 1 |. Screening of multiple skin, nares, perianal and oral body sites for prevalence and individual-level bioburden of C. auris colonization.

a, The proportion of residents colonized at each body site. n = 542 independent samples of each of ten body sites of each of 57 residents at the time of the first screening. Data are presented as a point estimate ±95% confidence intervals. An, perianal skin; Ax, axilla; Bu, buccal mucosa; Ea, external auditory canal; Fg, palm and/or fingertips; Ic, inguinal crease; N, anterior nares; Ne, neck; Tc, tracheostomy; To, tongue; Tw, toe web. b, Sensitivity analysis to calculate the proportion of colonized residents captured by screening different groupings of sites. Sensitivity is defined as the proportion colonized at each site grouping divided by the total number of residents identified as colonized at any body site. Dashed vertical lines correspond to the sensitivity of two routine screening strategies targeting the body sites axilla and inguinal crease (left dashed line) and axilla, inguinal crease and nares (right dashed line). A minimum of six sites was required to achieve 100% sensitivity, capturing all colonized individuals. c, Number of viable C. auris, determined by the MPN, plotted for the inguinal crease (n = 16), nares (n = 19) and axilla (n = 16). Groupwise medians are demarcated with black lines. Statistical significance of differences between sites was assessed with the Kruskal–Wallis test (P < 0.05).

Because most colonized residents (69.6%) were colonized at two or more sites, we next performed a sensitivity analysis to determine the combination of screening sites most effective at detecting the largest number of C. auris–colonized residents (Fig. 1b). Nares were the most sensitive single site, achieving 53.1% sensitivity. The most sensitive two-site combination was nares with palm and fingertips, with 76.1% sensitivity; adding toe webs increased sensitivity to 89.1%, and adding the perianal site and the inguinal crease increased sensitivity to 97.8%. Identification of all colonized residents was achieved by screening a minimum of six body sites (nares, palm and fingertips, toe webs, perianal skin, inguinal crease, axilla), consistent with the wide degree of variation observed in site-specific colonization with C. auris. The current recommended screening scheme collects a composite swab of a resident’s bilateral axillae and inguinal creases20, sometimes with the addition of anterior nares21. In our study, which was performed with unilateral sampling, these two- and three-site combinations achieved sensitivities of 61.9% and 79.7%, respectively.

As fungal load may contribute to a resident’s risk of subsequent infection or of acting as a source of transmission through contaminating the environment or a healthcare provider, we quantified the bioburden of sites screened. The most densely colonized site was the nares, which exhibited a bimodal distribution with a median peak abundance of 108.2 colony-forming units (CFU) (Extended Data Fig. 3). The axilla and inguinal crease harbored relatively low population densities: the axilla exhibited a uniform distribution with a median abundance of 103.9 CFU, while the inguinal crease exhibited a bimodal distribution with two comparable peaks and a median abundance of 104.9 CFU. Due to the semiquantitative nature of plate culture counts, quantitative analyses were performed. The median most probable number (MPN) of C. auris in nares was significantly higher than that in the axilla or inguinal crease, and nares had the greatest proportion of samples with a high bioburden (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 4). Collectively, these data suggest that multifocal colonization occurs commonly and that sites other than those screened most commonly may harbor high population densities, which may contribute to recalcitrant outbreaks experienced by some facilities.

Effectiveness of CHG against C. auris colonization.

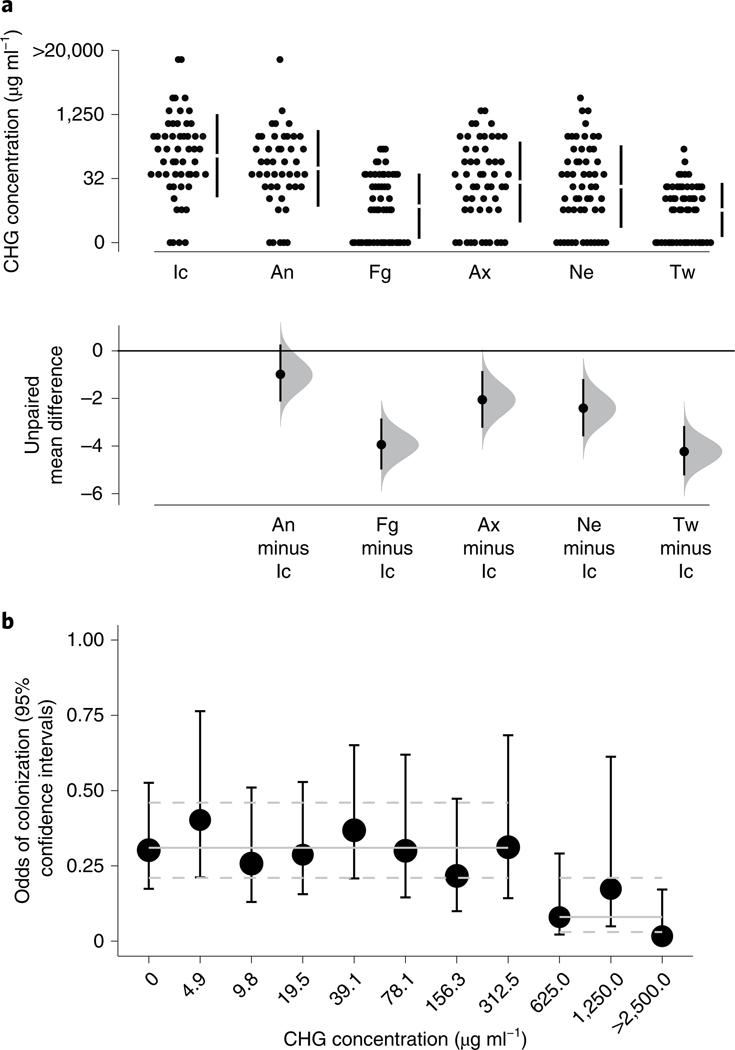

The skin antiseptic CHG is used routinely for bathing hospital residents to reduce multidrug-resistant-organism colonization and infection. Reports on the efficacy of CHG against colonization with C. auris have had mixed results9,22,23. As all residents of the ventilator-capable skilled nursing facility in the current study were undergoing routine bathing with 2% CHG-impregnated cloths, we sought to investigate the relation between CHG concentration on skin and growth of C auris in culture. Consistent with prior studies24, we found that CHG concentrations varied by body site (F(5,740) = 25.99, P < 0.001; Fig. 2a). The highest concentrations of CHG were measured at the inguinal crease (median and IQR, 78.1 and 39.1–312.5 µg ml−1), while relatively low concentrations were measured at the palm and/ or fingertips (median and IQR, 9.8 and 0–39.1 µg ml−1) and the toe web (median and IQR, 4.9 and 0–19.5 µg ml−1). As we observed that sites with the lowest CHG concentrations (palm and/or finger- tips, toe web) were colonized by C. auris at the highest frequencies (Fig. 1), we tested for an explicit association. We found evidence of a modest but not significant linear association between CHG concentration (log2 transformed) and the odds of C. auris detection (odds ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.85–1.01; P = .068). Cut-point analysis revealed a significant reduction in the odds of C. auris colonization for CHG concentrations ≥625 µg ml−1 (odds ratio, 0.27; 95% confidence interval, 0.12–0.65; P = 0.003) (Fig. 2b). Importantly, the concentration of CHG needed to reduce the odds of colonization (≥625 µg ml−1) was detected at only 7.3% of skin sites tested. Because data on the time of the most recent bath before CHG measurement were not available, we could not control for this variable. Nonetheless, we note that the concentration of 625 µg ml−1, associated with reduced odds of C. auris colonization in situ, was 20–39 times higher than the minimum concentration of CHG required to inhibit the growth of C. auris in vitro (16–32 μg ml−1) (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2 |. High concentrations of CHG are needed to reduce the odds of C. auris colonization.

a, Gardner–Altman estimation plot comparing the mean difference in CHG concentrations (µg ml−1) across body sites. Top, raw data are shown as a scatterplot of CHG concentration plotted as a function of body site for the first survey (54 residents, n = 319). Bottom, data are presented as the mean difference between CHG concentration (µg ml−1) at each body site and the inguinal crease, the site reaching the highest average CHG concentration, ±95% confidence intervals. Histograms reflect the sampling distribution from a nonparametric bootstrap. b, Each point represents the modeled odds of C. auris colonization (±95% confidence intervals) plotted against the measured skin CHG concentration (µg ml−1), adjusted for multiple measurements within resident and over time. The solid horizontal lines represent odds of colonization per respective group (that is, <625 µg ml−1 versus ≥625 µg ml−1), while the dashed lines encompass the 95% confidence interval surrounding each group estimate. Significance tests were based on the model-estimated log odds divided by the standard error, distributed as a t distribution.

Underlying microbiome associated with C. auris colonization.

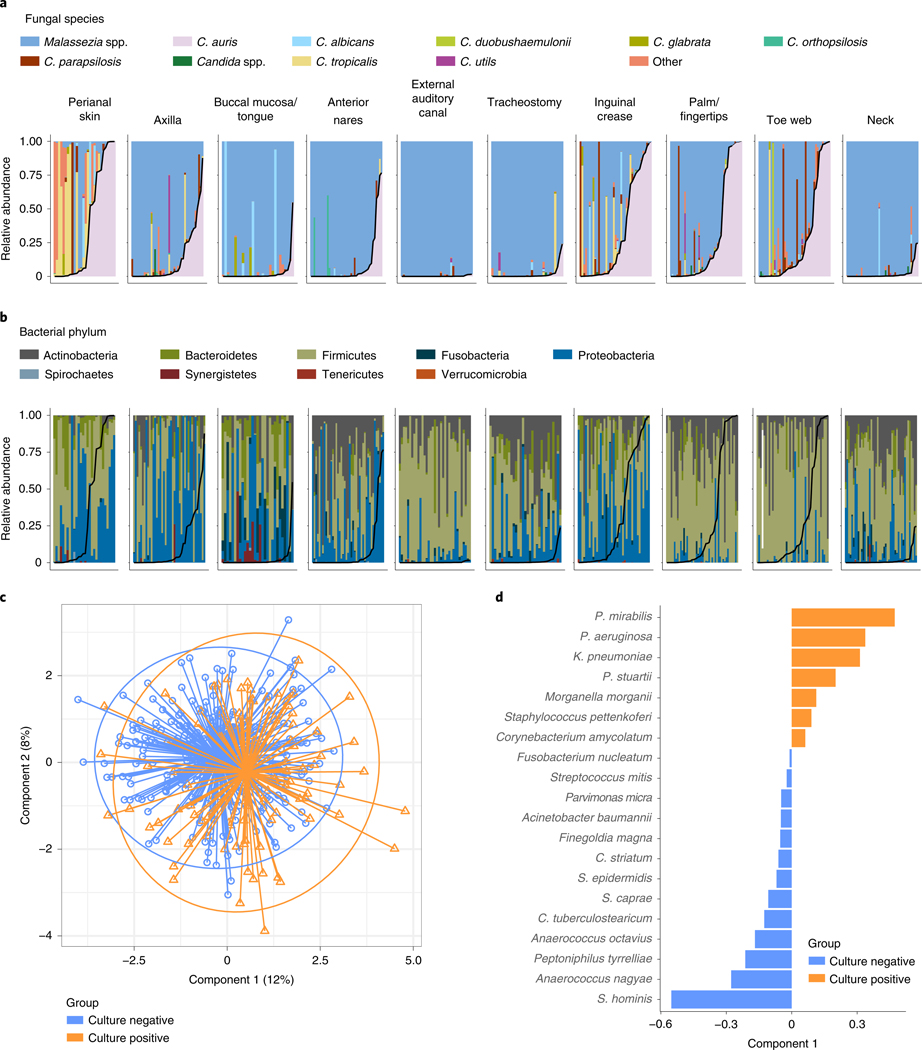

As C. auris must invade the microbiome to colonize human skin, we next explored associations between C. auris and features of the human microbiome. We characterized bacterial and fungal community composition by sequencing 16S rRNA and ITS1 regions from clinical samples collected during the first survey at each of ten body sites of 51 residents. While foundational studies of young healthy volunteers demonstrated Malassezia predominance of the skin mycobiome25, the mycobiome of these skilled nursing facility residents was composed of multiple Malassezia and Candida species (Fig. 3a). Candida species found on the skin included a diverse constellation of C. auris, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida albicans, Candida orthopsilosis, Candida duobushaemulonii, Candida glabrata, Candida krusei, Candida dubliniensis and Candida metapsilosis, among others. Sites exhibiting potential for Candida predominance included perianal skin, the axilla, nares, the inguinal crease, palms and/or fingertips and toe webs, overlapping with sites identified as commonly colonized with C. auris by culturing. More extensive comparisons between culture and sequence results highlighted confounding underlying biological principles. For example, while culturing may demonstrate a higher C. auris level in the nares than in the inguinal crease (Fig. 1c), sequencing results may not identify C. auris as the predominant species due to the diversity, composition and bioburden of the nares microbiome (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3 |. Underlying skin microbiome (fungal and bacterial communities) integrated with C. auris–colonization status.

Panels represent the body-site-specific relative abundance of fungal (a) or bacterial (b) organisms. Bars represent the 51 participants, ordered by C. auris abundance. The inner black curve represents the relative abundance of C. auris for each sample for each participant. a, Relative abundance of fungal species at each body site surveyed for each participant. Colors correspond to fungal genera or individual Candida spp. Genera included in the ‘other’ category include Saccharomyces, Trichosporon, Trichophyton and Aspergillus. b, Relative abundance of bacteria, colored by phylum, reveals site-specific associations of C. auris with Proteobacteria. c,d, Colors correspond to sample or loadings associated with culture negativity or positivity. c, Sample projection across first and second components of sPLS-DA. d, Variable loadings across the first sPLS-DA component.

Next, we sought to identify bacterial species enriched in C. auris–colonized samples. In a sparse, partial-least-squares discriminant analysis (sPLS-DA), Proteobacteria Proteus mirabilis, K. pneumoniae, Providencia stuartii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa contributed most to segregation of C. auris culture-positive samples away from C. auris culture-negative samples (Fig. 3b–d). Conversely, the skin commensal Staphylococcus hominis primarily contributed to the segregation of culture-negative samples away from culture-positive samples. Other commensal species, including Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus caprae and Corynebacterium striatum, were also found to have principal-component loading scores associated with C. auris culture negativity. Notably, P. mirabilis and P. stuartii were among a small set of taxa that exhibited a direct correlation with CHG concentration, indicating an association between increasing relative abundance of these species and increasing CHG concentrations (Extended Data Fig. 5).

Longitudinal analysis of C. auris colonization.

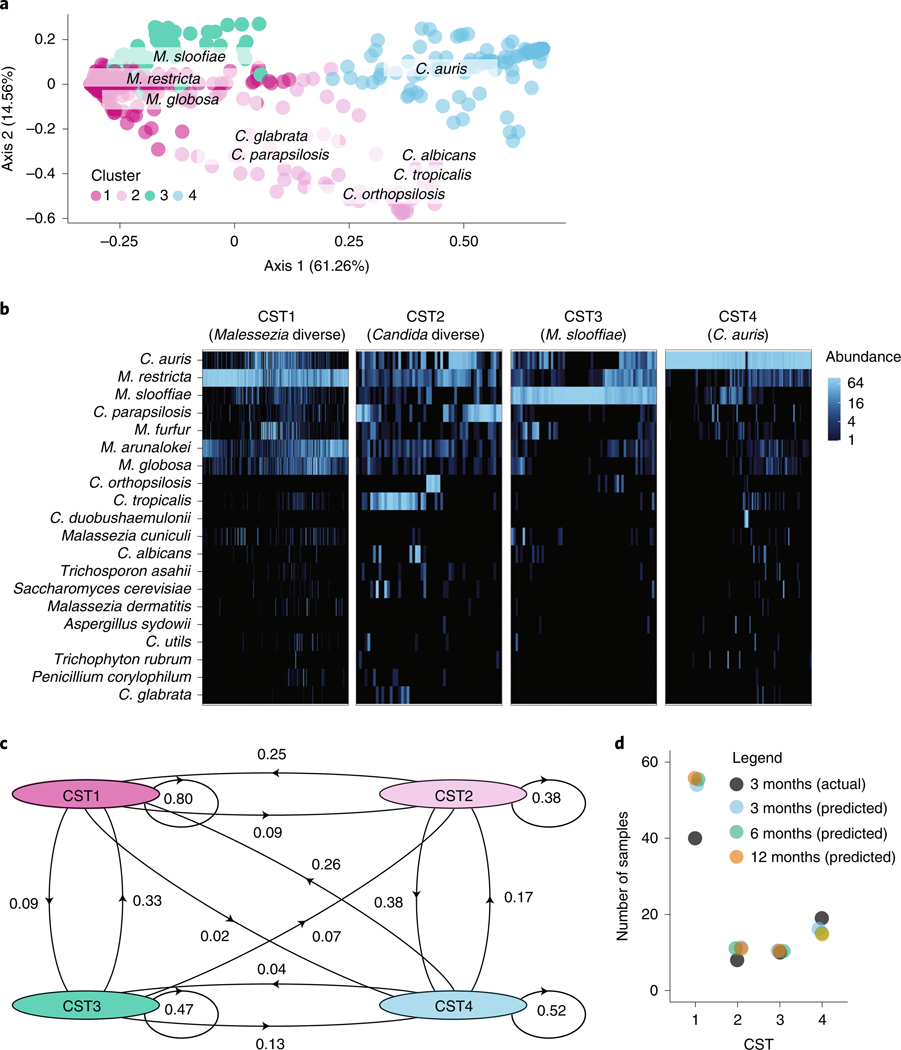

This longitudinal, observational clinical study was designed to explore microbiome alterations associated with C. auris acquisition and persistence. To explore mycobiome dynamics, the fungal community of samples from the monthly surveys was visualized by principal-coordinate analysis of the weighted UniFrac distance metric, which takes into account both phylogeny and relative abundance of taxa. Cluster analysis revealed four clusters or fungal community state types (CSTs) in the data (Extended Data Fig. 6). Predominance of either Malassezia (CST1, CST3) or Candida species (CST2, CST4) drove segregation of samples along the first major axis, which explained 61.3% of the variation (Fig. 4a). While genus-level differences defined axis 1, species-level variation drove segregation of communities along axis 2, which accounted for 14.6% of the variation.

Fig. 4 |. Skin fungal communities, dominated by Malassezia and Candida species, have differential stability, resilience and likelihood of invasion by C. auris.

a, Principal-coordinate analysis of the weighted UniFrac metric of the fungal community at each body site (toe webs, fingertips and/or palm, inguinal crease, anterior nares). Samples are shaded according to CST identity, as revealed by ‘partition around medoids’ analysis. CST1 tends to be dominated by M. restricta (N = 256, 53.0%), CST2 by a variety of Candida species (N = 52, 10.7%), CST3 by M. slooffiae (N = 62, 12.8%) and CST4 by C. auris (N = 113, 23.4%). Segregation of Malassezia and Candida species across the first axis explains 61% of the variance. Candida species segregate across the second major axis, which accounts for ∼15% of the variance. b, Relative abundance of the top 20 species in each sample, clustered by CST. Shading is based on the relative abundance of taxa within each sample. c, Self and interstate transition probabilities inferred for samples of the toe webs, palm and/or fingertips, inguinal crease and anterior nares. d, Scatterplot of the predicted numbers of samples in each CST at 3, 6 and 12 months after sample collection compared to the actual number of samples at 3 months. Predictions were generated using the Markov chain in c.

CST1 best approximates a typical healthy skin commensal community25, composed predominantly of Malassezia restricta and including other commensal Malassezia species: Malassezia globosa, Malassezia furfur and Malassezia arunalokei (Fig. 4b). CST2 was diverse with inclusion of multiple Candida spp., including C. auris, C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis. The remaining CSTs were less diverse. CST3 was predominated by Malassezia slooffiae, with frequent high-abundance co-colonization by either C. auris or M. restricta. Most samples in CST4 were mono-predominated by C. auris, although a few samples were co-predominated by M. restricta or C. parapsilosis.

Next, we investigated mycobiome dynamics, using data from the first two surveys to model the probability that an individual body site would transition between CSTs (Fig. 4c). Malassezia-diverse CST1 was the most stable state with the highest self-transition (‘remain the same’) probability (P = 0.82). By contrast, CST2, with diverse Candida species, not typically abundant on healthy human skin, comprised the least stable community. CST2 samples were as likely to transition to CST4 (predominated by C. auris) as they were to remain as CST2 (P = 0.38). By contrast, Malassezia-diverse CST1 samples rarely transitioned toward C. auris–predominant CST4 (P = 0.02), with higher transition frequency toward the diverse Candida CST2 (P = 0.07) or M. slooffiae-dominated CST3 (P = 0.09). While M. slooffiae, C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis25–27 rarely dominate the skin microbiome of healthy volunteers, they are often found at low abundance and low prevalence in skin communities. In sum, these data suggest potential value in monitoring or intervening at the intermediate state when the skin community migrates away from the diverse commensal Malassezia community.

To gain further insight into the stability of C. auris colonization, we used a Markov chain built from the first two point prevlence surveys to predict the number of samples in each CST at the third-point prevalence survey and to forecast patterns at time points beyond the study interval. This model predicts C. auris–colonization prevalence at the third-point prevalence survey (Fig. 4d) and forecasts persistent C. auris skin colonization across multiple sites for over a year. Persistent colonization is consistent with findings from our culture data, indicating that C. auris stably colonizes human skin, exhibiting particularly stable colonization at the nares (Extended Data Fig. 7).

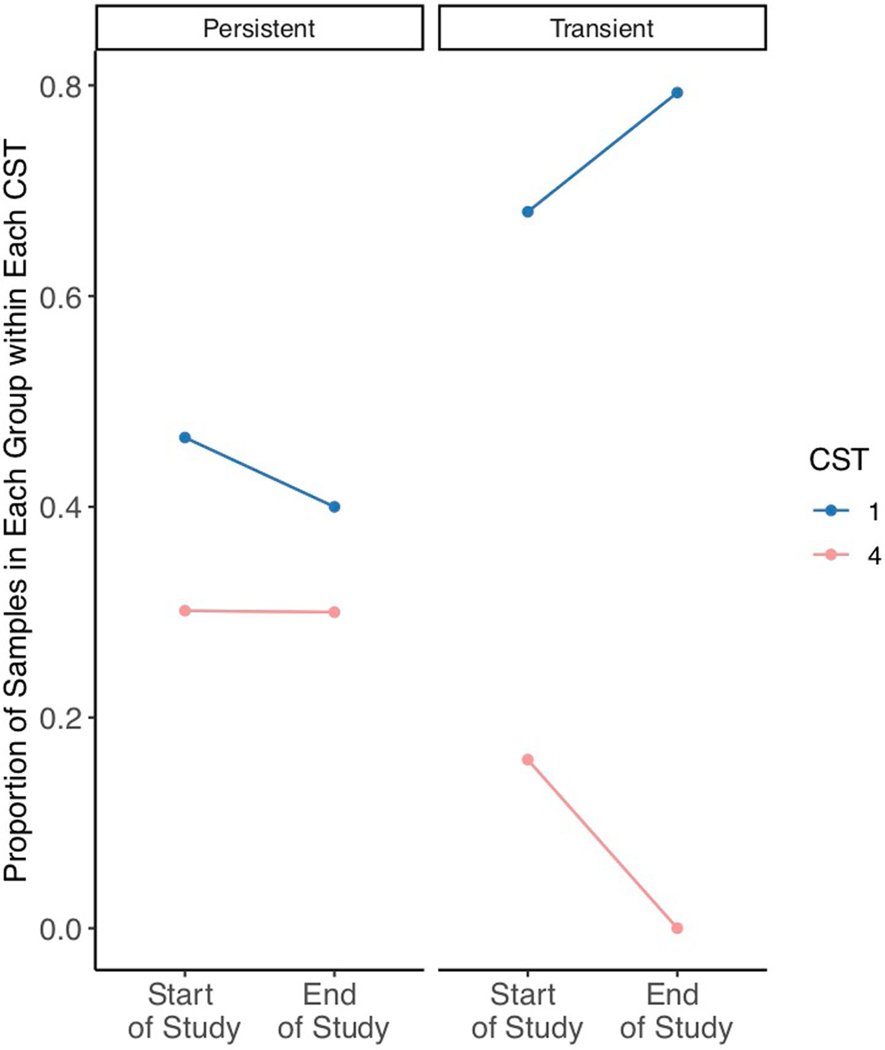

Over the course of the study, nine residents who were initially colonized at one or more body sites cleared C. auris colonization across all body sites by the end of the study. For these nine residents, the proportion of samples dominated by C. auris (CST4) decreased from 16.0% to 0% (CST4) from the first to the third time point, while the proportion of sites dominated by Malassezia species (CST1) increased from 68.0% to 79.3%, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 8). In individuals who were persistently colonized, by contrast, the proportion of samples dominated by C. auris remained roughly constant over time (∼30%). Communities that shifted away from C. auris toward Malassezia predominance experienced an increase in mycobiome diversity (Extended Data Fig. 9) and a reduction in proteobacterial abundances among the bacterial community in concert with the loss of C. auris. Clinically, transiently colonized residents were less likely to require mechanical ventilation or gastrostomy tubes than residents who were persistently colonized (χ2, P < 0.05).

Collectively, these data suggest the resilience of the commensal skin communities to initial invasion. However, once C. auris establishes predominance in a community, it is capable of establishing persistent colonization of the skin.

Discussion

Here we integrate genomic, clinical and epidemiologic data, analyzing almost 4,000 samples from 57 residents over a 3-month period to investigate factors underlying persistent C. auris colonization of residents of the ventilator ward of a skilled nursing facility with endemic C. auris and routine CHG bathing. Our investigation provides insights that can be applied to the design of potentially more effective programs to control C. auris transmission and prevent infections in long-term care settings, which bear a disproportionate burden of C. auris disease.

Colonization of sites not screened routinely may facilitate healthcare-associated transmission17. Screening of residents at high risk of C. auris carriage is typically carried out by collecting a composite bilateral axillae and inguinal creases swab sample. In our study, unilateral screening of axilla and inguinal crease would have detected only 35 of 57 colonized residents; we found that screening of six body sites was required to identify all colonized residents. The nares and palms and/or fingertips were colonized more frequently and carried higher bioburdens than other sites. While the inguinal creases and axillae were identified by Public Health England to be the two most persistently positive sites18, a study conducted by the New York State Department of Public Health reported the sensitivity of anterior nares to be higher than that of composite axillae and inguinal creases28. Quantitative culture results of South Asian clade I from New York State and those of South American clade IV in our study are concordant, demonstrating higher bioburden in anterior nares than in axillae and/or inguinal creases for C. auris–colonized residents. Because sampling six body sites may not be practical for routine screening, targeting high-yield sites such as axillae and/or inguinal creases and anterior nares is still recommended. Modifying screening strategies to include additional body sites during intractable outbreaks may permit identification of reservoirs for intrafacility transmission. Investigating innovative specimen collection methods, such as using sponge swabs to sample larger areas of skin29, may also be of benefit. Frequent and dense colonization of anterior nares and palms and/or fingertips suggests that nasal decolonization and promotion of resident hand hygiene may be options to help reduce cross-transmission of C. auris in skilled nursing facilities. Finally, the imperfect sensitivity of most screening methods highlights the importance of universal, facility-wide infection-prevention measures, such as healthcare provider hand hygiene and environmental disinfection, in reducing C. auris transmission.

Despite the apparent susceptibility of C. auris isolates to CHG in vitro, the odds of recovering C. auris from skin sites by culture were reduced only at high measured concentrations of CHG. It is notable that the nares, a site not subject to CHG bathing, and the body sites with the lowest average concentration of CHG (palms and/or fingertips and toe webs) were frequently and densely colonized with C. auris. Heterogeneity in CHG concentration may have been due to differences in time since the last CHG bath, a variable not recorded by ventilator-capable skilled nursing facility personnel. Relatively high concentrations of CHG observed in inguinal samples may result from increased focal bathing as part of incontinence care. Nevertheless, our finding that only 7.3% of samples had concentrations of CHG sufficiently high to be associated with reduced odds of C. auris colonization suggests that a point of intervention may be ensuring that all skin sites maintain high residual concentrations of CHG10. We were encouraged to find no evidence of an association between CHG concentration and perturbation of the commensal skin microbiome.

Persistent C. auris colonization reported here is consistent with observations of several patient and resident populations in acute and long-term care settings, respectively3,18, including another facility with routine CHG bathing9. Our analysis of mycobiome dynamics suggests that commensal, Malassezia-predominated communities are resilient to invasion by C. auris. By contrast, we observed that C. auris predominance is relatively stable once it occurs, with a 30–50% chance that C. auris will persist at sites once it comes to dominate. The ascension of C. auris to dominance in the community appeared to occur through an intermediate state (CST2) in which diverse Candida spp. co-predominate skin sites with a ∼40% probability that sites would transition from the diverse Candida state toward C. auris predominance. This finding is consistent with prior work demonstrating that C. auris has a higher predilection for skin colonization than does C. albicans6,30, which in turn is a better skin colonizer than C. tropicalis or C. parapsilosis26.

Our observation that a community of diverse Candida species is an intermediate state between commensal Malassezia and C. auris predomination provides an additional possible point of intervention for infection prevention. While we did not examine the in vitro susceptibility of Malassezia spp. to CHG, microbiome sequencing results failed to provide evidence of a linear relationship between CHG concentration and the abundance of Malassezia spp. Selection of C. auris by CHG bathing is one possible explanation for the high transition rate to C. auris predominance. However, countering this argument is our observation that C. auris was more stable at the nares, a site not subjected to CHG bathing, as compared to sites undergoing bathing. Our analysis revealed a variety of Gram-negative bacterial species commonly found in nursing home settings, including P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis, K. pneumoniae and P. stuartii, to be enriched in C. auris–positive samples. However, due to the widespread prevalence of C. auris in the facility at the outset of the study and complex medical histories of these residents, we could not determine whether the bloom of Gram-negative species preceded C. auris colonization or vice versa, nor could we determine the temporal relationship between antibiotic receipt and colonization with these Gram-negative bacteria or C. auris. Similarly, our study design precluded determination of whether associations of C. auris colonization with other clinical covariates, such as mechanical ventilation, reflect merely the generally poorer health of colonized residents or are causally related to colonization. Elucidating the effect of antibiotic exposure on skin microbial communities and C. auris colonization and dominance is of particular importance, as this risk factor may be modifiable. Exposure to a carbapenem, vancomycin or fluconazole was associated with increased odds of C. auris colonization in another recent study of long-term care residents31.

One limitation of this study is that the different clades of C. auris may exhibit different body-site tropisms; therefore, our results may not be generalizable to colonization with C. auris other than South American clade IV. The single-center setting of our study also may reduce its generalizability. Sample collection for this work began after prevalence at the facility reached saturation, making it difficult to understand patterns of diversity in the microbiome before the intro- duction of C. auris. To gain insight into how antibiotic-mediated reductions in colonization resistance might increase risk of colonization, future work should aim to disambiguate the onset of these effects in other healthcare settings. Finally, our experimental design enabled quantification of CHG concentrations across body sites but lacked a comparator group against which we could assess the impact of CHG bathing as a controlled intervention.

Our data suggest that residents of ventilated skilled nursing facilities where C. auris is endemic and CHG bathing is routine have highly personalized patterns of C. auris skin colonization. This site-to-site variability in colonization limits infection-control strategies predicated on targeting only known C. auris–colonized individuals; facility or unit-wide infection-control approaches may be more effective. We found that perturbation of the skin micro- biome is a potential risk factor for C. auris colonization and per- sistence. These data have implications not only for facilities where C. auris is endemic but also for other facilities embedded within the same regional healthcare networks32. While C. auris outbreaks in the United States have been reported primarily in long-term care settings, a recent report of a C. auris outbreak in a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) specialty care unit highlights the threat that C. auris poses to acute care hospitals33. Our findings have identified candidate targets for future interventions related to skin microbiome dynamics, including the potential for preserving or restoring commensal skin microbiota to augment existing approaches for C. auris control.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01383-w.

Methods

Participant recruitment.

This research complies with all relevant ethical human research regulations. The study was reviewed and approved by the Rush University Institutional Review Board, which granted expedited review and waiver of informed consent. Study participants did not receive monetary compensation for their participation. Demographics of the participant population are reported in Table 1.

Statistics and reproducibility.

We conducted an observational, serial cross-sectional study of residents of a ventilator-capable skilled nursing facility (vSNF) in Chicago, IL, USA. All residents on the 70-bed ventilator ward of the 300-bed vSNF at the time of the first survey were eligible for study participation. Although this work was exploratory, we conducted an a priori power analysis to ensure that we would have sufficient power to detect notable differences in the prevalence of C. auris colonization at different body sites, that is, to test the null hypothesis of uniform distribution of C. auris across body sites. When we were planning the study, we anticipated participation of 35 residents with C. auris colonization and 25 residents without C. auris colonization during the three serial point prevalence surveys. We based these estimates on documented incidence, prevalence and turnover rates at that time and an assumption of 80% resident participation. Assuming participation of 35 C. auris–colonized residents, true positive rates at the reference site ranging from 70% to 90% and α = 0.05, we calculated that we would have 80% power to detect relative risk in any comparison site ranging from 0.62 to 0.75, that is, 44–68%. In fact, we identified 45 C. auris–positive residents and 12 C. auris–negative residents during the first survey. Therefore, rather than seeking new residents to test during each of the subsequent two surveys, we continued to follow the original 57-resident cohort, eventually identifying a total of 49 residents who were ever positive for C. auris and eight residents who were never positive for C. auris.

Statistics on clinical variables describing the study cohort.

Odds ratios and two-tailed P values for continuous variables (that is, length of stay before the first swab, age, Charlson comorbidity index and Braden score) were determined using binary logistic regression analyses with P values determined by Wald χ2 statistics. For dichotomous variables, two-tailed P values were determined from Fisher’s exact tests. To calculate an odds ratio for mechanical ventilation and antifungal receipt in the prior 90 d, where the values in the ‘not colonized’ group are 0, logit estimates were used, in which a correction of 0.5 was added to each cell in the table. None of the P values for clinical analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Estimating the proportion of colonized residents by body sites.

The proportion of colonized residents was calculated as previously described34. Exact binomial 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the ‘epi.tests’ function in the ‘epiR’ package.

Estimating sensitivity of sites for identifying colonized residents.

We used a custom function leveraging the ‘combn’ function in base R and the ‘epiR’ package to generate the ‘proportion of colonized individuals’ for all possible two-way (n = 45), three-way (n = 120), four-way (n = 210), five-way (n = 252), six-way (n = 210), seven-way (n = 120), eight-way (n = 45) and nine-way (n = 10) groupings of the ten body sites. Sensitivity was computed by dividing the ‘proportion of colonized individuals’ by the proportion of residents positive at any body site.

Estimating bioburden of C. auris across body sites.

Flocked swabs (FLOQSwabs, Copan) were used to sample a 5 × 5 cm2 area from each body site and were placed immediately in Amies medium with neutralizer without ether sulfate35,36. Aliquots (100 µl) were inoculated directly onto CHROMagar Candida plates (Becton Dickinson) and incubated at 37 °C for 7 d. A second 100-µl aliquot was inoculated into Salt Sabouraud Dulcitol Broth and incubated at 40 °C for 7 d; cloudy broth cultures were subsequently inoculated onto CHROMagar Candida plates37 and incubated for 7 d. Each unique colony morphology underwent identification to the species level by MALDI-TOF (VITEK MS Plus (bioMérieux). Resulting CFU from directly inoculated plates for all colonized sites (excluding uncolonized sites) at the first time point were plotted with the ‘geom_density_ridges’ function in the package ‘ggridges’.

Axilla, inguinal crease and anterior nare samples were also processed with an MPN method that tested eight serial dilutions of the original sample with the enrichment broth method. Three replicates were performed for each dilution, enabling calculation of an MPN as described at https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bam-appendix-2-most-probable-number-serial-dilutions. High-throughput-format MPN analysis was performed using 96-well 2-ml deep-well blocks in which 500-µl volumes of Sabouraud broth with dulcitol, chloramphenicol and gentamicin were inoculated with 50-µl sample aliquots from each replicate for each dilution. Culture blocks were incubated at 40 °C for 7 d before plating onto CHROMagar Candida plates in 10-µl volumes. Plates were checked for growth after 7 d. Growth with morphology characteristic of C. auris was confirmed for both culture methods to the species level using MALDI-TOF.

CHG and antifungal susceptibility testing and determination of the CHG concentration on skin.

To determine the CHG concentration on skin, swabs (Bio-Swab, Arrowhead Forensics) moistened with sterile water were used to sample areas of skin adjacent to those areas that were sampled for culture and microbiome analysis, only at sites bathed routinely with CHG. CHG concentrations were measured using a quantitative colorimetric method that was read by visual inspection as described previously38.

CHG susceptibility was determined using a yeast broth microdilution method in accordance with CLSI guidelines39,40, starting with a 20% solution of chlorhexidine digluconate (Sigma). Susceptibility to selected antifungal agents was determined using a commercial microdilution method (Sensititre YeastOne YO9 AST Plate, Thermo Scientific) and applying tentative breakpoints published by the CDC41.

Association of CHG concentration with C. auris colonization.

Mixed-effects regression models were used to control for clustering of body sites within residents over time. For CHG concentration by body site, a mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression model was used. For testing the relation between CHG concentration (log2 transformed) and C. auris, a series of mixed-effects binary logistic regression models was used. The first model tested the linear relation between CHG concentration and C. auris colonization (log2 transformed), controlling for body site. This was followed by a series of ten models testing cutoff points for CHG concentration at each successive increment in the semiquantitative test for CHG concentration.

Microbiome sample collection, DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing.

Swab samples from each anatomic site were collected (Extended Data Fig. 1) using our previously published protocols; negative controls were also collected and subsequently processed in parallel with true samples as described previously42. Briefly, foam swabs (Puritan, 2515061PF) were premoistened with Yeast Cell Lysis solution (Lucigen) and used to collect swab samples from the skin across individual sites that were adjacent to sites sampled for culture and CHG-concentration measurement. Swabs were stored in lysis solution at −80 °C following collection. For extraction, skin swabs were incubated in Yeast Cell Lysis buffer and Ready-Lyse Lysozyme solution (Lucigen) for 1 h with shaking at 37 °C. Steel beads (5 mm) were added to mechanically disrupt fungal cell walls using a TissueLyser (Qiagen) for 2 min at 30 Hz, followed by 30-min incubation at 65 °C for complete lysis. MPC reagent was added to samples, and resulting supernatants were processed using the PureLink Genomic DNA kit (Invitrogen). DNA was eluted in DNA-Free PCR Water (Qiagen).

The ITS1 region was amplified using primers modified with Illumina adaptors 18S-F (5′-GTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGGTTTC) and 5.8S-1R (5′-GTTCAAAGAYTCGATGATTCAC) as previously described43,44. The following PCR conditions were used: 2.5 µl 10× PCR buffer, 4 µl dNTP mix, 0.25 µl Takara LA Taq Polymerase (Clontech), 1 µl 18S-F (10 µM), 1 µl 5.8S-1R (10 µM), 13.75 µl PCR Water (Qiagen) and 2.5 µl DNA. Reactions were performed in duplicate for 30 cycles, combined, purified using the Agencourt AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter) and quantified using the Quant-iT dsDNA kit (Invitrogen). Equivalent amounts of amplicons were pooled together, purified with the MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq. The V1–V3 region of the bacterial 16S gene was amplified under similar conditions using primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG) and 534R (5′-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG).

Demultiplex and quality filtering of amplicon tables.

A total of 5.3 × 107 raw reads were analyzed for 16S amplicons, while a total of 1.47 × 107 raw reads were analyzed for the ITS1 table. Forward and reverse reads were independently demultiplexed, and sequences were parsed into sample-specific files with Illumina’s ‘bcl2fastq’ version 2.20 software; primers were trimmed from sequences using cutadapt 2.10* before import into R 3.6.1 for quality filtering with the R package ‘dada2’; the ‘filterAndTrim’ function was used to truncate reads at the first instance of a quality score of 2 before elimination of reads with more than 0 ambiguous characters, a maximum expected error exceeding 2 or a length less than 50 nucleotides. Error rates were learned independently on filtered forward and reverse reads using default parameters before dereplication, inference of sequence-specific errors (with self-consistency set to true and pooling set to true) and elimination of problematic reads. Dereplicated and filtered forward sequences were subsequently merged with their paired-end reads before construction of an amplicon sequence variant (ASV) table. The ‘removeBimeraDenovo’ function of dada2 set to the ‘consensus’ method was used to filter chimeras from each ASV table. Taxonomic assignment was then performed down to the species level when possible using the dada2 implementation of the RDP Naive Bayesian Classifier 3 trained on the RefSeq database version 2.0 downloaded in May 2018 for bacterial reads and the UNITE ‘sh_general_release_dynamic’ database downloaded on 2 February 2019. Datasets generated as direct output from dada2 are referred to as ‘merged_16s’ and ‘merged_ITS’, and sequencing depths associated with these tables were 12,466,948 (16S) and 39,481,121 (ITS).

Quality control of the sequence tables.

To deplete taxa enriched in extraction controls and therefore likely associated with contamination, a data subset was generated, consisting only of the technical controls (16S, n = 150; ITS, n = 90), which were sequenced in parallel with true samples (16S, n = 1,258; ITS, n = 1,318). An enrichment score was calculated for enrichment of taxa in controls compared to samples and vice versa; taxa enriched in controls relative to samples were deleted from the dataset as previously described45. Filtering using this method reduced the 16S table to 854 taxa across 1,243 samples and the fungal table to 136 taxa across 1,226 samples. Reads were agglomerated to the taxonomic rank of species using the ‘tax_glom’ function of ‘phyloseq’. Subsequent to taxonomic agglomeration, samples with fewer than 500 reads per sample were dropped. Finally, samples were dropped from the 16S table if the ITS1 sample failed quality control, generating sample sets of equal size (n = 1,152) across ‘bac_match’ and ‘its_match’ datasets.

Identifying bacteria associated with colonization.

To reduce the influence of highly variant taxa on findings, species present in fewer than 20% of 16S samples were dropped. Reads were subsequently transformed using centered-log-ratio transformation as implemented in the ‘compositions’ package. The ‘splsda’ function of the ‘mixomics’ package was used to identify bacterial species positively or negatively associated with C. auris culture.

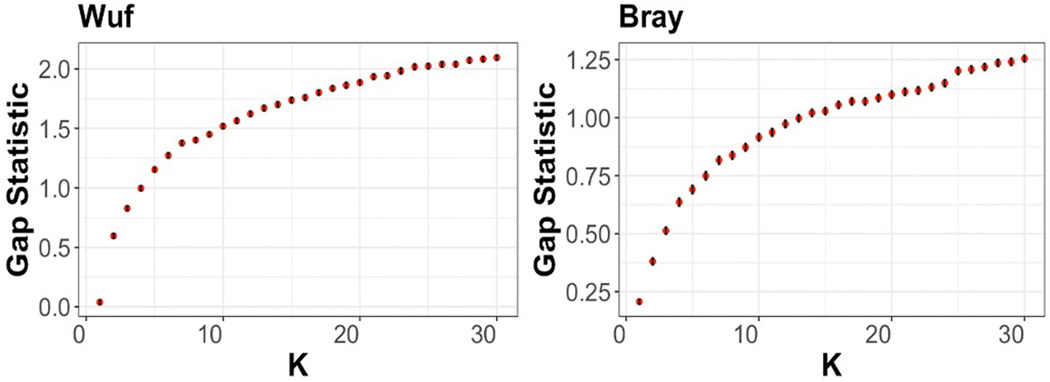

Community state type analysis.

The weighted UniFrac statistic was computed on Malassezia and Candida species with the distance function of ‘phyloseq’ before performing independent rounds of cluster analysis from one to 30 clusters using the ‘partition around medoids’ function of the ‘cluster’ package. The gap statistic was computed for each cluster analysis from one to 30 using the ‘clusGap’ function and 1,000 Monte Carlo bootstrap samples. To evaluate the robustness of the identification of four clusters in the data, this process was repeated using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity metric. The four clusters for the weighted UniFrac analysis were subsequently labeled as CSTs.

Markov chains.

A data subset was generated in which only samples from 23 residents who had a complete set of survey 1 and survey 2 samples at the fingertips, toe webs, nares and inguinal crease were retained. Based on prior work46, a custom function was written to generate the initial state matrices from the phyloseq S4 object ‘its_match’. Transition matrices were obtained with a custom function that standardized each initial state matrix to four rows and four columns before normalization to row sums. Missing values, corresponding to states that were not observed at a given site, were replaced with 0. Each transition matrix was subsequently used as input for the new ‘markovchain’ function of the ‘markovchain’ package. Predictions for N-month time points were obtained by multiplying the initial state matrix by the transition matrix raised to the Nth power. Each transition matrix was visualized using a custom function leveraging the ‘plotmat’ function in the ‘diagram’ package.

Illumina whole-genome sequencing.

Isolates of C. auris (various clades) were streaked onto CHROMagar Candida plates (BD, 254093) and incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h. Colonies were transferred to 600 μl Yeast Cell Lysis buffer (Lucigen, MPY80200) with 3 μl RNase (Qiagen, 19101) and 1-mm glass beads (MP Biomedicals, 116912050-CF). Cells were subjected to bead beating in a FastPrep 5G (MP Biomedicals) at speed 6.5 for 15 s and placed on ice for 1 min, and the procedure was repeated. The cell lysate was incubated at 65 °C, and the protocol continued as directed (Lucigen, MPY80200). The genomic DNA pellet was resuspended in 0.1× TE, pH 8.0. Libraries were generated from genomic DNA with the Nextera XT Library Preparation kit (Illumina) as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Libraries were pooled at an equimolar ratio for sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 to obtain a minimum of 2.6 million 151-bp reads per individual library. Illumina sequence data were processed using RTA version 3.4.4.

Nanopore sequencing and assembly.

A fraction of genomic DNA prepared for lllumina whole-genome sequencing was reserved for nanopore sequencing and assembly. Genomic DNA was assessed by Femto Pulse (Agilent) analysis and determined to be approximately 15 kb; therefore, shearing was not performed. A library was prepared for long-read Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing from 1 μg DNA using the Ligation Sequencing kit (ONT, SQK-LSK109). Twenty fmol of the library was sequenced on an R9 flow cell using the ONT GridION platform running MinKNOW 3.6.5 and run for 72 h with refueling at 48 h. Guppy 3.6.0 was used to convert raw sequence data files to basecall fastq files. A total of 13.0 Gb of data was collected with an N50 length of 14.3 kb and a mean read length of 11.4 kb. ONT sequence reads were randomly downsampled to an estimated 200× coverage using ‘seqtk’ version 1.2 (https://github.com/lh3/seqtk) and assembled using Canu 2.0 (ref. 47). Assembled contigs were polished with the ONT sequence reads for one round using Racon version 1.3.1 (ref. 48), followed by two rounds with medaka version 1.0.3 (https://github.com/nanoporetech/medaka). Contigs were polished further by aligning Illumina short reads using Bowtie 2 version 2–2.4.2 (ref. 49) and running Pilon version 1.23 (ref. 50) on the alignment file.

Variant calling.

Illumina NovaSeq reads for each of four outbreak isolate genomes were aligned to the nanopore reference genome, and single-nucleotide variants were identified with snippy version 4.4.1 (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy) with default options deploying BWA version 0.7.17 and FreeBayes version 1.3.5 algorithms, requiring a read depth of at least 10× and the additional flag ‘–minfrac 0.9’, requiring at least 90% of reads in support of the variant nucleotide call. SAMtools (version 1.11) coverage was used to estimate coverage and mapping quality across the genomes of isolates (mean coverage, 99.99; mean MAPQ score, 59.6).

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Sequencing data are publicly available in the NIH Short Read Archive under BioProject accession number PRJNA672955. The RefSeq database version 2.0 downloaded on May 2018 and the UNITE ‘sh_general_release_dynamic’ database downloaded on 2 February 2019 were used to assign bacterial and fungal taxonomy, respectively, and can be found at https://github.com/skinmicrobiome/cauris_colonization. Intermediate data files including the OTU table, the taxonomy table and the sample data mapping file are included in Supplementary Data 1.

Code availability

The R code used to generate figures is provided in Supplementary Data 2–5 and can be found at https://github.com/skinmicrobiome/cauris_colonization.

Extended Data

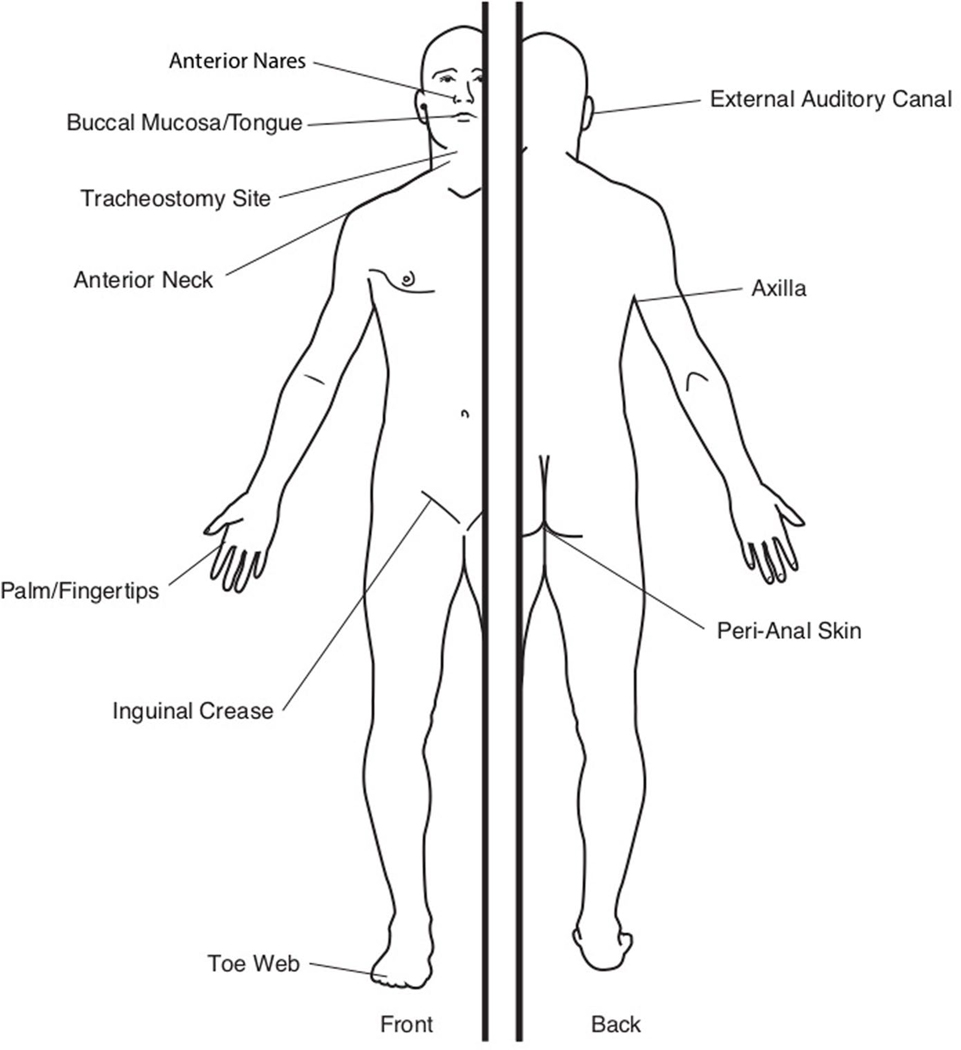

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Map of sample sites.

We surveyed 10 body sites per subject, including the anterior nares (N), tracheostomy site (Tc), anterior neck (Ne), palms/fingertips (Fg), buccal mucosa/tongue (Bu/To), inguinal crease (Ic), axilla (Ax), toe web (Tw), external auditory canal (Ea), and peri-anal skin (An).

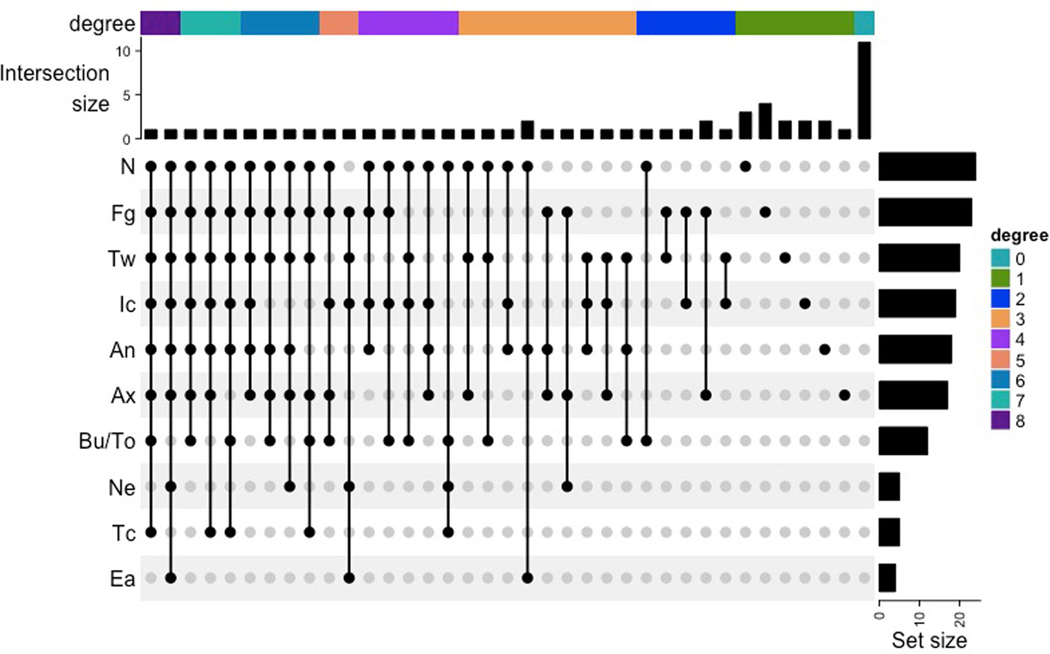

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Patterns of body site colonization visualized with UpSetR.

Colors map to degree, a measure of the number of co-colonized sizes. A total of 36 distinct co-colonization patterns were observed, each arranged from the left to the right as a function of decreasing degree. The intersection size is the number of subjects whose body-site colonization matches the points connecting sites for each of the 36 unique co-colonization patterns. For example, the nares (N) and fingertips/palm (Fg) are more frequently mono-colonized than any of the other sites while the buccal mucosa/tongue (Bu/To), neck (Ne), tracheostomy site (Tc), and external auditory canal (Ea) are never mono-colonized. Most patients have a distinct pattern of co-colonization with the most frequent pattern being singular colonization of the nares (N) or fingertips/palm (Fg). The set size corresponds to the frequency of colonization for each site for the first time point.

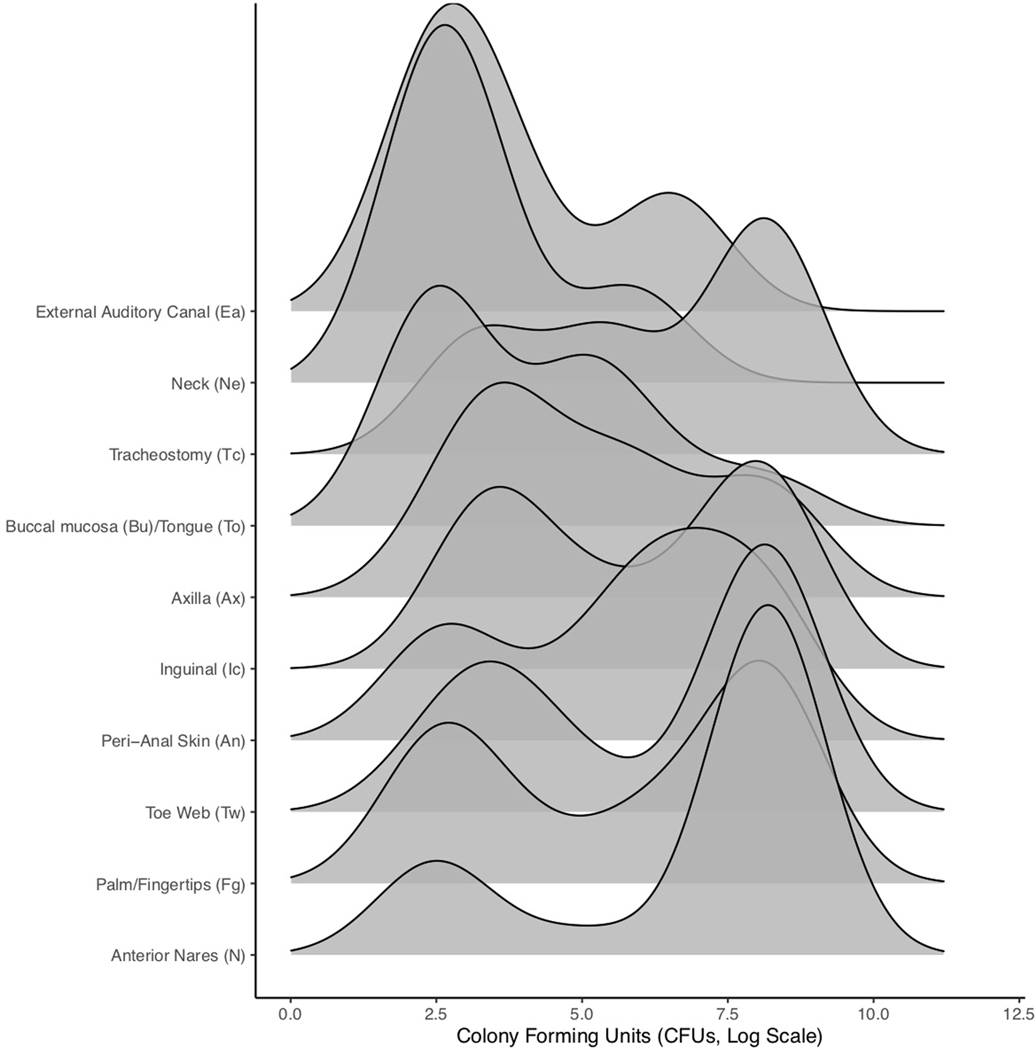

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Ridgeline plot of sample colony counts for each site during the first survey.

The cumulative distribution for each ridgeline sums to 1, with peaks corresponding to peak bioburden (log colony forming units), for each site. For any given site, a bimodal distribution indicates a subset of subjects shared relatively high bioburdens and another a subset of subjects shared relatively low bioburdens. Sites with low level colonization include the external auditory canal and neck while sites having the highest bioburden include nares and inguinal crease.

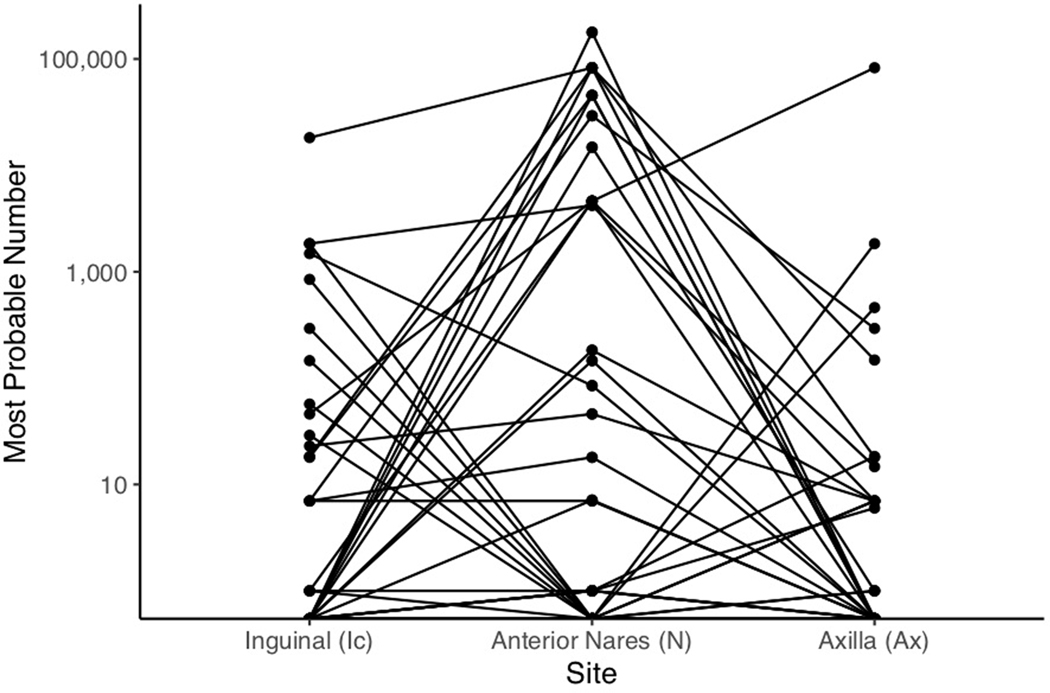

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Paired Most Probable Number (MPN) Analysis.

MPN estimates are shown for the inguinal crease, anterior nares, and axilla. Data represented are from the first point prevalence survey. Each line represents an individual. Individual trajectories reveal a large number of individuals with high counts at the nares and either absent or low-level colonization at the axilla or inguinal crease.

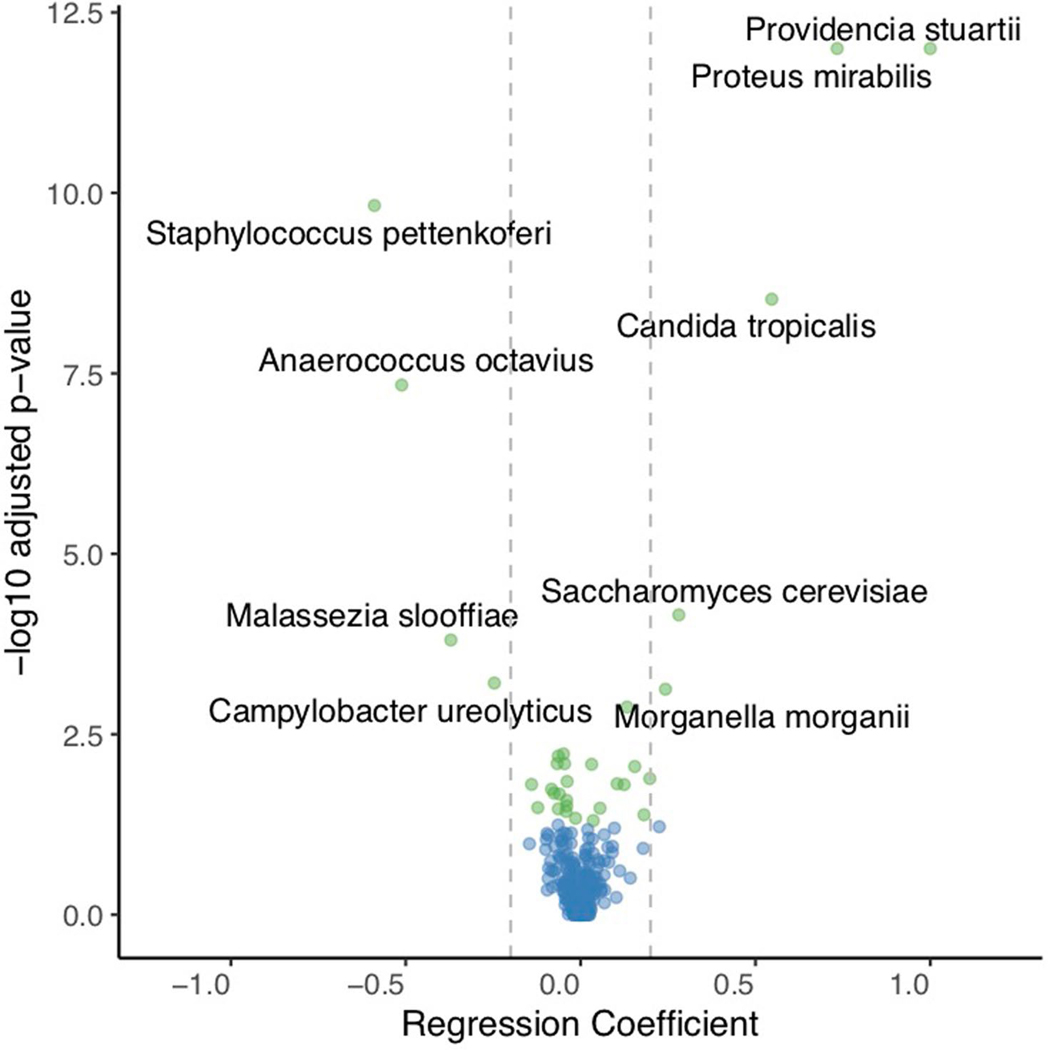

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Volcano plot of statistical significance (-Log adjusted p-value) against the regression coefficients from linear mixed effects models.

Each point represents a regression coefficient for a bacterial or fungal species. The vertical lines demarcate regression coefficients of −0.2 and 0.2. Species having Holm adjusted p-values < 0.05 are highlighted in green while non-significant taxa are in blue. Species exhibiting a positive association with CHG concentration (skin concentrations (estimate > 0.2, Holm adjusted p < 0.05) include Providencia stuartii, Proteus mirabilis, Candida tropicalis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Morganella morganii. Species exhibiting a negative correlation with CHG skin concentrations (estimate < −0.2, Holm adjusted p < 0.05) include Staphylococcus pettenkoferi, Anaerococcus octavius, Malassezia slooffiae, and Campylobacter ureolyticus.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Evaluation of the robustness of cluster formation.

Weighted UniFrac (Wuf) and Bray-Curtis (Bray) distances were computed prior to partition around medoids analysis. The gap statistic (y-axis) is plotted as a function of K (x-axis), defined as the number of clusters evaluated. The error bars correspond to the confidence interval generated on 1000 bootstraps. The optimal number of clusters corresponds to K where additional clusters fail to increase the gap statistic using both a phylogenetically aware distance metric (UniFrac) and Bray Curtis.

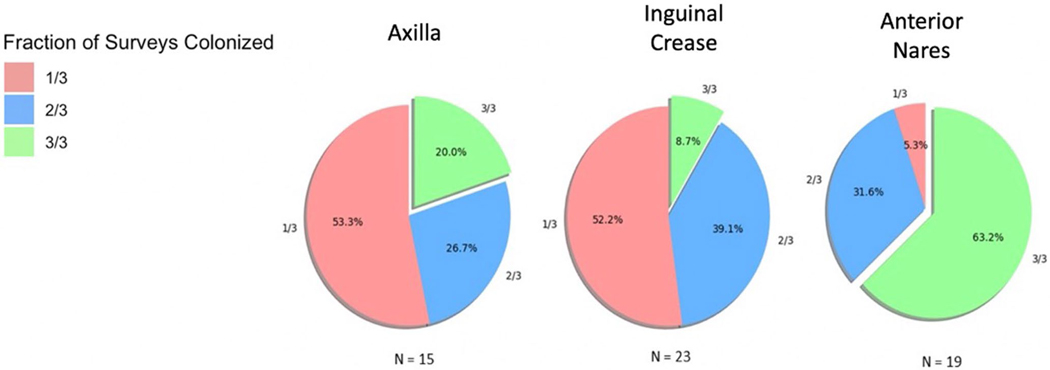

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Temporal stability of C. auris colonization at the axilla, inguinal crease and anterior nares.

Patients who were qualitatively categorized as positive at least once, based on MPN data, were categorized as positive in 1 of 3 (pink), 2 of 3 (blue) or 3 of 3 (green) surveys. The majority of subjects colonized at axilla and inguinal crease were positive in 1/3 surveys while the majority of individuals colonized at the nares were positive at all 3 surveys.

Extended Data Fig. 8 |. Proportion of sites within each CST over time for individuals who were either transiently or persistently colonized.

The proportion of samples dominated by C. auris (CST4) remained roughly constantly (∼30%) for individuals who were persistently colonized (Left). In contrast, the proportion of sites dominated by C. auris dropped from 16% to 0% from the first to the third time point in transiently colonized individuals (Right). Among those transiently colonized, the reduction in sites dominated by C. auris was accompanied by a concomitant increase in the proportion of sites dominated by commensal Malassezia species. Of special interest, the proportion of sites dominated by Malassezia species was higher across all time points for those who were transiently colonized compared to those persistently colonized.

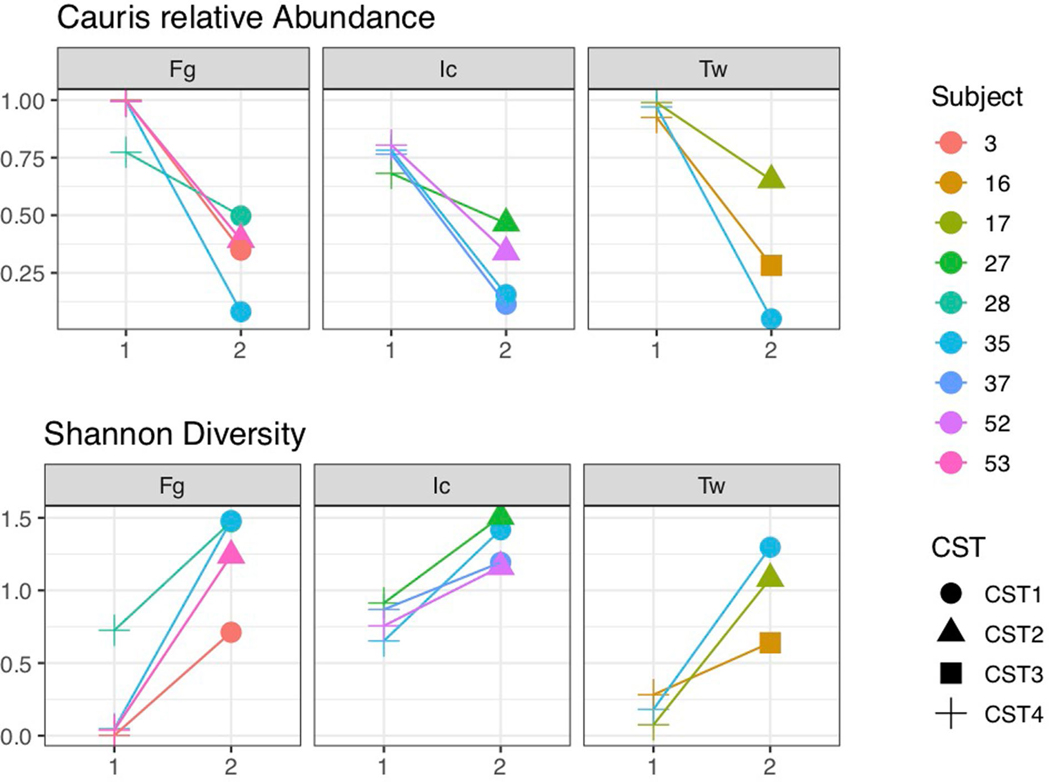

Extended Data Fig. 9 |. Examination of the mycobiome at sites that transition away from C. auris domination between survey 1 and survey 2.

Colors correspond to unique subjects. Shapes correspond to the mycobiome CST. Across all panels, survey 1 or 2 is shown on the x-axis. On the y-axes, the relative abundance of C. auris (top panel) or Shannon diversity (bottom panel) is depicted. For this analysis we looked exclusively at sites that transitioned away from domination by C. auris at the first survey (Survey 1) towards domination by another species at the second time point (Survey 2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC. This work was supported in part by CDC contract number 75D30118C02900. This study used the computational resources of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) HPC Biowulf Cluster (http://hpc.nih.gov). This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the NIH National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the National Human Genome Research Institute. We thank J. Fekecs for assistance rendering publication-ready figures.

Footnotes

Competing interests

M.K.H. has been a co-investigator on several research studies for which Sage Products (now part of Stryker Corporation), Molnlycke and Medline provided chlorhexidine products at no charge to hospitals and skilled nursing facilities participating in the research. Neither M.K.H. nor her employer (Rush University Medical Center) received chlorhexidine products. M.Y.L. has received research support in the form of contributed product from Sage Products (now part of Stryker Corporation) and has received an investigator-initiated grant from the CareFusion Foundation (now part of BD). All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01383-w.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01383-w.

Peer review information Nature Medicine thanks Tobias Hohl, Sudha Chaturvedi and Iliyan Iliev for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Alison Farrell was the primary editor on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.Jeffery-Smith A et al. Candida auris: a review of the literature. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, e00029–17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsay S et al. Notes from the field: ongoing transmission of Candida auris in health care facilities—United States, June 2016–May 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 66, 514–515 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vallabhaneni S et al. Investigation of the first seven reported cases of Candida auris, a globally emerging invasive, multidrug-resistant fungus—United States, May 2013–August 2016. Am. J. Transplant. 17, 296–299 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J et al. Is the superbug fungus really so scary? A systematic review and meta-analysis of global epidemiology and mortality of Candida auris. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 827 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 (US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2019). . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton MV et al. Candida auris forms high-burden biofilms in skin niche conditions and on porcine skin. mSphere 5, e00972–19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weschler CJ et al. Squalene and cholesterol in dust from Danish homes and daycare centers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 3872–3879 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biswal M et al. Controlling a possible outbreak of Candida auris infection: lessons learnt from multiple interventions. J. Hosp. Infect. 97, 363–370 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schelenz S et al. First hospital outbreak of the globally emerging Candida auris in a European hospital. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 5, 35 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Supple L et al. Chlorhexidine only works if applied correctly: use of a simple colorimetric assay to provide monitoring and feedback on effectiveness of chlorhexidine application. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 36, 1095–1097 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner LM, Webb AK, Walters MS, Dudeck MA & Kallen AJ Policies for controlling multidrug-resistant organisms in US healthcare facilities reporting to the National Healthcare Safety Network, 2014. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 37, 1105–1108 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pacilli M et al. Regional emergence of Candida auris in Chicago and lessons learned from intensive follow-up at one ventilator-capable skilled nursing facility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, e718–e725 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams E et al. Candida auris in healthcare facilities, New York, USA, 2013–2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 1816–1824 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lockhart SR et al. Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 64, 134–140 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larkin E et al. The emerging pathogen Candida auris: growth phenotype, virulence factors, activity of antifungals, and effect of SCY-078, a novel glucan synthesis inhibitor, on growth morphology and biofilm formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e02396–16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostrowsky B et al. Candida auris isolates resistant to three classes of antifungal medications—New York, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 69, 6–9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snitkin ES et al. Tracking a hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with whole-genome sequencing. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 148ra116 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishop L et al. Public Health England: Guidance for the Laboratory Investigation, Management and Infection Prevention and Control for Cases of Candida auris v2.0 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/candida-auris-laboratory-investigation-management-and-infection-prevention-and-control (2017).

- 19.Chow NA et al. Tracing the evolutionary history and global expansion of Candida auris using population genomic analyses. mBio 11, e03364–19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases. Screening for Candida auris Colonization https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-screening.html (accessed 29 May 2020).

- 21.Tsay S, Kallen A, Jackson BR, Chiller TM & Vallabhaneni S Approach to the investigation and management of patients with Candida auris, an emerging multidrug-resistant yeast. Clin. Infect. Dis. 66, 306–311 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherry L et al. Biofilm-forming capability of highly virulent, multidrug-resistant Candida auris. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23, 328–331 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore G, Schelenz S, Borman AM, Johnson EM & Brown CS Yeasticidal activity of chemical disinfectants and antiseptics against Candida auris. J. Hosp. Infect. 97, 371–375 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popovich KJ et al. Relationship between chlorhexidine gluconate skin concentration and microbial density on the skin of critically ill patients bathed daily with chlorhexidine gluconate. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 33, 889–896 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Findley K et al. Topographic diversity of fungal and bacterial communities in human skin. Nature 498, 367–370 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raz-Pasteur A, Ullmann Y & Berdicevsky I The pathogenesis of Candida infections in a human skin model: scanning electron microscope observations. ISRN Dermatol. 2011, 150642 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prohic A, Jovovic Sadikovic T, Krupalija-Fazlic M & Kuskunovic-Vlahovljak S Malassezia species in healthy skin and in dermatological conditions. Int. J. Dermatol. 55, 494–504 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu Y et al. Laboratory analysis of an outbreak of Candida auris in New York from 2016 to 2018: impact and lessons learned. J. Clin. Microbiol. 58, e01503–1 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nutman A et al. Detecting carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) carriage: which body site should be cultured? Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 41, 965–967 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang X et al. Murine model of colonization with fungal pathogen Candida auris to explore skin tropism, host risk factors and therapeutic strategies. Cell Host Microbe 29, 210–221 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossow J. et al. Factors associated with Candida auris colonization and transmission in skilled nursing facilities with ventilator units, New York, 2016–2018. Clin. Infect. Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1462 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snitkin ES et al. Integrated genomic and interfacility patient-transfer data reveal the transmission pathways of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a regional outbreak. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaan0093 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prestel C et al. Candida auris outbreak in a COVID-19 specialty care unit—Florida, July–August 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 70, 56–57 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 34.Thurlow CJ et al. Anatomic sites of patient colonization and environmental contamination with Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae at long-term acute care hospitals. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 34, 56–61 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichel M, Heisig P & Kampf G Pitfalls in efficacy testing—how important is the validation of neutralization of chlorhexidine digluconate? Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 7, 20 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kampf G What is left to justify thÿe use of chlorhexidine in hand hygiene? J. Hosp. Infect. 70, 27–34 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welsh RM et al. Survival, persistence, and isolation of the emerging multidrug-resistant pathogenic yeast Candida auris on a plastic health care surface. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55, 2996–3005 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edmiston CE Jr. et al. Preoperative shower revisited: can high topical antiseptic levels be achieved on the skin surface before surgical admission? J. Am. Coll. Surg. 207, 233–239 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Approved Standard—Third Edition (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 40.CLSI. CLSI document M27-A3 (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases (DFWED). Antifungal Susceptibility Testing and Interpretation; https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-antifungal.html (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oh J et al. Biogeography and individuality shape function in the human skin metagenome. Nature 514, 59–64 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khot PD, Ko DL & Fredricks DN Sequencing and analysis of fungal rRNA operons for development of broad-range fungal PCR assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 1559–1565 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fadrosh DW et al. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome 2, 6 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Proctor DM et al. A spatial gradient of bacterial diversity in the human oral cavity shaped by salivary flow. Nat. Commun. 9, 681 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DiGiulio DB et al. Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 11060–11065 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koren S et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 27, 722–736 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaser R, Sovic I, Nagarajan N & Sikic M Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 27, 737–746 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langmead B & Salzberg SL Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walker BJ et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 9, e112963 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data are publicly available in the NIH Short Read Archive under BioProject accession number PRJNA672955. The RefSeq database version 2.0 downloaded on May 2018 and the UNITE ‘sh_general_release_dynamic’ database downloaded on 2 February 2019 were used to assign bacterial and fungal taxonomy, respectively, and can be found at https://github.com/skinmicrobiome/cauris_colonization. Intermediate data files including the OTU table, the taxonomy table and the sample data mapping file are included in Supplementary Data 1.