Abstract

The RpoS sigma factor of enteric bacteria is either required for or augments the expression of a number of genes that are induced during nutrient limitation, growth into stationary phase, or in response to stresses, including high osmolarity. RpoS is regulated at multiple levels, including posttranscriptional control of its synthesis, protein turnover, and mechanisms that affect its activity directly. Here, the control of RpoS stability was investigated in Salmonella typhimurium by the isolation of a number of mutants specifically defective in RpoS turnover. These included 20 mutants defective in mviA, the ortholog of Escherichia coli rssB/sprE, and 13 mutants defective in either clpP or clpX which encode the protease active on RpoS. An hns mutant was also defective in RpoS turnover, thus confirming that S. typhimurium and E. coli have identical genetic requirements for this process. Some current models predict the existence of a kinase to phosphorylate the response regulator MviA, but no mutants affecting a kinase were recovered. An mviA mutant carrying the D58N substitution altering the predicted phosphorylation site is substantially defective, suggesting that phosphorylation of MviA on D58 is important for its function. No evidence was obtained to support models in which acetyl phosphate or the PTS system contributes to MviA phosphorylation. However, we did find a significant (fivefold) elevation of RpoS during exponential growth on acetate as the carbon and energy source. This behavior is due to growth rate-dependent regulation which increases RpoS synthesis at slower growth rates. Growth rate regulation operates at the level of RpoS synthesis and is mainly posttranscriptional but, surprisingly, is independent of hfq function.

In the enteric bacteria, including Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli, the rpoS gene encodes an alternative primary sigma (specificity) factor for RNA polymerase (42, 57). RpoS, which is also called ςS or ς38, has functions related to stress and stationary phase. RpoS is also a virulence factor for S. typhimurium (19). More than 50 target genes show RpoS-dependent increases in expression during various stresses, including nutrient deprivation and growth into stationary phase (for a review, see references 24 and 35). The transcriptional response to each particular stress is apparently tailored by stress- and gene-specific controls. In turn, increased RpoS abundance mediated by these diverse physiological signals is orchestrated in a complex way; evidence has been presented for control of RpoS synthesis at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels (24, 35) as well as control of RpoS turnover through proteolysis mediated by the ClpXP energy-dependent protease (33, 41, 54, 62). Control of RpoS activity has also been demonstrated (47, 62).

Genetic analysis of RpoS turnover in E. coli has implicated several factors in addition to the ClpXP protease. These include the abundant DNA-binding protein H-NS (4, 61) and an orphan two-component response regulator called RssB (41) or SprE (46); the S. typhimurium ortholog of this protein is called MviA (6). The N terminus of RssB/SprE/MviA is highly similar to CheY, including an aspartate residue at position 58 that, by analogy to CheY and other response regulators, is predicted to be phosphorylated and thereby to activate MviA (26). An in vitro study of RssB phosphorylation with acetyl phosphate supports this notion (8). The C terminus of MviA is not like that of any other known protein, consistent with its unique function in proteolysis rather than in DNA binding as for most response regulators. The structure and in vitro phosphate-accepting activity of RssB/SprE/MviA suggest that one or more kinases can phosphorylate MviA in vivo, but none has yet been identified. The studies described here were initiated to search for other factors (such as a kinase) that may be required for RpoS turnover.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and construction.

Strains used in this study are derived from wild-type S. typhimurium LT2 and are shown in Table 1 or Table 2. Our laboratory’s standard LT2 strain was originally obtained from J. Roth. As detailed in Results, this strain is defective in the turnover of RpoS, because the mviA gene of LT2 is nonfunctional. For this reason, we used a closely related mviA+ S. typhimurium strain obtained from W. Benjamin (WB335 [5]) to screen for new mutants affecting the turnover pathway. WB335 was previously designated an avirulent LT2 (5); we will refer to strain WB335 as LT2A in this work.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Strain | Genotype or description | Source (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| LT2 | Wild type | J. Roth |

| NH685 | LT2 hns-1::Kan | P. Higgins (17) |

| PP1228 | ptsI421::Tn10 | K. Sanderson |

| SMS209 | pta-209::Tn10 | T. Van Dyk |

| SMS408 | ack-408::Tn10 | T. Van Dyk |

| TT7608 | PP1002 trpB223 cya::Tn10 | J. Roth, Postma |

| TE7563 | TT17456 metE205 ara-9 cya-961::Tn10 crp*-661 zhc-3729::Tn10d-Cam | J. Roth (1) |

| WB4188 | LT2A mviA::Kan | W. Benjamin |

| XF 272 | orfo186::MudJ | (18) |

| XF 373 | otsA::MudJ | (18) |

| TE545 | zde-6827::Tn10d-Tet | Lab collection |

| TE3288 | cya::Tn10 | P22.TT7608 × LT2 |

| TE3359 | hns-1::Kan | P22.NH685 × LT2 |

| TE4351 | pyrD121 Δ(putPA)521 /F+zzf-6807::Tn10d-put:A1302::Cam | (13) |

| TE5314 | putPA1303::Kanr-hemA-lac [pr] hfq-1::Mud-Cam | (9) |

| TE6144 | putA1302::Cam mviA::Kan | P22.WB4188 × TE2682 |

| TE6153 | putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] | (9) |

| TE6182 | putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] zcc-6802::Tn10d-Tet | This study |

| TE6183 | putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] zcc-6802::Tn10d-Tet hns-1::Kan | P22.TE6182 × TE3372 |

| TE6184 | putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] zcc-6802::Tn10d-Tet mviA::Kan | P22.TE6182 × TE6144 |

| TE6253 | putPA1303::Kanr-rpoS-lac [pr] | (9) |

| TE6266 | putPA1303::Kanr-rpoS-lac [pr] hfq-1::Mud-Cam | P22.TE5314 × TE6253 |

| TE6273 | pyrD121 Δ(putPA)521/F+zzf-6807::Tn10d-putPA1303::Kanr-rpoS-lac [pr] | P22.TE6253 × TE4351 |

| TE6357 | WB335 LT2A | W. Benjamin (5) |

| TE6731 | LT2A mviA::Kan | P22.WB4188 × TE6357 |

| TE6732 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] zcc-6802::Tn10d-Tet mviA::Kan | P22.TE6182 × TE6731 |

| TE6756 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] | P22.TE6153 × TE6357 |

| TE6791 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] mviA21::Tn10d-Cam | This study |

| TE6805 | LT2 clpP::mini-Tn5 | D. W. Holden (25) |

| TE6826 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] zde::Tn10d-Cam | |

| TE6842 | clpP::mini-Tn5 | P22.TE6805 × LT2 |

| TE6861 | LT2A clpP::mini-Tn5 | P22.TE6842 × TE6357 |

| TE6862 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] zcc-6802::Tn10d-Tet clpP::mini-Tn5 | P22.TE6182 × TE6861 |

| TE6919 | putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] zcc-6802::Tn10d-Tet clpP::mini-Tn5 | P22.TE6842 × TE6182 |

| TE7108 | LT2 putPA1303::Kanr-proV-lac [op] | This study |

| TE7109 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] pta-209::Tn10 | P22.SMS209 × TE6756 |

| TE7110 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] ack-408::Tn10 | P22.SMS408 × TE6756 |

| TE7119 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-proV-lac [op] | P22 TE7108 × TE6357 |

| TE7179 | LT2A orfo186::MudJ | P22.XF272 × TE6357 |

| TE7180 | LT2A otsA::MudJ | P22.XF273 × TE6357 |

| TE7182 | LT2A zaj-6826::Tn10d-Tet (90% linked to clpP+) | This study |

| TE7186 | pyrD121 Δ(putPA)521/F+ zzf-6807::Tn10d-putPA1303::Kanr-proV-lac [pr] | P22.TE7108 × TE4351 |

| TE7199 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] mviA22::Tn10d-Cam recA1 | This study |

| TE7382 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] ptsI421::Tn10 | P22.TE4535 × TE6756 |

| TE7387 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] ptsI421::Tn10 mviA22::Tn10d-Cam | P22.TE6851 × TE7382 |

| TE7401 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] mviA22::Tn10d-Cam recA1/pTE570 (Para) | This study |

| TE7402 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] mviA22::Tn10d-Cam recA1/pTE695 (mviA wild type) | This study |

| TE7404 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] mviA22::Tn10d-Cam recA1/pTE695 (mviA D58N) | This study |

| TE7505 | LT2A hns-1::Kan | This study |

| TE7512 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] zcc-6802::Tn10d-Tet hns-1::Kan | P22.TE6182 × TE7505 |

| TE7564 | LT2A cya::Tn10 | P22.TE3288 × TE6357 |

| TE7565 | LT2A cya::Tn10 crp*-661 zhc-3729::Tn10d-Cam | P22.TT17456 × TE7564 |

| TE7579 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-rpoS-lac [pr] | P22.TE6253 × TE6357 |

| TE7585 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-rpoS-lac [pr] hfq-1::Mud-Cam | P22.TE5314 × TE7579 |

| TE7631 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] cya::Tn10 crp*-661 zhc-3729::Tn10d-Cam | P22.TE6153 × TE7565 |

| TE7632 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-proV-lac [op] clpX1::Tn10d-Cam | P22.TE6850 × TE7119 |

| TE7633 | LT2A orfo186::MudJ clpX1::Tn10d-Cam | P22.TE6850 × TE7179 |

| TE7634 | LT2A otsA::MudJ clpX1::Tn10d-Cam | P22.TE6850 × TE7180 |

| TE7636 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] zeg-6815::Tn10d-Tet | This study |

| TE7637 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] zeg-6816::Tn10d-Cam | This study |

| TE7638 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] lrhA::Ω-Cm (PstI) (previously zeg-6821::Ω-Cm) | This study |

| TE7639 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] nuo p14::Ω-Cm | This study |

| TE7640 | LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] lrhA::Ω-Cm (HpaI) | This study |

TABLE 2.

Insertion mutations affecting RpoS turnover

| Strain | Allele | Transposon | Site of insertiona | Orientationb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE6791 | mviA21 | Tn10d-Cam | 631–639 | B |

| TE6850 | clpX1 | Tn10d-Cam | 286–292c | A |

| TE6851 | mviA22 | Tn10d-Cam | 42–50 | A |

| TE6854 | mviA23 | Tn10d-Cam | 491–499 | A |

| TE7066 | mviA24 | Tn10d-Cam | 889–997 | A |

| TE7067 | mviA25 | Tn10d-Cam | 867–875 | B |

| TE7068 | mviA26 | Tn10d-Cam | 867–875 | A |

| TE7069 | mviA27 | Tn10d-Cam | 42–50 | A |

| TE7077 | mviA28 | Tn10d-Cam | 42–50 | B |

| TE7154 | clpX3 | Mud-Cam | NDd | ND |

| TE7155 | mviA29 | Mud-Cam | ND | A |

| TE7156 | clpX2 | Mud-Cam | ND | A |

Sites of transposon insertion are expressed as target base pairs duplicated in the insertion strain, counting from the ATG start codon for each gene. Sites and insertion orientations were determined by DNA sequencing of cloned insertions, except for TE7154 (assigned by a complementation test) and TE7155 and TE7156 (assigned by PCR).

For Tn10d-Cam, orientation A is defined as that in which the cat gene of the Tn10d-Cam element and the gene bearing the insertion are oriented in the same direction; orientation B is the opposite. For Mud-Cam, orientation A is defined as that in which attR is on the upstream side of the insertion.

Only 7 bp of clpX are duplicated in this insertion strain.

ND, not determined.

S. typhimurium wild type does not carry the lac operon. The LT2 and LT2A derivatives used here carry various lac fusions as reporters of gene expression. The katE-lac [op] and rpoS-lac [pr] fusions, where [op] and [pr] indicate operon and protein fusions, respectively, have been described previously (9). These lac fusions are carried in single copy as an insertion of a Kanr promoter gene lac fragment in the put operon (13). The rpoS-lac [pr] fusion used in this study is to codon 73 of rpoS and does not include the segment of the RpoS protein required for turnover (54). The otsA::MudJ and o186::MudJ insertions have also been described previously (18). The proV-lac fusion was constructed by PCR amplification of a fragment of the E. coli proU operon (promoter proximal gene proV) by using primers CGCGA ATTCC CGCCA AATAG CTTTT TATCA C and CGCGG ATCCT GAGAG CAAAT CGAGA AAG, with E. coli W3110 DNA as the template. The amplified segment includes bp 5705 to 5852 of the proU operon (GenBank AE000352) bounded by EcoRI and BamHI sites. It corresponds to a slightly shortened version of the sequence in the lac fusion plasmid pHYD275 (37), that is, bp 377 to 524 according to the authors’ numbering (GenBank accession no. M24856). The proV promoter fragment was cloned into pRS551 (56), and after verification of the DNA sequence, the fusion was converted to a single copy in S. typhimurium as described previously (13).

The pta and ack mutants used in this study have been extensively characterized previously (34, 58), both by genetic mapping and enzyme assay. Both pta and ack mutants grow less well than wild type on acetate (generation times of 2.0 h [wild type], 4.2 h [pta], and 3.5 h [ack] [34]). In E. coli, growth on acetate independent of pta and ack has been shown to require acs function (31), and this is likely true of S. typhimurium as well. The pta and ack mutations were backcrossed into the S. typhimurium LT2A background before use and then characterized for their growth defect in using inositol as the sole carbon and energy source. This defect is severe for ack and absolute for pta mutants (34). Cotransduction tests showed the expected linkage to markers in the nuo region (2), and PCR analysis confirmed the identities of the mutants (primers designed based on the Salmonella typhi sequence).

The crp* allele used in this study was originally isolated by Ailion et al. (1). To study the effect of crp*, a cya::Tn10 insertion was first transduced from PP1002 into LT2A by selection for tetracycline resistance. Both the transduction and subsequent growth were on medium supplemented with glucose. The crp* allele was then transduced from TT17456 by selecting for a tightly linked Tn10d-Cam insertion. The cyclic AMP (cAMP)-independent (Crp*) phenotype of the transductants was scored on MacConkey maltose plates but is also evident from the ability of the resulting strain to grow in minimal acetate medium.

The high-frequency generalized transducing bacteriophage P22 mutant HT105/1 int-201 (53) was used for transduction in S. typhimurium by standard methods (12).

Media and growth conditions.

Bacteria were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (55) or in minimal morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) medium (44) as modified (7) with 0.2% of the indicated compound (glucose, glycerol, sodium pyruvate, or sodium acetate) as the carbon and energy source, with one exception noted in the text. Plates were prepared by using nutrient agar (Difco) with 5 g of NaCl per liter. Antibiotics were added to final concentrations in selective plates as follows: 100 μg of sodium ampicillin/ml, 20 μg of chloramphenicol/ml, 50 μg of kanamycin sulfate/ml, and 20 μg of tetracycline hydrochloride/ml.

Screen for mutants with a defect in RpoS turnover.

For transposon mutagenesis, LT2A was transformed with the plasmid pZT344, which carries the transposon Tn10d-Cam as well as the Tn10 transposase gene at a different site in the plasmid (15). Tn10d-Cam can transpose from pZT344 to the bacterial chromosome; the resulting insertions are stable once they are transferred into a background lacking transposase. Strain TE6756, which is LT2A carrying a katE-lac operon fusion, was employed to screen for mutations affecting RpoS function. TE6756 forms Lac− colonies on MacConkey lactose indicator plates after incubation for 24 h at 37°C. Pooled LT2A cells transformed with pZT344 were used as donors in a phage P22-mediated transductional cross into TE6756. Camr transductants were screened for a Lac+ phenotype. After single colony isolation, all such clones still carried ampicillin resistance derived from pZT344. Therefore, before further use, candidate Lac+ insertions were backcrossed into the TE6756 recipient, and purified colonies were checked to confirm that they were sensitive to ampicillin. This method results in independent insertions in the LT2A chromosome that increase expression of the RpoS-dependent reporter katE-lac [op] fusion. A useful determination of the frequency of Lac+ mutants could not be made, because the rate of plasmid-to-chromosome transposition was not measured; however, in other experiments the frequency of insertion mutants affecting rpoS synthesis in LT-2 is about 0.1%.

Because mutations that increase RpoS synthesis are common and affect multiple genes (data not shown), another transduction step was employed to distinguish such mutants from the desired class affecting RpoS turnover. Candidate insertion strains were used as donors in a transductional cross with two different recipient strains, TE6756 (described above) and TE6153, which is our standard LT2 (mviA mutant) strain carrying the katE-lac [op] fusion. Even though it is an mviA mutant, TE6153 has only a very weak Lac−/+ phenotype on MacConkey lactose plates. Mutations causing turnover defects should not confer a Lac+ phenotype on TE6153, since the mviA mutation in this strain has already eliminated the turnover of RpoS. In contrast, mutants affecting RpoS synthesis would be expected to increase expression of the reporter in both backgrounds. A total of 80 candidate Tn10d-Cam insertion mutants were tested by the second screen. Of these, 9 increased katE-lac expression only in the LT2A background and were studied further (see Results). Another Camr transposon derived from phage Mu (Mud-Cam [14]) was also used to mutagenize TE6756. Ten Mud-Cam insertion mutants were isolated and tested by the second screen. Of these, three increased katE-lac expression only in the LT2A background and were studied further.

Screen for point mutants affecting RpoS turnover.

Chemical mutagenesis was also used to isolate mutants with defective turnover of RpoS. A culture of TE6756 (LT2A katE-lac) was mutagenized with diethyl sulfate (DES) by a standard method (12) and used to grow independent cultures, which were then plated for single colonies to screen for Lac+ clones with elevated expression of the RpoS-dependent katE-lac [op] reporter. Elevated expression of β-galactosidase was then confirmed by enzyme assay. For each independent mutant, the katE-lac reporter was removed by transduction to tetracycline resistance by using a donor phage P22 lysate grown on strain TE2929. This strain carries a Tn10d-Tet insertion 80% linked to the put locus (13). The resulting put+ (fusion-negative) strains were then mated with two different donors, each bearing a lac fusion on an F′ plasmid marked with kanamycin resistance. One donor strain, TE6273, carries the rpoS-lac protein fusion, while the other, TE7186, carries the proV-lac [op] fusion. Assays of β-galactosidase were performed with the resulting exconjugants. DES-induced mutations affecting RpoS turnover are predicted to elevate expression of proV-lac [op] but not of rpoS-lac [pr], because the latter reporter’s expression reflects only changes in RpoS synthesis.

Transduction and complementation tests.

All DES-induced mutations that affect RpoS turnover by the genetic test given above were assigned to genes by cotransduction and complementation tests. A new copy of the katE-lac operon fusion was first introduced into the fusion-negative version of each mutant (see above). Next, cotransduction tests were performed with P22 transducing lysates grown on each of two donor strains, one carrying a Tn10d-Tet insertion about 50% linked to mviA+ (TE545), the other carrying a Tn10d-Tet insertion >90% linked to clp+ (TE7182). With one exception, all mutants tested had defects that mapped to either the mviA or clp region by this test. The exception is briefly discussed in Results. Lesions in the clp region were further assigned by complementation tests with the plasmids pWPC9 (clpP+ clpX+), pWPC21 (clpP+), pWPC16 (clpX+), and pBR322 as a control (38). Lesions in the mviA region were assigned by a complementation test with a tandem duplication of the mviA region. This test was developed by J. Roth and colleagues (49); for a diagram and further explanation of the test, see reference 16. Briefly, strains diploid for the mviA region (and the mutation to be tested) were transduced to chloramphenicol resistance with a phage P22 donor lysate grown on strain TE6851 (mviA22::Tn10d-Cam). In the resulting Camr transductants, one copy of the duplicated region has inherited the mviA::Tn10d-Cam insertion of the donor, while the second copy still carries the original DES-induced mutation. If the DES-induced mutation is an allele of mviA, then both copies of mviA carry mutations, and the resulting colony phenotype will be Lac+. In contrast, if the DES-induced mutation is in another gene tightly linked to mviA, then most Camr transductants will also have repaired the DES-induced lesion in the copy of the duplication containing Tn10d-Cam, with the result that most colonies will have a Lac− (wild-type) phenotype. As a control, the test was also performed with donor phage lysates grown on strain TE6826 (Tn10d-Cam insertion ≈50% linked to mviA+).

Assay of β-galactosidase.

Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in Z buffer (100 mM NaPO4 [pH 7.0], 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4) and then permeabilized by treatment with sodium dodecyl sulfate and chloroform (40). Assays were performed in Z buffer containing 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol by a kinetic method with a plate reader (Molecular Dynamics). Activities (change in optical density at 420 nm [OD420] per min) are normalized to actual cell density (OD650) and were always compared to appropriate controls assayed at the same time. The results shown are from a single experiment; each experiment was repeated several times, with similar results (<15% variation).

Cloning of insertions and sequencing.

Tn10d-Cam insertions together with flanking DNA were cloned by digestion of chromosomal DNA with BglII (for mviA insertions) or PstI (for clp) and ligation of the DNA mixture into pK184 (28) that was digested with BamHI or PstI. The desired clones were selected as Camr transformants, and the insertion sites were sequenced with primers specific to the cat gene (GTTTC TATCA GCTGT CCCTC CTGTT C and GACGA TATGA TCATT TATTC TGCCT C) and, in some cases with vector-specific primers.

Cloning of mviA and construction of pTE695.

The mviA+ gene was isolated from LT2A by PCR with the primers CGCGA ATTCC ATATG ACGCA GCCAT TGGTC GGAAA AC and CGCGG ATCCT TATTC TGCAG ACAAC ATCAA GCGCA GTCGA C. These primers are derived from the E. coli sequence and introduce some changes to the S. typhimurium gene that are silent with respect to the amino acid sequence. The mviA gene was first cloned into pK184 and subsequently inserted as an NdeI-BamHI fragment into pTE571 (9), which is a derivative of pBAD18 (21). Site-directed mutants of the mviA D58 codon were constructed as described previously (10). The sequence of the mviA gene from LT2 was determined from the appropriate PCR product (Biotech Core, Palo Alto, Calif.).

Western (immunoblot) and immunoprecipitation analysis.

Cultures were grown as described in the text to an OD600 of 0.4. Electrophoresis and transfer were as described previously (9), except that detection was with tissue culture supernatant containing an anti-RpoS monoclonal antibody (R12), which is of the γ2a isotype. The secondary reagent was biotinylated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) (Southern Biotechnology); subsequent chemiluminescence detection steps were as described previously (9). For immunoprecipitation, cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.4 and then labeled for 1 min with 100 μCi of Tran35S-label l-[35S]methionine and l-[35S]cysteine (ICN), and labeled proteins were prepared as described previously (3, 27). Immunoprecipitation was performed with the R12 monoclonal antibody (MAb) and protein A-Sepharose beads (Sigma).

RESULTS

Isolation of mutants with defects in RpoS turnover.

A katE-lac [op] fusion was used as the reporter to screen for new mutations affecting RpoS turnover in S. typhimurium. Mutants with elevated RpoS show increased transcription of katE-lac and can be visualized as Lac+ clones on MacConkey lactose indicator plates. Both transposon and chemical mutagenesis were employed, as described in more detail in Materials and Methods. The screens were complicated by the finding that mutations which increase RpoS synthesis are common and affect multiple genes (data not shown). Therefore, in the transposon mutagenesis, we first screened for elevated expression of katE-lac in the LT2A background and then eliminated insertions that also elevated expression of katE-lac after transduction into our standard LT2 background. As discussed below, others have reported (6), and we have confirmed, that LT2 is an mviA mutant and defective for RpoS turnover. Mutants affecting RpoS turnover are predicted to have the parental Lac phenotype in LT2 bearing katE-lac, since the turnover pathway is already defective. In contrast, mutants causing increased RpoS synthesis should show increased katE-lac expression in both LT2 and LT2A backgrounds. A total of 90 mutants arising by insertion of Tn10d-Cam and Mud-Cam were tested; 12 of these passed the second screen and were studied further (Table 2). DNA sequencing and PCR tests showed that 3 are alleles of clpX and 9 are alleles of mviA. No new genes were identified in this experiment.

A different screen was used after chemical mutagenesis of the LT2A katE-lac strain, since backcrossing the individual (unmapped) mutations was not feasible. Mutants with elevated lac expression, which had been confirmed by assay of β-galactosidase, were cured of the katE-lac fusion by transduction with a linked Tn10d-Tet (see details in Materials and Methods). Different reporter fusions were then introduced on F′ plasmids. One plasmid carries proV-lac [op], a second RpoS-dependent reporter fusion. This is an artificial construct which contains only the P1 promoter of the E. coli proU operon. Another F′ plasmid carries an rpoS-lac [pr] fusion (9) which reports changes in RpoS synthesis but not its turnover. Of 45 DES-induced mutants showing elevated katE-lac expression, 22 passed the second screen. These new mutants showed a range (1.5-fold to 4-fold) of increase in katE-lac and proV-lac, but no increase in rpoS-lac expression. Those mutants showing smaller increases may be only partially defective. The mutants were mapped by cotransduction and then assigned to genes by complementation tests as described in Materials and Methods. Seven are alleles of clpP, 3 are alleles of clpX, and 11 (half) are alleles of mviA. No new genes were identified. (We note that one of these DES-induced mutants has so far resisted characterization by our standard methods, i.e., we have failed in repeated attempts to isolate a linked transposon insertion or to move it to a new strain.) To summarize, of 135 new mutants with increased katE-lac expression, 32 specifically affect RpoS turnover. These include 20 mviA, 7 clpP, and 6 clpX alleles. However, we note that the screen does not seem to be saturated, because no alleles of hns were found by these methods (see below).

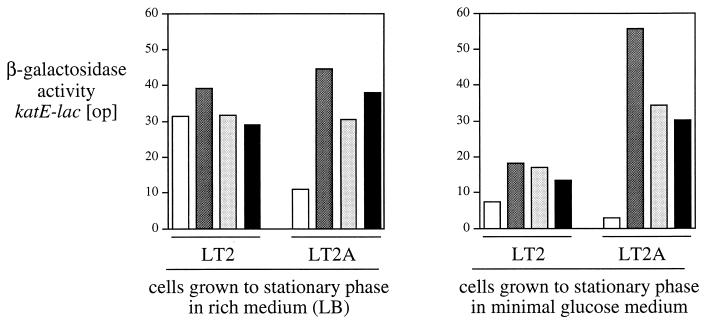

Mutations known to affect expression of katE-lac in E. coli.

We also tested mutations in the S. typhimurium counterparts to genes previously shown to affect RpoS turnover in E. coli. Derivatives of both LT2 and LT2A were constructed that carry the RpoS-dependent katE-lac reporter as well as insertion mutations disrupting the mviA, clpP, and hns genes. Expression of katE-lac was not changed by any of these mutations in the standard wild-type LT2 strain background during growth to stationary phase in rich medium (Fig. 1, left panel). In contrast, when any one of these mutations was present in LT2A, a three- to fourfold increase in expression of the reporter was observed under the same conditions. For the mviA and clpP mutants, introduction of an rpoS null allele reduced katE-lac expression to <3% of the level seen in the rpoS+ parent; for the hns mutant, the rpoS-independent expression was about 10% (data not shown). We conclude that our laboratory strain of LT2 is defective for the RpoS turnover pathway and that LT2A contains a functional pathway. We mapped the LT2 defect to the mviA region by cotransduction tests; the mutation was confirmed to be the V102G allele described for a closely related LT2 strain, WB600 (5, 6). Because the hns and mviA genes are tightly linked, it was important to show that strain TE7512 (LT2A hns::Kan) is mviA+.

FIG. 1.

Testing mutations predicted to affect RpoS turnover for their effect on expression of a katE-lac [op] reporter. Cultures were grown overnight to stationary phase in LB medium (left panel) or minimal MOPS medium, with 0.2% glucose as the source of carbon and energy (right panel). The activity of β-galactosidase was assayed as described in Materials and Methods and is reported in arbitrary units. Strains have LT2 or LT2A backgrounds as indicated and are either wild type (white bar), mviA::Kan (dark gray bar), clpP::mini-Tn5 (light gray bar), or hns::Kan (black bar).

When cultures of the same strains were grown overnight to stationary phase in minimal glucose medium, the effect of the mviA, clpP, and hns mutations on katE-lac expression in LT2A was amplified (Fig. 1, right panel), primarily because of a decrease in expression in the wild type. In this medium, the effect of the mviA mutation was somewhat larger than that of clpP; this may be due to sequestration of RpoS away from core RNA polymerase by MviA, as suggested previously (62). A modest effect of each mutation can also be seen in the LT2 background for growth in minimal glucose medium, suggesting that the mviA allele of LT2 may allow some function of the turnover pathway under these conditions. Finally, we assayed katE-lac expression in LT2A wild-type and mviA mutant strains during exponential growth in LB medium at an OD600 of 0.3. Each of these two strains showed similar (high) induction ratios in a comparison of expression during exponential growth to that observed in stationary phase (11-fold and 8-fold, respectively).

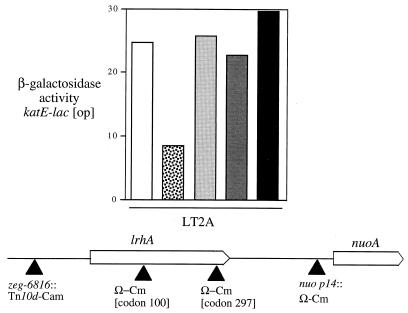

Role of lrhA in RpoS turnover.

Very recently, evidence has been obtained with E. coli for the involvement of lrhA in RpoS turnover (20). This gene lies immediately upstream of and is transcribed toward the nuo operon encoding the 14-subunit energy-conserving NADH dehydrogenase. (The next characterized open reading frames [ORFs] comprise the ack-pta operon, which lies about 6 kb upstream of lrhA and is divergently transcribed.) Gibson et al. found that an lrhA null mutation was as effective as an sprE/rssB null mutation in elevating RpoS levels in E. coli. They also found that constitutive and, likely, overexpression of lrhA due to a transposon insertion 349 bp upstream of lrhA resulted in hyperactive RpoS turnover, a phenotype that requires both SprE/RssB and ClpXP function. We tested the role of lrhA in S. typhimurium, using several transposon and interposon insertions isolated in a previous study (2), including an lrhA::Ω-Cm insertion at codon 100 of this 313-codon gene. No effect was seen for this presumed null allele of lrhA, either with katE-lac (Fig. 2) or with any of three other RpoS-dependent reporter fusions (data not shown). However, a threefold decrease in expression of the RpoS-dependent katE-lac reporter was seen for the zeg-6816::Tn10d-Cam insertion, which lies 379 bp upstream of the lrhA ATG codon. This is consistent with the hyperturnover phenotype observed for the similarly positioned insertion in E. coli (20). An mviA null mutation was epistatic to zeg-6816::Tn10d-Cam (data not shown). We conclude that loss of LrhA does not affect RpoS turnover in S. typhimurium during growth in LB medium but that its overexpression may do so.

FIG. 2.

Expression of katE-lac [op] in strains carrying mutations in the lrhA region. All strains are LT2A containing katE-lac [op]: TE6756 (wild type) (white bar), TE7637 (zeg-6816::Tn10d-Cam) (speckled bar), TE7640 (lrhA::Ω-Cm [codon 100]) (light gray bar), TE7638 (lrhA::Ω-Cm [codon 297]) (dark gray bar), and TE7639 (nuo p14::Ω-Cm) (black bar). Cultures were grown to stationary phase in LB medium, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. The map (bottom) shows the position of each insertion relative to the lrhA and nuoA genes.

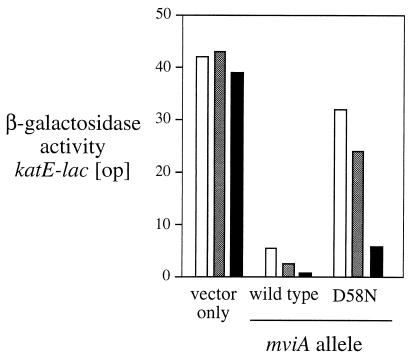

Role of phosphorylation in activation of MviA.

The aspartate residue at position 58 of MviA (D58) is predicted to be the phosphorylation site based on experiments with CheY (50) and other response regulators, such as NtrC (30, 51). Studies with these proteins also lead us to predict that the mutant MviA D58N protein should be nonphosphorylated, and consequently this protein will function poorly or not at all. We constructed derivatives of the plasmid pBAD18 (21) that express wild-type S. typhimurium mviA or its D58N mutant derivative and tested the function of these genes as described in the legend to Fig. 3. In the absence of the inducer arabinose, the PBAD promoter is partially active (e.g., reference 22). At this level of expression, the wild-type MviA protein gives wild-type (i.e., inhibited) levels of expression of the katE-lac reporter, whereas the D58N mutant protein is defective. Since MviA D58N functions poorly, D58 phosphorylation is likely required for wild-type activity. When arabinose was added to increase transcription from the PBAD promoter, both versions of MviA showed increased activity, although D58N did not function as well as the wild type.

FIG. 3.

Complementation of an mviA insertion mutant by plasmids carrying wild-type mviA or a mutant (D58N) affecting the predicted phosphorylation site. Strains analyzed were derivatives of TE7199 (S. typhimurium LT2A putPA1303::Kanr-katE-lac [op] mviA22::Tn10d-Cam recA1) containing the following plasmids: vector (pTE570), wild-type mviA (pTE695), and mviA D58N (pTE695 D58N). Cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.3 in minimal MOPS medium with 0.2% glucose, 50 μg of ampicillin/ml, and the indicated amount of arabinose (white bars, none; light gray bars, 0.02%; black bars, 0.2%) Activity of β-galactosidase was assayed as described in Materials and Methods.

A recent study of RpoS regulation in E. coli suggested a role for acetyl phosphate in controlling RpoS turnover (8). In E. coli and S. typhimurium, the pta and ack genes are required for synthesis of acetyl phosphate from acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) and from acetate, respectively (31, 34). B. Wanner and colleagues originally proposed a model in which acetyl phosphate controls the phosphorylation state of the response regulator PhoB, but only in the absence of PhoR, its cognate histidine kinase/phosphatase (59). Subsequent work suggests that acetyl phosphate is not the immediate phosphate donor in the Pho system in vivo (29, 39), though it and other high-energy phosphate compounds can serve as donors in vitro for many response regulators, including the MviA ortholog, RssB (8). Bouche et al. found that a deletion mutant of pta-ack showed a threefold increase in the half-life of RpoS protein in E. coli. They suggested that acetyl phosphate, whose formation from glucose requires the Pta protein, might normally donate its phosphate to RssB/MviA to activate it in vivo. To test the role of acetyl phosphate in S. typhimurium, we obtained well-characterized ack and pta insertion mutations and looked for effects on katE-lac expression. No effect of these mutations was seen after growth to stationary phase in the following four different minimal media: glucose, glycerol, pyruvate, and acetate (Fig. 4 and data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Testing mutants defective in acetyl phosphate metabolism for expression of an RpoS-dependent reporter. All strains are LT2A derivatives that contain the reporter fusion katE-lac [op]: TE6756 (wild-type) (white bars), TE6850 (clpX1::Tn10d-Cam) (dark gray bars), TE6851 (mviA22::Tn10d-Cam) (speckled bars), TE7109 (pta-209::Tn10) (black bars), and TE7110 (ack-408::Tn10) (light gray bars). Cultures were grown overnight to stationary phase in minimal MOPS medium containing 0.2% glucose, pyruvate, or acetate as indicated, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as described in Materials and Methods.

The rationale for the use of different carbon and energy sources in this experiment is that the source of precursor to acetyl phosphate is medium dependent. Specifically, a pta mutant has very low acetyl phosphate during growth on glucose or pyruvate but high acetyl phosphate during growth on acetate. An ack mutant shows the reverse pattern. (See Discussion and Fig. 1 in reference 59.) An alternative pathway via acetyl CoA synthetase allows acetate to be utilized, even without pta and ack function (31). The experiment as performed here (Fig. 4) is complicated by the polarity of the ack insertion on pta (58), so that the ack::Tn10 mutant should have low acetyl-phosphate under all conditions. Nevertheless, pta insertion mutants (which do not affect ack expression) should have the predicted pattern of low acetyl phosphate during growth on glucose and high acetyl phosphate during growth on acetate. We found that in conditions under which other mutations in the turnover pathway (clpX, mviA) have large effects on expression of the RpoS-dependent reporter katE-lac, there is no discernible effect of a pta or ack mutation.

In a separate experiment, we also tested the possibility that the PTS system (a promiscuous phosphate donor) might be responsible for production of MviA-P. To do this, a ptsI insertion mutant and a double mutant defective in both ptsI and mviA were examined (Fig. 5). Expression of katE-lac was assayed in cells grown to exponential phase in minimal galactose medium, which can support the growth of the ptsI mutant. In this medium, loss of mviA function leads to a 5.5-fold increase in katE-lac expression in the ptsI mutant background compared to a fourfold increase in the ptsI+ background. We conclude that inactivating the PTS system does not interfere with MviA function. In summary, we find no evidence supporting the general class of models in which a low-molecular-weight phosphate donor activates MviA in vivo.

FIG. 5.

Testing the effect of a ptsI mutant on expression of an RpoS-dependent reporter. All strains are LT2A derivatives that contain the reporter fusion katE-lac [op]: TE6756 (wild type) (white bars), TE6851 (mviA22::Tn10d-Cam) (dark gray bars), TE7382 (ptsI421::Tn10) (light gray bars), and TE7387 (ptsI421::Tn10 mviA22::Tn10d-Cam) (black bars). Cultures were grown overnight to stationary phase in minimal MOPS medium, with 0.2% galactose as the source of carbon and energy, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as described in Materials and Methods.

However, these experiments do show a strong effect of the growth medium on katE-lac expression. This effect (fivefold according to a comparison of growth in minimal glucose to minimal acetate medium) was independent of the turnover pathway, since it was also observed in mviA and clpX mutants. The remainder of this paper examines the role of acetate and growth rate in regulation of RpoS and explores the mechanism of this effect.

Induction of RpoS during growth in acetate.

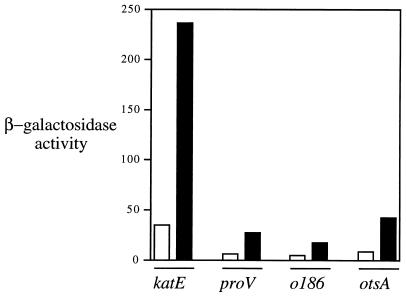

We first tested whether the apparent effect of growth in acetate on RpoS function was reporter specific. To do this, expression of katE-lac was compared with that of three other RpoS-dependent reporters. The proV-lac fusion is strongly dependent on RpoS function for its expression in both E. coli and S. typhimurium (37 and data not shown). The other lac fusions employed were formed by insertion of the transposon MudJ in otsA and ORF o186; these were isolated and characterized previously for their dependence on RpoS (18). Each of the four reporters was studied in a strain derived from LT2A that also carries an insertion in clpX to knock out the RpoS turnover pathway. The presence of the clpX mutation magnifies the signal from each reporter and ensures that the observed regulation is not due to effects on RpoS turnover. Each reporter strain showed five- to sixfold-higher expression of β-galactosidase after overnight growth to stationary phase in minimal acetate medium compared with growth in minimal glucose (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Expression of four different RpoS reporter fusions in cells grown on glucose or acetate as the sole carbon and energy source. All strains are LT2A containing the clpX1::Tn10d-Cam insertion as follows: TE6850 (katE-lac [op]), TE7632 (proV-lac [op]), TE7633 (orfo186::MudJ), and TE7634 (otsA::MudJ). Cultures were grown overnight to stationary phase in minimal MOPS medium containing glucose (white bars) or acetate (black bars), and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as described in Materials and Methods.

Cultures were also grown in a mixture of compounds. Significantly, no induction was observed when cells were grown in medium containing both glycerol and acetate, and only a modest (50%) increase in expression was observed in medium containing both glucose and acetate. These findings argue that induction by acetate does not occur by an uncoupling effect (i.e., dissipation of the proton motive force), at least in S. typhimurium (43, 52).

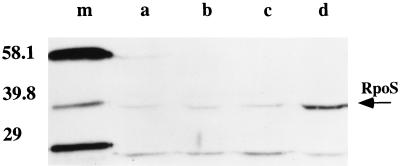

Western blot analysis of RpoS protein from exponential-phase cultures of strain LT2A showed that the RpoS level is elevated during growth in acetate, while the RpoS level during growth in glycerol or pyruvate is comparable to that seen in glucose (Fig. 7). Laser densitometry analysis of this blot shows a fivefold increase in RpoS protein during growth in acetate. Pulse-labeling of exponential-phase cultures of LT2A, followed by immunoprecipitation of RpoS with a specific monoclonal antibody (9), showed a 2.5- to 3.5-fold increase in RpoS synthesis during growth in acetate compared to glucose (Fig. 8). The increase in RpoS synthesis seen by pulse-labeling is somewhat less than predicted based on assays of β-galactosidase in the reporter lac fusion strains and Western blot analysis of RpoS. The source of this discrepancy is not clear. Nevertheless, these results strongly support a control of RpoS activity acting mainly at the level of its synthesis during growth on acetate as a carbon and energy source. This control is manifest during both exponential growth and stationary phase. This general result was also confirmed by study of rpoS-lac fusions (see below).

FIG. 7.

Western (immunoblot) analysis of RpoS abundance during growth on different carbon sources. The arrow indicates RpoS protein. Cultures of TE6357 (LT2A) were grown to exponential phase (OD600 = 0.4) in minimal MOPS medium with 0.2% of each of the following compounds as the carbon and energy source: (a) glucose, (b) glycerol, (c) pyruvate and (d) acetate. Lane (m), molecular mass markers (with sizes as indicated, in kilodaltons).

FIG. 8.

Pulse-labeling and immunoprecipitation of RpoS. Cultures were grown in minimal MOPS medium with 0.2% glucose (lanes a and b) or 0.2% acetate (lanes c and d) to an OD600 of 0.4, pulse-labeled with l-[35S]methionine and l-[35S]cysteine for 1 min, and then immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal anti-RpoS antibody. The samples analyzed in lanes b and d received unlabeled methionine and cysteine and were chased for 20 min. The strain used was TE6357 (S. typhimurium LT2A).

Growth rate regulation of RpoS that is independent of hfq function.

At least three general mechanisms might explain the observed regulation. CRP-mediated transcription or repression might regulate some unknown regulator of RpoS, in a manner dependent on very high levels of cAMP, as would be achieved during growth in acetate. Alternatively, RpoS might respond to an acetate-specific regulator such as FadR or IclR. Finally, RpoS might be responsive to growth rate but not to the carbon source per se. The level of cAMP and the presence of a cya mutation were previously reported to affect RpoS expression in E. coli (32), although the reported effect was negative rather than positive as predicted by this model. Since crp and cya mutants are unable to grow with acetate as their sole carbon and energy source, we tested the model by examining a crp* strain, which is predicted to have inappropriately high expression of RpoS during growth in glucose. We compared expression of the katE-lac reporter fusion in strain TE6756 (LT2A, otherwise wild-type) with that in strain TE7631 (LT2A cya::Tn10 crp*) during exponential growth in both glucose and acetate. These two strains did not show significant differences in katE-lac expression in the same medium, and both showed equivalent acetate induction (data not shown). We conclude that CRP does not play an important role in the acetate regulation of RpoS in S. typhimurium.

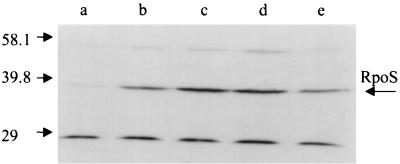

Growth rate-dependent regulation is defined by a difference in gene expression evident from a comparison of growth in two media made with identical ingredients but having a variable concentration of one component to support growth at different rates. Growth rate restriction can be achieved by limiting the transport of any essential nutrient, often the carbon source. It was reported previously that cultures of E. coli grown in a chemostat with limiting glucose exhibit elevated expression of an RpoS-dependent reporter (osmY-lac), and their unpublished Western (immunoblot) analysis shows elevated RpoS protein (45). We imposed a restriction on S. typhimurium growing with glucose as the carbon and energy source by adding different concentrations of α-methylglucoside as a competitive inhibitor of glucose transport (23, 60). Cells whose growth was restricted to different degrees by the inhibition of glucose uptake showed an induction of rpoS-lac and RpoS protein corresponding to the restriction in growth rate (Fig. 9 and Table 3). When the growth rate obtained was comparable to that observed during unrestricted growth on acetate, the expression of rpoS-lac and the level of RpoS were also comparable to those seen in cells growing on acetate. These results confirm that RpoS is growth rate regulated.

FIG. 9.

Western (immunoblot) analysis of RpoS abundance during growth on glucose restricted by α-methylglucoside. Samples analyzed here were obtained from the same cultures as those analyzed in the experiment whose results appear in Table 3. The single arrow at the right indicates native RpoS protein. Cultures of TE7579 (LT2A rpoS-lac [pr]) were grown to exponential phase (OD600 = 0.3) in minimal MOPS containing 2 mM glucose as the carbon and energy source and supplemented with no addition (a), or with 40 mM (b), 80 mM (c), or 120 mM (d) α-methylglucoside. The same strain was also grown in minimal MOPS containing 0.2% acetate as the carbon and energy source (e). The positions of molecular mass markers run on the same gel are also shown (with sizes as indicated, in kilodaltons).

TABLE 3.

Effect of growth rate on expression of rpoS-lac [pr]a

| Carbon sourceb | α-Methylglucoside concn (mM) | Doubling time (min) | β-Galactosidase activityc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 0 | 50 | 39 |

| Glucose | 40 | 68 | 56 |

| Glucose | 80 | 92 | 102 |

| Glucose | 120 | 120 | 157 |

| Acetate | 0 | 109 | 180 |

Strain TE7579 (LT2A rpoS-lac [pr]), grown to an OD600 of 0.3.

Glucose was present at 0.036% (2 mM). This amount of glucose supports growth at the same rate as that observed with 0.2%. Acetate was present at 0.2%. The growth of all cultures was exponential.

β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods.

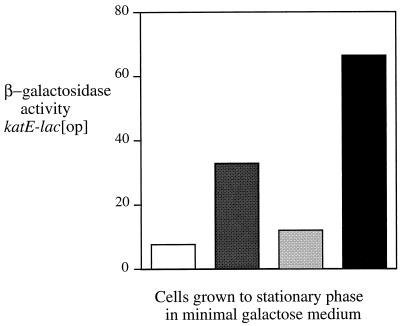

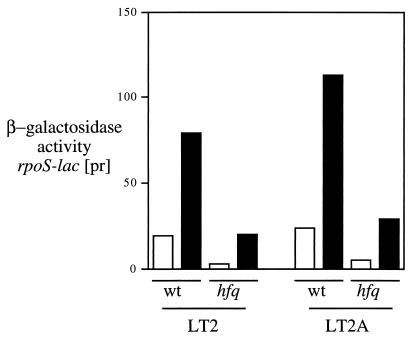

We also studied the expression of a series of derivatives of an rpoS-lac protein fusion during exponential growth in minimal glucose and acetate media. Both the LT2 and LT2A backgrounds were used. The wild-type rpoS-lac [pr] fusion (which reports only control of RpoS synthesis) showed a fourfold increase (LT2) or a five- to sixfold increase (LT2A) in expression during growth in acetate (Fig. 10). Surprisingly, and in contrast to most previously studied methods of induction of RpoS synthesis, this increase during growth in acetate was independent of hfq function. In fact, in the LT2 background, the hfq mutant displayed a larger induction during growth in acetate (sevenfold) than was seen with the wild type. Finally, constructs bearing substitutions of the Ptac promoter for the native rpoS promoters (11) retained induction levels substantially like that of the parent (data not shown), suggesting a role for posttranscriptional regulation.

FIG. 10.

Expression of rpoS-lac [pr] in cells grown in minimal MOPS medium containing 0.2% glucose (white bars) or acetate (black bars). Strains were as follows: TE6253 (LT2 rpoS-lac [pr], TE6266 (LT2 rpoS-lac [pr] hfq::Mud-Cam), TE7579 (LT2A rpoS-lac [pr]), TE7585 (LT2A rpoS-lac [pr] hfq::Mud-Cam). Cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.4, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

The initial objective of this study was to isolate mutants defective in the genes required for RpoS turnover in S. typhimurium, with the goal of understanding how the activity of this pathway is regulated in response to carbon starvation and osmotic challenge. The structure of the response regulator RssB/MviA and its ability to be phosphorylated in vitro by acetyl phosphate suggest that, as for other response regulators (26), MviA-P is the active form of the protein in vivo. Since virtually all response regulators are members of a two-component team, we would expect the genetic analysis to identify mutants defective in the cognate histidine kinase that acts on MviA. Such mutants should have a phenotype similar to that of an mviA mutant. However, our studies with S. typhimurium did not reveal any mutants lacking an MviA kinase, and previous studies with E. coli did not reveal any candidates. The mutant hunt was substantial, although clearly not exhaustive, since mutations in one gene shown to function in the pathway, hns, were not recovered. Of course, kinase mutants may exist but have escaped recovery or detection.

Although our results do not compel it, we suggest that other models of MviA action should be considered to account for the absence of mutations affecting a histidine kinase. Failure to obtain these might have several causes. One possibility is that MviA is active without being phosphorylated in vivo. To test this model, we constructed a mutant mviA gene encoding MviA D58N, which replaces aspartic acid with asparagine at the predicted phosphorylation site. This mutant protein is substantially defective in vivo in a complementation test. In another model MviA is directly phosphorylated by a small molecule such as acetyl phosphate or by a promiscuous phosphate donor such as a component of the PTS, circumventing the need for a dedicated MviA kinase. A role for acetyl phosphate has been proposed previously in E. coli based on a two- to threefold increase in RpoS half-life in strains defective in acetyl phosphate synthesis (8). We tested the acetyl phosphate model in S. typhimurium, using well-defined pta and ack mutants, but obtained no evidence to support it. S. typhimurium and E. coli may differ in this respect. However, it should be noted that neither the genes covered by the deletion nor the position of the linked Tn10 employed in the E. coli study are known (8), and no complementation test of the deletion mutant was performed.

Another model invokes a single kinase with multiple substrates. In this case, mutants defective in the kinase might not survive because its second substrate has an essential function, or the kinase mutants might not pass our screen if kinase activity also negatively controls the synthesis of RpoS. No response regulator controlling RpoS synthesis is envisioned currently, and this general class of models seems unlikely.

Third, there might be multiple kinases whose functions are redundant. If so, then a single mutant affecting only one kinase would have a wild-type or nearly-wild-type phenotype. A problem with the two-kinase model is that induction of RpoS protein stabilization should require the simultaneous inhibition of both kinases, so what advantage such an arrangement would have for the cell is not clear. The simplest solution, and one with a precedent in the enteric bacteria, is to imagine a single dedicated kinase, whose associated phosphatase activity normally prevents inappropriate activation of MviA by another kinase. More complex models can be imagined, with two kinases, for example (whether dedicated to MviA or not), and regulation exerted by control of MviA abundance. There might be a protein analogous to CheZ that promotes dephosphorylation of MviA or a protein that interferes with the formation of the postulated MviA-RpoS complex by binding to MviA. MviA phosphorylation might be required for its activity even though regulation is exerted through another type of modification (e.g., by acetylation [48]). Such models would be novel for two-component systems of enteric bacteria but familiar to those working with other bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis.

In the course of these studies, we have confirmed and extended the findings of a previous study which indicated that RpoS is growth rate regulated (45). Here, we observed a fivefold elevation in RpoS synthesis during growth with acetate as the sole carbon and energy source compared to the basal level obtained with several other carbon sources, including glucose, glycerol, and pyruvate. Actually, it has been known for some time that catalase HPII, the product of katE, is increased in cells growing on trichloroacetic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates and acetate (36). Previous work with E. coli has implicated acetate but also other nonmetabolized weak acids such as benzoate in the induction of RpoS synthesis (43, 52). The addition of acetate had little effect on RpoS in glucose medium and none in glycerol medium, in contrast to experiments with E. coli. This result suggested that carbon and energy restriction, rather than some other effect of acetate, is responsible for RpoS induction.

The finding of high RpoS during growth on acetate led to an experiment showing that RpoS levels are also sharply elevated (up to fivefold) during exponential growth in cells whose growth rate is limited by slow transport of glucose. This suggests that acetate regulation is actually a specific manifestation of a generalized growth rate-dependent regulation. Based on analysis of lac fusions, the regulation acts not on RpoS turnover but on its synthesis and occurs mainly at the posttranscriptional level. The two most notable features of growth rate-dependent regulation of RpoS are that (i) it occurs in exponentially (albeit slowly)-growing cells rather than in shocked or stationary-phase cells and (ii) it is independent of the Hfq protein required for most previously described posttranscriptional regulation of RpoS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM40403.

We are grateful to the individuals listed in Table 1 for providing bacterial strains and acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Sandy Wilson for conducting the experiments shown in Fig. 9 and Table 3.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ailion M, Bobik T A, Roth J R. Two global regulatory systems (Crp and Arc) control the cobalamin/propanediol regulon of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7200–7208. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7200-7208.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archer C D, Elliott T. Transcriptional control of the nuo operon which encodes the energy-conserving NADH dehydrogenase of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2335–2342. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2335-2342.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archer C D, Wang X, Elliott T. Mutants defective in the energy-conserving NADH dehydrogenase of Salmonella typhimurium identified by a decrease in energy-dependent proteolysis after carbon starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9877–9881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barth M, Marschall C, Muffler A, Fischer D, Hengge-Aronis R. Role for the histone-like protein H-NS in growth phase-dependent and osmotic regulation of ςS and many ςS-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3455–3464. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3455-3464.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin W H, Jr, Yother J, Hall P, Briles D E. The Salmonella typhimurium locus mviA regulates virulence in ItyS but not ItyR mice: functional mviA results in avirulence; mutant (nonfunctional) mviA results in virulence. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1073–1083. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamin W H, Jr, Wu X, Swords W E. The predicted amino acid sequence of the Salmonella typhimurium virulence gene mviA+ strongly indicates that MviA is a regulator protein of a previously unknown S. typhimurium response regulator family. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2365–2367. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2365-2367.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bochner B R, Ames B N. Complete analysis of cellular nucleotides by two-dimensional thin layer chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:9759–9769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouche S, Klauck E, Fischer D, Lucassen M, Jung K, Hengge-Aronis R. Regulation of RssB-dependent proteolysis in Escherichia coli: a role for acetyl phosphate in a response-regulator controlled process. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:787–795. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown L, Elliott T. Efficient translation of the RpoS sigma factor in Salmonella typhimurium requires host factor I, an RNA-binding protein encoded by the hfq gene. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3763–3770. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3763-3770.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown L, Elliott T. Mutations that increase expression of the rpoS gene and decrease its dependence on hfq function in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:656–662. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.656-662.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunning C, Brown L, Elliott T. Promoter substitution and deletion analysis of upstream region required for rpoS translational regulation. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4564–4570. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4564-4570.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis R W, Botstein D, Roth J R. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott T. A method for constructing single-copy lac fusions in Salmonella typhimurium and its application to the hemA-prfA operon. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:245–253. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.245-253.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott T. Transport of 5-aminolevulinic acid by the dipeptide permease in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:325–331. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.2.325-331.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott T, Roth J R. Characterization of Tn10d-Cam: a transposition-defective Tn10 specifying chloramphenicol resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;213:332–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00339599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott T, Wang X. Salmonella typhimurium prfA mutants defective in release factor 1. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4144–4154. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4144-4154.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falconi M, McGovern V, Gualerzi C, Hillyard D, Higgins N P. Mutations altering chromosomal protein H-NS induce mini-Mu transposition. New Biol. 1991;3:615–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang F C, Chen C Y, Guiney D G, Xu Y. Identification of ςS-regulated genes in Salmonella typhimurium: complementary regulatory interactions between ςS and cyclic AMP receptor protein. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5112–5120. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5112-5120.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang F C, Libby S J, Buchmeier N A, Loewen P C, Switala J, Harwood J, Guiney D G. The alternative ς factor KatF (RpoS) regulates Salmonella virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11978–11982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibson K E, Silhavy T J. The LysR homolog LrhA promotes RpoS degradation by modulating activity of the response regulator SprE. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:563–571. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.563-571.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzman L M, Belin D, Carson M J, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haldimann A, Daniels L L, Wanner B L. Use of new methods for construction of tightly regulated arabinose and rhamnose promoter fusions in studies of the Escherichia coli phosphate regulon. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1277–1286. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1277-1286.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen M T, Pato M L, Molin S, Fiil N P, von Meyenberg K. Simple downshift and resulting lack of correlation between ppGpp pool size and ribonucleic acid accumulation. J Bacteriol. 1975;122:585–591. doi: 10.1128/jb.122.2.585-591.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hengge-Aronis R. Regulation of gene expression during entry into stationary phase. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1497–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hensel M, Shea J E, Gleeson C, Jones M D, Dalton E, Holden D W. Simultaneous identification of bacterial virulence genes by negative selection. Science. 1995;269:400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.7618105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ito K, Bassford P J, Beckwith J. Protein localization in E. coli: is there a common step in the secretion of periplasmic and outer-membrane proteins? Cell. 1981;24:707–717. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jobling M G, Holmes R K. Construction of vectors with the p15a replicon, kanamycin resistance, inducible lacZα and pUC18 or pUC19 multiple cloning sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5315–5316. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.5315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S K, Wilmes-Tiesenberg M R, Wanner B L. Involvement of the sensor kinase EnvZ in the in vivo activation of the response-regulator PhoB by acetyl phosphate. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:135–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klose K E, Weiss D S, Kustu S. Glutamate at the site of phosphorylation of nitrogen-regulatory protein NtrC mimics aspartyl-phosphate and activates the protein. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:67–78. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumari S, Tishel R, Eisenbach M, Wolfe A J. Cloning, characterization, and functional expression of acs, the gene which encodes acetyl coenzyme A synthetase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2878–2886. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2878-2886.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. Identification of a central regulator of stationary-phase gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. The cellular concentration of the ςS subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli is controlled at levels of transcription, translation and protein stability. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1600–1612. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.13.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LeVine S M, Ardeshir F, Ames G F L. Isolation and characterization of acetate kinase and phosphotransacetylase mutants of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:1081–1085. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.1081-1085.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loewen P C, Hu B, Strutinsky J, Sparling R. Regulation in the rpoS regulon of Escherichia coli. Can J Microbiol. 1998;44:707–717. doi: 10.1139/cjm-44-8-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loewen P C, Switala J, Triggs-Raine B L. Catalases HPI and HPII in Escherichia coli are induced independently. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;243:144–149. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90782-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manna D, Gowrishankar J. Evidence for involvement of proteins HU and RpoS in transcription of the osmoresponsive proU operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5378–5384. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5378-5384.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maurizi M R, Clark W P, Katayama Y, Rudikoff S, Pumphrey J, Bowers B, Gottesman S. Sequence and structure of ClpP, the proteolytic component of the ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12536–12545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCleary W R. The activation of PhoB by acetylphosphate. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1155–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muffler A, Fischer D, Altuvia S, Storz G, Hengge-Aronis R. The response regulator RssB controls stability of the ςS subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1996;15:1333–1339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mulvey M R, Loewen P C. Nucleotide sequence of katF of Escherichia coli suggests KatF protein in a novel ς transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9979–9991. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.23.9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mulvey M R, Switala J, Borys A, Loewen P C. Regulation of transcription of katE and katF in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6713–6720. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6713-6720.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neidhardt F C, Bloch P L, Smith D F. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:736–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Notley L, Ferenci T. Induction of RpoS-dependent functions in glucose-limited continuous culture: what level of nutrient limitation induces the stationary phase of Escherichia coli? J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1465–1468. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1465-1468.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pratt L A, Silhavy T J. The response regulator SprE controls the stability of RpoS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2488–2492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pratt L A, Silhavy T J. Crl stimulates RpoS activity during stationary phase. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1225–1236. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramakrishnan R, Schuster M, Bourret R B. Acetylation at Lys-92 enhances signaling by the chemotaxis response regulator protein CheY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4918–4923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roth J R, Benson N, Galitski T, Haack K, Lawrence J G, Miesel L. Rearrangements of the bacterial chromosome: formation and applications. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 2256–2276. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanders D A, Gillece-Castro B L, Stock A M, Burlingame A L, Koshland D E., Jr Identification of the site of phosphorylation of the chemotaxis response regulator protein, CheY. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:21770–21778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanders D A, Gillece-Castro B L, Burlingame A L, Koshland D E., Jr Phosphorylation site of NtrC, a protein phosphatase whose covalent intermediate activates transcription. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5117–5122. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.5117-5122.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schellhorn H E, Stones V L. Regulation of katF and katE in Escherichia coli K-12 by weak acids. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4769–4776. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4769-4776.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmieger H. Phage P22 mutants with increased or decreased transductional abilities. Mol Gen Genet. 1972;119:75–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00270447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schweder T, Lee K-H, Lomovskaya O, Matin A. Regulation of Escherichia coli starvation sigma factor (ςS) by ClpXP protease. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:470–476. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.470-476.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silhavy T J, Berman M L, Enquist L W. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanaka K, Takayanagi Y, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Takahashi H. Heterogeneity of the principal ς factor in Escherichia coli: the rpoS gene product, ς38, is a second principal ς factor of RNA polymerase in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3511–3515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Dyk T K, LaRossa R A. Involvement of ack-pta operon products in α-ketobutyrate metabolism by Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;207:435–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00331612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wanner B L, Wilmes-Riesenberg M R. Involvement of phosphotransacetylase, acetate kinase, and acetyl phosphate synthesis in control of the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2124–2130. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2124-2130.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wolf R E, Jr, Prather D M, Shea F M. Growth-rate-dependent alteration of 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase and glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase levels in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1979;139:1093–1096. doi: 10.1128/jb.139.3.1093-1096.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamashino T, Ueguchi C, Mizuno T. Quantitative control of the stationary phase-specific sigma factor, ςS, in Escherichia coli: involvement of the nucleoid protein H-NS. EMBO J. 1995;14:594–602. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou Y, Gottesman S. Regulation of proteolysis of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1154–1158. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1154-1158.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]