Abstract

Copper radical oxidases (CROs) from Auxiliary Activity Family 5, Subfamily 2 (AA5_2), are organic cofactor-free biocatalysts for the selective oxidation of alcohols to the corresponding aldehydes. AA5_2 CROs comprise canonical galactose-6-oxidases as well as the more recently discovered general alcohol oxidases and aryl alcohol oxidases. Guided by primary and tertiary protein structural analyses, we targeted a distinct extended loop in the active site of a Colletotrichum graminicola aryl alcohol oxidase (CgrAAO) to explore its effect on catalysis in the broader context of AA5_2. Deletion of this loop, which is bracketed by a conserved disulfide bridge, significantly reduced the inherent activity of the enzyme toward extended galacto-oligosaccharides, as anticipated from molecular modeling. Unexpectedly, kinetic and product analysis on a range of monosaccharides and disaccharides revealed that an altered carbohydrate specificity in CgrAAO-Δloop was accompanied by a complete change in regiospecificity from C-6 to C-1 oxidation, thereby generating aldonic acids. C-1 regiospecificity is unprecedented in AA5 enzymes and is classically associated with flavin-dependent carbohydrate oxidases of Auxiliary Activity Family 3. Thus, this work further highlights the catalytic adaptability of the unique mononuclear copper radical active site and provides a basis for the design of improved biocatalysts for diverse potential applications.

Keywords: copper radical oxidase, protein engineering, aryl alcohol oxidase, galactose oxidase, Auxiliary Activity Family 5 (AA5)

Introduction

Copper radical oxidases (CROs)1 comprise Auxiliary Activity Family 5 (AA5) in the carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZy) database, in which they are divided into two major phylogenetic subfamilies.2 Subfamily 1 (AA5_1) includes a small number of known (methyl)glyoxal oxidases (E.C. 1.2.3.15), which catalyze the oxidation of the eponymous aldehydes (or their hydrates) to the corresponding acids.3 Subfamily 2 (AA5_2) encompasses the archetypal galactose 6-oxidases (GalOx, E.C. 1.1.3.9),4,5 as well as the recently discovered general alcohol oxidases (AlcOx, E.C. 1.1.3.13),6−8 and aryl alcohol oxidases (AAO, E.C. 1.1.3.7),9,10 which convert the primary alcohol of their respective substrates to the corresponding aldehyde. Catalysis in AA5 members is mediated by a mononuclear copper center, which is coordinated by a unique cross-linked tyrosine–cysteine radical cofactor;11 molecular oxygen (O2) serves as the final electron acceptor to generate hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a co-product.1,12

The unique catalytic properties and substrate scope of CROs have long attracted interest for biocatalytic and biotechnological applications.13,14 For example, the archetypal GalOx from Fusarium graminearum (FgrGalOx) has been used for glycoprotein labeling,15 biosensor development,16 and polysaccharide functionalization17,18 since the 1960s. More recently, the use of specific alcohol oxidases from AA5_2 has been explored for the production of flavor and fragrance compounds19,20 and the transformation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) to polymer precursors.8−10 Not least, a large body of work has concerned the rational engineering or directed evolution of FgrGalOx to broaden its substrate scope and/or increase its catalytic efficiency for a range of applications,18,21−23 notably including the biocatalytic production of a key active pharmaceutical ingredient.24

In this context, we have recently described the catalytic properties and tertiary structure of an AA5_2 CRO from Colletotrichum graminicola, CgrAAO, with particularly high aryl alcohol oxidase activity and modest activity toward galactose and di- and trisaccharides containing a terminal galactose (t-Gal) residue at the nonreducing end.9 Analysis of the three-dimensional structure revealed a distinct extended loop near the active site comprising residues Trp554-Gly564 in the mature enzyme, the base of which is formed by a conserved disulfide bridge (Figure 1). Notably, the length of this loop is correlated with protein sequence similarity network (SSN) clusters and is generally shorter in the majority of AA5_2 members. These observations prompted us to explore the contribution of this loop to the substrate specificity of CgrAAO in the present study. Strikingly, loop truncation not only decreased the activity toward terminal galactose-containing saccharides but also radically altered the regioselectivity of the enzyme from C-6 to C-1 on a diversity of carbohydrates.

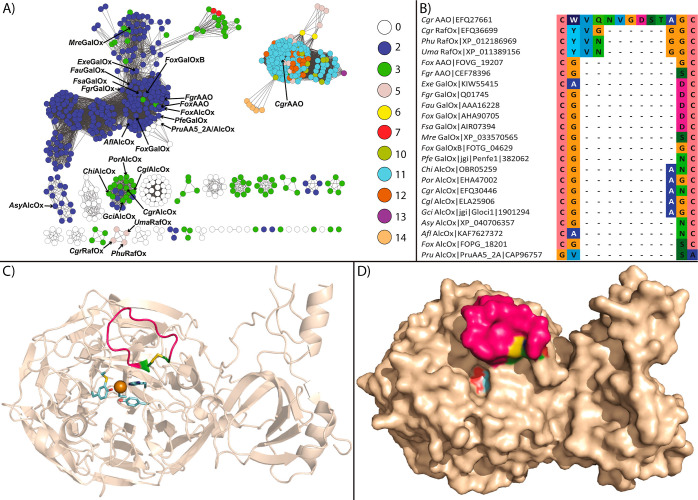

Figure 1.

Primary and tertiary structural analyses of the distinct loop region of CgrAAO in relation to 623 AA5_2 catalytic modules. (A) SSN of 623 catalytic modules from the AA5_2 subfamily at a bitscore threshold of 550. Predicted native signal peptides and additional N-terminal modules were removed prior to pairwise sequence alignment. Each node is colored according to the number of amino acids between the two cysteines forming a disulfide bond at the base of the loop. AA5 members with available biochemical data are indicated as galactose oxidases (FgrGalOx,26−28FoxGalOx,29FsaGalOx,30FauGalOx,31ExeGalOx, MreGalOx, FoxGalOxB, and PfeGalOx8), alcohol oxidases (CgrAlcOx, CglAlcOx,6ChiAlcOx, PorAlcOx,7GciAlcOx, AsyAlcOx, AflAlcOx, and FoxAlcOx8), AA5_2 oxidases ((PruAlcOx/PruAA5_2A)8,25), raffinose oxidases (CgrRafOx,32PhuRafOx, and UmaRafOx8), and aryl alcohol oxidases (CgrAAO,9FoxAAO, and FgrAAO10). (B) Multiple sequence alignment of residues forming CgrAAO-extended loops in characterized AA5_2s. (C) Top view of cartoon representation and (D) top view of surface representation of the CgrAAO-WT disulfide bridge and extended loop. For each panel, the copper atom is shown as an orange sphere; cysteine residues C553 and C565 forming the disulfide bridge and active-site residues Cys272, Tyr316, Tyr533, His534, and His632 involved in copper coordination and catalytic activity are depicted as green sticks and light cyan sticks, respectively; C atoms forming the extended loop are in hot pink, and other C atoms are in wheat.

Results

Identification of a Putative Substrate-Binding Determinant in CgrAAO

Upon the inspection of CgrAAO tertiary structure (PDB ID 6RYV(9)), a disulfide bridge between Cys553 and Cys565, forming the base of a distinct, extended loop of 11 amino acids near the active site, was identified (Figure 1). The conservation of these two cysteines and the length of the loop were assessed using a curated multiple sequence alignment of 623 AA5_2 catalytic modules.8 Mapping this information onto a SSN revealed a correlation between the subgroups and the loop length (Figure 1A,B). Among the 38 subgroups previously defined,8 five subgroups (92 total sequences) completely lacked the two cysteines forming the disulfide bridge, including the recently characterized PruAlcOx.8,25 Half of the sequences (360), comprising various characterized galactose-6-oxidases, general alcohol oxidases, and aryl alcohol oxidases, possessed either two or three residues within this loop (see Figure 1 for individual enzymes and the corresponding references). Seventeen AA5_2 members, including characterized raffinose oxidases (RafOx) possess loops of five residues long, while six or seven residues constitute the loops of only two sequences each. The remaining AA5_2 members possessed loops of 10–14 residues, grouped together in a distinct, unconnected cluster of 166 members. Of these, most had loops of 11 residues, as exemplified by CgrAAO9 (Figure 1). The amino acid variability within this loop for members harboring 5–14 residues is presented as logoplots in Figure S1.

No substrate or product complexes exist for the three structurally characterized AA5 members, including CgrAAO.6,9,11,23,28,33 In the absence of experimental data, we assessed the potential role of the extended loop in CgrAAO through the computational docking of melibiose (Galpα1-6Glcp), raffinose (Galpα1-6Glcpα1-2βFru), and lactose (Galpα1-4Glcp) in the active site (PDB ID 6RYV). All ligands gave reasonable binding poses and were within the plausible hydrogen-bonding distance to Trp554. Moreover, raffinose presents a potential π-stacking interaction of its glucopyranosyl unit with Trp554 while making an additional hydrogen bond to Gln556, both residues being located on the extended loop (Figure 2). Together, these analyses implicate the extended loop between the disulfide bridge in the increased specificity of the wild-type CgrAAO for longer terminal galactosylated saccharides (Table 1).9

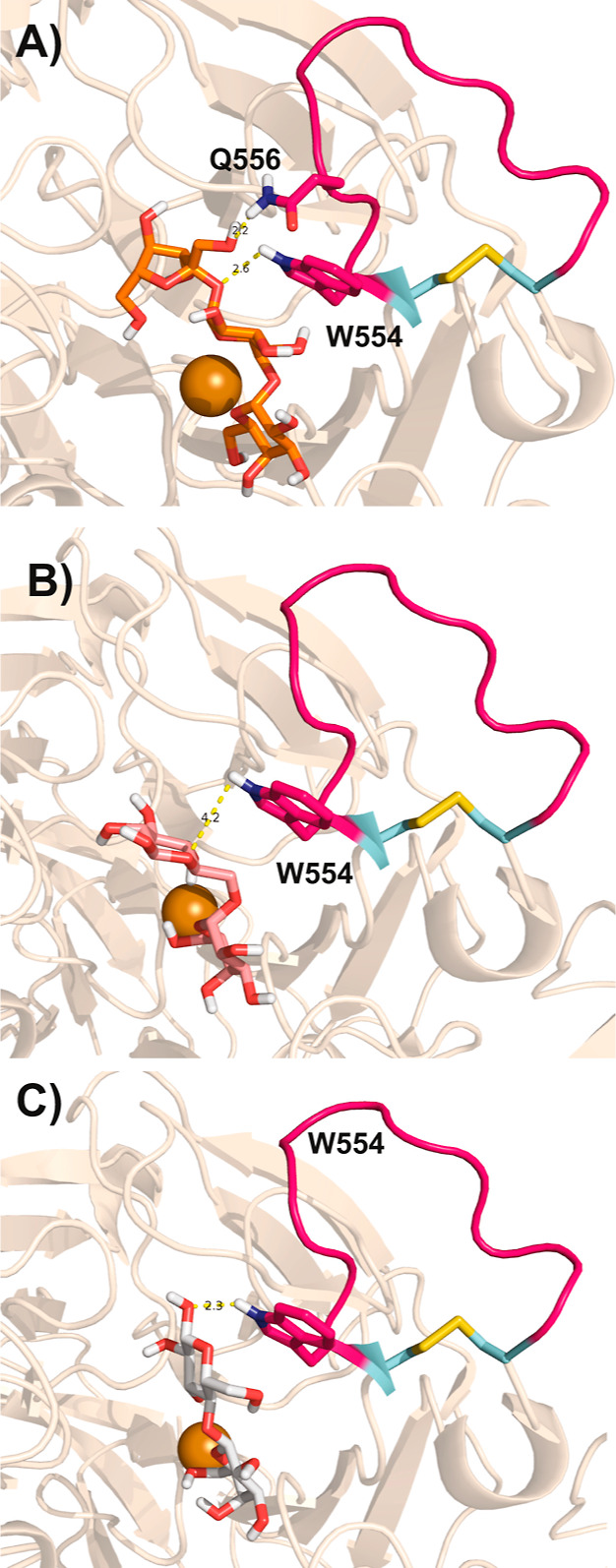

Figure 2.

Amino acids of the CgrAAO extended loop in hydrogen bonding with extended galacto-oligosaccharides. Molecular docking studies of raffinose (A), melibiose (B), and lactose (C) in CgrAAO-WT (PDB ID 6RYV) were conducted using AutoDock Vina, as implemented in Chimera. For all panels, the copper atom is depicted as an orange sphere; residues belonging to the extended loop (Trp554 and Gln556) and forming hydrogen bonds with the substrate are depicted as magenta sticks, with hydrogen-bonding moieties in purple/white and corresponding distances in yellow.

Table 1. Michaelis–Menten Kinetics of Wild-type CgrAAO and CgrAAO-Δloopa.

|

CgrAAO-WTc |

CgrAAO-Δloop |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| substrate | Km (mM) | kcat (s–1) | kcat/Km (M–1·s–1) | Km (mM) | kcat (s–1) | kcat/Km (M–1·s–1) |

| Carbohydrates | ||||||

| galactose | n.d.b | n.d.b | 13.1 ± 0.8 | (1.8 ± 0.2) × 103 | 19.4 ± 1.5 | 11 ± 0.9 |

| lactose | 999 ± 83 | 23.4 ± 2.2 | 23.5 ± 1.2 | 283 ± 17 | 16.5 ± 0.4 | 58 ± 3 |

| melibiose | 314 ± 15 | 12.3 ± 0.2 | 39.2 ± 2 | (2.7 ± 0.1) × 103 | 17.5 ± 0.5 | 6.45 ± 0.13 |

| raffinose | 291 ± 21 | 20.8 ± 0.6 | 71.5 ± 5.6 | n.d.b | n.d.b | 2.32 ± 0.03 |

| glucose | no Activity | n.d.b | n.d.b | 3.70 ± 0.03 | ||

| maltose | no Activity | 775 ± 109 | 13.9 ± 0.8 | 18.1 ± 2.1 | ||

| xylose | (5.2 ± 0.4) × 103 | 34.6 ± 1.6 | 6.7 ± 0.3 | (1.5 ± 0.1) × 103 | 21.3 ± 0.9 | 14 ± 0.8 |

| Polyols | ||||||

| glycerol | 605 ± 34 | 58.7 ± 0.9 | 97 ± 5.6 | (1.91 ± 0.07) × 103 | 18.4 ± 0.3 | 9.6 ± 0.3 |

| Diols | ||||||

| 1,3-propanediol | 384 ± 15 | 32.8 ± 0.4 | 85.4 ± 3.5 | (1.76 ± 0.09) × 103 | 17.9 ± 0.4 | 10.2 ± 0.4 |

| 1,2-propanediol | 1047 ± 64 | 17.4 ± 0.4 | 16.6 ± 1.1 | n.d.b | n.d.b | 0.85 ± 0.01 |

| Aryl Alcohols | ||||||

| benzyl alcohol | 27 ± 0.9 | 54.5 ± 0.6 | (2.02 ± 0.07) × 103 | 80.2 ± 4.0 | 29.8 ± 0.6 | 372 ± 16 |

| m-anisyl alcohol | 21 ± 0.8 | 140 ± 2 | (6.6 ± 0.3) × 103 | 31.7 ± 2.6 | 29.8 ± 1.1 | 943 ± 60 |

| p-anisyl alcohol | 24 ± 1.3 | 48 ± 1 | (2 ± 0.12) × 103 | 45.5 ± 3.4 | 19.7 ± 0.7 | 434 ± 36 |

| Furans | ||||||

| HMF | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 126 ± 1.5 | (1.94 ± 0.09) × 104 | 20.9 ± 0.9 | 19.3 ± 0.3 | 924 ± 36 |

| DFF | no activity | 200 ± 19 | 41.7 ± 2.9 | 209 ± 7.6 | ||

| Aldehydes | ||||||

| methylglyoxal | no activity | 42 ± 4 | 18.6 ± 0.5 | 446 ± 43 | ||

The measurements were performed by varying the substrate concentration from 10 mM to 2 M for carbohydrates, 10 mM to 5 M for glycerol and 1,3-propanediol, 250 mM to 7.5 M for 1,2-propanediol, 500 μM to 100 mM for m-anisyl alcohol and p-anisyl alcohol, 500 μM to 400 mM for benzyl alcohol, 500 μM to 100 mM for furans, and 1–250 mM for methyl glyoxal. The apparent steady-state kinetic constants were determined in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7, at 25 °C using the colorimetric HRP/ABTS assay using 1.3–13 μmol of purified enzyme. The affinity constant for the substrate, Km, and the turnover number, kcat, were calculated by nonlinear regression using the Michaelis–Menten equation. Data represent means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

Individual kcat and Km values not determinable; kcat/Km values obtained from the slope of linear v0 vs [S] plots.

Kinetic data of CgrAAO-WT were taken from its original characterization in ref (9), with the exception of xylose, which was performed for this study.

CgrAAO-Δloop Has a Modified Substrate Specificity Profile

To analyze the functional role of this structure in more detail, we created a truncated loop variant, CgrAAO-Δloop, bearing only two amino acids between the two cysteines instead of the eleven of the wild-type enzyme (Figure 1). CgrAAO-Δloop was produced in Pichia pastoris using the same conditions as described for the wild-type enzyme,9 yielding 14 mg from 400 mL of buffered complex methanol medium (BMMY) after purification (>95% pure according to SDS-PAGE analysis, Figure S2). The CgrAAO-Δloop variant retained all of the predicted N-glycosylation sites of the wild type (N309, N386, and N644, corresponding to N309, N386, and N635 in CgrAAO-Δloop). Glycosylation was confirmed by the treatment with PNGaseF or EndoH; the deglycosylated protein had an apparent molar mass of 75 kDa (Figure S2). Although we were unsuccessful in obtaining diffraction quality crystals of the CgrAAO-Δloop variant (W. Offen and G.J. Davies, University of York, personal communication), structural homology modeling indicated that the loop deletion did not alter the positions of the active-site copper ligands (Figure S3).

The initial analysis of specific activity and subsequent Michaelis–Menten kinetic analysis using a range of carbohydrates, other alcohols, and aldehyde substrates of AA5 enzymes demonstrated that CgrAAO-Δloop generally had a comparable substrate range versus the wild-type enzyme (Figure 3, Table 1, and Figure S4). That is, there was no major change in the overall specificity profile of the loop variant across the general compound classes of carbohydrates, three-carbon diols and triols, and aryl alcohols including HMF. As a class, aryl alcohols remained the best substrates for CgrAAO-Δloop, as judged by kcat/Km values. The pH rate profile and temperature stability of CgrAAO-Δloop were also essentially unchanged versus the wild-type enzyme, using HMF as a common, high-activity reference substrate (Figures S5 and S6, cf. ref (9)). Hence, all subsequent kinetic analyses were performed at pH 7.0 and 25 °C.

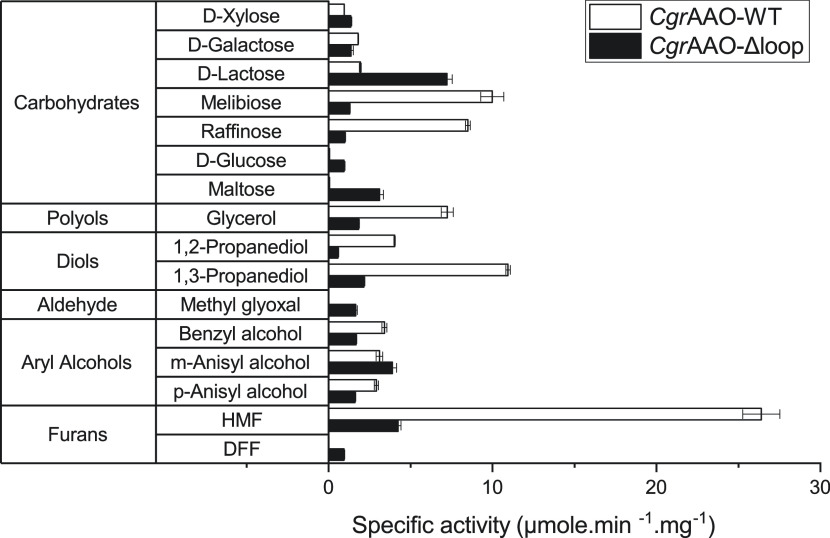

Figure 3.

Specific activity of CgrAAO-WT and CgrAAO-Δloop on a diversity of potential substrates. Measurements were performed in triplicate at 25 °C in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) using the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)/2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assay. Activities were monitored using 300 mM for carbohydrates, polyols, and diols; 50 mM for methylglyoxal; and 5 mM for aryl alcohols and furans. Reactions were started with the addition of 1.3–65 μmol of purified enzyme.

However, notable exceptions were observed for activities toward certain carbohydrates. The t-Gal-containing disaccharide and trisaccharide analogues melibiose and raffinose, respectively, had greatly reduced activities with CgrAAO-Δloop and were now among the poorest substrates. This was primarily manifested through increased Km values. Indeed, we were unable to achieve enzyme saturation using raffinose concentrations up to 1 M (Km could not be independently determined) nor melibiose concentrations up to 2 M (Figure S4). These observations are commensurate with our molecular docking studies that implicate the extended loop of the wild-type enzyme in the binding of longer carbohydrate substrates (Figure 2). In contrast, the monosaccharide galactose, which exhibited a strictly linear relationship between the initial velocity and substrate concentration with the wild-type enzyme,9 demonstrated curvature with CgrAAO-Δloop (Figure S4). Although the extracted Km value is poor (ca. 1.8 M, Table 1) at a similar kcat/Km value to the wild type, this nonetheless suggests an improved interaction with the active site in CgrAAO-Δloop. Likewise, a reduced Km value for lactose was observed for CgrAAO-Δloop versus the wild-type enzyme (Table 1 and Figure S4). Most striking, however, was the observation that the CgrAAO-Δloop variant gained activity on d-glucose and the diglucoside maltose, which were not turned over by the wild-type enzyme (Figure 3, Table 1, and Figure S4). Here, saturation behavior was not observed with glucose concentrations up to 2 M, while maltose exhibited a Km value of 0.8 M (kcat, 14 s–1) (Table 1 and Figure S4). CgrAAO-Δloop also uniquely gained activity toward the aldehydes methylglyoxal and 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF) (Figure 3, Table 1, and Figure S4).

Product Analysis Reveal Altered Carbohydrate Regioselectivity in CgrAAO-Δloop

To date, characterized wild-type AA5_2 enzymes, including the archetype FgrGalOx, have been shown to oxidize the primary hydroxyl group on C-6 of d-galactose and d-galactopyranosides to the corresponding aldehyde (which typically becomes hydrated to form the gem-diol).4,9,32,34 More generally, some AA5_2 members can oxidize the primary hydroxyl groups on the noncarbohydrate alkyl and aryl alcohols.6−9 To fully understand the altered substrate specificity observed for the CgrAAO-Δloop variant, detailed product analysis was conducted using one-dimensional (1H, 13C{1H}, TOCSY) and two-dimensional (HSQC, HMBC, and TOSCY) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques, in comparison with the reference spectra.35

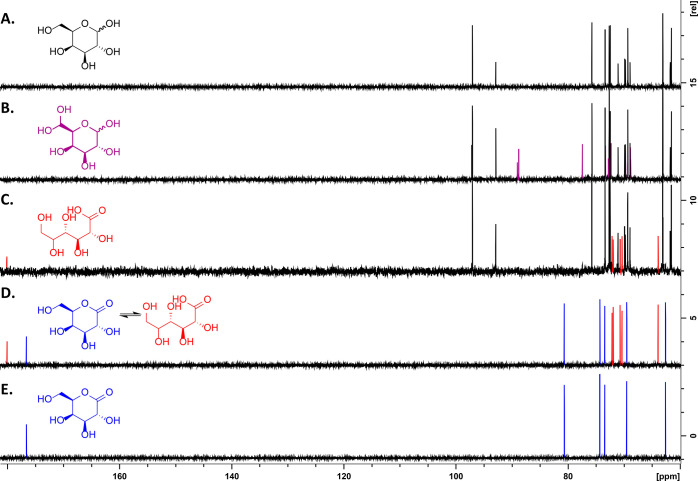

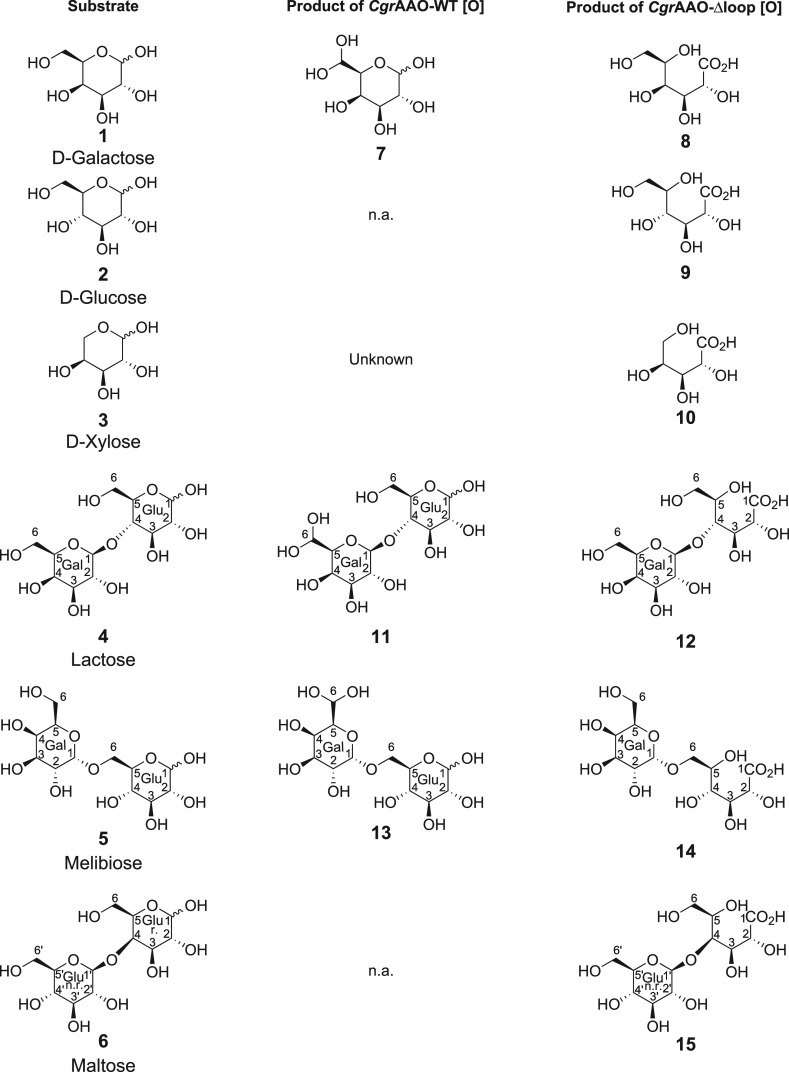

As expected,34 the control reaction of CgrAAO-WT with galactose (Figure 4, and Figure 5 compound 1) yielded only the gem-diols corresponding to the hydrated forms of the C6-oxidized galactose alpha- and beta-anomers (Figure 4, and Figure 5, compound 7), amounting to 32% conversion with H-6 doublets observed at 5.10 and 5.13 ppm, respectively (Figures S7–S9 and Tables S1 and S2). The NMR spectra for the reaction of CgrAAO-Δloop with galactose were surprisingly different. Under the same reaction conditions, only a small amount of C6-oxidized product (gem-diol) was observed by 1H NMR, equivalent to 6% conversion (Figure S7 and Table S1). In addition, a doublet at 4.26 ppm was observed, which was correlated to a quaternary carbon at 180.11 ppm (Figures S7, S10 and S11, Table S3). Comparison with the 13C{1H} reference spectra35 of d-galactono-1,5-lactone in water and 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7, the latter of which hydrolyzes the lactone, confirmed the formation of galactonic acid by CgrAAO-Δloop (Figure 4). Integration of the 1H NMR spectrum indicated that galactonic acid (Figure 5, compound 8) was the major product of galactose oxidation by CgrAAO-Δloop (22% conversion; Figure S7 and Table S1), thus revealing the switch from exclusive C-6 regioselectivity in the wild-type enzyme to predominant C-1 regioselectivity in the truncated loop variant.

Figure 4.

CgrAAO-WT and CgrAAO-Δloop galactose oxidation product analysis. 13C NMR spectra (600 MHz); (A) control reaction showing no conversion of galactose by HRP and catalase, (B) oxidation of d-galactose by CgrAAO-WT showing conversion to the C6 gem-diol, (C) oxidation of d-galactose by CgrAAO-Δloop showing conversion to galactonic acid, (D) d-galacto-1,5-lactone dissolved in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7, showing its equilibrium with d-galactonic acid, and (E) d-galacto-1,5-lactone dissolved in D2O. All reaction profiles were taken after 24 h incubation with 20 mg of substrate in the presence of catalase and HRP. Carbon signals in purple correspond to the C6-oxidized galactose product, while the red carbon signals correspond to galactonic acid and the blue signals correspond to d-galacto-1,5-lactone. Signals are referenced to the acetone peak at 30.89 ppm (not shown) that was used as an internal standard.

Figure 5.

Summary of the observed major products from the oxidation of mono- and oligosaccharides by CgrAAO-WT and CgrAAO-Δloop. *n.a., not assessed; Gal, galactose; Glu, glucose; n.r., nonreducing end; r., reducing end.

Wild-type CgrAAO, like other AA5 enzymes including classical galactose-6-oxidases, is not active on d-glucose, the C-4 epimer of d-galactose (Figure 3, Table 1). Analogous to d-galactose, NMR analysis demonstrated that CgrAAO-Δloop oxidizes d-glucose (Figure 5, compound 2) at C-1 to produce exclusively d-gluconic acid (Figure 5, compound 9) with 17% substrate conversion (Figures S12–S15 and Tables S1 and S4). Further supporting this regioselectivity, reactions of methyl α-d-glucopyranoside and methyl β-d-glucopyranoside evidenced no detectable activity using the HRP–ABTS coupled assay and no new peaks in the corresponding NMR spectra (data not shown).

Likewise, the oxidation of d-xylose (Figure 5, compound 3), the predominant pyranose form of which is stereochemically analogous to d-glucose but lacks the hydroxymethyl ring substituent,36 by CgrAAO-Δloop produced only xylonic acid (Figure 5, compound 10) with 30% substrate conversion (Figures S16, S18, and S19; Tables S1 and S5). Interestingly, the wild-type CgrAAO was also able to oxidize d-xylose, with kinetics similar to d-galactose (Figure 3 and Table 1), despite the lack of a hydroxymethyl group. Product analysis indicated that wild-type CgrAAO in fact produced 9% d-xylonic acid from d-xylose, based on the appearance of a doublet at 4.26 ppm corresponding to H2 of aldonic acid. However, the structure(s) of the major product(s) from d-xylose oxidation by the wild type, represented by doublets at 5.21 and 4.60 ppm (corresponding to 19% conversion), is currently unknown (Figures S16 and S17; Table S1). A full assignment was not possible due to the low overall conversion and the apparent presence of multiple products in the 1H and 13C spectra. Nevertheless, it is clear that the truncation of the loop in CgrAAO shifted the product profile from forming a small amount of xylonic acid and another unknown product for the wild-type to xylonic acid being the only product for the variant (Figure S17).

The C-1 regiospecific oxidation of monosaccharides by the CgrAAO-Δloop variant was precisely recapitulated with the disaccharides lactose (Figure 5, compound 4), melibiose (Figure 5, compound 5), and maltose (Figure 5, compound 6). Like specific galactose-6-oxidases from AA5, wild-type CgrAAO predominantly oxidizes C6 of the galactopyranosyl residues of lactose (Galpβ1-4Glcp) and melibiose (Galpα1-6Glcp) to the corresponding hydrated aldehydes (Figure 5, compounds 11 and 13, respectively; Figures S20–S22, S27–S30; Tables S1, S6, and S7). In the case of melibiose, further oxidation to C-6 carboxylate was observed under the reaction conditions, while a limited amount of C-1 oxidation of lactose was observed (Figures S27–S30; Tables S1 and S7). In contrast, the CgrAAO-Δloop variant produced exclusively lactobionic acid (Figure 5, compound 12) and predominantly melibionic acid (Figure 5, compound 14) by C-1 oxidation of the glucopyranosyl ring, analogous to the oxidation of d-glucose (Figures S20, S23–S27, S31–S33, and Tables S8 and S9). In the case of melibiose, a very limited amount of C-6 oxidation was still observed, accounting for 3% of the total product distribution (Figure S27 and Table S1). Likewise, the diglucoside maltose (Galpα1-6Glcp; Figure 5, compound 6), which was not a substrate for the wild-type enzyme because it lacks a t-Gal residue, was oxidized exclusively to maltobionic acid (Figure 5, compound 15; Table S1) by the CgrAAO-Δloop variant (Figures S34–S37 and Table S10). Commensurate with the poor catalytic efficiency observed on raffinose with the CgrAAO-Δloop variant (Table 1), due to the loss of the ability to oxidize C-6 of t-Gal residues, very limited conversion (3%, Table S1) was observed (Figure S38). The weak signals in the NMR spectra precluded structural assignment, although comparison with the corresponding product spectra of Fusarium graminicola aryl alcohol oxidase (FgrAAO) from AA5 ruled out the possibility of C6-galactosyl and C6-fructosyl oxidation.10

HMF, via its oxidized derivatives, is a biomass-derived feedstock of particular contemporary interest37 and an exemplar aryl alcohol substrate of AA5 CROs.8−10 We previously showed that the dialdehyde DFF is the sole product of HMF oxidation by wild-type CgrAAO.9 As the CgrAAO-Δloop variant gained the ability to oxidize DFF at the expense of HMF activity (Table 1), product analysis by NMR experiments was performed on these two substrates. Similar to the wild type, the reaction of CgrAAO-Δloop with HMF yielded only DFF; however, the reaction of CgrAAO-Δloop with DFF (which has a 10-fold higher Km value, Table 1) showed conversion to formylfurancarboxylic acid (FFCA) and 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) (Figures S39 and S40).

Discussion

There is sustained and growing interest in the use of redox-active enzymes to replace chemical oxidants in the conversion of chemical feedstocks.38 However, the majority of oxidases used in industrial reactions require organic cofactors, with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) [NAD(P)]-dependent enzymes requiring a cofactor recycling strategy, which adds complexity to processes.39 In this regard, CROs represent an alternative for the biocatalytic production of valuable chemicals.19,40,41 Recent work has unveiled that the natural catalytic diversity of AA5 CROs is much broader than the archetypal galactose-6-oxidase activity,41,42 also comprising individual enzymes with predominant activity on a range of alkyl and aryl alcohols, including glycerol, HMF, and HMF derivatives.6−10 However, despite this growing body of functional data, the protein structural features that dictate substrate specificity across the phylogenetic diversity of these enzymes remain elusive, particularly in the absence of three-dimensional enzyme–substrate complex structures.6,9,11,23,28,33

The extended loop near the catalytic copper ion of CgrAAO is representative of a subgroup of AA_2 members that clearly segregates in the SSN (Figure 1). Molecular docking of galactosylated saccharides within CgrAAO revealed Trp554 and Gln556 as the likely contributors to substrate recognition via hydrogen bonding (Figure 2). Notably, a planar aromatic/hydrogen-binding amino acid (tryptophan, tyrosine, proline, or histidine) is highly conserved among “long-loop” homologues in the position equivalent to Trp554 (Figure S1). At the position equivalent to Gln556, more variability is observed, although the hydrogen-bonding potential is generally retained; most of the sequences harbor either a glutamine, an asparagine, or an aspartic acid. Molecular modeling of the truncated loop variant CgrAAO-Δloop using AlphaFold Collab indicated that the removal of these and the other residues comprising the extended loop was unlikely to otherwise cause major structural perturbations, aside from the subtle repositioning of the disulfide bond and the shorter loop, as well as perhaps slightly constricting the active-site cavity (Figure S3).

Characterization of the substrate preference of CgrAAO-Δloop revealed a number of notable differences vis-à-vis the wild-type enzyme. First, the aldehydes methylglyoxal and DFF, which were not turned over by the wild-type enzyme, exhibited catalytic efficiencies similar to aryl alcohols, including HMF, with the loop variant (Figure 3, Table 1, and Figure S4). Biocatalysis of HMF and its oxidized derivatives is of particular interest to generate bifunctional polymer precursors from biomass.37 When compared with other characterized enzymes (Table S11), CgrAAO-Δloop has one of the highest kcat values reported for DFF oxidation, while its comparatively high Km value results in a catalytic efficiency within the same order of magnitude as the fungal AAOs from Pleurotus eryngii,43F. graminearum, Fusarium oxysporum,10 as well as the fungal glyoxal oxidase (GLOX) Pycnoporus cinnabarinus GLOX1.44 The homologues GLOX2 and GLOX3 from P. cinnabarinus are considerably more efficient (Table S11).44 When compared to the native45 or engineered46 bacterial flavo-oxidoreductases acting on DFF, the higher turnover rate of CgrAAO-Δloop compensates for its unfavorable Km value, resulting in a higher catalytic efficiency by 1 to 2 orders of magnitude (Tables 1 and S11). Commensurate with our results on CgrAAO-Δloop, wild-type AA5_2 members that have been shown previously to oxidize DFF, had either a short version of the loop (FgrAAO, FoxAAO, CglAlcOx, FoxGalOxB, AflAlcOx, and PorAlcOx) or no loop at all (PruAA5_2A/PruAlcOx) (Figure 1).8,10

The ability of CgrAAO-Δloop to oxidize the bis-aldehyde DFF is likely related to the simultaneous gain of ability to oxidize methylglyoxal, a typical substrate of glyoxal oxidases from the subfamily AA5_1.47−49 The kcat/Km value of CgrAAO-Δloop for methylglyoxal is within the same order of magnitude as the other top substrates of this variant (aryl alcohols and HMF). This catalytic efficiency is comparable to the recently characterized Myceliophthora thermophila GLOX50 and Trichoderma reesei lignin copper oxidase (LOX)51 but is 1 to 2 orders of magnitude lower than the homologues GLOX1, GLOX2, and GLOX3 from P. cinnabarinus(47) and the glyoxal oxidase of Phanerochaete chrysosporium(49) (Tables 1 and S12). The absence of individual kinetic parameters for the glyoxal oxidase of Ustilago maydis prevents direct comparison.52

Overall, carbohydrates remained poor substrates for CgrAAO-Δloop, with the catalytic efficiencies ranging from 2 to 58 M–1 s–1, mostly due to high Km values (0.2–3.0 M, Table 1). We originally interpreted the significantly decreased catalytic efficiency of CgrAAO-Δloop toward melibiose and raffinose (Figure 2 and Table 1) as commensurate with the removal of the extended loop proximal to the active site (Figure 1). However, the observation of new activity (Figure 2 and Table 1) on the nongalactosylated substrates glucose and maltose, as well as the increased activity on xylose, necessitated careful product analyses. In particular, engineering glucose-6-oxidase specificity into the AA5 CRO archetype, FgrGalOx, has been of considerable interest, although the specific activity achieved was very low (1.6 U/mg).21 Here, we envisioned that CgrAAO-Δloop might constitute a new biocatalyst for applications, for example, starch modification.

Product analysis by NMR instead revealed something even more surprising: the CgrAAO-Δloop variant in fact had gained C-1 carbohydrate oxidase activity at the expense of C-6 oxidase activity. Most of the carbohydrates tested were preferentially oxidized to the corresponding aldonic acids by CgrAAO-Δloop, as opposed to the wild-type enzyme that oxidized the t-Gal-containing substrates to the corresponding 6-aldehydes (observed as the hydrated, gem-diol forms) (Figure 5, Tables S1–S10, and Figures S6–S36). This observation of a change in mechanism has a major implication for the subsequent interpretation of kinetic constants, which in this light cannot be compared between the wild-type and loop-variant enzymes. For CgrAAO-Δloop, C-1 oxidation was the most efficient in the order: lactose, maltose, xylose, galactose, melibiose, and glucose, with the lower kcat/Km values observed for the last four substrates arising from poor apparent Km values (Table 1). We also noticed a direct correlation between catalytic efficiency and substrate conversion, likely due to the higher active-site affinity reflected in lower Km values, especially for lactose and maltose (Tables 1 and S1). Interestingly, the C-1 oxidase activity identified for xylose with CgrAAO-Δloop was also detected in the wild-type enzyme, albeit with a much poorer apparent Km value (Table 1 and Figure S16). Xylose lacks a C-6 hydroxymethyl group (cf. glucose); therefore, in the absence of a primary hydroxyl group, the wild-type enzyme apparently possesses some latent C-1 oxidase activity. Taken together, these results indicate a significant catalytic flexibility of the reactive copper center, which defies rationalization with regard to specific active-site structure–function relationships.

In light of the newly acquired activity toward the aldehydes DFF and methylglyoxal (Table 1), we might speculate that the C-1 regioselectivity of CgrAAO-Δloop toward carbohydrates is coherent with the oxidation of the open-chain aldehydo forms to yield the corresponding aldonic acids (Figure 5). On the other hand, the solution concentrations of aldehydo sugars, which are the intermediates in mutarotation, are vanishingly small.36 Moreover, (methyl)glyoxal oxidases from the subfamily AA5_1 are proposed to act on the hydrated form of the aldehyde,3 that is, the gem-diol, which, in the cases of carbohydrates, are in competition with cyclic hemiacetals.53 However, although the equilibrium concentrations of these aldehydo and C-1-hydrated sugars are consequently low in solution, they may still be kinetically relevant. On the other hand, direct oxidation of the closed-ring, anomeric hemiacetals by an analogous mechanism of proton abstraction from the anomeric hydroxyl, H-1 radical abstraction and subsequent electron transfer steps26,54 is also plausible, although sterically more encumbered. Unfortunately, the rapid equilibrium exchange of the various carbohydrate forms makes delineating the specific substrate structure(s) bound by the active site extremely challenging experimentally.

C-1 regioselectivity toward carbohydrates has not been observed previously within AA5 CROs, neither in wild-type nor engineered variants.6,21−23 Thus far, the only known C-1 carbohydrate oxidases are fungal flavo-oxidases of Auxiliary Activity Family 3 (AA3), which are part of the GMC oxidoreductase superfamily,55 and Auxiliary Activity Family 7 (AA7).2 AA3 members include glucose oxidase from Aspergillus niger(56) and cellobiose dehydrogenase from P. chrysosporium,57 while AA7 members include gluco-oligosaccharide oxidase from Sarocladium strictum (also known as Acremonium strictum).58 A possible exception, in retrospect, is the inherent xylose 1-oxidase activity of wild-type CgrAAO, although this pales in comparison to the activity on aryl alcohols and galactosyl residues (Table 1 and ref (9)). It is striking, therefore, that loop truncation near the active site of CgrAAO resulted in a radical switch in regioselectivity to generate a competent C-1 carbohydrate oxidase. Given the abundance of AA5 members with extended loops, it remains to be seen whether similar protein engineering can be used to generate other biocatalysts as alternatives to the widely used flavo-oxidases for applications.14,59 The breadth of substrate preferences now known for wild-type CROs, coupled with the ability to modify specificity, as exemplified here and previously, underscores the versatility and potential of this family of enzymes.

Materials and Methods

Bioinformatics

Amino acid variability of the residues forming the extended loop, for members harboring at least five residues, was assessed using the Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) suite (https://meme-suite.org/meme/).60 Molecular docking into the CgrAAO crystal structure (PDB ID 6RYV(9)) was performed using Autodock VINA and the AMBER FF14sb force field, as implemented within CHIMERA.61 The structures of melibiose, raffinose, and lactose were retrieved from PubChem (CIDs 439242, 440658, and 6134, respectively). The proteins and ligands were first prepared by adding hydrogens and assigning appropriate protonation states. Simulation cells were defined according to the ligand sterics with the copper atom bordering the z-coordinate edge. The receptor–ligand complex structures were further analyzed using the PyMOL software (Schrodinger LLC) to determine the interatomic distances. A homology model of the loop truncation variant, CgrAAO-Δloop, was created using AlphaFold Collab.62

Construct Generation and P. pastoris Transformation

CgrAAO-Δloop, corresponding to the deletion of residues Trp554–Thr562 in the mature enzyme, was generated using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs) according to the supplier’s protocol. The primer sequences are listed in Table S13. The PCR products were then treated with a kinase–ligase–DpnI enzyme mix for 1 h at room temperature prior to their transformation into competent Escherichia coliDH5α using the heat-shock method. Positive transformants were selected on Luria–Bertani low-salt (LBLS) agar plates containing 25 μg·mL–1 Zeocin at 37 °C overnight. Surviving colonies were picked and grown overnight at 37 °C in 5 mL of LBLS medium with 25 μg·mL–1 Zeocin. Plasmids were then extracted using a commercial miniprep kit (Geneaid, New Taipei City, Taiwan), and mutagenesis was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Transformation of pCgrAAOΔloop into P. pastoris X33 was performed by digesting 20 μg of plasmid DNA for 3 h at 37 °C with PmeI (New England Biolabs). After enzyme inactivation at 65 °C for 10 min, the linearized plasmid was purified using a gel/PCR DNA fragment kit (Geneaid, New Taipei City, Taiwan). The resulting digested plasmid (3.85 μg) was transformed into electrocompetent P. pastoris X33 cells prepared on the same day.63 The transformants were grown on yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) agar plates for 3 days at 30 °C and selected against 100 or 500 μg·mL–1 Zeocin. Several colonies were streaked on YPD agar plates containing either 100 or 500 μg·mL–1 Zeocin and grown for 3 days at 30 °C to select clones with multicopy insertions. Twelve colonies selected from 100 or 500 μg·mL–1 Zeocin plates were inoculated into 24 sterile round-bottom deep-well plates (10 mL) containing 5 mL of buffered complex glycerol medium (BMGY), sealed with a Nunc breathable sealing tape, and grown in a shaking incubator overnight at 30 °C and 225 rpm. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature; the BMGY medium was discarded and replaced with 2 mL of BMMY containing 1% (v/v) methanol. The cultures were shaken at 250 rpm over 4 days at either 30, 20, or 16 °C with regular feeding of either 1 or 3% (v/v) methanol every 24 h to ensure continued protein expression. The secreted proteins were separated from the cells by centrifugation at 2000g for 10 min, and protein production was monitored using SDS-PAGE. The clone yielding the highest amount of protein was retained for large-scale production.

Protein Production and Purification

Single colonies of P. pastoris X33 expressing the gene of interest were individually streaked on a YPD agar plate containing 500 μg·mL–1 Zeocin and grown for 2 days at 30 °C. A single colony was then used to inoculate 10 mL of YPD and grown at 30 °C, shaken at 200 rpm for 8 h. Biomass production was initiated by the addition of the 10 mL culture to 1 L BMGY medium in a 4 L baffled flask with a foam cap, which was shaken at 250 rpm at 30 °C until OD600 reached 5–6. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3700 rpm for 10 min at room temperature under sterile conditions. The cell pellet was quickly resuspended in 400 mL of BMMY supplemented with 0.5 mM CuSO4 and 1% methanol (v/v) in a sterile 2 L baffled flask with a foam cap. The cultures were shaken at 250 rpm at 16 °C for 4 days with regular feeding of methanol every 24 h to ensure continued protein expression. After 4 days, proteins in the extracellular medium were separated from the cells by centrifugation at 2500g for 15 min at 4 °C and used for subsequent purification. Purification was done following a previously published protocol without modification.9 The protein concentration was determined by measuring A280 using an extinction coefficient of 102,260 M–1·cm–1, which was calculated using the ProtParam tool on the ExPASy server (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/). CgrAAO-Δloop was N-deglycosylated by treatment with endoglycosidase Hf (New England Biolabs) or N-glycosidase F (PNGase F, New England Biolabs), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 5 μg of pure enzymes were denatured at 100 °C for 10 min, followed by the addition of either endo-Hf or PNGase F and incubating for 1 h at 37 °C. Efficient deglycosylation was assessed on 4–20% (w/v) precast polyacrylamide gradient gels in the presence of 2% (w/v) SDS under reducing conditions.

Enzyme Kinetic Analysis

Oxidation of all substrates was determined using a colorimetric HRP–ABTS coupled assay, as previously described.9 Upon substrate oxidation, AA5_2 CROs consume 1 equiv of O2 and concomitantly generate 1 equiv of H2O2, which is used in turn by HRP to oxidize two equivalents of ABTS (ε420 = 36,000 M–1·cm–1). One unit of AA5_2 activity was defined, therefore, as the amount of enzyme necessary for the oxidation of 2 μmol of ABTS per minute, corresponding to the consumption of 1 μmol of O2 per minute.

Each assay was performed at 25 °C in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7 with 0.49 mM ABTS, 2.3 μM HRP, and different substrate concentrations: from 10 mM to 2 M for carbohydrates, 10 mM to 5 M for glycerol and 1,3-propanediol, 250 mM to 7.5 M for 1,2-propanediol, 500–100 mM for m-anisyl alcohol and p-anisyl alcohol, 500 μM to 400 mM for benzyl alcohol, 500 μM to 100 mM for furans, and 1–250 mM for methyl glyoxal. Reactions were started by the addition of 1.3–13 μmol of purified enzyme in 500 μL reactions, and steady-state parameters were determined using Origin software on three replicates of each measurement point. The initial reaction rates at different substrate concentrations were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation for the determination of Km and kcat values.

The effect of temperature on activity was determined by incubating aliquots of purified recombinant enzymes at 25–50 °C in 100 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7. Samples were taken out at different time intervals for assays with 100 mM HMF. pH rate profiles were determined by incubating aliquots of purified enzyme in 100 mM citrate phosphate buffer from pH 5 to 5.5, in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer from pH 5.5 to 8.5, and in 100 mM glycine–NaOH buffer from pH 8.5 to 10 with 100 mM HMF. Each measurement was made in triplicate.

Product Analysis

Reactions containing 20 mg of carbohydrate (d-glucose, methyl α-d-glucopyranoside, methyl β-d-glucopyranoside, d-xylose, d-galactose, melibiose, lactose, maltose, or raffinose), 1.62 mg HMF, or 1.62 mg DFF in the presence of 1 mg of both catalase and HRP were initiated by the addition of 500 μg of purified CgrAAO-WT or CgrAAO-Δloop in a final volume of 1 mL (100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0). Reactions were stirred with a magnetic bar at 400 rpm at room temperature for 24 h, and enzymes were subsequently removed by ultrafiltration (10 kDa cutoff Centricon-Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Products were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and lyophilized. The resulting powders were resuspended in D2O for NMR analysis. Control reactions without the enzyme were performed under the same conditions.

NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker AVANCE 600 MHz spectrometer. 1H and 13C spectra were calibrated using an internal standard of acetone (0.11 M; 2.22 and 30.89 ppm, respectively). Peak integration values were used to determine the extent of substrate conversion to product(s). Standards of d-galactonic acid and d-gluconic acid were used to verify the chemical shifts for each molecule.

Acknowledgments

We thank Oleg Sannikov (UBC Department of Chemistry) for support with NMR data acquisition. We thank Wendy Offen and Prof. Gideon J. Davies for their efforts to obtain an experimental structure of CgrAAO-Δloop.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CRO

copper radical oxidase

- AA5_2

Auxiliary Activity Family 5/Subfamily 2

- AAO

aryl alcohol oxidase

- AA3

Auxiliary Activity Family 3

- CAZy

carbohydrate-active enzymes

- AA5_1

Auxiliary Activity Family 5/Subfamily 1

- GalOx

galactose oxidase

- AlcOx

alcohol oxidase

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- O2

molecular oxygen

- HMF

5-hydroxymethylfurfural

- SSN

sequence similarity network

- RafOx

raffinose oxidase

- WT

wild type

- BMMY

buffered complex methanol medium

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PNGaseF

peptide-N-glycosidase F

- EndoH

endoglycosidase H

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- ABTS

2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

- DFF

2,5-diformylfuran

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- FFCA

2,5-formylfurancarboxylic acid

- FDCA

2,5-furandicarboxylic acid

- HMFCA

5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- NAD(P)

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate)

- GLOX

glyoxal oxidase

- LOX

lignin copper oxidase

- AA7

Auxiliary Activity Family 7

- MEME

Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation

- LBLS

Luria–Bertani low salt

- YPD

yeast extract peptone dextrose

- BMGY

buffered complex glycerol medium

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.2c01956.

Amino acid logoplots, glycosylation analysis, enzyme kinetics, and enzyme product analysis by NMR (PDF)

Author Contributions

Y.M. performed bioinformatics, mutagenesis, cloning, recombinant protein production, biochemistry, enzyme kinetics, and all the corresponding data analyses and drafted and revised the manuscript. M.E.C. developed the methodology and performed product analysis by NMR, wrote portions of the manuscript, and revised the manuscript. H.B. coordinated the research, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript.

Funding is gratefully acknowledged from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant RGPIN-2018-03892, the NSERC Strategic Partnership Grant NETGP 451431-13 for the “NSERC Industrial Biocatalysis Network”, the joint NSERC/Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) Strategic Partnership Grant STPGP 493781-16 for “FUNTASTIC—fungal copper radical oxidases as new biocatalysts for the valorization of biomass carbohydrates and alcohols”, and the Genome Canada/Genome BC/Ontario Genomics/Genome Quebec grant for the Large-Scale Applied Research Project #10405 “SYNBIOMICS––functional genomics and techno-economic models for advanced biopolymer synthesis”.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kersten P.; Cullen D. Copper Radical Oxidases and Related Extracellular Oxidoreductases of Wood-decay Agaricomycetes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014, 72, 124–130. 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur A.; Drula E.; Lombard V.; Coutinho P. M.; Henrissat B. Expansion of the Enzymatic Repertoire of the CAZy Database to Integrate Auxiliary Redox Enzymes. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 41. 10.1186/1754-6834-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker M. M.; Kersten P. J.; Nakamura N.; Sanders-Loehr J.; Schweizer E. S.; Whittaker J. W. Glyoxal Oxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium is a New Radical-Copper Oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 681–687. 10.1074/jbc.271.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avigad G.; Amaral D.; Asensio C.; Horecker B. L. The D-Galactose Oxidase of Polyporus circinatus. J. Biol. Chem. 1962, 237, 2736–2743. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)60220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cooper J. A. D.; Smith W.; Bacila M.; Medina H. Galactose Oxidase from Polyporus circinatus. J. Biol. Chem. 1959, 234, 445–448. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)70223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nobles M. K.; Madhosingh C. Dactyliumdendroides (Bull.) Fr. Misnamed as Polyporuscircinatus Fr. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1963, 12, 146–147. 10.1016/0006-291X(63)90251-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D.; Urresti S.; Lafond M.; Johnston E. M.; Derikvand F.; Ciano L.; Berrin J.-G.; Henrissat B.; Walton P. H.; Davies G. J.; et al. Structure–Function Characterization Reveals New Catalytic Diversity in the Galactose Oxidase and Glyoxal Oxidase Family. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10197. 10.1038/ncomms10197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oide S.; Tanaka Y.; Watanabe A.; Inui M. Carbohydrate-binding Property of a Cell Wall Integrity and Stress Response Component (WSC) Domain of an Alcohol Oxidase from the Rice Blast Pathogen Pyricularia oryzae. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2019, 125, 13–20. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland M. E.; Mathieu Y.; Ribeaucourt D.; Haon M.; Mulyk P.; Hein J. E.; Lafond M.; Berrin J.-G.; Brumer H. A Survey of Substrate Specificity Among Auxiliary Activity Family 5 Copper Radical Oxidases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 8187–8208. 10.1007/s00018-021-03981-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu Y.; Offen W. A.; Forget S. M.; Ciano L.; Viborg A. H.; Blagova E.; Henrissat B.; Walton P. H.; Davies G. J.; Brumer H. Discovery of a Fungal Copper Radical Oxidase with High Catalytic Efficiency toward 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural and Benzyl Alcohols for Bioprocessing. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 3042–3058. 10.1021/acscatal.9b04727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland M.; Lafond M.; Xia F. R.; Chung R.; Mulyk P.; Hein J. E.; Brumer H. Two Fusarium Copper Radical Oxidases With High Activity on Aryl Alcohols. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 138. 10.1186/s13068-021-01984-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito N.; Phillips S. E. V.; Stevens C.; Ogel Z. B.; McPherson M. J.; Keen J. N.; Yadav K. D. S.; Knowles P. F. Novel Thioether Bond Revealed by a 1.7 Å Crystal Structure of Galactose Oxidase. Nature 1991, 350, 87–90. 10.1038/350087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker J. W. Free Radical Catalysis by Galactose Oxidase. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2347–2364. 10.1021/cr020425z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wahart A. J. C.; Staniland J.; Miller G. J.; Cosgrove S. C. Oxidase Enzymes as Sustainable Oxidation Catalysts. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211572. 10.1098/rsos.211572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dong J.; Fernández-Fueyo E.; Hollmann F.; Paul C. E.; Pesic M.; Schmidt S.; Wang Y.; Younes S.; Zhang W. Biocatalytic Oxidation Reactions: A Chemist’s Perspective. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 9238–9261. 10.1002/anie.201800343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann F.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Buehler K.; Schallmey A.; Bühler B. Enzyme-Mediated Oxidations for the Chemist. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 226–265. 10.1039/C0GC00595A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Roberts G. P.; Gupta S. K. Use of Galactose Oxidase in the Histochemical Examination of Mucus-secreting Cells. Nature 1965, 207, 425–426. 10.1038/207425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Heitzmann H.; Richards M. Use of the Avidin-Biotin Complex for Specific Staining of Biological Membranes in Electron Microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1974, 71, 3537–3541. 10.1073/pnas.71.9.3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wilchek M.; Spiegel S.; Spiegel Y. Fluorescent Reagents for the Labeling of Glycoconjugates in Solution and on Cell Surfaces. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1980, 92, 1215–1222. 10.1016/0006-291X(80)90416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ramya T. N. C.; Weerapana E.; Cravatt B. F.; Paulson J. C. Glycoproteomics Enabled by Tagging Sialic Acid- or Galactose-terminated Glycans. Glycobiology 2013, 23, 211–221. 10.1093/glycob/cws144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monosik R.; Stredansky M.; Tkac J.; Sturdik E. Application of Enzyme Biosensors in Analysis of Food and Beverages. Food Anal. Methods 2012, 5, 40–53. 10.1007/s12161-011-9222-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Mikkonen K. S.; Parikka K.; Suuronen J.-P.; Ghafar A.; Serimaa R.; Tenkanen M. Enzymatic Oxidation as a Potential New Route to Produce Polysaccharide Aerogels. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 11884–11892. 10.1039/C3RA47440B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Leppänen A.-S.; Xu C.; Parikka K.; Eklund P.; Sjöholm R.; Brumer H.; Tenkanen M.; Willför S. Targeted Allylation and Propargylation of Galactose-containing Polysaccharides in Water. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 100, 46–54. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Xu C.; Spadiut O.; Araújo A. C.; Nakhai A.; Brumer H. Chemo-enzymatic Assembly of Clickable Cellulose Surfaces via Multivalent Polysaccharides. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 661–665. 10.1002/cssc.201100522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Yalpani M.; Hall L. D. Some Chemical and Analytical Aspects of Polysaccharide Modifications. II. A High-yielding, Specific Method for the Chemical Derivatization of Galactose-containing Polysaccharides: Oxidation with Galactose Oxidase Followed by Reductive Amination. J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Chem. Ed. 1982, 20, 3399–3420. 10.1002/pol.1982.170201213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Kelleher F. M.; Bhavanandan V. P. Preparation and Characterization of β-d-fructofuranosyl O-(α-d-galactopyranosyl uronic acid)-(1→6)-O-α-d-glucopyranoside and O-(α-d-galactopyranosyl uronic acid)-(1→6)-d-glucose. Carbohydr. Res. 1986, 155, 89–97. 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke J. A.; Paschall A. V.; Glushka J.; Lees A.; Moremen K. W.; Avci F. Y. Harnessing Galactose Oxidase in the Development of a Chemoenzymatic Platform for Glycoconjugate Vaccine Design. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101453. 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeaucourt D.; Bissaro B.; Guallar V.; Yemloul M.; Haon M.; Grisel S.; Alphand V.; Brumer H.; Lambert F.; Berrin J.-G.; et al. Comprehensive Insights into the Production of Long Chain Aliphatic Aldehydes Using a Copper-Radical Alcohol Oxidase as Biocatalyst. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 4411–4421. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c07406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeaucourt D.; Saker S.; Navarro D.; Bissaro B.; Drula E.; Correia O.; Haon M.; Grisel S.; Lapalu N.; Henrissat B.; et al. Identification of Copper-Containing Oxidoreductases in the Secretomes of Three Colletotrichum Species with a Focus on Copper Radical Oxidases for the Biocatalytic Production of Fatty Aldehydes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e01526–01521. 10.1128/AEM.01526-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L.; Bulter T.; Alcalde M.; Petrounia I. P.; Arnold F. H. Modification of Galactose Oxidase to Introduce Glucose 6-Oxidase Activity. ChemBioChem 2002, 3, 7812–7838. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lippow S. M.; Moon T. S.; Basu S.; Yoon S.-H.; Li X.; Chapman B. A.; Robison K.; Lipovšek D.; Prather K. L. J. Engineering Enzyme Specificity Using Computational Design of a Defined-Sequence Library. Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 1306–1315. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Escalettes F.; Turner N. J. Directed Evolution of Galactose Oxidase: Generation of Enantioselective Secondary Alcohol Oxidases. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 857–860. 10.1002/cbic.200700689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Herter S.; McKenna S. M.; Frazer A. R.; Leimkühler S.; Carnell A. J.; Turner N. J. Galactose Oxidase Variants for the Oxidation of Amino Alcohols in Enzyme Cascade Synthesis. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 2313–2317. 10.1002/cctc.201500218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Birmingham W. R.; Turner N. J. A Single Enzyme Oxidative “Cascade” via a Dual-Functional Galactose Oxidase. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4025–4032. 10.1021/acscatal.8b00043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Delagrave S.; Murphy D. J.; Pruss J. L. R.; Maffia A. M. III; Marrs B. L.; Bylina E. J.; Coleman W. J.; Grek C. L.; Dilworth M. R.; Yang M. M.; et al. Application of a Very High-Throughput Digital Imaging Screen to Evolve the Enzyme Galactose Oxidase. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 2001, 14, 261–267. 10.1093/protein/14.4.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Deacon S. E.; McPherson M. J. Enhanced Expression and Purification of Fungal Galactose Oxidase in Escherichia coli and Use for Analysis of a Saturation Mutagenesis Library. ChemBioChem 2011, 12, 593–601. 10.1002/cbic.201000634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Sun L.; Petrounia I. P.; Yagasaki M.; Bandara G.; Arnold F. H. Expression and Stabilization of Galactose Oxidase in Escherichia coli by Directed Evolution. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 2001, 14, 699–704. 10.1093/protein/14.9.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Deacon S. E.; Mahmoud K.; Spooner R. K.; Firbank S. J.; Knowles P. F.; Phillips S. E. V.; McPherson M. J. Enhanced Fructose Oxidase Activity in a Galactose Oxidase Variant. ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 972–979. 10.1002/cbic.200300810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rannes J. B.; Ioannou A.; Willies S. C.; Grogan G.; Behrens C.; Flitsch S. L.; Turner N. J. Glycoprotein Labeling Using Engineered Variants of Galactose Oxidase Obtained by Directed Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8436–8439. 10.1021/ja2018477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wilkinson D.; Akumanyi N.; Hurtado-Guerrero R.; Dawkes H.; Knowles P. F.; Phillips S. E. V.; McPherson M. J. Structural and Kinetic Studies of a Series of Mutants of Galactose Oxidase Identified by Directed Evolution. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 2004, 17, 141–148. 10.1093/protein/gzh018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman A.; Fryszkowska A.; Alvizo O.; Borra-Garske M.; Campos R.; Canada A.; Devine N.; Duan D.; Forstater H.; Grosser T.; et al. Design of an in vitro Biocatalytic Cascade for the Manufacture of Islatravir. Science 2019, 366, 1255–1259. 10.1126/science.aay8484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollerup F.; Aumala V.; Parikka K.; Mathieu Y.; Brumer H.; Tenkanen M.; Master E. A family AA5_2 Carbohydrate Oxidase from Penicillium rubens Displays Functional Overlap Across the AA5 Family. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0216546 10.1371/journal.pone.0216546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker J. W. The Radical Chemistry of Galactose Oxidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005, 433, 227–239. 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito N.; Phillips S. E. V.; Yadav K. D. S.; Knowles P. F. Crystal Structure of a Free Radical Enzyme, Galactose Oxidase. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 238, 794–814. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M. S.; Tyler E. M.; Akyumani N.; Kurtis C. R.; Spooner R. K.; Deacon S. E.; Tamber S.; Firbank S. J.; Mahmoud K.; Knowles P. F.; et al. The Stacking Tryptophan of Galactose Oxidase: A Second-Coordination Sphere Residue that Has Profound Effects on Tyrosyl Radical Behavior and Enzyme Catalysis. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 4606–4618. 10.1021/bi062139d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paukner R.; Staudigl P.; Choosri W.; Sygmund C.; Halada P.; Haltrich D.; Leitner C. Galactose Oxidase from Fusarium oxysporum - Expression in E. coli and P. pastoris and Biochemical Characterization. PLoS One 2014, 9, e100116 10.1371/journal.pone.0100116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paukner R.; Staudigl P.; Choosri W.; Haltrich D.; Leitner C. Expression, Purification, and Characterization of Galactose Oxidase of Fusarium sambucinum in E. coli. Protein Expression Purif. 2015, 108, 73–79. 10.1016/j.pep.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M. J.; Ogel Z. B.; Stevens C.; Yadav K. D.; Keen J. N.; Knowles P. F. Galactose Oxidase of Dactylium dendroides. Gene Cloning and Sequence Analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 8146–8152. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)42419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andberg M.; Mollerup F.; Parikka K.; Koutaniemi S.; Boer H.; Juvonen M.; Master E.; Tenkanen M.; Kruus K.; Cullen D. A Novel Colletotrichum graminicola Raffinose Oxidase in the AA5 Family. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01383–01317. 10.1128/AEM.01383-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Firbank S. J.; Rogers M. S.; Wilmot C. M.; Dooley D. M.; Halcrow M. A.; Knowles P. F.; McPherson M. J.; Phillips S. E. V. Crystal Structure of the Precursor of Galactose Oxidase: An Unusual Self-Processing Enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001, 98, 12932–12937. 10.1073/pnas.231463798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rogers M. S.; Hurtado-Guerrero R.; Firbank S. J.; Halcrow M. A.; Dooley D. M.; Phillips S. E. V.; Knowles P. F.; McPherson M. J. Cross-Link Formation of the Cysteine 228–Tyrosine 272 Catalytic Cofactor of Galactose Oxidase Does Not Require Dioxygen. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 10428–10439. 10.1021/bi8010835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li J.; Davis I.; Griffith W. P.; Liu A. Formation of Monofluorinated Radical Cofactor in Galactose Oxidase through Copper-Mediated C–F Bond Scission. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 18753–18757. 10.1021/jacs.0c08992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikka K.; Tenkanen M. Oxidation of Methyl α-d-galactopyranoside by Galactose Oxidase: Products Formed and Optimization of Reaction Conditions for Production of Aldehyde. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 14–20. 10.1016/j.carres.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart D. S.; Guo A.; Oler E.; Wang F.; Anjum A.; Peters H.; Dizon R.; Sayeeda Z.; Tian S.; Lee B. L.; et al. HMDB 5.0: the Human Metabolome Database for 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D622–D631. 10.1093/nar/gkab1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angyal S. J. The Composition and Conformation of Sugars in Solution. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1969, 8, 157–166. 10.1002/anie.196901571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhang Y.; Zhang J.; Su D. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural: A Key Intermediate for Efficient Biomass Conversion. J. Energy Chem. 2015, 24, 548–551. 10.1016/j.jechem.2015.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Rosatella A. A.; Simeonov S. P.; Frade R. F. M.; Afonso C. A. M. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) as a Building Block Platform: Biological Properties, Synthesis and Synthetic Applications. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 754–793. 10.1039/C0GC00401D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Hu L.; He A.; Liu X.; Xia J.; Xu J.; Zhou S.; Xu J. Biocatalytic Transformation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural into High-Value Derivatives: Recent Advances and Future Aspects. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 15915–15935. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b04356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Domínguez de María P.; Guajardo N. Biocatalytic Valorization of Furans: Opportunities for Inherently Unstable Substrates. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 4123–4134. 10.1002/cssc.201701583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Snajdrova R.; Moore J. C.; Baldenius K.; Bornscheuer U. T. Biocatalysis: Enzymatic Synthesis for Industrial Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 88–119. 10.1002/anie.202006648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami P.; Chinnadayyala S. S. R.; Chakraborty M.; Kumar A. K.; Kakoti A. An Overview on Alcohol Oxidases and Their Potential Applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 4259–4275. 10.1007/s00253-013-4842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toftgaard Pedersen A.; Birmingham W. R.; Rehn G.; Charnock S. J.; Turner N. J.; Woodley J. M. Process Requirements of Galactose Oxidase Catalyzed Oxidation of Alcohols. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 1580–1589. 10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parikka K.; Master E.; Tenkanen M. Oxidation with Galactose Oxidase: Multifunctional Enzymatic Catalysis. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2015, 120, 47–59. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2015.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siebum A.; van Wijk A.; Schoevaart R.; Kieboom T. Galactose Oxidase and Alcohol Oxidase: Scope and Limitations for the Enzymatic Synthesis of Aldehydes. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2006, 41, 141–145. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2006.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carro J.; Ferreira P.; Rodríguez L.; Prieto A.; Serrano A.; Balcells B.; Ardá A.; Jiménez-Barbero J.; Gutiérrez A.; Ullrich R.; et al. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Conversion by Fungal Aryl-Alcohol Oxidase and Unspecific Peroxygenase. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 3218–3229. 10.1111/febs.13177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daou M.; Yassine B.; Wikee S.; Record E.; Duprat F.; Bertrand E.; Faulds C. B. Pycnoporus cinnabarinus Glyoxal Oxidases Display Differential Catalytic Efficiencies on 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural and its Oxidized Derivatives. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2019, 6, 4. 10.1186/s40694-019-0067-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkman P.; Fraaije W. Discovery and Characterization of a 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Oxidase from Methylovorus sp. Strain MP688. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1082–1090. 10.1128/AEM.03740-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Viñambres M.; Espada M.; Martínez T.; Serrano A.; Kelly Robert M. Screening and Evaluation of New Hydroxymethylfurfural Oxidases for Furandicarboxylic Acid Production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00842–00820. 10.1128/AEM.00842-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sánchez-Ruiz M. I.; Martínez A. T.; Serrano A. Optimizing Operational Parameters for the Enzymatic Production of Furandicarboxylic Acid Building Block. Microb. Cell Fact. 2021, 20, 180. 10.1186/s12934-021-01669-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daou M.; Piumi F.; Cullen D.; Record E.; Faulds B.; Brakhage A. A. Heterologous Production and Characterization of Two Glyoxal Oxidases from Pycnoporus cinnabarinus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 4867–4875. 10.1128/AEM.00304-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten P. J.; Kirk T. K. Involvement of a new enzyme, glyoxal oxidase, in extracellular H2O2 production by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 2195–2201. 10.1128/jb.169.5.2195-2201.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlschlager L.; Csarman F.; Zrilić M.; Seiboth B.; Ludwig R. Comparative Characterization of Glyoxal Oxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium Expressed at High Levels in Pichia pastoris and Trichoderma reesei. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2021, 145, 109748. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2021.109748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki M. A.; Godoy M. O.; Kumagai P. S.; Costa-Filho A. J.; Mort A.; Prade R. A.; Polikarpov I. Characterization of a New Glyoxal Oxidase from the Thermophilic Fungus Myceliophthora thermophila M77: Hydrogen Peroxide Production Retained in 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Oxidation. Catalysts 2018, 8, 476. 10.3390/catal8100476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daou M.; Bisotto A.; Haon M.; Oliveira Correia L.; Cottyn B.; Drula E.; Garajová S.; Bertrand E.; Record E.; Navarro D. A Putative Lignin Copper Oxidase from Trichoderma reesei. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 643. 10.3390/jof7080643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuthner B.; Aichinger C.; Oehmen E.; Koopmann E.; Müller O.; Müller P.; Kahmann R.; Bölker M.; Schreier P. H. A H2O2-Producing Glyoxal Oxidase is Required for Filamentous Growth and Pathogenicity in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2005, 272, 639–650. 10.1007/s00438-004-1085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce J.; Serianni A. S.; Barker R. Anomerization of Furanose Sugars and Sugar Phosphates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 2448–2456. 10.1021/ja00294a041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klinman J. P. How Do Enzymes Activate Oxygen without Inactivating Themselves?. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 325–333. 10.1021/ar6000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavener D. R. G. M. C. GMC oxidoreductases. J. Mol. Biol. 1992, 223, 811–814. 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90992-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Pazur J. H.; Kleppe K. The Oxidation of Glucose and Related Compounds by Glucose Oxidase from Aspergillus niger. Biochemistry 1964, 3, 578–583. 10.1021/bi00892a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wohlfahrt G.; Witt S.; Hendle J.; Schomburg D.; Kalisz H. M.; Hecht H.-J. 1.8 and 1.9 A Resolution Structures of the Penicillium amagasakiense and Aspergillus niger Glucose Oxidases as a Basis for Modelling Substrate Complexes. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 1999, 55, 969–977. 10.1107/S0907444999003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson G.; Pettersson G.; Johansson G.; Ruiz A.; Uzcategui E. Cellobiose Oxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium can be Cleaved by Papain into Two Domains. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991, 196, 101–106. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lin S.-F.; Yang T.-Y.; Inukai T.; Yamasaki M.; Tsai Y.-C. Purification and Characterization of a Novel Glucooligosaccharide Oxidase from Acremonium strictum T1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1991, 1118, 41–47. 10.1016/0167-4838(91)90439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Huang C.-H.; Lai W.-L.; Lee M.-H.; Chen C.-J.; Vasella A.; Tsai Y.-C.; Liaw S.-H. Crystal Structure of Glucooligosaccharide Oxidase from Acremonium strictum: A Novel Flavinylation of 6-S-Cysteinyl, 8α-N1-Histidyl FAD. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 38831–38838. 10.1074/jbc.M506078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Martínez A. T.; Ruiz-Dueñas F. J.; Camarero S.; Serrano A.; Linde D.; Lund H.; Vind J.; Tovborg M.; Herold-Majumdar O. M.; Hofrichter M.; et al. Oxidoreductases on Their Way to Industrial Biotransformations. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 815–831. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ouedraogo D.; Gadda G. Flavoprotein Oxidases. Flavin-Based Catal. 2021, 225–244. 10.1002/9783527830138.ch9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L.; Johnson J.; Grant C. E.; Noble W. S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. 10.1093/nar/gkv416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F.; Goddard T. D.; Huang C. C.; Couch G. S.; Greenblatt D. M.; Meng E. C.; Ferrin T. E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J.; Evans R.; Pritzel A.; Green T.; Figurnov M.; Ronneberger O.; Tunyasuvunakool K.; Bates R.; Žídek A.; Potapenko A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregg J. M.; Russell K. A.. Transformation. Pichia Protocols; Humana Press, 1998; pp 27–39. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.