Abstract

Background

Mitochondrial dysfunction caused by mitochondrial (mtDNA) deletions have been associated with skeletal muscle atrophy and myofibre loss. However, whether such defects occurring in myofibres cause sarcopenia is unclear. Also, the contribution of mtDNA alterations in muscle stem cells (MuSCs) to sarcopenia remains to be investigated.

Methods

We expressed a dominant‐negative variant of the mitochondrial helicase, which induces mtDNA alterations, specifically in differentiated myofibres (K320Eskm mice) and MuSCs (K320Emsc mice), respectively, and investigated their impact on muscle structure and function by immunohistochemistry, analysis of mtDNA and respiratory chain content, muscle transcriptome and functional tests.

Results

K320Eskm mice at 24 months of age had higher levels of mtDNA deletions compared with controls in soleus (SOL, 0.07673% vs. 0.00015%, P = 0.0167), extensor digitorum longus (EDL, 0.0649 vs. 0.000925, P = 0.0015) and gastrocnemius (GAS, 0.09353 vs. 0.000425, P = 0.0004). K320Eskm mice revealed a progressive increase in the proportion of cytochrome c oxidase deficient (COX−) fibres in skeletal muscle cross sections, reaching a maximum of 3.03%, 4.36%, 13.58%, and 17.08% in EDL, SOL, tibialis anterior (TA) and GAS, respectively. However, mice did not show accelerated loss of muscle mass, muscle strength or physical performance. Histological analyses revealed ragged red fibres but also stimulated regeneration, indicating activation of MuSCs. RNAseq demonstrated enhanced expression of genes associated with protein synthesis, but also degradation, as well as muscle fibre differentiation and cell proliferation. In contrast, 7 days after destruction by cardiotoxin, regenerating TA of K320Emsc mice showed 30% of COX− fibres. Notably, regenerated muscle showed dystrophic changes, increased fibrosis (2.5% vs. 1.6%, P = 0.0003), increased abundance of fat cells (2.76% vs. 0.23%, P = 0.0144) and reduced muscle mass (regenerated TA: 40.0 mg vs. 60.2 mg, P = 0.0171). In contrast to muscles from K320Eskm mice, freshly isolated MuSCs from aged K320Emsc mice were completely devoid of mtDNA alterations. However, after passaging, mtDNA copy number as well as respiratory chain subunits and p62 levels gradually decreased.

Conclusions

Taken together, accumulation of large‐scale mtDNA alterations in myofibres alone is not sufficient to cause sarcopenia. Expression of K320E‐Twinkle is tolerated in quiescent MuSCs, but progressively leads to mtDNA and respiratory chain depletion upon activation, in vivo and in vitro, possibly caused by an increased mitochondrial removal. Altogether, our results suggest that the accumulation of mtDNA alterations in myofibres activates regeneration during aging, which leads to sarcopenia if such alterations have expanded in MuSCs as well.

Keywords: mtDNA deletions, Mutations, Myofibres, Muscle stem cells, Satellite cells, Mitochondria

Introduction

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles with various cellular functions, including ATP production, calcium handling and signalling, but also amino acid and lipid metabolism, 1 all critical for skeletal muscle function. Consequently, ageing‐related mitochondrial dysfunction has long been suspected to play a role in sarcopenia. 2 , 3 One important factor driving mitochondrial dysfunction is the accumulation of large‐scale mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) rearrangements in muscle fibres. 4 These alterations (deletions and duplications/insertions) arise and accumulate progressively, probably due to errors during replication and/or inefficient repair of double‐strand breaks, potentially caused by reactive oxygen species. 5 When exceeding a detrimental threshold, usually >60% of the total mtDNA pool, they cause fibre segments with severe respiratory chain (RC) defects, detectable histochemically as a decrease in the enzymatic activity of the cytochrome C oxidase complex (COX−) and a compensatory increase in the activity of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH++) (COX−/SDH++, ragged red fibres), which do not contain mtDNA‐encoded subunits. These RC defects occur concomitantly to atrophy, splitting, breakage and loss of muscle fibres. 3 , 6

Considering that only short longitudinal segments of a few (<5%) myofibres are affected by mtDNA alterations in most mammalian species at old age, 7 , 8 it remains unclear whether these defects and the subsequent RC deficiency are sufficient to cause sarcopenia, that is, loss of mass, strength and performance of the whole muscle. Moreover, damage or loss of myofibres activates efficient regeneration by resident muscle stem cells (MuSCs). 9 Therefore, myofibres damaged due to mtDNA alterations may be effectively repaired, unless the regenerative capacity of MuSCs is severely compromised as well. Importantly, previous evidence has already suggested that a decline in mitochondrial function is among the key cell intrinsic factors that impairs MuSC‐dependent regeneration in aged muscles, 10 and indeed, depletion of these cells impaired adaptation to long‐term physical exercise in mice. 11 Therefore, we investigated whether the accumulation of mtDNA alterations in myofibres of four different muscles (soleus, SOL; extensor digitorum longus, EDL; gastrocnemius, GAS; and tibialis anterior, TA) or in MuSCs, respectively, significantly contributes to sarcopenia.

Methods

Transgenic mice

K320Eskm mice (C57BL/6J) were generated by crossing MLC1f‐Cre mice 12 with R26‐K320E‐TwinkleloxP/+ mice. 13 K320Emsc mice were generated by expressing K320E‐Twinkle under the control of MuSCs‐specific Pax7‐CreERT. 14 Mice from both genders were included. All procedures were approved by the local authority (LANUV, approval number: 2013‐A165 and 2019‐A090).

Treadmill exercise performance and rotarod test

Physical performance of sedentary 12‐ and 20‐month‐old mice was evaluated by forced treadmill exercise. Mice received a total of three training sessions on two consecutive days followed by experimental measurements. To assess exercise performance, the initial speed of 5 cm/s was increased by 5 cm/s every 1 min for a total of 3 min and thereafter by 2 cm/s every 3 min until exhaustion. For motor balance and coordination, the initial constant speed of 4 rpm was accelerated to 20 rpm/min. The latency to fall on the first trial and the mean latency on the test day (fourth day) were analysed.

Ex vivo isometric force generation and fatigue measurements

All experiments were performed as described before. 15 Isometric force was measured by stimulating for 1.1 s (SOL) and 0.4 s (EDL) with long tetanic pulses every 3 min at increasing frequency (25–150 Hz). To measure fatigue, 0.35 s tetanic pulses of 100 Hz (SOL) or 125 Hz (EDL) were applied every 3.7 s, and the force decline during 10 min was normalized to baseline. The maximal specific tetanic force generated was determined from the plateau of force–frequency curves, and the specific force was calculated by dividing by the muscle cross‐sectional area (wet weight (mg)/mean fibre length (mm) × 1.06 mg/mm3 (estimated density)) as previously described. 16 The fatigue index was determined by dividing the forces at the respective time point by the force at the beginning of the long and short interval fatigue.

Regeneration experiments

For regeneration experiments, Pax7‐CreERT was activated by injecting mice intraperitoneally for 5 days with 75 mg/kg/day of tamoxifen (Merck). Two days after the last injection, mice were anaesthetized with 2% xylazine, 10% ketamine in 0.9% NaCl. Muscle regeneration was induced by injecting one TA with 50 µl of cardiotoxin (CTX) from Naja mossambica (Sigma). At specific time points, mice were sacrificed, and muscles were snap‐frozen in isopentane pre‐cooled in liquid nitrogen and stored until needed.

Satellite cell isolation

Posterior hindlimb muscles were isolated from 6‐ to 8‐week‐old mice for in vitro proliferation analysis or at the indicated age for quiescent satellite cells analysis. In this case, K320E‐Twinkle expression was induced at 3 months of age with tamoxifen as explained before. Muscles were isolated and digested with PBS containing 10 mg/mL Collagenase II, 4 mg/mL Dispase and 2.5 mM CaCl2 for 1 h at 37°C. Satellite cells were isolated using a gentleMACS Dissociator, Satellite Cells Isolation Kit and a MACS separator following supplier's protocol (Miltenyi Biotec). For mtDNA analysis of aged mice, the pellet was directly used for DNA isolation. For proliferation experiments, cells were seeded on collagen‐coated dishes in expansion medium (40% DMEM 4.5 g/L glucose containing Glutamax, 40% HAM's F10, 20% FBS, 2.5 ng/μL bFGF, 1× chick embryo extract and 1× penicillin/streptomycin). Expression of K320E‐Twinkle was induced with 10 μM 4‐hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma) for 48 h. Medium was replaced every second day, and cells were passaged before reaching confluency.

Statistics

All data were analysed with GraphPad Prism. Two‐factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyse data on age‐dependent increase of mtDNA deletions, COX‐deficient fibres and body weight. Spearman's correlation test was used to analyse the correlation between the proportions of COX‐deficient fibres and centrally nucleated fibres. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05. Data are reported as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM).

Results

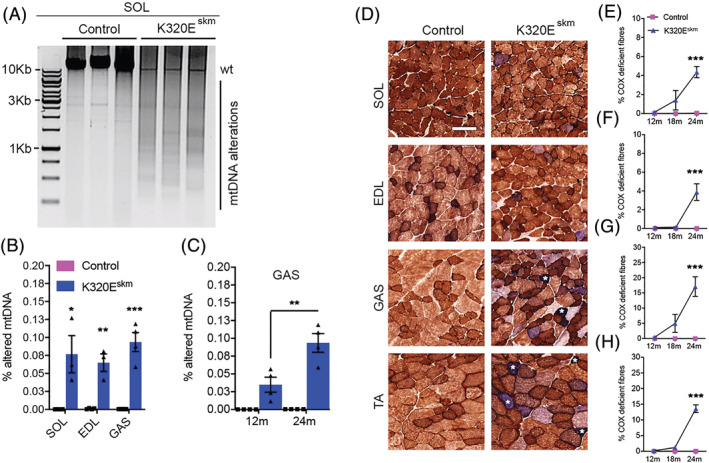

K320Eskm muscles show accelerated accumulation of mtDNA alterations and age‐dependent COX deficiency

As shown in Figure 1A, multiple mtDNA alterations were detectable by long‐range PCR in SOL of both genotypes at the age of 24 months. Using deep sequencing, we found recently that the majority of these species are duplications, that is, random insertions of mtDNA sequences leading to molecules larger than 16 kb. 17 However, K320Eskm mice showed a much larger variety of such molecules and had significantly higher levels of the representative ‘mouse common deletions’ 1, 3 and 17 18 (Figure S1) compared with controls in SOL (0.07673 vs. 0.00015, P = 0.0167), EDL (0.065 vs. 0.000925, P = 0.0015) and GAS (0.09353 vs. 0.000425, P = 0.0004; Figure 1B) when using qPCR. As an example, analysis of K320Eskm GAS demonstrated that these selected deletions increased by a factor of 2.7 between the age of 12 and 24 months (Figure 1C). Sequential COX/SDH histochemistry revealed the presence of fibres with COX deficiency (COX−, blue) in K320Eskm mice starting at 12 months and dramatically increasing between 18 and 24 months (Figure 1D–H). Importantly, the accumulation of COX− fibres did not occur to the same extent in the different analysed muscles, ranging from 3% (EDL) to 17% (GAS) at 24 months (Table 1). mtDNA deletions have been shown to induce an increase in SDH activity due to a futile compensatory activation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Several COX−/SDH++ fibres were apparent, particularly in GAS and TA but rarely in SOL and EDL of 24‐month‐old K320Eskm mice (white asterisks in Figure 1D). Consistent with this, modified Gomori trichrome analysis revealed an increased number of ragged red fibres (RRF) in GAS, but not in SOL, of 24‐month‐old K320Eskm mice (Figure S2A and S2B). Fibre‐type analysis showed a marked shift in muscle normally rich in fast glycolytic Type IIb fibres (GAS) towards a higher proportion of Type I fibres (Figure S2C and S2D), but not in SOL (Figure S2C).

Figure 1.

Expression of K320E‐Twinkle in skeletal muscle accelerates the accumulation of mtDNA alterations and mitochondrial dysfunction. (A) Long‐range PCR analysis showing multiple species of altered mtDNA in soleus (SOL) of 24‐month‐old K320Eskm mice. (B) qPCR analysis of three deletions (sum of Del 1, 3 and 17) in SOL, extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and gastrocnemius (GAS) muscles at 24 months of age. (C) qPCR analysis of K320Eskm GAS, showing ageing‐dependent increase in deletion levels (sum of Del 1, 3 and 17). (D) Representative cross sections, showing COX‐deficient (COX− and COX− /SDH++ (white *) fibres in various hindlimb muscles at 24 months (TA, tibialis anterior). (E–H) COX‐deficient fibre quantification showing accelerated and age‐dependent increase of mitochondrial dysfunction. n = 3–6 mice/group were used for deletions analyses and n = 6–10 mice/group to quantify the proportion of COX− fibres. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, ***P < 0.001. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Table 1.

Cytochrome oxidase (COX) deficiency (%) in different hindlimb skeletal muscles

| 12 months | 18 months | 24 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle | Control | K320E‐Twinkleskm | Control | K320E‐Twinkleskm | Control | K320E‐Twinkleskm | P value |

| Soleus | 0 | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 0 | 1.4 ± 1.02 | 0 | 4.36 ± 0.59 | <0.0001 |

| GAS | 0 | 0.46 ± 0.25 | 0 | 5 ± 3 | 0 | 17.08 ± 3.23 | <0.0001 |

| TA | 0 | 0.2 ± 0.07 | 0 | 1.18 ± 0.24 | 0 | 13.58 ± 1.22 | <0.0001 |

| EDL | 0 | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 0 | 0.13 ± 0.05 | 0 | 3.03 ± 1.1 | <0.0001 |

All values are mean ± SEM.

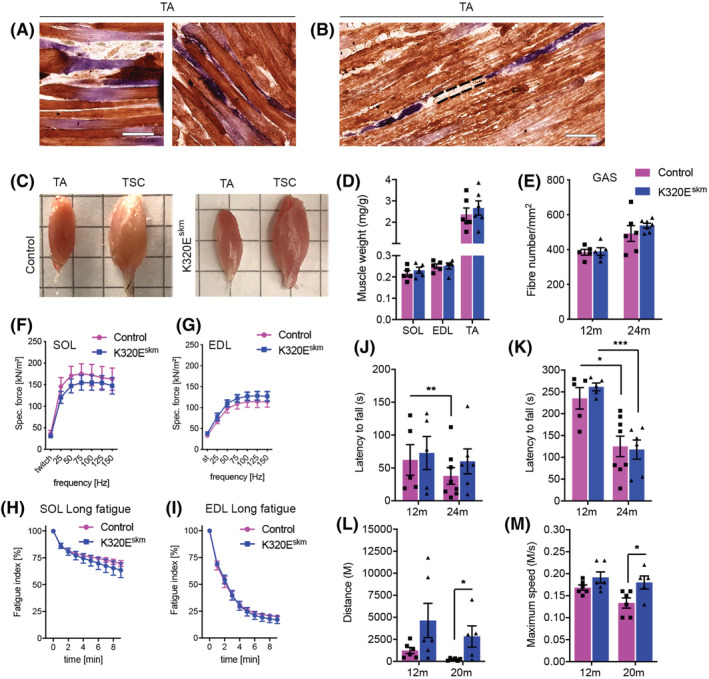

K320Eskm mice show normal mass, physical performance and force generation of isolated muscles

Longitudinal sections showed atrophic regions in some COX− fibres in K320Eskm mice (Figure 2A) or even loss of muscle segments (Figure 2B, dashed lines), like in normally aged muscles of rat and humans. 5 However, the gross morphology of TA and of the entire triceps surae complex (TSC) and muscle mass of TA, EDL and SOL were not altered (Figure 2C and 2D). Moreover, the fibre number per area in GAS was similar at 12 and 24 months of age (Figure 2E). Collectively, these results indicated that the defects induced by mtDNA alterations in a small but relevant percentage of myofibres were not sufficient to cause accelerated loss of whole muscle mass.

Figure 2.

mtDNA alteration‐induced defects in K320E‐Twinkleskm do not affect muscle mass and function. (A) COX/SDH staining showing atrophic COX−/SDH++ fibres in TA muscle. (B) COX−/SDH++ fibres with discontinuous segments in TA. (C) Gross morphology of TA and TSC (triceps surae complex). (D) Wet muscle weight normalized to body weight. (E) Fibre numbers per unit area in GAS. (F,G) Ex vivo specific twitch and tetanic force generation in SOL (F) and EDL (G). (H,I ) Rate of fatigue development in SOL (H) and EDL (I) during 10 min of repetitive tetanic electrical stimulation ex vivo. The maximal specific tetanic force generated was determined from the plateau of the force–frequency curves. The fatigue index was determined by dividing the forces recorded at the beginning by the forces recorded at the end of the protocols. (J) Latency to fall on the very first rotarod trial and (K) after 3 days of training on rotarod. (L) Total distance run on treadmill and (M) maximum speed attained. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; number of animals: rotarod test n = 5‐6 mice/group, treadmill test n = 5–6 mice/group, ex vivo fatigue test n = 6–7 mice/group, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar 100 μm.

To determine whether mitochondrial dysfunction impacts muscle strength independently of mass, we measured isometric force generation ex vivo in EDL and SOL isolated from 24‐month‐old mice. These muscles are enriched in Type IIb and Type I/IIa fibres, respectively. Both isometric twitch force and capacity to increase force following tetanic stimulation at increasing frequencies were similar between K320Eskm and control mice (Figure 2F and 2G). There was also no difference in the rate of fatigue development (Figure 2H and 2I). Normalized cross‐sectional areas (CSA) showed no difference for EDL and SOL between mutant and control mice (Figure S2E).

To investigate muscle function in vivo, we performed accelerating rotarod and forced treadmill exercise. As shown in Figure 2J, the latency to fall on the first trial and after 3 days of training (Figure 2K) was similar, both at 12 and 24 months of age. There was a significant drop in latency to fall at 24 months in both groups (Figure 2K), indicating that the exacerbated accumulation of mtDNA deletions in the mutants did not accelerate the normal ageing‐dependent decline in motor coordination and balance. Running performance on a treadmill was also not impaired in K320Eskm mice. In fact, at 20 months of age, K320Eskm mice performed better than controls, as evidenced by a significantly higher total distance ran (Figure 2L, P = 0.0321) and maximal speed attained (Figure 2M, P = 0.0408) on the treadmill. In summary, despite accumulating up to 17% of COX‐deficient fibres in some muscles, whole muscle mass and motor performance were not compromised in K320Eskm mice.

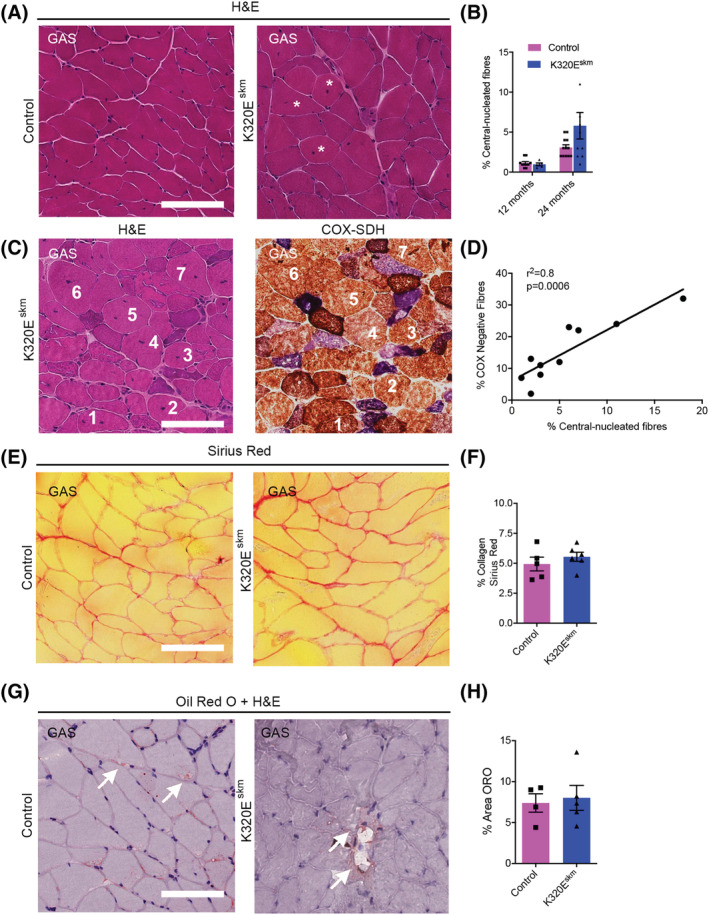

K320Eskm mice display signs of muscle regeneration but no signs of tissue deterioration

Mice maintain robust skeletal muscle regeneration capacity even at 28 months of age. 19 , 20 We therefore hypothesized that activation of MuSCs might have effectively counteracted loss of damaged fibres, thereby preventing loss of muscle mass and function even in old K320Eskm mice. Thus, we quantified newly generated fibres in GAS, identified as being central‐nucleated, which carried the highest burden of COX− fibres. As shown in Figure 3A and 3B, there was a tendency towards an increased proportion of central‐nucleated fibres (white asterisks) in K320Eskm muscles compared with controls (not significant, P = 0.094). However, consecutive sections stained for H&E or COX activity showed that all these central‐nucleated fibres were COX positive (Figure 3C) and a strong positive correlation between the percentage of COX‐deficient vs. the central‐nucleated fibres (Figure 3D, r2 = 0.8, P = 0.006). Finally, Sirius Red and Oil Red O histochemical analyses did not reveal increased fibrosis and fat cell infiltration, respectively (Figure 3E–H). Collectively, these findings suggest that myofibre degeneration induced by mtDNA alterations in K320Eskm mice might have activated compensatory regeneration processes by resident muscle stem cells to maintain muscle mass and function.

Figure 3.

Histochemical analysis for regeneration, fibrosis and fat infiltration in gastrocnemius muscle. (A) Representative H&E pictures showing general tissue structure in GAS of 24‐month‐old mice, white asterisks depict fibres with central nuclei. (B) Percentage of central‐nucleated fibres (12 months; n = 5 mice/per group, 24 months; n = 10–12 mice/group). (C) Serial sections stained with H&E and for COX‐SDH showing COX‐competent, regenerated (central nuclei) fibres (numbers depict same fibres) and (D) positive correlation between COX deficiency and percentage of central‐nucleated fibres at 24 months. (E) Sirius red staining of GAS and (F) quantification of tissue occupied by collagen fibres. Fibrosis was estimated as the percentage of the relative area positive for Sirius Red staining in photomicrograph fields of 500 × 500 μm.(G) Fat deposition or adipocyte infiltration in GAS of 24‐month‐old mice and (H) quantification of Oil Red O (ORO) area. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 5 mice/group. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Response to mtDNA alterations in skeletal muscle of K320Eskm mice

In order to characterize compensatory processes, we performed whole‐exome RNA sequencing (RNAseq) in TA of 24‐month‐old mice, which carried a large burden of COX− fibres (Figure 1H). A total of 2287 genes were differentially expressed (adjusted P < 0.05; full list available at GEO database 21 (Accession number: GSE199201). Genes that showed differential expression between mutant and control mice with a fold change ≥ 1.5 are listed in Table S1 (upregulated genes) and Table S2 (downregulated genes). Upregulated genes included methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (NADP+ dependent) 2 (Mthfd2), amine oxidase copper containing 1 (Aoc1), sperm‐associated antigen 5 (Spag5), acyl‐CoA thioesterase 2 (Acot2), and also Peo1 encoding Twinkle, as expected from our genetic approach. The top downregulated genes include monocyte to macrophage differentiation associated (Mmd), phospholipase D family, member 5 (Pld5), complement receptor type 2 (Cr2), and adrenoceptor alpha 1A (Adra1a).

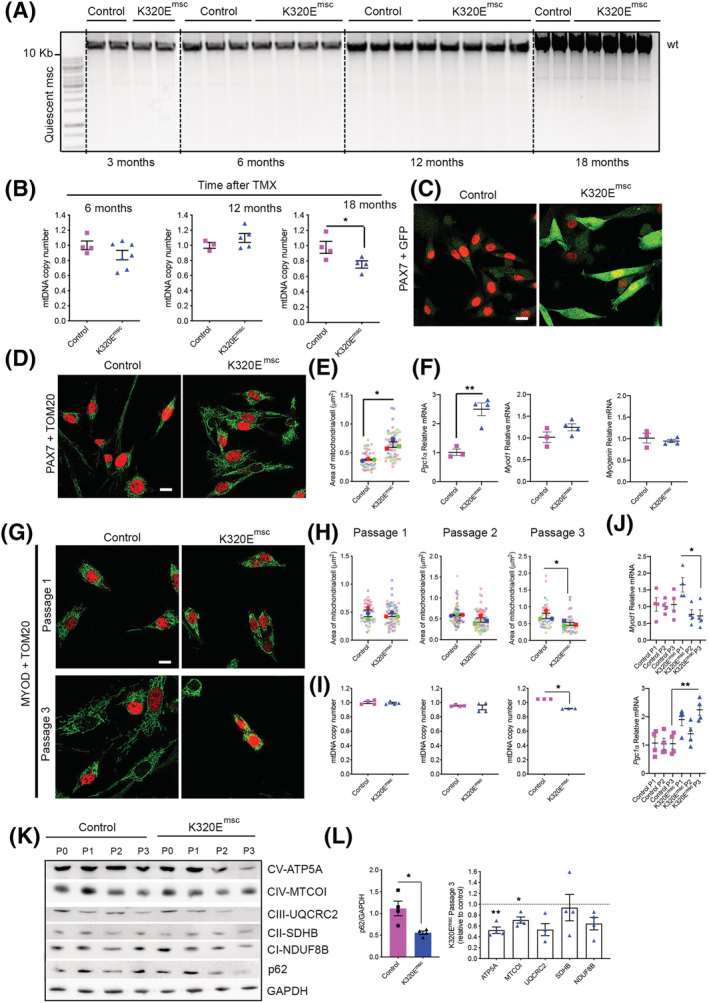

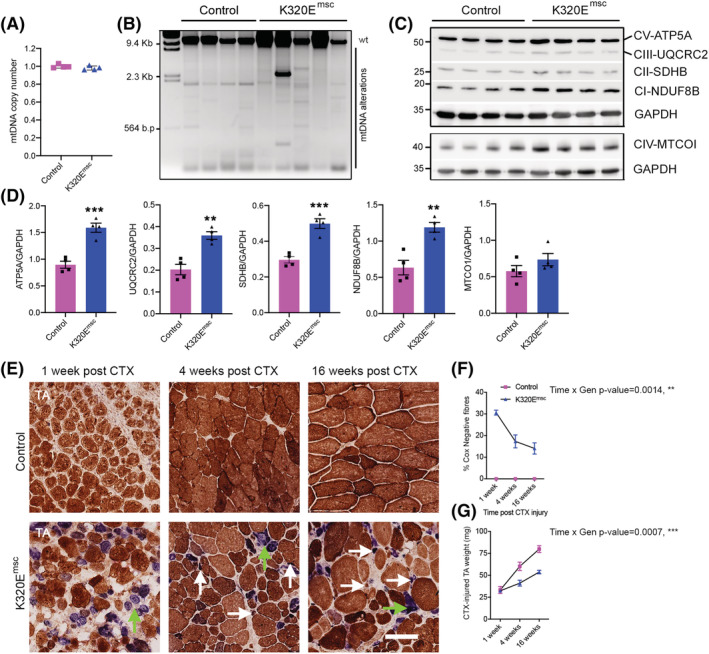

K320E expression in quiescent MuSCs leads to mtDNA depletion after activation

To test the hypothesis that efficient regeneration by MuSCs, which are not affected in K320Eskm mice, is responsible for alleviating the detrimental influence of mtDNA alterations in differentiated fibres, we designed a new conditional model in which expression of K320E‐Twinkle is induced in satellite cells (Pax7CreERT‐mediated recombination, K320Emsc mice).

Expression of the transgene was induced by tamoxifen in 3‐month‐old mice, and MuSCs were isolated and immediately analysed at various ages (Figure 4A). In contrast to differentiated muscles, expression of the mutant helicase in quiescent MuSCs had not resulted in detectable mtDNA alterations, but had led to a significant decrease in mtDNA copy number at 18 months (Figure 4B). Next, K320E‐Twinkle was induced in vitro in MuSCs isolated from 6‐ to 8‐week‐old mice (Figure 4C; GFP‐positive cells). In freshly isolated, quiescent MuSCs (Figure 4D, Passage 0), the area of mitochondria per cell, assessed by TOM20 staining, was higher in K320E‐Twinkle/Pax7 expressing cells (Figure 4E), which also showed increased expression of Pgc1 α mRNA but unchanged expression of Myod1 and Myogenin (Figure 4F), suggesting that compensatory mitochondrial biogenesis had occurred in the quiescent state in vivo without proliferation activation. In contrast, when isolated MuSCs were passaged (Figure 4G), proliferating cells expressing MYOD1 showed a decreased mitochondrial area (Figure 4H) and decreased mtDNA copy number (Figure 4I) at the last passage, despite sustaining high Pgc1 α expression (Figure 4J). Accordingly, expression of index proteins of the respiratory chain complexes I, III and IV, as well as of the ATPase, all containing mtDNA encoded subunits, was decreased at passage 3 (Figure 4K and 4L). Moreover, at this passage, expression of the autophagy adaptor p62 was decreased by 50% in K320E MuSCs (Figure 4L), whereas LC3B‐II levels were unchanged (Figure S3A and S3B). No mtDNA alterations could be detected in control and mutant cells at all investigated passages (data not shown). Last, after differentiation of MuSCs, despite lower levels of Pgc1 α, mtDNA copy number was unchanged in K320E cells, suggesting that in vitro, differentiation is not affected (Figure S3C–S3E).

Figure 4.

K320E‐Twinkle expression in MuSCs leads to mtDNA depletion and increased autophagy. (A) Long‐range PCR for mtDNA alterations and (B) mtDNA copy number quantification in MuSCs isolated at different time points after in vivo tamoxifen (TMX) induction (n = 3–6 mice per time point). (C,D) Representative confocal images of freshly isolated satellite cells from 6‐ to 8‐week‐old mice after 48‐h 4‐hydroxytamoxifen induction. α‐GFP was used to monitor K320E‐Twinkle expression, α‐PAX7 as a satellite cell marker and α‐TOM20 as a mitochondrial marker. (E) Quantification of the area occupied by mitochondria in PAX7+ cells. (F) Expression of Pgc1α, Myod 1 and Myogenin in freshly isolated satellite cells from 6‐ to 8‐week‐old mice after 48 h hydroxytamoxifen induction. (G) Confocal images of proliferative satellite cells at the indicated time points. α‐MYOD was used as a MuSC proliferation marker. (H) Quantification of the area occupied by mitochondria in MYOD+ cells. (I) mtDNA copy number analysis in MuSCs at the indicated passage. (J) Expression of Pgc1α and Myod1 in MuSCs at the indicated passage. (K,L) Western blot analysis and relative quantification of respiratory chain proteins and p62 after three passages in MuSCs total protein extracts (P, passage). GAPDH was used as a loading control. N = 4 mice. Data is expressed as mean ± SEM. For image analysis n = 3 mice, >15 cells per mouse. *P < 0.05. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Altogether, our results indicate that expression of the mutant helicase is well tolerated in quiescent MuSCs, but progressively leads to mtDNA depletion when the cells are forced to proliferate in culture, possibly caused by an increased removal of mitochondria at later stages.

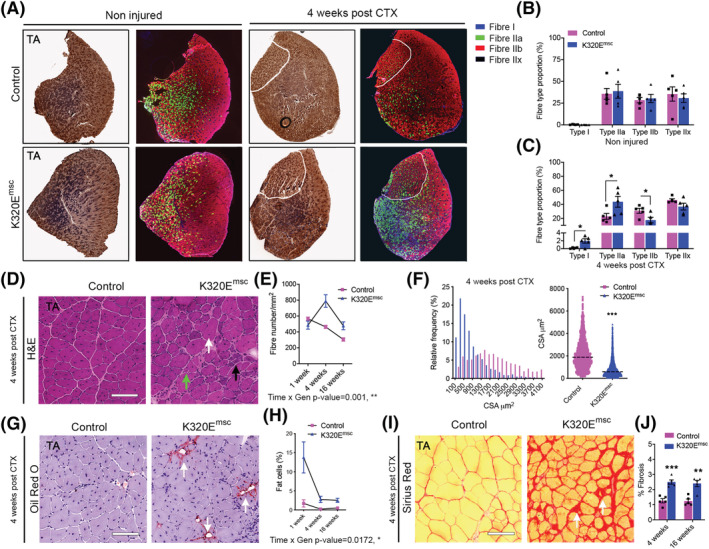

Muscle regeneration is impaired in K320Emsc mice in vivo and leads to a reduction of muscle mass and fibre type shift

Next, to activate MuSCs in vivo, muscle regeneration was triggered in K320Emsc mice by cardiotoxin injection. After 1 week of regeneration, mtDNA copy number was unchanged in mutant muscles (Figure 5A), but mtDNA alterations could be observed (Figure 5B), in striking contrast to induced, but quiescent MuSCs, even after 18 months (Figure 4A). Remarkably, index subunits of the respiratory chain complexes were increased in regenerated mutant muscles (Figure 5C and 5D), containing a striking accumulation of often clustered COX− fibres, up to 30% at 7 days of regeneration (Figure 5E) and gradually decreasing to 15% at 16 weeks (Figure 5F). However, muscle mass remained 30% lower compared with the regenerated muscle of control mice (Figure 5G). Interestingly, a similar 15% of COX− fibres was observed in K320Eskm mice at 24 months, which however showed no loss of muscle mass with ageing (Figure 1H). As expected, fibre type composition remained unchanged in non‐injured muscles of both genotypes (Figure 6A and 6B). In contrast, after 1 month of regeneration, K320Emsc mice showed a fibre type shift with an increased proportion of fibre types I and IIA and a decreased proportion of glycolytic fibres of Type IIB (Figure 6A and 6C and Figure S3F). Fibre Types I and IIA are characterized by a predominantly oxidative metabolism and a high mitochondrial content in mice, in line with the observed higher levels of respiratory chain subunits (Figure 5C and 5D). Quantitative analysis revealed a significant increase in fibre number over time (Figure 6D and 6E) and significantly decreased cross‐sectional areas (Figure 6F) in mutant mice. Moreover, Oil Red O and Sirius Red staining showed increased fat cell infiltration (Figure 6G and 6H) and fibrosis (Figure 6I and 6J), respectively, in the regenerated muscle from K320Emsc mice compared with controls 4 and 16 weeks post regeneration. Last, inflammation was enhanced in regenerated mutant muscle after 1 week, as we observed increased infiltration of macrophages (Figure S4A and S4B), and basophils (Figure S4C and S4D), as well as upregulation of Il6 and Ifnβ mRNA (Figure S4E). Thus, expression of K320E‐Twinkle in MuSCs induces mtDNA alterations only upon their activation, which consequently severely impairs their regenerative capacity, leading to changes in muscle architecture and decreased muscle mass.

Figure 5.

K320E‐Twinkle expression in MuSCs causes mtDNA alterations and COX− fibres upon regeneration. (A) mtDNA copy number analysis and (B) long‐range PCR for mtDNA deletion screening in regenerated muscles from control and K320Emsc mice. (C,D) Western blot analysis and quantification of respiratory chain proteins in 7 days regenerated TA. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (E) Representative cross sections of regenerated TA muscles at the indicated time points stained for COX/SDH activity. COX‐deficient fibre grouping is depicted by green arrows; white arrows depict atrophic fibres. (F) Quantitative analysis showing time‐dependent decrease of COX‐deficient fibres in regenerated K320E‐Twinklemsc TA muscle. (G) Analysis of absolute weights of the regenerated TA muscles in control and mutants. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Figure 6.

Mitochondrial DNA alterations in MuSCs impairs regeneration. (A) Representative cross sections of control and regenerated TA muscles stained for COX/SDH activity and for fibre types. α‐MyHC‐I, α‐MyHC‐2A and α‐MyHC‐2B were used a marker for Type I, Type IIa and Type IIb fibres. Fibre Type IIx was determined by negative staining. (B) Fibre type composition of the contralateral non‐injured TA muscles and (C) 4 weeks post CTX injury. (D) Representative H&E pictures of injured muscle area in both mutant and control mice showing presence of regenerated fibres with central nuclei (white arrows), non‐muscle cell infiltrates (black arrows) and severely atrophic fibres (green arrows). (E) Analysis of fibre number per unit injured areas. (F) Analysis of cross‐sectional area distribution 4 weeks after regeneration. (G,H) Oil red O staining showing increased adipocyte infiltration in mutant mice at 4 weeks and quantitative analysis of fat cells in the injured TA muscles areas at 1, 4 and 16 weeks post injury. (I,J) Sirius red staining showing increased fibrosis at 4 weeks and quantitative analysis of fibrosis in the injured TA muscles areas at 4 and 16 weeks. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

In muscle of humans, monkeys, rats and mice as well as in other organs such as liver, heart and brain, ageing leads to the accumulation of mtDNA mutations, mostly deletions and gene duplications, and is considered to be a hallmark of the ageing process. 22 , 23 In long‐lived species, but not in mice, muscle fibre segments devoid of COX activity have been observed in old animals and have been postulated to be an important factor leading to sarcopenia. 2 , 24 In order to accelerate the formation of mtDNA alterations and study their contribution to sarcopenia in mice, we expressed specifically in skeletal muscle the dominant negative mutation K320E of the mitochondrial helicase Twinkle, which leads to the severe SANDO syndrome where patients present mtDNA deletions and suffer from myopathy. 25

Surprisingly, the regular ageing‐related decline in physical performance also observed in old humans was not accelerated in K320Eskm mice, although up to 17% COX− fibres were observed in muscle cross sections, implying that almost every fibre suffers from severe mitochondrial dysfunction in some segments along its longitudinal axis. In contrast, patients carrying a similar burden of COX− fibres complain about exercise intolerance and rapid muscle fatigue. Because the Twinkle mutation is present in every cell in patients, unlike in our mouse model, our results suggest that these symptoms may result from a combination of systemic and muscle intrinsic defects.

Due to ongoing regeneration from MuSCs, we also did not observe hallmarks of sarcopenia in K320Eskm mice, such as loss of muscle mass, fat infiltration or fibrosis. Consistent with enhanced presence of centrally nucleated fibres (Figure 3B), we found upregulation of the Myh8 (+1.41‐fold, P = 0.005784) and Myh3 (+1.37‐fold, P = 0.024631) genes in K320Eskm mice, which encode neonatal and embryonic myosin heavy chains, respectively. These isoforms are expressed early and transiently during muscle regeneration in adult mammals. 26 Moreover, GO enrichment analysis of all the differentially expressed genes also demonstrated significant enrichment of genes associated with cell proliferation processes (Figure S5, Panel B).

One major response to mtDNA alterations that recently emerged in the ‘deletor mouse’ model, which expresses a different mutant of Twinkle in the whole body, 27 is activation of an mTORC1‐driven integrated stress response (ISR), leading to induction of de novo serine and mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate (mTHF) biosynthetic pathways and de novo nucleotide synthesis and asparagine synthetase. 28 As expected, these pathways are also activated in muscle of K320Eskm mice, indicated by induction of the genes encoding the de novo serine synthesis enzyme phosphoserine aminotransferase‐1 (Psat1) as well as enzymes of the mTHF pathway (Shmt2, Mthfd2, and Mthfd1l) (Table S1). Increased activity of mTORC1 signalling promotes skeletal muscle protein synthesis, 29 and indeed, gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of all the 2287 differentially expressed genes showed that various terms associated with protein synthesis (translation, positive regulation of transcription, ribosome biogenesis and tRNA amino acylation) were over‐represented among the significantly enriched ‘biological process’ (BP) categories (Figure S5, Panel B). The terms ribosome and intracellular ribonucleoprotein were also among the top most five enriched ‘cellular components’ (CC) (Figure S5, Panel A), and terms associated with protein synthesis including structural constituent of ribosomes, poly(A) RNA binding and amino‐acyl tRNA ligase activity were also among the most enriched ‘molecular function’ (MF) gene ontology terms (Figure S5, Panel C). Therefore, the persistent activation of mTORC1 in K320Eskm muscle is obviously important to maintain fibre size in the affected fibre segments. In agreement, treatment of ‘deletor mice’ with rapamycin, an mTORC1 inhibitor, alleviated most of the genetic and other alterations and reverted the progression of histological mitochondrial myopathy. 28

However, in order to maintain normal muscle mass, protein synthesis and degradation processes have to be dynamically balanced. Notably, our RNAseq results also revealed significant upregulation of genes encoding key transcription factors that are known to promote muscle protein degradation including forkhead box‐3 (Foxo‐3; +1.37‐fold, P = 0.001435), Foxo‐1 (+1.45‐fold, P = 0.007729) and Kruppel‐like factor 15 (Klf15; (1.23‐fold, P = 0.019095). FOXO1 and FOXO3 promote autophagy and protein turnover mediated by the ubiquitin proteasomal system (UPS). 30 , 31 , 32 KLF15 is an upstream factor of glucocorticoids that drive muscle protein catabolism. 33 The muscle‐specific ubiquitin ligase gene Murf1, genes encoding various subunits of the proteasome, lysosomal proton pumps and Calpains F and D were also upregulated in skeletal muscles of K320Eskm mice. Other differentially expressed genes are listed in Tables S1 and S2. Altogether, these results indicated induction of both anabolic and catabolic gene programs in the muscles of our K320Eskm model, leading to increased protein turnover in the constantly regenerating muscles.

Our data suggest that ongoing regeneration from the stem cell pool protects muscle from developing sarcopenia and contractile dysfunction, despite the high burden of mtDNA alterations and COX− segments. Therefore, we asked if accumulation of such mutations in MuSCs would impair regeneration. Surprisingly, expression of the mutant helicase in quiescent MuSCs had not resulted in detectable accumulation of mtDNA mutations over time in vivo (Figure 4A), not even 18 months after induction of its expression. Because K320E‐Twinkle induces mtDNA alterations during the replication process, this either indicates an extremely slow mtDNA replication rate in the quiescent state of MuSCs or efficient mtDNA quality control mechanisms, much more efficient than those in differentiated muscle. However, 18 months after its induction, K320E‐Twinkle expression led to a significant decrease in mtDNA copy number (Figure 4B), indicating either a slowing down of the mtDNA replication rate due to the slow unwinding activity of K320E‐Twinkle or an exacerbated activation of quality control mechanisms (e.g. mitophagy), which are induced upon an increased mtDNA mutation load. 34

Interestingly, freshly isolated K320E‐MuSCs showed an increased mitochondrial area and upregulation of Pgc1α, indicating stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis (Figure 4E), a response frequently observed following even mild mitochondrial dysfunction. In contrast, isolated MuSCs subjected to three passages to simulate activation (Figure 4G) showed a decreased mitochondrial mass (Figure 4H), decreased mtDNA copy number (Figure 4I) and consequently diminished respiratory chain subunit levels (Figure 4K and 4L) when expressing K320E‐Twinkle. These data, together with decreased levels of the adapter protein p62 (Figure 4K and 4L) at the latest passage suggest an increased mitochondrial turnover, presumably activated to eliminate an excess of mtDNA damage. Consistently, no mtDNA alterations were found. Therefore, mtDNA alterations accumulate only in non‐dividing and terminally differentiated cells. This phenomenon is also observed in patients suffering from mitochondrial disease, in which invasive and painful muscle biopsies are the gold standard for diagnosis because mtDNA mutations are not present in proliferative blood cells. 35 Besides regulating autophagy, p62 is essential to activate OXPHOS‐induced selective mitophagy. 36 Because K320E‐ MuSCs suffer from a lack of mtDNA encoded OXPHOS subunits, the marked p62 downregulation, without changes in the autophagy marker LC3B‐II, in proliferating cells might be reflecting a selective mechanism in charge of specific mitochondrial turnover. Hence, our results confirm that proliferating cell types—but most importantly also quiescent stem cells—have specific mechanisms to purify the mitochondrial pool from mutated mtDNA molecules. Nevertheless, further experiments to identify the molecular players of these mechanisms are needed.

Finally, induction of muscle regeneration showed that during the massive expansion of the mitochondrial pool, necessary when small quiescent MuSCs differentiate into large muscle fibres, mtDNA alterations accumulated in K320Emsc muscles and led to a marked accumulation of COX− fibres, reaching proportions of up to 30% (Figure 5F). Many of the newly formed fibres disappear in the following recovery period, and, after 16 weeks, only 15% of COX− fibres are left. Importantly, the regenerated muscle in K320Emsc mice does not regain the same mass compared with the contralateral, non‐injured muscle or to those of control mice (Figure 5G). This is in part due to a fibre type shift from large, glycolytic Type IIb fibres to small‐diameter oxidative IIa and Type I fibres (Figure 6C), also seen by increased respiratory chain subunit levels in regenerated muscle (Figure 5D). However, the lower mass is mainly due to atrophy and the partial loss of COX− fibres, as demonstrated by a higher fibre number per unit area in K320Emsc mice and a decreased CSA (Figure 6E and 6F). The fibre type switch alone does not account for the loss of mass, because even if fibre types IIa and I are increasing in number, they are atrophic and smaller compared with the same types in control mice and even some COX‐competent cells are smaller in size. In addition, fat infiltration and fibrosis occurs during regeneration, indicating mtDNA alterations as one of the intrinsic factors that impairs MuSCs‐mediated regeneration (Figure 6G–J). Importantly, fibrosis and fat infiltration are also observed in human sarcopenia. 37 , 38 During its development, the loss of mass is mainly due to atrophy of large glycolytic Type IIx fibres and to a minor extent due to their preferential loss and a similar initial fibre type switch to Type I, which however are also lost later in humans. 39 , 40 Altogether, our results suggest that the accumulation of mtDNA alterations in myofibres activates regeneration during ageing, ultimately leading to sarcopenia if such alterations had been present at low levels in MuSCs as well and expanded during the regeneration process.

Funding

SK was supported by Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD 91524219); RJW was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, SFB 1218/TP B07 and Cologne Excellence Cluster on Cellular Stress Responses in Aging‐associated Diseases – CECAD); ORB and RJW were supported by Agence Nationale de la Recherche/Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, ANR‐20‐CE92‐0020 DPM and RJW were supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft PL895/1‐1 and Köln Fortune 34/2019 Medizinische Fakultät, Universität zu Köln.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Supporting information

Figure S1: Localization of deletions 1, 3 and 17 relative to the D‐loop on Mus musculus mitochondrial DNA. Deletion 1 (position 9089–12976), deletion 3 (position 9554–13299) and deletion 17 (position 1100–4934) have been mapped using the SnapGene® software (from Insightful Science; available at snapgene.com)

Figure S2: Histochemical analysis for ragged red fibers and fiber type composition in gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. A, B) Modified Gomori trichome analysis and quantification showing increased presence of ragged red fibers (RRF) in 24 month GAS and SOL of K320Eskm (white arrows). C) Histochemical analysis of mATPase showing increased numbers of type I fibers (dark stained fibers) in red lateral head GAS (red LGas) as well as red medial head GAS (red MGas) of K320Eskm mice. D) Fiber type I proportion in red GAS of 24 month‐old mice stained by mATPase histochemistry. E) Normalized cross sectional areas values for 24‐month‐old Soleus and EDL muscles used in the ex‐vivo isometric force generation and fatigue measurements. Data is expressed as mean±S.E.M, N = 4 mice per group, student t test, **, p < 0.01

Figure S3: Analysis of differentiation markers in isolated MuSCs and fiber type identification in TA muscle. A) Western blot analysis of LC3 isoforms at passage 1(P1), 2 (P2) and 3 (P3), and B) quantification of LC3B‐II after normalization with GADPH signal. C) Bright field images of in vitro proliferative and 14 days differentiated MuSCs. Scale bar, 100 μm. D) mRNA quantification by qPCR of markers for proliferation (MyoD1 and Myogenin), stemness (Pax7) and mitochondrial biogenesis (Pgc1 α) in steady state and differentiated MuSCs. E) Mitochondrial copy number analysis in 14 days differentiated MuSCs. F) Enlarged view for the different fiber types in regenerated control and K320Emsc TA muscles. Scale bar, 100 μm

Figure S4: Analysis of inflammatory cell types and markers in TA muscles after regeneration. A) F4/80 staining in 1 week post CTX regenerated muscles. Scale bar, Upper images, 0.5 mm; lower images 100 μm. B) Percentage of the total muscle area occupied by F4/80 staining. n = 3 mice per genotype. C) Toluidine blue staining showing basophils infiltration. Scale bar, 100 μm. D) Relative number of TBA positive foci. n = 3–5. E) qPCR analysis of mRNA levels of Il1b, Il6 and Ifnβ. Data is expressed as mean±S.E.M, Student's t test, *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Figure S5: Gene ontology and KEGG pathway analysis of differentially regulated genes in 24‐month‐old TA muscles. A) Cellular component, B), biological process, C) molecular function and, D) over represented KEGG pathways

Table S1: Up‐regulated genes in K320Eskm versus Control (fold change ≥ 1.5 fold)

Table S2: Down regulated genes in K320Eskm versus Control (fold change ≥ 1.5 fold)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank S.J. Burden (Helen L. and Martin S. Kimmel Center for Biology and Medicine at the Skirball Institute of Biomolecular Medicine, New York University Medical School, New York) for generously donating MLC1f‐Cre mice. The authors also thank Dr Peter Frommolt for help with bioinformatics and Théophile Thibault for critical reading of the manuscript. We would like to thank Prerana Wagle for preparing the RNAseq files for submission to GEO. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Kimoloi S., Sen A., Guenther S., Braun T., Brügmann T., Sasse P., Wiesner R. J., Pla‐Martín D., and Baris O. R. (2022) Combined fibre atrophy and decreased muscle regeneration capacity driven by mitochondrial DNA alterations underlie the development of sarcopenia, Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 13, 2132–2145, 10.1002/jcsm.13026

Contributor Information

Sammy Kimoloi, Email: kimoloi@mmust.ac.ke.

David Pla‐Martín, Email: dplamart@uni-koeln.de.

References

- 1. Spinelli JB, Haigis MC. The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nat Cell Biol 2018;20:745–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bua EA, McKiernan SH, Wanagat J, McKenzie D, Aiken JM. Mitochondrial abnormalities are more frequent in muscles undergoing sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2002;92:2617–2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Herbst A, Pak JW, McKenzie D, Bua E, Bassiouni M, Aiken JM. Accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations in aged muscle fibers: Evidence for a causal role in muscle fiber loss. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007;62:235–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herbst A, Lee CC, Vandiver AR, Aiken JM, McKenzie D, Hoang A, et al. Mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations increase exponentially with age in human skeletal muscle. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021;33:1811–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bua E, Johnson J, Herbst A, Delong B, McKenzie D, Salamat S, et al. Mitochondrial DNA‐deletion mutations accumulate intracellularly to detrimental levels in aged human skeletal muscle fibers. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:469–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wanagat J, Cao Z, Pathare P, Aiken JM. Mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations colocalize with segmental electron transport system abnormalities, muscle fiber atrophy, fiber splitting, and oxidative damage in sarcopenia. FASEB J 2001;15:322–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brierley EJ, Johnson MA, Lightowlers RN, James OF, Turnbull DM. Role of mitochondrial DNA mutations in human aging: Implications for the central nervous system and muscle. Ann Neurol 1998;43:217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McKiernan SH, Colman R, Lopez M, Beasley TM, Weindruch R, Aiken JM. Longitudinal analysis of early stage sarcopenia in aging rhesus monkeys. Exp Gerontol 2009;44:170–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang YX, Rudnicki MA. Satellite cells, the engines of muscle repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011;13:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang H, Ryu D, Wu Y, Gariani K, Wang X, Luan P, et al. NAD(+) repletion improves mitochondrial and stem cell function and enhances life span in mice. Science 2016;352:1436–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Englund DA, Murach KA, Dungan CM, Figueiredo VC, Vechetti IJ Jr, Dupont‐Versteegden EE, et al. Depletion of resident muscle stem cells negatively impacts running volume, physical function, and muscle fiber hypertrophy in response to lifelong physical activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2020;318:C1178–C1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bothe GW, Haspel JA, Smith CL, Wiener HH, Burden SJ. Selective expression of Cre recombinase in skeletal muscle fibers. Genesis 2000;26:165–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baris OR, Ederer S, Neuhaus JF, von Kleist‐Retzow JC, Wunderlich CM, Pal M, et al. Mosaic deficiency in mitochondrial oxidative metabolism promotes cardiac arrhythmia during aging. Cell Metab 2015;21:667–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gunther S, Kim J, Kostin S, Lepper C, Fan CM, Braun T. Myf5‐positive satellite cells contribute to Pax7‐dependent long‐term maintenance of adult muscle stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2013;13:590–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bruegmann T, van Bremen T, Vogt CC, Send T, Fleischmann BK, Sasse P. Optogenetic control of contractile function in skeletal muscle. Nat Commun 2015;6:7153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lynch GS, Hinkle RT, Chamberlain JS, Brooks SV, Faulkner JA. Force and power output of fast and slow skeletal muscles from mdx mice 6‐28 months old. J Physiol 2001;535:591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Basu S, Xie X, Uhler JP, Hedberg‐Oldfors C, Milenkovic D, Baris OR, et al. Accurate mapping of mitochondrial DNA deletions and duplications using deep sequencing. PLoS Genet 2020;16:e1009242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oexner RR, Pla‐Martín D, Paß T, Wiesen MHJ, Zentis P, Schauss A, et al. Extraocular muscle reveals selective vulnerability of type IIB fibers to respiratory chain defects induced by mitochondrial DNA alterations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2020;61:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee AS, Anderson JE, Joya JE, Head SI, Pather N, Kee AJ, et al. Aged skeletal muscle retains the ability to fully regenerate functional architecture. Bioarchitecture 2013;3:25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shavlakadze T, McGeachie J, Grounds MD. Delayed but excellent myogenic stem cell response of regenerating geriatric skeletal muscles in mice. Biogerontology 2010;11:363–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, et al. NCBI GEO: Archive for functional genomics data sets‐‐Update. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:D991–D995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Larsson NG. Somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in mammalian aging. Annu Rev Biochem 2010;79:683–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lopez‐Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013;153:1194–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aiken J, Bua E, Cao Z, Lopez M, Wanagat J, McKenzie D, et al. Mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations and sarcopenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2002;959:412–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hudson G, Deschauer M, Busse K, Zierz S, Chinnery PF. Sensory ataxic neuropathy due to a novel C10Orf2 mutation with probable germline mosaicism. Neurology 2005;64:371–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. d'Albis A, Couteaux R, Janmot C, Roulet A, Mira JC. Regeneration after cardiotoxin injury of innervated and denervated slow and fast muscles of mammals. Myosin isoform analysis European journal of biochemistry 1988;174:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tyynismaa H, Mjosund KP, Wanrooij S, Lappalainen I, Ylikallio E, Jalanko A, et al. Mutant mitochondrial helicase Twinkle causes multiple mtDNA deletions and a late‐onset mitochondrial disease in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:17687–17692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khan NA, Nikkanen J, Yatsuga S, Jackson C, Wang LY, Pradhan S, et al. mTORC1 regulates mitochondrial integrated stress response and mitochondrial myopathy progression. Cell Metab 2017;26:419–428.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Egerman MA, Glass DJ. Signaling pathways controlling skeletal muscle mass. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology 2014;49:59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mammucari C, Milan G, Romanello V, Masiero E, Rudolf R, Del Piccolo P, et al. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab 2007;6:458–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yamazaki Y, Kamei Y, Sugita S, Akaike F, Kanai S, Miura S, et al. The cathepsin L gene is a direct target of FOXO1 in skeletal muscle. Biochem J 2010;427:171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, Cao P, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, et al. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab 2007;6:472–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shimizu N, Yoshikawa N, Ito N, Maruyama T, Suzuki Y, Takeda S, et al. Crosstalk between glucocorticoid receptor and nutritional sensor mTOR in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab 2011;13:170–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Garcia‐Prat L, Martinez‐Vicente M, Perdiguero E, Ortet L, Rodriguez‐Ubreva J, Rebollo E, et al. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature 2016;529:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ahmed ST, Craven L, Russell OM, Turnbull DM, Vincent AE. Diagnosis and treatment of mitochondrial myopathies. Neurotherapeutics 2018;15:943–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Abudu YP, Shrestha BK, Zhang W, Palara A, Brenne HB, Larsen KB, et al. SAMM50 acts with p62 in piecemeal basal‐ and OXPHOS‐induced mitophagy of SAM and MICOS components. J Cell Biol 2021;220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kent‐Braun JA, Ng AV, Young K. Skeletal muscle contractile and noncontractile components in young and older women and men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2000;88:662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kirkeby S, Garbarsch C. Aging affects different human muscles in various ways. An image analysis of the histomorphometric characteristics of fiber types in human masseter and vastus lateralis muscles from young adults and the very old. Histol Histopathol 2000;15:61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lexell J. Human aging, muscle mass, and fiber type composition. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50: Spec No:11‐6. 50A 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Fiber types in mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol Rev 2011;91:1447–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Localization of deletions 1, 3 and 17 relative to the D‐loop on Mus musculus mitochondrial DNA. Deletion 1 (position 9089–12976), deletion 3 (position 9554–13299) and deletion 17 (position 1100–4934) have been mapped using the SnapGene® software (from Insightful Science; available at snapgene.com)

Figure S2: Histochemical analysis for ragged red fibers and fiber type composition in gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. A, B) Modified Gomori trichome analysis and quantification showing increased presence of ragged red fibers (RRF) in 24 month GAS and SOL of K320Eskm (white arrows). C) Histochemical analysis of mATPase showing increased numbers of type I fibers (dark stained fibers) in red lateral head GAS (red LGas) as well as red medial head GAS (red MGas) of K320Eskm mice. D) Fiber type I proportion in red GAS of 24 month‐old mice stained by mATPase histochemistry. E) Normalized cross sectional areas values for 24‐month‐old Soleus and EDL muscles used in the ex‐vivo isometric force generation and fatigue measurements. Data is expressed as mean±S.E.M, N = 4 mice per group, student t test, **, p < 0.01

Figure S3: Analysis of differentiation markers in isolated MuSCs and fiber type identification in TA muscle. A) Western blot analysis of LC3 isoforms at passage 1(P1), 2 (P2) and 3 (P3), and B) quantification of LC3B‐II after normalization with GADPH signal. C) Bright field images of in vitro proliferative and 14 days differentiated MuSCs. Scale bar, 100 μm. D) mRNA quantification by qPCR of markers for proliferation (MyoD1 and Myogenin), stemness (Pax7) and mitochondrial biogenesis (Pgc1 α) in steady state and differentiated MuSCs. E) Mitochondrial copy number analysis in 14 days differentiated MuSCs. F) Enlarged view for the different fiber types in regenerated control and K320Emsc TA muscles. Scale bar, 100 μm

Figure S4: Analysis of inflammatory cell types and markers in TA muscles after regeneration. A) F4/80 staining in 1 week post CTX regenerated muscles. Scale bar, Upper images, 0.5 mm; lower images 100 μm. B) Percentage of the total muscle area occupied by F4/80 staining. n = 3 mice per genotype. C) Toluidine blue staining showing basophils infiltration. Scale bar, 100 μm. D) Relative number of TBA positive foci. n = 3–5. E) qPCR analysis of mRNA levels of Il1b, Il6 and Ifnβ. Data is expressed as mean±S.E.M, Student's t test, *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Figure S5: Gene ontology and KEGG pathway analysis of differentially regulated genes in 24‐month‐old TA muscles. A) Cellular component, B), biological process, C) molecular function and, D) over represented KEGG pathways

Table S1: Up‐regulated genes in K320Eskm versus Control (fold change ≥ 1.5 fold)

Table S2: Down regulated genes in K320Eskm versus Control (fold change ≥ 1.5 fold)