Abstract

Introduction:

Despite the increasing vaccination coverage, COVID-19 is still a concern. With the limited health care capacity, early risk stratification is crucial to identify patients who should be prioritized for optimal management. The present study investigates whether on-admission lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio (LAR) can be used to predict COVID-19 outcomes.

Methods:

This retrospective cross-sectional study evaluated hospitalized COVID-19 patients in an academic referral center in Iran from May 2020 to October 2020. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) was used to evaluate the value of LAR in the prediction of mortality. The Yuden index was used to find the optimal cut-off of LAR to distinguish severity. Patients were classified into three groups (LAR tertiles), first: LAR<101.46, second: 101.46≤LAR< 148.78, and third group: LAR≥148.78. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify the association between tertiles of LAR, as well as the relationship between each one-unit increase in LAR with mortality and ICU admission in three models, based on potential confounding variables

Results:

A total of 477 patients were included. Among all patients, 100 patients (21%) died, and 121 patients (25.4%) were admitted to intensive care unit (ICU). In the third group, the risk of mortality and ICU admission increased 7.78 times (OR=7.78, CI: 3.95-15.26; p <0.0001) and 4.49 times (OR=4.49, CI: 2.01-9.04; p <0.0001), respectively, compared to the first group. The AUC of LAR for prediction of mortality was 0.768 (95% CI 0.69- 0.81). LAR ≥ 136, with the sensitivity and specificity of 72% (95%CI: 62.1-80.5) and 70% (95%CI: 64.9-74.4), respectively, was the optimal cut-off value for predicting mortality.

Conclusion:

High LAR was associated with higher odds of COVID-19 mortality, ICU admission, and length of hospitalization. On-admission LAR levels might help health care workers identify critical patients early on.

Key Words: Serum Albumin, L-Lactate Dehydrogenase, COVID-19, Prognosis, Emergency Service, Hospital

1. Introduction:

The most recent global pandemic, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is an infectious disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Based on the recent worldwide analysis of COVID-19, more than 5 million attributable deaths were reported till November 2021 (1).

The symptoms of COVID-19 vary in a wide range, from a mild illness to a life-threatening condition. The disease can even be asymptomatic, while the most common clinical symptoms are cough, fever, myalgia, and gastrointestinal symptoms (2, 3). COVID-19 can also cause severe organ failures such as acute cardiac injury, acute kidney injury, acute liver injury, and the most known among all, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). These conditions can lead the patients to a critical state, which requires intensive care unit (ICU) admission and also, in some cases, can cause death (4, 5). Outcomes of COVID-19 patients mainly depend on the severity of the disease. Most individuals with a mild illness had good prognosis (6, 7), while the mortality among critically ill patients was very high (8). According to published data on COVID-19, the mortality rate among severely infected individuals was up to 49% (9). Generally, in septic patients with acute respiratory failure and multiple organ failure, the mortality may increase up to 35-46% and 60-98%, respectively (10-12).

There have been numerous studies investigating factors allowing the prediction of COVID-19 severity. Some demographic characteristics, a wide range of comorbidities, and many laboratory biomarkers were related to the severity and mortality of COVID-19 (13-16).

As a negative acute-phase protein, albumin promotes the formation of anti-inflammatory substances, so it plays an essential role in the prognosis of patients with inflammatory events and inhibition of disease progression (17, 18). Some previous studies have demonstrated that in non-surviving patients with sepsis, albumin levels are lower (19).

Since blood lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level can be determined rapidly as a marker of tissue hypoperfusion, it is widely used in the early risk classification of critical patients admitted to the emergency department (20). Similarly, several studies have shown that reduced serum albumin (Alb) levels and increased lactate dehydrogenase are associated with COVID-19 severity (21-23). Scientists have believed that lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio integrates multi-organ failure, chronic disease, inflammatory, and nutritional factors, which may provide more valuable information than the predictive value of either lactate dehydrogenase or albumin alone (24); however, this has not been sufficiently investigated.

Despite the increasing vaccination coverage worldwide, COVID-19 is still a concern, especially in developing countries. Therefore, early risk stratification is crucial for identifying critical patients who should be prioritized for optimal management and allocating the limited human and technical resources to the suitable patients (25). The present study aims to investigate whether on-admission lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio (LAR) levels can be used as a reliable predictor for clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

2. Methods:

2.1. Study design and patients

This retrospective cross-sectional study, was conducted on hospitalized patients with clinical manifestations of COVID-19 and a positive COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test or chest computed tomography scan (CT-scan) findings consistent with COVID-19, from 1st May 2020 to 31st October 2020, in the Baharloo Hospital affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The current study was performed under the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were anonymized during the data collection process, and due to the study's retrospective nature, informed consent was waived. Ethical feasibility was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, number IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1399.148

2.2. Participants

Patients under 18 years old, with history of the previous COVID-19, and missing data of LDH or Alb in the first 48 hours of hospital admission were excluded. Since the data bank was used, the sample size was not calculated. None of the patients had been vaccinated against COVID-19, as the data gathered for this study belong to the period when vaccination had not started in Iran.

2.3. Data collection

Demographic information (age, sex), comorbidities, initial presentations, type of treatment, laboratory data in the first 48 hours of admission, and outcomes were collected from the medical records. Only the first test value was included if there were multiple laboratory test values.

The co-existing diseases were hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary heart disease (CHD), previous stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), cancer, rheumatoid disease, and hypo/hyperthyroidism. Patients were asked if they had ever been informed of having a diagnosis of any mentioned comorbidities.

The patients were asked if they had experienced fever, chills, myalgia, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Accurate temperature measurement was also done within the first 24 hours of hospital admission to determine if fever was present.

Laboratory results included White Blood Cell (WBC) count, Neutrophil count, Lymphocyte count, Neutrophil to Lymphocyte ratio (NLR), Hemoglobin (Hb), Platelets count (PTL), C-reactive-Protein (CRP), Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR), Blood Sugar (BS), Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN), Albumin (Alb), Creatinine (Cr), and Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH).

The clinical chemistry laboratories at the hospital evaluated the blood samples with standard procedures. Venous blood samples were collected in tubes, including ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid. Serum LDH level was measured using the Hitachi 911 automatic chemistry analyzer (Roche). The LDH concentration was presented as units per liter (U/L). Blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. Serum Alb level was measured using Bromocresol green method and Latex coagulating nephelometric assay. Given that the half-life of albumin is about 25 days, Alb level was included in the study if measured in the first 48 hours of hospital admission. Other biochemical markers were measured using standard methods.

All patients received nursing, nutritional, and respiratory support. Some patients received non-invasive ventilation (NIV), such as nasal oxygen, while some ICU-admitted patients received invasive ventilation. Hydration, fever management, and pain control were considered. In addition, conservative therapy was performed in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Treatment of patients varied according to their clinical conditions. Patients received medications, including NSAIDs, IV Corticosteroids, oral antiviral drugs, and IV antibiotics, according to the COVID-19 diagnosis and treatment protocol designed by the Iran Ministry of Health.

A chest computed tomography (CT) scan was also done for all patients. Bilateral and peripheral ground-glass opacity (GGO), consolidation, reticular pattern, and air bronchogram on chest CT-scan were assumed to be COVID-19 in patients with negative PCR test who had the typical clinical manifestation of COVID-19 (26, 27).

The lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio was named LAR. Patients were classified into three groups based on LAR levels (LAR tertiles). The first group with LAR<101.46 (including 158 patients), the second group with 101.46 ≤ LAR < 148.78 (including 159 patients), and the third group with LAR≥148.78 (including 160 patients).

All the information collection forms were checked for missing data by two researchers, independently. Less than 5% of the total data was missing. Since this amount does not significantly affect results, it was ignored.

2.4. Outcomes

Outcomes included the length of hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and mortality.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (quantitative variables with normal distribution) or median and interquartile range (IQR) (quantitative variables with non-normal distribution), and categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage (number (%)). The chi-square (χ2), one-way ANOVA, and the Kruskal–Wallis test statistic were used to compare categorical, quantitative, and skewed variables according to tertiles of LAR.

Logistic regression analysis was used to identify the association between tertiles of LAR, as well as the relationship between each one-unit increase in LAR with mortality and ICU admission in three models, based on potential confounding variables, which were significantly different between tertiles of LAR. Model one adjusted for age, based on model one, model two added sex, and model three further adjusted for CKD, hyper/hypothyroid, IV Corticosteroids, oral antiviral therapy, IV antibiotics, WBC, NLR, CRP, ESR, BS, O2, BUN, and Cr. The first tertile of LAR was considered a reference point. Follow-up duration was defined as the period between hospital admission and mortality, ICU admission, or discharge. Kaplan-Meyer survival analysis was used to calculate the probability of survival in each class of LAR. Since some data on the time of mortality and ICU admission was missing (in about 80 patients), the logistic regression was used instead of Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. Cox regression analysis was then repeated in a small sample of the population with complete data, and no changes in results were observed. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, and the area under the curve (AUC) were used to evaluate the value of LAR in prediction of mortality. The Yuden index was used to find the optimal cut-off of LAR to distinguish severity. All data were analyzed using Stata 16 software. The significance threshold was considered less than 0.05 (P-value < 0.05).

3. Results:

3.1. Baseline characteristics of studied cases

A total of 477 patients with COVID-19 were eventually found eligible to enter the analysis. Patients were classified into three groups based on LAR levels (LAR tertiles). The first group with LAR<101.46 (including 158 patients), the second group with 101.46≤LAR< 148.78 (including 159 patients), and the third group with LAR≥148.78 (including 160 patients).

The mean age of patients was 58.56 (range: 41 – 76) years. Two hundred and sixty-three patients (55.1%) were male. Age and sex distribution were significantly different between groups with different LARs (p = 0.008 and p = 0.037, respectively). The demographic characteristics, initial symptoms, comorbidities, types of treatment, and laboratory data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparing the demographics, initial symptoms, comorbidities, types of treatment, lab data, and outcome between patients with lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio (LAR) < 101.46 (group 1), 101.46 ≤ LAR < 148.78 (group 2), and LAR ≥ 148.78 (group 3)

| Variables |

Total

(n=477) |

Group1 (n=158) |

Group 2

(n=159) |

Group 3

(n=160) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | 58.56(17.52) | 56.21(18.67) | 57.45(16.8) | 61.98(16.61) | 0.008 |

| Male sex | 263 (55.1) | 78 (49.4) | 84 (52.8) | 101 (63.1) | 0.037 |

| Initial symptoms | |||||

| Cough | 314 (65.8) | 106 (67.1) | 112 (70.4) | 96 (60) | 0.133 |

| Fever | 248 (52) | 77 (48.7) | 82 (51.6) | 89 (55.6) | 0.466 |

| Myalgia | 160 (33.5) | 54 (34.2) | 56 (35.2) | 50 (31.3) | 0.738 |

| Chills | 142 (29.8) | 44 (27.8) | 50 (31.4) | 48 (30) | 0.780 |

| Nausea | 80 (16.8) | 35 (22.2) | 22 (13.8) | 23 (14.4) | 0.086 |

| Anorexia | 66 (13.8) | 16 (10.1) | 22 (13.8) | 28 (17.8) | 0.163 |

| Vomiting | 36 (7.5) | 12 (7.6) | 10 (6.3) | 14 (8.8) | 0.707 |

| Diarrhea | 30 (6.3) | 12 (7.6) | 10 (6.3) | 8 (5) | 0.635 |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Hypertension | 166 (34.8) | 50 (31.6) | 50 (31.4) | 66 (41.3) | 0.110 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 146 (30.6) | 43 (27.2) | 45 (28.3) | 58 (36.3) | 0.161 |

| Chronic heart disease | 86 (18) | 25 (15.8) | 27 (17) | 34 (21.3) | 0.414 |

| History of stroke | 42 (8.8) | 13 (8.2) | 11 (6.9) | 18 (11.3) | 0.375 |

| Hyper/Hypothyroidism | 18 (3.8) | 3 (1.9) | 5 (3.1) | 4 (2.5) | 0.037 |

| COPD | 13 (2.7) | 6 (3.8) | 4 (2.5) | 3 (1.9) | 0.563 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12 (2.5) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.3) | 9 (5.6) | 0.008 |

| Rheumatoid disease | 9 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 5 (3.1) | 3 (1.9) | 0.259 |

| Cancer | 3 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.9) | 0.050 |

| Treatments | |||||

| NSAIDs | 302 (63.3) | 102 (64.6) | 105 (66) | 95 (59.4) | 0.431 |

| IV Antibiotics | 228 (47.8) | 57 (36.1) | 72 (45.3) | 99 (61.9) | <0.0001 |

| Oral antiviral | 171 (35.8) | 32 (20.3) | 57 (35.8) | 82 (51.3) | <0.0001 |

| IV Corticosteroids | 109 (22.9) | 20 (12.7) | 32 (20.1) | 57 (35.6) | <0.0001 |

| Laboratory data | |||||

| WBC (109/L) | 7.54 ±5.57 | 7.22±3.69 | 6.36 ± 3.41 | 9.04 ± 8.00 | <0.0001 |

| Neutrophil (percentage) | 74.39± 11.36 | 70.01 ± 10.25 | 73.77± 10.74 | 79.33± 11.14 | <0.0001 |

| Lymphocyte (percentage) | 20.27± 10.69 | 24.47± 10.01 | 20.94± 10.80 | 15.45± 9.25 | <0.0001 |

| NLR | 5.61± 5.15 | 4.03± 3.73 | 4.91± 4.05 | 7.86± 6.43 | <0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.42± 10.35 | 13.11 ± 1.78 | 14.57± 17.71 | 12.59± 1.91 | 0.210 |

| Platelet Count (109/L) | 211.90±92.57 | 218.21±96.47 | 200.34± 84.91 | 217.16± 95.39 | 0.155 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 47.82± 48.82 | 22.97± 25.07 | 54.64± 70.24 | 65.60± 25.20 | <0.0001 |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 56.68± 29.78 | 43.34± 25.54 | 58.61± 29.13 | 67.94± 29.31 | <0.0001 |

| Blood Sugar (mg/dL) | 151.44±80.57 | 138.24± 61.24 | 160.51±91.91 | 155.47±84.05 | 0.036 |

| Oxygen Saturation (%) | 90.38±7.21 | 91.86± 5.83 | 91.48± 4.89 | 87.82± 9.37 | <0.0001 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 44.63± 29.01 | 36.55± 19.98 | 41.10± 21.61 | 56.11± 38.09 | <0.0001 |

| Serum Creatinine mg/dL) | 1.26±0.68 | 1.10 ± 0.35 | 1.19± 0.62 | 1.48± 0.89 | <0.0001 |

| LDH (unit/L) | 583.07±283.61 | 371.33± 62.85 | 515.33± 74.37 | 859.47±324.64 | <0.0001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.22±0.56 | 4.60±0.36 | 4.27±0.46 | 3.80±0.56 | <0.0001 |

| Outcome | |||||

| Mortality | 100 (21) | 13 (8.2) | 19 (11.9) | 68 (42.5) | <0.0001 |

| ICU admission | 121 (25.4) | 15 (9.5) | 28 (17.6) | 78 (48.8) | <0.0001 |

| Hospital stay (day) | 6 (6) | 6 (5) | 6 (6) | 8 (10) | <0.0001 |

All data are reported as frequency (%), except for age and laboratory results, which are reported as mean ± standard deviation, and hospital stay, which is reported as median (IQR). COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; IV: intravenous; WBC: White Blood Cell count; CRP: C-Reactive Protein; ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; NLR: Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; ICU: intensive care unit.

The initial symptoms among all patients were as follows: cough in 314 patients (65.8%), fever in 248 patients (52%), and the other symptoms had a lower prevalence. The groups were similar in terms of initial symptoms (P > 0.05).

Hypertension (34.8%) and diabetes mellitus (30.6%) were the most common comorbidities. Coexisting comorbidities, including hyper/hypothyroidism and CKD, were significantly different between groups with different LARs (p = 0.037 and p = 0.008, respectively).

The treatment of patients varied according to the patients’ clinical condition. Use of IV corticosteroids, oral antiviral therapy, and IV antibiotics were significantly different between groups with different LARs (p <0.0001).

WBC, neutrophil count, NLR, CRP, ESR, BS, BUN, Cr, and LDH were significantly increased among all laboratory results. In contrast, lymphocyte count, blood oxygen saturation, and Alb were significantly decreased in groups with higher LAR (p <0.0001).

3.2. Outcomes

The outcomes of the population study are shown in table 1. Among all patients, 100 patients (21%) died, 121 patients (25.4%) were admitted to ICU, and 256 patients (53.6%) were discharged. The median length of hospitalization was six days. The mortality rate, ICU admission, and length of hospitalization were significantly different between groups with different LARs (p <0.0001).

After adjustment for CKD, hyper/hypothyroid, IV corticosteroids, oral antiviral therapy, IV antibiotics, WBC, NLR, CRP, ESR, BS, O2, BUN, and Cr (based on potential confounding variables, which were significantly different between tertiles of LAR), in the third group, the risk of mortality increases 7.78 times (OR=7.78, CI (3.95-15.26)) compared to the first group (P-value for trend < 0.0001). Besides, the risk of ICU admission among the patients with LAR ≥ 148.78 was 4.49 times (OR=4.49, CI (2.01-9.04)) compared to those with LAR<101.46 (P-value for trend < 0.0001). The results suggested that each one-unit increase in LAR increases the risk of mortality and ICU admission 1.01 times (1.00-1.02) and 1.02 times (1.02-1.03), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for independent predictive factors of mortality and intensive care unit (ICU) admission among COVID-19 cases after adjustment for potential confounding variables

| Variables |

Group 1

(N=158) |

Group 2

(N=159) |

Group 3

(N=160) |

P* | 1 unit change# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | |||||

| Age | 1 | 1.05 (0.44-2.51) | 3.73 (1.65-8.62) | <0.0001 | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) |

| Age and sex | 1 | 1.52 (1.05-3.26) | 7.90 (4.04-15.43) | <0.0001 | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) |

| Multivariate | 1 | 1.53 (0.73-3.25) | 7.78 (3.95-15.26) | <0.0001 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) |

| ICU Admission | |||||

| Age | 1 | 2.04 (1.03-4.02) | 8.54 (4.57-15.95) | <0.0001 | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) |

| Age and sex | 1 | 2.03 (1.03-4.02) | 8.47 (4.52-15.88) | <0.0001 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) |

| Multivariate | 1 | 1.45(0.65-2.21) | 4.49 (2.01-9.04) | <0.0001 | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) |

*: P value for trend. #: 1-unit increase in LAR. All measures are presented as adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence interval. Group 1: LAR < 101.46, Group 2: 101.46 ≤ LAR < 148.78, and Group 3: LAR ≥ 148.78. LAR: lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio.

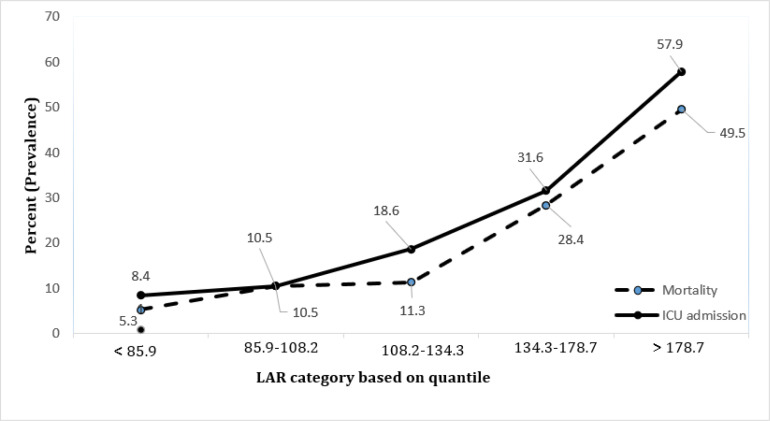

The repetition of this analysis in the more-stratified LAR levels (quantiles of LAR) indicated significantly higher mortality (P-value for trend< 0.0001) and ICU admission (P-value for trend < 0.0001) with increase in LAR. The trends of mortality and ICU admission based on quantiles of LAR are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Trend of mortality and intensive care unit (ICU) admission based on quantiles of lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio (LAR); P < 0.0001 for trend of mortality and P <0.0001 for trend of ICU admission

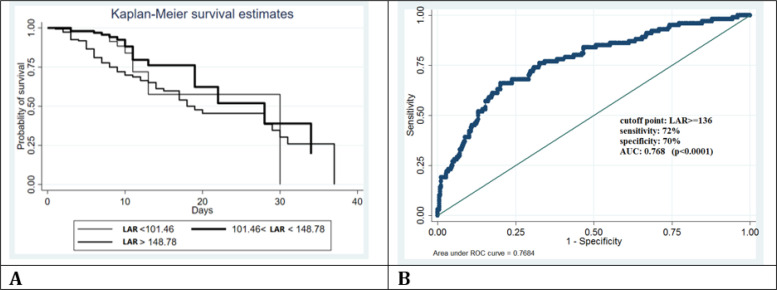

The probability of survival based on tertiles of LAR was estimated using Kaplan Meier method. As shown in figure 2, the probability of survival increases with decrease in LAR, especially in the first fourteen days of hospital admission.

Figure 2.

A: Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of COVID-19 cases based on lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio (LAR); B: Predicting mortality of COVID-19 cases using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for LAR in 136 cut-off point

LAR was taken as a candidate for ROC analysis (figure 3). The AUC of LAR was 0.7684 (95% CI 0.69- 0.81), which indicates that LAR can be an accurate predictor of mortality (p < 0.0001). Using the Yuden index, LAR ≥ 136, with the sensitivity and specificity of 72% (95%CI: 62.1-80.5) and 70% (95%CI: 64.9-74.4), respectively, was the optimal cut-off value in predicting mortality (positive predictive value 38.7 (95%CI: 31.7-46.1), negative predictive value 90.4 (95% CI: 86.4-93.5)).

4. Discussion:

In the present study, the mortality rate, ICU admission, and length of hospitalization were significantly increased in patients with higher LAR. LAR ≥ 136, with the sensitivity and specificity of 72% and 70%, respectively, was the optimal predictive threshold for COVID-19 mortality.

With the limited health care capacity, numerous studies have investigated factors allowing the prediction of COVID-19 severity and mortality in the early stages. The prognostic role of elevated CRP, ESR, BUN, and Cr has been highlighted in several investigations of COVID-19 progression (13, 14, 21, 22). Besides, previous studies indicated that older age, one or more coexisting comorbidities, high WBC, elevated neutrophil count, elevated LDH, lower lymphocyte count, and low serum Alb levels are associated with adverse outcomes in patients with COVID-19 (28-30). The present study's findings showed that in patients with higher LAR, lymphocyte count and serum albumin levels were significantly decreased. In contrast, age, coexisting chronic kidney disease and hyper/hypothyroidism, white blood cell count, neutrophil count, NLR, CRP, ESR, BS, BUN, creatinine, and LDH were significantly increased. Besides, in the current study population, the probability of survival decreased with increase in LAR. In patients with LAR≥148.78, the risk of mortality and ICU admission increased 7.78 and 4.49 times, respectively, compared to those with LAR<101.46.

LDH and albumin are routinely tested and readily available markers in many clinical practices. Since different mechanisms regulate these two biomarkers, LAR can reduce the impact of a single factor on the regulation mechanism (24). Several studies have examined the prognostic role of LAR in many respiratory and infectious diseases.

LAR was independently associated with in-hospital death in a Korean population of patients with severe infections requiring intensive care (31). Similarly, the prognostic role of LAR in patients with lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) who were admitted to an emergency department was explored by Lee BK et al.; LAR was considered an independent prognostic factor for in-hospital mortality in patients with LRTI (32). The predictive value of LAR, particularly in patients with COVID-19, has not been sufficiently investigated. In a recent study conducted in China on 321 COVID-19 patients, LAR was significantly associated with in-hospital death and had a high specificity and sensitivity in differentiating critical patients from mild ones (24).

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, the current study is one of the first investigations to describe a cut-off value for LAR as an influential predictor of COVID-19 severity and mortality. These findings will help healthcare workers identify high-risk patients who should be prioritized and improve COVID-19 survival.

5. Limitation

This study has certain limitations that have to be taken into consideration. First, since this study was retrospective in nature, it thus has innate limitations regarding selection bias. Second, not all laboratory biomarkers with the potential for prognosis have been obtained (such as D-Dimer and ferritin). Third, we only included patients for whom LDH and albumin were measured. Forth, all laboratory data were obtained in the first 48 hours of hospital admission; thus, a single measurement may have limited prognostic value, and additional measurements may provide more reliable information. Fifth, the data was collected from a single center, limiting these results' generalizability. In the future, further investigations with large populations, multiple centers, and continuous monitoring are required to describe the prognostic role, diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of LAR with more precision.

6. Conclusion:

The mortality rate, ICU admission, and length of hospitalization were significantly increased in patients with higher LAR. LAR ≥ 136, with the sensitivity and specificity of 72% and 70%, was the optimal predictive threshold for COVID-19 mortality.

7.1. Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare for this study.

7.2. Funding

None.

7.4. Author contributions

Conceptualization: MD. Data curation: NA. Formal analysis: SA. Funding acquisition: None. Methodology: SA, NA, NF. Visualization: FT, NF, NA, AA. Writing—original draft: FT, AA. Writing—review, and editing: FT, AA, AM. All authors read and approved the final draft.

7.5. Data availability

Data of the study are available and will be provided if anyone needs them.

7.3. Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Coronavirus W. Dashboard| WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with vaccination data. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Team E. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020. China CDC Wkly. 2020;2(8):113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, Gui S, Liang B, Li L, et al. Time course of lung changes at chest CT during recovery from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Radiology. 2020;295(3):715–21. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uyeki TM, Bundesmann M, Alhazzani W. Clinical management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cascella M, Rajnik M, Aleem A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features, evaluation, and treatment of coronavirus (COVID-19). Statpearls. 2022. .available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554776. [PubMed]

- 6.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss P, Murdoch DR. Clinical course and mortality risk of severe COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1014–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30633-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. jama. 2020;323(13):1239–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parcha V, Kalra R, Bhatt SP, Berra L, Arora G, Arora P. Trends and Geographic Variation in Acute Respiratory Failure and ARDS Mortality in the United States. Chest. 2021;159(4):1460–72. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabello Filho R, Rocha LL, Corrêa TD, Pessoa CMS, Colombo G, Assuncao MSC. Blood lactate levels cutoff and mortality prediction in sepsis—time for a reappraisal? A retrospective cohort study. Shock (Augusta, Ga). 2016;46(5):480. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, Harrison DA, Sadique MZ, Grieve RD, et al. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1301–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ullah W, Basyal B, Tariq S, Almas T, Saeed R, Roomi S, et al. Lymphocyte-to-C-reactive protein ratio: a novel predictor of adverse outcomes in COVID-19. J Clin Med Res. 2020;12(7):415. doi: 10.14740/jocmr4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qu R, Ling Y, Zhang Yhz, Wei Ly, Chen X, Li Xm, et al. Platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio is associated with prognosis in patients with coronavirus disease‐19. J Med Virol. 2020;92(9):1533–41. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C-Y, Lee C-H, Liu C-Y, Wang J-H, Wang L-M, Perng R-P. Clinical features and outcomes of severe acute respiratory syndrome and predictive factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Chin Med Assoc. 2005;68(1):4–10. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alizadeh N, Tabatabaei FS, Borran M, Dianatkhah M, Azimi A, Forghani SN, et al. Evaluation of the Possible Effect of the Influenza Vaccine on the Severity, Mortality, and Length of Hospitalization among Unvaccinated COVID-19 Patients; An Observational, Cross-Sectional Study. J Pharm Care. 2022;10(1):11–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin J, Hwang SY, Jo IJ, Kim WY, Ryoo SM, Kang GH, et al. Prognostic value of the lactate/albumin ratio for predicting 28-day mortality in critically ill sepsis patients. Shock. 2018;50(5):545–50. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin M, Si L, Qin W, Li C, Zhang J, Yang H, et al. Predictive value of serum albumin level for the prognosis of severe sepsis without exogenous human albumin administration: a prospective cohort study. J Intensive Care Med. 2018;33(12):687–94. doi: 10.1177/0885066616685300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnau-Barrés I, Güerri-Fernández R, Luque S, Sorli L, Vázquez O, Miralles R. Serum albumin is a strong predictor of sepsis outcome in elderly patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38(4):743–6. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486–552. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Zhou X, Xu S, Huang H, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934–43. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Liu H, Wu Y, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–81. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu M, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Xu X, Ma T, Ni F, et al. Predictive value of lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio (LAR) in patients with coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 May;382(21):2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, Cao Y, Alwalid O, Gu J, et al. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):425–34. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, Yang Y, Fayad ZA, Zhang N, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020;295(3):200463. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henry BM, De Oliveira MHS, Benoit S, Plebani M, Lippi G. Hematologic, biochemical and immune biomarker abnormalities associated with severe illness and mortality in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(7):1021–8. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou H, Zhang B, Huang H, Luo Y, Wu S, Tang G, et al. Using IL-2R/lymphocytes for predicting the clinical progression of patients with COVID-19. Clin Exp Immunol. 2020;201(1):76–84. doi: 10.1111/cei.13450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun D-w, Zhang D, Tian R-h, Li Y, Wang Y-s, Cao J, et al. The underlying changes and predicting role of peripheral blood inflammatory cells in severe COVID-19 patients: A sentinel? Clin Chim Acta. 2020;508:122–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeon SY, Ryu S, Oh S-K, Park J-S, You Y-H, Jeong W-J, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio as a prognostic factor for patients with severe infection requiring intensive care. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(41):e27538. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000027538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee B-K, Ryu S, Oh S-K, Ahn H-J, Jeon S-Y, Jeong W-J, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio as a prognostic factor in lower respiratory tract infection patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;52:54–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]