Summary

Background

Covid-19 pandemic control has imposed several non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). Strict application of these measures has had a dramatic reduction on the epidemiology of several infectious diseases. As the pandemic is ongoing for more than 2 years, some of these measures have been removed, mitigated, or less well applied. The aim of this study is to investigate the trends of pediatric ambulatory infectious diseases before and up to two years after the onset of the pandemic.

Methods

We conducted a prospective surveillance study in France with 107 pediatricians specifically trained in pediatric infectious diseases. From January 2018 to April 2022, the electronic medical records of children with an infectious disease were automatically extracted. The annual number of infectious diseases in 2020 and 2021 was compared to 2018-2019 and their frequency was compared by logistic regression.

Findings

From 2018 to 2021, 185,368 infectious diseases were recorded. Compared to 2018 (n=47,116) and 2019 (n=51,667), the annual number of cases decreased in 2020 (n=35,432) by about a third. Frequency of scarlet fever, tonsillopharyngitis, enteroviral infections, bronchiolitis, and gastroenteritis decreased with OR varying from 0·6 (CI95% [0·5;0·7]) to 0·9 (CI95% [0·8;0·9]), p<0·001. In 2021, among the 52,153 infectious diagnoses, an off-season rebound was observed with increased frequency of enteroviral infections, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis and otitis with OR varying from 1·1 (CI95% [1·0;1·1]) to 1·5 (CI95% [1·4;1·5]), p<0·001.

Interpretation

While during NPIs strict application, the overall frequency of community-acquired infections was reduced, after relaxation of these measures, a rebound of some of them (enteroviral infections, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, otitis) occurred beyond the pre-pandemic level. These findings highlight the need for continuous surveillance of infectious diseases, especially insofar as future epidemics are largely unpredictable.

Funding

ACTIV, AFPA, GSK, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi.

Keywords: Ambulatory network, Covid-19 pandemic, Children, Immunity debt

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

A dramatic decrease of viral and bacterial disease was reported globally following non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) against the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in early 2020. This collateral effect raised questions about the long-term effect of the avoided infections, known as the immunity debt, particularly in children. We searched PubMed for articles published in English from March 1, 2020 to April 28, 2022, using the terms “immune debt”, “immunity debt”, “unusual outbreak”, and “off-season outbreak”. In 2021, when most of the NPIs were lifted, several countries reported unusual bronchiolitis outbreaks, with peaks exceeding those of the pre-pandemic period, related to respiratory syncytial virus. A similar outbreak was reported in France for hand, foot, and mouth disease in September 2021. More recently, the United Kingdom GAS infections surveillance network reported an unusual rise in scarlet fever and invasive GAS infections in early 2022.

Added value of this study

This prospective surveillance study in France with 107 ambulatory pediatricians assessed the epidemiology of multiple infectious disease in children between January 2018 and April 2022. We observed a major decrease of infectious disease in 2020. In addition to the unusual outbreaks of enteroviral infection and bronchiolitis in 2021, we observed similar trends for otitis and gastroenteritis. These outbreaks support the relevance of the concept of immunity debt.

Implications of all the available evidence

Although a rebound has yet to be observed for group A streptococcal diseases, chickenpox and pneumonia, immunity debt for other diseases raises concern about the risk of a larger number of future outbreaks. For influenza, we observed a major and unusual influenza outbreak in early 2022. The risks associated with this concept could be attenuated for vaccine preventable diseases by expanding the immunization schedule and better vaccine coverage. Over the upcoming years, new vaccines and other methods for preventing respiratory pathogens will be introduced (respiratory syncytial virus vaccines, new-generation pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, new influenza vaccines, new SARS-Cov-2 vaccines, etc.) and our surveillance system will enable us to rapidly assess the effectiveness of these interventions. The underlying mechanisms after NPIs implementation and their relaxation which led to different patterns for different pathogens need to be elucidated to better understand the epidemiology of infectious diseases. Continuous surveillance of infectious diseases remains needed, especially insofar as epidemics are largely unpredictable.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Following the implementation of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2, a dramatic effect was also reported on other viruses and bacterial species.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 In fact, the NPI measures strictly applied in many countries (containment, curfew, closure of schools and day care centers, distancing, masks, reinforced hand hygiene) considerably reduced almost all airborne and contact transmitted community-acquired infections.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Concerns have been raised about the lack of exposure to common infections and the possibility that prolonged periods of reduced contacts with pathogens may reduce protective immunity, mainly by reducing the adaptive immunity against many pathogens.7 Many of these infections, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rotavirus and enterovirus, occur in nearly all children during their first years of life. The diseases ensure acquisition of specific immunity, with variable duration and degrees of protection. Furthermore, for many bacterial species (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Neisseria meningitidis...), specific immunity is acquired through regular nasopharyngeal carriage. NPIs may have altered these mechanisms of acquisition of immunity against viruses and bacteria for a large number of children and may represent “collateral damage” raising fears of the occurrence of an immunity debt.8, 9, 10 Various studies have reported a marked increase in the incidence of different diseases in 2021, supporting the relevance of the concept of immunity debt for RSV and enterovirus.8,11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18

In 2017, we set up a nationwide pediatric ambulatory infectious disease surveillance network (PARI, Pediatric and Ambulatory Research in Infectious diseases) to assess trends of in pediatric infectious diseases before and after the implementation of nationwide health interventions.19 This study allowed us to observe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on infectious disease frequency, which sharply decreased in 2020.19 While the pandemic remained ongoing for 2 years, the burden of COVID-19 is now reduced, and NPIs have been gradually lifted, the aim of this study is to investigate the trends of pediatric ambulatory infectious diseases before and up to two years after the onset of the pandemic.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a prospective multicentric surveillance study in France. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline was observed.

Study data and settings

The surveillance network was based on automated and contemporaneous extraction from electronic medical records between January 2018 and April 2022. Diagnostics were recorded by each physician using the International Classification of Disease 10th edition. The surveillance system was co-created by the Association Française de Pédiatrie Ambulatoire (AFPA) and the Association Clinique Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne (ACTIV) research group. As previously published,19 107 pediatricians specifically trained in pediatric infectious diseases using the same software, AxiSanté 5 - Infansoft (CompuGroup Medical, France) participated in the surveillance network in ambulatory setting. As investigators, they attended meetings, training courses, and an annual congress dedicated to ambulatory pediatric infectious diseases. To improve their diagnostic performance, a dedicated website was created (https://www.activ-france.com/fr/accueil-e-learning). In addition, the pediatrician participants had real-time access to the epidemiology of several infectious diseases on a dedicated website. The following data on all children under 16 years of age were collected: demographic data, point-of-care tests, and antibiotic consumption. The following infectious disease diagnoses for all children under 16 years of age triggered automatic data extraction: acute otitis media (AOM)/otorrhea, COVID-19, Group A Streptococcal (GAS) infections (tonsillopharyngitis, scarlet fever, perineal infections, paronychia with a positive rapid diagnostic test), pneumonia, influenza/influenza syndromes, bronchiolitis, pertussis, urinary tract infections/pyelonephritis/cystitis, gastroenteritis, enteroviral infections (hand/foot/mouth diseases, herpangina etc.), and, chicken pox/shingles. Suspected COVID-19 not confirmed by test, pertussis, mononucleosis, otitis externa, perianal streptococcal dermatitis, paronychia were grouped as “other”. International Classification of Diseases codes are detailed in Supplemental Table 1. A quality control and an external validation were set up to ensure high quality of data generated by this system.

Point-of-care tests

Point-of-care tests such as combo tests (SARS-CoV-2, RSV, and influenza) were distributed free of charge to participating pediatricians. The use of point-of-care tests was not mandatory nor systematic and pediatricians decided whether to perform point of care test or not according to their diagnosis hypothesis and the clinical status of the patient. Rapid diagnostic tests to detect GAS were provided free of charge by the French National Health Service and were recommended in all children ≥ 3 years old with tonsillopharyngitis and pharyngitis to guide antibiotic treatment.20 We included all diagnoses of scarlet fever regardless of the result of the GAS rapid diagnostic test.

Nationwide interventions in France

Between 17 March and 11 May 2020, a stringent lockdown was imposed in view of reducing the spread of COVID-19. Between 30 October and 14 December 2020, and between 3 April and 2 May 2021, two less strict lockdowns were instituted. It is worthy to note that government decided to limit school closure. In France, the total duration of full and partial school closure was 12 weeks compared to 27 in United Kingdom, 51 in Canada, and 58 in the United States.21 Details on the NPIs implemented in France (mandatory face mask, school closure…) have been provided by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.22

Vaccination over the study period

Vaccination coverage remained high in France throughout the study period. More specifically, 91·2% of children born in 2020 received the recommended 3 doses of pneumococcal conjugated vaccine versus 91·1% for children born in 2018.23 Because there are no recommendations for children, there are no data on pediatric vaccination coverage for influenza vaccine, which was higher for adults in 2021-2022 compared to 2019-2020, or chickenpox.23

Statistics

STATA 15 (StataCorp 2015, College Station, TX) was used for data management and statistical analysis. To evaluate the diagnostic methods, clinical characteristics, treatments and evolution of the pathologies, we computed frequencies and percentages for infectious disease diagnoses from 2018 to 2021. To quantify the increase or decrease in each infectious disease in 2020 and 2021, we used a logistic regression model, with 2018 and 2019 grouped as baseline. As a denominator, we used the overall infectious diseases reported by the network. For enteroviral infection, bronchiolitis, otitis, gastroenteritis, and chickenpox, we compared ages between 2021 and the 2018-2019 period by using Student test.

Ethics

Parents and children were informed of the study by a poster in the waiting room and with a leaflet in the pediatrician office. In accordance with the French law, no written form was required. All data were analyzed unless parents expressed their refusal to the pediatrician. During the study period, no parent expressed their refusal. The study was approved by the French National Commission on Informatics and Liberty (no. 1921226) and by an ethics committee (CHI Créteil Hospital, France) and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04471493).

Role of funding source

The study was supported by Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val de Marne (ACTIV), French Pediatrician Ambulatory Association (AFPA) and unrestricted grants of GSK, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi. The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

From 2018 to 2021, 185,368 diagnoses of infectious diseases in 117,431 children were recorded (male 71,404, 59·3%). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the patients included in the study and the distribution of infectious diseases. Compared to 2018-2019, the annual number of infectious diseases reported by the network in 2020 decreased by about a third. As shown in Table 2, almost all the diseases monitored, except for influenza and UTI, were impacted by this decrease (OR from 0·6 to 0·9, p<0·001). By contrast, compared to 2018-2019, the annual number of infectious diseases reported by the network in 2021 increased by 5%. Frequency of otitis, gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis and enterovirus infections increased significantly (OR from 1·1 to 1·5, p<0·001), whereas frequency of overall or GAS tonsillopharyngitis, scarlet fever, influenza, chickenpox and pneumonia decreased significantly (OR from 0·2 to 0·7, p<0·001). Frequency of urinary tract infections remained stable in 2021.

Table 1.

Characteristics and distribution, of children with an infectious disease diagnosis.

| Study years |

Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| Overall visits to ambulatory pediatricians, n | 600,824 | 601,000 | 736,291 | 852,530 | 2,790,645 |

| Children with an infectious disease diagnosis, n | 29,673 | 32,721 | 25,138 | 32,899 | 120,431 |

| Male, n (%) | 17,137 (57·7) | 19,218 (58·7) | 15,044 (59·9) | 20,005 (60·8) | 71,404 (59·3) |

| Antibiotic prescription, n | 18,236 | 20,051 | 13,471 | 20,097 | 71,855 |

| Age in months, median (IQR)a | 24 (12-46) | 25 (12-48) | 25 (12-50) | 22 (12-41) | 24 (12-46) |

| Visit with a diagnosis of monitored infectious diseases, n | 47,116 | 51,667 | 35,432 | 52,153 | 186,368 |

| Otitis, n (%) | 17,585 (37·3) | 18,720 (36·2) | 13,076 (36·9) | 19,831 (38·0) | 69,212 (37·1) |

| Non-GAS tonsillopharyngitis and pharyngitis, n (%) | 8,340 (13·4) | 8,648 (12·1) | 5,731 (13·2) | 6,592 (11·2) | 29,311 (12·4) |

| GAS tonsillopharyngitis and pharyngitis, n (%) | 2026 (4·3) | 2372 (4·6) | 1048 (3·0) | 729 (1·4) | 6175 (3·3) |

| Scarlet fever, n (%) | 620 (1·3) | 671 (1·3) | 281 (0·8) | 147 (0·3) | 1,719 (0·9) |

| Gastroenteritis, n (%) | 5061 (10·7) | 5675 (11·0) | 3341 (9·4) | 6057 (11·6) | 20,134 (10·8) |

| Bronchiolitis, n (%) | 4020 (8·5) | 4295 (8·3) | 2191 (6·2) | 5702 (10·9) | 16,208 (8·7) |

| Enteroviral infections, n (%) | 3918 (8·3) | 3626 (7·0) | 1865 (5·3) | 5620 (10·8) | 15,029 (8·1) |

| Influenza-like illness, n (%) | 3005 (6·4) | 4715 (9·1) | 4475 (12·6) | 1299 (2·5) | 13,494 (7·2) |

| Chickenpox, n (%) | 2934 (6·2) | 3657 (7·1) | 1809 (5·1) | 2992 (5·7) | 11,392 (6·1) |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 566 (1·2) | 535 (1.0) | 233 (0·7) | 416 (0·8) | 1750 (0·9) |

| COVID-19, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 288 (0·8) | 771 (1·5) | 1059 (0·6) |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 248 (0·5) | 222 (0·4) | 277 (0·8) | 239 (0·5) | 986 (0·5) |

| Other, n (%) | 819 (1·7) | 903 (1·7) | 1865 (5·3) | 2487 (4·8) | 6074 (3·3) |

Children can be counted several times as they can have multiple visits with a diagnosis of infectious disease.

Abbreviations: GAS, group A Streptococcal.

Table 2.

Frequencies and percentages of infectious disease in 2020 and 2021 compared to the 2018-2019 period.

| 2018-2019 period N=98,783 |

2020 N=35,432 |

2021 N=52,153 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR | n (%) | OR [95% CI] | P-value | n (%) | OR [95% CI] | P-Value | |

| Otitis | 36,305 (36·7) | 1 | 13,076 (36,9) | 1 [1·0;1·0] | 0·61 | 19,831 (38·0) | 1·1 [1·0;1·1] | <0·001 |

| Overall tonsillopharyngitis and pharyngitis | 16,988 (17·2) | 1 | 5731 (16·2) | 0·9 [0·9;1·0] | <0·001 | 6592 (12·6) | 0·7 [0·7;0·7] | <0·001 |

| GAS tonsillopharyngitis and pharyngitis | 4,398 (24·0) | 1 | 1048 (17·4) | 0·7 [0·6;0·7] | <0·001 | 729 (10·8) | 0·4 [0·4;0·4] | <0·001 |

| Scarlet fever | 1291 (1·3) | 1 | 281 (0·8) | 0·6 [0·5;0·7] | <0·001 | 147 (0·3) | 0·2 [0·2;0·3] | <0·001 |

| Gastroenteritis | 10,736 (10·9) | 1 | 3,341 (9·4) | 0·9 [0·8;0·9] | <0·001 | 6057 (11·6) | 1·1 [1·0;1·1] | <0·001 |

| Bronchiolitis | 8315 (8·4) | 1 | 2191 (6·2) | 0·7 [0·7;0·8] | <0·001 | 5702 (10·9) | 1·3 [1·3;1·4] | <0·001 |

| Enteroviral infections | 7544 (7·6) | 1 | 1865 (5·3) | 0·7 [0·6;0·7] | <0·001 | 5620 (10·8) | 1·5 [1·4;1·5] | <0·001 |

| Influenza-like illness | 7720 (7·8) | 1 | 4475 (12·6) | 1·7 [1·6;1·8] | <0·001 | 1299 (2·5) | 0·3 [0·3;0·3] | <0·001 |

| Chickenpox | 6591 (6·7) | 1 | 1809 (5·1) | 0·8 [0·7;0·8] | <0·001 | 2992 (5·7) | 0·9 [0·8;0·9] | <0·001 |

| Pneumonia | 1101 (1·1) | 1 | 233 (0·7) | 0·6 [0·5;0·7] | <0·001 | 416 (0·8) | 0·7 [0·6;0·8] | <0·001 |

| Urinary tract infection | 470 (0·5) | 1 | 277 (0·8) | 1·6 [1·4;1·9] | <0·001 | 239 (0·5) | 1 [0·8;1·1] | 0·64 |

Significant p-Values (<0·05) are shown in bold. COVID-19; other infectious disease diagnoses are not included in the Table.

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval ; GAS, group A Streptococcal.

For each disease, the dependent variable is dichotomic : disease/no disease. The OR calculations are based on the comparison of each year (2020 and 2021) to the reference (2018-2019).

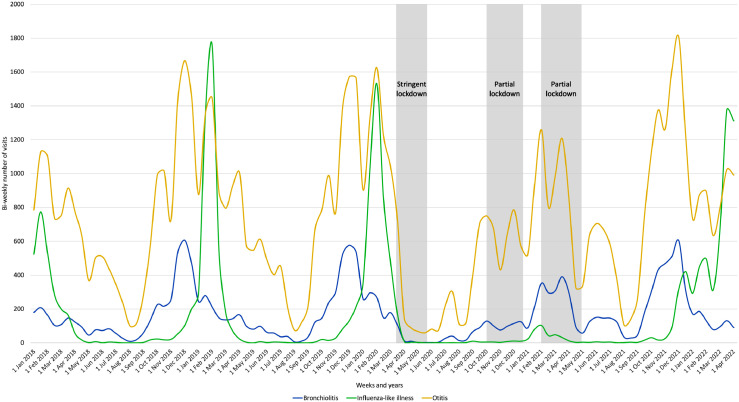

Figure 1 presents, between January 2018 and April 2022, the bi-weekly number of the syndromes or diseases for which a significant rebound of infections was observed in 2021: enteroviral infections, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, and otitis. In 2021, seasonality for otitis was unchanged, while an uncommon large-scale outbreak was observed for enteroviral infections. It was characterized by a sharp rise in the summer and an autumn peak occurring earlier than in previous years. Similarly, for bronchiolitis and gastroenteritis, uncommon trends were observed in 2021 with numerous cases reported during the summer and the beginning of the fall.

Figure 1.

Bi-weekly number of enteroviral infections, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, and otitis between January 2018 and April 2022 in children included in the Pediatric and Ambulatory Research in Infectious surveillance network.

The lockdowns during the study period are shown in purple for 2020 and in yellow for 2021.

Figure 2 presents the bi-weekly number of syndromes or diseases for which a reduction was observed in both 2020 and 2021: overall and GAS tonsillopharyngitis, scarlet fever, influenza, chickenpox, and pneumonia. In early 2022, an increase was observed for influenza and chickenpox compared to the 2018-2019 period.

Figure 2.

Bi-weekly number of overall cases of tonsillopharyngitis and pharyngitis, group A Streptococcal (GAS) tonsillopharyngitis and pharyngitis, scarlet fever, influenza-like illness, chickenpox, and pneumonia between January 2018 and April 2022 in children included in the Pediatric and Ambulatory Research in Infectious surveillance network.

The lockdowns during the study period are shown in purple for 2020 and in yellow for 2021.

Figure 3 shows the monthly number of otitis, bronchiolitis and influenza over the study period. Between 2018 and 2019, peaks in otitis were observed simultaneously with bronchiolitis and influenza peaks and the bronchiolitis outbreak, which was closely followed by the influenza outbreak. A near-absence of influenza was observed between April 2020 and November 2021 until a resurgence occurred in early 2022. In late 2020 and in 2021, several otitis peaks were likewise observed.

Figure 3.

Monthly number of bronchiolitis, influenza-like illness and otitis cases between January 2018 and April 2022 in children included in the Pediatric and Ambulatory Research in Infectious surveillance network.

For enteroviral infections, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, otitis and chickenpox, a peak was observed at around 12 months. For chickenpox, particularly in 2021, a plateau was observed between 1 and 4 years of age (Supplemental Figure). No significant change in the age distribution between 2018-2019 and 2021 was observed for enteroviral infections (Supplemental Table 2). Children with bronchiolitis, otitis, and gastroenteritis were slightly younger in 2021 than during the 2018-2019 period, while an opposed trend was observed for chickenpox.

Discussion

In the best of our knowledge, this study is the only one that has specifically investigated the trends of numerous pediatric ambulatory infectious diseases before and up to two years after the onset of the pandemic. During the COVID-19 pandemic period in 2020, when NPIs were particularly stringent, infectious diseases decreased by about a third, as did all the other diseases reported in the PARI study, except for urinary tract infection, influenza and otitis. In 2021, when NPIs were progressively lifted, while the frequency of some diseases remained low or at baseline level (influenza, pneumonia, tonsillopharyngitis, chickenpox), significant increases were observed for other diseases.

Compared to the pre-pandemic period, the 2021 increase of enteroviral infections, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis and otitis highlights the interest of the concept of immunity debt. Several studies, particularly in Australia and New Zealand, have reported significantly increased incidence of bronchiolitis following the end of strict NPIs.5,11,18 It bears mentioning that if the increase in France was likewise significant, the shape of the curves is very different, probably because the hygiene measures proposed, their duration and their discontinuation were very different.17 In Australia and New Zealand, the epidemic curves were sharp, whereas in France, the epidemic was spread over a long period and presented several peaks during which emergency service pediatric wards were overloaded.

For enteroviral infections, the association between the laboratory of the National Reference Centre for enteroviruses and the PARI network reported a large-scale outbreak of hand, foot and mouth disease and herpangina in 2021.16 In a subgroup of children, clinical diagnoses by pediatricians of the PARI network were confirmed by PCR in 90·5% of cases, attesting to the accuracy of clinical diagnosis.16 The increase of gastroenteritis cases in France in comparison with other countries is probably associated with the fact that vaccination against rotavirus was not recommended in France and immunity debt could not thusly be attenuated by vaccine program.9

The high proportion of children with influenza in 2020 may be explained by the occurrence of outbreak before the first lockdown. In 2021, a quasi-absence of visits for influenza was observed. By contrast, the 2020-2021 bronchiolitis outbreak was shifted in time. RSV and influenza have lower basic reproductive numbers than SARS-CoV-2 particularly for the emerging variants24,25 which makes NPIs targeting SARS-CoV-2 particularly effective against these pathogens. However, the effective R0 of these different agents could be different according to the type of virus, the circulating strain, but also other various factors such as the immunity status of the population which may explained the different patterns.25 In the first four months of 2022, the high number of influenza cases and the seasonality in France were unusual and support also the immunity debt concept. The progressive lifting of NPIs, particularly the March 2022 abrogation or rules instituting of mandatory masks for children > 6 years old, may partially explain this delayed outbreak. Furthermore, influenza vaccine is not recommended for children with no underlying condition in France.

In addition to the 2021 increase of some epidemics, they no longer have the same profiles: shifted seasonality, longer duration, rebound, etc. This may complexify organization of the pediatric care system or, more specifically, the dates of administration of palivizumab for children at risk. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, predictable annual seasonality of enteroviral infections, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, and influenza was observed, whereas our study highlights pronounced changes in 2021, with uncommon outbreaks. A higher disease burden and the shift in the seasonality underline the relevance of immune debt concept. All in all, these findings complicate predictions of health care system stress.8, 9, 10,18

Our results show that after the lifting of NPIs, some infectious diseases increased while others remained at low levels. However, this does not rule out the possibility that over a longer period, number of infections will rebound. Otitis is case in point. It has been known for a long time that this disease often results from the intermingling of viral and bacterial infections.26 Figure 3 shows that every year, even when the strictest NPI measures were applied, ear infection peaks were always contemporaneous with those of bronchiolitis and influenza. Recent studies suggest that the decline in pneumococcal infections during the pandemic was due mainly to the reduced circulation of viral infections (RSV, influenza, and human metapneumovirus).27 On the contrary, in 2021 and 2022 GAS tonsillopharyngitis did not return to the level of the pre-pandemic years. Interestingly, whereas a significant decrease of GAS tonsillopharyngitis and scarlet fever was observed in 2020 compared to 2018-2019, different patterns were reported in 2021 with OR of respectively 0.4 (95% confidence interval [0·4;0·4] and 0.2 [0·2;0·3]. By contrast to GAS tonsillopharyngitis, scarlet fever implicates an infection with Streptococcus pyogenes strains producing pyrogenic exotoxins.28 The differences in the dynamic of these specific strains and their seasonality could explain the patterns observed in 2021 in our study.29 The United Kingdom GAS infections surveillance network reported an unusual rise in scarlet fever and invasive GAS infections in early 2022, which nonetheless remained below average compared to the pre-pandemic period.30 It is unclear how GAS infection will evolve particularly GAS tonsillopharyngitis compared to scarlet fever. It is possible that prolonged NPIs may have affected the reservoir of GAS, thus explaining the delay to reach the previous annual frequency of the GAS pharyngitis or scarlet fever.31 Furthermore, for pneumococcus and meningococcus, viral infections play an important role in the occurrence of disease.27,32 The resurgence of RSV and influenza outbreak may explain the increase in the frequency of infections due to these bacterial species. To our knowledge, the role of viral infections in promoting streptococcal infections is less documented.

Although, we have observed significant differences in ages for several diseases, these findings may not be relevant for a clinician point of view. Indeed, the higher difference between 2018-2019 and 2021 was found 2.0 months for chickenpox.

Our study has several limitations. Our clinical and syndromic surveillance was not always associated with bacteriological and/or virological investigations. However, for enteroviral infections placed under virological surveillance, we reported very good correlations, and for several syndromes (tonsillopharyngitis, influenza, bronchiolitis) rapid diagnosis tests were frequently performed.16 Moreover, influenza-like illness is often used as proxies to monitor influenza epidemiology.33,34 Similarly, bronchiolitis can be used as proxy for RSV.34 Furthermore, we did not assay the antibodies counteracting the pathogens involved in community-acquired infections. We cannot rule out the possibility that the early 2020 decrease was partially due to parents’ fear of going out or seeking medical attention. However, the increase of visits in 2020 and the absence of decrease of urinary tract infection on which NPIs are not expected to have an impact are against this hypothesis. Finally, our study was limited to ambulatory diseases. That said, the study of invasive bacterial infection could corroborate the immunity debt theory. For example, the United Kingdom security agency reported a rise in invasive meningococcal disease in autumn 2021 following the withdrawal of containment measures.35 This increase was due to serogroup B, and exceeded pre-pandemic levels.

Conclusions

After the lifting of most NPIs, increased occurrence of several infectious diseases, a change of seasonality for many, and a shift in age for some combine to underline the interest of the immunity debt concept. Our findings also underline the need to achieve better coverage for recommended vaccines, to expand the immunization programs for other vaccines and to ensure continuous surveillance of infectious diseases, especially insofar as epidemics are largely unpredictable.

Contributors

Pr Cohen, Dr Rybak, Dr Levy and Mr Béchet had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Cohen, Levy.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Cohen, Rybak, Werner, Béchet, Desandes, Hassid, André, Gelbert, Thiebault, Kochert, Cahn-Sellem, Vié Le Sage, Angoulvant, Ouldali, Frandji, and Levy.

Drafting of the manuscript: Cohen, Rybak, Béchet, Levy.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Werner, Desandes, Hassid, André, Gelbert, Thiebault, Kochert, Cahn-Sellem, Vié Le Sage, Angoulvant, Ouldali, and Fandji.

Statistical analysis: Cohen, Rybak, Béchet, Levy.

Obtained funding: Levy, Cohen.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Levy, Béchet.

Supervision: Cohen, Rybak, Levy.

Data sharing statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of interests

RC reports grants to the institution ACTIV, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from GSK, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Merck, outside the submitted work. AR reports travel grants from Pfizer and AstraZeneca. FA reports receiving personal fees from MSD, AstraZeneca, Sanofi and Pfizer.NO reports travel grants from Pfizer, Sanofi, and GSK, outside the submitted work. BF is employed by CompuGroup Medical. CL reports grants to the institution ACTIV from GSK, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Merck, and personal fees and nonfinancial support from Pfizer and Merck, outside the conduct of the study. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the investigators of the PARI study Network: Drs Akou'Ou Marie-Hélène, Auvrignon Anne, Bakhache Pierre, Barrois Sophie, Batard Christophe, Beaufils-Philippe Florence, Bellemin Karine, Berquier Juliette, Bled Jérémie, Boulanger Sophie, Cambier Nappo Eliane, Chartier Albrech Chantal, Cheve Anne, Cornic Muriel, Coudy Caroline, Courtot Hélène, Delavie Nadège, Delobbe Jean-François, Desvignes Véronique, Elbez Annie, Gelbert Nathalie, Gorde-Grosjean Stéphanie, Goulamhoussen Salim, Guiheneuf Cécile, Hassid Frédéric, Hennequin Stéphanie, Jouty Cécile, Kampf Maupu Flaviane, Kherbaoui Louisa, Langlais Sophie, Legras Cécilia, Lemarie Dominique, Lubelski Patricia, Minette Delphine, Moore Wipf Solange, Pruvost Dussart Isabelle, Ravilly Sophie, Salaun Jean-François, Salomez Sophie, Sangenis Marta Inès, Savajols Elodie, Seror Elisa, Starynkevitch Anne, Thollot Franck, Vigreux Jean-Christophe, Werner Andréas, Wollner Alain, Zouari Morched.

We are grateful to the ACTIV team: Ramay Isabelle, Prieur Aurore, Borg Marine.

We thank Arsham Jeffrey for language editing.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100497.

Contributor Information

Pr Robert Cohen, Email: robert.cohen@activ-france.fr.

Corinne Levy, Email: corinne.levy@activ-france.fr.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Baker RE, Park SW, Yang W, Vecchi GA, Metcalf CJE, Grenfell BT. The impact of COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on the future dynamics of endemic infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(48):30547–30553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2013182117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belingheri M, Paladino ME, Piacenti S, Riva MA. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on epidemic diseases of childhood. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):153–154. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brueggemann AB, Jansen van Rensburg MJ, Shaw D, et al. Changes in the incidence of invasive disease due to streptococcus pneumoniae, haemophilus influenzae, and neisseria meningitidis during the COVID-19 pandemic in 26 countries and territories in the invasive respiratory infection surveillance initiative: a prospective analysis of surveillance data. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(6):e360–e370. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00077-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taha MK, Deghmane AE. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown on invasive meningococcal disease. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):399. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-05241-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeoh DK, Foley DA, Minney-Smith CA, et al. The impact of COVID-19 public health measures on detections of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in children during the 2020 Australian winter. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(12):2199–2202. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaur R, Schulz S, Fuji N, Pichichero M. COVID-19 pandemic impact on respiratory infectious diseases in primary care practice in children. Front Pediatr. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.722483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pettoello-Mantovani M, Cardemil C, Cohen R, et al. Importance of coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in children: viewpoint and recommendations of the union of european national societies of pediatrics. J Pediatr. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.12.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatter L, Eathorne A, Hills T, Bruce P, Beasley R. Respiratory syncytial virus: paying the immunity debt with interest. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(12):e44–e45. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00333-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen R, Pettoello-Mantovani M, Somekh E, Levy C. European pediatric societies call for an implementation of regular vaccinationprograms to contrast the immunity debt associated to coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic in children. J Pediatr. 2022;242:260–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.11.061. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen R, Ashman M, Taha MK, et al. Pediatric Infectious Disease Group (GPIP) position paper on the immune debt of the COVID-19 pandemic in childhood, how can we fill the immunity gap? Infect Dis Now. 2021;51(5):418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foley DA, Yeoh DK, Minney-Smith CA, et al. The interseasonal resurgence of respiratory syncytial virus in australian children following the reduction of coronavirus disease 2019-related public health measures. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han S, Zhang T, Lyu Y, et al. The incoming influenza season - China, the United Kingdom, and the United States, 2021-2022. China CDC Wkly. 2021;3(49):1039–1045. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2021.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang YB, Lin YR, Hung SK, Chang YC, Ng CJ, Chen SY. Pediatric training crisis of emergency medicine residency during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children (Basel) 2022;9(1) doi: 10.3390/children9010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattana G, Albitar-Nehme S, Cento V, et al. Back to the future (of common respiratory viruses) J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2022;28:223–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2022.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Methi F, Stordal K, Telle K, Larsen VB, Magnusson K. Hospital admissions for respiratory tract infections in children aged 0-5 years for 2017/2023. Front Pediatr. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.822985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirand A, Cohen R, Bisseux M, et al. A large-scale outbreak of hand, foot and mouth disease, France, as at 28 September 2021. Euro Surveill. 2021;26(43) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.43.2100978. PMID: 34713796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rybak A, Levy C, Jung C, et al. Delayed bronchiolitis epidemic in french primary care setting driven by respiratory syncytial virus: preliminary data from the Oursyn Study, March 2021. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021 doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor A, Whittaker E. The changing epidemiology of respiratory viruses in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a canary in a COVID time. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41(2):e46–e48. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen R, Bechet S, Gelbert N, et al. New approach to the surveillance of pediatric infectious diseases from ambulatory pediatricians in the digital era. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40(7):674–680. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen R, Haas H, Lorrot M, et al. Antimicrobial treatment of ENT infections. Arch Pediatr. 2017;24(12S):S9–S16. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(17)30512-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNESCO. Global monitoring of school closure due to COVID-19. 2021. https://covid19.uis.unesco.org/gpe-map/. Accessed 12 July 2022.

- 22.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Data on country response measures to COVID-19. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/download-data-response-measures-covid-19. Accessed 2 November 2021.

- 23.Santé Publique France. Bulletin de santé publique vaccination - Avril 2022. 2022. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/content/download/429709/3439305. Accessed 28 April 2022.

- 24.Petersen E, Koopmans M, Go U, et al. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 with SARS-CoV and influenza pandemics. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(9):e238–e244. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30484-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otomaru H, Kamigaki T, Tamaki R, et al. Transmission of respiratory syncytial virus among children under 5 years in households of rural communities, the Philippines. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(3):ofz045. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wald ER. Acute otitis media and acute bacterial sinusitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl 4):S277–S283. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danino D, Ben-Shimol S, Van Der Beek BA, et al. Decline in pneumococcal disease in young children during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel associated with suppression of seasonal respiratory viruses, despite persistent pneumococcal carriage: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab1014. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wessels MR. In: Streptococcus Pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations. Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA, editors. 2016. Pharyngitis and scarlet fever. Oklahoma City (OK) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamagni T, Guy R, Chand M, et al. Resurgence of scarlet fever in England, 2014-16: a population-based surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(2):180–187. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30693-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.UK Health Security Agency. Group A streptococcal infections: report on seasonal activity in England, 2021 to 2022. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/group-a-streptococcal-infections-activity-during-the-2021-to-2022-season/group-a-streptococcal-infections-report-on-seasonal-activity-in-england-2021-to-2022. Accessed 22 April 2022.

- 31.Kronfeld-Schor N, Stevenson TJ, Nickbakhsh S, et al. Drivers of infectious disease seasonality: potential implications for COVID-19. J Biol Rhythms. 2021;36(1):35–54. doi: 10.1177/0748730420987322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rybak A, Levy C, Angoulvant F, et al. Association of nonpharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic with invasive pneumococcal disease, pneumococcal carriage, and respiratory viral infections among children in France. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.18959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fowlkes A, Dasgupta S, Chao E, et al. Estimating influenza incidence and rates of influenza-like illness in the outpatient setting. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(5):694–700. doi: 10.1111/irv.12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schindeler SK, Muscatello DJ, Ferson MJ, Rogers KD, Grant P, Churches T. Evaluation of alternative respiratory syndromes for specific syndromic surveillance of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus: a time series analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:190. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.UK Health Security Agency. Recent increase in group B meningococcal disease among teenagers and young adults. 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/recent-increase-in-group-b-meningococcal-disease-among-teenagers-and-young-adults. Accessed 26 April 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.