Abstract

Purpose:

Gender minority (GM) (people whose gender does not align with the sex assigned at birth) people have historically been insured at lower rates than the general population. The purpose of this review is to (1) assess the prevalence of health insurance among GM adults in the United States, (2) examine prevalence by gender, and (3) examine trends in prevalence before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act.

Methods:

Published articles from PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases before April 26th, 2019, were included. This review is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42019133627). Analysis was guided by a random-effects model to obtain a meta-prevalence estimate for all GM people and stratified by gender subgroup. Heterogeneity was assessed using a Q-test and I2 measure.

Results:

Of 55 included articles, a random pooled estimate showed that 75% GM people were insured (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.71–0.79; p<0.001). Subgroup analysis by gender determined 70% of transgender women (95% CI: 0.64–0.76; p<0.001; I2=97.16%) and 80% of transgender men (95% CI: 0.77–0.83; p=0.01; I2=54.51%) were insured. Too few studies provided health insurance prevalence data for gender-expansive participants (GM people who do not identify as solely man or woman) to conduct analysis.

Conclusion:

The pooled prevalence of health insurance among GM people found in this review is considerably lower than the general population. Standardized collection of gender across research and health care will improve identification of vulnerable individuals who experience this barrier to preventative and acute care services.

Keywords: delivery of health care, health, health disparities, insurance, sexual and gender minorities

Introduction

The United States, general public predominantly relies upon health insurance to pay the majority of costs associated with health care services.1 However, access to health insurance varies based on social positioning (e.g., income, race/ethnicity, gender).2 In 2018, 91.2% of adults in the United States 18–64 years of age were insured.3 Unfortunately, these estimates do not capture the prevalence of health insurance among gender minority (GM) people (people whose gender identity is not aligned with the sex that was assigned at birth) due to the lack of comprehensive gender identity assessment in national population surveys.4 GM people are known to have significant health disparities when compared to the general population and rely upon health insurance and health care access in a unique way when compared to cisgender (individuals whose gender is aligned with the sex that was assigned at birth) peers.5 In addition to the treatment of acute illnesses or chronic conditions, GM people often rely on the health care system to access life-saving gender-affirming interventions to reduce the discomfort or emotional distress one may experience related to the misalignment of one's gender and the sex that they were assigned at birth.6 Without an estimate of health insurance prevalence among GM people, ambiguity persists in efforts to understand the role health insurance plays in health care access for GM people.

Many gender-affirming interventions focus on the alleviation of gender dysphoria.6 However, the decision to undertake gender-affirming intervention varies by the individual. In a national study of GM people (N=27,715), 78% of respondents wanted hormone therapy, but only 49% received it and only 25% of respondents had received gender-affirming surgeries (e.g., facial feminization and chest surgery).7 Adequate health insurance can be vital to managing hormone therapy for GM people.8

GM people who do not have health insurance are more likely to obtain hormones from sources other than licensed health care providers, increasing risk for harm.9 For example, hormone misuse has been associated with increased risk of venous thromboembolism10 and elevated liver enzymes.11 Furthermore, injectable hormone use outside of medical supervision has been associated with increased risk of contracting HIV.12

Lack of health insurance can also affect one's overall health.13 Higher financial strain related to lack of insurance is associated with delays in health care-seeking, thereby reducing access to preventative care and treatment for chronic illness.14,15 For example, health insurance coverage has been associated with improved outcomes for hypertension and as high as a 25% reduction in associated mortality.16,17 The Affordable Care Act (ACA), a legislative action to improve health care and access to health insurance coverage, was passed in 2010 with language that prohibited discrimination against GM people.18 However, questions remain regarding the effectiveness of this legislative action for health insurance access among GM people.

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to (1) assess the prevalence of health insurance among GM adults in the United States, (2) examine prevalence based on gender subgroup (i.e., transgender men, transgender women, and gender expansive), and (3) examine the prevalence of insured GM people before and following the expansion of the ACA in 2014.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was not required for this systematic review since there were no original data or participant data collected. This systematic review was organized using the 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)19 statement guidelines and was registered with Prospero, the international register of systematic reviews (Registration No. CRD42019133627).20 Articles were required to have (1) been published in the English language, (2) U.S.-based samples, (3) sampled GM adults, (4) reported prevalence of insured or uninsured GM adults, and (5) been peer reviewed (criterion added after protocol registration). Articles could not be (1) literature reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, (2) duplicated data sets, (3) military or incarcerated samples (because these systems provide inclusive internal health insurance/health care provision different from the general public), and (4) data solely from insurance databases.

Studies published before April 26th, 2019, were identified from PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases. Search terms included “transgender” and synonyms, “healthcare,” or “insurance” (Supplementary Table S1). One reviewer performed the entirety of the search and compiled the search results (N=13,518). A hand search was conducted to identify potential articles for inclusion using the references within the studies included during the full text review. This resulted in the screening of nine additional articles.

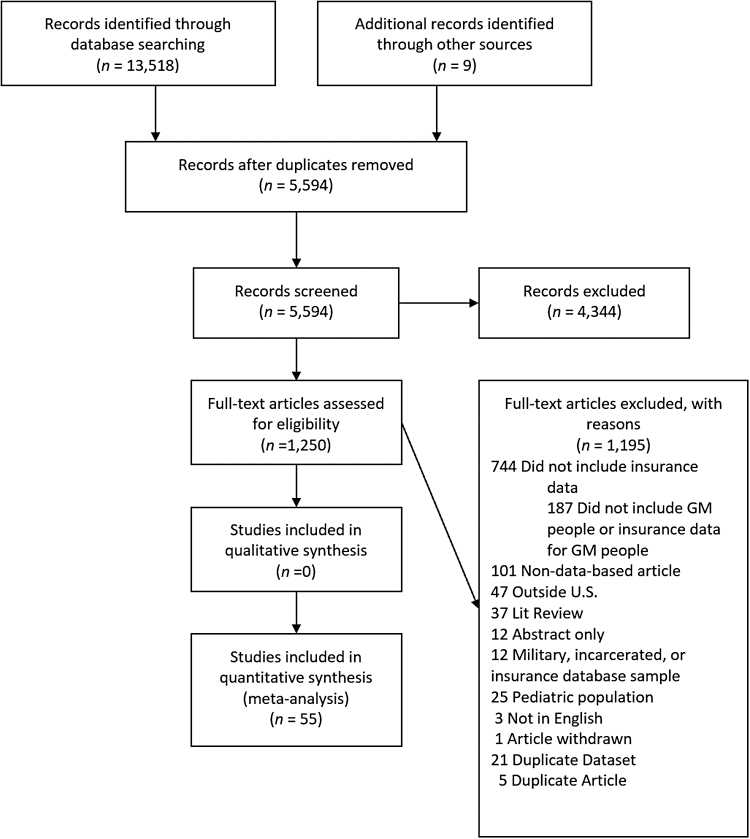

Covidence, a web-based application, was used to compile the sourced studies and eliminate duplicates.21 Two reviewers conducted title and abstract screening based on inclusion and exclusion criteria (PRISMA flow diagram; Fig. 1).19 The remaining articles (N=1,250) underwent full text review by two reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved through reviewer discussion. The articles that remained (N=55) were entered in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for data extraction.

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the searching and screening process. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Data extraction was completed by two reviewers for quality assurance. Both reviewers processed each article identifying data points for extraction and placed relevant data into an Excel spreadsheet. Items extracted include the following: (1) study characteristics (e.g., location, year that sample was recruited [used to identify pre- and post-2013 ACA antidiscrimination implementation], and sampling method), (2) sample characteristics (i.e., race/ethnicity and gender identity category), and (3) insurance status (i.e., prevalence and type). Gender identity data were categorized into transgender men (e.g., men who were assigned-female-at-birth, female-to-male transgender, transmasculine, and transgender men), transgender women (e.g., women who were assigned-male-at-birth, transfeminine, and transgender women), and gender expansive (e.g., genderqueer and gender nonconforming). Race/ethnicity was grouped as Black, Hispanic/Latinx, White, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, and another.

Health insurance prevalence was extracted as the reported number of insured (n). Where the articles reported a percentage of insured within the sample, this number was calculated based on the total sample. Fifteen authors were contacted to obtain insurance prevalence among individual gender identities when more than one gender identity was described, but not reported in the study (added after registration of protocol). Health insurance type was categorized into two groups, public insurance and private insurance. Public insurance comprised Medicare, Medicaid, or other federally or state funded health insurance program. Private insurance comprised marketplace, employer, student, obtained through parent, or self-purchased health insurance plan.

Individual articles were evaluated for quality and risk of bias using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool.22 Due to the heterogeneity in study design and methodology, the NIH Quality Assessment Tool criteria were evaluated in the context of the purpose of this review (e.g., “was the study population clearly defined” was evaluated in the context of how gender identity was measured in the study).

Analysis was performed in STATA version 15.1.23 Insurance prevalence for the overall sample was analyzed to calculate a pooled estimate of the prevalence of health insurance among people who are GM. Heterogeneity was assessed using a Q-test and I2 measure.24 The summary statistics were calculated using a random-effects model and results are presented as meta-prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

To address study aims, subgroup analysis was performed for meta-prevalence estimates based on (1) gender subgroup and (2) sample collection before 2014 versus 2014 and after (pre- and post-ACA).18,25 Additional subgroup analyses were performed post hoc to address heterogeneity. Three variables were considered sources of potential heterogeneity, sample size, year of data collection, and source of sample recruitment.

Results

There were 13,518 articles identified using the selected search strategy (S1). Nine additional studies were identified by hand search. The identified articles were imported into Covidence where they were screened for duplicates; 7924 duplicate articles were removed. The remaining 5594 articles were screened by title/abstract; 4344 were eliminated based on inclusion/exclusion criteria, resulting in 1250 articles to be screened by full text (Fig. 1). During the full-text screening, 1194 were eliminated. Fifty-five studies were included in this review and analysis.9,26–79

A full description of the data presented below is in Table 1. The included studies collected data between 1997 and 2017, the median year of data collection was 2013. Four studies (7.3%) did not report the year of data collection.30,45,53,76 Twenty-eight studies (51%) collected data before the implementation of the ACA discrimination protections.27,32–35,38–40,44,47,49,52,54–57,59,60,64–67,69–71,74,77,79 One study (1.8%) collected data on separate samples both before implementation of the ACA and following.62

Table 1.

Characteristics of sample in studies that reported health insurance prevalence among gender minority people in the United States

| Author (Year) | Pre/During/Post ACA | Location | Urban Sample | Total Insured n (%) | Gender Identitya n (%) |

Quality Assessment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TW | TW Insured | TM | TM Insured | GE | GE Insured | ||||||

| Arayasirikul et al., (2017)32 | During | California | Yes | 125 (83.9) | 149 (100) | 125 (83.9) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Bazargan et al., (2012)33 | Pre | California | Yes | 62 (28.2) | 220 (100) | 62 (28.2) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Bockting et al., (2005)34 | Pre | Minnesota | No | 161 (89.0) | 141 (77.9) | NR | 34 (18.8) | NR | – | – | Low |

| Bradford et al., (2013)35 | Pre | Virginia | No | 248 (70.9) | 41 (11.7) | NR | 26 (7.4) | NR | 18 (5.1) | NR | Low |

| Braun et al., (2017)36 | Post | California | Yes | 64 (73.6) | 87 (100) | 64 (73.6) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Bukowski et al., (2018)37 | Post | National | Yes | 330 (78.2) | 422 (100) | 330 (78.2) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Clark et al., (2018)9 | Post | California | Yes | 217 (80.1) | 271 (100) | 217 (80.1) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Clements-Nolle et al., (2001)38 | Pre | California | Yes | 260 (50.5) | NE | – | NE | – | NE | – | Low |

| Conron et al. (2011)39 | Pre | Massachusetts | No | 113 (86.3) | NE | – | NE | – | NE | – | Low |

| Denson et al., (2017)40 | Pre | National | No | 87 (38.3) | 227 (100) | 87 (38.3) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Downing et al., (2018)41 | Post | National | No | 1,782 (80.2) | 1,073 (48.3) | 873 (81.4) | 699 (31.5) | 531 (76.0) | 449 (20.2) | 378 (84.1) | Moderate |

| Fein et al., (2018)42 | 2010–2016 NE |

Florida | Yes | 61 (88.4) | 69 (100) | 61 (88.4) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Fernandez et al., (2016)43 | 2008–2014 NE |

Kentucky | No | 42 (80.8) | 33 (63.5) | 25 (75.0) | 19 (36.5) | 17 (89.5) | – | – | Low |

| Harawa et al., (2009)44 | Pre | California | Yes | 74 (57.8) | 128 (100) | 74 (57.8) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Harb et al., (2019)45 | NR | Midwest | No | 17 (100) | – | – | 12 (70.6) | NR | 5 (29.4) | NR | Low |

| Hill et al., (2018)26 | Post | New York | Yes | 58 (89.2) | 65 (100) | 58 (89.2) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Jaffee et al., (2016)27 | Pre | National | No | 2,845 (81.6) | 2,068 (59.3) | 1,673 (80.9) | 1,418 (40.7) | 1,173 (82.7) | – | – | Low |

| Jennings et al., (2019)46 | Post | Wisconsin | No | 25 (100) | NR | – | NR | – | NR | – | Low |

| Juarez-Cuellar et al., (2017)47 | 2007–2013 NE |

New York | Yes | 6 (22.2) | 23 (85.2) | NR | 4 (14.8) | NR | – | – | Low |

| Kattari et al., (2016)48 | Post | Colorado | No | 407 (85.0) | 184 (44.1) | 153 (83.2) | 123 (29.5) | 106 (86.2) | 76 (18.2) | 68 (89.5) | Low |

| Kosenko et al., (2013)49 | Pre | National | No | 121 (79.6) | NE | NR | NE | NR | 32 (21.1) | NR | Low |

| Lemons et al., (2018)50 | 2009–2014 NE |

National | No | 29 (64.4) | – | – | 45 (100) | 29 (64.4) | – | – | Moderate |

| Light et al., (2018)28 | Post | National | No | 178 (90.8) | – | – | 139 (70.9) | NR | 19 (9.7) | NR | Low |

| Marshall et al., (2018)51 | Post | Arkansas | No | 83 (86.5) | 35 (36.5) | NR | 30 (31.2) | NR | 31 (32.3) | NR | Low |

| McDowell et al., (2017)52 | During | Massachusetts | Yes | 28 (90.3) | – | – | 11 (35.5) | NR | 20 (64.5) | NR | Low |

| Melendez et al., (2005)53 | NR | National | Yes | 19 (32.2) | 59 (100) | 19 (32.2) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Mizuno et al., (2017)54 | 2009–2013 NE |

National | No | 211 (81.8) | 258 (100) | 211 (81.8) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Newfield et al., (2006)52 | Pre | California | Yes | 282 (74.4) | – | – | 379 (100) | 282 (74.4) | – | – | Low |

| Peitzmeier et al., (2017)56 | During | Massachusetts | Yes | 27 (90.0) | – | – | 32 (100) | 27 (90.0) | – | – | Low |

| Peitzmeier et al., (2014)57 | Pre | Massachusetts | Yes | 186 (79.8) | – | – | 233 (100) | 186 (79.8) | – | – | Low |

| Perez-Brumer et al., (2018)58 | Post | Mississippi | No | 5 (35.7) | 8 (57.1) | 1 (12.5) | 6 (42.9) | 4 (66.7) | – | – | Low |

| Rachlin et al., (2008)59 | Pre | National | No | 100 (82.0) | – | – | 122 (100) | 100 (82.0) | – | – | Low |

| Radix et al., (2014)60 | During | New York | Yes | 36 (78.3) | 26 (56.5) | NR | 11 (23.9) | NR | 8 (17.4) | NR | Low |

| Rael et al., (2018)29 | Post | New York | Yes | 21 (75.0) | 28 (100) | 21 (75.0) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Rahman et al., (2018)61 | Post | National | No | 51 (83.6) | 34 (55.7) | 28 (82.4) | 27 (44.3) | 23 (85.2) | – | – | Low |

| Reback et al., (2018a)62 | Pre | California | Yes | 85 (34.8) | 244 (100) | 85 (34.8) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Reback et al., (2018b)62 | Post | California | Yes | 209 (77.1) | 271 (100) | 209 (77.1) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Reisner et al., (2018)63 | Post | Massachusetts | Yes | 144 (96.0) | – | – | 115 (76.7) | NE | 35 (23.3) | NE | Low |

| Reisner et al., (2010)64 | Pre | Massachusetts | Yes | 12 (75.0) | – | – | NE | NE | NE | NE | Low |

| Reisner et al., (2014)65 | Pre | Massachusetts | Yes | 18 (78.3) | – | – | 23 (100) | 18 (78.3) | – | – | Low |

| Reisner et al., (2013)66 | Pre | Pennsylvania | Yes | 62 (84.9) | – | – | 49 (67.1) | NE | 24 (32.9) | NE | Low |

| Reisner et al., (2015)67 | During | Massachusetts | Yes | 431 (95.4) | 125 (27.7) | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | Low |

| Salazar et al., (2017)68 | Post | Georgia | Yes | 43 (46.7) | 92 (100) | 43 (46.7) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Samuels et al., (2018)30 | NR | Rhode Island | No | 31 (96.9) | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | Low |

| Sanchez et al., (2009)69 | Pre | New York | Yes | 78 (77.2) | 101 (100) | 78 (77.2) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Seelman et al., (2017)31 | Post | Colorado | No | 349 (83.7) | 178 (42.7) | NR | 120 (28.8) | NR | 77 (18.5) | NR | Low |

| Sineath et al., (2016)70 | 2012–2013 NE |

National | No | 243 (86.8) | 234 (83.6) | 204 (87.2) | 46 (19.7) | 39 (84.8) | – | – | Low |

| Stanton et al., (2017)71 | Pre | National | No | 279 (69.4) | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | Low |

| Thompson et al., (2016)72 | Post | Illinois | Yes | 26 (86.7) | 23 (76.7) | 19 (82.6) | 4 (13.3) | 4 (100.0) | 3 (10.0) | 3 (100.0) | Low |

| Tran et al., (2018)73 | 2005–2015 NE |

National | No | 183 (48.0) | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | Low |

| White-Hughto et al., (2017)74 | During | Massachusetts | No | 346 (95.1) | 118 (32.4) | NR | 133 (36.5) | NR | 113 (31.0) | NR | Low |

| Whitehead et al., (2016)75 | Post | National | No | 137 (81.1) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Low |

| Wilson et al., (2015)77 | Pre | California | Yes | 268 (85.4) | 314 (100) | 268 (85.4) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Wilson et al., (2018)76 | Post | California | Yes | 148 (93.1) | 159 (100) | 148 (93.1) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Yamanis et al., (2018)78 | Post | Washington DC | Yes | 26 (68.4) | 38 (100) | 26 (68.4) | – | – | – | – | Low |

| Yang et al., (2016)79 | Pre | California | Yes | 117 (61.3) | 191 (100) | 117 (61.3) | – | – | – | – | Low |

A dash (–) signifies not in sample (e.g. sample was comprised of solely transgender women therefore cells pertaining to transgender men and gender expansive participants have a dash (–).

Gender Identity: GE, gender expansive; TM, transgender men; TW, transgender women.

ACA, Affordable Care Act; NE, not extractable (used in cases where items are select-all-that-apply or categories are mixed/conflated); NR, not reported.

Sample sizes of the included articles varied widely, from as few as 14 participants to as many as 3486 (m=267.6, SD=534.5). Studies with a sample size of <50 participants represented 25% of the articles (n=14).29,30,45–47,50,52,56–58,60,64,72,78 Five percent of studies had a sample size ≥515 (n=3).27,38,41 In regard to study location, the largest group of studies recruited nationally (n=15; 27.3%).27,28,37,40,41,49,50,53,54,59,61,70,71,73,75 This was followed by studies that took place in California (n=11; 20%),9,32,33,36,38,44,55,62,76,77,79 Massachusetts (n=8; 14.5%),39,52,56,57,63–65,67 and New York (n=5; 9.1%).26,29,47,60,69 Regionally, samples were predominantly representative of the northeastern U.S. (n=16; 29.1%)26,29,30,39,47,52,56,57,60,63–67,69,74; followed by the western U.S. (n=13; 24.6%),9,31–33,36,38,44,48,55,62,76,77,79 southern U.S. (n=7; 12.7%),35,42,43,51,58,68,78 and midwestern U.S. (n=4; 7.3%).34,45,46,72

The included studies used numerous methods to measure and categorize gender identity. Twenty-one of the included studies (38.2%) gathered data using a two-step method (i.e., inquiring both the participant's gender identity and sex-assigned-at-birth).27,31,35,41,50,51,53,54,57,59,61,63,64,66–68,70–72,74,75 Twenty-three (41.8%) of the included studies recruited people of a specific gender identity and categorization was limited to the study-defined gender used for inclusion criteria.9,26,28,29,32,33,36,37,40,42,44,50,52,55,57,59,62–64,69,76,77,79 Eleven (20%) of the included studies allowed for indication of the participant's self-identification as a transgender identity either by providing multiple options that included one or more gender-expansive identities or by allowing participants to enter their own.30,35,38,41,45,46,51,66–68,71

How the measurement of gender identity was applied to group participants into study categories also varied significantly. Five studies (9.1%) categorized participants as transgender based on sex-assigned-at-birth (e.g., male-to-female based on patient electronic health record) as opposed to participant's self-described gender identity.34,37,65–67 Four (7.3%) studies clustered the measured gender identities as a single category in their analysis (e.g., transgender) 30,45,51,71 and one study (1.8%) categorized participants into distinct groups that represented transmasculine, transfeminine, and gender-expansive identities.41

Four (7.3%) studies did not report their measurement of gender identity beyond including transgender individuals in their inclusion criteria,31,34,75,78 subsequently categorizing participants into one transgender group31,75 or by sex-assigned-at-birth.34,78 Three studies (5.5%) used chart documentation (e.g., ICD-9) and sex-assigned-at-birth to measure gender identity and subsequently categorized participants based on sex-assigned-at-birth.43,65,73 One of these studies (1.8%) categorized gender identity based on how feminine or masculine the participant's voice was perceived by the questionnaire administrator.39

The included articles were heterogenous regarding the race/ethnicity of participants (Table 1). Participants who were Asian/Pacific Islander were included in 14 of the studies (25.5%),38,39,41,48,55,56,63,65,66,69,71,73,77,79 Native American participants were included in 2 of the studies (3.6%),38,66 multiracial participants were included in 13 of the studies (23.6%),36,42,46,48,52,58,63,64,67,69,71,72,74 and 17 studies included people of other races/ethnicities (31.5%).35,36,41,51,55,56,60,65–68,71,74–77,79 Fourteen studies (25.5%) reflected 75% or more participants who were White or non-Hispanic.34,45,46,48,51,52,55,57,61,64,67,70,74,75 Two studies (3.6%) did not report race/ethnicity data.49,59 All studies measured race/ethnicity using self-report, with the exception of five studies that used medical records.42,43,56,65,73

The overall quality of the included articles was predominantly low (n=53; 96.4%). The remaining two articles were rated as of moderate quality (3.6%). There were no studies rated of high quality.

In 10 articles (18.2%), 90% or more of the participants reported having health insurance.28,30,45,46,52,57,63,65,67,74,76 Conversely, in seven articles (12.7%), 50% or fewer of the participants reported having health insurance.33,47,53,58,62,68,73 The median insurance prevalence was 80.5% (Table 1). Health insurance prevalence was disclosed for at least one gender identity subgroup in 31 articles (56.4%).26,27,32,33,36,36–38,40–44,46,50,53–59,61,65,68–70,76–79 Studies most frequently reported the health insurance prevalence among transgender women (n=25; 45.5%).9,26,27,29,32,33,36,37,40–44,53,54,58,61,62,68–70,76–79 Twelve articles reported health insurance prevalence for transgender men (21.8%).27,38,41,43,55–59,61,65,70

Only one study (1.8%) reported health insurance prevalence among gender-expansive people.41 After authors were contacted, two provided insurance prevalence for transgender women, transgender men, and gender-expansive people.48,72 Subsequently, the remaining 22 studies (40.0%) did not report health insurance prevalence among gender identity subgroups.28–31,34,35,39,45,47,49,51,52,60,62–64,66,67,67,71,73,75

A total of 26 articles (47.3%) reported the participant's type of health insurance27–29,31,35,36,38–40,44–46,50,61–63,65–67,69,70,72–74,76,78; however, 5 (9.1%) could not be divided into individual categories for public and private sources of insurance.28,31,36,46,70 The remaining articles (n=29; 52.7%) did not report this information.9,26,30,32–34,37,41–43,47–49,51–60,64,68,71,75,77,79 The articles that included the type of insurance held by participants reflected significant heterogeneity in the prevalence of public insurance versus private insurance. Studies reported public insurance prevalence as low as 6.2% and as high as 71.7%. Among the 26 articles that reported type of insurance, 7 reported 40% or more participants who had public health insurance.29,50,62,69,72,76,78

Among studies reporting the prevalence of health insurance among GM people, the summary analysis identified a random pooled estimate of 75% insured (95% CI: 0.71–0.79; p<0.001). Significant heterogeneity was identified (I2=97.74%). Two stratified analyses were performed to identify the source. No publication bias was found (Begg's test, p=0.317).

-

1.

Four subgroups were created, each representing quartiles of the study sample sizes: (1) 1 to 49 participants, (2) 51 to 149 participants, (3) 150 to 275 participants, and (4) 276+ participants.

This analysis identified a random pooled estimate of (1) 72% prevalence of health insurance (95% CI: 0.61–0.84; p<0.001; I2=89.66%), (2) 76% prevalence of health insurance (95% CI: 0.68–0.83; p<0.001; I2=91.48%), (3) 73% prevalence of health insurance (95% CI: 0.62–0.83; p<0.001; I2=98.57%), and (4) 79% prevalence of health insurance (95% CI: 0.72–0.85; p<0.001; I2=98.80%). While prevalence remained relatively consistent, the high degree of heterogeneity remains.

-

2.

Five subgroups were created to divide the included studies based on sample source: (1) clinics or hospitals; (2) community centers, events, or peer referrals; (3) solely online recruitment; (4) community centers, events, peer referrals, and online recruitment; and (5) population survey.

These analyses identified a random pooled estimate of (1) 67% prevalence of health insurance (95% CI: 0.51–0.82; p<0.001; I2=97.07%), (2) 68% prevalence of health insurance (95% CI: 0.61–0.76; p<0.001; I2=97.90%), (3) too few for analysis, (4) 86% prevalence of health insurance (95% CI: 0.81–0.91; p<0.001; I2=95.70%), and (5) 81% prevalence of health insurance (95% CI: 0.77–0.85; p<0.001; I2=7.02). While prevalence reflected more variability, the high degree of heterogeneity remained unresolved.

Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the random pooled estimate of health insurance by gender identity. Results found that 70% of transgender women were insured (95% CI: 0.64–0.76; p<0.001; I2=97.16%). Among transgender men, 80% were found to be insured (95% CI: 0.77–0.83; p=0.01; I2=54.51%). A high degree of heterogeneity was found in the analysis of insurance prevalence among transgender women; however, among transgender men, there was a moderate degree of heterogeneity. Too few studies provided health insurance prevalence data for gender-expansive participants; therefore, no analysis was performed.

Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the random pooled estimate of health insurance by pre- and post-ACA. Two subgroups were created to divide the included studies by year of data collection, using the median to inform the group division: (1) data collected before 2014 and (2) data collected 2014 or after. These analyses identified a random pooled estimate of (1) 75% prevalence of health insurance (95% CI: 0.69–0.80; p<0.001; I2=97.59%) and (2) 76% prevalence of health insurance (95% CI: 0.71–0.79; p<0.001; I2=97.90%).

Discussion

The pooled prevalence of 75% is more than 15% lower than the general population's prevalence at 91.2%, although heterogeneity remains unresolved.80 This is concerning because a lack of health insurance coverage poses several risks, such as of avoidance of care, as seen in one national study where 33% of GM respondents reported delayed treatment seeking due to cost concerns.7 Delayed treatment seeking has negative health consequences, including reduced treatment of acute and chronic illness and delayed detection of new illness or risk factors for illness.27,81–83

Research using nationally representative samples rarely measure gender identity,84 which greatly impairs our ability to interpret findings as they pertain to GM people.85,86 Moreover, gender-expansive people were greatly underrepresented among the included articles. This may be an artifact of dynamic gender identity terminology and of the limited terminology offered to participants to describe their gender identity in surveys, which may reduce the accuracy of these data. As reflected in this review, representation of gender-expansive identities is relatively uncommon within these studies and reduces the ability to determine whether this subpopulation is less likely to have health insurance.

While heterogeneity is a concern, we found little change in health insurance prevalence between studies that collected data in 2014 and later versus studies that collected data before 2014. This is of interest because of the passage of ACA and subsequent implementation of the federal antidiscrimination policy (i.e., sex discrimination, section 1557), protecting GM people from being refused health insurance based on their gender.87 While the bill's provisions did not go into effect in entirety until 2016, the public discourse, supreme court's decision to uphold the rule in 2012, and insurers' awareness of the upcoming change may have had an effect on the modest increase in prevalence that emerged from data gathered in 2014 and after.88 However, in the past 2 years the ACA has been significantly dismantled and anti-discrimination protections placed in jeopardy due to continued litigation and shifts in political leadership,89,90 thus it remains unknown if the health insurance rates observed here will remain or decline as these changes go into effect.

More detailed analysis of health insurance access based on gender identity, specifically among undersampled transgender men and gender-expansive people, should be undertaken to identify those who are most vulnerable to limited health care access. Further research into the insurance prevalence among racial and ethnic groups who are GM could also expand the findings of this meta-analysis and explore the potential socioeconomic sources of inequitable access to health insurance for GM people of color.

Analysis of policy implications, such as state Medicaid and Medicare restrictions and structure, should be performed to address potential structural barriers to health insurance access among GM people. In addition, the findings in this review suggest that GM people may rely upon public insurance at a rate higher (seven studies reported 40% or more) than the general population (34.4%),80 although few studies in this analysis used population-based samples. Future studies could evaluate adequacy of public health insurance coverage for the gender-affirming care, and mental and physical health needs of this population. A closer analysis of health-seeking behaviors, health insurance access, and health status may help to determine the degree to which lower insurance prevalence influences the health disparities and chronic conditions that are prevalent among GM people.5

Overall, health insurance prevalence among GM people appears to be well below the prevalence of 91.2% among the general population. While information on differences in health insurance access based on different gender identities is limited, the lowest rates of health insurance were observed among transgender women when compared to transgender men, although the scarcity of data among gender-expansive identities limits a thorough evaluation of these differences. In addition, there is a considerable reliance on public health insurance, which may point to vulnerability among GM people in non-Medicaid expansion states. Continued investigation into the barriers to insurance access is needed to help address these disparities among GM people when compared to the general population and to improve access to gender-affirming care and other health services.

Limitations

This systematic review and meta-analysis provided the first comprehensive review of health insurance status among GM people, which is available in peer-reviewed literature, but has some limitations. Health insurance prevalence is challenging to isolate due to its measurement as part of demographic or contextual data as opposed to the primary aim of a study; therefore, articles containing these data could have been missed despite a broad search strategy. The pooled prevalence also exhibited a high degree of heterogeneity that was not isolated. A further evaluation and subsequent understanding of the source of heterogeneity may also shed light on the contributing factors to the low prevalence of health insurance. Significant heterogeneity was also present in sampling strategies analyzed in the included studies.

Differences based on race and ethnicity, as well as age (individuals older than 65 and those younger) are important to consider, but the data to isolate these subgroup prevalences were not available for this review. Finally, California and Massachusetts were disproportionately overrepresented among the included studies, weakening representation among other states where GM people reside. After the implementation of ACA, some states rejected the expansion of Medicaid, whereas California and Massachusetts did not. This affects the access to public insurance for those who qualify in one state, but not another25 (e.g., California vs. Florida), and suggests that our results may overestimate the rates of health insurance among GM people.

Furthermore, there were multiple components of ACA that may affect GM people, including the provision that allowed adults younger than 26 years to remain on parent health insurance plans. We were unable to address these nuanced variations in implementation in our analysis. In addition, studies frequently omitted insurance prevalence among individual categories of gender, and almost entirely among gender-expansive people. Underreporting of insurance prevalence among individual gender categories prevents deeper analysis defining which groups are most likely to be uninsured, reducing opportunity for policy development to address gaps.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis placed a pooled prevalence of health insurance among GM people at 75%, considerably lower comapred with the general public (91.2%).80 The results also indicate that public health insurance may be more prevalent among GM people than the general population. The lack of specificity in demographic data (i.e., health insurance prevalence) assigned to people who are gender expansive exhibits an area of considerable opportunity and need. Inadequate access to health insurance impairs GM people from accessing preventative care services necessary to maintaining health and managing illness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the research assistance of Deborah Tan and Vivian Roan. The authors thank them for their contribution. Parts of this study were presented as a poster presentation at the American Academy of Nursing Annual Conference in October 2020, titled “Meta-Analysis of Health Insurance Among Gender Minorities.”

Abbreviations Used

- ACA

Affordable Care Act

- CI

confidence interval

- GM

gender minority

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SD

standard deviation

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

Kristen D. Clark was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research [Grant No. F31NR019000]. Athena D.F. Sherman was funded by the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University Post-doctoral to Faculty Fellowship. Annesa Flentje was partially supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grant No. K23DA039800]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this review.

Supplementary Material

Cite this article as: Clark KD, Sherman ADF, Flentje A (2022) Health insurance prevalence among gender minority people: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Transgender Health 7:4, 292–302, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0182.

References

- 1. Shi L, Singh DA. Delivering Health Care in America. Burlington, MA, USA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. USA: National Academies Press, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beerchick, E, Barnett, J, Upton, R. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2018. 2019. Available at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-267.pdf Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 4. Reisner SL, Conron KJ, Scout Nfn, et al. “Counting” Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Adults in Health Research: recommendations from the Gender Identity in US Surveillance Group. TSQ. 2015;2:34–57. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington D.C., USA: The National Academies Press, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender non-conforming people 7th version. Int J Transgend. 2012;13:165–232. [Google Scholar]

- 7. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, et al. Executive summary of the report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. 2015, Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hughto JMW, Reisner SL. A systematic review of the effects of hormone therapy on psychological functioning and quality of life in transgender individuals. Transgend Health. 2016;1:21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clark K, Fletcher JB, Holloway IW, Reback CJ. Structural inequities and social networks impact hormone use and misuse among transgender women in Los Angeles County. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47:953–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Asscheman H, T'Sjoen G, Lemaire A, et al. Venous thrombo-embolism as a complication of cross-sex hormone treatment of male-to-female transsexual subjects: a review. Andrologia. 2014;46:791–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moore E, Wisniewski A, Dobs A. Endocrine treatment of transsexual people: a review of treatment regimens, outcomes, and adverse effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3467–3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reback CJ, Fletcher JB. HIV prevalence, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors among transgender women recruited through outreach. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:1359–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McWilliams JM. Health consequences of uninsurance among adults in the United States: recent evidence and implications. Milbank Q. 2009;87:443–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brook RH, Keeler EB, Lohr KN, et al. The Health Insurance Experiment: A Classic RAND Study Speaks to the Current Health Care Reform Debate. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Freeman JD, Kadiyala S, Bell JF, Martin DP. The causal effect of health insurance on utilization and outcomes in adults: a systematic review of US studies. Med Care. 2008;46:1023–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maimaris W, Paty J, Perel P, et al. The influence of health systems on hypertension awareness, treatment, and control: a systematic literature review. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hadley J. Sicker and poorer—the consequences of being uninsured: a review of the research on the relationship between health insurance, medical care use, health, work, and income. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(2 Suppl):3S–75S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rangel C. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. House of Representatives 3590, 111th Cong. (2010). Available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/3590 Accessed March 9, 2020.

- 19. PRISMA. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Published 2009. Available at www.prisma-statement.org/ Accessed November 9, 2019.

- 20. Clark K, Sherman A, Flentje A. Health insurance prevalence among gender minority people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO 2019 CRD42019133627 Available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019133627 Accessed June 4, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org Accessed June 4, 2019.

- 22. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools. Available at https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools Accessed April 7, 2020.

- 23. StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palmer TM, Sterne JAC. Meta-Analysis in Stata: An Updated Collection from the Stata Journal. College Station, TX: Stata Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision. Published 2019. Available at https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/ Accessed April 21, 2020.

- 26. Hill BJ, Crosby R, Bouris A, et al. Exploring transgender legal name change as a potential structural intervention for mitigating social determinants of health among transgender women of color. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2018;15:25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jaffee KD, Shires DA, Stroumsa D. Discrimination and delayed health care among transgender women and men implications for improving medical education and health care delivery. Med Care. 2016;54:1010–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Light A, Wang L-F, Zeymo A, Gomez-Lobo V. Family planning and contraception use in transgender men. Contraception. 2018;98:266–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rael CT, Martinez M, Giguere R, et al. Barriers and facilitators to oral PrEP use among transgender women in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:3627–3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Samuels EA, Tape C, Garber N, et al. “Sometimes you feel like the freak show”: a qualitative assessment of emergency care experiences among transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71:170–182.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seelman KL, Young SR, Tesene M, et al. A comparison of health disparities among transgender adults in Colorado (USA) by race and income. Int J Transgend. 2017;18:199–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Arayasirikul S, Wilson EC, Raymond HF. Examining the effects of transphobic discrimination and race on HIV risk among transwomen in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:2628–2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bazargan M, Galvan F. Perceived discrimination and depression among low-income Latina male-to-female transgender women. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bockting WO, Robinson BE, Forberg J, Scheltema K. Evaluation of a sexual health approach to reducing HIV/STD risk in the transgender community. AIDS Care. 2005;17:289–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bradford J, Reisner SL, Honnold JA, Xavier J. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1820–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Braun HM, Candelario J, Hanlon CL, et al. Transgender women living with HIV frequently take antiretroviral therapy and/or feminizing hormone therapy differently than prescribed due to drug–drug interaction concerns. LGBT Health. 2017;4:371–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bukowski LA, Chandler CJ, Creasy SL, et al. Characterizing the HIV care continuum and identifying barriers and facilitators to HIV diagnosis and viral suppression among black transgender women in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79:413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Guzman R, Katz M. HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, health care use, and mental health status of transgender persons: implications for public health intervention. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Conron KJ, Scott G, Stowell GS, Landers SJ. Transgender health in Massachusetts: results from a household probability sample of adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:118–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Denson DJ, Padgett PM, Pitts N, et al. Health care use and HIV-related behaviors of black and Latina transgender women in 3 US metropolitan areas: results from the transgender HIV behavioral survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(Suppl 3):S268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Downing JM, Przedworski JM. Health of transgender adults in the US, 2014–2016. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:336–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fein LA, Cunha IR, Slomovitz B, Potter J. Risk factors for anal dysplasia in transgender women: a retrospective chart review. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2018;22:336–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fernandez JD, Tannock LR. Metabolic effects of hormone therapy in transgender patients. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:383–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Harawa NT, Bingham TA. Exploring HIV prevention utilization among female sex workers and male-to-female transgenders. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21:356–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Harb CYW, Pass LE, De Soriano IC, et al. Motivators and barriers to accessing sexual health care services for transgender/genderqueer individuals assigned female sex at birth. Transgend Health. 2019;4:58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jennings L, Barcelos C, McWilliams C, Malecki K. Inequalities in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health and health care access and utilization in Wisconsin. Prev Med Rep. 2019;14:100864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Juarez-Cuellar A, Chang Y-P. HIV testing in urban transgender individuals: a descriptive study. Transgend Health. 2017;2:151–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kattari SK, Walls NE, Speer SR, Kattari L. Exploring the relationship between transgender-inclusive providers and mental health outcomes among transgender/gender variant people. Soc Work Health Care. 2016;55:635–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kosenko K, Rintamaki L, Raney S, Maness K. Transgender patient perceptions of stigma in health care contexts. Med Care. 2013;51:819–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lemons A, Beer L, Finlayson T, et al. Characteristics of HIV-positive transgender men receiving medical care: United States, 2009–2014. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:128–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Marshall SA, Allison MK, Stewart MK, et al. Highest priority health and health care concerns of transgender and nonbinary individuals in a Southern State. Transgend Health. 2018;3:190–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McDowell M, Pardee DJ, Peitzmeier S, et al. Cervical cancer screening preferences among trans-masculine individuals: patient-collected human papillomavirus vaginal swabs versus provider-administered pap tests. LGBT Health. 2017;4:252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Melendez RM, Exner TA, Ehrhardt AA, et al. Health and health care among male-to-female transgender persons who are HIV positive. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1034–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mizuno Y, Beer L, Huang P, Frazier EL. Factors associated with antiretroviral therapy adherence among transgender women receiving HIV medical care in the United States. LGBT Health. 2017;4:181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Newfield E, Hart S, Dibble S, Kohler L. Female-to-male transgender quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1447–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Peitzmeier SM, Reisner SL, Harigopal P, Potter J. Female-to-male patients have high prevalence of unsatisfactory Paps compared to non-transgender femalesimplications for cervical cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:778–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Peitzmeier SM, Agénor M, Bernstein IM, et al. “It Can Promote an Existential Crisis”: factors influencing Pap test acceptability and utilization among transmasculine individuals. Qual Health Res. 2017;27:2138–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Perez-Brumer A, Nunn A, Hsiang E, et al. “We don't treat your kind”: assessing HIV health needs holistically among transgender people in Jackson, Mississippi. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0202389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rachlin K, Green J, Lombardi E. Utilization of health care among female-to-male transgender individuals in the United States. J Homosex. 2008;54:243–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Radix AE, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Gamarel KE. Satisfaction and healthcare utilization of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals in NYC: a community-based participatory study. LGBT Health. 2014;1:302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rahman M, Li DH, Moskowitz DA. Comparing the healthcare utilization and engagement in a sample of transgender and cisgender bisexual+ persons. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48:255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Reback CJ, Clark K, Holloway IW, Fletcher JB. Health disparities, risk behaviors and healthcare utilization among transgender women in Los Angeles County: a comparison from 1998–1999 to 2015–2016. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:2524–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Reisner SL, Deutsch MB, Peitzmeier SM, et al. Test performance and acceptability of self- versus provider-collected swabs for high-risk HPV DNA testing in female-to-male trans masculine patients. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Reisner SL, Perkovich B, Mimiaga MJ. A mixed methods study of the sexual health needs of New England transmen who have sex with nontransgender men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:501–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Reisner SL, White JM, Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ. Sexual risk behaviors and psychosocial health concerns of female-to-male transgender men screening for STDs at an urban community health center. AIDS Care. 2014;26:857–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Reisner SL, Gamarel KE, Dunham E, et al. Female-to-male transmasculine adult health: a mixed-methods community-based needs assessment. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2013;19:293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Reisner SL, Hughto JMW, Dunham EE, et al. Legal protections in public accommodations settings: a critical public health issue for transgender and gender-nonconforming people. Milbank Q. 2015;93:484–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Salazar LF, Crosby RA, Jones J, et al. Contextual, experiential, and behavioral risk factors associated with HIV status: a descriptive analysis of transgender women residing in Atlanta, Georgia. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28:1059–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sanchez NF, Sanchez JP, Danoff A. Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:713–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sineath RC, Woodyatt C, Sanchez T, et al. Determinants of and barriers to hormonal and surgical treatment receipt among transgender people. Transgend Health. 2016;1:129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Stanton MC, Ali S, Chaudhuri S. Individual, social and community-level predictors of wellbeing in a US sample of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19:32–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Thompson HM. Patient perspectives on gender identity data collection in electronic health records: an analysis of disclosure, privacy, and access to care. Transgend Health. 2016;1:205–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tran BNN, Epstein S, Singhal D, et al. Gender affirmation surgery: a synopsis using American college of surgeons national surgery quality improvement program and national inpatient sample databases. Ann Plast Surg. 2018;80(Suppl 4):S229–S235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. White-Hughto JM, Rose AJ, Pachankis JE, Reisner SL. Barriers to gender transition-related healthcare: identifying underserved transgender adults in Massachusetts. Transgend Health. 2017;2:107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Whitehead J, Shaver J, Stephenson R. Outness, stigma, and primary health care utilization among rural LGBT populations. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wilson EC, Turner C, Arayasirikul S, et al. Housing and income effects on HIV-related health outcomes in the San Francisco Bay Area—findings from the SPNS transwomen of color initiative. AIDS Care. 2018;30:1356–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wilson EC, Chen Y-H, Arayasirikul S, et al. Connecting the dots: examining transgender women's utilization of transition-related medical care and associations with mental health, substance use, and HIV. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2015;92:182–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Yamanis T, Malik M, Del Rio-Gonzalez AM, et al. Legal immigration status is associated with depressive symptoms among Latina transgender women in Washington, DC. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yang M-F, Manning D, van den Berg JJ, Operario D. Stigmatization and mental health in a diverse sample of transgender women. LGBT Health. 2015;2:306–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Berchick ER, Hood E, Barnett JC. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2017. United States Census Bureau. 2018. Available at https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-264.html Accessed October 6, 2020.

- 81. Kannan VD, Veazie PJ. Predictors of avoiding medical care and reasons for avoidance behavior. Med Care. 2014;52:336–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Byrne SK. Healthcare avoidance: a critical review. Holist Nurs Pract. 2008;22:280–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kale EE, Donald CA, Sattler AR, et al. Opportunities and gaps in primary care preventative health services for transgender patients: a systematic review. Transgend Health. 2016;1:216–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Patterson JG, Jabson JM, Bowen DJ. Measuring sexual and gender minority populations in health surveillance. LGBT Health. 2017;4:82–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Flentje A, Bacca CL, Cochran BN. Missing data in substance abuse research? Researchers' reporting practices of sexual orientation and gender identity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:280–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wood W, Eagly AH. Two traditions of research on gender identity. Sex Roles. 2015;73:461–473. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Department of Health and Human Services. Nondiscrimination in Health Programs and Activities; Final Rule. Natl Arch Rec Adm. 2016;81:1–99. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Transgender Law Center. Affordable Care Act Fact Sheet. 2016. Available at https://transgenderlawcenter.org/resources/health/aca-fact-sheet Accessed April 20, 2020.

- 89. Jaffe S. Dismantling the ACA without help from Congress. Lancet. 2017;390:441–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Secretary. Protecting Statutory Conscience Rights in Health Care; Delegations of Authority. Final Rule. 2019. Available at https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/final-conscience-rule.pdf Accessed April 8, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.