Abstract

The lic operon of Bacillus subtilis is required for the transport and degradation of oligomeric β-glucosides, which are produced by extracellular enzymes on substrates such as lichenan or barley glucan. The lic operon is transcribed from a ςA-dependent promoter and is inducible by lichenan, lichenan hydrolysate, and cellobiose. Induction of the operon requires a DNA sequence with dyad symmetry located immediately upstream of the licBCAH promoter. Expression of the lic operon is positively controlled by the LicR regulator protein, which contains two potential helix-turn-helix motifs, two phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS) regulation domains (PRDs), and a domain similar to PTS enzyme IIA (EIIA). The activity of LicR is stimulated by modification (probably phosphorylation) of both PRD-I and PRD-II by the general PTS components and is negatively regulated by modification (probably phosphorylation) of its EIIA domain by the specific EIILic in the absence of oligomeric β-glucosides. This was shown by the analysis of licR mutants affected in potential phosphorylation sites. Moreover, the lic operon is subject to carbon catabolite repression (CCR). CCR takes place via a CcpA-dependent mechanism and a CcpA-independent mechanism in which the general PTS enzyme HPr is involved.

The gram-positive soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis is able to use a wide variety of carbohydrates, among them several glucans as the only carbon source. For the utilization of polymeric carbon sources, the cell has to synthesize extracellular enzymes which degrade the polymers, and the oligomers have to be transported by specific uptake systems and introduced into the metabolism. The preferred carbon source is glucose, and expression of genes and operons whose gene products are involved in utilization of alternative carbon sources is strongly regulated, i.e., inducible by the specific substrate and repressed by preferred carbon sources (carbon catabolite repression [CCR]) (14, 41).

The bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS) takes part in the regulation of gene expression as a central element (33). Transport and coupled phosphorylation of its substrates constitute the primary task of the PTS. Other PTS functions include involvement in chemotaxis and in regulation of other metabolic processes (33, 36). The PTS is composed of the general proteins enzyme I (EI) and HPr and of the substrate-specific enzyme II (EII). The EII complexes represent the sugar-specific permeases, which consist of three or four subunits either fused in single multidomain proteins or built up of individual polypeptides (37). The proteins of the PTS transfer a phosphoryl group from phosphoenolpyruvate (the phosphoryl donor) to the carbohydrate to be transported (33).

In contrast to HPr of enteric bacteria, HPr from gram-positive bacteria is subject to phosphorylation at a seryl residue at position 46 by the ATP-dependent HPr kinase (PtsK or HprK) (7, 9, 11, 35) in addition to phosphorylation by EI-P on the histidyl residue at position 15. It has been shown that HPrSer-46-P is involved in CCR of B. subtilis (8). Glycolytic intermediates (e.g., fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and 2-phosphoglycerate) stimulate the activity of PtsK (35).

The availability of rapidly metabolizable carbon sources represses expression of genes or operons such as amyE, licTS, bglPH, lev, and xyl (13, 16, 18, 19, 23, 30). There is an operator sequence (catabolite-responsive element [cre]) serving as the target for the complex of the DNA binding protein CcpA and HPrSer-46-P (6, 13–15). Moreover, additional CcpA-independent mechanisms for CCR have been reported (17, 30, 44) (see below).

Induction of several catabolic operons occurs by increasing transcriptional initiation dependent either on transcriptional activators or on transcript elongation mediated by the action of transcriptional antiterminators (41). A class of these regulators contains two copies of a conserved structural motif, the PTS regulation domain (PRD) (42), which are involved in the regulation of the activity of the proteins. The activity is modulated by phosphorylation of highly conserved histidyl residues within the PRDs by the PTS in response to the availability of the substrate. The antiterminators BglG of Escherichia coli and SacY, SacT, GlcT, and LicT of B. subtilis and the activator protein LevR of B. subtilis belong to the family of PRD-containing regulators (42).

In the absence of their respective inducers, PRD-containing regulators such as LevR and BglG are phosphorylated by their corresponding EII. In the presence of the inducer, the PTS transports and phosphorylates the sugar and dephosphorylates PRD-containing regulators, thus allowing their activity. In the case of the LevR activator, it has been shown that the histidyl residue 869 of LevR can be phosphorylated by EIIBLev, causing inactivation of the regulator, if the inducer is absent (negative control) (27).

In addition to substrate-specific negative control of the activity of PRD-containing regulators, some of them are dependent on an alternative phosphorylation by HPr to be active (1, 17, 30, 44). By contrast, the B. subtilis antiterminators SacY and GlcT are active irrespective of HPr-dependent phosphorylation (4, 45). LicT and SacY are phosphorylated at three sites by HPr. The roles of the different phosphorylation sites have not yet been established (25, 47). Positive control of PRD-containing regulators is a novel mechanism of CCR in B. subtilis (42).

Control of protein activity by HPr-dependent phosphorylation was also demonstrated for glycerol kinase from Enterococcus faecalis (3) and the lactose transporter of Streptococcus thermophilus. In the latter protein, a domain similar to EIIAGlc is the target of phosphorylation (12).

We have recently identified a catabolic system in B. subtilis which is involved in uptake and utilization of oligomeric β-glucosides (46). It consists of five genes, which encode a PTS enzyme II complex (licA, licB, and licC), a 6-phospho-β-glucosidase (licH), and a positive regulator protein (licR). These five genes are organized in two transcriptional units. A weak promoter precedes the monocistronic gene licR. The genes licB, -C, -A, and -H constitute an operon. Expression of this lic operon is inducible by β-glucans, such as lichenan, and their degradation products (e.g., lichenan hydrolysate and cellobiose) and is repressed by rapidly metabolized carbon sources. Moreover, expression of the lic operon requires the general PTS components and seems to be negatively controlled by the specific Lic PTS enzymes. Initiation of transcription presumably requires activation by the gene product of licR. The LicR protein contains two potential helix-turn-helix motifs, two PRDs, and a C-terminal domain similar to mannitol-specific PTS EIIA. Thus, LicR represents a novel prototype of PRD-containing regulators (42).

The present study was aimed at the elucidation of the lic operon regulation by trans-acting factors, especially LicR. We report about the construction of B. subtilis strains encoding LicR affected in the putative phosphorylation sites of both the PRDs and the EIIA domain. The involvement of trans-acting factors and presumptive regulatory DNA regions around the licB promoter was investigated by use of a variety of licB′-lacZ fusions in different genetic backgrounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The B. subtilis strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli DH5α [F− φ80 ΔlacZM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 gyrA96] and RR1 [F− Δ(gpt-proA)62 mcrB mrr ara-14 lacY1 leuB6 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 supE44] (38) were used as hosts for plasmid construction. These strains were grown in nutrient broth medium (19). For selection of transformants, ampicillin was added to a final concentration of 100 mg/liter. B. subtilis cells were grown in ASM minimal medium (43) or in SP medium (28) supplemented with auxotrophic requirements under vigorous agitation at 37°C. The following carbon sources were used as supplements: 0.1% ribose, 0.3% glucose, 0.05% cellobiose, 0.1% lichenan hydrolysate, or 0.2% lichenan. The hydrolysate of lichenan was prepared as described previously (40). Agar plates were prepared by addition of 15 g of Bacto agar/liter. Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: chloramphenicol, 5 mg/liter; erythromycin, 1 mg/liter; lincomycin, 25mg/liter; and spectinomycin, 100 mg/liter.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypea | Source or referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| IS58 | trpC2 lys-3 | Laboratory stock |

| BGT2330b | trpC2 lys-3 amyE::(licB′[2330]-lacZ cat) | pST2330b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2430b | trpC2 lys-3 amyE::(licB′[2430]-lacZ cat) | pST2430b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2530b | trpC2 lys-3 amyE::(licB′[2530]-lacZ cat) | pST2530b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2530b1D | trpC2 lys-3 licRH219D amyE::(licB′[2530]-lacZ cat) | pSTLicR219D, BGT2530b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2530b1A | trpC2 lys-3 licRH219A amyE::(licB′[2530]-lacZ cat) | pSTLicR219A, BGT2530b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2530b2E | trpC2 lys-3 licRH278E amyE::(licB′[2530]-lacZ cat) | pSTLicR278E, BGT2530b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2530b2A | trpC2 lys-3 licRH278A amyE::(licB′[2530]-lacZ cat) | pSTLicR278A, BGT2530b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2530b3A | trpC2 lys-3 licRH333A amyE::(licB′[2530]-lacZ cat) | pSTLicR333A, BGT2530b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2530b4E | trpC2 lys-3 licRH392E amyE::(licB′[2530]-lacZ cat) | pSTLicR392E, BGT2530b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2530b4I | trpC2 lys-3 licRH392I amyE::(licB′[2530]-lacZ cat) | pSTLicR392I, BGT2530b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2530b5G | trpC2 lys-3 licRH559G amyE::(licB′[2530]-lacZ cat) | pSTLicR559G, BGT2530b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2730b | trpC2 lys-3 amyE::(licB′[2730]-lacZ cat) | pST2730b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2830b | trpC2 lys-3 amyE::(licB′[2830]-lacZ cat) | pST2830b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2930b | trpC2 lys-3 amyE::(licB′[2930]-lacZ cat) | pST2930b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2332b | trpC2 lys-3 amyE::(licB′[2332]-lacZ cat) | pST2332b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2433b | trpC2 lys-3 amyE::(licB′[2433]-lacZ cat) | pST2433b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2733b | trpC2 lys-3 amyE::(licB′[2733]-lacZ cat) | pST2733b tf→IS58 |

| BGT2833b | trpC2 lys-3 amyE::(licB′[2833]-lacZ cat) | pST2833b tf→IS58 |

| BGT63 | trpC2 lys-3 licH′-lacZ cat | 46 |

| BGT635 | trpC2 lys-3 licH′-lacZ cat ccpA::Tn917 spc | QB5407 tf→BGT63 |

| QB5407 | trpC2 ccpA::Tn917 spc | 10 |

cat, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene; spc, spectinomycin resistance gene.

tf→, transformation.

Genetic techniques.

Standard techniques were used for plasmid extraction from E. coli (38), isolation of chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis (26), transformation of E. coli by the CaCl2 method (38), and transformation of B. subtilis strains by the two-step protocol described by Kunst and Rapoport (21).

Treatment of DNA with restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase, and T4 polynucleotide kinase was performed as recommended by the supplier. DNA fragments and PCR products were purified by using Wizard Prep kits (Promega) or recovered from agarose gels by using a GeneClean II kit (Bio 101, Inc.). DNA sequences were determined by the chain termination method (39) with modified T7 DNA polymerase (U.S. Biochemicals Corp.) and plasmid DNA or PCR product as a template.

PCR products were obtained under conditions described previously (46). Unless otherwise described, PCRs were carried out with chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis IS58 as a template. Prior to ligation of the PCR products with vector plasmids, the DNA was purified by the Double GeneClean procedure (Bio 101, Inc.). The resulting plasmids were subsequently sequenced to exclude potential PCR artifacts.

Plasmid constructions and site-directed mutagenesis.

Translational lacZ fusions were constructed by using the vector pAC5 (29), which carries the chloramphenicol resistance gene (cat) from pC194. The plasmid contains a lacZ gene without expression signals located between two fragments of the B. subtilis amyE gene. The pAC5 derivatives pSTnb were obtained by cloning PCR products containing different parts of the DNA sequence around the licB promoter (n is the name of the DNA fragment [Fig. 1]) into the vector plasmid. PCR products were generated as outlined in Fig. 1. Prior to ligation of the PCR products with pAC5, both the vector and the respective DNA fragment were digested with BamHI and EcoRI. The resulting plasmids were analyzed by sequencing. Plasmids containing different translational licB′-lacZ fusions were digested with ScaI for transformation of B. subtilis wild-type strain IS58 (Table 1).

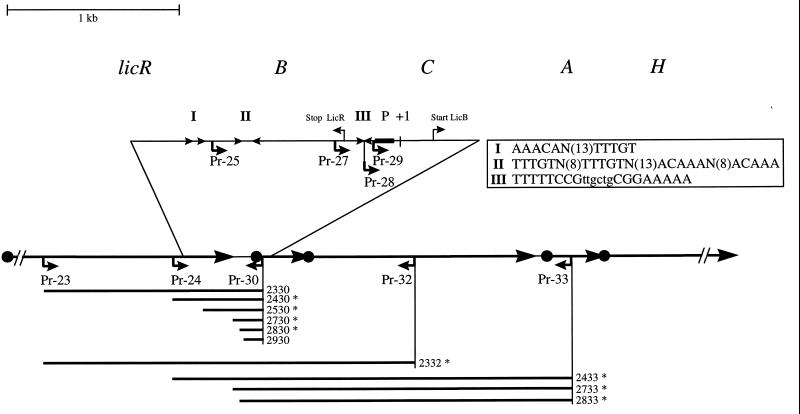

FIG. 1.

PCR fragments used for construction of different licB′-lacZ fusions. Oligonucleotides (Pr-n); their orientations (↲), lengths, and positions (bars); names of the DNA fragments used in plasmid construction; genes of the system (•➞); putative cis-acting sequences (I [▸ ▸], II [▸ ◂], and III [▸◂]; the promoter (P); and the transcriptional start point (+1) of the lic operon are indicated. ∗, DNA fragments and lacZ fusions used for β-galactosidase assays from liquid cultures.

A mutagenesis method based on PCR (22) was used to construct plasmids containing mutant alleles of licR. The strategy for this approach is shown in Fig. 2. Mutagenesis of the triplets encoding histidyl residues probably involved in the control of LicR activity was performed in first PCR steps with the mutagenic primer 219D (5′-CCTCATTATCGATATCGCTATC-3′) or 219A (5′-CCTCATTATCGCGATCGCTATC-3′) and the primer Pr-45 (5′-GGAATTCCGGGTGCTGATGACAAAATC-3′; the attached EcoRI site is doubly underlined) for residue His-219, the mutagenic primer 278E (5′-CTACATCACCATGGAGCTCCTTG-3′) or 278A (5′-CTACATCACCATGGCGCTCCTTG-3′) and Pr-45 for His-278, the mutagenic primer 333A (5′-CTTGGCACTCGCGATGAAGC-3′) and Pr-45 for His-333, the mutagenic primer 392E (5′-GATATTTGGCTCTCGAGTTTGGCG-3′) or 392I (5′-GATATTTGGCTCTAATATTTGGCG-3′) and Pr-45 for His-392, and the mutagenic primer 559G (5′-CATCCCGGGGCCGCTTGTTC-3′) and Pr-42 (5′-GGAATTCCGTCAGCTCAGCATTTTTTG-3′); the attached EcoRI site is doubly underlined) for His-559 (nonmatching nucleotides are underlined). The PCR products were used as primers in a second PCR together with the primer Pr-44 (5′-GAGAGGATCCTGAAGCTGCGCGGGGACGAG-3′; the nonmatching nucleotides are underlined, and the attached BamHI site is doubly underlined). The mutagenic primers were designed such that a novel restriction site was introduced upon mutagenesis (these sites are shown in italics). Thus, the presence of desired mutations could be verified by restriction analysis of the final PCR products. After verification of the expected restriction pattern, the PCR products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated with integrative plasmid pHT181 (24) treated with the same enzymes.

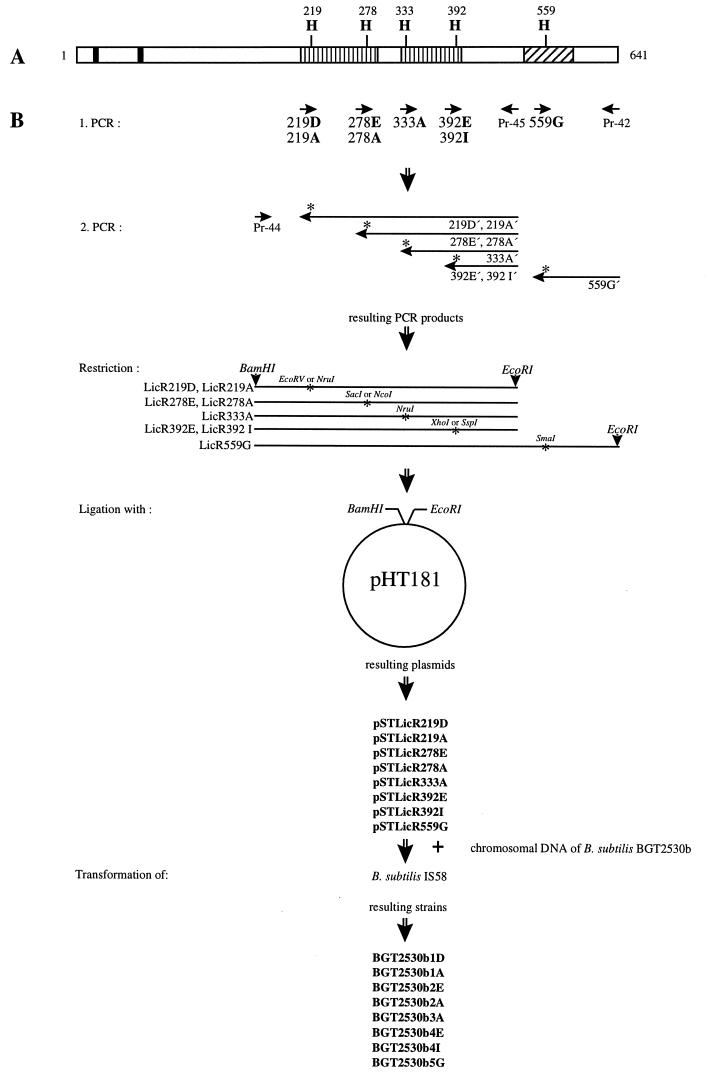

FIG. 2.

Site-directed mutagenesis of licR. (A) Domain structure of LicR and positions of putative phosphorylation sites (H, histidine). The two putative helix-turn-helix motifs are indicates by bars. The PRDs having similarity to PRD-containing regulator proteins (▥) and the domain of LicR which shows similarities to PTS EIIA proteins (▨) are shown. (B) Mutageneses of residues His-219, His-278, His-333, His-392, and His-559 were performed by amplification of licR fragments with the indicated mutagenic oligonucleotides (219D, 219A, 278E, 278A, 333A, 392E, 392I, and 559G) and the oligonucleotides Pr-45 and Pr-42. The PCR products were used as megaprimers in a second PCR with the oligonucleotide Pr-44. The resulting DNA fragments containing the mutation and a new restriction site (∗; the restriction sites are indicated) were digested with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated with the plasmid pHT181 (24) which was treated with the same enzymes. B. subtilis IS58 was cotransformed with the resulting plasmids and chromosomal DNA of strain BGT2530b. The names of the resulting plasmids and strains are indicated.

The resulting plasmids were named pSTLicR followed by the position of the mutated amino acid in LicR and the inserted amino acid in one-letter code, e.g., pSTLicR219D (Fig. 2), and served as template in PCRs with primers Pr-44 and Pr-45 or Pr-42. These PCR products were also verified by restriction analysis.

Construction of B. subtilis strains containing mutations in licR.

The point mutations present in the plasmids pSTLicR219D to pSTLicR559G were introduced into the B. subtilis chromosome by cotransformation of strain IS58 with chromosomal DNA of strain BGT2530b (licB′[2530]-lacZ cat) and the respective plasmid.

Expression of the lic operon is inducible by lichenan, and a licR::neo mutation prevents expression of the operon (46). We used these effects to screen for introduction of point mutations into the licR gene in the chromosome of B. subtilis. Cmr transformants were analyzed by a screening test (see below) for expression of the lic operon. Colonies which showed a pattern of β-galactosidase activity different from that of the wild-type strain on plates were checked for sensitivity to erythromycin to verify that the vector part of the plasmid was lost. The resulting strains (Table 1; Fig. 2) were designated BGT2530b followed by the number of the replaced residue (1, His-219; 2, His-278; 3, His-333; 4, His-392; 5, His-559) and the name of the new amino acid in one-letter code, e.g., BGT2530b1D (licB′[2530]-lacZ cat licRH219D).

To demonstrate that the detected phenotypes were caused by the introduced licR mutations, we amplified fragments containing the licR allele by PCR with the oligonucleotides Pr-44 and Pr-45 (for residues 219, 278, 333, and 392) or Pr-42 (for residue 559). The PCR fragments were analyzed for the presence of the restriction sites which were introduced upon mutagenesis. All tested strains contained a new restriction site in the licR gene. Thus, the respective licR mutations were correctly introduced in all strains. In addition, the licR alleles of the constructed strains were reisolated by PCR and analyzed by nucleotide sequencing. No mutations in addition to those introduced were present.

Assay of β-galactosidase activity.

B. subtilis cultures were grown in ASM supplemented with ribose or glucose for noninducing conditions or with the inducing substrate lichenan, lichenan hydrolysate, or cellobiose. Both glucose and an inducing carbon source were supplemented if CCR of the lic operon was being investigated. Cells were harvested (2-ml samples) 1.5 h after the culture entered stationary phase. The samples were stored at −20°C until the assay was carried out, as described by Miller (31). Cells were permeabilized with toluene.

For the screening test of β-galactosidase activity, the cells were plated on SP plates containing either no additional substrate or lichenan or cellobiose and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (50 mg/liter). The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C. Strains showing the same induction pattern as the wild type formed white colonies on the control plates and blue colonies under inducing conditions.

RESULTS

Involvement of CcpA in expression of the lic operon.

Recently, we have reported that the supplementary addition of glucose to inducing carbon sources results in loss of expression of a licH′-lacZ fusion, and a putative cre sequence was identified in the spacer region of the licBCAH promoter (46). We tested the involvement of CcpA in CCR of the lic operon. Strain BGT63 (licH′-lacZ cat) was transformed with chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis QB5407 (ccpA::Tn917 spc). The resulting strain, BGT635, and the isogenic wild-type strain BGT63 were grown in ASM supplemented with either ribose, lichenan hydrolysate, or lichenan. The presence of lichenan hydrolysate and lichenan resulted in a strong increase of β-galactosidase activity compared to that under the noninducing conditions (ribose) in both strains (data not shown). As described above, no β-galactosidase activity was detectable in the reference strain upon addition of glucose to the inducing substrates. The average repression ranged from 160-fold (lichenan hydrolysate compared to lichenan hydrolysate plus glucose) to 330-fold (lichenan compared to lichenan plus glucose). By contrast, only fivefold repression was observed in the ccpA genetic background (Table 2). This indicates that CcpA is involved in CCR of the lic operon. The incomplete abolishment of CCR in BGT635 could be caused by a CcpA-independent mechanism (see Discussion).

TABLE 2.

Influence of CcpA on CCR of the lic operona

| Strain | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% LHb | 0.1% LH and 0.3% glucose | 0.2% lichenan | 0.2% lichenan and 0.3% glucose | ||

| BGT63 | Wild type | 257 | 1.6 | 264 | 0.8 |

| BGT635 | ccpA::Tn917 spc | 358 | 75 | 301 | 77 |

Cells were grown in ASM supplemented with carbon sources as indicated. For the β-galactosidase assay, samples were taken after cultures entered stationary phase. Three independent experiments were performed, and representative results are shown.

LH, lichenan hydrolysate.

Identification of a sequence motif responsible for induction of the lic operon.

As reported previously, the intergenic region between licR and licB extends over 50 nucleotides. Upstream of licB, putative cis-acting sequences could be identified (Fig. 1, regions I, II, and III). The deduced −35 region of the licB promoter has rather weak similarity to promoters recognized by the vegetative RNA polymerase (46). Induction of the lic operon requires the LicR protein and a cis-acting sequence as the target. The target for induction of the lic operon is located in the regulatory region around the licB promoter. This was shown by analyzing a transcriptional licB′-lacZ fusion containing a 2.04-kb DNA fragment of the licB promoter region in front of the promoterless lacZ gene (46). Transcriptional and translational licB′-lacZ fusions showed similar levels and regulation patterns of β-galactosidase activity, suggesting that induction takes place at the level of transcription (45a).

To identify the DNA region involved in induction of the operon, a set of strains containing different licB′-lacZ translational fusions was constructed (see Materials and Methods) (Table 1; Fig. 1). These strains were plated on X-Gal–SP plates containing either no supplemented carbon source (control) or an inducing substrate (cellobiose or lichenan). The results are summarized in Table 3. All strains formed white colonies in the absence of an inducer, indicating that the licB promoter was not active. Strains containing lacZ fusions with DNA regions spanning from position −1196 (with respect to the transcriptional start point of licB) (Fig. 1, forward primer Pr-23) to positions +84 and +966 (Fig. 1, reverse primer Pr-30 to Pr-32) showed the same induction pattern as the wild type, indicating that the DNA sequence located downstream of the licB promoter is not required for regulation of the lic operon.

TABLE 3.

Screening test with different licB′-lacZ fusionsa

| Strain | PCR fragmentc | β-Galactosidase activity on SP plates withb:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No addition (control) | 0.05% cellobiose | 0.2% lichenan | ||

| BGT2330b | 2330 | − | + | + |

| BGT2332b | 2332 | − | + | + |

| BGT2430b | 2430 | − | + | + |

| BGT2433b | 2433 | − | + | + |

| BGT2530b | 2530 | − | + | + |

| BGT2730b | 2730 | − | + | + |

| BGT2733b | 2733 | − | + | + |

| BGT2830b | 2830 | − | − | − |

| BGT2833b | 2833 | − | − | − |

| BGT2930b | 2930 | − | − | − |

Cells were plated on SP plates containing either no additional carbon sources (control) or an inducing substrate as indicated and X-Gal. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C.

The color of the colonies, as an indication of the β-galactosidase activity (−, white; +, blue), was determined.

See Fig. 1.

Deletions of the sequence located upstream of the lic promoter containing putative cis-acting sequences were constructed as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1). Strains harboring fusions of the promoterless lacZ gene with DNA fragments starting at positions −1196 to −92 (with respect to the transcriptional start point of licB) (Fig. 1, forward primer Pr-23 to Pr-27) formed blue colonies on plates with cellobiose or lichenan, as did the isogenic wild-type strain. In contrast, strains containing lacZ fusions with DNA fragments starting in the middle of the region exhibiting dyad symmetry of region III (Fig. 1, position −52, primer Pr-28) or downstream of region III (Fig. 1, position −39, primer Pr-29) did not show any β-galactosidase activity (Table 3). This indicates that motifs I and II (Fig. 1) were not necessary for induction of the system but that sequence III (Fig. 1) might be the target for induction.

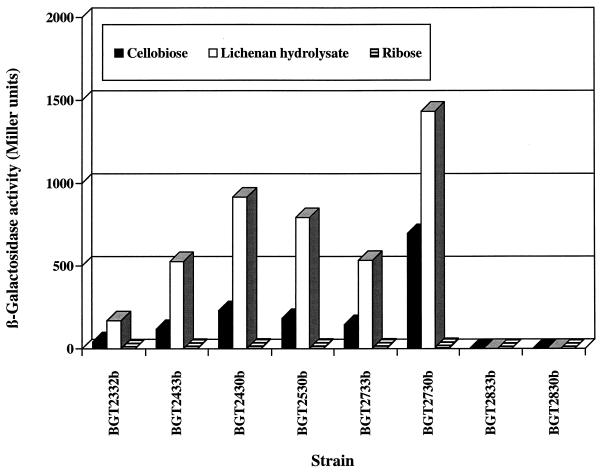

To verify the assumption that the region required for regulation of the system is located immediately upstream of the −35 region of the licB promoter, we chose some of these strains, which cover the regulatory region (Fig. 1, asterisks), for β-galactosidase assays. Cells were grown in ASM under inducing or noninducing conditions. The β-galactosidase activity was inducible by cellobiose (induction ratio of 50- to 140-fold) and lichenan hydrolysate (induction ratio of 180- to 320-fold) in strains BGT2332b to BGT2730b, but strains in which the complete region III exhibiting dyad symmetry was not present (BGT2833b and BGT2830b) showed no β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 3). Thus, these results were consistent with the observations from the screening test; i.e., the induction of the lic operon depends on the sequence with dyad symmetry (5′-TTTTTCCGttgctgCGAAAAA-3′) situated immediately in front of the licB promoter.

FIG. 3.

Activity of β-galactosidase from selected licB′-lacZ fusions. Growth conditions and sample collection were as described in Table 2, footnote a. Representative results from three independent experiments are shown.

Characterization of potential phosphorylation sites of LicR by site-directed mutagenesis.

LicR belongs to the PRD-containing regulators, which can be modified in their activity by phosphorylation of highly conserved histidyl residues by the PTS (42). To investigate the possible involvement of the conserved histidyl residues in the PRDs and the EIIA domain (Fig. 2 and 4) in the modification of the LicR activity and consequently in the regulation of the lic operon, we constructed mutants in which these residues were replaced by other amino acids. The strategy and construction of strains containing both a mutant allele of licR and the licB′-lacZ fusion are described in Materials and Methods (Table 1; Fig. 2).

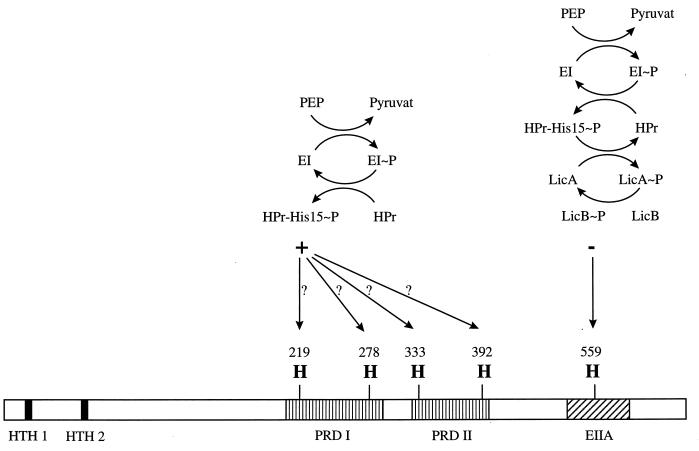

FIG. 4.

Proposed model for the regulation of LicR activity by the PTS. The activity of LicR is stimulated by phosphorylation of histidyl residues in both PRD-I and PRD-II of LicR by HPrHis-15-P. Replacement of any of these histidyl residues results in loss of LicR activity and thus of induction of the lic operon. In the absence of lichenan hydrolysate, the PTS EIILic is phosphorylated, and its components (LicA and LicB) may phosphorylate the PTS EIIA domain of LicR, causing inactivation of it regardless of the phosphorylation status of the PRDs. In the presence of lichenan hydrolysate, LicA and LicB and subsequently the EIIA-like domain of LicR are dephosphorylated. The PTS EIIA domain of LicR cannot be phosphorylated in licRH559G and EIILic mutants. Therefore, the lic operon is constitutively expressed in these mutants, as it is in the wild type under inducing conditions. Modification of LicR via phosphorylation by HPr may be involved in CCR. In the presence of rapidly metabolizable PTS sugars, the competition of the sugar-specific PTS EIIs and the PRD of LicR for the phosphoryl donor HPrHis-15-P will lower the level of phosphorylation of the PRDs of LicR and thus attenuate activity of LicR.

First, the licR mutant strains and the isogenic wild-type strain (BGT2530b) were analyzed in a screening test by cultivation on X-Gal–SP plates in the absence or presence of an inducer (see Materials and Methods). Strains carrying mutations affecting the histidyl residues in the PRDs of LicR formed white colonies under noninducing conditions, as observed with the wild-type strain. In contrast, a mutation in the residue equivalent to the phosphorylation site in EIIAMtl (34) (licRH559G) resulted in the formation of blue colonies in the absence of inducer, indicating activity of the mutant LicR protein under noninducing conditions. While the wild-type strain formed blue colonies on plates containing lichenan, no expression of the licB′-lacZ fusion was detectable when the histidyl residues of the PRDs were replaced by nonphosphorylatable amino acids, suggesting that the histidyl residues in the PRDs of LicR are required for activity. As observed in the absence of inducer, strain BGT2530b5G, harboring the licRH559G mutant allele of licR, formed blue colonies on plates containing lichenan. This LicR protein therefore has constitutive activity.

Second, we investigated the influence of these different mutations on the activity of LicR in β-galactosidase assays. Strains containing mutant alleles of licR and the isogenic wild-type strain (BGT2530b) were grown in ASM supplemented with either ribose, glucose, cellobiose, lichenan hydrolysate, or both glucose and an inducing carbon source. The results of these experiments are shown in Table 4. As described above, expression of the lic operon was induced by cellobiose and lichenan hydrolysate in the wild-type strain. In contrast, loss of expression occurred in such strains in which one of the four conserved histidyl residues of PRD-I (219 and 278) or PRD-II (333 and 392) was replaced by aspartic acid or glutamic acid. Similar results were obtained upon replacement of the conserved histidyl residues by neutral amino acids. Induction of the licB′-lacZ fusion was lost in strains BGT2530b2A (licRH278A) and BGT2530b3A (licRH333A) and was reduced to a minor level in strains BGT2530b1A (licRH219A) and BGT2530b4I (licRH392I). Thus, the conserved histidyl residues of both PRDs are necessary for LicR activity.

TABLE 4.

Effect of point mutations in licR on β-galactosidase activity of the translational licB′[2530]-lacZ fusiona

| Strainb | Relevant genotypec | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) withd:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% ribose | 0.3% glucose | 0.05% cellobiose | 0.1% LHe | ||

| BGT2530b | Wild type | 2.9 | 1.3 | 182 (1.8) | 794 (0.9) |

| BGT2530b1D | licRH219D | 1.3 | 0.6 | 4.6 (0.9) | 3.1 (0.5) |

| BGT2530b1A | licRH219A | 0.8 | 0.3 | 14.9 (0.3) | 37.5 (0.2) |

| BGT2530b2E | licRH278E | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.9 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| BGT2530b2A | licRH278A | 0.4 | 0.5 | 2.8 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.4) |

| BGT2530b3A | licRH333A | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) |

| BGT2530b4E | licRH392E | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.3) |

| BGT2530b4I | licRH392I | 0.6 | 0.4 | 9.6 (0.5) | 18.8 (0.3) |

| BGT2530b5G | licRH559G | 922 | 16 | 241 (15) | 829 (16) |

Growth conditions and sample collection were as described in Table 2, footnote a. Representative results from three independent experiments are shown.

See Fig. 1.

The position of the histidine residue within LicR exchanged for another amino acid and the designation of the new residue in one-letter code are indicated.

Values in parentheses are those when 0.3% glucose was also added.

LH, lichenan hydrolysate.

High-level expression of the licB′-lacZ fusion occurred under inducing or noninducing conditions when the conserved histidyl residue 559 in the EIIA domain of LicR was replaced by glycine. Thus, the histidyl residue at position 559 seems to be the target of negative regulation of LicR activity by PTS EIILic, because the expression of the licB′-lacZ fusion was constitutive in both a licRH559G mutant and a licC::neo genetic background (data not shown).

Summarizing these results, we suggest that all tested histidyl residues are involved in the modification of the LicR activity. CCR of the lic operon is not affected by replacement of the five histidyl residues (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Expression of the lic operon in B. subtilis is induced in the presence of oligomeric β-glucosides, which are the degradation products of polymeric β-glucans (40, 46), and is repressed by glucose or other rapidly metabolized carbon sources (46). We present data showing that the regulatory protein LicR, the proteins of the PTS, and the CcpA protein are involved in the regulation of licBCAH gene expression.

In B. subtilis the CcpA protein, the HPr protein, and a catabolite-responsive element (cre) are involved in CCR (13–15). A potential cre sequence was identified in the licBCAH promoter region (46). As observed with other catabolic systems, glucose repression of the lic operon decreases drastically in a ccpA mutant, indicating that CcpA is involved in the regulation of licBCAH expression by glucose. In addition, the arrangement of the cre is similar to that for other catabolic systems which are subject to CCR (e.g., bglPH) (18). Thus, CCR of licBCAH expression follows the CcpA- and cre-dependent mechanism which was investigated intensively for catabolic systems in B. subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria (14). However, CCR of the lic operon was not completely abolished in the ccpA mutant; i.e., a residual repression was observed. It thus seemed possible that a CcpA-independent mechanism is additionally involved in CCR of the lic operon. CcpA-independent CCR was described for the lev and bglPH operons of B. subtilis and involves positive control of PRD-containing operon-specific regulators by the HPr protein of the PTS (17, 30, 44).

The −35 region of the licBCAH promoter has rather weak similarity to promoters recognized by the vegetative RNA polymerase, and expression of a licB′-lacZ fusion is strongly inducible. Thus, we suggested the requirement of a transcriptional activator (LicR) and a target site recognized by the activator, which is located close to the promoter (46). During the DNA sequence analysis of the lic system, three motifs upstream of the promoter were identified (Fig. 1). Two of these sequences are located within the coding region of licR, whereas the third motif (motif III) is located within the intergenic region between licR and licB (immediately upstream of the licBCAH promoter). Deletion analysis of the promoter region revealed that only region III is required for induction of the lic operon. This inverted repeat might therefore be a target for the binding of the transcriptional activator LicR.

Sequence analysis of the complete B. subtilis genome (20) by using the SubtiList server (32) indicates that sequence motif III, with one mismatch in the dyad symmetry and differences in the length of the spacer, is present upstream of yjdC (manR) (20, 42) and yvfQ (encoding a putative endo-1,4-β-galactosidase) (20). The ManR protein, with a domain structure similar to that of LicR, is probably involved in the regulation of genes necessary for mannose utilization (yjdD and yjdE) (20).

LicR regulates the expression of the lic operon by acting as an activator (reference 46 and this work). In addition to the antiterminator BglG of E. coli and the activator LevR of B. subtilis, LicR is a prototype of a novel group of PRD-containing regulators (42). These positive regulators are controlled in their activity by PTS-dependent phosphorylation on highly conserved histidyl residues in the duplicated PRDs. However, the actual phosphorylation sites differ among these regulators. The activator LevR is phosphorylated at a histidyl residue in PRD-II by EIIBLev in the absence of the inducer fructose, causing inactivation (27), while the antiterminators of this class of regulators are negatively controlled by phosphorylation of a residue in PRD-I (2, 5, 47). In contrast, activation of LevR takes place by HPr-dependent phosphorylation on His-585 (27). This histidine, however, does not correspond to a histidyl residue which is conserved in all PRDs. Additionally, the proteins SacY and LicT were phosphorylated by HPr on several histidyl residues (25, 47).

In this study we investigated the involvement of the conserved histidyl residues in the PRDs and in the EIIA domain of the LicR protein in the regulation of LicR activity. Surprisingly, the activity of LicR seems to require phosphorylation of both PRD-I and PRD-II. The replacement of each of the four histidyl residues in the PRDs leads to the loss of induction of the lic operon. Similarly, expression of the operon is also completely abolished in a ΔptsGHI genetic background (46). Thus, LicR might be activated by phosphorylation of histidyl residues in PRD-I and PRD-II by HPr (in analogy to the other PRD-containing regulators), and all histidyl residues might be necessary for LicR activity. The presumptive phosphorylation site of the EIIA-like domain, His-559, seems to be involved in negative control of LicR activity. The expression of the lic operon is constitutive in a licRH559G mutant as well as in an EIILic mutant.

These results suggest the existence of a regulatory mechanism for LicR different from the one proposed for other PRD-containing regulators (42). Both PRDs are required for positive control of LicR, and a third regulatory domain (the EIIA domain) is involved in negative regulation of the regulator. This notion is in agreement with the conclusion that possibly more than one mechanism for negative control of PRD-containing regulators is operative (2).

In conclusion, we propose that the PTS EIILic is phosphorylated in the absence of oligomeric β-glucosides. Under these conditions, LicB (or LicA) phosphorylates the EIIA domain of LicR, causing inactivation of the regulator. If oligomeric β-glucosides are transported and phosphorylated by the PTS EIILic, then the EIIA domain of LicR cannot be phosphorylated by EIILic. Under inducing conditions, the activity of LicR depends on the phosphorylation state of the PRDs. In the absence of repressing sugars, the PRDs may be phosphorylated. Thus, the LicR protein is stimulated, and the lic operon is expressed. By contrast, in the presence of rapidly metabolized PTS carbon sources, a competition of the PTS enzyme II components and the PRDs of LicR for the phosphoryl donor HPr might take place. Thus, the level of phosphorylation at the PRDs decreases, resulting in a loss of LicR activity (Fig. 4).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to A. Tschirner for excellent technical assistance. We thank S. Bachem for help with the site-directed mutagenesis of licR. G. Mittenhuber, F. Titgemeyer, and U. Zuber are acknowledged for critical reading of the manuscript and for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

The Bacillus stearothermophilus MtlR activator, which has a domain structure similar to LicR, has recently been shown to be phosphorylated by PTS proteins. HPr-dependent phosphorylation stimulates MtlR binding to DNA, whereas phosphorylation by EIICB inhibits DNA binding (S. A. Henstra et al., J. Biol. Chem. 274:4754–4763, 1999).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnaud M, Vary P, Zagorec M, Klier A, Débarbouillé M, Postma P, Rapoport G. Regulation of the sacPA operon of Bacillus subtilis: identification of phosphotransferase system components involved in SacT activity. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3161–3170. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3161-3170.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachem S, Stülke J. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis GlcT antiterminator protein by components of the phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5319–5326. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5319-5326.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charrier V, Buckley E, Parsonage D, Galinier A, Darbon E, Jaquinod M, Forest E, Deutscher J, Claiborne A. Cloning and sequencing of two enterococcal glpK genes and regulation of the encoded glycerol kinases by phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent, phosphotransferase system-catalyzed phosphorylation of a single histidyl residue. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14166–14174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crutz A M, Steinmetz M, Aymerich S, Richter R, Le Coq D. Induction of levansucrase in Bacillus subtilis: an antitermination mechanism negatively controlled by the phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1043–1050. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.1043-1050.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Débarbouillé M, Arnaud M, Fouet A, Klier A, Rapoport G. The sacT gene regulating the sacPA operon in Bacillus subtilis shares strong homology with transcriptional antiterminators. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3966–3973. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3966-3973.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deutscher J, Küster E, Bergstedt U, Charrier V, Hillen W. Protein kinase-dependent HPr/CcpA interaction links glycolytic activity to carbon catabolite repression in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:1049–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deutscher J, Pevec B, Beyreuther K, Kiltz H-H, Hengstenberg W. Streptococcal phosphoenolpyruvate-sugar phosphotransferase system: amino acid sequence and site of ATP-dependent phosphorylation of HPr. Biochemistry. 1986;25:6543–6551. doi: 10.1021/bi00369a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutscher J, Reizer J, Fischer C, Galinier A, Saier M H, Steinmetz M. Loss of protein kinase-catalyzed phosphorylation of HPr, a phosphocarrier protein of the phosphotransferase system, by mutation of ptsH gene confers catabolite repression resistance to several catabolic genes of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3336–3344. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3336-3344.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutscher J, Saier M H. ATP-dependent, protein kinase-catalyzed phosphorylation of a seryl residue in HPr, a phosphoryl carrier protein of the phosphotransferase system in Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6790–6794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faires N, Tobisch S, Bachem S, Martin-Verstraete I, Hecker M, Stülke J. The catabolite control protein CcpA controls ammonium assimilation in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;1:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galinier A, Kravanja M, Engelmann R, Hengstenberg W, Kilhoffer M C, Deutscher J, Haiech J. New protein kinase and protein phosphatase families mediate signal transduction in bacterial catabolite repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1823–1828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunnewijk M G W, Postma P W, Poolman B. Phosphorylation and functional properties of the IIA domain of the lactose transport protein of Streptococcus thermophilus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:632–641. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.632-641.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henkin T M, Grundy F J, Nicholson W L, Chambliss G H. Catabolite repression of alpha-amylase gene expression in Bacillus subtilis involves a trans-acting gene product homologous to the Escherichia coli lacI and galR repressors. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:575–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hueck C J, Hillen W. Catabolite repression in Bacillus subtilis: a global regulatory mechanism for Gram-positive bacteria? Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:395–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hueck C J, Hillen W, Saier M H. Analysis of a cis-active sequence mediating catabolite repression in Gram-positive bacteria. Res Microbiol. 1994;145:503–518. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraus A, Hueck C, Gärtner D, Hillen W. Catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis xyl operon involves a cis element functional in the context of an unrelated sequence, and glucose exerts additional xylR-dependent repression. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1738–1745. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1738-1745.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krüger S, Gertz S, Hecker M. Transcriptional analysis of the bglPH expression in Bacillus subtilis: evidence for two distinct pathways mediating carbon catabolite repression. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2637–2644. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2637-2644.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krüger S, Hecker M. Regulation of the putative bglPH operon for aryl-β-glucoside utilization in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5590–5597. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5590-5597.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krüger S, Stülke J, Hecker M. Catabolite repression of β-glucanase synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2047–2054. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-9-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero M G, Bessieres P, Bolotin A, Borchert S, Borriss R, Boursier L, Brans A, Braun M, Brignell S C, Bron S, Brouillet S, Bruschi C V, Caldwell B, Capuano V, Carter N M, Choi S K, Codani J J, Connerton I F, Danchin A, et al. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunst F, Rapoport G. Salt stress is an environmental signal affecting degradative enzyme synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2403–2407. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2403-2407.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landt O, Grunert H-P, Hahn U. A general method for rapid site-directed mutagenesis using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1990;96:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90351-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Coq D, Lindner C, Krüger S, Steinmetz M, Stülke J. New β-glucoside (bgl) genes in Bacillus subtilis: the bglP gene product has both transport and regulatory functions, similar to those of BglF, its Escherichia coli homolog. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1527–1535. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1527-1535.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lereclus D, Arantes O. spbA locus ensures the segregational stability of pTH1030, a novel type of Gram-positive replicon. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindner C, Galinier A, Hecker M, Deutscher J. Regulation of the activity of the Bacillus subtilis antiterminator LicT by PEP-dependent, enzyme I- and HPr-catalyzed phosphorylation. Mol Microbiol. 1999;3:995–1006. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maede H M, Long S R, Ruvkun G B, Brown S E, Ausubel F M. Physical and genetic characterization of symbiotic and auxotrophic mutants of Rhizobium meliloti induced by transposon Tn5 mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:114–122. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.114-122.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin-Verstraete I, Charrier V, Stülke J, Galinier A, Erni B, Rapoport G, Deutscher J. Antagonistic effects of dual PTS-catalyzed phosphorylation on the Bacillus subtilis transcriptional activator LevR. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:293–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin-Verstraete I, Débarbouillé M, Klier A, Rapoport G. Levanase operon of Bacillus subtilis includes a fructose-specific phosphotransferase system regulating the expression of the operon. J Mol Biol. 1990;214:657–671. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90284-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin-Verstraete I, Débarbouillé M, Klier A, Rapoport G. Mutagenesis of the Bacillus subtilis ′−12, −24′ promoter of the levanase operon and evidence for the existence of an upstream activating sequence. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:85–99. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin-Verstraete I, Stülke J, Klier A, Rapoport G. Two different mechanisms mediate catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis levanase operon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6919–6927. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6919-6927.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller J. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moszer I, Glaser P, Danchin A. SubtiList: a relational database for the Bacillus subtilis genome. Microbiology. 1995;141:261–268. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-2-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Postma P W, Lengeler J W, Jacobson G R. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:543–594. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.543-594.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reiche B, Frank R, Deutscher J, Meyer N, Hengstenberg W. Staphylococcal phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system: purification and characterization of the mannitol-specific enzyme IIImtl of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus carnosus and homology with the enzyme IIImtl of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6512–6516. doi: 10.1021/bi00417a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reizer J, Hoischen C, Titgemeyer F, Rivolta C, Rabus R, Stülke J, Karamata D, Saier M H, Hillen W. A novel protein kinase that controls carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1157–1169. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saier M H. Protein phosphorylation and allosteric control of inducer exclusion and catabolite repression by the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:109–120. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.109-120.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saier M H, Reizer J. Proposed uniform nomenclature for the proteins and the protein domains of the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1433–1438. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1433-1438.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnetz K, Stülke J, Gertz S, Krüger S, Krieg M, Hecker M, Rak B. LicT, a Bacillus subtilis transcriptional antiterminator protein of the BglG family. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1971–1979. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1971-1979.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinmetz M. Carbohydrate catabolism: pathways, enzymes, genetic regulation, and evolution. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stülke J, Arnaud M, Rapoport G, Martin-Verstraete I. PRD—a protein domain involved in PTS-dependent induction and carbon catabolite repression of catabolic operons in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:865–874. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stülke J, Hanschke R, Hecker M. Temporal activation of β-glucanase synthesis in Bacillus subtilis is mediated by the GTP pool. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2041–2045. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-9-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stülke J, Martin-Verstraete I, Charrier V, Klier A, Deutscher J, Rapoport G. The HPr protein of the phosphotransferase system links induction and catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis levanase operon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6928–6936. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6928-6936.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stülke J, Martin-Verstraete I, Zagorec M, Rose M, Klier A, Rapoport G. Induction of the Bacillus subtilis ptsGHI operon by glucose is controlled by a novel antiterminator, GlcT. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:65–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4351797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45a.Tobisch, S. Unpublished results.

- 46.Tobisch S, Glaser P, Krüger S, Hecker M. Identification and characterization of a new β-glucoside utilization system in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:496–506. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.496-506.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tortosa P, Aymerich S, Lindner C, Saier M H, Reizer J, Le Coq D. Multiple phosphorylation of SacY, a Bacillus subtilis antiterminator negatively controlled by the phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17230–17237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]